Abstract

The formal input supply sector has received little attention in developing nations, including Haiti. We interviewed input store owners in Haiti and collected information on the availability and sources of inputs and challenges facing vendors. Three large suppliers import most inputs available to farmers. Second tier traders, mostly small stores that purchase from the major suppliers, play a critical role in making inputs accessible to rural communities. These formal stores have significant potential to transform the agricultural sector but face three major challenges. (1) Improved seed is a critically needed input, but older cultivars dominate because there is limited breeding in Haiti, few seed importers, and inadequate patent protections that make holders reluctant to move new varieties into Haiti. (2) The types of fertilizers and pesticides available to farmers are limited and many are technologically outdated. (3) In-country transportation is slow and relatively expensive and needed inputs often do not reach farmers in a timely manner. We conclude that approaches that bring together the strengths and assets of the public sector, the non-profit private sector and the for-profit private sector and increased attention to policy measures that benefit all three sectors are requisites for supply chain development in Haiti.

1. Introduction

The term “technological orphanage” describes the current status of agricultural innovation in many developing nations [1]. Agricultural research in post-industrial nations is increasingly privatized and available only to users who can afford the products research creates. Public investment in agricultural research for development (AR4D) in developing nations is limited, decreasing in many cases, and has not generated the innovations needed to support large scale, sustained increases in productivity in many nations. Despite over 50 years of international efforts to improve food production in developing nations, relatively little progress has been made in many countries. The plight of Haiti provides an example of the high cost of technological orphanages. The World Food Programme (WFP) reports that more than half of the total population of Haiti is food insecure and 22% of children are chronically malnourished. Over 50% of the nation’s food requirements comes from imports [2].

Improving agricultural technology has been a primary focus of national and international strategies to improve food production in developing nations, but the outcomes of this effort in terms of increased productivity, poverty reduction, and economic growth are inconsistent. Aniembabazi et al. cite numerous studies showing the beneficial outcomes of individual innovations on food and nutrition security and poverty reduction [3]. “Improved varieties” are an example. These varieties are improved compared to materials produced with no intent to be used as seed, but the term improved varieties in the context of most developing nations, including Haiti, does not refer to the most recent generations of varieties produced through contemporary breeding programs. It differentiates long-established open-pollinated and hybrids from seed of unknown lineage and from the most recent varieties, which are rarely available in developing nations and are very expensive, typically beyond what farmers in these nations can pay. Aniembabazi et al.’s analysis of the overall effect of AR4D on household poverty in in Ethiopia [4], Zambia [5], Mexico [6], Malawi [7], and Tanzania [8] show complex outcomes [3]. They found that the benefits of AR4D accrue differentially to households based on household traits, individual technologies, and packages or ensembles of technologies. Similarly, DeJanvry and Sadoulet [9] (pp. 11–12) found that investments in improving technology use in agriculture is a fruitful strategy in places where most of the poor are rural people and agriculture accounts for a large portion of GDP. Examples of these agriculture-based countries, according to DeJanvry and Sadouet, include poor countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and Central America.

The traditional approaches to agricultural research and dissemination of technologies over the past 50 years have not transformed agricultural productivity in developing nations. As a result, some approaches called for more appropriate technologies that developing nations can generate internally, alternative innovations that do not depend on widescale adoption of technologies developed in post-industrial nations. Appropriate or intermediate technology, as defined by E. F. Schumacher [10], refers to technological choices and applications that make use of locally available resources and are suitable for use in developing countries. These approaches emphasize self-sufficiency, which theoretically divorces input sourcing from the international input supply system. Low external-input sustainable agriculture (LEISA) focuses largely on the world’s poorer farmers, those with limited capacity to purchase agricultural inputs. Moser and Bennett provide an example of LEISA in Madagascar, a rice system requiring no chemical pesticides or fertilizers and using local rice varieties [11]. The system reduced input costs, but the high labor demand in the LEISA system appears to have contributed to a high rate of dis-adoption. Both the appropriate technology and LEISA approaches demonstrate the constraints to input substitution as a solution to increasing agricultural productivity.

Limited access to agricultural inputs remains a critical barrier to increasing agricultural production in developing nations [12] (pp. 278–279). In the 1960s and 1970s, national governments and donors tried to duplicate Asia’s Green Revolution by subsidizing inputs, expanding government services, and creating parastatal organizations to provide inputs and market farm products. By the mid-1980s, it was apparent that the subsidies and parastatals were not economically sustainable, and structural adjustment approaches became common. These approaches drastically reduced the role of public agencies and curtailed subsidies, based on the assumption that the private sector would step in to fill the gap. By the mid-1990s, it was clear that the anticipated private sector activity had not materialized at the national level in most poorer nations and the potential markets were not large enough or stable enough to attract international private sector players. Ultimately, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and government agencies took on the task of input supply, especially to poorer farmers, farmers in more remote areas, and farmers raising food crops primarily for domestic supply. By the turn of the century, it was clear that this strategy also showed limited success due to the high cost of operation, lack of coordination and continuity at the local or national level, and poor capacity for scaling up to reach the entire target population.

Reardon et al.’s recent analysis of the role of agricultural research takes a whole system approach to understanding the factors that affect innovation and transformation of food and agricultural systems in developing nations [13]. The authors treat the food system as a dendritic system consisting of a number of chains or flows and identifies six chains: (1) output value chains, (2) farm input supply chains, (3) “feeder” supply chains that serve the post-farmgate chains (like fuel to transport crops to market), (4) financial supply chains, (5) public assets like roads, and (6) agricultural research and development chains that supply technology [13] (p. 48). Social changes, such as increased meat in the diet or urbanization, affect all of these chains through complex interactions. This whole-system analysis concludes with a discussion of critical implications for the agricultural research community [13] (pp. 56–57). They argue that the research community needs to expand research effort in areas other than farm production, pointing to the importance of developing technologies in all aspects of the food system that will lead to profitable marketed output for farmers. This includes both “upstream” chains like the input supply chains and the post-farmgate chains that process, transport, and market agricultural products. They emphasize the need for much greater attention to the input supply chain in developing nations because the input supply chain is the pathway to implementation of innovations generated by AR4D and the adoption of new technologies. Reardon et al. also argue that the private sector is now dominant in the dissemination of innovations and conclude that partnerships between the private sector and the research community is critical to transforming agriculture in developing nations [13].

Much like other countries, farmers in Haiti use various formal and informal channels to acquire seeds and other agricultural inputs. The formal sector in the agricultural input system markets inputs through private, for-profit businesses and governmental and non-governmental agencies [14]. The informal channels include direct gifts from family or friends, local marketers and traders, and farmers’ own stock from previous seasons. Research has shown that, similar to other developing countries, Haitian farmers tend to rely on informal channels to purchase agricultural inputs. For instance, the most recent (2010) assessment of the seed system in Haiti reveals that more than 90% of seeds sown are acquired through informal means [14]. The common use of informal means to acquire inputs has led researchers to focus their attention on the informal channels to gain a better understanding of agricultural input systems. As a result, little is known about the nature and functioning of the formal sector agricultural input systems or the factors that explain the constraints to growth and development of formal sector systems in developing countries.

Even though the formal sector is not a primary source of agricultural inputs for most farmers, a well-functioning formal sector is critical to boosting the impact of agricultural input systems. Understanding and scaling the formal input sector is especially critical to improving access to quality inputs. Planting materials are an example of a critical input that formal input systems can more effectively fulfill than informal channels. The formal sector makes a clear difference between seed and grain, a distinction that is not always clear in informal markets. Farmers who purchase planting material in the informal sector may get material that was not treated and stored under the conditions necessary for good germination or protection from diseases. Moreover, the formal sector has a greater capability to inform farmers about new varieties and provides greater access to varieties as they are released by plant breeders—important factors for increasing productivity.

The Feed the Future Haiti Appui à la Recherche et au Développement Agricole (AREA) project was a five-year effort funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) launched in May 2015 to enhance and expand Haiti’s efforts to address food insecurity and undernutrition by strengthening and supporting the country’s public and private agricultural institutions. The goal of the project was to build the capacity of Haitian institutions to increase the availability of improved production technologies to farmers and the private sector through effective development of an agricultural innovation system. This study of the formal input supply system provided critical information prior to initiating a major research component of the AREA project in which a quasi-experiment was used to test the efficacy of three approaches to dissemination of information about new technologies. The objective of the experimental study was to determine which approach would lead to the greatest number of farmer participants in the study testing one of seven innovations on their own land and at their own cost. A basic understanding of the local input supply chain was needed because the chain was the critical link between new knowledge (the treatments) and the outcome measure of farmer willingness to assume the cost of testing a product on his/her own farm. The outcome measure was the percentage of farmers in each of 30 participating farmer associations who acquired and tested one of seven innovations previously unknown in Haiti on their own farms. There were no subsidies provided and farmers could only get the materials by going to a local farm input supply store and purchasing the item at an estimated price a vendor would charge. Once the items were commercially available, no further efforts were made to encourage farmers to purchase them.

We present here an overview and description of the formal agricultural input system in Haiti derived from a survey of vendors. We examined the availability and origin of input supplies, price-setting and input acquisition strategies, dealers’ relationship with customers, and challenges facing store owners. The research was conducted in the USAID Feed the Future (FTF) West Corridor, an area that is an important foodshed for the capital, Port-au-Prince, and inhabited by large rural populations, the majority of which are farmers (Figure 1). We summarize what we know of the formal input sector in Haiti from the literature, describe the methodology used, and present our findings. We conclude with a series of recommendations that address the constraints in supply chains in developing nations, including Haiti.

Figure 1.

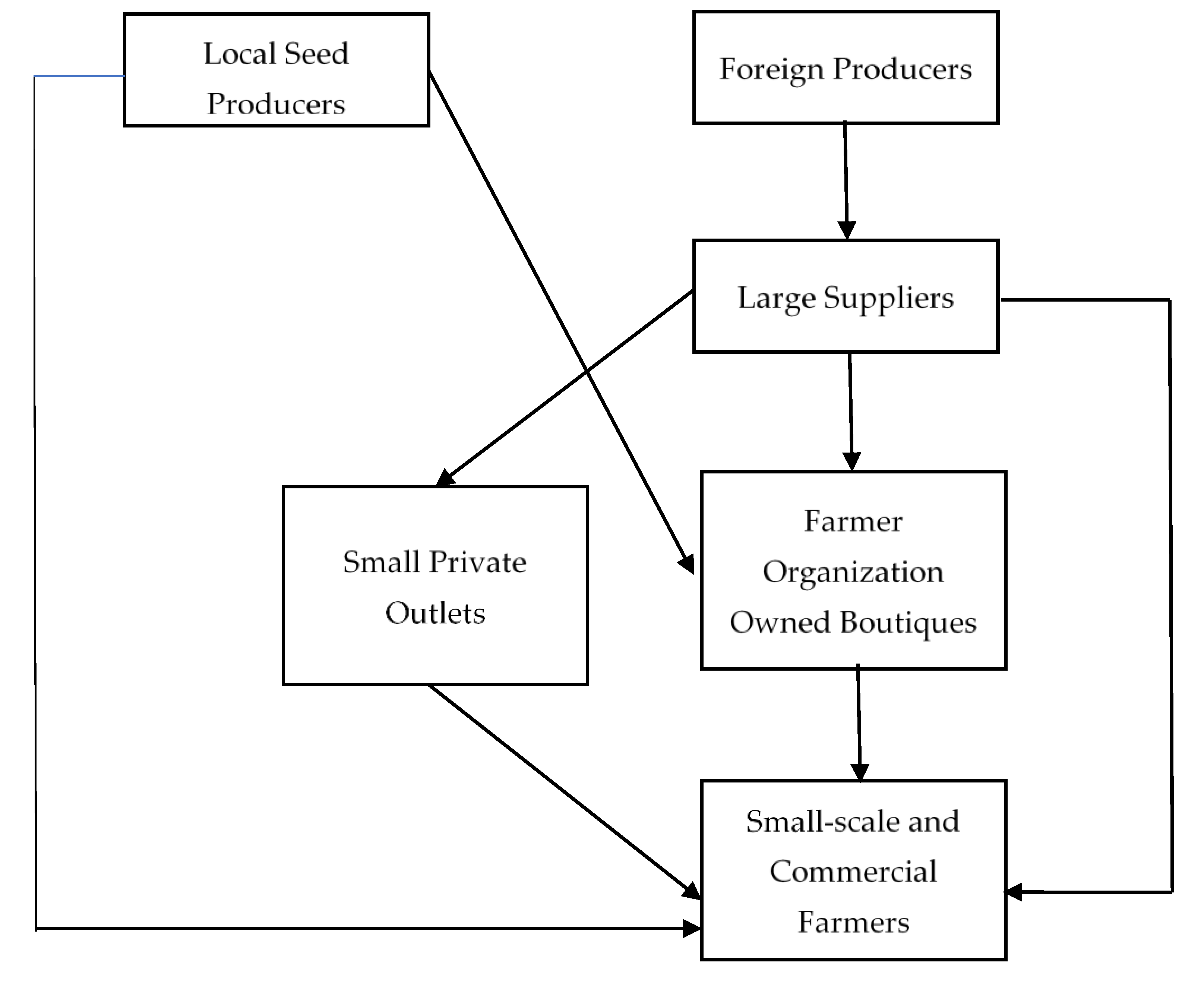

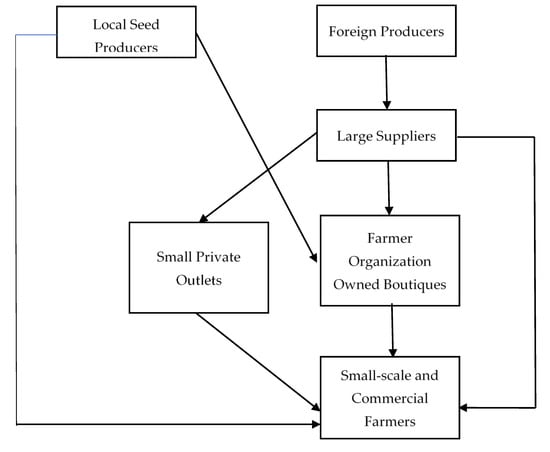

An overview of the agricultural input supply chain in Haiti.

2. The Formal Input Sector in Haiti

The few studies that are available about the formal input sector in Haiti, most of which focus on the seed sector, describe a sector that is underdeveloped and unregulated [14]. Many governmental institutions in charge of regulating the sector are either underfunded or dysfunctional. For instance, the National Seed Service (SNS) is understaffed and does not have the capacity to engage in certification activities, its most basic duty. As a result, much of the certified seed in Haiti comes from the Dominican Republic and other countries. Haiti has tried to establish a complete set of formal sector structures [14] in the past, but lack of access to needed resources and decades of poor governance have undermined these efforts.

Previous assessments conducted in Haiti [14,15,16] show that, similar to other developing countries, farmers often do not purchase inputs from formal sector stores. The most recent assessment of the seed supply system in Haiti conducted after the 2010 earthquake [14] showed that more than 90% of farmers acquired seeds through informal venues. Sperling et al. posit that the high price of inputs, farmers’ inability to differentiate between seeds and grains in local markets, and the distance of input supply stores from rural communities are key factors that explain farmers’ limited use of formal outlets [14].

Nonetheless, the formal sector in Haiti remains an important acquisition channel for many farmers. Sperling et al. (2014) found that the formal outlets are farmers’ preferred channels for the purchase of rice, vegetables, and other horticultural seeds. For these crops, improved varieties and high-quality certified seeds are readily accessible in sales outlets run by farmers’ associations and in local private sector input stores [14]. The formal sector also plays a vital role in the provision and distribution of fertilizer in rural areas. Private companies import many of the fertilizers used in Haiti from other countries, the Dominican Republic being the major supplier. Organic fertilizers, for which there is a good market, are readily available in adequate quantity in most formal stores. However, the limited range of fertilizers available is problematic, often making it difficult to find the most suitable fertilizer for a particular crop or soil condition [14].

3. Methodology

Our research focuses primarily on the input supply chain, the “upstream” chain in Reardon’s dendritic concept of the food production system. Personnel working in formal input stores, owners of input stores, and input importers provided the data reported here. We conducted a preliminary investigation to gain an overview of the supply chain in the study region and compile a list of potential participants prior to data collection. Local informants knowledgeable about and familiar with the Haitian formal agricultural input sector in the area provided contact information for 34 input suppliers who were potential respondents.

We then used referral or respondent-driven sampling (snowball sampling) to identify additional potential respondents. In referral sampling, each respondent provides contact information for other potential respondents. Referral sampling is used to identify potential participants when there is no existing list of members of the target population, which was the case for this study [17,18]. It is particularly useful when the potential participants interact with each other directly and/or indirectly, forming a network. This is the case for the businesses and individuals that comprise the formal sector input network in Haiti. Referral sampling may be problematic for large scale studies when there is an array of differing subsets in the target population. Bias can result if the original seed, the first group of people identified and contacted, fails to include members of all subsets in the population [19]. This was not a potential issue in this study because the target population is small and clearly defined. Referral sampling is often used to identify “hard to reach” populations and can be subject to bias due to nonresponse when the research concerns illegal or socially undesirable behaviors or illnesses that carry stigma or shame [20]. The topics of concern in this study were not of a sensitive nature and referral sampling has been extensively used to recruit key informants and participants in studies of agricultural systems when no sampling frame exists [21,22,23,24]. This research was conducted under the University of Florida IRB201601294 (Understanding the Formal Agricultural Input System in Haiti) and respondents were under no obligation to provide additional contacts.

Over the course of four weeks, we conducted interviews with 22 store owners or operators in the FTF West Corridor. We used a mixture of open and closed response items to explore the availability and origin of input supplies, price-setting and input acquisition strategies, dealers’ relationship with customers, and challenges facing store owners, among other topics. The sample consisted of one large privately-owned store, one small privately-owned store, and 20 small stores owned by farmers’ organizations. Most of the large and small privately-owned stores that we contacted did not agree to participate in the interviews. There are only three large input stores in the country and even small privately owned stores are relatively rare compared to the farmer organization-owned stores. The small farmer association-owned stores comprise the majority of input stores in the region and provide inputs to farmers outside the semi-urbanized area where the large and small privately owned stores occur. They provide most of the coverage for the inputs Haitian farmers in the region typically rely upon. These operators did participate in the interviews and represent the totality of active farmer-organization owned stores in the area under study. We conducted the study in three agricultural regions in the FTF West Corridor, involving eight operators in the Bas-Boën/Thomazeau (hereafter, Bas-Boën) region, seven in the Montrouis/Arcahaie/St. Marc (hereafter Montrouis) region, and seven in the Kenscoff/Petion-Ville (hereafter Kenscoff) region. The Kenscoff region is immediately proximate to Port-au-Prince and the large and small privately-owned stores we contacted were in this region. There are important differences in agricultural production, market accessibility, and input acquisition across regions in Haiti [25]. Van Vliet et al. found a significantly diverse agricultural production system in Haiti; 32 types of production system spanning over 4 types of agricultural zone; in terms of market accessibility, only 193 out of 571 municipality sections were classified as having good or relative proximity to basic market infrastructure and agricultural services [25]. We therefore exercise caution in extrapolating the specific results we found to the overall agricultural input system in Haiti.

4. Structure of the Formal Input Sector

Our findings unveil a formal agricultural sector in Haiti that is more structured and better established than previously thought, although still underdeveloped and heavily centralized. Contrary to popular belief, there are numerous stores that have a wide range of agricultural inputs available for sale in quantity, including seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, nursery supplies, and tools. Farmers can acquire inputs from all three types of suppliers included in our sample. We identified three large, privately owned suppliers that import most of the agricultural inputs available in Haiti and often have exclusive distribution agreements for the products they import. These suppliers constitute the point of entry of inputs into the distribution system as a whole. Small privately-owned stores and stores operated by farmer organizations, or on occasion relief or assistance organizations, get the inputs they sell from these large suppliers. The large suppliers have a well-maintained agro-dealer network of small stores that are concentrated in urban and semi-urban areas and are fairly isolated from farming communities. The small, local stores consist mostly of dealers who purchase from the large suppliers for retail sale to farmers (Figure 1). There are a few plant breeding and screening programs run by NGOs that could also be a source of inputs into the system, but their contributions to the supply chain are minimal and there is no evidence of synthetic input production within the FTF West Corridor.

The small stores run by farmers’ organizations present a unique and interesting case. Twenty of the 22 store operators that we interviewed were associated with farmer organization-owned stores. Many of these small stores are supported by the FTF Haiti Chanje Lavi Plantè (CLP) project. USAID funded the CLP project for three years (2015–2018) with a mandate to improve the agricultural sector in Haiti by increasing productivity and strengthening the capacity of local organizations. This project builds on the results of a prior agricultural development project in Haiti, FTF West or WINNER (Watershed Initiative for National Natural Environmental Resources). These stores appear to have a uniform business model. Although owned by an entire organization, a board member, often the president, runs the store. This individual receives some business management training from CLP and the project supplies the inputs that the store sells, such as pesticides, tools, fertilizer, and seeds. The partnering stores procure inputs from CLP at a discounted price as part of the project initiative to increase organizational capacity. The stores then sell these inputs for a profit that is often reinvested into the business or community ventures of interest to the farmer organizations. These stores are typically located in rural areas and provide poor and small-scale farmers with access to formal inputs, including improved varieties. These organization-owned small stores are part of USAID’s efforts to stimulate the establishment of more input stores in the country and formalize the input system. The majority of stores we studied have been in business for two to ten years (77%), while 14% have been in business for more than ten years and 9% for less than two years.

5. Structural Effects on the Availability of Inputs

A major objective of this study was to characterize the availability of input supplies in the formal sector, specifically the inputs that are available for sale in formal stores, the sources of these inputs, and basic information about the inputs like brand or variety. We identified four general categories of commonly marketed inputs: pesticides, nursery supplies and tools, fertilizers, and seed. None of the suppliers reported sales of animal feed. Most of the inputs are imported and arrive packed and ready for distribution. Most stores get their supplies from three large local suppliers, Darbouco, AgroService and CoMag, but USAID’s contribution through CLP plays an important role as well (Table 1). These suppliers import most of their inputs from post-industrial countries like the United States and China, but the Dominican Republic is a significant source in Haiti because of the ease of moving products imported into the Dominican Republic into Haiti. The three large private sector suppliers in Haiti often have exclusive distribution agreements with their international suppliers.

Table 1.

Primary sources of materials in the formal input system in Haiti for the four most commonly purchased inputs.

There, the degree of concentration in sales of different inputs varies by type of input. For example, pesticide sales are concentrated. Of the 22 store operators interviewed, 11 said they get pesticides from AgroService and 13 said from Darbouco, some from both. Four large scale distributors, including CLP, account for 81% of pesticide sales. On the contrary, suppliers other than these four major importers account for nearly half (47%) of seeds distributed through the formal sector suppliers. Bean seed is particularly important in Haiti and some bean varieties have been developed locally, such as Lore 249 and Lore 254 developed by the Haitian-based non-governmental Organization for the Rehabilitation of the Environment (ORE), www.oreworld.org/seed.htm (accessed on 25 September 2021). Agricultural development programs have introduced other important crop varieties to Haiti. For example, the Government of Taiwan brought the TCS-10 rice variety to Haiti as part of a project to develop an efficient rice production system in the country. The distinct pattern of sourcing for seeds may reflect the importance and impact of breeding programs supported by USAID, other international donors, and Haitian-based organizations like ORE.

Fertilizer options available to Haitian farmers are limited, especially in rural stores. Our survey recorded only four general types or mixes of fertilizers: urea, a standard complete mix, foliar-applied powders, and diammonium phosphate (DAP). Haitian agricultural professionals have expressed concerns about the limited choices because the few types of fertilizers available fail to address the differences in nutrient deficiencies across regions [14]. The dominance of a single supplier, AgroService, in supplying fertilizers may contribute to the limited options available in the country.

The three large private sector sources clearly dominate supplies of the two types of inputs that require the greatest technological capacity in their production: fertilizers and pesticides. This stands in clear contrast to inputs that can be produced with less industrial capacity, inputs that may represent opportunities to enhance in-country production as seems to have occurred in the case of bean seed. However, a strict focus on seeds is problematic because improved seeds typically require better nutrition and pest management than local or older varieties. The three innovations are linked, and agricultural research and development must address all three.

6. Demand and Supply Relationships

Another objective of our study was to better understand how well the formal input stores respond to demand for inputs. We first asked store owners to list their fastest moving inputs to gain insights about sales. Store operators in the three production zones in the Corridor listed roughly equivalent numbers of items in high demand, although providers in the Montrouis region listed only 16 high demand products. Vegetable crop seeds are by far the input with highest demand in the FTF West Corridor, with bean, leek, cabbage, and sweet pepper outstripping other vegetable seeds sold (Table 2). Stores in the Montrouis region note far fewer seeds as high demand products. Overall, fertilizers and pesticides were listed as high demand products far less frequently than seed. It is striking that only one store in the Kenscoff region said fertilizer was a high demand product given the number of seeds listed as high demand products by operators in that region. Given the importance of fertilizer to successful horticultural crop production, these discrepancies suggest that concerns of farmers, store operators, and agency personnel regarding fertilizer availability in Haiti are well justified. Pesticides, often another critical input for horticultural production, were rarely listed as high demand products.

Table 2.

Agricultural inputs in greatest demand in the 22 stores included in this study by type of input and region in the Feed the Future West Corridor.

We also asked operators to list items that are least in demand (Table 3). Carrot seeds and hoes were most frequently listed as the slowest moving inputs, each identified by four supply store operators. Vegetable seed as a whole constituted the most frequently indicated type of input for both the highest and lowest demand products, but cabbage, grown mostly in Kenscoff, was the only specific seed identified as both a high and low demand input. Five store operators said demand was high, none in the Bas-Boën/Thomazeau region while the two that said demand was low were in the Bas-Boën/Thomazeau region. There are no other contradictions in the two sets of responses regarding demand for seed. More vegetable products are listed as high demand (38 responses) than low demand (20 responses). No operator indicated any tool as a high demand input while nine respondents said tools are not high demand. On the contrary, the demand for fertilizers (Table 2) is high. Only one type of fertilizer, diammonium phosphate or DAP, was cited as a low-demand product (Table 3), a surprising result given that the International Plant Nutrition Institute lists DAP as the most commonly used phosphate fertilizer globally (www.ipni.net/specifics (accessed on 25 September 2021), bulletin #17). Few operators listed pesticides as either high or low demand products.

Table 3.

Agricultural inputs in least demand in the 22 stores included in this study by type of input and region in the Feed the Future West Corridor.

We found that demand often outstrips the supply of inputs. We asked store owners if there are times when there is demand for an input that is out of stock. Over one third (38%) of respondents said this occurs frequently and another 43% said running out of stock sometimes occurs; a total of 81% of respondents. When we asked store operators to indicate the major factors that affect their decisions about what products to carry, 19 of the respondents (86%) said they make their decisions based on demand for a product. These findings indicate that the Haiti formal input supply system in the region where we conducted this study, which is the main foodshed for the capital Port-au-Prince, is unable to regularly meet farmer demand for key production inputs. This suggests that inadequate input supplies impede increased agricultural productivity and profitability in this critical region of the nation characterized by high population density. This region is also the site of the major port in Haiti. The inability of the input supply system to meet farmer demand for inputs reliably also limits the potential for Haitian farmers to successfully take advantage of the port facilities to gain entry into the international food chains, especially the lucrative food chains for high value vegetable and fruit crops.

To gain insights into the dynamics of product availability over time, we asked participants if they no longer carry some inputs that they sold five years ago. Almost half of respondents said that they had not dropped an item from their inventory. Somewhat surprising, one respondent discontinued six types of seeds (cabbage, eggplant, okra, chili pepper, sorghum, and tomato). Two other respondents dropped work boots and hoes and one respondent listed knives as items that they no longer carry. Overall, pesticides were the most commonly dropped input, especially malathion, which was dropped from inventory by seven respondents. The CLP encourages store owners to refrain from selling malathion because of the danger it poses to human health. Four other products, the herbicides glycel and goal and the pesticides ridomil and curacron, were also discontinued by store operators for the same reason. This is an example of the role that donor policies can play in influencing the products that are available through the input supply chain in a country, ultimately affecting the supplies available at the local level. The decisions to discourage the use of these products are based on valid, reliable scientific evidence of the potential harm to the human population. However, in developing nations more contemporary products that come to market to treat the same pests may not become available or may be too expensive for farmers to use. Further research to determine how to achieve the dual goals of human health and safety and adequate control of weed, insect, and disease pests is needed; research that specifically addresses the issues associated with little or no in-country production combined with a limited number of importers.

Revenues are obviously important in store operators’ decisions about what products to carry. We asked respondents to identify the major sources of revenues in their stores (Table 4). Seeds and fertilizers were by far the most frequent responses, mentioned by every respondent. Respondents said that urea fertilizers and bean seeds are the most profitable of all inputs. Pesticides ranked third but were a major revenue source for a few respondents. The strong role of seeds and fertilizers is not surprising. Improved seeds typically respond well to fertilizer. The investment in seeds encourages greater use of fertilizers. This leads farmers who buy improved seeds through the formal sector to also purchase fertilizers to take full advantage of the potential production gains of the improved seeds. This is another example of the connections between different components of the input supply system that link investments and farmer decisions. Change can be slower than seems logical because farmers face risks that mitigate against rapid adoption of new crops, varieties, or management practices. In practice, farmers often demand products that they have used before with good outcomes and farmers may be reluctant to experiment with new varieties, which can introduce unknown risks into the production system. As a result, stores often carry only a few specific, well-known inputs in each category of inputs. For instance, only two varieties of carrot seeds, Chantenay Red Core and Kuroda, can be found on the market.

Table 4.

Products comprising major sources of revenue in the 22 stores included in this study by type of input and region in the Feed the Future West Corridor.

7. Clientele Factors and Relationships

No assessment of the formal sector would be complete without an examination of the stores’ clientele and the retail relationships. We identified four categories of customers who frequent the formal outlets: small scale farmers, larger scale farmers, other input dealers, and traders. Sales to small farmers are by far the most important revenue stream and the largest source of income. Eleven storeowners (50%) indicated that 80% to 100% of their revenues come from sales to small farmers and another 42% said that 40% to 60% of revenues come from small farmers. Other revenue streams are small, accounting for no more than 40% of revenues and consisting of only a few stores. Only one store reported revenues from the government or NGOs, accounting for up to 40% of revenues. Six stores reported sales of 20–40% to large farmers and three reported sales of 20–40% to traders. Three respondents sell small quantities of inputs to other input suppliers, but this accounts for less than 20% of total revenues. Overall, the private sector input supply chains depend largely on the purchases made by small farmers.

These findings show the importance of improving input supplies for the small farm sector and suggests that interventions at multiple scales may be needed. Regionality is also important. The FTF West Corridor is a relatively small geographic area. It is uniform in some senses, particularly due to its relatively good dependability of rainfall in most of the region and proximity to the nation’s capital. Direct sales to the Port-au-Prince market is feasible for small farmers in the Corridor. Yet, despite the homogeneity of the Corridor in these respects, our data show that there is considerable variance in the kinds of inputs that are provided and the kinds that are in demand. Tailored programs that target specific regions and specific farming systems are likely to be critical to improving Haiti’s domestic food supply and potentially improving Haitian connections to international, high value food supply chains.

Communication between suppliers and clients is a critical component in building food supply system capacity and improving the quality of performance. The suppliers we interviewed promote their businesses through several channels, but direct contact is an element in most advertising. Meetings organized by farmer organizations specifically to provide information were the most common method of advertising (41%), but other kinds of meetings like trainings by extension personnel, demonstrations, promotion by people associated with USAID, and marketing by members of the associations were also mentioned. Given that most of the stores in our sample are farmer organization-owned, these kinds of educational and information or “outreach” meetings are a logical way to inform people about the products available through local stores. Advertising that did not involve direct, individual contact is rare. Seven respondents said that they use megaphones mounted on vehicles (31% of stores) and one used radio advertisements. Marketing appears to be successful. Store owners reported that an average of 68 clients visit their stores each day during peak sale periods. On average, 55% of these individuals are women and 69% come from nearby towns. Credit may play a role as well, but this is not clear. We found that most storeowners (68%) do extend credit or some form of repayment scheme to clients. However, such practices are limited to a few trusted clients and are not methods of recruiting new clients. Given the economic volatility in Haiti, extending credit is a high-risk prospect. More detailed information is needed to determine the degree to which credit is a viable option for improving the input supply system, perhaps by concentrating on ways to reduce the inherent risk to the supplier.

8. Key Constraints

Formal agro-input outlets in Haiti face numerous constraints that affect their operations and hinder the development of the formal sector. They also impede other positive outcomes like the adoption of improved technologies by small farmers. We assessed these constraints from the store owners’ perspective, asking the participants to select the top three problems they face from a list of seven options. Three responses were far more frequently mentioned than other constraints.

Depreciation of the gourde, the local currency, was the most frequently cited constraint. Of the 22 storeowners interviewed, 18 (81%) reported that the continuous increases in the exchange rate have directly affected their businesses. From 2010 to 2020, the exchange rate went from 40 to over 100 gourdes per US dollar. The ongoing devaluation of Haitian currency over many years has increased risk greatly for store owners, causing many formal outlets to lose customers and revenues due to the constant rise in the price of imported inputs. In 2020, the Haitian government revalued the gourde and the exchange rate fell to 63 gourdes per dollar, a decrease of nearly 50%. The long-term effects of revaluation are not yet apparent, but one immediate effect was to reduce consumer buying power in Haiti. This sounds counter-intuitive, but a high percentage of the total fiscal resources of Haitian families and businesses are held in US dollar accounts, in part because of the critical role of remittances from kin living abroad for Haitians. These US dollar accounts were essentially “devalued” by the government’s revaluation of the gourde. Intermediate to long term effects are not clear, but the rate remained stable only briefly, reaching almost 100 gourdes per dollar by mid-2021 (www.xe.com/currencyconverter/ accessed on 25 September 2021).

Store owners cited the timely acquisition of inputs during planting seasons as the second greatest constraint to business operations. More than half (55%) of the respondents listed problems with getting agricultural inputs when needed as a major constraint. This is an important problem for small private sector stores. A few store operators who rely mostly on the CLP project also complained that seeds sometimes arrive after the planting season. Some respondents said that there were times in recent years when fertilizers were not available for sale and/or were not available through the private sector markets for many months. However, some participants attributed the scarcity of fertilizers more to political dissention than market-induced scarcity. Constraints to securing inputs create high-risk conditions for farmers anywhere, and in places like Haiti, where many risks to production accrue, the results can be devastating. Farmers can ill afford to try new innovations, which inherently carry some risk, under conditions of recurring instability in the input supply system.

Inadequate working capital to expand business operations is the third most cited constraint facing the formal outlets. Kelly et al. address the role of input suppliers in addressing input constraints and their research focuses on the potential for increasing use of agricultural inputs through the growth of private sector input suppliers [26]. Their model [26] (p. 383) of constraints among suppliers include six factors that have strong effects on supply input, four of which emerged in our study: (1) the supplier’s perception of effective demand, (2) capital needed to stock inputs, (3) in-country access to the needed inputs, and (4) cost of transportation. We found that suppliers rely heavily on past purchases to guide decisions about what inputs to carry. This may lock the supply system into a cycle in which suppliers are reluctant to carry new products, thereby limiting farmers’ opportunity to try new technologies, ultimately perpetuating demand for traditional, potentially outmoded, inputs. Businesses typically gain access to working capital through credit, and a lack of credit can be a major constraint to expansion of the input supply system. In this study, 41% of the store operators commented on the need for greater working capital. Shuaibu and Nchake examined the effect of the credit market on agricultural performance in Sub-Saharan Africa and found that low lending rates and credit for the private sector were significant factors in agricultural development in four sub-regions [27]. Their findings suggest that the poorly developed credit market in Haiti is a barrier to increasing input use because it affects both demand by farmers and supply. The reliance in Haiti on two major importers of agricultural inputs may be a major bottleneck in input supply and especially in the variety of inputs that are imported. Similarly, the cost of transportation is a critical barrier both to getting inputs to rural communities and for farmers to get their products to lucrative markets, even in the FTF West Corridor in proximity to Port-au-Prince.

Few farmers mentioned constraints other than the three top-cited problems discussed above. The rarely mentioned limitations include insufficient storage space, consumer debt default, shipments stalled in customs, and the high costs associated with port operations. Other issues such as robbery and low customer turnout that often affect formal outlets in other regions of Haiti are rarely mentioned in the Corridor, although three respondents did say that crime and robbery are a major constraint. Only one respondent said low demand for inputs is a major concern.

9. Discussion: Challenges and Possible Remedies

Despite repeated efforts to improve in-country availability and economic accessibility of inputs, poor access to agricultural inputs remains a persistent problem across the global south. In the context of Haiti, formal stores can play an important role in providing quality inputs at the right time and, therefore, have significant potential to transform the agricultural sector. These stores, however, face three major challenges to growth and efficacy.

Challenge 1: Barriers to Acquiring Improved Varieties. Near monopolization of imported inputs by a few larger companies who have the capital and the organizational power to purchase inputs on the international market and bring them into a developing country is a more complex issue than it may seem. The limited array of agricultural inputs that are available in developing nations is the result of many factors, one of which is protection of intellectual property rights (IPR). Protecting novel inventions through patents or other measures is, with some exceptions, the norm in North America and Europe and the U.S. Patent Office and similar governmental bodies in other nations provide comprehensive patent protection.

Protection of IPR for plant seed and planting materials is especially complex, driven by changes in plant breeding capabilities and evolving over time in the United States and most other post-industrial nations. Lesser identifies three distinct steps in the historic process [28]. In 1930, the Plant Patent Act (PPA) established patents on asexually propagated plants. Forty years later, the Plant Variety Protect Act (PVPA) extended patenting to sexually propagated plants. In 1985, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office ruled that open-pollinated seeds are patentable. This last step created a “utility patent”; a class of patents that applies to virtually any plant that plays a functional role in agricultural production [29]. In the United States, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) grants utility patents through Certificates of Plant Variety Protection based on three required traits: novelty (it is a distinctive product), uniformity (breeds true to type), and stability (holds true over multiple generations).

As a result of this legal structure, seeds patented in North America and Europe, and increasingly other areas of the world, require some form of monitoring and patent protection to ensure the patent rights of the individual or organization that produced the product, no matter where they are used. While the World Trade Organization allows WTO members to exclude plants from patents, the organization does require member states to provide protection for intellectual property associated with development of plant varieties, either through plant variety protection or patents [30] (p. 355). Some developing nations have entered into agreements with various countries to ensure that patents by either party are respected [31] (pp. 123–126).

Patent rights expire after 20 years, at which time the product can be used by anyone to develop new products. Many of the varieties in the stores fell into this category, such as Roma tomato and Cal Wonder pepper. In the interim, private companies generally will not authorize sale of their patented seeds in other nations unless there are formal agreements in place to protect the product from unauthorized use [32]. Vendors of agricultural inputs in general, and especially seeds, must have confidence that the legal measures needed to protect patented products are in place and enforceable. However, even if agreements are in place, vendors may question the ability of the government in the importing nation to impose punitive charges or institute other measures that are strong enough to prevent violations of the agreements. These legal issues can be a major obstacle to obtaining the most recent varieties created in nations where plant patenting is the norm. Further, the cost of recently patented seed is often very high compared to existing varieties. Maisashvili et al. report that seed prices increased as much as 30% annually in the years just prior to 2016 [33] (p. 4). Cost alone can be a significant barrier to bringing the newest releases into international markets unless there is strong evidence of a viable market for the seed. However, some of the first genetically modified varieties are now available at greatly reduced cost because the 20-year patents have expired. The effect of availability of these “generic GMO varieties” remains to be seen.

There are alternatives to improve the variety of seeds and other inputs available to farmers in Haiti and other developing nations. One is to build national capacity to test varieties under the biophysical and management systems in the nation. That is, focus on identifying the existent, patent-free varieties that will best meet the needs of the national system, including farmers, marketers, and consumers. The trials conducted at local field experiment stations as part of the AREA project are an example of this approach. It is a faster road to getting good seed to farmers than breeding new varieties in many cases and requires less technical infrastructure, time, and expense than breeding programs do.

It may also be as or more important to build the national infrastructure needed to produce certified seed than focus on plant breeding. The distinction between seed as a planting material and seed as a food item is not well established in many countries, including Haiti. Seed used for planting requires careful storage, for example, including limited exposure to high humidity and temperature in most cases. Farmers in developing nations often routinely increase the seeding rate because they assume that only some of the seed planted will emerge and survive, which increases their costs of production. Laboratory testing and establishing a seed certification process could go a long way towards improving seed quality for farmers. In Haiti, some NGOs and rural research and education centers set up under the WINNER project do increase seed supplies for agronomic crops like corn, sorghum and beans. These are then sold by the organizations and generate revenues for these organizations. However, there is no seed certification process in Haiti to ensure the quality of these seeds.

Challenge 2: Limited types of inputs available. The limited range of products available in the seed sector is just as much a constraint as the types of fertilizers and pesticides available to farmers through the private input supply system. The fertilizers carried consist largely of urea as a nitrogen source and fertilizer mixes that include different percentages of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Based on our data, none of the commonly carried fertilizers contains other important plant nutrients like calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. Our data indicated that suppliers essentially carry the products that have high demand, which is logical. However, this approach to input supplies assumes that farmers are aware of all or at least the most important potentially useful products for their production systems. This is rarely the case, even in countries where farmers can easily access technical databases. Farmers may not demand fertilizer and pesticides that are unavailable because they do not know about them, especially under conditions of limited professional private crop consultants and public extension services. This creates a closed loop in which historically popular products remain the primary inputs carried by input suppliers, stifling the opportunity to take advantage of products that are not well known in the country. This is the case in Haiti. There is some risk to trying new products for both farmers and input suppliers, which can further depress interest in new products. Subsidies have historically been used to reduce risk and encourage technological change by farmers, but less attention has been devoted to the risk environment of input suppliers. This is especially true for suppliers in developing nations where factors like unstable currency valuation and poor transportation infrastructure enhance risk for input suppliers just as they do for farmers.

One potential avenue to encourage change is to reduce the risk associated with adding products to a vendor’s well-established inputs that farmers know and will buy. We introduced new products into the input supply system in the study region in the AREA Project research concerning farmer adoption of new technologies. As explained above, farmers could get these products only by purchasing them from an input supply store and the offer prices were not subsidized. To reduce risk for the input suppliers, we offered them the ability to pay for the items after they were sold, and we paid the store operators to maintain records regarding the sales of the products. A modified version of this approach could be tested over a period of possibly two to four years. This would allow suppliers to assess the risk associated with a particular new product without having to invest operating capital or allocate scarce storage space to items that may not sell. The trials could be limited to a few stores in different regions of a country in order to understand regional differences in potential demand. The results could then be used to convince other suppliers to incorporate the new products where appropriate.

The many input supply stores operated through farmer associations and non-profit organizations in developing nations may offer approaches to increasing seed availability that are rarely used in post-industrial nations. For example, increasing in-country seed production by farmer associations and other non-profits can alleviate problems of seed availability and quality. The AREA Project worked with local nonprofit organizations that have land set aside for research, training, and outreach activities to develop seed multiplication programs that were successful [34]. A more holistic approach to increasing in-country seed production based on Reardon et al.’s concept of food and agriculture systems as “dendritic connections” of multiple interacting chains is applicable to improving in-country seed production [13]. Network analysis applied to the input supply and market chains could help identify the most crucial targets for increased seed production to ensure both quantity and quality of seed. This kind of approach, tied to a spatial analysis of key deficit areas, would help governmental and donor agencies focus on areas that are strategically important for the country.

Challenge 3: In-country transportation difficulties. Even when supplies are available in-country, getting the inputs to farmers often remains a challenge that adds time and cost to procuring inputs. Jayne et al. disaggregate the domestic market component of the farm-gate price of fertilizer into four types of costs, all of which apply in Haiti, and all apply to inputs other than fertilizer [35] (p. 296). The costs are: (1) costs incurred in coordinating exchanges among market actors; (2) costs associated with physical marketing functions like transportation, storage, and handling; (3) government costs like taxes or the burden of meeting state requirements; and (4) excess profits resulting from non-competitive behaviors by marketing entities. They concluded that reducing the high cost of exchange is critical in the three nations where they analyzed costs (Ethiopia, Kenya, and Zambia). Transport and handling costs accounted for 50% or more of total domestic marketing margins, compared to summed profits for the importer, wholesaler, and retailer of less than 10% [35] (p. 313). Reducing these costs is critical to the increased use of fertilizer.

Further, as we found in Haiti and others have found elsewhere, input stores tend to locate close to urban areas while most rural communities tend to be among the poorest and the least capable of getting needed inputs. Road improvements may be the best solution to poor transportation, but the investment needed is often not possible. Farrow et al. examined the potential for spatial targeting to improve the distribution of agricultural input stores in Malawi [36]. Their results indicate that this is a viable approach to making input supply stores more accessible for rural populations, especially those who are unlikely to have motorized transportation. Given the importance of farmer organizations in securing inputs for their members in Haiti [37] and other nations [38,39,40] and the number of supply stores operated by farmer associations globally, the kinds of spatial analyses that Farrow et al. utilized could be important in delivering new technology to farmers. Farrow et al. have developed the protocols and procedures to implement their two-phase analyses [36] (p. 696–697). This could be a low cost and effective addition to programs that focus on improving input use that is potentially fundable by both national agencies and international donors.

10. Conclusions

The study reported here builds on a modest but growing body of literature that explores the evolution and roles of formal sector input supply chains in developing nations. The literature from Sub-Saharan African nations is particularly relevant because the limitations and needs are strikingly similar to those of Haiti. Our observations support the findings of earlier research in several respects, such as the high cost in terms of both effort and money to get inputs into the country, the potential bottleneck of a few key importers, and the restricted types of inputs provided and options within each type, among others. Our conclusions also reflect and extend those of other researchers, adding to the small but important body of knowledge about input supply chains and their role in agricultural development. Overall, much more research is needed, particularly research that extends beyond descriptive studies like ours and most others to approaches that test alternative solutions to some of the impediments to supply chains that the literature reveals.

Input supply chains are as crucial as market chains in generating technological change in agriculture. While direct subsidies have been a common, perhaps the most common, approach to improving input supplies and distribution in developing nations, global experience suggests that other solutions are needed as well. A more holistic approach that employs multiple types of interventions is needed to generate transformative change in agriculture in the poorest developing nations, which include much of Sub-Saharan Africa and certainly include Haiti. In addition, more research focused on supply chain innovation is needed. We conclude that there is a need to employ approaches that bring together the strengths and assets of the public sector, the non-profit private sector, and the for-profit private sector. Increased attention on innovative policy measures that benefit all three sectors is a prerequisite for generating the kind of changes in supply chains needed to stimulate agricultural growth and development. Many of the problems facing individual suppliers can only be addressed at the regional or national level, making policy particularly important, especially in nations where both public and private funds for investment are severely limited.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and M.E.S.; methodology, B.A. and M.E.S.; validation, M.E.S. and R.K.; formal analysis, B.A.; investigation, B.A.; resources, M.E.S. and R.K.; data curation, B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A., M.E.S., and R.K.; writing—review and editing, B.A., M.E.S., and R.K.; visualization, B.A.; supervision, M.E.S.; project administration, M.E.S. and R.K.; funding acquisition, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the cooperative agreement no. AIDOAA-A-15-00039. The contents are the responsibility of the University of Florida and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The University of Florida Internal Review Board (IRB-02) approved this study with Exempt status on 4 September 2016. The study consisted of an inventory of the agricultural inputs available for sale in commercial venues in the study region in Haiti. The IRB review provided this explanation of the exempt status: “This study is approved as exempt because it poses minimal risk and is approved under the following exempt category/categories… behavior. Information obtained is recorded in such a manner that human subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. Disclosure of the human subjects responses outside the research does not reasonably place the subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subjects financial standing, employability, or reputation.”

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The original survey forms are stored in a locked office at the University of Florida.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their support during the data collection phase: Lemane Delva, Absalon Pierre, Andrew Tarter, and Edzer Milord.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chadha, G.K.; Ramasundaram, P.; Sendhill, R. Is third world agricultural R&D slipping into a technological orphanage? Curr. Sci. 2013, 104, 908–913. [Google Scholar]

- World Food Programme. WFP Haiti Country Brief. June 2021. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000130459/download/?_ga=2.258807247.433027509.1631022161-1956004036.1631022161 (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Ainembabazi, J.H.; Abdoulaye, T.; Feleke, S.; Alene, A.; Donstop-Nguezet, P.M.; Ndayisaba, P.C.; Hicintuka, C.; Mapatano, S.; Manyong, V. Who benefits from which agricultural research-for-development technologies? Evidence from farm household poverty analysis in Central Africa. World Dev. 2018, 108, 218–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleta, M.; Kassie, M.; Marenya, P.; Yirga, C.; Erenstein, O. Impact of improved maize adoption on household food security of maize producing smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, N.M.; Smale, M. Impacts of subsidized hybrid seed on indicators of economic well-being among smallholder maize growers in Zambia. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril, J.; Abdulai, A. The impact of improved maize varieties on poverty in Mexico: A propensity score matching approach. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1024–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezu, X.; Kasssie, G.T.; Shiferaw, B.; Ricker-Gilbert, J. Impact of improved maize adoption on welfare of farm households in Malawi: A panel data analysis. World Dev. 2014, 49, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kassie, M.; Jaleta, M.; Mattei, A. Evaluating the impact of improved maize varieties on food security in rural Tanzania: Evidence from a continuous treatment approach. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Janvry, A.; Sadoulet, E. Agricultural growth and poverty reduction: Additional evidence. World Bank Res. Obs. 2009, 25, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E.F. Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered; Harper & Roe: New York, NY, USA, 1973; p. 305. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, C.M.; Barrett, C.B. The disappointing adoption dynamics of a yield-increasing, low external-input technology: The case of SRI in Madagascar. Agric. Syst. 2003, 76, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.; Kelly, V.; Jayne, T.X.; Howard, J. Input use and market development in Sub-Saharan Africa: An overview. Food Policy 2003, 28, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Echeverria, R.; Berdegue, J.; Minten, B.; Liverpool-Tasie, S.; Tschirley, D.; Zilberman, D. Rapid transformation of food systems in developing regions: Highlighting the role of agricultural research and innovations. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, L. Seed system security assessment: Haiti. An assessment. The United States Agency for International Development/ Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, 2014. Available online: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/seed-system-security-assessment-haiti (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Shields, W.H. A Subsector Analysis of the Improved Bean Market in Haiti. Master’s Thesis, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, E.; Brick, D. A Rapid Seed Assessment in the Southern Department of Haiti: An examination of the impact of the January 12 earthquake on seed systems. Catholic Relief Services, Washington, DC. 2010. Available online: www.crs.org/sites/default/files/tools-research/rapid-seed-assessment-southern-department-haiti.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Bernard, H.R. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Penrod, J.; Preston, D.B.; Cain, R.E.; Starks, M.T. A discussion of chain referral as a method of sampling hard-to-reach populations. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2003, 14, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gile, K.J.; Handcock, M.S. Respondent driven sampling: An assessment of current methodology. Soc. Methodol. 2010, 40, 285–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goel, S.; Salganik, M.J. Assessing respondent-driven sampling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6743–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bullock, R.; Gyau, A.; Mithoefer, D.; Swisher, M.E. Contracting and gender equity in Tanzania: Using a value chain approach to understand the role of gender in organic spice certification. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gcumisa, S.T.; Oguttu, J.W.; Masafu, J.M. Pig farming in rural South Africa: A case study of uThukela District in KwaZulu-Natal. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2016, 50, 614–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarbox, B.C.; Swisher, M.E.; Calle, Z.; Wilson, C.H.; Flory, S.L. Decline in local ecological knowledge in the Colombian Andes may constrain silvopastoral tree diversity. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Aggarwal, D. Potential risk factors of brucellosis in dairy farmers of peri-urban areas of South West Delhi. Indian J. Community Med. 2020, 45, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet, G.; Pressoir, G.; Marzin, J.; Giordano, T. Une Étude exhaustive et Stratégique du Secteur Agricole/rural Haïtien et des Investissements Publics Requis pour Son Développement. CIRAD. 2016. Available online: www.agritrop.cirad.fr/580373/ (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Kelly, V.; Adesina, A.A.; Gordon, A. Expanding access to agricultural inputs in Africa: A review of recent market development experience. Food Policy 2003, 28, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, M.; Nchake, M. Credit market conditions and agricultural performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Dev. Areas 2020, 54, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, W. The impacts of seed patents. North Cent. J. Agric. Econ. 1987, 9, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauss, D.J.; Veitenheimer, E.E.; Pomeranz, M. Protecting plant inventions. Landslide 2019, 11. Available online: www.cooley.com/-/media/cooley/pdf/reprints/2019/2019-08-13-protecting-plant-inventions.ashx?la=en&hash=1D1409BC5F1BFE9CA63C89F19D09B1A9 (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Tripp, R.; Louwaars, N.P.; Eaton, D. Plant variety protection in developing countries. A report from the field. Food Policy 2007, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.M.; Correa, J.I.; DeJonge, B. The status of patenting plants in the Global South. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2020, 23, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.U.S. Seed law history: A primer. Farm Press 2006. Available online: www.farmprogress.com/us-seed-law-history-primer (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Maisashvili, A.; Bryant, H.; Raulston, J.M.; Knapek, G.; Outlaw, J.; Richard, J. Seed prices, proposed mergers and acquisitions among biotech firms. Choices 2016, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- USAID/Haiti. Economic Growth and Agricultural Development Fact Sheet. USAID. 2020. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1862/USAID_Haiti_Economic_Growth_and_Agricultural_Development_Fact_Sheet_-_January_2020.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Jayne, T.S.; Govereh, J.; Wanzala, M.; Demeke, M. Fertilizer market development: A comparative analysis of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Zambia. Food Policy 2003, 28, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, A.; Risinamhodzi, K.; Zingore, S.; Delve, R.J. Spatially targeting the distribution of agricultural input stockists in Malawi. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Swisher, M.; Koenig, R.; Monval, N.; Tarter, A.; Milord, E.; Delva, L. Capitalizing on the strengths of farmer organizations as potential change agents in Haiti. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 85, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, T.; Spielman, D.J. Reaching the rural poor through rural producer organizations? A study of agricultural marketing cooperatives in Ethiopia. Food Policy 2009, 34, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellin, J.; Lundy, M.; Meijer, M. Farmer organization, collective action and market access in Meso-America. Food Policy 2009, 34, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mwaura, F. Effect of farmer group membership on agricultural technology adoption and crop productivity in Uganda. Afr. Crop. Sci. J. 2014, 22 (Suppl. S4), 917–927. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).