Abstract

This study examines factors influencing Ghanaian banks’ compliance with anti-money laundering (AML) legislation. Drawing upon institutional, compliance, and dynamic capability theories, the study identifies the interplay of organisational, regulatory, and employee factors influencing compliance outcomes. A mixed methods approach was used to collect data from 23 universal banks, 9 local and 14 foreign, in Ghana, focusing on experienced managers and employees in risk, legal, operations, compliance, and business development departments. The findings show that employee characteristics like due diligence and moral involvement have a positive relationship with compliance with AML regulations; however, contrary to expectations, effective AML/CFT programs did not significantly impact banks’ adherence to these regulations. The association between moral engagement, an innovative culture, and AML compliance is weakened by normative power and an innovative culture acting as negative moderators. This study contributes empirical evidence to the literature on AML compliance in emerging markets and offers practical implications for policymakers, regulators, and banking professionals seeking to boost regulatory effectiveness and mitigate financial crime risks. This study provides a foundation for targeted interventions and strategic initiatives aimed at strengthening the AML regulatory landscape in Ghana and other countries.

1. Introduction

In the past, social scientists have pointed out that developing countries remain on the losing end of the terms of trade in financial transactions because national profit levels filed by multinational corporations far exceed the direct investment figures. This disparity means that the subsidiary is shipping too much profit out of the country. This can be a result of many things, including transfer pricing and tax evasion, but in all of these studies and conclusions, the laundering of the money for the final conclusion of tax evasion has been an underlying issue (Otusanya and Adeyeye 2022; Antwi et al. 2023). In more recent times, money laundering has been directly linked to political corruption and the siphoning of money that was intended for public works or projects, in which the laundered funds are sent to foreign banks (Ofoeda 2022; Issah et al. 2022; Bawole and Langnel 2023). This form of money laundering has a devastating effect on a nation, and particularly poorer nations, in which the loss of significant funds can impede a country’s ability to develop (Hussain et al. 2022; Korauš et al. 2024).

Money laundering has now been recognised as an impediment to the economy and the state of affairs of several nations. The awareness of AML issues is quite recent in Ghana, and it gained a great deal of emphasis following the joint statement of condemnation from the Commonwealth on the expulsion of Saharan African country members at the 27th meet of the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group in September 2007. The member nations of the Commonwealth expressed their outrage at the unconstitutional governments and political situations of several African countries. This statement has led to the commitment to revitalise development in some African countries, and Ghana is trying to prevent the trend of siphoning government money to foreign countries and bring back money that has been sent abroad to be used in public works and projects (Nduka and Sechap 2021; Ahiauzu 2022; Otusanya and Adeyeye 2022; Ofoeda et al. 2023; Antwi et al. 2023). The significance of this form of money laundering to Ghana makes it a direct and indirect threat to the welfare of the nation and the economy, but this is only one case of the effect of money laundering in Ghana. Money laundering is a global problem, with the ability to affect any nation, rich or poor (Markovska and Adams 2015; Nance 2018; Vijeyan and Rahmat 2022).

The banking sector is a highly regulated industry in all countries, and banks in both developed and developing countries are required to comply with a wide range of regulations. The key reason for these regulations is to restore and maintain public confidence in the banking system, which is essential for financial stability and healthy economic growth (Agyenim-Boateng et al. 2020; Yomboi et al. 2021; Barnett-Quaicoo 2021; Torku and Laryea 2021; Klutse and Kiss 2022). The regulatory environment within the banking sector has evolved over the years, especially with the current global emphasis on money laundering and financing terrorist activities (Amenu-Tekaa 2022; Basaran-Brooks 2022). Due to the different forms of money laundering and their implications, the importance of Ghanaian banks having a full understanding of money laundering and compliance with AML legislation is ever more crucial, but still, the understanding and internalisation of regulations are insufficient (Tsingou 2018; Zaman et al. 2021).

Therefore, a nation’s compliance with anti-money laundering standards plays a vital role in enhancing the integrity of the global financial system (Nobanee and Ellili 2018; Gilmour 2022; Issah et al. 2022; Antwi et al. 2023). This practice has not just become a national but a global phenomenon, in which criminals exploit national differences by moving the proceeds of their crimes through countries with less stringent controls (Tsingou 2018; Son et al. 2020; Joshi and Shah 2020; Levi and Soudijn 2020; Zaman et al. 2021). Tax evasion, bribery, drug trafficking, cybercrime, human trafficking, and other financial crimes are carried out to make financial gains. The perpetrators of these crimes require a medium with which to disguise and access their illicit funds, often through financial institutions (FIs), due to the low cost and efficiency of carrying out their transactions (Lord et al. 2018; Viritha and Mariappan 2016; Pavlović and Paunović 2019; Xu et al. 2019; Albanese 2021; Takyi et al. 2022; Ofoeda et al. 2022). Unfortunately, such activities stain the integrity of these FIs, with a consequent severe impact on their financial soundness, resulting in a negative impact on investor confidence (Aluko and Bagheri 2012; Kar 2013; Klein and Weill 2018; Ho et al. 2019; Nduka and Sechap 2021).

Anti-money laundering (AML) regulations have been put in place to make the process of money laundering (ML) unattractive to criminals, take the proceeds out of crime and ensure that the integrity of banks and nations, in general, is protected (Kar 2013; Levi et al. 2014; Samuel et al. 2014; Isa et al. 2015; Islam et al. 2017; Korejo et al. 2021; Elaiyarajah and Hagevik 2022). The implementation of the framework to ensure compliance with these regulations is intertwined with banks’ existing processes. International standards or recommendations on anti-money laundering, regulations, and guidance by monitoring and supervisory authorities like the Financial Intelligence Centre and the Bank of Ghana primarily underscore banks’ operations.

The relationships’ linearity in the extant literature has presented a research gap, as the impact of moderators on these predominant constructs are not embraced. This study identifies the importance of compliance with the regulations and is arguably one of the first empirical studies to explore the antecedents of compliance with AML regulations in the Ghanaian banking industry, as well as the impact of compliance on organisational outcomes using the selected outcome variables, providing data for future researchers. Ghana was selected as a case study due to its unique political, economic, and social context. The frequency and nature of money laundering activities in Ghana, as well as the regulatory framework and enforcement mechanisms in place, could offer valuable insights into the effectiveness of anti-money laundering measures. Additionally, conducting research in Ghana provides easier access to applicable data, such as financial transaction records, regulatory reports, and enforcement statistics, which could be applied in West African regions and globally. This study is anticipated to yield value for the banking industry, regulators, compliance professionals, and researchers. The study also revealed some challenges that stakeholders face in their quest to be compliant with regulations. This can assist FIs to incorporate strategies into their compliance programs to have both customers and clients comply with AML rules to realise their associated benefits.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 4 contains the materials and methods utilised in the study, while Section 5 presents the results obtained. Section 6 and Section 7 are dedicated to discussing the findings and their contribution to knowledge, respectively, as well as the conclusions of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Moral Involvement

Despite the general paucity of scholarly inquiries into the correlations between employees’ moral involvement and compliance with anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) regulations and policies, empirical evidence mainly supports the position. Previous studies have explored the relationship and found that high levels of moral involvement among employees will positively and strongly affect their compliance behaviours (Hyle 2006; Lunenburg 2012; Schmidt 2021). Thus, when compliance officers base their actions on deep-seated feelings of moral obligation and view corporate values and ethics as congruent with their perceptions of what ought to be done, they are more likely to comply with AML/CFT regulations and policies diligently. According to Lunenburg (2012), the moral involvement of employees, in this case, compliance officers, will contribute significantly to creating a strong sense of commitment to those organisational characteristics and processes deemed to be socially beneficial, including AML/CFT compliance attitudes. More so, moral involvement creates the needed organisational atmosphere for the enhancement of compliance behaviours, especially in relation to the combating of money laundering and terrorism financing (Foorthuis and Bos 2011).

2.2. Due Diligence

The work of ElYacoubi (2020) has supported the existing relationship between customer due diligence (CDD) practices in the form of effective customer identification, transaction monitoring, and risk assessments regarding bank customers, products and services, delivery channels, jurisdictions on the ability of these institutions to meet the requirements of AML/CFT compliance regulations adequately, and laws. Chatain et al. (2009) have also cited customer due diligence among the essential factors that facilitate adequate compliance with AML/CFT policies among financial institutions. Similar positive findings have also been observed in Schott (2006), who explained the critical role of customer due diligence practices in improving compliance attitudes among financial institutions towards AML/CFT policies and regulations. Furthermore, all major international bodies and protocols, including reports and recommendations by the Basel Committee, FATF, and the IFC, have recognised the tremendous contributions of customer due diligence towards enhancing global compliance with AML/CFT regulations and policies. Without exception, these international bodies point to effective CDD practices as a prerequisite for any compliance efforts by financial institutions and banks (Schott 2006).

2.3. Effective AML/CFT Compliance Program

Important and authentic sources such as the IFC (2019) and FATF (2023) have acknowledged the key role of effective AML/CFT compliance programs in enhancing AML/CFT compliance levels within the financial sector, both locally and internationally. In extolling the numerous contributions of effective AML/CFT programs to state and global financial systems, these programs enable the relevant organisations to better comply with AML/CFT regulations and policies (Schott 2006; Manning et al. 2021; Murrar and Barakat 2021). When AML/CFT programs are appropriately designed to define and cover money laundering/financial terrorism predicate offences extensively, Schott (2006) believed compliance levels would significantly improve, and ML/FT crimes and offences would be easier to mitigate. Similar emphasis has been observed regarding the essence of effective AML/CFT regulatory frameworks in facilitating compliance among banks and relevant institutions with AML/CFT policies (Mekpor et al. 2018; Delle Foglie et al. 2023; Gaviyau and Sibindi 2023).

Pattnaik et al. (2024) and Yang et al. (2023) highlight the growing role of technology, especially artificial intelligence (AI), in the fight against financial crimes and money laundering. By automating the detection of suspicious activities, AI and machine learning algorithms could sift through extensive amounts of transaction data to spot unusual patterns and abnormalities that might reveal money laundering. Integrating AI into the financial sector could revolutionise the way money laundering is tackled, making risk management more efficient and enhancing global security. This technology not only enhances the accuracy of anti-money laundering (AML) efforts but also reduces false positives, enabling compliance teams to concentrate on other threats (Akartuna et al. 2022; Lokanan 2022; Bello et al. 2023).

2.4. Moral Involvement, Normative Power, and Compliance with AML Regulations

Although quite limited, the extant literature has explored the association between normative power and moral involvement in relation to their impacts on AML/CFT compliance among financial institutions and banks. Most notable among the sources on this correlation is Lunenburg (2012), who investigated the various forms of involvement emanating from varying typologies of power. Like Etzioni (1997), Lunenburg (2012) observed that when power takes the form of coercion, it yields a sense of hostility and ultimately results in what they described as “alienative involvement”. Additionally, both sources concluded that utilitarian power usually triggers rational behaviours among subjects and causes them to analyse the costs and benefits associated with compliance or noncompliance behaviours before making a decision. As such, utilitarian power creates some “calculative involvement” where subjects will most likely comply with AML/CFT regulations only if the costs outweigh the benefits and vice versa (Lunenburg 2012); however, what is of the utmost importance to this study is the compelling argument that normative power, when employed in organisations, almost always results in a high sense of moral involvement among subjects (Etzioni 1997; Lunenburg 2012). A similar positive connection between normative power and moral involvement has been observed in Dodge (2016), who argued that normative power causes participants or subjects to develop a strong sense of moral involvement with an organisation.

2.5. Due Diligence, an Innovative Culture, and Compliance with AML Regulations

The innovation in and subsequent incorporation of biometric data in fingerprints and facial recognition will significantly impact AML compliance through enhanced due diligence practices, such as the more manageable and accurate verification of bank customers. The major obstacle to the success of innovations regarding national ID systems, according to CGAP (2014), however, is the limitations concerning data privacy, which make it difficult for banks and other institutions to share customer data to enforce AML compliance regulations further freely. Once countries find effective ways of obviating this obstacle without unnecessarily compromising customer privacy, CGAP (2014) expressed optimism that innovation culture will catalyse the effectiveness of due diligence in ensuring compliance with AML regulations.

3. Theoretical Background

To comprehensively examine the intricate and multifaceted factors that have a profound impact on the level of compliance with anti-money laundering (AML) regulations in the banking sector of the country of Ghana, it is of the utmost importance and absolute necessity to meticulously establish a robust and all-encompassing theoretical framework that adeptly encompasses an array of diverse theories.

3.1. Compliance Theory

According to Etzioni (1997) and Lunenburg (2012), employee compliance can be achieved through an organisational work structure that integrates the elements of power and employee involvement. The degree of compliance rests with integrating the various forms of power and employee involvement. It is these multiple levels of integration between the various forms of power and employee involvement that Etzioni (1975) termed compliance theory. The compliance theory expounds on three forms of power: coercive power, utilitarian power, and normative power. Lunenburg (2012), drawing from Etzioni’s descriptions, articulated that coercive power employs force, compels, and threatens to gain control of low-level participants.

On the other hand, utilitarian power (also referred to as remunerative power) uses remuneration and other extrinsic rewards to control low-level participants, with such extrinsic rewards predominately emphasised by business firms. The third form is normative power, which controls through allocating intrinsic rewards, such as fascinating work, identifying goals, and contributing to society. Dodge (2016) further describes it as being characterised by the use of force or threat of force to maintain control. In determining which of the three forms of power was appropriate for this study, coercive power was excluded as it was found to be the “harsh” power, given that it centres mainly on the capacity to detect and sanction. Utilitarian power, as a form of power for organisations to achieve regulatory compliance, was also disregarded, as remuneration alone may not cause participants to act in a particular way (Thomas et al. 2012; Aluko and Bagheri 2012). Arguably, in organisations where coercive power is used, participants respond to an organisation with hostility, translating into alienative involvement. Utilitarian power generally results in calculative involvement; participants desire to maximise personal gain. Ultimately, normative power often creates moral involvement; for instance, participants are committed to the socially beneficial features of their organisations. In this study, the researcher employs the third typology of power and involvement, which includes the interaction between normative power and moral involvement.

3.2. Dynamic Capability Theory

The dynamic capability theory explains how due diligence and an effective AML compliance program directly affect compliance with AML regulations and the moderating role of innovation culture. The dynamic capability theory reflects flexibility and adaptability to prevailing business conditions. In the view of the main proponents of the dynamic capability theory, Teece et al. (1997) explained the theory as the ability “to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal-external competencies to address rapidly changing environments”. In other words, the dynamic capability theory reflects an organisation’s capacity to attain new and innovative forms of doing business, considering their internal and external business environment conditions (Leonard-Barton 1992). The ability of firms to effectively reconfigure and transform their work processes through the integration of their internal and external competencies requires constant surveillance of the market, consumer behaviours, and new technology trends, as well as their willingness to adopt best practices (Chowdhury and Quaddus 2017).

3.3. Institutional Theory

Institutional theory is a sociological perspective that deeply examines the profound ways in which societal norms, deeply ingrained values, and strongly held beliefs shape and influence organisations of all types and sizes, spanning across multiple industries and sectors. This powerful and compelling theory pays meticulous attention to understanding, analysing, and unravelling the complex and intricate interplay between institutions and organisations, shedding light on how various forms of institutions, ranging from laws and regulations to deeply rooted cultural norms and traditions, exert tremendous influence over the structures, behaviour, and meticulously crafted strategies of organisations (Eilert and Nappier Cherup 2020; Shibin et al. 2020; Fligstein 2021; Nite and Edwards 2021; Peters 2022).

Institutional theory goes far beyond a mere analysis of the internal factors that shape and mould organizations, such as resource availability and trusted decision-making processes; instead, it meticulously unravels the intricate and inextricable linkages between organisations and the broader, all-encompassing institutional contexts in which they invariably operate. Drawing on a vast array of social, political, and economic factors, institutional theory leaves no stone unturned in its relentless pursuit of understanding and explaining why certain organisational patterns and practices rise to dominance, while others may be facing marginalization or even the dire fate of vanishing altogether (Hallett and Hawbaker 2021; Agoba et al. 2023).

In essence, institutional theory provides an invaluable framework that holistically captures and illuminates the multifaceted and dynamic nature of the interactions and exchanges that continuously occur between organisations, society, and the vast institutional environment in which they find themselves inseparably embedded. With its robust and comprehensive analysis, this theory uncovers the underpinnings of these intricate relationships, offering key insights into the intertwined forces and influences that shape the destinies of organizations. By providing a deep understanding of the intricate web of interactions, institutional theory equips scholars, researchers, and practitioners with the requisite tools to untangle the complex dynamics and navigate the labyrinthine landscape of modern organizations.

3.4. The Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

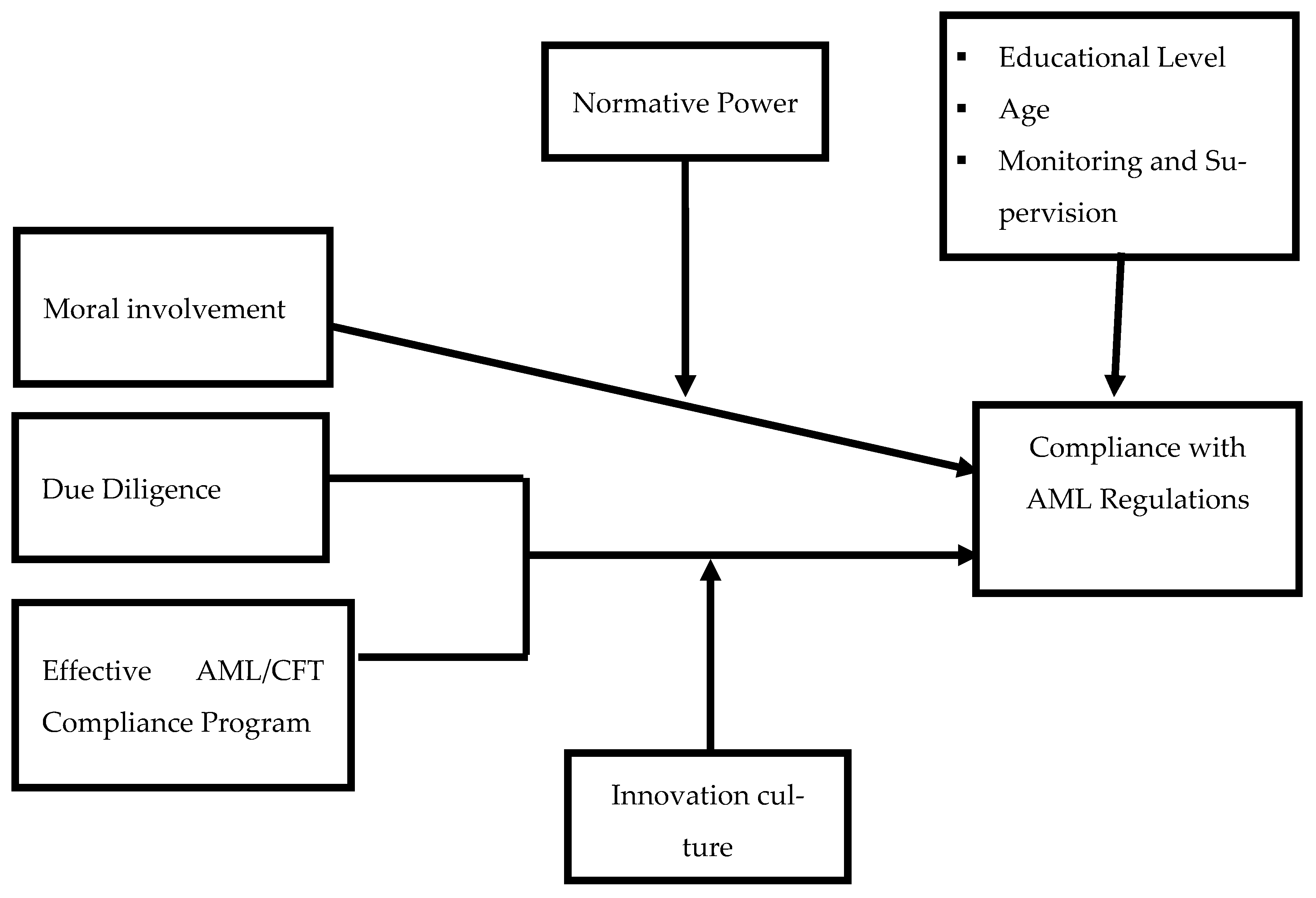

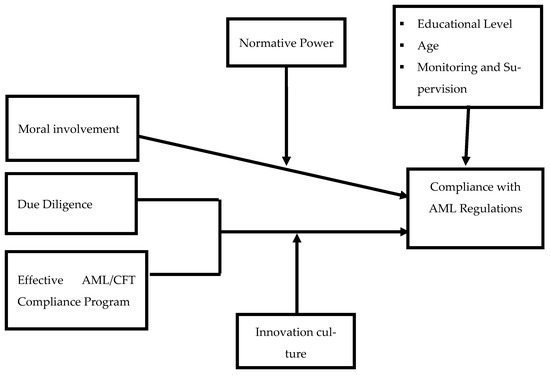

To address the associated gaps in the literature and, most notably, in practice, this study postulated the conceptual model below:

From the conceptual model above (Figure 1), this study conceptualised that moral involvement, customer due diligence, and an effective AML/CFT program will directly affect banks’ compliance with AML regulations. The framework further holds that the direct relationship between moral involvement and banks’ compliance with AML regulations will be moderated by normative power. Additional, an innovation culture, per the model, is used to moderate the relationship between due diligence and banks’ compliance with AML regulations in addition to the relationship between an effective AML/CFT program and banks’ compliance with AML regulations.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

To test the conceptual model shown above, this study operationalised the various conceptualised relationships into specific, measurable research objectives and hypotheses, which are provided below.

3.5. Moral Involvement and Compliance with AML/CFT Regulations

A direct correlation exists between moral involvement and compliance with AML policies and regulations from the conceptual model. This means that strong feelings of psychological attachment among employees, especially compliance officers, to the values, objectives, norms, and high standards of ethical behaviour will positively influence their AML compliance behaviours and, by extension, compliance within the entire organisation. Previous studies (Lunenburg 2012; Ezugwu and Samuel 2011; Hyle 2006) have indicated significantly strong and positive support for employees’ moral involvement to enhance AML compliance attitudes among financial institutions and banks at both the individual and organisational levels. Lunenburg (2012) argued that whenever compliance officers base their actions on deep-seated feelings of moral obligation and view corporate values and ethics as congruent with their perceptions of what ought to be done, they are more likely to diligently comply with AML/CFT regulations and policies and carry the organisation with them along the path of compliance. Foorthuis and Bos (2011), Markovits (2014), and Hussain et al. (2022) acknowledged and concluded a positive correlation between employees’ moral involvement and enhanced AML compliance among financial institutions and banks. Based on the above, the following hypothesis was formulated to measure the relationship between employee moral involvement and compliance with AML regulations.

Ho1:

There is no positive relationship between employee morale involvement and compliance with AML regulations.

3.6. Due Diligence and Compliance with AML/CFT Regulations

The conceptual model suggests that due diligence practices, such as for customers, products, services, delivery channels, jurisdictions, etc., will positively influence AML compliance levels within financial organisations. Based on compelling findings and reliance on recommendations and expert opinions presented by internationally mandated anti-money laundering institutions like the FATF, IFC, Basel Committee, etc. (Ginting and Chairunissa 2021; Delle Foglie et al. 2023). Schott (2006) argued that CDD practices and procedures play significant roles in enhancing compliance with AML protocols among financial institutions and banks. In line with global acknowledgements and recommendations, Schott (2006) designated CDD practices and processes as a prerequisite for the success of any compliance efforts by financial institutions and banks. Meanwhile, Chatain et al. (2009) alluded to other scholarly calls in support of CDD, with which they argued that the key practices and activities undertaken during CDD have significant positive implications for the AML compliance attitudes of financial institutions. According to McLaughlin and Pavelka (2013), there are strong correlations between CDD mechanisms and practices and banks’ ability to comply with AML regulations. Shust and Dostov (2020) also confirm the assessment of the reality of CDD in some countries. Consequently, the study hypothesized the following:

Ho2:

Due diligence has no significant effect on compliance with AML regulations.

3.7. Effective AML Program and Compliance with AML/CFT Regulations

There have been several recommendations by the FATF (2023) regarding the key elements that AML programs should contain to facilitate high AML compliance levels among banks and related institutions. According to Schott (2006), AML programs that are highly effective contribute significantly to the capacity of financial institutions to better comply with AML regulations at institutional, state, and international levels. Furthermore, Schott asserts that well-designed AML programs can comprehensively define ML offences and key processes involved in identifying and filing ML suspicions, thereby removing all ambiguities, and enhancing AML compliance among individuals and organisations. Mekpor et al. (2018) and Sharman (2008) have made compelling arguments favouring effective AML programs for varying levels of AML compliance among countries and institutions. By implication, the success or otherwise of banks and financial systems in ensuring higher levels of AML compliance is directly linked to the effectiveness of their AML compliance programs. Further evidence supporting these deductions is contained in a study published by Yepes (2011), which regarded effective AML programs as critical success factors of enhanced AML compliance among banks and financial institutions. Consequently, there was the following hypothesis:

Ho3:

There is no positive relationship between an effective AML/CFT compliance program and compliance with AML regulations.

3.8. Moral Involvement and Compliance with AML/CFT Regulations: The Moderating Role of Normative Power

The principal assumption here is that normative power will enhance the effectiveness of employees’ moral involvement in improving AML compliance among relevant institutions and national as well as global financial systems. This assumption has been proven empirically by Lunenburg (2012), who studied the correlations between various forms of power and their resultant impacts on employees’ (compliance and commitment) attitudes. As espoused earlier, among the three categories of power identified by Lunenburg, only normative power demonstrated the ability to enhance the moral involvement of employees, and particularly compliance officers, towards achieving higher AML compliance levels. Additional evidence and arguments have also been adduced by important sources such as Etzioni (1997) and Dodge (2016) to validate assumptions regarding the strong and positive correlations between normative power and moral involvement, as well as their combined strength in enhancing AML compliance among banks. The moderating influence of normative power on the correlation between moral involvement and compliance with AML regulations has also been extolled in Malloy (2003), Zaelke et al. (2005), and Foorthuis and Bos (2011). They identified cooperation and assistance as outcomes of moral involvement (a consequence of normative power) necessary for creating voluntary compliance attitudes at both the individual and institutional levels.

Markovits (2014) noted that employees’ moral involvement expressed in normative commitment is critical in enhancing compliance and altruistic behaviours towards an organisation’s regulations and procedures. In effect, the higher the moral involvement among employees, the higher the propensity for ethical behaviours, such as compliance with AML/CFT regulations. Consequently, we hypothesised the following:

Ho4:

The positive relationship between employee moral involvement and compliance with AML regulations will not be stronger if normative power is high than when it is low.

3.9. Due Diligence and Compliance with AML/CFT Regulations: The Moderating Role of an Innovative Culture

The conceptual framework reveals a moderating role of an innovation culture in the relationship between due diligence and AML compliance. This means that the effectiveness of due diligence in guaranteeing compliance with AML regulations will be enhanced by adopting a positive innovation culture. This was the view expressed in CGAP (2014) and Shust and Dostov (2020), wherein the ability of various due diligence processes and practices to result in AML compliance was influenced by an innovation culture. Similar positive findings have been observed in the AFI Special Report (2019) to strengthen the arguments favouring the moderating influence of an innovation culture on the correlation between customer due diligence and banks’ compliance with AML regulations. Based on these arguments and observations, we hypothesised the following:

Ho5:

The positive relationship between due diligence and compliance with AML regulations will not be stronger if a firm’s innovation culture is high than when it is low.

3.10. Effective AML Programs and Compliance with AML/CFT Regulations: The Moderating Role of an Innovative Culture

The model reveals the moderating role of an innovation culture on the relationship between effective AML programs and compliance with AML/CFT regulations. This study uncovered empirical support and arguments favouring the assumption from the extant literature. In the FCA (2017), a positive innovation culture was essential in improving the relationship between effective AML programs and AML compliance. As has been adduced earlier, the same source indicated that the ability of effective AML programs to yield the desired AML compliance attitudes among financial institutions could be enhanced through the adoption of positive innovation cultures that lead to the creation, acceptance, or diffusion of modern technologies aimed at facilitating onboarding and maintenance activities as well as processes of these institutions. The replacement of manual features of otherwise effective AML programs with automated systems will enhance the strength of causal correlations between such programs and compliance with AML regulations (FCA 2017). Based on this, we therefore hypothesised the following:

Ho6:

The positive relationship between an effective AML/CFT program and compliance with AML regulations will be stronger if a firm’s innovation culture is high than when it is low.

4. Materials and Methods

A survey method was used to collect data to empirically test the relationship between the antecedent factors of anti-money laundering regulation compliance and actual compliance (Samuel et al. 2014; Mohammed et al. 2020). This study’s data collection involved primary data collected from 23 universal banks operating in Ghana. These banks included nine (9) local banks and fourteen (14) foreign banks. The local banks were as follows: National Investment Bank (NIB), Ghana Commercial Bank (GCB), Agriculture Development Bank (ADB), Universal Merchant Bank (UMB), Consolidated Bank Ghana (CBG), Omni-BSIC Ban, Fidelity Bank, Cal Bank, and Prudential Bank. The foreign banks were as follows: Bank of Africa, Zenith Bank, First Atlantic Bank, United Bank of Africa (UBA), Standard Chartered Bank, Absa (Barclays bank), Stanbic Bank, Ecobank, Guaranteed Trust (GT) Bank, First Bank Nigeria (FBN), First Atlantic Merchant Bank (FAMB), Societe-Generale (SG) Bank, Access Bank, and Republic Bank. Universal banks were chosen as a proxy for the banking sector because they handle the majority of foreign transactions in the country. The focus was on managers and employees at the head office branches where the compliance teams operated. A purposive sampling method was used to solicit the views of experienced and knowledgeable officials across employees working in the industry’s risk, legal, operations, compliance, and business development departments. Thus, the study focused on employees working in the risk, compliance, and forex units.

A semi-structured questionnaire was used as the method of data collection due to its flexibility and cost-effectiveness in gathering information from large samples within a short period (Saunders et al. 2009; Li et al. 2020; Otoo et al. 2021; Cantah et al. 2023). The questionnaire is structured into three main sections, which are demographic data, information on the dependent variable, and information on the independent variables. The study administered three hundred questionnaires and received two hundred back. This falls above the one hundred and fifty thresholds recommended by Hair et al. (2010). After the questionnaires were developed, this study checked for the validity of the questions posed to measure each construct. The face and content validity of the instrument was established by subjecting the questionnaire to the evaluation of experts in the banking industry. Reliability of the instrument was established by measuring the internal consistency of the instrument using a reliability coefficient suggested by Fraenkel et al. (2023). Fraenkel et al. (2023) suggested that the reliability coefficient should be at 0.70 or preferably higher. The results of the reliability test conducted during the data analysis revealed reliability coefficients of greater than 0.70, thus suggesting satisfactory reliability. The details of the results are contained in chapter four of this work under data analyses.

The responses for questions measuring each of these variables were solicited on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponds with strongly disagree, 2 corresponds with disagree, 3 corresponds with neutral, 4 corresponds with agree, and 5 corresponds with strongly agree.

The following regression model was formulated to test the quantitative data generated for the study:

where COMP represents compliance with AML regulations. MI, CDD, and EAML represent moral involvement, customer due diligence, and an effective AML/CFT programme, respectively. The SIZE variable represents a bank’s total assets. PROF denotes profitability, measured as net income divided by the total assets of banks. Others include IC, NP, EDL, MONSUP, and AGE, which denote an innovation culture, normative power, education level, monitoring and supervision, and age, respectively.

COMP = f(Moral involvement + Customer Due Diligence + Effective

AML/CFT+ Bank Size + profitability, Innovation Culture, Normative Power,

Educational Level, Monitoring and Supervision, Age)

AML/CFT+ Bank Size + profitability, Innovation Culture, Normative Power,

Educational Level, Monitoring and Supervision, Age)

The need for stationarity in the dataset is vital in determining the direction of the analysis, and consistency in these variables makes predictions more reliable (Nobanee and Ellili 2018; Premti et al. 2021; Ofoeda 2022; Dartey et al. 2024).

Using both the augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron unit root tests to confirm the stationarity of the dataset, Table 1 and Table 2 below show that all variables (both dependent and independent) are stationary at levels, as well as at first differences. This stability means that the selected variables do not exhibit trends or seasonality that change over time, making them more predictable and easier to model accurately. Therefore, this study employs multiple regression and the Johansen cointegration to analyse the hypotheses formulated for the study. The qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Table 1.

Unit root test.

Table 2.

Summary of the order of integration of unit root test.

5. Results

Table 3 below shows the descriptive statistics of the dataset.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

5.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The CFA was carried out to determine the nature and magnitude of variation and covariance among a range of indicators by latent variable models (factor analysing), to provide a more parsimonious interpretation of the covariation between a set of variables (Brown 2015).

In Table 4, it can be noted that all of the items retained in the measurement of the different constructs exceeded the minimum threshold point of 0.50, concerning the standard factor loading (SFL). Thus, the retained items are excellent indicators for the constructs to be measured. Furthermore, it can be noted that all constructions have Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70. Hence, within the reliability framework with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70 as a benchmark, all standard factor loadings are reliable. It can also be noted that the composite reliability (CR) exceeds that criterion for all constructs and is therefore reliable with the same reliability benchmark.

Table 4.

Summary of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

5.2. Model Fit and Validity of Constructs

Table 5 summarises the model fit indicators and how well they fit.

Table 5.

Summary of model fit index outcomes.

Table 5 also defines the model fit indices for the confirmative factor analysis as well as the standard factor loading (SFL) and reliability tests. Fit indices are used to evaluate how far a model suits a particular dataset (Rao et al. 2012). Although different fit indices are adopted, the current study adopts only a few (McDonald and Ringo 2002). The model fit indices reported for the CFA include chi-square models (X2), the RFI (relative fit index), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the root average residual square index (RMR), and the described average value (AVE).

Eight major model fit indices were used to assess the overall fitness of the pattern, in line with Perry 2020. These are the ratio of X2 to the degrees of freedom (d.f.), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the normed fit index (NFI), the goodness of fit index (GFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI), as well as the AVEs for each construct. As shown in Table 4, all of the model indices were within the accepted levels, confirming the measurement model as a good fit with the data collected. As presented in Table 5, CMIN/df = 1.723, RFI = 0.800, NFI = 0.800, IFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.900, CFI = 0.901, and RMSEA = 0.60. The AVEs for each individual construct are reported in Table 6 to confirm the convergent and discriminant validity of the items measuring each construct.

Table 6.

Serial and heteroscedasticity test results.

In addition to the above, Table 6 below shows the results of the autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity tests. The p-value exceeds 5%, indicating that there is no evidence of autocorrelation or heteroscedasticity in the model’s residuals.

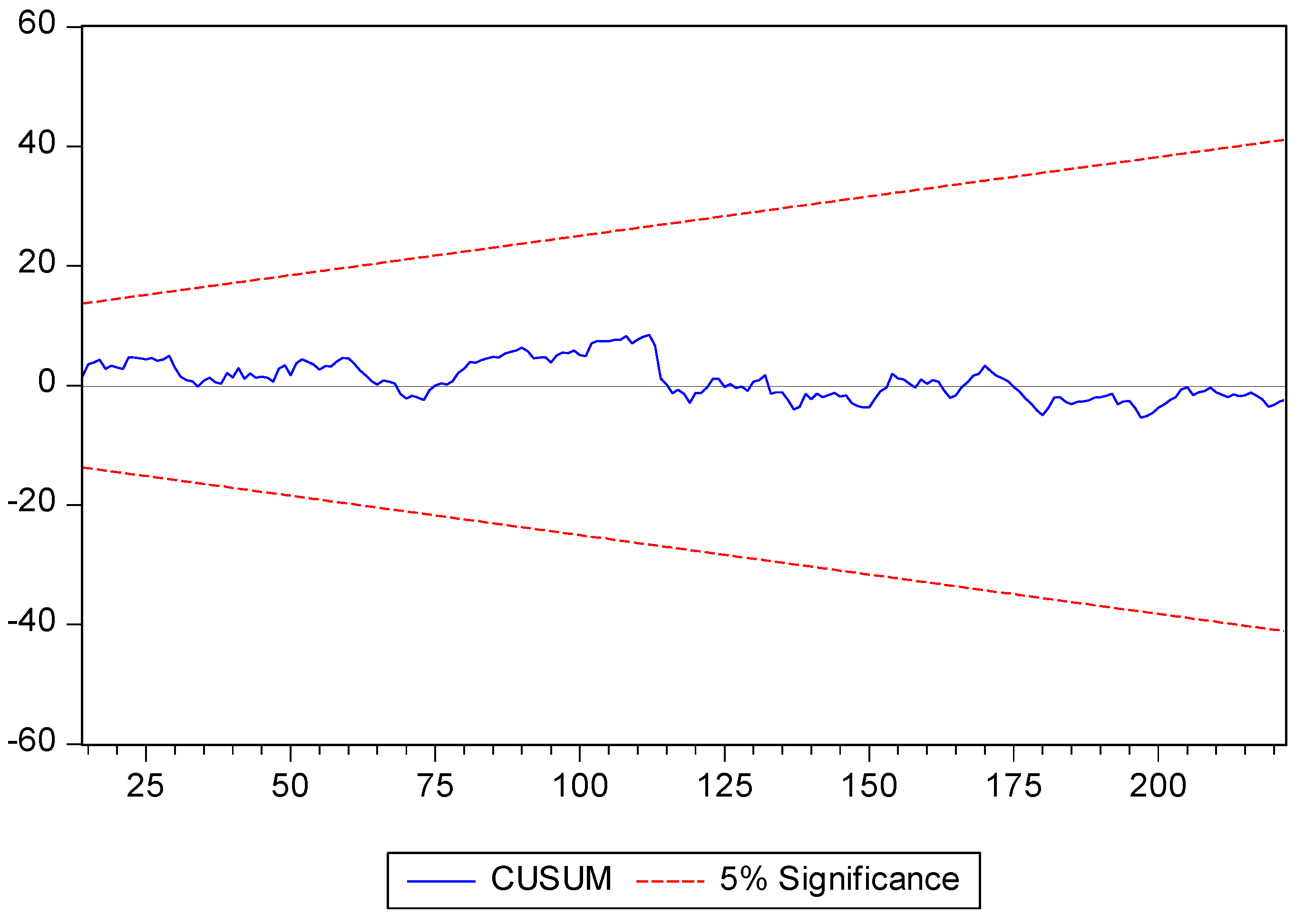

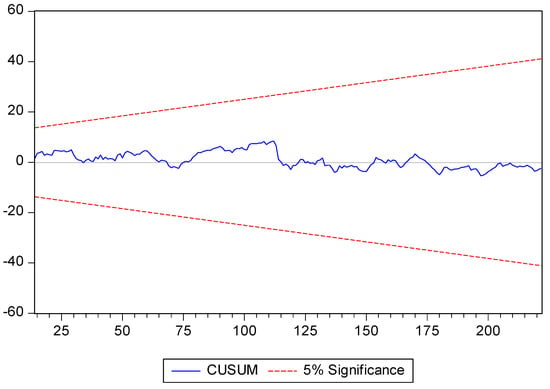

Figure 2 below further confirms the model’s stationarity. We used the CUSUM test to check for any changes or consistency in the model’s parameters over time. The results show that the cumulative sum remains stable within the control limits (two standard deviations from the mean) throughout the period, indicating no significant deviation or structural changes.

Figure 2.

Stability test.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

In comparison to the inter-item correlations, the convergent validity of the various structures within the framework of this study was squarely linked to the average variance extracted (AVE). When the chi-square is larger than the correlations between the items, then discrimination is confirmed (Messick 1995). The convergent validity result is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Validity of constructs.

5.3. Correlation and Normality of Measures

A normality test of all individual measures was conducted to examine the spread of all of the measures in the questionnaire. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was computed to determine the relationship between the different dimensions of the regression model. For all of the structures used for this study, their corresponding correlation matrix is shown in Table 8. The correlation between all of the variables was relatively low, below the specified threshold of 0.70, thereby eliminating any multicollinearity problems.

Table 8.

Correlation matrix.

Regression analysis with the variance inflation factor (VIF) values confirmed a further test of multicollinearity (see Table 9). In all of the models, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) showed that they were all below 10, the limit proposed by Kutner et al. (2005). The multicollinearity problem is therefore minimized in the analysis. The table also shows the normality of the different constructions as shown by the skewness and kurtosis values.

Table 9.

Collinearity statistics.

Based on the previous description of the normally stratified data for the skewness and kurtosis values, Table 7 shows that the responses collected from each construct are normally distributed. The validity (convergent) of the different constructs used in this study is also provided in Table 7. The AVEs represent the convergent values of validity. Table 7 shows a visual representation of correlation coefficients, test results for normality, and validity values.

Moral involvement, as a compliance mechanism, had a substantial positive association with compliance with AML regulations at a 1% level of significance (r = 0.634, p < 0.01). Additionally, due diligence had a substantial positive association with compliance with AML regulations in Ghana at a 1% level of significance (r = 0.409, p < 0.01). Thirdly, effective AML compliance as a regulatory practice also had a substantial positive association with compliance with AML regulations at the 1% significance level. The other aspects of compliance with AML regulation mechanisms of banks in Ghana, namely normative power and an innovative culture, had significant correlations with compliance with AML regulations in Ghana.

5.4. Analysis and Results

A hierarchical regression test was performed to determine the outcome of the various hypothesised relationships, containing both the direct and moderating effect hypotheses. The hierarchical regression procedure employed in testing the study hypotheses was carried out in four models. The results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Regression results.

The Johansen cointegration test results in Table 11 show whether there is a long-term equilibrium relationship (cointegration) among the selected variables. The trace test statistic of 67.01446 is much higher than the critical value of 4.129906 at the 0.05 significance level, with a very low p-value of 0.0001. This means that we can reject the null hypothesis that there is no cointegration, indicating that there is at least one cointegrating equation at the 0.05 level.

Table 11.

Johansen cointegration test.

Similarly, the max-eigenvalue statistic of 67.01446 also exceeds the critical value of 4.129906 at the 0.05 significance level, with the same low p-value of 0.0001. This further supports the rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration, suggesting that there is at least one cointegrating equation among the COMP variables and the exogenous series (MI, CDD, EAML, SIZE, PROF, IC, NP, EDL, MONSUP, and AGE). This also implies that there is at least one cointegrating equation among the COMP variables and the exogenous series (MI, CDD, EAML, SIZE, PROF, IC, NP, EDL, MONSUP, and AGE). This means that there exists a long-term equilibrium relationship between COMP and these exogenous variables. The adjustment coefficient of −0.340193 indicates the speed at which COMP returns to equilibrium after a deviation. A negative sign suggests that COMP will decrease to correct any disequilibrium.

5.5. Interpretation of the Regression Results

From Table 10, the control variables explained 9.4% of the variance in compliance with AML regulations in Ghana. The addition of the independent variables to the control variables in Model 2 increased the variance to 63.4% (∆F = 94.874, p < 0.001), depicting a change in the variance by 54%. Furthermore, when the moderator variables, normative power and an innovative culture, were added to the control variables and the independent variables in Model 3, the variance again increased to 66.3% (∆F = 10.168, p < 0.001), depicting a change in the variance by 2.9%. The interaction terms to the control, independent, and moderator variables in Model 4 also increased the variance to 68.1% (∆F = 5.585, p < 0.05), with a corresponding change in R2 of 6%.

5.5.1. Effects of Control Variables on Compliance with AML Regulation

The study employed three main control variables: educational level, age, and monitoring and supervision. Reading from Model 4, it was found that two of the control factors had both positive and negative significant effects on compliance with AML regulations in Ghana. Specifically, educational level had a positive and significant effect on compliance with AML regulations (b = 0.057, p < 0.05). Additionally, monitoring and supervision (b = −0.042, p < 0.10) had a negative and significant effect on compliance with AML regulation, while the age of a respondent had a negative (b = −0.005, p > 0.10) but insignificant effect on compliance with AML regulations in Ghana.

5.5.2. Effects of Independent Variables on Compliance with AML Regulation

Regarding the independent variables used in the context of this study, which were moral involvement, due diligence, and an effective AML/CFT compliance program, the results obtained from the hierarchical regression show a significant effect for two independent variables on compliance with AML regulations. These include due diligence and moral involvement. Reading from Model 4, the results revealed that moral involvement had a significant and positive effect (b = 0.599, p < 0.01) on compliance with AML regulations in Ghana, confirming hypothesis one. Likewise, due diligence had a positive and significant effect (b = 0.337, p < 0.05) on compliance with AML regulations. This implies that hypothesis two was supported; however, it was found that an effective AML/CFT compliance program had a negative and insignificant effect (b = −0.120, p > 0.10) on compliance with AML regulations. This outcome implies that hypothesis three was not supported. Profitability and size also had a positive and significant effect on compliance with AML regulations, as shown in Model 4 (b = 0.454, p < 0.01 and b = 0.293, p < 0.05).

5.5.3. Effect of Independent Variables on Compliance with AML Regulations Considering the Interaction Roles of an Innovative Culture and Normative Power

Aside from the direct effects of the independent variables on banks’ compliance with AML regulations in Ghana, this study also tested for the moderation role of an innovative culture and normative power on the relationship between the independent variables with the dependent variable. Based on the results, it was found that the interaction of moral involvement and normative power had a significant but negative effect (b = −0.076, p < 0.05) on compliance with AML regulations, thereby failing to support hypothesis four. The interaction effect of due diligence and an innovation culture resulted in a significant but negative effect (b = −0.072, p > 0.10) on compliance with AML regulations; therefore, hypothesis five was not supported. Lastly, it was found that the interaction of an effective AML/CFT program and an innovation culture had a positive and significant effect (b = 0.148, p < 0.01) on compliance with AML regulations in Ghana. Hence, hypothesis six was supported.

6. Discussion

6.1. The Effect of Moral Involvement on Compliance with AML Regulations

This study hypothesised a positive relationship between employee moral involvement and compliance with AML regulations, and this was supported. The results imply that compliance with AML regulations may be achieved when employees of a bank feel a sense of moral obligation to go about their day-to-day activities according to laid-down procedures or standards (Foorthuis and Bos 2011; Markovits 2014). Additionally, the results may imply that compliance with AML regulations can be attained when employees of a bank go about their responsibilities based on personal principles that are morally upright and ethical and serve the bank’s overall interest. Furthermore, the results imply that a sense of psychological attachment among employees and compliance officers in line with the values, objectives, norms, and standards of ethical behaviour contributes favourably to compliance with AML regulations (Affum and Obiri 2020). The findings of this study validate some previous studies.

6.2. The Effect of Due Diligence on Compliance with AML Regulations

It was hypothesised that there would be a positive relationship between customer due diligence and compliance with AML regulations. The outcome of the hypothesis analysis confirmed this relationship as positive and significant. The results can mean that bank staff generally take conscious and reasonable steps to assess the risks associated with a transaction accurately. Given the strict adherence to the stipulated laid-down procedures, bank officials can effectively categorise customers and transactions according to their perceived risks and put in mechanisms to avert such risks (Berntsen and Thompson 2015). Furthermore, the results suggest that banks in Ghana conduct due diligence on their customers and perform a thorough background assessment of their employees to ensure that only employees with a high level of integrity are recruited. This ensures that only employees with the right behaviours and attitudes are recruited into the bank. Additionally, based on the results, it is safe to suggest that banks in Ghana perform comprehensive appraisals of their customers to establish the authenticity of their sources of wealth. These due diligence practices embarked on by banks explain why they contribute positively and significantly to compliance with AML regulations. This finding corroborates some past studies’ results (Levi and Reuter 2006; McLaughlin and Pavelka 2013; Mekpor et al. 2018).

6.3. The Relationship between an Effective AML/CFT Program and Compliance with AML Regulations

It was hypothesised that there would be a positive relationship between an effective AML/CFT program and banks’ compliance with AML regulations; however, the findings revealed a negative and insignificant effect of an effective AML/CFT program on banks’ compliance with AML regulations. This suggests that the outcome of the hypothesis tested does not support the initial prediction of this study. An AML/CFT program is a well-designed and coordinated set of activities to achieve organisational compliance with AML regulations. Concerning the strategic nature of an AML/CFT program, it was expected that it would contribute positively and significantly to compliance with AML regulations; however, the result was negative, contrary to our prediction, and contradicts some previous findings that supported a positive relationship between AML programs and compliance with AML regulations (Schott 2006; Sharman 2008; Yepes 2011).

In light of these findings from the extant literature, it was unexpected that the results did not support the positive association between an effective AML/CFT program and AML regulation compliance. The results were negative because the study tested the various components of an AML program as a single component factor. This confirms that the mere existence of an AML program offers no assurance for the effectiveness of the various components, hence the construct’s failure to influence the achievement of compliance with regulations.

6.4. The Effect of Moral Involvement on Compliance with AML Regulations: The Moderating Role of Normative Power

This study hypothesised that the positive relationship between employee moral involvement and compliance with AML regulations would be enhanced when normative power is high. In other words, this study predicted that the hypothesised initial positive relationship between moral involvement and compliance with AML regulations would be more potent and, for that matter, positive if there was a high level of normative power in a bank; however, based on the results, it was found that normative power somewhat negatively moderated the relationship. The results contradict the study by Foorthuis and Bos (2011), who viewed normative power as an essential catalyst that enhances moral involvement. This contradiction could be explained from two logical angles: In the first place, the negative moderation effect of normative power might be explained by the non-demonstration or exhibition of normative ways of leading. In other words, the leaders of the various banks interviewed are not setting the right examples for their subordinates to follow. This is not to suggest that leaders of the banks surveyed do not demonstrate responsible leadership behaviours, but, rather, it may be the case that they do not demonstrate such behaviours consistently. Secondly, managers might exhibit exemplary behaviours at other times, but the leaders might not influence their subordinates to replicate their behaviours.

6.5. The Effect of Internal Bank Factors (i.e., Customer Due Diligence and an Effective AML Program) on Compliance with AML Regulations: The Moderating Role of an Innovation Culture

This study did not support the hypothesis that a positive relationship between customer due diligence and compliance with AML regulations will be strengthened by an innovation culture. The results found that an innovation culture weakened the relationship, thus significantly negatively influencing the relationship between customer due diligence and compliance with AML regulations. Given the evolving nature of most bank clients, it was anticipated that conducting a due diligence assessment by merely ‘checking boxes’ or adhering strictly to established procedures might not provide a thorough understanding of a customer’s background. Consequently, the banking environment tends to be less innovative in generating unconventional ideas, particularly in operations and risk management. This might explain why an innovative culture negatively moderated the relationship between due diligence and compliance with AML regulations.

Lastly, it was hypothesised that an innovation culture would strengthen the positive relationship between an effective AML/CFT program and compliance with AML regulations. Consequently, the outcome of the hypothesis testing provided support for this prediction; thus, the moderation effect of an innovation culture on the relationship between an effective AML/CFT program and compliance with AML regulations was positive and significant. The results suggest that the development and implementation of AML/CFT programs allow for iterative changes to a program, considering the global trends and emerging dynamics in the market. The findings of this study validate the work by Barr et al. (2018), who found a significant positive moderation effect of an innovation culture on the relationship between an AML/CFT program and compliance with AML regulations.

6.6. Contribution to Knowledge

This research makes a significant contribution to the understanding of antecedents of compliance with anti-money laundering regulations in the Ghanaian banking sector and the impact of compliance on organizational outcomes. AML regulations are relatively new in Ghana, coming into effect in 2006 (Bank of Ghana 2006), and were implemented at the insistence of the Financial Action Task Force as well as other international organizations concerned with money laundering and terrorist financing. Since then, there has been little research conducted to understand the impact of these regulations on banks and how the latter can be encouraged to abide by them. This study identifies the importance of compliance with regulations and is one of the first to explore the antecedents of compliance with AML regulations in the banking industry and the impact of compliance on organizational outcomes using selected independent variables. Compliance with AML regulations is essential for the success of the regulations’ objectives and the management of illegal finance, which can cause detrimental effects globally (Pol 2020; Mugarura 2020; Pontes et al. 2022); however, there is much evidence to suggest that organizations of all types are generally reluctant to comply with regulations until forced to do so (Naheem 2020; Zavoli and King 2021; Roberta 2024). This is much the same in the financial industry, and has been the case with AML regulations in Ghana (Esoimeme 2020; Torku and Laryea 2021). Now that the detrimental effects of non-compliance with these regulations have been identified, it is essential to the success of regulation objectives to encourage all regulated entities to comply with said regulations (Rose 2021; Elaiyarajah and Hagevik 2022).

7. Conclusions

It was discovered that Ghanaian banks abide by every provision set forth by the Anti-Money Laundering Act. Notably, this study showed that while the Central Bank superficially highlights public compliance to boost Ghana’s global financial reputation, it may not actively enforce these requirements. Furthermore, employees within Ghanaian banks demonstrate awareness of AML regulations, and there is a favourable relationship between their compliance, due diligence, and moral involvement; however, contrary to expectations, effective AML/CFT programs show no significant impact on banks’ adherence to these regulations. Remarkably, the association between moral engagement, an innovative culture, and AML compliance is weakened by normative power and an innovation culture acting as negative moderators.

It is suggested that regulatory bodies mandate compliance to bolster the financial sector’s image, yet banks bear the burden of AML requirements. They must invest in employee training and protocol implementation, leading to diminished profits as less regulated sectors, like small-scale gold mining, become less viable. Failure to meet regulatory standards leads to varied responses, including increased enforcement actions and interpretive inertia by regulatory bodies. Additionally, we acknowledge and recommend the importance of considering other African countries for future studies.

The implications of the strategy for Ghanaian banks’ adherence to anti-money laundering (AML) legislation highlight the significance of regulatory supervision and enforcement practices. The Central Bank may not actively enforce these criteria, regardless of the its apparent compliance. This underscores the need for more robust regulatory measures and monitoring procedures. Additionally, the fact that staff compliance and awareness of AML requirements are positively correlated highlights how key it is for financial institutions to foster a culture of regulatory adherence. To ensure sustained compliance, policymakers should give priority to programs that improve employees’ comprehension of AML/CFT procedures and encourage moral involvement.

Furthermore, the surprising finding that an efficient AML/CFT program has no significant effect on a bank’s compliance with legislation points to the necessity for the re-evaluation and possible improvement of existing programs. It is recommended that policymakers assess the effectiveness of existing AML/CFT activities and contemplate the adoption of novel measures to augment their influence on compliance results. The fact that normative power and an innovation culture have been identified as negative moderators further emphasises how critical it is to address organizational dynamics that might thwart efforts to comply with regulations. Banks and regulatory agencies should work together to reduce obstacles to compliance, including organizational resistance to innovation and change.

Overall, these policy implications underscore the importance of proactive regulatory measures, targeted support for banks, and strategic reforms to enhance AML compliance as well as safeguard Ghana’s financial integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.N.H. and J.O.; methodology, B.N.H. and S.E.S.; software, S.E.S.; validation, J.O. and S.E.S.; formal analysis, B.N.H. and S.E.S.; investigation, B.N.H.; resources, B.N.H.; data curation, B.N.H. and S.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.N.H.; writing—review and editing, J.O. and S.E.S.; visualization, B.N.H.; supervision, J.O. and S.E.S.; project administration, B.N.H. and J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Affum, Frederick, and Kwadwo Ayeh Obiri. 2020. Ghana’s banking sector cleanup: Its repercussions on customer attitudes towards banking. Journal of Management Marketing and Logistics 7: 234–48. [Google Scholar]

- AFI Special Report. 2019. KYC Innovations, Financial Inclusion and Integrity in Selected AFI Member Countries. Available online: https://www.afi-global.org/publications/kyc-innovations-financial-inclusion-and-integrity-in-selected-afi-member-countries/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Agoba, Abel M., Yakubu A. Sare, Ebenezer B. Anarfo, and Christian Tsekpoe. 2023. The push for financial inclusion in Africa: Should central banks be wary of political institutional quality and literacy rates? Politics & Policy 51: 114–36. [Google Scholar]

- Agyenim-Boateng, Cletus, Francis Aboagye-Otchere, and Alice A. Aboagye. 2020. Saints, demons, wizards, pagans, and prophets in the collapse of banks in Ghana. African Journal of Management Research 27: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiauzu, Ndidi. 2022. Assessing the Effectiveness of International Anti-Money Laundering Measures; A Study of Commercial Banks in Nigeria. Available online: https://www.surrey.ac.uk (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Akartuna, Eray A., Shane D. Johnson, and Amy Thornton. 2022. Preventing the money laundering and terrorist financing risks of emerging technologies: An international policy Delphi study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 179: 121632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, Jay S. 2021. Organised crime as financial crime: The nature of organised crime as reflected in prosecutions and research. Victims and Offenders 16: 431–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, Ayodeji, and Mahmood Bagheri. 2012. The impact of money laundering on economic and financial stability and on political development in developing countries: The case of Nigeria. Journal of Money Laundering Control 15: 442–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenu-Tekaa, Kennedy S. 2022. Financial sector regulatory and supervisory framework in Ghana-the pre and post 2017 banking crisis. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management 10: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, Samuel, Anthony B. Tetteh, Patience Armah, and Eric O. Dankwah. 2023. Anti-money laundering measures and financial sector development: Empirical evidence from Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance 11: 2209957. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Ghana. 2006. National Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism and Proliferation (AML/CFT&P) Policy (2019–2022). Available online: https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NATIONAL-POLICY-AML-CFT-POLICY-AND-ACTION-PLAN.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Barnett-Quaicoo, Patricia. 2021. Minimising Bank Failures in Ghana Through Effective Regulatory Compliance Monitoring. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, Michael, Gifford Karen, and Klein Aaron. 2018. Enhancing Anti-Money Laundering and Financial Access: Can New Technology Achieve Both? Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/es_20180413_fintech_access.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Basaran-Brooks, Bahriye. 2022. Money laundering and financial stability: Does adverse publicity matter? Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 30: 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawole, Justice N., and Zechariah Langnel. 2023. Corruption-induced inhibitions to business: What business leaders have to say in Ghana. Journal of African Business 24: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Oluwabusayo A., Adebola Folorunso, Jane Onwuchekwa, and Oluomachi E. Ejiofor. 2023. A Comprehensive Framework for Strengthening USA Financial Cybersecurity: Integrating Machine Learning and AI in Fraud Detection Systems. European Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology 11: 62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen, Erik S., and John Thompson. 2015. Guide to Starting Your Hedge Fund. New York: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Timothy A. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cantah, William G., Kwabena N. Darfor, Jacob Nunoo, Benedict Afful, Jr., and Emmanuel A. Wiafe. 2023. Bank Competition and Financial Sector Stability in Ghana. Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions. In Financial Sector Development in Ghana. Edited by James Atta Peprah, Evelyn Derera, Harold Ngalawa and Thankom Arun. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 133–54. [Google Scholar]

- CGAP. 2014. Financial Inclusion and Development: Recent Impact Evidence. Available online: http://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/FocusNote-Financial-Inclusion-and-Development-April-2014.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Chatain, Pierre-Laurent, John Mcdowell, Cedric Mousset, Paul A. Schott, and Emile V. D. Willebois. 2009. Preventing Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing a Practical Guide for Bank Supervisors. Washington, DC: World Bank Publication, The World Bank Group, number 2638. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, Md Maruf H., and Mohammed Quaddus. 2017. Supply chain resilience: Conceptualisation and scale development using dynamic capability theory. International Journal of Production Economics 188: 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Dartey, Jesse K., Johnson Okeniyi, Sunday E. Samuel, Eunice Peregrino-Dartey, and Collins Cobblah. 2024. Debt Financing and Growth of Ghanaian Family-Owned Businesses: The Dual Role of Family Values. Africa Journal of Management 10: 229–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Foglie, Andrea, Elias Boukrami, Gianfranco Vento, and Ida C. Panetta. 2023. The regulators’ dilemma and the global banking regulation: The case of the dual financial systems. Journal of Banking Regulation 24: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, C. 2016. Compliance Theory of Organisations. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Edited by Ali Farazmand. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Eilert, Meike, and Abigail Nappier Cherup. 2020. The activist company: Examining a company’s pursuit of societal change through corporate activism using an institutional theoretical lens. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 39: 461–76. [Google Scholar]

- Elaiyarajah, Kaviya, and Elisabeth O. Hagevik. 2022. Compliance with the Anti-Money Laundering Act in the auditing and accounting industry. Norwegian Business School. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11250/3038698 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- ElYacoubi, Dina. 2020. Challenges in customer due diligence for banks in the UAE. Journal of Money Laundering Control 23: 527–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esoimeme, Ehi E. 2020. Balancing anti-money laundering measures and financial inclusion: The example of the United Kingdom and Nigeria. Journal of Money Laundering Control 23: 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, Amitai. 1975. A comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations: On Power, Involvement, and Their Correlates. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni, Amitai. 1997. Modern Organisations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ezugwu, Christian I., and Sunday E. Samuel. 2011. Degree of Compliance with Disclosure Requirements in the Financial Statements: A Study of Selected Quoted Companies in Nigeria. Journal of Policy and Development Studies 5: 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- FATF. 2023. International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation, FATF, Paris, France. Available online: www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/Fatf-recommendations.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). 2017. New Technologies and Anti-Money Laundering Compliance. Available online: https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/research/new-technologies-and-anti-money-laundering-compliance-report (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Fligstein, Neil. 2021. Organizations: Theoretical Debates and the Scope of Organizational Theory. In Handbook of Classical Sociological Theory. Edited by Seth Abrutyn and Omar Lizardo. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Cham: Springer, pp. 487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Foorthuis, Ralph, and Rik Bos. 2011. A Framework for Organizational Compliance Management Tactics. In Advanced Information Systems Engineering Workshops. CAiSE 2011. Edited by Camille Salinesi and Oscar Pastor. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springe, vol. 83, pp. 259–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, Jack R., Norman Wallen, and Helen Hyun. 2023. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 11th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Gaviyau, William, and Athenia B. Sibindi. 2023. Global Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Terrorism Financing Regulatory Framework: A Critique. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16: 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, Paul Michael. 2022. Reexamining the anti-money-laundering framework: A legal critique and new approach to combating money laundering. Journal of Financial Crime 30: 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginting, Jamin, and Adessya T. Chairunissa. 2021. Adopting the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations in Realizing Beneficial Owners Transparency in Limited Companies to Prevent Money Laundering Criminal Acts in Indonesia. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 24: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, and Barry Babin. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed. Hoboken: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, Tim, and Amelia Hawbaker. 2021. The case for an inhabited institutionalism in organizational research: Interaction, coupling, and change reconsidered. Theory and Society 50: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Kung-Cheng, Jason Z. Ma, Lu Yang, and Lisi Shi. 2019. Do anticorruption efforts affect banking system stability? The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development 28: 277–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Nadir, Salman M. Sheikh, and Ijaz H. Shah. 2022. Exploring the role of corruption and money laundering (ML) on bank’s loan portfolio quality: A cross-country investigation. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 30: 265–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyle, Adrienne E. 2006. Compliance theory. In Encyclopedia of Educational Leadership and Administration. Edited by Fenwick English. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Reference, pp. 185–86. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). 2019. Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) and Countering Financing of Terrorism (CFT) Risk Management in Emerging Market Banks: Good Practice Note. Washington, DC: IFC, PA Avenue. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, Yusarina M., Zuraidah M. Sanusi, Mohd N. Haniff, and Paul A. Barnes. 2015. Money Laundering Risk: From the Bankers’ and Regulators Perspectives. Procedia Economics and Finance 28: 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Mohammad, Sharmin A. Eva, and Mohammad Z. Hossain. 2017. Predicate Offences of Money Laundering and Anti Money Laundering Practices in Bangladesh Among South Asian Countries. Studies in Business and Economics 12: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issah, Mohammed, Samuel Antwi, Solomon K. Antwi, and Patience Amarh. 2022. Anti-money laundering regulations and banking sector stability in Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Aabha, and Ajay Shah. 2020. Anti-money laundering awareness and acceptance among the bank customers of Nepal. Quest Journal of Management and Social Science 2: 337–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, Dev. 2013. Illicit Financial Flows and the Problem of Net Resource Transfers from Africa: 1980–2009. Global Financial Integrity/International Monetary Fund, May 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Paul-O., and Laurent Weill. 2018. Bank Profitability and Economic Growth. BOFIT Discussion Paper No. 15/2018. Helsinki: Bank of Finland Publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klutse, Senanu K., and Gábor Kiss. 2022. A Re-Examination of the Remedial Action Adopted by the Central Bank during Banking Crisis–The Case of Ghana. Strategica, 385–401. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stanescu-Dan-Florin/publication/357506527_Applying_Technology_Acceptance_Model_TAM_to_Explore_Users’_Behavioral_Intention_to_Adopt_Wearables_Technologies/links/61d0e08fb8305f7c4b191b7b/Applying-Technology-Acceptance-Model-TAM-to-Explore-Users-Behavioral-Intention-to-Adopt-Wearables-Technologies.pdf#page=386 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Korauš, Antonin, Eva Jančíková, Miroslav Gombár, Lucia Kurilovská, and Filip Černák. 2024. Ensuring Financial System Sustainability: Combating Hybrid Threats through Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Measures. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korejo, Muhammad S., Ramalinggam Rajamanickam, and Muhamad H. Said. 2021. The concept of money laundering: A quest for legal definition. Journal of Money Laundering Control 24: 725–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, Michael H., Christopher J. Nachtsheim, John Neter, and William Li. 2005. Applied Linear Statistical Models, 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard-Barton, Dorothy. 1992. Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal 13: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Michael, and Melvin Soudijn. 2020. Understanding the laundering of organised crime money. Crime and Justice 49: 579–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Michael, and Peter Reuter. 2006. Money laundering. Crime and Justice 34: 289–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Michael, Terence Halliday, and Peter Reuter. 2014. Global Surveillance of Dirty Money: Assessing Assessments of Regimes to Control Money-Laundering and Combat the Financing of Terrorism. Illinois: Centre on Law and Globalization, American Bar Foundation and University of Illinois College of Law. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Kaodui, Yusheng Kong, Sampson A. Atuahene, Geoffrey Bentum-Micah, and Michael K. Agyapong. 2020. Corporate governance and banking stability: The Case of Universal Banks in Ghana. International Journal of Economics & Business Administration 8: 325–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lokanan, Mark E. 2022. Predicting Money Laundering Using Machine Learning and Artificial Neural Networks Algorithms in Banks. Journal of Applied Security Research 19: 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Nicholas, Karin V. Wingerde, and Liz Campbell. 2018. Organizing the monies of corporate financial crimes via organisational structures: Ostensible legitimacy, effective anonymity, and Third-Party facilitation. Administrative Sciences 8: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunenburg, Fred C. 2012. Compliance theory and organisational effectiveness. International Journal of Scholarly Academic Intellectual Diversity 14: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, Timothy F. 2003. Regulation, Compliance and the Firm. Temple Law Review 76: 451. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Matthew, Gabriel T. W. Wong, and Nada Jevtovic. 2021. Investigating the relationships between FATF recommendation compliance, regulatory affiliations and the Basel Anti-Money Laundering Index. Security Journal 34: 589–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Yannis. 2014. Normative commitment and loyal boosterism: Does job satisfaction mediate this relationship? MIBES Transactions 5: 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Markovska, Anna, and Nya Adams. 2015. Political corruption and money laundering: Lessons from Nigeria. Journal of Money Laundering Control 18: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Roderick P., and Moon-Ho Ringo. 2002. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods 7: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]