1. Introduction

Luxury brands were identified to be one of the fastest-growing sectors of marketing in the last decade. According to a study conducted by Deloitte in 2019, aggregate sales of global luxury goods sale accounted for USD 281 billion in 2019, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8% observed over a period from 2016 to 2019, and a composite year of sales growth of 8.5%. It was also identified that the average size of the top 100 global luxury companies was identified to be USD 2.8 billion, and the composite net profit margin was identified to be 11.2% (

Deloitte 2020). Globally, Europe has the largest share (31%) of the personal luxury goods market; and the United States is recorded to be the country with the largest personal luxury goods market (

Statista 2021). The Goldstein Market Intelligence report forecasted that the luxury goods market in the Middle East is projected to reach USD 22.4 billion by 2030, with a CAGR of 8.1% during the period from 2017 to 2030 (

Goldstein Research 2021). Similarly, Deloitte has identified that the Middle East represented a big opportunity for marketing their products by global luxury brands (

Deloitte 2021). Luxury malls and many shopping areas in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, the regions which are less affected by global economic uncertainty and political unrest, and with increasing international tourism and strong growth, were identified to be major markets for global luxury brands. In addition, Saudi Arabia is another country in the region, which is transforming itself from an oil-dependent country to a knowledge-based country through its Vision 2030 programme, leading various innovations and developments in different sectors (

Nurunnabi 2017). The country has mega shopping malls in cities, such as Riyadh, Mecca, and Medina, which attract religious international tourism, and provides opportunities for global luxury brands to expand their market (

Deloitte 2021). The development of the Wassem fashion district in Jeddah is one of the examples of such initiatives led by the government for promoting entrepreneurship, manufacturing, and retail marketing in the fashion industry (

Alghamdi and Mostapha 2020).

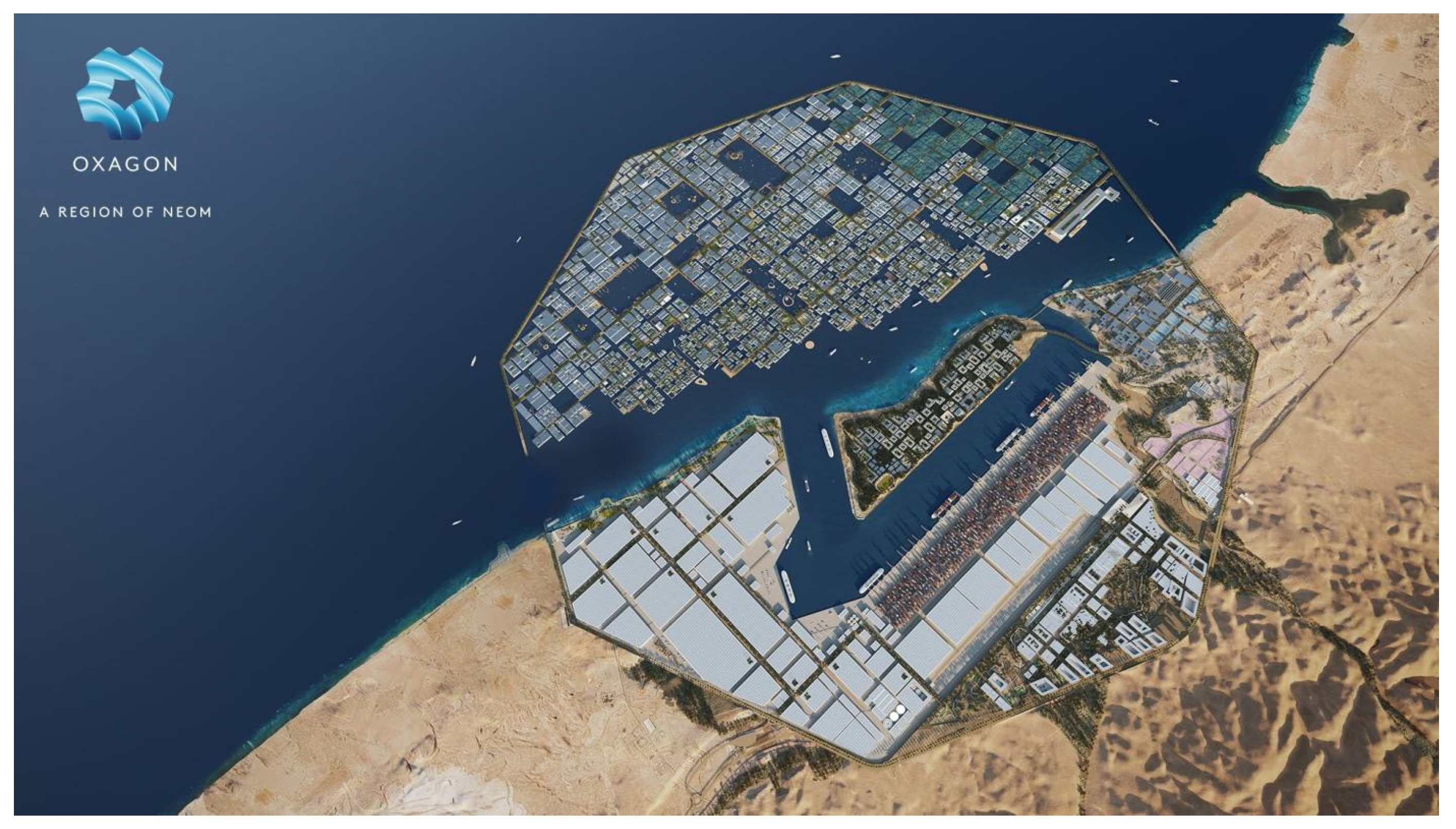

One of the major initiatives led by Saudi Arabia, in this context, is the development of Neom (meaning a new future), a new 170 km long linear urban city, being referred to as ‘The Line’ (

NEOM 2021). The Saudi Arabian government has allocated USD 500 billion to the investment (

Reuters 2021) for the new oxagon city (

Figure 1), which is strategically located on the coast of the Red Sea (

Uddin 2021), where 13% of the international trade flows and is a location to which more than 40% of the world’s population can reach with less than a four-hour flight (

Arab News 2021), having good potential for promoting tourism and trade. The city is designed for more than one million international and local residents, with a concept of living in harmony with nature and relying 100% on clean energy (

Bostock 2021;

NEOM 2021). Various developments are planned, such as a dinosaur park island with robotic dinosaurs and a city for entrepreneurs and start-ups for leading research, innovation, and development by deploying advanced artificial intelligence technologies (

NEOM 2021) to attract tourism and immigration of skilled and enthusiastic entrepreneurs. Though the objectives reflect this as a megaproject, which is similar to the developments led in Dubai over a decade ago (

Al-Saleh 2017), there could be various types of impacts on the local culture and lifestyles of the people with an increase in internationalisation. While few studies argue that the UAE has successfully balanced the local culture and international culture by easing restrictions, modifying policies and norms for increasing investors, foreign direct investments (FDIs), and promoting tourism, others reflect this approach as side-lining local culture and tradition and, hence, adopting western culture to promote growth and development (

Jaafar 2020;

Stephenson and Ali-Knight 2010;

Zaidan 2016). While few hosts supported international culture, few opposed it; and others argued that the development of lines of luxury has increased the cost of living (

Stephenson and Ali-Knight 2010;

Zaidan 2019;

Zaidan and Kovacs 2017).

In a similar context, it is very much essential for Saudi Arabia to define the approach toward cultural diversification, promotion of fashion, international culture, and lifestyles in the proposed initiatives, such as Neom city, which is planned for the world. Leading such an initiative would definitely have an impact on the local people’s cultures, fashion, and lifestyles. A recent study (

Semaan et al. 2019) has identified that Gulf Arab women displayed a number of independent and agentic behaviours in their luxury consumption, which contrasts with their social role in the Gulf Arab society, which is often more communal and interdependent. Therefore, in developing social norms in a culturally diverse city, it is important to understand female perceptions and attitudes towards fashion luxury brands, which can help in devising plans for the socio-cultural integration of diverse people. However, there is a lack of research in this context (

Alosaimi et al. 2020), especially in understanding the Saudi females’ perception of luxury brands, as it is an important area that can influence local culture and lifestyles in a country that has a long history of strict socio-cultural norms. Understanding these attitudes can help the decision-makers in developing plans for balancing various cultures and lifestyles, along with Saudi culture, which plays an important role in the development of the city in the future. In this context, the purpose of this study is to identify and evaluate the factors influencing Saudi young females’ luxury fashion, which can act as predeterminants of culture and lifestyles in Neom city.

2. Literature Review

As the nature of luxury is constantly changing with the frequent development of new and innovative products and services, it is difficult to derive a universal definition for a luxury brand. However, researchers have used various terminologies for defining and understanding luxury brands from different perspectives. Luxury brands can be understood from different facets. For example, an expressive facet can be related to the exclusivity of luxury brands; an impressive facet that can be related to premium quality; and an impressive emotional facet that can be related to extraordinary aesthetic aspects (

Hudders et al. 2013). In addition, from a societal perspective, luxury brands can be related to the wealthy, affluent, and powerful (

Atwal and Williams 2017). However, with the rising socio-economic status of citizens in few countries, luxury brands are no more considered as privileges of the wealthy but as accessible to a wide range of people who are not necessarily wealthy but influenced by many factors, such as quality, design, durability, and who are ready to spend huge, being motivated by various factors (

Atwal and Williams 2017). Luxury consumption, unlike in the past, has undergone various changes along with changes in lifestyles. For example, the new market segment of the luxury market now includes younger and affluent people who are more involved in enjoying life and are inclined to be spendthrifts (

Ko et al. 2019;

Morhart et al. 2020;

Jhamb et al. 2020).

There are various purchase motivational factors identified in the literature review, which mainly focused on selection and seduction (

Kapferer and Valette-Florence 2016). The preferences for luxury brands can be related to the consumers’ satisfaction with their social goals, such as making an impression, connecting with people, attention-seeking, etc. It was identified that dissatisfaction with one social goal may promote their expectation of the satisfaction of another social goal, reflecting their inclination toward luxury brands (

Zhang et al. 2019). It was identified that consumers may adopt other approaches, such as renting luxury brands rather than buying, in order to fulfil their satisfaction with social goals (

Pantano and Stylos 2020). However, the main drivers for purchase motivation are related to socio-economic factors of the people. It was identified that financial freedom and market efforts were identified to be the main drivers of luxury brand sales in emerging markets (

Sharma et al. 2020). In addition, rising social interactions on online social platforms were also identified as being related to the consumers’ relationship and purchase intentions with luxury brands (

Oliveira and Fernandes 2020). In addition, the exclusivity factor, such as a unique dress or handbag being owned, which highlights them as unique and being the first among their peers to own a luxury item, was considered to be another purchasing motivational factor (

Dubois et al. 2021). Studies (

Farrag 2017;

Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie 2018;

Ünal et al. 2019) also identified that the age group of consumers (young) and gender (females) were significantly correlated with purchase intentions of luxury brands.

From a brand perspective, the luxury brand’s image, services offered, up-to-date fashion, facilitating an enjoyable shopping experience, and the brand effect, were identified as the major attributes which can influence people’s relationship with a luxury brand (

Akbar et al. 2020). Innovative technologies, such as chatbots are being used by luxury brands to provide an enhanced and enjoyable shopping experience for their customers (

Chung et al. 2020). There are also other factors that may influence the association with and purchases of luxury brands, for example, celebrity endorsement of luxury brands (

Bazi et al. 2020;

Cuomo et al. 2019), family and friends (

Siddiqui et al. 2019), and social media (

Arrigo 2018) can influence peoples’ association with luxury brands.

Based on the literature reviewed, various perceptions about luxury brands are identified, which include quality, high price, bought by the successful, bought by the wealthy, latest designs, and high durability.

In addition, eight motivational factors, six store factors, and six external factors, as shown in

Figure 2, were identified to be influencing the individuals in purchasing luxury brands. These influencing factors reflect the psychological aspects, such as motivation, attraction to designs, or influence by celebrities. There are also other influencing factors, such as financial conditions, social life (marital status), etc. However, this study only considers the factors that have a psychological impact on the consumers, because it is complex to integrate a large number of influencing factors into questionnaires and analyses.

4. Results and Discussion

Participants’ demographic information is presented in

Table 1. It can be observed that the majority of the participants in the study were employed (59.6%), and there were a considerable number of participants who were unemployed (40.4%). Focusing on the age groups, the majority of the participants belonged to the 23–27 age group (47.5%), followed by 32.9% in the 18–22 years age group and 19.6% in the 28–32 years age group. Focusing on educational levels, 64.6% of the participants were educated, which included 29.4% of the participants who held a master’s degree, 29.1% with a bachelor’s degree, 4.7% with a diploma or other education, and 1.4% of the participants had doctorates. A considerable number of participants (35.4%) were uneducated. The majority of the participants belonged to the central and western regions, and the remaining were almost equally distributed across the north, east, and southern regions of Saudi Arabia.

Various aspects, such as quality, price, consumer types, design, and durability, were used in different studies (

Atwal and Williams 2017;

Hudders et al. 2013;

Jhamb et al. 2020;

Ko et al. 2019;

Morhart et al. 2020) in understanding the luxury brands. The findings observed in this study (

Table 2) revealed that the majority of the participants perceived that luxury brands can be related to quality, price, design, and durability. However, the majority of them disagreed with the type of consumers with whom the luxury brands are associated with. Luxury brands, being associated with the wealthy (Mean = 2.9, SD = 4.27) and successful (Mean = 2.3, SD = 3.16) reflected the neutral nature and little disagreement, respectively, among the participants. These findings can be related to (

Wu et al. 2015) identifying the change in the consumers of luxury brands, who now include the strawberry generation.

Various motivational factors were identified in studies (

Kapferer and Valette-Florence 2016;

Pantano and Stylos 2020;

Zhang et al. 2019) which influenced purchasing decisions of luxury brands. Findings in this study, however, revealed that personal happiness (Mean = 4.5, SD = 1.47) was the strongest motivational factor, followed by making good impressions (Mean = 3.8, SD = 1.25), and being the centre of attraction among peers (Mean = 3.8, SD = 4.63). These findings were similar to (

Dubois and Czellar 2002) who identified ‘self-indulgence’ and ‘sense of being important’ as the major motivational factors. However, ‘being centre of attraction’ reflected a difference of opinions with few participants considering it as a negative motivational factor, as evident from the large variance in SD. Showing off (Mean = 2.7, SD = 1.87) is the least motivational factor identified in the study. However, findings in (

Wu et al. 2015) revealed that female participants reflected that they enjoy attention-seeking, and would like to best present themselves. In addition, other motivational factors and their influence can be observed in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. Findings related to motivational factors among young females reflected a sense of personal happiness and modesty in owning luxury brands, and they are not associated with showing off or attention-seeking.

By further analysing the motivational factors by education, significant differences were identified with respect to the influence of motivational factors on purchasing luxury brands, as shown in

Table 3. The mean scores of educated participants (Mean = 4.1, SD = 1.91) and uneducated participants (Mean = 2.8, SD = 2.59), identified in the analysis, reflected educated participants were positively motivated and the uneducated were negatively motivated in relation to the presented motivational factors (

Table A1). The

t-value, as shown in

Table 3, was found to be

t = 7.9563 at a 0.05 confidence interval, and was identified to be statistically significant (

p < 0.0001).

The results were further analysed by employment, which reflected similar results as shown in

Table 4. The mean scores of employed participants (Mean = 3.9, SD = 2.13) and uneducated participants (Mean = 3.0, SD = 2.37), identified in the analysis, reflected that employed participants were positively motivated and the unemployed were less positively motivated in relation to the presented motivational factors (

Table A1). The

t-value, as shown in

Table 4, was found to be

t = 5.5129 at a 0.05 confidence interval, and was identified to be statistically significant (

p < 0.0001).

Studies (

Akbar et al. 2020;

Chung et al. 2020) identified various store features, such as brand image, exclusiveness, services offered, and experience provided, which can influence the luxury brand consumers. Accordingly, various items related to the store features presented in the questionnaire were designed in a way that they can be applicable for both online and offline stores, as presented in

Table A2 in

Appendix A. Overall, the up-to-date fashionable experience (Mean = 4.3, SD = 1.31) and reputation (Mean = 4.3, SD = 1.38) factors reflected a strong influence on the participants. All other factors also were identified to be having a strong influence (Mean > 3.8), and the low SDs reflected similar and collective opinions held by the participants. The findings related to the store factors were identified to be similar to (

Dubois and Czellar 2002;

Fairhurst and Gentry 1989;

Wu et al. 2015).

By further analysing the store factors by education, significant differences were identified with respect to the influence of store factors on purchasing luxury brands, as shown in

Table 5. The mean scores of educated participants (Mean = 4.3, SD = 1.59) and uneducated participants (Mean = 3.8, SD = 1.15), identified in the analysis, reflected both educated and uneducated participants as being positively influenced in relation to the presented store factors (

Table A2). The

t-value, as shown in

Table 5, was found to be

t = 4.5895 at a 0.05 confidence interval, and was identified to be statistically significant (

p < 0.0001). However, slight differences can be observed in their opinions related to various store factors. While employed participants preferred reputation, after sale experience, and up-to-date fashionable merchandise, the unemployed participants preferred shopping experience and customer services.

By further analysing the store factors by employment, significant differences were identified with respect to the influence of store factors on purchasing luxury brands, as shown in

Table 6. The mean scores of employed participants (Mean = 4.4, SD = 1.62) and unemployed participants (Mean = 3.7, SD = 1.12), identified in the analysis, reflected that both the employed and unemployed participants were positively influenced in relation to the presented store factors (

Table A2). The

t-value, as shown in

Table 6, was found to be

t = 6.6436 at a 0.05 confidence interval, and was identified to be statistically significant (

p < 0.0001). However slight differences can be observed in their opinions related to various store factors. While educated participants preferred reputation, customer service, and up-to-date fashionable merchandise, the unemployed participants preferred shopping experience and exclusiveness.

Studies (

Arrigo 2018;

Bazi et al. 2020;

Cuomo et al. 2019;

Siddiqui et al. 2019) identified various external factors influencing the purchasing decisions of luxury brands, which included celebrity branding, family, and friends, culture, etc. Two additional factors, including religion and social norms, were included in the context of Saudi Arabia. The findings revealed that celebrity branding (Mean = 3.9, SD = 1.19) and friends (Mean = 3.5, SD = 1.83) were the strongest positive influencing factors; while all other factors, including family, religion, social norms, and culture, were identified to be reflecting a slightly negative influence on the purchase decisions of luxury brands by the participants. The findings are similar to (

Semaan et al. 2019), which identified that the fashion trends and opinions reflected by Gulf women were in contrast with their culture and social norms.

By further analysing the external factors of education, no significant differences were identified with respect to the influence of the external factors on purchasing luxury brands, as shown in

Table 7. The mean scores of educated participants (Mean = 2.8, SD = 1.41) and uneducated participants (Mean = 2.9, SD = 1.35), identified in the analysis, reflected that both educated and uneducated participants were negatively influenced in relation to the presented external factors (

Table A3). The

t-value, as shown in

Table 7, was found to be

t = 0.9589 at a 0.05 confidence interval, and was identified to be not statistically significant (

p = 0.3383,

p > 0.05).

By further analysing the external factors of employment, no significant differences were identified with respect to the influence of external factors on purchasing luxury brands, as shown in

Table 8. The mean scores of employed participants (Mean = 3.0, SD = 1.61) and unemployed participants (Mean = 2.7, SD = 1.15), identified in the analysis, reflected that both employed and unemployed participants were less positively influenced in relation to the presented external factors (

Table A3). The

t-value, as shown in

Table 8, was found to be

t = 2.8416 at a 0.05 confidence interval, and was identified to be statistically significant (

p < 0.05).

However, slight differences can be observed in their opinions related to various external factors. While employed participants presented celebrities and friends to have a positive influence; unemployed participants reflected family, social norms, and religion to be having a negative influence on their purchasing of luxury brands.

The findings have revealed that various influencing factors have a different impact on different groups of Saudi females, categorised by age, education, and employment. Therefore, more detailed future studies are required in this area in order to understand the impact of various factors on Saudi females’ perceptions of purchasing luxury brands. Accordingly, future studies may investigate the impact of other influential factors, such as financial and social factors, on both male and female perceptions and attitudes towards luxury brands’ shopping.

This study has both theoretical and practical implications. Firstly, this study contributes to the literature by identifying the various factors influencing the purchasing of luxury brands, which were categorised under motivational, store, and external factors. In addition, this study addresses the research gaps (lack of research on the female attitudes towards luxury brands in Saudi Arabia), thereby providing a valuable contribution to the literature, which can guide future research. Moreover, the findings can help the decision-makers better understand the females’ perceptions of luxury brands, which can enable them to the effective planning of the new initiatives in the newly proposed city of Neom, by carefully balancing diverse cultures along with Saudi culture.

However, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, this study only considered the female adult population in Saudi Arabia as the sample, excluding both males and females under the age of 18 years who may also become influenced by luxury brands. Secondly, this study used only a survey as a research strategy for collecting the data. As the study included psychological factors, a mixed-methods approach that included both surveys and interviews, could have improved the quality of findings. Therefore, the generalisation of findings in this study must be done with care in future studies.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to identify and evaluate various factors influencing young female consumers’ luxury fashion in Saudi Arabia. The luxury brand is related in terms of quality, price, the latest designs, and high durability in Saudi Arabia, whereas the perception that luxury is intended for the wealthy and affluent, was identified to be irrelevant. Focusing on the motivational factors and store factors influencing the purchase of luxury brands, significant differences were observed between the groups (educated and uneducated; employed and unemployed), reflecting varying opinions and perceptions relating to luxury fashion. However, there were no significant differences between the educated and uneducated identified in relation to the influence of external factors, however, differences were identified among the employed and unemployed. Findings revealed that there is a strong influence of external factors, such as social norms, religion, culture, and family on the young female consumers’ luxury fashion in Saudi Arabia.

Thus, this study identified various influencing factors of young female consumers regarding luxury fashion and evaluated them. These findings can be used as predeterminants for designing the socio-cultural norms, culture, and lifestyles in Neom city, which is proposed to accommodate more than one million residents, including both international and local Saudi Arabian citizens. There are a few limitations observed in this study. Firstly, this study adopted a survey instrument for data collection. Using additional methods, such as case study comparison, and qualitative interviews can lead to a collection of quality data, which can enable a better analysis of young Saudi females’ opinions from different perspectives. In addition, the sample consisted only of females; however, it can be further extended with a mixed sample in future studies.