The Influence of Tourists’ Experience on Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Hue City, Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (a).

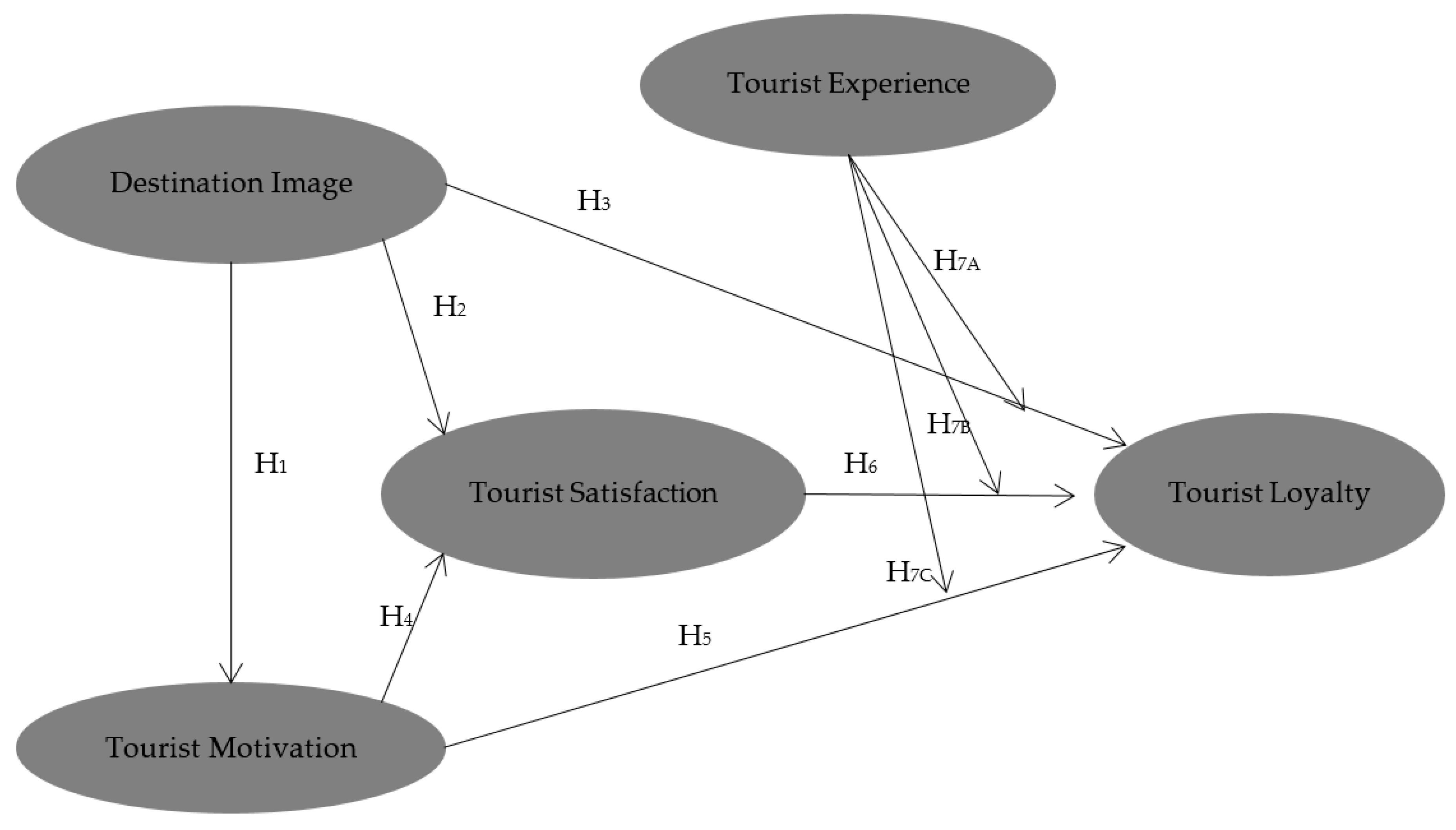

- This study measures the impact of tourist motivation, tourist satisfaction, and destination image on tourist loyalty.

- (b).

- To examine the moderating role of tourist experience on destination image, tourist motivation, tourist satisfaction, and tourist loyalty.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Destination Image

2.2. Tourist Motivation

2.3. Tourist Satisfaction

2.4. Tourist Experience

2.5. Tourist Loyalty

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Measurement Model Assessment

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Results

4.2. Discussion

5. Contributions and Limitations

5.1. Contributions

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, Quality, and Loyalty: Local Food and Sustainable Tourism Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, S.; Gibson, H.; Sisson, L. The loyalty process of residents and tourists in the festival context. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechinda, P.; Serirat, S.; Gulid, N. An examination of tourists’ attitudinal and behavioral loyalty: Comparison between domestic and international tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gursoy, D. An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Otoo, F.E.; Suntikul, W.; Huang, W.-J. Understanding culinary tourist motivation, experience, satisfaction, and loyalty using a structural approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N.; Triyuni, N.N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Abdullah, S.K.; Lew, T.Y.; Islam, M.F. Determining factors of tourists’ loyalty to beach tourism destinations: A structural model. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Zeng, S.; Cheng, P.S.-T. The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: A case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of Tourists’ Loyalty to Mauritius. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chen, J.; Chi, C.G. Theoretical examination of destination loyalty formation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Naranjo, M.T.; Gálvez, J.C.P.; Carvache-Franco, W. Segmentation and motivation of foreign tourists in world heritage sites. A case study, Quito (Ecuador). Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1170–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Fernández, G.A.; López-Guzmán, T.; Molina, D.L.; Gálvez, J.C.P. Heritage tourism in the Andes: The case of Cuenca, Ecuador. Anatolia 2017, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Complex of Hué Monuments—UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/678/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- González Santa Cruz, F.; Lopez-Guzman, T.; Pemberthy Gallo, L.S.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, P. Tourist Loyalty and Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Case of Popayán, Colombia. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 10, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Viruel, M.J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Gálvez, J.C.P.; Jara-Alba, C. Emotional perception and tourist satisfaction in world heritage cities: The Renaissance monumental site of úbeda and baeza, Spain. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 27, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Fuentes-Medina, M.L.; Morini-Marrero, S. Memorable tourist experiences versus ordinary tourist experiences analysed through user-generated content. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Malek, K. Effects of self-congruity and destination image on destination loyalty: The role of cultural differences. Anatolia 2017, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.A. Altruism in the household: In kind transfers in the context of kin selection. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2013, 11, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Edwards, D.; Mistilis, N.; Roman, C.; Scott, N. Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeugner-Roth, K.P.; Žabkar, V. Bridging the gap between country and destination image: Assessing common facets and their predictive validity. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G. Patterns of tourists’ emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengesayi, S.; Mavondo, F.T.; Reisinger, Y. Tourism Destination Attractiveness: Attractions, Facilities, and People as Predictors. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Measuring Destination Attractiveness: A Contextual Approach. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Morais, D.B. Antecedents of Attachment to a Cultural Tourism Destination: The Case of Hakka and Non-Hakka Taiwanese Visitors to Pei-Pu, Taiwan. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.B.; Qu, H. The Impact of Destination Images on Tourists’ Perceived Value, Expectations, and Loyalty. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 9, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Juwaheer, T.D.; Hu, H.-H. The Influence of a Hotel Firm’s Quality of Service and Image and its Effect on Tourism Customer Loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, O.H. Understanding and measuring tourist destination images. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M. Destination image representation on the web: Content analysis of Macau travel related websites. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.C. The social construction of tourism online destination image: A comparative semiotic analysis of the visual representation of Seoul. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Haron, M.S. Medical tourism destination image formation process: A conceptual model. Int. J. Health Manag. 2016, 9, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K. The role of destination image in tourism: A review and discussion. Tour. Rev. 1990, 45, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M.; Kumar, K. Promoting Tourism Destination Image. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.-S. Tourism destination image modification process. Tour. Manag. 1991, 12, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, H.C. Examining the festival attributes that impact visitor experience, satisfaction and re-visit intention. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. A Structural Model to Examine How Destination Image, Attitude, and Motivation Affect the Future Behavior of Tourists. Leis. Sci. 2009, 31, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.; Skallerud, K.; Chen, J. Tourist Motivation with Sun and Sand Destinations: Satisfaction and the Wom-Effect. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraftchick, J.F.; Byrd, E.T.; Canziani, B.; Gladwell, N.J. Understanding beer tourist motivation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 12, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A. Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, S. Understanding the cultural differences in tourist motivation between anglo-american and japanese tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 9, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourist Motivation and Quality-of-Life: In Search of the Missing Link. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki, A. An exploration of tourist motivation in rural settings: The case of Troodos, Cyprus. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2–3, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.-K.; Yoon, D.; Park, E. Tourist motivation: An integral approach to destination choices. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.-S. Understanding recreational traveler’s motivation, attitude and satisfaction. Tour. Rev. 1989, 44, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.A. Tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1980, 7, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, J. Tourism models: The sociocultural aspects. Tour. Manag. 1987, 8, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Examining the relationship between tourist motivation and satisfaction by two competing methods. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Impact of Tourist Perceptions, Destination Image and Tourist Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Conceptual Model. PASOS. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2013, 11, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, J.L.; Cote, J.A. Defining Consumer Satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2002, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, J.; Uysal, M.; McCleary, K. Cultural/Heritage Destinations: Tourist Satisfaction and Market Segmentation. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2006, 14, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Weiermair, K. New perspectives of satisfaction research in tourism destinations. Tour. Rev. 2003, 58, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kwifi, O.S. The impact of destination images on tourists’ decision making: A technological exploratory study using fMRI. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2015, 6, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.; Smith, M.; Duffy, R. Contemporary Geographies of Leisure, Tourism and Mobility the Moralisation of Tourism Sun, Sand … and Saving the World? Available online: http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/18575/1/78.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Cronin, J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The Impact of Memorable Tourism Experiences on Loyalty Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Destination Image and Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Chang, P.-S. Examining the Relationships among Festivalscape, Experiences, and Identity: Evidence from Two Taiwanese Aboriginal Festivals. Leis. Stud. 2016, 36, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The Relationships of On-Site Film-Tourism Experiences, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions: The Case of Asian Audience’s Responses to a Korean Historical TV Drama. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, H.; Draper, J.; Taylor, W. The Quality of Teachers’ Professional Lives: Teachers and Job Satisfaction. Eval. Res. Educ. 1998, 12, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.K.; Wan, D.; Ho, A. Tourists’ satisfaction, recommendation and revisiting Singapore. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Skarmeas, D.; Oghazi, P.; Beheshti, H.M. Achieving tourist loyalty through destination personality, satis-faction, and identification. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2227–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M.; Lu, D.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Word of Mouth on Tourism Destination Choice: Tourist–Resident Relationship and Safety Perception among Mainland Chinese Tourists Visiting Macau. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodds, R.; Jolliffe, L. Experiential Tourism: Creating and Marketing Tourism Attraction Experiences. In The Handbook of Managing and Marketing Tourism Experiences; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2016; pp. 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Wibisono, N.; Astor, Y.; Muflih, M.; Kartikasari, A.; Sutrisno, R.; Hardiyanto, N. Tourist experience in Halal tourism: What leads to loyalty? Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1976–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, J.S.; Kieti, D.M. Measuring tourist satisfaction with Kenya’s wildlife safari: A case study of Tsavo West National Park. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selemani, I.S. Indigenous knowledge and rangelands’ biodiversity conservation in Tanzania: Success and failure. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 3863–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Y.; Li, M. Visitors’ satisfaction at managed tourist attractions in Northern Norway: Do on-site factors matter? Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjakajornsak, V. Analyzing the Effects of Past Visits, Image, and Satisfaction on the Loyalty of Foreign Tourists: A Model of Destination Loyalty. NIDA Dev. J. 2011, 51, 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauer, B.; Ryan, C. Destination image, romance and place experience—An application of intimacy theory in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, T. Tourist Experiences and Academic Junctures. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Geographical consciousness and tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 863–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selstad, L. The Social Anthropology of the Tourist Experience. Exploring the ‘Middle Role. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, G.; Lee, Y.-S.; Ayling, A.; Lunny, B.; Cater, C.; Ollenburg, C. Quality Tourism Experiences: Reviews, Reflections, Research Agendas. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Q.; Huang, S.; Yang, R. Restoration in the exhausted body? Tourists on the rugged path of pilgrimage: Motives, experiences, and benefits. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundner, L.; Neuhofer, B. The bright and dark sides of artificial intelligence: A futures perspective on tourist destination experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi, Y.; Abror, A.; Trinanda, O. Halal tourism: Antecedent of tourist’s satisfaction and word of mouth (WOM). Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Refaie, A.; Ko, J.H.; Li, M.H. Examining the factors that affect tourists’ satisfaction, loyalty, WOM and intention to return using SEM: Evidence from Jordan. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2012, 3, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, P.Y. The Effect of e-WOM on Destination Image, Satisfaction and Loyalty. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2014, 3, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; González, F.J.M. The Importance of Quality, Satisfaction, Trust, and Image in Relation to Rural Tourist Loyalty. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A.; Kulczycki, C.; Moghimehfar, F. Factors effecting destination and event loyalty: Examining the sustainability of a recurrent small-scale running event at Banff National Park. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awatara, I.G.P.D.S.; Samsi, A.; Hamdani, L.; Susila, N. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility, Reputation and Customer Satisfaction Toward Tourism Loyalty on Karanganyar Regency. J. Int. Conf. Proc. 2020, 3, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Cossío-Silva, F.-J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.-A.; Vega-Vázquez, M. The tourist loyalty index: A new indicator for measuring tourist destination loyalty? J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Examining the role of destination personality and self-congruity in predicting tourist behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.M.; Sakulsinlapakorn, K. Exploring Tourists’ Push and Pull Travel Motivations to Participate in Songkran Festival in Thailand as a Tourist Destination: A Case of Taiwanese Visitors. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 4, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandralal, L.; Valenzuela, F.-R. Memorable Tourism Experiences: Scale Development. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2015, 11, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. Assessing Tourist Experience Satisfaction with a Heritage Destination. Open Access Theses. 2019. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/107 (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Mohamad, M.; Abdullah, A.R.; Mokhlis, S. Tourists’ Evaluations of Destination Image and Future Behavioural Intention: The Case of Malaysia. J. Manag. Sustain. 2012, 2, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in in-formation systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, L. Thompson Does PLS Have Advantages for Small Sample Size or Non-Normal Data? MIS Q. 2012, 36, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models: Regression, Analysis of Variance, and Experimental Designs; Irwin: Chicago, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Factors influencing destination image and visit intention among young women travellers: Role of travel motivation, perceived risks, and travel constraints. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, L.A.; Lehto, X.Y.; Huang, J. A Missing Link in Understanding Revisit Intention—The Role of Motivation and Image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Tung, V.W.S. The impact of tourism mini-movies on destination image: The influence of travel motivation and advertising disclosure. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artuğer, S.; Cevdet Çetinsöz, B.; Kılıç, İ. The Effect of Destination Image on Destination Loyalty: An Application in Alanya. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, M.; Han, H.-S.; Holland, S. The determinants of hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: The moderating role of generational differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From tourist motivations to tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Chikuta, O.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Travel motivation and tourist satisfaction with wildlife tourism experiences in Gonarezhou and Matusadona National Parks, Zimbabwe. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A.E.; Keskin, H.; Ayar, H.; Erdoğan, E. The Influence of Storytelling Approach in Travel Writings on Readers’ Empathy and Travel Intentions. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna-García, M. Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S. Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Valle, M.; Silva, P.O.; Mendes, J.A.; Guerreiro, J.; Do, V.; Patrícia, O.; Silva, J.A.; Mendes, J.; Guerreiro, M. Tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty intention: A structural and categorical analysis. Int. J. Bus. Sci. Appl. Manag. 2006, 1, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. Analysis of Structural Equation Model for the Student Pleasure Travel Market: Motivation, Involvement, Satisfaction, and Destination Loyalty. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiby, M.A.; Slåtten, T. The role of aesthetic experiential qualities for tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Noor, S.M.; Schuberth, F.; Jaafar, M. Investigating the effects of tourist engagement on satisfaction and loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 39, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Del Barrio-García, S.; López-Moreno, L. Determinants of Satisfaction with Holidays and Hospitality in Rural Tourism in Spain. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2012, 54, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Ángel, R.; Frías-Jamilena, D.-M.; Garcia, J.A.C. The moderating role of past experience in the formation of a tourist destination’s image and in tourists’ behavioural intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Estimating moderating effects in pls-sem and plsc-sem: Interaction term generation*data treatment. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2018, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 98 | 48% |

| Female | 106 | 52% |

| Age (Year) | ||

| 18–29 | 15 | 7% |

| 30–39 | 24 | 12% |

| 40–49 | 34 | 17% |

| 50–59 | 41 | 20% |

| 60 and above | 90 | 44% |

| Education | ||

| Under high school | 21 | 10% |

| High school | 42 | 21% |

| College | 63 | 31% |

| Graduate or postgraduate | 78 | 38% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 79 | 39% |

| Married | 95 | 47% |

| Separated | 14 | 7% |

| Widower | 9 | 4% |

| Decline to answer | 7 | 3% |

| Monthly Income (USD) | ||

| Under 5000 | 18 | 9% |

| 5000–10,000 | 23 | 11% |

| 10,000–20,000 | 31 | 15% |

| 20,000–30,000 | 33 | 16% |

| 30,000–40,000 | 23 | 11% |

| 40,000–50,000 | 17 | 9% |

| Over 50,000 | 12 | 6% |

| Decline to answer | 47 | 23% |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 48 | 24% |

| Employed/self-employed | 18 | 9% |

| Retired | 15 | 7% |

| Other | 123 | 60% |

| Code | Construct | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Destination Image | ||

| DI 1 | My visit to this destination is worth my time and effort | [95] |

| DI 2 | Compared to other destinations, this destination is a much better one | |

| DI 3 | My experiences with this destination are excellent | |

| DI 4 | Overall, I am satisfied with the travel experience in this destination | |

| Tourist Motivation | ||

| TM 1 | To relax in foreign land | [96] |

| TM 2 | To get experience in foreign land | |

| TM 3 | To learn new culture | |

| TM 4 | To see how the people of difference cultures live | |

| Tourist Experience | ||

| TE 1 | This trip helped me to improve my self-confidence | [97] |

| TE 2 | This trip helped me to develop my personal identify | |

| TE 3 | This trip helped me to learn more about myself | |

| TE 4 | This trip helped me to acquire new skills | |

| Tourist Satisfaction | ||

| TSA1 | Hue is one of the best destinations for cultural heritage tourism | [98] |

| TSA2 | My choice to visit Hue was a wise one | |

| TSA3 | I think I made the right decision to visit the destination | |

| TSA4 | I am satisfied with my overall experience during my visit | |

| Tourist Loyalty | ||

| LOY 1 | Will say positive things about Hue to other people | [99] |

| LOY 2 | Suggest Hue to friend and relatives as a vacation destination to visit | |

| LOY 3 | Consider Hue as your choice to visit in the future | |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach Alpha | AVE | CR | rho_A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE | TE1 | 0.997 | 0.995 | 0.990 | 1 | 0.998 |

| TE2 | 0.998 | |||||

| TE3 | 0.991 | |||||

| DI | DI1 | 0.882 | 0.842 | 0.680 | 0.890 | 0.853 |

| DI2 | 0.789 | |||||

| DI3 | 0.842 | |||||

| DI4 | 0.774 | |||||

| TM | TM1 | 0.940 | 0.946 | 0.860 | 0.960 | 0.954 |

| TM2 | 0.940 | |||||

| TM3 | 0.919 | |||||

| TM4 | 0.913 | |||||

| TSA | TSA1 | 0.880 | 0.861 | 0.710 | 0.910 | 0.862 |

| TSA2 | 0.893 | |||||

| TSA3 | 0.841 | |||||

| TSA4 | 0.744 | |||||

| LOY | LOY1 | 0.788 | 0.702 | 0.620 | 0.830 | 0.707 |

| LOY2 | 0.798 | |||||

| LOY3 | 0.784 |

| TE | DI | LOY | TSA | TM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE | 0.995 | ||||

| DI | 0.032 | 0.823 | |||

| LOY | 0.341 | 0.259 | 0.790 | ||

| TSA | 0.395 | 0.064 | 0.474 | 0.840 | |

| TM | 0.332 | 0.194 | 0.274 | 0.360 | 0.930 |

| Effects | β | Mean Value | Std. Dev | t-Value | p-Value | Hypothesis Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| DI -> LOY | 2.813 | 0.214 | 0.074 | 2.798 | 0.005 | Yes |

| DI -> TSA | 0.072 | −0.006 | 0.086 | 0.072 | 0.943 | No |

| DI -> TM | 3.058 | 0.204 | 0.068 | 2.855 | 0.004 | Yes |

| TSA -> LOY | 3.817 | 0.34 | 0.091 | 3.849 | 0.000 | Yes |

| TM -> LOY | 0.807 | 0.064 | 0.081 | 0.736 | 0.462 | No |

| TM -> TSA | 5.065 | 0.362 | 0.072 | 5.047 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Indirect Effect (Moderation) | ||||||

| TE -> DI -> LOY | 2.027 | −0.142 | 0.075 | 1.883 | 0.060 | No |

| TE -> TSA -> LOY | 1.669 | 0.131 | 0.08 | 1.707 | 0.088 | No |

| TE -> TM -> LOY | 1.769 | 0.148 | 0.065 | 2.134 | 0.033 | Yes |

| Dependent Variable | Coefficient of determination (R2) | Empirical Remark | ||||

| Tourist Loyalty | 0.527 | Robust | ||||

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Std. Dev. | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOY | 0.361 | 0.394 | 0.053 | 6.789 | 0.000 |

| TSA | 0.130 | 0.142 | 0.047 | 2.769 | 0.006 |

| TM | 0.037 | 0.046 | 0.027 | 1.376 | 0.169 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hung, V.V.; Dey, S.K.; Vaculcikova, Z.; Anh, L.T.H. The Influence of Tourists’ Experience on Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Hue City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168889

Hung VV, Dey SK, Vaculcikova Z, Anh LTH. The Influence of Tourists’ Experience on Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Hue City, Vietnam. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168889

Chicago/Turabian StyleHung, Vo Viet, Sandeep Kumar Dey, Zuzana Vaculcikova, and Le Trieu Hoang Anh. 2021. "The Influence of Tourists’ Experience on Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Hue City, Vietnam" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8889. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168889