Recent Advances on Ultrasound Contrast Agents for Blood-Brain Barrier Opening with Focused Ultrasound

Abstract

:1. Introduction

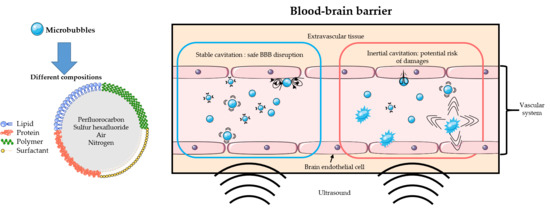

2. Recent Advances on Sono-Sensitive Agents for Ultrasound-Assisted Blood-Brain Barrier Opening

2.1. Method of Literature Search

2.2. Commercial Ultrasound Contrast Agents

2.3. Design of Specific Agents for Blood-Brain Barrier Opening

2.3.1. Bubble or Droplet?

2.3.2. Core Composition

2.3.3. Shell Composition

2.3.4. Fabrication Methods

2.3.5. Size Distribution and Concentration

2.4. Bimodal Ultrasound-MRI Contrast Agents for BBB Disruption

2.5. Drug Delivery and Targeting

2.5.1. Targeting

2.5.2. Drug and Gene Delivery

3. Discussion

3.1. Safety

3.2. Ongoing Challenges and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burgess, A.; Shah, K.; Hough, O.; Hynynen, K. Focused ultrasound-mediated drug delivery through the blood–brain barrier. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burgess, A.; Hynynen, K. Microbubble-Assisted Ultrasound for Drug Delivery in the Brain and Central Nervous System. In Therapeutic Ultrasound; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Escoffre, J.-M., Bouakaz, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 880, pp. 293–308. ISBN 978-3-319-22535-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen, K.; McDannold, N.; Vykhodtseva, N.; Jolesz, F.A. Noninvasive MR Imaging–guided Focal Opening of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Rabbits. Radiology 2001, 220, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty, B.; Larrat, B.; Van Landeghem, M.; Robic, C.; Robert, P.; Port, M.; Le Bihan, D.; Pernot, M.; Tanter, M.; Lethimonnier, F.; et al. Dynamic Study of Blood–Brain Barrier Closure after its Disruption using Ultrasound: A Quantitative Analysis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, A.; Mériaux, S.; Larrat, B. About the Marty model of blood-brain barrier closure after its disruption using focused ultrasound. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019, 64, 14NT02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, M.E.; Buch, A.; Karakatsani, M.E.; Konofagou, E.E.; Ferrera, V.P. Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Behaving Non-Human Primates via Focused Ultrasound with Systemically Administered Microbubbles. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, M.E.; Buch, A.; Sierra, C.; Karakatsani, M.E.; Chen, S.; Konofagou, E.E.; Ferrera, V.P. Long-Term Safety of Repeated Blood-Brain Barrier Opening via Focused Ultrasound with Microbubbles in Non-Human Primates Performing a Cognitive Task. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUS Foundation. Available online: https://www.fusfoundation.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Conti, A.; Magnin, R.; Gerstenmayer, M.; Tsapis, N.; Dumont, E.; Tillement, O.; Lux, F.; Le Bihan, D.; Mériaux, S.; Della Penna, S.; et al. Empirical and Theoretical Characterization of the Diffusion Process of Different Gadolinium-Based Nanoparticles within the Brain Tissue after Ultrasound-Induced Permeabilization of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2019, 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mériaux, S.; Conti, A.; Larrat, B. Assessing Diffusion in the Extra-Cellular Space of Brain Tissue by Dynamic MRI Mapping of Contrast Agent Concentrations. Front. Phys. 2018, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valdez, M.A.; Fernandez, E.; Matsunaga, T.; Erickson, R.P.; Trouard, T.P. Distribution and Diffusion of Macromolecule Delivery to the Brain via Focused Ultrasound using Magnetic Resonance and Multispectral Fluorescence Imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alli, S.; Figueiredo, C.A.; Golbourn, B.; Sabha, N.; Wu, M.Y.; Bondoc, A.; Luck, A.; Coluccia, D.; Maslink, C.; Smith, C.; et al. Brainstem blood brain barrier disruption using focused ultrasound: A demonstration of feasibility and enhanced doxorubicin delivery. J. Control. Release 2018, 281, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Adrian, D.; Kofoed, R.H.; Chan, J.W.Y.; Silburt, J.; Noroozian, Z.; Kügler, S.; Hynynen, K.; Aubert, I. Strategy to enhance transgene expression in proximity of amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Theranostics 2019, 9, 8127–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakatsani, M.E.; Wang, S.; Samiotaki, G.; Kugelman, T.; Olumolade, O.O.; Acosta, C.; Sun, T.; Han, Y.; Kamimura, H.A.S.; Jackson-Lewis, V.; et al. Amelioration of the nigrostriatal pathway facilitated by ultrasound-mediated neurotrophic delivery in early Parkinson’s disease. J. Control. Release 2019, 303, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.-H.; Liu, R.-S.; Lin, W.-L.; Yuh, Y.-S.; Lin, S.-P.; Wong, T.-T. Transcranial pulsed ultrasound facilitates brain uptake of laronidase in enzyme replacement therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis type I disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, S.J.; Shah, K.; Yeung, S.; Burgess, A.; Aubert, I.; Hynynen, K. Focused Ultrasound-Induced Neurogenesis Requires an Increase in Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; Dubey, S.; Yeung, S.; Hough, O.; Eterman, N.; Aubert, I.; Hynynen, K. Alzheimer Disease in a Mouse Model: MR Imaging–guided Focused Ultrasound Targeted to the Hippocampus Opens the Blood-Brain Barrier and Improves Pathologic Abnormalities and Behavior. Radiology 2014, 273, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamsam, L.; Johnson, E.; Connolly, I.D.; Wintermark, M.; Hayden Gephart, M. A review of potential applications of MR-guided focused ultrasound for targeting brain tumor therapy. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conti, A.; Kamimura, H.A.; Novell, A.; Duggento, A.; Toschi, N. Magnetic Resonance Methods for Focused ultrasound-induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening. Front. Phys. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, H.A.; Flament, J.; Valette, J.; Cafarelli, A.; Aron Badin, R.; Hantraye, P.; Larrat, B. Feedback control of microbubble cavitation for ultrasound-mediated blood–brain barrier disruption in non-human primates under magnetic resonance guidance. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2019, 39, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamimura, H.A.S.; Wang, S.; Wu, S.-Y.; Karakatsani, M.E.; Acosta, C.; Carneiro, A.A.O.; Konofagou, E.E. Chirp- and random-based coded ultrasonic excitation for localized blood-brain barrier opening. Phys. Med. Biol. 2015, 60, 7695–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novell, A.; Kamimura, H.A.S.; Cafarelli, A.; Gerstenmayer, M.; Flament, J.; Valette, J.; Agou, P.; Conti, A.; Selingue, E.; Aron Badin, R.; et al. A new safety index based on intrapulse monitoring of ultra-harmonic cavitation during ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening procedures. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Caskey, C.F.; Ferrara, K.W. Ultrasound contrast microbubbles in imaging and therapy: Physical principles and engineering. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009, 54, R27–R57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentacker, I.; De Cock, I.; Deckers, R.; De Smedt, S.C.; Moonen, C.T.W. Understanding ultrasound induced sonoporation: Definitions and underlying mechanisms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 72, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hwang, J.H.; Tu, J.; Brayman, A.A.; Matula, T.J.; Crum, L.A. Correlation between inertial cavitation dose and endothelial cell damage in vivo. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006, 32, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Han, H.; Lee, M.; Lee, S.; Yoo, H.; Chang, J.H.; Kim, H. Microbubbles used for contrast enhanced ultrasound and theragnosis: A review of principles to applications. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2017, 7, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Pople, C.B.; Lea-Banks, H.; Abrahao, A.; Davidson, B.; Suppiah, S.; Vecchio, L.M.; Samuel, N.; Mahmud, F.; Hynynen, K.; et al. Safety and efficacy of focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening, an integrative review of animal and human studies. J. Control. Release 2019, 309, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, H.A.S.; Aurup, C.; Bendau, E.V.; Saharkhiz, N.; Kim, M.G.; Konofagou, E.E. Iterative Curve Fitting of the Bioheat Transfer Equation for Thermocouple-Based Temperature Estimation In Vitro and In~ Vivo. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2020, 67, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, K.; Vos, H.J.; Versluis, M.; de Jong, N. Acoustic behavior of microbubbles and implications for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 72, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delalande, A.; Bastié, C.; Pigeon, L.; Manta, S.; Lebertre, M.; Mignet, N.; Midoux, P.; Pichon, C. Cationic gas-filled microbubbles for ultrasound-based nucleic acids delivery. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, BSR20160619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stride, E.; Segers, T.; Lajoinie, G.; Cherkaoui, S.; Bettinger, T.; Versluis, M.; Borden, M. Microbubble Agents: New Directions. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 1326–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, A.; Blum, N.T.; Goodwin, A.P. Colloids, nanoparticles, and materials for imaging, delivery, ablation, and theranostics by focused ultrasound (FUS). Theranostics 2019, 9, 2572–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Fix, S.M.; Arena, C.B.; Chen, C.C.; Zheng, W.; Olumolade, O.O.; Papadopoulou, V.; Novell, A.; Dayton, P.A.; Konofagou, E.E. Focused ultrasound-facilitated brain drug delivery using optimized nanodroplets: Vaporization efficiency dictates large molecular delivery. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D.G.; Price, R.J. Recent Advances in the Use of Focused Ultrasound for Magnetic Resonance Image-Guided Therapeutic Nanoparticle Delivery to the Central Nervous System. Front. Pharm. 2019, 10, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X. Current Strategies for Brain Drug Delivery. Theranostics 2018, 8, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Kong, C.; Cho, J.S.; Lee, J.; Koh, C.S.; Yoon, M.-S.; Na, Y.C.; Chang, W.S.; Chang, J.W. Focused ultrasound–mediated noninvasive blood-brain barrier modulation: Preclinical examination of efficacy and safety in various sonication parameters. Neurosurg. Focus 2018, 44, E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.-K.; Chu, P.-C.; Chai, W.-Y.; Kang, S.-T.; Tsai, C.-H.; Fan, C.-H.; Yeh, C.-K.; Liu, H.-L. Characterization of Different Microbubbles in Assisting Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bing, C.; Hong, Y.; Hernandez, C.; Rich, M.; Cheng, B.; Munaweera, I.; Szczepanski, D.; Xi, Y.; Bolding, M.; Exner, A.; et al. Characterization of different bubble formulations for blood-brain barrier opening using a focused ultrasound system with acoustic feedback control. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.-K.Y.; Pham, B.; Zong, Y.; Perez, C.; Maris, D.O.; Hemphill, A.; Miao, C.H.; Matula, T.J.; Mourad, P.D.; Wei, H.; et al. Microbubbles and ultrasound increase intraventricular polyplex gene transfer to the brain. J. Control. Release 2016, 231, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDannold, N.; Zhang, Y.; Supko, J.G.; Power, C.; Sun, T.; Peng, C.; Vykhodtseva, N.; Golby, A.J.; Reardon, D.A. Acoustic feedback enables safe and reliable carboplatin delivery across the blood-brain barrier with a clinical focused ultrasound system and improves survival in a rat glioma model. Theranostics 2019, 9, 6284–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.; Lee, W.; Chen, E.; Lee, J.E.; Croce, P.; Cammalleri, A.; Foley, L.; Tsao, A.L.; Yoo, S.-S. Localized Blood–Brain Barrier Opening in Ovine Model Using Image-Guided Transcranial Focused Ultrasound. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019, 45, 2391–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhima, K.; Nabbouh, F.; Hynynen, K.; Aubert, I.; Tandon, A. Noninvasive delivery of an α-synuclein gene silencing vector with magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound: Noninvasive Knockdown of Brain α-Syn. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Askoxylakis, V.; Guo, Y.; Datta, M.; Kloepper, J.; Ferraro, G.B.; Bernabeu, M.O.; Fukumura, D.; McDannold, N.; Jain, R.K. Mechanisms of enhanced drug delivery in brain metastases with focused ultrasound-induced blood–tumor barrier disruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8717–E8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pelekanos, M.; Leinenga, G.; Odabaee, M.; Odabaee, M.; Saifzadeh, S.; Steck, R.; Götz, J. Establishing sheep as an experimental species to validate ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening for potential therapeutic interventions. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2583–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Aryal, M.; Vykhodtseva, N.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; McDannold, N. Evaluation of permeability, doxorubicin delivery, and drug retention in a rat brain tumor model after ultrasound-induced blood-tumor barrier disruption. J. Control. Release 2017, 250, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alkins, R.; Burgess, A.; Kerbel, R.; Wels, W.S.; Hynynen, K. Early treatment of HER2-amplified brain tumors with targeted NK-92 cells and focused ultrasound improves survival. Neuro-Oncol. 2016, 18, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coluccia, D.; Figueiredo, C.A.; Wu, M.Y.; Riemenschneider, A.N.; Diaz, R.; Luck, A.; Smith, C.; Das, S.; Ackerley, C.; O’Reilly, M.; et al. Enhancing glioblastoma treatment using cisplatin-gold-nanoparticle conjugates and targeted delivery with magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhima, K.; Markham-Coultes, K.; Nedev, H.; Heinen, S.; Saragovi, H.U.; Hynynen, K.; Aubert, I. Focused ultrasound delivery of a selective TrkA agonist rescues cholinergic function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noroozian, Z.; Xhima, K.; Huang, Y.; Kaspar, B.K.; Kügler, S.; Hynynen, K.; Aubert, I. MRI-Guided Focused Ultrasound for Targeted Delivery of rAAV to the Brain. In Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors; Castle, M.J., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1950, pp. 177–197. ISBN 978-1-4939-9138-9. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Alkins, R.; Schwartz, M.L.; Hynynen, K. Opening the Blood-Brain Barrier with MR Imaging–guided Focused Ultrasound: Preclinical Testing on a Trans–Human Skull Porcine Model. Radiology 2017, 282, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J.; Kong, C.; Lee, J.; Choi, B.Y.; Sim, J.; Koh, C.S.; Park, M.; Na, Y.C.; Suh, S.W.; Chang, W.S.; et al. Focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening improves adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function in a cholinergic degeneration dementia rat model. Alzheimers Res. 2019, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, B.; Huh, H.; Lee, E.; Han, M.; Park, J. An advanced focused ultrasound protocol improves the blood-brain barrier permeability and doxorubicin delivery into the rat brain. J. Control. Release 2019, 315, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, M.C.; Sherwood, J.; Bartley, A.F.; Whitsitt, Q.A.; Lee, M.; Willoughby, W.R.; Dobrunz, L.E.; Bao, Y.; Lubin, F.D.; Bolding, M. Focused ultrasound blood brain barrier opening mediated delivery of MRI-visible albumin nanoclusters to the rat brain for localized drug delivery with temporal control. J. Control. Release 2020, 324, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alecou, T.; Giannakou, M.; Damianou, C. Amyloid β Plaque Reduction With Antibodies Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier, Which Was Opened in 3 Sessions of Focused Ultrasound in a Rabbit Model: Amyloid β Plaque Reduction With Focused Ultrasound. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017, 36, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chu, P.-C.; Chai, W.-Y.; Tsai, C.-H.; Kang, S.-T.; Yeh, C.-K.; Liu, H.-L. Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening: Association with Mechanical Index and Cavitation Index Analyzed by Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic-Resonance Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, F.-Y.; Chang, W.-Y.; Lin, W.-T.; Hwang, J.-J.; Chien, Y.-C.; Wang, H.-E.; Tsai, M.-L. Focused ultrasound enhanced molecular imaging and gene therapy for multifusion reporter gene in glioma-bearing rat model. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 36260–36268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Hsieh, H.-Y.; Pitt, W.G.; Huang, C.-Y.; Tseng, I.-C.; Yeh, C.-K.; Wei, K.-C.; Liu, H.-L. Focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening for non-viral, non-invasive, and targeted gene delivery. J. Control. Release 2015, 212, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horodyckid, C.; Canney, M.; Vignot, A.; Boisgard, R.; Drier, A.; Huberfeld, G.; François, C.; Prigent, A.; Santin, M.D.; Adam, C.; et al. Safe long-term repeated disruption of the blood-brain barrier using an implantable ultrasound device: A multiparametric study in a primate model. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beccaria, K.; Canney, M.; Goldwirt, L.; Fernandez, C.; Piquet, J.; Perier, M.-C.; Lafon, C.; Chapelon, J.-Y.; Carpentier, A. Ultrasound-induced opening of the blood-brain barrier to enhance temozolomide and irinotecan delivery: An experimental study in rabbits. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morse, S.V.; Pouliopoulos, A.N.; Chan, T.G.; Copping, M.J.; Lin, J.; Long, N.J.; Choi, J.J. Rapid Short-pulse Ultrasound Delivers Drugs Uniformly across the Murine Blood-Brain Barrier with Negligible Disruption. Radiology 2019, 291, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Dmello, C.; Chen, L.; Arrieta, V.A.; Gonzalez-Buendia, E.; Kane, J.R.; Magnusson, L.P.; Baran, A.; James, C.D.; Horbinski, C.; et al. Ultrasound-mediated Delivery of Paclitaxel for Glioma: A Comparative Study of Distribution, Toxicity, and Efficacy of Albumin-bound Versus Cremophor Formulations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.-Y.; Chu, P.-C.; Tsai, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Yang, H.-W.; Lai, H.-Y.; Liu, H.-L. Image-Guided Focused-Ultrasound CNS Molecular Delivery: An Implementation via Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic-Resonance Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xi, X.-P.; Zong, Y.-J.; Ji, Y.-H.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.-S. Experiment research of focused ultrasound combined with drug and microbubble for treatment of central nervous system leukemia. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 5424–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morse, S.V.; Boltersdorf, T.; Harriss, B.I.; Chan, T.G.; Baxan, N.; Jung, H.S.; Pouliopoulos, A.N.; Choi, J.J.; Long, N.J. Neuron labeling with rhodamine-conjugated Gd-based MRI contrast agents delivered to the brain via focused ultrasound. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2659–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, Y.; Huang, H.-Y.; Liao, W.-H.; Huang, A.P.-H.; Hsiao, M.-Y.; Wu, C.-H.; Liu, H.-L.; Inserra, C.; Chen, W.-S. A Single High-Intensity Shock Wave Pulse With Microbubbles Opens the Blood-Brain Barrier in Rats. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.L.; Novell, A.; Tournier, N.; Gerstenmayer, M.; Schweitzer-Chaput, A.; Mateos, C.; Jego, B.; Bouleau, A.; Nozach, H.; Winkeler, A.; et al. Impact of blood-brain barrier permeabilization induced by ultrasound associated to microbubbles on the brain delivery and kinetics of cetuximab: An immunoPET study using 89Zr-cetuximab. J. Control. Release 2020, 328, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Xie, C.; Zhang, W.; Cai, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, Y. Experimental mouse model of NMOSD produced by facilitated brain delivery of NMO-IgG by microbubble-enhanced low-frequency ultrasound in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis mice. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 46, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, D.; Maruyama, T.; Unga, J.; Hagiwara, F.; Munakata, L.; Kageyama, S.; Shima, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Suzuki, R. Effects of encapsulated gas on stability of lipid-based microbubbles and ultrasound-triggered drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2019, 311–312, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Power, C.; Alexander, P.M.; Sutton, J.T.; Aryal, M.; Vykhodtseva, N.; Miller, E.L.; McDannold, N.J. Closed-loop control of targeted ultrasound drug delivery across the blood–brain/tumor barriers in a rat glioma model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10281–E10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aryal, M.; Papademetriou, I.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Power, C.; McDannold, N.; Porter, T. MRI Monitoring and Quantification of Ultrasound-Mediated Delivery of Liposomes Dually Labeled with Gadolinium and Fluorophore through the Blood-Brain Barrier. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019, 45, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Adams, M.S.; Jones, P.D.; Diederich, C.J.; Verkman, A.S. Noninvasive, Targeted Creation of Neuromyelitis Optica Pathology in AQP4-IgG Seropositive Rats by Pulsed Focused Ultrasound. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 78, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavarache, M.A.; Petersen, N.; Jurgens, E.M.; Milstein, E.R.; Rosenfeld, Z.B.; Ballon, D.J.; Kaplitt, M.G. Safe and stable noninvasive focal gene delivery to the mammalian brain following focused ultrasound. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 130, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobus, T.; Zervantonakis, I.K.; Zhang, Y.; McDannold, N.J. Growth inhibition in a brain metastasis model by antibody delivery using focused ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier disruption. J. Control. Release 2016, 238, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulik, R.S.; Bing, C.; Ladouceur-Wodzak, M.; Munaweera, I.; Chopra, R.; Corbin, I.R. Localized delivery of low-density lipoprotein docosahexaenoic acid nanoparticles to the rat brain using focused ultrasound. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Song, K.-H.; Fan, A.C.; Hinkle, J.J.; Newman, J.; Borden, M.A.; Harvey, B.K. Microbubble gas volume: A unifying dose parameter in blood-brain barrier opening by focused ultrasound. Theranostics 2017, 7, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R.K.; Hallam, K.A.; Donnelly, E.M.; Emelianov, S.Y. Photoacoustic imaging of gold nanorods in the brain delivered via microbubble-assisted focused ultrasound: A tool for in vivo molecular neuroimaging. Laser Phys. Lett. 2019, 16, 025603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papachristodoulou, A.; Signorell, R.D.; Werner, B.; Brambilla, D.; Luciani, P.; Cavusoglu, M.; Grandjean, J.; Silginer, M.; Rudin, M.; Martin, E.; et al. Chemotherapy sensitization of glioblastoma by focused ultrasound-mediated delivery of therapeutic liposomes. J. Control. Release 2019, 295, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Hsieh, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-M.; Wu, S.-R.; Tsai, C.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hua, M.-Y.; Wei, K.-C.; Yeh, C.-K.; Liu, H.-L. Non-invasive, neuron-specific gene therapy by focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in Parkinson’s disease mouse model. J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åslund, A.K.O.; Snipstad, S.; Healey, A.; Kvåle, S.; Torp, S.H.; Sontum, P.C.; de Lange Davies, C.; van Wamel, A. Efficient Enhancement of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Using Acoustic Cluster Therapy (ACT). Theranostics 2017, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhao, G.; Huang, N.; Tan, Y.; Pi, L.; Huang, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. PEGylated PLGA-based phase shift nanodroplets combined with focused ultrasound for blood brain barrier opening in rats. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38927–38936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mead, B.P.; Mastorakos, P.; Suk, J.S.; Klibanov, A.L.; Hanes, J.; Price, R.J. Targeted gene transfer to the brain via the delivery of brain-penetrating DNA nanoparticles with focused ultrasound. J. Control. Release 2016, 223, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timbie, K.F.; Afzal, U.; Date, A.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Wilson Miller, G.; Suk, J.S.; Hanes, J.; Price, R.J. MR image-guided delivery of cisplatin-loaded brain-penetrating nanoparticles to invasive glioma with focused ultrasound. J. Control. Release 2017, 263, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, C.T.; Mead, B.P.; Negron, K.; Kim, N.; Garrison, W.J.; Miller, G.W.; Kingsmore, K.M.; Thim, E.A.; Song, J.; Munson, J.M.; et al. Augmentation of brain tumor interstitial flow via focused ultrasound promotes brain-penetrating nanoparticle dispersion and transfection. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghirov, H.; Snipstad, S.; Sulheim, E.; Berg, S.; Hansen, R.; Thorsen, F.; Mørch, Y.; Davies, C.D.L.; Åslund, A.K.O. Ultrasound-mediated delivery and distribution of polymeric nanoparticles in the normal brain parenchyma of a metastatic brain tumour model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Åslund, A.K.O.; Berg, S.; Hak, S.; Mørch, Ý.; Torp, S.H.; Sandvig, A.; Widerøe, M.; Hansen, R.; de Lange Davies, C. Nanoparticle delivery to the brain—By focused ultrasound and self-assembled nanoparticle-stabilized microbubbles. J. Control. Release 2015, 220, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Xie, W.; Huang, A.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Microbubbles in combination with focused ultrasound for the delivery of quercetin-modified sulfur nanoparticles through the blood brain barrier into the brain parenchyma and relief of endoplasmic reticulum stress to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 6498–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.-N.; Golombek, S.K.; Baues, M.; Dasgupta, A.; Drude, N.; Rix, A.; Rommel, D.; von Stillfried, S.; Appold, L.; Pola, R.; et al. Multimodal and multiscale optical imaging of nanomedicine delivery across the blood-brain barrier upon sonopermeation. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1948–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chiang, C.-F.; Wu, S.-K.; Chen, L.-F.; Hsieh, W.-Y.; Lin, W.-L. Targeting microbubbles-carrying TGFβ1 inhibitor combined with ultrasound sonication induce BBB/BTB disruption to enhance nanomedicine treatment for brain tumors. J. Control. Release 2015, 211, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Wu, S.-R.; Chen, C.-M.; Liu, H.-L. Ultrasound-responsive neurotrophic factor-loaded microbubble- liposome complex: Preclinical investigation for Parkinson’s disease treatment. J. Control. Release 2020, 321, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-W.; Hwang, K.; Jin, J.; Cho, A.-S.; Kim, T.Y.; Hwang, S.I.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, C.-Y. Ultrasound-sensitizing nanoparticle complex for overcoming the blood-brain barrier: An effective drug delivery system. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3743–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ilovitsh, T.; Ilovitsh, A.; Foiret, J.; Caskey, C.F.; Kusunose, J.; Fite, B.Z.; Zhang, H.; Mahakian, L.M.; Tam, S.; Butts-Pauly, K.; et al. Enhanced microbubble contrast agent oscillation following 250 kHz insonation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Chen, C.C.; Tung, Y.-S.; Olumolade, O.O.; Konofagou, E.E. Effects of the microbubble shell physicochemical properties on ultrasound-mediated drug delivery to the brain. J. Control. Release 2015, 212, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Aurup, C.; Sanchez, C.S.; Grondin, J.; Zheng, W.; Kamimura, H.; Ferrera, V.P.; Konofagou, E.E. Efficient Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Primates with Neuronavigation-Guided Ultrasound and Real-Time Acoustic Mapping. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakatsani, M.E.; Samiotaki, G.; Downs, M.E.; Ferrera, V.P.; Konofagou, E.E. Targeting Effects on the Volume of the Focused Ultrasound Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Non-Human Primates in vivo. 2017, 64, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samiotaki, G.; Karakatsani, M.E.; Buch, A.; Papadopoulos, S.; Wu, S.Y.; Jambawalikar, S.; Konofagou, E.E. Pharmacokinetic analysis and drug delivery efficiency of the focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening in non-human primates. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2017, 37, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sierra, C.; Acosta, C.; Chen, C.; Wu, S.-Y.; Karakatsani, M.E.; Bernal, M.; Konofagou, E.E. Lipid microbubbles as a vehicle for targeted drug delivery using focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 1236–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Karakatsani, M.E.; Fung, C.; Sun, T.; Acosta, C.; Konofagou, E. Direct brain infusion can be enhanced with focused ultrasound and microbubbles. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, H.; Bertram, E.H.; Aubry, J.-F.; Lopes, M.-B.; Roy, J.; Dumont, E.; Xie, M.; Zuo, Z.; Klibanov, A.L.; et al. Non-Invasive, Focal Disconnection of Brain Circuitry Using Magnetic Resonance-Guided Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound to Deliver a Neurotoxin. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 42, 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakatsani, M.E.; Kugelman, T.; Ji, R.; Murillo, M.; Wang, S.; Niimi, Y.; Small, S.A.; Duff, K.E.; Konofagou, E.E. Unilateral Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening Reduces Phosphorylated Tau from The rTg4510 Mouse Model. Theranostics 2019, 9, 5396–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, D.; Laforest, R.; Williamson, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Cavitation dose painting for focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ye, D.; Sultan, D.; Zhang, X.; Yue, Y.; Heo, G.S.; Kothapalli, S.V.V.N.; Luehmann, H.; Tai, Y.; Rubin, J.B.; Liu, Y.; et al. Focused ultrasound-enabled delivery of radiolabeled nanoclusters to the pons. J. Control. Release 2018, 283, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliopoulos, A.N.; Jimenez, D.A.; Frank, A.; Robertson, A.; Zhang, L.; Kline-Schoder, A.R.; Bhaskar, V.; Harpale, M.; Caso, E.; Papapanou, N.; et al. Temporal Stability of Lipid-Shelled Microbubbles During Acoustically-Mediated Blood-Brain Barrier Opening. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan-Acosta, L.; Sierra, C.; Leppert, A.; Pouliopoulos, A.N.; Kwon, N.; Noel, R.L.; Tambaro, S.; Presto, J.; Nilsson, P.; Konofagou, E.E.; et al. Recombinant BRICHOS chaperone domains delivered to mouse brain parenchyma by focused ultrasound and microbubbles are internalized by hippocampal and cortical neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 105, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.-L.; Ting, C.-Y.; Hsu, P.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liao, E.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chan, H.-L.; Chiang, C.-S.; Liu, H.-L.; et al. Angiogenesis-targeting microbubbles combined with ultrasound-mediated gene therapy in brain tumors. J. Control. Release 2017, 255, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Fan, C.-H.; Chiu, N.-H.; Ho, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-C.; Yeh, C.-K. Targeted delivery of engineered auditory sensing protein for ultrasound neuromodulation in the brain. Theranostics 2020, 10, 3546–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.-H.; Wang, T.-W.; Hsieh, Y.-K.; Wang, C.-F.; Gao, Z.; Kim, A.; Nagasaki, Y.; Yeh, C.-K. Enhancing Boron Uptake in Brain Glioma by a Boron-Polymer/Microbubble Complex with Focused Ultrasound. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11144–11156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.-H.; Chang, E.-L.; Ting, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liao, E.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chan, H.-L.; Wei, K.-C.; Yeh, C.-K. Folate-conjugated gene-carrying microbubbles with focused ultrasound for concurrent blood-brain barrier opening and local gene delivery. Biomaterials 2016, 106, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Bing, C.; Xi, Y.; Shah, B.; Exner, A.A.; Chopra, R. Influence of Nanobubble Concentration on Blood–Brain Barrier Opening Using Focused Ultrasound Under Real-Time Acoustic Feedback Control. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2019, 45, 2174–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fan, C.-H.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Ting, C.-Y.; Ho, Y.-J.; Hsu, P.-H.; Liu, H.-L.; Yeh, C.-K. Ultrasound/Magnetic Targeting with SPIO-DOX-Microbubble Complex for Image-Guided Drug Delivery in Brain Tumors. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Huang, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Tan, Y.; Huang, N.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Y. Targeted shRNA-loaded liposome complex combined with focused ultrasound for blood brain barrier disruption and suppressing glioma growth. Cancer Lett. 2018, 418, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.-H.; Ting, C.-Y.; Lin, C.; Chan, H.-L.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Liu, H.-L.; Yeh, C.-K. Noninvasive, Targeted and Non-Viral Ultrasound-Mediated GDNF-Plasmid Delivery for Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Cai, X.; Guo, R.; Wang, P.; Wu, L.; Yin, T.; Liao, S.; Lu, Z. Treatment of Parkinson’s disease in rats by Nrf2 transfection using MRI-guided focused ultrasound delivery of nanomicrobubbles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Liu, R.; Sun, S.; Ma, D.; Liang, X.; Wang, S. Phosphatidylserine-microbubble targeting-activated microglia/macrophage in inflammation combined with ultrasound for breaking through the blood–brain barrier. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yan, F.; Liang, X.; Wu, M.; Shen, Y.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Zou, G.; Jiang, P.; Tang, C.; et al. Localized delivery of curcumin into brain with polysorbate 80-modified cerasomes by ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction for improved Parkinson’s disease therapy. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2264–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Yan, F.; Hong, G. Noninvasive and Local Delivery of Adenoviral-Mediated Herpes Simplex Virus Thymidine Kinase to Treat Glioma Through Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Rats. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2018, 14, 2031–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Lv, Q.; Xie, M. Blood-brain barrier disruption induced by diagnostic ultrasound combined with microbubbles in mice. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 4897–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shen, Y.; Pi, Z.; Yan, F.; Yeh, C.-K.; Zeng, X.; Diao, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H. Enhanced delivery of paclitaxel liposomes using focused ultrasound with microbubbles for treating nude mice bearing intracranial glioblastoma xenografts. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 5613–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhu, Q.; Hua, X.; Xia, H.; Tan, K.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z. Unilateral Opening of Rat Blood-Brain Barrier Assisted by Diagnostic Ultrasound Targeted Microbubbles Destruction. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shen, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, G.; Chin, C.T.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Dan, G. Delivery of Liposomes with Different Sizes to Mice Brain after Sonication by Focused Ultrasound in the Presence of Microbubbles. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2016, 42, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhu, Q.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; He, Y.; Tan, X.; Xu, Y. Low intensity ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction assists MSCs delivery and improves neural function in brain ischaemic rats. J. Drug Target. 2020, 28, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, D.G.; Turpin, F.; Mohamed, A.Z.; Zong, F.; Pandit, R.; Pelekanos, M.; Nasrallah, F.; Sah, P.; Bartlett, P.F.; Götz, J. Multimodal analysis of aged wild-type mice exposed to repeated scanning ultrasound treatments demonstrates long-term safety. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6233–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, K.; Geng, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X. Tumor targeting DVDMS-nanoliposomes for an enhanced sonodynamic therapy of gliomas. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Z.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zeng, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, T.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; Chen, S.; Chen, X. Sonodynamic Therapy on Intracranial Glioblastoma Xenografts Using Sinoporphyrin Sodium Delivered by Ultrasound with Microbubbles. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omata, D.; Hagiwara, F.; Munakata, L.; Shima, T.; Kageyama, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Azuma, T.; Takagi, S.; Seki, K.; Maruyama, K.; et al. Characterization of Brain-Targeted Drug Delivery Enhanced by a Combination of Lipid-Based Microbubbles and Non-Focused Ultrasound. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 2827–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Huang, R.-Y.; Liao, E.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Ho, Y.-J.; Chang, C.-W.; Chan, H.-L.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Fan, C.-H.; et al. A preliminary study of Parkinson’s gene therapy via sono-magnetic sensing gene vector for conquering extra/intracellular barriers in mice. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qu, F.; Wang, P.; Zhang, K.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X. Manipulation of Mitophagy by “All-in-One” nanosensitizer augments sonodynamic glioma therapy. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1413–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.-H.; Harvey, B.K.; Borden, M.A. State-of-the-art of microbubble-assisted blood-brain barrier disruption. Theranostics 2018, 8, 4393–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea-Banks, H.; O’Reilly, M.A.; Hynynen, K. Ultrasound-responsive droplets for therapy: A review. J. Control. Release 2019, 293, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boissenot, T.; Bordat, A.; Fattal, E.; Tsapis, N. Ultrasound-triggered drug delivery for cancer treatment using drug delivery systems: From theoretical considerations to practical applications. J. Control. Release 2016, 241, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheeran, P.S.; Yoo, K.; Williams, R.; Yin, M.; Foster, F.S.; Burns, P.N. More Than Bubbles: Creating Phase-Shift Droplets from Commercially Available Ultrasound Contrast Agents. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.S.; Luois, S.H.; Mullin, L.B.; Matsunaga, T.O.; Dayton, P.A. Design of ultrasonically-activatable nanoparticles using low boiling point perfluorocarbons. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3262–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Y. Application of acoustic droplet vaporization in ultrasound therapy. J. Ultrasound 2015, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.C.; Sheeran, P.S.; Wu, S.-Y.; Olumolade, O.O.; Dayton, P.A.; Konofagou, E.E. Targeted drug delivery with focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening using acoustically-activated nanodroplets. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shpak, O.; Verweij, M.; Vos, H.J.; de Jong, N.; Lohse, D.; Versluis, M. Acoustic droplet vaporization is initiated by superharmonic focusing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ammi, A.Y.; Cleveland, R.O.; Mamou, J.; Wang, G.I.; Bridal, S.L.; O’Brien, W.D. Ultrasonic contrast agent shell rupture detected by inertial cavitation and rebound signals. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2006, 53, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borden, M.A.; Song, K.-H. Reverse engineering the ultrasound contrast agent. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 262, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krafft, M.P.; Riess, J.G. Perfluorocarbons: Life sciences and biomedical usesDedicated to the memory of Professor Guy Ourisson, a true RENAISSANCE man. J. Polym. Sci. Part. Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.S.; Dayton, P.A. Phase-Change Contrast Agents for Imaging and Therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 2152–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirsi, S.R.; Borden, M.A. Microbubble compositions, properties and biomedical applications. Bubble Sci. Eng. Technol. 2009, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borden, M.A. Lipid-Coated Nanodrops and Microbubbles. In Handbook of Ultrasonics and Sonochemistry; Ashokkumar, M., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2015; pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-981-287-470-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran, P.S.; Matsuura, N.; Borden, M.A.; Williams, R.; Matsunaga, T.O.; Burns, P.N.; Dayton, P.A. Methods of Generating Submicrometer Phase-Shift Perfluorocarbon Droplets for Applications in Medical Ultrasonography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2017, 64, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirsi, S.; Feshitan, J.; Kwan, J.; Homma, S.; Borden, M. Effect of Microbubble Size on Fundamental Mode High Frequency Ultrasound Imaging in Mice. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2010, 36, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chomas, J.E.; Dayton, P.; May, D.; Ferrara, K. Threshold of fragmentation for ultrasonic contrast agents. J. Biomed. Opt. 2001, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.J.; Feshitan, J.A.; Baseri, B.; Wang, S.; Tung, Y.-S.; Borden, M.A.; Konofagou, E.E. Microbubble-Size Dependence of Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood–Brain Barrier Opening in Mice In Vivo. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morfin, J.-F.; Beloeil, J.-C.; Tóth, É. Agents de Contraste pour l’IRM. 2014, 23. Available online: https://www.techniques-ingenieur.fr/base-documentaire/sciences-fondamentales-th8/chimie-organique-et-minerale-42108210/agents-de-contraste-pour-l-irm-af6818/ (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Kogan, P.; Gessner, R.C.; Dayton, P.A. Microbubbles in imaging: Applications beyond ultrasound. Bubble Sci. Eng. Technol. 2010, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, J.S.; Chow, A.M.; Guo, H.; Wu, E.X. Microbubbles as a novel contrast agent for brain MRI. NeuroImage 2009, 46, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, A.-H.; Liu, H.-L.; Su, C.-H.; Hua, M.-Y.; Yang, H.-W.; Weng, Y.-T.; Hsu, P.-H.; Huang, S.-M.; Wu, S.-Y.; Wang, H.-E.; et al. Paramagnetic perfluorocarbon-filled albumin-(Gd-DTPA) microbubbles for the induction of focused-ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening and concurrent MR and ultrasound imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2012, 57, 2787–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapoport, N.; Nam, K.-H.; Gupta, R.; Gao, Z.; Mohan, P.; Payne, A.; Todd, N.; Liu, X.; Kim, T.; Shea, J.; et al. Ultrasound-mediated tumor imaging and nanotherapy using drug loaded, block copolymer stabilized perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions. J. Control. Release 2011, 153, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timbie, K.F.; Mead, B.P.; Price, R.J. Drug and gene delivery across the blood–brain barrier with focused ultrasound. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, Z.; Sheng, Z.; Yan, F. Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain-Barrier Opening Enhances Anticancer Efficacy in the Treatment of Glioblastoma: Current Status and Future Prospects. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki Ghali, M.G.; Srinivasan, V.M.; Kan, P. Focused Ultrasonography-Mediated Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in the Enhancement of Delivery of Brain Tumor Therapies. World Neurosurg. 2019, 131, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Ferraro, G.B.; Jain, R.K. The blood–brain barrier and blood–tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, C.; Ongaro, E.; Bolzonello, S.; Guardascione, M.; Fasola, G.; Aprile, G. Clinical advances in the development of novel VEGFR2 inhibitors. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, D.; Hynynen, K. Acute Inflammatory Response Following Increased Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Induced by Focused Ultrasound is Dependent on Microbubble Dose. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3989–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, A.; Canney, M.; Vignot, A.; Reina, V.; Beccaria, K.; Horodyckid, C.; Karachi, C.; Leclercq, D.; Lafon, C.; Chapelon, J.-Y.; et al. Clinical trial of blood-brain barrier disruption by pulsed ultrasound. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 343re2-343re2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahao, A.; Meng, Y.; Llinas, M.; Huang, Y.; Hamani, C.; Mainprize, T.; Aubert, I.; Heyn, C.; Black, S.E.; Hynynen, K.; et al. First-in-human trial of blood–brain barrier opening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lipsman, N.; Meng, Y.; Bethune, A.J.; Huang, Y.; Lam, B.; Masellis, M.; Herrmann, N.; Heyn, C.; Aubert, I.; Boutet, A.; et al. Blood–brain barrier opening in Alzheimer’s disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mainprize, T.; Lipsman, N.; Huang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Bethune, A.; Ironside, S.; Heyn, C.; Alkins, R.; Trudeau, M.; Sahgal, A.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Primary Brain Tumors with Non-invasive MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound: A Clinical Safety and Feasibility Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Idbaih, A.; Canney, M.; Belin, L.; Desseaux, C.; Vignot, A.; Bouchoux, G.; Asquier, N.; Law-Ye, B.; Leclercq, D.; Bissery, A.; et al. Safety and Feasibility of Repeated and Transient Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption by Pulsed Ultrasound in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3793–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, K.-T.; Lin, Y.-J.; Chai, W.-Y.; Lin, C.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Kuo, J.S.; Liu, H.-L.; Wei, K.-C. Neuronavigation-guided focused ultrasound (NaviFUS) for transcranial blood-brain barrier opening in recurrent glioblastoma patients: Clinical trial protocol. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, D.; Lakshmanan, A.; Abedi, M.; Bar-Zion, A.; Farhadi, A.; Lu, G.J.; Szablowski, J.O.; Wu, D.; Yoo, S.; Shapiro, M.G. Biomolecular Ultrasound and Sonogenetics. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2018, 9, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdeau, R.W.; Lee-Gosselin, A.; Lakshmanan, A.; Farhadi, A.; Kumar, S.R.; Nety, S.P.; Shapiro, M.G. Acoustic reporter genes for noninvasive imaging of microorganisms in mammalian hosts. Nature 2018, 553, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, A.; Jin, Z.; Nety, S.P.; Sawyer, D.P.; Lee-Gosselin, A.; Malounda, D.; Swift, M.B.; Maresca, D.; Shapiro, M.G. Acoustic biosensors for ultrasound imaging of enzyme activity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Commercial Name | Phase | Core | Shell | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definity (Lantheus Medical Imaging) | gas | C3F8 | lipid | [12,13,16,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] |

| SonoVue/Lumason (Bracco) | gas | SF6 | lipid | [15,36,37,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| Optison (GE Healthcare) | gas | C3F8 | protein | [38,69,70,71,72,73,74] |

| SIMB (Advanced Microbubbles Inc) | gas | “gas” | lipid | [75] |

| Vevo MicroMarker (Fujifilm) | gas | C4F10 and N2 | lipid | [76] |

| BG8235 similar to BR-38 (Bracco) | gas | C4F10 | lipid | [77] |

| Targeson Inc | gas | PFC | lipid | [78] |

| USphere (Trust Bio-sonics) | gas | C3F8 | lipid | [37] |

| Sonazoid (GE Healthcare) | gas | C4F10 | lipid | [68] |

| Sonazoid (GE Healthcare) | AC: gas and liquid | Sonazoid bubbles: C4F10 Homemade droplets: C6F12 | lipid | [79] |

| Non-commercial | liquid | C3F8 or C4F10 | lipid | [33] |

| Non-commercial | liquid | C5F12 | lipid | [80] |

| Non-commercial | gas | C3F8 | protein | [81,82,83] |

| Non-commercial | gas | C3F8 | self-assembled polymeric nanoparticles | [84] |

| Non-commercial | gas | C3F8 | self-assembled polymeric nanoparticles and protein | [85] |

| Non-commercial | gas | air | polymer | [86,87] |

| Non-commercial | gas | C5F12 | polymer | [88] |

| Non-commercial | gas | SF6 | lipid | [68,89,90] |

| Non-commercial | gas | C4F10 | lipid | [6,11,14,39,68,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103] |

| Non-commercial | gas | C3F8 | lipid | [38,68,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126] |

| Ref | Bubble Type | Injection Dose (µL/kg) | Number of Bubbles per mL | Animal | Acoustic Parameters | Evans Blue Leakage | Damages Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bing et al. [38] | Optison | 30 | 7 × 108 | Sprague Dawley rats (230–300 g) | PnP = 0.47 MPa | High | NA |

| Definity | 6 | 1 × 1010 | fc = 0.75 MHz | Moderate | NA | ||

| PRF = 1 Hz | |||||||

| duration = 120 s | |||||||

| burst = 10 s | |||||||

| Shin et al. [36] | SonoVue | 30 | 2 × 108 | Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g) | PnP = 0.3 MPa | 4.45% | 1 |

| fc = 0.5 MHz | |||||||

| Definity | 20 | 1 × 1010 | PRF = 2 Hz | 13.72% | 0 | ||

| Definity | 100 | 1 × 1010 | duration = 60 s | 16.35% | 1 | ||

| burst = 10 s | |||||||

| Wu et al. [37] | SonoVue | 200 | 2 × 108 | Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g) | PnP = 0.39 MPa | 0.79 ± 0.24 µM | 0 |

| fc = 0.4 MHz | |||||||

| PRF = 1 Hz | |||||||

| Definity | 4 | 1 × 1010 | duration = 120 s | 0.52 ± 0.25 µM | 0 | ||

| burst = 10 s | |||||||

| USphere | 1.43 | 2.8 × 1010 | 0.2 ± 0.04 µM | 0 | |||

| Omata et al. [68] | Sonazoid | 3333 | 9 × 108 | ddY mice (6 week old) | Intensity = 0.5 W/cm2 | 18 ± 7 µg/g brain | 0 |

| SonoVue | 30,000 | 1 × 108 | fc = 3 MHz | 5 ± 1 µg/g brain | 0 | ||

| PRF = 10 Hz | |||||||

| duration = 180 s | |||||||

| burst = 50 s |

| Phase | Core | Shell | Storage Stability | In Vitro Acoustic Stability (Echography) | In Vivo Half-Life | Stable Cavitation Threshold | Inertial Cavitation Threshold | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| liquid | C5F12 | PEG-PLGA | stable 2 days at 4 °C | NA | NA | VT = 1.0 MPa (fc = 1 MHz) | [80] | |

| liquid | C3F8 or C4F10 | DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 9:1) | NA | NA | NA | C3F8 VT = 0.3 MPa | [33] | |

| C4F10 VT = 0.75 MPa | ||||||||

| (fc = 1.5 MHz) | ||||||||

| gas | C3F8 | DPPC: DSPE-PEG2000: DPTAP (molar ratio 9:2:1) | NA | relatively stable 50 min at 37 °C | NA | NA | 0.3 MPa (fc = 1MHz) | [105] |

| gas | C3F8 | DPTAP: DPPC: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 31,5:3,9:1,8) | NA | stable 1 h at 37 °C | 10 min (male C57BL/6J mice 20–25 g) | 0.3 MPa (fc = 1 MHz; BBB opening without damages) | 0.5 MPa | [106] |

| (fc = 1 MHz) | ||||||||

| gas | C3F8 | DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 9:1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.175 MPa | [91] |

| (fc = 0.25 MHz) | ||||||||

| 0.4 MPa | ||||||||

| (fc = 1 MHz) | ||||||||

| gas | C3F8 | DBPC: DPPA: DPPE: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 6,15:2:1:1) | NA | NA | 6–8 min (Sprague Dawley rats 230–300 g) | 0.21 MPa in vitro | 0.59 MPa in vitro | [38] |

| 0.16 MPa in vivo | 0.47 MPa in vivo | |||||||

| (fc = 0.75 MHz) | ||||||||

| gas | C3F8 | DBPC: DPPA: DPPE: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 6:1:2:1) | stable 2 h at 5 × 1010 bubbles/mL | NA | 10 min at 1011 bubbles/mL (Sprague Dawley rats 230–300 g) | 0.31 MPa in vivo | 0.70 MPa in vivo | [108] |

| (fc = 0.75 MHz; 1010 bubbles/mL) | ||||||||

| gas | C3F8 | DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 9:1) | NA | NA | 8 min (nude mice) | NA | NA | [123] |

| gas | C3F8 | DPPC: DPTAP: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 31,5:3,9:1,8) | NA | stable 1 h at 37 °C | NA | 0.3 MPa | 0.5 MPa | [107] |

| (fc = 1 MHz) | (fc = 1 MHz) | |||||||

| gas | C3F8 | DSPC: DSPG: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 21:21:1) | NA | stable 1 h at 37 °C | 7.6 min for MB 10,8 min for SPIO-DOX-MB (Sprague Dawley rats 200–250 g) | 0.3 MPa | 0.5 MPa | [109] |

| (fc = 1 MHz; BBB opening without damages) | (BBB opening with damages) | |||||||

| gas | C4F10 | DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 9:1) or DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000-Amine (molar ratio 9:1) or DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000-Amine: DSTAP (molar ratio 7:1:2) | half-life of 2 h | NA | NA | NA | NA | [39] |

| gas | C5F12 | PEGGM-PDSGM | NA | stable after 14 days at 37 °C | 10 min (mice 25–35g) | NA | NA | [88] |

| gas | C3F8 or C4F10 or SF6 | DSPC: DSPG: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 30:60:10) | NA | half-life at 37 °C | C3F8: 130 ± 50 s | NA | NA | [68] |

| C3F8: 80 ± 5 s | ||||||||

| C4F10: 190 ± 40 s | ||||||||

| C4F10: 145 ± 35 s | ||||||||

| SF6: 20 ± 20 s | ||||||||

| SF6: 20 ± 5 s | ||||||||

| gas | C4F10 | DSPC: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 9:1) | Stable 21 days | NA | NA | NA | NA | [102] |

| gas | C3F8 | DSPC: DSPG: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 10:4:1) | relatively stable 60 min at 25 °C | NA | NA | 0.3 MPa (fc = 1 MHz; BBB opening without damages) | 0.5 MPa (BBB opening with damages) | [125] |

| Bubble Characteristics | Stability Assessments * | BBB Opening Performances | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Name | Shell | Core | Average Size (µm) | In Vitro Half-Life at 37 °C ( s) | In Vivo Half-Life ( s) | Injection (µL/kg) | Evans Blue Leakage (µg/g Brain) * | 70 kDa Dextran Delivery | |

| tus = 0 s | tus = 3 min | ||||||||

| Sonazoid (GE Healthcare) | lipid | C4F10 | 2.11 ± 0.02 | 1300 ± 250 | 40 ± 20 | 3333 | 18 ± 7 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | NA |

| SonoVue (Bracco) | lipid | SF6 | 2.23 ± 0.02 | 60 ± 10 | 20 ± 10 | 30,000 | 5 ± 1 | NA | NA |

| NC | DSPC: DSPG: DSPE-PEG2000 (molar ratio 30:60:10) | C3F8 | 1.48 ± 0.02 | 80 ± 5 | 130 ± 50 | 1875 | 13 ± 3 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | high fluorescence |

| NC | C4F10 | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 145 ± 35 | 190 ± 40 | 1875 | 10 ± 1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | high fluorescence | |

| NC | SF6 | 1.63 ± 0.01 | 20 ± 5 | 20 ± 20 | 5000 | 4 ± 1 | NA | weak fluorescence | |

| Ref | Core | Shell | Molecular Targeting | Drug/Gene Embedded in the Agent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [86] | air | polymer | NA | quercetin-modified sulfur nanoparticles-loaded bubble |

| [88] | C5F12 | polymer | des-octanoyl ghrelin-conjugated bubble | TGFβ1 inhibitor (LY364947)-loaded bubble |

| [89] | SF6 | lipid | NA | GDNFp/BDNFp-loaded liposome bound to bubble |

| [90] | SF6 | lipid | NA | ultrasound-sensitizing dye-incorporating nanoparticles bound to bubble |

| [110] | C3F8 | lipid | NGR-conjugated (targeting)/shBirc5-loaded (gene) liposome bound to bubble | |

| [104] | C3F8 | lipid | anti-VEGFR2 antibody-conjugated bubble | pLUC / pHSV-TK/GCV-loaded bubble |

| [109] | C3F8 | lipid | NA | SPIO-DOX-conjugated bubble |

| [111] | C3F8 | lipid | NA | GDNFp-loaded cationic bubble |

| [112] | C3F8 | lipid | NA | pDC315/Nrf2-loaded bubble |

| [107] | C3F8 | lipid | folate-conjugated bubble | pLUC-loaded bubble |

| [105] | C3F8 | lipid | NA | pPrestin-loaded bubble |

| [106] | C3F8 | lipid | NA | boron-containing polyanion nanoparticles coupled with cationic bubble |

| [125] | C3F8 | lipid | NA | PSPIO-GDNFp-loaded bubble |

| [113] | C3F8 | lipid | phosphatidylserine nanoparticles-microbubble complex | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dauba, A.; Delalande, A.; Kamimura, H.A.S.; Conti, A.; Larrat, B.; Tsapis, N.; Novell, A. Recent Advances on Ultrasound Contrast Agents for Blood-Brain Barrier Opening with Focused Ultrasound. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111125

Dauba A, Delalande A, Kamimura HAS, Conti A, Larrat B, Tsapis N, Novell A. Recent Advances on Ultrasound Contrast Agents for Blood-Brain Barrier Opening with Focused Ultrasound. Pharmaceutics. 2020; 12(11):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111125

Chicago/Turabian StyleDauba, Ambre, Anthony Delalande, Hermes A. S. Kamimura, Allegra Conti, Benoit Larrat, Nicolas Tsapis, and Anthony Novell. 2020. "Recent Advances on Ultrasound Contrast Agents for Blood-Brain Barrier Opening with Focused Ultrasound" Pharmaceutics 12, no. 11: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111125

APA StyleDauba, A., Delalande, A., Kamimura, H. A. S., Conti, A., Larrat, B., Tsapis, N., & Novell, A. (2020). Recent Advances on Ultrasound Contrast Agents for Blood-Brain Barrier Opening with Focused Ultrasound. Pharmaceutics, 12(11), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12111125