Abstract

Enhancing the subjective well-being of new professional farmers is a crucial issue in China’s rural revitalization for modernization. This study was based on sample survey data collected in August 2020 by the Industrial Development Research Group at Xi’an Jiaotong University in the southern part of Shaanxi Province, China. It focused on exploring the influence of livelihood capital and income fairness on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers. The findings revealed the following: (1) Livelihood capital has a significant positive impact on subjective well-being among new professional farmers. The greater the accumulation of livelihood capital, the stronger their subjective well-being. (2) Income fairness significantly contributes to subjective well-being among new professional farmers. However, when comparing different social groups, variations exist in their subjective well-being. (3) Income fairness serves as a mediating factor between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. In other words, the accumulation of livelihood capital among new professional farmers affects their perception of income fairness, which subsequently influences their subjective well-being. These results have important implications for enhancing the well-being of new professional farmers, promoting the modernization of Chinese agriculture, and advancing the implementation of rural revitalization strategies.

1. Introduction

Rural revitalization stands as a major strategic objective in China’s social development agenda. The rapid pace of urbanization led to an outflow of rural laborers, resulting in an increasingly hollowed-out and aging rural population. These transformations pose new demands and challenges for the economic development of rural areas and the construction of a new countryside. According to statistics from the State Council, the urbanization rate, measured by the percentage of permanent residents in urban areas, swiftly escalated from 17.18% in 1978 to 63.89% [1]. This process deepened two notable phenomena: first, the rural-to-urban migration of populations, and second, the structural shift from agriculture to industry. Consequently, rural regions experienced a shortage of labor, land loss due to uncultivated fields resulting from labor migration, and declining agricultural productivity. To address these issues, the Chinese government introduced the “Rural Revitalization Strategic Plan (2018–2022)”, explicitly emphasizing the need to enhance the rural environment, revitalize human capital support, facilitate the convergence of modern production elements such as technology and information in rural areas, and cultivate a cohort of “culturally knowledgeable, technologically skilled, business-savvy, and management-proficient” new professional farmers [2]. This strategy aims to expand the talent pool for rural revitalization in China, providing robust support for the implementation of rural revitalization strategies and the modernization of agriculture and rural areas.

Under the guidance of the Chinese government, a momentous announcement declaring victory in poverty alleviation was achieved through multifaceted efforts. This accomplishment stimulated extensive research on new professional farmers within the academic community. While these studies yielded significant findings, the actual development situation remains less than ideal [3,4,5]. Issues such as the lack of recognition of agricultural value, the absence of long-term systematic planning, and insufficient attention from grassroots governments [6,7,8] resulted in challenges concerning the knowledge and technological proficiency of new professional farmers, outdated production methods, scarcity of talent resources, and backward ideologies [9,10]. Among these challenges, the widening disparity in wealth and poverty between urban and rural areas, as well as the exacerbation of social stratification and conflicts arising from income and distribution inequities, have become destabilizing factors in the development process of new farmers. Research indicates that the increasing internal disparities among farmers, primarily driven by income inequality, are the main obstacles to the development of new professional farmers [11], consequently further impacting their subjective well-being [12]. The active participation and initiative of new professional farmers in rural revitalization are intrinsic factors influenced by their perception of a harmonious living environment, thereby highlighting the significance of subjective well-being as a manifestation of their engagement in rural revitalization and the urban–rural integration strategy [13].

The subjective well-being of new professional farmers in China, as a distinct group within the agricultural sector, plays a crucial role in their sustainable development. This issue holds significance not only for the advancement of new professional farmers in China but also for countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and South Korea, which serve as relatively representative examples with earlier experiences in the development of new professional farmers [14,15,16,17,18]. Happiness among farmers is an abstract concept, and its ultimate meaning lies in the evaluation of subjective well-being through factors such as income distribution fairness, income disparity magnitude, and reasonableness. Social comparison theory posits that individuals engage in social comparisons when they seek to evaluate themselves, comparing their own living conditions with those of individuals in their social environment and forming subjective judgments based on these comparisons [19]. These comparisons are often rooted in the assessment of individual or household social capital stocks. Some scholars argue that social capital contributes to improving farmers’ income levels [20], and farmers primarily utilize social capital to address their livelihood needs. Professor Scoones from the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex defined livelihood as a series of actions taken by farmers utilizing existing resources to enhance their personal production and livelihoods [21]. Thus, this article focused on examining the relationship between the subjective well-being of new professional farmers and their perceptions of income fairness and livelihood capital. Accordingly, the article sought to address two fundamental questions: firstly, what is the impact of livelihood capital and the perception of income fairness on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers? Secondly, what is the effect of the perception of income fairness on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers and their livelihood capital?

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Livelihood Capital and Subjective Well-Being

Livelihood capital encompasses the collection of resources and capabilities, including natural capital, human capital, physical capital, financial capital, and social capital, that individuals or households possess or have access to, and which utilize to improve their livelihood and living conditions [22]. The role of livelihood capital extends throughout various stages of agricultural production and management activities, thereby influencing the outcomes of new professional farmers’ agricultural endeavors. Specifically, natural capital refers to the natural resource individuals possess or have access to, including land and water sources, which represent inherent conditions in the natural environment. Human capital encompasses individuals’ skills, abilities, and health conditions. Material capital refers to the production means and infrastructure necessary for sustaining livelihoods, such as housing conditions and transportation facilities. Financial capital represents the financial resources and assets utilized to achieve livelihood objectives. Social capital denotes the social resources individuals utilize in pursuing their livelihood goals, including social networks and social support [23,24,25,26].

For new professional farmers, the stock of livelihood capital directly influences their quality of life and level of happiness [27,28]. Firstly, agricultural production requires a significant amount of labor input, and good physical health is undeniably the foundation for productive work. The level of agricultural knowledge and technology plays a crucial role in improving agricultural productivity. Furthermore, a sound educational background can assist agricultural industry operators in making informed business decisions and developing management strategies [29]. Therefore, the impact of human capital on subjective well-being primarily achieves through the effects of education and health conditions on the objectives of agricultural production and management [30]. Secondly, material capital provides the essential foundation for individuals’ livelihoods and production. The abundant material capital possessed by new professional farmers actively contributes to meeting their daily life needs [31]. Additionally, the total assets of the agricultural industry at the end of the year represent the financial outcomes of farmers’ production and management efforts, satisfying the need to realize self-worth and enhance subjective well-being [32]. Lastly, social capital is the social resource embedded within an individual’s social network that can be mobilized. On one hand, social capital provides individuals with emotional support in their daily lives, fulfilling their developmental needs [33]. On the other hand, social capital compensates for deficiencies in formal institutions by providing new professional farmers with agricultural production and management information and resources [34]. It is evident that the stock of livelihood capital is a crucial factor in meeting the occupational development of new professional farmers, enabling them to gain a competitive advantage in the industry, thus enhancing their subjective well-being. Based on these considerations, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1:

New professional farmers’ livelihood capital has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 1a:

New professional farmers’ natural capital has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 1b:

Human capital of new professional farmers has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 1c:

New professional farmers’ physical capital has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 1d:

Social capital of new professional farmers has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 1e:

New professional farmers’ financial capital has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

2.2. Sense of Income Equity and Subjective Well-Being

Social comparison theory, also known as equity theory, is essentially an incentive theory that emphasizes the influence of the reasonableness and fairness of the distribution of wage compensation on workers’ motivation to produce [35]. Social comparison theory believes that everyone consciously or unconsciously compares the compensation they receive, either with their own work commitment or with the compensation of others, and when people believe that their income meets their psychological expectations in the process of social comparison, they will feel psychologically balanced and believe that they are treated fairly, and, thus, feel comfortable and have positive emotions.

Within academic discussions on the mechanisms through which income fairness affects subjective well-being, two main perspectives emerged. The first is structural determinism, which scholars often approach from the relative deprivation theory. They argue that individuals who occupy advantageous positions within the social structure tend to benefit from the existing income distribution system and are more inclined to maintain the current institutional arrangements. Conversely, individuals with lower socioeconomic status do not benefit from these arrangements, leading to a sense of deprivation and perceiving their income as unfair [36]. The second perspective is local comparison theory. Based on social comparison theory, individuals typically compare themselves to others within their own region or industry to assess the fairness of their income. When their income is significantly lower than the average income of their surrounding group or industry peers, a sense of unfairness arises. Studies analyzing relevant literature highlight the subjectivity of fairness, particularly in the selection of reference groups, as the choice of reference group can influence individuals’ judgments regarding income distribution fairness [37]. Research on local comparison variables’ impact on the perception of income fairness focuses on two aspects: socioeconomic status relative to peers and socioeconomic status relative to one’s past [38]. In addition to structural and local comparison theories, individual characteristics such as occupation, age, and educational level are significant factors that influence perceptions of income unfairness among farmers [39]. Some scholars examined gender differences in the perception of income fairness, but the results suggested that gender lacks explanatory power in this context, possibly due to the persistence of strong traditional gender norms in modern society [40].

Within the attribution research on income fairness, few scholars considered livelihood capital as an explanatory variable. Li Liming (2017) conducted an analysis based on the survey results of “Social Network and Occupational Experience” (JSNET 2014) conducted in eight cities in 2014. The study found a positive effect of relational capital mobilization on individuals’ perception of income distribution fairness [41]. In this context, the variable of “relational capital mobilization” corresponds to the concept of livelihood capital in this paper, thus providing support for the hypothesized relationship between livelihood capital and perception of income fairness. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed in this paper:

Hypothesis 2:

The sense of income equity earned by new professional farmers has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 2a:

Compared with their own efforts, the income equity earned by new professional farmers has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 2b:

Compared with their peers, the income equity of new professional farmers has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

Hypothesis 2c:

Compared with others in the society, the income equity of new professional farmers has a significant positive effect on subjective well-being.

2.3. Livelihood Capital, Sense of Income Equity and Subjective Well-Being

Livelihood capital, as the material foundation for individuals’ happiness, is reflected primarily through income, and the perceived fairness of income serves as the psychological basis for people’s happiness. Since Easterlin’s introduction of the “happiness paradox” in 1974, the academic community has been interested in studying the impact of income on individuals’ subjective well-being. However, this line of research has been subject to significant controversy, primarily due to the social and economic nature of subjective well-being [42]. Existing literature often relies on large-scale survey data, but overlooks the influence of exogenous factors such as regional policies, culture, and natural environment on individuals’ subjective well-being [43,44,45]. Regarding the study of the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being among new professional farmers, previous research typically suffers from limited sample sizes, lacking representativeness at the village level. Some studies also neglected the influence of intrinsic and extrinsic social relationships on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers, while social networks represent the most significant factor contributing to differences in their subjective well-being [46,47].

With the development of social comparison theory, the academic community increasingly focused on studying the relationship between social comparison and subjective well-being. Research in this area often utilized relative income as a measure of social comparison. However, relative income, compared to the stock of livelihood capital, lacks objective characteristics. The measurement of relative income is subjective and ambiguous, making it challenging to disentangle the relationship between social comparison and subjective well-being [48]. The structural determination perspective posits that individuals’ perception of fairness largely depends on the extent to which their income benefits them within the same group [49]. Generally, when individuals perceive their income distribution as fair, they consider society as fair, leading to greater happiness and satisfaction in their chosen careers and lives [50]. It becomes evident that the level of income is not the primary determinant of people’s happiness; rather, the sense of fairness in income attainment is the key factor influencing subjective well-being. Based on these considerations, this study integrates the hypotheses regarding the relationships among livelihood capital, income, and subjective well-being among new professional farmers proposed earlier and further presents the following hypotheses:

Hypotheses 3:

Sense of income equity mediates the effect between livelihood capital and subjective well-being of new professional farmers.

Hypotheses 3a:

The sense of income equity obtained by new professional farmers compared with their own efforts mediates the effect between livelihood capital and subjective well-being.

Hypotheses 3b:

The income equity of new professional farmers compared with their peers mediates the effect of livelihood capital and subjective well-being.

Hypotheses 3c:

The income equity of new professional farmers compared with others in the society mediates the effect of livelihood capital and subjective well-being.

3. Data, Variables, and Methods

3.1. Data

The data for this study were sourced from a household survey conducted by the Industrial Development Research Group at Xi’an Jiaotong University in August 2020, focusing on the concentrated contiguous impoverished mountainous areas in the southern part of Shaanxi Province, China. To ensure sample representation across various geographic features and industrial forms, a cluster sampling method was employed to randomly select City A and City B from the three cities in southern Shaanxi. Subsequently, one county was randomly selected from each city. Based on the distance from the town to the county center and the overall industrial situation, four towns were sampled from each county. From each town, two villages were randomly selected. Finally, within each village, 20 households engaged in industry were randomly selected, and a questionnaire survey was conducted with the responsible person (head of household). It should be noted that during the sample selection process, the following criteria were required to ensure the representativeness of the sample: (1) being born in a rural household; (2) being responsible for agricultural (agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishery) industry, such as orchard owners, large-scale pig farmers, or tea sales company executives; (3) engaging in industry before 2019; (4) the current main industry assets (such as land, base, factory) located within the investigated county.

The survey was conducted by a team of researchers and student investigators who administered structured questionnaires to industry leaders. Following the “Questionnaire for Investigating the Driving Forces and Mechanisms of Rural Industrial Continuity and Development in Shaanxi Province (2020)”, the investigators conducted one-on-one interviews with industry leaders, completed the questionnaires, and performed dual-level checks on-site, supervised by team leaders and faculty members. Upon completion of all surveys, a dual-entry approach was employed, where two different data entry personnel independently entered the data from each questionnaire. Subsequently, the two sets of entries were compared to identify any inconsistencies, which were resolved through thorough verification of questionnaires and contacting the respondents. Ultimately, a total of 305 valid samples were obtained for analysis.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study was the subjective well-being of new professional farmers. It was measured using a self-reported scale. Specifically, respondents were asked the question “Overall, how happy do you feel with your life?” in the survey questionnaire. The participants were asked to select one of the following options based on their subjective judgment: 1 = “Very unhappy”, 2 = “Somewhat unhappy”, 3 = “Neutral”, 4 = “Somewhat happy”, 5 = “Very happy”. Each option was assigned a numerical value ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of subjective well-being.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

The independent variable in this study was livelihood capital. Livelihood capital is measured based on the five dimensions of the Sustainable Livelihood Analysis Framework developed by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) [51]. It categorizes livelihood capital into five distinct dimensions.

Natural capital: The measurement of natural capital in this study included the aggregation of freely available land for production and contracted land obtained through land transfer, representing the total acreage of land available for farmers’ production. Based on this, the surveyed farmers were categorized into four groups: low natural capital, relatively low natural capital, relatively high natural capital, and high natural capital, with corresponding values assigned from 1 to 4.

Human capital: The measurement of human capital in this study incorporated the assessment of physical health status and educational level. The evaluation of physical health status was based on subjective judgments by the respondents, where higher scores indicate better health conditions. Educational level was determined by the highest level of education attained by the respondents, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of education. Subsequently, the scores for physical health status and educational level were aggregated within a range of 1 to 12. Based on the obtained scores, the surveyed farmers were categorized into four groups: low human capital, relatively low human capital, relatively high human capital, and high human capital, with corresponding values assigned from 1 to 4.

Material capital: In this study, the measurement indicator for farmers’ material capital was the year-end fixed assets. The numerical value of year-end fixed assets was derived from the surveyed farmers’ “total assets as of 2019 in relation to their industries, including land, buildings, parks, equipment, products, funds, and other relevant assets”. Due to significant variations in the extreme values of year-end fixed assets among the surveyed farmers, a truncated approach was employed to restrict the range of values between 0 and 7 million yuan. Based on the total value of year-end fixed assets, the surveyed farmers were categorized into four groups: low material capital, relatively low material capital, relatively high material capital, and high material capital, with corresponding values assigned from 1 to 4.

Social capital: The measurement of social capital can be approached through two main methods. The first method is known as the naming approach, where respondents provide names, individual characteristics, and other information about members within their social networks, allowing researchers to measure their social capital accordingly [52]. The second method is the positional approach, which focuses on the structural positions of individuals’ social network members. In a social network survey conducted by Bian Yanjie among residents of five Chinese cities, the “Spring Festival visitation network” was utilized as a basis to measure individuals’ relational networks [53]. In this study, we chose to employ the “visitations during the Spring Festival” as a measure of the breadth of respondents’ social capital. Respondents were asked to indicate the number of relatives, friends, and acquaintances they visited during the Spring Festival, and after grouping the data, all respondents were categorized into four groups based on the number of visitations, with corresponding values assigned from 1 to 4. A higher score indicated a wider range of social capital. Furthermore, the positional approach was used to examine whether respondents had individuals within their social networks who were engaged in the same or related industries, government personnel, or employees of financial institutions. If present, a score of 1 was assigned. The total score obtained by summing these values was used to measure the heterogeneity of social capital among the respondents. Finally, based on the combined scores of the breadth and heterogeneity of social capital, the surveyed farmers were categorized into four groups: low social capital, relatively low social capital, relatively high social capital, and high social capital, with corresponding values assigned from 1 to 4.

Financial capital primarily refers to the cash, loans, and borrowings available for production and consumption purposes. First, the indicator used in this study included the year-end total income from farmers’ agricultural operations. Second, given that the surveyed area was a concentrated poverty-stricken region and the poverty alleviation policies enable farmers to receive certain fiscal subsidies or apply for small-scale loans from banks and other institutions, the accumulation of financial capital among farmers becomes possible. Therefore, the measurement of farmers’ financial capital incorporates the fiscal subsidies received and loans obtained from financial institutions. The total amount of farmers’ financial capital was derived by summing their total income, fiscal subsidies, and financial loans. Based on this, the surveyed farmers were classified into four groups: low financial capital, relatively low financial capital, relatively high financial capital, and high financial capital, with corresponding values assigned from 1 to 4.

Finally, in order to establish a comprehensive indicator of livelihood capital for new-generation professional farmers, this study initially employed principal component analysis. To ensure the validity of the livelihood capital variables, the original variable set underwent KMO coefficient and Bartlett’s test of sphericity before factor extraction. These tests were conducted to determine the suitability of conducting factor analysis. Using Stata 17 software, an exploratory factor analysis was performed on the secondary indicators of livelihood capital for new-generation professional farmers, namely natural capital, human capital, material capital, social capital, and financial capital. The results are presented in Table 1, revealing a KMO value of 0.613, which exceeded the threshold of 0.6. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a significant p-value of 0.000 at the 1% level, indicating the suitability of the original variable set for factor analysis.

Table 1.

Factor analysis test for livelihood capital.

Furthermore, utilizing the PCA (principal component analysis) method in Stata 17 software, an analysis was conducted on the variables of natural capital, human capital, material capital, social capital, and financial capital. This analysis resulted in the extraction of a factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1. Based on this factor, the comprehensive level of livelihood capital for new-generation professional farmers was predicted.

3.2.3. Intermediate Variables

When examining the mediating role of income fairness in the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being among new-generation professional farmers, this study employed three dimensions to measure income fairness based on different reference groups. These dimensions included: (1) “Compared to your work input and effort, do you perceive your income returns as fair?”; (2) “Compared to your peers, do you perceive your income returns as fair?”; and (3) “Compared to other members of society, do you perceive your income returns as fair?”. Each dimension was assessed on a scale ranging from 1 to 10, where a score of 1 indicated that the surveyed farmers perceived their income returns as completely unfair, while a score of 10 indicated complete fairness. Finally, the answers to the three questions were summed and averaged to obtain a comprehensive score representing the level of income fairness perception among new-generation professional farmers.

3.2.4. Control Variables

Based on relevant studies in the field, this study incorporated other potential factors influencing farmers’ subjective well-being as control variables in the model and recoded some of the variables. At the individual level, gender was treated as a binary variable, with a value of 1 for males and 0 for females. Age was calculated based on the respondents’ year of birth. Considering the nonlinear impact of age on subjective well-being, this study applied a squared transformation to the age variable. At the household level, marital status and whether the household was classified as impoverished were considered. Marital status was collapsed into two categories: married (coded as 1) and unmarried (coded as 0), combining the original six categories. Social environmental factors were measured by the residents’ relationships in the village or community where the respondents resided. Village/community residents’ relationships were derived from three dimensions: mutual familiarity, mutual trust, and willingness to help each other, and were summed to obtain a score ranging from 0 to 15.

3.3. Methods

This study consists of three main sections. Firstly, a descriptive statistical analysis was conducted to examine the basic characteristics of the new professional farmers’ livelihood capital, perceived income fairness, and subjective well-being. Furthermore, a correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationships between the independent and dependent variables. Secondly, an ordered logit model was employed to investigate the influences of various factors on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers, focusing on the dimensions of livelihood capital and perceived income fairness. Lastly, the three sub-dimensions of perceived income fairness were examined as mediating variables to test the mediating effect of perceived income fairness on the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being among new professional farmers. This analysis aimed to provide a better understanding of how livelihood capital impacts the subjective well-being of farmers and to shed light on the mediating role of perceived income fairness.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

According to Table 2, the mean value of subjective well-being reported by the surveyed new professional farmers was 3.901, which fell between “comparatively happy” and “very happy”. This suggests that, overall, the respondents’ subjective well-being was relatively high and exhibited a concentrated distribution. Regarding the three dimensions of perceived income fairness, the new professional farmers tended to perceive a moderate-to-high level of income fairness. Among these dimensions, the highest level of perceived income fairness was observed when comparing oneself to peers, with an average score of 7.53. Conversely, the lowest level of perceived income fairness was reported when comparing oneself to others in society, with an average score of 6.66. The composite measure of perceived income fairness was obtained by summing the scores from the three relevant questions and calculating the mean, resulting in a range of scores from 1 to 10. The average value for perceived income fairness among the new professional farmers was 7.05, further indicating that their perception of income fairness is moderately high.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of relevant variables.

Among all the samples, males accounted for 74.75% of the respondents, significantly higher than females. The age of the participants ranged from 24 to 74 years, with an average of 50.55 years. In terms of family factors, the proportion of married households was as high as 91.48%, and 26.56% of them were classified as impoverished households. The surveyed farmers rated the resident relations in their villages or communities relatively high, with an average score of 12.03. The composite measure of new professional farmers’ livelihood capital encompasses five indicators: natural capital, human capital, material capital, social capital, and financial capital. Natural capital was derived from the farmers’ available agricultural land, with the highest proportion found in the lower natural capital group at 33.77%, while the high natural capital group accounted for only 19.02%. Human capital was determined by the combined scores of the farmers’ health level and educational attainment. The proportion of low human capital was 0.66%, with the majority of farmers falling into the intermediate level, while the high human capital group accounted for 15.41%. Material capital was derived from the farmers’ year-end fixed assets, and nearly half of the respondents had a lower level of material capital. Around 44.26% of the respondents had material capital at a moderate level, either lower or higher, and 24.92% of the farmers had a high level of material capital. Social capital represents the overall level of the farmers’ social network breadth and heterogeneity. Most of the respondents had a low or moderate level of social capital. Financial capital is the sum of the farmers’ annual income from agricultural operations, financial subsidies received, and loans from financial institutions. The results indicate that the proportion of low and moderate financial capital groups was slightly lower than that of the higher financial capital groups.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix between the dependent variable and the independent variables. It can be seen that the subjective well-being of new professional farmers was positively correlated with livelihood capital, human capital, material capital, social capital, and financial capital, with correlation coefficients of 0.291, 0.079, 0.284, 0.248, 0.211, and 0.152, respectively. All these correlations were statistically significant at the 0.01 level, except for natural capital, which did not exhibit a significant correlation with subjective well-being. The overall income fairness perception of farmers was positively correlated with subjective well-being, with a correlation coefficient of 0.470, and this correlation was statistically significant at the 0.01 level. This indicates a significant positive relationship between income fairness perception and subjective well-being. Furthermore, the three sub-dimensions of income fairness perception were also significantly positively correlated with subjective well-being, with coefficients of 0.420, 0.379, and 0.336, respectively. Among them, in comparison to their own efforts, new professional farmers had the highest level of subjective well-being. Further regression analysis is needed to examine the specific effects of the independent variables on the dependent variable in more depth.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis.

4.3. The Effects of Livelihood Capital and Income Equity on the Subjective Well-Being of New Professional Farmers

This study employed an ordered logit model to examine the impact of livelihood capital and income fairness perception on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers. The results are presented in Table 4. Model 1 serves as the baseline model, while Model 2 includes the composite index of livelihood capital and income fairness perception in addition to the variables included in Model 1. Model 3 focuses on the five sub-dimensions of livelihood capital, and Model 4 analyzes the effects of income fairness perception for different reference groups on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers.

Table 4.

Ordered logit regression results of subjective well-being of new professional farmers.

In specific terms, holding other factors constant, the regression coefficient for farmers’ age was −0.243, significant at the 1% level. This indicates a significant negative relationship between the age of new professional farmers and their subjective well-being, suggesting that as age increases, they are more likely to report lower levels of subjective well-being. The regression coefficient for the squared term of age was 0.003, and in the “U-test” for age and its squared term, the p-value was 0.022. This suggests a significant “U-shaped” relationship between age and subjective well-being, implying that as age increases, farmers’ subjective well-being initially decreases and then increases. This indicates that farmers in the middle age range may experience lower levels of subjective well-being due to various life difficulties and pressures. Examining marital status, it was evident that married new professional farmers had significantly higher levels of subjective well-being compared to those who were unmarried, divorced, or widowed. Furthermore, the degree of friendliness in community relationships was significantly positively correlated with subjective well-being at the 1% level, indicating that harmonious relations among neighbors contribute to people’s sense of happiness.

In Model 2, after controlling for other factors, the new professional farmers’ livelihood capital was significantly and positively correlated with their subjective well-being at the 1% level, with a coefficient of 0.053. This implies that for every unit increase in livelihood capital, farmers’ subjective well-being was expected to increase by 14.5%, supporting Hypothesis 1. The regression coefficient for income fairness was 0.409, significant at the 1% level. This suggests that an increase of one unit in the overall level of income fairness among new professional farmers led to a 6.7% increase in their subjective well-being, supporting the Hypothesis 2.

In Model 3, the influence of natural capital on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers was not statistically significant, thus rejecting Hypothesis 1a. For every unit increase in the level of human capital among new professional farmers, their subjective well-being was expected to increase by 19.8%, supporting Hypothesis 1b. Similarly, a one-unit increase in material capital led to a 15.3% increase in subjective well-being, supporting Hypothesis 1c. An increase of one unit in social capital resulted in an 18.4% increase in farmers’ subjective well-being, supporting Hypothesis 1d. However, the effect of financial capital on subjective well-being was not statistically significant, rejecting Hypothesis 1e.

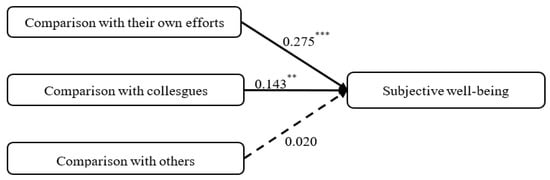

In Model 4, which incorporated the three sub-dimensions of income fairness, the regression results indicate that for every unit increase in the perception of income fairness compared to one’s own effort among new professional farmers, their subjective well-being was expected to increase by 6.7%, supporting Hypothesis 2a. The regression coefficient for income fairness compared to peers was 0.143, significant at the 5% level. This suggests that farmers perceive a stronger subjective well-being when they consider their income returns to be fair compared to their peers. Therefore, Hypothesis 2b is supported. However, it is worth noting that the perception of income fairness compared to others in society was not statistically significant, rejecting Hypothesis 2c.

4.4. Mediating Effect of Income Equity Perception on Livelihood Capital and Subjective Well-Being

To further investigate the mechanism through which income fairness among new professional farmers mediates the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being, this study introduced farmer income as a mediating variable. The mediation effect model was employed to examine the mediating role of income fairness in the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bootstrap method test for mediating effects of income perception of fairness.

Specifically, when the mediating variable was the composite index of income fairness, the total effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being was 0.251. The indirect effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being through income fairness was 0.058, while the direct effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being was 0.193. Both of these effects were statistically significant, as indicated by their confidence intervals not including zero. These findings demonstrate that livelihood capital of new professional farmers has a direct positive effect on subjective well-being, and income fairness partially mediates the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. Thus, research Hypothesis 3, which posits the mediating effect of income fairness between livelihood capital and subjective well-being among new professional farmers, is supported.

When the mediating variable was the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to their own efforts, the total effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being was 0.265. The indirect effect, however, was 0.045, and its confidence interval included zero. This suggests that the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to their own efforts does not mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. Therefore, Hypothesis 3a, which proposes the mediating effect of income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to their own efforts between livelihood capital and subjective well-being, is not supported.

When the mediating variable was the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to their peers in the same industry, the total effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being was 0.267. The mediating effect of income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to their peers in the same industry on the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being was 0.052. Furthermore, the direct effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being was 0.215. Both of these effects had confidence intervals that did not include zero and were statistically significant. This indicates that the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to their peers in the same industry partially mediates the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. Therefore, Hypothesis 3b is supported.

When the mediating variable was the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to others in society, the total effect of livelihood capital on subjective well-being was 0.249. The mediating effect of income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to others in society on the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being was 0.015. However, the confidence interval for this mediating effect includes zero, indicating that the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to others in society does not mediate the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. Thus, Hypothesis 3c is not supported.

In conclusion, income fairness plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being among new-generation professional farmers. However, among its sub-dimensions, only the income fairness derived from comparing one’s income to peers in the same industry was validated through Bootstrap testing.

5. Discussion

In contrast to existing research that predominantly investigates the diversification of new professional farmers using macro-level statistical data, micro-level case studies, or teaching models [46,47,54], this study introduced a novel analytical perspective. It employed a quantitative analysis of survey data directly collected from agricultural farmers in a specific province of China. This approach not only enhances our understanding of the developmental status of new professional farmers in China but also yields valuable insights for the examination of this emerging group of professional farmers, providing experiences and references applicable to agricultural development in other countries. Given the significance of agricultural development in China, the progress of emerging professional farmers bears substantial importance for the successful implementation of the rural agricultural revitalization strategy. Surprisingly, no previous study systematically analyzed the distinct circumstances of new professional farmers and their influence on subjective well-being from a micro-level perspective, encompassing the concept of livelihood capital stocks. In light of this research gap, our study established a theoretical foundation for an integrated analysis of overall household capital, considering it as a central perspective for the exploration of this topic.

The research findings indicated that the influence of material capital on farmers’ well-being is limited due to the moderate to low level of material capital generally possessed by farmers. Additionally, material capital exhibited a tendency of limited significant changes over a short period of time, resulting in a relatively weak happiness effect. This pattern is not unique to China but was observed in other developed countries as well [55]. The socio-economic development gap in rural areas poses constraints on the heterogeneity and attainment of social capital among farmers. Furthermore, influenced by local culture, emotional “strong ties” within farmers’ social networks prevail over instrumental “weak ties” [56,57]. Consequently, although social capital can positively impact farmers’ subjective well-being, its effect was significantly lower compared to that of human capital and material capital. Overall, the support provided by the state and government for new professional farmers is insufficient. Therefore, the development of new professional farmers should encompass considerations not only for the distribution of natural resources but also for the support and assistance provided by government financial policies.

Furthermore, as depicted in Figure 1, the agricultural development of new professional farmers in China is primarily dependent on their individual efforts and the support of their family and friends, as compared to other members of society. This can be attributed to the closer social proximity that facilitates their access to dynamic industry advancements and income-related information, leading them to engage in social comparisons with their peers regarding their levels of exertion and progress. It is important to note that this phenomenon is not exclusive to Chinese farmers, as similar patterns were observed in other countries [58,59]. On one hand, new professional farmers perceive their personal efforts as the primary avenue for enhancing their income, and social comparisons within their peer group serve to identify areas for self-improvement. This phenomenon extends beyond new professional farmers and encompasses other social strata as well [60,61]. On the other hand, the enduring influence of traditional Confucian culture in China continues to shape social relations among farmers, perpetuating entrenched thought patterns that may limit their opportunities for development. Consequently, their sense of happiness may not be directly linked to individuals belonging to other social strata.

Figure 1.

The effect of three sub-dimensions of perceived income equity on subjective well-being. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01.

The aforementioned findings indicate that new professional farmers possess heightened expectations regarding future income, resulting in a constrained perception of “prosperity satisfaction”. This observation offers insights into the reasons why rural populations, including those in China, who encounter economic and social disadvantages in comparison to their urban counterparts, demonstrate elevated levels of subjective well-being despite experiencing lower income levels [62,63,64].

6. Conclusions

This study examined the impact of livelihood capital and income fairness on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers, while also considering the mediating role of income fairness in the relationship between livelihood capital and subjective well-being. Three main conclusions emerged from the analysis. Firstly, livelihood capital significantly and positively influences the subjective well-being of new professional farmers. The greater the accumulation of livelihood capital, the stronger their subjective well-being. Specifically, human capital, material capital, and social capital exert significant effects on the happiness of new professional farmers, whereas natural capital and financial capital did not demonstrate a significant impact. Secondly, the perception of income fairness among new professional farmers was found to have a significant positive effect on their subjective well-being, but the extent of this effect varies under different social comparisons. Lastly, the perception of income fairness serves as a mediating factor between livelihood capital and subjective well-being for new professional farmers. This indicates that income fairness exerts its influence on the subjective well-being of new professional farmers through the stock of livelihood capital.

The findings suggest that the subjective well-being of new professional farmers necessitates a comprehensive approach encompassing various perspectives and dimensions, with a primary emphasis on fostering their intrinsic motivation for personal growth. By doing so, it becomes possible to advance the overall progress of rural agriculture within the context of rapid global economic expansion. However, despite the exploration of the interrelationships between livelihood capital, income fairness, and the subjective well-being of new professional farmers, this study encountered two limitations. Firstly, due to substantial regional disparities in China, caution should be exercised when generalizing the survey results and conclusions based on a single province. The study specifically focused on the Qinba Mountain region in southern Shaanxi Province, which is characterized by concentrated and persistent poverty. Therefore, the extent to which the research findings from this region can be generalized and representative of households nationwide necessitates further empirical validation through more extensive investigations. Secondly, while the sample selection criteria for this study targeted “agricultural industry managers” to ensure specific qualities related to business knowledge and management, the compatibility of this sample with the identity of new professional farmers requires further verification. Moreover, considering the data’s origin from a developing country, future research endeavors could integrate data from developed countries to facilitate comparative analyses. Additionally, the comprehensive development of new professional farmers represents a vital area warranting further investigation, as it offers valuable insights to guide China’s strategic pursuit of rural agricultural modernization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.N. and C.L.; data curation, L.N.; methodology, R.S.; writing—original draft, L.N.; writing—review and editing, C.L and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in our study.

Data Availability Statement

The relevant permission was obtained and all data in the paper are copyright free.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the people at Xi’an Jiaotong University for their assistance in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mao, Y. Theoretical innovation and policy exploration of modernization of urban agglomerations—Introduction to the topic. J. Zhongshan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Analysis on the Professional Development of New Professional Farmers under the Background of Rural Revitalization Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE 2019), Xiamen, China, 23–25 August 2019; pp. 828–831. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H. Discussion on the Cultivation of New-Type Professional Farmers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Economics and Management Research, Singapore, 29–31 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, Y.A.; Xrz, A.; Szb, C. Extenics based Innovation of New Professional Farmer Cultivation under the Strategy of Rural Vitalization-ScienceDirect. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 162, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Luo, C.; Cao, C.; Wei, Q.; Yu, J. Research on the Training Effect of New Farmers in Beijing. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2017), Guangzhou, China, 12–14 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, C.; Benoît, D.; Pascal, B. Professional transitions towards sustainable farming systems: The development of farmers’ professional worlds. Work 2017, 57, 325. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Environmental research on the influencing factors of skill training willingness of the new era professional farmers in the central region of China. Ekoloji 2018, 27, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Sun, S. Evaluation on the Development of Circular Agriculture in Guizhou Province Based on Entropy Method. Asian Agric. Res. 2015, 7, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.W.; Huang, L. Developing Status of Specialized Farmers Cooperatives—Based on the Investigation Data of 162 Villages in Sichuan Province, China. Asian Agric. Res. 2009, 1, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, K.; Moser, G.; Germann, C. Perception de l’environnement, conceptions du métier et pratiques culturales des agriculteurs face au développement durable. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2006, 56, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Churchill, S.A. Income Inequality and Subjective Wellbeing: Panel Data Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnqvist, J.E.; Deters, F.G. Facebook friends, subjective well-being, social support, and personality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. On the Varieties of People’s Relationships with Places: Hummon’s Typology Revisited. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 676–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzeau, L. “Being Stewards of Land is Our Legacy”: Exploring the Lived Experiences of Young Black Farmers. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 8, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creissen, H.E.; Jones, P.J.; Tranter, R.B.; Girling, R.D.; Kildea, S. Identifying the drivers and constraints to adoption of IPM amongst arable farmers in the UK and Ireland. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4148–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slámová, M.; Kruse, A.; Belčáková, I.; Dreer, J. O1d but not o1d fashioned agricu1tura1 1andscapes as european heritage and basis for sustainab1e mu1tifunctiona1 fanning to eam a 1iving. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.-Y. The Tendency of Publishing Nongmin-Dokbon and It’s Contents during the Japanese Colonial Periods. J. Korean Lang. Lit. Educ. 2016, 61, 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Tan, Z. Operational Efficiency of Family Farms and Influencing Factors Based on DEA-Tobit Model. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2015, 6, 577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, X.; Hai, Z.; Hou, C.; Zhang, F.; Liang, Z. Impact of Social Capital on Farmers’ Income: A case study in Zhangye City, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture of Gansu, China. J. Desert Res. 2014, 34, 610–616. [Google Scholar]

- Moepeng, P.T.; Tisdell, C.A. The Pattern of Livelihoods in a Typical Rural Village Provides New Perspectives on Botswana’s Development. Soc. Econ. Policy Dev. Work. Pap. 2008, 52, 123548. [Google Scholar]

- Context, V. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2000.

- Boncompte, J.G.; Paredes, R.D. Human capital endowments and gender differences in subjective well-being in Chile. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, T.; Yamaguchi, R.; Kagohashi, K.; Managi, S. Material and relational consumption to improve subjective well-being: Evidence from rural and urban Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, R. Unemployment, social capital, and subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterman-Smith, H.; Rafferty, J.; Dunphy, J.; Laird, S.G. The emerging field of rural environmental justice studies in Australia: Reflections from an environmental community engagement program. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanca-Tan, R.; Bayog, S. Livelihood and Happiness in a Resource (Natural and Cultural)-Rich Rural Municipality in the Philippines. Southeast Asian Stud. 2021, 10, 413–433. [Google Scholar]

- Selin, H.; Davey, G. Happiness across Cultures: Views of Happiness and Quality of Life in Non-Western Cultures; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- El-Osta, H. The impact of human capital on farm operator household income. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2011, 40, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjaya, I.G.A.M.P.; Suparta, N. Influence of Farmers Human Resources Quality and Group Conditions on Simantri Application Level in Bali. SEAS (Sustain. Environ. Agric. Sci.) 2018, 2, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Social capital, income and subjective well-being: Evidence in rural China. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptot, E.; Franzel, S. Voluntarism as an investment in human, social and financial capital: Evidence from a farmer-to-farmer extension program in Kenya. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. 6. Constituting social capital and collective action. J. Theor. Politics 1994, 6, 527–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerattanakorn, N.; Wiboonpongse, A. Happiness and community-specific factors. Appl. Econ. J. 2017, 24, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Friedkin, N.E.; Johnsen, E.C. Social Influence Network Theory: Social Comparison Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 160–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Income inequality and distributive justice: A comparative analysis of mainland China and Hong Kong. China Q. 2009, 200, 1033–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.P.; Wheeler, L.; Suls, J. A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Brown, R.J.; Tajfel, H. Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 9, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Valet, P. Social Comparison Orientations and Their Consequences for Justice Perceptions of Earnings; DFG: Bonn, Germany, 2013.

- McLean, C. Basic income and the principles of gender equity. Juncture 2016, 22, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, X. Market-oriented reforms, relational capital mobilization and sense of equity in income distribution. J. Soc. Sci. Jilin Univ. 2017, 57, 101–111+206. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, J.F. The rural happiness paradox in developed countries. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 98, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Robinson, J.P. Measures of subjective well-being. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes: Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; Volume 1, pp. 61–114. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R.; Zhai, Q. Subjective well-being of China’s off-farm migrants. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wang, J.; Fahad, S.; Li, J. Influencing factors of farmers’ land transfer, subjective well-being, and participation in agri-environment schemes in environmentally fragile areas of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 4448–4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yan, W.; Zhang, J. Relative income and subjective well-being of urban residents in China. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2019, 40, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, W.M.; Rossi, P.H. Who should get what? Fairness judgments of the distribution of earnings. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 84, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Xie, X. Community involvement and place identity: The role of perceived values, perceived fairness, and subjective well-being. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 951–964. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, D.; Drinkwater, M.; Rusinow, T.; Neefjes, K.; Wanmali, S.; Singh, N. Livelihood approaches compared: A brief comparison of the livelihoods approaches of the UK Department for International Development (DFID), CARE, Oxfam and the UNDP; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999.

- Lin, N. From Individual to Society: A Social Capital Perspective. Soc. Sci. Front. 2020, 2, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yanjie, B.; Li, Y. Zhongguochengshijiatingde Shehuiwangluoziben [Social Network Capital in Chinese Urban Families]. Qinghuashehuixuepinglun [Tsinghua Sociol. Rev.] 2000, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.-J.; Cheng, X.-M. Offspring Education, Regional Differences and Farmers’ Subjective Well-Being. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 2109–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Brabec, M.; Godoy, R.; Reyes-García, V.; Leonard, W.R. BMI, income, and social capital in a native Amazonian society: Interaction between relative and community variables. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2010, 19, 459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Zbarskyi, V.; Ovadenko, V. The Development of the Social Sphere of the Ukrainian Village: A Regional Aspect. Cherkasy Univ. Bull. Econ. Sci. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komornicki, T.; Czapiewski, K. Economically Lagging Regions and Regional Development—Some Narrative Stories from Podkarpackie, Poland. In Responses to Geographical Marginality and Marginalization: From Social Innovation to Regional Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S. Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy; McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019; Volume 94. [Google Scholar]

- Beitnes, S.S.; Kopainsky, B.; Potthoff, K. Climate change adaptation processes seen through a resilience lens: Norwegian farmers’ handling of the dry summer of 2018. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 133, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Boda, Z.; Lorenz, G. Social comparison effects on academic self-concepts—Which peers matter most? Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandan, D. Rethinking the health consequences of social class and social mobility. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoganandan, G.; Rahman, A.A.A.; Vasan, M.; Meero, A. Evaluating agripreneurs’ satisfaction: Exploring the effect of demographics and emporographics. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, P.R.; Grote, U. Do certification schemes enhance coffee yields and household income? Lessons learned across continents. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5, 716904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhsan, A.; Arsyad, M.; Amiruddin, A.; Salam, M.; Nurlaela, N.; Ridwan, M. In-Depth Study of Multiple Cropping Farming Systems: The Impact on Cocoa Farmers’ Income. AGRIVITA J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 44, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).