Evaluating the Acceptability, Swallowability, and Palatability of Film-Coated Mini-Tablet Formulation in Young Children: Results from an Open-Label, Single-Dose, Cross-Over Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives

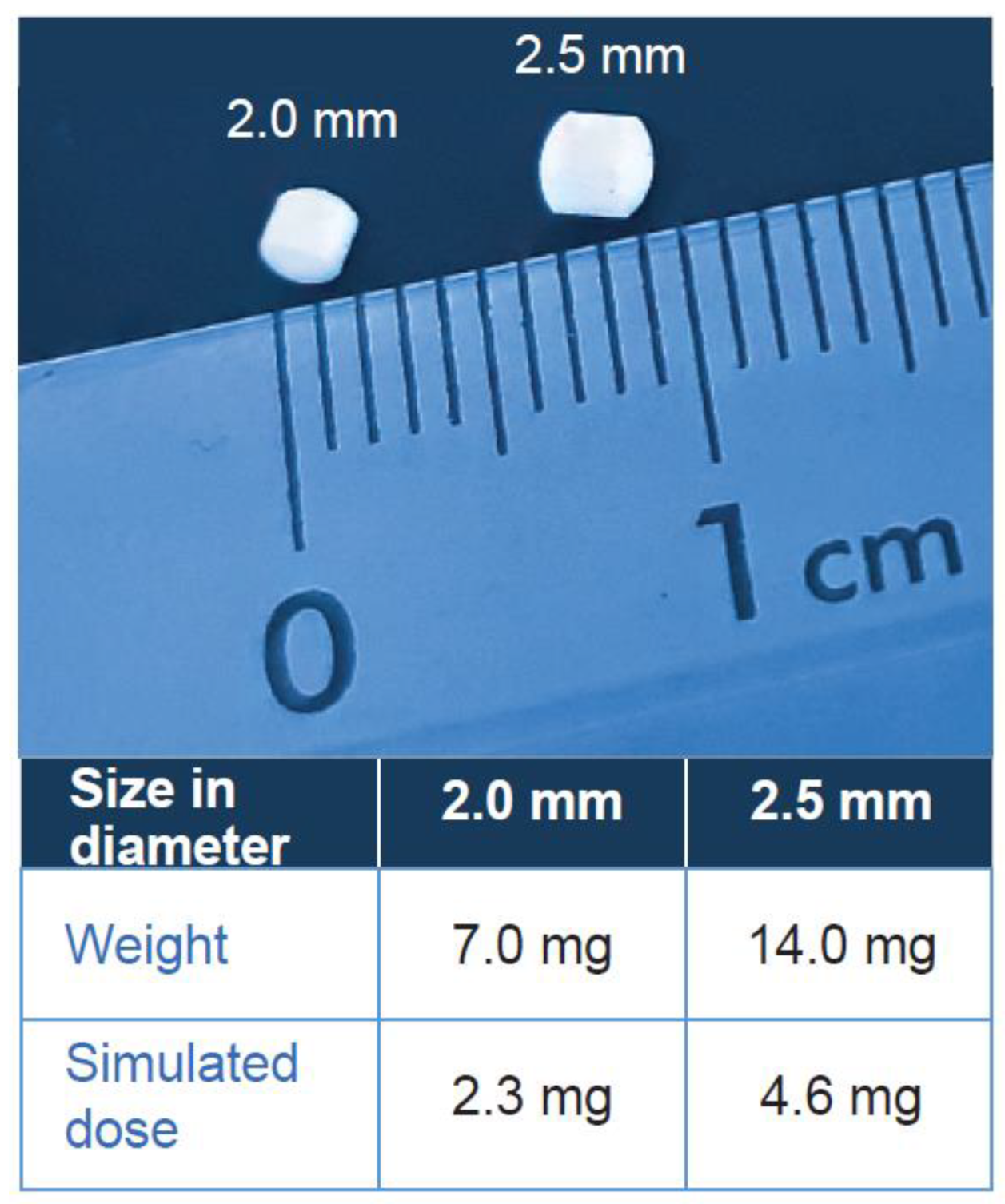

2.2. Formulations

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Study Design

2.4.1. Randomization

2.4.2. Administration Procedure

2.5. Endpoints

2.6. Evaluation Criteria

2.7. Determination of Sample Size

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Disposition of Participants

3.2. Primary Endpoint

3.2.1. Swallowability

3.3. Secondary Endpoints

3.3.1. Palatability

3.3.2. Acceptability as Composite Endpoint

3.3.3. Safety Assessments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walsh, J.; Ranmal, S.R.; Ernest, T.B.; Liu, F. Patient acceptability, safety and access: A balancing act for selecting age-appropriate oral dosage forms for paediatric and geriatric populations. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 536, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirm, E.; Tobi, H.; de Vries, T.W.; Choonara, I.; De Jong-van den Berg, L.T. Lack of appropriate formulations of medicines for children in the community. Acta Paediatr. 2003, 92, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, S.; Choonara, I.; Impicciatore, P.; Mohn, A.; Arnell, H.; Rane, A.; Knoeppel, C.; Seyberth, H.; Pandolfini, C.; Raffaelli, M.P.; et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. European Network for Drug Investigation in Children. BMJ 2000, 320, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sutcliffe, A.G. Prescribing medicines for children. BMJ 1999, 319, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavasili, C.; Gkaragkounis, A.; Fatouros, D.G. Patent landscape of pediatric-friendly oral dosage forms and administration devices. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.S.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Wolf, M.S.; Parker, R.M.; Fierman, A.; van Schaick, L.; Bazan, I.S.; Kline, M.D.; Dreyer, B.P. Parents’ medication administration errors: Role of dosing instruments and health literacy. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 164, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- EMA. Guideline on Pharmaceutical Development of Medicines for Paediatric Use. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-pharmaceutical-development-medicines-paediatric-use_en.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Thomson, S.A.; Tuleu, C.; Wong, I.C.; Keady, S.; Pitt, K.G.; Sutcliffe, A.G. Minitablets: New modality to deliver medicines to preschool-aged children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e235–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spomer, N.; Klingmann, V.; Stoltenberg, I.; Lerch, C.; Meissner, T.; Breitkreutz, J. Acceptance of uncoated mini-tablets in young children: Results from a prospective exploratory cross-over study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingmann, V.; Spomer, N.; Lerch, C.; Stoltenberg, I.; Fromke, C.; Bosse, H.M.; Breitkreutz, J.; Meissner, T. Favorable acceptance of mini-tablets compared with syrup: A randomized controlled trial in infants and preschool children. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1728–1732.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingmann, V.; Seitz, A.; Meissner, T.; Breitkreutz, J.; Moeltner, A.; Bosse, H.M. Acceptability of Uncoated Mini-Tablets in Neonates--A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 893–896.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingmann, V.; Linderskamp, H.; Meissner, T.; Mayatepek, E.; Moeltner, A.; Breitkreutz, J.; Bosse, H.M. Acceptability of Multiple Uncoated Minitablets in Infants and Toddlers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. 2018, 201, 202–207.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münch, J.; Meissner, T.; Mayatepek, E.; Wargenau, M.; Breitkreutz, J.; Bosse, H.M.; Klingmann, V. Acceptability of small-sized oblong tablets in comparison to syrup and mini-tablets in infants and toddlers: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 166, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliga, S.; Muglikar, S.; Kale, R. Salivary pH: A diagnostic biomarker. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUDRAGIT. Pharma Excipients. Available online: https://www.pharmaexcipients.com/product/eudragit-e-po/ (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- WHO. Child Growth Standards. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards/weight-for-age (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Schouten, H.; Kester, A. A simple analysis of a simple crossover trial with a dichotomous outcome measure. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMA. Reflection Paper: Formulations of Choice for the Paediatric Population. p. 22. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-formulations-choice-paediatric-population_en.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Arvedson, J.C.; Brodsky, L. Pediatric Swallowing and Feeding: Assessment and Management; Plural Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Jacobsen, L.; Jhaveri, R.; Bradford, K.K. Effectiveness of Pediatric Pill Swallowing Interventions: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beauchamp, G.K.; Mennella, J.A. Flavor perception in human infants: Development and functional significance. Digestion 2011, 83 (Suppl. S1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schubart, A.; Anderson, K.; Mainolfi, N.; Sellner, H.; Ehara, T.; Adams, C.M.; Mac Sweeney, A.; Liao, S.M.; Crowley, M.; Littlewood-Evans, A.; et al. Small-molecule factor B inhibitor for the treatment of complement-mediated diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7926–7931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bomback, A.S.; Kavanagh, D.; Vivarelli, M.; Meier, M.; Wang, Y.; Webb, N.J.A.; Trapani, A.J.; Smith, R.J.H. Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibition with Iptacopan for the Treatment of C3 Glomerulopathy-Study Design of the APPEAR-C3G Trial. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 7, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peffault de Latour, R.; Roeth, A.; Kulasekararaj, A.; Scheinberg, P.; Ueda, Y.; de Castro, C.M.; Di Bona, E.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Langemeijer, S.M.; Barcellini, W.; et al. Oral Monotherapy with Iptacopan, a Proximal Complement Inhibitor of Factor B, Has Superior Efficacy to Intravenous Terminal Complement Inhibition with Standard of Care Eculizumab or Ravulizumab and Favorable Safety in Patients with Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria and Residual Anemia: Results from the Randomized, Active-Comparator-Controlled, Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase III Apply-PNH Study. Blood 2022, 140, LBA-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=iptacopan&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 17 April 2023).

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Children aged ≥ 1 month to ≤6 years | Impairment of swallowing solids due to illness |

| Male and female | Lactose-intolerance |

| Ability to swallow | Premedication and concomitant medication that cause nausea, fatigue, or palsy |

| Willingness and capability of participants and participants’ parents or legal guardians to comply with examination procedures | Children in the post-operative period who were yet to commence regular oral feeding |

| Participant and/or participant’s parents or legal gaurdian capabable of providing written informed consent and assent where possible | Children, who had eaten one hour before examination and who afterwards feel sick because of the food |

| A. Scoring Criteria for Swallowability | |||

| Score | Observation | ||

| 1 | Swallowed | No chewing took place during deglutition and no residuals of the solid were found during oral inspection. | |

| 2 | Chewed/left over | Chewing was observed before deglutition and/or that the whole or parts of the solid were found in the mouth during oral inspection and/or some mini-tablets left over on the spoon (≥80% should have been swallowed). | |

| 3 | Spat out | No deglutition took place and the solid was no longer in the child’s mouth. | |

| 4 | Choked on | The solid was swallowed the wrong way or a cough was caused. | |

| 5 | Refused to take | The child did not allow the investigator to place the solid in the mouth and/or <80% of mini-tablets swallowed. | |

| B. Definition of acceptability derived from swallowability alone | |||

| Criteria | |||

| Acceptable | Yes | Swallowability score was 1 or 2 | |

| No | Swallowability score was >2 (3–5) | ||

| C. Scoring criteria for palatability | |||

| Score | Assessment | Interpretation | |

| 1 | Pleasant | Positive hedonic pattern: Tongue protrusion, smack of mouth and lips, finger sucking, corner elevation | |

| 2 | Neutral | Neutral mouth and body movements, and face expressions (irregular and involving lips) | |

| 3 | Unpleasant | Negative aversive pattern: Gape, nose wrinkle, eye squinch, frown, grimace, head shake, arm flail | |

| D. Scoring criteria for composite acceptability endpoint derived from palatability and swallowability | |||

| Palatability | Swallowability score | ||

| 1 | 2 | ≥3 | |

| Pleasant | High | Good | No |

| Neutral | Good | Low | No |

| Unpleasant | Low | No | No |

| E. Acceptability as composite acceptability endpoint | |||

| Yes: High/good | |||

| No: low/no | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Münch, J.; Sessler, I.; Bosse, H.M.; Wargenau, M.; Dreesen, J.D.; Loforese, G.; Webb, N.J.A.; Sivasubramanian, R.; Reidemeister, S.; Lustenberger, P.; et al. Evaluating the Acceptability, Swallowability, and Palatability of Film-Coated Mini-Tablet Formulation in Young Children: Results from an Open-Label, Single-Dose, Cross-Over Study. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15061729

Münch J, Sessler I, Bosse HM, Wargenau M, Dreesen JD, Loforese G, Webb NJA, Sivasubramanian R, Reidemeister S, Lustenberger P, et al. Evaluating the Acceptability, Swallowability, and Palatability of Film-Coated Mini-Tablet Formulation in Young Children: Results from an Open-Label, Single-Dose, Cross-Over Study. Pharmaceutics. 2023; 15(6):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15061729

Chicago/Turabian StyleMünch, Juliane, Isabelle Sessler, Hans Martin Bosse, Manfred Wargenau, Janine D. Dreesen, Giulio Loforese, Nicholas J. A. Webb, Rama Sivasubramanian, Sibylle Reidemeister, Philipp Lustenberger, and et al. 2023. "Evaluating the Acceptability, Swallowability, and Palatability of Film-Coated Mini-Tablet Formulation in Young Children: Results from an Open-Label, Single-Dose, Cross-Over Study" Pharmaceutics 15, no. 6: 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15061729

APA StyleMünch, J., Sessler, I., Bosse, H. M., Wargenau, M., Dreesen, J. D., Loforese, G., Webb, N. J. A., Sivasubramanian, R., Reidemeister, S., Lustenberger, P., & Klingmann, V. (2023). Evaluating the Acceptability, Swallowability, and Palatability of Film-Coated Mini-Tablet Formulation in Young Children: Results from an Open-Label, Single-Dose, Cross-Over Study. Pharmaceutics, 15(6), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15061729