Abstract

Since the 1970s, large-scale dam construction has become a trend in developing countries. During the 1960–2020 period, 235 large-scale dams were built in Indonesia. However, all of them left a negative socio-economic impact. Explicit strategies to recover project-affected communities’ (PAC’) livelihoods have been implemented but need to be sustained. In 2011, the pumped storage innovation was adopted, and Upper Cisokan, West Java, became the pilot. The recovery of PAC livelihoods is also designed to be sustainable by integrating a “tacit and explicit strategy”. This paper aimed to determine the implementation and impact of this strategic innovation. The research was designed through a survey of 325 PAC families (975 persons) and in-depth interviews with 32 informants. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and dialectics. The result revealed that strategy integration could speed up the post-resettlement livelihood recovery time and collaborate with various local institutions in the academics, businessmen, community, government, media (ABCGM) scheme. In addition, increasing the number of PAC livelihoods by 155 percent and expanding the diversity of livelihoods from agricultural domination to MSMEs and the non-agricultural sector. The involvement of women and youth in livelihood recovery has also increased by 85 percent, especially in micro-, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and the non-agricultural sector.

1. Introduction

North American and European countries built many large dams until 1975, after which both began to abandon most of the installed hydropower due to negative social and environmental impacts. A total of 546 dams were dismantled in the United States from 2006 to 2014, and thousands in Europe [1,2]. This situation contrasted with what is happening in developing countries, which have increased the construction of hydropower dams for decades. Cirata was the first reservoir built by the Government of Indonesia in 1957 and operated in 1967. Very deservedly, during the 1960–2020 period, no less than 235 large-scale dams were built in Indonesia.

Since the 1970s, the construction of hydropower dams has become a trend in developing countries, including Indonesia. As a tropical country with favorable topography and rain patterns, Indonesia continues to make hydropower a critical part of low-emission, renewable, and sustainable energy sources. By 2000, no less than 100 hydropower plants (HP) had been built in Indonesia.

If in the 1960–2000 period, the construction of dams was concentrated on the islands of Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi, then in the 2000–2020 period, it spread to the islands of Bali, West Nusa Tenggara, East Nusa Tenggara, Maluku, and Papua. The Government of Indonesia has planned the construction of 15 large weirs in the 2021–2025 period. Even though all dams were built in modern times (1960–2020), the technology is different. If the reservoirs built during the 20th century (1900–2000) are large, then those built in the 21st century are relatively small.

Weirs were designed to be relatively small due to pumped storage (PS) innovations. PS is the only utility-scale electricity storage technology widely adopted worldwide, especially in developed regions [1,2]. One of the leading technologies of PS is the design and manufacture of reciprocating pump-turbine runners. Until 2018, PS remained the dominant large-scale energy storage source (96 percent) of global energy capacity [3]. PS is seen as climate-adaptive and prospective, as it becomes an integral part of the power grid to increase stability, elasticity, efficiency, and sustainable-energy penetration [4].

Upper Cisokan Pumped Storage (UCPS) is one of the first modern dams in Indonesia that is small in size but produces enormous power. UCPS is like a giant battery that can store 1040 megawatts of electricity. This battery capacity is the largest power plant in Indonesia because it outperforms the Cirata HP, which only produces 1008 megawatts of power. UCPS has the first power system using pumped storage technology in Indonesia. This power system is a dam innovation that makes HP function as “power storage”. Besides being very efficient, it is also reliable to activate, especially during peak-load conditions.

UCPS is a pumped storage (PS) constructed by two dams, consisting of an upper pool and a lower pool. During peak-load times, the lower pond water will be pumped into the upper pond, and during peak-load times, the upper pool water will be released to drive the turbine. UCPS, with this system, is the first to be implemented in Indonesia. UCPS works to store energy when the base load reaches off-peak to provide reliable capacity at peak load by pumping water from the downstream reservoir to the upstream reservoir as energy storage [1,5].

The capacity was a manageable size but was designed to generate immense energy. UCPS was built on the Cisokan River, a tributary of the Citarum River in West Java. The construction of UCPS required a total land area of 668.31 hectares, which divides the two districts, 522.64 hectares in Kab. West Bandung and 145.67 hectares in Reg. Cianjur. Land Acquisition and Resettlement Operations (LARAP) for project-affected communities began in 2011 and were completed in 2013. This project includes land acquisition for access to locations and biodiversity protection areas.

Through technological innovation, “pump storage (PS)”, UCPS did not need land and water on a large scale. In addition, it also did not consume many puddles. The advantage is that weirs can be built on large rivers with large discharges and capacities but have the opportunity to be developed on medium-scale rivers and tributaries [6]. Weirs are built in stages, upper and lower. Both are used to hold water and drive turbines. The difference is that water from the lower will be pulled back to the upper at night by using excess electrical energy, which will be reused to drive turbines [7,8].

PS technology is expected to be a solution to problems arising from the construction of large-scale conventional dams, such as deforestation, degradation of aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity, increased emission of greenhouse gases, displacement of thousands of people’s settlements, conversion of agricultural land, and the loss of people’s livelihoods due to hit by the project. Furthermore, it can minimize the impact of damage to social systems, environmental systems, and loss of livelihoods for local communities [9]. With that, livelihoods and sources of income for the community are sustainable.

The relatively small scale of UCPS can minimize adverse social, economic, and environmental impacts, thereby saving on the cost of building a weir [10]. In contrast, the construction of large dams is often oriented towards providing energy for industrial and urban population growth while paying little attention to socio-economic and environmental impacts [11]. The irony is that people affected by projects often do not get electricity because they do not get services from large dams. Whoever agrees that all countries need sustainable energy should accept that HP is part of this portfolio.

Ideally, innovative and sustainable solutions are also created to solve the problem of the negative impacts of dam construction, primarily related to the recovery of livelihoods and incomes of project-affected communities (PAC). PAC lost their homeland and long-standing livelihoods and businesses [12]. It is challenging for PAC to find a new livelihood in a new settlement location, so they choose migration. Few PAC had lost their resources and livelihoods because they need help managing compensation money. Their livelihood status has decreased from owner to laborer in the rural informal sector [12,13].

In real terms, the project manager always works with stakeholders to recover the livelihood and income of the PAC. However, often the operations are carried out top-down and instantaneously, so it is unsustainable and even fails. Therefore, a circular and sustainable community livelihood and income recovery design are needed, integrating strategies designed from the outside (explicit strategy) with PAC adaptation strategies (tacit strategy). Through this strategy, PAC livelihoods can recover through this strategy, and negative social, economic, and environmental externalities from UCPS can be reduced or even eliminated [14,15,16,17,18]. An integrative PAC livelihood recovery solution pays attention to sustainability and diversity and anticipates the impacts of climate change and other risks [19,20]. This strategy included meeting the needs of food, clean water, energy, and others. Livelihood recovery must anticipate the loss of resources, habitat, biodiversity, irrigation networks, infrastructure, and access to services [21]. An integrative strategy is essential to reduce PAC’s environmental and social costs. This paper aimed to identify the integration of tacit and explicit strategies in collaborative, circular, and sustainable PAC UCPS livelihood recovery.

The livelihood recovery of PAC in PS and UPCS is designed to be sustainable through explicit integration with a tacit strategy based on a sustainable livelihood theory using a pluralistic method. This method has been successfully applied in creative communities in China, Taiwan, India, Great Britain, Scotland, and Korea [22]. Integrated strategies have been proven to recover and grow PAC livelihoods, strengthen access to resources, and reduce negative social, economic, and environmental externalities [8,14,16,17,22,23].

Tacit and explicit strategy is an approach or method derived from knowledge management theory, which is developed by integrating and synergizing knowledge or livelihood restoration innovations from the project manager (explicit) with those from the PAC community (tacit). The integration is used by the authors in the sustainable livelihood approach (SLA) on the UCPS PAC. The results of the review revealed that the integration of tacit and explicit strategy in PS, which is relatively small in scale, is proven to be able to minimize negative social, economic, and environmental impacts [8,10,24] so that it contrasts with the construction of large-scale dams [25].

Integrative tacit and explicit strategies on PAC livelihood recovery solution paid attention to sustainability and diversity and anticipates the impacts of climate change and other risks [20]. This strategy included meeting the needs of food, clean water, energy, and others. Livelihood recovery must anticipate the loss of resources, habitat, biodiversity, irrigation networks, infrastructure, and access to services [21]. An integrative strategy is essential to reduce PAC’ environmental and social costs. The integration of tacit and explicit strategy as an approach to recover the sustainable livelihoods of PAC UCPS. The reason is that the PAC livelihood recovery approach for large-scale hydropower has been dominated by an “explicit strategy” or a top-down (supply-driven) approach. The implication is that not only is it slow to recover old livelihoods and does not generate new livelihoods, but it has also made PAC dependent, making it unsustainable. This paper aimed to identify the integration of tacit and explicit strategies in collaborative, circular, and sustainable PAC UCPS livelihood recovery based on the perspective of the theory of sustainable livelihood. In general, this paper aims to find out the implementation of the pluralistic method, tacit strategy, and explicit strategy and the impact of the integration of tacit and explicit strategy on the recovery of PAC livelihoods based on the theoretical perspective of sustainable livelihood (SL) and the roles of men and women (gender) in it.

2. Theoretical Background

Sustainable livelihoods (SLs) are still a hot debate and a development issue continuously discussed in the various literature and scientific forums for the last two decades [26]. It has capacity, tangible or intangible assets, and activities needed in building life. A livelihood is called sustainable if it is adaptive, continues under various pressures, maintains and increases capacity and assets owned, and regenerates [27]. This SL framework focuses on integrated and people-centered rural development, both households and communities [28]. The analysis explains how a person builds life and manages capital that supports increased welfare. The analysis principle is integrative, participatory, and collaborative, focusing on local (tacit) and external (explicit) strategies. The analytical framework refers to human, social, natural, economic (financial), and physical-ecological capital, including transportation, water, energy, and production inputs [29].

The process of realizing sustainable livelihoods requires a pluralistic approach to empowerment. This method integrated rapid rural appraisal (RRA), cyber extension (CE), community development (CD), community-driven development (CDD), participatory rural appraisal (PRA), participatory learning action (PLA), participatory action research (PAR), market information system (MIS), knowledge sharing (KS), community coaching (CC), disaster management and mitigation (DMM), integrated security system (ISS), and others. Tacit strategy is interpreted as the efforts made by internal personal and communal parties, both in the form of initiatives, adaptation, coping, and mitigation [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The nature of the tacit strategy approach is internalization so that it is rooted within, including from outside networks. The practice prioritizes initiative, mutual trust, sharing, collaborating, and involving all parties.

Explicit strategy is a formal effort by external parties to initiate, strengthen, protect, innovate, and develop personal and community livelihoods. It can include assistance (facilitation), capital assistance, strengthening awareness and participation, and increasing access and capacity. Capital assistance is realized through social, economic, natural, and human capital [35]. Some livelihood experts include political capital [26] and knowledge capital [37]. An integrated strategy is interpreted as a community development approach that is carried out by integrating an explicit strategy designed by various external parties (supply-driven) with a tacit strategy initiated from below by the community (demand-driven). This strategy develops a participatory approach whose analysis only reaches the output and outcome by adding impact and feedback. This strategy is constructed with knowledge management theory from [37], disruptive theory from [29], sustainability theory from [38], and community development theory.

3. Materials and Methods

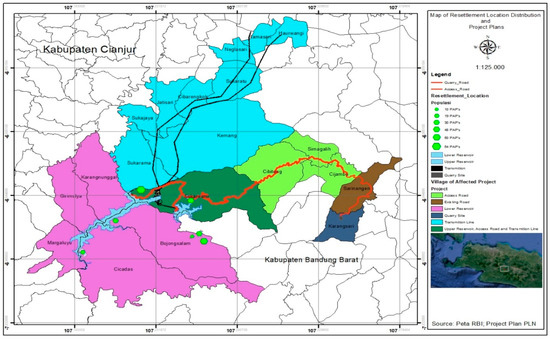

This study uses an integrated design (mixed method), with a quantitative dominant and less qualitative [39]. The best way to obtain reliable knowledge of different population groups is to combine quantitative and qualitative insights [40,41]. For this reason, many methods were used: literature reviews, structured surveys using validated questionnaires, participatory observation, in-depth interviews using guidance interviews, and focused discussions. The research was conducted at UCPS, West Java Province (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research locations in West Bandung and Cianjur Regencies, West Java, Indonesia.

The population in this study numbered 2172 households, according to the 2013 LARAP report. Of these, around 623 households moved outside the UCPS location, and 1549 households remained in the location with residences spread across five points, namely the upper dam, lower dam, access road, new infrastructure, transmission lines, and resettlement sites [41]. Based on the initial population [41] and using a sampling technique of 15 percent of the total population, 325 families were taken as respondents. Of these, 52 families came from Cipongkor District and 230 families from Rongga District, West Bandung Regency, while 43 families came from Campaka District, Cianjur Regency.

A total of 32 informants were chosen deliberately, with details of 1 representative from MDU and PIU and six representatives from the West Bandung and Cianjur Regency governments handling PACs’ economic recovery. Then, 4 sub-district representatives, 6 village managers, 2 local security officers, 4 PAC cooperative administrators, 2 community empowerment people, 1 banking administrator, and 1 PT representative were selected. In addition, Perhutani, 2 farmer group administrators, 2 MSME group administrators, and one consultant for PAC economic recovery were also included. Apart from being interviewed, the informants were also involved in the FGD.

Primary data were obtained from the survey, tabulated, diagrams made, and analyzed descriptively using outcome mapping to deal with integrative strategy impact analysis and multi-dimensional scaling to analyze livelihood recovery sustainability. Primary data obtained from in-depth interviews, observations, and focused discussions were selected, explicitly presented in the form of inboxes, and analyzed dialectically. In addition, the qualitative data were analyzed by trialectics and trend analysis to review the implementation of PAC economic recovery for ten years (2013–2022), which was also presented in addition to primary data. The results were justified through three steps: first, theoretical analysis, ethical, emic, and dialectical; second, through consultation with experts or reviews; and third, through public consultation with research participants. The research was conducted for one year, starting from August 2021 to August 2022. The third steps are compiled and mapped based on the results of in-depth interviews, focused discussions (FGD), and a review of the LARAP implementation documents from 2011 to 2022. The author compiled these phases using community empowerment stages adopted from community development theory [42] and pluralistic methods [22]. Five stages of empowerment are used as a framework for preparing these phases: enabling, strengthening, advocation, innovation, and improvement.

4. Results

An integrated strategy is defined as tactical efforts to recover PAC livelihoods carried out by integrating an “explicit strategy” designed by various UPCS project organizers (top-down) with a “tacit strategy” initiated from the bottom (bottom-up) by the PAC. The integrated strategy is the development of a demand-driven participatory strategy by adding the concepts of sharing, collaborating, applicable, and sustainable concepts.

4.1. Implementation of Pluralistic Method of PAC Livelihood Recovery

The explicit method of recovery the livelihood of PAC is implemented through the pluralistic method based on the theory of community development [15,21,43,44]. There were five assistance phases:

The first phase (2011–2012) consisted of facilitation of identification of business interests as a basis for grouping PAC and business training for pilot groups. The training focuses on agriculture, animal husbandry, forestry, fishery, product processing, construction labor, trading business, and management of economic institutions. Apart from that, a stakeholder analysis was also carried out for the implementation of community involvement and development (CID).

The second phase (2013–2014) is entrepreneurship training, preparation of business plans, and strengthening PAC access to capital services. The training focused on the effectiveness and efficiency of using compensation money, developing sheep farming, fish farming, honey bee farming, banana chip, and palm sugar businesses. Training is given to farmer groups, small businesses, and female farmers. The training continued strengthening PACs’ access to health services, markets, clean water, secondary and senior education, transportation, information, and the internet.

The third phase (2015–2017) facilitated the strengthening of three PAC cooperatives, two agricultural MFIs (86 members of families), one livestock microfinance institution (MI) (25 members of families), and one entrepreneurial MI (54 members of families). The priority was the effectiveness of the realization of venture capital assistance (IDR 7.5 million/HF) and the growth of new businesses. Capital assistance is focused on agro-complex-based micro-businesses, inputs (seeds, fish/plant/livestock seeds, tractors), compost, and food processing. Capital reinforcement was given to the men’s group for agro-complex, while processing and handicrafts were given to the women’s farming group.

The fourth phase (2018–2022) is strengthening community access to productive resources, especially infrastructure and socio-economic support facilities. Around 56 related programs were implemented, thereby increasing the quality and quantity of district roads, village roads, neighborhood roads, bridges, irrigation networks, clean-water networks, worship facilities, health facilities, refueling facilities, energy service facilities (gas), and biodiversity protection facilities. As a result, there was business chain efficiency and the expansion of the PAC communication network, so access and income increased.

The fifth phase (2021–2022) is strengthening business networks through structuring superior product business documentation, business administration (labeling, barcodes), and online marketing. The focus is on locally processed food products, such as banana chips, palm sugar, honey, black rice, and brown rice. The galleries and websites were developed and marketed through district and regional exhibitions to expand the market for processed food and handicrafts made of wood or bamboo. PAC business group product branding is also carried out through social media including Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.

4.2. PAC Livelihood Recovery Explicit Strategy

An explicit livelihood recovery strategy was interpreted as a formal effort by external parties to initiate, strengthen, protect, innovate, and develop PAC. The concrete strategy includes Government social programs, institutional action plans, corporate social responsibility, NGO empowerment programs, community service for higher education institutions, social action programs for research institutions, socio-economic media awareness, and innovation adoption from extension workers. The strategy takes the form of assistance (explicit method) and capital assistance. Capital assistance is realized through social, economic, natural, and human capital [35]. Some livelihood experts include political capital [26] and knowledge capital [37].

4.3. PAC Livelihood Recovery Tacit Strategy

The tacit strategy for recovery the PAC’s livelihood is interpreted as the efforts made by the internal PAC, both personally and communally. The concrete strategies are in the form of initiatives, adaptation, coping, and mitigation [22,33,35,36,45]. Livelihoods are grown in the PAC ecosystem through diversification, differentiation, intensification, and substitution patterns. The nature of the tacit strategy approach is internalization, which is rooted in and extends to external networks. The practice emphasizes initiative, mutual trust, sharing, collaborating, and involving all parties (participatory combination).

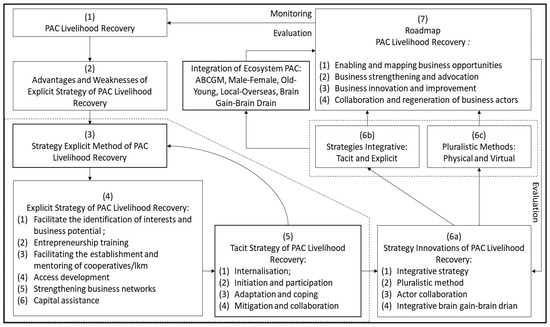

4.4. Integration Scheme PAC Livelihood Recovery Tacit–Explicit Strategy

An integrated strategy is a tactical effort to recover PAC livelihoods by integrating an explicit strategy designed by various UPCS project organizers (supply-driven) with a tacit strategy initiated from below by the PAC community (demand-driven). The integrated strategy is a PAC livelihood recovery approach that is not only participatory but also systemic, holistic, and collaborative. It combines several empowerment approaches, integrating potential capital and collaborating with various related parties (stakeholders), including the project side (UPCS), the government, and the community. The scheme is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The PAC livelihood recovery integration tacit–explicit method strategy.

4.5. Impact of Explicit and Tacit Integration Strategy for PAC Livelihood Recovery

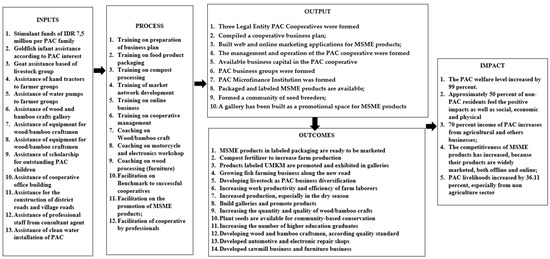

The work of most PAC prior to the existence of the project were rice farmers, crop farmers, forestry land cultivators, farm laborers, and agricultural product traders. After the project started, the number of crop farmers increased, while rice farmers decreased by 40 percent, and forest cultivators decreased by 50 percent. The number of land-owning farmers increased from 41 percent to 63.90 percent. Meanwhile, cultivators fell from 13.70 percent to 8.4 percent (p < 0.05). Sharecroppers and farm laborers declined because they switched to non-agricultural jobs. At the beginning of the project, the number of farmers decreased but increased again after the recovery program. Figure 3 explained how tacit and explicit strategy integration can be sustainable in PAC livelihood recovery and it is implementative.

Figure 3.

Impact of tacit and explicit strategy integration in PAC livelihood recovery.

4.6. Gender Perspective in PAC Livelihood Recovery

Gender analysis is included because explicit and tacit strategies differ in giving space to men and women, including husbands, wives, sons, and daughters. Concerning economic recovery, the explicit strategy focuses more on the husband and wife as heads of the household. Meanwhile, the tacit strategy gives more space to the younger generation of PAC, both men and women. Therefore, integrating the two strategies can strengthen the realization of the SDGs, related to faster economic growth and reducing social inequality and environmental degradation [27,46,47,48]. Refs. [29,49] emphasized that collective, collaborative, and integrative models offer different preferences.

4.7. Constraint and Expectations for PAC Livelihood Recovery

Reconstructing PAC from a business dominated initially by rice farming to cultivating crops and businesses in various sectors takes work. More than financial and economic capital, human and social capital are needed. If measured from the development of PAC business empowerment, it is already at the strengthening and advocation stage. Assistants, institutions, and empowered actors until this stage faced technical and non-technical obstacles. The obstacles were such as the scattering of new PAC settlements (82 percent), the need for more professional human resources in business management (78 percent), PAC still focused on restoring their respective livelihoods (65 percent), and so on. In real terms, various tacit and explicit efforts have been made by all parties to maintain business continuity, but the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) destroyed everything.

5. Discussion

The survey results, in-depth interviews, and FGD have been presented in pictures and quotations. The mapping of the pluralistic method of livelihood recovery was constructed from the results of in-depth interviews, FGDs, and secondary data, including the results of trialectics. Tacit and explicit strategy in livelihood recovery was constructed from surveys, FGDs, and in-depth interviews. The impact of sustainable livelihood restoration is constructed from surveys, in-depth interviews, and FGDs. Gender perspectives and obstacles in implementing integrated strategies are constructed from surveys, in-depth interviews, and FGDs.

The novelty of this paper integrates not only six explicit strategies with four tacit strategies for restoring PAC livelihoods but also the integration of offline and online communication and empowerment methods, integration of collaborating actors (academicians, researchers, government, business people, media, and communities), as well as integration of PAC living overseas with those returning to rural areas (brain drain and brain gain actors). Also, the importance of a conducive PAC ecosystem in realizing a roadmap for sustainable livelihood recovery would enable, and map opportunities, strengthen and protect businesses, innovation, business improvement, and collaboration and regeneration of people in business or entrepreneurs is assessed (Figure 1).

5.1. PAC Livelihood Recovery Explicit Method

The synthesis was “the first phase is still enabling, related to the appropriateness of compensation and the effectiveness and efficiency of its utilization (Table 1). The second phase is strengthening and advocating the PAC economy through strengthening entrepreneurial capacity (training, mentoring), strengthening business capital, strengthening business support services through infrastructure development (access to resources), and strengthening business institutions. The third phase is business innovation, and the fourth and fifth phases are the development of PAC business networks (improvement), business and market added value” [50,51,52,53].

Table 1.

Implementation, outputs, and outcomes of PAC livelihood recovery strategy.

5.2. PAC Livelihood Recovery Explicit Strategy

An explicit livelihood recovery strategy is interpreted as a formal effort made by external parties to initiate, strengthen, protect, innovate, and develop PAC (Table 1). The concrete strategy included government social programs, institutional action plans, corporate social responsibility, NGO empowerment programs, community service for higher education institutions, social action programs for research institutions, socio-economic media awareness, and innovation adoption from extension workers. The strategy takes the form of assistance (explicit method) and capital assistance. Capital assistance is realized through social, economic, natural, and human capital [35]. Some livelihood experts include political capital [26] and knowledge capital [37].

Explicitly, the PAC UCPS livelihood recovery strategy by the authorities has been outlined in the LARAP document. As the holder of authority, Main Development Unit (MDU)—under the World Bank’s supervision—had realized the rights of PAC. The rights were from compensation, relocation, and resettlement (natural capital) to recovery of livelihoods through the development of supporting infrastructure, economic capital assistance, strengthening human capital, establishing cooperatives and financial institutions, and micro (social capital). These actions were carried out in stages according to the needs level that the implementing team had mapped out since 2013. The recovery of the PACs’ livelihoods was carried out after resettlement, so it is more focused.

If we count until 2022, efforts to recover PAC livelihoods will take nine years. The process is complicated because PAC resettlement is not localized at one point. In real terms, relocation sites have been prepared and offered to PAC, but 71 percent of PAC prefer to move to their preferred location in the surrounding area, and 29 percent even moved to other sub-districts and regencies in West Java. For some PAC, the culture of field farming and other new businesses cannot immediately replace the loss of their old livelihoods and their productive resources, especially rice farming and paddy fields. Some PAC develop human rice to meet their food needs, while others persist in lowland rice farming by buying paddy fields in other areas.

In 2019, human capital capacity was strengthened through two approaches: first, developing the personal and family capacities of PAC, and second, capacity building for PAC institutional managers, especially for PAC managers and PAC cooperatives. The capacity-building activities vary, ranging from training, capital assistance, assistance from experts, counseling, comparative studies, etc. (Table 1). In general, more activities were carried out at the upper dam and new road than at the lower dam. Capacity building is carried out by specialists, facilitators, consulting agents, and technical assistants. The strengthening of human capital has been carried out in the first phase (2010–2014), while the second phase (2015–2020) focuses on institutions (social capital).

PACs’ human and social capital has been strengthened in all locations based on business interests and potential. However, it is still temporary and has a pilot group bias. The implication was that not all PAC households had the opportunity to participate in these activities. Informant E (52 years old, reference extension worker) emphasized: “The community needs ongoing assistance. Therefore, the basic framework must be expanded from just mapping interest to practice in the field so that PAC can be grouped based on their field and capacity conditions, which needs to be initiated, strengthened, protected, innovated, developed, and engineered. With that, assistance will be more effective and efficient”.

As a new economic institution that is an explicit strategy product, ideally, PAC cooperatives can accelerate the recovery of PAC livelihoods. Cooperative A, which has 283 household members and a capital of IDR 2.1 billion, and Cooperative B, which has 200 families and a capital of IDR 1.5 billion, have only been able to roll out 30 percent of their business capital in savings and loans. Cooperative C with 194 households and a capital of IDR 1.4 billion has only been able to roll out 35 percent of its capital in savings and loans, necessities, and animal feed distribution. Cooperative C is relatively livelier because it has a professional chairman [23], emphasized that quality human capital, social capital, natural capital, and financial capital are enough to recover livelihoods.

Informant G (52 years old, MSME office representative) said Cooperative C is more developed than Cooperatives A and B because an experienced MSME business consultant led it. A business consultant confirms that human capital assistance ranks first in livelihood recovery [54]. Since 2017, cooperative C has owned various businesses and operational vehicles. However, the COVID-19 pandemic killed all of that in 2020–2022. The implication is that the cooperative suffers losses, and the chairman resigns. Now Cooperative C has to start a business from scratch with new management who are very careful in managing business capital.

According to Informant D (46 years old, reference NGOs), PAC cooperatives were challenging to develop because the management needs to be more professional. No one has experience managing cooperatives. Assistance has existed, but temporary. Efforts to increase the capacity of PAC management and PAC cooperatives have been carried out through training and visits to cooperatives. However, they have not had much impact because prospective managers and administrators have not had apprenticeships. Ideally, as a process, strengthening social capital flows from the enabling, strengthening, advocation, innovation, and improvement stages [54,55,56,57].

Livelihood recovery carried out by external parties (explicit) is biased towards jobs and general businesses, such as farming, livestock business, and agriculture-based MSMEs. The implication is that the PAC group of young men and women needs to be accommodated, even though they occupy a dominant position (38 percent) in the rural demographic structure [58]. In real terms, the assistance provided during the 2014–2020 period has successfully recovered the livelihoods of PAC engaged in the agro-complex sector. These conditions have encouraged PAC groups not engaged in the agricultural sector to implement tacit strategies to recover their livelihoods through adaptation, creation, coping, or mitigation. Some of the actions were carried out individually or collectively [59].

5.3. PAC Livelihood Recovery Tacit Strategy

The tacit strategy for restoring the PAC’s livelihood is interpreted as the efforts made by the internal PAC, both personally and communally, to recover their livelihoods (Figure 2). The concrete strategies are in the form of initiatives, adaptation, coping, and mitigation [30,31,35,36,60,61] and empowering [62]. Livelihoods are grown in the PAC ecosystem through diversification, differentiation, intensification, and substitution patterns. The nature of the tacit strategy approach is internalization, which is rooted in and extends to external networks. The practice prioritizes initiative, mutual trust, sharing, collaborating, and involving all parties (participatory combination).

Tacit strategies are created and innovated by PAC families and communities through sharing and collaborating mechanisms, both in physical and virtual communities. Critical dialogue is also carried out within family, community, and village business networks. The motor is the PAC, which is young, educated, skilled, and well-networked. So far, they have yet to be accommodated in an explicit strategy. They are the ones who initiate the formation of social dialogue space in social media. They bridge and bond between PAC living in rural areas and villagers living in urban areas and abroad. The tacit strategy is carried out simultaneously with the implementation of the explicit strategy (Figure 2), both offline and online so that physical distance and social distance are not limited. Ideas, experience, capital, networks, and new business opportunities grow through an integrated space for sharing and collaborating.

As a result, if the explicit strategy only grows 11 PAC livelihoods, then with the tacit and explicit integration, 26 types of new businesses will grow (155 percent). If the explicit strategy is biased towards the agricultural, livestock, fishery, forestry, and MSME sectors, then the tacit strategy involves many sectors. In general, three sectors are the focus of the tacit strategy. First, the trade sector that grows rice stalls, basic food stalls, mobile traders, collectors and commodity dealers, grocery stores, building materials stores, electronics shops, book and stationery shops, photocopiers, cellphone counters, credit/quota distributors, gas distributors, distributors BBM, seed distributors, and others.

Second, the transportation and communication sector grew the business of village public transportation, goods transportation, delivery services, motorcycle taxis, drivers, etc. Third, the industrial sector grows convection, rice milling, sawmills, vehicle repair shops, wood and furniture processing, bamboo processing, sand mining, factory workers, banana chip home industry, palm sugar home industry, woven bamboo home industry, honey bee business, seed-based community, and others. The agricultural industry was also developed, such as the packaging of black rice and red rice and the processing of spice plants. Tourism has been discussed but has yet to be developed.

The results of field observations confirm that the lives and livelihoods of PAC were now better and more diverse than before. After the implementation of the compensation and the improved access of PAC to various productive resources, many entrepreneurial activities were born at the project site and new settlement locations. PAC do not only create jobs and new entrepreneurs for PAC but also for non-PAC residents. In fact, with the opening of new roads and improved village roads at the project site, the livelihoods of PAC and residents, generally, have become more expansive, including from outside the rural area.

Spatially, most (66.10 percent) of the PAC in the upper dam work in the non-agricultural sector, as well as those in the lower dam (64.71 percent) and on new roads (71.05 percent). Generally, they switch from agriculture to craftsmen (convection), small-scale agro-industry, private employees, construction workers, traders, drivers, services, etc. Some (2 percent) are still migrant workers in the Middle East. There is also about three percent of those in PAC who are civil servants. Since transportation access has improved, the livelihoods of PAC have become very diverse. The potential for creating new livelihoods is still open, even though the level of competition with newcomers is getting higher.

Informant E (a 33-year-old youth leader) revealed, compared to other new businesses, seed and furniture are the most prospective. Besides being supported by biological resources from community forests and agroforestry, market demand is also increasing. Wood from the community forest is processed into building materials and made into handicrafts, couches, tables, chairs, bookshelves, furniture shelves, and others. The market for handcrafted wood is relatively easy in secondary preparations (poles, boards, rafters) and are also accommodated by building and furniture shops. Meanwhile, partners in urban areas accommodate tertiary and quarter preparations (furniture, furniture).

Entrepreneurs trading, transportation, carpentry, and stalls are the most dominant, in addition to processing agricultural and forestry products. Suppose the business assistance to increase the added value of local-specific commodities is carried out sustainably, and the PAC capital assistance managed by the PAC cooperative is productive; in that case, more new livelihoods will be created for the PAC and their generation. If the construction of public facilities, including roads, bridges, irrigation, information networks, education, and health services, is realized in all locations, a wider new livelihood will be created, encouraging some of those in the PAC to seek livelihood outside the UCPS area.

In fact, after improving access to roads and transportation, around 15.60 percent of those in the PAC migrated to cities and abroad, especially young people. On the positive side, PAC livelihoods are becoming more numerous and varied. There are couriers, drivers, household assistants (HA), entrepreneurs, traders, laborers, private employees, and even migrant workers. As a result, the income of the PAC has improved, and the number of PAC generations who have graduated from high school and tertiary institutions has increased. Being the IW was seen as promising but is starting to be abandoned because the wage value is equivalent to entrepreneurship. Therefore, working and doing business in the country is an option.

Informant W (50 years old, university representative) emphasized that infrastructure development has increased the PAC’s access to markets, land, roads, transportation (transportation), information, terminals, surrounding villages, and to cities. The PAC’s access to markets for agricultural, livestock, and forestry products has increased significantly. If the PAC previously sold its products to middlemen, now they can directly access strategic markets in the provincial capital and its surroundings. The farming community does not only sell fresh but also processed products. However, improved roads and transportation have also increased the flow of people and natural resources out of the countryside (capital drain).

Improved transportation infrastructure has facilitated the mobility of PAC and rural communities to urban areas, thus attracting investors, business people, traders, distributors, and others to come, transact, and invest in the project area. Thus, new business clusters include minimarkets, gas stations, LPG agents, building materials agents, etc. Informant W (50 years old, village government reference) emphasized that when access to productive resources improves, new job and business opportunities are created. The livelihoods of the PAC and the community, in general, are becoming more open. The problem is that these new livelihood opportunities are not anticipated in the explicit strategy but appear in the tacit strategy.

One thing that must be considered in measuring the development of PAC livelihoods is that the expected livelihoods are sustainable. The development of the PAC’s livelihoods is explicitly biased towards a short-term approach, while the long-term livelihoods of its generation should be given more attention. In addition, the recovery of PAC livelihoods is also very, very biased towards farming which depends on the rainy season. PAC requires alternative businesses that are anticipatory against the risk of loss of livelihood in the dry season, including loss of food sources, especially rice.

In real terms, opportunities to create new livelihoods to grow with a tacit strategy are still wide open, including in the tourism, creative economy, logistics, and agro-industry sectors. Strengthening PACs’ access to business networks and productive resources, especially transportation, markets, finance, health, education, information, production inputs, and energy, allows collaboration with ABCGM to be created. If, by 2022 alone, 81 percent of new PAC entrepreneurs have grown from the tacit strategy, then if it is integrated with the explicit strategy, it can grow even higher. Suppose initially entrepreneurship was dominated by the production of agricultural commodities (40 percent), essential food services (32 percent), and trading businesses (22 percent); then, in the future, in that case, it will develop into businesses to increase added value, logistics services, agro-ecotourism, tourism villages, crafts, online services, etc.

5.4. Impact of Explicit and Tacit Integration Strategy for PAC Livelihood Recovery

In general, most of the PAC’ jobs before the project were rice farmers, crop farmers, forestry land cultivators, agricultural laborers, and traders of agricultural products. After the project started, the number of crop farmers increased, while rice farmers decreased by 40 percent, and forest cultivators decreased by 50 percent. The number of land-owning farmers increased from 41 percent to 63.90 percent. Meanwhile, cultivators fell from 13.70 percent to 8.4 percent (p < 0.05). Sharecroppers and farm laborers declined because they switched to non-agricultural jobs. At the beginning of the project, the number of farmers decreased but increased again after the recovery program.

After compensation was realized in 2012–2016, the PAC income level per capita per month increased by 71.33 percent, while around 28.67 percent tends to be constant and decrease (p < 0.05). The highest increase was felt by 84.75 percent of the PAC living in the upper reservoir, while a significant decrease was experienced by 35.09 percent of the PAC along the new road and lower dam. In general, landowners and cultivators in all locations experienced an increase in income per capita per month. If, before UCPS, around 88.24 percent of PAC income was less than IDR 2.5 million/capita/month, then after that, it decreased by around 52.33 percent (p < 0.05) (Table A1).

In 2017–2019, the number of PAC with revenues of more than IDR 2.5 million continued to increase. There are five additional sources of income earned by PAC: First, additional business capital from family members who work in urban areas, whether to open stalls, repair shops, gas distributors, or retail motor vehicle fuel. Second, being a construction worker for quite a long time. Third, additional income from the wife, who opens a stall, and from the son, who works as a motorcycle taxi driver, transportation driver, and a convection business. Fourth, additional income from the wife’s business processes food, wood, and bamboo into various crafts.

In general, the income of those in PAC who own land has increased in the 2012–2022 period due to receiving compensation, increased land prices, or increased prices for agricultural production. In contrast, the decline occurred in the farmers cultivating the land at the lower dam because they lost their cultivated land and did not receive much compensation money. However, in 2019, they were permitted to work on Perhutani land in a new location, so their income increased again. Strictly speaking, the livelihood of PAC has improved after compensation, resettlement, and transportation have improved, and they are open to the outside world.

If before UCPS the income of the WTP came from livelihoods as farmers, cultivators, farm laborers, middlemen, and laborers transporting agricultural products, now it is more diverse. If previously PAC households received more income from husbands, now it comes from wives and working-age household members. If previously 88.24 percent of PAC households had an income of less than IDR 2.5 million/month, now 53 percent have more than the regional minimum wage (IDR 3.2 million/month). The increase occurred due to additional income from all family members working in the non-agricultural sector (p < 0.05) Table A1).

Techno-economically, the existence of UCPS offers many job and business opportunities. The knowledge and skills of PAC are much richer than before (78.38 percent). PAC access to business capital, working capital, natural capital (land, seeds, seedlings), technology capital, and information capital is much higher (82.25 percent). However, PACs’ social capital is still in the weak category (43 percent), including its trusting relationship with outsiders who enter the area. Business and work opportunities for PAC are still wide open, but they have yet to be realized (Table 1).

Specifically, the impact of the explicit method on the livelihood recovery of PAC is still tiny (36.11 percent). Regardless, these efforts have created many new livelihoods, both on-farm sub-systems (such as agriculture, animal husbandry, fisheries, and forestry), off-farm (such as sawmills, wood or furniture crafts, banana processing, and palm sugar processing), and non-farm (such as stalls, workshops, fuel retailers, transportation, and trading). However, the explicit method also has negative impacts on PAC behavior, such as dependence on capital assistance (25 percent), consumptive behavior in utilizing capital assistance (25 percent), and negative perceptions of cooperative managers and assistants (50 percent). The authors of [63] reviewed 203 case studies related to the explicit method, revealing that only physical impacts improved, while natural, social, financial, human, and cultural capital impacts suffered severely.

Informant G (49 years old, reference of NGOs) revealed: “there are several the negative impact of explicit strategies on PAC behavior, such as dependence on cash or in-kind assistance, wanting to get instant capital assistance, viewing the rigid mechanisms applied by groups and cooperatives, being reluctant to learn how to make business plans, spending venture capital assistance on things unproductive and so on”. The behavior of the assistants who did not follow the SOP also emerged. All of this has fueled the growth of mutual suspicion, distrust, and negative perceptions of some PAC towards MFI management and cooperatives if it creates conflict, members’ accusations, and jealousy of cooperative managers and PAC who have succeeded in developing productive economic throughout entrepreneurship.

The lack of an explicit strategy has increased the adaptability of the PAC to create new livelihoods from various opportunities and limitations that come from outside. Strictly speaking, limitations have fostered community creativity and innovation in creating new sources of income and business fields, strengthening the access of the PAC to various productive resources, such as basic food needs, raw materials, markets, information, transportation, and capital. This has then fostered a planned business culture (such as preparing business plans and drafting business proposals), building a collective business culture (sharing, collaborating, cooperating), etc. There are new jobs that grow as derivatives (differentiations) from previous jobs and businesses, and there are ones that are entirely new as a result of diversification and innovation [64,65,66].

5.5. Gender Perspective in PAC Livelihood Recovery

In real terms, the recovery of PAC livelihoods is explicitly carried out on groups of men and women. If the male group carries out the agro-complex business, the female group carries the banana chip, palm sugar, and woven bamboo crafts. Women’s participation is high in food processing and packaging business training. Participation is high (84 percent) because it follows their interests. However, their participation is still biased towards production, not marketing yet. High participation is also biased towards the older age group (90 percent), while it still needs to be clarified for the young. There is no specific, explicit strategy for young members of PAC, both men, and women. This strategy also encourages young PAC groups to create and innovate tacit strategies.

The participation of men is dominant in agriculture, animal husbandry, fishery, and forestry (85 percent). Apart from the four according to interest, it has also become a culture. Therefore, the explicit strategy becomes agro-complex bias. Huma rice, peanuts, bananas, and corn are the primary agricultural commodities besides chicken and sheep farming. Apart from wood, cardamom, and galangal, sugar palm and honey bees are mainstays in the forestry sector. For strengthening agricultural businesses, pumping assistance is part of an explicit strategy to anticipate drought in the dry season. The others were assistance with ten tractor units, agricultural product processing machines, and packaging and marketing equipment for agricultural products.

Technically, the mentoring method is mainly carried out for the male PAC group because the number and types of businesses are varied and complex. The authors of [35] confirmed that strengthening PAC economic capital in an explicit strategy is always dominant in agriculture, livestock, fisheries, and forestry. Even though the assistance to the female PAC group was less, it was intensive and focused on food-processing crafts. The involvement of female PAC members has been carried out, but production bias has yet to reach marketing and institutional management. Participation in cooperative management exists but still needs to be improved. Assistance is also carried out by related technical offices but is still biased towards agro-complex and male groups. A total of 68 percent of rural-sector work is performed by women [58,67].

Informant A (55 years old, female representing as an PAC administrator and PAC cooperative) stated: “Actually, the opportunities for PAC men and women to be involved in managing rural economic institutions are very open, except for those young and residence has moved to another area”. However, the PAC participation in business training and mentoring could have been improved, as both were only given to pilot groups. Complete assistance has yet to be carried out because restrictions hamper it due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The implication is that many PAC men and women do not know about the explicit strategy. The livelihoods of rural communities cannot be generalized because they are interrelated [64,68,69].

In fact, the participation of PAC women in agriculture activities is still relatively high (51 percent), while in the non-agriculture sector very low (13 percent). Thirty-five percent of women are the owners of agricultural land. However, women are only a little involved in the explicit strategy. Women are more accommodated in the tacit strategy, characterized by their dominant role in the business of rice stalls, children’s snack stalls, basic food stalls, traveling vendors, convection, etc. All this changed the composition of breadwinners in the household, from initially dominated by men to equity with women. In addition, women also play a role in the craft business of food, bamboo woven crafts, village officials, boarding school administrators, retail fuel services, etc.

All of this confirms that the integration of explicit and tacit strategies has increased and expanded the role of women, from previously dominant in the agricultural, livestock, and forestry sectors to livelihoods in the non-agricultural sector as farmers. Informant L (46 years old, DMU consultant reference) revealed, “in the 2013 LARAP stated that before UCPS was implemented, 51 percent of PAC women were farmers, both owners (35 percent), cultivators and farm laborers (11 percent), the 49 percent of PAC women who do not work in the agricultural sector, around 87 percent are only homemakers, 11 percent manage stalls, and the rest are food craftsmen, village officials, buying and selling, and civil servants”. However, after access to roads and transportation improved, the role of PAC women increased in number and type. Trade is the favorite business of women, then itinerant traders, food, and sewing artisans.

5.6. Constraint and Expectations for PAC Livelihood Recovery

Socio-economically, the obstacle to restoring livelihoods was dominant, sourced from the internal environment of the PAC. First, economic disorientation and distrust have made more than half of the PAC (50.63 percent) demand that business capital be distributed. Second, the PAC had yet to have a formal organizational culture, so they always wanted instant capital in applying for venture capital to the PAC cooperative (86 percent). Third, because there is a motive and disorientation in applying for funds, the management of the PAC cooperative is tightening the distribution of working capital. In total, 21.52 percent of the PAC still want cooperatives to improve and continue, 20 percent want better cooperative services, and 12 percent want cooperatives to play a role in marketing. Meanwhile, 6 percent want to develop members’ businesses, and 2.5 percent want the equal distribution of the remaining business results. The multifunctional, multi-business, and multi-purpose nature of a cooperative in rural areas is social capital [70,71,72].

In real terms, the PAC expects that training and mentoring will be carried out for all areas of agro-complex-based rural businesses (agriculture, animal husbandry, fisheries, plantations, and forestry) and non-agro complexes. Training, mentoring, and capital assistance are carried out in the production business sub-system (on-farm) and the off-farm sub-system (including farming input services, product processing, and marketing of business products). For the majority of those in PAC with low education, preparing a business plan is a challenging job. Therefore, training and mentoring should be focused on group administrators and educated young members of PAC. Strictly speaking, PAC need business capital assistance, but it needs human capital that is adaptive to formal mechanisms.

The results of the FGD formulated “new livelihood opportunities for growth are still open, both from the agro-complex sector, trade, and transportation, as well as the education sector, ecotourism, agrotourism, creative economy, logistics services, energy services, clean water services, community-based agro-industry, community-based seeding, etcetera. Tacit and explicit strategy collaboration must be increased in strengthening natural capital, economic capital, financial capital, social capital, and human capital. Weir mitigation must be internalized and institutionalized so that settlement designs, infrastructure, and economic activities do not harm the weir ecosystem. Livelihoods must continue to be created and innovated, but the feedback is favorable to the dam ecosystem. Called it agroforestry, organic and inorganic waste processing, and community-based seed breeding for sustainable greening in all conservation zones”.

6. Conclusions

We examined explicit and tacit strategies for partially integrated PAC livelihood recovery through surveys, in-depth interviews, and FGDs. Recovery by integrating explicit and tacit strategies is more capable of restoring PAC livelihoods than partial strategies. We used outcome mapping and different tests to survey direct and tacit strategy input, process, output, and outcome data from 325 families (975 individuals) of PAC UCPS. First, direct strategy inputs were in the form of economic capital, physical capital, and human capital (facilitators). In contrast, tacit strategies include social capital, natural capital, information capital, and human capital (collaborators).

The exact strategy process began with interest mapping, training, facilitating the formation of MFIs and PAC cooperatives, capital assistance, and facilitation of access to marketing networks. Meanwhile, the tacit process begins with the initiation of educated and skilled PAC youth in villages and overseas to carry out resilience, adaptation, coping, and mitigation through critical dialogue and collaboration in autonomous physical and virtual spaces, significantly developing the PAC generation. Concretely enabling, strengthening, advocation, and innovation of new businesses added value for only local commodities, marketing through applications, capital coping, and risk mitigation.

Explicit strategy recovered 11 types of PAC livelihoods, the tacit strategy 15 types of livelihoods, and the integration of the two into 26 types of livelihoods. The integrated strategy collaborates initiatives, creation, adaptation, coping, mitigation, and innovation internalized from the PAC ecosystem with interventions and innovations in the form of policies, programs, and assistance introduced from the external PAC environment. However, it took works to integrate participants, volunteers, and collaborators from the tacit strategy with facilitators, facilitators, and consulting agents from the explicit strategy. The autonomous village’s physical and virtual critical dialogue spaces can bridge and bind the two.

Suppose the explicit strategy used educated, skilled, and contracted professional assistants to facilitate and introduce innovations for restoring PAC livelihoods within a particular time; in that case, the tacit strategy is driving young collaborators who care, are educated, talented, skilled, have a leadership spirit, and are experienced entrepreneurs voluntarily from space local, both in rural and overseas positions. Based on their awareness, they share and collaborate physically and virtually, whenever and wherever agreed. If economics and technology are the main assets of an explicit strategy, then a tacit strategy focuses more on social, cultural, and ecological capital.

These results have implications for the survey design and action plan for PAC pumped storage livelihood recovery conducted by MDU, the government, academics, and NGOs. Strictly speaking, if the target of the explicit strategy is biased towards men and women as heads of households, then complement it with a tacit strategy that targets more youth, women, and PAC children. The integration strategy collaborates intervention and innovation (supply-driven) from the external environment with initiatives, participation, and adaptation (demand-driven) from the PAC environment. Integration is more than collaborative, but with an insight into gender justice and growing self-sufficiency, the main prerequisite for realizing sustainable livelihood recovery.

Some limitations to the research results are essential to keep in mind. First, the nature of the mixed method research is not supported by data analysis with inferential statistics in the quantitative design for the explicit strategy and strong dialectics in the qualitative method for the tacit strategy that uses the citizenship method approach, so the conclusions are not robust. Second, the integration of explicit and tacit strategies for livelihood biases that have already grown, while aspects of livelihood sustainability, including new livelihood potentials and opportunities, still need to be mapped. Third, opening PAC access can trigger brain drain and brain capital. All of these points need further research on the issue of restoring the livelihoods of PAC and their generation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S. and C.A.; methodology, I.S. and G.K.; software, R.S.S.; validation, I.S., R.S.S. and C.A.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, G.K.; resources, C.A.; data curation, I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S.S.; visualization, finalizing manuscript, G.K.; supervision, I.S. and R.S.S.; project administration, C.A.; funding acquisition, I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Department of Agricultural Sciences, Agricultural Faculty, Universitas Padjadjaran (protocol code NIP. 197409252008121001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We—I.W., R.S.S., C.A. and G.K.—thank Universitas Padjadjaran for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABCGM | Academics, businessmen, community, government, and media |

| PAC | Project-affected community |

| HP | Hydropower plant |

| PS | Pumped storage |

| MSME | Micro-, small, and macro-entrepreneurship |

| UCPS | Upper Cisokan Pumped Storage |

| LARAP | Land Acquisition and Resettlement Action Plan |

| MI | Microfinance institution |

| MDU | Main Development Unit |

| PIU | Project Implementation Unit |

| FGD | Focus group discussion |

| IFAD | International Fund for Agricultural Development |

| IW | Indonesian workers |

| HA | Household assistants |

| LPG | Liquefied petroleum gGas |

| NGOs | Non-government organizations |

| SOP | Standard operational procedure |

| HF | Head of family |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparative analysis of the livelihood conditions of PAC before and after UCPS.

Table A1.

Comparative analysis of the livelihood conditions of PAC before and after UCPS.

| No. | Livelihood Aspect | Before UCPS | After UCPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Living conditions | Stage (70%), permanent (20%), and semi-permanent (10%). | Stage (40%), permanent (40%), and semi-permanent (20%). |

| 2 | Economic capital | Informal sources (60%), dealers (25%), and 15% formal. | Informal sources (70%), non-formal (20%), and 10% formal. |

| 3 | Social capital | Local and reciprocal norms are high (80%), but external networking is weak. Land tenure relations are 60% owned and 40% cultivated. | Local and reciprocal norms fade (60%). Formal norms, networking, and collaboration are widespread (40%). Land tenure relation 75% owned. |

| 4 | Natural capital | 85% of the economy is based on natural resources, paddy fields, fields, and forests, 15% other sectors. | 60% of the economy is based on natural resources, and 40% is in other sectors. Paddy fields converted 20% and dry land 20%. |

| 5 | Institutional capital | 80% of decisions go through local institutions, while only 20% through formal institutions. | 55% of decisions go through formal institutions, while local institutions drop to 45%. |

| 6 | Source of income | 85% agriculture, animal husbandry, and primary forestry, while 15% MSME and non-agricultural sectors. | 80% agriculture, animal husbandry, and primary forestry, 20% MSME scale agro-industry, and 55% non-agricultural sector. |

| 7 | Land access | Private and state land is available within the scope of the village, with affordable purchase and rental prices. | Private and state land is available inside and outside the village, the land purchase price has increased by 50–100%, and the cultivated area has narrowed. |

| 8 | Road access and transportation | Passed by rough paved village roads (30%), cobbled village roads (30%), and dirt alleys (40%). 40% four-wheeled transport and 60% modified two-wheeled vehicles. | Hotmix roads (40%), asphalt and concrete village roads (40%), and concrete alleys (20%). Four-wheeled (80%) and two-wheeled (20%) transportation. |

| 9 | Access to the marketing of agricultural products and MSMEs | 80% is sold to middlemen and 20% to the local market. | 40% sold to middlemen, 30% to the local market, 25% to a wholesale market, 5% retail. |

| 10 | Access to health services | About 60% is hard to reach. There is only one Puskesmas (public health center) per sub-district. | About 80% access to Posyandu (integrated service post), village midwife, health center, and hospital. |

| 11 | Access to educational services | Only 2% have higher education, 20% secondary, and 75% have elementary. | About 10% have tertiary education, 40% are in middle school, and 50% have elementary schooling. |

| 12 | Information access | Only 35% internet access, limited cellular network, and blank spots. | 65% internet access, 75% good access to the network, and 25% not good. |

| 13 | Access to Capital | Family (85%), bank (10%), dealer (3%), and moneylender (2%). | Families (53%), cooperatives (30%), banks (10%), traders (5%), and investors (2%). |

| 14 | Access to employment or business | 70% in agriculture, forestry, plantation, and animal husbandry; 15% trading (stalls and distribution); 3% palm sugar craftsmen; 3% construction workers; 2% transportation services; 2% government employees; 2% local migrant workers; and 1% international migrant workers. | 60% in the agricultural sector; 17% trading (basketball stalls, convenience stores, traveling sellers); 5% chips artisans, furniture, workshops, cell phone counters, convection, rice stalls, transportation, logistics, and retail fuel; 5% material shops, distributors, and sawmills; 2% construction workers; 2% civil servants; 5% local migrant workers; 1% international migrants. |

| 15 | Access to food: Sources of carbohydrates (rice) and protein (meat, eggs, fish) | 80% of carbohydrate sources (rice) are self-produced. 90% of protein sources are purchased from stalls and markets. | 60% of rice is self-produced. 90% of protein sources are purchased from markets, stalls, and mobile vendors. |

| 16 | Energy access(electricity, oil, gas, and vehicle fuel) | Only 65% have direct access to electricity, and the rest are attached. 80% still use firewood. 40% of fuel access to gas stations, the rest to retailers. | 85% access to electricity directly, the rest stuck. 60% use firewood, and 40% firewood and gas. 80% BBM access to mini gas stations. |

| 17 | Access to clean water: Drinking water and water for MCK) | Easy, because 80% of settlements are in valleys. | It is relatively complicated in the dry season because 80% of settlements are on the ridge. |

References

- Zhu, B.S.; Ma, Z. Development and Prospect of the Pumped Hydro Energy Stations in China. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1369, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, T.; Imano, H.; Oshima, K. Development of pump turbine for seawater pumped-storage power plant. Hitachi Rev. 1998, 47, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y. Pressure fluctuations in the vaneless space of High-head pump-turbines—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Suárez, J.L.; Ritter, A.; Mata González, J.; Camacho Pérez, A. Biogas from animal manure: A sustainable energy opportunity in the Canary Islands. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakers, A.; Stocks, M.; Lu, B.; Cheng, C. A review of pumped hydro energy storage. Prog. Energy 2021, 3, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Arhonditsis, G.B.; Gao, J.; Chen, Q.; Peng, J. The magnitude and drivers of harmful algal blooms in China’s lakes and reservoirs: A national-scale characterization. Water Res. 2020, 181, 115902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, H.; Gou, Z.; Xie, X. A simplified evaluation method of rooftop solar energy potential based on image semantic segmentation of urban streetscapes. Sol. Energy 2021, 230, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, G.T.; Han, M.; Mekonnen, S.A.; Patrobers, S.; Khan, Z.W.; Tuan, L.K. Pumped energy storage system technology and its AC–DC interface topology, modelling and control analysis: A review. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickler, C.M.; Coe, M.T.; Costa, M.H.; Nepstad, D.C.; McGrath, D.G.; Dias, L.C.P.; Rodrigues, H.O.; Soares-Filho, B.S. Dependence of hydropower energy generation on forests in the Amazon Basin at local and regional scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9601–9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Dunkl, I.; Von Eynatten, H.; Wijbrans, J.R.; Gaupp, R. Products and timing of diagenetic processes in upper Rotliegend sandstones from Bebertal (North German Basin, Parchim formation, Flechtingen High, Germany). Geol. Mag. 2012, 149, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Van Westen, A.; Zoomers, A. Compulsory land acquisition for urban expansion: Livelihood reconstruction after land loss in Hue’s peri-urban areas, Central Vietnam. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2017, 39, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, R.A.; Anokye, P.A. Housing for the urban poor: Towards alternative financing strategies for low-income housing development in Ghana. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2015, 37, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayektiningsih, T.; Hayati, N. Potential impacts of dam construction on environment, society and economy based on community perceptions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 874, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Indicators for sustainable communities: A strategy building on complexity theory and distributed intelligence. Plan. Theory Pract. 2000, 1, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorward, A.; Chirwa, E.; Boughton, D.; Crawford, E.; Jayne, T.; Slater, R.; Kelly, V.; Tsoka, M. Towards “smart” subsidies in agriculture? Lessons from recent experience in Malawi. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 2008, 116, 1–6. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/93191/NRP116.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, O. Strategic collaboration in local government. Local Gov. Res. Ser. 2012, 2, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Takács-György, K.; Lencsés, E.; Takács, I. Economic benefits of precision weed control and why its uptake is so slow. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2013, 115, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Guenther, B.; Leavy, J.; Mitchell, T.; Tanner, T. Adaptive Social Protection: Synergies for Poverty Reduction. IDS Bull. 2008, 39, 105–112. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00483.x (accessed on 10 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gilfillan, D.; Pittock, J. Pumped Storage Hydropower for Sustainable and Low-Carbon Electricity Grids in Pacific Rim Economies. Energies 2022, 15, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, V.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Lanzas, M.; Brotons, L. Designing a network of green infrastructure for the EU. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 196, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, T.D.; Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. Can. Public Policy/Anal. Polit. 2003, 29, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Ran, Q.; Ren, S. The impact of the new energy demonstration city policy on the green total factor productivity of resource-based cities: Empirical evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 66, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.L.; Choi, Y.J.; Yun, M.H. An Implication of Policies for Farm Succession in Foreign Countries. J. Agric. Ext. 2014, 21, 939–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scott, J. Sociology. The Key Concepts. 2006. Available online: https://www.shortcutstv.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Sociology_the_key_concept.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Scoones, I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Engaging Diaspora in Local Development: An Operational Guide Based on the Experience of Moldova; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, J.L. Book Reviews: Paulo Freire. Education for Critical Consciousness; Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Johnson, M.B.; Nicole, J.M.; Christensen, M. Using Student-Centric Technology for Educational Change 143 Using Student-Centric Technology for Educational Change. Glob. Educ. Rev. 2015, 2, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Han, W.; Kumail Abbas Rizvi, S.; Naqvi, B. Is Digital Adoption the way forward to Curb Energy Poverty? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 180, 121722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.; Crowe, P.R.; Stori, F.; Ballinger, R.; Brew, T.C.; Blacklaw-Jones, L.; Cameron-Smith, A.; Crowley, S.; Cocco, C.; O’Mahony, C.; et al. ‘Going Digital’—Lessons for Future Coastal Community Engagement and Climate Change Adaptation. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 21, 105629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.P. Sustainable competitive advantage—What it is, what it isn’t. Bus. Horiz. 1986, 29, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmi, F.; Pranoto, H.; Lubis, M.S. Smart Nation Initiative: Strategy and Implementation Smart Nation Initiative: Strategy and Implementation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 648, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckinley, J.D.; Lafrance, J.T.; Pede, V.O. Climate Change Adaptation Strategies Vary With Climatic Stress: Evidence From Three Regions of. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 762650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Zullig, L.L.; Choate, A.L.; Decosimo, K.P.; Wang, V.; Van Houtven, C.H.; Allen, K.D.; Nicole Hastings, S. Intensification of Implementation Strategies: Developing a Model of Foundational and Enhanced Implementation Approaches to Support National Adoption and Scale-up. Gerontologist 2022, XX, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisch, S.; Menz, M.; Birkinshaw, J. Spatially dispersed corporate headquarters: A historical analysis of their prevalence, antecedents, and consequences. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R. The theory of the knowledge-creating firm: Subjectivity, objectivity and synthesis. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2005, 14, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermundsdottir, F.; Aspelund, A. Sustainability innovations and firm competitiveness: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage Publication: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2007; Available online: https://revistapsicologia.org/public/formato/cuali2.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Kumar, D.; Prasad, B.B. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes embedded molecularly imprinted polymer-modified screen printed carbon electrode for the quantitative analysis of C-reactive protein. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 171–172, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]