External vs. In-House Advising Service: Evidence from the Financial Industry Acquisitions †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Financial Advisors

2.2. Financial Acquirers in the M&A Market

3. Sample and Variables

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Selection

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Advisory Services: External vs. In-House

3.2.2. Control Variables

3.2.3. Regression Methodology and Wealth Gains in M&As

4. Empirical Results

4.1. The Choice of External vs. In-House Advisory Services

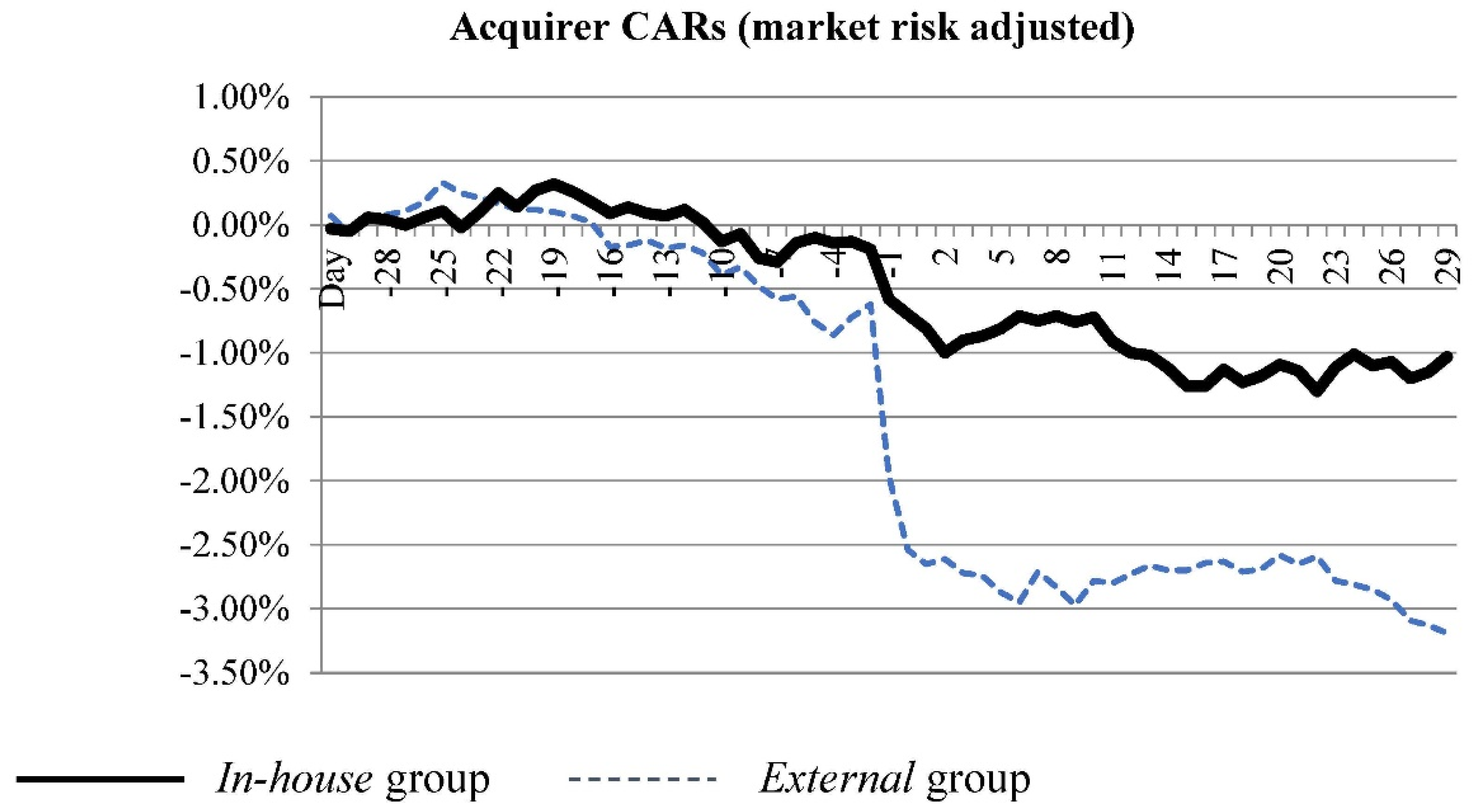

4.2. Deal Outcomes—Market Returns and Completion Rate

4.3. Market Returns to the Acquirers

4.4. Wealth Redistribution and Allocation Efficiency

4.5. Deal Completion Rate

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This study is different from the prior literature on choices of advisory services in two ways. First, we focus on the players in the financial services industry only, who are “insiders” in the financial market and may be more experienced and professional in the M&A process. Therefore, it is uncertain whether external advisors may offer incremental benefits to the financial players, such as improving the completion rate, increasing market abnormal returns, etc. Second, this study focuses on the choices of acquirer advisors, not target advisors. The conflict of interests between the acquirer and their advisor is more pronounced than that between the target firm and the advisor. Usually, the advisory fee is contingent on deal completion and the magnitude of the advisory fee is largely tied to the transaction value (McLaughlin 1990, 1992). Therefore, the acquirer’s advisor prefers a higher offer price to lock the deal whereas the acquirer would benefit by paying less in the acquisition. The situation is simpler on the target side because the incentives of the target firm and their advisor are aligned—both are willing to accept a higher offer price. Overall, the acquirers in the financial service industry provide a unique setting to investigate the cost and benefits of external vs. in-house advisory services in the M&A process. |

| 2 | The volume of the financial M&A market post financial crisis was low partially due to the Dodd–Frank Act which was enacted in 2010, and our sample ends in 2010 as well. In response to the financial crisis, the US enacted the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd–Frank Act). A major impact of the Dodd–Frank Act on the M&A market is the size threshold. It requires the Federal Reserve to establish regulatory standards based on individualized risk analysis for bank holding companies with assets greater than USD 50 billion. In other words, large banks with a size above USD 50 billion are facing more strict regulation and monitoring compared to smaller financial companies. Therefore, the incentive of the scale of economics is dampened with the threshold. In fact, bank or financial holding companies were reluctant to size up or merge, since doing so will move them up to the “above 50 billion thresholds” category. Thus, while extending the sample period into the post-crisis period provides the limited benefit of increased sample size, it will create a sample selection bias for the post-crisis deals. Large or complicated M&As where financial advisors provide the most benefits are less likely to occur in the first place. Such selection bias will be a confounding issue affecting our analysis of the impact of financial advisors on deals valuation. |

| 3 | Cain and Denis (2013) mention that the acquirer-side advisor information is sometimes unobservable in tender-offer deals even if an advisor is retained. Also see regulation M-A, Section 1012(b) for detailed requirements of information disclosure in tender offers. |

| 4 | The distribution of transaction values is highly skewed. Therefore, we convert the transaction value into log format in the regressions to eliminate biases. |

| 5 | The market timing theory in the M&A market is explained in Shleifer and Vishny (2003), and Rhodes-Kropf et al. (2005). The acquirer uses its overvalued stock to purchase the target, driving poor long-run acquirer stock performance due to the correction of misvaluation. |

| 6 | It is also possible that over-confident managers go out of state and believe they can handle the deal themselves. However, our regression result (Table 5) shows that in-house deals of financial firms, overall, have higher quality. |

| 7 | Kisgen et al. (2009) argue that managers of the acquirers obtain fairness opinions from financial advisors to protect themselves against potential lawsuit triggers by the outcome or performance of the M&As. Thus, investors are skeptical of such transactions and the acquirer’s announcement return is 2.3% lower. |

References

- Allen, Linda, Julapa Jagtiani, Stavros Peristiani, and Anthony Saunders. 2004. The role of bank advisors in mergers and acquisition. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 36: 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Yakov, Baruch Lev, and Nickolaos G. Travlos. 1990. Corporate control and the choice of investment financing: The case of corporate acquisitions. The Journal of Finance 45: 603–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, Alin Marius, Sabina Cazan, and Nicu Sprincean. 2021. Determinants of Bank M&As in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, Ioannis, and Panayiotis Athanasoglou. 2013. Revisiting the merger and acquisition performance of European banks. International Review of Financial Analysis 29: 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, Paul, Robert F. Bruner, and David W. Mullins, Jr. 1983. The gains to bidding firms from merger. Journal of Financial Economics 11: 121–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Jack, and Alex Edmans. 2011. Do investment banks matter for M&A returns? Review of Financial Studies 24: 2286–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Keldon J., Linda L. Miles, and Takeshi Nishikawa. 2009. The effect of mergers on credit union performance. Journal of Banking & Finance 33: 2267–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Allen N., and Timothy H. Hannan. 1998. The Efficiency Cost of Market Power in the Banking Industry: A Test of the “Quiet Life” and Related Hypotheses. The Review of Economics and Statistics 80: 454–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Philip G., and Eli Ofek. 1995. Diversification’s effect on firm value. Journal of Financial Economics 37: 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, Audra L., and J. Harold Mulherin. 2008. Do auctions induce a winner’s curse? New evidence from the corporate takeover market. Journal of Financial Economics 89: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, Helen M., and Robert E. Miller. 1990. Choice of investment banker and shareholders wealth of firms involved in acquisitions. Financial Management 19: 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Michael, Anand Desai, and E. Han Kim. 1988. Synergistic gains from corporate acquisitions and their division between the stockholders of target and acquiring firms. Journal of Financial Economics 21: 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Elijah, III, and Julapa Jagtiani. 2013. How Much Did Banks Pay to Become Too-Big-To-Fail and to Become Systemically Important? Journal of Financial Services Research 43: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, Matthew, and David J. Denis. 2013. Information Production by Investment Banks: Evidence from Fairness Opinions? The Journal of Law and Economics 56: 245–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Xin, Chander Shekhar, Lewis H. K. Tam, and Jiaquan Yao. 2016. The information role of advisors in mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from acquirers hiring targets’ ex-advisors. Journal of Banking & Finance 70: 247–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Fang, Jian Huang, Minghui Ma, and Han Yu. 2021. In-house deals: Agency and information asymmetry perspectives. Corporate Ownership & Control 18: 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, Gayle L. 2001. Stockholder gains from focusing versus diversifying bank mergers. Journal of Financial Economics 59: 221–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, Robert, Douglas D. Evanoff, and Philip Molyneux. 2009. Mergers and acquisitions of financial institutions: A review of the literature. Journal of Financial Services Research 36: 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Lijing, and Jian Huang. 2015. What determines M&A advisory fees? Southern Business & Economic Journal 38: 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Golubov, Andrey, Dimitris Petmezas, and Nickolaos G. Travlos. 2012. When It Pays to Pay Your Investment Banker: New Evidence on the Role of Financial Advisors in M&As. The Journal of Finance 67: 271–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Jie (Michael), Yichen Li, Changyun Wang, and Xiaofei Xing. 2020. The role of investment bankers in M&As: New evidence on Acquirers’ financial conditions. Journal of Banking & Finance 119: 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankir, Yassin, Christian Rauch, and Marc Umber. 2011. Bank M&A: A market power story? Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 2341–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, Joel F., Christopher M. James, and Michael D. Ryngaert. 2001. Where do merger gains come from? Bank mergers from the perspective of insiders and outsiders. Journal of Financial Economics 60: 285–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, William C., and Julapa Jagtiani. 2003. An analysis of advisor choice, fees, and efforts in mergers and acquisitions. Review of Financial Economics 12: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, William C., and Mary Beth Walker. 1990. An empirical examination of investment banking merger fee contracts. Southern Economic Journal 56: 1117–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Ahmad. 2010. Are good financial advisors really good? The performance of investment banks in the M&A market. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 35: 411–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, Narayanan, Ajay Khorana, and Edward Nelling. 2002. An Analysis of the Determinants and Shareholder Wealth Effects of Mutual Fund Mergers. The Journal of Finance 57: 1521–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, Jayant R., Omesh Kini, and Harley E. Ryan. 2003. Financial Advisors and Shareholder Wealth Gains in Corporate Takeovers. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38: 475–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisgen, Darren J., Jun “QJ” Qian, and Weihong Song. 2009. Are fairness opinions fair? The case of mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics 91: 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, Morris, Alan Gart, and David Becher. 2005. Post-Merger Performance of Bank Holding Companies, 1987–1998. The Financial Review 40: 549–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. 2021. 2021 Was a Blowout Year for M&A—2022 Could Be Even Bigger. Available online: https://advisory.kpmg.us/articles/2021/blowout-year-global-ma.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Krishnan, C. N. V., and Jialun Wu. 2022. Market Misreaction? Evidence from Cross-Border Acquisitions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, C. N. V., and Vasiliy Yakimenko. 2022. Market Misreaction? Leverage and Mergers and Acquisitions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, Steven D., and Stephen J. Dubner. 2009. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. New York: William Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, Marcus M. Opp, and Farzad Saidi. 2016. Target revaluation after failed takeover attempts: Cash versus stock. Journal of Financial Economics 119: 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Robyn M. 1990. Investment-banking contracts in tender offers: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics 28: 209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Robyn M. 1992. Does the form of compensation matter? Investment banker fee contracts in tender offers. Journal of Financial Economics 32: 223–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, Allen, Israel Shaked, and You-Tay Lee. 1991. An evaluation of investment banker acquisition advice: The shareholders’ perspective. Financial Management 20: 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, Randall, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1990. Do managerial objectives drive bad acquisitions? The Journal of Finance 45: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. 2021. Global M&A Trends in Financial Services: 2022 Outlook. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/deals/trends/financial-services.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Rau, P. Raghavendra. 2000. Investment bank market share, contingent fee payments, and the performance of acquiring firms. Journal of Financial Economics 56: 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinitiv. 2021. Global Mergers & Acquisitions Review; Full Year 2021. Available online: https://thesource.refinitiv.com/TheSource/getfile/download/eacef8be-ef5d-4335-b807-5db0db1cf6bc (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Rhodes-Kropf, Matthew, David T. Robinson, and S. Viswanathan. 2005. Valuation waves and merger activity: The empirical evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 77: 561–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, Henri, and Marc Zenner. 1996. The role of investment banks in acquisitions. The Review of Financial Studies 9: 787–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1986. Large shareholders and corporate control. The Journal of Political Economy 94: 461–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 2003. Stock market driven acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics 70: 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Brian W., and Laura R. Biddle. 2005. Is the Bank Merger Regulatory Review Process Ripe for Change? Bank Accounting and Finance 18: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Weihong, Jie (Diana) Wei, and Lei Zhou. 2013. The value of “boutique” financial advisors in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance 20: 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, Alix N. 2006. Are Your Secrets Safe? CFO Magazine. October 1. Available online: https://www.cfo.com/banking-capital-markets/2006/10/are-your-secrets-safe/ (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Stulz, Rene M., Ralph A. Walkling, and Moon H. Song. 1990. The distribution of target ownership and the division of gains in successful takeovers. The Journal of Finance 45: 817–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travlos, Nicholaos G. 1987. Corporate takeover bids, methods of payment, and bidding firms’ stock returns. The Journal of Finance 42: 943–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zámborský, Peter, Zheng Joseph Yan, Erwann Sbaï, and Matthew Larsen. 2021. Cross-Border M&A Motives and Home Country Institutions: Role of Regulatory Quality and Dynamics in the Asia-Pacific Region. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| ADV | is whether the acquirer hires an external advisor or retains the advisory services in-house: 1 = in-house; 0 = external. |

| ACQ_CAR | is the acquirer’s 3-day (−1, +1) cumulative abnormal returns. |

| TGT_CAR | is the target’s 3-day (−1, +1) cumulative abnormal returns. |

| CCAR | is the weighted sum of the acquirer and target CARs. |

| Complete | is the percentage that measures the likelihood that the deal is complete. |

| Ln(Val) | is the log of the dollar value of the transaction. |

| RelAsset | is the ratio of target asset to acquirer asset in the prior fiscal year. |

| RelEquity | is the ratio of target market capitalization over acquirer market capitalization 30 days before the merger announcement. |

| StockPay | is the payment method of the deal: 1 = the deal is at least 50% paid by stock; 0 = otherwise. |

| Prior | is the number of mergers completed by the acquirer during the prior 10 years. |

| SameST | is whether the acquirer and the target are headquartered in the same state: 1 = same state; 0 = otherwise. |

| SameIND | is whether the acquirer and the target have the same first 3-digit SIC code: 1 = same first 3-digit SIC code; 0 = otherwise. |

| #Bidder | is the number of bidders participating in the transaction. |

| Toehold | is the percentage of target shares owned by the acquirer prior to the merger announcement. |

| TGT_M/B | is the ratio of the market value of equity relative to the book value of equity of the target in the prior fiscal year. |

| ACQ_M/B | is the ratio of the market value of equity relative to the book value of equity of the acquirer in the prior fiscal year. |

| TGT_ROE | is the return on equity of the target in the prior fiscal year. |

| TGT_ROA | is the return on asset of the target in the prior fiscal year. |

| TGT_SGR | is the difference between the sales of the fiscal years (t − 1) and (t − 2) scaled by the sales of fiscal year (t − 2). |

| TGT_IGR | is the difference between the net income of the fiscal years (t − 1) and (t − 2) scaled by the net income of fiscal year (t − 2). |

| TGT_EQU | is the equity ratio of the target, which is the ratio of equity to liability. |

| Panel A: Frequency of External vs. In-House Advisory Services | ||||||||

| Advisory Services | Financial M&A Deals | |||||||

| External | 443 | 60.6% | ||||||

| In-house | 288 | 39.4% | ||||||

| Total Number | 731 | 100% | ||||||

| Panel B: Top 10 Acquisition Transactions in the External vs. In-House Group (by Size of the Transactions) | ||||||||

| External | In-House | |||||||

| Acquirer | Target | Year | Transaction Value (mil) | Acquirer | Target | Year | Transaction Value (mil) | |

| 1 | BANC ONE | First Chicago NBD | 1998 * | 29,616.04 | Travelers Group Inc. | Citicorp | 1998 * | 72,558.18 |

| 2 | AIG | American General Corp | 2001 | 23,398.16 | NationsBank Corp | Bank of America | 1998 * | 61,633.40 |

| 3 | Firstar Corp | US Bancorp | 2000 | 21,084.87 | JPMorgan Chase | BankOne Corp | 2004 | 58,663.15 |

| 4 | AIG | SunAmerica Inc. | 1998 | 18,116.98 | Bank of America | FleetBoston Financial Corp | 2003 | 49,260.63 |

| 5 | First Union Corp | CoreStates Financial | 1997 | 17,122.23 | Bank of America | Merrill Lynch | 2008 | 48,766.15 |

| 6 | St Paul Companies Inc. | Travelers Property Casualty Corp | 2003 * | 16,136.14 | Bank of America | MBNA Corp | 2005 | 35,810.27 |

| 7 | Fleet Financial Group | BankBoston Corp | 1999 | 15,925.20 | Chase Manhattan Corp | JP Morgan & Co Inc. | 2000 | 33,554.58 |

| 8 | Bank of New York | Mellon Financial | 2006 | 15,679.63 | Citigroup Inc. | Associates First Capital Corp | 2000 | 30,957.50 |

| 9 | Capital One Financial Corp | North Fork Bancorp | 2006 | 15,132.87 | Wachovia Corp | Golden West Financial Corp | 2006 | 25,500.89 |

| 10 | Washington Mutual | HF Ahmanson & Co | 1998 | 14,724.96 | Berkshire Hathaway Inc. | General Re Corp | 1998 | 22,300.17 |

| External | In-House | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | N | |

| Complete | 94% | - | - | - | 443 | 95.30% | - | - | - | 288 |

| Ln(Val) | 5.81 | 5.57 | 2.26 | 10.29 | 443 | 5.17 | 4.9 | 2.03 | 11.19 | 288 |

| Acquire asset (Bil) | 35.245 | 6.423 | 0.48 | 543.605 | 396 | 100.255 | 16.588 | 0.115 | 1884.318 | 262 |

| Target asset (Bil) | 6.547 | 1.036 | 0.45 | 196.446 | 418 | 7.982 | 0.646 | 0.04 | 326.563 | 261 |

| RelAsset | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.0015 | 4.785 | 375 | 0.11 | 0.046 | 0.0002 | 1.06 | 241 |

| RelEquity | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.002 | 5.1 | 443 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.0004 | 1.41 | 288 |

| % of StockPay | 80% | 100% | - | - | 443 | 74% | - | - | - | 288 |

| Prior | 1.59 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 443 | 3.52 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 288 |

| % of SameIND | 59% | - | - | - | 443 | 50% | - | - | - | 288 |

| % of SameST | 44.99% | - | - | - | 443 | 32% | - | - | - | 288 |

| #Bidder | 1.06 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 443 | 1.01 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 288 |

| Toehold | 47% | 0% | 0% | 48.10% | 443 | 0.43% | 0% | 0% | 42% | 288 |

| ACQ_M/B | 2.4 | 1.94 | 0.05 | 29.12 | 396 | 2.36 | 2.06 | 0.06 | 11.33 | 262 |

| TGT_M/B | 1.85 | 1.6 | 0.55 | 12.59 | 417 | 1.71 | 1.52 | 0.34 | 6.46 | 261 |

| TGT_ROE | 11% | 11% | −110% | 56% | 417 | 11% | 11% | −47% | 32% | 261 |

| TGT_ROA | 1% | 1% | −86% | 46% | 417 | 1.40% | 1% | −32% | 20% | 261 |

| TGT_SGR | 16% | 11% | −52% | 281% | 400 | 11% | 8% | −82% | 124% | 238 |

| TGT_IGR | 19% | 11% | −814% | 1261% | 404 | 35% | 10% | −395% | 1030% | 241 |

| TGT_EQU | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.017 | 0.87 | 417 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 261 |

| ACQ_CAR | −0.02 | −0.015 | −0.28 | 0.28 | 443 | −0.007 | −0.008 | −0.155 | 0.16 | 288 |

| TGT_CAR | 0.16 | 0.13 | −0.27 | 0.91 | 443 | 0.194 | 0.159 | −0.1 | 1.04 | 288 |

| Dependent Variables: | Model I | Model II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADV: (0 = External; 1 = In-House) | Coefficient | Marginal Effect | p-Value | Coefficient | Marginal Effect | p-Value |

| RelEquity | −1.420 *** | −0.53 | 0.00 | |||

| RelAsset | −1.461 *** | −0.526 | 0.00 | |||

| Ln(Val) | −0.210 *** | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.262 *** | −0.09 | 0.00 |

| StockPay | −0.130 | −0.05 | 0.31 | −0.150 | −0.06 | 0.32 |

| Toehold | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.74 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.65 |

| Prior | 0.110 *** | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.123 *** | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| SameST | −0.310 *** | −0.12 | 0.00 | −0.382 *** | −0.14 | 0.00 |

| SameIND | −0.143 | −0.05 | 0.19 | −0.181 | −0.07 | 0.15 |

| ACQ_M/B | 0.050 | 0.02 | 0.21 | |||

| TGT_M/B | −0.024 | −0.01 | 0.76 | |||

| TGT_EQU | 0.250 | 0.09 | 0.64 | |||

| TGT_ROE | 1.032 | 0.37 | 0.20 | |||

| TGT_SGR | −0.940 *** | −0.34 | 0.00 | |||

| TGT_IGR | 0.063 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |||

| Observations | 731 | 577 | ||||

| Pseudo R-square | 20.3% | 25.32% | ||||

| Chi-square | 198.98 *** | 193.98 *** | ||||

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Panel A: Acquirer Three-Day (−1, +1) Cumulative Abnormal Returns | ||||||

| DV = ACQ_CAR | OLS | p-Value | Treatment | p-Value | ||

| ADV (External = 0; In-house = 1) | 0.009 ** | 0.06 | 0.045 ** | 0.00 | ||

| RelAsset | 0.016 *** | 0.00 | 0.022 *** | 0.00 | ||

| Ln(Val) | −0.004 | 0.00 | −0.001 | 0.56 | ||

| StockPay | −0.020 *** | 0.00 | −0.018 *** | 0.00 | ||

| Prior | 0.000 | 0.67 | −0.001 | 0.19 | ||

| SameIND | −0.003 | 0.41 | −0.001 | 0.87 | ||

| SameST | −0.009 ** | 0.05 | −0.004 | 0.48 | ||

| Toehold | 0.001 * | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.10 | ||

| #Bidder | −0.005 | 0.58 | −0.005 | 0.57 | ||

| ACT_M/B | −0.001 | 0.22 | −0.002 | 0.12 | ||

| TGT_M/B | 0.002 | 0.52 | 0.002 | 0.53 | ||

| TGT_EQU | 0.003 | 0.85 | 0.0004 | 0.98 | ||

| TGT_ROE | 0.011 | 0.66 | 0.0004 | 0.98 | ||

| TGT_SGR | 0.007 | 0.42 | 0.015 | 0.13 | ||

| TGT_IGR | −0.002 * | 0.18 | −0.002 * | 0.06 | ||

| Hazard ratio | −0.023 ** | 0.02 | ||||

| Observations | 546 | 546 | ||||

| R-square | 10.87% | 26.2% | ||||

| p-value of F-test | <0.000 | <0.000 | ||||

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Panel B: Target Three-Day (−1, +1) Cumulative Abnormal Returns | ||||||

| DV = TGR_CAR | OLS | p-Value | Treatment | p-Value | ||

| ADV (External = 0; In-house = 1) | 0.041 *** | 0.01 | 0.187 *** | 0.00 | ||

| RelAsset | −0.046 *** | 0.00 | −0.021 | 0.31 | ||

| Ln(Val) | 0.001 | 0.87 | 0.012 * | 0.09 | ||

| StockPay | −0.014 | 0.49 | −0.005 | 0.81 | ||

| Prior | −0.005 *** | 0.01 | −0.010 *** | 0.00 | ||

| SameIND | 0.011 | 0.46 | 0.021 | 0.18 | ||

| SameST | 0.012 * | 0.45 | 0.033 * | 0.08 | ||

| Toehold | −0.004 ** | 0.04 | −0.003 ** | 0.04 | ||

| #Bidder | −0.063 * | 0.08 | −0.062 | 0.07 | ||

| ACT_M/B | 0.008 | 0.09 | 0.005 | 0.23 | ||

| TGT_M/B | −0.021 ** | 0.01 | −0.021 *** | 0.01 | ||

| TGT_EQU | −0.112 * | 0.09 | −0.122 * | 0.07 | ||

| TGT_ROE | 0.146 | 0.11 | 0.104 | 0.28 | ||

| TGT_SGR | 0.059 ** | 0.07 | 0.090 *** | 0.01 | ||

| TGT_IGR | −0.002 | 0.64 | −0.004 | 0.29 | ||

| Hazard ratio | 0.092 ** | 0.01 | ||||

| Observations | 546 | 546 | ||||

| R-square | 17.14% | 26.2% | ||||

| p-value of F-test | <0.000 | <0.000 | ||||

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Panel C: Combined Three-Day (−1, +1) Cumulative Abnormal Returns | ||||||

| DV = CCAR | OLS | p-Value | Treatment | p-Value | ||

| ADV (External = 0; In-house = 1) | 0.005 | 0.20 | 0.022 | 0.11 | ||

| RelAsset | 0.029 *** | 0.00 | 0.034 *** | 0.00 | ||

| Ln(Val) | 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.002 | 0.20 | ||

| StockPay | −0.021 *** | 0.00 | −0.021 *** | 0.00 | ||

| Prior | −0.001 *** | 0.00 | −0.002 ** | 0.01 | ||

| SameIND | 0.005 | 0.21 | 0.005 | 0.19 | ||

| SameST | −0.001 | 0.83 | −0.001 | 0.74 | ||

| Toehold | 0.000 | 0.87 | 0.000 | 0.36 | ||

| #Bidder | −0.010 | 0.27 | −0.024 * | 0.05 | ||

| ACT_M/B | −0.005 *** | 0.00 | −0.005 *** | 0.00 | ||

| TGT_M/B | −0.001 | 0.78 | −0.002 | 0.42 | ||

| TGT_EQU | 0.003 | 0.85 | 0.001 | 0.94 | ||

| TGT_ROE | 0.032 | 0.16 | 0.032 | 0.19 | ||

| TGT_SGR | 0.015 * | 0.07 | 0.013 | 0.24 | ||

| TGT_IGR | −0.001 | 0.24 | −0.002 * | 0.06 | ||

| Hazard ratio | −0.013 | 0.21 | ||||

| Observations | 546 | 546 | ||||

| R-square | 19.62% | 26.2% | ||||

| p-value of F-test | <0.000 | <0.000 | ||||

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Panel D: Deal Completion Rate | ||||||

| DV = Complete | Model I | Model II | ||||

| Coefficient | Marginal Effect | p-Value | Coefficient | Marginal Effect | p-Value | |

| ADV (External = 0; In-house = 1) | −0.074 | −0.004 | 0.73 | −0.383 | −0.013 | 0.15 |

| RelEquity | −0.456 *** | −0.022 | 0.00 | |||

| RelAsset | −0.459 *** | −0.014 | 0.00 | |||

| Ln(Val) | −0.036 | −0.002 | 0.56 | −0.085 | −0.003 | 0.30 |

| StockPay | 0.437 ** | 0.027 | 0.03 | 0.533 ** | 0.023 | 0.04 |

| Prior | 0.043 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.054 | 0.002 | 0.17 |

| SameIND | 0.202 | 0.010 | 0.28 | 0.097 | 0.003 | 0.68 |

| SameST | 0.115 | 0.005 | 0.58 | 0.211 | 0.006 | 0.44 |

| Toehold | −0.019 | −0.001 | 0.32 | −0.023 | −0.001 | 0.38 |

| #Bidder | −1.106 *** | −0.052 | 0.00 | −1.1 *** | −0.033 | 0.00 |

| ACT_M/B | 0.058 | 0.002 | 0.52 | |||

| TGT_M/B | −0.009 | 0.000 | 0.94 | |||

| TGT_EQU | −0.041 | −0.001 | 0.96 | |||

| TGT_ROE | 1.163 | 0.035 | 0.37 | |||

| TGT_SGR | 0.254 | 0.008 | 0.67 | |||

| TGT_IGR | 0.124 | 0.004 | 0.17 | |||

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Observations | 731 | 577 | ||||

| Pseudo R-square | 27.99% | 36.06% | ||||

| Chi-square | 86.81 *** | 87.12 *** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z. External vs. In-House Advising Service: Evidence from the Financial Industry Acquisitions. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020066

Huang J, Yu H, Zhang Z. External vs. In-House Advising Service: Evidence from the Financial Industry Acquisitions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2023; 16(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020066

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jian, Han Yu, and Zhen Zhang. 2023. "External vs. In-House Advising Service: Evidence from the Financial Industry Acquisitions" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16, no. 2: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020066

APA StyleHuang, J., Yu, H., & Zhang, Z. (2023). External vs. In-House Advising Service: Evidence from the Financial Industry Acquisitions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020066