Random Walk of Socially Responsible Investment in Emerging Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methodology

- H < 0.5—A mean-reverting series. The mean-reversion process gets stronger when the value is close to 0. In actual practice, a low value is followed by a high value and vice versa.

- H = 0.5—A geometric random walk.

- H > 0.5—A trending (persistent) series. The trend gets stronger when the value is close to 1. It means, in reality, that a high value is followed by a higher one.

- R(n): the range of the first n accumulative deviations from the mean.

- S(n): the series of the first n standard deviations.

- E[x]: the expected value.

- n: the period of the observation (number of data points in a time series).

- C: constant.

- H0: short-range memory.

- H1: long-range memory.

4. Empirical Findings

| Index | Mean | SD | Skewness | Ex. Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCI Brazil ESG | 0.00020112 | 0.022487 | −0.71589 | 8.8025 |

| MSCI China Carbon SRI leaders | −0.0029664 | 0.052699 | −15.947 | 300.94 |

| S&P/ESG Egypt | −0.00040675 | 0.016173 | −1.9007 | 13.867 |

| SRI Kehati (Indonesia) | 0.00026876 | 0.013912 | 0.81852 | 16.733 |

| MSCI India ESG | 0.00068048 | 0.010658 | −0.33566 | 1.7098 |

| MSCI Malaysia ESG Leaders | 9.5293 × 10−5 | 0.0083611 | −0.21852 | 8.2689 |

| MSCI Philippines ESG | 4.1337 × 10−5 | 0.014115 | −0.52522 | 9.6239 |

| MSCI Thailand ESG | 0.00010335 | 0.010569 | −1.1540 | 21.741 |

| MSCI Taiwan ESG Leaders | 0.00080415 | 0.012164 | −0.068071 | 4.3237 |

| MSCI South Africa ESG Leaders | 0.00030479 | 0.018786 | −0.48501 | 3.3680 |

| MSCI ACWI SRI | 0.00051574 | 0.0098140 | −1.0297 | 21.429 |

| MSCI EM ESG Leaders | 0.00027887 | 0.010798 | −0.55117 | 5.4930 |

| DJSEM | 0.00014293 | 0.0097747 | −0.65990 | 7.2092 |

| MCSI Latin America ESG Leaders | 0.00010546 | 0.017985 | −0.90443 | 10.837 |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koellner, T.; Suh, S.; Weber, O.; Moser, C.; Scholz, R.W. Environmental impacts of conventional and sustainable investment funds compared using input-output life-cycle assessment. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, H.H.; Nguyen, D.K. Policy uncertainty and performance characteristics of sustainable investments across regions around the global financial crisis. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2014, 24, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US SIF US SIF foundation releases 2016 biennial report on US sustainable, responsible and impact investing trends. Forum Sustain. Responsible Invest. 2016. Available online: https://gsgii.org/reports/us-sustainable-responsible-and-impact-investing-trends-2016/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Chegut, A.; Schenk, H.; Scholtens, B. Assessing SRI fund performance research: Best practices in empirical analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, B.R.; Schuhmacher, F. Do socially (ir)responsible investments pay? New evidence from international ESG data. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 59, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, E.; Moneva, J.M.; Salvador, M. Does socially responsible investment equity indexes in emerging markets pay off? Evidence from Brazil. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2012, 13, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, B.R. Do Socially Responsible Investment Policies Add or Destroy European Stock Portfolio Value? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, W.R.; Weber, O. The market efficiency of socially responsible investment in Korea. J. Glob. Responsib. 2018, 9, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.P. Market Efficiency in ESG Indexes: Trading Opportunities. J. Impact ESG Invest. 2021, 1, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynhardt, H.; Makarenko, I.; Plastun, A. Market efficiency of traditional stock market indices and social responsible indices: The role of sustainability reporting. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2017, 14, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumeboonsuke, V.; Dryver, A.L. The importance of using a test of weak-form market efficiency that does not require investigating the data first. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2014, 33, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.W.; MacKinlay, A.C. Stock Market Prices Do Not Follow Random Walks: Evidence from a Simple Specification Test. Rev. Financ. Stud. 1988, 1, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.A.S.; Cantú, L.S.; Veleros, Z.H. Dynamic Hurst Exponent in Time Series. March 2019. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.07809 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Bhasin, H. What is Market Efficiency? Importance of Market Efficiency. 27 May 2019. Available online: https://www.marketing91.com/what-is-market-efficiency/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Benson, A. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Investing and How to Get Started. 22 August 2022. Available online: https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/investing/esg-investing (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Chatzitheodorou, K.; Skouloudis, A.; Evangelinos, K.; Nikolaou, I. Exploring socially responsible investment perspectives: A literature mapping and an investor classification. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Papathanasiou, S.; Dar, V.; Kenourgios, D. Deconstruction of the Green Bubble during COVID-19 International Evidence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, Z.; Kenourgios, D.; Papathanasiou, S. The static and dynamic connectedness of environmental, social, and governance investments: International evidence. Econ. Model. 2020, 93, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkiel, B.G.; Fama, E.F. Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work*. J. Financ. 1970, 25, 383–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Random Walks in Stock Market Prices. Financ. Anal. J. 1995, 51, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.R. Efficient market hypothesis in European stock markets. Eur. J. Financ. 2009, 16, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Noda, A.; Wada, T. The evolution of stock market efficiency in the US: A non-Bayesian time-varying model approach. Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K. Are the Australian and New Zealand stock prices nonlinear with a unit root? Appl. Econ. 2005, 37, 2161–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Smyth, R. Is South Korea’s stock market efficient? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2004, 11, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Smyth, R. Are OECD stock prices characterized by a random walk? Evidence from sequential trend break and panel data models. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2005, 15, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Seyyed, F.J.; Alsakran, S.A. Testing the random walk behavior and efficiency of the gulf stock markets. Financ. Rev. 2002, 37, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faryan, M.A.S.; Dockery, E. Testing for efficiency in the Saudi stock market: Does corporate governance change matter? Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2021, 57, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley, J. Are GCC stock markets predictable? Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2011, 12, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngene, G.; Tah, K.A.; Darrat, A.F. The random-walk hypothesis revisited: New evidence on multiple structural breaks in emerging markets. Macroecon. Financ. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2017, 10, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, A.C.; Higgs, H. Weak-Form Market Efficiency in Asian Emerging and Developed Equity Markets: Comparative Tests of Random Walk Behaviour. Account. Res. J. 2006, 19, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Caporale, G.M.; Gil-Alana, L.A.; You, K. Global and Regional Financial Integration in Emerging Asia: Evidence from Stock Markets. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 36, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dios-Alija, T.; del Río Caballero, M.; Gil-Alana, L.A.; Martin-Valmayor, M. Stock market indices and sustainability: A comparison between them. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managi, S.; Okimoto, T.; Matsuda, A. Do socially responsible investment indexes outperform conventional indexes? Appl. Financ. Econ. 2012, 22, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Rong Ang, W. The Performance, Volatility, Persistence and Downside Risk Characteristics of Sustainable Investments in Emerging Market. ACRN Oxf. J. Financ. Risk Perspect. 2016, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, V.; Kaur, A. Does Socially Responsible Investing Pay in Developing Countries? A Comparative Study Across Select Developed and Developing Markets. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2021, 11, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saci, F.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Hasan, M. Performance of Socially Responsible Investment Funds in China: A Comparison with Traditional Funds. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cunha, F.A.F.S.C.; Samanez, C.P. Performance Analysis of Sustainable Investments in the Brazilian Stock Market: A Study about the Corporate Sustainability Index (ISE). J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakici, N.; Zaremba, A. Liquidity and the cross-section of international stock returns. J. Bank. Financ. 2021, 127, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Vieito, J.P. Stock exchange mergers and weak form of market efficiency: The case of Euronext Lisbon. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2012, 22, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakić, N.; Jovancai, A.; Kapor, P. The efficiency of the stock market in Serbia. J. Policy Model. 2016, 38, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.W. Long-Term Memory in Stock Market Prices. Econometrica 1991, 59, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, S.; Rizvi, S.A.R.; Ghani, G.M.; Duasa, J. Investigating stock market efficiency: A look at OIC member countries. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2016, 36, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekhal, M.; El Oubani, A. Does the Adaptive Market Hypothesis explain the evolution of emerging markets efficiency? Evidence from the Moroccan financial market. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N.; Thaler, R. Chapter 18 A Survey of Behavioral Financ. Handb. Econ. Financ. 2003, IB, 1053–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authers, J. Why Are Markets Inefficient and What Can Be Done About It? Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/d9f70604-a611-11e3-8a2a-00144feab7de (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Ghosh, S.; Revilla, E. Enhancing the efficiency of securities markets in East Asia. Macroecon. Financ. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2008, 1, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

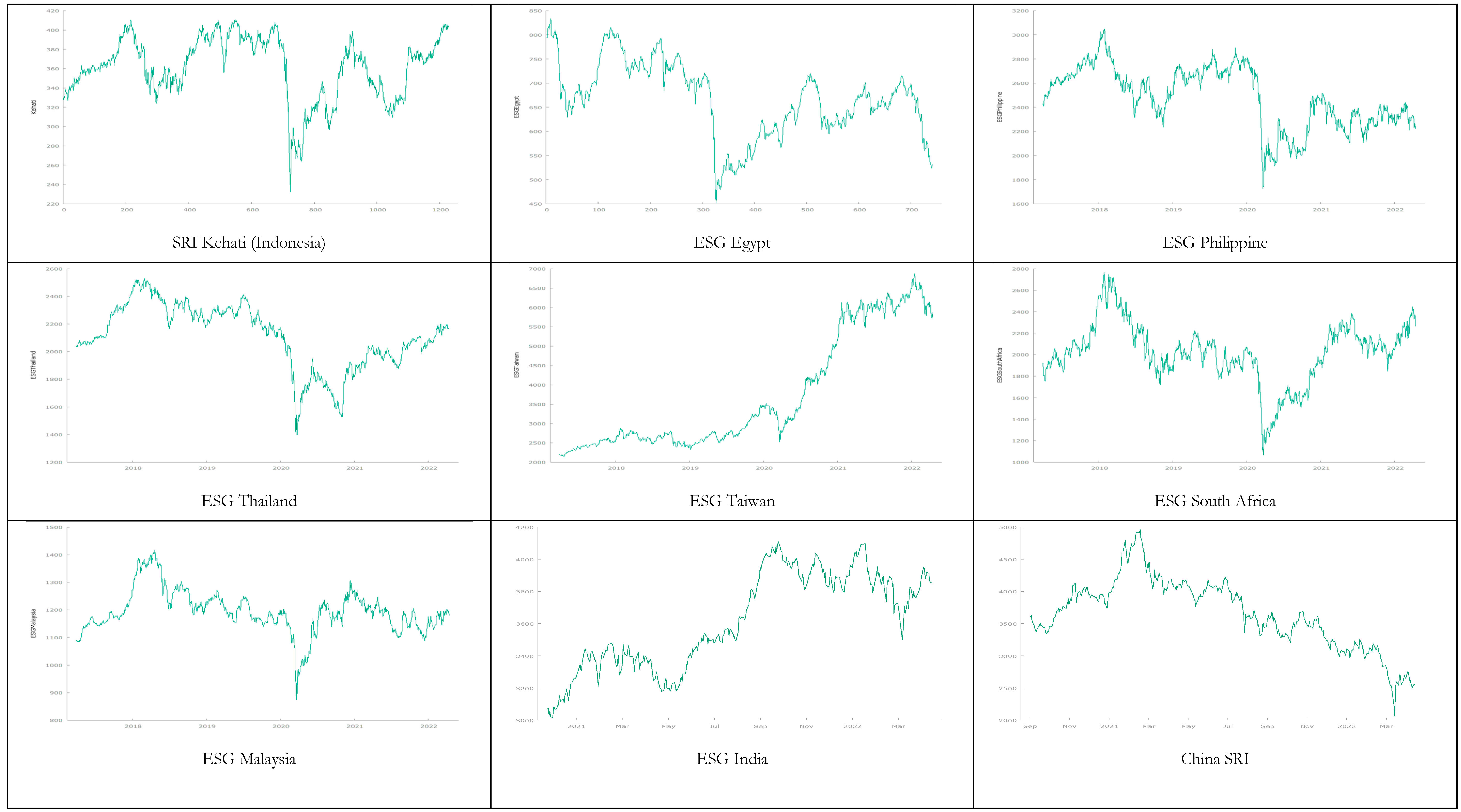

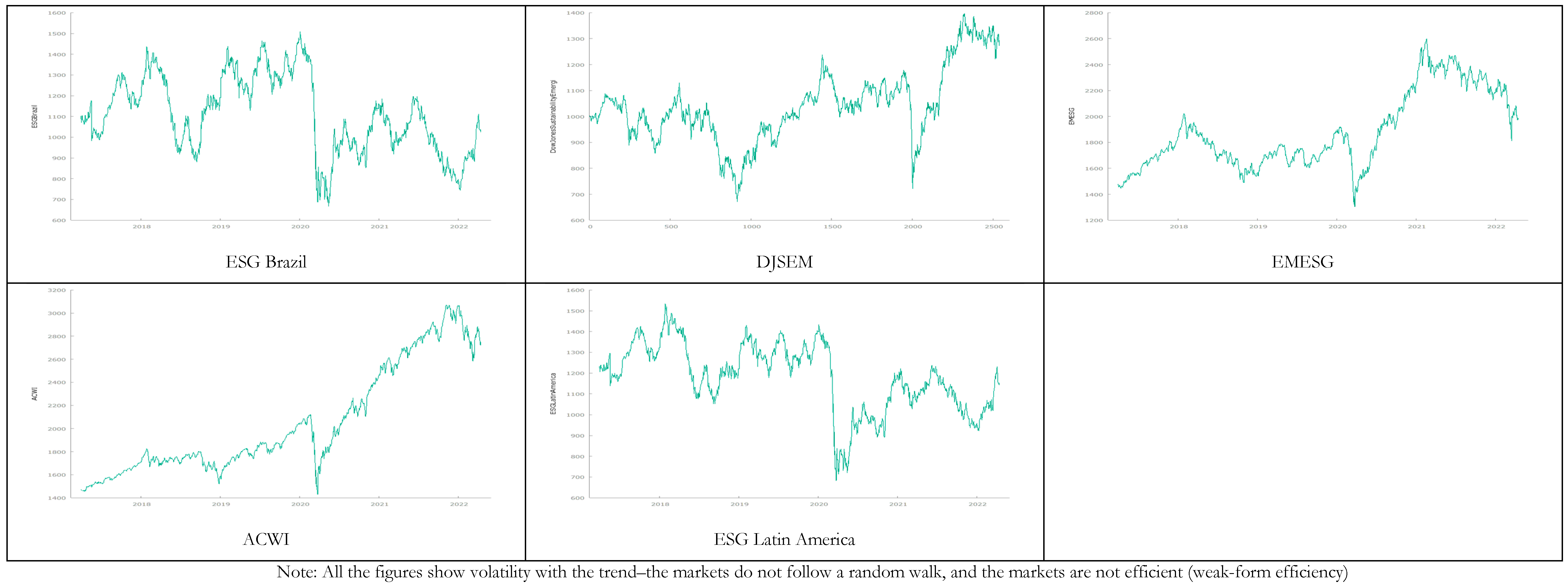

| Index | Period |

|---|---|

| MSCI Brazil ESG | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI China Carbon SRI leaders | 1 September 2020–18 April 2022 |

| S&P/ESG Egypt | 26 July 2018–21 April 2022 |

| SRI Kehati (Indonesia SRI) | 29 March 2017–18 April 2022 |

| MSCI India ESG | 29 March 2020–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI Malaysia ESG Leaders | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI Philippines ESG | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI Thailand ESG | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI Taiwan ESG Leaders | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI South Africa ESG Leaders | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI ACWI SRI | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| MSCI EM ESG Leaders | 29 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| DJSEM | 30 September 2012–12 April 2022 |

| MCSI Latin America ESG Leaders | 30 March 2017–15 April 2022 |

| Index | Statistic (τ) | Asymptotic p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSCI Brazil ESG | −12.7833 | 2.999 × 10−28 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI China Carbon SRI leaders | −7.04928 | 6.962 × 10−10 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| S&P/ESG Egypt | −8.67311 | 4.834 × 10−15 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| SRI Kehati (Indonesia) | −8.1309 | 2.059 × 10−13 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI India ESG | −13.1661 | 1.767 × 10−29 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI Malaysia ESG Leaders | −13.9945 | 4.267 × 10−32 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI Philippines ESG | −20.2898 | 6.749 × 10−48 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI Thailand ESG | −13.6947 | 3.71 × 10−31 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI Taiwan ESG Leaders | −24.3104 | 4.307 × 10−52 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI South Africa ESG Leaders | −13.9669 | 5.204 × 10−32 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI ACWI SRI | −9.37127 | 3.308 × 10−17 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MSCI EM ESG Leaders | −14.7341 | 2.292 × 10−34 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| DJSEM | −18.2548 | 8.009 × 10−44 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| MCSI Latin America ESG Leaders | −12.7981 | 2.686 × 10−28 *** | no unit root problem (no random walk) |

| Index | q-2 (Two Tailed p-Value) | q-4 (Two Tailed p-Value) | q-8 (Two Tailed p-Value) | q-16 (Two Tailed p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCI Brazil ESG | 6.5599 × 10−9 *** | 6.3137 × 10−6 *** | 0.00027697 *** | 0.0028438 *** |

| MSCI China Carbon SRI leaders | 1.4627 × 10−5 *** | 1.2368 × 10−6 *** | 0.0001713 *** | 0.002054 *** |

| S&P/ESG Egypt | 4.4487 × 10−8 *** | 1.352 × 10−7 *** | 2.0302 × 10−5 *** | 0.00083756 *** |

| SRI Kehati (Indonesia) | 2.0167 × 10−12 *** | 6.5918 × 10−10 *** | 7.4641 × 10−7 *** | 0.00011646 *** |

| MSCI India ESG | 2.8202 × 10−10 *** | 1.0233 × 10−9 *** | 1.6372 × 10−6 *** | 0.00051029 *** |

| MSCI Malaysia ESG Leaders | 1.1111 × 10−8 *** | 1.2355 × 10−7 *** | 3.0788 × 10−6 *** | 6.6265 × 10−5 *** |

| MSCI Philippines ESG | 6.0149 × 10−18 *** | 2.7688 × 10−13 *** | 1.884 × 10−8 *** | 2.3462 × 10−5 *** |

| MSCI Thailand ESG | 5.6383 × 10−8 *** | 1.2715 × 10−5 *** | 0.00032194 *** | 0.007479 *** |

| MSCI Taiwan ESG Leaders | 7.4268 × 10−14 *** | 1.5896 × 10−10 *** | 9.8773 × 10−9 *** | 9.0766 × 10−7 *** |

| MSCI South Africa ESG Leaders | 6.3824 × 10−26 *** | 2.7957 × 10−18 *** | 7.874 × 10−11 *** | 9.1682 × 10−7 *** |

| MSCI ACWI SRI | 6.8367 × 10−6 *** | 0.0013198 *** | 0.011651 *** | 0.042038 *** |

| MSCI EM ESG Leaders | 1.5825 × 10−12 *** | 7.4753 × 10−10 *** | 9.4272 × 10−7 *** | 0.00014272 *** |

| DJSEM | 2.0747 × 10−14 *** | 1.7397 × 10−11 *** | 8.9392 × 10−9 *** | 7.0157 × 10−6 *** |

| MCSI Latin America ESG Leaders | 1.2472 × 10−7 *** | 3.2503 × 10−5 *** | 0.0008831 *** | 0.0066745 *** |

| Index | Lo’s Modified R/S Statistic | Critical Values for 1 Percent | Result–H0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSCI Brazil ESG | 40.404 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI China Carbon SRI leaders | 19.243 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| S&P/ESG Egypt | 73.788 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| SRI Kehati (Indonesia) | 97.327 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI India ESG | 131.29 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI Malaysia ESG Leaders | 167.99 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI Philippines ESG | 83.062 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI Thailand ESG | 137.69 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI Taiwan ESG Leaders | 131.16 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI South Africa ESG Leaders | 80.528 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI ACWI SRI | 143.06 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MSCI EM ESG Leaders | 123.62 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| DJSEM | 98.337 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

| MCSI Latin America ESG Leaders | 63.037 | 0.721 and 2.098 *** | rejected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Danila, N. Random Walk of Socially Responsible Investment in Emerging Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911846

Danila N. Random Walk of Socially Responsible Investment in Emerging Market. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911846

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanila, Nevi. 2022. "Random Walk of Socially Responsible Investment in Emerging Market" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911846

APA StyleDanila, N. (2022). Random Walk of Socially Responsible Investment in Emerging Market. Sustainability, 14(19), 11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911846