Immunophenotypic but Not Genetic Changes Reclassify the Majority of Relapsed/Refractory Pediatric Cases of Early T-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

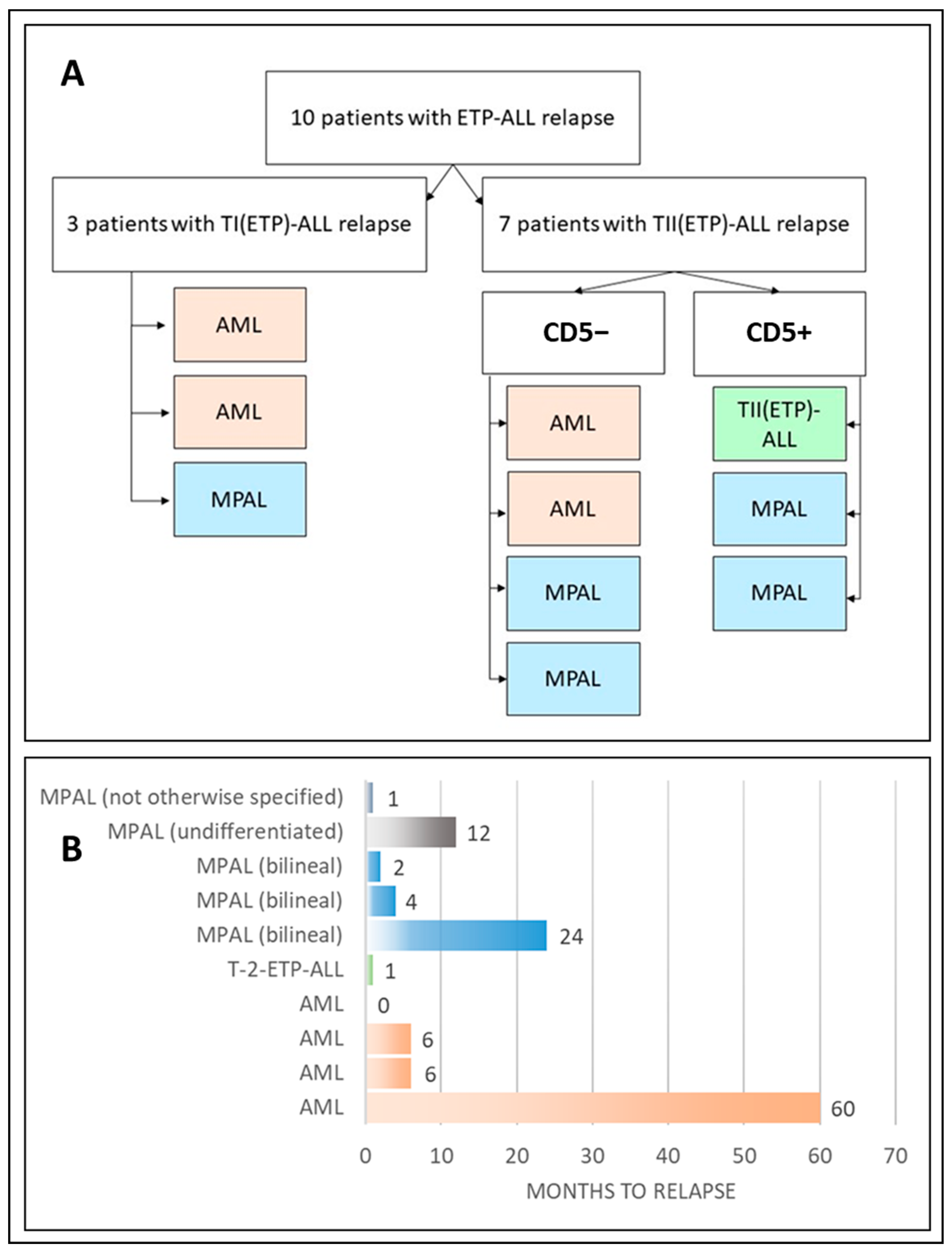

2. Results

2.1. Group Description

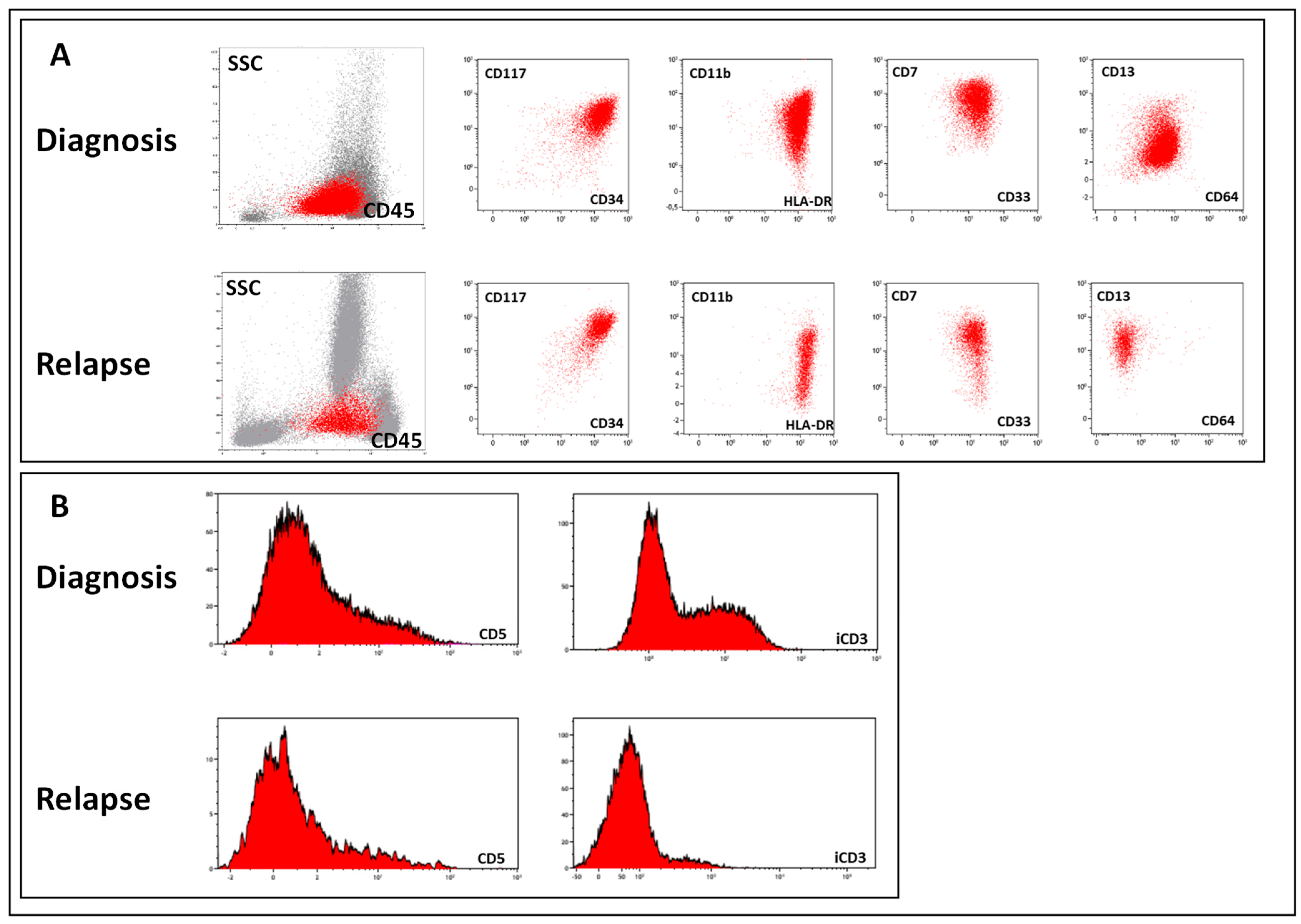

2.2. Immunophenotyping

2.3. Genetic Studies

3. Discussion

4. Patients and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Conventional Karyotyping and FISH

4.3. RNA-seq and RT−PCR

4.4. Assessment of the TCR Clonal Repertoire by NGS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coustan-Smith, E.; Mullighan, C.G.; Onciu, M.; Behm, F.G.; Raimondi, S.C.; Pei, D.; Cheng, C.; Su, X.; Rubnitz, J.E.; Basso, G.; et al. Early T-cell precursor leukaemia: A subtype of very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, L.; Holmfeldt, L.; Wu, G.; Heatley, S.L.; Payne-Turner, D.; Easton, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Rusch, M.; et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 2012, 481, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genesca, E.; la Starza, R. Early T-Cell Precursor ALL and Beyond: Immature and Ambiguous Lineage T-ALL Subsets. Cancers 2022, 14, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, C.F.; Man, P.M. Early T-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Diagnosis, Updates in Molecular Pathogenesis, Management, and Novel Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 750789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conter, V.; Valsecchi, M.G.; Buldini, B.; Parasole, R.; Locatelli, F.; Colombini, A.; Rizzari, C.; Putti, M.C.; Barisone, E.; Lo Nigro, L.; et al. Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children treated in AIEOP centres with AIEOP-BFM protocols: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e80–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inukai, T.; Kiyokawa, N.; Campana, D.; Coustan-Smith, E.; Kikuchi, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Takahashi, H.; Koh, K.; Manabe, A.; Kumagai, M.; et al. Clinical significance of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Results of the Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group Study L99-15. Br. J. Haematol. 2012, 156, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, K.; Wade, R.; Goulden, N.; Mitchell, C.; Moorman, A.V.; Rowntree, C.; Jenkinson, S.; Hough, R.; Vora, A. Outcome for children and young people with Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated on a contemporary protocol, UKALL 2003. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 166, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrappe, M.; Valsecchi, M.G.; Bartram, C.R.; Schrauder, A.; Panzer-Grumayer, R.; Moricke, A.; Parasole, R.; Zimmermann, M.; Dworzak, M.; Buldini, B.; et al. Late MRD response determines relapse risk overall and in subsets of childhood T-cell ALL: Results of the AIEOP-BFM-ALL 2000 study. Blood 2011, 118, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworzak, M.N.; Buldini, B.; Gaipa, G.; Ratei, R.; Hrusak, O.; Luria, D.; Rosenthal, E.; Bourquin, J.P.; Sartor, M.; Schumich, A.; et al. AIEOP-BFM consensus guidelines 2016 for flow cytometric immunophenotyping of Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cytom. B Clin. Cytom. 2018, 94, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permikin, Z.; Popov, A.; Verzhbitskaya, T.; Riger, T.; Plekhanova, O.; Makarova, O.; Fronkova, E.; Trka, J.; Meyer, C.; Marschalek, R.; et al. Lineage switch to acute myeloid leukemia during induction chemotherapy for early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the translocation t(6;11)(q27;q23)/KMT2A-AFDN: A case report. Leuk. Res. 2022, 112, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, J.G.; Bernasconi, A.R.; Alonso, C.N.; Rubio, P.L.; Gallego, M.S.; Carrara, C.A.; Guitter, M.R.; Eberle, S.E.; Cocce, M.; Zubizarreta, P.A.; et al. Lineage switch in childhood acute leukemia: An unusual event with poor outcome. Am. J. Hematol. 2012, 87, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, A.M.; Verzhbitskaya, T.Y.; Movchan, L.V.; Demina, I.A.; Mikhailova, E.V.; Semchenkova, A.A.; Permikin, Z.V.; Shman, T.V.; Karachunskiy, A.I.; Novichkova, G.A. Flow cytometry in acute leukemia diagnostics. Guidelines of Russian-Belarusian multicenter group for pediatric leukemia studies. Pediatr. Hematol./Oncol. Immunopathol. 2023, 22, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.J.; Bhandoola, A. The earliest thymic progenitors for T cells possess myeloid lineage potential. Nature 2008, 452, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, H.; Masuda, K.; Satoh, R.; Kakugawa, K.; Ikawa, T.; Katsura, Y.; Kawamoto, H. Adult T-cell progenitors retain myeloid potential. Nature 2008, 452, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenberg, E.V.; Moore, J.E.; Yui, M.A. Launching the T-cell-lineage developmental programme. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharlai, A.S.; Illarionova, O.I.; Fediukova, Y.G.; Verzhbitskaya, T.Y.; Fechina, L.G.; Boichenko, E.G.; Karachunskiy, A.I.; Popov, A.M. Immunophenotypic characteristics of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Hematol./Oncol. Immunopathol. 2019, 18, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.; Singh, M.K.; Gupta, R.; Rahman, K.; Yadav, D.D.; Sarkar, M.K.; Gupta, A.; Yadav, S.; Kashyap, R.; Nityanand, S. Clinicopathological and immunophenotypic features of early T cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: A flow cytometry score for the initial diagnosis. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marballi Basavaraju, D.; Mishra, S.; Chhabra, G.; Chougule, S. Comparison of flowcytometry-based scoring system for the diagnosis of early T precursor-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cytom. B Clin. Cytom. 2023, 104, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.; Bakhshi, S.; Pramanik, S.K.; Pandey, R.M.; Singh, S.; Gajendra, S.; Gogia, A.; Chandramohan, J.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, L.; et al. Immunophenotypic analysis of T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A CD5-based ETP-ALL perspective of non-ETP T-ALL. Eur. J. Haematol. 2014, 92, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli Shirazi, P.; Eadie, L.N.; Heatley, S.L.; Hughes, T.P.; Yeung, D.T.; White, D.L. The effect of co-occurring lesions on leukaemogenesis and drug response in T-ALL and ETP-ALL. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.; Fritz, A.J.; Gordon, J.A.; Tye, C.E.; Boyd, J.R.; Tracy, K.M.; Frietze, S.E.; Carr, F.E.; Nickerson, J.A.; Van Wijnen, A.J.; et al. RUNX1-dependent mechanisms in biological control and dysregulation in cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 8597–8609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, C.; Buhl, S.; Mueller, D.; Garcia-Cuellar, M.P.; Maethner, E.; Slany, R.K. Leukemogenic transformation by HOXA cluster genes. Blood 2010, 115, 2910–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, J.L.; Heath, J.L. MLLT10 in benign and malignant hematopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 2020, 87, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, M.C.; Castoldi, G.; Knapp, W.; Ludwig, W.D.; Matutes, E.; Orfao, A.; van’t Veer, M.B. Proposals for the immunological classification of acute leukemias. European Group for the Immunological Characterization of Leukemias (EGIL). Leukemia 1995, 9, 1783–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur, G.; Olshanskaya, Y.; Obukhova, T.; Sudarikov, A.; Lazareva, O.; Gindina, T. Cytogenetic and molecular genetic diagnostics in oncohematological disorders: A position paper of the Organization of Molecular Geneticists in Oncology and Oncohematology. Russ. J. Hematol. Transfusiology 2023, 68, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrig, S.; Ellermann, J.; Walther, T.; Burkhardt, P.; Frohlich, M.; Hutter, B.; Toprak, U.H.; Neumann, O.; Stenzinger, A.; Scholl, C.; et al. Accurate and efficient detection of gene fusions from RNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotin, D.A.; Poslavsky, S.; Mitrophanov, I.; Shugay, M.; Mamedov, I.Z.; Putintseva, E.V.; Chudakov, D.M. MiXCR: Software for comprehensive adaptive immunity profiling. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Xue, H.; Chen, J.; Pan, C.; Jiang, H.; Shen, S. Early T-cell precursor leukemia: A subtype of high risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Med. 2012, 6, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, M.A.; Place, A.E.; Stevenson, K.E.; Gutierrez, A.; Forrest, S.; Pikman, Y.; Vrooman, L.M.; Harris, M.H.; Hunt, S.K.; O’Brien, J.E.; et al. Identification of prognostic factors in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results from DFCI ALL Consortium Protocols 05-001 and 11-001. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.; Devidas, M.; Summers, R.J.; Chen, Z.; Asselin, B.L.; Rabin, K.R.; Zweidler-McKay, P.A.; Winick, N.J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Carroll, W.L.; et al. Prognostic Significance of ETP Phenotype and Minimal Residual Disease in T-ALL: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Blood 2023, 142, 2069–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; Kentsis, A.; Sanda, T.; Holmfeldt, L.; Chen, S.C.; Zhang, J.; Protopopov, A.; Chin, L.; Dahlberg, S.E.; Neuberg, D.S.; et al. The BCL11B tumor suppressor is mutated across the major molecular subtypes of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 4169–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cui, Q.; Dai, H.; Song, B.; Cui, W.; Xue, S.; Qiu, H.; Miao, M.; Jin, Z.; Li, C.; et al. Early T-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and T/Myeloid Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia Possess Overlapping Characteristics and Both Benefit From CAG-Like Regimens and Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2021, 27, e481–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanski, T.; Willemse, M.J.; Kamps, W.A.; van Wering, E.R.; Langerak, A.W.; van Dongen, J.J. Molecular discrimination between relapsed and secondary acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Proposal for an easy strategy. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2001, 36, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Sex | Age y. m | Immunophenotype at Diagnosis | Time to Relapse, y, m, d | Immunophenotype at Relapse | Change in AL Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | 16.1 | CD5, CD7, CD11c, CD11b, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, iCD3, iCD79a | 0, 1, 4 | CD5, CD7, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, iCD3 | TII(ETP)-ALL to TII(ETP)-ALL |

| 2 | m | 4.8 | CD5, CD7, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3, iCD79a | 1, 26 | CD7, CD11a, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD99, CD117, CD123, HLA-DR | TII(ETP)-ALL to undifferentiated AL |

| 3 | m | 6.1 | CD2, CD7, CD8, CD11a, CD11c, CD11b, CD33, CD45, CD56, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3, iCD79a | 0, 4, 5 | Population 1: 5% CD45dim/SSCdim: CD4, CD7, CD11a, CD11b, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD56, CD117, CD123, HLA-DR | TII(ETP)-ALL to bilineal MPAL |

| Population 2: 10% CD45high/SSCdim: CD2, CD7, CD8, CD11a, CD11b, CD45, CD56, HLA-DR, iCD3 | ||||||

| 4 | f | 0.6 | CD7, CD11b, CD11c, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD56, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3 | 0, 6, 27 | CD7, CD11a, CD11b, CD13, CD15, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD99, CD117, CD123, CD371, HLA-DR | TI(ETP)-ALL to AML |

| 5 | f | 6.2 | CD2, CD3, CD7, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD117, iCD3 | 0, 0, 25 | CD2, CD3, CD7, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD117 | TII(ETP)-ALL to AML |

| 6 | m | 8.6 | CD7, CD11a, CD11c, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD99, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3, iCD79a | 0, 6, 0 | CD7, CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, CD13, CD15, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD99, CD123, HLA-DR, CD117, CD123, CD371 | TI(ETP)-ALL to AML |

| 7 | m | 5.6 | CD2, CD7, CD11b, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD56, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3 | 5, 0, 0 | CD11b, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD99, CD117, CD123 | TII(ETP)-ALL to AML |

| 8 | m | 15.9 | CD3, CD5, CD7, CD13, CD15, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD99, CD117, iCD3 | 0, 2, 27 | Population 1: 11% CD45high/SSChigh: CD4, CD11a, CD11c, CD11b, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD56, CD64, CD117, CD133, | TII(ETP)-ALL to bilineal MPAL |

| Population 2: 13% CD45dim/SSCdim: CD7, CD38, CD45, CD117, iCD3 | ||||||

| 9 | m | 13.0 | CD7, CD22, CD34, CD45, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3 | 0, 1, 24 | CD4, CD7, CD11c, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD64, CD117, HLA-DR | TI(ETP)-ALL to unclassifiable AL |

| 10 | m | 14.8 | CD2, CD7, CD11a, CD13, CD34, CD45, CD117, HLA-DR, iCD3 | 2, 3 | Population 1: 83%, CD2, CD7, CD11a, CD13, CD15, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD99, CD117, CD371, HLA-DR, iCD3 | TII(ETP)-ALL to bilineal MPAL |

| Population 2: 5%, CD2, CD13, CD15, CD33, CD117, CD371, MPO |

| Patient | Sex | Age, y.m | Timepoint | DS | Clones | Cytogenetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | 16.1 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | TRD D2_D3 | del17p within complex karyotype |

| relapse | TII(ETP)-ALL | TRD D2_D3 | del17p within complex karyotype | |||

| 2 | m | 4.8 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | TRD V1_D3_J1 | KMT2A::MLLT3 |

| relapse | undifferentiated AL | TRD V1_D3_J1 | KMT2A::MLLT3 within complex karyotype | |||

| 3 | m | 6.1 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | polyclonal | trisomy 8 |

| relapse | MPAL | polyclonal | trisomy 8 | |||

| 4 | f | 0.6 | diagnosis | TI(ETP)-ALL | polyclonal | MNX1::ETV6 |

| relapse | AML | polyclonal | MNX1::ETV6 | |||

| 5 | f | 6.2 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | polyclonal | BCL11B |

| relapse | AML | polyclonal | BCL11B | |||

| 6 | m | 8.6 | diagnosis | TI(ETP)-ALL | polyclonal | complex |

| relapse | AML | polyclonal | complex | |||

| 7 | m | 5.6 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | TRD D2_D3 | trisomy 10 |

| relapse | AML | TRD D2_D3 | trisomy 10 | |||

| 8 | m | 15.9 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | no data | TLX3 |

| relapse | MPAL | no data | TLX3 | |||

| 9 | m | 13.0 | diagnosis | TI(ETP)-ALL | no data | complex |

| relapse | unclassifiable AL | no data | complex, del17p | |||

| 10 | m | 14.8 | diagnosis | TII(ETP)-ALL | no data | trisomy 4 |

| relapse | MPAL | no data | no data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Demina, I.; Dagestani, A.; Borkovskaia, A.; Semchenkova, A.; Soldatkina, O.; Kashpor, S.; Olshanskaya, Y.; Roumiantseva, J.; Karachunskiy, A.; Novichkova, G.; et al. Immunophenotypic but Not Genetic Changes Reclassify the Majority of Relapsed/Refractory Pediatric Cases of Early T-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115610

Demina I, Dagestani A, Borkovskaia A, Semchenkova A, Soldatkina O, Kashpor S, Olshanskaya Y, Roumiantseva J, Karachunskiy A, Novichkova G, et al. Immunophenotypic but Not Genetic Changes Reclassify the Majority of Relapsed/Refractory Pediatric Cases of Early T-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):5610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115610

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemina, Irina, Aya Dagestani, Aleksandra Borkovskaia, Alexandra Semchenkova, Olga Soldatkina, Svetlana Kashpor, Yulia Olshanskaya, Julia Roumiantseva, Alexander Karachunskiy, Galina Novichkova, and et al. 2024. "Immunophenotypic but Not Genetic Changes Reclassify the Majority of Relapsed/Refractory Pediatric Cases of Early T-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 5610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115610