Abstract

The widespread commercialization of cultured meat, produced from animal stem cells grown in vitro, faces significant challenges related to technical, regulatory, and social acceptability constraints. Despite advancements in knowledge, the acceptance of this innovation remains uncertain. Understanding individuals’ decision-making processes and interpretative patterns is crucial, with media framing playing a key role in shaping attitudes toward cultured meat adoption. This research, focusing on Twitter as a social media platform, examines the impact of media framing on consumer attitudes (cognitive, affective, and conative) regarding cultured meat. Qualitative (content analysis) and quantitative (MANOVA) analyses were conducted on 23,020 posts and 38,531 comments, selected based on media framing or containing relevant attitude components. This study reveals that media-framed posts significantly influence consumer attitudes compared to non-media-framed posts. While different types of media framing (ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief) exhibit varying impacts on attitude components, posts combining ethical, intrinsic, and informational frames have a more substantial effect on cultured meat acceptability. The belief frame, particularly for the behavioral component, is equally influential. Consumer attitudes toward cultured meat are found to be ambivalent, considering the associated benefits and risks. Nevertheless, the affective component of attitude is notably influenced by posts featuring informational and ethical media frames. This study suggests implications for authorities and businesses, emphasizing the importance of differentiated education and marketing strategies. Advertising messages that combine ethical, intrinsic, and informational frames are recommended. Additionally, this study advocates for regulatory measures governing the production, marketing, and consumption of cultured meat to instill consumer confidence in the industry. By highlighting the significance of beliefs in cultured meat consumption behavior, this research points toward potential exploration of cultural and religious influences in future studies.

1. Introduction

Most scholarly studies identify meat substitutes, including cultured meat, as a solution to the impacts of conventional meat production and farming [1,2], raising several major concerns. Verbeke et al. [3] define cultured meat as the result of the technical multiplication of the source cells of an animal raised in a healthy place for the purposes of this type of production [3]. The challenges and opportunities for cultured meat production are major due to increased meat consumption. For example, there is concern about food security in light of a rapidly growing world population (projected to be 9.8 billion people by 2050 [4]) and increased meat consumption (an increase of 65% for pork and of 80% for beef by 2050) [5]. Technical challenges include high production costs, the issue of quality control, consumer acceptance, regulatory issues, and ethical considerations associated with the cell source and culture media used to produce meat [2]. However, compared to conventional meat, cultured meat also offers many opportunities, particularly in terms of sustainability, animal welfare, food safety, and food personalization [6]. Its large-scale adoption is therefore closely linked to the ability to meet the challenges above while capitalizing on opportunities.

In addition, the world faces the challenge of environmental protection (including issues such as high CO2 emissions generated by the livestock sector and the overuse of agricultural land and water) and the fight against climate change [7]. Additionally, the issue of human welfare (nutritional intake and health) and animal welfare (improving the living conditions of animals) [8] is also crucial. Thus, compared to conventional meat, the production of cultured meat provides solutions to these challenges. Public debates around conventional meat highlight negative externalities, such as water depletion, climate change, the disruption of nutrient cycles, and harmful effects on biodiversity [8,9,10]. Moreover, several authors consider that the meat and livestock industry must be at the heart of the solutions to climate change [11,12].

Other studies have shown that consumers are increasingly concerned about animal welfare and sustainable meat production [13,14]. Therefore, the desire to combat animal cruelty and environmental externalities is often cited as an example of prosocial consumer motivation for lifestyle changes that reduce meat consumption [1,15]. However, these efforts to reduce meat consumption by pro-environmental consumers are being negated by the rapid growth of the world’s population. According to the results of research carried out by Onwezen et al. [1], Siddiqui et al. [16], and Lin-Hi et al. [17], meat lovers are more likely to try cultured meat due to the sustainability claims attached to it [16,17].

Recent literature shows that consumers are well-informed on sustainability (climate change and environmental protection), animal cruelty, and animal welfare issues [13] and that they perceive factory farming and slaughter as unethical and unjustified [10,16]. Compared to conventional meat, cultured meat offers environmental benefits, such as decreased water use during production and the generation of fewer greenhouse gas emissions [6].

Finally, in the context of COP27, held in November 2022, the UN warned against maintaining a highly animal-based diet to prevent future pandemics. Thus, the current study responds to this caveat by exploring the acceptability of cultured meat as a possible alternative.

Indeed, the range of alternatives to conventional meat, namely, fish and plant-, soy-, and insect-based meat substitutes, as well as cultured meat, emerges as a sound promise in the face of these societal challenges (food security, environment, climate, and health/wellbeing) [18,19]. However, to date, Singapore is the only state to have put lab-grown meat on shelves. In November 2022, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the sale of cultured chicken produced by the Californian start-up Upside Foods. While more than 30 European companies are working on cultured meat, no pre-market approval has yet been requested.

Despite the advancement of knowledge, predicting whether this innovation will find general acceptance is difficult. To date, research has primarily focused on expected consumer behavior (the behavioral component of attitude). This includes studies of factors that positively or negatively influence consumer intentions, i.e., future acceptance or the rejection of cultured meat [20,21,22,23,24,25]; perceptions; the likelihood of trying, purchasing, or consuming cultured meat products [26,27,28]; and comparative purchase intentions across cultures [29].

However, several important questions related to consumers’ acceptability on social media of meat grown remain. For example, how can we improve the acceptability of cultured meat to online consumers? What are the best communication techniques (media framing) that have the most influence on each of the components of online consumer attitudes (Twitter)? Which line of online communication is best for which specific objective? To answer these different questions, several theoretical foundations related to this study will be discussed as follows:

- (1)

- Random utility theory, as consumers will accept cultured meat based on the benefits of that meat;

- (2)

- The theory of ambivalence, as meat consumption gives rise to a conflict between positive and negative attitudes (benefits and risks);

- (3)

- The three-dimensional theory of attitude to explore each component of attitude;

- (4)

- Media framing, as it influences decision-making as well as mental interpretation patterns of individuals.

Indeed, in 1993, Entman (p. 52) [30] asserted the importance of understanding new or challenging phenomena through the process of media framing: “To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described”. To our knowledge, aside from the research conducted by Goodwin and Shoulders [31], Dilworth and McGregor [32], and Bryant and Dillard [33], who investigated the issues of traditional media coverage and framing in relation to the acceptance of cultured meat, and a study by Pilařová et al. [34] addressing sociological framing on Twitter, the phenomenon has not been analyzed through the lens of psychological framing on social media. Nonetheless, several studies investigating media framing from a psychological perspective have demonstrated its influence on decision-making, as well as on individuals’ mental interpretive patterns [35]: changes in belief, attitude, and behavior (e.g., [36,37]). Hence, the purpose of this paper is to grasp the influence of media framing (social media platform Twitter) on the components (cognitive, affective, and conative) of consumer attitudes towards cultured meat. We investigate whether various media frames of cultured meat on Twitter influence distinct consumer attitudes and if these variations affect each aspect of attitude and subsequent purchase and consumption behavior.

This study thus contributes to filling a research gap in the emerging field of food technology, highlighted by Goodwin and Shoulders [31] and Dilworth and McGregor [32], namely, the media framing of cultured meat across countries and media types. Thus, this study will contribute in an original and unique way to improving online communication techniques in order to make consumer attitudes toward cultured meat more positive.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Conceptual Framework

2.1. The Influence of Media Framing

The strength of media framing research lies in its multidisciplinary nature [35,38].

There are two main approaches to framing [36]: (1) the sociological approach, which views frames as schemata of interpretation that individuals use to make sense of occurrences around them and seeks to identify dominant frames/power struggles in the media (e.g., [30,39]); (2) the psychological approach, which aims to orient the message, seeking to elicit emotion and engaging certain values (and occulting others), framing influences individuals’ train of thought; studies adopting this approach look to identify the role of framing in the perception and interpretation of reality (e.g., [40,41]).

In this research, it is the psychological perspective of media framing that was adopted and which has been used by many authors [36,37,42,43] in order to gain an understanding of the impact of framing on consumer attitudes and behaviors toward a product, a service, or a company to the extent that “the framing of cultured meat has a significant effect on many attitudes and beliefs about the product, as well as behavioral intentions toward it” (e.g., [33], p. 6). Indeed, it has been shown that the determinants of cultured meat (considered here as media frames) influence consumer attitudes [21]. For example, the benefits associated with the different determinants of cultured meat positively influence consumer attitudes, while the risks associated with this meat negatively influence consumer attitudes.

By using keywords, phrases, and images in a newspaper [30] or social media [33], communication experts can reinforce a particular representation of reality and a particular emotional response associated with that reality [30]. For example, by purposefully omitting certain elements in a newspaper or broadcast, their message can suggest a specific perspective to the readers or listeners or trigger a specific feeling in them that is different from general reality [43].

In relation to cultured meat, the authors of Twitter posts may choose to talk about the intrinsic characteristics of cultured meat (taste, appearance, tenderness, and so on), ethical attributes (benefits to animals and the environment), or the informational or belief aspects with the aim of orienting and/or eliciting specific emotional responses to the exclusion of others. This study therefore aims to understand whether each publication about cultured meat on Twitter generates a different attitude among consumers depending on the media frame and whether these differences impact each component of the attitude, as well as the purchasing and consumption behavior.

2.2. Determinants of the Adoption of Cultured Meat

Meat consumption is associated with a few attributes and sociocultural behaviors. It can meet nutritional needs, but it can also relate to cultural dogmas and religious laws [44]. The influence of this range of determinants on consumer choice is rooted in microeconomic foundations based on the principle of utility maximization and/or random utility theory [45]. Consumers will therefore accept a meat alternative if and only if this alternative speaks to the determinants representing an individual or collective advantage or benefit.

The literature shows that cultured meat has both advantages and disadvantages that can trigger ambivalent attitudes on the part of consumers. Its consumption, therefore, generates contradictory emotional responses. This dichotomous reaction has already been addressed in several studies (e.g., [21,24,46]). Defined as a conflict between determinant-generated positive and negative attitudes (benefit/risk) in the individual at the time of decision-making [47], consumption ambivalence can be viewed as a psychological state reflecting the concept of the meat paradox.

This concept of ambivalence is pertinent insofar as it makes it possible to identify and understand benefit determinants, which will contribute to the acceptability of cultured meat, and risk determinants, which will lead to its rejection. Based on the tripartite theory developed by Rosenberg [48], the influence of each ambivalent determinant will be examined for each component of online consumer attitudes. The tripartite theory holds that attitude is comprised of a cognitive component (measuring consumers’ level of knowledge about the object of study), an affective component (measuring the level of attachment to or affection for the product or brand), and a conative component (providing an understanding of intentions to purchase, pay, and consume) [48].

Although some studies have addressed media coverage of cultured meat, research on media frames and their influence on cultured meat consumption behavior is lacking. Bryant and Dillard [33] have examined mainstream media by considering three media frames: “societal benefits”, “high tech”, and “same meat”. Like Bryant and Dillard [33], researchers consider each ambivalent determinant group identified in the literature as a media frame in the context of Twitter. The researchers therefore conducted an a priori analysis of four media frames identified in the literature and proposed the following research hypotheses.

- -

- Ethical media frame of cultured meat: this ambivalent frame is defined by the benefit associated with the idea of sustainability, on the one hand, and the risk associated with unnaturalness on the other. While the notion of cultured meat’s sustainability is connected to its capacity to protect the environment [27,32,49], its unnaturalness is defined as a reaction of disgust and fear of unknown risks associated with new technology [50,51].

Hypothesis (H1).

The ethical media frame (sustainability and unnaturalness) of cultured meat will influence each component of consumer attitude toward cultured meat.

- -

- Intrinsic media frame of cultured meat: this frame is related to nutritional content, flavor (benefit) and consumer health concerns (risk), including the absence of drugs and chemicals (benefit) and distrust of biotechnology (risk). Nutrients are defined as a perceived sensory quality. They include the appearance, texture, flavor, taste, tenderness, sweetness, and chemosensory attributes of CM ([49]). This attribute is linked to nutritional factors such as the amount of protein, calories, and fat in meat [25,49]. Health concerns associated with cultured meat are described by different authors as food safety considerations in relation to production methods and materials. Conversely, the absence of drugs and chemicals is a positive factor insofar as cultured meat production does not involve growth hormones, synthetic pesticides, or antibiotics [22,24]. Distrust of biotechnology (risk) is associated with a negative perception of the bioengineering and nanotechnology techniques used in its manufacturing [24].

Hypothesis (H2).

The intrinsic media frame (nutritional content, flavor, absence of chemicals, health concerns, and distrust of biotechnology) of cultured meat influences each component of consumer attitude.

- -

- Informational media frame or frame of initial information received by the consumer or of initial consumer reactions. Examples are food curiosity (benefit), food neophobia (risk), regulation (benefit), and conspiracy theories (risk). In the literature, food neophobia (as opposed to food curiosity) is defined as the reluctance to consume, avoidance, or distrust of new foods [24,51]. Regarding the regulation of the cultured meat industry, some authors suggest that it is viewed as a guarantee by consumers [5,52], whereas conspiratorial ideation refers to consumers’ “general predisposition to believe” that cultured meat is the result of a plot by profit-driven individuals [28].

Hypothesis (H3).

The informational media frame (food curiosity, neophobia, regulation, and conspiratorial ideation) of cultured meat affects each component of consumer attitude.

- -

- Belief media frame, where risks are associated with conservative values and benefits with good-deed morality (doing good for others, making sacrifices to protect the environment, and so on). Morality is perceived as a community’s set of rules and decisions that appeal to common sense, intended to ensure that the actions and behaviors adopted are “good or positive” for the collective [44]; conservatism, on the other hand, is associated with favoring older or traditional values [53] and opposing changes, such as the novel manufacturing of cultured meat.

Hypothesis (H4).

The belief media frame (consumer morality and religious and cultural conservatism) of cultured meat has an effect on each component of attitude.

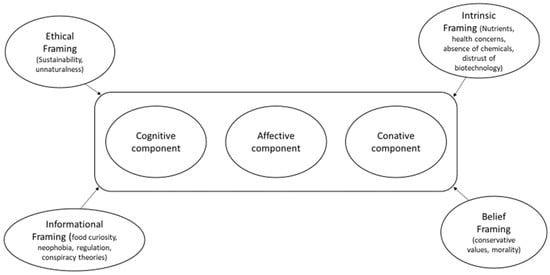

The conceptual framework (Figure 1) was built based on the theories developed and explained above. Thus, the ambivalent determinants of cultured meat identified in the literature (informational, ethical, intrinsic, and beliefs) were considered as media frames in order to understand if these media frames in Twitter publications influence the components of attitude (three-dimensional theory) present in Twitter comments.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: impact of cultured meat media framing on attitude.

3. Material and Methods

The methodology based on “text mining” involved three main steps: (1) extraction and cleaning of the Twitter data, followed by transformation of the variables using a dictionary of keywords; (2) qualitative analysis of tweet content; (3) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) based on the keywords in order to determine the influence of media framing on each component of the attitude toward cultured meat.

3.1. Extraction, Cleaning Data, and Transformation of the Variables

3.1.1. Identification of Keywords

A number of keywords were drawn from the literature review. Their popularity on Twitter was then tested by counting the number of posts and comments associated with these keywords. The following keywords were identified and selected: cultured meat, in vitro meat, artificial meat, lab-grown meat, animal-free meat, clean meat, synthetic meat, test tube meat, and meat substitute. A nine-month span was chosen to counter one of the major limitations of psychological approach research, which focuses on short-term effects to illustrate the process activated by framing [35].

3.1.2. Data Collection and Processing

A scientific research project was submitted to Twitter to request access for data extraction. After ensuring that our project met scientific importance, research, and confidentiality conditions, we were granted developer access, which allowed us to obtain posts and/or replies on cultured meat in Canada. Using the keywords in English and French, the researchers extracted 165,750 tweets (posts and comments) over a nine-month period (from 1 January to 30 September 2022), of which 153,727 were in English and 12,023 in French.

Using the get_all_tweets() function of the academictwitterR library of the R programming language, the French- and English-language data were extracted, processed separately, and then combined using the R rbind() function.

The database was then cleaned by automatically eliminating duplicate posts and comments. To remove duplicates automatically, the “delete duplicates” submenu of the “data” menu of the database Excel sheet was used. Subsequently, the posts were categorized using the R software by media frame, and replies or comments were categorized by attitude component based on the “keyword dictionary” made up of the items (shown in Table A2) that measure each variable. As shown in Table A2, each attitude component variable (cognitive, affective, and conative component) has its own set of keywords. Likewise, each framing variable (ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief media frame) has its own list of keywords (see Table A2).

The data used in this study are exclusively public data from anonymous and non-identifiable sources. This is consistent with similar studies that have used publicly available social media content (e.g., [43,54,55]).

3.1.3. Identifying Posts and Comments

From the data extracted, the researchers identified four types of tweets: “replied_to”, “retweeted”, “quoted”, and “main tweets”. These tweets were grouped into two categories: (1) posts and (2) comments (replies to Twitter posts). They applied the following process in order to precisely identify “posts” and “comments”: (i) all the main tweets were classified as “posts”; (ii) for “quoted” tweets, two groups emerged: one consisting of quotes from existing posts and a second group of quotes that were not associated with any post. The quoted tweets of the second group (i.e., “quoted” tweets that were not associated with any publication) were therefore considered as “posts” because they generated replies or comments. The main tweets associated with this second group of “quoted” tweets were not found in our extracted data because they were published before 1 January 2022, but were cited by other Twitter users during the data extraction period (from 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2022). For this reason, they were counted as posts.

In summary, the tweets considered as publications are described as follows:

- -

- All the main tweets whose “type_tweet” column contains the mention: “main_tweet”;

- -

- All the other tweets that have been the subject of comments or replies but do not have a “main-tweet” mention and are not associated with any tweet having the “main-tweet” mention.

Regarding tweets considered as comments, these are all tweets in response to publications.

3.2. Data Analysis

In addition to having exclusively selected the tweets that contained the keywords related to cultured meat, a complementary preliminary analysis was carried out to ensure that the Twitter posts dealt with cultured meat. As recommended by Kozinets [56], only terms and verbatim extracts related to the object of study were used. A qualitative analysis was carried out using the R 4.2.0 programming language and QDA Miner 6.0.13 software. The SPSS 29.0.0.0 software platform was used for the quantitative analysis (MANOVA) on a final sample of 23,020 posts and 38,531 comments.

3.2.1. Qualitative Analyses

The qualitative analysis makes it possible to analyze the type of media framing in the publications and then verify the types of attitude components in the comments resulting from these publications. Following a content analysis of the posts and comments, the research team (composed of 2 researchers) coded the data a priori. For the inter-rater reliability and the discrepancy resolution, the researchers defined a coding grid (a priori thematic coding). Then, they created and regularly updated (weekly) the chronological basis of incidents or coding differences between the researchers. Indeed, the themes under which the publications are coded are known in advance. These are media frames relating to the “ethical”, “intrinsic”, “informational”, and “belief” characteristics of cultured meat. Likewise, the comments were coded under the themes “cognitive component”, “affective component”, and “conative component”. Unlike a posteriori coding, a priori coding assumes that themes and sub-themes are identified in the literature and known to researchers. Since the themes and sub-themes are known in advance, researchers are able to code under the same themes and subthemes, thereby reducing differences in the coding process [56].

The posts and comments were grouped by media frame and according to the tripartite theory of attitude (intrinsic, ethical, belief, and informational frame and cognitive, conative, and affective components). This made it possible to determine whether the type of media frame expressed through a post influenced the comments made by the consumers.

3.2.2. Quantitative Analyses

Analysis of variance (MANOVA) is a technique that compares the means of different groups and demonstrates the existence of statistical differences between the means. For example, by calculating the average of each attitude component (dummy variable measuring the presence of keywords) in the comments, the analysis of variance of these averages associated with each type of publication (media frame) makes it possible to verify the existence of a causal link between media frames and attitudinal components. That is, “dictionary keyword” averages are calculated per comment for each media frame. These averages are then compared in order to determine if there is a significant difference between these averages depending on the type of media framing. This methodology has been used by several authors in social media content analysis (e.g., [55]). This causal analysis was conducted between the framing variables (media frames) and the attitude component variables (attitude components).

Attitude component variables (the dependent variables) comprise three different variables—cognitive, affective, and conative—of consumer attitudes toward cultured meat. The dictionary keywords derived from the measurement items (the items from the measurement scales of each variable developed by the authors mentioned in Table A2) and their level of reliability and validity in relation to these variables are summarized in Table A2. Each of these attitude components was converted into a dummy variable (0, 1). A “dummy” variable is a variable that takes values of 0 or 1, where 1 means, for example, that the publication contains a keyword from the dictionary of a media frame. For example, if a dictionary keyword defining the cognitive component was identified in a Twitter user’s comment, then this component was attributed to the comment, which was therefore given the value “1” for the “cognitive component of attitude” variable; if not, the value was “0”. The process was repeated for the other attitude components. Concretely, the number “1” is assigned to a comment each time this comment contains a keyword from the dictionary. For example, if the keyword “eat”, which is a keyword from the conative component dictionary (Table A2), is identified in a comment, this comment obtains the number “1”. Then, these numbers are added and then divided by the number of comments. This is therefore a comparison of the average keywords per comment from each media frame. This method is consistent with several other studies, including one by Chicoine et al. [55].

In concrete terms, in the Twitter comments, the number of keywords was tallied using the following method:

- -

- Cognitive component variable: if, in a comment and/or response, any of the keywords from the dictionary defining the cognitive component variable were identified, that comment received the number 1 in the column corresponding to the cognitive component variable. However, if none of these keywords were found in the comment, the number 0 was assigned to that comment in the column of the “cognitive component” variable.

Here is a list of keywords from the dictionary of the cognitive component variable (see Table A2): Useful/useless, sensible/senseless, sure/unsure, beneficial/harmful, worth/worthless, perfect/not perfect, healthy/dangerous diet, safety, bad, know, safe, curious, curiosity, aware, information, propaganda, taught, diseases, fake, true, utile/inutile, sensée/insensée, sûre/non sure, bienfaisant/nuisible, valeur/sans valeur, parfaite/non parfait, saine/dangereuse, faux.

In reality, the values (0 and 1) in this case constitute a working rule (a principle in data science and econometrics) to count the number of keywords from the dictionary per variable.

- -

- The same procedure was carried out for the “affective component” and “conative component” variables, exclusively using the keywords from the dictionary identified for each of these variables (see Table A2).

Thus, the Excel file obtained allowed for the calculation of the sums, as well as averages of these keywords per variable. These averages were computed and compared based on the media frames (the publications from which these comments originate) through a MANOVA analysis in the SPSS 29.0.0.0 software platform.

To effectively capture the variables, the researchers supplemented the dictionary of measurement items identified in the literature with analogous words whose occurrence was frequent in the tweets. These frequently encountered analogous words were identified after a preliminary analysis of the tweets. They are listed in column 3 of Table A2.

Framing variables (independent variables): these refer to media framing and include all four media frames (ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief). Media frames were also converted into binary variables. As a result, each media frame is a categorical variable (0 = post having no media framing and 1 = post having at least one media framing). When considering the ethical media frame, 0 = post not having ethical media frame and 1 = post having ethical media framing.

For example:

- Ethical media framing variable: 0 = no ethical media framework keywords, 1 = presence of ethical media framework keywords.

- Intrinsic media framing variable: 0 = no keywords from the intrinsic media frame, 1 = presence of keywords from the intrinsic media frame.

- Informational media framing variable: 0 = no keywords from the informational media frame, 1 = presence of keywords from the informational media frame.

- Media belief framing variable: 0 = no keywords from the media belief framework, 1 = presence of keyword from the media belief framework.

The reliability and validity of the variables depend on the keywords in the dictionary. Indeed, these keywords derive their reliability and validity from the items from the measurement scales of these variables. As shown in Table A2, all of these variables exist in the literature and their measurement scales have been tested and validated by the different authors mentioned in Table A2. In addition, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of each of these variables is greater than 0.70 (see Table A2).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The respondent profile corresponds to all the Twitter users (whatever their country) who posted or commented on at least one tweet about Canadian-grown meat between 1 January and 30 September 2022. The samples of English- and French-language posts and comments were identified and extracted separately. These data are shown in Table A1 in Appendix A. The English-language sample corresponds to 89.91% of posts and 92% of comments. On average, each post was retweeted 5.383 times and received 3.38 direct replies and 8.73 likes. These results indicate the attention surrounding the topic of cultured meat on Twitter and the responses it arouses. Indeed, these results show that publications on cultured meat on Twitter generate a lot of reactions and comments. Furthermore, 58.28% of all the comments influenced the cognitive component of consumer attitudes, while dictionary keywords associated with the affective component triggered 25.31% of consumer reactions. Approximately 25.8% of Twitter users’ reactions to cultured meat were related to purchasing behavior. However, two or three different attitude components can be associated with a single comment. In addition, 38% of posts conform to the ethical media frame and 46% to the intrinsic media frame. Although they have not yet consumed cultured meat, consumers therefore seem to be more concerned about the intrinsic and ethical factors of this innovation. Informational and belief media frames account for 37% and 24% of posts, respectively. Some posts may be representative of more than two media frames at the same time, while others are free of media framing.

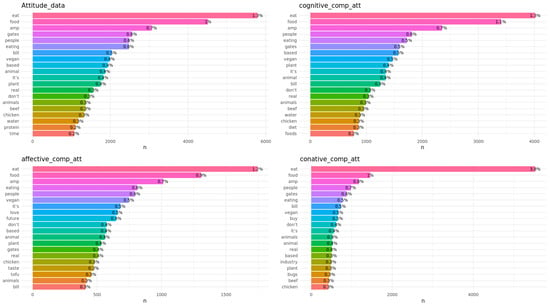

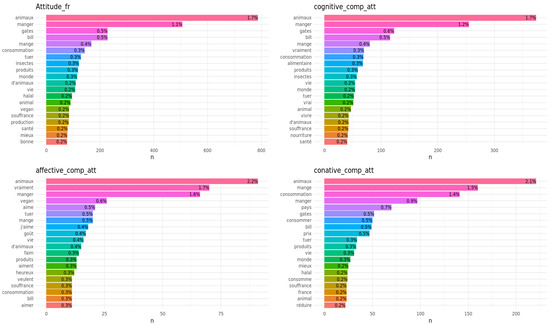

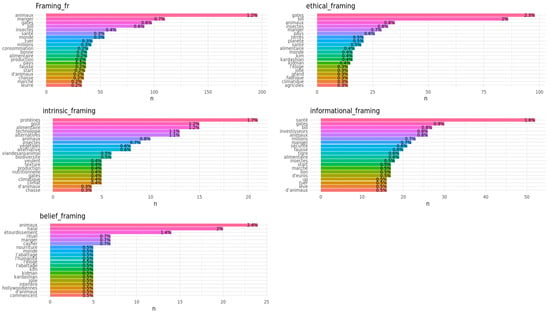

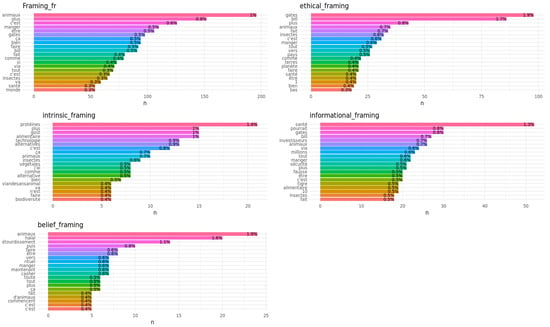

4.2. Qualitative Analysis

An analysis of the tweets (Table A3; Figure A1 and Figure A2) confirmed that many posts on cultured meat were framed according to the four media themes (ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief). Indeed, Table A3 represents a summary of the content analysis of the tweets. These are quotes from comments on posts related to cultured meat based on a cross-analysis of the four themes and each attitude component. Figure A1 and Figure A2 (in Appendix A) show the number of times that each keyword in the dictionary was used in the posts (keywords that define each media frame) and in the comments (keywords that define each attitude component). Each theme was found to encompass sub-themes, consistent with Bryant and Dillard [33] and Tang et al. [43]. For example, the theme “ethical media framing” encompasses the sub-themes or ambivalent determinants, namely, “sustainability” and “unnaturalness” (see Section 2.2: determinants of the adoption of cultured meat). The results also reveal the presence of ambivalent comments and responses on Twitter. The following are descriptions of each theme or media frame.

4.2.1. Ethical Media Frame

The ethical media frame was very prominent in Twitter posts. Consumers reacted in several different ways to posts that emphasized the issue of sustainability and the unnaturalness of cultured meat. An analysis of these reactions shows that each of the attitude components was affected either positively or negatively. For example, on the post, “Lab-grown meat and insects ‘good for planet and health’ #LabGrownMeat #Insects #ClimateChange #Environment #Food https://t.co/7h3Dwmu63l (accessed on 12 November 2022)”, one user had the following “cognitive” reaction: “It’s sometimes used as a meat substitute because the texture is similar, you make it by washing flour, which as a concept is hilarious”. This post and comment are also included in Table A3.

4.2.2. Intrinsic Media Frame

The most common media framing on Twitter is the one relating to the intrinsic qualities of cultured meat. Posts referring thereto, particularly to the nutritional content, flavor, absence of chemicals, distrust of biotechnology, and health concerns, have generated ambivalent cognitive, affective, and sometimes conative user reactions. The following example of a cognitive response illustrates this finding: “Perhaps meat from animals. I bet lab-grown meat from animal cells that are sourced without significant harm to the animal will eventually be the norm”; this was tweeted as a reply to a post highlighting the nutritional quality of cultured meat: “Sia Invests in Pet Food Made from Cultured Meat https://t.co/hwhX6ez8HJ (accessed on 12 November 2022)”. This example is also included in Table A3.

4.2.3. Informational Media Frame

The information associated with initial reactions influences each component of Twitter users’ attitudes. This finding is consistent with research conducted by Mancini and Antonioli [49] and Hwang et al. [24]. Indeed, tweets emphasizing curiosity, regulation, neophobia, and conspiracy in relation to cultured meat generate cognitive, affective, and conative reactions. Some posts representative of the informational media frame and the comments (cognitive, affective, and conative) they elicited are summarized in Table A3.

4.2.4. Belief Media Frame

Our results suggest a relationship between posts expressing beliefs and the cognitive, affective, and conative reactions of the platform’s users. Several belief-framed posts and the responses they triggered are summarized in Table A3. Conservative philosophy, whether religious or cultural, favors traditional or outdated values [53]; therefore, as a new food technology product, cultured meat stands at odds with conservative values.

4.3. MANOVA Data Analysis

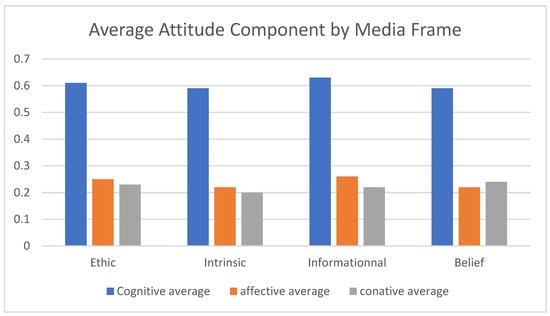

An analysis of the three components of attitude in Twitter comments (see Figure A2) shows that publications with a media frame of belief generate the greatest number of behavioral reactions (conative average = 0.24), publications characterized by informational and ethical media frames generate the greatest numbers of affective reactions (0.26 for informational framing and 0.25 for ethical framing) toward cultured meat, and publications with informational framing generate more cognitive reactions (0.63) in Twitter user comments.

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA; see Table 1) was used because there are several attitude component and framing variables [57] and because the former are scaled variables (binary variables or “dummy” variables), while the latter are categorical variables.

Table 1.

Results of the multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA).

Table 1 shows the results of the multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) obtained through the SPSS 29.0.0.0 software, as well as their levels of statistical significance.

The results of the MANOVA analysis show that all the multivariate difference measures (Wilks’ lambda) are significant (p < 0.05); therefore, all the attitude component variables (cognitive, affective, and conative components) vary across ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief media frames. This confirms that comments relating to cultured meat consumption vary according to the communication perspective of the main post. Consequently, Hypotheses 1 to 4 are verified.

4.3.1. Ethical Framing

The analysis of the “ethical” media frame of cultured meat confirmed that there are differences of attitude in Twitter users’ comments. The multivariate result was significant for the ethical media frame (Wilks’ lambda = 0.999, F = 8.945, df = 3, p = 0.001), indicating a difference in cognitive and affective components between ethically framed posts and posts having no ethical media framing. As a result of this difference, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed. Univariate F-tests show that there is a significant difference in cognitive (p = 0.011) and conative (p = 0.001) components between ethically framed posts and posts that are free of media framing (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of variance of the different types of media framing.

Table 2 presents the results of the univariate F-tests obtained using SPSS 29.0.0.0 software, as well as their levels of statistical significance.

The contrast results (K matrix) reveal that Twitter users’ comments (cognitive, affective, and conative) on posts with “ethical” media frames differ depending on whether their response is cognitive (0.022, p = 0.011) or conative (0.035, p = 0.001) (partial eta squared = 0.001).

4.3.2. Intrinsic Media Frame

An analysis of the multivariate results for posts with an “intrinsic” media frame and those with no media framing shows a significant difference in user responses (Wilks’ lambda = 1; F = 3.346; df = 3, p = 0.018). Therefore, these results indicate that the means of cognitive, affective, and conative attitude components generated by comments differ for posts with an intrinsic media frame and posts free of media framing. This result confirms Hypothesis 2, which posits that the intrinsic media frame influences each component of attitude. Univariate F-tests showed a significant difference in the affective component (p = 0.010) between posts with an intrinsic media frame and those without framing.

The contrast results (K matrix) reveal that Twitter users who commented on tweets with an intrinsic media frame expressed more affective reactions (0.019, p = 0.010).

4.3.3. Informational Media Frame

Regarding the comparison between posts representative of informational media framing and posts with no media framing, the multivariate results were significant (Wilks’ lambda = 0.996, F = 34.046, df = 3, p = 0.001), indicating a difference between the cognitive, affective, and conative attitude components for the informational media frame; hence, the results support Hypothesis 3.

The univariate F-tests showed a significant difference between posts with an informational media frame and posts without media framing for the cognitive (p = 0.001) and conative (p = 0.001) attitude components. This indicates a difference in cognitive and conative comments to posts containing informational determinants of cultured meat.

The contrast results (K matrix) reveal that Twitter users who commented on posts with an informational media frame expressed more cognitive reactions (0.057, p = 0.001) and conative reactions (0.061, p = 0.001; partial eta squared = 0.004). In conclusion, intrinsic media framing influences consumer attitudes, particularly the cognitive and conative components.

4.3.4. Belief Media Frame

There is a difference between Twitter posts exhibiting a belief media framing and posts without media framing in terms of the cognitive, affective, and conative components of attitude. Table 1 shows that these results are significant (Wilks’ lambda = 0.999, F = 10.772, df = 3, p = 0.001), indicating a difference between the two belief media frame groups (framed and non-framed). Univariate F-tests indicated a significant difference between posts conveying belief media framing and posts characterized by an absence of media framing for the affective (p = 0.002) and conative (p = 0.001) components of attitude.

The contrast results (K matrix) reveal that Twitter users responding to posts defined by a belief media frame expressed significantly more affective comments (0.023, p = 0.002) and conative comments (0.035, p = 0.001) than users responding to posts characterized by other media frames (partial eta squared= 0.001). These results allow us to deduce that the belief media frame influences consumer attitudes, particularly the affective and conative components thereof, thus supporting Hypothesis 4.

In fact, all the attitude component variables (cognitive, affective, and conative components of attitude) vary according to the type of media framing. This confirms all four research hypotheses. This means that the four media frames (media framing theory) have been identified across the four groups of ambivalent determinants (ambivalence theory). The consumers’ choices based on ambivalent determinants stem from the random utility theory, which posits that the consumer’s product choice depends on the benefits they can maximize through the characteristics of their choice. Thus, through the results of the analysis, these four media frames (ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief) have demonstrated their influences on each of the components of attitudes (three-dimensional theory of attitude), thereby confirming each of the four research hypotheses derived from the theoretical framework.

Figure 2 shows the results of analyzing the means of each attitude component according to the media framework.

Figure 2.

Attitude components according to media frame.

5. Discussion

A comparative analysis of the means for each media frame (Figure 2) shows that posts with an informational frame (curiosity, food neophobia, regulation, and conspiratorial ideation around cultured meat) generate Twitter user comments with a higher mean (0.63) for the cognitive component of attitude. These results are consistent with those reported by Siddiqui et al. [16,20], who argue that the inhibiting barriers mentioned by consumers, including lack of naturalness, safety, and trust associated with regulation, as well as neophobia, are used as marketing strategies to directly address these concerns [20,58]. There are several reasons why these results align with findings from previous studies. For example, informationality is defined as the first reaction that consumers have after receiving information about cultured meat. These reactions are particularly important in the field of food products [21,24] since they create the “Halo effect”. Indeed, Tuorila and Hartmann [24] highlighted the importance of consumers’ first impressions of cultured meat, believing that consumers’ thoughts are revealed in their attitudes through their food curiosity or their fear resulting from food neophobia. This information therefore contributes to consumer learning as well as the formation of their cognition with regard to cultured meat.

In contrast, technological framing has been found to elicit negative associations and significantly reduce behavioral intentions to consume cultured meat [33,59]. These results are consistent with those of previous studies and can be explained by the fact that the use of advanced technologies in the manufacturing process of cultured meat causes a certain distrust of food technologies among consumers. Many authors compare this distrust to those that arose during the marketing of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) [24].

The results regarding the affective component of attitude show that posts characterized by informational (0.26) and ethical (0.25) media frames generate the largest number of affective reactions to cultured meat. This is concurrent with a number of other studies, suggesting that it is the informational determinants, i.e., initial information received by consumers, that influence their cognition and, therefore, knowledge about cultured meat [21,24,49,60]. Ethical media framing, emphasizing environmental and animal welfare benefits, can induce positive feelings and stimulate consumer intentions to buy insects and cultured meat [34,61]. There is also evidence that advertisements promoting healthy and environmentally friendly food consumption can prompt a behavioral shift toward sustainable diets [59,61]. Other recent studies have suggested partly similar results, confirming that a sustainability-based word association exercise revealed that the consumer response to cultured meat was dominated by affective rather than cognitive factors [21,58]. However, studies among meat producers have shown that beliefs regarding the environmental friendliness associated with cultured meat are not associated with a willingness to consume such meat [12]. However, these results are not contradictory to those of our study, which suggest that the conative component of the attitude is much more marked by the factors of moral and religious beliefs, while the affective component is more characterized by the ethical factors associated with the sustainability and the well-being of humans and animals [21]. Thus, based on the results of the work of Lin-Hi et al. [17], opinions regarding the environmental friendliness of meat alternatives other than cultured meat do not appear to play an important role in determining consumers’ behavioral intentions. This is not surprising given recent research showing that health is the main motivation for adopting a low-meat diet [17,62]. However, there are other results in the literature regarding the impacts of ethical factors on consumer attitudes. Indeed, several recent studies on “green consumption values” describe the impact of an individual’s personal ecological and environmental values on their consumption and purchasing behavior [11,17,62]; strong environmental concern has been found to contribute to sustainable consumption behavior among German consumers [15,63]. This difference could be explained by the socio-cultural specificities [64,65] of the respondents and their level of prosocial engagement [13]. For example, several other studies have also shown that Western consumers are not willing to reduce their meat consumption [17,66], but are increasingly concerned about the implications of meat on sustainability and animal welfare [17,67]. This type of consumer is likely to adopt cultured meat over other meat alternatives given the resemblance between cultured meat and conventional meat in terms of intrinsic attributes [10].

An analysis of the conative component of attitude expressed in the comments shows that posts with a belief media frame generate the largest number of behavioral reactions (conative mean = 0.24). Although most studies suggest that beliefs influence meat consumption behavior in general and cultured meat consumption in particular, none of them have investigated the level of impact beliefs have on consumer behavior. Moreover, it has been found that there is less evidence of the effectiveness of interventions targeting beliefs and sociocultural factors such as social norms [68]. Our study results are noteworthy for showing that cultured meat consumption is also strongly dependent on the extent of consumers’ religious and cultural beliefs, in particular, morality and religious and cultural conservatism. In this regard, they align with the findings reported by Bryant et al. [29] and Kouarfaté et Durif [21].

Furthermore, a descriptive analysis of the results shows that Twitter posts combining the intrinsic, informational, and belief determinants trigger the highest averages (cognitive = 0.71 and overall attitude = 0.43) of Twitter user reactions. However, the joint effect of the intrinsic and belief media frames in Twitter posts provoke the highest averages of affective replies (0.30). As for the highest conative response averages (0.39), they are the result of combined ethical, informational, and belief determinants. It can be inferred from this finding that identifying a dominant group of determinants per attitude component (cognitive, affective, and conative) and then combining these three determinants in a message or post would trigger a stronger overall attitude in consumers. This is consistent with the findings of the study by Kouarfaté and Durif [21].

Finally, the results of this study, based on a sample that uses Twitter, cannot be extrapolated to the general population of Canada. Indeed, other studies show different perceptions [17,21], which deserve to be considered in a critical scientific analysis.

6. Limitations

It should be noted that this research was based on conversations on the social media platform Twitter, where posts are limited to 280 characters, forcing individuals and organizations to use a limited vocabulary. However, this constraint compels Twitter users to choose their vocabulary with care and constitutes an advantage insofar as we can assume that they use precise wording, hence the reliability of the keyword dictionary, which was created for analysis purposes [55,69].

Another limitation is related to the nature of the tweet sample and the conversion of variables based on the keyword dictionary. Although the keyword list is derived from the measurement scales identified in the literature, these words may not capture all the variables to the extent that Twitter users also employ analogous words. Nevertheless, a preliminary analysis was carried out and made it possible to identify these synonyms in the sample of tweets. In addition, this method has been used by several other authors (e.g., [55,70]). The study conducted by Chicoine et al. [55] demonstrated the potential of using social media and the lexicon-based approach in research addressing a natural phenomenon, such as the textual traces of social media users. According to them (p. 14), “The transformation of the frequency of words into data makes it possible to carry out statistical analyses, in particular, to see the divergences in valuation or image between the stakeholders of an industry, as is the case of the local food system”.

Finally, the researchers could not ascertain whether each comment was linked to a regular account or an automated, i.e., bot account [43]. According to Broniatowski et al. [71], bots are automated accounts that can be designed to disseminate misinformation and content on a topic. However, in their study, Yuan et al. [72] found that only 1.45% of the accounts involved in vaccine discourse on social media were bots.

7. Contributions and Research Avenues

7.1. Practical and Managerial Contribution

The results of this research reveal that the four media frames do not have the same impact on all the attitude components, which confirms the existence of a group of “dominant” determinants (see Kouarfaté et Durif [21]) for each component of attitude. In the practical and management field, this opens up the prospect of effective communication techniques for marketing and communication specialists insofar as our findings provide a better understanding of the determinants that they will have to focus on in order to increase the effectiveness of their advertising message. In fact, this concurs with the recommendations put forward by Goodwin and Shoulders [31], Dilworth and McGregor [32], and Bryant and Dillard [33] in relation to the combination of determinants and or images chosen for product messaging, as well as with the recommendations of Kouarfaté and Durif [21], particularly with regard to the application of the simultaneous actions theory of dominant determinants for each attitude component in an advertising message. By identifying the specific impact of informational framing on the cognitive component, this study contributes by providing companies with information that will allow them to achieve the objectives of notoriety of cultured meat on social networks.

At the social level, this study has shown the importance of the informational frame on Twitter users’ cognition and attachment regarding cultured meat, particularly in relation to the issue of regulation. Concretely, this study makes it possible to achieve the specific objectives brand attachment by publishing on social networks, information which makes it possible to create curiosity around cultured meat and, above all, by avoiding messages highlighting the characteristics of new cultured meat. Other studies have also shown that the level of acceptability of cultured meat is correlated with the trust generated by product manufacturing and consumption-related regulations [2,68]. Therefore, one of this study’s contributions is to bring to the forefront the importance of regulation in the cultured meat sector and to bring to the attention of government and administrative authorities the need for legislation and market regulation in order to increase trust in start-up producers.

Finally, in concrete terms, the study proposes the following strategies to various stakeholders (companies, competent authorities, and various associations):

- -

- For the objectives of raising awareness about cultured meat, stakeholders should opt either for publications relating to the sustainability characteristics of cultured meat, which can arouse curiosity among Internet users, or for publications emphasizing the fact that the cultured meat sector will be well regulated and supervised to gain the trust of Internet users. However, stakeholders must avoid publications relating to the disgust associated with food neophobia, as well as to those relating to conspiracies.

- -

- For the purposes of increasing affection for or attachment to cultured meat, stakeholders should publish messages on social networks that describe both sustainability characteristics and information on the regulations of the cultured meat sector. However, stakeholders should avoid messages about the “unnatural” nature of cultured meat.

- -

- For the purposes of purchasing and consuming cultured meat, stakeholders should publish messages explaining that the production and consumption of cultured meat will take into account the rituals, prohibitions, and specific dogmas of each religion.

- -

- For general attitude objectives, these messages should combine a single element of each of the following determinants: intrinsic, informational, and belief. For example, short messages should highlight the “best taste”, “regulation of the sector”, and the adaptation of meat cultivated to the principles of different religions.

7.2. Theoretical Contributions and Research Avenues

Scientifically and methodologically, this study contributes to filling a research gap in the emerging field of food technology, highlighted by Goodwin and Shoulders [31] and Dilworth and McGregor [32], namely, the media framing of cultured meat across countries and media types. For example, this study provides researchers with a mechanism for understanding how to use the determinants of meat alternatives in general in student and public education campaigns. Another contribution of this study is highlighting the importance of belief determinants [73] in forming behavioral attitudes (conative component). It opens up avenues for promising research, such as assessing the impact of culture and/or religion on cultured meat purchasing and consumption behavior.

Moreover, conducting a similar study using data from another social media platform, such as Facebook, would also provide valuable insight, as would a comparative study of media framing on Twitter and Facebook and their respective impacts on consumer attitudes toward cultured meat. According to a number of researchers, it is likely that social media users who comment on posts related to specific issues, such as vaccines [43,74] and cultured meat, are very ill-disposed to these products. In this vein, another line of research would be to specifically study the extent of negative comments about cultured meat on social media. Other avenues of research considering prosocial behavior and the eco-emotions of consumers could be explored in order to measure the impact of this type of behavior and/or emotions on the acceptability of cultured meat. Finally, other media framing on the issue of price, packaging, and/or stakeholders involved in the production and marketing of cultured meat could be the subject of future studies.

8. Conclusions

The future of cultured meat is emerging as a solution to the complex challenges of the conventional meat industry. The potential benefits in terms of nutritional intake, sustainability, environmental protection, and human and animal well-being are undeniable. However, significant issues remain to be overcome, including the technical, regulatory, and social acceptability of this meat within the population. In order to solve the social acceptability challenge, media, especially social media platforms, play a vital role in shaping public opinion on the subject. Thus, the different determinants of cultured meat summarized in the media framing of cultured meat, whether focused on ethics, intrinsic characteristics, information, or beliefs, exert a notable influence on consumer attitudes and decisions. This study examined the impact of Twitter post media framing on user comments and reactions regarding cultured meat. It identified and evaluated several significant differences in consumer attitude components based on 23,020 Twitter posts and 38,531 comments. Using a keyword dictionary for the determinants of cultured meat and the components of consumer attitudes, this study shows that media-framed Twitter posts had a greater influence on consumer attitudes than posts that were not media-framed. Moreover, this study shows that media-framed posts influenced consumer attitudes more than non-media-framed posts. Although the results indicate that the different types of media framing (ethical, intrinsic, informational, and belief) do not exert the same influence on each attitude component, they suggest that posts combining the ethical, intrinsic, and informational media frames have a greater impact on the acceptability of cultured meat and that the belief frame is equally important, particularly for the behavioral component. Relevant implications can be drawn for authorities and businesses on using differentiated education and marketing strategies. Thus, this study makes it possible to fill the existing gaps in the literature by answering the research questions posed as to whether each publication about cultured meat on Twitter generates different consumer attitudes depending on the media frame and whether these differences impact each component of attitude, as well as purchasing and consumption behavior. It also makes several specific contributions, including how to guarantee the acceptability of cultured meat on social networks. For example, one of the answers to our posed questions suggests that concerned stakeholders should publish short messages highlighting both the “best taste of cultured meat”, “the regulation of the sector”, and the consideration of the dogmas and rituals of each religion in the process of production and consumption. It therefore makes it possible to identify the best communication techniques (media framing) that have the greatest influence on the components of online consumer attitudes (Twitter).

Finally, through this study, a strong call for action is launched towards government authorities through suggesting to them the urgency of regulating the cultured meat sector by voting for laws that govern the production and consumption of this type of meat.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su152416879/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.K. and F.D.; Methodology, B.B.K. and F.D.; Software, B.B.K.; Validation, B.B.K. and F.D.; Formal analysis, B.B.K. and F.D.; Investigation, B.B.K. and F.D.; Resources, B.B.K. and F.D.; Data curation, B.B.K.; Writing—original draft, B.B.K. and F.D.; Writing—review & editing, B.B.K. and F.D.; Visualization, B.B.K. and F.D.; Supervision, B.B.K. and F.D.; Project administration, B.B.K. and F.D.; Funding acquisition, F.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council] grant number [Durif_Fabien_430_2021]. And The APC was funded by [Author Voucher discount code (c80189ed7fc6a7bb)].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://susy.mdpi.com/user/manuscripts/review_info/e7ae995b4d7c919d809675639191e8f1. In Supplementary File: manuscript-supplementary.xlsx. This data is also accessible to the general public on Twitter.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1 represents the number of tweets extracted by category and according to the language of communication. These tweets were extracted using R 4.2.0 software.

Table A1.

Data collection and cleaning.

Table A1.

Data collection and cleaning.

| Type of Tweet | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Tweets Extracted | Quoted Tweets | Reply Tweets | Retweets | Duplicates | Main Tweets Selected | Quoted Tweets Selected | Retweets and Reply Tweets Selected | |

| English | 153,727 | 3249 | 27,273 | 102,686 | 96,681 | 7611 | 1222 | 48,213 |

| French | 12,023 | 331 | 2509 | 8247 | 7517 | 239 | 137 | 4129 |

| Total | 165,750 | 3580 | 29,782 | 110,933 | 104,198 | 7850 | 1359 | 52,342 |

The analysis of posts and comments using R.4.2.0 software made it possible to display Figure A1 and Figure A2 (in the Appendix A), thus showing the number of times that each keyword in the dictionary was used in the posts (keywords that define each media frame) and in the comments (keywords that define each attitude component).

Figure A1.

Attitudes expressed in Twitter user comments (English and French).

Figure A2.

Media framing of English- and French-language Twitter posts.

Table A2 shows the entire list of keywords by variable (attitude component and framing). This set, called the “Keyword Dictionary”, is derived from the “items” that constitute the measurement scales of each variable in the literature, as well as their authors and level of reliability (Cronbach’s alpha). In addition, other analogous and frequent keywords identified in the analysis of publications and comments were added to the last column of Table A2.

Table A2.

Keyword dictionary derived from measurement items used to capture the variables.

Table A2.

Keyword dictionary derived from measurement items used to capture the variables.

| Variables | Keyword Dictionary Derived from Measurement Items Drawn from the Literature | Keyword Dictionary of Frequently Occurring Analogous Words |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude component variables | ||

| Cognitive component [75], α = 0.94 | Useful/useless, sensible/senseless, sure/unsure, beneficial/harmful, worth/worthless, perfect/not perfect, healthy/dangerous | Diet, safety, bad, know, safe, curious, curiosity, aware, information, propaganda, taught, diseases, fake, true |

| Utile/inutile, sensée/insensée, sûre/non sure, bienfaisant/nuisible, valeur/sans valeur, parfaite/non parfait, saine/dangereuse | Wrong | |

| Affective component [75], α = 0.93 | Like/hated, delicious/disgusting, soothing/annoying, cheerful/sickening, relaxed/nervous, accept/refuse, happy/sad, festive/boring | Love, agree, enjoy, fun, juicy, sentient, glad, dirty |

| Aime/détesté, délicieuse/dégoûtant, festive/ennuyeuse, apaisante/énervant, enthousiaste/écœurant, détendu/énervé, accepter/refuser, joyeux/triste | ||

| Conative component [25,26,33], α = 0.894 | Try/give up, eating/vomiting, buy/do not buy, recommend, dissuade, discourage | Discount, purchase, paid, shopping, testing, prize, consumed, pay, bought |

| Essayer/renoncer, manger/vomir, acheter/ne pas acheter, recommander/déconseiller, dissuader | ||

| Framing variables | ||

| Ethical framing | ||

| Animal welfare or vegetarian/animal abuse, ethical/natural, protects/against the environment, disrespectful to nature, respectful of the environment, climate change Bien-être animal/maltraitance des animaux, éthique/naturel, protège/contre l’environnement, irrespectueuse envers la nature, respectueuse de l’environnement, changement climatique | Plant, diet, green, land, emission, destroy, cruelty, methane, deforestation, pollution, carbon, suffer, energy, gas, slaughtering |

| Unnatural cells, unnatural, against nature | Wild, GMO |

| Cellules non naturelles, non naturel, contre nature | ||

| Intrinsic framing | ||

| Healthy, contaminated, nutrient, nutritious, good for health, healthy eating, taste | Protein, foods, alternative, texture, nutrition, vitamin, flavor |

| Sain, contaminé, nutriment, nutritifs, bon pour la santé, alimentation saine, goût | ||

| Absence of antibiotics, sanitary condition, absence of hormones | Gluten, clean meat, clean, chemical, safety, food hygiene |

| Absence d’antibiotique, conditions d’hygiène, absence d’hormones | ||

| Disgusting, impure, unsanitary | Medical, contamination, delicious, health, sick, bacteria, cancer, toxic |

| Dégueulasse, impur, insalubre | ||

| Technology, gene technology, fear of new technologies | Biotech, tech, startup, science, GMO, labora, meatech |

| Technologie, technologie génétique, peur des nouvelles technologies | ||

| Informational framing | ||

| Love the novelty, to know, know what I eat | Try, test, innovation |

| Aime la nouveauté, savoir, savoir ce que je mange | ||

| Regulation, control, sanctioning non-compliance | Processed, FDA, drugs, corruption, freedom, USDA, DNA, illegal |

| Réglementation, contrôle, sanctionner le non-respect | ||

| Lack of confidence, fear of novelty, I fear | |

| Manque confiance, peur de la nouveauté, je crains | ||

| Powerful Group, New World Order, conspiracy, conspiracy, complicity | Bill, billgates, rich |

| Groupe puissant, Nouvel Ordre Mondial, conspiration, complot, complicité | ||

| Belief framing | ||

| Good actions, fair, loyal, respecting decisions, pure actions | God, halal, religious, moral |

| Bonnes actions, équitables, loyal, respecter les décisions, actions pures | ||

| Changement, habituel, conservatisme, libéral | |

| Change, usual, conservatism, liberal |

Note: Bold characters mean titles.

Table A3 represents a summary of the content analysis of the tweets. These are quotes from comments on posts related to cultured meat based on a cross-analysis of the four themes and each attitude component.

Table A3.

Quotations of comments on cultured meat-related posts based on a cross-analysis of the four themes and each attitude component.

Table A3.

Quotations of comments on cultured meat-related posts based on a cross-analysis of the four themes and each attitude component.

| Framing | Sub-Themes | Twitter User Posts and Comments According to Media Frames and Attitude Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Affective | Conative | ||

| Ethics | Sustainability Unnaturalness | Post: “Lab-grown meat and insects ‘good for planet and health’#LabGrownMeat #Insects #ClimateChange #Environment #Food https://t.co/7h3Dwmu63l (accessed on 12 November 2022)” | Post: “IMO, lab-grown meat is 100% the solution to scaling up meat production while reducing carbon footprint, water and land usage. https://t.co/PIydxUqaVI” | Post: “je pense que des solutions comme la viande cultivée serais beaucoup plus acceptable que de mutiler des animaux... https://t.co/rjWFSdhdZy” |

| Comment: “It’s sometimes used as a meat substitute because the texture is similar, you make it by washing flour, which as a concept is hilarious.” | Comment: “to be my happiest self because the overpriced locally grown and fair trade meat substitute that I buy religiously is seventy-five percent off”. | Comment: “La diminution de la consommation de viande “naturelle” ne s’est pas faite sans l’aide de la viande de culture de plus en plus populaire. Les terres utilisées pour élever/nourrir les animaux d’élevage retournent progressivement à l’état sauvage. 16/” » | ||

| Intrinsic | Nutritional value and flavor Absence of chemicals Health concerns Mistrust of biotechnology | Post: “Sia Invests in Pet Food Made from Cultured Meat https://t.co/hwhX6ez8HJ”. | Post: “BioTech: the marketing of synthetic meat has already begun! Vincent Held—Liliane Held-Khawam’s blog https://t.co/HB3LjQTOkg”. | Post: “Brave new bird: Tasting chicken grown in a lab from chicken cells. https://t.co/cb7AgQ4uPX”. |

| Comment: “Perhaps meat from animals. I bet lab-grown meat from animal cells that are sourced without significant harm to the animal will eventually be the norm”. | Comment: “mais ya pas le choix, j’aime la viande et j’suis pas en capacité de faire ma propre viande, donc bon.” | Comment: “Disturbed Earth to animals in order to fatten them up for ‘meat’, but it we could produce enough food to feed the entire world. Also there are options, synthetic meat produced in the lab from animal protein that does not require any cruelty, or if so not a huge% like today in factory farming” | ||

| Informational | Curiosity Regulation Neophobia Conspiratorial ideation | Post: “DYK cellculturedmeat is often produced in large vats of fetal calf serum? Or from cells known to cause cancer? Tell @USDA to institute strong regulations of cell-cultured ‘meat’ before this new industry weakens them! https://t.co/rHhwAfStUW @CFSTrueFood” | Post: “Lab-grown meat firms say post-Brexit UK could be at forefront Technology, touted as low-carbon, faces long regulation process in EU but industry hopes UK will expedite approval https://t.co/54uy1OPNMR” | Post: “Please weigh in! Is lab grown/cell-based /cultured /meat vegan? https://t.co/5tBNKSRep7” |

| Comment: “Whether it’s new foods like jellyfish, edible insects and cell-based meat, or new technologies like blockchain, artificial intelligence and nanotechnology, the future promises exciting opportunities for feeding the world, according to a new report https://t.co/byZw3qcZ9c https://t.co/wWYxN2BUgM” | Comment: “Redefine Meat is applying proprietary 3D printing technology, meat digital modeling, and advanced food formulations to produce animal-free meat with the appearance, texture and flavor of whole muscle meat. Video source. https://t.co/UlXFu3tM0l” | Comment: “Eating organic, clean red meat is one of the most nutritious food sources there is”. | ||

| Belief | Morality Conservatism | Post: “Cultured meat is now being mass-produced In Israel https://t.co/pwaHOJEuS2”. | Post: “Cultured meat is now being mass-produced In Israel https://t.co/pwaHOJEuS2 #Halal #meat is known to be clean, #nutritious, and has several health benefits. Here are some viable reasons to consume it in your daily diet. #Order it online from #HalalBox. To Know More, Read the complete blog here—https://t.co/3zgYaADiHC”. | Post: “Cultured meat is now being mass-produced In Israel https://t.co/pwaHOJEuS2”. |

| Comment: “IDK about lab-grown meat & am only just starting to learn about nuclear, but I know a fair bit abt dense cities (towns) & they’re BY FAR the most time-tested way for humans to live, crucially, to thrive. We’re social critters, we don’t do well in isolated burbs & farms” | Comment: “I think the sad part is imma get stretched out by an artificial dildo instead of real meat -___- that’s super sad” | Comment: “If it tastes as good as milk, and is just as nutritious, I’d try it. Especially once the cost comes down. I’m all for synthetic meat, and eggs, and dairy, if we can really make stuff that’s just as nutritious and tasty as the real thing”. | ||

References

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A Systematic Review on Consumer Acceptance of Alternative Proteins: Pulses, Algae, Insects, Plant-Based Meat Alternatives, and Cultured Meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.M.; Teixeira, O.D.S.; Revillion, J.P.; Souza, Â.R.L.D. Panorama and Ambiguities of Cultured Meat: An Integrative Approach. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5413–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling Consumers Who Are Ready to Adopt Insects as a Meat Substitute in a Western Society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations Unies. Nations, Unies Population. Available online: https://www.un.org/fr/global-issues/population (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Choudhury, D.; Singh, S.; Seah, J.S.H.; Yeo, D.C.L.; Tan, L.P. Commercialization of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Tomiyama, A.J. Would You Eat a Burger Made in a Petri Dish? Why People Feel Disgusted by Cultured Meat. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, C. Lab-Grown Meat and Veganism: A Virtue-Oriented Perspective. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ Associations, Perceptions and Acceptance of Meat and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Sun, J.; Lin, W. Identity Labels as an Instrument to Reduce Meat Demand and Encourage Consumption of Plant Based and Cultured Meat Alternatives in China. Food Policy 2022, 111, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M.; Dean, D.; Vriesekoop, F.; De Koning, W.; Aguiar, L.K.; Anderson, M.; Mongondry, P.; Oppong-Gyamfi, M.; Urbano, B.; Gómez Luciano, C.A.; et al. Is Cultured Meat a Promising Consumer Alternative? Exploring Key Factors Determining Consumer’s Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Premium for Cultured Meat. Appetite 2022, 179, 106307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, F.S. Cultured Meat and the Sustainable Development Goals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, K.; Piqueras-Fiszman, B. Consumers’ Perception of Cultured Meat Relative to Other Meat Alternatives and Meat Itself: A Segmentation Study. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, A91–A105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakseresht, A.; Ahmadi Kaliji, S.; Canavari, M. Review of Factors Affecting Consumer Acceptance of Cultured Meat. Appetite 2022, 170, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, D.; Humbird, D.; Dutkiewicz, J.; Tejeda-Saldana, Y.; Duffy, B.; Datar, I. Cultured Meat Needs a Race to Mission Not a Race to Market. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, J.; Harms, T.; Fiebelkorn, F. Acceptance of Cultured Meat in Germany—Application of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2022, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Khan, S.; Murid, M.; Asif, Z.; Oboturova, N.P.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Blinov, A.V.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Jafari, S.M. Marketing Strategies for Cultured Meat: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Reimer, M.; Schäfer, K.; Böttcher, J. Consumer Acceptance of Cultured Meat: An Empirical Analysis of the Role of Organizational Factors. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 93, 707–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.-F. Is in Vitro Meat the Solution for the Future? Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.; Brown, C.; Arneth, A.; Dias, C.; Finnigan, J.; Moran, D.; Rounsevell, M.D.A. Could Consumption of Insects, Cultured Meat or Imitation Meat Reduce Global Agricultural Land Use? Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 15, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Khan, S.; Ullah Farooqi, M.Q.; Singh, P.; Fernando, I.; Nagdalian, A. Consumer Behavior towards Cultured Meat: A Review since 2014. Appetite 2022, 179, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]