1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, green consumer behavior and knowledge [

1] have become vital for environmental and business reasons [

2]. From an environmental viewpoint, it is critical to discover new ways to control and lessen the negative effects of household consumption [

3] to achieve the sustainable developmental goals desired by the global community [

4,

5]. A more sustainable society can be achieved through changes in consumer consumption patterns [

6] since private consumer households contribute almost up to 40% of environmental damage [

7]. The consequences of environmental damage are global warming [

8], land erosion, animal species extinction, and environmental degradation [

9]. As a result, individuals seem worried about environmental issues. However, with all these consumer concerns, reports testify that only 4% of buyers buy green products [

10]. This attitude and behavioral inconsistency create a green gap. Huge capital investments by firms in green products, depletion of natural resources, and poor environmental conditions require a deeper understanding of how consumers decide to consume green products [

11,

12]. Such a case has also been observed with green electronic appliances manufactured with the least environmental hazardous materials and built to consume less electricity [

13]. Ali et al. [

14] concluded that green electronic appliances receive less acceptability by consumers than their conventional counterparts.

Previously, researchers have identified multiple social and psychological determinants of green buying intentions and behavior and concluded that environmental concern, awareness, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, social norms, product price, quality, intrinsic values, and habits influence the phenomenon considerably [

6,

15,

16,

17]. Wang and Zhang [

18] suggested that the consumer claims–action inconsistency can be described as a social dilemma due to its unique nature of trading off instant personal benefits with delayed collective benefits [

19]. Consumers may sincerely consider green consumption to be relevant without letting it determine their choice in an actual context [

20]. The social dilemma approach tends to predict consumer decisions, particularly when encountering social and cognitive conflicts of benefits [

18]. Johnson and Greenwell [

20] asserted the importance of viewing the green claim–action inconsistency, which might be viewed from the social dilemma, normative, and moral perspectives. Social dilemma theory makes it possible to derive predictions about people’s pro-environmental behavior with assumptions counting on consideration of future consequences, personal norms, self-efficacy, and normative influence [

15,

21,

22]. Johnson and Greenwell [

20] identified and described environmental problems as a social dilemma, influencing consumer behavior in such scenarios. However, the exact mechanism of the social dilemma of how social and psychographic factors influence green consumer behavior needs to be thoroughly discussed. It deems it insightful to understand the impact of consideration of future consequences, self-efficacy, injunctive norms, and personal norms as antecedents leading to purchasing intention for green electronic appliances.

According to Landon et al. [

23], green consumer behavior is a blend of rational and moral decision making. A framework containing both dimensions predicts adaptive consumer decisions towards green consumption. However, the moral and ethical presumption for pro-environmental behavior is less researched [

2]. The current study derives motivation from this potential research gap positively. According to Nystrand et al. [

24], one explanation of pro-environmental intentions and subsequent behavior is found in an individual’s characteristics; for example, people who generally consider the long-term consequences of their behavior are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behavior because their current behavior is more guided by temporally distant goals. In particular, an individual’s personality characteristics in consideration of future consequences are critical in environmental studies [

25].

Moreover, Hussain et al. [

26] found that environmental self-efficacy discriminates between buyers and non-buyers of green products based on these results; they argued that self-efficacy affects environmental behavior. However, Sandhu et al. [

9] claimed that behavior is based on injunctive social norms. Moreover, moral decision making and considerations are important when explaining green consumer behavior.

This study highlights the criticality of evoking intrinsic moral motivation within individuals, forcing them to act pro-environmentally. Value, belief, and norm [

23] theory for environmentalism reflect a theoretical relationship between variables (predictors) and green consumer behavior. Asian countries, specifically Pakistan, face poor environmental situations [

27]. Consumers and governmental institutions are concerned about environmental degradation [

26,

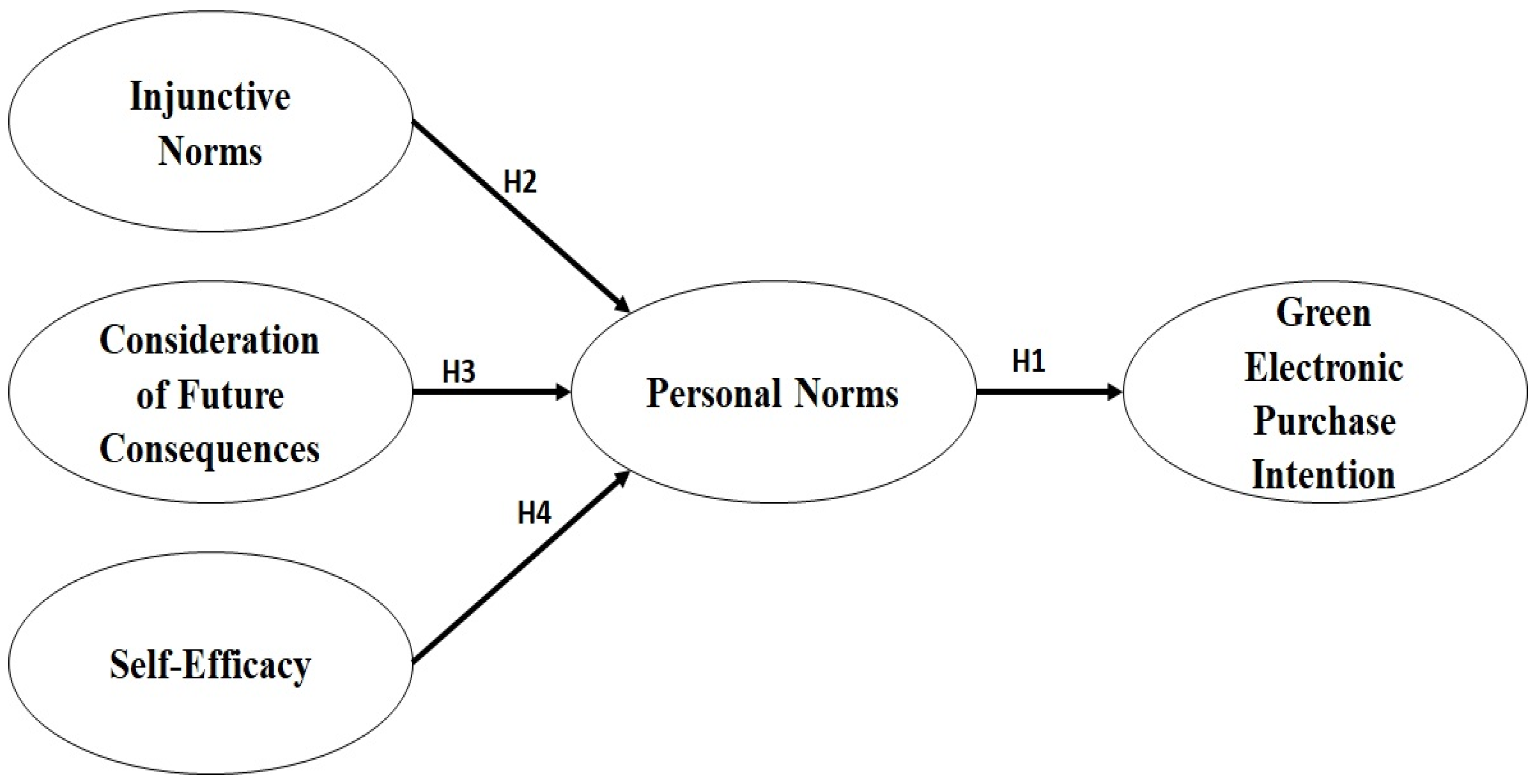

28]; however, from the consumers’ side, such concerns seldom reflect their choice to buy green products. To address this critical issue, it is important to study the effects of psychographic factors (consideration of future consequences), self-efficacy, and normative factors (injunctive norms) on personal norms and consequent consumer purchase intentions. This study also examines whether personal moral norms mediate between injunctive social norms, consideration of future consequences, self-efficacy, and buying intentions of green electronic appliances. The findings of this study will provide valuable insights to related stakeholders, such as environmental researchers, organizational policymakers, and marketers, and will enhance their understanding of designing and promoting eco-friendly products in society. The theoretical framework of the study is given in

Figure 1.

4. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

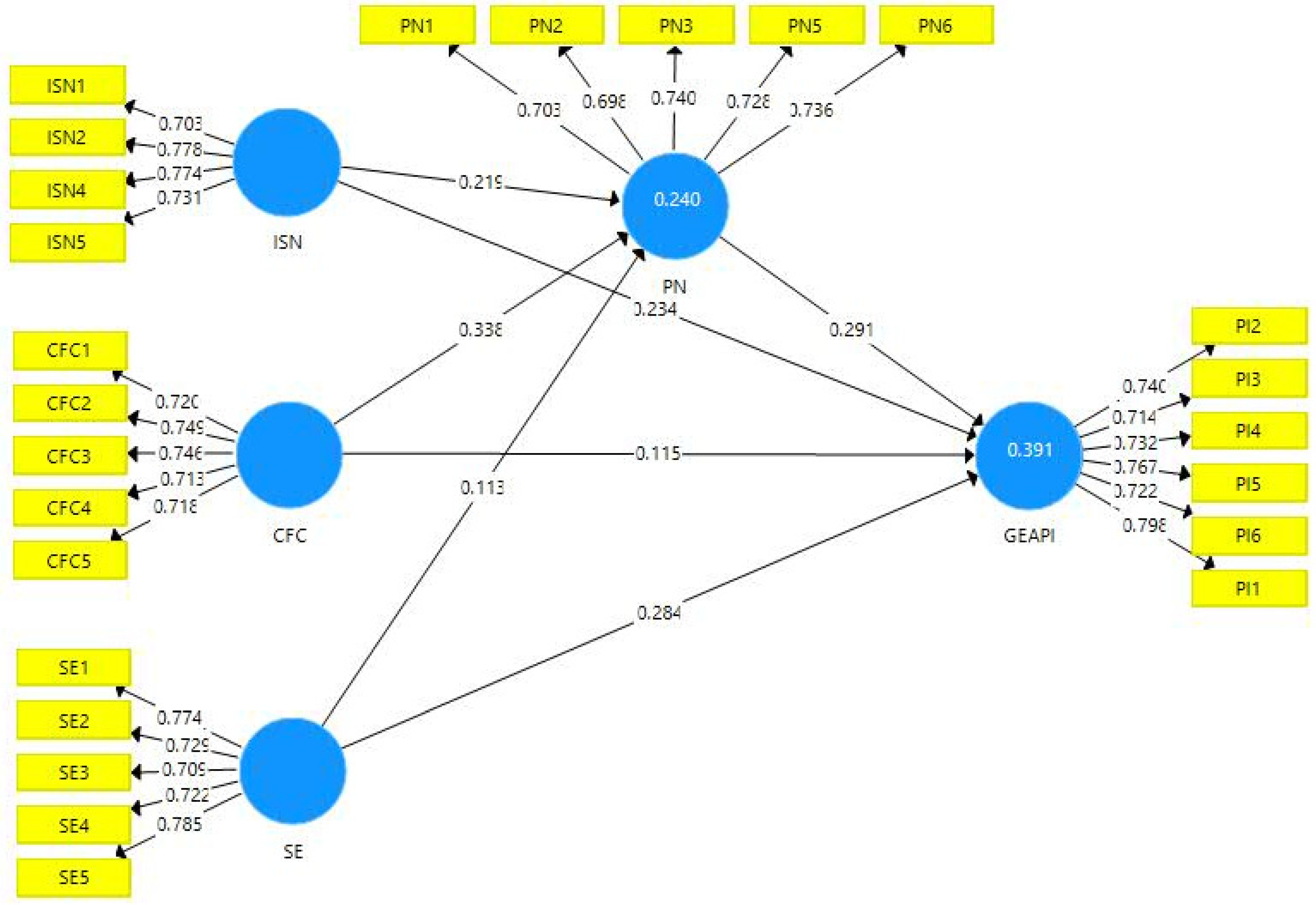

Environmental awareness is increasing among societies. Therefore, globally businesses have started to focus on producing and marketing green electric appliances. The same goes with Pakistan, where consumer focus on environmentally friendly products is on surge due to these products’ beneficial character towards society and the environment. The study found that personal norms significantly contributed toward GEAPI with the path coefficient b = 0.291. The result is substantially high and indicates that personal norms are strongly related to green electronic appliances purchase intentions. This indicates that consumers with charged intrinsic motivation to save the environment and society would likely buy green electric appliances. Hence, analyzing the relationship between personal norms and intentions to purchase in a green context is befitting to guide green marketers and manufacturers about the critical elements that trigger personal norms. The consequent application of study guidelines would help to activate personal norms and generate resultant consumers’ purchase intentions towards green electronic appliances.

Injunctive social norms showed a significant positive effect on personal norms with b = 0.219, a substantial effect; hence, H2 was supported. Personal norms mediated the relationship between injunctive social norms and purchase intention towards green electric appliances, and thus H5 was supported. Injunctive social norms strongly triggered the personal norms, with b = 0.219. These results show that people were more likely to plan on choosing an eco-friendly electronic home appliance when they believed that important others expect them to (i.e., injunctive social norms) and that they have a moral obligation to do so (i.e., personal norms). In green buying, social norms mostly focused on cost-effectiveness, i.e., low personal cost to pro-environmental behavior. The present study plans to extend the investigation to costly environmentally friendly behavior, as such behavior involves higher personal costs, based on respondents’ responses to the query regarding how likely will they choose a pro-environmental electronic home appliance product, even if it may lead to personal inconveniences and be more expensive.

The present research intended to test if an interaction exists in case normative messages are used to covey determination and zeal to lessen environment-related problems attached to green buying. The empirical findings verify that injunctive social norms realize the right thing to do, internalization into the self and integration with the self-concept. While injunctive social norms motivate behavior primarily by anticipating affective states such as guilt or pride, integrated norms can motivate behavior without being enforced by negative affect or ego enhancement [

74]. Hence, advertising cues spread the message in society that environmental protection is important, and just considering green electric appliances because it is righteous conduct may increase the consumers’ intentions to buy green electric appliances.

Furthermore, future consequences positively affected personal norms, with b = 0.338; H3 is thus supported. Similarly, personal norms mediated the relationship between future consequences and purchase intention towards green electric appliances; therefore, H6 is supported. While injunctive social norms strongly triggered the personal norms with b = 0.098, these results show that people were more likely to plan on choosing an eco-friendly electronic home appliance when they believed that their current purchase would bring future consequences. This perception further triggered the moral obligation to support the cause (i.e., personal norms).

Similarly, self-efficacy indicated a significant positive effect on personal norms, with b = 0.113, proving a moderation effect; hence, H4 is supported. Additionally, personal norms mediated the relationship between consideration of future consequences and purchase intention towards green electric appliances, and thus H7 is supported, while injunctive social norms strongly triggered the personal norms with b = 0.015. It is evident from the results that an individual with the self-perception of the capability to buy green electric appliances would have a higher chance of buying them. This sense of self-capability not only urges intrinsic motivation in a person but also stimulates higher satisfaction.

Furthermore, this study contributes to the literature by examining the mediating role of personal norms between self-efficacy and green electric appliances purchase intentions. It is postulated that when a person feels self-capable in finding and buying green products (merely high priced and difficult to find compared to their counterparts), it creates a sense of moral motivation, consequently leading toward green purchase intentions. Furthermore, it highlights the mechanism of personal norms and self-efficacy as the instigators of self-regulatory contribution toward purchase intentions. This finding is in line with Pang et al. [

63], considering the occurrence of intrinsic gratification in the case of engaging in buying green products, where the researcher highlighted intrinsic satisfaction multidimensionally. At the same time, the present study incorporated a unidimensional measure explaining one’s self-efficacy towards buying green products and evaluation of competence-related perception and intrinsic motivation of intentions. This research proposes that the link between self-efficacy and personal norms explains the individuals’ intentions to purchase green electric appliances.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This research contributes to the literature by proposing a cognitive mechanism depicting injunctive social norms, consideration of future consequences, and self-efficacy influence on green electric appliance purchasing intention with a mediating role of personal norms. Moreover, these findings contribute to the green purchase intention literature by incorporating the novel and mostly overlooked combination of constructs highly significant for triggering green intrinsic motivation and resultant intentions to buy green products. This research used norm activation theory rigorously to investigate the moral dimension related to behavioral intentions, as theories based on rational buying proved to be unable to cover pro-environmental behavior because those are more prone to focusing on attaining immediate self-gains [

44]. Second, this study analyzed the effect of considering future consequences on green purchase intentions through personal norms. Few past studies in the green context incorporated this construct in investigation [

53,

54,

57]; however, these studies used the construct in the general pro-environmental domain. Furthermore, those studies used CFC as a multi-dimensional construct, i.e., consideration of immediate and future consequences, whereas Pozolotina and Olsen [

51] supported using the construct one-dimensionally to oversee and sense the future orientation of consumers regarding the consequences of their current purchases.

Third, the present study applied injunctive social norms in the theoretical framework to analyze their impact on personal norms and green purchase intentions. Past studies investigated the arousal of personal norms and consequent green purchase intentions through social norms mostly in the descriptive sense, whereas injunctive social norms were largely ignored except for studies from Doran and Larsen [

37] and Sandhu et al. [

9]. Injunctive social norms proved to be significant in triggering moral motivation (personal norms), as such norms are subject to understanding the individuals’ social conduct regarding the righteous way to follow. Fourth, this study contributes to the literature theoretically by introducing self-efficacy into the research framework with other salient factors to understand consumers’ purchase intentions in the context of green electronic appliances. Self-efficacy is an important factor to determine intentions and behavior used in many past studies; however, most past studies tested it in isolation and in direct relationships, whereas the present study investigated its impact on purchase intention with the mediation of personal norms. The study results validate that individuals’ self-efficacy towards green electronic appliances instigates intrinsic moral motivation in an individual and consequently produces purchase intentions within one; hence, the study contributes to the literature. Therefore, the research enhances the knowledge of green purchase intentions and understanding of various motivations to buy green electronic appliances.

4.2. Practical Implications

Consumers and the retailers have welcomed the introduction of green electronic alliances in Pakistan. Consumers are more concerned about the real impact of the product on the environment. At the same time, green electronic marketers are still interested in increasing the demand for green electronic appliances among Pakistani consumers. This study offers practical insights for marketers and policymakers to increase consumers’ demand for green electronic appliances. First of all, the study proposes that being green comes when intrinsic motivation is there, so promotion messages or ads must contain moral messages containing situations regarding environmental degradation and the moral responsibility of an individual to save the environment. These messages can be coupled with the product offers and the product’s contribution to the biosphere.

Furthermore, the study proposes that the messages include contents related to the foresightedness of the individuals regarding the devastating impact of non-green product usage on the environment in the future. The marketers can also use the message content promoting that saving the environment through buying green electronic appliances is the right thing to do and that this conduct is what society expects others to follow. Moreover, marketers must convince consumers that they can save the environment through their green electronic purchases. Consequently, the pro-environmental consumer segment may swell, and their buying of green electronic appliances would contribute to environmental safety. This will produce a trickling up effect and increase the investors’ and government’s confidence in green electric appliances, due to which more investment in eco-friendly firms may surface.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

This research offered significant contributions; however, limitations cannot be ignored. Foremost, this study proposed the development of buying intentions through moral dimensions and impersonal cognitive instigators but did not discuss external factors. Moreover, the study limited itself to purchase intentions, and future research can investigate these factors’ influence on actual buying behavior. Furthermore, this study incorporated a cross-section design for data collection; future research can use a longitudinal design. Furthermore, for this study, the data were collected from different stores in Faisalabad, Pakistan; future researchers can collect the data from stores in multiple cities of Pakistan to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

5. Conclusions

Previous studies in environmental research empirically investigated the formation of intentions towards green purchases and behavior; however, the moral viewpoint and its instigators’ implication for purchase intentions are rarely researched. Specifically, past studies mostly investigated the determinants of purchase intentions with the perspective of rational motives such as attitude, perceived behavioral control, and social perspective, [

75]. According to the literature, green buying may not be sighted as rational behavior, as the benefits of such buying tend to be realized in the distant future. Furthermore, those are usually for the public good instead of self-interest. Therefore, green buying behavior may likely be viewed from a moral perspective. Therefore, this study takes a rigorous in-sight attempting to define purchase intentions through the moral dimension, i.e., personal norms and their triggering elements, i.e., injunctive social norms, consideration of future consequences, and self-efficacy.

Moreover, consideration of future consequences is a person’s characteristics that measure the future impact of their current purchases. Hence, it is a critical element to anticipate green buying. Previous research has paid limited attention to these important consumer characteristics. The current research contributes to the literature by analyzing the mediation of personal norms between injunctive social norms, consideration of future consequences, self-efficacy, and green electronic appliances purchase intentions.