Abstract

The increasing wave of protectionism in various corners of the world with the use of seemingly attractive but economically misleading slogans (shortening supply chains, onshoring, reshoring, nearshoring, friend-shoring, reindustrialization, and ending/correcting ‘hyperglobalization’, etc.) creates a serious challenge to the global trading system and global economic development. Trade and financial transactions have also become victims of the increasing number of geopolitical conflicts and tensions, both ‘hot’ and ‘cold’. Before it becomes too late, i.e., before the current trade tensions go too far and create the hardly reversible spiral of trade and financial wars, retaliations, etc., it is desirable to reflect on what can be lost due to protectionism. This essay analyzes four areas that have benefited from global economic integration since the 1980s (economic growth, poverty eradication, reduction in global economic inequalities, and disinflation) and may suffer from its reversal. It also discusses potential remedies that may help stop a protectionist drift.

1. Introduction

The rapid global economic integration period, globalization1, started in the 1980s and gained momentum in the 1990s and early and mid-2000s. It stagnated after the global financial crisis (GFC) and never regained its previous dynamics. Worse, since the end of the 2010s, the risk of its reversal has intensified. The United States (US)–China trade conflict and geopolitical rivalry, the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, and protectionist sentiments worldwide have stayed behind this trend change. The notions of deglobalization, decoupling, economic fragmentation, and even Cold War II (Robinson and Ferguson 2023; Gopinath 2023) have been frequently floated in political and economic debate.

Before it becomes too late, i.e., before the current trade tensions go too far and create the hardly reversible spiral of trade and financial wars, retaliations, etc., it is desirable to reflect on what can be lost due to the fragmentation of the world economy. This essay serves this purpose. Its primary aim is to focus on potential global economic and social losses, especially in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), due to protectionism and deglobalization. While individual negative aspects of global economic fragmentation are frequently discussed in the literature, they are usually discussed from the perspective of individual countries or bilateral relations and serve the purpose of the current policy debate2. The intended value added of this paper is to summarize arguments in defense of continuous worldwide economic integration from the perspective of global growth dynamics, poverty reduction, mitigating global income inequality, and price stability.

This essay is based on a literature review and empirical research.

It starts with a historical overview of two waves of globalization—between 1870 and 1914 and a century later. It is followed by an analysis of the factors that determined the rapid globalization between the 1980s and 2000s (Section 2) and the socio-economic gains attributed to globalization (Section 3). Section 4 is devoted to the increasing protectionist pressures at the end of the 2010s and early 2020s and the expected negative consequences of deglobalization/fragmentation of the world economy. In Section 5, we discuss policy remedies that can arrest protectionist trends. Section 6 contains a summary and conclusions.

2. A Brief History of Globalization: The First and Second Wave

The globalization episode of the late 20th/early 21st century was not the first in contemporary economic history3. A century earlier, between 1870 and 1914, there was another period of globalization (see, e.g., Bordo et al. 1999; O’Rourke and Williamson 2000; Morys et al. 2008; Daudin et al. 2010) underpinned by the first and second industrial revolutions, relatively liberal trade policies, the gold standard and full convertibility of major currencies, and, last but not least, relative peace between major political and economic powers.

A brief look at the history of the first globalization wave helps in understanding the origins and dynamics of the second wave, and the factors that may cause its demise.

Industrial revolutions facilitated mass production, in which the economy of scale and market access (beyond national borders) played an increasing role. New technical innovations4 (steam power and railways, followed by electricity and combustion engines) made transporting goods and people cheaper and safer. They also contributed to the development of new means of communication (the telegraph then the telephone), which made trade and financial transactions more accessible and less expensive.

The gold standard and currency convertibility reduced transaction costs and exchange rate risk. The gold standard also eliminated the risk of inflation. On the contrary, there were periods of price decline (Meltzer and Robinson 1989) due to a limited supply of gold, productivity gains, and business cycle fluctuations.

Finally, the absence of open conflicts between major powers5 reduced security risks and the risk of a sudden regime change in trade and financial flows. Hence, it was unsurprising that WWI brutally interrupted the first wave of globalization.

The interwar period of the 1920s and 1930s was characterized by increasing trade protectionism and capital movement restrictions. The collapse of four empires in Europe and its periphery (Austro-Hungary, Germany, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire) caused the appearance of several new states with new currencies and customs borders. Several European countries had problems rebuilding their fiscal and monetary equilibria in the immediate post-WWI period and returning to the convertibility of their currencies. Austria, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Soviet Russia experienced hyperinflations (Solimano 2020, pp. 25–60). The Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), created in December 1922 by the Bolshevik regime on the territory of the former Russian empire, introduced a centralized system of command economy at the end of the 1920s based on a monopoly of state ownership and a far-reaching autarky (Leonard 2023). The US chose the isolationist direction of its foreign and economic policy (Dadush 2023).

The Great Depression, which started in the US in September 1929 and hit the entire world economy for the first half of the 1930s, triggered a new wave of beggar-thy-neighbor policies such as competitive devaluations or rising trade barriers6. WWII further devastated the global economy and global trade. As a result, the share of global exports of goods in the world’s GDP declined from 14.0% in 1913 to 4.2% in 1945 (Fouquin and Hugot 2016, Figure 1).

The post-WWII global economic and financial architecture with the triad of international institutions (the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and International Trade Organization) was to rebuild global economic integration and overcome interwar protectionism. However, reintegration proceeded slowly and with many zigzags. The failure of the US Congress to ratify the Havana Charter of the International Trade Organization did not allow this organization to take off7. For almost half a century, the world trade system was regulated by a looser General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its secretariat in Geneva. Only the Marrakesh Agreement in April 1994, which finalized the eighth round of multilateral trade negotiations (MTNs), called the Uruguay Round, allowed the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) with a broad trade policy agenda. In the meantime, trade liberalization progressed incrementally by covering new policy areas and bringing more countries via subsequent rounds of MTNs (see Table 1).

Table 1.

GATT trade rounds, 1947–1994.

Initially, the GATT system involved predominantly advanced economies (AEs). Due to the decolonization process, emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) joined the GATT in more significant numbers from the 1960s. Most former communist economies in Europe and Asia joined the GATT/WTO in the 1990s, 2000s, and early 2010s when they advanced their transitions to a market system.

In other policy areas, the progress in opening economies, both advanced (AEs) and emerging market and developing ones (EMDEs), was also slow. Most of them had inconvertible or only partly convertible currencies. Although the Bretton Woods system of fixed but adjustable pegs decreased transaction costs, it proved ultimately unstable and collapsed in 1971 (Garten 2021). As a result, the 1970s and 1980s were marked by trade tensions (for example, between the US and Japan) originating from exchange rate disputes. It was also a period of macroeconomic instability in many corners of the world.

On top of that, economic policies and systems, with a more significant role of state ownership and government regulation, chosen by several AEs, did not help economic openness. The situation was even worse in EMDEs. Many adopted the statist and autarkic development models, with high protectionist barriers and import-substitution industrialization as a reaction to former colonial links. Some EMDEs tried to copy the economic model of communist countries, usually with disastrous socio-economic consequences.

Since the early 1980s, as a reaction to earlier policy failures, several AEs and EMDEs have entered the path of market-oriented reforms, including more significant trade and financial openness. It allowed the acceleration of MTNs, especially the Uruguay Round, and progress in global economic integration. Far-reaching economic reforms in large EMDEs such as China and India, the former Soviet Union (Dabrowski 2023), and Central and Eastern Europe boosted global trade, investment, and financial flows.

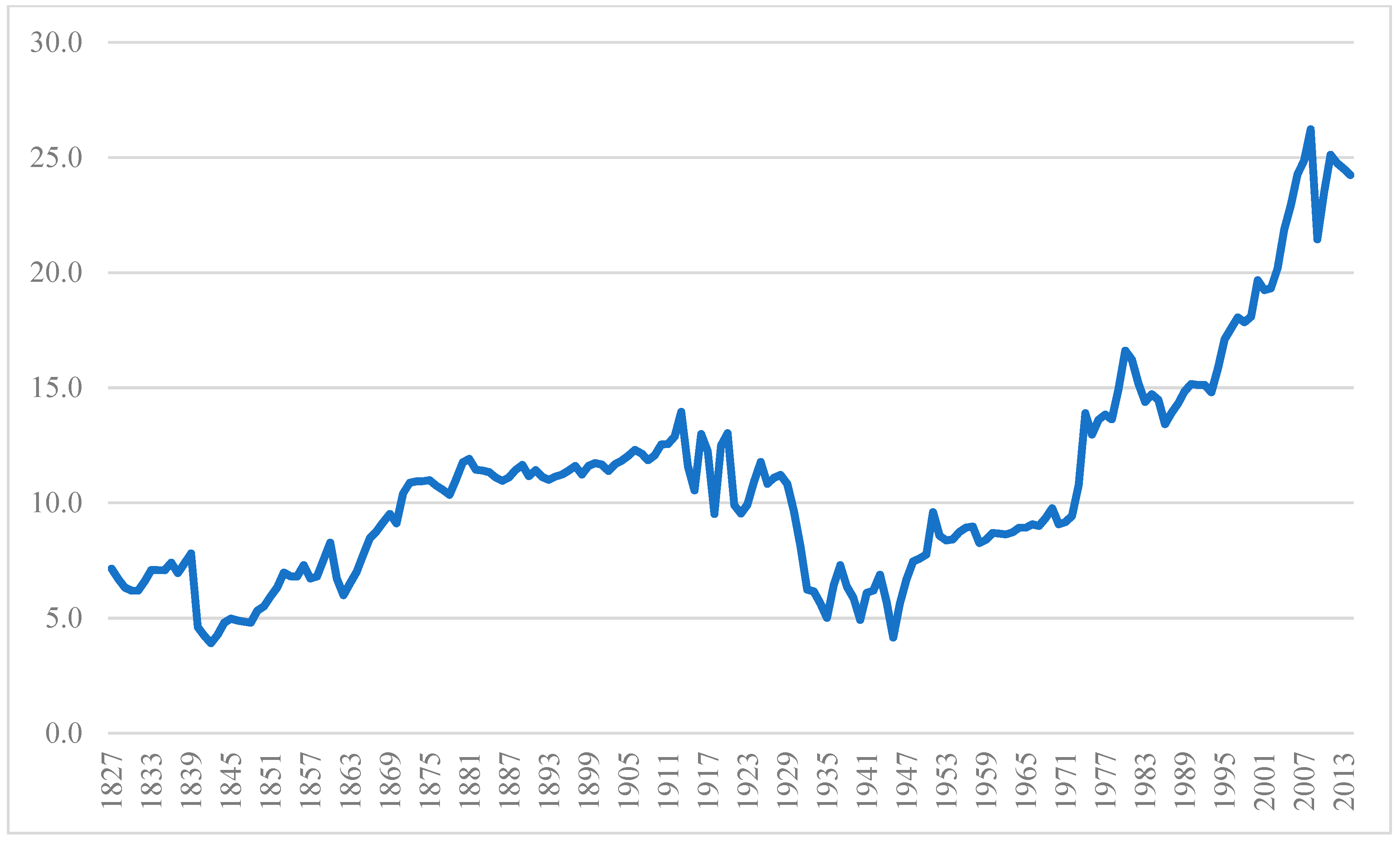

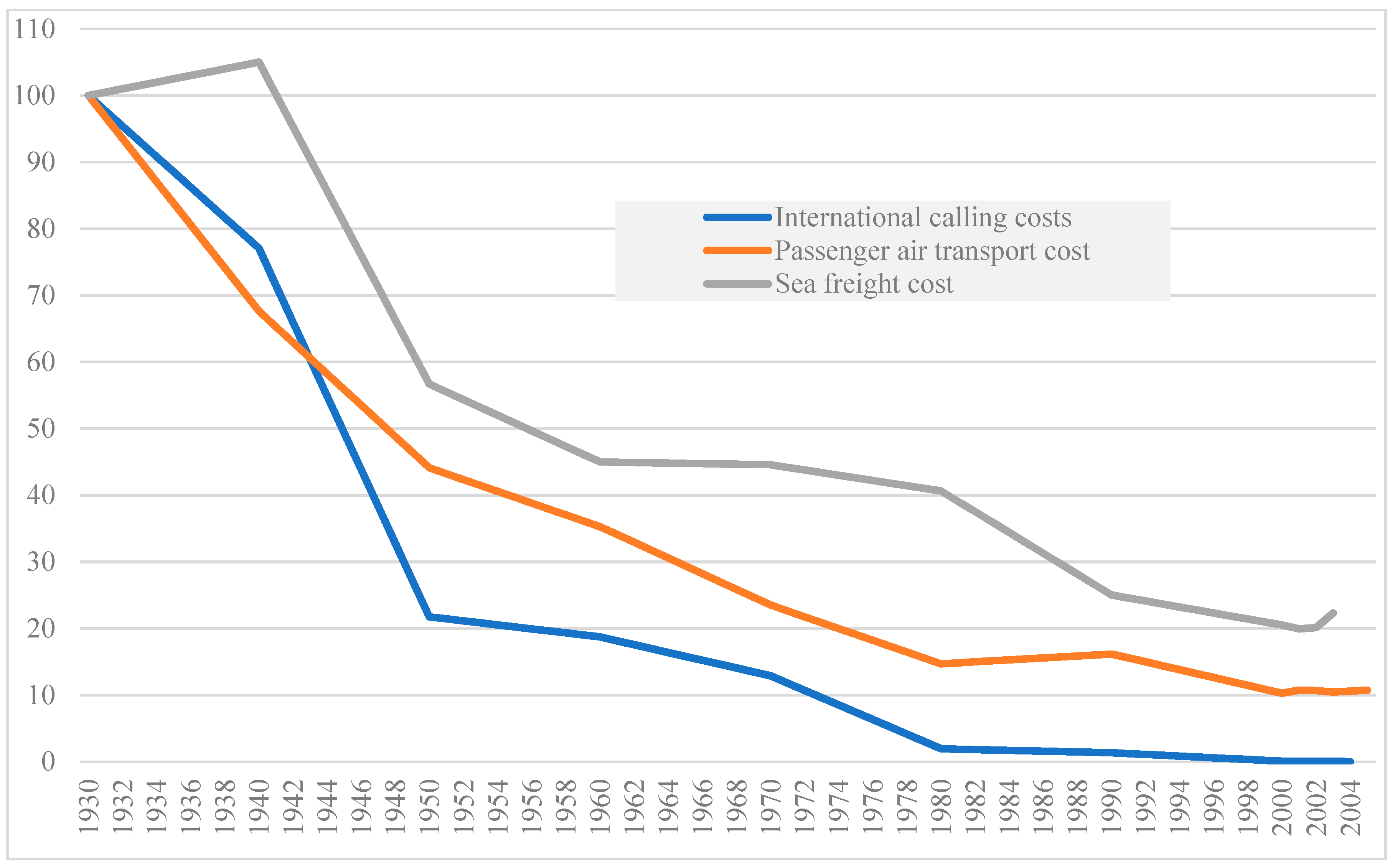

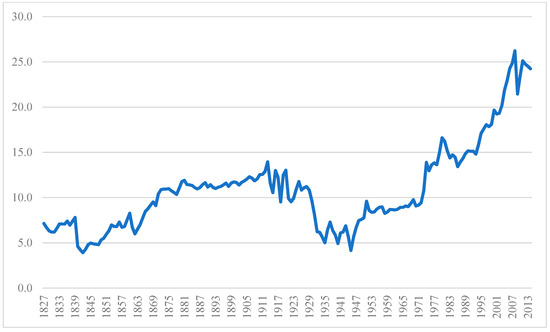

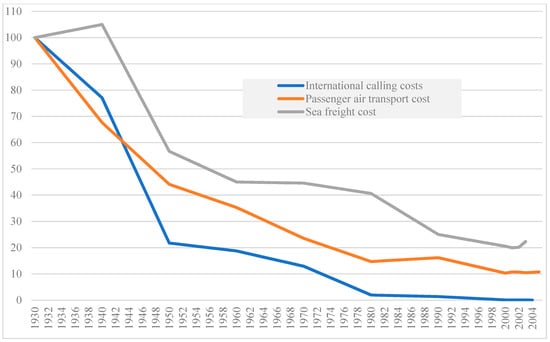

As a result of the above policy changes, global trade in goods and services to the world’s GDP ratio grew rapidly between 1980 and 2008 (Figure 1). This expansion was driven, among others, by the subsequent rounds of MTNs (in particular, the Uruguay round), the creation of the WTO and China’s accession to this organization in 2001, and liberalization of current account transactions and other market-oriented reforms in several EMDEs. Innovations in transport, communication, logistics, energy, miniaturization of various devices, etc., also decreased trade costs (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The world economy: merchandise exports as % of GDP. Source: https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization (accessed on 18 August 2024) after Fouquin and Hugot (2016).

Figure 2.

Real transportation and communication costs, 1930 = 100, 1930–2005. Notes: Sea freight costs correspond to average international freight charges per ton. Passenger air transport costs correspond to average airline revenue per passenger mile until 2000 and spliced to US import air passenger fares afterwards. International calling costs correspond to the cost of a three-minute call from New York to London. Source: https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization (accessed on 18 August 2024) after Huwart and Verdier (2013).

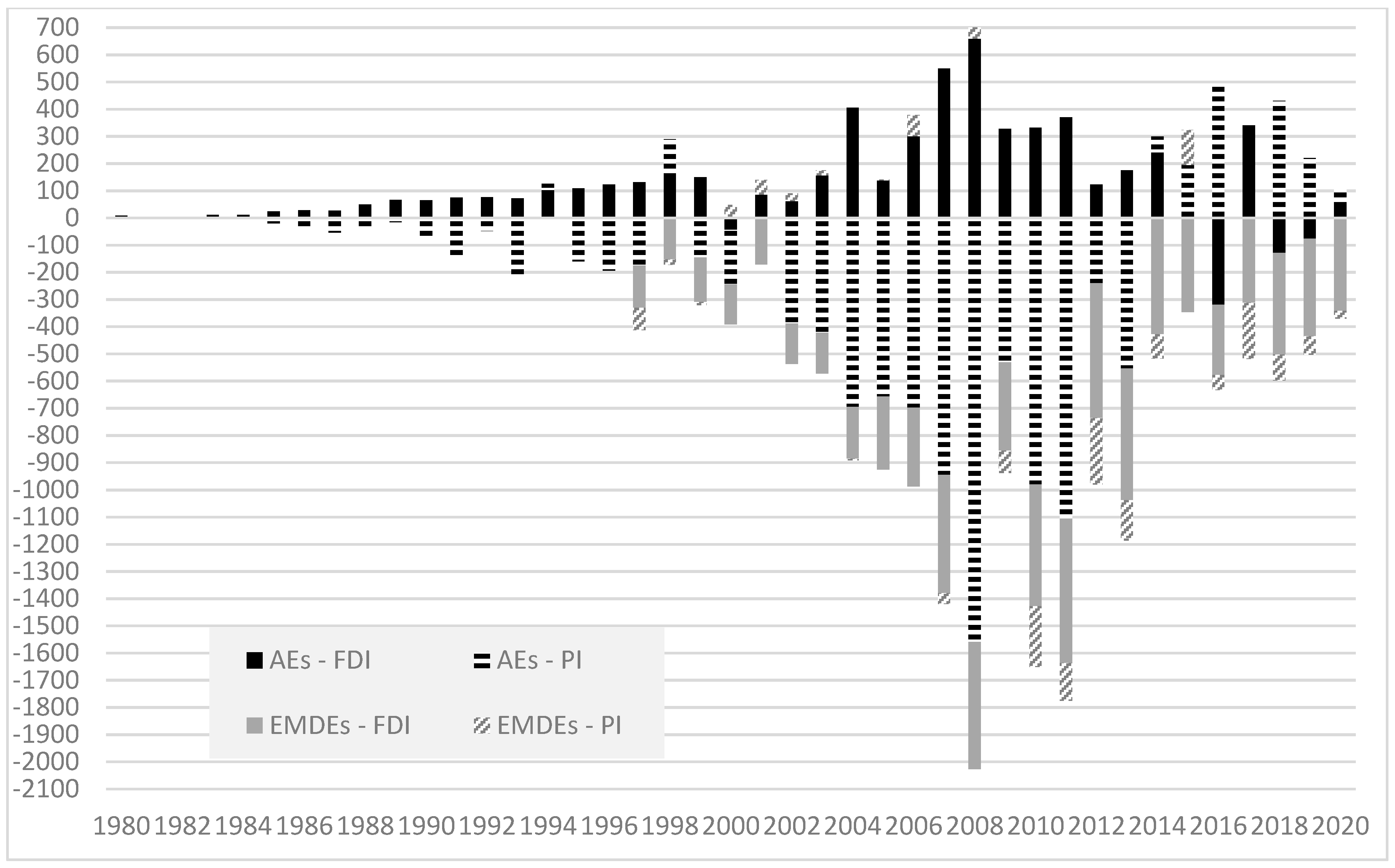

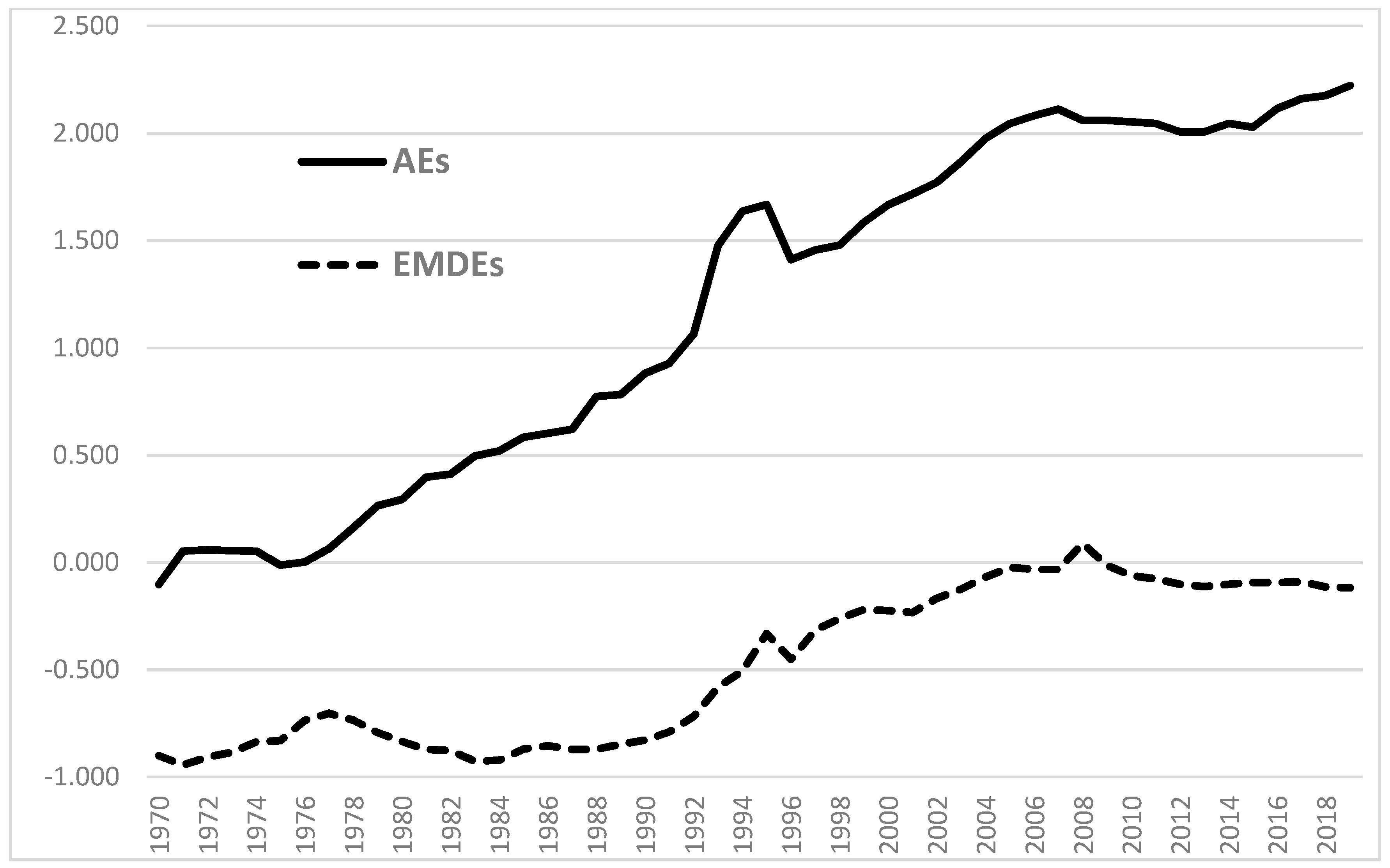

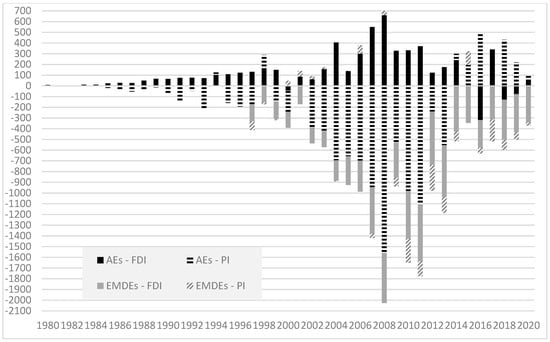

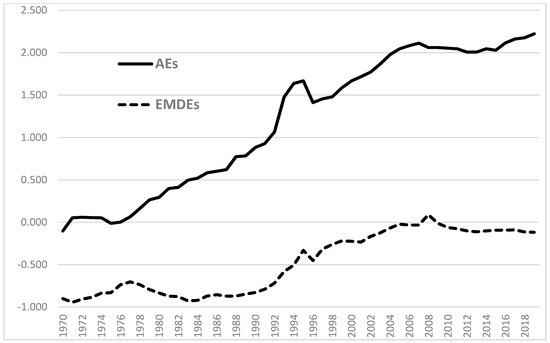

A similar trend concerned foreign direct investment (FDI) and other financial flows (Figure 3). It was driven by the liberalization of capital accounts (Figure 4), financial sector reforms, the privatization and deregulation of banks, non-banking financial institutions, and non-financial corporations with the participation of foreign capital, legal reforms, concluding in bilateral and multilateral investment-protection treaties, progress in information and communication technologies (ICTs) and their application in financial transactions, and financial innovations (facilitated, in turn, by a combination of legal innovations and new ICT tools). All these factors have eliminated institutional, legal, and technical barriers to unrestricted capital movement, especially private financial flows, across the globe, substantially reduced transaction costs, and helped to integrate national financial markets into a single global market.

Figure 3.

Cross-border net direct and portfolio investment flows in USD billion, world total, 1980–2020, BoP statistics. Note: Positive value means net capital outflow, and negative value means net capital inflow. FDI—foreign direct investment, PI—portfolio investment. Source: World Economic Outlook database, April 2021.

Figure 4.

The Chinn–Ito Capital Account Openness Index (KAOPEN), 1970–2018. Notes: The Chinn–Ito Capital Account Openness Index is based on the information from the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER). The current and capital account control degree is normalized within the scale of −1.92 (minimum openness) and 2.33 (maximum openness). Data in Figure 4 represent simple averages of indexes of respective groups of countries. The entire sample amounts to 182 countries. Source: Chinn and Ito (2006); Ito and Chinn (2020); http://web.pdx.edu/~ito/Chinn-Ito_website.htm (accessed on 18 August 2024); and author’s calculation.

The liberalization of capital accounts started in the 1980s in AEs and a decade later in EMDEs (Figure 4). Substantial capital flows began with a decade-long time lag—in the 1990s in AEs and the 2000s in EMDEs8 (Figure 3). The culmination of nominal global flows came in the 2000s. Smaller but still substantial capital flows characterized the 2010s. This resulted from disruption in financial intermediation, recession (especially in AEs), and higher uncertainty caused by the GFC. In addition, the new post-crisis macro- and micro-prudential regulations increased the costs of financial intermediation and investment financing (Dabrowski 2021).

Figure 3 also shows changes in the direction of capital flows. EMDEs were net direct investment recipients during the analyzed period, while AEs were net exporters of this investment in most recorded years. Net portfolio flows seemed to play a less significant role in EMDEs, while they were more critical in AEs. Interestingly, these flows changed direction: since 2014, AEs have become a net exporter of portfolio investment, perhaps as a result of record-low interest rates in most AEs.

There have been significant differences between the two waves of globalization. The depth of the first wave was smaller than the second one. The share of exports of goods to GDP in 1913 (the peak year of the first wave) was approximately half of that in 2008 (the peak year of the second wave). In the case of financial flows, the discrepancy was even more significant (Obstfeld and Taylor 2004, p. 55). The following factors can explain the difference:

- (i)

- Less developed technical infrastructure and higher transportation and communication costs during the first wave (Figure 2). It was essential for financial transactions, where the telegraph was the only means of rapid information transmission for conducting financial transactions and financial market arbitrage at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result, the specter of financial market products traded internationally was smaller compared to the contemporary era.

- (ii)

- Less liberal trade regimes during the first wave: import tariffs were, on average, higher before WWI than in the 2000s and 2010s (Estevadeordal 1997). In particular, this was the case in the US, Russia, Argentina, Canada, Portugal, Spain, Norway, and Finland. Tariffs were lower in the United Kingdom, France, and Switzerland and close to zero in the Netherlands. There were also intra-imperial preferential trade regimes (in the British and French empires). On the other hand, non-tariff barriers, such as sanitary, phytosanitary, and technical standards, played a more limited role.

- (iii)

- Geographical coverage: pre-WWI globalization was limited to Western Europe and the US. Most of today’s EMDEs remained in colonial dependence, and they benefited from economic integration only marginally and often in a distorted form.

3. Gains from Globalization 1980–2020

To illustrate the economic and social benefits of global economic integration for the world economy since the 1980s, we have chosen four areas: global economic growth, poverty eradication, global income inequalities, and disinflation. Progress in these areas has a crucial importance for socio-economic development, especially in EMDEs.

3.1. Global Economic Growth

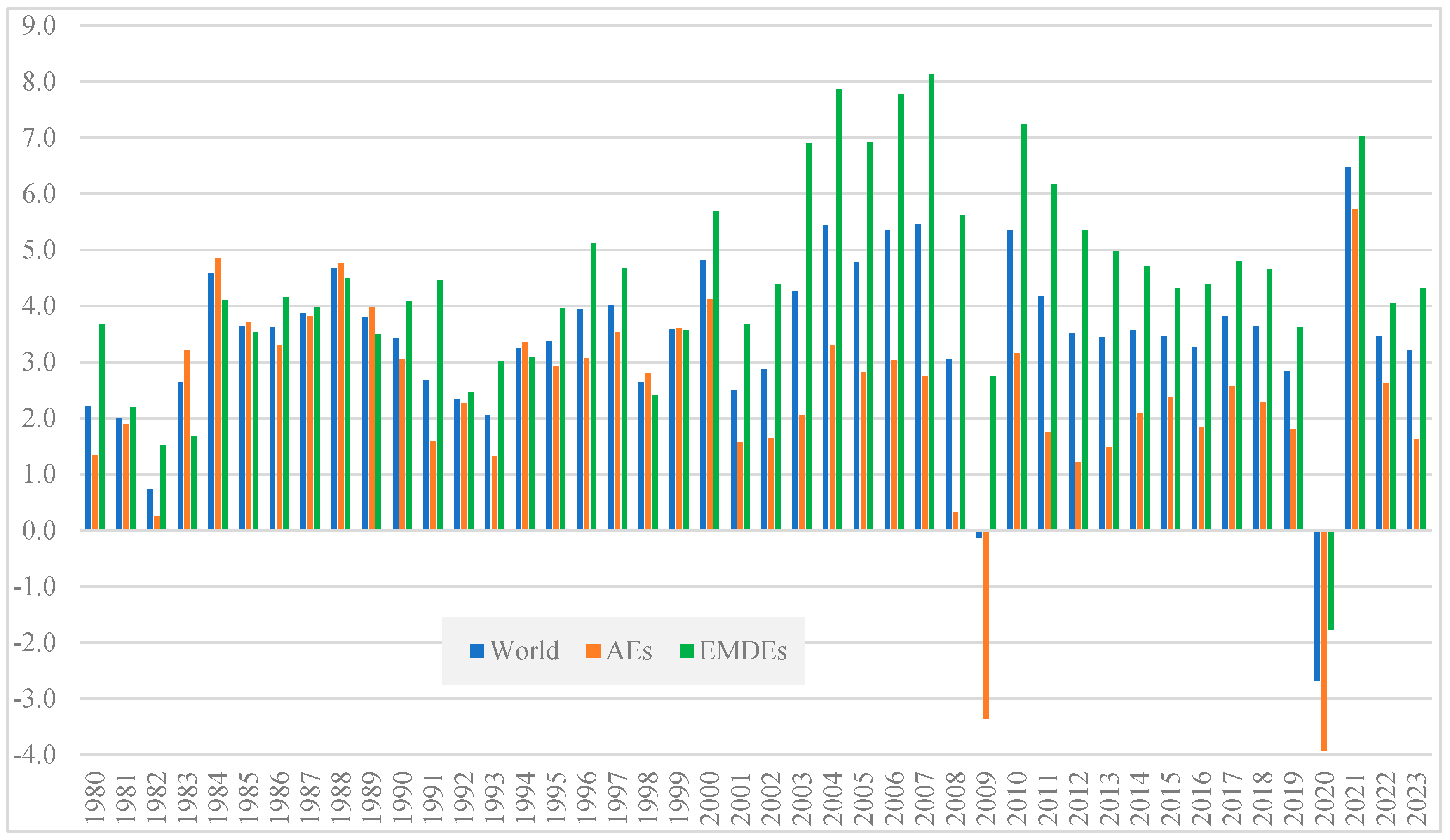

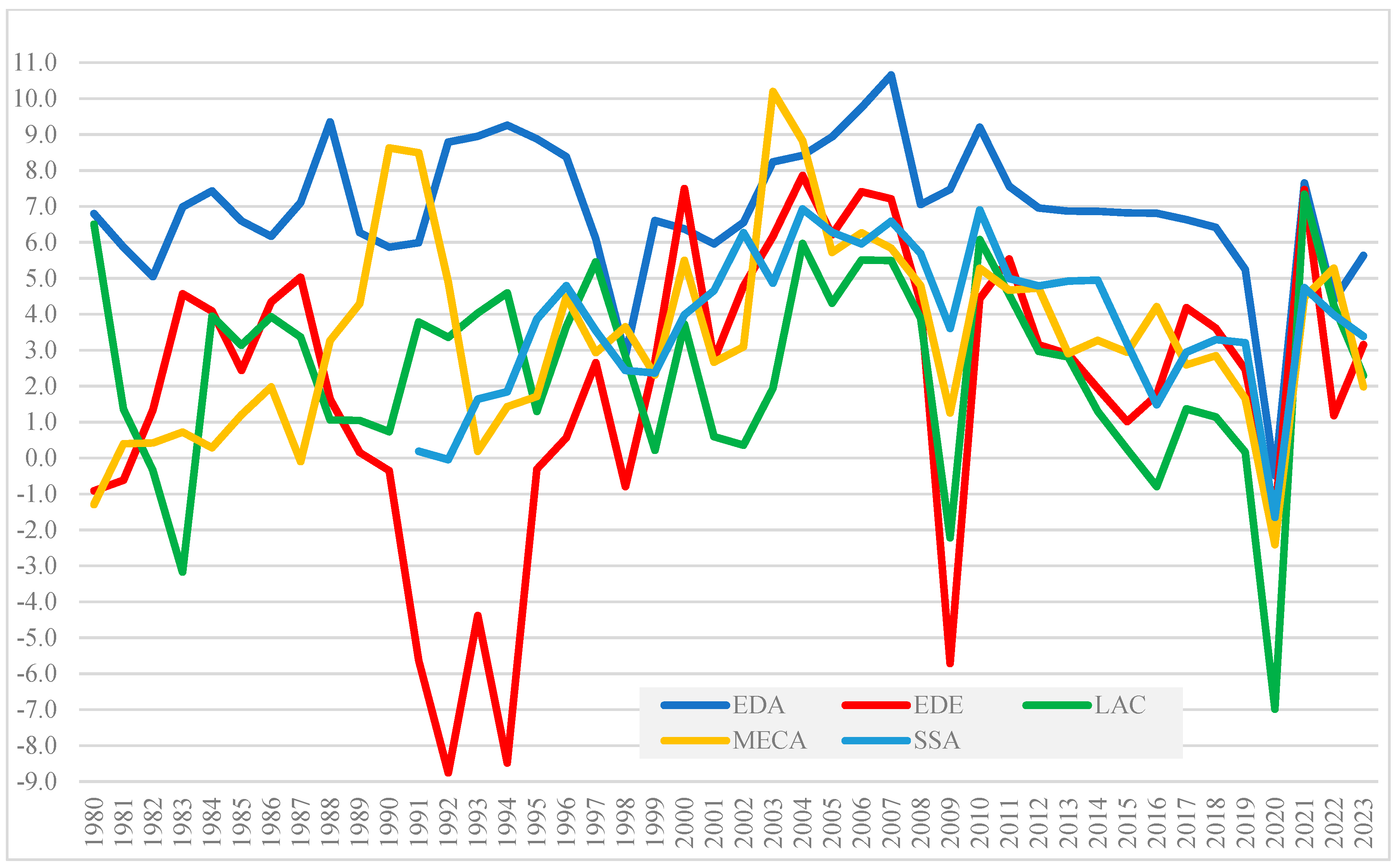

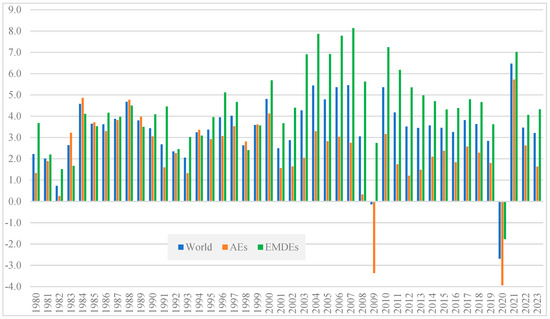

In the 1990s and 2000s (until the global financial crisis in 2008–2009), i.e., the period of rapid liberalization of trade and financial flows, global economic growth accelerated (Figure 5), mainly in EMDEs, particularly in the so-called Emerging and Developing Asia, using the IMF’s regional terminology (Figure 6). The regions of sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean benefited less due to many unresolved conflicts and domestic institutional and policy barriers. Globalization was instrumental in both global growth acceleration and rapid income per capita convergence in several EMDEs (Bhagwati 2004; Wolf 2005; Maskin 2015; Patel et al. 2024).

Figure 5.

GDP, constant prices, % change, 1980–2023. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, April 2024.

Figure 6.

GDP, constant prices, annual change in %, EMDE regions, 1995–2023. Notes: EDA—Emerging and Developing Asia, EDE—Emerging and Developing Europe, LAC—Latin America and Caribbean, MECA—Middle East and Central Asia, SSA—sub-Saharan Africa. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, April 2024.

AEs grew, on average, at a slower pace. However, they also benefited from globalization. In particular, it allowed for mitigating the forthcoming demographic barrier, that is, shrinking of the working-age population and population aging (Goodhart and Pradhan 2020). Global economic integration also helped AEs build global value chains (GVCs), benefit from economies of scale, and develop global financial centers on their territories.

After the GFC, the pace of global growth gradually decelerated, partly due to the direct consequences of the crisis but also due to stagnation in global trade liberalization and emerging protectionist barriers, especially at the end of the 2010s and the early 2020s (see Section 4). Nevertheless, EMDEs continued to grow faster than AEs, diminishing the income per capita gap between AEs and EMDEs built up over most of the 19th and 20th centuries.

3.2. Eradicating Poverty

Rapid growth in EMDEs helped eradicate extreme poverty, as measured by the poverty headcount ratio of USD 2.15 daily at the 2017 PPP (Table 2). Like growth trends, the most spectacular poverty reduction has been recorded in East Asia and the Pacific and South Asian regions (according to the World Bank’s regionalization).

Table 2.

Poverty headcount ratio at USD 2.15 a day (2017 PPP) (% of the population), 1981–2019.

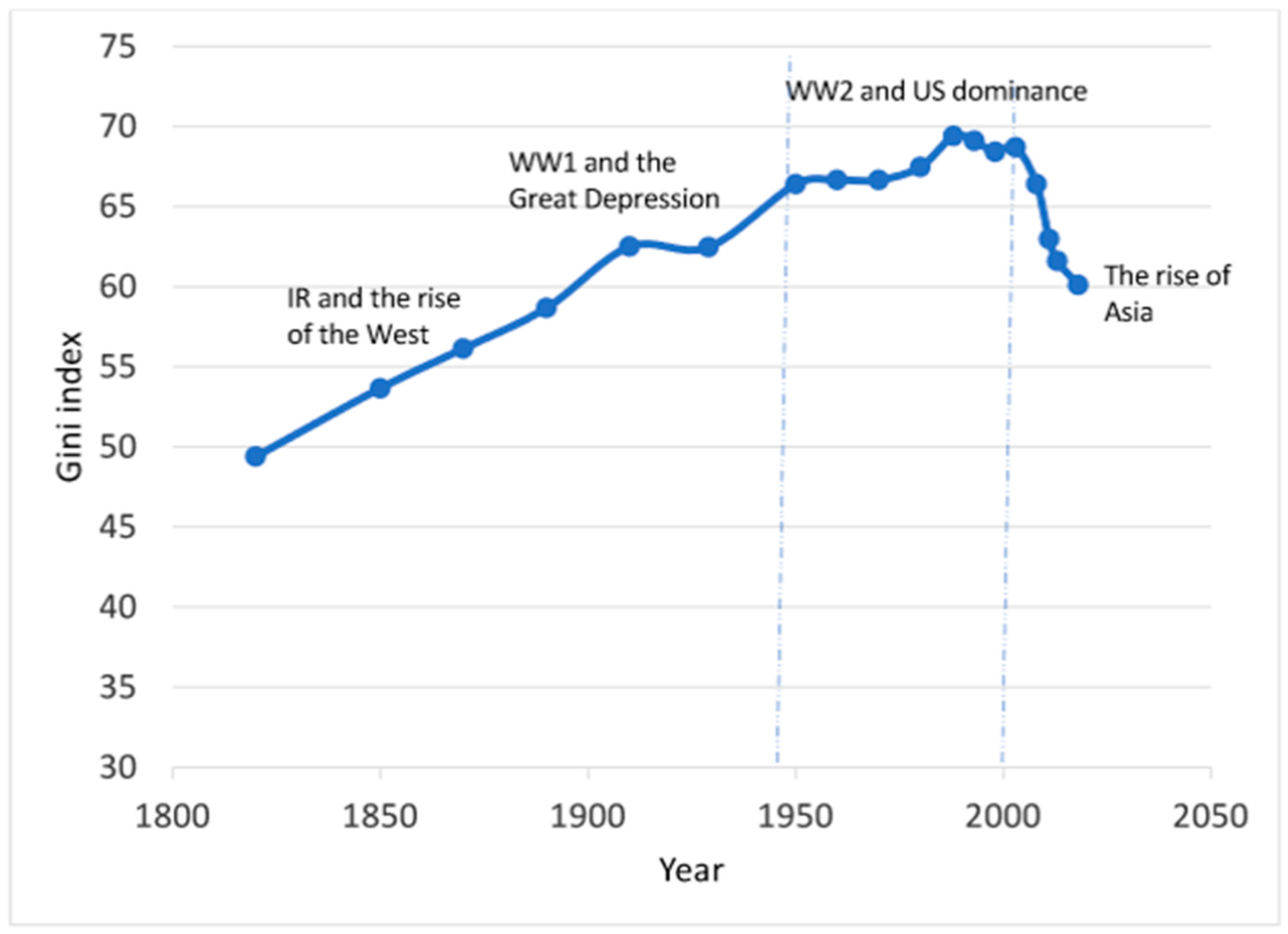

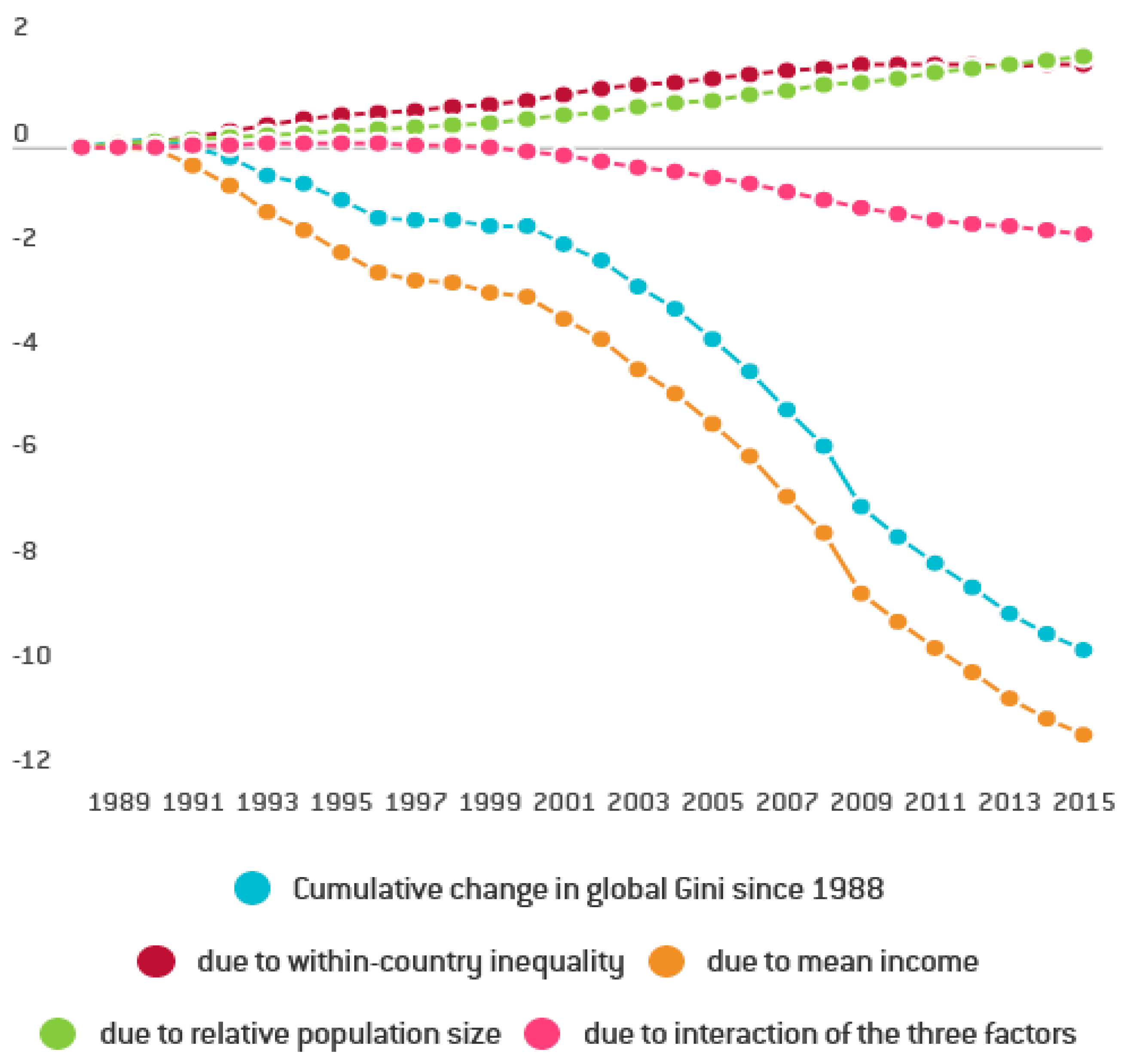

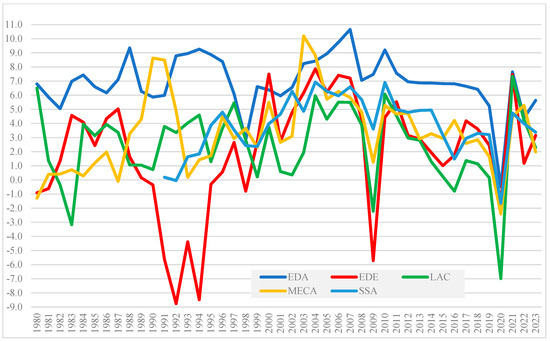

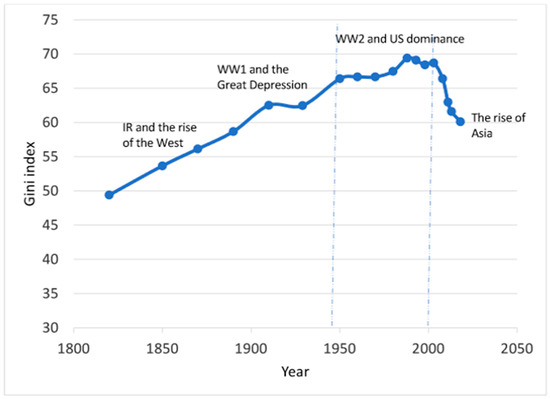

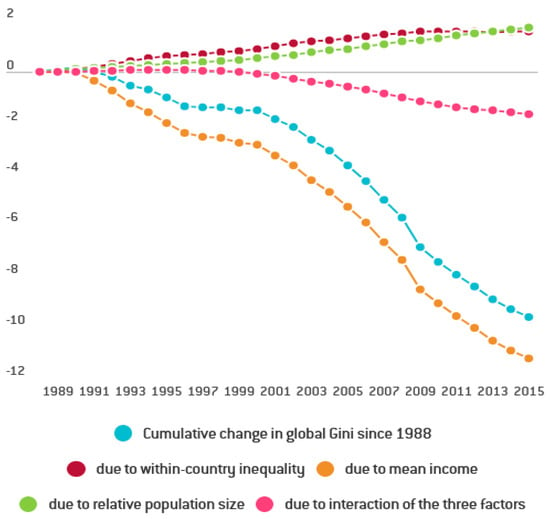

3.3. Diminishing Global Income Inequalities

Rapid economic growth in EMDEs, particularly in China, India, and other large Asian economies, also contributed to the substantial reduction in global income inequalities, i.e., inequalities among world citizens (Figure 7 and Figure 8). This reduction was driven by decreasing income per capita differences between countries (Darvas 2018), partly reversing the opposite trend dominating most of the 19th and 20th centuries (Milanovic 2020). On the other hand, structural changes in some AEs, especially in the US, in the absence of active domestic income redistribution policies, have contributed to increasing domestic income inequalities and, therefore, to the anti-globalization backlash (Pastor and Veronesi 2018). Interestingly, the diminishing trend in global income inequalities has continued in the period of weaker global growth (in the 2010s and early 2020s) despite various adverse shocks such as the GFC or COVID-19 pandemics (Darvas 2024).

Figure 7.

Estimated global income inequality, 1820–2018. Source: Milanovic (2020).

Figure 8.

Change in the global Gini coefficient of income inequality, 1988–2015. Source: Darvas (2018).

3.4. Disinflation

While inflation in individual currency areas is determined, in the first instance, by their monetary and fiscal policies, global trade, financial, and to a lesser degree, migration flows can contribute to the so-called supply shocks, either anti- or pro-inflationary. A rapid liberalization in trade flows in the 1990s and early 2000s helped AEs’ disinflation, pushing the prices of imported goods down (Rogoff 2003) and discouraging increases in domestic wage levels (Goodhart and Pradhan 2020). On the contrary, the recent protectionist trend has overlapped with the effects of monetary and fiscal policies in AEs that were too expansive in the 2010s and early 2020s (Dabrowski 2021), magnifying a global inflation shock.

3.5. Globalization-Related Challenges and Socio-Political Costs

Global gains such as rapid growth, especially in EMDEs, poverty eradication, diminishing global income inequalities, and support to disinflation were associated with structural adjustment, for example, moving some manufacturing and service capacities from AEs to EMDEs. It involved economic and social adaptation costs on national, regional, and sectoral levels, especially when national and regional policies did not provide sufficient cushioning and support to potential losers. In the absence of well-tailored redistribution policies, structural changes might also cause increasing national income inequalities (see Section 3.3). All these side effects have been actively exploited by populist politicians of various colors and have partly contributed to the protectionist backlash discussed in Section 4.

4. Protectionist Backlash and Associated Risks to Global Socio-Economic Development

4.1. Change in Integration Trend

From 2008, global trade and financial integration slowed and was even partly reversed (Figure 1 and Figure 3). This trend change is often attributed to the effect of the GFC (see James 2018). While it may be true in the case of financial flows (implosion of financial markets caused by the GFC, followed by tighter micro- and macro-financial regulations, and a partial return to some forms of capital controls in EMDEs—see Figure 4), one can look at other explanations in the case of trade flows. The implementation of trade liberalization measures envisaged by the GATT Uruguay round and the Marrakesh agreement was completed around the mid-2000s. The new WTO negotiation, the so-called Doha Development Round, failed (Bhagwati 2012), so no new global trade liberalization impulses exist. The proliferation of regional and bilateral preferential trade agreements (PTAs), especially in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, somewhat mitigated the stagnation trend but could not fully compensate for the lack of progress in global trade negotiations9.

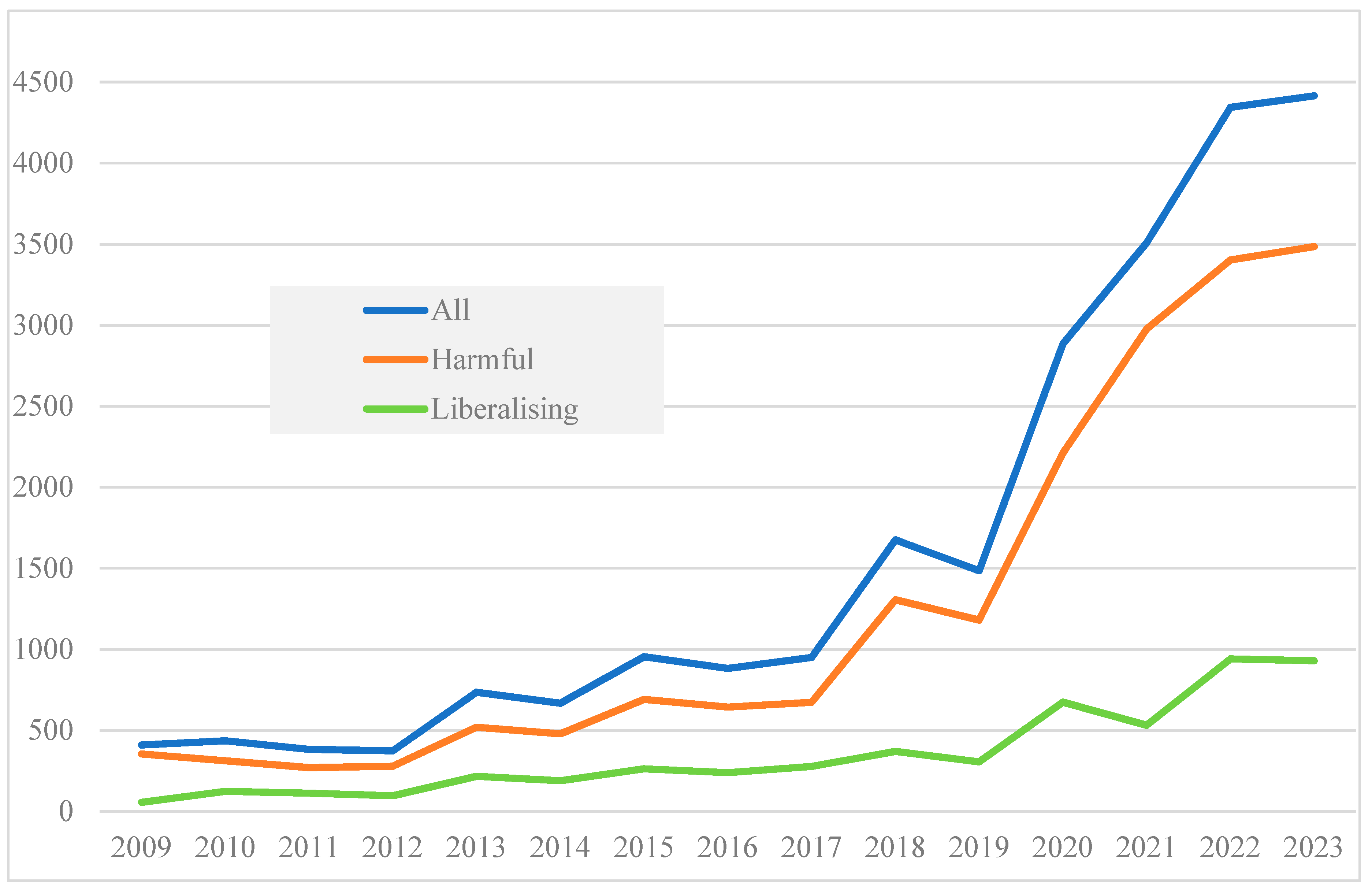

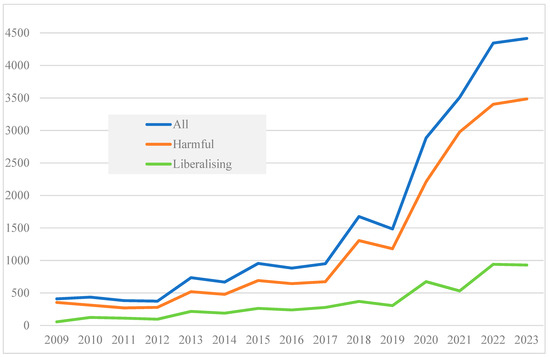

The end of the 2010s and early 2020s brought an increasing wave of protectionism in various corners of the world, underpinned by national political developments in individual countries, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the proliferation of geopolitical rivalries and conflicts, both ‘hot’ (for example, the war in Ukraine) and ‘cold’ (the increasing geopolitical rivalry between the US and China—see Section 4.2). Figure 9 shows the increasing number of harmful trade interventions worldwide. While these are rough numbers (individual interventions have various scales and impacts on trade flows), they confirm a rapidly growing protectionist trend.

Figure 9.

Number of trade interventions imposed annually worldwide (2009–2023). Source: Global Trade Alert, https://www.globaltradealert.org/global_dynamics (accessed on 18 August 2024).

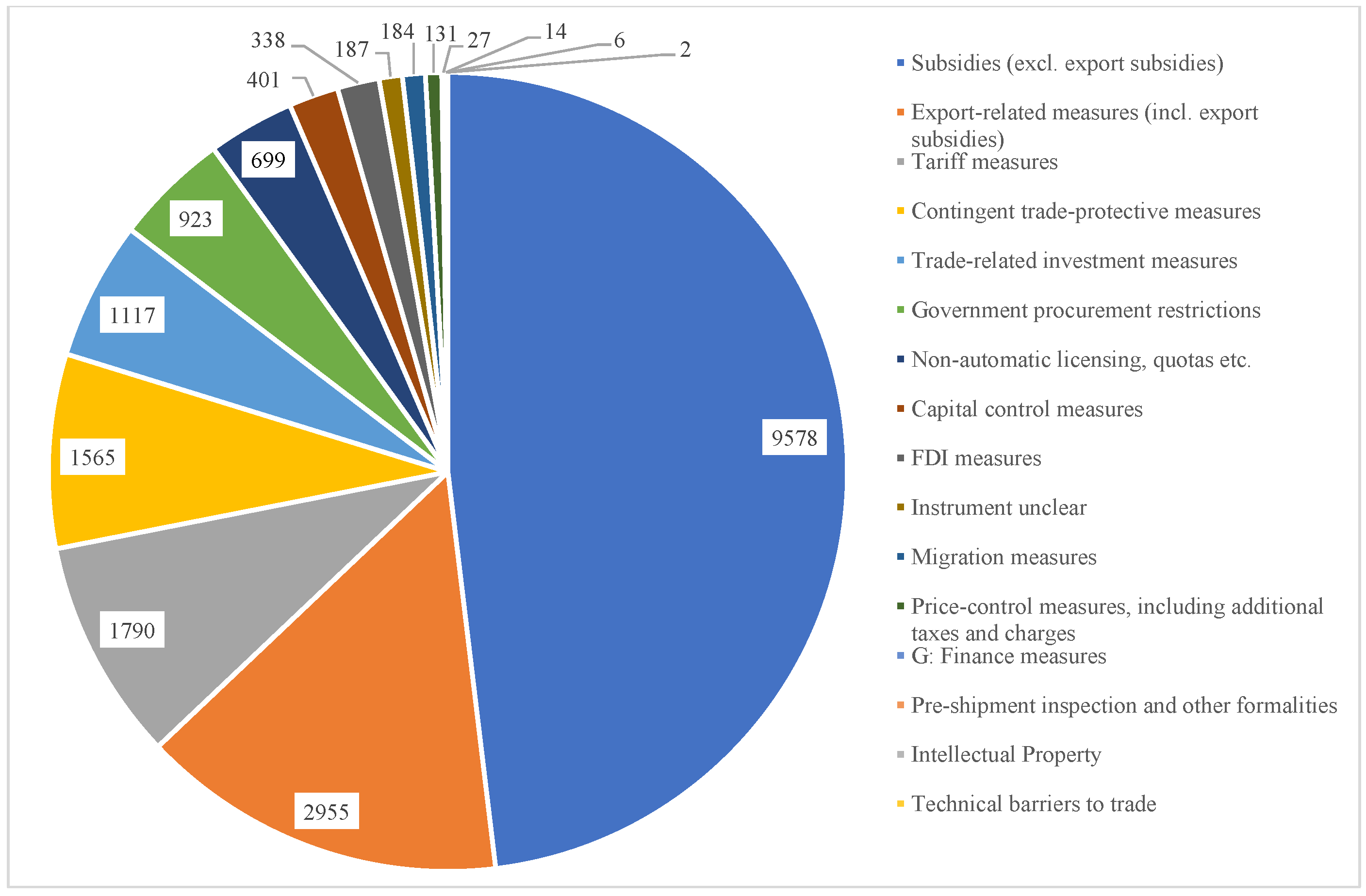

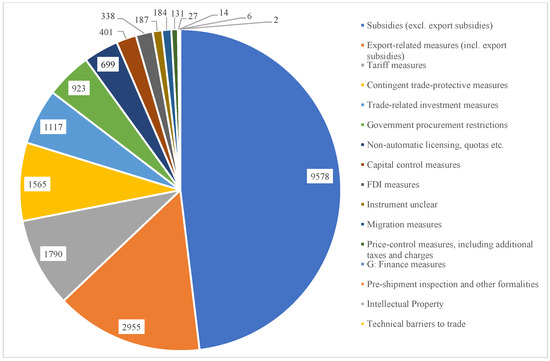

Government financial support to exporters (Figure 10) and import-substituting producers has played a leading role in this protectionist race (Fritz and Evenett 2021; Evenett 2023). It has had various forms depending on the specific sector/industry, for example, government grants, tax exemptions, borrowing on preferential terms, loan guarantees, use of subsidized energy, capital injections, and equity stakes, including bailouts, etc. (IMF et al. 2022; Evenett 2023). Although subsidies are the subject of two WTO agreements, the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures and the Agreement on Agriculture, several regulatory loopholes allow circumventing them in practice.

Figure 10.

Number of harmful trade interventions by policy instruments used, cumulatively, 2009–2024. Source: Global Trade Alert, https://www.globaltradealert.org/global_dynamics (accessed on 18 August 2024).

4.2. The Rise of China and the US–China Trade Conflict

Since the early 1980s, China has recorded rapid economic growth due to domestic economic reforms (including economic openness), an export-led growth strategy, and the benefits of globalization. As a result, China has restored its dominant economic power status, which it enjoyed until the early 19th century. China’s share of the world GDP, calculated in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), increased from 2.6% in 1980 to 18.4% in 2021 (IMF 2023, Table A, p. 99). China has become a leading manufacturer, producer, and exporter, competing successfully with other EMDEs and AEs (Jean et al. 2023). However, the market-oriented transition in China has not been complete, and the role of the government and the Chinese Communist Party in economic management has remained significant (European Commission 2017). Chinese producers and exporters have enjoyed government support that is incompatible with the WTO rules and exceeds, by several times, the state aid in AEs (Bickenbach et al. 2024). While AEs have benefited from cheaper Chinese imports (see, e.g., Section 3.4 and Goodhart and Pradhan 2020), their expansion has also contributed to the protectionist backlash, in the first instance, in the US.

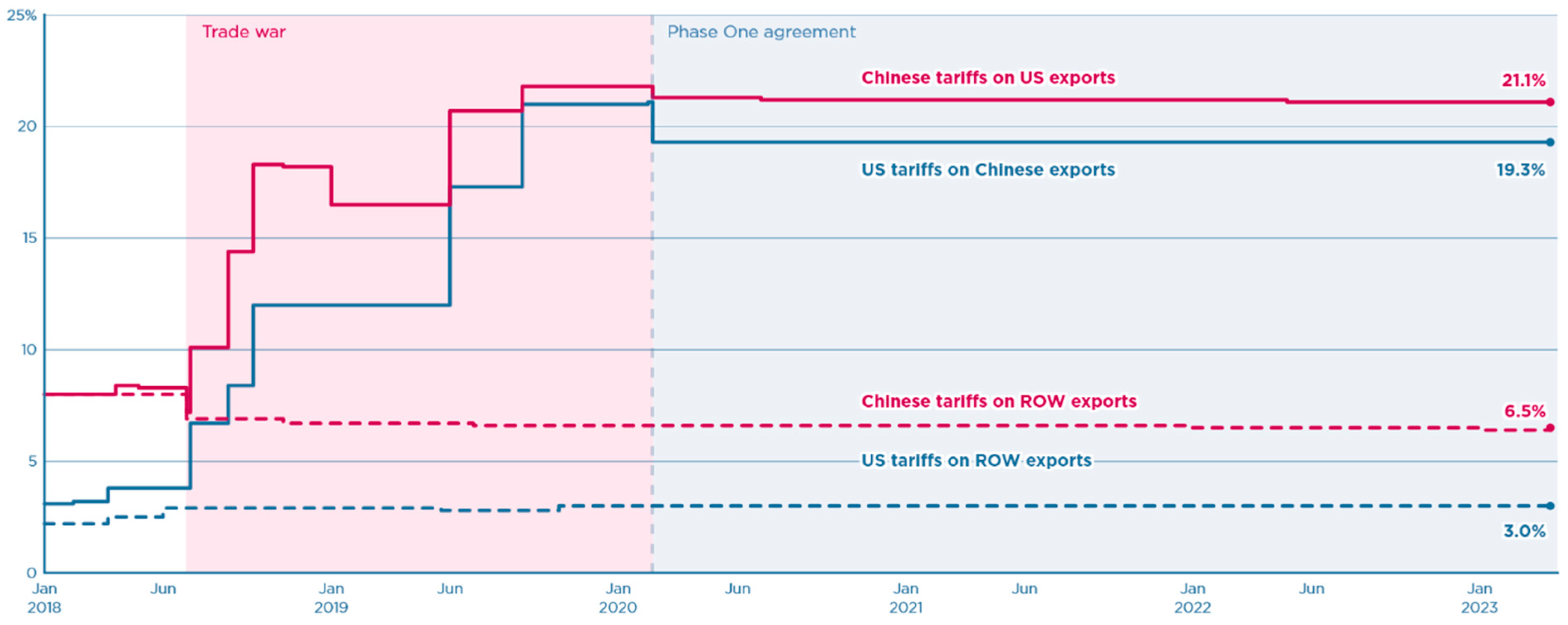

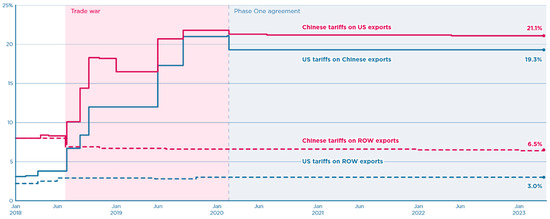

US–China trade and economic tensions, which grew gradually during the 2000s and 2010s, broke out in the form of open conflict in 2018. As a result, the average US trade-weighted import tariffs for Chinese exports increased from 3.1% in January 2018 to 21.0% in September 2019 (Figure 11). In February 2020, due to the Phase One Agreement between the US and China, they decreased to 19.3% and have stayed at this level since then (Bown 2023b). Chinese trade-weighted import tariffs for US exports increased from 8.0% in January 2018 to 21.8% in September 2019. From February 2020, they amounted to 21.3%. At the same time, they gradually decreased tariffs for imports from the rest of the world from 8% in January 2018 to 6.5% in January 2023.

Figure 11.

US–China tariff rates toward each other and the rest of the world (ROW). Source: Bown (2023b).

The protectionist drift in US trade policy under the Trump administration did not affect only China (Bown and Kolb 2023). Average US trade-weighted import tariffs for exports from the rest of the world increased from 2.2% in January 2018 to 3.0% in October 2019 (Figure 11).

In January 2023, the higher tariffs covered 66.4% of US imports from China and 58.3% of China’s imports from the US (Bown 2023b).

The next step in this trade war was taken by the Biden administration on 14 May 2024. The US government introduced additional tariffs (on top of those introduced by the Trump administration) on imports from China in several sectors. For example, tariffs on semiconductors increased from 25 to 50%, solar cells from 25 to 50%, electric vehicle batteries from 7.5 to 25%, and electric vehicles from 25% to 100% (Dadush 2024).

At the beginning of the US–China trade war, the European Union (EU) kept itself far from this conflict. On 20 December 2020, it concluded, in principle, a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China, which envisaged several liberalization measures on both sides (Dadush and Sapir 2021). However, this agreement has not been finalized since then. On the other hand, as of 14 June 2024, 41 out of 53 ongoing EU trade defense investigations related to imports from China.10 Following one of these investigations, on 12 June 2024, the European Commission imposed provisional countervailing duties of between 17.4 and 38.1% on imports of battery electric vehicles from China.11

While the decisions against imports from China adopted by the US and EU in May–June 2024 differed legally (the EU’s decision was more compatible with the WTO’s procedures), they may have a similar detrimental effect on global trade. Furthermore, China will respond, most likely, with reciprocity measures against US and EU exports.

4.3. A New Protectionist Rhetoric

‘Traditional’ protectionist arguments referred, among others, to the necessity of protecting infant industries, jobs, and welfare systems and supporting import-substitution programs, as well as consumer, health, and environmental protection. The new protectionism employs seemingly attractive but economically misleading slogans such as shortening supply chains, onshoring, reshoring, nearshoring, friend-shoring, reindustrialization12, ending/correcting ‘hyperglobalization (a term coined by Rodrik (2011))’, national security considerations, implementation of a ‘green’ agenda, etc.

The COVID-19 pandemic and policy responses to this calamity have provoked some of these arguments13. Lockdown measures initially aimed to stop the spread of the pandemic. They sought to limit the infection contagion when this goal was not met. They concentrated on national borders, where administrative controls could be easier to execute than those inside the country (although several countries have introduced formal bans on the internal movement of people). There was little international cooperation in adopting lockdown policies, even inside such a deeply integrated bloc as the EU, and many beggar-thy-neighbor measures. As a result, the pandemic caused far-reaching disruption in global supply chains (Léry Moffat and Poitiers 2024), that is, in trade, transportation, and logistical links, leading to physical shortages in many goods and services, for example, semiconductors (Kaur 2021) and containers (Teodoro and Garratt 2023).

The incorrect macroeconomic diagnosis of the crisis’ character (destruction of aggregate demand, such as during the GFC) led to incorrect macroeconomic policy responses—launching massive monetary and fiscal stimuli (Dabrowski 2021). They caused global inflationary pressures in 2021–2023 and deepened disequilibria in individual product and service markets. Structural changes in demand have also caused disequilibria. For example, progress in digitalizing many services (accelerated by lockdowns) increased the demand for semiconductors and various software products.

Trade and transportation disruptions and physical shortages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures stayed behind the numerous calls for shortening supply chains, reshoring, and nearshoring. They abstracted from the fact that pandemic-related disruptions also affected local markets and supply chains. They also disregarded the causes of supply shortages. Fortunately, some of these calls abated after lockdown measures were terminated, and the market mechanism helped to restore/adapt the broken GVCs quickly. On the other hand, tighter monetary policies helped to rebuild the equilibrium between demand and supply.

However, there have been other arguments (ecological and geopolitical) in favor of reshoring and nearshoring, which have not disappeared. Shortening supply chains, which can reduce CO2 emissions and prevent climate change, has been one of them. It can be the correct argument if nearshoring or reshoring will not increase cumulative CO2 emissions due to a less efficient production and service chain. A universal carbon tax (see Section 5) would be the best instrument to stimulate the optimal localization decisions of economic agents rather than protectionist trade policy measures.

Geopolitical considerations are more challenging to internalize into the autonomous market choices of economic agents. They are subject to government decisions, and many of them affect trade and investment policies. However, governments must understand the socio-economic costs of such decisions. Geopolitical arguments cannot be overplayed, and trade and financial policy instruments cannot be overused for foreign and security policy purposes (see Section 4.4).

4.4. Geopolitical Tensions and Economic Openness

In the 1990s, after the collapse of the USSR, the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, and the end of the Cold War, several countries could enjoy the peace dividend in the form of lower military spending, fewer security concerns in trading military or dual-use products and technologies, academic and technical cooperation, more freedom in the movement of people, and a better geopolitical atmosphere in global and regional economic cooperation14. However, it was a relatively short episode in world history.

The terrorist attack against the US on 11 September 2001 ended the atmosphere of relatively peaceful global cooperation. Military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq caused the necessity of higher military spending, at least in the US. Various non-military security measures in the US and other countries affected the movement of people (especially for citizens of countries considered potential terrorist hubs) and financial transfers (tighter control of trans-border transfers to prevent financing terrorism). Fortunately, trade flows and FDI remained unaffected.

The end of the 2010s and early 2020s have brought a further deterioration in international relations. Among various examples of increasing geopolitical tensions and open conflicts, two of them deserve additional comment.

The first concerns the increasing geopolitical tensions between the US and China beyond the trade and economic conflict discussed in Section 4.2. They have been caused by the rapidly increasing military potential of China, its more aggressive foreign and security policies, its increasing assertiveness against its Asian neighbors, many of which are the US’ allies and enjoy the US’ security guarantees, an autocratic drift in China’s domestic policies, and the US’ fear of losing its status as the single global superpower. The US’ protectionist measures against imports from China analyzed in Section 4.2 were partly motivated by geopolitical and security considerations. National security considerations also stood behind the export control measures introduced by the US Department of Commerce in October 2022, aimed at curbing exports of advanced chips and other cutting-edge technologies to China (Nellis et al. 2022).

The US has pushed their allies in Europe and the Asia-Pacific to create a common front against China, a partly successful pressure. China has also given increasing attention to national security considerations in its economic policy decisions (Choyleva 2024; Leonard 2024).

Fortunately, tensions between the US (and their allies) and China have not reached the stage of open confrontation, although they have an increasingly negative impact on economic relations. However, given the economic and trade potential of China and the US (and other AEs actually or potentially involved in this conflict), negative consequences for the global economy can be far-reaching (see Section 4.5).

The second severe disruption to the post-Cold War global political and economic order has been caused by the increasingly aggressive actions of Russia in its neighborhood, culminating with its full-scale military aggression against Ukraine in February 2022. The initial response of the US, EU, UK, and their allies concentrated on scaling up economic and financial sanctions initiated after the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 (Dabrowski and Avdasheva 2023). Western military aid to Ukraine came later. Although Russia’s share in the global GDP and global trade is much lower compared to China15, Russia’s role as a large supplier of energy resources and its countermeasures against sanctions issuers (Dabrowski and Avdasheva 2023) caused severe economic turbulences beyond the direct zone of conflict in 2022–2023 (see, e.g., Arndt et al. 2023; McWilliams et al. 2024).

The rise of global geopolitical tensions is an argument for the subordination of economic policies to security considerations. It concerns higher military and security-related expenditures, development of the defense industry, trade and investment policies, cross-border scientific and technological cooperation, financial flows, migration, etc. The vagueness of security arguments, i.e., what are the real security risks, which instruments can be used to minimize them, what are their potential benefits (in achieving security goals) vs. their economic, social, and political costs (direct and indirect), makes the debate difficult and sometimes emotional. One can suspect that security arguments are sometimes used to mask ‘traditional’ protectionist demands.

Conceptually, measures motivated by security considerations can be divided into preventive (aimed at avoiding/minimizing ex ante risks) and reactive (penalizing unacceptable actions). However, an ex ante cost–benefit analysis is required in both cases. An ex-post assessment of the effectiveness of sanction packages imposed in the less or more distant past against geopolitical adversaries in achieving intended goals vs. the costs for sanction issuers and third parties (see Peksen 2019 for the literature overview) can serve as a good starting point for an ex ante analysis of any new sanction measures.

For example, the experience of far-reaching sanctions against Russia in 2022–2024 seems disappointing. They failed to stop the aggression against Ukraine and reduce, in a meaningful way, Russia’s economic and military potential to continue the war. They were frequently circumvented (e.g., Hilgenstock et al. 2023; Bilousova et al. 2024; Astrov et al. 2024; Chupilkin et al. 2024). They also caused collateral damage to European economies by increasing energy prices in 2022.

The UN’s sanctions against Iran between 2006 and 2016 were more effective in achieving their goal, that is, pushing Iran to limit its military spending (Dizaji and Farzanegan 2021) and freeze its nuclear program. However, the Iranian economy was smaller and less self-sufficient than the Russian one, and the sanctions against Iran had a global character. In Russia’s case, several EMDEs (approximately half of the global GDP) have not joined sanctions introduced by the US, EU, UK, and their allies.

This experience with sanctions against Russia should serve as a lesson to be careful when weaponizing trade and financial instruments in geopolitical rivalry with China. This much bigger economy is more deeply rooted in the global trade and investment relations network, so attempts at its sanctioning can fail to achieve geopolitical goals and cause collateral damage to the world economy (see Cerdeiro et al. 2023; Wache et al. 2024).

4.5. What Can Be Lost?

Failure to stop protectionist trends can lead to erosion of the gains from globalization and undermine growth and macroeconomic stability perspectives in both AEs and EMDEs.

Economic growth can slow down further, given that protectionism is not the only headwind a global economy faces. A declining working-age population and population aging are other challenges, particularly in Europe and East Asia. AEs may become the main losers, but several EMDEs will also suffer. The latecomers of globalization (Africa and part of the Middle East) can lose a chance of catching up with the rest of the world.

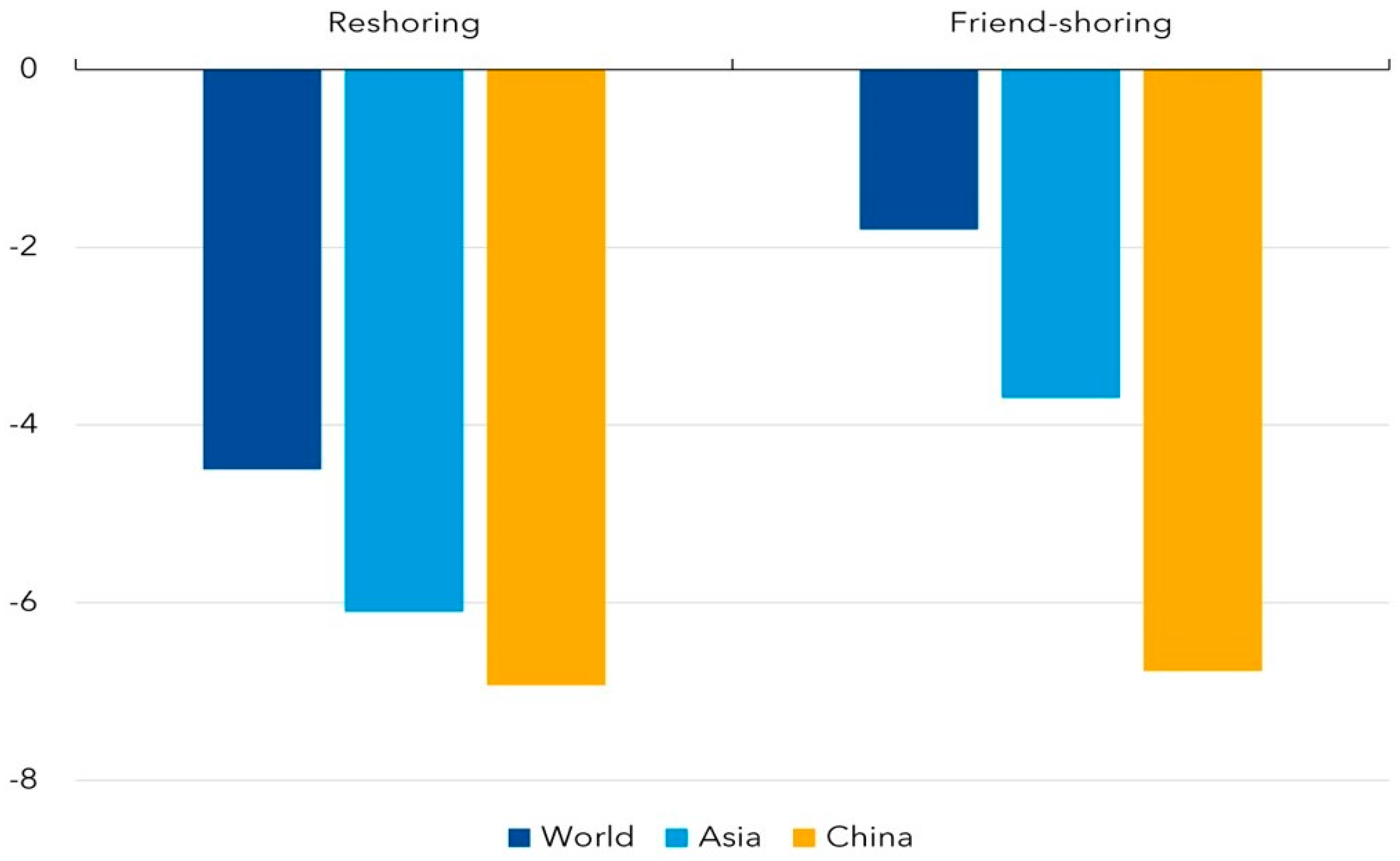

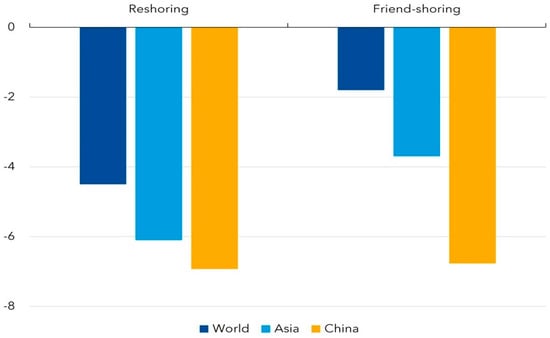

Materialization of such a scenario does not necessarily require a global trade conflict like that in the early 1930s. It is enough to continue the fragmentation of the world trade system along the lines of geopolitical blocs, that is, friend-shoring (see Figure 12). Even countries that could expect to benefit from US–China trade tensions, for example, Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia, would be eventual losers because the general equilibrium effect (slower growth of a global economy) might outweigh trade diversion in their favor (Cerdeiro et al. 2023; Wache et al. 2024).

Figure 12.

Losses from friend-shoring and reshoring scenarios (GDP, % deviation from the baseline scenario). Source: Cerdeiro et al. (2023).

Innovation and potential productivity growth may be other losers. They depend primarily on the free international movement of technologies, capital, investment, and people and unrestricted cooperation between universities and other research centers. Unfortunately, this movement has already been restricted, especially (but not only) between the US and China (Poitiers and Sekut 2024).

Unlike in the 19th and 20th centuries, scientific and technical progress is no longer generated predominantly in Western Europe and North America. Research and industrial centers in some EMDEs, especially in China, play an increasing role in new patents, high-quality academic publications (Poitiers and Sekut 2024), and frontier technology research. Hence, the bifurcation of research and innovation efforts will be costly and cause slower productivity growth.

Trade, investment, technology protectionism, and the slower global growth they cause will not help mitigate climate change. The mounting trade tensions around China’s dominance in producing solar panels (Allison 2023), electric vehicles (Webster 2024), and high-capacity batteries (Poitiers and Sekut 2024) are good examples (see Section 4.2). They represent a clear case of the conflict between the global decarbonization agenda (which requires the mass and inexpensive production of devices and materials crucial for completing a green agenda) and industrial policy goals and geopolitical concerns in some AEs, which focus on self-sufficiency in sectors considered strategically important.

Slower growth, especially in EMDEs, caused by protectionist drift will not help further eradicate poverty and reduce global income inequalities (between citizens of the world), contributing to even stronger cross-border migration pressures. However, it can help reduce in-country inequalities.

Fighting the post-pandemic wave of inflation will take longer and involve higher output losses because protectionist measures have already generated a pro-inflationary supply-side shock16. Looking ahead, continued trade protectionism or even the absence of further trade liberalization measures will increase the macroeconomic and social costs of price-stability-oriented monetary policies.

Finally, the fragmentation of global trade and financial systems can undermine geopolitical stability. One can observe a vicious circle: the current conflicts contribute to protectionism and economic disintegration, but the latter can trigger new conflicts. Even if trade and financial integration are not perfect safeguards against political and military conflicts (as history teaches us), they increase the costs of such conflicts and, therefore, can serve as a conflict deterrent to a certain degree (Lee and Pyun 2009). Furthermore, slower poverty eradication in EMDEs and slower progress in mitigating climate changes (due to global economic fragmentation) can also trigger new violent domestic and international conflicts.

5. Remedies

It is not too late to stop the protectionist drift and avoid the associated losses described in Section 4.5. There are at least three avenues to achieve this goal: (i) institutional reform of the WTO and continuation of multilateral negotiations aimed at updating existing global trade agreements and concluding new ones; (ii) further development of regional and inter-regional PTAs; (iii) domestic policy reforms, especially in the case of large trade players. These three avenues are at least partly interlinked.

The reform of the WTO and negotiation of a new set of global trade agreements would be the best. It could arrest the erosion of the worldwide trade rules established during the subsequent rounds of GATT and WTO negotiations. It would also save the WTO as a meaningful international institution. In an optimistic scenario, it could provide a new impetus to global trade liberalization.

Reform of the WTO has been discussed from various angles, at least since the start of the unsuccessful Doha Round (see, e.g., Soobramanien et al. 2019). Since 2017, the most urgent task has been to reform the WTO’s Appellate Body, which was disabled by the US’ decision to stop filling vacancies17. The inability of the Appellate Body to perform its statutory role paralyzes the entire system of the WTO to dispute settlements18, the primary enforcement mechanism in the hands of these institutions.

Updated international agreements are urgently needed in the trade in services (given the increasing share of services in the GDP) and harmonization of green policies (to avoid protectionist backlash motivated by a green agenda). The growing role of subsidies and other forms of financial support to domestic producers in industrial and trade policies (see Section 4.1 and Figure 10) suggests the necessity of updating the WTO’s regulations on subsidies.

Given the unanimity requirement in the WTO’s decisions, which are challenging to achieve, the plurilateral agreements of countries interested in regulating trade and investment relations in a particular sector or in solving a specific problem (a coalition of willingness) seem to be the most pragmatic negotiation strategy (Schmucker and Mildner 2023). To the greatest extent possible, such agreements should consider the interests of a maximum number of WTO members, including less developed countries, not only those participating in the negotiation. They should remain open to all potential future signatories.

Parallel to the reform of the WTO and continuing global trade negotiations, efforts should be put into further developing bilateral and multilateral PTAs and deepening existing ones. PTAs are the second-best solution compared to global trade liberalization. As mentioned in Section 4.1, they involve both trade-creation and trade-diversion effects. However, if they have sufficiently broad (regional or inter-regional) coverage, the first effect may prevail over the second one. They may reinforce trade-gravity effects from geographic proximity if they involve close neighbors. In addition, they also often serve other goals beyond trade and investment relations, such as setting the stage for deeper regional economic and political integration, support to economically less-developed partners, etc. They are a form of friend-shoring (see Section 4.5).

Unfortunately, the pace of regional/interregional trade and investment integration based on PTAs has slowed since the end of 2010s due to the same protectionist drift that paralyzed global trade negotiations and WTO reform. In January 2017, the Trump administration in the US withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) signed a year earlier. Although 11 other signatories from North and South America, East and South East Asia, and the Pacific region decided to continue this deal under a new name (the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership), its trade and economic significance and impact are smaller than the original TPP due to the absence of the most significant partner (the US). The Trump administration also suspended negotiations on another mega-deal—the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the EU.

The EU has tried to continue its relatively open trade policy by signing several PTAs with partners in various continents. However, in the early 2020s, its trade liberalization effort has also stalled. The EU–Australia free trade negotiation was suspended in 2023 due to reluctance to open part of the Single European Market to import Australian agriculture products (Sapir 2023). The EU’s agriculture protectionism can also be blamed as one of the problems in finalizing the EU–Mercosur Trade Agreement, despite reaching a political agreement between both sides in June 2019 (Dadush and Baltensperger 2019; Demarais 2024).

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) (Echandi et al. 2022) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (in the Asia-Pacific region)19 are two large regional PTAs concluded at the end of the 2010s/early 2020s. Even if both are not very deep in their economic contents (focusing primarily on trade in goods), they can help integrate large regional markets and boost economic growth. It is crucial for Africa; however, many other accompanying trade facilitation measures are needed to grasp the full potential benefits of AfCFTA (Echandi et al. 2022; Fofack 2024). The resolution of several violent conflicts is another condition of successful AfCFTA implementation.

Large regional PTAs could create a bridge towards a more straightforward conclusion of global deals under the auspices of the WTO. In the first instance, it would depend on the political readiness of major parties to progress in this direction (which is lacking at the beginning of 2024). However, there are also other, more ‘technical’ obstacles. First, the existing network of PTAs engages WTO members unequally. Several large EMDEs, such as Bangladesh, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Russia, and South Africa, participate only marginally in this system. Second, the existing PTAs are incompatible, so finding a common agenda and interest between their participants would be difficult. Third, the unilateral trade preferences granted to developing countries under the Generalized System of Preferences and similar schemes may discourage beneficiary countries from engaging in trade negotiations, which require trade concessions.

The third avenue, market-oriented and macroeconomic stability-enhancing reforms in individual countries, can facilitate further global and regional economic integration and change domestic political economy balances in favor of trade and investment liberalization, as seen in the 1980s and 1990s in several corners of the world (see Section 2). Usually, the focus is on large EMDE players such as China, India, Argentina, Brazil, and South Africa. In particular, China should rethink its industrial policy given its role in the world manufacturing trade. Reducing state aid, increasing openness to foreign investment, better protecting property rights, including intellectual property rights, and eliminating other distortive policies could address at least some of the concerns of its trading and investment partners.

AEs also have an extensive agenda of trade-friendly domestic reforms. They concern not only the most obvious suspect, i.e., agriculture support and its protection against external competition (in the case of the US, EU, Japan, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, South Korea, and the UK20; see IMF et al. 2022). AEs must also mitigate their appetites to conduct industrial policies (see Bown 2023a). They should abandon dreams of reindustrialization, which are inconsistent with the level of their socio-economic development and demographic constraints. They also should assess the fiscal costs of industrial policies (especially when they require subsidies) against the continuous fiscal imbalances and high public debts in most AEs. Similarly, realistic cost–benefit analyses regarding proposals to use trade and investment measures against actual or potential geopolitical adversaries are needed.

6. Summary and Conclusions

After four decades of the second wave of globalization, the world economy and global economic order are at a crossroads. The mounting protectionist pressures in various corners of the world put the perspective of future economic growth and further reduction of extreme poverty and global income inequality (between citizens of the world) under question. These are not temporary frictions caused by unexpected shocks such as the GFC, the COVID-19 pandemic, or the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Unfortunately, they look like a sustainable trend underpinned by the rising wave of populism, nationalism, and geopolitical rivalry. While geopolitical tensions and security concerns serve as a convenient argument for protectionism, the latter may trigger new tensions or magnify existing ones.

Given the benefits of global trade and financial flows and the degree of global economic interdependence, the scenario of far-reaching deglobalization/fragmentation of the sort experienced in the 1930s looks rather unlikely any time soon (unless a worldwide military conflict happens). Instead, economic integration within geopolitical alliances and blocks (friend-shoring) seems more probable. Such a scenario will involve substantial welfare losses due to trade diversion and general equilibrium effects (Cerdeiro et al. 2023). Friend-shoring may also not be a good option for all global trade participants due to their geographic locations or unwillingness to take sides in geopolitical confrontations. It can also lead to higher trade concentration (Seong et al. 2024). Furthermore, history teaches us that geopolitical alliances are not always stable. Therefore, trade and investment choices based on geopolitical considerations may suffer from additional volatility.

The degree of economic and social losses caused by the fragmentation along geopolitical frontiers will depend on how aggressive friend-shoring will be against the existing global trade order. One possibility is a proliferation of PTAs (motivated by geopolitical considerations) within the current WTO regime, as observed since the beginning of the 21st century. Another would be dismantling the existing global trade and investment order and institutions and replacing them with regional or bilateral trade deals. The second scenario would be economically more damaging than the first one.

There is still time to stop the protectionist drift, reform the WTO, and reinforce the existing global economic, trade, and financial order. However, concessions must be made from all sides of international trade disputes. Most countries should return to the path of domestic market-oriented reforms, which provided them and the entire world economy with unquestionable economic benefits in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s and facilitated global trade and financial liberalization. G20 seems to be the best-positioned political forum to agree on the key directions of global trade reform and resisting protectionist drift (as happened in the aftermath of the GFC). The reformed WTO with the support of the IMF and World Bank should play a coordinating role in their implementation.

AEs should reduce their financial support to the agriculture sector and increase the openness of their markets for agricultural goods and labor-intensive services from EMDEs. Due to their economic structures, both are important for developing EMDEs’ export capacities. AEs should also abandon dreams of reindustrialization and reject temptations to excessively weaponize trade, investment, and financial policies against their geopolitical adversaries. A rigorous cost–benefit analysis is required each time, as in the case of other policy measures. It is also important to acknowledge that global threats such as global warming or pandemics can be best tackled by well-coordinated global actions based on open markets rather than inward-oriented industrial policies or other beggar-thy-neighbor measures.

EMDEs have an even larger agenda of reforms to reduce further tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade and barriers to foreign investment, abandon import-substitution strategies, improve the rule of law, protect property rights, and strengthen their institutions and governance structures. They lack the resources to subsidize exports, import substitutions, energy prices, etc.

Trade-friendly domestic reforms and concessions in trade negotiations are not easy for obvious political and economic reasons. It takes time to see the benefits of reform, and they are dispersed among broad groups in society. At the same time, costs/sacrifices must be borne upfront by narrow groups of special interests, usually well-organized. In the ICT revolution era, when the time horizon of political decisions has shortened dramatically, it is more challenging to build a consensus around economic reforms and trade liberalization decisions than it was a few decades earlier. Nevertheless, such a political effort is needed to avoid a slippery slope towards decomposition and fragmentation of the global economy with heavy economic and social losses.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For the purpose of this essay, we use Wolf’s (2005, p. 14) definition of economic globalization as ‘the integration of economic activity across borders, through markets’. For a broader discussion of this notion, see, e.g., https://www.piie.com/microsites/globalization/what-is-globalization (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 2 | Patel et al.’s (2024) analysis, which presents the growth convergenge benefits of hyperglobalization and warns of potential global losses, is one of exceptions. |

| 3 | Sachs (2020) distinguishes seven ages of globalization, starting from the Paleolithic Age and ending with the contemporary Digital Age. His periodization is based on technical innovation and refers not only to economic integration. This essay focuses on the role of policies and regulatory regimes in economic integration (although does not abstract from technical and technological factors) and concentrates on the last 150 years. |

| 4 | For an overview of technical innovations in the late 19th and 20th centuries and their socio-economic importance—see Gordon (2016). |

| 5 | The Spanish–US war in 1898 and the Japanese–Russian war in 1904–1905 were exceptions. However, these were relatively short episodes of limited scale. In addition, Japan, Russia, and Spain played peripheral roles in the world economy at that time. |

| 6 | The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act adopted by the US Congress in June 1930 increased US import tariffs to a record-high level and triggered a global trade war because other countries retaliated (see Mitchener et al. 2022). |

| 7 | See https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact4_e.htm (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 8 | The data for EMDEs are available from 1997 only. |

| 9 | PTAs have both trade creation and trade diversion effects. If the latter is stronger than former, the net effect is negative. However, even if the net effect is positive, PTAs are the second-best solution when compared to global trade liberalization. Bhagwati (2008) calls them ‘termites in the trading system’. |

| 10 | See https://tron.trade.ec.europa.eu/investigations/ongoing (accessed on 14 June 2024). |

| 11 | See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3231 (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 12 | See, e.g., https://webapi2016.eesc.europa.eu/v1/documents/eesc-2013-06859-00-00-ac-tra-en.doc/content (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 13 | This essay does not have the ambition to offer a comprehensive assessment of policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and speculate whether there were other, better responses. The focus is only on the impact of adopted policies on protectionist sentiments and specific arguments used in the policy debate. |

| 14 | The 1990s were not free from violent conflicts, for example, in the former Yugoslavia and many corners of Africa. However, they were isolated, involved countries with negligible shares of global output, and did not negatively impact international economic cooperation and governance. |

| 15 | In 2022, China accounted for 18.4% of the world GDP in PPP terms, while Russia accounted for 2.9%. China’s share of the world exports of goods and services amounted to 11.9%, and Russia’s share amounted to 1.8% (IMF 2023, Table A, p. 99). |

| 16 | Hufbauer et al. (2022) argued that a trade liberalization package amounting to 2 percentage points of a tariff-equivalent reduction (mainly reversal of the import tariff increases of the Trump administration) could offer a one-off reduction of US inflation by ca. 1.3 percentage points. |

| 17 | The US’ objections were articulated, among others, by the US Trade Representative (2020). |

| 18 | See https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc12_e/briefing_notes_e/bfwtoreform_e.htm (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 19 | See https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/rcep (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 20 | Among EMDEs, India and Kazakhstan account for the largest budgetary support to agriculture calculated in % of gross farm receipts (IMF et al. 2022). |

References

- Allison, Graham. 2023. China’s Dominance of Solar Poses Difficult Choices for the West. Financial Times, June 22. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/fd8e7175-9423-4042-a6f7-c404afdfcda4 (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Arndt, Channing, Xinshen Diao, Paul Dorosh, Kaul Pauw, and James Thurlow. 2023. The Ukraine war and rising commodity prices: Implications for developing countries. Global Food Security 36: 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrov, Vasily, Carsten Brockhaus, Julian Hinz, Levke Jessen-Thiesen, Hendrik Mahlkow, and Patrik Svab. 2024. Navigating Trade Restrictions. WIIW Russia Monitor, February, No. 3. Available online: https://wiiw.ac.at/navigating-trade-restrictions-dlp-6810.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Bhagwati, Jagdish. 2004. In Defense of Globalization. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwati, Jagdish. 2008. Termites in the Trading System: How Preferential Agreements Undermine Free Trade. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwati, Jagdish. 2012. The Broken Legs of Global Trade. WTO Public Forum 2012, Research and Analysis, June 5. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/forums_e/public_forum12_e/art_pf12_e/art10.htm (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Bickenbach, Frank, Dirk Dohse, Rolf J. Langhammer, and Wan-Hsin Liu. 2024. Foul Play? On the Scale and Scope of Industrial Subsidies in China. Kiel Policy Brief, No. 173, April, Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Available online: https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/fis-import/bc6aff38-abfc-424a-b631-6d789e992cf9-KPB173_en.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Bilousova, Olena, Benjamin Hilgenstock, Elina Ribakova, Nataliia Shapoval, Anna Vlasyuk, and Vladyslav Vlasiuk. 2024. Challenges of Export Controls Enforcement: How Russia Continues to Import Components for Its Military Production. Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions & Kyiv School of Economics Institute, January. Available online: https://sanctions.kse.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Challenges-of-Export-Controls-Enforcement.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Bordo, Michael D., Barry Eichengreen, and Douglas A. Irwin. 1999. Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hunderd Years Ago? NBER Working Paper, No. 7195. June. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7195/w7195.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Bown, Chad P. 2023a. Modern industrial policy and the WTO. PIIE Working Papers 23–15, December. Available online: https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/2023-12/wp23-15.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Bown, Chad P. 2023b. US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart. In PIIE Charts. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, April 6, Available online: https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2019/us-china-trade-war-tariffs-date-chart (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Bown, Chad P., and Melina Kolb. 2023. Trump’s Trade War Timeline: An Up-to-Date Guide. In Trade and Investment Policy Watch. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, December 31, Available online: https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/2018/trumps-trade-war-timeline-date-guide (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Cerdeiro, Diego, Siddharth Kothari, and Dirk Muir. 2023. Harm From ‘De-Risking’ Strategies Would Reverberate Beyond China. IMF Blog, October 17. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/10/17/harm-from-de-risking-strategies-would-reverberate-beyond-china (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Chinn, Menzie D., and Hiro Ito. 2006. What Matters for Financial Development? Capital Controls, Institutions, and Interactions. Journal of Development Economics 81: 163–92. Available online: http://web.pdx.edu/~ito/w11370.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Choyleva, Diana. 2024. Xi’s Prioritization of Security Will Continue to Weigh on Growth. In China 2024: What to Watch? New York and Washington, DC: Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis, January. Available online: https://asiasociety.org/sites/default/files/2024-01/China2024_webreport_fin.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Chupilkin, Maxim, Beata Javorcik, Aleksandra Peeva, and Alexander Plekhanov. 2024. Decision to Leave: Economic Sanctions and Intermediated Trade. Paper presented at the 20th EUROFRAME Conference on Economic Policy Issues in the European Union, Kiel, Germany, June 7. Available online: https://www.euroframe.org/files/user_upload/euroframe/docs/2024/Conference/Session%20C1/EUROF24_Chupilkin_etal.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Dabrowski, Marek. 2021. Thinking Beyond the Pandemic: Monetary Policy Challenges in the Medium- to Long-Term. Paper presented at the European Parliament’s Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (Monetary Dialogue March 2021), Brussels, Belgium, March 4. PE 658.221. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/230556/CASE_formatted.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Dabrowski, Marek. 2023. A Limping Transition: The Former SOVIET Union Thirty Years On. Bruegel Essay, No. 01/2023. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/Transition%20in%20the%20FSU_essay%20140223%20HB.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Dabrowski, Marek, and Svetlana Avdasheva. 2023. Sanctions and Forces Driving to Autarky. In The Contemporary Russian Economy: A Comprehensive Analysis. Edited by Marek Dabrowski. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadush, Uri. 2023. American Protectionism. Revue d’économie Politique 133: 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadush, Uri. 2024. Rippling Out: Biden’s Tariffs on Chinese Electric Vehicles and Their Impact on Europe. Bruegel Analysis, May 16. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/rippling-out%3A-biden%E2%80%99s-tariffs-on-chinese-electric-vehicles-and-their-impact-on-europe-9985.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Dadush, Uri, and Andre Sapir. 2021. Is the European Union’s Investment Agreement with China Underrated? Bruegel Policy Contribution, April 13. Issue 09/2021. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp_attachments/PC-09-2021_.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Dadush, Uri, and Michael Baltensperger. 2019. The European Union-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement: Prospects and risks. Bruegel Policy Contribution, September 24. No. 2019-11. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp_attachments/PC-11_2019.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Darvas, Zsolt. 2018. Global Income Inequality is Declining—Largely Thanks to China and India. Bruegel Blog. April 19. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/global-income-inequality-declining-largely-thanks-china-and-india (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Darvas, Zsolt. 2024. Income Inequality Hardly Changed during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Bruegel Analysis. February 8. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/income-inequality-hardly-changed-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Daudin, Guillaume, Matthias Morys, and Kevin H. O’Rourke. 2010. Globalization, 1870–1914. In The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe. Edited by Stephen Broadberry and Kevin H. O’Rourke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (CUP), pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarais, Agathe. 2024. The Bigger Picture: The Case for an EU-Mercosur Free Trade Deal. ECFR Commentary, January 15. European Council on Foreign Relations. Available online: https://ecfr.eu/article/the-bigger-picture-the-case-for-an-eu-mercosur-free-trade-deal/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Dizaji, Sajjad F., and Mohammad R. Farzanegan. 2021. Do Sanctions Constrain Military Spending of Iran? Defence and Peace Economics 32: 125–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echandi, Roberto, Maryla Maliszewska, and Victor Steenbergen. 2022. Making the Most of the African Continental Free Trade Area: Leveraging Trade and Foreign Direct Investment to Boost Growth and Reduce Poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank, June, Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstreams/91585eee-eab1-5141-b2f0-031af56e860b/download (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Estevadeordal, Antoni. 1997. Measuring protection in the early twentieth century. European Economic History Review 1: 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2017. Commission Staff Working Document on Significant Distortions in the Economy of the People’s Republic of China for the Purposes of Trade Defence Investigations. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/api/files/SWD (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Evenett, Simon J. 2023. Corporate Subsidies & World Trade: Evidence from the Global Trade Alert Subsidy Inventory 2.0. Presentation to a Joint Webinar Convened by the Italian Society of International Law & Swiss Society of International Law, Global Trade Alert. May 9. Available online: https://gtaupload.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/Uploads/web/GTA+Subsidy+Inventory+2.0.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Fofack, Hyppolyte. 2024. The Future of African Trade in the AfCFTA Era. Brookings Commentary, February 23. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-future-of-african-trade-in-the-afcfta-era/?utm_campaign=Global%20Connection&utm_medium=email&utm_content=295710044&utm_source=hs_email (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Fouquin, Michel, and Jules Hugot. 2016. Two Centuries of Bilateral Trade and Gravity Data: 1827–2014. CEPII Working Paper, May. No. 2016-14. Available online: https://www.cepii.fr/PDF_PUB/wp/2016/wp2016-14.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Fritz, Johannes, and Simon Evenett. 2021. Subsidies and Market Access: New Data and Findings from the Global Trade Alert. VoxEU/Columns, October 25. Available online: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/subsidies-and-market-access-new-data-and-findings-global-trade-alert (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Garten, Jeffrey E. 2021. Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhart, Charles, and Manoj Pradhan. 2020. The Great Demographic Reversal: Aging Societies, Waning Inequality and Inflation Revival. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, Gita. 2023. Cold War II? Preserving Economic Cooperation Amid Geoeconomic Fragmentation. Plenary Speech by IMF First Managing Deputy Director Gita Gopinath 20th World Congress of the International Economic Association, Colombia. December 11. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/12/11/sp121123-cold-war-ii-preserving-economic-cooperation-amid-geoeconomic-fragmentation (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Gordon, Robert J. 2016. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenstock, Benjamin, Elina Ribakova, and Nataliia Shapoval. 2023. Bold Measures Are Needed as Russia’s Oil Is Slipping Beyond G7 Reach. Special Report. Kyiv School of Economics Institute, November. Available online: https://sanctions.kse.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/OPC_November2023-1.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Hufbauer, Gary C., Megan Hogan, and Yilin Wang. 2022. For inflation relief, the United States should look to trade liberalization. Policy Brief No. 22-4, Peterson Institute for International Economics. March. Available online: https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/documents/pb22-4.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Huwart, Jean-Yves, and Loic Verdier. 2013. Economic Globalisation: Origins and consequences. In OECD Insights. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. 2023. World Economic Outlook: Navigating Global Divergencies. Washington, DC: The International Monetary Fund, October, Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2023/October/English/text.ashx (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- IMF, OECD, The World Bank, and World Trade Organization. 2022. Subsidies, Trade, and International Cooperation. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Hiro, and Menzie D. Chinn. 2020. Notes on The Chinn-Ito Financial Openness Index 2018 Update. July 12. Available online: https://web.pdx.edu/~ito/Readme_kaopen2018.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- James, Harold. 2018. Deglobalization: The Rise of Disembedded Unilateralism. Annual Review of Financial Economics 10: 219–37. Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-financial-110217-022625 (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Jean, Sebastien, Ariell Reshef, Gianluca Santoni, and Vincent Vicard. 2023. Dominance on World Markets: The China Conundrum. CEPII Policy Brief, No. 2023-44, CEPII. Available online: https://www.cepii.fr/PDF_PUB/pb/2023/pb2023-44.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Kaur, Dashveenjit. 2021. Here’s What the 2021 Global Semiconductor Shortage is All About. Techwire Asia, October 13. Available online: https://techwireasia.com/2021/10/heres-what-the-2021-global-semiconductor-shortage-is-all-about/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Lee, Jong-Wha, and Ju Hyun Pyun. 2009. Does Trade Integration Contribute to Peace? Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration, No. 24. Asian Development Bank. January. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28499/wp24-trade-integration-peace.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Leonard, Carol. S. 2023. The Soviet Economy, 1918–1991. In The Contemporary Russian Economy: A Comprehensive Analysis. Edited by Marek Dabrowski. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Mark. 2024. Sunset of the Economists. China Books Review, February 1. Available online: https://chinabooksreview.com/2024/02/01/sunset-of-the-economists/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Léry Moffat, Luca, and Niclas Poitiers. 2024. Global Supply Chains: Lessons from a Decade of Disruption. Bruegel Working Paper 05/2024, March 4. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/WP%2005_0.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Maskin, Eric. 2015. Why Haven’t Global Markets Reduced Inequality in Emerging Economies? The World Bank Economic Review 29: S48–52. Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/maskin/files/world_bank_econ_rev-2015-maskin-s48-52.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- McWilliams, Ben, Giovanni Sgaravatti, Simone Tagliapietra, and Georg Zachmann. 2024. The European Union-Russia Energy Divorce: State of Play. Bruegel Analysis, February 22. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/european-union-russia-energy-divorce-state-play (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Meltzer, Allan H., and Saranna Robinson. 1989. Stability Under the Gold Standard in Practice. In Money, History, and International Finance: Essays in Honor of Anna J. Schwartz. Edited by Michael. D. Bordo. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic, Branko. 2020. Long-run evolution of global income inequality and its political meaning. Paper presented at the 8th Annual Conference on the Global Economy, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia, November 26. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchener, Kris J., Kevin H. O’Rourke, and Kirsten Wandschneider. 2022. The Smoot-Hawley Trade War. The Economic Journal 132: 2500–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morys, Matthias, Guillaume Daudin, and Kevin H. O’Rourke. 2008. Globalization 1870–1914. Economics Series Working Papers, No. 395, May, University of Oxford, Department of Economics. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/oxf/wpaper/395.html#download (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Nellis, Stephen, Karen Freifeld, and Alexandra Alper. 2022. US Aims to Hobble China’s Chip Industry with Sweeping New Export Rules. Reuters, October 10. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/technology/us-aims-hobble-chinas-chip-industry-with-sweeping-new-export-rules-2022-10-07/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- O’Rourke, Kevin. H., and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 2000. When Did Globalization Begin? NBER Working Paper, No. 7632, April. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7632/w7632.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Obstfeld, Maurice, and Alan M. Taylor. 2004. Global Capital Markets: Integration, Crisis, and Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, Lubos, and Pietro Veronesi. 2018. Inequality Aversion, Populism, and the Backlash Against Globalization. NBER Working Paper, No. 24900, August. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24900/w24900.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Patel, Dev, Justin Sandefur, and Arvind Subramanian. 2024. A Requiem for Hyperglobalization: Why the World Will Miss History’s Greatest Economic Miracle. Foreign Affairs, June 12. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/print/node/1131853 (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Peksen, Dursun. 2019. When Do Imposed Economic Sanctions Work? A Critical Review of the Sanctions Effectiveness Literature. Defence and Peace Economics 30: 635–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitiers, Niclas, and Kamil Sekut. 2024. Knowledge Spillovers and Geopolitical Challenges in Global Supply Chains. Bruegel Working Paper 03/2024, February 29. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/WP%2003_0.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Robinson, Peter, and Niall Ferguson. 2023. Cold War II: Niall Ferguson on the Emerging Conflict with China (Interview). Uncommon Knowledge, May 1, Hoover Institution. Available online: https://www.hoover.org/research/cold-war-ii-niall-ferguson-emerging-conflict-china (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Rodrik, Dani. 2011. The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. New York and London: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]