Research on Unrealistic Optimism among HoReCa Workers as a Possible Future Hotspot of Infections

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Unrealistic Optimism/Pessimism Bias and Its Presence during the COVID-19 Pandemic

1.2. The Hospitality Industry in a COVID-19 Era

1.3. The Goal of the Study

2. Study

2.1. Method

Participants and Design

2.2. Materials

Block 1-unrealistic optimism/pessimism assessment for COVID-19 infection. (Q1) How do you rate/judge the risk of being infected by coronavirus? (Q2) How do you rate/judge the risk of another person in your business being infected by coronavirus? (Q3) How do you rate/judge the risk of a fellow countryman in your country of residence being infected with coronavirus?Block 2-assessment/comparisons for self-protection by vaccination. (Q4) How likely is it that you will get vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine becomes available on the market? (Q5) How likely is it that another person in your business gets vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine becomes available on the market? (Q6) How likely is it that a fellow countryman in your country of residence gets vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine becomes available on the market?Block 3-assessment/comparisons for losing a job. (Q7) What are your chances of losing a job because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q8) What are the chances that another person in your business will lose a job because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q9) What are the chances that a fellow countryman in your country of residence will lose a job because of the coronavirus pandemic?Block 4-assessment/comparisons for bankruptcy in the industry. (Q10) What are the chances that the company you are working for will go bankrupt because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q11) What are the chances that the average company in your business will go bankrupt because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q12) What are the chances that the average company in your country of residence will go bankrupt because of the coronavirus pandemic?

3. Results

3.1. ANOVA Analysis

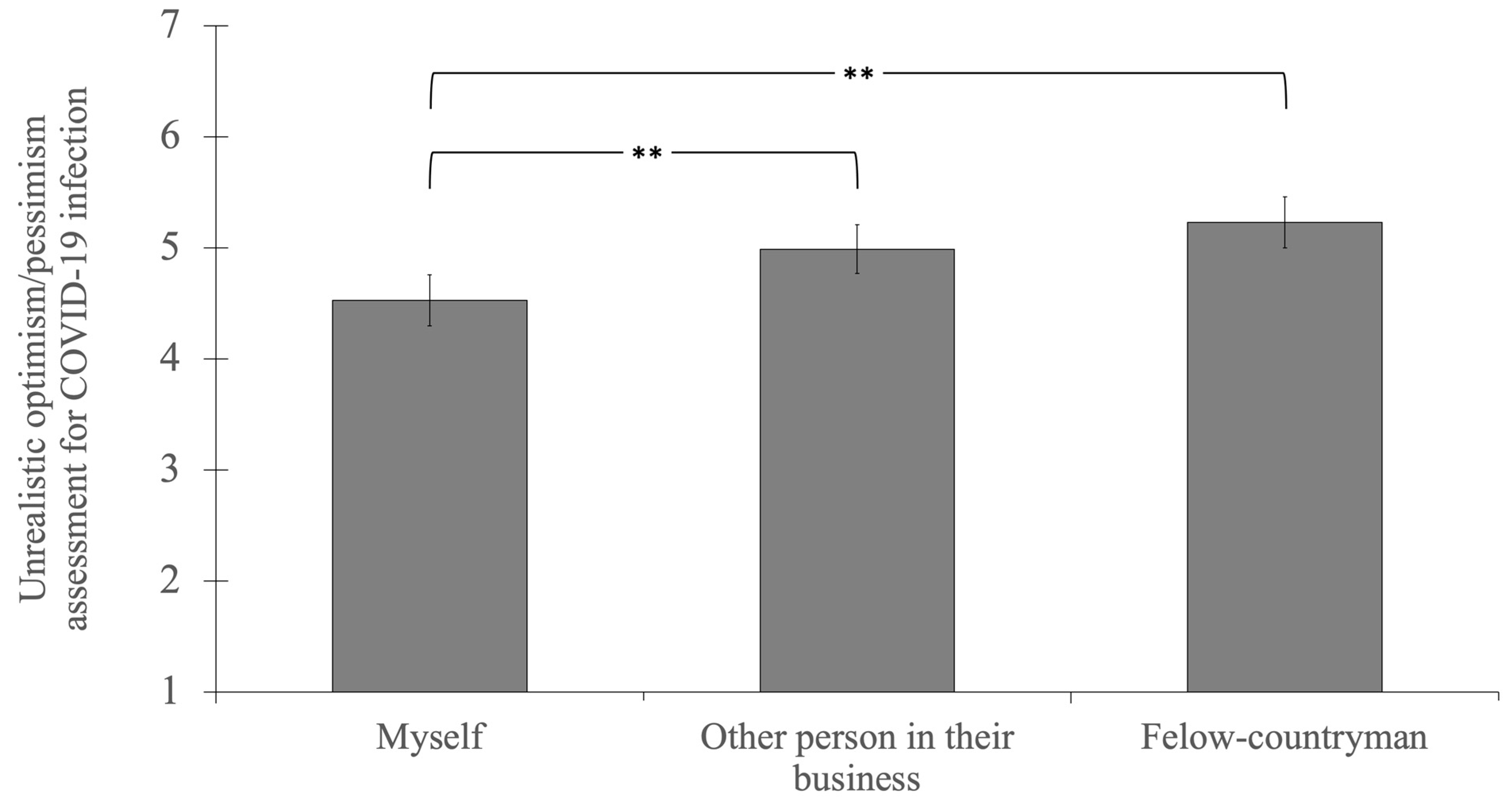

3.1.1. Unrealistic Optimism/Pessimism Assessment for COVID-19 Infection

3.1.2. Assessment/Comparisons for Self-Protection by Vaccination

3.1.3. Assessment/Comparisons for Losing a Job

3.1.4. Assessment/Comparisons for Bankruptcy in the Industry

3.2. Correlation Analysis

(Q1) How do you rate/judge the risk of being infected by coronavirus? (Q4) How likely is it that you will get vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine becomes available on the market? (Q7) What are your chances of losing a job because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q10) What are the chances that the company you are working for will go bankrupt because of the coronavirus pandemic?

(Q2) How do you rate/judge the risk of another person in your business being infected by coronavirus? (Q5) How likely is it that another person in your business gets vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine becomes available on the market? (Q8) What are the chances that another person in your business will lose a job because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q11) What are the chances that the average company in your industry will go bankrupt because of the coronavirus pandemic?

(Q3) How do you rate/judge the risk of a fellow countryman in your country of residence being infected with coronavirus? (Q6) How likely is it that a fellow countryman in your country of residence gets vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine becomes available on the market? (Q9) What are the chances that a fellow countryman in your country of residence will lose a job because of the coronavirus pandemic? (Q12) What are the chances that the average company in your country of residence will go bankrupt because of the coronavirus pandemic?

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pak, A.; Adegboye, O.A.; Adekunle, A.I.; Rahman, K.M.; McBryde, E.S.; Eisen, D.P. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.; Glaeser, E.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C. How Are Small Businesses Adjusting to COVID-19? Early Evidence from a Survey; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wańkowicz, P.; Szylińska, A.; Rotter, I. Insomnia, Anxiety, and Depression Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic May Depend on the Pre-Existent Health Status Rather than the Profession. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallapaty, S. What the Cruise-Ship Outbreaks Reveal about COVID-19. Nature 2020, 580, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, R.M.; Heesterbeek, H.; Klinkenberg, D.; Hollingsworth, T.D. How Will Country-Based Mitigation Measures Influence the Course of the COVID-19 Epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Hospitality Industry: Review of the Current Situations and a Research Agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Ouellette, J.A.; Fernandez, J.K. Abandoning Unrealistic Optimism: Performance Estimates and the Temporal Proximity of Self-Relevant Feedback. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, T.G. Predictive Properties of Analysis’ Forecasts of Corporate Earnings. Mid-Atl. J. Bus. 1993, 29, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Newby-Clark, I.R.; Ross, M.; Buehler, R.; Koehler, D.J.; Griffin, D. People Focus on Optimistic Scenarios and Disregard Pessimistic Scenarios While Predicting Task Completion Times. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2000, 6, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Waters, E.; Weinstein, N.D.; Klein, W.M.P. A Primer on Unrealistic Optimism. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic Optimism about Future Life Events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats, P.; Ferrer, Q.; Comas, C.; Rodríguez, I. Is the Addition of the Ductus Venosus Useful When Screening for Aneuploidy and Congenital Heart Disease in Fetuses with Normal Nuchal Translucency? Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2012, 32, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Raghubir, P. Gender Differences in Unrealistic Optimism about Marriage and Divorce: Are Men More Optimistic and Women More Realistic? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.K.; Niederdeppe, J. Effects of Self-Affirmation, Narratives, and Informational Messages in Reducing Unrealistic Optimism about Alcohol-Related Problems among College Students. Hum. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, F.P. It Won’t Happen to Me: Unrealistic Optimism or Illusion of Control? Br. J. Psychol. 1993, 84, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, H.F.B.; Tze-Ngai Vong, L. Hospitality Employees’ Unrealistic Optimism in Promotion Perception: Myth or Reality? J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 18, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.V.; Leffingwell, T.R. The Role of Unrealistic Optimism in College Student Risky Sexual Behavior. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2020, 15, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Brown, J.D. Illusion and Well-Being: A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoorens, V. Self-Favoring Biases, Self-Presentation, and the Self-Other Asymmetry in Social Comparison. J. Pers. 1995, 63, 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, W.M.; Weinstein, N.D. Health, coping, and well-being: Perspectives from social comparison theory. In Social Comparison and Unrealistic Optimism about Personal Risk; Bram, P., Buunk, F.X.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA; London, UK, 1997; pp. 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, C.; Helweg-Larsen, M. Perceived control and the optimistic bias: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Health 2002, 17, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Adjustment to Threatening Events: A Theory of Cognitive Adaptation. Am. Psychol. 1983, 38, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Positive Illusions: Creative Self-Deception and the Healthy Mind; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dolinski, D.; Dolinska, B.; Zmaczynska-Witek, B.; Banach, M.; Kulesza, W. Unrealistic Optimism in the Time of Coronavirus Pandemic: May It Help to Kill, If So—Whom: Disease or the Person? J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulesza, W.; Doliński, D.; Muniak, P.; Derakhshan, A.; Rizulla, A.; Banach, M. We Are Infected with the New, Mutated Virus UO-COVID-19. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 1701–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinski, D.; Gromski, W.; Zawisza, E. Unrealistic Pessimism. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 127, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.M.; Palmer, M.L. Changes in and Generalization of Unrealistic Optimism Following Experiences with Stressful Events: Reactions to the 1989 California Earthquake. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Administration Fast Facts: United States Travel and Tourism Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Fast%20Facts%202019.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Cajner, T.; Crane, L.; Decker, R.; Grigsby, J.; Hamins-Puertolas, A.; Hurst, E.; Kurz, C.; Yildirmaz, A. The U.S. Labor Market during the Beginning of the Pandemic Recession; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, S.; Ellingrud, K.; Hancock, B.; Manyika, J.; Dua, A. Lives and Livelihoods: Assessing the Near-Term Impact of COVID-19 on US Workers. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/lives-and-livelihoods-assessing-the-near-term-impact-of-covid-19-on-us-workers (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Huang, A.; Makridis, C.; Baker, M.; Medeiros, M.; Guo, Z. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 Intervention Policies on the Hospitality Labor Market. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Chi, O.H. COVID-19 Study 2 Report: Restaurant and Hotel Industry: Restaurant and Hotel Customers’ Sentiment Analysis. Would They Come Back? If They Would, WHEN; (Report No. 2). 2020. Available online: http://www.htmacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Covid-19-October-study-summary-report.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Gold, R.S.; Aucote, H.M. “I”m Less at Risk than Most Guys’: Gay Men’s Unrealistic Optimism about Becoming Infected with HIV. Int. J. STD AIDS 2003, 14, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoch, Y.; Rolison, J.; Freund, A.M. Reaping the Benefits and Avoiding the Risks: Unrealistic Optimism in the Health Domain. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.; Bortolotti, L.; Kuzmanovic, B. What Is Unrealistic Optimism? Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 50, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Pogge, G.; Howell, J.L. Assessing the Consequences of Unrealistic Optimism: Challenges and Recommendations. Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 50, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.P. Unrealistic Optimism: Still a Neglected Trait. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsa, H.G.; Self, J.T.; Njite, D.; King, T. Why Restaurants Fail. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Why It Won’t Happen to Me: Perceptions of Risk Factors and Susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1984, 3, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, Y.C.; Zaki, J. Unrealistic Optimism in Advice Taking: A Computational Account. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T.; Korn, C.W.; Dolan, R.J. How Unrealistic Optimism Is Maintained in the Face of Reality. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1475–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Reducing Unrealistic Optimism about Illness Susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1983, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinski, D.; Kulesza, W.; Muniak, P.; Dolinska, B.; Węgrzyn, R.; Izydorczak, K. Media Intervention Program for Reducing Unrealistic Optimism Bias: The Link between Unrealistic Optimism, Well-Being, and Health. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yan, H.; Casey, T.; Wu, C.-H. Creating a Safe Haven during the Crisis: How Organizations Can Achieve Deep Compliance with COVID-19 Safety Measures in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Leung, X.Y. Mindset Matters in Purchasing Online Food Deliveries during the Pandemic: The Application of Construal Level and Regulatory Focus Theories. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, Transformations and Tourism: Be Careful What You Wish for. Tour. Geogr. Int. J. Tour. Place Space Environ. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.K.; Tang, L. (Rebecca) Effects of Epidemic Disease Outbreaks on Financial Performance of Restaurants: Event Study Method Approach. J. Int. Hosp. Leisure Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druică, E.; Musso, F.; Ianole-Călin, R. Optimism Bias during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy. Games 2020, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | (Q1) Risk of Being Infected | (Q4) Vaccinated for Coronavirus | (Q7) Chances of Losing a Job | (Q10) Chances That the Company Will Go Bankrupt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Q1) Risk of being infected | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.31 *** | 0.11 | 0.19 * |

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | 0.190 | 0.021 | |

| (Q4) Vaccinated for coronavirus | Pearson’s r | --- | −0.01 | 0.12 | |

| p-value | --- | 0.959 | 0.139 | ||

| (Q7) Chances of losing a job | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.580 *** | ||

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | |||

| (Q10) Chances that the company will go bankrupt | Pearson’s r | --- | |||

| p-value | --- |

| Variables | (Q2) Risk of being Infected | (Q5) Vaccinated for Coronavirus | (Q8) Chances of Losing a Job | (Q11) Chances that the Company Will go Bankrupt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Q2) Risk of being infected | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.32 *** | 0.2 * | 0.23 ** |

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.004 | |

| (Q5) Vaccinated for coronavirus | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.07 | 0.14 | |

| p-value | --- | 0.423 | 0.087 | ||

| (Q8) Chances of losing a job | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.4 *** | ||

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | |||

| (Q11) Chances that the company will go bankrupt | Pearson’s r | --- | |||

| p-value | --- |

| Variables | (Q3) Risk of Being Infected | (Q6) Vaccinated for Coronavirus | (Q9) Chances of Losing a Job | (Q12) Chances that the Company Will go Bankrupt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Q3) Risk of being infected | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.18 * | 0.26 ** | 0.04 |

| p-value | --- | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.654 | |

| (Q6) Vaccinated for coronavirus | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.43 *** | 0.24 ** | |

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||

| (Q9) Chances of losing a job | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.53 *** | ||

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | |||

| (Q12) Chances that the company will go bankrupt | Pearson’s r | --- | |||

| p-value | --- |

| Variables | Risk of Being Infected (Magnitude) | Vaccinated for Coronavirus (Magnitude) | Chances of Losing a Job (Magnitude) | Chances That the Company Will Go Bankrupt (Magnitude) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of being infected (magnitude) | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.08 | −0.12 | −0.01 |

| p-value | --- | 0.340 | 0.158 | 0.933 | |

| Vaccinated for coronavirus (magnitude) | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.09 | 0.15 | |

| p-value | --- | 0.283 | 0.069 | ||

| Chances of losing a job (magnitude) | Pearson’s r | --- | 0.33 *** | ||

| p-value | --- | <0.001 | |||

| Chances that the company will go bankrupt (magnitude) | Pearson’s r | --- | |||

| p-value | --- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dolinski, D.; Kulesza, W.; Muniak, P.; Dolinska, B.; Derakhshan, A.; Grzyb, T. Research on Unrealistic Optimism among HoReCa Workers as a Possible Future Hotspot of Infections. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212562

Dolinski D, Kulesza W, Muniak P, Dolinska B, Derakhshan A, Grzyb T. Research on Unrealistic Optimism among HoReCa Workers as a Possible Future Hotspot of Infections. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212562

Chicago/Turabian StyleDolinski, Dariusz, Wojciech Kulesza, Paweł Muniak, Barbara Dolinska, Ali Derakhshan, and Tomasz Grzyb. 2021. "Research on Unrealistic Optimism among HoReCa Workers as a Possible Future Hotspot of Infections" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212562