Abstract

Transit-oriented development has gained global attention as a sustainable urban planning approach. However, its implementation in developing countries, particularly in the Middle East, remains underexplored. This study aims to investigate the challenges and opportunities facing private developers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in the context of delivering TOD projects. Using a mixed-methods approach that combines survey data and interviews, the research explores four key dimensions: regulatory, structural, collective vision, and economic factors. The findings reveal a complex local environment characterized by both encouraging prospects and formidable challenges. Institutional coordination, procedural clarity, and timely approval emerge as critical challenges in the regulatory dimension. Land-related issues, including land amalgamation and fragmented ownership, are identified as significant structural obstacles. While there is general enthusiasm for TOD among private developers, the lack of effective public–private collaboration and a unified vision hampers progress. Economically, high initial investments and regulatory uncertainties are the main challenges, although there is cautious optimism for future profitability. Despite these challenges, the study unveiled policy implications for implementation and offered information for context-specific adaptive planning. The research contributes to the growing body of literature on TOD in developing countries and lays the groundwork for future multistakeholder studies.

1. Introduction

Riyadh, the capital and largest city of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, has experienced rapid urbanization and population growth in recent decades [1], leading to significant challenges in urban development and transportation [2]. Saudi Arabia is considered one of the most urbanized countries in the world, and Riyadh’s expanding population, coupled with increased private vehicle ownership and reliance on conventional transportation modes, has resulted in congested road networks, prolonged commute times, and increased carbon emissions [3]. Additionally, Riyadh’s urban sprawl and separated land use patterns have led to increased dependence on private vehicles, exacerbating traffic congestion and air pollution [4]. To address these pressing issues, the world’s most expensive public transport system, the King Abdulaziz Project for Riyadh Public Transport, a metro transport network comprising 6 train lines, 85 stations, and 80 bus routes, is being built [5]. Consequently, Riyadh planners are embracing transit-oriented development (TOD) as a promising approach that emphasizes the integration of land use and transportation planning to create a more sustainable, efficient, and livable city.

TOD has gained significant importance in addressing the urbanization and mobility needs of cities in developed nations and increasingly so in developing countries [6,7], including Saudi Arabia. As cities around the world experience rapid population growth and urban expansion, the demand for efficient and sustainable transportation solutions becomes imperative. In the context of Riyadh, where urbanization and mobility challenges are prevalent, the role of private developers in the implementation of TOD projects becomes crucial. Private developers contribute their expertise, resources, and innovative approaches to shaping urban environments that prioritize transit accessibility, walkability, and livability [8]. Given the significant role that private developers play in contributing to the success of a public transport initiative [9], their participation and support are essential for achieving successful and sustainable urban development. As the opening of the Riyadh metro system approaches, it is timely to explore what private developers need to be actively involved in TOD projects.

This research aims to address the problem of limited knowledge about the participation of private developers in TOD projects, using Riyadh as a case study. By concentrating on Riyadh, a city forming its TOD landscape, the study fills a critical gap in the existing literature, which has primarily focused on TOD in developed countries. The study provides empirical information on the experiences and perspectives of private developers in Riyadh, a group that is not represented in TOD research. By capturing their engagement with new TOD opportunities, the research adds depth to our understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by these key stakeholders in the TOD process. The findings of Riyadh also contribute to strengthening TOD theory. The mixed-methods approach, which combines survey and interview data, offers a comprehensive view of the multifaceted experiences of private developers. This enriches the theoretical framework of TOD and provides a deeper understanding of how TOD is perceived and implemented in a developing country context.

The focus of this study on Saudi Arabia, particularly Riyadh, is timely and relevant. As the city embarks on significant urban development and transportation projects, understanding the role and challenges of private developers in TOD becomes crucial for successful implementation. The insights provided by private developers can be useful for pursuing TOD projects in the future and can also inform policy making and urban planning practices in Riyadh and similar contexts. By highlighting the specific barriers and facilitators for TOD in a developing country, the study provides valuable guidance to urban planners, policymakers, and developers. This includes considerations for regulatory frameworks, incentives for private developers, and strategies for public–private collaboration. Urban planners can utilize the insights from this research to better integrate the perspectives of private developers into TOD planning processes. This can lead to more inclusive and practical urban development strategies that align with the needs and capabilities of key stakeholders.

Although the study is focused on Riyadh, its findings have broader implications. The challenges and opportunities identified in this context can offer lessons to other cities in developing countries embarking on similar TOD initiatives. The study findings can guide policy makers in creating more effective and context-specific policies that address the unique challenges of implementing TOD in any city. By highlighting the potential opportunities for private developers in TOD, the study can encourage greater participation from the private sector. This is particularly important in contexts where public resources are limited and private investment plays a crucial role in urban development.

This research also aims to fill a gap in the existing literature on the role of private developers in TOD in developing countries such as Saudi Arabia. This is in support of Abdi and Lamíquiz–Daudén’s call for research that focuses on further investigating the specificities of TOD in developing countries [6]. Riyadh is currently experiencing significant urban development, with a strong focus on public transportation and TOD. This presents a unique opportunity to study TOD in the rapidly developing urban context of a developing country. Understanding the role of private developers in this context is crucial to the successful implementation of TOD projects.

The areas that this research explores include policy and planning, market conditions, land and urban form, and knowledge and alignment of vision. Little is known about the role of private developers in these areas, especially in the Middle East, and a better understanding of these areas can inform the successful implementation of TOD projects in the context of developed and developing countries.

Thus, the research objectives are as follows:

- Address limited knowledge about private developers in TOD and contribute to TOD theory and practice.

- Respond to calls for more research on TOD in developing countries.

- Explore the role of private developers in Riyadh’s TOD.

- Highlight barriers and facilitators for private developers in TOD projects.

The connection between these objectives and the relevant literature is provided in the contextual and theoretical background section below (Section 1.1).

The central research question to be investigated is: What potential challenges and/or opportunities currently exist for the future delivery of TOD projects by Riyadh’s private developers?

The significance of this research lies in its examination of the role of private developers in the delivery of TOD projects. The scarcity of academic research on TOD in Saudi Arabia underscores the importance of further investigation into supply and other barriers specific to the Saudi context. Based on existing literature on TOD research [6,9,10,11,12], this study uses mixed methods to collect survey and interview data from private developers and captures their engagement with the new TOD opportunities in Riyadh. The findings reveal a complex and multifaceted experience for private developers that strengthens TOD theory and adds value to the existing knowledge that informs the delivery of TODs in both developed and developing countries.

1.1. Contextual and Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Transit-Oriented Development

This section refers to research objectives 1 and 2. Transit-oriented development (TOD) is a sustainable urban planning approach that focuses on creating compact, walkable, and mixed-use communities centered around high-quality public transportation systems [11,13,14,15]. Additionally, TOD aims to reduce car dependency and promote sustainable transportation options by creating well-designed communities that encourage walking, cycling, and the use of public transit [9,16,17]. It is also essential to distinguish between TOD and transit-adjacent development (TAD), which, although located near transit facilities, fails to capitalize on proximity and may not achieve TOD’s goals [10,11,14,18].

TOD is significant in addressing the urbanization challenges facing modern cities today [19,20,21,22]. By integrating land use and transportation planning, TOD promotes sustainable urban growth, reduces car dependency, and improves accessibility for residents [9,23]. Key benefits of TOD include enhanced mobility options, reduced congestion and air pollution, improved quality of life, and increased economic vitality. Highly developed and extensively documented cases of TOD implementation can be observed in several urban centers of developed nations, such as the United States [14,24], Canada [10], Australia [25], Japan [26], China [27], Taiwan [28], and European nations [29,30,31,32]. TOD is also being increasingly pursued in developing countries [6], with recent developments reported from Malaysia [33], Indonesia [34], Thailand [35], Vietnam [36], and Ethiopia [37]. TOD is also increasingly being embraced in the Middle East region, as seen in Qatar [38], the United Arab Emirates [12,39], and most recently Saudi Arabia [40]. This extensive and global implementation of TOD underscores its potential to promote the establishment of prosperous, environmentally sustainable, and habitable communities characterized by efficient transportation infrastructures.

Beyond its urban and social benefits, TOD also plays a crucial role in reducing carbon emissions and combating climate change [14,22]. By promoting compact, mixed-use development and encouraging transit use, TOD contributes to reducing private vehicle trips and the associated greenhouse gas emissions [40,41,42]. Studies have shown that well-designed TODs can significantly lower car ownership rates and increase transit ridership, resulting in reduced energy consumption and a more sustainable transportation system [6,22,33]. The potential of TOD to contribute to sustainable urban development and mitigate climate change makes it a compelling approach for policymakers, urban planners, and researchers.

TODs have gained prominence as a potential solution to transportation challenges in urban areas and to promote sustainable and efficient land use [18,43]. However, Ibraeva et al. [11] note that several challenges hinder the successful implementation of TOD projects across different national contexts, while Knowles and Ferbrache [20] posit that TODs are challenging to implement and maintain and hold a poor record of success. These include high initial investment costs, difficulties in land assembly, and a lack of cooperation and integration between stakeholders. The problems and possible solutions encountered in implementing successful TOD projects have been extensively discussed in the literature [6,9,11,44,45]. Perhaps in response to such challenges, the World Bank published a comprehensive guide that brings together knowledge, resources, and tools from across the globe, aimed at facilitating the successful implementation of TODs [46]. Overcoming these challenges requires innovative solutions and supportive regulations. Ibraeva et al. [11] propose specific regulations to facilitate the implementation process. Guthrie and Fan [8] emphasize the importance of regional cooperation and political will in ensuring the successful implementation of TOD projects. Furthermore, Curtis [23] identifies inflexible planning standards and fragmented land parcels as factors that complicate the execution of TOD initiatives. Barriers to implementation encompass institutional and policy issues, which makes it essential to address these impediments comprehensively to realize the potential benefits of TOD [11].

1.1.2. Private Developers

This section refers to research objectives 3 and 4. The significance of private developers in delivering TOD projects in developed and developing countries cannot be overstated. As key stakeholders, private developers play a vital role in shaping the urban landscape and driving the successful realization of TOD initiatives [9,47,48]. Private developers contribute to innovation, efficiency, and market-driven approaches to projects due to their financial resources, knowledge, and entrepreneurial spirit [16,47]. Their involvement ensures the effective integration of transit systems and land use, leading to the creation of vibrant mixed-use neighborhoods around transit hubs. Private developers have the capacity to acquire and assemble land parcels, design and construct high-quality developments, and attract investment and tenants. Much lies in the hands of developers [8], and their active participation facilitates the successful implementation of TOD projects and contributes to a city’s overall urban transformation.

Feldman et al. have recognized supply barriers as a significant impediment to the participation of private developers in TOD projects [10]. These barriers include various factors that hinder the availability and accessibility of resources, land, and opportunities for private developers to participate effectively in the planning, development, and implementation of TOD initiatives. Consequently, the presence of a specific supply barrier can dissuade developers from pursuing projects that are vulnerable to such obstacles. Feldman et al. classified these into financial, political, organizational, structural, and regulatory barriers [10]. They also identified additional factors in their research that did not fit these categories and are not explicitly described in the existing literature on TOD barriers. These unique barriers were centered on a lack of awareness of TOD, consumer demand for TOD, and the importance of vision.

1.1.3. The Local Context

This section refers to research objectives 2 and 3. To effectively engage private developers in TOD projects, it is crucial to consider the importance of the local context, as it is unlikely that an exact model of implementation that worked in one context will work in another. Therefore, it is necessary for local planners and experts to develop context-specific TOD solutions, drawing inspiration from international examples while tailoring them to suit the unique urban forms, political and planning contexts, and cultural preferences of their own region [31]. Effective communication and collaboration among various stakeholders involved in TOD planning are essential to developing a shared regional vision for TOD. Suzuki et al. emphasize the importance of adapting TODs to the local urban context, especially for fast-growing cities in developing countries, and that corresponding to local conditions is imperative for all TOD projects [49]. In further recognition that TODs are not a one-size-fits-all concept, Kamruzzaman et al. stress the need to customize TOD approaches to fit the specific characteristics and requirements of each locality [25].

The Middle East region, including Saudi Arabia, faces unique challenges such as rapid urbanization and a climate that encourages car dependency [12]. Riyadh is a prime example of these issues, with increasing traffic congestion and a culture that encourages high rates of car ownership [1,4]. Saudi Arabia has recently experienced a rapid increase in population, economic growth, motorization, and growing urban sprawl that has caused a considerable increase in traffic congestion, accidents, and longer trip distances [4,50]. Limited public transport and low gasoline prices further exacerbate the problem, leading to increased energy consumption, traffic congestion, pollution, and environmental degradation [1,51]. To address these issues, Saudi Arabia has initiated Vision 2030 [52], which focuses on sustainable urban development and transportation. As part of this vision, the National Transformation Program 2020 aims to improve public transport and encourage the participation of the private sector in TOD projects. The Royal Commission for Riyadh City (RCRC) oversees these projects, and the Riyadh Region Municipality (Amanah) is the local government entity responsible for planning and development permits.

1.1.4. The Riyadh Metro

Saudi Arabia is actively pursuing sustainable transportation solutions, as exemplified by Riyadh’s Metro project, part of the King Abdulaziz Project for Riyadh Public Transport (KAPRPT). Aligned with Saudi Vision 2030, this initiative aims to alleviate challenges such as traffic congestion and rapid urbanization [1]. The Metro, upon completion, will feature six train lines covering 176 km and 85 stations with a daily capacity of 3.6 million passengers. This project represents Saudi Arabia’s largest public transit investment and is seen as pivotal for sustainable urban development.

The extensive Metro network offers significant opportunities for TOD in Riyadh. Its objectives for environmental sustainability resonate with the principles of TOD, such as controlling urban sprawl and promoting green initiatives [40]. While Saudi Arabia is in the early stages of adopting TOD, advances in other Middle East nations indicate the potential benefits of the model [12,38,39,53].

1.2. Conceptual Framework

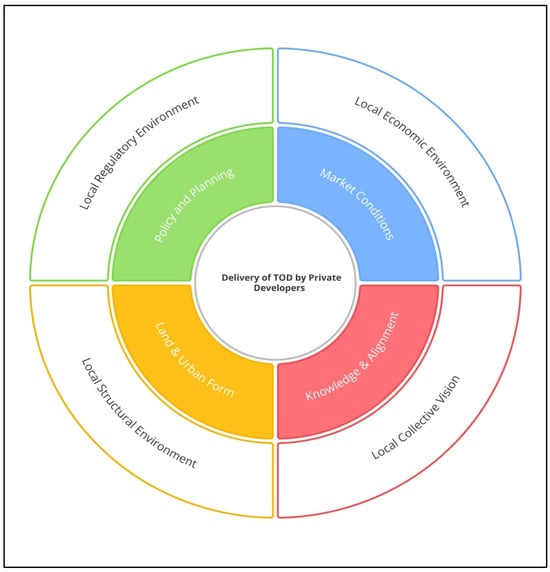

The conceptual framework for this study is drawn from relevant theories and concepts in the reviewed literature and provides a structured interpretive lens to serve as a roadmap, guiding the data collection and analysis process while providing a rationale for interpreting the findings and achieving the research objectives [54,55]. Furthermore, it helps to maintain consistency and coherence in the study, making it replicable and providing a solid foundation for subsequent research in the field. This framework explains the influence of different local contexts on TOD projects, which involves understanding how these contextual factors interrelate and affect the delivery of these projects. It focuses on four main and broad domains: the local regulatory environment, the local structural environment, the local collective visioning, and the local economic environment. These domains are interconnected and dynamic, where changes in one area can have ripple effects in other areas within this network (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for Optimizing Private Developers’ Delivery of Transit-Oriented Development (figure was produced by the authors, 2023).

1.2.1. Local Regulatory Environment

This encapsulates the broader legal and policy environment that affects private developers’ participation in TOD at the local level and includes the complex interplay of laws, regulations, and policies that shape, enable, or constrain participation in TOD initiatives. It also considers the alignment and coordination of local and regional planning strategies with TOD principles, as well as the potential gaps and inconsistencies that may pose challenges to private developers. Within this domain is the subdomain of policy and planning that integrates the regulations, land-use policies, and incentives for TOD that set the local legal framework for private developer participation. This includes zoning regulations, permitting processes, clarity of procedures, incentives, and the organization and integration of various planning and development activities.

1.2.2. Local Structural Environment

This domain assesses the physical attributes of the areas targeted for TOD, taking into account the existing urban fabric. More specifically, the subdomain of land and urban form focuses on the existing physical layout and land issues of the city. This includes land availability, acquisition and development, land ownership patterns, land scarcity, and associated issues such as the integration of private titles and public lands.

1.2.3. Local Collective Visioning

This domain encapsulates the concepts of vision and collaboration and signifies a process in which various stakeholders come together to articulate a shared vision for the future. It considers political, societal, and cultural factors conceptualized as local perceptions that impact the engagement of private developers with TOD projects. In addition, it integrates knowledge and alignment, which captures developer awareness, understanding, and vision for TOD and urban development decisions. These play a role in determining the extent of developer engagement and collaboration with other stakeholders.

1.2.4. Local Economic Environment

This considers broader factors such as the state of the local and national economy and infrastructure, economic trends, the level of infrastructure investment, and the financial capacity and willingness of individual private developers to participate in TOD. The subdomain of market conditions focuses on the local real estate market dynamics, local financial conditions affecting TOD delivery (including local market demand and trends within TOD locations), the availability of financial incentives and options for developers, the local cost of land and construction, and profitability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Guided by similar approaches performed by other researchers [8,9,10,40], this study adopted a two-stage mixed-methods approach. The sample was selected by the Riyadh Chamber of Commerce, which provided a list of 60 developers working in mixed-use development in Riyadh. The link to the electronic survey was sent via WhatsApp to these developers, who were invited to participate. A total of 21 surveys were completed, 14 through WhatsApp and 7 by personal invitation to complete the survey and be interviewed.

The second stage involved conducting semi-structured interviews to combine the structure of the predetermined questions of the survey with the flexibility to explore new areas of discussion [54,56]. The interviews were a multistage procedure of snowball sampling, starting with one developer known to the researchers, who recommended others for further interviews. They were contacted personally and asked to complete the survey, and then the seven interviews took place over a two-month period from May to June 2023. Five were conducted face-to-face at the participants’ offices, while two were carried out via Zoom due to constraints that made in-person meetings impossible.

The comprehensiveness of the interview data is reflected in the depth of the conversations and the range of topics covered. The interviews were conducted as a second stage to obtain further clarifications on the survey questions and provide a deeper understanding of the private developer’s experiences and perspectives about the topics that were asked in the survey. This would not have been captured by only using a quantitative method. The interviews lasted between 35 minutes and an hour, providing sufficient time to delve into detailed discussions. The interviews were recorded in full and transcribed verbatim using Voiser. They were all later translated into English. The transcripts of the interviews amounted to over 70 pages and around 25,000 words. All participants were Chief Executive Officers with substantial experience in the industry (10 to over 15 years), which adds to the depth of insights, although it might limit the perspective to high-level management views. The snowball sampling method was very useful for gaining access to hard-to-reach private developers; however, it may introduce bias as it relies on the network of the initial contacts, and this limitation on the comprehensiveness of the data is therefore acknowledged.

The data collection process provided responses from 35% of the developers surveyed. We acknowledge that this response rate reflects the difficulties in engaging with high-level private developers in Riyadh and may have limitations in terms of representing the findings. The sample was carefully chosen with the collaboration of the Riyadh Chamber of Commerce to include a range of diverse developers of suitable size and resources to be able to participate in TOD projects in Riyadh. However, it may not fully capture all perspectives and experiences within the private development community. This limitation becomes more relevant when considering how applicable the results are to all developers involved in transit-oriented development in Riyadh. To address these limitations, we adopted a mixed-methods approach by supplementing the survey data with in-depth, semi-structured interviews. Although this qualitative component does not completely compensate for the response rate, it provides insight that enriches understanding of the topic. However, it is necessary to acknowledge that any conclusions drawn from this study should be considered indicative rather than definitive. Future research efforts could benefit from strategies aimed at increasing response rates or exploring alternative methodologies to obtain a more comprehensive view of the developer landscape in Riyadh.

2.2. Data Analysis

The use of a weighted mean and standard deviation served as a robust statistical approach for analyzing the survey data. The weighted mean provides for a more comprehensive understanding of central tendency by considering the frequency of responses across the 5 Likert scale categories, thus creating a broader indication of the respondents’ collective opinion [57]. The standard deviation provides information on the dispersion of the responses, which is essential to determining the level of agreement or disagreement among the survey participants [58]. Together, these statistical measures provide a clear view of both the central position and the distribution of the data, making them particularly useful for the study of survey data in urban planning research.

For the weighted mean, each response category on the Likert scale was assigned a numerical value ranging from 1 to 5. ‘Strongly disagree’ was assigned a value of 1, while ‘Strongly agree’ was assigned a value of 5. For each question, the responses were multiplied by their respective weights. The weighted scores for each response category were then summed up to obtain a total weighted score for each question. The sum of the number of responses for each question was calculated. The total weighted score for each question was divided by the total number of responses to that question, producing the weighted mean. This mean reflects the central tendency of the responses, considering the frequency of each response category, and a value closer to 5 indicates the strength of agreement. The weighted mean and standard deviation for the survey data were obtained using XLSTAT software (version 2023.2.1414).

Thematic analysis, a versatile research method used to identify, analyze, organize, describe, and report themes within a data set, was performed on the interview data [59]. The data were organized into the four categories of the conceptual framework, and qualitative NVivo 12 software was used for analysis. Nowell et al.’s process of establishing trustworthiness during each phase of thematic analysis was followed [59]. After multiple manual and electronic interactions, the researchers became intimately familiar with the interview transcripts, resulting in a blending of human and computerized analysis. A rich and detailed understanding of the data was achieved and analyzed.

The survey and interview instruments were carefully designed, drawing on established research methodologies and similar studies in the field [8,9,10,40]. This ensured that the questions were both relevant and comprehensive, addressing the key aspects of transit-oriented development in Riyadh. The conceptual framework, also drawn from the literature, was used for designing and executing the data collection and analysis. To enhance accuracy, we employed data triangulation for the seven interviews, comparing and cross-validating findings from the surveys with insights from the semi-structured interviews. This approach allowed us to identify the consistency in the patterns and themes that we identified. In terms of analytical consistency, the data analysis was performed using systematic methods. For qualitative data, thematic analysis was used, which ensured consistent and replicable interpretations of interviews. For the quantitative survey data, recognized statistical methods were used to analyze the responses, further validating the findings. The preliminary findings were periodically reviewed by another expert in the field of urban development, providing an external check on the precision and relevance of the data and interpretations. Collectively, these procedures helped to guarantee the accuracy and efficiency of the data gathered, thus enhancing the reliability of the study’s results.

3. Results and Discussion

The survey data and interview results provide a comprehensive view of the challenges and opportunities of TOD for private developers in Riyadh and are presented and discussed within the conceptual framework. The weighted mean and standard deviation are used to measure how local developers perceive factors that influence TOD in Riyadh. Interpreting these weighted values depends on the context of each factor being assessed. The weighted mean values, obtained from a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 means disagree and 5 means strongly agree), should be interpreted considering each factor. A higher weighted mean indicates agreement among respondents regarding that factor, while a lower mean suggests less agreement. When it comes to factors that are considered beneficial or desirable for TOD, a weighted mean (closer to 5) is considered positive. It shows agreement among developers that these factors have a presence and a positive influence. For example, a high mean value for ‘Interest in TOD’ (4.19) suggests that there is agreement among developers about the interest in TOD, which is a positive sign for development. On the other hand, factors that represent challenges or barriers to TOD implementation with a higher weighted mean are viewed negatively. It indicates that developers strongly agree on the prevalence of these challenges. For instance, a high mean value for ‘Lack of coordination’ (4.14) points out that there is strong agreement among developers regarding this significant issue, which negatively impacts the implementation of TOD.

The standard deviation values show how much agreement there is among the respondents. A lower standard deviation means that the responses were more consistent (less scattered among respondents), indicating a level of agreement among developers regarding that factor. Conversely, a higher standard deviation indicates variation in responses, suggesting that different opinions or experiences exist among the developers.

3.1. Local Regulatory Environment

This domain reflects the legal and policy environment that impacts private developers’ participation in TOD. The selected indicators in Table 1, such as ‘Lack of institutional coordination’, ‘Encouraging development’, and ‘Procedural Clarity’, represent key aspects of the regulatory landscape. They were chosen to capture the complexities of the laws, regulations, and policies that shape TOD initiatives. Indicators within this domain are grounded in the subdomain of policy and planning, focusing on regulations, land use policies, and incentives that set the legal framework for TOD. They were selected to reflect the multifaceted nature of regulatory challenges and opportunities faced by developers.

Table 1.

Weighted mean and standard deviation of the local regulatory environment.

With a weighted mean of 4.14 and a standard deviation of 1.28, the lack of institutional coordination is a significant challenge for private developers. This issue is particularly evident in the relationship between the RCRC and Amanah. Developers have expressed that the disconnect between these two entities has led to delays and inefficiencies in project implementation. This finding aligns with existing academic literature that underscores the complexities of multi-agency coordination in urban development [8,9]. A specific regulatory concern that exacerbates this challenge is the national parking requirements introduced by the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MOMRA). These requirements mandate additional parking spaces in new developments, which appears to be in direct conflict with the principles of TOD. Developer 3 articulated the paradox succinctly, pointing out the inconsistency of investing heavily in metro infrastructure to alleviate traffic while simultaneously mandating additional parking spaces:

“The regulator now wants to reduce the traffic in the city and had invested 86 billion in the metro, then asks for extra parking!!… It doesn’t make sense and the cost became high with this.”

This tension is reflective of broader debates in the TOD literature on the conflict between policy objectives and their implementation [6,10,43]. Developers 5 and 6 added another dimension to this challenge by identifying service providers, such as the National Electricity Company, as particularly problematic. The term “calamity” was used by Developer 6 to describe the ordeal of coordinating with these entities, which further complicates and hinders the planning process.

The developers expressed a need for procedural clarity, as indicated by a weighted mean of 3.0 and a standard deviation of 1.32. In the interviews, developers frequently mentioned the lack of clarity in planning procedures as a contributor to uncertainty. Developer 4 noted that the authorities “have broad lines. They don’t have the details that we were expecting … the developer’s problem is the uncertainty, that he doesn’t know what they will require from him”. It was noted several times that a lack of certainty increases risk, and this was captured succinctly by Developer 7: “Therefore, we say planning regulation is an essential driver in decision-making, so when there is a complete lack of clarity, it affects the degree of risk”. The lack of transparency in planning procedures leads to uncertainty, impacting risk assessment, and profitability.

Several developers highlighted the “case-by-case” nature of TOD project discretionary approvals as a source of uncertainty, as Developer 2 illustrates:

“There is a huge risk because these [TODs] are unknown and unclear projects. You are taking the risk, and if you know that you have the tools that enable you to face or resist the factors in front of you. I mean, for example, as someone enters a battle, I must enter the battle knowing what kind of sword I have. Will I be able to win it or not? With these projects, the unknowns are too many, so does it make sense that I take a risk and I am not fully aware of what I will face? It’s hard, it’s like going into a dark tunnel and you don’t know what you’re going to face. You face a lion, you face a snake, you don’t know what will face you. You enter unequipped with the necessary weapons that allow you to resist or confront this danger in front of you. Uncertainty exists.”

Although developers expressed a preference for a code-based system with clear upfront steps, research suggests that such a system may not be well suited for the complexities of TOD projects, which often require a more adaptive and flexible approach [31,60].

With a weighted mean of 2.57 and a standard deviation of 1.30, the data suggest that timely approval for planning procedures is not being met, which constitutes an additional obstacle for developers. This time challenge is not unique to this study and has been discussed extensively in the literature [8,16,47]. Developer 4 captures the frustration shared amongst developers:

“Also, the clarity of the regulations, so that they dictate it to me in a clear way from the beginning so that I can do things faster. I sit waiting for them and other developers in different projects [non-TOD], who we started at the same time, who have already started the construction work and I am still sitting waiting for 18 months. But we took the responsibility because we have a goal and a vision to achieve but still this is unbearable. I know ten developers who started at the same time as us but now they are finished and handing over the apartments they built, and I am still in the digging stage.”

The developers’ emphasis on procedural clarity and timely approval highlights a larger problem of ambiguous regulations in Riyadh’s TOD landscape. This lack of clarity not only contributes to the uncertainty of the project but also increases the perceived risks associated with TOD initiatives. Developer concerns align with existing literature, highlighting the intricate relationship between regulatory frameworks, stakeholder coordination, and the successful delivery of TOD projects [8,11,20]. The absence of clear guidelines exacerbates the complexities of the regulatory environment, affecting the potential delivery of TOD projects in Riyadh.

These findings suggest several implications for improving the TOD landscape in Riyadh. Establishing standardized and transparent guidelines for TOD projects to provide developers with a clearer understanding of what is expected from them from the outset could certainly be useful in reducing uncertainty and perceived risk for developers. Given the complexities of TOD projects, an adaptive regulatory framework that allows for some flexibility would also be beneficial. This could allow adjustments to be made as projects evolve without compromising the core principles of TOD. Building the capacity of stakeholders, specifically developers and regulators, to ensure that all parties are well informed could reduce misunderstandings and inefficiencies and help streamline the approval process. Regular meetings, information exchanges, or a dedicated online platform are worth considering. The consideration and possible implementation of such measures may improve the procedural clarity of TOD projects, thereby reducing risk and encouraging more robust participation from private developers.

Despite these challenges, developers acknowledged that planning authorities are on a learning curve with TOD projects and that “after they deal with 3, 4, 5, or even 10 projects with good developers, they will mature” (Developer 4). This positivity is encouraging and aligns with the concept of policy learning, where institutions evolve and adapt over time [31,61].

Similarly, a weighted mean of 3.76 and a standard deviation of 0.99 suggest that developers acknowledge the planning authorities for increasingly encouraging development around metro stations. Although surprising given the extent to which TOD has been embedded in government policy, it is nevertheless encouraging for the future of TOD in Riyadh and aligns with broader literature on the role of planning authorities in facilitating TOD [1,11].

3.2. Local Structural Environment

This domain assesses the physical attributes relevant to TOD. The indicators in Table 2, such as ‘Land amalgamation’ and ‘Land availability’, were chosen to reflect critical aspects of urban fabric and land issues, including ownership patterns and land scarcity. The indicators are based on the land and urban form subdomain, focusing on the existing physical layout and land-related challenges in Riyadh. They were selected to provide information on physical constraints and opportunities in TOD development.

Table 2.

Weighted mean and standard deviation of the local structural environment.

Survey data indicate that land-related issues, including land amalgamation, fragmented land, and land availability, are the most pressing challenges for Riyadh’s TOD projects, with weighted means of 4.24, 4.19, and 4.14, respectively. The interviews also indicated concern about finding suitable land for TOD projects. The unwillingness of landowners to sell or partner with developers, as described by Developer 1, further exacerbates the issue:

“Now most of the land around metro stations is fragmented. I had an offer from one of the landowners to buy land next to one of the metro stations which was a very good 2000 sqm. And the land next to it was vacant. I said to the landowner, see your neighbors, these landowners, if I can buy from them. He said it is impossible, they don’t want it, they will not accept any offer, even a business partnership to develop as he already spoke to them. In terms of selling land in these locations, forget it. They should be hit with increased land fees [government taxes on vacant land], so they come to you running.”

This issue is not unique to Riyadh and has been discussed in the context of land assembly challenges in many other urban settings [6,10,14,43]. In this case, the developer’s statement offers insight into the complexities of acquiring land around metro stations in Riyadh, a critical factor in the successful implementation of TOD. The problem of fragmented land ownership presents a substantial obstacle to TOD projects, as it impedes the ability to acquire sufficiently large plots of land near metro stations for comprehensive mixed-use development. The developer’s experience underscores the reluctance of landowners to either sell or enter business partnerships, even when their land is strategically located near new metro stations. This reluctance not only stifles individual development projects but also has broader implications for the successful rollout of TOD initiatives in Riyadh. The developer’s suggestion of increasing land fees or taxes on vacant land near metro stations is highly relevant. Such a policy measure could serve as a financial disincentive for landowners to keep their land undeveloped. This could potentially alleviate the issue of fragmented land ownership, making larger plots available for TOD projects. It also aligns with the broader literature on land assembly challenges in urban settings, which often recommends fiscal measures to encourage more efficient land use.

The appropriate land size for TOD projects (“Land size challenge”) is another concern, as indicated by a weighted mean of 3.95. Developer 6 notes the difficulty in finding large enough parcels for mixed-use development:

“Land is the challenge. My current project is on track, but I’m looking for other lands where there is potential, but I can’t find. Of course, my scale is not a small scale, so it can be difficult to find something that suits our threshold.”

The land size issue in Riyadh is commonly experienced in many TOD contexts [12,31,62]. The developer’s response emphasizes the limited availability of appropriate land for implementing large-scale TOD projects in Riyadh. Land shortages not only restrict growth opportunities but also highlight the necessity for creative land-assembly strategies, such as land readjustment tools, to meet the requirements of developers with substantial investment capabilities and a strong desire to deliver TOD projects. Developers 5, 6, and 7 suggest a government-sponsored special-purpose company for large-scale urban redevelopment with special regulatory power to take the lead in land acquisition, infrastructure provision, and vacant land release, offering landowner partnerships or appraisal options as a possible solution to address this land challenge. Developers emphasize that the private development industry is unable to assemble land in TOD areas, as Developer 5 clarifies: “even if it is the largest development company, this has to be from the government and be guided”. Developer 6 agrees: “I believe that there should be a company, for example, created by the Public Investment Fund. This company can create partnerships with some developers who may have the interest and desire”.

Developers 1 and 3 note that TOD is being imposed on Riyadh’s existing urban fabric, posing unique challenges. Developer 1 proposes that when the metro system expands to new areas, planners should prioritize TOD in their planning decisions, suggesting that when land is subdivided to accommodate the metro in new, undeveloped areas, enough space for TOD should be provided to accommodate station developments. This resonates with the concept of “adaptive planning” and is consistent with the implementation challenges discussed in the TOD literature [9,11,61,63,64]. Furthermore, Developers 1, 4, and 5 identify the lack of existing TOD projects in Riyadh as a significant issue, creating uncertainty in assessing market demand and project feasibility. This is also corroborated by literature on the adversity and uncertainty faced by new TOD projects [6,10,13,14,64,65]. The developers’ observations point to a tension between retrofitting TOD into Riyadh’s existing urban landscape and the idea of initiating TOD in undeveloped areas. This tension raises questions about the adaptability of planning frameworks to accommodate both existing infrastructure and new developments and underscores the uncertainty that pervades TOD initiatives in Riyadh.

3.3. Local Collective Vision

This domain captures the shared vision and collaboration among stakeholders in TOD. Indicators such as ‘Interest in TOD’ and ‘TOD awareness’ were selected to gauge the level of engagement and understanding among developers regarding TOD projects. These indicators are based on the concepts of knowledge and alignment within this domain, focusing on developer awareness and vision for TOD, which are crucial for gauging the extent of their engagement and collaboration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Weighted mean and standard deviation of the local collective vision.

The high weighted mean for “Interest in TOD” (4.19) is also encouraging for the future of TOD projects in Riyadh and aligns more generally with the global recognition of TOD’s importance in fostering sustainable urban growth and reducing car dependency [23,33,38]. This interest is further substantiated by moderate to high weighted means for “TOD Awareness” (3.86) and “Participation in TOD” (3.81), further indicating a positive outlook among Riyadh’s developers adopting TOD. These findings resonate with the literature that emphasizes the crucial role of private developers in the successful implementation of TOD projects [8,9,47,48]. This can be considered a promising sign for the city, which is grappling with issues of urban sprawl and car dependency, as it indicates not just awareness but also willingness to act, which is crucial for the successful implementation of TOD in Riyadh. It suggests that the industry is not just passively interested but is actively considering TOD as a viable and necessary strategy for sustainable urban growth, and this is expected to grow further as experience grows. This aligns well with global trends and academic literature, reinforcing the idea that private developers are key stakeholders in the successful rollout of TOD initiatives.

However, concerns about the novelty and risk associated with TOD are also evident, with both “TOD too new” and “TOD too risky” receiving identical weighted means (3.24) and similar standard deviations (1.32, 1.23). Developers generally agree that the novelty and perceived risk of TODs pose difficulties for adoption. Developer 1 attributes the reluctance to engage in TOD to developers’ ignorance and focus on quick gains: “This is ignorance of the developer”. Developer 2 expresses skepticism about the success of TOD projects due to the newness and unknown adoption of public transport in Riyadh: “We do not have the experience here like many other countries”. In contrast, Developer 3 sees the newness as an opportunity and believes that with time, TOD will become more established. This mixed sentiment suggests that while there is interest in and awareness of TOD, the local industry is still grappling with the uncertainties and risks associated with its implementation. The concerns are not only about the concept itself but also about the local context, where public transport is not as established as in other cities with successful TOD and the extent with which residents will take to public transport is relatively unknown [1,2]. Therefore, while the data indicate that there is a positive interest in TOD, the perceived risks and novelty of the concept may act as barriers to its full-scale adoption. These barriers must be addressed to take advantage of the favorable attitude and interest in TOD among developers in Riyadh and beyond.

The low weighted mean for “Public-private collaboration” (2.67) is a noteworthy finding, given that effective collaboration among stakeholders is a crucial element for TOD success [9,18,23,31]. Also noteworthy is the weighted mean for “TOD Vision” (3.0), suggesting that while there is some alignment with broader TOD goals, articulation of a clear vision is lacking. Developers 1 and 4 indicate that vision alignment is a process that takes time and that the regulators have yet to identify developers who align with their vision for TOD: “their radar has not yet picked and chosen the right developers”. Developer 4 points out that both regulators and developers are still maturing in their approach to TOD and believes that it will take years for the impact of TOD projects to be felt and for a clear vision to emerge. This is undoubtedly the case and resonates with research that emphasizes the importance of cooperation and shared vision in the local context [8,10,31,49].

3.4. Local Economic Environment

This domain considers the economic factors that influence TOD. Indicators like ‘High initial investment’ and ‘Strong market for TOD’ were chosen to reflect the financial dynamics impacting developers’ participation in TOD. The selection of these indicators is rooted in the subdomain of market conditions, which focuses on the dynamics of the real estate market, financial conditions, and aspects of profitability pertinent to TOD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Weighted mean and standard deviation of the economic environment.

The high weighted means for “High initial investment” (4.05) and “Small developers’ ability” (to enter the TOD market) (4.0) highlight the financial challenges that private developers face. Developer 1 sees high costs as offset by enhanced profitability, while Developer 4 adopts a pre-selling model to mitigate preliminary costs. Developer 7 notes the necessity for alliances or significant capital, corroborating the literature on barriers for smaller developers [14,47,62]. However, small developers are the majority in Riyadh and should not be completely excluded from TOD projects. Perhaps they will find their place as the TOD landscape develops, and, as Developer 3 suggests:

“There will be a chance for a small developer on these smaller plots of land to develop a small profitable project because he can develop it better with cost control than me. His overheads and the quality of the product are different. So, he will have opportunities.”

Moderate weighted means for “Potential for return” (3.52), “Sufficient expected demand” (3.38), and “Regulations impact on profit” (3.24) suggest that while developers see potential profitability in TOD, they are concerned about the impact of the regulatory environment. Developer 1 discusses the trade-offs between planning incentives and additional costs, such as parking, echoing literature on the complex interplay between regulations and TOD profitability [8,9,18,66]. Developer 1 also emphasizes the need for regulatory clarity to reduce investment risk, suggesting that “it shouldn’t be bargaining from the beginning”. Developers again emphasize that the absence of regulatory clarity increases the risk associated with TOD projects, which impacts investment decisions, participation, and opportunity.

Planning incentives simply in the form of increased density do not necessarily lead to TOD projects taking off, as Developer 5 explains:

“The problem is that most developers will not exceed 40 floors in Riyadh while there are several stations that have unrestricted height. Why? The market today is not stimulating so that you build above 30 or 40 floors. This is not Central Park in New York, where you can see beautiful views or a river. Here you will only see sand when you go higher. It is not encouraging for the end user.”

Although TOD locations are generally considered prime real estate, this suggests that planners should consider market assessments in their incentive decisions. Increased density should not only be in the form of heights. A balance between cost to build and market revenue is an important factor in incentivizing TOD projects.

Developers expressed divergent perspectives on the impact of land prices and mixed-use developments on profitability. While Developer 3 believes that land costs are still reasonable, Developer 4 suggests that the profit potential of mixed-use projects could offset high land costs. These views are consistent with the research that emphasizes the importance of land use diversity in enhancing the economic viability of TOD projects [14,38,43,44].

Concerns about profitability also stem from the untested nature of TOD projects in Riyadh and the impact of market variables. Developer 1 points out that there is currently no successful TOD project in Riyadh to serve as a benchmark: “The problem is that these kinds of project have not been tried”. Developer 4 mentions internal and external market variables that affect demand and profitability. Developer 2 points out that while incentives may exist on paper, the practical realization of these incentives is fraught with complications and additional requirements, often turning them into restrictions:

“Meaning, once you start the project, good luck, you will face a lot of complexities to reach these incentives and it becomes evident to you that you reach a stage where you say I wish I didn’t start from the beginning.”

These comments echo the literature on the gap between policy intentions and practical implementation in TOD projects [6,8,11,20,67].

Data from developers highlights several key issues that contextualize the economic challenges of delivering TODs in Riyadh. TOD is untested in Riyadh, and the absence of a successful TOD project creates a vacuum of practical data, making it difficult for developers to assess risks and returns. This lack of a local benchmark amplifies the uncertainties around the financial viability of such projects. The mention of internal and external market variables indicates that demand and profitability are not solely determined by the TOD project itself but are influenced by broader economic conditions, adding another layer of complexity to an already uncertain landscape. Developer 2’s comment reveals a possible disconnect between policy intent and practical implementation. Although incentives may be designed to encourage TOD, market conditions and the bureaucratic complexities involved in accessing these incentives can act as unintended barriers, negating their intended purpose. This analysis appears to collectively underscore a high level of perceived risk, stemming from both the novelty of TOD in Riyadh and the complexities of the local regulatory and market environment. These observations suggest that for TOD to gain traction in Riyadh, there needs to be a concerted effort to address these challenges, possibly through pilot projects [31], streamlined regulations, and more transparent incentive structures.

Despite these uncertainties, developers are optimistic about the future of TOD in Riyadh and are anticipating a strong market for TOD and high expected demand, as indicated by weighted means of 3.76 and 3.29, respectively. This optimism could be seen as a reflection of the broader global trend recognizing the benefits of TOD in the promotion of sustainable urban growth. However, it is crucial to note that this optimism exists alongside the uncertainties and challenges previously discussed. This juxtaposition of optimism and uncertainty could imply that, while developers see the potential benefits of TOD, they are also acutely aware of the risks and complexities involved, particularly in a context like Riyadh, where TOD is very new.

3.5. Integrating Findings with the Research Objectives

This section explicitly connects the study findings to our stated research objectives and the broader body of relevant literature. First, by addressing the limited knowledge of private developers in TOD (Objective 1), our findings reveal significant challenges in the local regulatory environment, particularly in terms of institutional coordination and procedural clarity. Weighted mean scores and developers’ testimonies underscore the complexities of multiagency coordination, resonating with existing literature that highlights similar challenges in urban development [8,9]. This directly contributes to our objective of enriching TOD theory and practice, particularly in the context of developing countries where such regulatory intricacies are often more pronounced [6,10,43].

Second, in response to the call for more research on TOD in developing countries (Objective 2), our study provides empirical evidence from Riyadh, a rapidly urbanizing city. The issues of land amalgamation, fragmented ownership, and the challenges of integrating TOD into existing urban structures offer valuable insights into the specificities of TOD in such contexts. These findings align with the literature discussing land assembly challenges and the need for adaptive planning in TOD implementation [9,11,61,64], thus responding to the research gap identified by Abdi and Lamíquiz–Daudén [6].

Third, by exploring the role of private developers in Riyadh’s TOD (Objective 3), our research highlights their optimism for future TOD projects despite the challenges. This optimism, reflected in the high-weighted means for ‘Interest in TOD’ and ‘Participation in TOD’, is a crucial finding that underscores the potential role of private developers in shaping sustainable urban environments. This aligns with studies emphasizing the importance of private sector involvement in successful TOD projects [8,9,47,48].

Lastly, our study illuminates the barriers and facilitators for private developers in TOD projects (Objective 4). The financial challenges, as indicated by concerns over high initial investments and the difficulties faced by smaller developers, are critical barriers. However, the potential for profitability and market demand for TOD present opportunities. These findings contribute to the understanding of the economic factors influencing TOD, as discussed in the literature [14,38,43,44], and highlight the need for policy interventions that can mitigate these barriers and capitalize on the opportunities.

The research findings provide a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by private developers in TOD projects in Riyadh. By connecting these findings to our research objectives and situating them within the existing body of literature, we are contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of TOD in developing countries. This not only enriches the theoretical framework of TOD but also offers practical insights for policymakers and urban planners in similar urban contexts.

4. Conclusions

The research question investigating the potential challenges and/or opportunities that currently exist for the future delivery of TOD projects by Riyadh’s private developers has been addressed through a multifaceted analysis encompassing regulatory, structural, collective vision, and economic dimensions. The findings reveal a complex local environment that both encourages and challenges private developers in Riyadh’s TOD landscape in ways that are shared worldwide and substantiated by existing literature.

The study identifies institutional coordination as a critical challenge, compounded by issues of procedural clarity and timely approval. These findings suggest an urgent need for adaptive, context-specific planning and improved governance mechanisms to streamline TOD implementation. Land-related issues, particularly land amalgamation and fragmented ownership, are significant obstacles to implementation that are shared in developed and developing countries. Layering a comprehensive metro system on the existing urban fabric of the city of Riyadh and the subsequent opportunity for TOD adds another layer of complexity, necessitating innovative planning approaches. The data reveal a dichotomy of enthusiasm and apprehension among Riyadh’s private developers. While there is a general interest in TOD, the lack of effective public-private collaboration, institutional coordination, and a unified vision hampers progress, emphasizing the need for robust partnerships, regulatory reform, and vision alignment. The economic landscape for Riyadh’s TOD projects is complex, characterized by high initial investments and regulatory uncertainties. Despite these challenges, there is positivity among developers, underpinned by the potential for market demand and profitability. Although this study uncovers substantial challenges, it also identifies implications for improvement and potential opportunities. As private developers and planning authorities gain experience and policy learning evolves, there is cautious optimism for a bright future for TOD in Riyadh.

However, it may also be worth considering whether the existing urban fabric and development trajectory are more conducive to the principles of transit-adjacent development (TAD) than the more integrated and strategic approach of TOD. Such considerations require further investigation and may lead to a recalibration of urban planning strategies, one way or another, ensuring that future development efforts are aligned with the city’s unique characteristics and long-term sustainability goals.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study navigates the TOD landscape for private developers in Riyadh, it clearly has limitations. The small sample size of the developers surveyed may not fully represent the diversity of opinions and experiences and limits the ability to perform more robust statistical analyses. This constraint may affect the generalizability of the results, so the findings should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, this study does not consider the perspectives of other key stakeholders, such as planning authorities or community members. Despite these limitations, the study serves as an initial exploration and lays the groundwork for future research using larger sample sizes and multistakeholder approaches. Future research could also focus on the role of planning authorities in developing countries, further unpacking the attitudes and behaviors of private developers who deliver TOD, and expanding the applicability of the conceptual framework outlined in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and S.A.; methodology, F.A. and S.A.; validation, F.A. and S.A.; formal analysis, F.A. and S.A.; investigation, F.A. and S.A.; resources, F.A. and S.A.; data curation, F.A. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia, through the project no. IFKSUOR3–125–1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that it is non-interventional and non-experimental; the institution does not consider ethical approval a compulsory requirement for such studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project no. IFKSUOR3–125–1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Zohbi, G. Sustainable Transport Strategies: A Case Study of Riyad, Saudi Arabia. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 259, 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, O.; Potoglou, D. Introducing public transport and relevant strategies in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia: A stakeholders’ perspective. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2018, 6, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.R.; Dano, U.L. Sustainable urban planning strategies for mitigating climate change in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 22, 5129–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errigo, M.F.; Tesoriere, G. Urban travel behavior determinants in Saudi Arabia. TeMA-J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2018, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King Abdulaziz Project for Riyadh Public Transport. Royal Commission for Riyadh City. Available online: https://www.rcrc.gov.sa/en/projects/king-abdulaziz-project-for-riyadh-public-transport (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Abdi, M.H.; Lamíquiz-Daudén, P.J. Transit-oriented development in developing countries: A qualitative meta-synthesis of its policy, planning and implementation challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2022, 16, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatu, F.; Aston, L.; Patel, L.B.; Kamruzzaman, M. Transit oriented development: A bibliometric analysis of research. Adv. Transp. Policy Plan. 2022, 9, 231–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, A.; Fan, Y. Developers’ perspectives on transit-oriented development. Transp. Policy 2016, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, G.; Darchen, S.; Huston, S. Positive and Negative Factors for Transit Oriented Development: Case Studies from Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney. Urban Policy Res. 2014, 32, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.; Lewis, P.; Schiff, R. Transit-oriented Development in the Montreal Metropolitan Region: Developer’s Perceptions of Supply Barriers. Can. J. Urban Res. 2012, 21, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ibraeva, A.; Correia, G.H.D.A.; Silva, C.; Antunes, A.P. Transit-oriented development: A review of research achievements and challenges. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannawi, N.; Jones, P.; Titheridge, H. Development of transit oriented development in Dubai City and the Gulf States. In Transit Oriented Development and Sustainable Cities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Gloucester, UK, 2019; pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe, P. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream; Princeton Architectural Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, R.; Ferrell, C.; Murphy, S. Transit-Oriented Development and Joint Development in the United States: A Literature Review. TCRP Res. Results Dig. 2002, 52. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rrd_52.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Renne, J.L. Urban interventions: Formulating a strategy for walkable and transit-oriented development. In Handbook on Transport and Land Use Handbook on Transport and Land Use: A Holistic Approach in an Age of Rapid Technological Change; Edward Elgar Publishing: Gloucester, UK, 2023; pp. 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.; Inam, A. The Market for Transportation-Land Use Integration: Do Developers Want Smarter Growth than Regulations Allow? Transportation 2004, 31, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, G.; Ghate, A.; Bankim, K.; Mehta, P. Transit-Oriented Development Implementation Resources and Tools, 2nd ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34870 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Renne, J.L. From transit-adjacent to transit-oriented development. Local Environ. 2009, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer, A.; Janssen-Jansen, L.; Bertolini, L. Inter-actor Trust in the Planning Process: The Case of Transit-oriented Development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 21, 1153–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.D.; Ferbrache, F. Transit Oriented Development and Sustainable Cities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.M.; Ayad, H.M.; Saadallah, D.M. Planning Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): A Systematic Literature Review of Measuring the Transit-Oriented Development Levels. Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr. 2022, 6, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Balcázar, R.; Guerra, X. Transportation Oriented Development Method: Literature review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1141, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C. Transitioning to Transit-Oriented Development: The Case of Perth, Western Australia. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Transit-Oriented Development. Available online: https://ctod.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Baker, D.; Washington, S.; Turrell, G. Advance transit oriented development typology: Case study in Brisbane, Australia. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 34, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorus, P. Transit oriented development in Tokyo: The public sector shapes favourable conditions, the private sector makes it happen. In Transit Oriented Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.A.; Guthrie, A.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y. Transit-oriented development: Literature review and evaluation of TOD potential across 50 Chinese cities. J. Transp. Land Use 2017, 10, 743–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wey, W.M. Smart growth and transit-oriented development planning in site selection for a new metro transit station in Taipei, Taiwan. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannakis, A.; Yiannakou, A. Do Citizens Understand the Benefits of Transit-Oriented Development? Exploring and Modeling Community Perceptions of a Metro Line under Construction in Thessaloniki, Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.D.; Ferbrache, F.; Nikitas, A. Transport’s historical, contemporary and future role in shaping urban development: Re-evaluating transit oriented development. Cities 2020, 99, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Pojani, D.; Lenferink, S.; Bertolini, L.; Stead, D.; van der Krabben, E. Is transit-oriented development (TOD) an internationally transferable policy concept? Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrelja, R.; Olsson, L.; Pettersson-Löfstedt, F.; Rye, T. Challenges of delivering TOD in low-density contexts: The Swedish experience of barriers and enablers. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Chua, C.Y.; Skitmore, M. Towards Sustainable Mobility with Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): Understanding Greater Kuala Lumpur. Plan. Pract. Res. 2021, 36, 314–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berawi, M.A.; Saroji, G.; Iskandar, F.A.; Ibrahim, B.E.; Miraj, P.; Sari, M. Optimizing Land Use Allocation of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) to Generate Maximum Ridership. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongprasert, P.; Kubota, H. TOD residents’ attitudes toward walking to transit station: A case study of transit-oriented developments (TODs) in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Mod. Transp. 2018, 27, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Chou, C.C.; Wang, J.P.; Wang, T.K. Transit-Oriented Development: Exploring Citizen Perceptions in a Booming City, Can Tho City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklemariam, E.A.; Shen, Z. Determining transit nodes for potential transit-oriented development: Along the LRT corridor in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhereibi, A.H.; Onat, N.; Furlan, R.; Grosvald, M.; Awwaad, R.Y. Underlying Mechanisms of Transit-Oriented Development: A Conceptual System Dynamics Model in Qatar. Designs 2022, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutaleb, A.; Mcdougall, K.; Basson, M.; Hassan, R.; Mahmood, M.N. Understanding Contextual Attractiveness Factors of Transit Orientated Shopping Mall Developments (Tosmds) for Shopping Mall Passengers on the Dubai Metro Red Line. Plan. Pract. Res. 2020, 36, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatar, K.M. Transit-Oriented Development in Saudi Arabia: Riyadh as a Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Ewing, R.; Scheer, B.; Khan, S. Travel behavior in tods vs. non-tods: Using cluster analysis and propensity score matching. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2018, 2672, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, R.B.; Weiner, M.D.; DiPetrillo, S.; Kay, A.I. Attitudes towards transit-oriented development: Resident experiences and professional perspectives. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 60, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Ferguson, M.; Kanaroglou, P. Light Rail and Land Use Change: Rail Transit’s Role in Reshaping and Revitalizing Cities. J. Public Transp. 2014, 17, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lierop, D.; Maat, K.; El-Geneidy, A. Talking TOD: Learning about transit-oriented development in the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2016, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renne, J.L. Measuring the success of transit-oriented development. In Transit Oriented Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.; Bertolini, L. Defining critical success factors in TOD implementation using rough set analysis. J. Transp. Land Use 2017, 10, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, M.A. Developing TOD in America: The private sector view. In Transit Oriented Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- James, B. The property sector as an advocate for TOD: The case of south east Queensland. In Transit Oriented Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Cervero, R.; Iuchi, K. Transforming Cities with Transit; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almatar, K.M.; Almulhim, A.I. The Issue of Urban Transport Planning in Saudi Arabia: Concepts and Future Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, O.; Potoglou, D. Perspectives of travel strategies in light of the new metro and bus networks in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2017, 40, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quality of Life Program. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/vision-2030/vrp/quality-of-life-program/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Almardood, M.A.; Maghelal, P. Enhancing the use of transit in arid regions: Case of Abu Dhabi. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 14, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, D.; Babb, C.; Curtis, C. Doing Research in Urban and Regional Planning; Natural and Built Environment Series; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, I. Urban Planning Methods: Research and Policy Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.N. Online Research Methods in Urban and Planning Studies: Design and Outcomes; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications Limited: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 160940691773384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Grigolon, A.; Madureira, A.; Brussel, M. Measuring transit-oriented development (TOD) network complementarity based on TOD node typology. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, C.A.; Radaelli, C.M. Systematising Policy Learning: From Monolith to Dimensions. Political Stud. 2013, 61, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolleter, J.A.; Myers, Z.; Hooper, P. Overcoming the barriers to Transit-Oriented Development. Aust. Plan. 2021, 57, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannakis, A.; Vitopoulou, A.; Yiannakou, A. Transit-oriented development in the southern European city of Thessaloniki introducing urban railway: Typology and implementation issues. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 29, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, R.T.; Myerson, D.L.; Pawlukiewicz, M. Ten Principles for Successful Development Around Transit; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Allan, A.; Zou, X.; Scrafton, D. Scientometric Analysis and Mapping of Transit-Oriented Development Studies. Plan. Pract. Res. 2022, 37, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R. Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospects; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]