Abstract

China’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) actions are driven by multiple factors, among which the government is an indispensable key player. This paper empirically examines the impact of government environmental information regulation (GEIR) on corporate ESG performance using a sample of Chinese A-share listed companies in heavily polluting industries from 2011 to 2021, with a GEIR in 2014 as an exogenous shock. GEIR is found to significantly improve corporate ESG performance, which is mainly reflected in the environmental and social dimensions. Moreover, improvements in the quality of corporate information disclosure and the efficiency of green innovation are found to be the main paths through which GEIR enhances corporate ESG performance. Further research shows that the enhancement effect of GEIR is more obvious in firms with low political relevance, high investor attention, and low marketization in the region in which they are located. This work enriches the research on GEIR and corporate ESG performance and provides some references for promoting the government to play a key role in China’s ESG initiatives.

1. Introduction

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices, as a weathervane for evaluating corporate sustainability and social value orientation, are highly compatible with the global concept of sustainable development. As the world’s second-largest economy, China has been advocating for “dual-carbon” development in recent years, and it is especially crucial for companies to practice ESG. However, on the whole, there remains a gap between the ESG development of Chinese companies and that of European and American companies [1,2]. ESG disclosure standards in Western countries have been more thoroughly established, with a mandatory disclosure requirement for all publicly listed companies. Conversely, China’s ESG disclosure regulations are relatively nascent, and the majority of companies currently adhere to a voluntary disclosure policy [2,3]. The 2022 Sustainability Survey by Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (KPMG) indicates that among the N100 companies in the United States, the ESG reporting disclosure rate reached 97% in 2022, with 69% of these reports being subject to independent assurance. In contrast, China’s ESG reporting rate stood at 89% but the assurance rate was significantly lower at just 30%. According to the global corporate ESG ratings released by MSCI, as of March 2024, only 13 Chinese companies have received an AAA rating, and as many as 80% of the companies have ratings below A. In contrast, more than 140 U.S. firms have AAA ratings and 66% of companies are rated between A and AAA. The primary reason for the ESG gap between Chinese and U.S. companies is that China’s institutional system and stage of development are different from those of Europe and the U.S. [4]. While institutional investors play an important role in promoting the ESG of European and American companies [5], they have limited influence on the ESG practices of Chinese companies. Chinese companies rely on government legislation and policy support to implement ESG practices [6]. Therefore, this paper examines the effectiveness of corporate ESG practice from the governmental perspective.

As the main driving force of corporate ESG actions, the government mainly promotes corporate ESG practices through the introduction of policies and regulations [7,8]. As a crucial part of the government’s environmental regulation policy, GEIR is an important guarantee to urge enterprises to disclose environmental information in an efficient and high-quality manner and to promote the protection of the ecological environment, the fulfillment of social responsibility, and the improvement in governance. According to the drivers, pressures, state, impact, and response (DPSIR) model of intervention, GEIR can not only exert regulatory pressure on enterprises but also stimulate their endogenous motivation [9]. From the pressure perspective, GEIR directly exerts pressure on enterprises. According to information asymmetry theory, the mandatory disclosure of information is conducive to reducing the information asymmetry between enterprises and the outside world [10]. Moreover, the increase in information transparency brings about increased regulatory pressure from multiple parties, including the government, shareholders, and society [11], forcing enterprises to improve their ESG performance. From a motivational perspective, GEIR can stimulate the motivation of firms to improve ESG performance on their own. According to legitimacy theory [12,13], firms are motivated to improve their ESG performance to gain recognition and support from the government and stakeholders for the purpose of legal compliance and to build and maintain a good reputation [14]. Therefore, government regulation of environmental information puts pressure on firms and motivates them to take action to improve ESG performance in response to the policy.

The GEIR promulgated in China in 2014, as a typical representative of GEIR, provides a natural scenario to investigate corporate ESG from the governmental perspective. Firstly, GEIR is exogenous to the firms, which means that corporate ESG performance does not sway the enforcement of the policy, thereby effectively side-stepping the endogeneity issue of reverse causality. Secondly, GEIR requires enterprises to disclose pollutant monitoring information, supplemented by the supervisory monitoring of pollution sources by the environmental protection department and the supervision and reporting mechanism of the public. The mandatory disclosure requirements and strict supervision and punishment mechanism promote enterprises to formally improve the quality of environmental information disclosure and enhance the ability of sustainable development in action, thus gradually realizing the enhancement of the ESG level. In the current literature, research on the economic outcomes of corporate ESG performance has concentrated on aspects such as corporate valuation, risk management, and financial performance [4,15]. The factors influencing corporate ESG performance considered in previous research can be divided into two main categories, namely internal corporate factors and external environmental factors. The former includes corporate size, executive characteristics, board characteristics, corporate merger and acquisition activities, and corporate financial performance [16,17,18,19,20,21,22] and the latter includes the natural, market, and institutional environments [23,24,25,26,27]. Although the drivers of corporate ESG performance from the governmental perspective have been studied, such as financial control and environmental protection inspection [28,29,30], at this stage, the assessment of corporate ESG performance by external agencies mainly involves the publicly disclosed information of companies. While the importance of information disclosure to corporate ESG ratings is self-evident, few studies have focused on the impact of GEIR on corporate ESG performance. Therefore, the research question addressed in of this paper is whether and how GEIR affects corporate ESG performance.

Based on this, the GEIR in 2014 is taken as a policy shock, the key emission units, which are the policy monitoring target, are taken as the treatment group, and other sample enterprises are taken as the control group. Based on this, the effects of GEIR on corporate ESG performance and their mechanisms are empirically examined using the difference-in-differences (DID) method. It is found that GEIR significantly improves corporate ESG performance, mainly in the environmental and social aspects, and the quality of firms’ information disclosure and the efficiency of green innovation are found to play important roles in the transmission. Further analysis reveals the heterogeneity in the effect of GEIR on corporate ESG performance. A more pronounced effect on ESG performance is more likely for firms with a low degree of political relevance and a high degree of investor attention as well as those located in regions with a low degree of marketization.

This study makes several contributions to the extant research.

First, the relationship between GEIR and corporate ESG performance was examined from the governmental perspective, thereby enriching and expanding the governmental perspective in the study of the influencing factors of corporate ESG performance. Although scholars have previously explored the relationships between governmental factors, such as financial control and environmental protection inspection, and corporate ESG performance [28,29,30,31], there has been a lack of sufficient attention to the governmental perspective of information regulation. Therefore, the present work examines the impact of GEIR on corporate ESG performance, thereby providing empirical evidence for understanding the importance of assessing GEIR in corporate ESG actions and promoting the key effectiveness of the government in corporate ESG actions.

Second, from the perspective of information asymmetry and legitimacy, a theoretical linkage mechanism between macro GEIR and corporate micro subjects is constructed, and the transmission mechanism of GEIR on corporate ESG performance is refined. Most ESG studies are based on stakeholder theory, which considers that stakeholders are an important driving force for corporate ESG actions. In these studies, the mechanisms affecting corporate ESG are analyzed from the perspectives of stakeholder concerns and risk perception [18,24,32]. However, the present work, which is based on information asymmetry theory and legitimacy theory, reveals the roles of information disclosure quality and green innovation efficiency as a bridge between GEIR and corporate ESG. This enriches the research on the influencing factors of corporate ESG performance and also provides new ideas for the effective interface between macro policies and micro subjects.

Third, a heterogeneity test clarifies the boundary conditions under which GEIR affects corporate ESG performance, thereby providing suggestions and directions for promoting a more effective role of the government in corporate ESG governance. Most studies have explored the differentiation effect of policies from the perspective of firm characteristics, such as firm size, firm distribution region, and firm management characteristics [33,34,35]. In contrast, in the present research, the asymmetric effect of GEIR on corporate ESG performance is tested from three perspectives: the degree of political relevance, investor attention, and the degree of marketization. Findings from the heterogeneity tests could serve as a reference for developing countries and emerging economies, much like China, in fostering the growth of corporate ESG practices. In particular, a new reference program for the environmental protection sector when formulating policies is proposed to promote corporate ESG actions; this program can include the implementation of policies tailored to local conditions and placing focus on the review of political connections, as well as joining hands with investors to strengthen the supervision of enterprises to achieve better policy effects.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background of GEIR and the development of the research hypothesis and Section 3 presents the research design. Section 4 provides an empirical analysis to verify the hypothesis. Section 5 presents further research to expand the study, and, finally, Section 6 systematically summarizes the research findings and explores their policy implications.

2. Institutional Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Institutional Background

GEIR is an important institutional arrangement for the government to establish and improve the monitoring and information disclosure system for pollution sources and to urge enterprises to consciously fulfill their legal obligations and social responsibilities. Prior to the promulgation of the Measures for Self-Monitoring and Information Disclosure by State Key Monitoring Enterprises and the Measures for Supervisory Monitoring and Information Disclosure by State Key Monitoring Enterprises in 2014, China’s GEIR had gone through three important phases, namely the first introduction of the regulation (2003), the enrichment of the main body of the policy implementation (2007), and the reinforcement of supervision and management (2008). Unlike the carbon emissions trading market and green credit guidelines, which incentivize enterprises to reduce pollution emissions and strengthen environmental protection through market mechanisms and resource allocation, the GEIR, promulgated in 2014, requires enterprises to monitor and disclose environmental information on their own, supplemented by supervisory monitoring by environmental protection departments. It also promotes the improvement in environmental information and the practice of ESG by influencing the transparency of enterprises’ environmental information and their ability to develop sustainably.

GEIR exerts direct pressure on enterprises to disclose environmental information on a mandatory basis, which helps to improve the transparency of their environmental information. Compared with the voluntary disclosure of environmental information by enterprises, mandatory disclosure can force enterprises to improve the authenticity and reliability of the information and provide an opportunity to strengthen the external regulation of enterprise ESG development. In addition, the deeper purpose of GEIR requiring enterprises to disclose environmental information is to observe the environmental performance of enterprises. The environmental information disclosed by an enterprise can not only reflect the environmental situation of the enterprise but can also deeply reflect its social responsibility and governance capacity. Moreover, it can promote enterprises to continuously realize the sustainable development of the environment and social and corporate governance and to implement the concept of ESG action in the disclosure of environmental information in the process.

The introduction of GEIR in China in 2014 further enriches the content of GEIR and strengthens its implementation, which creates a natural context for this paper to study whether and how GEIR affects corporate ESG performance.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

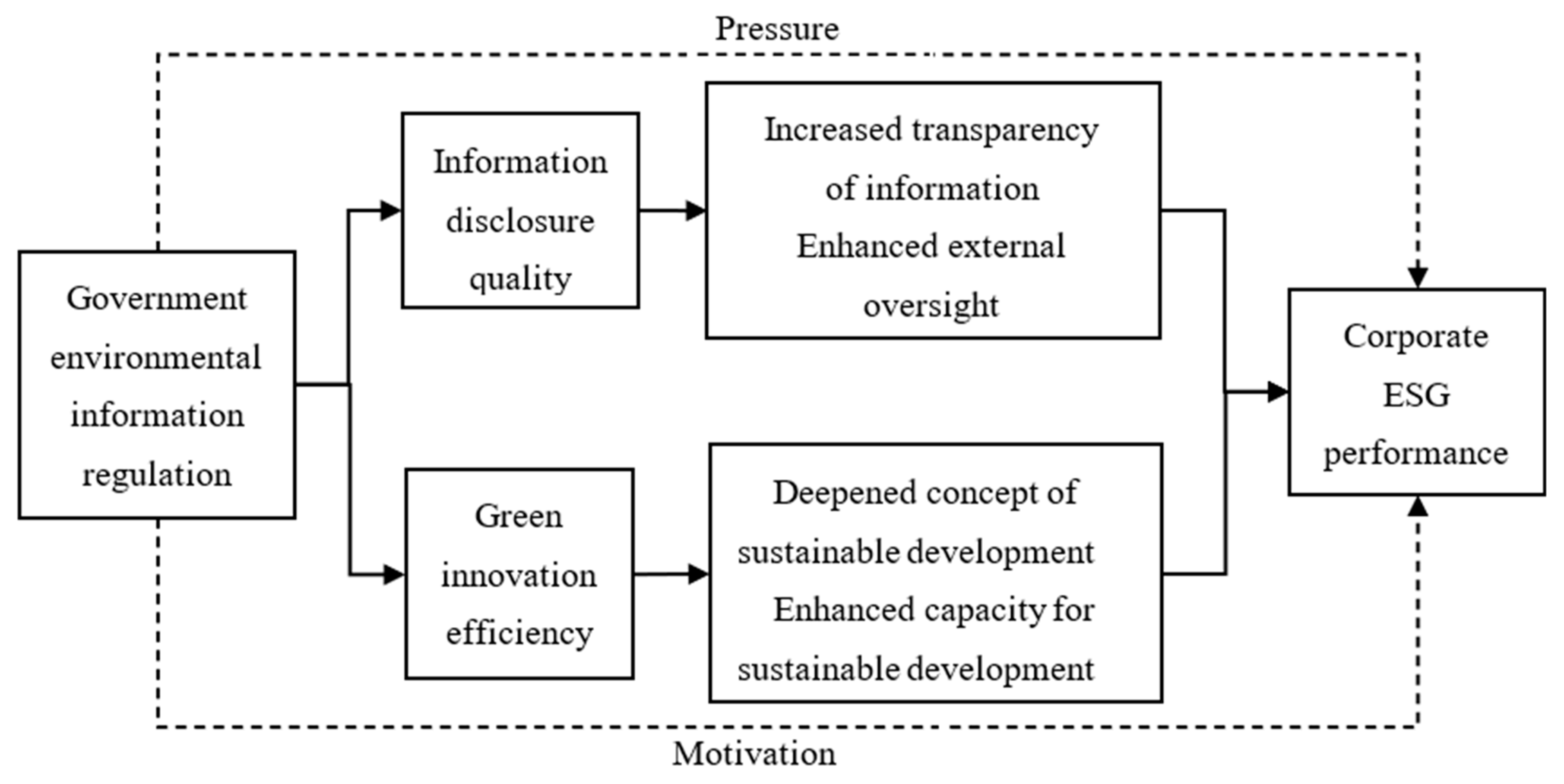

This paper focuses on the impact of GEIR on corporate ESG performance and its mechanism through the lens of information asymmetry theory and legitimacy theory. Based on information asymmetry theory, GEIR requires enterprises to compulsorily disclose environmental information, which effectively reduces the degree of information asymmetry between enterprises and the outside world. Increased information transparency strengthens the attention and supervision of outsiders, and the pressure of outside supervision forces enterprises to improve their ESG performance. In addition, enterprises must invest a substantial amount of resources to monitor and disclose environmental information and may even suffer administrative penalties because of negative environmental information. However, if enterprises do not monitor and disclose appropriate environmental information in accordance with the requirements of the regulations, they will face huge legal penalties and moral public opinion pressure, which will lead to higher costs. Therefore, based on legitimacy theory, the psychological pursuit of legal compliance and the attempt to establish and maintain a good reputation will motivate firms to improve their sustainability capabilities, which in turn will improve their ESG performance. Based on this, the theoretical analysis and research hypothesis are developed according to the logical framework shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The logical mechanism diagram.

First of all, GEIR affects corporate ESG performance by enhancing the corporate disclosure quality. Institutional pressure is an important external factor influencing corporate disclosure behavior [36,37]. Based on information asymmetry theory, disclosing a large amount of information can reduce information asymmetry [38,39]. GEIR requires enterprises to disclose information about their pollutant monitoring programs, results, and annual reports, which reduces the information asymmetry between the government and enterprises. To cope with the institutional pressure from the government, enterprises will inevitably choose to improve the truthfulness and accuracy of information to disclose the best information. However, when regulation is insufficient, information disclosure often becomes a “self-interested tool” used by enterprises to whitewash their own image [40]. GEIR requires enterprises to disclose environmental information but also requires local environmental protection departments to carry out the supervisory monitoring of pollution sources in the region and disclose the monitoring information. It also encourages the public to report on the illegal behaviors of enterprises. The strict supervision and management mechanism reduces the possibility of the falsification of environmental information and the selective disclosure of positive information by enterprises. Moreover, enterprises are motivated to improve the quality of information disclosure for the sake of legal compliance, to convey signals of sustainable development to the outside world, and to maintain their reputations and images to obtain the recognition and support of all stakeholders. Therefore, government regulation of environmental information improves the authenticity and reliability of corporate environmental information and effectively enhances the quality of information disclosure.

The higher the quality of an enterprise’s information disclosure, the greater the transparency of the enterprise’s information. Increased information transparency increases the amount of enterprise information available to the government, shareholders, and the public and the attention and supervision of the outside world toward the enterprise also increase. Based on legitimacy theory, enterprise behavior must meet the requirements of legal norms. While enterprises may have poor environmental performance, under the constraints of numerous environmental regulations and multiple monitors, they will not passively disclose negative environmental information and will inevitably actively carry out environmental governance to improve their environmental performance. Simultaneously, the public is able, through a large amount of corporate environmental information, to judge whether corporate behaviors will bring negative impacts to society and whether corporations promote sustainable social progress through their own development; this further urges corporations to actively fulfill their social responsibilities [41,42]. In addition, information transparency is the foundation and key to good governance [43], and the internal governance structure is the institutional basis for safeguarding the rights and interests of shareholders. Improved information transparency makes it easier for shareholders to grasp the internal governance of the enterprise. Thus, shareholders will give full play to their supervisory function out of their own interests and push the enterprise to improve the level of corporate governance. Therefore, high-quality information disclosure improves the information transparency of enterprises and promotes stakeholders to strengthen the attention and supervision of enterprises, thus prompting enterprises to actively improve their ESG performance.

Second, GEIR affects corporate ESG performance by improving its green innovation efficiency. When faced with the regulatory pressure of environmental regulation, rational firms will carry out green innovation to seek harmonious development between the economy and the environment [44,45,46]. Based on legitimacy theory, firms must disclose appropriate environmental information to meet policy requirements for compliance purposes. GEIR requires enterprises to disclose the types and concentrations of pollutants in detail, such as the “three wastes”, their compliance with standards, the number of times the standards are exceeded, and the manner and destination of emissions. The Environmental Protection Department will deal with enterprises that do not rectify the environment in accordance with the law. Therefore, enterprises cannot solve environmental problems only through “end-of-pipe management”, which is not sufficient to address the long-term supervision of the government and environmental protection departments. Instead, substantive measures, such as green innovation [47,48], must be taken to eradicate the environmental problems arising from the production and operation process and ensure that the government’s expectations for good environmental information are met. In addition, GEIR requires environmental protection departments to promptly publish supervisory monitoring information on the pollution sources of national key monitoring enterprises characterized by serious pollution. The publication of negative environmental information will inevitably have negative impacts on the reputation, image, and long-term development of enterprises, which are motivated to carry out green innovation activities to solve environmental problems. Therefore, GEIR can promote enterprises to carry out green innovation activities and improve the efficiency of enterprise green innovation.

Green innovation embeds the concept of sustainable development into the whole process of production and operation and the future development strategy of enterprises and promotes the gradual improvement in ESG performance in the process of achieving sustainable development. Enterprises can optimize production processes and production flows through green innovation, thus improving energy usage while greatly reducing pollutant emissions [49,50,51]. Moreover, green technological innovations, such as cleaner production technologies and energy-saving and carbon reduction technologies, can prevent and control the generation of pollutants in the production chain from the source [1]; this can radically reduce the occurrence of environmental problems and thus improve the environmental performance of enterprises. In addition, green innovation encourages enterprises to integrate green concepts into their product design and daily office operations, thus providing safe and environmentally friendly green products for the public [52] and safe and clean workplaces for employees, which meets the social demand for green and protects the interests of employees. This meets the social demand for green practices, protects the interests of employees, and promotes enterprises to effectively undertake their social responsibilities. Green innovation can also promote enterprises to achieve their own long-term development, meet the concerns and expectations of shareholders for the sustainable development of the enterprise, and effectively protect the rights and interests of shareholders. Moreover, green innovation can effectively reduce the environmental and social risks and crises of enterprises and effectively improve the corporate governance structure. Therefore, green innovation can promote enterprises to realize the overall sustainable development of environmental, social, and governance practices, thus enhancing ESG performance.

Based on the above theoretical analyses, the following core research hypothesis is proposed:

H1:

Ceteris paribus; GEIR enhances corporate ESG performance.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data

A-share listed companies in highly polluting industries from 2011 to 2021 were selected as the research sample, and 2015 was considered the time point of policy implementation. The reason for taking 2015 as the time point of policy implementation is that local governments only announced the list of key emission units one after another in 2015, and the GEIR work was only carried out beginning in 2015. In addition, the Administrative Measures for the Legal Disclosure of Corporate Environmental Information issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in late 2021 further strengthened the requirements for corporate environmental information disclosure. To exclude the interference of this policy, the sample period ended in 2021. Data on corporate ESG performance were sourced from the Sino-Securities Index Information Service (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and other data on listed companies were sourced from the CSMAR and CCER databases.

The identification of highly polluting industries was mainly based on the Guidelines for Disclosure of Environmental Information by Listed Companies (Environmental Affairs Office Letter [2010] No. 78). The specific screening process was as follows. First, the codes of highly polluting industries were determined, according to which, listed companies were selected; this yielded a total of 1380 listed companies. Second, the samples were further screened as follows: ➀ ST enterprises and *ST enterprises during the observation period; ➁ samples with abnormal or missing data were eliminated; and ➂ samples from the financial industry were eliminated. After screening, 1243 sample enterprises were retained. Finally, to avoid the effect of outliers, 1% winsorization was conducted on the main variables.

3.2. Model

To test the core hypothesis, the following DID model (1) was constructed:

where the variable subscripts i and t denote the firms and time, respectively, the explanatory variable ESGit is the ESG performance of firm i in year t, and the core explanatory variables are Treat × Postit, where Treat is a dummy variable representing whether the firm is a key emission unit, and Post is a dummy variable representing the periods before and after GEIR. Moreover, Xit is a series of control variables. In addition, a series of fixed effects were controlled for in the model; λt and µi, respectively, denote year fixed effects and firm fixed effects, and εit denotes the random perturbation term. This research focuses on the significance of the interaction term coefficient α1 in model (1). According to the hypothesis, if α1 is significantly positive, then GEIR can enhance corporate ESG performance. Furthermore, this paper conducts four robustness tests, including the placebo test, propensity score matching, alternative ESG metrics, and the incorporation of city fixed effects, to bolster the robustness of conclusions.

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

The ESG index from the Sino-Securities Index Information Service (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. was used as the main indicator of corporate ESG performance and is now widely recognized and applied by academics [6,53]. In the ESG rating methodology, the rating agency has incorporated financial metrics, including corporate growth potential, asset-liability ratios, and patterns of ownership, as control variables. This indicates that the significance of finance and the impact of corporate ownership on ESG ratings have been thoroughly considered. The ESG rating data from the Bloomberg database were used for robustness testing. In addition, the ESG index from the Sino-Securities Index Information Service (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., is disclosed quarterly, and the evaluation disclosure in January of year t implies the relevant information of enterprises in October–December of year t − 1. Thus, the average of the scores for the four months of disclosure (April, July, October in year t, and January in year t + 1) was selected as a measure of the average score of the index in year t; the higher the score, the higher the level of ESG performance.

3.3.2. Independent Variable

The core explanatory variable takes the form of a double difference term Treat × Postit. If the annual report of an enterprise discloses the content of a key emission unit, the enterprise is judged to be a key emission unit and is defined as the treatment group, for which the value of 1 is taken for Treat; otherwise, it is defined as the control group, for which the value is 0. If the period of policy implementation is 2015 or later, Post takes the value of 1; otherwise, it is regarded as a period of non-implementation, and the value is 0. In other words, when enterprise i is a priority emission unit and in the year 2015 or later, this interaction term takes the value of 1; otherwise, it takes the value of 0.

3.3.3. Control Variable

Referring to existing studies [6,24,54], we incorporate a suite of firm-level control variables that are known to influence corporate ESG performance. Research has consistently demonstrated that firm size (Size) and firm age (Age) are pivotal determinants of the accessibility of corporate ESG data and the resources necessary for ESG reporting [16]. Furthermore, the substantial literature base corroborates the link between overall firm performance and its ESG performance [4,55]. Accordingly, we control for firm performance (ROA), the asset-liability ratio (Lev), operating cash flow (Cash), and firm growth (Growth), which are four critical financial indicators. Additionally, we acknowledge the pivotal role of the board of directors in shaping a firm’s ESG performance. As the internal governance and oversight force, the board significantly influences the execution of ESG initiatives, both in terms of its composition and decision-making processes [4,56]. In particular, we control for equity checks and balances (Balance), shareholding concentration (Top), board size (Board), and the proportion of independent directors (Indr). Similarly, investors, acting as an external monitoring force, can exert influence on a firm’s ESG performance through their equity stakes and managerial engagement [4]. We therefore control for the institutional shareholding ratio (Organ) to account for this dynamic. The names, symbols, and measures of the variables are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The descriptions of variables.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed after conducting a 1% winsorization treatment for the main variables. According to the results reported in Table 2, the mean value of corporate ESG performance is 3.993, indicating that most of the heavily polluting firms still do not reach an ESG rating of grade B. Moreover, the minimum value is only 1, which suggests that some of the heavily polluting firms still have substantial room for improvement in their ESG performance. The distributions of the remaining variables are consistent with the findings of the mainstream literature.

Table 2.

The descriptive statistics.

4.2. Baseline Results

The prerequisite for the use of the DID method is to pass a parallel trend test that proves that the treatment and control groups had the same trend prior to the implementation of the policy. The event study method was used for parallel trend testing, and the results are reported in Table 3. Before the implementation of the policy (before 2015), the coefficients were negative and insignificant, indicating that there was no significant difference between the ESG performance of firms in the treatment and control groups before governmental environmental information regulation; this satisfies the parallel trend hypothesis. After the GEIR (in 2015 and later), the coefficients were positive, and they were significant in the second year after the implementation of the policy. This indicates that after the implementation of the policy, the ESG performance of the key emission units increased significantly, thus proving the validity of the parallel trend hypothesis.

Table 3.

The parallel trend test results.

Table 4 reports the DID regressions results, in which Column (1) presents the estimation results of model (1). The results show that after controlling for firm fixed and year fixed effects, the coefficient of the interaction term Treat × Post was found to be 0.094 and significant at the 5% level. This indicates that GEIR can enhance the ESG performance of key emission units and that the ESG scores improve by 9.4% after the implementation of the policy. This is economically significant, thus verifying the core hypothesis.

Table 4.

The baseline results.

ESG performance is a comprehensive indicator calculated by weighting the ratings of three different dimensions, namely the environmental, social, and governance dimensions, but each has its own focus. Therefore, the impact of GEIR on each dimension was, respectively, explored to investigate the differences between the different dimensions. Columns (2) and (3) of Table 4 show that the regression coefficients of environmental (E) and social (S) dimensions are positive and significant, indicating that GEIR has a significant positive impact on firms’ environmental and social performance. However, the regression coefficients of corporate governance (G) reported in Column (4) are not significant, suggesting that GEIR cannot improve the corporate governance level of firms. The different results of the three dimensions of ESG also further suggest that GEIR impacts ESG performance primarily in the environmental and social dimensions. A possible explanation for this is that GEIR itself focuses on the environmental and social dimensions, and firms will choose faster and more effective ways to respond to regulatory pressure in terms of both environmental performance improvement and social responsibility fulfillment. Regarding corporate governance, which is the internal institutional arrangement and the foundation of business operation, GEIR cannot currently improve its level in the short term. This result also suggests that the government can further increase the enforcement of GEIR and extend the regulation cycle to achieve better policy effects.

4.3. Robustness Test

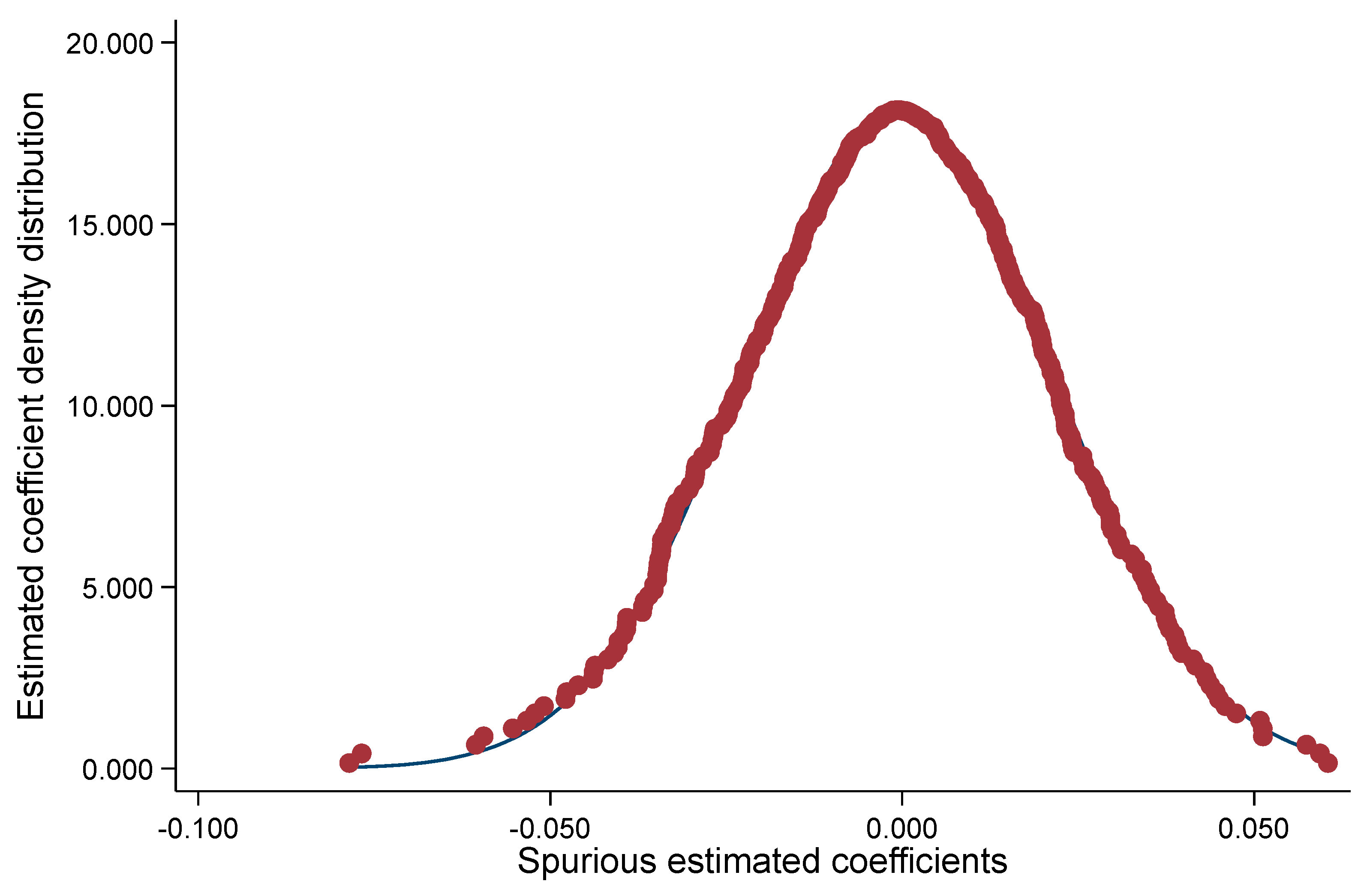

4.3.1. Placebo Test

While various control variables are included in the model (1), there is a possibility of omitted variables or unaccounted random factors that could influence the empirical outcomes. To confirm that the observed enhancement in corporate ESG performance is genuinely attributable to GEIR and to rule out the impact of other extraneous variables and random factors, a randomized experiment was constructed at the policy time-firm level by randomly “screening” heavily polluting firms and randomly generating the time of policy implementation, after which regression was run. The procedure was repeated more than 500 times, and the distribution of the estimated coefficients on the interaction terms was plotted. If the distribution of the estimated coefficients of the interaction term under the random treatment is around 0, it means that the impact effect in the baseline analysis is indeed due to the result of GEIR. As can be seen from Figure 2, the spurious estimated coefficients remain near 0, indicating that the interference of omitted variables and random factors other than GEIR on the baseline regression results is excluded, which verifies the reliability of the baseline regression results.

Figure 2.

The placebo test.

4.3.2. PSM-DID

Prior to GEIR, there could be notable disparities in the observable characteristics between firms in the treatment and control groups. Such differences might skew the baseline regression results, suggesting that improvements in corporate ESG performance stem from factors other than the regulation itself. To address potential sample selection bias and enhance comparability, PSM-DID was adopted to correct inter-sample variability, followed by a robustness test. Referring to the matching method of Wang et al. (2021) [57], the control variables in the baseline regression were used as covariates, and the 1:1 nearest neighbor matching method was used to perform year-to-year matching. As can be seen from the regression results reported in Column (1) of Table 5, the sample test results of the PSM matching method are basically consistent with those of the benchmark regression, indicating the robustness of the main conclusions.

Table 5.

The robustness test results.

4.3.3. Alternative ESG Measure

Although ESG rating agencies strive to develop comprehensive assessment systems, the specific indicators they use and their emphasis on different aspects of ESG can vary, resulting in differing ratings for the same company across different frameworks. To counteract the potential influence of rating system disparities on benchmark regression results, the ESG scores from the Bloomberg database (ESG-new) were used to replace the ESG index from the Sino-Securities Index Information Service (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., for the robustness test. Column (2) of Table 5 shows that when the explanatory variable was the Bloomberg ESG index, GEIR was still found to promote corporate ESG performance, indicating that the main findings are robust.

4.3.4. City Fixed Effects

Although a series of control variables are included in the model, it is undeniable that city-level elements, like urban pollution levels, affect the effectiveness of environmental information disclosure mechanisms; the overall maturity of ESG practices can also influence corporate ESG performance. To account for these city-level influences and ensure our findings are not confounded by such factors, city-fixed effects were further controlled for testing based on the benchmark regression. The results reported in Column (3) of Table 5 reveal that the regression coefficient is 0.091, which is significant at the 5% level. The results are basically consistent with the results of the benchmark regression, which excludes the influence of city-level factors on the empirical results.

5. Further Study

5.1. Heterogeneity Test

5.1.1. Political Relevance

While the government introduces policies and regulations to promote environmental protection by firms, firms are also actively establishing ties with government officials to seek preferential treatment [58]. Local governments may reduce the environmental enforcement of highly politically connected firms and relax the restrictions on their environmental regulations, thereby reducing the environmental regulatory pressure they face. Therefore, it was tested whether different levels of political relevance affect the role of GEIR in enhancing corporate ESG performance.

Drawing on the studies of Faccio (2006) [59], Fan et al. (2007) [60], and Xiao and Shen (2022) [58], the degree of the political relevance of firms was measured using the indicator of the political relevance (PC) level. The PC level is classified based on whether the chairman or general manager of an enterprise has served or is currently serving in political institutions such as the government and party committees. It is divided into four levels according to the central, provincial, municipal, and county levels, with respective values of 4−1; the larger the value, the higher the degree of political affiliation. Enterprises with PC levels of 1 and 2 are defined as having a low degree of political relevance, while enterprises with PC levels of 3 and 4 are defined as having a high degree of political relevance. Based on the results reported in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, the coefficients of the interaction terms are only significant in the sample group with a low degree of political relevance. Thus, it is argued that as the degree of political relevance of firms increases, the promotion effect of GEIR on corporate ESG performance is weakened. Political relations can provide a “sheltering effect”, shielding affiliated companies from stringent policy penalties or reducing the associated costs. Consequently, firms with strong political relations lack the incentive to improve their ESG performance. Moreover, establishing and maintaining such political relations is often costly, leading controlling shareholders to exploit minority shareholders and divert corporate resources—a practice known as “tunneling”—to protect their interests and offset their losses. Such practices will diminish the resources available for a company to invest in ESG initiatives. As a result, companies with extensive political connections may lack both the incentive and the resources to improve their ESG performance, undermining the effectiveness of GEIR.

Table 6.

The heterogeneity test results.

5.1.2. Investor Attention

In 2006, former UN Secretary-General Annan organized the establishment of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) to assist investors in understanding the impact of ESG on investments and to support investors in integrating ESG issues into their investment decisions. By the end of 2022, the PRI had reached 5263 signatory organizations globally. The prevalence of the green development concept has led investors to focus not only on the economic performance of companies but also on their sustainability capabilities [61,62,63,64]. ESG can reflect a company’s perceived concepts about the environment, society, and internal corporate governance. Investors can use corporate ESG performance to decide whether to invest, which has some influence on corporate ESG actions.

Based on this and drawing on the research of Yu (2012) [65], the Baidu search index of the sample companies was used to measure the investor attention of enterprises. This was performed by taking the logarithm of the total annual Baidu searches of the enterprises and dividing the sample into two groups with high and low investor attention, respectively, in accordance with the median search index of the sample enterprises. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 6 show that in the sample group with high investor attention, the interaction term is significantly positive. This indicates that GEIR has a more significant role in promoting the ESG of firms with high investor attention. Investors tend to invest in firms with high ESG scores. High levels of investor interest prompt firms to recognize that superior ESG performance is crucial for attracting investment and bolstering their competitive edge, thereby motivating them to enhance their ESG efforts to gain favor and secure future funding. Moreover, investor scrutiny of corporate ESG performance quickly communicates information to the capital markets, creating public opinion pressure that indirectly strengthens regulatory oversight. Meanwhile, increased attention from internal stakeholders like the chairman can exert direct pressure on the company. This combined internal and external pressure mechanism compels firms to actively embrace environmental and social responsibilities and to address governance issues proactively, presenting an optimal image to the capital markets and investors [66].

5.1.3. Marketization

The degree of marketization can reflect the level of maturity of a region’s capital market, with a lower degree of marketization representing the more imperfect development of the capital market. Immature capital markets are often accompanied by serious financing constraints and information asymmetry problems. In addition, the degree of marketization can also reflect the intensity of local government intervention. Local governments with a low level of marketization tend to have more redistributive resources [67], and the intensity of their intervention in the market is greater, which is more conducive to the role of policy.

Drawing on Fan’s (2011) [68] study of marketization indices, the relative marketization process of Chinese provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government were measured. The sample was divided into two groups, namely those with low and high marketization, according to the median of the marketization index of the province in which the sample firms are located. Columns (5) and (6) of Table 6 report the test results. The regression coefficients presented in Column (5) are positive and significant at the 1% level, whereas those in Column (6) are insignificant, suggesting that GEIR has a more pronounced effect on the enhancement of corporate ESG performance in regions with a lower degree of marketization. The fundamental purpose of GEIR is to encourage enterprises to disclose environmental information to urge them to protect the environment and combat environmental pollution. In regions with a low degree of marketization, the local government’s market intervention is more pronounced. The pressure from substantial government intervention may encourage firms to disclose environmental information and enhance their ESG performance to align with policy expectations, thereby facilitating GEIR at the corporate level. Furthermore, in the face of lower marketization, companies often grapple with scarce economic resources and information asymmetry. This situation incentivizes them to proactively improve their ESG performance, effectively mitigating information asymmetry by signaling their commitment to green and sustainable development. In turn, this strategy can attract more favorable policies and resource support.

5.2. Underlying Mechanisms

5.2.1. Information Disclosure Quality

According to the theoretical analysis presented in the previous section, GEIR improves the quality of information disclosure of enterprises while requiring them to disclose environmental information. High-quality information disclosure increases the transparency of corporate information and strengthens the attention and supervision of the government, shareholders, and the public toward enterprises. Strong external supervision prompts enterprises to improve their environmental performance, actively assume social responsibility, and improve their corporate governance structure to ensure that they are free from legal penalties and moral condemnation and thus demonstrate good ESG performance. Therefore, the impact of GEIR on corporate disclosure quality was directly examined.

Drawing on the research by Zhang et al. (2007) [69], the disclosure quality ratings of listed companies on the SSE and SZSE were used to measure the quality of corporate disclosure, and values of 4-1 were assigned to ratings of A-D, respectively. The regression coefficient of the interaction terms reported in Column (1) of Table 7 is 0.115 and is significant at the 1% level. This suggests that GEIR can significantly enhance the quality of corporate disclosure, thus confirming the theoretical logic of this research.

Table 7.

The mechanism analysis results.

5.2.2. Green Innovation Efficiency

The theoretical analysis provided in the previous section shows that GEIR can promote enterprises to carry out green innovation activities and that green innovation provides fundamental solutions for enterprises to reduce pollution emissions and environmental problems and improve environmental performance. Green innovation also empowers the development of green products, helps enterprises to reduce environmental risks and crises, and prompts enterprises to be responsible for the interests of society and shareholders. It also pushes them to realize the comprehensive and sustainable development of environmental and social governance, thus effectively enhancing ESG performance. Therefore, the impact of GEIR on the efficiency of corporate green innovation was directly examined.

Drawing on the research by Liu et al. (2023) [70], the ratio of the number of green patents of firms to their R&D investment was used to measure their green innovation efficiency. Column (2) of Table 7 reports the corresponding test results and reveals that the coefficient of the interaction term is 0.004 and significant at the 5% level. This supports the theoretical logic of the previous section, suggesting that GEIR can significantly improve the green innovation efficiency of firms, which in turn enhances corporate ESG performance.

6. Conclusions

This study empirically examined the impact of GEIR on corporate ESG performance as a quasi-natural experiment using data from A-share-listed heavily polluting firms. GEIR was found to improve corporate ESG performance, mainly in the environmental and social aspects. In addition, the effect of GEIR on corporate ESG performance was found to be more pronounced when the firms’ political relevance is lower, the investor attention is higher, and the marketization degree of the region in which the firms are located is lower. Furthermore, GEIR can enhance corporate ESG performance by improving the quality of corporate disclosure and the efficiency of green innovation.

This research has the following main policy implications. (1) The central government should accelerate its policy to cover all enterprises. The target enterprises of the GEIR in 2014 are key emission enterprises. For others, the policy only encourages them to disclose environmental information and does not mandate disclosure. The results show that the implementation of the policy can enhance the ESG performance of key emission enterprises, indicating that the government’s strong regulation and mandatory disclosure of environmental information have a positive effect. Promoting the policy to comprehensively cover enterprises will help to improve overall corporate ESG performance and achieve environmental pollution control and sustainable development. Moreover, across various countries, governmental backing is a catalyst for the ESG progress of firms. It is essential for governments to craft and implement relevant policies swiftly, ensuring they reach all companies and thereby encouraging local companies to enhance their ESG performance. (2) Local governments should strengthen the supervision of enterprises with a high degree of government–enterprise association. In the sample of enterprises with a high degree of political-enterprise linkage, GEIR was found to be unable to promote the enhancement of corporate ESG performance. This is possibly because local governments are likely to reduce environmental enforcement efforts for enterprises with high political linkage and to relax restrictions on their environmental regulation. Moreover, controlling shareholders may encroach on the interests of small- and medium-sized shareholders and reduce ESG resource inputs, which is not conducive to the effectiveness of the policy. Therefore, local governments should strengthen the supervision of such enterprises to ensure that the policy is implemented in all aspects. (3) Enterprises should strengthen the supervision of information disclosure quality and accelerate the progress of green innovation. The information disclosure process may experience the problem of falsification, which leads to the low quality of public information. Moreover, the long cycle and high uncertainty may lead to managers’ reluctance to carry out green innovation. However, information disclosure quality and green innovation efficiency were found to play important roles in bridging the gap between policy and corporate ESG. Ensuring information disclosure quality and green innovation efficiency also guarantees better policy effects and corporate ESG performance, which is conducive to the long-term development of enterprises.

This study was characterized by some limitations that require further exploration in future research. First, it was only found that GEIR cannot improve corporate governance. Subsequent studies can explore the reasons for this finding, and whether there are auxiliary mechanisms that can cooperate with GEIR to improve the internal governance of enterprises. Second, the research sample only included heavily polluting industries. Subsequent research can consider the introduction of sample enterprises in medium and light pollution industries, as well as energy-saving and environmental protection industries, to explore the impact of GEIR on the ESG performance of enterprises with different pollution intensities. This would provide a more comprehensive reference to promote the government to play a key role in the ESG actions of enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; Formal analysis, Y.H., X.G. and M.W.; Investigation, Y.H., X.G. and M.W.; Methodology, Y.H. and X.G.; Supervision, X.L.; Writing—original draft, Y.H. and M.W.; Writing—review and editing, Y.H. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 72374222), Social Science Achievement Evaluation Committee of Hunan Province (China) (Grant No.: XSP21YBZ168), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2023RC3048), and the Central South University Innovation-Driven Research Program (Grant No.: 2023CXQD035).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (the data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who gave valuable comments and suggestions for improving the quality of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Chang, Y. A study on the impact of ESG rating on green technology innovation in enterprises: An empirical study based on informal environmental governance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting in China. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Lin, H.; Han, W.; Wu, H. ESG in China: A review of practice and research, and future research avenues. China J. Account. Res. 2023, 16, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Wan, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, T. Institutional Investors and Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Policies: Evidence from Toxics Release Data. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4901–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, X.; Fu, X. Varieties in state capitalism and corporate innovation: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L. Transmission Effects of ESG Disclosure Regulations Through Bank Lending Networks. J. Account. 2023, 61, 935–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A.; Saleh, A.; Eliwa, Y. Does mandating ESG reporting reduce ESG decoupling? Evidence from the European Union’s Directive 2014/95. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1305–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ge, C.; Li, X.; Duan, X.; Yu, T. Configurational analysis of environmental information disclosure: Evidence from China’s key pollutant-discharge listed companies. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, S. The effects of proprietary information on corporate disclosure and transparency: Evidence from trade secrets. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 66, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Tian, X. Regulatory Transparency and Regulators’ Effort: Evidence from Public Release of the SEC’s Review Work. J. Account. 2024, 62, 229–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, B.; Gold, A.; Gold, S. ESG Disclosure and Idiosyncratic Risk in Initial Public Offerings. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lai, J.; Jie, S. Quantity and quality: The impact of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance on corporate green innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.E.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG Investing: How ESG Affects Equity Valuation, Risk, and Performance. J. Portfolio. Manag. 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.A.; Wang, Y. Board of directors network centrality and environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 965–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, T.; Cremers, M.; Renneboog, L. Shareholder Engagement on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 777–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L. Senior management’s academic experience and corporate green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Social. Chang. 2021, 166, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, V.; Verga Matos, P.; Miranda Sarmento, J.; Rino Vieira, P. M&A activity as a driver for better ESG performance. Technol. Forecast. Social. Chang. 2021, 175, 121338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G.; Mallidis, I.; Sariannidis, N.; Konteos, G. The impact of corporate governance attributes on environmental and social performance: The case of European region excluding companies from the Eurozone. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 3489–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; González-Bueno, J.; Guijarro, F.; Oliver, J. Forecasting the Environmental, Social, and Governance Rating of Firms by Using Corporate Financial Performance Variables: A Rough Set Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Maso, L.D.; Liberatore, G.; Mazzi, F.; Terzani, S. Role of country- and firm-level determinants in environmental, social, and governance disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, M.; McBrayer, G.A. Natural Disasters, Risk Salience, and Corporate ESG Disclosure. J. Corp. Financ. 2022, 72, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Tan, Q.; Pang, J. Bless or curse, how does extreme temperature shape heavy pollution companies’ ESG performance-Evidence from China. Energy. Econ. 2024, 131, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qi, B.; Li, Y.; Hossain, M.I.; Tian, H. Does institutional commitment affect ESG performance of firms Evidence from the United Nations principles for responsible investment. Energy. Econ. 2024, 130, 107302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Bai, D.; Chen, X. Can crude oil futures market volatility motivate peer firms in competing ESG performance? An exploration of Shanghai International Energy Exchange. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Le, Q.; Peng, M.; Zeng, H.; Kong, L. Does central environmental protection inspection improve corporate environmental, social, and governance performance? Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 2962–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xue, S. Greening of Tax System and Corporate ESG Performance: A Quasi-natural Experiment Based on the Environmental Protection Tax Law. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 48, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R.; Abweny, M.; Benjasak, C.; Nguyen, D.T.K. Financial sanctions and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: A comparative study of ownership responses in the Chinese context. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, R.; Geng, Y.; Ren, X. Green bond issuance and corporate ESG performance: The perspective of internal attention and external supervision. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, J. How does fintech prompt corporations toward ESG sustainable development? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2024, 131, 107387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Cao, H. Does green credit policies improve corporate environmental social responsibility: The perspective of external constraints and internal concerns. China. Ind. Econ. 2022, 4, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Fang, Q.; Long, W. Carbon Emission Regulation, Corporate Emission Reduction Incentive and Total Factor Productivity: A Natural Experiment Based on China’s Carbon Emission Trading System. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Chen, K.; Sun, C.; Lyu, C. Does environmental pollution liability insurance promote environmental. Energy Econ. 2023, 118, 106493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A.; Frost, T.; Cao, H. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure: A literature review. Br. Account. 2023, 55, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Li, B.; Chang, M. Carbon Emissions and TCFD Aligned Climate-Related Information Disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 967–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detlor, B.; Hupfer, M.E.; Ruhi, U.; Zhao, L. Information quality and community municipal portal use. Gov. Inf. Q. 2013, 30, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, J. Transparency of Transparency: The pro-active disclosure of the rules governing Access to Information as a gauge of organisational cultural transformation. The case of the Swiss transparency regime. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, K. The ‘Masking Effect’ of Social Responsibility Disclosure and the Risk of Collapse of Listed Companies: A DID-PSM Analysis of Chinese Stock Markets. J. Manag. 2017, 11, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. The Economic Relevance of Environmental Disclosure and its Impact on Corporate Legitimacy: An Empirical Investigation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Kong, D.; Tao, Y. Evaluation on the Effect of the Pilot Reform of the Social Credit System: From the Perspective of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 48, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, P. Transparency: The Key to Better Governance? Proceedings of the British Academy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2008, 25, 561–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, S.; Fan, Z. Modeling the role of environmental regulations in regional green economy efficiency of China: Empirical evidence from super efficiency DEA-Tobit model. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Bashir, M.F.; Shahbaz, M. Do renewable energy, environmental regulations and green innovation matter for China’s zero carbon transition: Evidence from green total factor productivity. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, M.; Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Ning, L. Environmental Legitimacy, Green Innovation, and Corporate Carbon Disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Govindan, K.; Xie, X.; Yan, L. How to drive green innovation in China’s mining enterprises? Under the perspective of environmental legitimacy and green absorptive capacity. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, Y. Green Innovation and Performance: The View of Organizational Capability and Social Reciprocity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huo, J.; Zou, H. Green process innovation, green product innovation, and corporate financial performance: A content analysis method. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhu, Q. How Can Green Innovation Solve the Dilemmas of “Harmonious Coexistence”? J. Manag. 2021, 37, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, Y.; Li, X.; Li, S. Does improvement of environmental information transparency boost firms’ green innovation? Evidence from the air quality monitoring and disclosure program in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Lyu, X. Responsible Multinational Investment: ESG and Chinese OFDI. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.; Zhang, D.; Ji, Q. Common Institutional Ownership and Corporate ESG Performance. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginglinger, E.; Raskopf, C. Women directors and E&S performance: Evidence from board gender quotas. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 83, 102496. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y. Effectiveness Measurement of Green Finance Reform and Innovation Pilot Zone. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2021, 38, 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Shen, S. To pollute or not to pollute: Political connections and corporate environmental performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2022, 74, 102214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M. Politically Connected Firms. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.P.H.; Wong, T.J.; Zhang, T. Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 84, 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, L.T. Presidential Address: Sustainable Finance and ESG Issues— Value versus Values. J. Financ. 2023, 78, 1837–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Gu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. Clustered institutional investors, shared ESG preferences and low-carbon innovation in family firm. Technol. Forecast. Social. Chang. 2023, 194, 122676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Monfort, A.; Chen, F.; Xia, N.; Wu, B. Institutional investor ESG activism and corporate green innovation against climate change: Exploring differences between digital and non-digital firms. Technol. Forecast. Social. Chang. 2024, 200, 123129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, N.B.; Chalwati, A.; Hmaied, D.; Khizer, A.M.; Trabelsi, S. Do foreign institutions avoid investing in poorly CSR-performing firms? J. Bank. Financ. 2024, 157, 107029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, B. Limited Investor Attention and Stock Returns-An Empirical Study Using Baidu Index as Attention Levels. J. Financ. Res. 2012, 8, 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhou, Y. Environmental Information Asymmetry, Institutional Investors’ Corporate Site Visits and Corporate Environmental Governance. Stat. Res. 2019, 36, 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, R. Intelligent Manufacturing, Degree of Marketization and Enterprise Operational Efficiency: A Text Analysis Based on Annual Reports of Listed A-share Manufacturing Firms. Account. Res. 2022, 11, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Ma, G. Contribution of Marketization to China’s Economic Growth. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.; Yuan, Q. Does improved disclosure quality of listed companies improve corporate performance. Account. Res. 2007, 10, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Pan, H.; Li, P.; Feng, Y. Impact and mechanism of digital transformation on the green innovation efficiency of manufacturing enterprises in China. China. Soft. Sci. Mag. 2023, 4, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).