1. Introduction

The United Nations (UN) champions the inclusion of youth participants in global governance processes and has taken significant steps to demonstrate their commitment to this agenda. These include a dedicated Envoy on Youth, global youth conferences on a variety of topics, and youth participation in a range of governance processes. Speaking in 2017, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres argued that to address the world’s most pressing challenges:

“The best hope […] is with the new generations, we need to make sure that we are able to strongly invest in those new generations”

Tackling climate change is one such global challenge, where calls for youth engagement are particularly strong. As former UN Envoy on Youth, Ahmad Alhendawi, emphasises:

“We must empower youth as leaders of climate action today, because by the time they become the leaders of tomorrow it will be too late for their generation to prevent dangerous climate change”

These quotes go some way to acknowledging that younger generations require investment and empowerment from incumbent power holders if they are to play a key role in tackling climate change, which recent studies of youth participation in the UNFCCC support [

3,

4]. Due to the temporal nature of the climate crisis, young people are arguably the living generation with the most at stake as, if decision-makers do not take sufficient action to bend the emissions curve now and steer the world away from its current course, it will be the younger generation who are left to pick up the pieces [

5,

6]. To ensure that low-carbon transitions are intergenerationally as well as intragenerationally just, youth participants must be able to participate as equals in collective decision-making processes, working alongside older generations to identify potential conflicts between generational interests, values, and needs over time.

In 2009, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) recognised Youth NGOs (YOUNGO) as one of nine civil society constituencies, alongside Business and Industry (BINGO), Environmental NGOs (ENGO), Trade Union NGOs (TUNGO), Research and Independent NGOs (RINGO), Local Government and Municipal Authorities (LGMA), Indigenous Peoples’ Organisations (IPO), Women and Gender (WGC), and Farmers. These groups are permitted to observe the UNFCCC negotiations, but participation is reserved for government representatives.

Constituency status enables these stakeholder groups to receive logistical information from the UNFCCC Secretariat about upcoming meetings; to nominate representatives to attend meetings where access is primarily limited to governments; to deliver short interventions to government representatives in Plenary sessions; to host and participate in side events; to host exhibits; to attend bilateral meetings with senior officials; and to hold small protests or “actions” in designated areas within UNFCCC conferences [

7]. In addition, young people lobby government representatives, engage with the media, and are active participants in social movements such as Fridays for Future, engaging in protests and events outside of the formal UNFCCC negotiations.

YOUNGO is the oldest and largest youth constituency to any UN body [

8]. In 2013, the UNFCCC Secretariat appointed a dedicated staff member to oversee and support YOUNGO and the negotiations on Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE), which includes public participation. One might expect youth participation to be flourishing given this high-level institutional support. However, research in this area is distinctly lacking. This is in part because much of the academic literature on the UNFCCC stems from International Relations, a discipline primarily concerned with governments or “State Actors” (SAs). Although environmental governance scholars have more recently turned their attention to “Non-State Actors” (NSAs), there has been a tendency to homogenise their experiences or focus on more powerful, better-resourced NSAs, such as businesses and environmental NGOs. Notable exceptions include Marion Suiseeya [

9] and Hemmati and Rohr ’s [

10] studies of indigenous peoples and women.

A small number of studies have turned their attention to YOUNGO, showing that youth participants attending UNFCCC conferences lack resources, recognition, and political capital and struggle to effect change, resulting in a pervasive sense of powerlessness and frustration [

3,

4,

6,

11]. Nevertheless, youth participation in the UNFCCC continues to grow, with the latest available participation data from the UNFCCC Secretariat showing YOUNGO to be the fourth largest nongovernmental constituency (making up 5.4% of attendees), though still much smaller than Environmental NGOs at 37.6%, Researchers at 27.1%, and Businesses at 15.8% [

12]. As the youth climate movement continues to capture attention around the world through strikes and widespread press coverage, policymakers would be shrewd to ensure that the participatory experiences of this vocal constituency are positive, given the platform young people have to shape the public opinion of the UNFCCC negotiations. This includes asking questions such as: what is driving young people to engage in the UNFCCC process, what are their experiences, and how can their participation be ameliorated?

To address these questions, we turn to the Youth Studies literature for guidance. Where previous studies of YOUNGO have drawn upon political science, sociological, and philosophical literature to situate youth participation within the broader context of environmental governance, asking what their experiences can tell us about climate change governance [

3,

4,

6,

7,

11], this paper asks instead what their experiences can tell us about how young people experience UNFCCC conferences, the physical and psychological barriers they face, and how their participation could be improved.

1.1. Introducing the “7P” Model

To facilitate this broad exploration of youth participation, we draw upon Cahill and Dadvand’s “7P” model [

13], which investigates seven intersecting “Ps” (Purpose, Positioning, Perspectives, Power Relations, Protection, Place, and Process) with a series of prompting questions to direct a critical evaluation of youth participation. We test the “7P” model using ethnographic data on youth participation in the UNFCCC, focusing on a well-established case-study organisation within YOUNGO: the UK Youth Climate Coalition (UKYCC). This interdisciplinary exercise offers empirical insights into each P as well as shedding light on how interactions between the Ps shape youth participation in this global context. We propose that a new P—Psychological Factors—is added to the model, replacing Process, which we suggest is better addressed in research methodology than in the analytical framework. In addition, we propose six further prompts to guide future research, consolidating all prompts into a single table (

Table 1) to enhance the model’s usability.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 1.2 situates our study by reviewing relevant literature on youth political participation and youth participation in climate governance and establishes our research questions.

Section 2 explains our materials and methods used, and

Section 3 presents our results, structured around the seven Ps.

Section 4 reflects on our application of the model and the insights it offers for ameliorating youth participation in global climate governance, and

Section 5 draws conclusions.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Youth Political Participation

We follow Andersson’s definition of youth political participation as “

democratic participation and influence on processes and situations in the battle for how society is organised” [

14] (p. 1346). However, in line with the framing of this special issue, we propose that this does not necessarily have to be a battle in which there are winners and losers, but rather could be a socially interactive process in which conflicts are overcome, competing interests are reconciled, and inequalities are acknowledged and acted upon. For this to happen, it is necessary to consider the direct and indirect ways in which power is exercised within decision-making processes, as has been explored in the context of youth participation in the UNFCCC [

3]. It is also necessary to consider the broader power imbalances in society which shape young people’s social interactions.

The youth studies literature emphasises that the way in which young people are perceived in society has a profound impact upon their experience. Often seen in terms of their potential to become economic contributors or social delinquents of the future, youth political participation is typically viewed through the lens of developmental psychology: a linear perspective which sees youth as citizens in the making, portraying them as deficient, denying them recognition, and overlooking the contributions they can make in the present [

14,

15]. Youth participation has been shown to benefit both individuals and the projects they engage in [

16,

17]. As Skelton [

18] (p. 147) asserts:

“[There is] significant evidence that young people are politically active, show competence in understanding political processes and take political action […] young people are political actors now; they are not political subjects ‘in-waiting’.”

However, the facilitation of participatory opportunities is necessary to ensure that young people’s perspectives are given due weight in political processes [

19].

It is important to recognise that participatory experiences are shaped by young people’s everyday lives, life trajectories, and the societies in which they are embedded [

20]. Thus, a tailored approach is needed to understand the nuances and complexities of youth political participation, rather than assuming direct comparability with other participants. Specifically, an approach is needed which recognises youth as reflexive social actors who shape and are shaped by their sociocultural experiences [

21]. Studies should take account of social and cultural contexts, such as the interactions between politics, culture, and transitions to adulthood [

22], to explore how youth participants experience and respond to power dynamics in the processes in which they operate and how they strategise and make decisions amongst themselves [

23].

1.2.2. Youth Participation Models

The following section briefly reviews prominent youth participation models and their critiques, leading to our rationale for selecting the 7P model [

13] as the most appropriate framework for addressing social and cultural context and power.

Several well-known youth participation models have been critiqued for being hierarchical and normatively suggesting that greater levels of youth control over a project are always superior, regardless of context [

24,

25,

26]. In addition, they focus on structures of participation, overlooking the broader context shaping young people’s interactions and experiences (e.g., [

24,

27]). These models appraise youth participation according to the extent to which adults distribute decision-making. This overlooks the benefits that youth (and others) gain through political engagement, even when unable to directly shape decision-making outcomes [

14]. Rather than perceiving power as a zero-sum commodity, more recent work acknowledges that although adults may “set the stage”, youth participants develop unique strategies and goals with their peers [

28].

Another critique of earlier youth participation models is their lack of acknowledgement of mutuality, which frames youth participants as dependent upon adults for their development, failing to acknowledge the ways in which youth can contribute to a process [

24,

25,

26,

27].

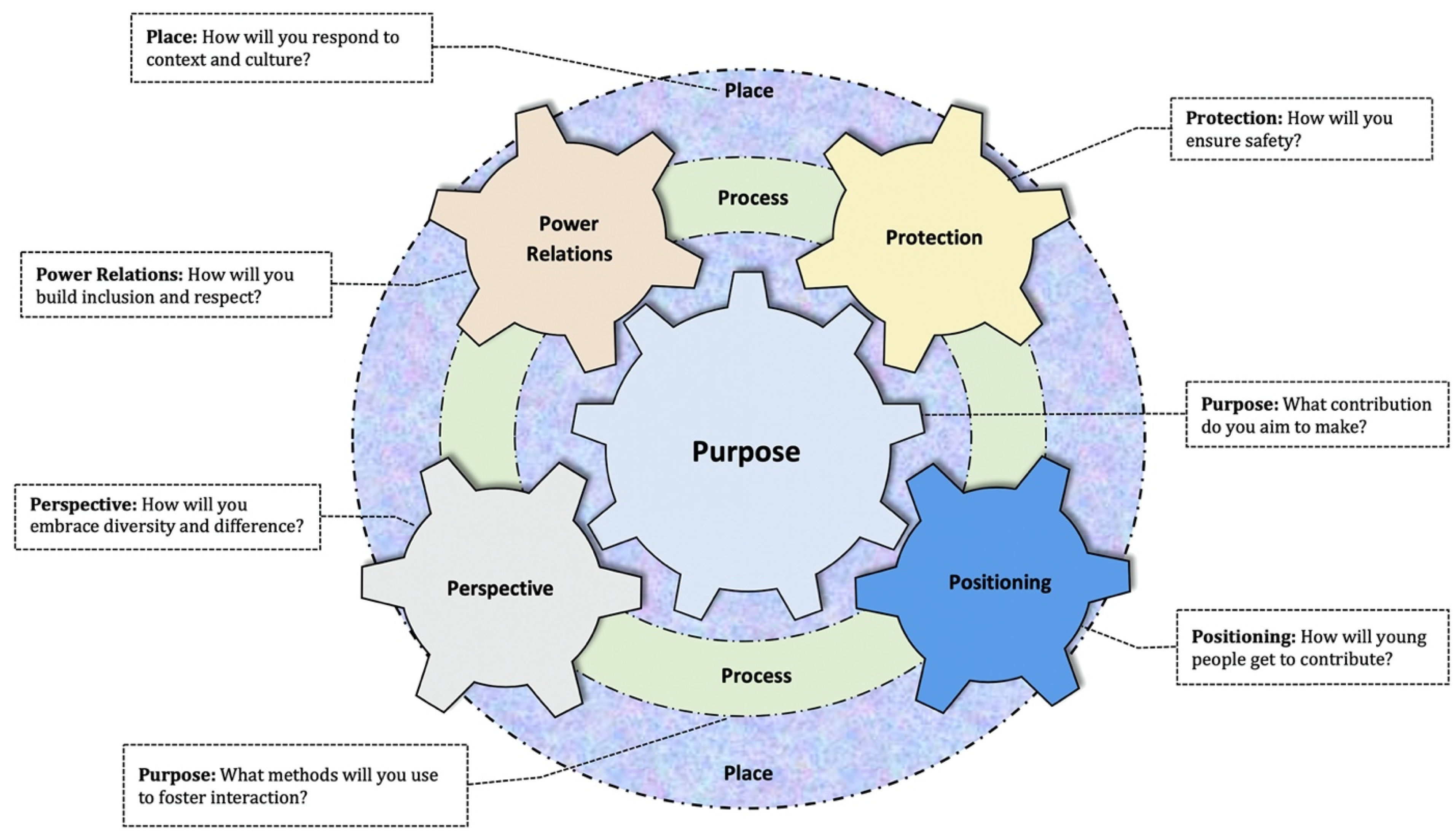

Cahill and Dadvand [

13] draw upon critical theory, feminist literature, and youth studies to present the 7P model. Their machinelike depiction of seven dynamic and interactive elements—

Purpose,

Positioning,

Perspectives,

Power Relations,

Protection,

Place and

Process (shown in

Figure 1)—can be used to “think through” youth participation from a variety of angles. In addition, they discuss each “P” in turn, propose prompting questions, and provide illustrative examples, creating a model which moves youth participation theory forward in its consideration of structure, agency, and power. We thus deem the 7P model to be the most able to account for sociocultural context and power dynamics in our study.

1.2.3. Youth Participation in Climate Change Governance

As government has given way to governance, youth participation has moved from engagement in electoral politics and membership of political parties or institutions to “cause-oriented civic action”, with climate change being of particular interest [

29]. Youth participation has been proposed as a solution to wicked problems such as climate change [

30] and, despite their vulnerability to climate impacts, young people can be valuable contributors to environmental action and disaster risk reduction [

15,

16,

17]. However, their contributions and needs are often overlooked due to “adultism” [

31], which socially positions youth as unequal to adults, entitling adults to make decisions for youth without their consent. This excludes young people’s unique perspectives on and solutions to climate change [

15,

19].

There are few formal opportunities for youth participation in climate governance, particularly at the global level, with one of the more established and arguably more prestigious being UNFCCC participation. However, only a handful of studies on youth participation in this context have been published to date [

3,

4,

6,

7,

11,

32], and although these papers make various contributions, e.g., exploring youth agency and the articulation of justice claims, they are primarily situated within environmental governance debates and focus on what young people’s participatory experiences can tell us about the broader climate governance regime, rather than drawing upon the wealth of expertise from Youth Studies to develop an understanding of why young people engage in these spaces, how the multiple barriers they face intersect, and what can be done to ameliorate their participation. An exception to this is a recent study of indigenous youth participation in the UNFCCC, which found that indigenous youth participants from Canada attending COP24 increased their social capital through “webs of support”, enabling them to share valuable local knowledge which was “not easily Googleable” [

11] (p. 6299).

Further insights into youth climate activism have been offered by recent studies on national and local youth climate strikes, e.g., in Poland [

33], Switzerland [

34], Austria, and Portugal [

35], which have found that climate activism can increase young people’s sense of agency, providing an outlet for their worry and anger about climate change, though it can also lead to exhaustion and burnout. Whether these experiences are the same in global governance processes has yet to be explored.

A couple of recent papers have explored youth participation in other UN spaces, finding that power dynamics, participatory structures, and cultures maintain hierarchies between generations [

35,

36,

37]. This emphasises the need for greater interdisciplinary work to bring together insights from Youth Studies with the wider governance literature, and further supports the suitability of the 7P model for exploring youth participation in global governance, given its consideration of context and power.

1.2.4. Research Questions

We apply the 7P framework to the experiences of UKYCC members’ participation in the UNFCCC, encouraging environmental scholars whose interest in youth participation has been recently piqued by the rise in young climate activist movements to delve into the wealth of guidance available from Youth Studies scholars. In doing so, we share a wide range of empirical evidence on the participatory experiences of youth and develop the 7P model, thus contributing to the academic toolbox to assist future scholars and practitioners in the design and evaluation of youth participation. In doing so, we address two research questions:

To what extent is the 7P model able to facilitate a broader appraisal of youth participation in the UNFCCC by taking into account a wide range of factors shaping their lived experiences of participation? Are there ways in which it could be amended to better achieve this objective?

What insights does the application of this model provide to improve our understanding of youth participation in the UNFCCC?

2. Materials and Methods

This paper draws upon a broader ethnographic research project with UKYCC: a UK-based, youth-led organisation that has sent delegations to the UNFCCC’s Conference of the Parties (COPs) since 2008, making them one of the more established organisations within YOUNGO. UKYCC consists of volunteers aged 17 to 29 years old, within YOUNGO’s age range of 16–35 years. They engage in climate action at local, national, and global levels, though the UNFCCC is the only formal participatory opportunity that is consistently available to them, year after year. Mirroring YOUNGO’s demographic, members of UKYCC are predominantly middle-class university students and graduates. At the time of data collection, 90% of members were female or gender nonbinary, and 25% were activists of colour.

Data were collected between 2015 and 2018, including 32 semi-structured interviews and over 900 h of participant observation at six UNFCCC conferences: three COPs (COP21, 22, and 23) and three “intersessional” negotiations, as well as team meetings in the UK.

The time-intensive, in-depth methodology of ethnography enables rich insights into the lived experiences of youth participants [

38,

39], shedding light on how they experience the power-laden arena of the UNFCCC and the strategies they use to navigate it [

9]. The deep insights into participatory experiences which ethnography facilitates are well suited to the application of the 7P model, which was originally designed for another deep qualitative method: participatory action research (PAR). Like PAR, the longitudinal ethnographic approach taken was reflexive and responsive, with repeat engagement with the same participants over three years. Studying a group based in the same country as the research team was necessary to facilitate deep, prolonged engagement over time. Our lead researcher also conducted document analysis of key YOUNGO and UNFCCC texts and engaged with YOUNGO’s listservs, Google, and Facebook groups to keep up to date with discussions within the constituency. Unlike PAR, ethnographic participant observation does not depend upon the research participants themselves taking action to further the research. This was deemed ethically preferable in this instance, so as not to place any additional demands upon young UNFCCC participants who, as dedicated but under-resourced volunteers), already struggle with a lack of capacity to engage with the negotiations.

By selecting a methodology that enabled our lead researcher to experience UNFCCC spaces first-hand alongside our research participants, “

walking a mile in their shoes” [

39] (p. 1), observing closely and taking many fieldnotes, we sought to incorporate participant experience into our research design without it being onerous for participants, given their limited time and resources. Ethnography includes ongoing reflexivity on power dynamics within the research process, and focuses on developing trust, understanding, respect and reciprocity between researcher and participants. As a former member of YOUNGO who has engaged with the constituency since 2012, attending twelve UNFCCC conferences to date, our lead researcher was well-placed to undertake this complex and sensitive task. She usually arrived in conference locations a couple of days prior to their official commencement, attending preparatory meetings with youth participants. During conferences, she spent the majority of her time with youth participants, attending their meetings and accompanying them to side events and negotiations, always introducing herself as a researcher of youth participation.

Interviews were conducted face to face or over Skype, audio-recorded and transcribed, usually taking place shortly after conferences had ended, when participants had more time and were reflecting on their participatory experience alongside their re-immersion in their daily routines. Data were coded using Nvivo, using the critical realist method of “zigzagging” between literature and data to develop themes which speak to existing debates or frameworks without the limitations of a fixed hypothesis [

40].

Inductive codes such as “Motivations”, “Perceptions of Youth Role”, and “Barriers” were drawn upon for each of the 7Ps. For further details on the subcodes used and the frequency with which they occurred, please see the coding table in

Appendix A. For Purpose, Positioning, and Psychological factors, all subcodes under the listed parent code were included in the analysis. For Perspectives and Power Dynamics, Protection, and Place, there were additional subcodes under the inductive parent codes which were not relevant for this paper and/or have already been published elsewhere. For example, the parent code “Barriers” included “age-restrictions”, relating to accreditation difficulties faced by under 18 year-olds, which was not included in the analysis for this paper, as it does not relate directly to any of the 7Ps (NB: this regulation also changed during the study to increase access for 16 and 17 year-olds). As an example of data which were excluded here due to being published elsewhere, see Thew et al. (2020), which provides more detail on the subcodes included under “Youth Justice Claims—Procedural”.

Reliability was established through the triangulation of multiple data sources (interviews, observations, and document analysis); ongoing reflexivity regarding researcher positionality and how it shapes data collection and analysis; and communicative validation, i.e., using repeat interviews with the same participants over the course of longitudinal study, as well as informal conversations during UNFCCC conferences and UKYCC team meetings to check the interpretation of previously collected data [

41]. In the results section below, participants are referred to with pseudonyms to protect their anonymity.

3. Results

In this section, we apply Cahill and Dadvand’s 7P model [

13] to our data, testing its utility for the study of youth participation in the UNFCCC. Here, we analyse our data through the lens of each P, guided by Cahill and Dadvand’s prompts. Given the space limitations, we are unable to respond to each one, instead selecting those which are most crucial in establishing the context or in contributing novel empirical findings. Prompts suggested by Cahill and Dadvand are labelled “prompt”, whilst those proposed by this paper are labelled “additional prompt”.

3.1. Purpose

The UNFCCC’s overarching objective is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations to prevent dangerous climate change [

42]. The drive to involve young people can be traced to a commitment to:

“encourage the widest participation in this process, including that of non-governmental organizations [and] promote and facilitate […] public participation in addressing climate change and its effects”

By widening participation, the UNFCCC aims to increase effectiveness by inviting contributions from NSAs to supplement and support action by SAs, in line with neoliberal governance norms and the framing of climate change as a collective action problem.

We find that youth participants in the UNFCCC pursue several goals beyond supporting SAs. This includes making connections with peers around the world and building a global youth movement. They also report on conference proceedings to increase transparency, maximise public scrutiny, and increase pressure on government negotiators. For example, several participants have been involved in a campaign claiming a “conflict of interest” inherent in fossil fuel industry representatives attending and sponsoring the climate negotiations. This conflicts with the UNFCCC’s purpose of encouraging the widest participation possible, as young people call for restrictions on attendance.

We also find that youth participants pursue individual goals, seeking to enhance their employability by building professional networks and developing skills such as blogging, vlogging, tweeting, organising events, learning about policy and campaigning, and writing press releases. These goals are easier to achieve, as they fall within young people’s locus of control rather than being dependent on engagement with other, more powerful actors. The latter can be frustrating so, as a strategy to reduce negative psychological impacts (discussed in

Section 3.7), more experienced youth encourage newer recruits to pursue personal development goals, carefully managing expectations regarding youth influence in the UNFCCC.

3.2. Positioning

Section 1.2 highlighted how cultural discourses position young people as apprentices rather than as agents of change. Some youth participants use this to strengthen individual career trajectories, whilst others recognise its limitations:

- Jenny:

- “I’ve heard, ‘you’re gonna grow up to be Heads of State one day’. [Other young people] have said, I want to be there one day so this is a step on the ladder. But that doesn’t really empower them to think they have power now to do stuff.”

Government and UN representatives often emphasise that youth remind negotiators of the real world, keeping diplomats and delegates focused. This positions young people as crucial for contextualising decisions, a role many are keen to accept:

- Grace:

- “We give something that helps bring it back to real people. It’s about people’s lives […] It is very easy to dehumanise things and forget the magnitude of what all of these particles per million numbers actually mean.”

However, their ability to achieve this may be hindered by the social construct of an “ideal global youth citizen” [

23], which emphasises that negotiating sustainability at the global level should focus on shared challenges, guided by “universal” rather than local knowledge. Furthermore, this positioning places a moral responsibility upon young people to provide a counterweight to neoliberal capitalist rhetoric, with youth (alongside some other NSAs) calling for policymakers to focus on “people not profit”.

- Noor:

- “It’s our own voices that we bring. We are not representing a country or an organisation or a company, we’re just representing what we believe is right and I think that’s quite rare in the talks.”

Many young people accept this moral responsibility, and it drives their continued engagement in the face of adversity. Several of our participants repeatedly engage in difficult social interactions at personal cost due to a perceived belief that if they do not advocate for future generations and for vulnerable groups in the present, climate action will be unjust. They share this driver with other climate justice activists; however, in positioning themselves (and being positioned by others) in opposition to the status quo, youth struggle to balance this role with a competing position they are expected to fill in society: as apprentices, expected to “learn the ropes” and defer to the expertise of older generations.

The societal positioning of youth as apprentices expects young people to “

develop their human capital as self-governing and responsible citizens” [

23] (p. 931), i.e., it suggests they have a responsibility to society to learn to be citizens in line with adult norms and values. This is particularly challenging in the UNFCCC, where they are simultaneously positioned as having a moral responsibility to oppose existing norms. As a result, adult expectations in the UNFCCC vary widely, with some expecting young people to get angry and demand change, whilst others expect young people to listen, learn, and, when asked, offer creative incremental suggestions to improve policies. This causes confusion and tension over young people’s role, leading to negative psychological impacts, as discussed in

Section 3.7.

3.3. Perspectives

The UNFCCC negotiations privilege government perspectives, restricting NSA access to certain spaces and their ability to speak to designated timeframes (e.g., two-minute interventions in plenaries). Within these restricted opportunities for participation, YOUNGO has the additional challenge of representing a large, diverse international membership of 10,000+ individuals from 100+ organisations. Although nominally open to all, the diversity of perspectives shared is limited by a lack of financial support, restricting participation to those who can self-finance, who are usually middle-class and from the Global North.

Our research participants were acutely aware that the lack of diversity in UKYCC and YOUNGO reproduced inequality and sought to broaden inclusion with recruitment strategies targeting new members through a wide range of social media networks including faith-based and community groups. To reduce the impact of hidden prejudices shaping recruitment decisions, they also introduced name-blind applications.

Despite their efforts to increase diversity and inclusion, structural barriers were more difficult to overcome. As UKYCC’s online meetings are usually held in the evenings, and in-person meetings often span whole weekends as participants gather from across the UK, young people studying or working outside of a 9–5 schedule struggled to engage. UNFCCC conferences take place over two weeks, during which youth participants have to fund their own accommodation, in addition to national and international travel to conference locations that change each year, marginalising lower-income groups. Accommodation during COPs is often mixed-gender, and meetings are often held in places where alcohol is served, creating potential barriers to the inclusion of youth from different faiths and cultural backgrounds. As a result, the voices of particularly vulnerable and marginalised youth remain unheard.

Several youth participants seek to promote anti-oppression principles within UKYCC and YOUNGO, running training on acknowledging privilege and challenging patterns of domination. However, as young volunteers with limited time and capacity, there is a need for adult institutions to lend support. For example, funding could be provided and structures put in place to build the capacity of youth participants to engage with or secure the attendance of marginalised peers in their own countries and overseas. While YOUNGO does receive a small amount of designated funding for Global South participants, this needs to be substantially increased. Platforms with mechanisms for representation and accountability at local to national levels could also be devised, and regional meetings could be held where youth participants could foreground their local identities, knowledge, and experiences.

3.4. Power Relations

YOUNGO operates on consensus-based decision-making within a nonhierarchical structure, striving for all members to have an equal voice. Their stated values and principles include commitments to justice and equity, inclusiveness and diversity, and dignity and respect [

8]. YOUNGO meets daily during UNFCCC conferences, sharing insights and coordinating efforts. However, tensions do arise, requiring careful negotiation to reconcile diverse interests, exacerbated by the unequal numbers of attendees and distribution of resources between Global North and Global South participants.

Power relations within YOUNGO are also shaped by the dominance of the English language in globalised society, including within the UNFCCC. Daily meetings are conducted in English with translation provided only if someone volunteers, and this is usually limited to European languages, due to the barriers to participation for Global South youth. Attempting to mitigate this, speakers are asked to state their first language when addressing the group as a reminder of the difficulties for non-English natives, and hand signals are used that include an opportunity for participants to request clarification at any point.

Despite these efforts, power relations undoubtedly shape participatory experiences:

- Noor:

- “I think the way the UNFCCC is structured definitely pushes people to instrumentalise others. I personally felt it as being youth, but I could see that everyone was just using everyone else […] I mean it’s negotiations, if I can use you, if I can win something off you, I’ll give you something else. Maybe the fact that we’re literally doing negotiations affects the way we interact as human beings.”

This mindset can shape social interactions even when structures are in place to address unequal power relations. For example, each youth organisation must nominate one spokesperson, so that multiple individuals from the same organisation cannot dominate discussions. However, as YOUNGO activities are divided into a series of working groups, e.g., focusing on topics such as gender, adaptation, and health, and each working group is permitted a spokesperson, youth from the same organisation could take more seats at the table, intentionally or unintentionally gaming the system.

Enabling frank discussions of power and privilege and facilitating deliberative discussions between all stakeholders could help to address these issues, as could increasing formal opportunities and funding for youth organisations to work together and also to engage with other adult organisations to identify shared concerns and challenges, combining their resources rather than operating in silos and competing for SAs’ attention.

3.5. Protection

In UNFCCC policies, there are several references to youth vulnerability and calls for their protection. However, there is a lack of balance between what these policies advocate and how the UNFCCC facilitates young people’s conference participation. UNFCCC conferences have tight security, with metal detectors and scanners on entry, the digital monitoring of participant attendance, and numerous security personnel inside. As such, the material safety of attendees is addressed, though without differential treatment for youth. However, as unpaid volunteers, youth experience material risks which better-resourced participants do not. Many struggle to sustain themselves properly, as conference food is overpriced and often runs out during the long days. Conferences end late each evening, governments book nearby accommodation in advance, and youth often struggle to find affordable accommodation, travelling long distances at unsociable hours or risking their safety by “couch-surfing” with strangers.

There have been several reports of sexual harassment from security guards and other COP participants. The UNFCCC Secretariat has instigated a zero-tolerance policy on sexual harassment, though the onus is placed on victims to report it. YOUNGO has taken steps to nominate “safety officers” and create a harassment and assault reporting protocol with input from the Women and Gender constituency. UKYCC and other youth organisations operate buddy systems, encourage travel in pairs and regularly checking in on each other’s safety and wellbeing, demonstrating their agency. However, to achieve intergenerational justice in climate governance, their capacity would be better spent contributing to decision-making. We therefore propose that formalised institutional measures are needed to create safer conditions for youth participants with input from safeguarding experts.

3.6. Place

UNFCCC COPs annually change their location, rotating between continents. Each location has different implications for youth protection and their chosen methods of participation. For example, COP21 was held in Paris following a terror attack and the French Government’s declaration of a State of Emergency, which removed the right to assemble, preventing planned protests. As a result, our participants largely abandoned plans to engage in direct action in the city due to fear of police response:

- Jess:

- “I was totally devastated when I’d heard they’d cancelled the mobilisations because of the attacks in Paris…I couldn’t think of anything more depressing than COP21 failing, and then I realised what is more depressing is COP21 failing and civil society not even being able to shout about it….I feel very angry and frustrated that the one thing I thought we could do as ordinary people not in government, not in big businesses or big corporate NGOs has been taken away from us….People keep asking me what I’m doing, I’m like, I wanted to be doing [direct action] but I don’t want to get f*cking shot!”

Ahead of COP22 in Marrakech, UKYCC ran training on cultural sensitivity and safety, discussing the need for women to dress modestly and learning basic Arabic phrases. Again, they favoured “insider” strategies within UN-secured zones over “outsider” strategies such as street protests and nonviolent direct action, despite many participants favouring these activities and pursuing them in COP23 in Bonn, Germany, which was deemed a safer place for activism. However, a benefit for some is a barrier to others. Visa processes regularly limit Global South representation. For example, several young Nigerian delegates were not granted Schengen visas for COP23. This problem is not unique to youth but is exacerbated by their status as unfunded volunteers and compounded by difficulties in funding accommodation and subsistence in expensive cities.

Enhancing digital access and providing deliberative online spaces could help to address access challenges. Some conference sessions can be observed through webcasts, and digital opportunities for youth are facilitated by the UNFCCC Secretariat and partners, such as video and music competitions where approximately two winners annually gain COP accreditation and funding. However, these activities are conducted in silos with little engagement from non-youth and no clear input into decision-making. We propose that the facilitation of regional meetings could increase reach and reduce funding and visa restrictions along with funding support and the provision of time-limited visas on entry for all accredited participants to increase youth representation at COPs.

3.7. Replacing “Process” with “Psychological Factors”

Cahill and Dadvand’s final ‘P’ considers the relationship between “intent and methods” [

13] (p. 251), discussing the benefits of Participatory Action Research methods such as Photovoice. We suggest that this is a methodological consideration rather than a lens through which to evaluate youth participation, and, although relevant for their study, it does not lend itself to other methodological approaches. However, we do find that another key factor shaping youth participation is missing from the 7P model: psychological factors play a key role in motivating, shaping, and sustaining youth engagement in the UNFCCC, interlinking closely with the other Ps. We therefore replace Process with Psychological Factors and add three prompts which we explore below.

Fears for the future prompt young people to engage in the UNFCCC to mitigate future individual and social risks:

- Alexis:

- “I was in my final year of university […] It was getting to the end of the year and I realised, oh God I’m going to go out into the great big world and it’s really scary out there.”

- Liv:

- “I got to that point, because I’m 21 now and […] I’ve wasted a lot of time doing nothing to further what I want to do in the future.”

Many of our participants are also motivated by guilt, feeling morally compelled to address climate change as citizens of a developed country with greater responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions. This is exacerbated by their positioning, as discussed in

Section 3.2. It is also compounded by anticipated future guilt, with many reporting that they want to look back and tell their children that they tried. This motivates their continued engagement even when faced with frustratingly unequal power dynamics and risks to their personal safety, as discussed in

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5.

Youth have come to expect strong psychological impacts from their participation:

- Elena:

- “I’m worried about people, especially who haven’t been to COP before. I don’t think they realise how emotionally draining it is […] you need a month’s holiday just to get over it!”

Almost all participants report feelings of frustration, sadness, and distress, though some unpack these feelings in more detail than others:

- Alexis:

- “I couldn’t really afford to be in Paris […] I just didn’t have the emotional capacity to be there or to feel the emotions that I knew I’d feel if I stayed […] I just can’t deal with any more hopelessness […] I think my biggest barrier has been burning out. It’s a sustained thing, a build-up of being stressed out but not realising because you’re doing something that you love and are really passionate about […] You end up in quite extreme situations like COPs where you’re surrounded by people and sharing rooms […] and end up getting physically ill because you’re not eating and sleeping properly and I got to a kind of snapping point and just descended in the total opposite direction of what I’ve been doing and lost all motivation, energy, passion, I couldn’t see the positives […] culminated [sic] with the nature of doing stuff voluntarily means you don’t have any money and are worried about where you are living, all of those normal life concerns.”

This demonstrates that participation takes an emotional and even a physical toll, highlighting the links between psychological factors and protection.

Negative psychological impacts experienced by youth participants in the UNFCCC could be reduced if process facilitators took proactive steps to address the challenges raised in the other 6Ps. For example, we find that young people experience fear for the future, a sense of powerlessness, and frustration when positioned as simultaneously responsible for creating social change whilst expected to act as respectful apprentices and develop employability skills. Greater reflexivity from more powerful actors regarding their positioning of youth would reduce confusion and frustration.

We find that young people are engaging in coping behaviours to deal with these psychological impacts. Ojala [

43] identifies three coping strategies employed by children, adolescents, and young adults in response to climate change. Our participants pursue all three to some extent: (1) “problem-focused coping”, i.e., tackling climate change head on to reduce ones’ worry is attempted, though this is difficult given the aforementioned structural and cultural barriers; and (2) “meaning-focused coping”, which involves breaking down complex problems into more manageable actions, though this is also difficult, given unequal power dynamics between SAs, NSAs, adults, and youth and the blurring of responsibility within neoliberal governance. As a result, our participants primarily engage in (3) “emotion-focused coping”. This includes “hyperactivation”, i.e., blaming ones’ elf and expressing anger, pessimism, and fatalism, which can become overwhelming and can stifle ongoing engagement. It also includes discussing problems with peers to generate social support, which can be cathartic but also time consuming, diverting time and resources away from directly addressing climate change.

Furthermore, youth participants are impeded by the more immediate need to address challenges within the participatory process. This includes the safety concerns highlighted in

Section 3.5 and

Section 3.6 as well as the inclusion issues raised in

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4. The UNFCCC Secretariat and host governments of COPs could address some of these challenges, enabling youth to direct their limited time and resources towards problem-focused and meaning-focused coping, reducing their worries and fostering hope.

5. Conclusions

This paper applies a model from Youth Studies, the 7P model of youth participation by Cahill and Dadvand [

13], to an ethnographic study of youth participants in the UN climate change negotiations from 2015 to 2018, contributing interdisciplinary insights into the study of youth climate activism. We find the 7P model useful in facilitating a broad investigation of how youth participants navigate formal institutional structures, informal cultures of participation, and power dynamics in global climate change governance.

Building upon Cahill and Dadvand’s paper, we add six prompts to guide future applications of the 7P model, encouraging a multifaceted, critical analysis of youth participation from a variety of angles, consolidating all prompts into a single table to enhance its usability. We also propose the replacement of their 7th P, Process, which we feel is a consideration for research design rather than an analytical lens, with Psychological Factors, which we find plays a key role in shaping young people’s participatory experiences, interacting substantially with the other elements of the model, particularly in the emotive context of climate negotiations.

In addition, we offer novel empirical contributions on the participatory experiences of youth in the UNFCCC, including: a typology of purposes pursued by youth participants, a depiction of various ways that young people are positioned in the UNFCCC and the confusing and conflicting pressures placed upon them, and the identification of strategies used by youth participants to address asymmetrical power relations.

The recent rise to prominence of youth climate activists has given hope to scholars and practitioners suggesting that youth will “save the world”. This is attracting new research from sustainability and environmental scholars, which we propose would benefit from engagement with the Youth Studies literature, including, but not limited to, models of youth participation. Guided by this literature, we propose that further research must remain attentive to “social continuity” as well as to social change [

22], in particular, urging caution around the hyperbolic framing of youth as our long-awaited saviours and encouraging greater consideration of the psychological burden placed on young shoulders.