Abstract

Traffic collisions are the seventh leading cause of death in Ecuador, with reckless driving being one of the main causes. Although there are statistical data on traffic crashes, there has not yet been a comprehensive investigation of the causes. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to investigate unsafe driving behavior using a modified version of the Spanish Driving Behavior Questionnaire (SDBQ) adapted for Ecuador. The 34-item SDBQ we used has four main dimensions: lapses, errors, violations, and aggressive driving. To apply the SDBQ, a stratified random probability sample of 470 drivers with valid driver’s licenses aged 18–69 was used. Of the drivers, 68.8% were male, while 33.2% were female. We used a chi-square test and descriptive statistics to analyze the data for the SDBQ application items. Finally, four generalized linear Poisson models were used. The results show that taxi drivers have the highest scores on three of the four main dimensions of the SDBQ and male drivers are more likely than female drivers to cause traffic accidents. Drivers are also more likely to cause traffic accidents if they drive more hours per day. This research is the first of its kind to analyze driver behavior-based solutions in Ecuador to reduce traffic accidents. The error factor is the most critical outcome of dangerous behavior in the city of Cuenca. The SDBQ aims to foster a culture of safety and sustainability by promoting road safety measures through legislation and traffic regulations.

1. Introduction

Road traffic collisions (RTCs) are the ninth leading cause of death in the world [1]. Prior investigation of each region and country is necessary to reduce this preventable rate, as generalizing driving conditions and causes of road crashes is not possible. Factors contributing to RTCs vary between countries. Cyclists, pedestrians, and motorcyclists comprise approximately half of all road traffic fatalities in European countries [2]. In the 15–29 age group, road traffic crashes are the leading cause of death. However, in regions such as South America and especially Ecuador, the factors causing road accidents and the groups causing them differ. Therefore, the same statistics cannot be used as in Europe.

According to a report by the Pan American Health Organization, the Americas region is responsible for about 11% of global traffic crash fatalities, which equates to about 155,000 lives lost each year [3,4,5]. Drivers who have been involved in RTCs account for 34%. This is an alarming number, and unlike in regions such as Europe, where the rate of drivers engaged in RTCs is decreasing, in every Latin American region, especially Ecuador, it is increasing. The National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC) registered 73,341 deaths in Ecuador, with 3142 directly associated with RTCs. Therefore, among the leading causes of death in Ecuador, RTCs rank seventh [6,7].

Consequently, Ecuador and other countries in the region face significant challenges in reducing RTCs. The challenges start with a fundamental analysis of the causes, their components, and possible solutions. The lack of comprehensive research and diagnostics backed by empirical data and objective analysis makes it difficult to work under uncertainty and probably with statistical data that are not specific to the country. The lack of data makes it difficult to accurately determine the causes of road crashes, especially among drivers, who are primarily responsible. As a result, it is clear that further research and analysis are needed to understand these problems better and find more effective solutions.

The Driving Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) is a tool used to investigate the causes of RTCs. This type of questionnaire is used worldwide and allows for extensive research into the causes, factors, and possible solutions to RTCs. Various regions of the world have used this DBQ and adapted it to address the problems of RTCs in each region. Therefore, the SDBQ is a variation of the DBQ that applies to Spanish-speaking countries. As mentioned above, these adaptations include driver licensing types, driving-related cultural issues, and local characteristics. These studies emphasize that human behavior, especially driver behavior, is crucial for analyzing the complex sequence of events that can theoretically explain RTCs. However, it is necessary to adapt this modification to the Ecuadorian setting due to country-specific characteristics such as driver licensing, human aspects such as the authorization to drive for people with disabilities in Ecuador, and vehicle types that vary by region. By encouraging practices such as efficient driving and road safety enforcement, the SDBQ seeks to promote a culture of safety and sustainability. This not only improves road safety but also contributes to the city’s sustainability goals that focus on the Mobility Plan, creating a safer and greener urban environment.

To carry out research on RTCs in Ecuador, it is essential to achieve the objectives outlined in this article:

- Carry out a comprehensive analysis of the DBQ in order to gain an understanding of its influence on reducing road traffic accidents, distinguish the advantages and disadvantages that are mentioned in the existing literature, and ascertain whether or not it is suitable for addressing this matter.

- In order to create a Driver Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) specifically for Ecuador, it is crucial to scientifically modify the current DBQ structure to accurately represent the distinct driving habits and circumstances in Ecuador. This research can be an innovative scientific contribution to Ecuador and greatly improve traffic safety programs by offering data-driven insights to reduce road accidents.

- To ascertain the outcomes of the SDBQ for Ecuador, it is imperative to employ sophisticated statistical techniques for identifying the primary causes of road accidents within the nation. By employing this scientific methodology, which entails meticulous data analysis, the SDBQ is able to precisely mirror the unique driving conditions and behaviors in Ecuador. Through the implementation of scientific modifications to the questionnaire in accordance with the findings, the revised SDBQ will enhance its efficacy as a diagnostic and intervention instrument for identifying and mitigating the primary causes of road safety issues. Consequently, this will facilitate the development of road safety interventions that are more focused and successful.

This article is divided into several sections to achieve the intended objective: Section 2 reviews the existing literature on the DBQ and SDBQ. Section 3 clearly explains the methodology used in this study. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 examines the results for interpretation by comparing and contrasting them with the available literature. Finally, the Conclusion section summarizes the main findings and proposes future research.

2. Literature Review

Two important parts structure the literature: The first part focuses on analyzing the DBQ, which refers to the investigation of traffic psychology, ranging from errors and violations to aggressive driving behavior. Countries adapting to cultural differences have applied the DBQ. The second part of the literature is on the Spanish Driver Behavior Questionnaire (SDBQ), an adaptation of the original DBQ for the Spanish-speaking population, adjusting for traffic regulations, driving culture, and other factors specific to Spanish-speaking countries.

The DBQ is used to identify unsafe driving behaviors [8]. These behaviors include poor driving behavior, lack of concentration, aggressive attitudes, and infractions or violations of traffic regulations [9,10]. In line with the search for risk factors in road traffic crashes, the use of the DBQ provides data to identify the main characteristics that separate cautious drivers from high-risk drivers [11,12,13]. In this way, road safety prevention strategies can be developed, and the different elements involved in road crashes can be understood.

The DBQ is a tool for assessing human factors in driving, particularly those related to unsafe behavior [14]. This instrument has been applied worldwide, including countries such as Qatar [15], the United Arab Emirates [16], United States [17], China [18], Australia [19], Greece [20], Netherlands [21], Spain [22], France [23], New Zealand [24], Turkey [25], and the United Kingdom [26]. However, the items of the DBQ vary according to the country to which they are applied, but all address specific relevant cultural variables. Differences in age, gender, driving experience, vehicle type, educational programs, and mental health problems may be part of these. In addition, the sociodemographic characteristics of drivers and their crash experiences are recorded with the DBQ [27]. An abbreviated version of the DBQ, known as the SDBQ, has proven useful in predicting individual differences in traffic crashes. In its original version, the DBQ has a total of 126 items. However, the short version, adapted to the SDBQ, consists of 34 items.

The SDBQ is an instrument for assessing and analyzing driver behavior. It was developed by translating and adapting the items with specific adjustments to reflect the unique characteristics of the Spanish population [28]. Modifications and adaptations focused not only on linguistic translation but also on cultural contextualization [29]. This allowed for greater accuracy in the interpretation of responses and a more accurate assessment of driver behavior [30,31,32]

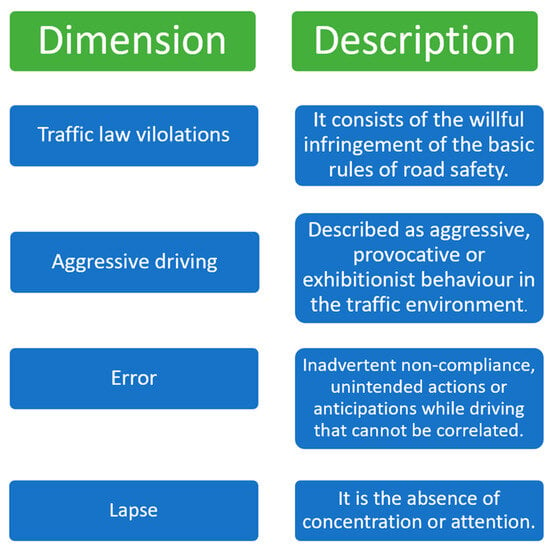

In recent years, the SDBQ has been applied in research in Spanish-speaking populations, for example, Colombia [33], Mexico [34], Spain [35], Brazil [36], and Argentina [37]. For this purpose, the four dimensions of assessment shown in Figure 1 have been used.

Figure 1.

Reduced-scale dimensions of SDBQ.

The versatility and applicability of the SDBQ in different Spanish-speaking environments demonstrate that the questionnaire is a valuable tool in the fields of traffic psychology and road safety. The collaboration and effort of experts who have come from different countries to adjust and apply the SDBQ testify to the continued commitment of the scientific community to improving the understanding of human behavior on the road, which is fundamental to the development of policies and practices that improve transportation safety and efficiency throughout the Spanish-speaking world [38].

Research in driver behavior has revealed multiple factors that contribute to RTC situations. According to this survey, male drivers are more likely to break traffic laws, which increases their risk of being involved in crashes; however, the validity of this claim may vary depending on the country [39].

In addition, studies have underlined the importance of human factors in traffic accidents. They emphasize that human aspects play a key role in these events while concluding that human error is involved in most road traffic accidents [40]. These results underline the importance of a detailed analysis of the various risk forms, including psychological factors and driving skills.

The SDBQ is a valuable tool that allows a more detailed approach to studying human error and RTCs since it allows a more thorough approach to everyday driving. Age-related studies have established that young, middle-aged drivers have a lower risk of being involved in road crashes [41]. This points to the need to assess the importance of age in evaluating and avoiding RTCs.

This literature review has demonstrated that the SDBQ is a proficient instrument for evaluating the dangerous conduct of drivers. Since the inception of research on RTCs, it has been utilized and modified in numerous Spanish-speaking nations. Countries such as Ecuador, characterized by a high rate of RTCs, exhibit a notably low prevalence of comprehensive research in this domain. The absence of such research highlights the significance of conducting an initial investigation within the country, utilizing the SDBQ tailored to the specific context of Ecuador. This endeavor aims to enhance comprehension of local issues and facilitate the advancement of road safety.

3. Method

The developed method consists of an explanation of the instrument, participants, and process. The objective is to measure the impact of unsafe driving behaviors, taking the daily driving hours, which are present in almost all items of the SDBQ, as an independent variable.

3.1. Instrument

The SDBQ was applied, consisting of four items: infractions, aggressive driving, lapses, and errors [42], composed as follows: 7 items of infractions or violations, 7 items of errors, 7 items of aggressive driving, and 7 items of lapses focused on answering (“how often had been related to the situations or behaviors mentioned in the SDBQ”).

The participants were evaluated on a 1–6-point scale (1 = never, 2 = almost never, 3 = rarely, 4 = sometimes, 5 = frequently, and 6 = always) [43]. In addition, drivers were asked to include information on their gender, age, marital status, educational level, license type, driving hours, seat belt use, alcohol consumption, and, finally, RTCs in the last three years [44,45].

3.2. Participants

This research was based on a stratified random sample [46] which was divided into different strata according to the age variant of the drivers [47].

The sample included 470 drivers between 18 and 69 years of age with a valid driver’s license. The drivers were randomly selected in Cuenca, including 314 male and 156 female drivers. Among this population, 55.5% had a professional license, which is for driving public transport vehicles, and 44.5% had a non-professional license, which is for driving private cars; in addition, 26.4% of the drivers reported driving less than three hours, 22.1% between 3 and 5 h, 21.7% between 5 and 8 h, and finally 29.8% more than eight hours a day. Finally, this study also considered 31 motorcycle drivers, 33 truck drivers, 26 city bus drivers, 6 van drivers, 176 car drivers, 86 van drivers, and 112 cab drivers.

3.3. Process

The SDBQ questionnaire was applied to and completed by the drivers. Before starting the survey, respondents were provided with brief and precise information about its purpose. All surveys considered were those carried out by a driver holding a valid license. The average time spent filling out each survey was approximately 14 min per driver. On the other hand, incomplete surveys were excluded.

Finally, the statistical analysis for this research was carried out using SPSS-25 software, resulting in descriptive statistics to evaluate the means and standard deviations of the SDBQ items. Generalized linear Poisson models were also developed to establish unsafe driving behaviors. Finally, the chi-square test was applied. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 illustrates the results of the first part of the survey, in particular, the distribution of the sociodemographic characteristics of the 470 drivers. The responses were divided into male and female responses.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic distribution of drivers by gender.

Among the participants in this research, 65.3% of the drivers claim to always use seat belts, 29.6% use them occasionally, and 5.1% do not use them at all. The latter two groups are the most likely to suffer severe RTC injuries, such as being hit by hard items inside the vehicle or being thrown out of the vehicle. Research conducted in [48] supports this claim, establishing that seat belts reduce the risk of death in a traffic accident by 45% to 50%. Another risk factor, such as phone use while driving, has become a significant safety issue worldwide, according to [49]. Finally, 36% of male and female drivers reported experiencing RTCs in the past three years, while 64% of participants claimed not to have experienced any RTCs. These figures highlight the need for preventive and educational measures focused on promoting seat belt use and raising awareness of the dangers of using a phone while driving, thus reducing accidents and injuries on the road.

Sixty percent of the drivers were between 26 and 49 years of age. It was observed that 29.3% of the male drivers in this sample were aged between 26 and 34, while 30.1% of the participants were women aged 35–49. Male drivers had driven an average of 2.71 h, compared to 2.22 h for female drivers. A sample of 169 drivers (108 men and 61 women) was analyzed, representing 35.95% of the total surveys in this study. Drivers reported whether they had been involved in a traffic crash within the last three years.

Significantly, the men had more excellent driving experience and more daily driving hours because of their vehicle type and license type (p < 0.001). According to the data presented between men and women, there were no significant differences in their marital status (p < 0.719), alcohol consumption (p < 0.655), use of seat belts (p < 0.471), and RTCs in the last three years (p < 0.317).

4.1. SDBQ Evaluation and Scales

Table 2 shows the scores obtained from the averages and standard deviations based on the responses to each SDBQ item for the four factors: lapses, errors, aggressive driving, and infractions. Overall, significantly high means were obtained for all SDBQ items. When considering cab drivers, the following risky driving behaviors were most frequently observed: “Nearly colliding with traffic that had the right of way due to failing to stop before a ‘Give way’ sign while turning left”, “Missing an exit on a highway or freeway and having to make a lengthy detour”, and “Missing ‘Give way’ signs and narrowly avoiding an accident with traffic that had the right of way”. Additional common risky driving behaviors included the following: “Expressing anger through aggressive gestures towards another driver” (aggressive driving), “Disregarding speed limits while traveling on a highway” (infraction), “Failure to use an exit on a highway or freeway”, and “Decrepitly stopping the vehicle at an intersection until oncoming traffic is compelled to yield and allow you to pass” (lapses). The mean scores for the six noted risky driving behaviors were all greater than 2.8, according to Table 2. Additionally, 27 risky driving behaviors received ratings between 2.00 and 2.80, and “Attempting to drive away from the traffic light in third gear” (lapse) received a rating between 1.00 and 1.99. When considering bus drivers, the following four risky driving behaviors were identified: “Aggressive driving” (speeding up and competing with other vehicles); “Crossing an intersection despite the traffic light having already turned red” (crossing an intersection in violation); “Error in overtaking due to underestimating the speed of an oncoming vehicle” (error); and “When approaching a specific location, momentarily reverting to the thought that you are approaching a more familiar location” (lapse). Each of these behaviors received a score ranging from 2.5 to 3.0. Simultaneously, truck drivers exhibited the same four most prevalent behaviors as bus drivers; however, their performance was assessed with marginally diminished scores, as illustrated in Table 2. The three most commonly observed risky driving behaviors among truck and bus operators were as follows: “Expressing anger towards another driver through aggressive gestures or other means” (aggressive driving); “Crossing an intersection while aware that the traffic light has already changed to red” (infraction); and “Nearly colliding with a cyclist approaching you from the inside while making a left turn” (lapsing). Their average scores ranged from 2.51 to 2.73 for all three.

Table 2.

The means and standard deviations of the SDBQ based on the type of driven vehicle.

4.2. Effects of Risky Driving Behaviors in Traffic Collisions

Risky driving behaviors are related to high violations of the law and driving attitudes at the time of driving [48,49,50].

Table 3 shows how the Poisson generalized linear regression models [51] were built to measure the effect of self-reported risky driving behaviors in RTCs, using driving hours and gender as independent variables. In addition, the sociodemographic characteristics of drivers are divided into four groups: (1) age, marital status, and education; (2) type of driver’s license and vehicle; (3) belt use; (4) alcohol consumption and RTCs in the last three years [52].

Table 3.

Poisson linear regression model results.

Table 3 shows RR (Relative Risk) and CI (confidence interval).

Therefore, four generalized linear regression models based on the Poisson distribution were used [53]. This study utilized four models, labeled A–D, to analyze the impact of driving frequency on risky driving behavior. Model A adjusted for age, marital status, and education, while model B adjusted for age, marital status, education, type of driver’s license, and type of vehicle. Model C further adjusted for the use of seat belts, and model D included additional factors such as alcohol consumption and involvement in road traffic collisions in the past three years.

According to the data presented in Table 3, it is evident that the effects varied. The results indicate that model A accounted for 5.39 (95% CI 0.616–0.960) men who drove between 3 and 5 h and were more prone to being involved in a road traffic collision (RTC). Analogously, an analysis was conducted for model B, considering the covariates of sex and driving hours. The findings indicated that 6.76 individuals (95% confidence interval: 0.806–1.09) exhibited aggressive driving behavior. In contrast, models C and D had a smaller effect, leading to a decreased likelihood of being involved in a road traffic collision [54,55]. Later, comparable analyses were utilized to evaluate the risk for women while driving. The data results indicate that the associations for models A, B, and C remained relatively stable. The results for each model were 2.58, 2.63, and 2.70, respectively, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals of (0.946–1.746), (0.953–1.66), and (0.955–1.68). In contrast, model D exhibited a lower score than the other models, with a value of 1.75 (95% CI: 0.910–1.62).

4.3. Chi-2 DBQ Items Statistical Test

Table 4 presents the chi-square results to estimate the association of two variables: the risky driving behaviors highly described in the DBQ items versus driving hours. The driving hours variable was considered an independent factor. It was discovered that drivers with more hours of daily driving were more likely to be involved in RTCs [56].

Table 4.

Chi-2 square DBQ test.

5. Discussion

The SDBQ is the most widely used instrument for measuring dangerous driving attitudes. This study assessed the age of drivers, marital status, level of education, license, vehicle type, and alcohol consumption among other sociodemographic characteristics [57].

In addition, the SDBQ results clearly showed that male drivers report a high number of incidents, errors, aggressive driving, and lapses and are more exposed than females to RTCs in consideration of the research conducted by Weller et al. [58], where it is stated that the presence of male drivers is associated with risky or unsafe driving behaviors and that they are more exposed than females to RTCs. Furthermore, research by Hung [59] revealed a distinction between errors, lapses, and violations, thus clearly showing the difference between intentional and unintentional hazardous driving behavior of male drivers compared to females. Likewise, research by Behnood et al. [60] showed that male and younger drivers in a group under 30 years of age were also more prone to RTCs. Likewise, according to the mean scores in all items of the four factors of the SDBQ, it could be detected, as the main finding, that cab drivers in the city of Cuenca are more prone to develop unsafe driving behaviors, having significantly high scores in infractions, lapses, and aggressive behaviors in similarity to the other types of drivers (bus, minibus, truck, car, and motorcycle drivers) and therefore being involved in a greater number of RTCs. This is also confirmed by research conducted in China by Zhou et al. [61], whose study determined that cab drivers present high scores in law violations, errors, and lapses, concluding that cab drivers are more likely to be involved in RTCs compared to another study conducted by Shi et al. [62], which detailed more studies on unsafe driving behaviors in Beijing cab drivers. The same study determined that Beijing cab drivers present more infractions, lapses, and aggressive behaviors in the main items of the DBQ, causing more RTCs than in other countries. However, very few studies have been conducted on the unsafe driving behaviors of cab drivers. On the other hand, it is necessary to highlight the research of McMurry et al. [63], whose study states that Bogota cab drivers represented higher scores in aggressive driving, lapses, and errors, being the group of drivers more prone and daily to be involved in RTCs in Bogotá, Colombia, unlike the other groups analyzed: private drivers and transmilenio (SITP) operators. It was also found that bus and truck drivers were also found to have higher SDBQ scores than the other driver groups studied: motorcycle drivers, bus drivers, minibus drivers, car drivers, truck drivers, and cab drivers, who are prone to unsafe driving and to be involved in RTCs, relative to the other driver groups. Considering all the results, it is recommended to design strategies to reduce hazardous driving among drivers, with special attention to cab and bus drivers, in order to achieve a reduction in hazardous driving behaviors such as “Disregarding speed at night or in the early morning”, “speeding on the highway and urbanizations”, and “crossing at an intersection despite having seen that the traffic light turned red”. Unlike cab drivers, car drivers provided the least information in the scores for each SDBQ item. These results bear some similarity to the study by Olandoski, et al. [64].

This work indicates that car drivers committed significantly fewer errors, infractions, lapses, and aggressive behavior compared to other groups of drivers, also considering the work of McMurry et al. [63], where it was established that private drivers indicated the lowest scores on all DBQ items, compared to bus, taxi, and shuttle bus drivers, and each of these behaviors scored less than 2.00 concerning the mean. The four factors contributing to insecure driving behavior for car drivers were identified as “Exiting a traffic light in third gear” (lapse), “Fail to check your rear-view mirror before pulling out, changing lanes, etc.” (error), and ‘‘‘Speed up’ and racing with other drivers” (aggressive driving).

As for Poisson’s generalized models, they were used in this research to measure the impact of insecure driving behavior by taking as a separate variable driving hours on all models A–D for men (A-0.31; B-0.382; C-0.434; D-0.437) and women (A-0.38; B-0.446; C-0.457; D-0.406), resulting in a Pseudo R2 value which is less than 0.5, as detailed above in all models A–D in Table 4. That is, regressions are not strong enough to explain the joint model [64]. In the present study, each variable was analyzed independently, i.e., the items of the SDBQ versus driving hours individually, thanks to the chi-square statistical test, as recommended by the authors Martinussen and de Winter [65,66].

The use of the chi-square method was recommended by the authors [67] in all SDBQ items in its four factors: violations, aggressive driving, lapses, and errors. It is estimated in this research that within aggressive driving, 86% of drivers drive unsafely. The least associated variable is “Race away from traffic lights to beat the driver next”. Regarding the factor violations, the results show that 75% of drivers drive insecurely, according to the research carried out in [68]. This finding highlights “unsafe drivers in violation” with high scores in the DBQ. The least associated variables were “Bypass speed limits to follow traffic flow” and “Drive even when you are aware of being able to find yourself above the legal alcohol limit”. On the other hand, regarding the error factor, it was detected that 100% of its items influence driving in an insecure and inaccurate way in all types of drivers compared to the study carried out in [69], detailing that the error factor within the DBQ proved to be the most relevant predictor of the TC frequency. Finally, in the SDBQ lapses dimension, 75% of its items were scored mostly high for influencing driving in an unsafe way. The less associated items were “Get into the wrong exit in a roundabout”, “Turn the cars light on instead of mopping the windshield, or vice versa”, “Exiting a traffic light at third gear”, and finally “Driving reversing, hitting against something you haven’t seen before”.

All of the above-mentioned overall results concluded that drivers with more hours of daily driving, regardless of their gender, are more likely to be involved in unsafe behavior; according to the research conducted by Ortega et al. [70], it was found that driving hours were related to further violations of traffic laws that contribute to most attitudes that cause RTCs [71].

6. Conclusions

The application of the SDBQ in Ecuador has proven to be a significant step in adapting the model to the specific reality of the country, providing valuable insights into RTCs. This adaptation has not only allowed for a better understanding of local behaviors and risk factors but has also opened new avenues for the prevention and improvement of road safety. Incorporating culturally relevant elements and the consideration of the unique traffic conditions in Ecuador make the SDBQ a tool for policy development in the country, contributing to the reduction in crashes and the devastating consequences they can bring.

In the last five years, many concerns have arisen in Ecuador regarding the deficiencies in safety issues of professional drivers and their link with risky behaviors when driving a vehicle, including speeding, disrespect for traffic laws, and fatigue while driving, among others. The results revealed significant differences for most of the SDBQ lapses of aggressiveness, errors, infractions, and driving factors, between male and female drivers, as well as between the different groups of drivers of cabs, buses, motorcycles, minibuses, passenger cars, vans, and trucks. It also showed that male drivers reported a high incidence of unsafe driving—violations, errors, and lapses—and are more likely than female drivers to be involved in traffic accidents. Through this study, policymakers will be able to make specific rules and regulations for focus groups to ensure road safety.

As for the generalized linear Poisson models, they were introduced in this research in order to measure the impact of unsafe driving behavior, taking as an independent variable the daily driving hour, the same that is present in almost all the items of the SDBQ, on risky or unsafe driving behaviors. The models made for both men and women were not strong enough to explain the model jointly, so we proceeded to use the chi-square statistical test in order to study in a concrete and precise way the unsafe driving behavior of the SDBQ items versus driving hours. Investigations revealed that drivers with valid driving licenses were committing offenses that they could have avoided by updating their knowledge of transport regulations and rules.

The SDBQ study in Ecuador represents a vital beginning for future research aimed at reducing traffic accidents in the country. This initial approach provides a solid framework for understanding and addressing risky and unsafe driving behaviors, laying the groundwork for further exploration of causes and solutions. Further research is needed to understand why, when, and how these risky or unsafe driving behaviors occur. The research provided may offer several avenues for further analysis with respect to traffic laws when driving vehicles on public roads. Together, these efforts represent a critical step towards a more complete understanding of road safety in Ecuador, as well as a step forward in creating effective laws and regulations to prevent accidents and save lives. Expanding this research to other regions could also yield valuable comparative insights. Assessing the influence of new policies using SDBQ findings will be essential for enhancing road safety strategies and road safety in other nations. The SDBQ aims to foster a culture of safety and sustainability by promoting practices such as efficient driving and strict enforcement of road safety measures. By enhancing road safety, this initiative not only aligns with the city’s sustainability objectives but also supports the Mobility Plan’s aim of establishing a safer and more environmentally friendly urban setting. This research allows Ecuadorian legislation to be modified in order to protect lives and avoid traffic accidents. This research facilitates the promotion of road safety measures through legislation and traffic regulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.E.E.-M. and M.O.; methodology, M.O. and K.E.S.E.; software, F.E.E.-M. and J.S.V.S.; validation, F.E.E.-M. and M.O.; formal analysis, F.E.E.-M.; investigation, F.E.E.-M. and J.S.V.S.; resources, F.E.E.-M. and M.O.; data curation, F.E.E.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.O.; visualization, M.O.; supervision, F.E.E.-M. and M.O.; project administration, F.E.E.-M. and J.S.V.S.; funding acquisition, F.E.E.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the “Grupo de Investigación en Ingeniería del Transporte (GIIT)” of the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana (UPS), Cuenca.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schlottmann, F.; Tyson, A.F.; Cairns, B.A.; Varela, C.; Charles, A.G. Road Traffic Collisions in Malawi: Trends and Patterns of Mortality on Scene. Malawi Med. J. 2017, 29, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, R.; Hafezi-Nejad, N.; Sadegh Sabagh, M.; Ansari Moghaddam, A.; Eslami, V.; Rakhshani, F.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Dominant Role of Drivers’ Attitude in Prevention of Road Traffic Crashes: A Study on Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Drivers in Iran. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 66, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Z.; Sze, N.N. Drivers’ Risk Perception and Risky Driving Behavior under Low Illumination Conditions: Modified Driver Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) and Driver Skill Inventory (DSI). J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 5568240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, J.J. Feature Selection for Driving Style and Skill Clustering Using Naturalistic Driving Data and Driving Behavior Questionnaire. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 185, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oña, J.; de Oña, R.; Eboli, L.; Forciniti, C.; Mazzulla, G. How to Identify the Key Factors That Affect Driver Perception of Accident Risk. A Comparison between Italian and Spanish Driver Behavior. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 73, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, F.; Esteban, C.; Montoro, L.; Serge, A. Conceptualization of Aggressive Driving Behaviors through a Perception of Aggressive Driving Scale (PAD). Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.G.; Sanmartín, J.; Keskinen, E. Driver Training Interests of a Spanish Sample of Young Drivers and Its Relationship with Their Self-Assessment Skills Concerning Risky Driving Behavior. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 52, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinussen, L.M.; Møller, M.; Prato, C.G.; Haustein, S. How Indicative Is a Self-Reported Driving Behaviour Profile of Police Registered Traffic Law Offences? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 99, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galovski, T.E.; Blanchard, E.B. Road Rage: A Domain for Psychological Intervention? Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004, 9, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.; Roman, G.D.; McKenna, F.P.; Barker, E.; Poulter, D. Measuring Errors and Violations on the Road: A Bifactor Modeling Approach to the Driver Behavior Questionnaire. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 74, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guého, L.; Granié, M.A.; Abric, J.C. French Validation of a New Version of the Driver Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) for Drivers of All Ages and Level of Experiences. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 63, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinussen, L.M.; Hakamies-Blomqvist, L.; Møller, M.; Özkan, T.; Lajunen, T. Age, Gender, Mileage and the DBQ: The Validity of the Driver Behavior Questionnaire in Different Driver Groups. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 52, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smorti, M.; Guarnieri, S. Exploring the Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Manchester Driver Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) in an Italian Sample. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 23, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, S.A.; Cendales, B.; Lijarcio, I.; Llamazares, F.J. Validation of the F-DBQ: A Short (and Accurate) Risky Driving Behavior Questionnaire for Long-Haul Professional Drivers. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 82, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlochan, F.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Gaben, B. Understanding Traffic Accidents among Young Drivers in Qatar. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlKetbi, L.M.B.; Grivna, M.; Al Dhaheri, S. Risky Driving Behaviour in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional, Survey-Based Study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabirinejad, S.; Tavakoli Kashani, A.; Nordfjærn, T. The Association between Lifestyle and Aberrant Driving Behavior among Iranian Car Drivers. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhao, J. Driver Behaviour and Traffic Accident Involvement among Professional Urban Bus Drivers in China. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 74, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinella, L.; Koppel, S.; Lopez, A.; Caffò, A.O.; Bosco, A. Associations between Personality and Driving Behavior Are Mediated by Mind-Wandering Tendency: A Cross-National Comparison of Australian and Italian Drivers. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 89, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nævestad, T.-O.; Laiou, A.; Phillips, R.O.; Bjørnskau, T.; Yannis, G. Safety Culture among Private and Professional Drivers in Norway and Greece: Examining the Influence of National Road Safety Culture. Safety 2019, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhfard, A.; Haghighi, F.; Fountas, G.; Das, S.; Khanpour, A. How Do Driving Behavior and Attitudes toward Road Safety Vary between Developed and Developing Countries? Evidence from Iran and the Netherlands. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoba, V.; Paneda, X.G.; Melendi, D.; Garcia, R.; Pozueco, L.; Paiva, S. COVID-19 and Its Effects on the Driving Style of Spanish Drivers. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 146680–146690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, M.; Delhomme, P.; Csillik, A. French Drivers’ Behavior: Do Psychological Resources and Vulnerabilities Matter? J. Saf. Res. 2022, 80, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullman, M.J.M.; Stephens, A.N.; Taylor, J.E. Dimensions of Aberrant Driving Behaviour and Their Relation to Crash Involvement for Drivers in New Zealand. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 66, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ş.; Arslan, B.; Öztürk, İ.; Özkan, Ö.; Özkan, T.; Lajunen, T. Driver Social Desirability Scale: A Turkish Adaptation and Examination in the Driving Context. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 84, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Rowe, R.; Poulter, D.R.; Powell, P.A.; Ypsilanti, A. Impulsive and Self-Regulatory Processes in Risky Driving Among Young People: A Dual Process Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 439067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, D.; Lotfi, B. Dimensions of Aberrant Driving Behaviours in Tunisia: Identifying the Relation between Driver Behaviour Questionnaire Results and Accident Data. Int. J. Inj. Control. Saf. Promot. 2016, 23, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, J.G.; García-Ros, R.; Keskinen, E. Implementation of the Driver Training Curriculum in Spain: An Analysis Based on the Goals for Driver Education (GDE) Framework. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 26, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, D.; Wang, Y.; Man, D. An Application of the Driver Behavior Questionnaire to Chinese Carless Young Drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2013, 14, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, V.C.; Pañeda, X.G.; Garcia, R.; Paiva, S.; Pozueco, L. Beside and Behind the Wheel: Factors That Influence Driving Stress and Driving Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Scott-Parker, B. Transcultural Validation and Reliability of the Spanish Version of the Behaviour of Young Novice Drivers Scale (BYNDS) in a Colombian Young Driver Population. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 49, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Fernández, D.; Bogdan-Ganea, S.R. Psychometric Properties of the Mexican Version of the Driver’s Angry Thoughts Questionnaire and Analysis of Invariance with the Romanian and Spanish Versions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 161, 106329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugenia Gras, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Cunill, M.; Planes, M.; Aymerich, M.; Font-Mayolas, S. Spanish Drivers and Their Aberrant Driving Behaviours. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Vidal-Branco, M.; Japutra, A. Understanding the Drivers of Organic Foods Purchasing of Millennials: Evidence from Brazil and Spain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trógolo, M.; Ledesma, R.D.; Medrano, L.A. Validity and Reliability of the Attitudes toward Traffic Safety Scale in Argentina. Span J Psychol 2019, 22, E51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poó, F.M.; Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Ledesma, R.D.; Díaz-Lázaro, C.M. Reliability and Validity of a Spanish-Language Version of the Multidimensional Driving Style Inventory. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 17, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucha, M.; Sramkova, L.; Risser, R. The Manchester Driver Behaviour Questionnaire: Self-Reports of Aberrant Behaviour among Czech Drivers. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2014, 6, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, V.; Aghabayk, K.; Parishad, N.; Shiwakoti, N. Evaluating Rainy Weather Effects on Driving Behaviour Dimensions of Driving Behaviour Questionnaire. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 6000715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, K. Assessing Dangerous Driving Behavior during Driving Inattention: Psychometric Adaptation and Validation of the Attention-Related Driving Errors Scale in China. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 80, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazdins, K.J.; Martinsone, K. Prediction for Driving Behaviour in Connection with Socio—Demographic Characteristics and Individual Value System. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 40, 03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.D.; Boyle, L.N. Driver Stress as Influenced by Driving Maneuvers and Roadway Conditions. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakaki, M.; Kontogiannis, T.; Tzamalouka, G.; Darviri, C.; Chliaoutakis, J. Exploring the Effects of Lifestyle, Sleep Factors and Driving Behaviors on Sleep-Related Road Risk: A Study of Greek Drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bener, A.; Crundall, D. Role of Gender and Driver Behaviour in Road Traffic Crashes. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2008, 13, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-mosa, Y.; Parkinson, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S. A Socioecological Examination of Observing Littering Behavior. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2017, 29, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Shariat-Mohaymany, A.; Nordfjaern, T. Accident Involvement among Iranian Lorry Drivers: Direct and Indirect Effects of Background Variables and Aberrant Driving Behaviour. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic. Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Yildirim, E.; Özkan, T.; Lajunen, T. Driver Sleepiness, Fatigue, Careless Behavior and Risk of Motor Vehicle Crash and Injury: Population Based Case and Control Study. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 4, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendak, S.; Al-Saleh, K. Seat Belt Utilisation and Awareness in UAE. Int. J. Inj. Control. Saf. Promot. 2013, 20, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, B.K.H. Road Safety Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours of Taxi Drivers in Hong Kong. HKIE Trans. 2018, 25, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, G.S.; Cho, E. Fatigue and Poor Sleep Are Associated with Driving Risk among Korean Occupational Drivers. J. Transp. Health 2019, 14, 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Moghaddam, A.; Sadeghi, A.; Jalili Qazizadeh, M.; Farhad, H.; Barakchi, M. Investigating the Relationship between Driver’s Ticket Frequency and Demographic, Behavioral, and Personal Factors: Which Drivers Commit More Offenses? J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2020, 12, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Feng, L.; Peng, H. Professional Drivers’ Views on Risky Driving Behaviors and Accident Liability: A Questionnaire Survey in Xining, China. Transp. Lett. 2014, 6, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Nguyen, T.; Su, D.N. The Effects of Unhealthy Lifestyle Behaviours on Risky Riding Behaviours—A Study on App-Based Motorcycle Taxi Riders in Vietnam. J. Transp. Health 2020, 16, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Du, F.; Qu, W.; Gong, Z.; Sun, X. Effects of Personality on Risky Driving Behavior and Accident Involvement for Chinese Drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2013, 14, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, S.S. Evaluation of Fear of Driving in Students of Driver License. Secur. Vialis 2011, 3, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemarié, L.; Bellavance, F.; Chebat, J.-C. Regulatory Focus, Time Perspective, Locus of Control and Sensation Seeking as Predictors of Risky Driving Behaviors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 127, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershon, P.; Ehsani, J.P.; Zhu, C.; Klauer, S.G.; Dingus, T.; Simmons-Morton, B. Vehicle Accessibility: Association with Novice Teen Driving Conditions. In Proceedings of the 9th International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training, and Vehicle Design: Driving Assessment 2017, Manchester, VT, USA, 26–29 June 2017; University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2017; pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ābele, L.; Haustein, S.; Møller, M.; Martinussen, L.M. Consistency between Subjectively and Objectively Measured Hazard Perception Skills among Young Male Drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 118, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, J.A.; Shackleford, C.; Dieckmann, N.; Slovic, P. Possession Attachment Predicts Cell Phone Use While Driving. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattak, Z.H.; Fontaine, M.D.; Boateng, R.A. Evaluating the Impact of Adaptive Signal Control Technology on Driver Stress and Behavior Using Real-World Experimental Data. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic. Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnood, A.; Mannering, F. The Effect of Passengers on Driver-Injury Severities in Single-Vehicle Crashes: A Random Parameters Heterogeneity-in-Means Approach. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2017, 14, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-L.; Lei, Y. A Slim Integrated with Empirical Study and Network Analysis for Human Error Assessment in the Railway Driving Process. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 204, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tao, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Atchley, P. A Survey of Taxi Drivers’ Aberrant Driving Behavior in Beijing. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2014, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurry, T.L.; Poplin, G.S.; Crandall, J. Functional Recovery Patterns in Seriously Injured Automotive Crash Victims. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2016, 17, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olandoski, G.; Bianchi, A.; Delhomme, P. Brazilian Adaptation of the Driving Anger Expression Inventory: Testing Its Psychometrics Properties and Links between Anger Behavior, Risky Behavior, Sensation Seeking, and Hostility in a Sample of Brazilian Undergraduate Students. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 70, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louveton, N.; Montagne, G.; Berthelon, C. Synchronising Self-Displacement with a Cross-Traffic Gap: How Does the Size of Traffic Vehicles Impact Continuous Speed Regulations? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic. Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.C.F.; Dreger, F.A.; Huang, W.; Miller, A.; Soccolich, S.; Ghanipoor Machiani, S.; Engström, J. The Relationship between the Driver Behavior Questionnaire, Sensation Seeking Scale, and Recorded Crashes: A Brief Comment on Martinussen et al. (2017) and New Data from SHRP2. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 118, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spano, G.; Caffò, A.O.; Lopez, A.; Mallia, L.; Gormley, M.; Innamorati, M.; Lucidi, F.; Bosco, A. Validating Driver Behavior and Attitude Measure for Older Italian Drivers and Investigating Their Link to Rare Collision Events. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 422200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Winter, J.C.F.; Dodou, D. The Driver Behaviour Questionnaire as a Predictor of Accidents: A Meta-Analysis. J. Saf. Res. 2010, 41, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.E.; Stephens, A.N.; Sullman, M.J.M. Psychometric Properties of the Driving Cognitions Questionnaire, Driving Situations Questionnaire, and Driving Behavior Survey. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 76, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Moslem, S. Decision Support System for Evaluating Park & Ride System Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Method. Urban Plan Transp. Res. 2023, 11, 2194362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Tóth, J.; Péter, T. Mapping the Catchment Area of Park and Ride Facilities within Urban Environments. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2020, 9, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).