Lanthanum-Silica Sol-Gel Coatings for Protecting Metallic Materials in Museums: Approaches to Copper, Bronze, Lead and Steel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Design of environmentally friendly sol-gel coatings doped with corrosion inhibitors: lanthanum salts.

- Production of these doped sol-gel coatings as a chemically active layer upon copper, bronze, lead and steel substrates.

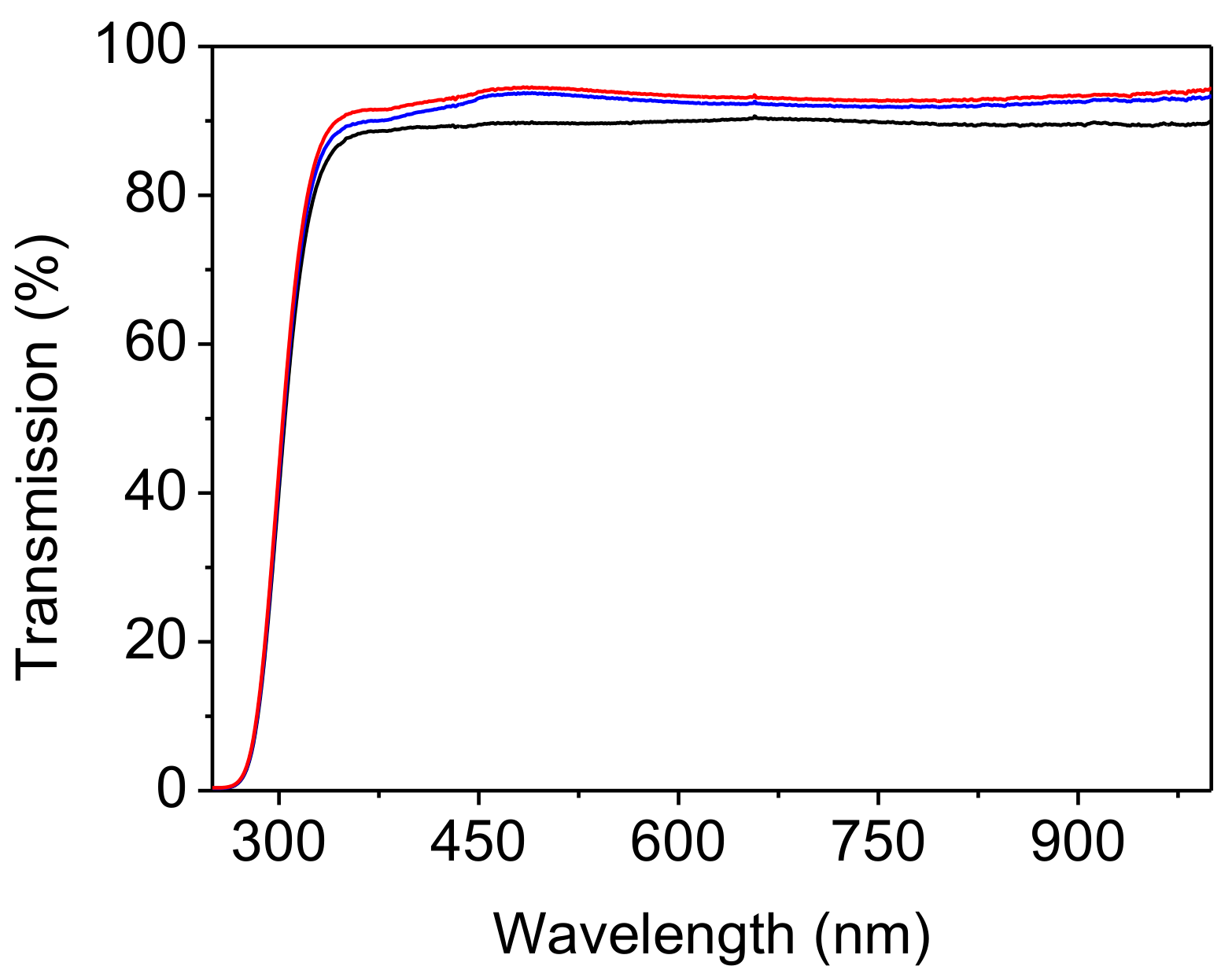

- Study of the coatings’ behaviour under laboratory conditions: thermal, structural, chemical and optical.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Behaviour

3.2. Structural Features

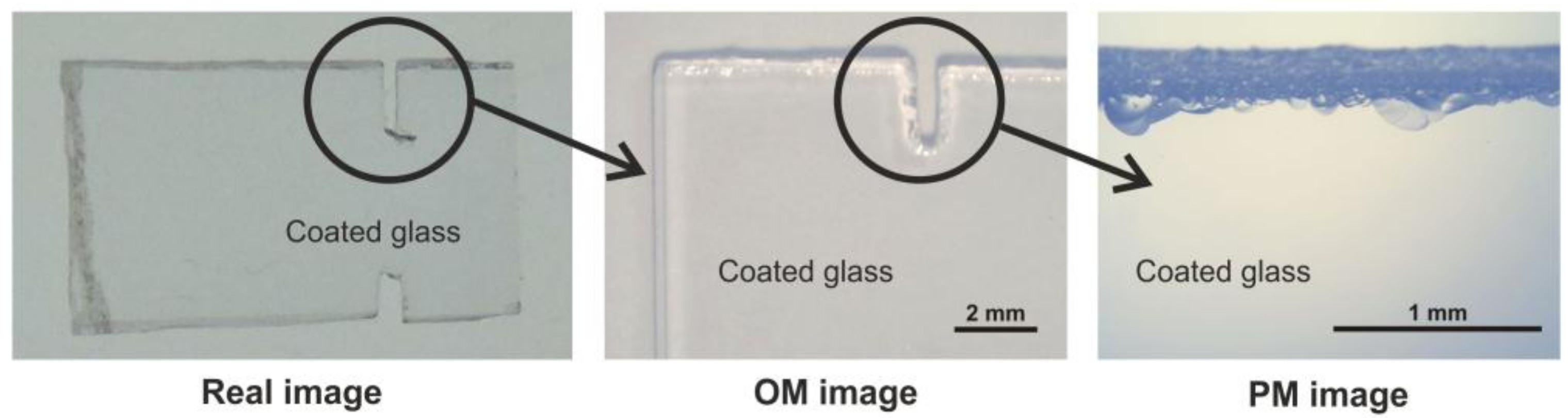

3.3. Macroscopic Quality

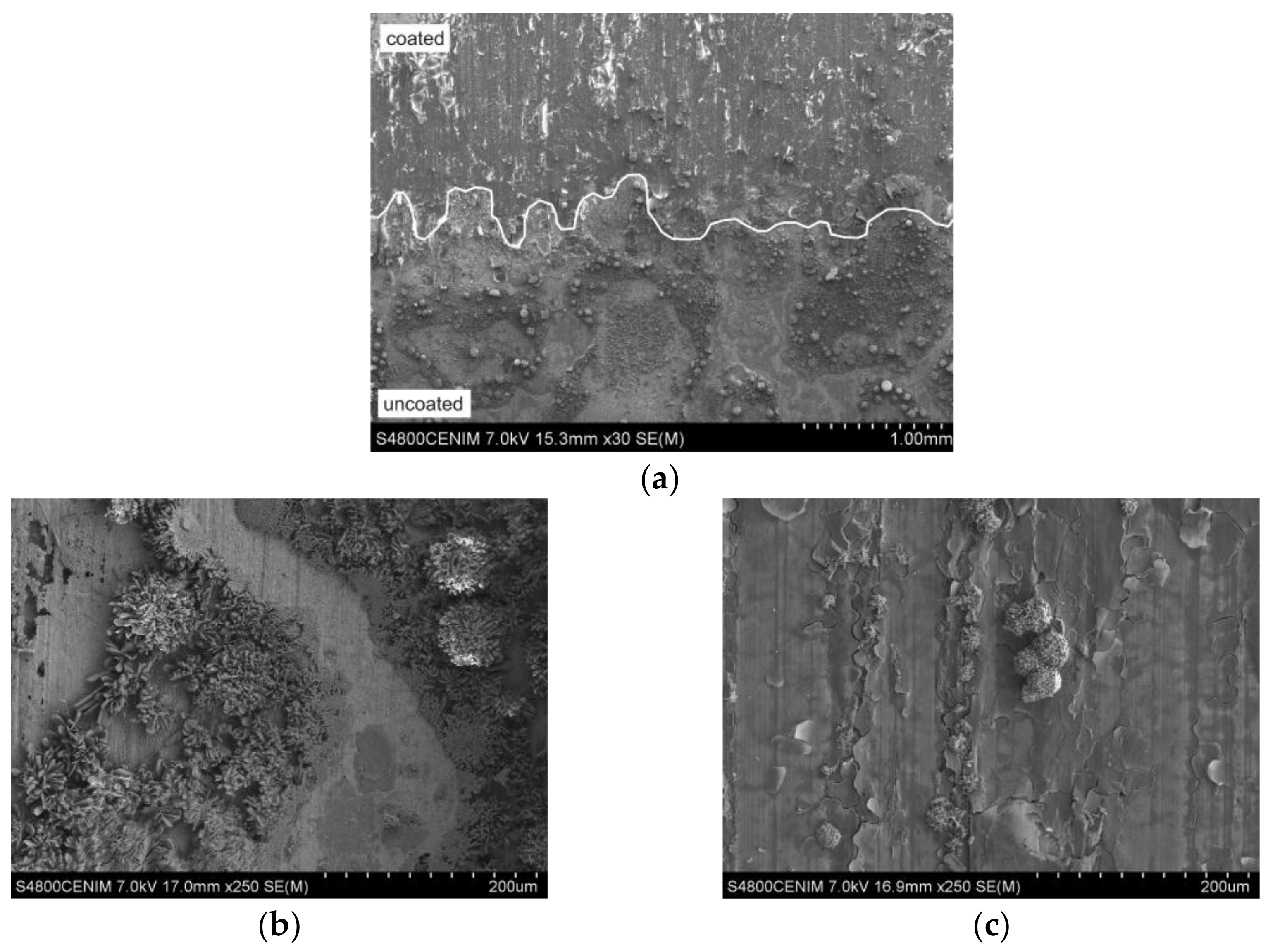

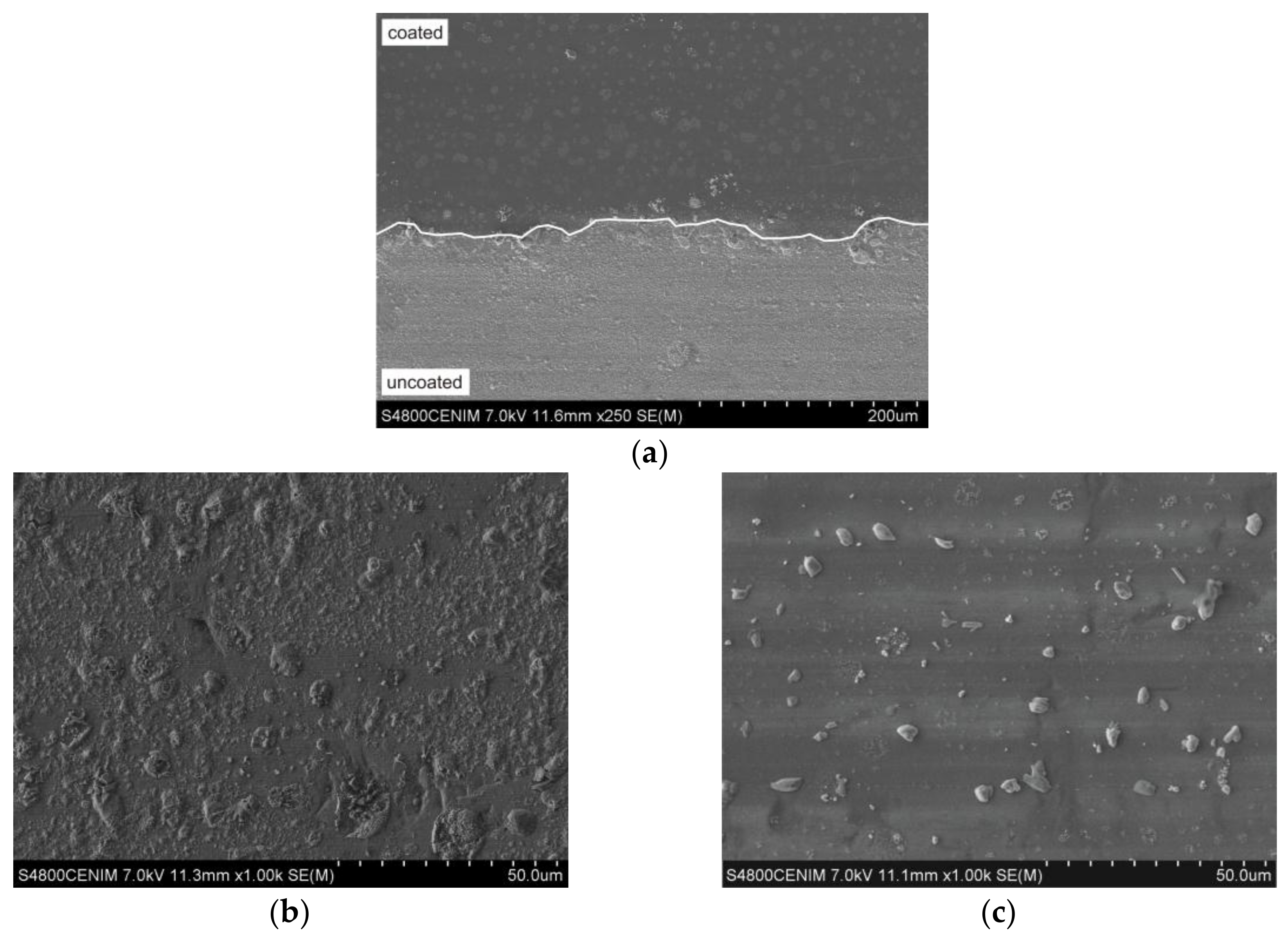

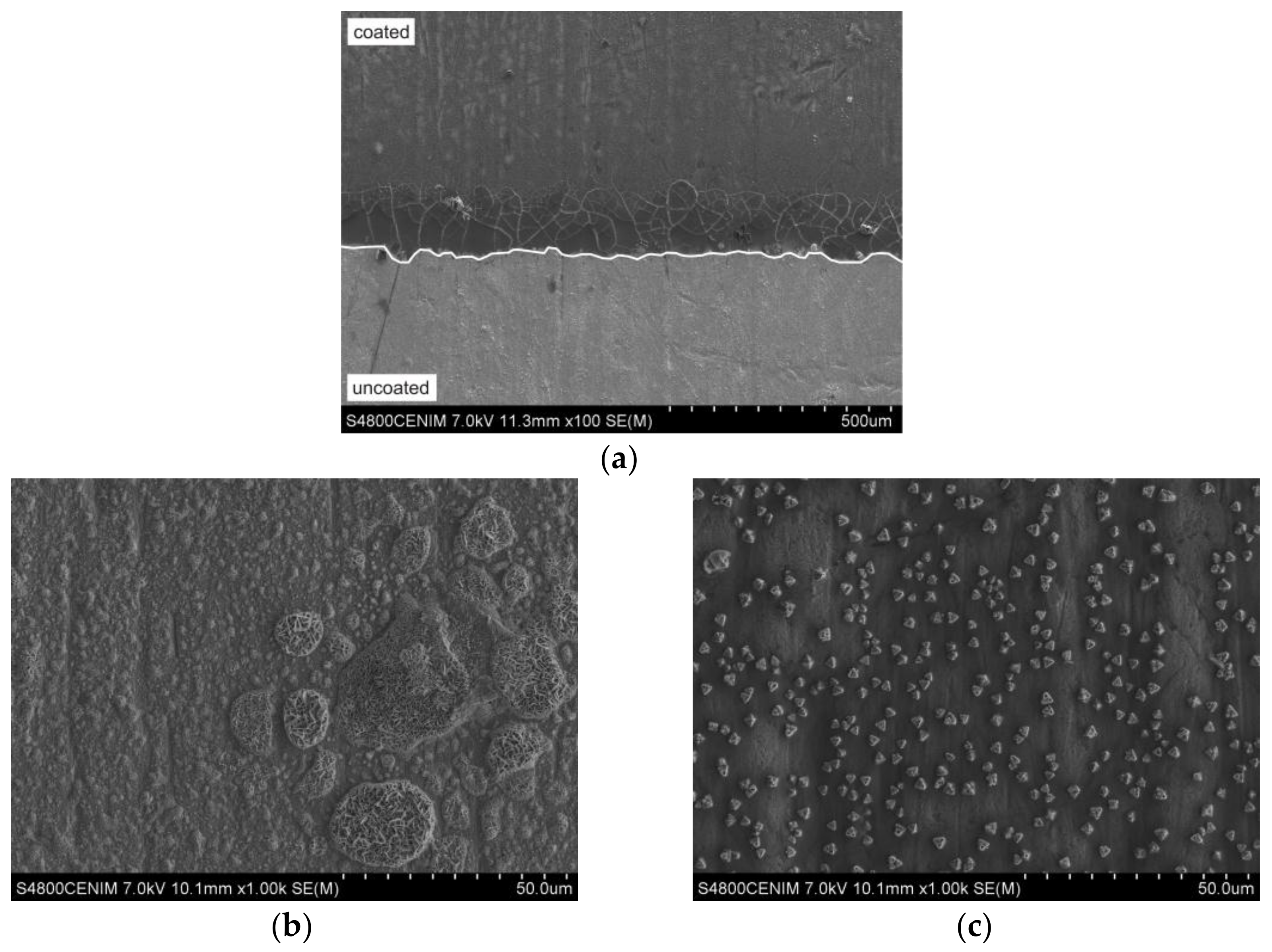

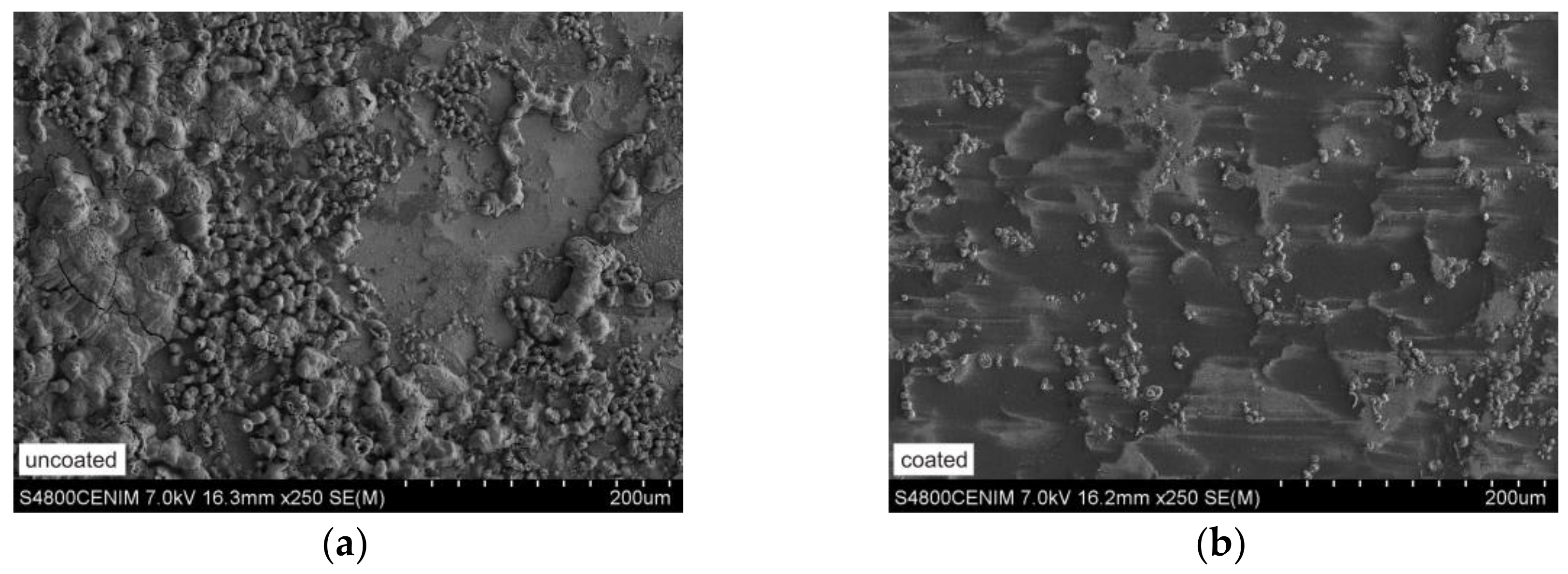

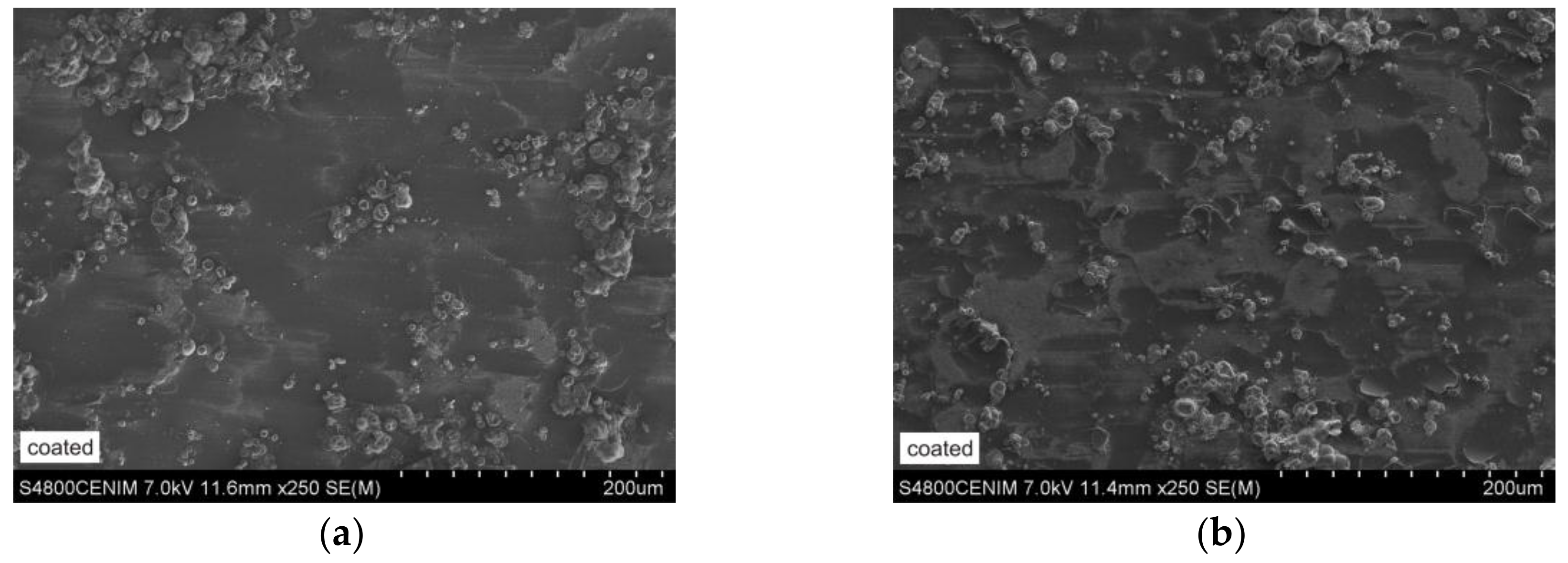

3.4. Microstructural Features

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chico, B.; de la Fuente, D.; Morcillo, M. Corrosión atmosférica de metales en condiciones climáticas extremas. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2000, 39, 329–332. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.; Allen, G.C. Nature of lead patination. Brit. Corros. J. 1999, 34, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julve, E. Un fenómeno corrosivo deseable: La atractiva pátina verde de los edificios nórdicos y centroeuropeos. An. Quím. 2006, 102, 68–72. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bethencourt, M.; Botana, F.J.; Calvino, J.J.; Marcos, M.; Rodríguez-Chacón, M.A. Lanthanide compounds as environmentally friendly corrosion inhibitors of aluminum alloys. A review. Corros. Sci. 1998, 40, 1803–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Thiery, R.; Welter, J.M.; Duterne, M. Hybrid sol-gel clear coatings for decoration brass profiles. Rev. Met. Paris 2001, 98, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárraga, R.; Cervantes, J.; Salazar-Hernández, C.; Wheeler, G. Effect of the addition of hydroxyl-terminated polydimethylsiloxane to TEOS-based stone consolidants. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberana-Fernández, A.M.; Carmona-Quiroga, P.M.; Blanco-Varela, M.T. Interaction of TEOS with cementitious materials: Chemical and physical effects. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, M.J.; de los Santos, D.M.; Rivas, T. Surfactant-synthesized ormosils with application to stone restoration. Langmuir 2010, 26, 6737–6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoni, E.; Graziani, G.; Sassoni, E. TEOS-based treatments for stone consolidation: Acceleration of hydrolysis-condensation reactions by poulticing. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 2015, 74, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, M.J.; de los Santos, D.M.; Rivas, T.; Sanmartín, P.; Silva, B. New nanomaterials for protecting and consolidating stone. J. Nano Res. 2009, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bardi, M.; Hutter, H.; Schreiner, M.; Bertoncello, R. Sol–gel silica coating for potash–lime–silica stained glass: Applicability and protective effect. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2014, 390, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bianco, B.; Bertoncello, R. Sol–gel silica coatings for the protection of cultural heritage glass. Nucl. Instrum. Met. Phys. Res. B 2008, 266, 2358–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constâncio, C.; Franco, L.; Russo, S.; Ajinho, C.; Pires, J.; Vaz, M.F.; Carvalho, A.P. Studies on polymeric conservation treatments of ceramic tiles with Paraloid B-72 and two alkoxysilanes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 116, 2833–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchi, F. Sol-gel coatings for the preservation of metallic heritage artefacts. In Corrosion and Conservation of Cultural Heritage Metallic Artefacts, 1st ed.; Dillmann, P., Watkinson, D., Angelini, E., Adriaens, A., Eds.; European Federation of Corrosion (EFC) Series; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 540–551. ISBN 9781782421542. [Google Scholar]

- Figueira, R.B.; Fontinha, I.R.; Silva, C.J.R.; Pereira, E.V. Hybrid sol-gel coatings: Smart and green materials for corrosion mitigation. Coatings 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, R.B.; Silva, C.J.R.; Pereira, E.V. Organic–inorganic hybrid sol–gel coatings for metal corrosion protection: A review of recent progress. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2014, 12, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Bierwagen, G.P. Sol–gel coatings on metals for corrosion protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 2009, 64, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, M.A.; Bethencourt, M.; Botana, F.J.; de Damborenea, J.; Marcos, M. Inhibition of 5083 aluminum alloy and galvanised steel by lanthanide salts. Corros. Sci. 2001, 43, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Heras, M.; Jiménez-Morales, A.; Casal, B.; Galván, J.C.; Radzki, S.; Villegas, M.A. Preparation and electrochemical study of cerium-silica sol-gel thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 380, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemor, M.F.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Corrosion performance of a two-step pre-treatment for galvanized steel based on lanthanum nitrate and silanes. Surf. Interface Anal. 2004, 36, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxiao, W.; Gang, K.; Ziwen, S.; Chunshan, C. Preparation and corrosion performance of lanthanum nitrate conversion coating on hot-dip Galfan steel. Chin. J. Mater. Res. 2016, 30, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasakau, K.A.; Zheludkevich, M.L.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Lanthanide salts as corrosion inhibitors for AA5083. Mechanism and efficiency of corrosion inhibition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, C169–C177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethencourt, M.; Botana, F.J.; Cauqui, M.A.; Marcos, M.; Rodríguez, M.A.; Rodríguez-Izquierdo, J.M. Protection against corrosion in marine environments of AA5083 Al-Mg alloy by lanthanide chlorides. J. Alloys Compd. 1997, 250, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuín, M.; Serrano, A.; Llopis, J.; García, M.A.; Carmona, N. Silica doped with lanthanum sol–gel thin films for corrosion protection. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 5267–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Li, S.; Shi, Z.; LV, X.; Zhao, Z. Studies of the conversion coatings formed by combined use of lanthanum salt and benzotriazole on commercial brass. Anti Corros. Method. Mater. 2012, 59, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, K.; Lingyan, L.; Jintang, L.; Chunshan, C.; Zheng, Z. Study on lanthanum salt conversion coating modified with citric acid on hot dip galvanized steel. J. Rare Earth 2010, 28, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.C.; Chandrashekhar, G.V.; George, M.V.; Rao, C.N.R. Infrared spectra and thermal decompositions of metal acetates and dicarboxylates. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.A.; Hayward, R.N. Transition metal acetates. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 3443–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.A.; Paje, S.; Llopis, J.; Villegas, M.A. Influencia de las condiciones de preparación en la luminiscencia de recubrimientos de sílice pura. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2000, 39, 641–646. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO-9142 Guía Para la Selección de Condiciones de Envejecimiento Normalizadas de Laboratorio Para Someter a Ensayo Juntas Pegadas; AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2004. (In Spanish)

- DIN-50018 Sulfur Dioxide Corrosion Testing in a Saturated Atmosphere; DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 1997.

- Tétreault, J.; Cano, E.; van Bommel, M.; Scott, D.; Dennis, M.; Barthés-Labrousse, M.G.; Minel, L.; Robbiola, L. Corrosion of copper and lead by formaldehyde, formic acid and acetic acid vapours. Stud. Conserv. 2003, 48, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, D.M.; Smets, B.M.J. Group III ions in sodium silicate glass, 2, Raman study. Phys. Chem. Glasses 1984, 25, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Smets, B.M.J.; Krol, D.M. Group III ions in sodium silicate glass, 1, X-ray photoelectron study. Phys. Chem. Glasses 1984, 25, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, A.J.G.; Hess, P.C. Vibrational spectra of high-silica glasses of the system K2O-SiO2-La2O3. J. Non Cryst. Solids 1991, 127, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo da Rocha, S.M.; da Silva Queiroz, C.A.; Abrao, A. Synthesis and characterization of lanthanum acetate for application as a catalyst. J. Alloys Compd. 2002, 344, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünzli, J.C.G.; Moret, E.; Yersin, J.R. Vibrational spectra of anhydrous lanthanum, europium, gadolinium, and dysprosium nitrates and oxinitrates. Helv. Chim. Acta 1978, 61, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, B.; Vannice, M.A. Influence of pretreatment on lanthanum nitrate, carbonate, and oxide powders. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 2755–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrates | Chemical Composition (wt %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Copper | Cu | Others |

| 99.95 | rest | |

| Substrates | Chemical Composition (wt %) (min–max) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronze | Cu | Sn | Pb | Zn | Ni | Others |

| rest | 6–8 | 5–8 | 3.5–5.5 | 0–2 | 0–1 | |

| Substrates | Chemical Composition (wt %) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | Cu | Sn | Zn | Fe | Sb | Bi | As | Ag | Cd | Pb |

| 0.0319 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.0233 | 0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.0009 | rest | |

| Substrates | Chemical Composition (wt %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | Fe | C | Mn | P | S | Si | Al |

| rest | 0.052 | 0.246 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.051 | |

| Treatment | Test Equipment | Conditions | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated ageing | Climatic chamber | Standard ISO-9142 23 °C 85% RH 1 day 55 °C 28% RH 1 day 23 °C 85% RH 3 days 55 °C 28% RH 2 days | 21 days |

| Accelerated ageing under SO2 atmosphere | Kesternich corrosion chamber | Standard DIN 50018 40 °C 100% RH 0.5 L SO2 8 h closed door 16 h open door | 1 cycle |

| Organic acids | Desiccator | Acetic acid + formic acid (0.01 vol. %) saturated atmosphere | 7 days |

| UV irradiation | UV lamp | 300 W | 21 days |

| Gel Sample | DTA | TGA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | Effect | T (°C) | Effect | |

| 100 SiO2 Blank | 73 | ENDO Loss adsorbed water and alcohols | Room-100 | Great loss of water and alcohols |

| 130–220 | EXO Organic precursors oxidation | 100–300 | Great loss due to organic matter release | |

| 356 | EXO Organic groups decomposition | 300–400 | ||

| 522 | ENDO Si-OH groups release | 500–600 | Small loss of chemically bonded water | |

| 1La2O3·99SiO2 La(Ac)3 | 97 | ENDO Loss adsorbed water and alcohols | Room-135 | Great loss of water and alcohols |

| 130–275 | EXO Organic precursors oxidation | 130–400 | Great loss due to organic matter release | |

| 350 | EXO Organic groups decomposition | |||

| 500– | ENDO Si-OH groups release | 500– | Progressive loss of chemically bonded water | |

| 1La2O3·99SiO2 La(NO3)3 | 87 | ENDO Loss adsorbed water and alcohols | Room-140 | Great loss of water and alcohols |

| 140–295 | EXO Organic precursors oxidation | 140–400 | Great loss due to organic matter release | |

| 300–400 | EXO Organic groups decomposition | |||

| 545 | ENDO Si-OH groups release | 500– | Progressive loss of chemically bonded water | |

| Dopant in the Coating | Weight Loss at 60 °C (%) | Temperature at Which 5% Weight Loss Occurs (°C) | Final Weight Loss at 700 °C (%) | Temperature at Which Maximum Weight Loss Rate Occurs (°C) | Weight Loss at the Maximum Weight Loss Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (blank) | 3.36 | 71.67 | 21.59 | 65.17 | 4.03 |

| La(Ac)3 | 3.55 | 70.26 | 23.88 | 94.91 | 9.03 |

| La(NO3)3 | 4.06 | 67.10 | 25.05 | 89.94 | 8.47 |

| Gel Sample | Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assignment | Intensity 1 | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 SiO2 Blank | 465 | δ Si–O–Si | XXXX | Siloxane matrix |

| 577; 801 | νs Si–O–Si | XXX; XXX | Siloxane matrix | |

| 951 | ν Si–OH | XXX | Raw alkoxides | |

| 1085 | ν Si–O; vas Si–O | XXXXX | Si–OCH3; Si–O–Si | |

| 1166 | νs C–O | XXXXX, x | Raw alkoxides | |

| 1286 | νas C–O | XX, x | Raw alkoxides | |

| 1398; 1450 | δ CH2 | X; X | Si–R | |

| 1637 | ν C=C | XXX | Raw alkoxides | |

| 2921; 2988 | ν C–H; ν C–H | X; X | Si–R; –OCH2CH3 | |

| 3430 | ν O–H | XXXXX | Si–OH | |

| 1La2O3·99SiO2 La(Ac)3 | 463 | δ Si–O–Si ; π COO– | XXX | Siloxane matrix; La(Ac)3 |

| 564 | ν La–O | XXX | La(Ac)3 | |

| 800 | νs Si–O–Si | XXX | Siloxane matrix | |

| 948 | ν Si–OH; ν C–C | XXX | Raw alkoxides; La(Ac)3 | |

| 1083 | ν Si–O; vas Si–O; ν CH3 | XXXXX | Si–OCH3; Si–O–Si; La(Ac)3 | |

| 1154 | νs C–O | XXXXX, x | Raw alkoxides | |

| 1384 | δs CH3 | XXX | La(Ac)3 | |

| 1460 | δas CH3 | X | La(Ac)3 | |

| 1632 | ν C=C | XXX | Raw alkoxides | |

| 2854; 2925 | νs C–H; ν C–H | X | La(Ac)3; Si–R | |

| 3433 | ν O–H | XXXXX | Si–OH | |

| 1La2O3·99SiO2 La(NO3)3 | 457 | δ Si–O–Si | XXXX | Siloxane matrix |

| 565 | ν La–O | XXX | LaO(NO3) | |

| 798 | ν NO3− | XXX | La(NO3)3 | |

| 944 | ν Si–OH | XXX | Raw alkoxides | |

| 1084 | ν Si–O; vas Si–O | XXXXX | Si–OCH3; Si–O–Si | |

| 1160 | νs C–O | XXXXX, x | Raw alkoxides | |

| 1387; 1463 | δ CH2 | X; X | Si–R | |

| 1632 | ν C=C | XXX | Raw alkoxides | |

| 2850; 2925 | νs C–H | X | Si–R | |

| 3429 | ν O–H | XXXXX | Si–OH |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Poza, J.; Agua, F.; Gil, C.; Villegas, M.-Á.; García-Heras, M. Lanthanum-Silica Sol-Gel Coatings for Protecting Metallic Materials in Museums: Approaches to Copper, Bronze, Lead and Steel. Coatings 2018, 8, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8040138

Peña-Poza J, Agua F, Gil C, Villegas M-Á, García-Heras M. Lanthanum-Silica Sol-Gel Coatings for Protecting Metallic Materials in Museums: Approaches to Copper, Bronze, Lead and Steel. Coatings. 2018; 8(4):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8040138

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Poza, Javier, Fernando Agua, Cristina Gil, María-Ángeles Villegas, and Manuel García-Heras. 2018. "Lanthanum-Silica Sol-Gel Coatings for Protecting Metallic Materials in Museums: Approaches to Copper, Bronze, Lead and Steel" Coatings 8, no. 4: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8040138