Personal Networks, Board Structures and Corporate Fraud in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data

2.1. Fraud Data

2.2. Personal Network Indicators

2.3. Corporate Governance Indicators

3. Empirical Models

3.1. Quantification of Personal Networks

3.2. Empirical Model for Fraud Occurrence

3.3. Empirical Model of Fraud Detection

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Fraud Occurrence

4.2. Fraud Detection

4.3. Implications and Contributions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Enron Corporation, a U.S. energy company, was found to have concealed a large amount of off-the-book debts. The company’s management was involved in this fraud, which led to the enactment of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (officially named the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002) in the United States. |

| 2 | The Toshiba Corporation was found to have falsified its sales and net income for the fiscal years 2008 to 2014. |

| 3 | The accumulation of empirical analyses on the detection of corporate fraud is also required from the viewpoint of the problem of partial observability inherent in fraud data. Since only detected cases are recorded in fraud statistics, estimation biases occur due to missing data of undetected (but occurred) events. The problem of partial observability was pointed out by Poirier (1980). Research on fraud considering the partial observability problem is gradually accumulating (Wang et al. 2010; Wang 2013; Khanna et al. 2015). |

| 4 | Onji et al. (2019) examined the effects of the capital injection policy on the corporate governance of Japanese banks in the late 1990s and early 2000s, focusing on changes in the personal networks of board members. However, they did not analyze the effects of personal networks on corporate behavior. |

| 5 | As Chetty et al. (2022) point out in Nature, “Social capital—the strength of an individual’s social network and community—has been identified as a potential determinant of outcomes ranging from education to health. However, efforts to understand what types of social capital matter for these outcomes have been hindered by a lack of social network data.” |

| 6 | Not only in Japan but also in many countries, a strong correlation between graduating from a selective college and success in the labor market has been robustly observed (see Kawaguchi and Ma 2008). |

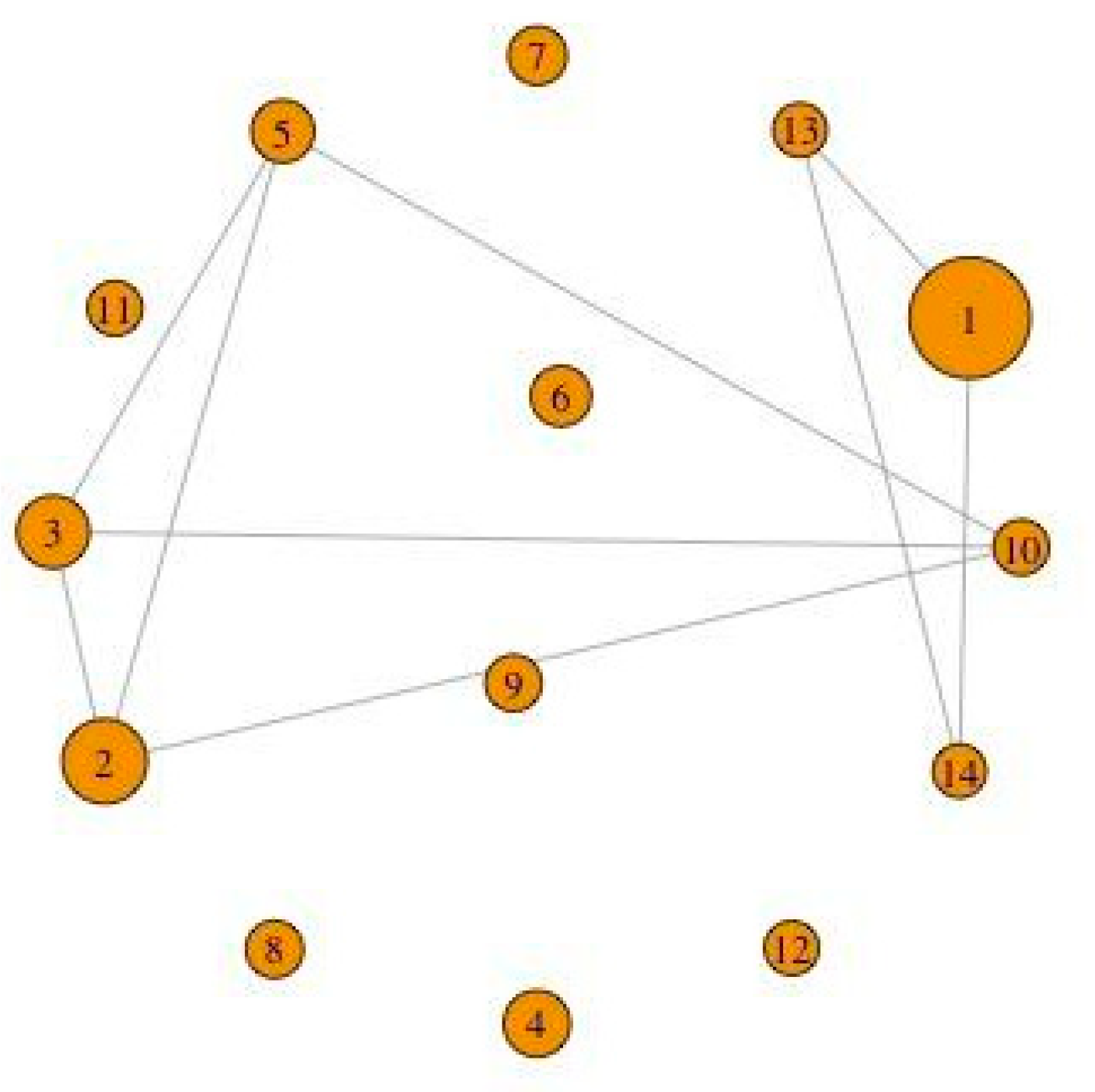

| 7 | The Audit and supervisory committee (監査監督委員会設置会社: kansa kantoku iinkai secchi geisha) must have at least three members who are directors of the company, half of whom must be outside directors. In other words, there must be at least two outside directors. Appointment of the members of the audit and supervisory committee shall be made by an ordinary resolution of a shareholders’ meeting and the agenda must be separate from those appointing other directors. Submitting the agenda regarding the appointment of the members of the audit and supervisory committee to the shareholders’ meeting requires prior consent of the audit and supervisory committee. The audit and supervisory committee has the authority to propose agenda-appointing directors who are the members of the audit and supervisory committee. The remuneration of the members of the audit and supervisory committee shall be prescribed in the articles of association or approved by the shareholders’ meeting. (Sekiguchi n.d.). |

| 8 | “Company with Nominating Committee, etc. (指名委員会等設置会社: shimei iinnkai tou secchigaisha)” has changed its name twice in the past. When this form was first introduced in 2003, its name was “Company with Committees, etc. (委員会等設置会社: iinnkai tou secchigaisha),” then it was changed to “Company with Committees (委員会設置会社: iinkai secchigaisha)” in 2005, and since 2015 it has been named “Company with Nominating Committee, etc.” |

| 9 | As described by Shibuya (2016), the second form “Companies with a Nominating Committee, etc.,” which strictly separates supervision and business execution, did not spread among Japanese companies due to its requirement for many outside directors. To accelerate the governance form change in Japanese companies, the “Company with Audit and Supervisory Committee” was introduced as the third option. The degree of separation between supervision and business execution is considered to be highest in the “Company with a Nominating Committee, etc.,” followed by the “Company with Audit and Supervisory Committee,” and then the “Company with Board of Auditors”. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | Higuchi (2012) defined corporate fraud as “a business incident or accident that may cause a serious disadvantage to an organization and satisfies the following three requirements: (1) its occurrence was predictable, (2) appropriate preventive measures (including measures to reduce damage) existed, and (3) a breach of the organization’s duty of care was a significant cause of the incident.” He attempted to conduct a statistical analysis based on a questionnaire. However, it has not been verified whether the respondents’ answers strictly conformed to the above definition of fraud. Additionally, there is the problem of sample bias, as respondents who did not answer the questionnaire were not included in the analysis. |

| 12 | Beasley (1996), Uzun et al. (2004), Farber (2005), Krishnan (2005), Abbott et al. (2000), Khanna et al. (2015), Nakamura (2001) and Kobayashi et al. (2010) use keyword-based definitions. |

| 13 | Covered companies are those who are listed on the NYSE (New York Stock Exchange), AMEX (American Stock Exchange), and NASDAQ (National Association of Securities Dealers) between 1980 and 1991. |

| 14 | Kobayashi et al. (2010) use keywords: “Scandal,” “Bid-rigging,” “Misrepresentation,” “Factories accidents,” “System trouble,” “Unpaid overtime,” “Violation of the Waste Disposal and Public Cleansing Law,” “Fraudulent accounting,” “Income concealment,” “Benefit provision,” “Cartel,” “Insider,” “Unfair bargain sale,” “Embezzlement” and “Misappropriation” to extract information from the articles of Nikkei Telecon 21 (1 January 2000–31 December 2003) pertaining to companies listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. |

| 15 | Fraud cases were extracted from Nikkei Telecon 21 (Limited Edition for Public Library) and the FCG Research Institute, Inc.’s “list of the latest corporate incidents and scandals” (https://www.fcg-r.co.jp/research/incident/ (accessed on 31 August 2017)). |

| 16 | While it might be more appropriate to use the broader concept “misconduct” rather than “fraud”, we follow previous research and use the term “fraud”. |

| 17 | We handled dates related to fraud as follows: Based on the content of the article, the time of occurrence and termination were determined up to the year and month, and the latent period until detection and the duration of the offense were determined for each case. For cases where the exact date could be identified, we specified the year and month. If the month could not be identified, it was assumed to be June of that year for expediency. Cases where the time of completion could not be identified were assumed to have been completed on the first press day (i.e., the date of detection). The date of the first news report was treated as the publication date and regarded as the detection date. However, for magazine articles, the month of publication was regarded as the detection month. Indeed, there are probably two types of detection depending who detects fraud: detection by media (public) and detection by legal authorities. |

| 18 | When we focus only on financial reporting irregularities, which are often seen in previous studies in the U.S., it is somewhat reasonable to regard the year in which the crime occurred as the year in which it was detected because the fraud was committed in the same year in which the fraud was detected by financial regulatory authorities. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | The appointment-based CEO connectedness is measured as the percentage of board members who joined the board after the CEO. |

| 21 | In a series of 19 articles, the latest trends of academic cliques (university clubs) such as “Mita-kai” of Keio University, “Inamon-kai” of Waseda University, “Koyu-kai” of Tokyo University and “Josui-kai” of Hitotsubashi University are introduced. |

| 22 | One of the few academic analyses is Kawaguchi and Ma (2008). |

| 23 | Onji et al. (2019) pays attention to the “academic clique” which is said to have been formed in commercial banks after the end of the Meiji period, and quantitatively examines how personal networks such as academic cliques were transformed by government intervention in management by its capital injection at the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s. |

| 24 | Even if they are from the same prefecture, they are not necessarily from the same high schools. However, each prefecture has some major high schools that often produce company directors. |

| 25 | For more detailed explanations of each variable, see Table 1. As described by Shibuya (2016), the second form, “companies with a nominating committee, etc.”, which strictly separates supervision and business execution, did not spread among Japanese companies due to its need for many outside directors. To accelerate the form change in Japanese companies, “Company with Audit and Supervisory Committee” was introduced as the third option. Variables dmt and dmt2 capture the ranking in terms of the degree of separation between supervision and business execution among the three governance forms. |

| 26 | Khanna et al. (2015) introduced governance indicators, but they are skewed towards those related to CEOs, since “Connection to CEO based on appointment” is the main focus of their analysis. |

| 27 | A diagram as shown in Figure 1 is called a “graph” in graph theory (the research field of mathematics that describes networks), an ◯ in a network is called a “node”, and a line segment is called a “link”. For more details about the basics and applications of complex network analysis, see Masuda and Konno (2010). |

| 28 | This definition is only used when the network has no directionality. An example of a directional network is when the executive director knows the contact information of the CEO, but the CEO does not know the contact information of the executive director. |

| 29 | Let j = 1 be the date of the occurrence of fraud, j = 2 be the period between occurrence of fraud and detection, and j = 3 be the date of detection of fraud. |

| 30 | As mentioned earlier, it is possble that there might be an endogeneity issue between fraud occurrence and dmt/dmt2. One possible source of endogeneity is the omission of firm-specific and board-specific factors that could correlate with both fraud and personal networks. Fixed effects for alma mater schools, in particular, could help capture the inclination towards fraud and the nature of personal networks. Unfortunately, our current dataset does not include sufficient information to implement these fixed effects. However, we recognize this as a limitation and suggest that subsequent studies collect more detailed data to address this issue. |

| 31 | As our data are from the data source of the Nikkei NEEDS Corporate Governance Report, although we could not find the clear definition from the database, we guess that the definition of outside directors is based on Article 2, Item 15 of the Companies Act (Item 16 of the same article for outside corporate auditors). Also, the definition of independent directors seems to be based on the “Practical considerations for ensuring an independent Executive Staff” of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Therefore, in this paper, outside directors are considered to include independent directors (although there are outside directors who are not independent directors, there are no independent directors who are not outside directors). |

| 32 | Although we construct a fraud dataset that includes 731 cases, the number of observations in Table 5 is much lower. There are two reasons: first, hazard model analysis is conducted by positive duration cases, so we need to exclude the case where “duration = 0”; and second, some explanatory variables, particularly directors’ personal information, are not recorded in our dataset. |

References

- Abbott, Lawrence J., Young Park, and Susan Parker. 2000. The Effects of Audit Committee Activity and Independence on Corporate Fraud. Managerial Finance 26: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, Ikuo. 2005. Social History of Educational Attainment: Education and Modern Japan. Tokyo: Heibonsha. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, Hidetaka. 2015. Empirical Analysis of Corporate Governance and Corporate Misconduct. Tokyo: Chuo University’s Analects of Economics, No. 86. pp. 67–77. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, Mark S. 1996. An Empirical Analysis of the Relation Between the Board of Director Composition and Financial Statement Fraud. The Accounting Review 71: 443–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, Raj, Matthew O. Jackson, Theresa Kuchler, Johannes Stroebel, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert B. Fluegge, Sara Gong, Federico Gonzalez, Armelle Grondin, Matthew Jacob, and et al. 2022. Social capital I: Measurement and associations with economic mobility. Nature 608: 108–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Lauren, Andrea Frazzini, and Christopher Malloy. 2008. The small world of investigating: Board connections and mutual fund returns. Journal of Political Economy 116: 951–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIAMOND Online. 2019. New School Clique: Sokei, the University of Tokyo, Hitotsubashi, and Prestigious High Schools. Available online: https://diamond.jp/list/feature/p-ob_network (accessed on 22 July 2020). (In Japanese).

- El-Khatib, Rwan, Kathy Fogel, and Tomas Jandik. 2015. CEO network centrality and merger performance. Journal of Financial Economics 116: 349–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, David B. 2005. Restoring Trust after Fraud: Does Corporate Governance Matter? The Accounting Review 80: 539–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, Cesare. 2017. Corporate finance policies and social networks. Management Science 63: 2420–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, Cesare, and Geoffrey Tate. 2012. External networking and internal firm governance. The Journal of Finance 67: 153–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Taketoshi. 2019. Development and Analysis of a Database on Corporate Fraud: Characteristics of Incidents and Latent Periods until Disclosures by Industry. Economics and Sciences 16: 1–14. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, Haruhiko. 2012. Research on Organizational Misconduct: Clarification of Potential Causes of Organizational Misconduct. Tokyo: Hakuto-shobo Publishing Co., Ltd. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Matthew O. 2014. Networks in the understanding of economic behaviors. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 28: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Daiji, and Wenjie Ma. 2008. The causal effect of grading from a top university on promotion: Evidence from the University of Tokyo’s 1969 admission freeze. Economics of Education Review 27: 184–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khanna, Vikramaditya, E. Han Kim, and Yao Lu. 2015. CEO Connectedness and Corporate Fraud. The Journal of Financ LXX: 1203–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Takanori, Yoshida Yasushi, and Morihei Soichiro. 2010. Corporate Scandals and Stock Market Valuations. ARIMASS Annual Research Report. Kanagawa: Association for Risk Management System Studies, pp. 53–75. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kramarz, Francis, and David Thesmar. 2013. Social networks in the boardroom. Journal of the European Economic Association 11: 780–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, Jayanthi. 2005. Audit Committee Quality and Internal Control: An Empirical Analysis. The Accounting Review 80: 649–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Naoki, and Norio Konno. 2010. Complex Networks: From Fundamentals to Applications. Tokyo: Kindai Kagakusha. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Mizuho. 2001. Conditions for realizing corporate ethics. Meiji University Social Science Research Journal 39: 87–99. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Onji, Kazuki, Takeshi Osada, and David Vera. 2019. Old-Boy Networks, Capital Injection, and Banks Returns: Evidence from Japanese Banks. Paper presented at 3rd Sydney Banking and Financial Stability Conference, Sydney, Australia, December 13–14. Mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, Dale J. 1980. Partial Observability in Bivariate Probit Models. Journal of Economics 12: 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, David. 2019. Political connections and allocated distortions. The Journal of Finance 74: 543–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, Kenichi. n.d. Facilitating Better Corporate Governance in Japan—How Do the Proposed Amendments to the Companies Act Change the Corporate Governance of Japanese Companies? Chiyoda City: Mori Hamada & Matsumoto.

- Shibuya, Takahiro. 2016. Audit and Supervisory Committee’ Evaluation system introduced 1 year, more than 400 companies established. Nihon Keizai Shinbun, July 25. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, Hatice, Samuel H. Szewczyk, and Raj Varma. 2004. Board Composition and Corporate Fraud. Financial Analysis Journal 60: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Tracy Yue. 2013. Corporate securities fleet: Insights from a new empirical framework. The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 29: 535–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Tracy Yue, Andrew Winton, and Xiaoyun Yu. 2010. Corporate Fraud and Business Conditions: Evidence from IPOs. The Journal of Finance LXV: 2255–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Explanations |

|---|---|

| dmn | The number of directors |

| dmt | Governance system: “Company with Nominating Committee, etc.” = 1, The others = 0 |

| dmt2 | Governance system: “Company with Audit and Supervisory Committee” or “Company with Nominating Committee, etc.” = 1, Company with Audit and Supervisory Board = 0 |

| dmc | Chairman of the Board of Directors: Outside Directors = 1, Others = 0 |

| dmte | Term of office of director in the articles of incorporation (year) |

| dmoutr | Ratio of the number of outside directors to that of directors |

| dmoutindr | Ratio of the number of independent directors to that of directors |

| adr | Ratio of the number of Audit and Supervisory Board members and Audit Committee members to that of directors |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||||

| fraud_dummy | 32,968 | 0.013 | 0.114 | 0 | 1 |

| (duration) | 731 | 40.167 | 60.075 | 0 | 624 |

| Variables related to Personal Network | |||||

| Densityschool | 12,126 | 0.326 | 0.379 | 0 | 1 |

| Meandegreeschool | 12,126 | 3.411 | 4.298 | 0 | 32 |

| Densityhome | 12,126 | 0.485 | 0.362 | 0 | 1 |

| Meandegreehome | 12,126 | 5.171 | 4.436 | 0 | 33 |

| Variables related to the form of governance | |||||

| dmn | 32,968 | 7.798 | 3.076 | 1 | 30 |

| dmt | 32,968 | 0.054 | 0.226 | 0 | 1 |

| dmt2 | 32,968 | 0.072 | 0.259 | 0 | 1 |

| dmc | 32,968 | 0.004 | 0.063 | 0 | 1 |

| dmte | 24,542 | 1.401 | 0.494 | 1 | 10 |

| dmoutr | 32,968 | 0.163 | 0.159 | 0 | 1 |

| dmoutindr | 32,968 | 0.095 | 0.132 | 0 | 1 |

| adr | 32,968 | 0.485 | 0.220 | 0 | 4 |

| Fraud_Dummy | Density School | Meandegree School | Density Home | MEANDEGREE Home | dmn | dmt | dmt2 | dmc | dmte | dmoutr | dmoutindr | adr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fraud_dummy | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Densityschool | 0.004 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (0.660) | |||||||||||||

| Meandegreeschool | 0.031 | 0.918 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | ||||||||||||

| Densityhome | 0.004 | 0.659 | 0.609 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (0.700) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||||||

| Meandegreehome | 0.045 | 0.545 | 0.656 | 0.868 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| dmn | 0.100 | −0.039 | 0.198 | 0.004 | 0.375 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.684) | (0.000) | |||||||||

| dmt | −0.018 | 0.014 | −0.015 | 0.013 | −0.036 | 0.120 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.001) | (0.134) | (0.097) | (0.145) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||

| dmt2 | 0.015 | 0.032 | −0.011 | 0.030 | −0.043 | 0.130 | 0.856 | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.006) | (0.000) | (0.217) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| dmc | 0.010 | 0.047 | 0.045 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.023 | 0.002 | 0.078 | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.086) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.759) | (0.000) | ||||||

| dmte | −0.033 | −0.037 | −0.053 | −0.014 | −0.027 | −0.132 | −0.225 | −0.255 | −0.050 | 1.000 | |||

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.216) | (0.016) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| dmoutr | 0.029 | 0.135 | 0.088 | 0.099 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.250 | 0.386 | 0.122 | −0.225 | 1.000 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.823) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| dmoutindr | 0.032 | 0.074 | 0.051 | 0.059 | 0.022 | 0.055 | 0.342 | 0.410 | 0.112 | −0.221 | 0.662 | 1.000 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.016) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| adr | −0.037 | 0.003 | −0.110 | −0.029 | −0.188 | −0.660 | −0.527 | −0.616 | −0.042 | 0.210 | −0.237 | −0.274 | 1.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.775) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Single Regressions | Multiple Regressions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (a)’ | (b) | (b)’ | (c) | (c)’ | (d) | (d)’ | |||

| Variables related to Personal Network | ||||||||||

| Densityschool | 0.132 | 0.143 | 0.291 | 0.286 | 0.304 | 0.305 | ||||

| (0.55) | (0.59) | (0.78) | (0.77) | (0.81) | (0.81) | |||||

| Meandegreeschool | 0.054 *** | 0.056 *** | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.027 | ||||

| (2.83) | (2.90) | (0.88) | (0.91) | (0.92) | (0.96) | |||||

| Densityhome | 0.003 | −0.007 | −0.101 | −0.083 | −0.107 | −0.098 | ||||

| (0.01) | (−0.03) | (−0.26) | (−0.22) | (−0.27) | (−0.25) | |||||

| Meandegreehome | 0.063 *** | 0.065 *** | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||||

| (3.51) | (3.51) | (0.07) | (0.17) | (0.04) | (0.11) | |||||

| Variables related to the form of governance | ||||||||||

| dmn | 0.188 *** | 0.200 *** | 0.253 *** | 0.287 *** | 0.260 *** | 0.288 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.275 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.277 *** |

| (11.59) | (12.03) | (5.98) | (6.58) | (6.08) | (6.46) | (5.42) | (6.00) | (5.51) | (5.91) | |

| dmt | −1.011 *** | −0.690 * | −1.855 ** | −1.444 * | −1.828 ** | −1.417 * | ||||

| (−2.69) | (−1.75) | (−2.28) | (−1.75) | (−2.25) | (−1.72) | |||||

| dmt2 | 0.16 | 0.51 ** | 0.035 | 0.165 | 0.079 | 0.210 | ||||

| (0.74) | (2.20) | (0.06) | (0.28) | (0.14) | (0.36) | |||||

| dmc | −0.149 | −0.112 | 0.182 | 0.348 | 0.084 | 0.183 | 0.173 | 0.328 | 0.074 | 0.163 |

| (−0.21) | (−0.16) | (0.19) | (0.36) | (0.08) | (0.19) | (0.18) | (0.34) | (0.08) | (0.17) | |

| dmte | −0.673 *** | −0.780 *** | −0.366 | −0.311 | −0.329 | −0.284 | −0.367 * | −0.313 * | −0.330 | −0.286 |

| (−4.26) | (−4.82) | (−1.59) | (−1.34) | (−1.41) | (−1.21) | (−1.60) | (−1.35) | (−1.42) | (−1.22) | |

| dmoutr | 0.912 ** | 1.510 *** | −0.687 | −0.679 | −0.822 | −0.825 | −0.716 * | −0.722 * | −0.852 | −0.868 |

| (2.45) | (3.73) | (−0.57) | (−0.56) | (−0.67) | (−0.67) | (−0.59) | (−0.59) | (−0.69) | (−0.70) | |

| dmoutindr | 0.924 ** | 2.067 *** | 2.874 ** | 2.755 ** | 3.932 *** | 3.921 *** | 2.886 ** | 2.761 ** | 3.949 *** | 3.926 ** |

| (2.40) | (4.03) | (2.26) | (2.14) | (2.91) | (2.88) | (2.26) | (2.14) | (2.92) | (2.88) | |

| adr | −1.056 *** | −1.572 *** | 1.710 ** | 2.859 *** | 1.704 ** | 2.621 *** | 1.686 ** | 2.858 *** | 1.677 ** | 2.623 *** |

| (−3.81) | (−5.11) | (2.06) | (3.11) | (2.05) | (2.76) | (2.02) | (3.10) | (2.01) | (2.76) | |

| Constant | −8.126 *** | −9.103 *** | −8.936 *** | −9.803 *** | −8.072 *** | −9.061 *** | −8.880 *** | −9.761 *** | ||

| (−8.83) | (−9.38) | (−9.18) | (−9.62) | (−8.85) | (−9.41) | (−9.20) | (−9.65) | |||

| Year FE(dummies) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | - | - | 8072 | 8072 | 8071 | 8071 | 8072 | 8072 | 8071 | 8071 |

| Company | - | - | 3026 | 3026 | 3025 | 3025 | 3026 | 3026 | 3025 | 3025 |

| Single Regressions | Multiple Regressions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | |||||||

| Variables related to Personal Network | ||||||||||

| Densityschool | 1.433 * | 2.139 ** | 1.980 * | |||||||

| (1.67) | Obs. 223 | (2.06) | (1.80) | |||||||

| Meandegreeschool | 1.025 | 1.050 * | 1.045 | |||||||

| (1.56) | Obs. 223 | (1.79) | (1.58) | |||||||

| Densityhome | 1.238 | 0.778 | 0.800 | |||||||

| (1.12) | Obs. 223 | (−0.78) | (−0.69) | |||||||

| Meandegreehome | 1.017 | 0.983 | 0.984 | |||||||

| (1.21) | Obs. 223 | (−0.70) | (−0.66) | |||||||

| Variables related to the form of governance | ||||||||||

| dmn | 0.969 ** | 0.988 | 0.965 | 0.982 | 0.958 | |||||

| (−2.29) | Obs. 424 | (−0.36) | (−0.85) | (−0.52) | (−0.99) | |||||

| dmt | 1.598 | 1.392 | 1.377 | |||||||

| (1.46) | Obs. 483 | (0.61) | (0.59) | |||||||

| dmt2 | 0.904 | 0.627 | 0.607 | |||||||

| (−0.94) | Obs. 483 | (−0.85) | (−0.91) | |||||||

| dmc | 1.487 | 0.867 | 0.940 | 0.975 | 1.047 | |||||

| (0.79) | Obs. 483 | (−0.19) | (−0.08) | (−0.03) | (0.06) | |||||

| dmte | 1.146 | 1.264 | 1.231 | 1.287 | 1.250 | |||||

| (1.14) | Obs. 358 | (1.23) | (1.08) | (1.31) | (1.16) | |||||

| dmoutr | .418 | 0.223 | 0.204 | 0.234 | 0.214 | |||||

| (2.45) | Obs. 424 | (−1.33) | (−1.40) | (−1.29) | (−1.36) | |||||

| dmoutindr | 1.619 | 8.889 * | 11.396 ** | 8.302 * | 10.959 ** | |||||

| (1.49) | Obs. 424 | (1.88) | (2.01) | (1.82) | (1.98) | |||||

| adr | 1.513 * | 1.374 | 0.564 | 1.310 | 0.517 | |||||

| (1.49) | Obs. 424 | (0.49) | Obs. 167 | (−0.50) | Obs. 167 | (0.41) | Obs. 167 | (−0.58) | Obs. 167 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osada, T.; Vera, D.; Hashimoto, T. Personal Networks, Board Structures and Corporate Fraud in Japan. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2024, 17, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17080314

Osada T, Vera D, Hashimoto T. Personal Networks, Board Structures and Corporate Fraud in Japan. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2024; 17(8):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17080314

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsada, Takeshi, David Vera, and Taketoshi Hashimoto. 2024. "Personal Networks, Board Structures and Corporate Fraud in Japan" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17, no. 8: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17080314

APA StyleOsada, T., Vera, D., & Hashimoto, T. (2024). Personal Networks, Board Structures and Corporate Fraud in Japan. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17080314