Abstract

This study documents the comparative financial performance of the Islamic Banking Services Industry (IBSI) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region. After drawing the performance evaluation framework (based on the CAMEL framework), the research conducted data analysis of the Islamic Banking Services Industry (IBSI) in the GCC region for 31 quarters (2013Q4–2021Q4). The analysis examines capital adequacy, asset quality, management performance, earnings, and liquidity management. Objectively classified data trends are reported through graphs. Additionally, the research documents internal determinants of financial performance. Findings suggest that the GCC-IBSI has shown overall progress in achieving primary objectives (commercial performance), including healthy capital adequacy, cost control, equity returns, and liquidity management. Capital adequacy, cost control, and liquidity management significantly contribute to financial performance. Managerial implications include cost control, reduction in non-performing loans, and prudent liquidity management. There exist opportunities in the GCC-IBSI for investors, given the mismatch in demand and supply of Islamic financial services. This study contributes to the literature by documenting findings on the achievements of the primary objective of IBSI in multiple GCC-IBSI markets comparatively.

JEL Classification:

G2; G21

1. Introduction

The Islamic Financial Services Industry (IFSI) aimed at Islamic Shari’ah compliance recently developed as a niche segment of the financial sector. The IFSI targets the segment of (primarily Muslim) consumers reluctant to use conventional financial services due to mismatch in religious teachings and practices of interest-based financial system. The IFSI is in practice since the last quarter of the 20th century with appreciable results as far as resilience and expansion are concerned. The IFSI turned out to be more resilient than its conventional counterparts during the recent global financial crisis (GFC) (Smolo and Mirakhor 2010; Siraj and Pillai 2012; Hanif and Zafar 2020). According to the Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report (IFSISR), by 2022, the industry size has reached a healthy amount of USD 3.25 trillion (IFSBr 2023). The IFSI and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) complement each other, given the overall philosophy of Islamic finance. Incorporation of Abrahamic religious values into the financial system is the aspiration of the IFSI (Abdulrahman 2010). Broader objectives of Islamic finance include Halal earnings, equitable wealth distribution, financial stability (Chapra 2008; and Ayub 2018), and socio-economic justice (Maudoodi 1941; Abdulrehman 2000). Also, a social role is expected from the IFSI, including corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Sairally 2007), promotion of social values (Obaidullah 2005), socially responsible investments, decrease in poverty (Asutay 2012), and environmental concerns (Saged et al. 2017).

Performance evaluation of an activity is aimed at documenting the results to identify weaker areas in light of preset objectives. However, clarity of objectives to be measured through the process is a prerequisite in developing the performance evaluation mechanism. There are established performance evaluation mechanisms for the conventional banking sector. The most widely used is the CAMELS rating system, which includes evaluation of the sufficiency of capital, strength and quality of assets, capabilities of management in operations, stability and trend in earnings, ability to discharge liabilities at due date, and sensitivity to internal and external events. Global rating agencies (Moody, Fitch, etc.) provide services to assess an institution’s financial soundness with the preset mandate of assessing commercial performance and financial stability without assessing the Shari’ah risk.

An interesting question is what additions to the existing CMAELS framework are needed to assess the performance of the Islamic Banking Services Industry (IBSI). The literature carries some appreciable efforts aimed at the performance evaluation of the IBSI. We may classify the studies into three groups.

- First is the financial performance evaluation of the IBSI using conventional models (e.g., see Hanif et al. 2012; Siraj and Pillai 2012; Islam and Ashrafuzzaman 2015; Hazman et al. 2018).

- The second stream of literature develops the performance evaluation mechanism for the IBSI in light of specific objectives of the Islamic financial system (Mohammed et al. 2008, 2015; Mergaliyev et al. 2021).

- Third is the development of Shari’ah compliance ratings mechanism for the IBSI—with a focus on IFSI objectives (Ashraf and Lahsasna 2017; Hanif 2018).

Specifically focusing on developing the performance evaluation framework of the IBSI, the literature suggests including specific Islamic finance objectives in addition to traditional measures of commercial performance. Hanif and Farooqi (2023) divide the concept into three sections/levels: primary, secondary, and advanced. The primary objectives include survival and commercial performance within Shari’ah constraints. The secondary objectives include broader economic impact, while the advanced objectives address social aspects.

The GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) region started Islamic finance in the last quarter of the 20th century. The GCC leads in the provision of Islamic financial services, with more than 50% of the global IBSI assets (IFSBr 2022). A significant number of studies exist on the comparative performance evaluation of the IBSI and conventional banking in the region (see inter alia, Samad 2004; AbuLoghod 2010; Siraj and Pillai 2012; Sillah and Harrathi 2015; Khokhar et al. 2020; Jaara et al. 2021; and BenSlimen et al. 2022). The overall results of these studies in the GCC region indicate equality in performance, if not better than the conventional industry. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study exists on comparative commercial/financial performance evaluation within IBSI markets in the GCC region for the review period.

The research aims to document the results of achievements of the primary Islamic finance objectives by the leading Islamic banking region, i.e., the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). There is a need for continuous documentation of achievements of multiple IBSI markets, given that the IBSI is rapidly growing, and more data are available yearly. Also, the focus of earlier studies on the documentation of comparative performance evaluation has remained within conventional and Islamic banking industries. There is a need to compare the performance of Islamic banking within IBSI markets. The research is expected to fill the gap in the literature by evaluating the comparative performance of the IBSI in the GCC markets, focusing on the achievements of primary objectives (commercial viability). Specifically, the research is intended to answer the following questions:

- Whether the IBSI in the GCC region is stable and carries sufficient capital to remain solvent in the long run (capital adequacy);

- To what extent is the IBSI successful in handling the credit risk (non-performing loans);

- What is the performance of the IBSI’s management (cost to income);

- Whether the IBSI remained successful in generating sufficient regular earnings for investors (return on equity);

- Whether the IBSI carries sufficient liquid assets to ensure short-term solvency (liquidity management); and

- Finally, to identify the significant internal contributors to the performance of the IBSI in the GCC region.

The methodology includes calculating financial ratios covering capital adequacy, asset quality, management performance, earnings, and liquidity management by utilising recent financial data for 33 quarters (2013Q4–2021Q4). Averages are compared by equality of means tests. Summary results are presented in tables. Historical trends of specific ratios are presented through graphs. In the second research phase, the internal determinants of profitability are documented. The results carry multiple interesting findings, including IBSI capital adequacy and liquidity management strengths.

2. Literature Review

Many studies have documented the empirical financial performance of the IBSI globally using available methods. We have evidence from Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), etc. Starting from Southeast Asia, few studies have compared the performance between conventional and Islamic banking. Using financial ratio analysis, Rosly and Abu Bakar (2003) documented superiority in profitability but was not supported by asset utilisation and investment margin after comparing the performance of Islamic and conventional banks in Malaysia (1996 to 1999). Rozzani and Rahman (2013) documented results for conventional and Islamic banking in Malaysia (2008–2011) through CAMELS, covering 35 banks (conventional 19, Islamic 16). The results indicate similarity in the performance with no significant difference. Another study on the Malaysian banking sector was conducted by Hazman et al. (2018). The sample included ten banks (five from each stream) for the period 2004–2016. As per the results, conventional banking outperforms Islamic banking in performance, based on the CAMEL model.

Another stream of studies has compared commercial performance between full-fledged Islamic banks and conventional banking Islamic windows. Kamaruddin et al. (2008) reported the results from Malaysia (for 1998–2004) on the performance of Islamic banking and conventional banking Islamic windows by application of data envelopment analysis (DEA). The results indicate relatively better cost efficiency than profit generation. In a recent study, Rasli et al. (2020) documented the comparatively better commercial performance and stability of full-fledged Islamic banks and Islamic subsidiaries of conventional banks for eight years (2010–2017). Full-fledged Islamic banks show better performance than subsidiaries of conventional banks. These results are mixed, containing better, equal, and worse performance compared with conventional banking.

A brief review of studies in the South Asian IBSI follows. Ahmad and Hassan (2007) reported comparative results from Bangladesh (1994–2001). Accordingly, Islamic banking leads in liquidity and capital adequacy, shows equality in asset quality, and lags in operating performance. Islam and Ashrafuzzaman (2015) documented similarity for both streams of banking in Bangladesh, by the application of CAMELS testing, in three areas—capital adequacy, management, and earnings; however, the results are different for asset quality. The sample included five banks from each stream of banking (2009–2013). Overall findings indicate either better performance or equal to conventional banking for the Bangladesh IBSI lead.

There are a few citations available on performance measurement of Islamic banking in the Pakistani institutional setting. Ansari and Rehman (2011) documented better performance of Islamic banking than conventional banking in three areas: risk, liquidity, and cost-effectiveness, in the Pakistani IBSI. The sample included three banks from each stream of banking (2006–2009). Islamic banking depicts better credit risk management and solvency while comparatively lagging in profitability and liquidity (Hanif et al. 2012). The sample included 5 Islamic and 22 conventional banks (2005–2009). Islamic banking depicts superiority over conventional banking in profitability and liquidity for 2007–2009, as concluded by Usman and Khan (2012) after studying three banks from each stream of banking.

Islamic banking shows equality in profitability and better performance than conventional banking in three areas: risk, solvency, and efficiency for 2006–2010 (Latif et al. 2016). The sample comprises five banks from each stream. Qureshi and Abbas (2019) documented the superior performance of Islamic banking in two areas, namely operating performance and liquidity, for the period 2010–2017. The sample included 2 Islamic and 15 conventional banks. Ali et al. (2021) compared the performance of conventional and Islamic banking in Pakistan for 2007–2016 using financial ratio analysis and documented better performance by Islamic banking in two areas, namely asset quality and sensitivity to market risk, whereas conventional banks outperformed Islamic banks in terms of earnings. Although the evidence favours superior management by Islamic banks in the areas of solvency and risk, the findings are mixed. Comparative profitability remained a concern in earlier periods, which was improved later on (Qureshi and Abbas 2019; Latif et al. 2016).

From the MENA region, the results are as follows. Saleh and Zeitun (2007) reported increased profitability, efficiency, and credit expansion in Jordan (2000–2003), while Fayed (2013) found superior performance of conventional banking in Egypt (2008–2010), after studying liquidity, profitability, solvency, and credit risk. Sample size was three Islamic and six conventional banks. The GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) region is the leader in the provision of Islamic financial services, with more than 50% of the global Islamic Banking Services Industry (IBSI) assets (IFSBr 2022). Researchers have focused on measuring the performance of the GCC-IBSI, as depicted by the selected literature review. Samad (2004) concluded from Bahrain that Islamic banking is superior in credit risk management, while similar in liquidity and profitability, after studying a sample of 6 Islamic and 15 conventional banks (1991–2001). Somehow similar results were documented by AbuLoghod (2010) by comparing the performance of conventional and Islamic banking from 2000 to 2005 in the GCC region through financial ratio analysis and found no significant difference in profitability and internal growth rate, while the liquidity risk level is low in Islamic banking. Siraj and Pillai (2012) concluded that Islamic banking is more resilient to the financial crisis, as well as outperforms conventional banking in performance in the GCC region (2005–2010). In another study, Sillah and Harrathi (2015) compared the performance of 28 conventional and 20 Islamic banks from the GCC region by applying data envelopment analysis (2006–2012). The findings suggest no difference in efficiency based on constant return to scale; however, variable return to scale suggests that the conventional banks are more efficient than their Islamic counterparts during 2009 and 2010. Likewise, Khokhar et al. (2020) compared the performance of 21 Islamic and 42 conventional banks in the GCC region from 2010 to 2016 and found Islamic banking at par with conventional banking in all terms of efficiency at the industry level. However, BenSlimen et al. (2022) documented that Islamic banking is less cost-efficient than conventional banking after comparing efficiency using stochastic frontier analysis between conventional and Islamic banking in the GCC region from 2006 to 2015. For a longer study period of 2000–2018, it was found that conventional banks are more efficient in profitability in the GCC region (Jaara et al. 2021). The overall results of these studies in the GCC region led to equality in performance, if not better than in conventional industry.

The literature contains studies that compare conventional and Islamic banking’s performance in various markets. However, none of the studies has compared the performance of multiple IBSI markets in the GCC region. Given the more similarities than differences in the selected economies, the GCC region is suitable for documenting the comparative performance of six IBSI markets. This research aims to document the comparative financial performance of the IBSI within GCC economies in the areas of capital adequacy, asset quality, management performance, earnings, and liquidity.

3. Analytical Framework

The literature suggests the inclusion of specific Islamic finance objectives in addition to traditional measures (financial performance) in the performance evaluation of the IBSI. The specific objectives include broader macroeconomic objectives and social/ethical objectives. Macroeconomic objectives comprise financial stability and equitability in the distribution of wealth. Financial stability is expected to be achieved by linking financial and real sectors, while applications of profit and loss sharing (PLS) and access to finance are tools to achieve equitable wealth distribution (Chapra 2008). Hanif and Farooqi (2023) articulated the concept of performance evaluation for the IBSI by dividing it into three sections/levels.

- The primary level addresses the survival of Islamic banking by generating sufficient returns within Shari’ah constraints.

- The secondary level addresses broader economic objectives, including financial stability and equitable wealth distribution.

- Finally, the higher level contributes towards the social uplift of the marginal community groups by investing in social sectors.

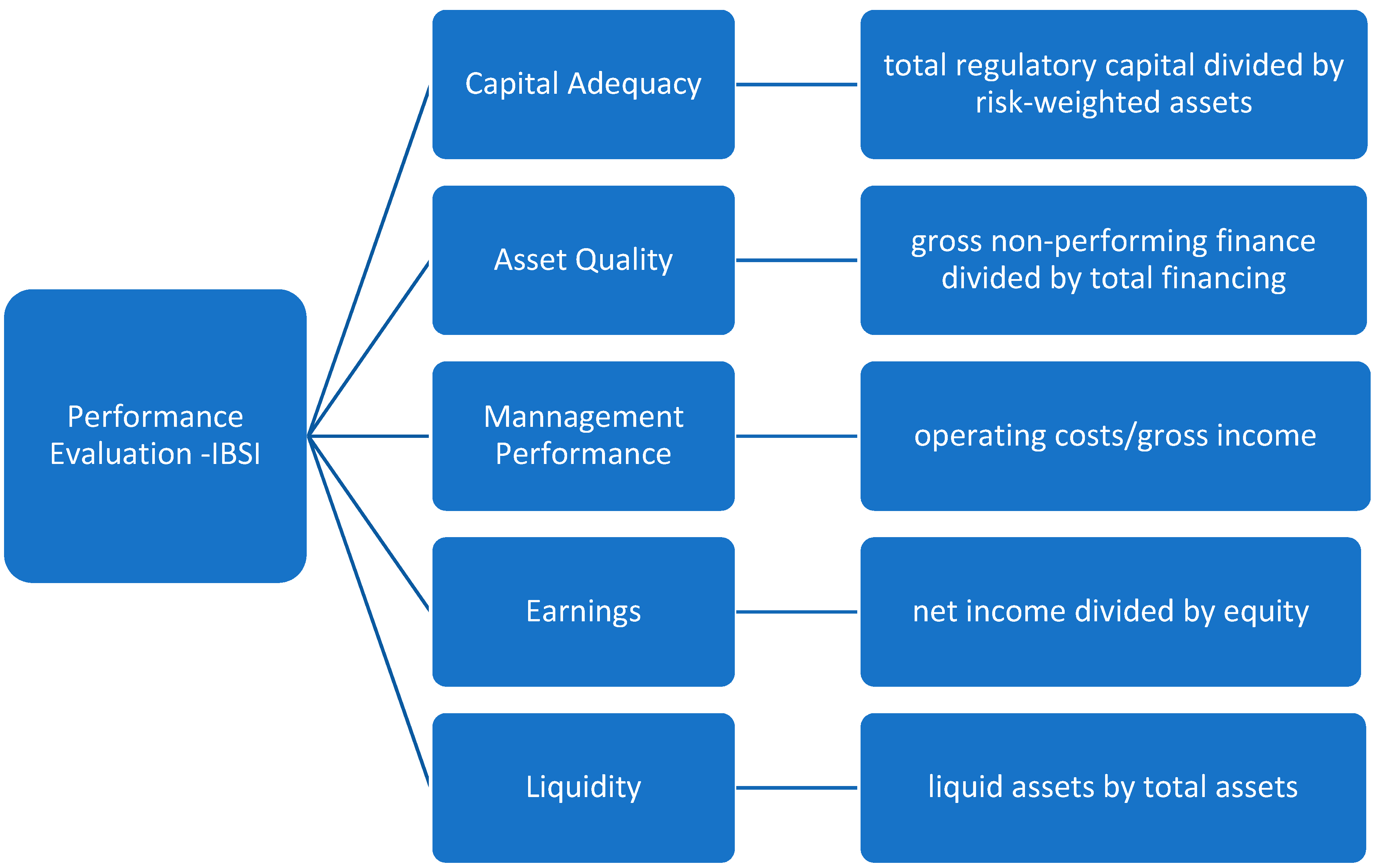

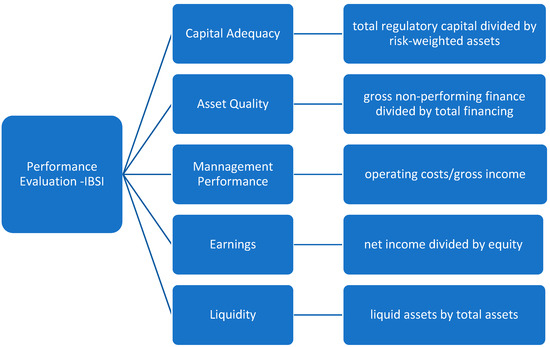

Micro objectives (primary level) for the IFSI include survival and profitability within Shari’ah constraints. Following the CAMEL framework, the commercial performance of the GCC-IBSI is measured in five areas (Rozzani and Rahman 2013; Ali et al. 2021) (Figure 1 presents an analytical framework).

Figure 1.

Financial performance evaluation framework—IBSI. Source: Constructed by the author.

- Capital—capital adequacy ratio (CAR), total regulatory capital/risk-weighted assets;

- Asset quality—non-performing finance (NPF), gross NPF/total financing;

- Management performance—cost-to-income ratio (CIR), operating costs/gross income;

- Earnings—return on equity (ROE), net income/equity; and

- Liquidity—liquid asset ratio (LAR), liquid assets/total assets.

Country-wise financial reporting data are obtained from the Islamic Financial Services Board, Prudential, and Structural Islamic Financial Indicators (PSIFIs) for Islamic banks (https://www.ifsb.org/data-metadata/). Analysis is carried out on quarterly data from 2013Q4 to 2021Q4. The duration is selected based on the availability of authentic country-wise data from the selected data source. However, the duration is recent and long enough to form an opinion on the performance of selected Islamic banking markets. Results based on objective classification of data are presented through tables and graphs. Graphs depicting trends in all CAMEL ratios are presented. The averages of all ratios are calculated with standard deviations and coefficients of variation. Tests for means equality among all markets based on a specific financial ratio are completed (Samad 2004; Islam and Ashrafuzzaman 2015).

Finally, a cause-and-effect relationship is determined through panel regression (Jaara et al. 2021). Return on equity (ROE) is used as a performance indicator (dependent variable), while capital adequacy, non-performing finance, the cost-to-income ratio, and the liquidity ratio are used as regressors. The following regression model is tested.

where ROE is the return on equity, CAR is the capital adequacy ratio, NPF is the non-performing finance, CIR is the cost-to-income ratio, LAR is the liquid asset ratio, C is a constant/intercept, ∈ represents the error term, the subscript i represents the markets, and the subscript t is for time.

Data are checked for stationarity and autocorrelation. Stationarity of the series is required to run the regression model. Likewise, no two independent highly correlated variables are recommended in the single regression model.

4. Analysis and Findings

Gulf Cooperation Council: The GCC consists of six Arabian Muslim countries (including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Oman) and is the Centre of Muslim civilisation with a dominant Muslim population. It was an earlier adopter, promotor, and leader in the modern Islamic financial system, with a significant share of the assets under management of the global Islamic Financial Services Industry.

The following facts depict how the GCC region has played a unique and active role in developing the modern IFSI.

- The first milestone in IFSI history was the establishment of the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) in Jeddah, KSA, in 1975. IsDB owners include 57 members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC); however, close to 45% of the shareholding is in the GCC region.

- The International Islamic Fiqh Academy (IIFA), established in 1981 in Jeddah, KSA, is a universal scholarly organization (a subsidiary organ of OIC) aimed at studying contemporary life issues and offering solutions through Ijtihad.

- The Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) was established in 1991 in Bahrain to develop and issue standards for the IFSI.

- The International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM) was established in 2002 in Bahrain, focusing on standardizing Shari’ah-compliant financial contracts and product confirmations.

- Dubai Islamic Bank is the oldest private-sector Islamic bank, established in 1975 in Dubai, UAE.

- JKAU: Islamic Economics (an international refereed journal), established in 1983 at King Abdulaziz University, KSA, is a pioneer outlet for disseminating IFSI-related academic literature.

- Dubai aims to be an Islamic finance hub (Kane 2014).

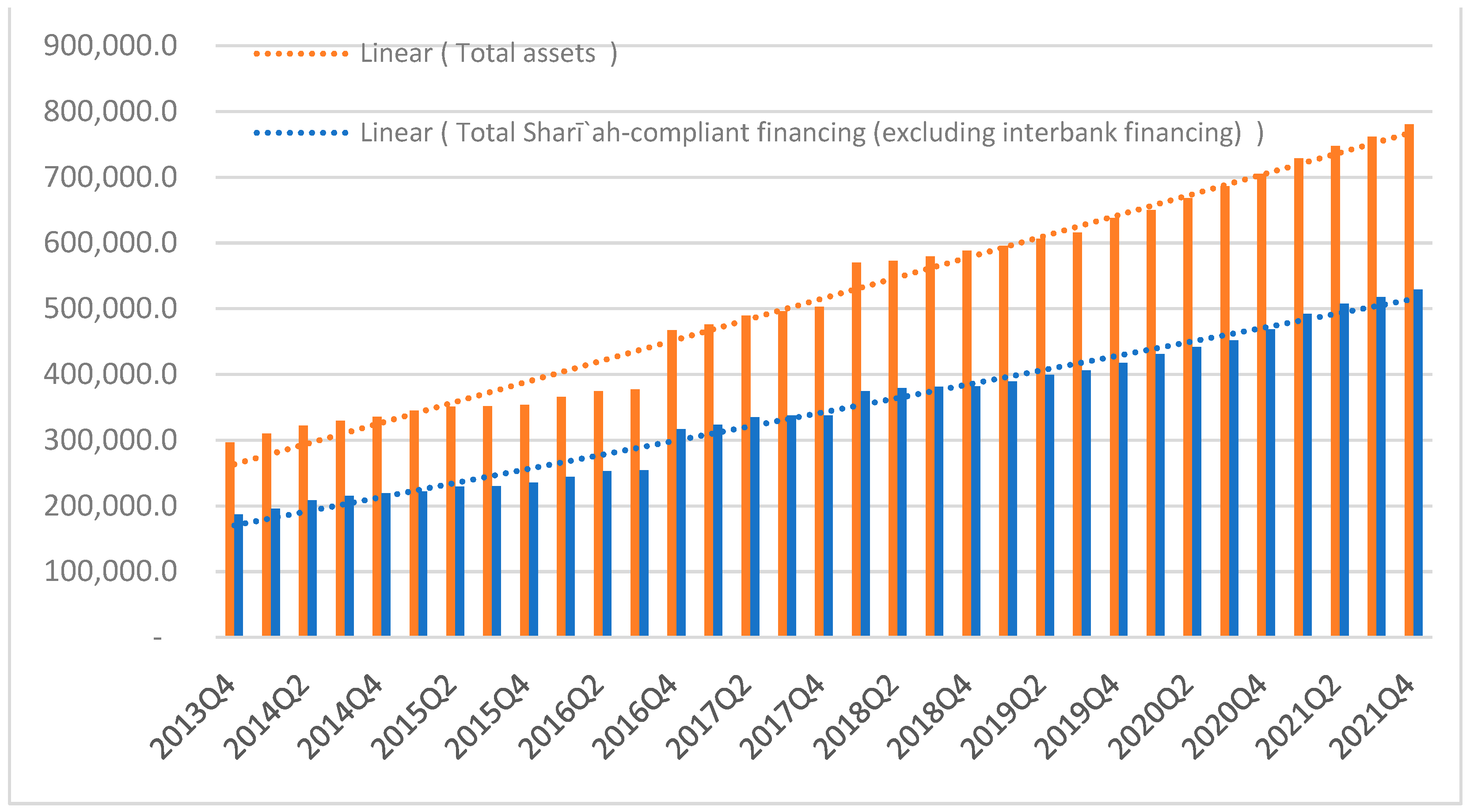

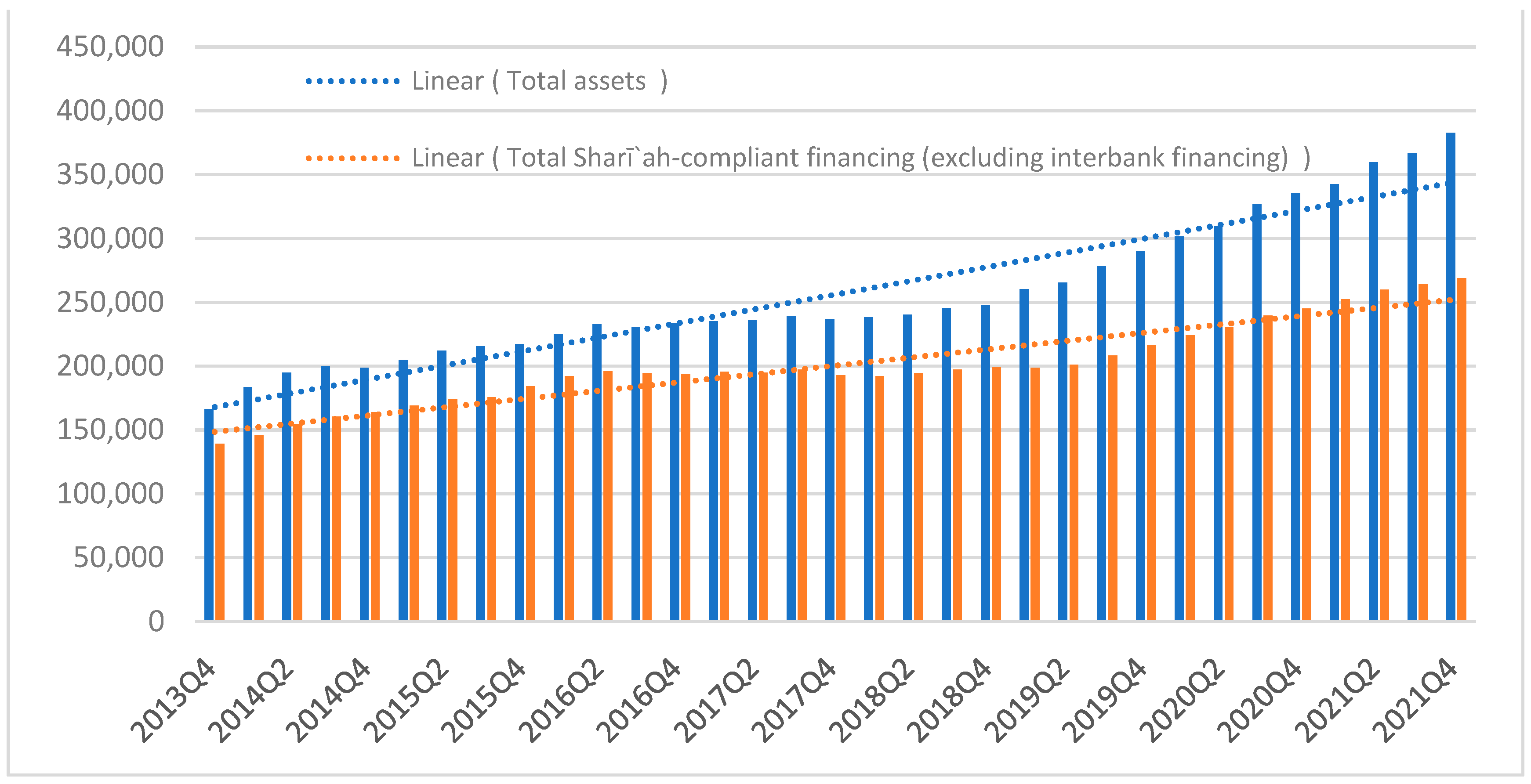

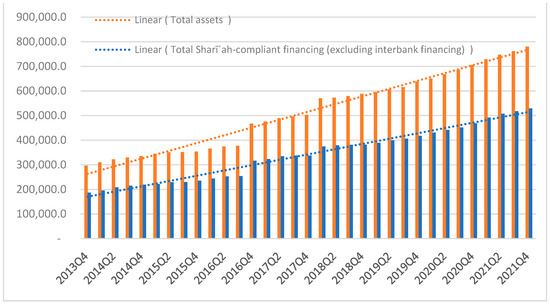

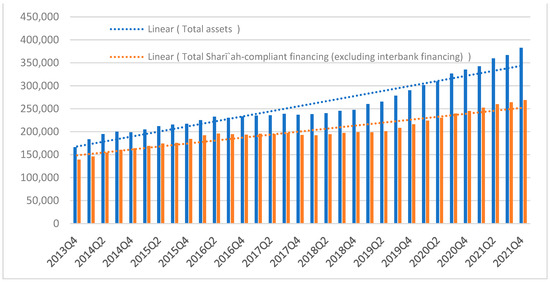

Assets under the management of the GCC–Islamic Banking Industry have reached a healthy volume of USD 1212.5 billion, representing more than 50% of global IBSI assets (IFSBr 2022). By the end of 2021Q4, the Islamic Banking Services Industry (IBSI) in the GCC consists of 42 fully fledged Islamic banking institutions (IBIs) with a branch network of 13131, employing 28,7752 professionals. Additionally, there are 12 Conventional Banks with Islamic Windows (CBIWs) with a branch network of 1175, employing 16,033 staff members (IFSB 2022). Figure 2 depicts growth trends in Total Assets (TA) and Total Shari’ah Compliant Financing (TSCF) for IBIs, while Figure 3 is for CBIWs (IFSB 2022). Quarterly growth of assets under IBIs (1%)3 is less than that under CBIW (1.5%) from 2018Q1 onward. Growth is higher for earlier quarters as the sample growth for IBIs (excluding Bahrain and Qatar) is 2%, and it is 2.64% for CBIW (2013Q4–2021Q4). At the end of the review period 2021Q4, 68% of total assets under IBIs represent TSCF and 11% investment in sukuk. In comparison, a higher percentage of asset concentration (70%) is represented by TSCF and 20% sukuk holding under CBIW. Trend lines show a higher concentration of TSCF compared with total assets (lesser gaps) in IBIs and CBIWs in initial quarters compared with final quarters (larger gaps) during the sample period.

Figure 2.

IBIs growth trends—assets and financing (USD million) for 33 quarters (2013Q4–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

Figure 3.

CBIWs growth trends—assets and financing (USD million) for 33 quarters (2013Q4–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

Market Share: The GCC region economies hold significant domestic banking market share. By 2021, based on domestic market share, all GCC Islamic banking markets have already achieved systemic importance. A country with a 15% market share in domestic banking assets is included in the list of systemic importance. Five GCC Islamic banking markets have achieved a 20% and above share in the domestic market, while two of them (Saudi Arabia and Kuwait) have more Islamic banking share than conventional banking. Likewise, the GCC Islamic banking markets make a significant contribution (above 50%) in global Islamic banking assets. The GCC region’s asset volume under Islamic banking management is above USD 1200 billion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Market Share of GCC Islamic Banking (2021).

Micro objectives for the IFSI include survival and being profitable within Shari’ah constraints. The commercial performance of the GCC-IBSI is measured in five areas, namely the capital adequacy ratio (CAR), total regulatory capital/risk-weighted assets; non-performing finance (NPF), gross NPF/total financing; the cost-to-income ratio (CIR), operating costs/gross income; return on equity (ROE), net income/equity; and the liquid asset ratio (LAR), liquid assets/total assets. Summary results are presented in Table 2. Based on the average results, under the CAR performance measure, the Oman IBSI is leading (29%), while the minimum is 16% (Oman CBIW); the NPF score is the highest for Bahrain (11%), while the minimum is less than 1% (Oman IBI and CBIW); Qatar leads in cost control (13%), while the highest CIR is 116% (Oman IBI); KSA leads in ROE (16%), while the least is −0.1% (Oman IBI); the liquid asset ratio is the highest for KSA IBI (28%), and the minimum is 13% (Oman CBIW). The results indicate that managerial attention to profitability and cost control is required in the Oman IBSI, while the matter of NPF is significant in the Bahrain IBSI.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics for 33 quarters (2013Q1–2021Q4).

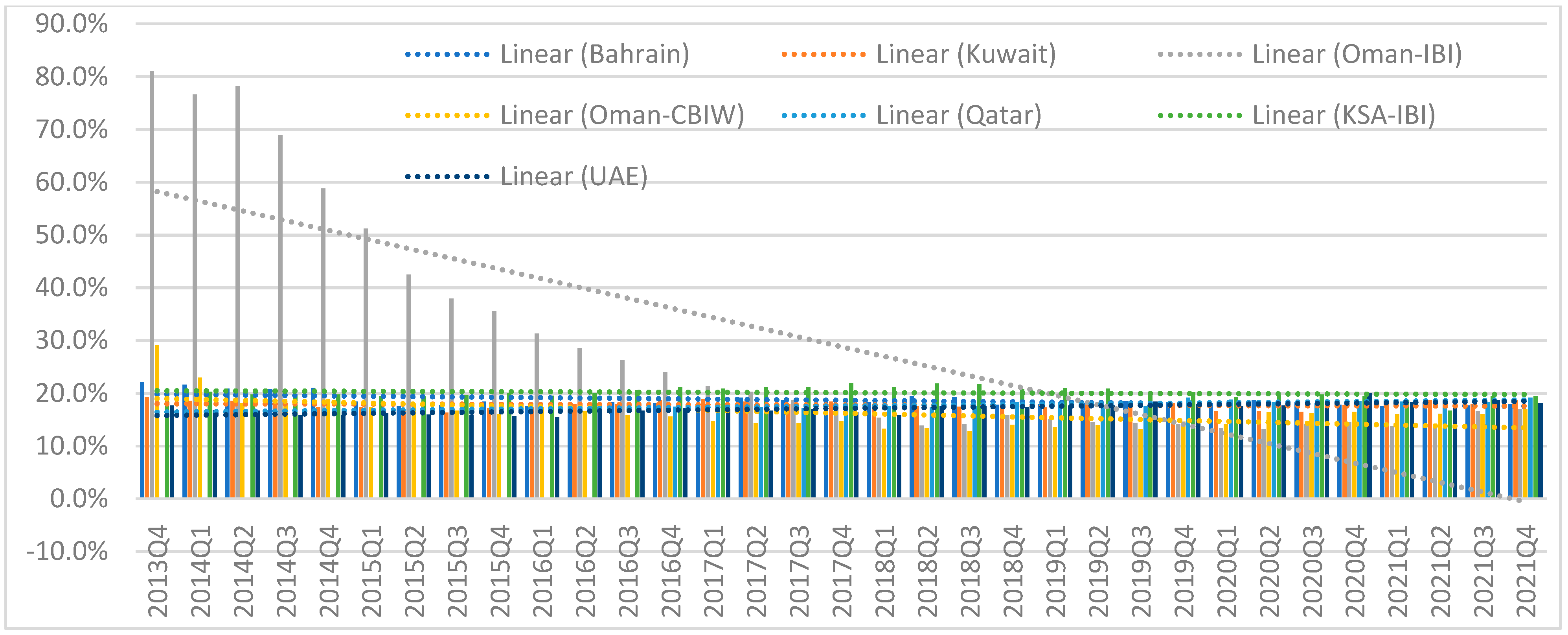

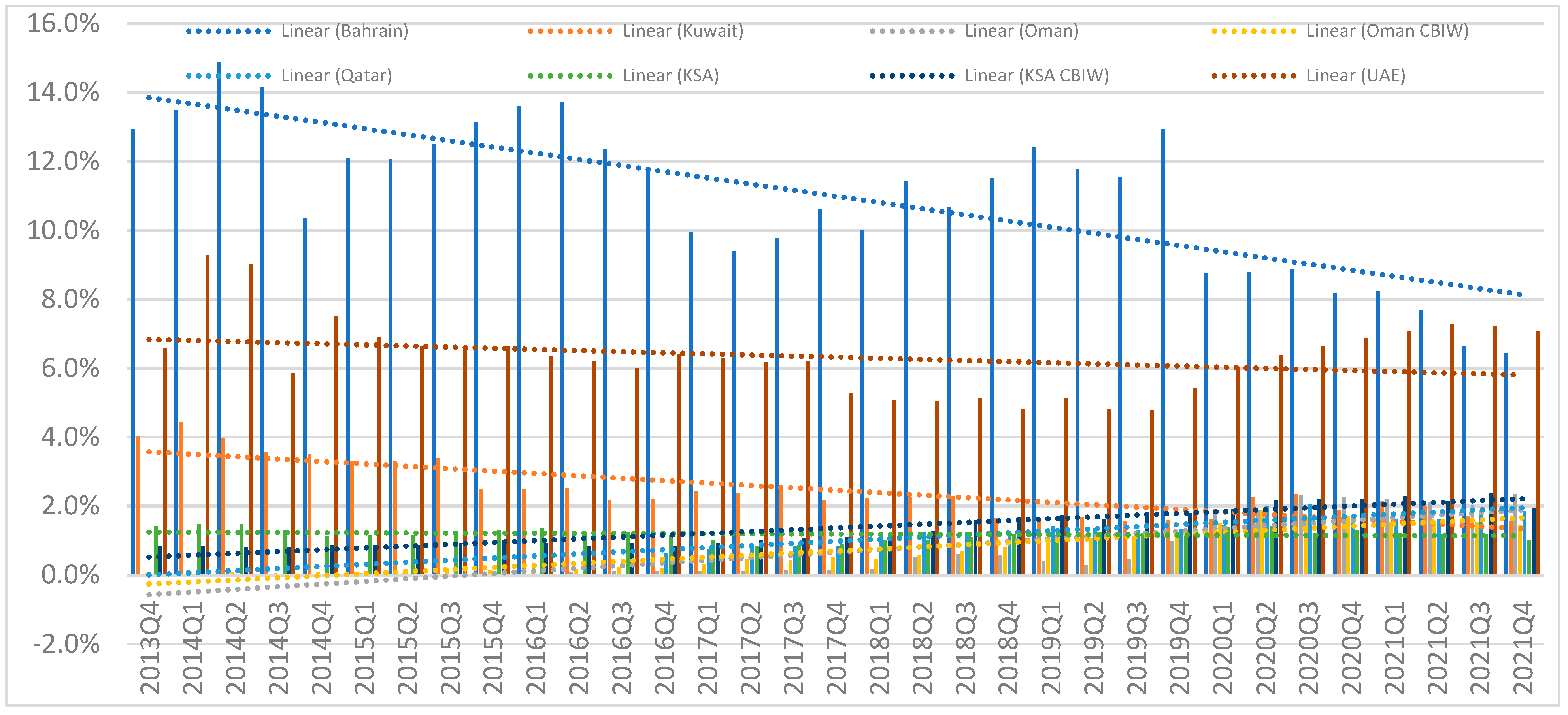

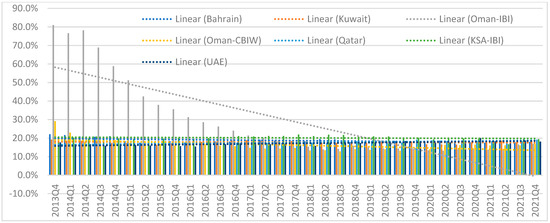

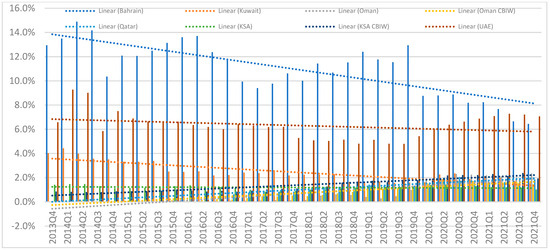

Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR): The CAR (measured as total regulatory capital/risk-weighted assets), is an essential financial ratio aimed at judging the sufficiency of capital by a bank required to pass the stress testing. Basel-3 specifies a minimum requirement of 8.0% (Basel 2019). Figure 4 and Table 2 depict comparative results for GCC countries. Much variation is witnessed in the case of the Oman IBSI, with an average CAR of 28.8% (standard deviation 21.22%) ranging from 13% to 81%, followed by the Oman CBIW with an average of 16.2% (standard deviation 3.10%). Trend lines show a downward slope (not much for CBIW), indicating declining trends. In all other cases, the average is well representative of the sample, as depicted by the standard deviation (ranging from 0.59% to 1.23%). The average car (standard deviation) for Bahrain is 18.7% (1.23%), Kuwait 17.80% (0.75%), Qatar 18.0% (0.59%), KSA 20.1% (1.03%), and UAE 17.1% (1.06%). Data for KSA CBIW are not reported in the selected database. The average CAR ranging from 16.2% to 28.8% (higher than the minimum Basel requirement of 8.0%) indicates the financial strength of the IBSI in the GCC region. The equality of means test indicates the differences in the average CAR among various GCC markets, as depicted by standard ANOVA (8.5) and Welch adjusted ANOVA (30.1) statistics with low probability values (close to 0.00) (Table 3).

Figure 4.

GCC-IBSI capital adequacy ratio (CAR) for 33 quarters (2013Q1–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

Table 3.

Test for Equality of Means Between Series.

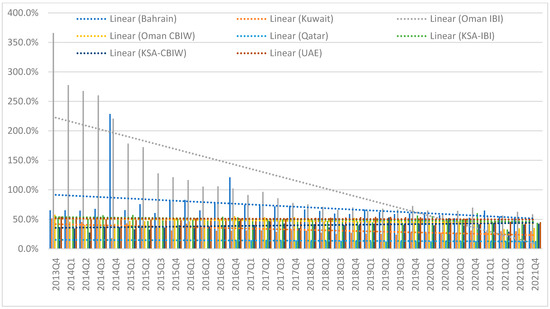

Non-performing Finance (NPF): Non-performing loans are measured as gross non-performing finance divided by total financing, which measures the credit risk and the company’s efficiency in collecting receivables. A lower NPF is an indication of low credit risk and vice versa. As per the results (Figure 5 and Table 2), improvement is depicted in reducing non-performing finance by three countries, namely Bahrain, UAE, and Kuwait. The highest average (11.0%) for the sample period is displayed by Bahrain, followed by UAE (6.3%) and Kuwait (2.5%). Notably, all these countries with higher average non-performing finance have shown significant improvement; for example, in the last quarter, 2021Q4, NPFs were 6.4% and 1.5% for Bahrain and Kuwait, respectively. Likewise, trend lines indicate a downward slope for Bahrain, Kuwait, and UAE. The average highest NPF for other countries is 1.4% (KSA CBIW), and the average lowest is 0.7% (Oman IBSI). As for the reliability of the average, as a representation of the sample data is concerned, the coefficient of variation (standard deviation/average) is calculated. The highest variation is documented for Oman (IBI 1.31, CBIW 0.88), followed by KSA (IBI 0.14, CBIW 0.40), Kuwait (0.32), Qatar (0.31), Bahrain (0.20), and UAE (0.17). Gross NPFs are below 2% in the last quarter for the sample except for Bahrain (6.4%), UAE (7.1%), and Oman (2.3%), which demands the attention of industry leaders. Also, Oman IBSI, KSA CBIW, and Qatar trend lines show a slightly upward movement. The equality of means test indicates the differences in average NPF among various GCC markets, as depicted by standard ANOVA (412) and Welch-adjusted ANOVA (240) statistics with low probability values (close to 0.00) (Table 3).

Figure 5.

GCC-IBSI non-performing finance (NPF) ratio for 33 quarters (2013Q1–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

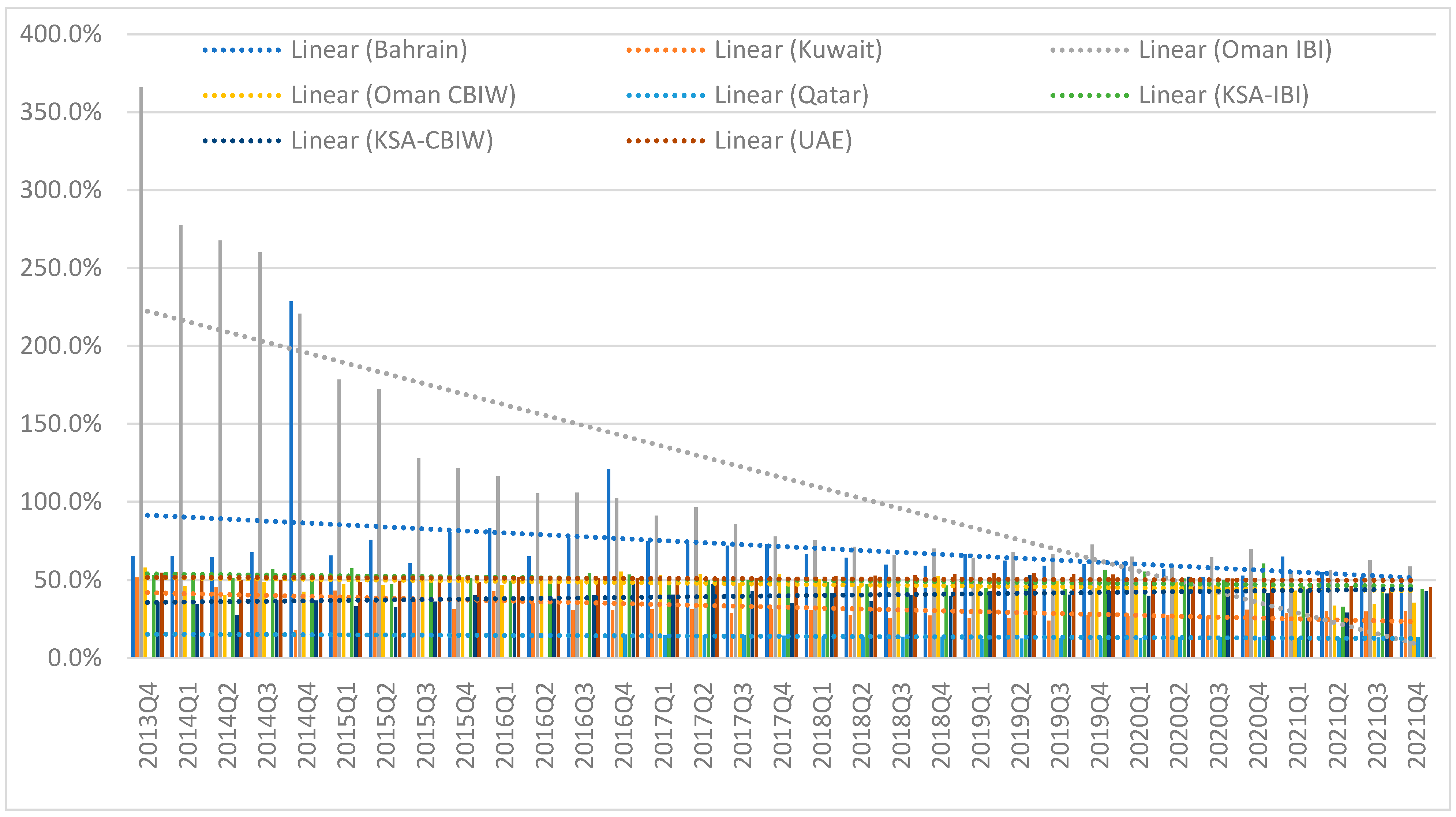

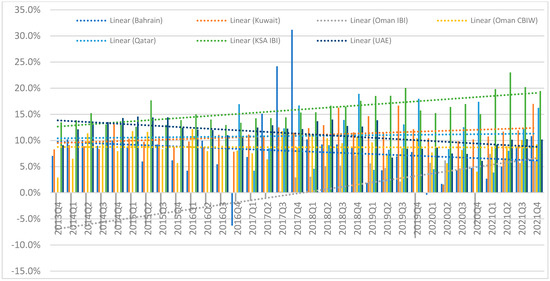

Cost-to-Income Ratio (CIR): The cost-to-income ratio (CIR) is calculated as operating costs/gross income, aimed at measuring the operating efficiency. A low CIR positively contributes to the generation of healthy ROE and efficient operation of the organization. Comparative results for the GCC-IBSI during the review period are reported in Figure 6 and Table 2. The average CIR is the highest for Oman IBI (115.7%), followed by Bahrain (71.4%) and UAE (50.7%). Notably, trend lines are downward for both countries (Oman and Bahrain), indicating improvement. All other CIRs are below 50.0%, ranging from 49.9% (KSA IBI), 47.3% (Oman CBIW), 39.8% (KSA CBIW), 32.5% (Kuwait—downward trend), to 13.3% (Qatar). CIR trend lines indicate Bahrain downward, Kuwait slightly downward, and Oman IBI significantly downward, while almost straight for Oman CBIW, Qatar, KSA IBI, KSA CBIW, and UAE. The highest coefficient of variation is documented for Oman IBI (0.68), followed by Bahrain (0.43), Kuwait (0.26), KSA CBIW (0.14), Oman CBIW (0.12), KSA IBI (0.10), Qatar (0.06), and UAE (0.05). CV results indicate a good representation of the average of the sample period. While the Qatar IBSI has depicted outstanding performance in cost control, the Oman (IBI) and Bahrain IBSIs need significant attention from decision-makers in cost control. It is encouraging to note that for both Oman and Bahrain, trend lines are downward, indicating that improvement is in progress (e.g., as of 2021Q4, the CIR is 58.5% for Oman IBI and 51.6% for Bahrain). The equality of means test indicates the differences in the average CIR among various GCC markets, as depicted by standard ANOVA (28.55) and Welch adjusted ANOVA (1347) statistics with low probability values (close to 0.00) (Table 3).

Figure 6.

GCC-IBSI cost-to-income ratio (CIR) for 33 quarters (2013Q1–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

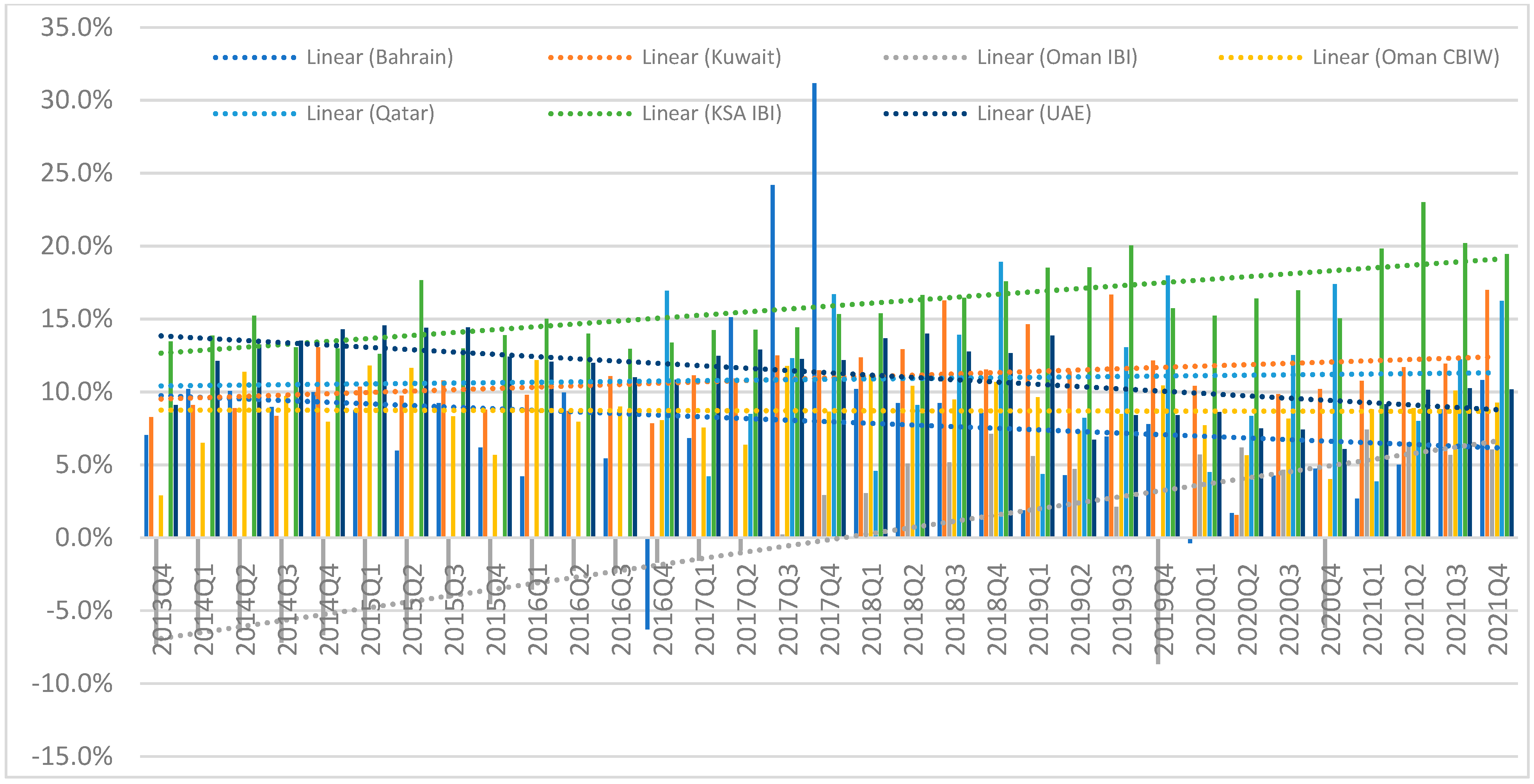

Return on Equity (ROE): Return on equity is calculated as net income divided by equity, a significant measure of profitability and net returns as a percentage of capital that the business generates for owners. Results for the GCC-IBSI in ROE are presented in Figure 7 and Table 2. Data for KSA CBIW are not reported, while data for Qatar 2016Q4 onward are reported. The average return on equity is the highest for KSA (15.9%), followed by UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait (11.3%, 11.0%, and 11.0%, respectively). The Oman CBIW depicted an average ROE of 8.7%, while Bahrain had 8.0%; the lowest average ROE remained for the Oman IBSI (−0.1%). The coefficient of variations is under 0.5, except for Bahrain at 0.81 and Oman’s IBI at 39.34. Trend lines for Bahrain, UAE, and Oman CBIW are downward; those for KSA and Kuwait are upward; that of the Oman IBI is negative to positive; and that of Qatar is almost straight. The GCC-IBSI has performed well regarding survival goals by depicting positive ROE, except the Oman IBSI, although it has shown progress in recent quarters. Four of the six markets have shown an average ROE in double digits despite the COVID-19 crisis. All ROEs are positive as of 2021Q4, ranging from 6.0% to 19.4%. The KSA IBSI has proven to be a high achiever, while the Oman IBSI needs to improve profitability to remain competitive in the long term. The equality of means test indicates the differences in the average ROE among various GCC markets, as depicted by standard ANOVA (46.01) and Welch adjusted ANOVA (48.09) statistics with low probability values (close to 0.00) (Table 3).

Figure 7.

GCC-IBSI return on equity (ROE) for 33 quarters (2013Q1–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

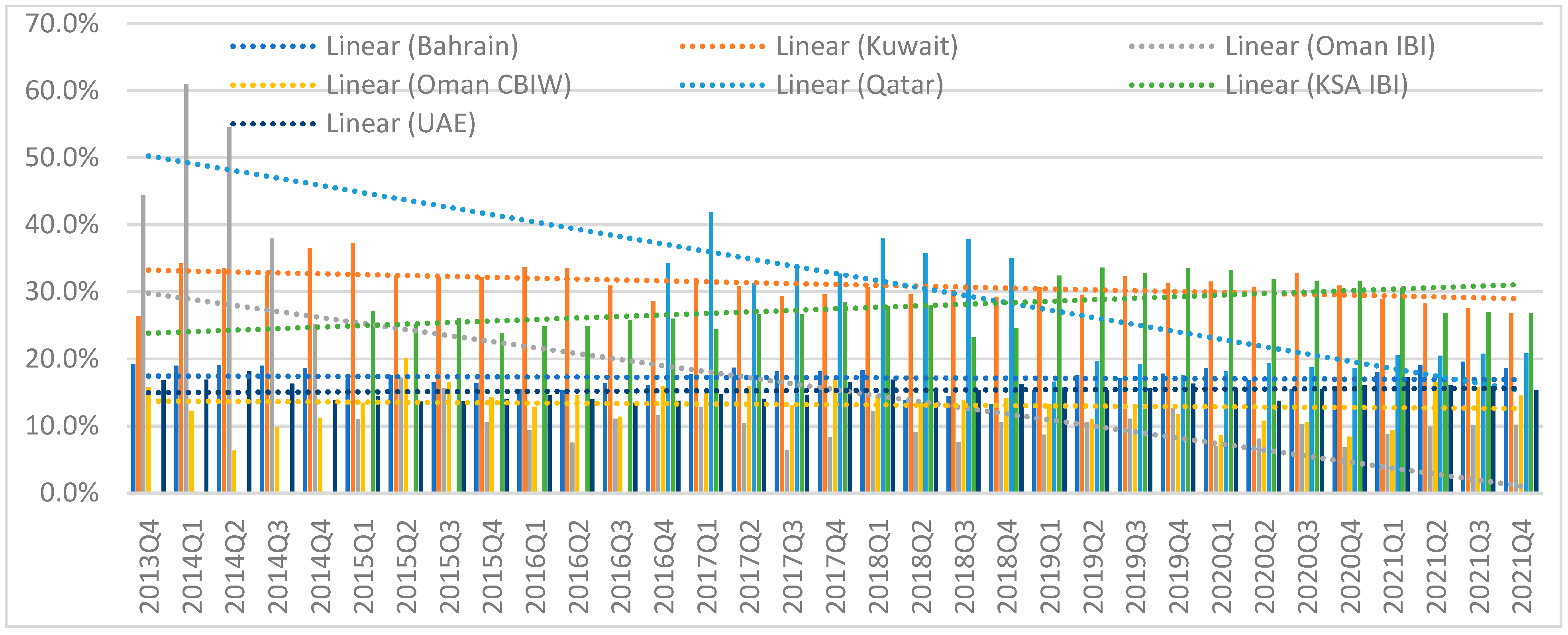

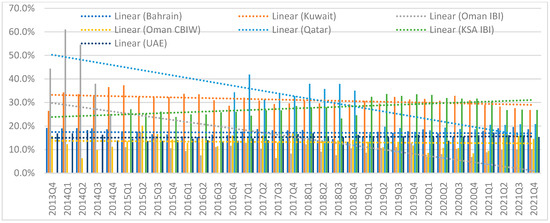

Liquid Asset Ratio (LAR): The liquid asset ratio is calculated by dividing liquid assets by total assets, aimed at measuring the ability of a banking institution to meet its obligations as and when due. Results on the liquidity position of the GCC-IBSI for the sample period (2013Q4 to 2021Q4) are presented in Figure 8 and Table 2. In the case of KSA CBIWs, no data are available, and IBI data are from 2015Q1 onward, while the Qatar data are from 2016Q4 onward. Trend lines indicate a significant decrease for the Qatar and Oman IBIs while a slight decrease for the Kuwait and Oman CBIWs. In the case of Bahrain and UAE, trend lines are almost straight, while the trend line is upward for the KSA IBIs. Kuwait leads in the average LAR (31.1%), followed by KSA (28.0%), Qatar (26.2%), Bahrain (17.2%), the Oman IBIs (15.4%), UAE (15.3%), and the Oman CBIWs (13.2%). Closing figures (2021Q4) for Qatar, Oman IBIs, Oman CBIWs, and Kuwait are 20.8%, 10.2%, 14.5%, and 26.8%, respectively. Liquidity maintenance needs attention in the Oman IBIs. The highest variation is depicted by CV for the Oman IBIs (0.89), Qatar (0.33), the Oman CBIWs (0.22), the KSA IBIs (0.12), Bahrain (0.10), UAE, and Kuwait (0.08), respectively. The average represents the sample well, except for Oman and Qatar. The equality of means test indicates the differences in the average LAR among various GCC markets, as depicted by standard ANOVA (42.64) and Welch adjusted ANOVA (249.4) statistics with low probability values (close to 0.00) (Table 3).

Figure 8.

GCC-IBSI liquid asset ratio (LAR) for 33 quarters (2013Q1–2021Q4). Source: Constructed by the author; data (IFSB 2022).

The second phase of analysis consists of determining cause and effect through regression. Which of the internal variables are significant contributors to the financial performance (measured as ROE) of the Islamic banking industry in the GCC region? Certain pre-tests on data are required to run the regression model, including correlation among independent variables and checking for unit roots.

Correlations: The results of the correlations are presented in Table 4. Accordingly, the CAR and the CIR (both independent variables) are highly correlated (81%) and cannot be used in a single regression model. Hence, we have to delete one of them for any regression estimation. In the case of the dependent variable (ROE), two variables (CAR and CIR) depict a negative relationship, while others (NPF and LAR) show a positive relationship. These results indicate that there exist relationships between independent and dependent variables to be confirmed by formal testing through regression equations.

Table 4.

Correlation GCC Markets (CAMEL Ratios 2013Q4 to 2021Q4).

Stationarity Test: Testing for the unit root is an essential requirement of a regression model. The results are presented in Table 5. Accordingly, all series are stationary at level, except for non-performing finance. NPF is stationary at the first difference; hence, we created D-NPF. Comparative results using ADF and PP unit root tests are calculated. Results are similar under both types of tests.

Table 5.

Stationarity Tests.

Regression Analysis: Given the high correlation between CAR and CIR, the research estimates two equations by eliminating one variable in each model. Also, due to the higher order of integration, a differenced series (D-NPF) is used in the estimation of regression equations for the NPF series. Furthermore, we rely on the Hausman test to choose between random and fixed effects for panel data regression (Table 6). Results of Hausman tests support the choice of random effect (based on probability values) for both regression equations. The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 7. Some interesting results emerged through regression estimates. Under both regression models, the adjusted R square is low; likewise, the significant constant (might) indicates that some variables other than the selected explain variations in the ROE. Both the CAR and the CIR carry significant negative coefficients, confirming the hypothesis that higher costs and higher equity contribute to a reduction in the ROE. Surprisingly, non-performance finance is insignificant but has a positive relationship. In model 1, the coefficient is larger (0.47). Finally, liquidity positively contributes to the ROE but is significant under Model 1.

Table 6.

Hausman Test—Cross-Section Random Effects.

Table 7.

Regression Analysis.

Variance Decomposition: Finally, we decomposed the variance, and the results are presented in Table 8. According to the results, much of the variation in the ROE is internal. Variations of around 4% in period 1 and around 17% in period 10 are explained by other selected variables, with liquidity accounting for a major share, followed by cost to income variable.

Table 8.

Variance Decomposition of ROE.

5. Concluding Remarks

This study documents the commercial performance (which is the primary objective and essential for the survival) of the IBSI in the leading markets of the GCC region using quarterly published financial data for 2013Q4–21Q4. The findings show an overall encouraging picture of the industry based on achievements in the areas of capital adequacy, asset quality, management capabilities, earnings, and liquidity during the review period. The average LAR is above 13%, and the average CAR is above 16%, indicating the solvency of the IBSI in the GCC region. The KSA IBSI leads in the ROE, followed by UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait, respectively. Also, Qatar leads in cost control, followed by Kuwait and KSA; however, the CIR is higher for Oman and Bahrain. The average non-performing loans ratio is higher for Bahrain and UAE. Equality of means tests suggest that averages of the CAR, NPF, CIR, ROE, and LAR in selected markets are not similar. Regression results show that cost control and liquidity management significantly contribute to equity returns. The decomposition of variance suggests that much of the variations in the ROE are internal, and other selected factors cause a small variation.

Managerial implications include focusing on cost reduction, non-performing loans, and prudent liquidity management by respective managers in multiple GCC markets. A special managerial focus on the ROE is needed in the Oman IBSI, while due attention to non-performing loans is needed in Bahrain and UAE markets. None of the GCC markets is offering 100% Islamic banking. Shares of Islamic banking as a percentage of domestic banking assets are as follows: Saudi Arabia (77%), Kuwait (52%), Qatar (28%), UAE (24%), Bahrain (21%), and Oman (15%) (IFSBr 2022). There are opportunities to expand and reach millions of unserved/underserved residents. The GCC Islamic banking industry offers promising returns with financial strength for investors interested in halal earnings. Given the similarity of the IFSI’s objectives with SDGs, the Islamic financial system is expected to positively contribute to achieving SDGs.

This study’s limitations include the consideration of external factors (macroeconomic) as determinants of financial performance in the GCC-IBSI. Also, the contribution of oil revenues to the expansion and growth of the IBSI in the region is an exciting research topic. The future research agenda includes examinations in these areas.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by Ajman University.

Data Availability Statement

Public Source IFSB.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Data for domestic branches not available for Bahrain. |

| 2 | Data for staff are not available for Kuwait and Bahrain. |

| 3 | Data for Qatar and Bahrain 2016Q4 and 2018Q1 onward, respectively. |

References

- Abdulrahman, Yahia. 2010. The Art of Islamic Banking and Finance: Tools and Techniques for Community-Based Banking, 1st ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrehman, Asyraf H. J. 2000. The Concept Of Social Justice as Found in Sayyid Qutb’s Fi Ziljl Al-Qur’an. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- AbuLoghod, Hadeel S. 2010. Do Islamic Banks Perform Better Than Conventional Banks? Evidence from Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.arab-api.org/APIPublicationDetailsEn.aspx?PublicationID=297 (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Ahmad, Abu Umar Farooq, and Mohammad Kabir Hassan. 2007. Regulation and Performance of Islamic Banking in Bangladesh. Thunderbird International Business Review 49: 251–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Asif, Malik Faheem Bashir, and Muhammad Asim Afridi. 2021. Do Islamic Banks Perform Better than Conventional Banks? Turkish Journal of Islamic Economics 8: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Sanaullah, and Atiqa Rehman. 2011. Financial Performance of Islamic and Conventional Banks in Pakistan: A Comparative Study. Paper presented at 8th International Conference on Islamic Economics and Finance, Center for Islamic Economics and Finance, Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies, Qatar Foundation, Doha, Qatar, March 15. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, Muhammad Adeel, and Ahcene Lahsasna. 2017. Proposal for a new Sharīʿah risk rating approach for Islamic banks. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance 9: 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asutay, Mehmet. 2012. Conceptualising and Locating the Social Failure of Islamic Finance: Aspirations of Islamic Moral Economy vs the Realities of Islamic Finance. Asian and African Area Studies 11: 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ayub, Muhammad. 2018. Islamic finance crossing the 40-years milestone—The way forward. Intellectual Discourse 26: 463–84. [Google Scholar]

- Basel. 2019. Minimum Capital Requirements for Market Risk. Basel: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, ISBN 978-92-9259-237-0 (online). [Google Scholar]

- BenSlimen, Rehab, Fethi Belhaj, Manel Hadriche, and Mohamed Ghroubi. 2022. Banking efficiency: A comparative study between islamic and conventional banks in gcc countries. Copernican Journal of Finance & Accounting 11: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapra, M. Umar. 2008. Innovation and authenticity in Islamic finance. In Eighth Harvard University Forum on Islamic Finance on Innovation and Authenticity [April 19–20]. Cambridge: Harvard Law School. [Google Scholar]

- Fayed, Mona Esam. 2013. Comparative Performance Study of Conventional and Islamic Banking in Egypt. Journal of Applied Finance & Banking 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, Muhammad. 2018. Sharīʿah-compliance ratings of the Islamic financial services industry: A quantitative approach. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance 10: 162–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, Muhammad, and Kiran Zafar. 2020. Developments in Islamic Finance Literature: Evidence from Specialised Journals. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics 33: 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, Muhammad, and Muhammad Nauman Farooqi. 2023. Objective Performance Evaluation of the Islamic Banking Services Industry: Evidence from Pakistan. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance 15: 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, Muhammad, Mahvish Tahir, Arshia Tariq, and Wajeeh-ul-Momeneen. 2012. Comparative Performance Study of Conventional and Islamic Banking in Pakistan. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics 83: 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hazman, Samsudin, Nawawi Mod Nasir, Zairihan Abd Haleem, and Md Said Ahmad Syahmi. 2018. Financial Performance Evaluation of Islamic Banking System: A Comparative Study among Malaysia’s Banks. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia 52: 137–47. [Google Scholar]

- IFSB. 2022. Prudential and Structural Islamic Financial Indicators. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Financial Services Board. Available online: https://www.ifsb.org/data-metadata/ (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- IFSBr. 2022. Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Financial Services Board. [Google Scholar]

- IFSBr. 2023. Islamic Financial Services Stability Report. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Financial Services Board. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, Md Tanim ul, and Mohammad Ashrafuzzaman. 2015. A Comparative Study of Islamic and Conventional Banking in Bangladesh: Camel Analysis. Journal of Business and Technology (Dhaka) 10: 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaara, Bassam Omar Ali, Mohammad A. AL-Dahiyat, and Ismail AL-Takryty. 2021. The Determinants of Islamic and Conventional Banks Profitability in the GCC Region. International Journal of Financial Research 12: 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, Badrul Hisham, Mohammad Samaun Safa, and Rohani Moh. 2008. Assessing Production Efficiency of Islamic Banks and Conventional Bank Islamic Windows in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management Research 1: 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, Frank. 2014. Business. The National News. December 30. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/dubai-closer-to-becoming-islamic-finance-hub-1.637000 (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Khokhar, Imran, Mahboob ul Hassan, Muhammad Nauman Khan, and Md Fouad BinAmin. 2020. Investigating the Efficiency of GCC Banking Sector: An Empirical Comparison of Islamic and Conventional Banks. International Journal of Financial Research 11: 220–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Youssef, Ali Abbas, Muhammad Nadeem Akram, Shahid Manzoor, and Saeed Ahmad. 2016. Study of performance comparison between Islamic and conventional banking in Pakistan. European Journal of Educational and Development Psychology 4: 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Maudoodi, Syed Abul Aala. 1941. The Economic Problem of Man and its Islamic Solution [Speech at Muslim University Aligarh (20th October)], 3rd ed. Delhi: Markazi Maktaba Jamaat e Islami Hind. [Google Scholar]

- Mergaliyev, Arman, Mehmet Asutay, Alija Avdukic, and Yusuf Karbhari. 2021. Higher Ethical Objective (Maqasid al-Shari’ah) Augmented Framework for Islamic Banks: Assessing Ethical Performance and Exploring Its Determinants. Journal of Business Ethics 170: 797–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Mustafa Omar, Dzuljastri Abdul Razak, and Fauziah Md Taib. 2008. The Performance Measures of Islamic Banking Based on the Maqasid Framework. Paper presented at IIUM International Accounting Conference (INTAC IV), Putra Jaya Marroitt, Putrajaya, Malaysia, June 25; Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e636/a73ae59a7a2192c51994a3acfa636032b076.pdf?_ga=2.162074431.2085464327.1593956161-2068857030.1593956161 (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Mohammed, Mustafa Omar, Kazi Md Tarique, and Rafikul Islam. 2015. Measuring the performance of Islamic banks using maqāṣid-based model. Special issue, Intellectual Discourse 23: 401–24. [Google Scholar]

- Obaidullah, Mohammed. 2005. Rating of Islamic Financial Institutions: Some Methodological Suggestions. Jeddah: Scientific Publishing Centre, King Abdulaziz University. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, Muhammad Hussain, and Kausar Abbas. 2019. Performance analysis of Islamic and traditional banks of Pakistan. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting 27: 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rasli, Salina, Nor Hazwani Binti Hassan, Salbiah Hanum Mohd Hajali, Jamilah Kamis, and Norhasbi Abdul Samad. 2020. CAMEL Characteristics, Financial Performance and Stability of Selected Islamic Banking in Malaysia. Special issue, Selangor Science &Technology Revie 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rosly, Saiful Azhar, and Mohd Afandi Abu Bakar. 2003. Performance of Islamic and mainstream banks in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Economics 30: 1249–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzani, Nabilah, and Rashidah Abdul Rahman. 2013. Camels and Performance Evaluation of Banks in Malaysia: Conventional Versus Islamic. Journal of Islamic Finance and Business Research 2: 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Saged, Ali Ali Gobaili, Thabet Ahmad Abu Ahlaj, and Mohd Yakub Zulkifli Bi. 2017. The role of the Maqasid al-Sharīʿah in preserving the environment. Humanomics 33: 125–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairally, Salma. 2007. Evaluating the ‘Social Responsibility’ of Islamic Finance: Learning From the Experiences of Socially Responsible Investment Funds. In Advances in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edited by Iqbal Munawar. Jeddah: Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Development Bank Group, vol. 1, pp. 279–320. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, Ali Salman, and Rami Zeitun. 2007. Islamic Banks in Jordan: Performance and Efficiency Analysis. Review of Islamic Economics 11: 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, Abdus. 2004. Performance of Interest-free Islamic Banks vis-a-vis Interest-based Conventional Banks of Bahrain. IIUM Journal of Economics and Management 12: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sillah, Bukhari M. S., and Nizar Harrathi. 2015. Bank Efficiency Analysis: Islamic Banks versus Conventional Banks in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries 2006–2012. International Journal of Financial Research 6: 143–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, K. K., and P. Sudarsanan Pillai. 2012. Comparative Study on Performance of Islamic Banks and Conventional Banks in GCC region. Journal of Applied Finance & Banking 2: 123–61. [Google Scholar]

- Smolo, Edib, and Abbas Mirakhor. 2010. The global financial crisis and its implications for the Islamic financial industry. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 3: 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, Abid, and Muhammad Kashif Khan. 2012. Evaluating the Financial Performance of Islamic and Conventional Banks of Pakistan: A Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Business and Social Science 3: 253–57. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).