The Effect of Esports Content Attributes on Viewing Flow and Well-Being: A Focus on the Moderating Effect of Esports Involvement

Abstract

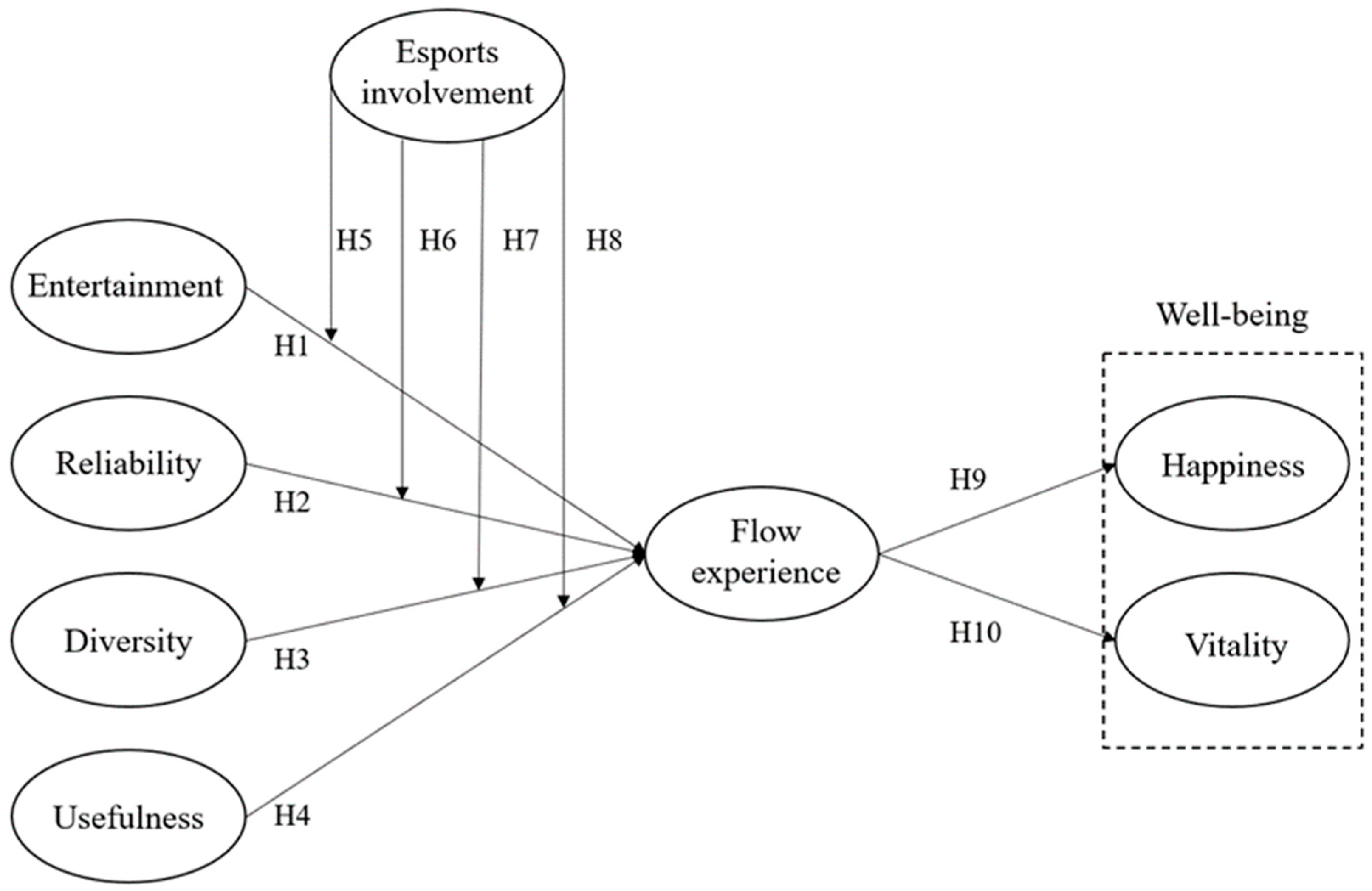

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Uses and Gratification Theory (UG) in Esports Livestreaming Service

2.2. The Attributes of Esports Content and Flow Experience

2.3. The Role of Esports Involvement in Viewer Experience

2.4. Flow Experience and Well-Being

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Model

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Agendas

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pizzo, A.D.; Su, Y.; Scholz, T.; Baker, B.J.; Hamari, J.; Ndanga, L. Esports Scholarship Review: Synthesis, Contributions, and Future Research. J. Sport Manag. 2022, 36, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D.C.; Pizzo, A.D.; Baker, B.J. ESport Management: Embracing ESport Education and Research Opportunities. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, S.E.; Manning, R.D.; Keiper, M.C.; Olrich, T.W. Virtual (Ly) Athletes: Where ESports Fit within the Definition of “Sport”. Quest 2017, 69, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee Olympic Esports Series. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/esports/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Newzoo. Global Esports & Live Streaming Market Report; Newzoo: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M. Spectator E-Sport and Well-Being through Live Streaming Services. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N.D.; Rieger, D.; Lin, J.-H.T. Social Video Gaming and Well-Being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.; Sum, S.; Chan, M.; Lai, E.; Cheng, N. Will Esports Result in a Higher Prevalence of Problematic Gaming? A Review of the Global Situation. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuss, D.J. Internet Gaming Addiction: Current Perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2013, 6, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, J.-H. Do Video Games Exert Stronger Effects on Aggression than Film? The Role of Media Interactivity and Identification on the Association of Violent Content and Aggressive Outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy, T.; Sharma, M.K.; Sahu, M.; Kanchana, D.M. Influence of Esports on Stress: A Systematic Review. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2020, 29, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohno, S. The Link between Battle Royale Games and Aggressive Feelings, Addiction, and Sense of Underachievement: Exploring ESports-Related Genres. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 20, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. Improving Well-Being through Hedonic, Eudaimonic, and Social Needs Fulfillment in Sport Media Consumption. Sport Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Thoughts on the Relations between Emotion and Cognition. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M. Media Uses and Effects: A Uses-and-Gratifications Perspective. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 417–436. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A.M. Uses-and-Gratifications Perspective on Media Effects. In Media Effects; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 181–200. ISBN 0-203-87711-X. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: The Experience of Play in Work and Leisure; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, B.-R.; Hur, J. A Study of the Relationship of Customer Orientation, Customer Satisfaction, Customer Trust and Loyalty of Fitness Center. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2019, 10, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Guerola-Navarro, V.; Oltra-Badenes, R.; Gil-Gomez, H.; Gil-Gomez, J.A. Research Model for Measuring the Impact of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) on Performance Indicators. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 2669–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, K.; Wagner, D.; Scheck, B. Reaping the Digital Dividend? Sport Marketing’s Move into Esports: Insights from Germany. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 15, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Lin, J.C.-C. The Effects of Gratifications, Flow and Satisfaction on the Usage of Livestreaming Services. Libr. Hi Tech 2021, 41, 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. The Effect of Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Happiness in Five Asian Countries. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, D.; Reinecke, L.; Frischlich, L.; Bente, G. Media Entertainment and Well-Being—Linking Hedonic and Eudaimonic Entertainment Experience to Media-Induced Recovery and Vitality. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and Gratifications Research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Stitt, C.R.; Halford, J.; Finnerty, K.L. Emotional and Cognitive Predictors of the Enjoyment of Reality-Based and Fictional Television Programming: An Elaboration of the Uses and Gratifications Perspective. Media Psychol. 2006, 8, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; David, M.E. Instagram and TikTok Flow States and Their Association with Psychological Well-Being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2023, 26, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Dhir, A.; Bala, P.K.; Kaur, P. Why Do People Use Food Delivery Apps (FDA)? A Uses and Gratification Theory Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Min, Q.; Han, S. Understanding Users’ Continuous Content Contribution Behaviours on Microblogs: An Integrated Perspective of Uses and Gratification Theory and Social Influence Theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C. What Drives Live-Stream Usage Intention? The Perspectives of Flow, Entertainment, Social Interaction, and Endorsement. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.E. Entertainment-Oriented Gratifications of Sports Media: Contributors to Suspense, Hedonic Enjoyment, and Appreciation. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2015, 59, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnie, P.-M.W. The Effects of Website Quality on Customer E-Loyalty: The Mediating Effect of Trustworthiness. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Acikgoz, F.; Du, H. Electronic Word-of-Mouth from Video Bloggers: The Role of Content Quality and Source Homophily across Hedonic and Utilitarian Products. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayomchai, A.; Chanarpas, M. The Service Quality Management of the Fitness Center: The Relationship among 5 Aspects of Service Quality. Int. J. Curr. Sci. Res. Rev. 2021, 4, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jeong, C.; Kim, N. Effect of Characteristics of YouTube Tourism Contents on Confirmation, Perceived Usefulness, Satisfaction and Loyalty: Application of the Expectation-Confirmation Model(ECM). Int. J. Tour. Manag. Sci. 2019, 34, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M. A Study on the Influence of Game Broadcasting Content Factors and Communicator Factors on Immersion and Viewing Intention: Focusing on e-Sports Game Broadcasting Contents. Korea Game Soc. 2021, 21, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katherine, A.M. User Generated Content versus Advertising: Do Consumers Trust the Word of Others over Advertisers? Elon J. Undergrad. Res. Commun. 2012, 3, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Soh, H.; Reid, L.N.; King, K.W. Measuring Trust in Advertising. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, S.; Li, J. Effects of International Diversity and Product Diversity on the Performance of Multinational Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essardi, N.I.; Mardikaningsih, R.; Darmawan, D. Service Quality, Product Diversity, Store Atmosphere, and Price Perception: Determinants of Purchase Decisions for Consumers at Jumbo Supermarket. J. Mark. Bus. Res. 2022, 2, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, N.; Tarhini, A.; Shah, M.; Madichie, N.O. Going with the Flow: Smart Shopping Malls and Omnichannel Retailing. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 35, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, B.G. The Impact of Qualities of Social Network Service on the Continuance Usage Intention. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 701–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikivi, J.; Tuunainen, V.; Nguyen, D. What Makes Continued Mobile Gaming Enjoyable? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmyer, J.F. Playing Violent Video Games and Desensitization to Violence. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2015, 24, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capasa, L.; Zulauf, K.; Wagner, R. Virtual Reality Experience of Mega Sports Events: A Technology Acceptance Study. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Mun, J.M.; Johnson, K.K.P. Consumer Adoption of Smart In-Store Technology: Assessing the Predictive Value of Attitude versus Beliefs in the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriuchi, E.; Landers, V.M.; Colton, D.; Hair, N. Engagement with Chatbots versus Augmented Reality Interactive Technology in E-Commerce. J. Strateg. Mark. 2021, 29, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghashi, V.; Yuksel, C.A. Interactivity, Inspiration, and Perceived Usefulness! How Retailers’ AR-Apps Improve Consumer Engagement through Flow. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J.-H.; Do, C.; Kim, M. How to Increase Sport Facility Users’ Intention to Use AI Fitness Services: Based on the Technology Adoption Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Li, Y.-C.; Lee, M. Relationship Marketing and Consumer Switching Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, K.-C.; Chen, M.-C. The Impact of Website Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Purchase Intention: Perceived Playfulness and Perceived Flow as Mediators. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2012, 10, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, K.-C.; Kuo, N.-T.; Cheng, Y.-S. The Mediating Effect of Flow Experience on Social Shopping Behavior. Inf. Dev. 2017, 33, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ko, Y.J. The Impact of Virtual Reality (VR) Technology on Sport Spectators’ Flow Experience and Satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, A.; Kim, J.; Ko, Y.J. Symbiotic Relationship between Sport Media Consumption and Spectatorship: The Role of Flow Experience and Hedonic Need Fulfillment. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2018, 7, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Kim, D.; Han, S.; Huang, Y.; Kim, J. How Does Service Environment Enhance Consumer Loyalty in the Sport Fitness Industry? The Role of Servicescape, Cosumption Motivation, Emotional and Flow Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Yang, J. Why Online Consumers Have the Urge to Buy Impulsively: Roles of Serendipity, Trust and Flow Experience. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 3350–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Li, Z.; Mou, J.; Liu, X. Effects of Flow on Young Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention: A Study of e-Servicescape in Hotel Booking Context. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2017, 17, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. How Does Immersion Work in Augmented Reality Games? A User-Centric View of Immersion and Engagement. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1212–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Performance; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.-W.; Gipson, C.; Barnhill, C. Experience of Spectator Flow and Perceived Stadium Atmosphere: Moderating Role of Team Identification. Sport Mark. Q. 2017, 26, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Kim, W.; Lee, A.; Hur, T. Is It Possible to Flow through Watching? Focusing on the Observational Flow and Watching TV. Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2012, 30, 561–587. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Lazarus, R.S. Appraisal Components, Core Relational Themes, and the Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1993, 7, 233–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Choi, H.C. Investigating Tourists’ Fun-Eliciting Process toward Tourism Destination Sites: An Application of Cognitive Appraisal Theory. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The Role of Emotions in Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöblom, M. What Is ESports and Why Do People Watch It? Internet Res. 2017, 27, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, T.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Lu, L.Z. It Is in the Game: Dimensions of Esports Online Spectator Motivation and Development of a Scale. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Oh, E.; Shin, N. An Empirical Investigation of Digital Content Characteristics, Value, and Flow. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2010, 50, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, A.; Djuhana, F.S.P.; Saputri, V.; Moro, A. The Behavioural Intention in E-Sports Spectators: SOR Model Implementation. In Proceedings of the 3rd Asia Pacific International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 13–15 September 2022; pp. 1877–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-Y.; Sung, D.-K. Factors Influencing on the Flow and Satisfaction of YouTube Users. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2018, 18, 660–675. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Wang, R.; Chan-Olmsted, S. Factors Affecting YouTube Influencer Marketing Credibility: A Heuristic-Systematic Model. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2018, 15, 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Examining Mobile Banking User Adoption from the Perspectives of Trust and Flow Experience. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2012, 13, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.-M. What Online Game Spectators Want from Their Twitch Streamers: Flow and Well-Being Perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail El-Adly, M. Shopping Malls Attractiveness: A Segmentation Approach. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 936–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjaningsih, E.; Ningsih, D.H.U.; Utomo, A.P. The Effect of Service Quality and Product Diversity on Customer Loyalty: The Role of Customer Satisfaction and Word of Mouth. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-T.; Wei, C.-H.; Yeh, M.-Y. Controlling Information Flow in Online Information Seeking: The Moderating Effects of Utilitarian and Hedonic Consumers. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Why Do People Watch Others Play Video Games? An Empirical Study on the Motivations of Twitch Users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S. A Contextual Perspective on Consumers’ Perceived Usefulness: The Case of Mobile Online Shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Abdulkarim, H. The Impact of Flow Experience and Personality Type on the Intention to Use Virtual World. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düsenberg, N.B.; de Almeida, V.M.C.; de Amorim, J.G.B. The Influence of Sports Celebrity Credibility on Purchase Intention: The Moderating Effect of Gender and Consumer Sports-Involvement. BBR-Braz. Bus. Rev. 2016, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, J.; Chen, M.-Y.; Wu, Y.-F. Consumers’ Purchasing Intention and Exploratory Buying Behavior Tendency for Wearable Technology: The Moderating Role of Sport Involvement. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Systems Management (IESM), Shanghai, China, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. The Personal Involvement Inventory: Reduction, Revision, and Application to Advertising. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, B. Measuring Purchase-decision Involvement. Psychol. Mark. 1989, 6, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.Y.; Seifried, C. Virtual Interactions and Sports Viewing on Social Live Streaming Platforms: The Role of Co-Creation Experiences, Platform Involvement, and Follow Status. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, S.S.; Camarero, C.; José, R.S. Does Involvement Matter in Online Shopping Satisfaction and Trust? Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, C.; Xie, Q. Something Social, Something Entertaining? How Digital Content Marketing Augments Consumer Experience and Brand Loyalty. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 376–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lin, J.C.-C.; Miao, Y.-F. Why Are People Loyal to Live Stream Channels? The Perspectives of Uses and Gratifications and Media Richness Theories. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, C.; Lim, M.K.; Park, K. E-Smart Health Information Adoption Processes: Central versus Peripheral Route. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 24, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Sanford, C. Influence Processes for Information Technology Acceptance: An Elaboration Likelihood Model. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C. The Influence of E-Banking Service Quality on Customer Loyalty: A Moderated Mediation Approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Byon, K.K. Antecedents and Consequence Associated with Esports Gameplay. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2020, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.W.; Byon, K.K.; Baker, T.A., III; Tsuji, Y. Mediating Effect of Esports Content Live Streaming in the Relationship between Esports Recreational Gameplay and Esports Event Broadcast. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 11, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neus, F.; Nimmermann, F.; Wagner, K.; Schramm-Klein, H. Differences and Similarities in Motivation for Offline and Online ESports Event Consumption. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019; pp. 2458–2467. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, W.; Byon, K.K.; Song, H. Effect of Prior Gameplay Experience on the Relationships between Esports Gameplay Intention and Live Esports Streaming Content. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Ko, Y.J.; Wann, D.L.; Kim, D. Does Spectatorship Increase Happiness? The Energy Perspective. J. Sport Manag. 2017, 31, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevarra, D.A.; Howell, R.T. To Have in Order to Do: Exploring the Effects of Consuming Experiential Products on Well-Being. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.E.; Lee, J.S.; Wann, D.L.L. Delay Effect of Sport Media Consumption on Sport Consumers’ Subjective Weil-Being: Moderating Role of Team Identification. Sport Mark. Q. 2021, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Satici, S.A.; Uysal, R. Well-Being and Problematic Facebook Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Sandvik, E.; Pavot, W. Happiness Is the Frequency, Not the Intensity, of Positive versus Negative Affect. In Assessing Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nix, G.A.; Ryan, R.M.; Manly, J.B.; Deci, E.L. Revitalization through Self-Regulation: The Effects of Autonomous and Controlled Motivation on Happiness and Vitality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 35, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Bernstein, J.H. Vitality; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, R.; Satici, S.A.; Satici, B.; Akin, A. Subjective Vitality as Mediator and Moderator of the Relationship between Life Satisfaction and Subjective Happiness. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2014, 14, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-being. J. Personal. 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon, J.-H.; Jung, S.-O.; Lee, K.-H. Building a Runway to Subjective Happiness: The Role of Fashion Modeling Classes in Promoting Seniors’ Mental Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armbrecht, J.; Andersson, T.D. The Event Experience, Hedonic and Eudaimonic Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being among Sport Event Participants. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2020, 12, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikzentmihaly, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. From Ego Depletion to Vitality: Theory and Findings Concerning the Facilitation of Energy Available to the Self. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, I.A.; Ur Rehman, K. Factors Affecting Consumer Attitudes and Intentions toward User-Generated Product Content on YouTube. Manag. Mark. 2013, 8, 637–654. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.; Moosbrugger, H. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Latent Interaction Effects with the LMS Method. Psychometrika 2000, 65, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed; Pearson Prentice Hall: Uppersaddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T. The Moderating Role of Consumer Characteristics in the Relationship between Website Quality and Perceived Usefulness. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, C.P.; Srinivasan, P.T. Involvement as Moderator of the Relationship between Service Quality and Behavioural Outcomes of Hospital Consumers. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2009, 5, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.R.; Franke, G.R.; Bang, H.-K. Use and Effectiveness of Billboards: Perspectives from Selective-Perception Theory and Retail-Gravity Models. J. Advert. 2006, 35, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J.; Han, I. The Effect of On-Line Consumer Reviews on Consumer Purchasing Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.-J.; Lee, V.-H.; T’ng, S.-T.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Are Online Mobile Gamers Really Happy? On the Suppressor Role of Online Game Addiction. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-C. Relationship between Flow Experience and Subjective Vitality among Older Adults Attending Senior Centres. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.J.; Kwak, D.H.; Jang, E.W.; Lee, J.S.; Asada, A.; Chang, Y.; Kim, D.; Pradhan, S.; Yilmaz, S. Using Experiments in Sport Consumer Behavior Research: A Review and Directions for Future Research. Sport Mark. Q. 2023, 32, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Variable | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | Eigen Values | Variance Explained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entertainment | ENT2 | 0.86 | 52.20 | 20.65 | |||

| ENT3 | 0.88 | ||||||

| ENT4 | 0.64 | ||||||

| Reliability | REL1 | 0.68 | 10.95 | 19.22 | |||

| REL2 | 0.79 | ||||||

| REL3 | 0.78 | ||||||

| Diversity | DIV1 | 0.88 | 8.57 | 19.00 | |||

| DIV2 | 0.74 | ||||||

| DIV3 | 0.78 | ||||||

| Usefulness | USE1 | 0.78 | 5.92 | 18.78 | |||

| USE2 | 0.70 | ||||||

| USE3 | 0.86 | ||||||

| Total variance explained | 77.66 |

| Factors and Items | λ | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entertainment | 0.87 | 0.69 | |

| It is a heart-pounding kind of esports content | 0.86 | ||

| I experience enjoyment when I watch the esports content | 0.84 | ||

| I find the game to be very meaningful | 0.89 | ||

| Reliability | 0.84 | 0.64 | |

| The esports content I have recently experienced is dependable | 0.78 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced is professional | 0.82 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced is accurate | 0.80 | ||

| Diversity | 0.84 | 0.63 | |

| The esports content I have recently experienced is diverse in games | 0.75 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced is rich | 0.80 | ||

| The esports content formats I have recently experienced are varied | 0.83 | ||

| Usefulness | 0.84 | 0.64 | |

| The esports content I have recently experienced helps me become better at esports (games) | 0.79 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced helps me get the related information and knowledge | 0.81 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced helps me to expand my skills in gaming | 0.79 | ||

| Flow experience | 0.97 | 0.78 | |

| (Cognitive Absorption) I was totally focused on the esports game | 0.87 | ||

| (Cognitive Absorption) I was deeply engrossed in the esports game | 0.91 | ||

| (Cognitive Absorption) I was absorbed intensely | 0.89 | ||

| (Time Distortion) It felt like time flew | 0.87 | ||

| (Time Distortion) Time seemed to go by very quickly | 0.89 | ||

| (Enjoyment) It was enjoyable | 0.87 | ||

| (Enjoyment) It was exciting | 0.88 | ||

| (Enjoyment) It was fun | 0.87 | ||

| Happiness | 0.89 | 0.72 | |

| When I think about the esports content viewing experience task, I feel happy | 0.83 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced contributes to your overall life’s happiness | 0.88 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced increase my overall life satisfaction | 0.85 | ||

| Vitality | 0.95 | 0.75 | |

| The esports content I have recently experienced make me feel alive and vital | 0.83 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced make me feel so alive so I just want to burst | 0.86 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced make me have energy and spirit | 0.89 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced make me look forward to each new day | 0.86 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced make me feel alert and awake | 0.88 | ||

| The esports content I have recently experienced make me feel energized right now | 0.88 | ||

| Esports involvement | 0.90 | 0.75 | |

| I have high attention to esports | 0.86 | ||

| Esports are important to me | 0.81 | ||

| I am highly interested in esports | 0.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, C.; Huang, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, K. The Effect of Esports Content Attributes on Viewing Flow and Well-Being: A Focus on the Moderating Effect of Esports Involvement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612207

Yin C, Huang Y, Kim D, Kim K. The Effect of Esports Content Attributes on Viewing Flow and Well-Being: A Focus on the Moderating Effect of Esports Involvement. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612207

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Chaoyu, Yihan Huang, Daehwan Kim, and Kyungun Kim. 2023. "The Effect of Esports Content Attributes on Viewing Flow and Well-Being: A Focus on the Moderating Effect of Esports Involvement" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612207