Abstract

This study examines the effect of job satisfaction on life satisfaction, focusing on the mediating effect of positive affect moderated by COVID-19. The participants were 287 wage-earning graduates under 35 years of age who had graduated from culinary arts programmes and participated in the 2017–2019 Graduates Occupational Mobility Survey conducted by the Korea Employment Information Service. Hypotheses were tested using Hayes’ MACRO process models 4 and 8. The results are summarised as follows. First, higher extrinsic and intrinsic job satisfaction among culinary graduates was associated with increased positive affect and life satisfaction. Second, positive affect partially mediated the relationship between job satisfaction and life satisfaction. Finally, the indirect effect of positive affect on the relationship between extrinsic job satisfaction and life satisfaction decreased after the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic. Therefore, the industry should develop systems and programmes to enhance both extrinsic job satisfaction (such as wages and working hours) and intrinsic job satisfaction (such as personal growth, development potential, and a sense of accomplishment) among young chefs. Furthermore, industries and government agencies should prepare sustainable measures to maintain job satisfaction, positive affect, and life satisfaction among employees during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

Low job satisfaction (JS), which leads to turnover intention or actual turnover behaviour among young people, has emerged as a significant social issue, not only in terms of individual time consumption but also from the perspective of national human resource management [1]. Reasons for job turnover among youth include wage dissatisfaction, job security, job mismatch, dissatisfaction with the work environment, workplace relationship problems, and unfair HR systems [2,3]. According to the Deloitte Global 2024 MZ Generation Survey [4], 65% of millennials perceive that they are not sufficiently recognised or compensated for their work. There is a growing trend toward rejecting jobs or companies that do not align with their values. Considering these aspects, JS should be regarded as a significant factor in addressing the social issue of increasing youth unemployment or the high rate of first job departures after college graduation [5].

JS among employees in the food service industry is a crucial factor in enhancing sustainable service quality, which directly leads to customer satisfaction and increased sales, thereby securing a continuous competitive edge over other companies [6]. However, working conditions for employees in the food service industry are becoming increasingly harsh because of the economic downturn caused by COVID-19 [7]. Culinary professionals, especially those who majored in culinary arts in higher education institutions, face unexpected difficulties in their actual work environments. This is despite the development of the food service industry. The job of a chef has long been recognised as hazardous, with occupational lung cancer identified in 2021 and a history of harmful working conditions. Kim and Lee [8] found that slips, burns, and musculoskeletal disorders have been unresolved occupational hazards for over 20 years among culinary workers and that occupational injury rates among culinary professionals under the age of 25 years are higher than those in other occupations. Additionally, culinary workers experience psychological instability because their workplace environments, including wages, promotions, and welfare systems, do not meet their personal needs and values [9,10]. These issues can lead to job dissatisfaction and turnover behaviour [6,11]. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the impact of JS among chefs on their life satisfaction (LS) and positive affect (PA), while proposing sustainable human resource management strategies for the food service industry in the post-COVID-19 era.

JS has a strong influence on LS [12]. LS refers to the degree of satisfaction with one’s overall life, and individuals who are satisfied with their current lives are more likely to lead a satisfying life in future professional scenarios [13,14,15]. Thus, amid the increasing interest in a sustainable quality of life, it is challenging for individuals to lead a happy life, not merely in terms of personal experiences but also in the work environment. According to Weiss and Cropanzano’s [16] affective events theory, aspects of the organisational environment create positive or negative affective events that trigger emotional responses from organisational members, leading to corresponding attitudes and behaviours [17]. An important aspect of this theory is that by promoting positive affective events and minimising negative ones, organisations can enhance employees’ emotional well-being, thereby sustainably improving overall organisational performance. The impact of PA on organisational members’ behaviours or attitudes can be inferred from Fredrickson’s [18] broaden-and-build theory. According to this theory, PA acts as an upward spiral that fosters individual happiness and growth and promotes organisational prosperity. This suggests that PA benefits both individuals and organisations by fostering positive behaviours and performance within organisations.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led college students on the verge of employment to experience social isolation due to bans on gatherings and self-quarantine, impacting their JS, affect, and LS [19]. Goh and Ahn [20] found that LS among residents of the Seoul metropolitan area in Korea decreased during the second wave of COVID-19 compared to that during the early pandemic, with greater declines observed among women and young people. Nevertheless, in the hospitality industry, most studies on JS before and after COVID-19 have focused on turnover intention or organisational commitment as outcome variables [21], paying little attention to the broader concept of happiness, or LS [22]. Existing studies on culinary professionals have mainly focused on extrinsic factors, such as working conditions and welfare benefits [6,7,23], with few analysing the effects of JS during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, to comprehensively understand JS among culinary graduates, it is necessary to investigate the relationship between emotional states and LS considering both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Additionally, it is necessary to compare the relationships between JS, PA, and LS before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to develop future response strategies for similar epidemics. Such research will enable a more balanced and sustainable approach to organisational HR management and policymaking, contributing to greater JS among culinary graduates and thereby enhancing their overall quality of life and psychological well-being.

Therefore, this study aims to empirically analyse the mediating role of PA in the relationship between JS and LS among culinary graduates who participated in the Graduates Occupational Mobility Survey (GOMS). Furthermore, we analysed the differences in these relationships before and after the onset of COVID-19. The findings of this study provide important foundational data for developing strategies to positively influence the psychological state of culinary graduates within organisations, thereby enhancing their LS.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Job Satisfaction

JS encompasses satisfaction with both the job and work environment and differs from job role satisfaction, which specifically refers to satisfaction with the job itself [1]. Kong et al. [21] define JS as employees’ overall positive attitude toward their jobs. Choi and Seo [24] describe JS as a multidimensional emotion that includes subjective feelings about work, economic rewards, interpersonal relationships, and the environment. Interest in JS has increased in a societal context that emphasises the quality of life, as it can serve as a qualitative measure of employment outcomes for college graduates beyond objective employment-related indicators, such as employment status or wages [25].

Depending on the research objective, JS can be used as a predictor or outcome variable that affects the measurement dimensions. Studies that use JS as an outcome variable [26,27] typically measure JS as a single-dimensional construct, reflecting the tendency to evaluate JS as simple overall contentment. For example, Tran et al. [28] found that job characteristics, training opportunities, work environment, autonomy, income, and promotions significantly impact JS among Gen Z employees. In contrast, studies that use JS as a predictor variable measure it using a more complex multidimensional structure, often comprising two or more dimensions. A two-dimensional structure generally distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction [29]. Intrinsic JS (IJS), which is closely related to internal motivation, refers to the satisfaction derived from positive emotions and experiences associated with the job itself, such as aptitude and interest, the social reputation of the job, autonomy, and authority, job content, growth potential, training and development, and the work environment [12,30]. Extrinsic JS (EJS) refers to satisfaction related to material benefits and the social value of a job, such as welfare benefits, wages, working hours, HR systems, and job security [12,31]. Additionally, many studies that use panel data employ individual items to measure JS as a single dimension. For example, Jo and Lee [32] analysed the relationship between JS and turnover intention without dimension reduction, using all 15 JS items from the Youth Panel Survey. Similarly, Cha et al. [33] utilised 14 items from the 2019 GOMS data to measure JS as 14 independent variables, analysing its impact on job adaptation among college graduates. This study aimed to measure JS using items from the GOMS via Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensions. This approach ensures the validity of the JS indicators and analyses their impact on subsequent variables.

2.2. Positive Affect

Affect is a concept that includes feelings, sensations, thoughts, and behaviours triggered by conscious and unconscious evaluations of events related to an individual’s experiences or goals [34]. Affects can be broadly divided into PA and negative affect. In particular, with the rise of positive psychology, recognition of the function of PA has spread, and empirical evidence has shown that PA plays a critical role in human growth and prosperity beyond hedonic value [35]. Lee and Oh [36] define PA as the degree of positive emotional experience or arousal in office workers. Kim et al. [37] define PA as the emotions felt when encountering something good or beneficial. These definitions highlight the multifaceted nature of PA and underscore its importance in both personal well-being and professional environments.

PA is influenced by several factors. Office workers can be significantly influenced by job-related factors. Lee and Oh [36] demonstrated that the PA of office workers is positively influenced by job efficacy and job meaningfulness (the degree to which the purpose and content of the job align with one’s values and are deemed valuable); however, this PA does not affect LS. Satuf et al. [38] emphasised the importance of maintaining a positive evaluation of one’s work in their study of adult workers in Portugal, noting that JS has protective effects on health, happiness, subjective well-being, and self-esteem. Zhang and Jiang [17] found that workplace friendships positively influence PA, which in turn positively influences job crafting, a process in which employees alter their work to make it more meaningful. Kim et al. [37] found that hindrance stressors that unnecessarily frustrate and hinder individual growth and goal attainment at work have a negative relationship with PA. Conversely, challenge stressors at work, such as heavy workload and time pressure, which must be overcome to learn and achieve something, do not affect PA. Previous studies have focused on employees in various professions; however, more research is needed to explicitly focus on culinary arts graduates. This study sought to differentiate itself by examining the impact of JS on PA within this specialised occupational group. Based on previous studies, the following hypotheses were established to explore the impact of JS on the PA of culinary arts graduates:

H1.

The JS of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on PA.

H1a.

The IJS of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on PA.

H1b.

The EJS of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on PA.

2.3. Life Satisfaction

Scholars studying LS distinguish between top-down perspectives, which emphasise internal factors such as personality traits, and bottom-up perspectives, which emphasise external factors such as work, family, and social relationships [22,39]. Because researchers view LS from different perspectives, it is difficult to summarise it in a single sentence. Lyubomirsky et al. [40] define LS as the degree of subjective content formed through the interaction between personality traits and external factors. Choi [41] defines LS as the degree of subjective contentment perceived through various elements surrounding an individual. Choo [42] defines LS as the evaluation of one’s life based on how individuals feel and perceive their own happiness. These definitions reflect the complexity of LS and highlight its significant impact on an individual’s overall well-being.

Factors influencing LS include the following: Kwon [43] found that JS, health status perception, and relationships with neighbours, along with social and economic factors and personal characteristics such as income, influenced the overall quality of life in a study of Gyeonggi-do residents. In a study exploring the factors affecting youth LS using random forest, Lee [44] found that as young people’s job values increased, their LS decreased. This was attributed to the imbalance between high job values that consider not only material rewards and working conditions but also achievement, aptitude, and interest, as well as the reality faced by young people. Park [45] found that among the job characteristics of hotel culinary workers, autonomy had the greatest positive effect on quality of life, and job identity, diversity, and importance also positively influenced quality of life. Thus, from a bottom-up perspective, LS is related to external factors such as job or work environment characteristics. Sironi [46] argued that, although there is a correlation between high JS levels and well-being, this relationship could potentially be bidirectional. In other words, if an increase in JS affects optimal well-being, an opposite relationship can be hypothesised. In contrast, Erdogan et al. [22] conducted a meta-analysis of the relationship between LS and JS and found that, in most studies, JS was treated as an antecedent of LS and was positively related to LS. A review of previous studies suggests that JS can act as an antecedent of LS. In this respect, this study treats culinary arts graduates’ LS as an outcome variable of JS.

Several studies have consistently demonstrated the effects of JS on LS. Ariza-Montes et al. [47] analysed data from the sixth edition of the European Social Survey (ESS) in 2013 and found that JS among a group of chefs positively influenced LS. Choi [41] found that LS among graduates from tourism-related departments of technical colleges was lower than that among graduates from other majors and that IJS had a greater impact on LS than EJS. Rhee et al. [48] found that a higher JS increases subjective well-being, which is the overall subjective satisfaction with one’s current life. Based on previous studies, the following hypotheses were established to explore the impact of JS on culinary arts graduates’ LS:

H2.

The JS of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on LS.

H2a.

The IJS of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on LS.

H2b.

The EJS of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on LS.

According to the broaden-and-build theory of PA, PA is an important factor influencing happiness [34]. Developing and promoting PA is more effective in enhancing LS than alleviating negative affect [49]. Busseri [50] conducted a meta-analysis of the correlations between PA, negative affect, and LS, and found a positive correlation between PA and LS. He claimed that the association among these three variables was globally generalisable, as the results did not vary according to sample characteristics. In their study of employees in the food service industry, Jung and Lee [51] found that PA positively influenced work volition, self-efficacy, and LS. Moon [34] found that social trust enhances PA, which in turn increases happiness. Conversely, social trust has been shown to reduce negative affect, which decreases happiness. Qiyuan et al. [52] argue that the ultimate goal of an organisation should be to develop and manage programmes that enhance the PA, passion, and job crafting of its members, ultimately leading to increased LS. In their study of logistics employees at a Chinese university, Zheng et al. [53] found that positive attitudes toward life and work and high job engagement improved well-being, whereas negative traits and job-related rumination decreased it. Thus, the emotional state of culinary arts graduates plays an important role in their psychological well-being and LS.

H3.

The PA of culinary arts graduates will have a positive (+) effect on LS.

2.4. The Mediating Effect of Positive Affect in the Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction, and the Impact of COVID-19

Based on Weiss and Cropanzano’s [16] affective events theory, which posits that various events occurring within the workplace stimulate individual emotions and influence attitudes and behaviours, this study proposes that culinary arts graduates’ PA mediates the relationship between JS and LS. Reviewing previous studies related to the mediation of affect or emotional variables in the relationship between job or workplace environment and LS, the following can be observed: Kang and Jang [54] found that while job overload does not directly affect LS, it indirectly lowers it by preventing sufficient rest and necessitating continued engagement in work-related activities. Wang et al. [55] found that PA partially mediated the relationship between resilience, transformational leadership, and work engagement. Karabati et al. [56] found that rumination mediates the relationship between JS and subjective well-being among office workers in the United States and Turkey, indicating that less satisfied employees ruminate more, leading to lower satisfaction and happiness. Hayat and Afshari [57], in their study on hotel managers and employees in Punjab, Pakistan, concluded that the corporate social responsibility initiatives of hospitality companies not only directly enhance employee well-being but also improve employees’ PA by increasing organisational commitment and JS. Liu et al. [58] found that JS was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms and that increasing JS sequentially enhanced subjective well-being and LS, thereby reducing depressive symptoms. Kim et al. [59] found that appropriate compensation and job stability for social workers do not directly affect LS but indirectly influence it through family support and work–life balance. Kim and Shin [60] found that ideal self-image congruence for leisure sports among employees does not directly effect happiness but positively influences happiness through PA. Thus, this study aimed to identify the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between JS and LS among culinary arts graduates, proposing the following hypothesis:

H4.

The PA of culinary arts graduates will mediate the relationship between JS and LS.

H4a.

The PA of culinary arts graduates will mediate the relationship between IJS and LS.

H4b.

The PA of culinary arts graduates will mediate the relationship between EJS and LS.

Furthermore, given the emotional stress experienced by culinary arts graduates during the pandemic, it is essential to understand how these emotional dynamics were affected during this period. The COVID-19 pandemic was one of the worst pandemics in human history and the first to be extensively studied scientifically in all dimensions [61]. The pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to the hospitality industry. Strategies to prevent the spread of COVID-19 led to temporary closures and decreased demand in the hospitality industry [62]. In South Korea, after the first confirmed COVID-19 case on 20 January 2020, the cumulative number of confirmed cases was approximately 20,182 as of 1 September 2020 (the survey period for the 2019 GOMS used in this study). Consequently, the South Korean government reinforced measures such as social distancing and self-quarantine. COVID-19 has brought about significant changes in our daily lives, affecting our personal and household economies, physical and mental health, employment, consumption, and social relationships. In particular, COVID-19 has substantially impacted the labour market, leading to reductions in the number of employed persons, working hours, wages, and increased job losses [63,64]. Pérez-Fuentes et al. [65] indicated that the perception of threat from COVID-19 increased negative emotions such as sadness, depression, anxiety, anger, and hostility. This finding implies that the pandemic has profoundly affected emotional well-being worldwide.

The pandemic has changed the lives of university students entering adulthood. Students are unable to fully enjoy university life due to COVID-19, leading to a decline in academic quality, social isolation anxiety, and health and safety concerns [66]. The stress experienced in this altered daily life due to COVID-19 not only negatively impacts people’s psychology but also poses threats to mental health. Hwang et al. [67] conducted a short-term longitudinal study in April and August 2020 and observed that higher levels of negative affect, depression, and suicidal ideation in April were associated with higher levels of these symptoms in August. Kim [68] found that perceived stress due to COVID-19 directly increased emotional and behavioural problems, and indirectly increased these problems by reducing flourishing. Kim et al. [63] reported that, while the overall JS of regular wage workers did not change before and after COVID-19, the JS of temporary, daily wage workers and specially employed workers decreased after COVID-19. Similarly, the LS of regular and temporary wage workers did not change before and after COVID-19, but the LS of specially employed workers decreased after the outbreak of COVID-19. Wang et al. [69] used data from the UK Household Longitudinal Panel Study from 2018 to February 2020 and April 2020 to demonstrate that changes in employment status, working hours, and furlough have different effects on the mental health of men and women. At the onset of the pandemic, the overall mental health of women declined significantly regardless of their employment status. Yasin et al. [70], in a meta-analysis of nurses’ JS during the COVID-19 pandemic, found that JS differed by country according to economic and cultural differences, with South Korea having significantly lower JS due to high burnout and workload rates among healthcare workers compared to other countries. Li et al. [71] found that nursing students’ risk perceptions positively influenced their professional commitment during COVID-19, with psychological capital buffering negative emotions. Based on these studies, the following hypotheses were proposed to explore the differences in the relationships between JS, PA, and LS among culinary arts graduates before and during the pandemic:

H5.

The COVID-19 outbreak will moderate the relationship between JS and PA and between JS and LS.

H5a.

The COVID-19 outbreak will moderate the relationship between IJS and PA.

H5b.

The COVID-19 outbreak will moderate the relationship between IJS and LS.

H5c.

The COVID-19 outbreak will moderate the relationship between EJS and PA.

H5d.

The COVID-19 outbreak will moderate the relationship between EJS and LS.

H6.

PA will have a moderated mediating effect on the relationship between JS and LS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H6a.

PA will have a moderated mediating effect on the relationship between IJS and LS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H6b.

PA will have a moderated mediating effect on the relationship between EJS and LS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Methods

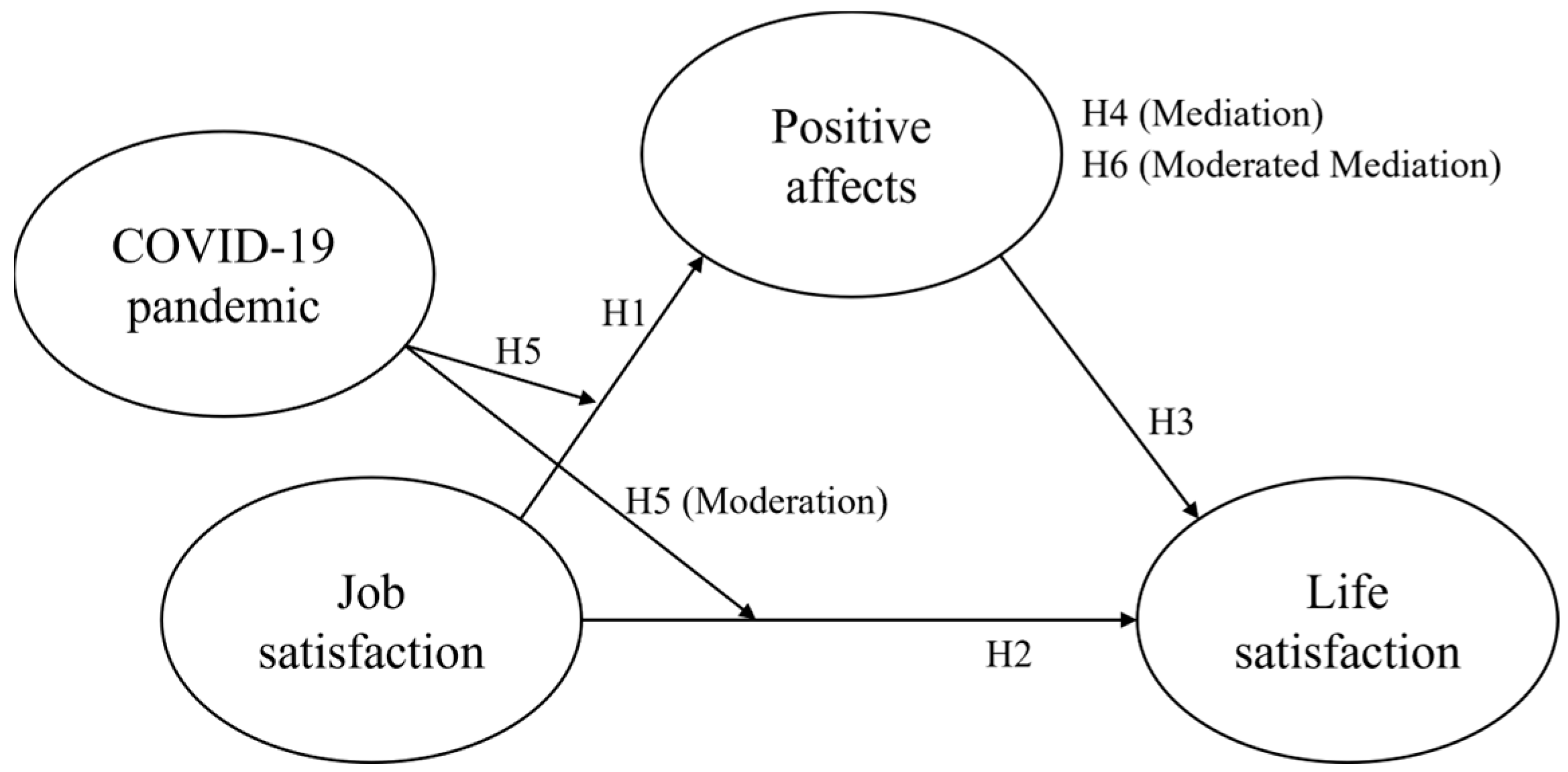

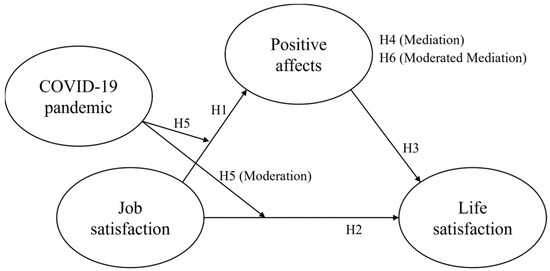

3.1. Research Model

This study aims to examine the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between JS and LS among culinary arts graduates. Additionally, it seeks to understand how these relationships differ between the pre-COVID-19 period and during the pandemic. To achieve this objective, the influence relationships were schematised based on previous studies, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.2. Research Participants

To test this study’s hypotheses, we used data from the GOMS provided by the Korea Employment Information Service. The GOMS is a survey conducted jointly by the Ministry of Employment and Labor and the Korea Employment Information Service. It employs stratified sampling techniques, including quota sampling and random sampling, to secure a representative sample of college graduates nationwide. This systematic and objective methodology ensures high validity and reliability of the data, making it a reputable source for research. As indicated in Table 1, the participants in the 2019 GOMS were February 2019 or August 2018 graduates. The survey was conducted in September 2020, 1.5 years after graduation, and the results were released in February 2022. Over a span of three years, the total number of college graduates from culinary or confectionery-related programmes was 412, of whom 304 were wage workers who responded to the JS items. After excluding 17 respondents over the age of 35 from the initial 304, the final analysis sample comprised 287 respondents.

Table 1.

Summary of research participants.

The demographic profiles of the participants are presented in Table 2. Of the 297 respondents, 113 (39.4%) were from the 2017 GOMS, 93 (32.4%) from the 2018 GOMS, and 81 (28.2%) from the 2019 GOMS. Regarding the type of university, 213 participants (74.2%) were graduates from junior colleges and 74 participants (25.8%) were graduates from four-year universities. In terms of gender, 159 (55.4%) were male and 128 (44.6%) were female. Regarding age, 178 respondents (62%) were between 20 and 24 years old, 104 (36.2%) were between 25 and 29 years old, and 5 respondents (1.8%) were 30 years or older.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants.

3.3. Measurement Tools

To measure the JS of culinary arts graduates, this study used items from the GOMS dataset targeting wage workers. The GOMS dataset includes 14 items that measure current JS and has been frequently employed in studies assessing JS among college graduates [72,73]. These items consist of aspects such as aptitude and interest, job social reputation, job autonomy and authority, job content, career development potential, training, working environment, welfare benefits, salary, working hours, personnel systems, and job security. However, based on the study by Kim et al. [31], which highlighted the ambiguity in defining whether interpersonal relationships pertain to those within or outside the job, this study excluded the interpersonal relationship item and used 13 items to measure JS. JS was measured using a 5-point Likert scale. In the study by Park and Chung [73], Cronbach’s alpha values for the IJS and EJS were 0.848 and 0.816, respectively. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.906 for IJS and 0.815 for EJS, indicating that the reliability in this study is either higher than or comparable to that in previous research.

To measure the PA of culinary arts graduates, this study used items related to happiness from the GOMS dataset. The happiness scale used in the GOMS is commonly employed in studies assessing college graduates’ subjective well-being and emotional states [14,74]. PA was measured based on the frequency of feelings of pleasure, happiness, and comfort experienced during the past month. LS was measured using three related items that were included in the happiness measurement tool from the GOMS dataset. PA and LS were measured using a 7-point Likert scale. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha values for PA and LS were 0.939 and 0.895, respectively, indicating the high reliability of the measurements.

Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic period, as shown in Table 1, there were no confirmed COVID-19 cases during the 2017 and 2018 GOMS survey periods; thus, these periods are classified as pre-pandemic. Conversely, during the 2019 GOMS survey period, approximately 20,182 COVID-19 cases were reported. Therefore, this period is classified as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, university graduates who participated in the 2017 and 2018 GOMS surveys were employed 1.5 years after graduation, before the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, university graduates who participated in the 2020 GOMS survey were employed as wage workers 1.5 years after graduation, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4. Statistical Analysis Methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0. First, frequency analysis was performed to identify the participants’ demographic characteristics. Second, PCA was conducted to verify the validity of the variable set in this study, and reliability was verified using Cronbach’s alpha values. Third, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to analyse the correlations between JS, PA, and LS. Finally, to examine the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between JS and LS among culinary arts graduates, as well as the moderated mediating effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study hypotheses were tested using Hayes’ [75] Process Macro Models 4 and 8. In the first stage, the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between JS and LS was tested using Model 4. In the next stage, the significance of the indirect effect of PA before and during the COVID-19 pandemic was examined using Model 8. Finally, a simple slope analysis was conducted for the JS subfactors where moderated mediation was significant to explore the differences in the indirect effect based on the moderator variable.

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability Analysis of Measurement Items

4.1.1. Validity and Reliability of JS

The results of the PCA conducted to verify the validity of the survey items measuring JS are presented in Table 3. The PCA showed a KMO value of 0.921, indicating that the correlations among the items are well explained by the other items. Additionally, before performing the PCA, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was conducted to check whether the correlations among the variables were significant. The results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity showed that the Chi-square value (χ2 = 2012.377, p < 0.001) was statistically significant, indicating that there are correlations among the variables. Therefore, the survey items measuring JS among culinary arts graduates were confirmed to be suitable for PCA.

Table 3.

Results of the validity and reliability analysis of job satisfaction.

The PCA results showed that JS was classified into two principal components. Based on the core concept of the survey items, the first principal component was named IJS and the second principal component was named EJS. The eigenvalue for IJS was 4.480, which explained 34.459% of the total variance. The eigenvalue for EJS was 3.346, which explained 25.742% of the total variance. The reliability analysis results showed that Cronbach’s alpha values for the IJS and EJS were 0.906 and 0.815, respectively. This indicates that each survey item reflects the respective concepts well.

4.1.2. Validity and Reliability of PA and LS

The results of the PCA conducted to verify the validity of the survey items measuring PA and LS are presented in Table 4. The PCA showed a KMO value of 0.854, indicating that the correlations among the items are well explained by the other items. Additionally, the results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 1529.439, p < 0.001) indicated that there are correlations among the variables, confirming that the data are suitable for PCA. The PCA results showed that the eigenvalue for PA was 2.653, accounting for 44.218% of the total variance. The eigenvalue for LS was 2.525, which explained 42.090% of the total variance. The reliability analysis results showed that Cronbach’s alpha values for PA and LS were 0.939 and 0.895, respectively. This indicates that each survey item reflects the respective concepts well.

Table 4.

Results of the validity and reliability analysis of positive affect and life satisfaction.

4.2. Correlation between Variables

The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 5. Focusing on the dependent variables PA and LS, the correlations between the variables were as follows: PA was positively correlated with IJS (r = 0.280) and EJS (r = 0.376). Additionally, LS was positively correlated with IJS (r = 0.383), EJS (r = 0.457), and PA (r = 0.671). Because no correlation coefficient was above 0.8, there was no issue of multicollinearity among the variables.

Table 5.

Results of the correlation analysis between variables.

4.3. The Mediating Effect of PA in the Relationship between JS and LS

The results of testing the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between IJS and LS among culinary arts graduates are presented in Table 6. First, the regression model of hypothesis 1a, which examined the effect of the independent variable (IJS of culinary arts graduates) on the mediating variable (PA), was statistically significant (F = 24.244, p < 0.001), with an explanatory power of 28.0%. When examining the relationship between these two variables, IJS was found to have a positive effect on PA (B = 0.489, p < 0.001). Next, the regression models for hypotheses 2a and 3, which examined the effects of IJS and PA on the dependent variable (LS), were found to be statistically significant (F = 137.024, p < 0.001) with an explanatory power of 49.1%. The relationships between the variables indicated that IJS and PA had positive effects on LS (B = 0.34, p < 0.001) and that PA also had a positive effect on LS (B = 0.561, p < 0.001). Finally, to confirm the statistical significance of the indirect effect of PA on the relationship between IJS and LS, a bootstrapping test was conducted 5000 times at a 95% confidence interval. The size of the indirect effect was 0.275, and because the LLCI (0.123) and ULCI (0.299) did not include zero, the indirect effect was significant. This means that the IJS of culinary arts graduates had a significant effect on LS through the mediation of PA.

Table 6.

The mediating effect of PA in the relationship between IJS and LS.

The results of testing the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between EJS and LS among culinary arts graduates are presented in Table 7. First, the regression model of hypothesis 1b, which examined the effect of the independent variable (EJS of culinary arts graduates) on the mediating variable (PA), was found to be statistically significant (F = 46.964, p < 0.001), with an explanatory power of 37.6%. Examining the relationship between these two variables, EJS was found to have a positive effect on PA (B = 0.696, p < 0.001). Next, the regression models for hypotheses 2b and 3, which examined the effects of EJS and PA on the dependent variable (LS), were also found to be statistically significant (F = 141.127, p < 0.001) with an explanatory power of 49.8%. The relationships between the variables indicated that EJS (B = 0.405, p < 0.001) and PA (B = 0.533, p < 0.001) positively affected LS. Finally, the indirect effect (B = 0.371) of PA on the relationship between EJS and LS was significant, as LLCI (0.222) and ULCI (0.534) did not include a 0. This means that the EJS of culinary arts graduates had a significant effect on LS through the mediation of PA.

Table 7.

The mediating effect of PA in the relationship between EJS and LS.

4.4. Moderating Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Relationship between JS and PA, and JS and LS

To test whether the occurrence of COVID-19 moderates the relationship between JS and PA, as well as the relationship between JS and LS, we applied Process Macro Model 8. The results are summarised in Table 8.

Table 8.

Moderating effect of the COVID-19 outbreak on the relationship between variables.

First, the interaction term between EJS and the occurrence of COVID-19 was found to have a significant effect on the mediating variable, PA (B = −0.268, p < 0.05). This indicates that the effect of EJS on PA was moderated by the occurrence of COVID-19. However, the interaction between EJS and the occurrence of COVID-19 did not have a significant effect on LS (B = 0.083, p > 0.05). In contrast, the interaction term between IJS and the occurrence of COVID-19 did not have a significant effect on PA (B = −0.034, p > 0.05), indicating that the effect of IJS on PA was not moderated by the occurrence of COVID-19. Similarly, the interaction between IJS and COVID-19 did not significantly affect LS (B = 0.068, p > 0.05). This suggests that the effect of IJS on LS did not differ before or after the occurrence of COVID-19.

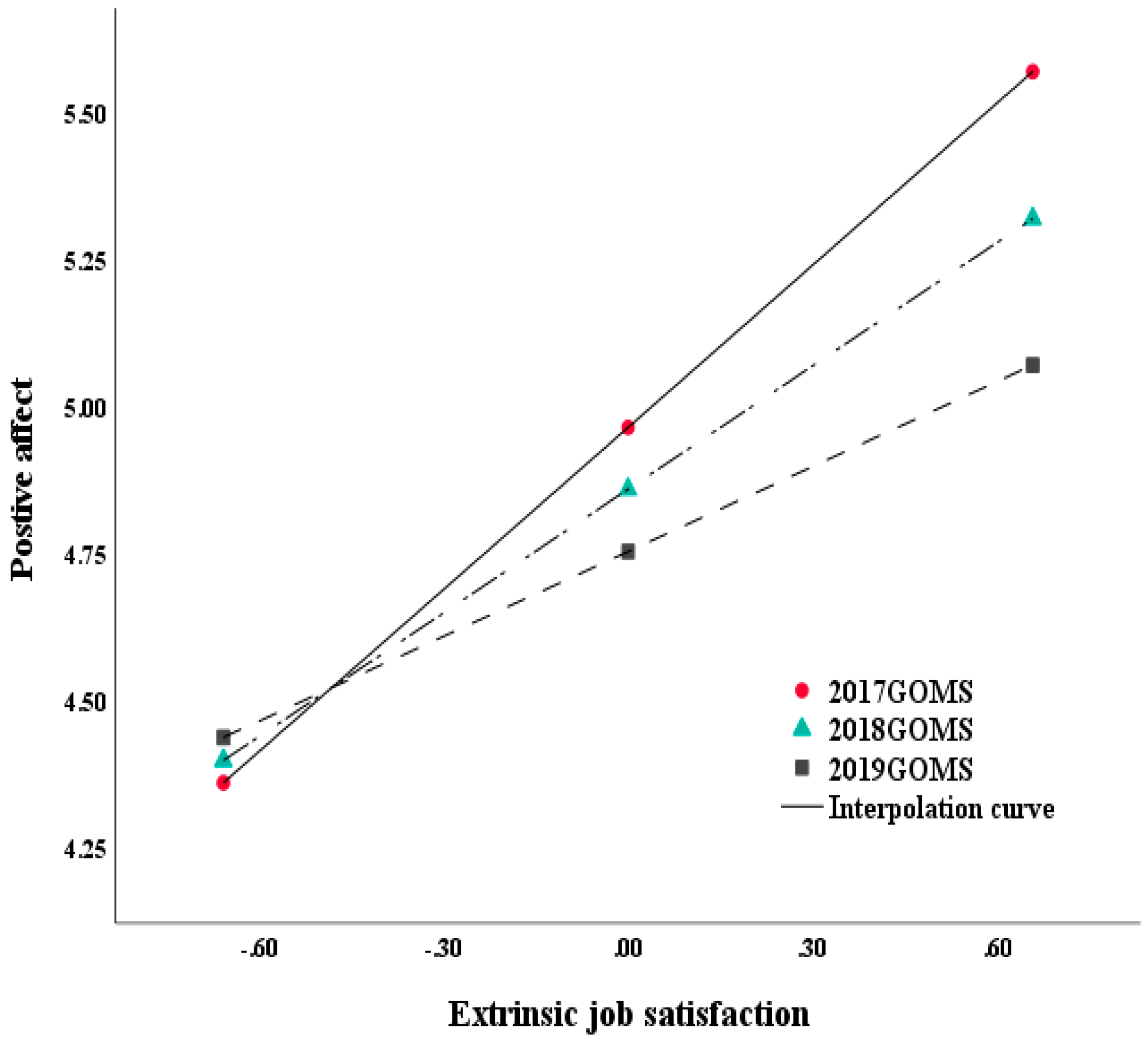

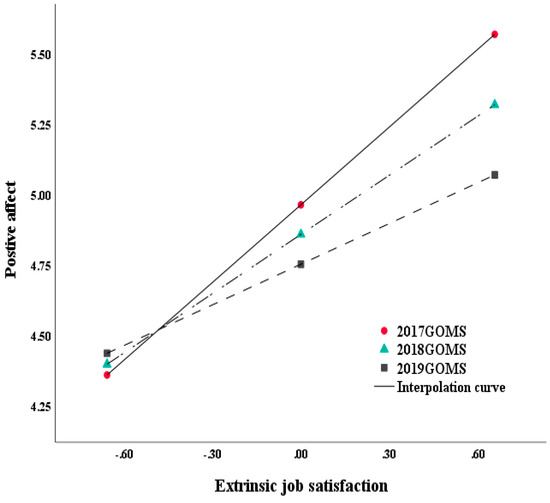

Next, to examine the specific impact of the moderating effect of COVID-19, we tested the significance of the slopes of the two simple regression lines. The results are summarised in Table 9. The effect of EJS on PA was positive for graduates who participated in the 2017, 2018, and 2019 GOMS. Specifically, the effect was highest for graduates who participated in the 2018 GOMS (B = 0.919, p < 0.001) and lowest for those who participated in the 2020 GOMS (B = 0.481, p < 0.001). This indicates that while higher EJS leads to higher PA, the effect of EJS on PA was reduced after the occurrence of COVID-19 compared to that before the pandemic (Figure 2).

Table 9.

Conditional moderating effect of COVID-19 on the relationship between EJS and PA.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes analysis illustrating the moderating effect across three groups.

4.5. The Moderated Mediating Effect of Positive Affect by COVID-19

As previously discussed, PA mediated the relationships between IJS, EJS, and LS (see Table 6 and Table 7). The results of testing the moderated mediating effect of PA by the occurrence of COVID-19 on the relationship between JS and LS are shown in Table 9. First, the significance of the moderated mediation analysis was confirmed through the test of the index of moderated mediation [75]. The index of moderated mediation for the EJS model was –0.145 (Table 9), which did not include 0 within the 95% confidence interval (LLCI = −0.291, ULCI = −0.001), indicating that the moderated mediation effect was significant. However, for the IJS model, the index of moderated mediation was −0.019, which included 0 within the 95% confidence interval (LLCI = −0.165, ULCI = 0.148), indicating that the moderated mediation effect was not significant. Hayes [76] suggested that when the index of moderated mediation is significant, it should be used to examine the point at which the moderated mediation effect is significant. Specifically, the indirect effect of EJS on LS through PA was lower for culinary arts graduates who graduated during the COVID-19 outbreak and participated in the 2020 GOMS (B = 0.260, LLCI = 0.06, ULCI = 0.466) than for those who graduated before the COVID-19 outbreak and participated in the 2018 GOMS (B = 0.497, LLCI = 0.331, ULCI = 0.695) (Table 10).

Table 10.

Conditional indirect effects of JS on LS.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to verify the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between JS and LS among culinary arts graduates and to identify any differences in these effects before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this, we analysed data from 287 respondents who graduated from culinary or confectionery-related departments and participated in the 2018–2020 GOMS. The participants reported being wage workers and were under 35 years old at the time of the survey. The hypotheses were tested using Hayes’ Process Macro Models 4 and 8, and the results are summarised as follows.

First, higher levels of IJS and EJS among culinary arts graduates led to higher levels of PA and LS. This result supports the findings of previous studies [17,36,41], which state that elements of the work environment trigger emotional responses among organisational members.

Second, higher levels of PA among culinary arts graduates led to higher LS. This finding is consistent with those of Moon [34] and Kwon [77], who demonstrated that PA enhances happiness or LS. This suggests that PA is a key factor in increasing LS.

Third, PA partially mediated the relationships between IJS, EJS, and LS. This result is similar to the findings of Kim and Shin [60], Kim et al. [59], and Kang and Jang [54], who found that factors such as PA, work–life balance, and rest mediate the relationship between the work environment and LS. Notably, this study found that the indirect effect of EJS on LS via PA was greater than that of IJS alone.

Finally, the indirect effect of PA on the relationship between EJS and LS decreased after the COVID-19 outbreak. This finding is consistent with those of several studies that have indicated that job insecurity due to the pandemic has increased emotional exhaustion while reducing JS and LS [63,67].

Based on these results, the academic and practical implications of this study are as follows. Academically, based on affective events theory, this study provides a foundation for a clearer understanding of the relationships between JS, PA, and LS. Specifically, it analysed how the extrinsic and intrinsic aspects of JS acted as emotional events that affected individuals’ emotions. This detailed analysis contributes significantly to the development of effective workplace improvement strategies. Moreover, this study enhanced the reliability and generalisability of its findings by using data from culinary arts graduates who graduated before and after the onset of COVID-19, rather than relying on data from a single year.

Additionally, our findings suggest that both IJS and EJS significantly affect PA and LS. Organisations should develop balanced strategies that consider all aspects to enhance employees’ PA and LS. For example, offering competitive salaries, comprehensive benefits, and a safe and pleasant work environment can improve EJS. Moreover, organisations should strive to increase IJS by assigning jobs that match individuals’ aptitudes, providing education and training programmes for personal growth, and giving employees autonomy and responsibility.

Second, this study found that factors such as job nature, autonomy, job-related education and training, and work environment significantly influenced LS through PA. However, the impact of IJS on PA and LS did not differ between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, supporting intrinsic motivation theories related to fundamental human needs. Organisations should ensure that chefs maintain high LS by fostering an environment in which they can exercise autonomy and creativity, provide job-related education and development opportunities, and maintain a safe and hygienic work environment.

Finally, although life returned to normal after the pandemic, the uncertainty surrounding future pandemics has made past experiences significant. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many workers adapted to new work environments, such as remote work or flexible working arrangements. A flexible working system, including shift work based on schedules, time-based work, or part-time options that allow chefs to focus on specific periods, should be formalised as an official human resource management policy instead of fixed working hours. Additionally, it is crucial to continue operating mental health support programmes provided during the pandemic to improve chefs’ mental health and PA. These programmes can help reduce stress and anxiety experienced by chefs, ultimately contributing to higher JS and LS. Therefore, these measures should not be considered temporary but should be established as part of a sustainable HR strategy.

Despite these contributions, this study has several limitations. First, it used data from three years of the GOMS, which does not track the career transitions of culinary arts graduates over time. Future research should use longitudinal designs to better understand career transitions and the causal relationships between PA and LS. Second, this study did not consider additional variables affecting PA and LS, such as moderating factors including remote work, mental health, and organisational support, or antecedent variables influencing JS. Future research should explore these factors to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the subjective well-being of culinary arts graduates. In addition, this study faced limitations regarding the research sample and temporal and spatial constraints, as it focused on Korean culinary arts graduates and analysed the relationships between variables before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, this study considered using a convenience sampling method for surveys to include the post-pandemic period. However, when used alongside the GOMS, which was collected using a stratified sampling method, it was determined that potential biases could arise due to differences in sampling methods. Therefore, future research should explore JS in other industries and regions, and compare the relationships between variables in the post-pandemic period to gain a broader understanding.

6. Conclusions

This study highlighted the mediating role of PA in the relationship between JS and LS among culinary arts graduates, revealing changes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the most significant findings is that the mediating effect of PA on the relationship between JS and LS decreased after the pandemic, suggesting that job insecurity during periods of uncertainty may have exacerbated emotional strain. The results suggest that organisations should create supportive and fulfilling work environments to enhance IJS and EJS. Furthermore, this study emphasises the importance of maintaining PA and LS in the event of another potential virus outbreak.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.-K.N., B.-S.K., and S.H.; methodology, T.-K.N., B.-S.K., and S.H.; validation, T.-K.N., B.-S.K., and S.H.; formal analysis, T.-K.N. and B.-S.K.; resources, B.-S.K. and S.H.; data curation, T.-K.N. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-K.N., B.-S.K., and S.H.; writing—review and editing, T.-K.N., B.-S.K., and S.H.; visualisation, T.-K.N. and B.-S.K.; supervision, T.-K.N.; project administration, T.-K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of the Graduates Occupational Mobility Survey (GOMS) data, which are publicly provided as open data by the Ministry of Employment and Labor of Korea.

Informed Consent Statement

This study utilised public data, which were obtained with informed consent from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available as open data from the Korea Employment Information Service (KEIS) at http://survey.keis.or.kr (accessed on 29 July 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shin, J.R.; Jang, J.H. Analysis of job satisfaction types and verification of influencing factors of the young generation: Focusing on school education experience, organizational climate, and major-job matching. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2023, 42, 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.Y.; Kim, C.W. Subjectivity study of cooking major college student according to cooking practice subject’s untact online class-focusing on using Google Classroom. J. Korea Contents Assocc. 2021, 21, 292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.B. Major factors affecting turnover intention of college graduates: Comparison and analysis according to regular workers. Q. J. Labor. Policy 2019, 19, 93–127. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte Global. Deloitte Global 2024 MZ Generation Survey; Deloitte: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H. Structural relationship among career preparation behavior and, college- and first job satisfaction: Inter-generational comparison by highest level of college graduates’ parental schooling. Korean Educ. Res. J. 2024, 45, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.W.; Lee, J.M. The impact of young cooks’ perceived work environment on self-efficacy and turnover intention. J. Foodserv. Manag. 2024, 27, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.M.; Goh, H.Y. Study of the effect of the working environment on job satisfaction and turnover intention of hotel culinary employee: Focused on 5-star hotels in the Busan area. Foodserv. Ind. J. 2023, 19, 361–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.A.; Lee, I.J. Characteristics of occupational injuries and diseases in South Korea cooking workers. Korean J. Occup. Health 2023, 5, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.Y.; Son, M.A.; Song, R.R. A study on the precarious work experiences of young cooks: Focusing on the meaning of creative labor in apprenticeship employment practices. Korean J. Labor. Studies 2021, 27, 247–397. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J.; Bong, J.H. The effects of person-environment (organization, job, supervisor) fit on the job engagement and job performance: Focusing on moderating effects by F&b and kitchen. FoodService Industry J. 2019, 15, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.C.; Choi, H.J. A research about quality of work-life, affective organizational commitment and turnover intention of y generational chef. Culinary Sci. Hosp. Res. 2017, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.W.; Bae, K.P. Importance of intrinsic job quality in the arts and sports field. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 36, 111–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J. Social intelligence and positive affect mediate the relationship between agreeableness and life satisfaction. Korean J. Psychol: General. 2014, 33, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.R.; Park, I.W. Structural Relationship among ‘university education satisfaction, work satisfaction, and life satisfaction’: Focusing on the moderated effect of college career choice and job preparation program. J. Learn. Cent. Curric. Instr. 2021, 21, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Suñe, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Jiang, F. Structural relationships between workplace friendship, job crafting, positive affect and individualism/collectivism. Korea Bus. Rev. 2022, 37, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Why positive emotions matter in organizations: Lessons from the broaden-and-build model. Psychol. Manag. J. 2000, 4, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, V.M.d.; Teles, J.; Cotrim, T.P. Organizational and individual factors influencing the quality of working life among Brazilian university professors during COVID-19. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.G.; Ahn, T.H. COVID-19 and Life satisfaction: The role of personality traits. Korean J. Econ. Stud. 2023, 71, 75–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Jiang, X.; Chan, W.; Zhou, X. Job satisfaction research in the field of hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2178–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle While you work: A review of the life satisfaction literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.H. A study on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and the change of circumstances on the food service workers’ job satisfaction, job stress, and turnover intension. J. Foodserv. Manag. 2022, 25, 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.H.; Seo, S.H. Effect of millennials’s work value on their first tenure: Serial mediation effect of person-job fit and job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2021, 40, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.A.; Chung, H.W. The effect of in-school work experience on first job satisfaction among college graduates: Applying causal forests. J. Learn. Cent. Curric. Instr. 2024, 24, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Jun, J.S. The moderated mediating effects of career maturity, major-aptitude congruence, and faculty-student interaction on the relationship between college life satisfaction and job satisfaction. Interdisc. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2024, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Cha, J.B. Effects of discrimination experience in the workplace and job satisfaction: Focused on the mediation effect of job search motivation. J. Employ. Career 2022, 12, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.M.N.; Le, D.V.; Hai, Y.V.; Kim, H.D.; Yen, N.N.T. Exploring job satisfaction among Generation Z employees: A study in the SMEs of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 15, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.D. What makes youth entrepreneurs feel satisfied? A study on the factors influencing extrinsic and intrinsic entrepreneurial satisfaction. J. Korean Entrep. Soc. 2020, 15, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.U.; Lee, S.G. The effects on the degree of job fit and first job satisfaction by the college students’ job value Type. J. Career Educ. Res. 2009, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.W.; Oh, S.U.; Lee, J.C. A study on job satisfaction factor analysis. J. Employ. Career 2015, 5, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, E.J.; Lee, H.K. The effects of work value factor and job satisfaction factor on turnover intention of youths. J. Employ. Career 2021, 11, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.B.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, H.K. The effects of college graduates’ first work adjustment: Focusing on comparison between community colleges and 4-year colleges. J. Employ. Career 2022, 12, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.J. The effects of social trust on happiness in adolescents—Mediating effects of positive and negative emotions. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 13, 1889–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y. Structure of positive emotion of college student and office worker in Korea. Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2012, 26, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Oh, S.J. Effects of positive affect and negative affect on the life satisfaction: The role of work self-efficacy and work meaningfulness. J. Korea Soc. Comput. Inform. 2015, 20, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, T.N.; Yoon, Y.L.; Choi, J.H.; Do, B.R. The moderating effects of mobile application usage on the relationship between work stressors and positive affect. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2023, 23, 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satuf, C.; Monteiro, S.; Pereira, H.; Esgalhado, G.; Marina Afonso, R.; Loureiro, M. The protective effect of job satisfaction in health, happiness, well-being and self-esteem. Int. J. Occup. Safety Ergon. 2018, 24, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.S. An analysis for structural relationship among university education satisfaction, work satisfaction, and life satisfaction: Focused on comparison with Department of Tourism and the Major Department of Social Studies. J. Tour. Leisure Res. 2020, 32, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, J.H. A study on the factors influencing life satisfaction of youth with disabilities. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 11, 1461–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S. An analysis of affective factors in the Gyeonggi residents’ subjective quality of life in the perspective of sustainable development. Korean J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 31, 1008111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S. Exploring factors influencing life satisfaction of youth using random forests. J. Industr Converg. 2023, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.R. Effects of job characteristics of hotel cooks on quality of life: Focused on the mediating effects of work-family conflict. J. Converg. Food Spatial Des. 2019, 14, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironi, E. Job Satisfaction as a determinant of employees’ optimal well-being in an instrumental variable approach. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 1721–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Han, H.; Law, R. The price of success: A study on chefs’ subjective well-being, job satisfaction, and human values. Int. J. Hospit Manag. 2018, 69, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.M.; Kim, M.G.; Lee, J.H. The effect of balance between job satisfaction and life satisfaction on subjective well-being: Focusing on generational difference using polynomial regression analysis. Korean J. Bus. Admin 2023, 36, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W. An analysis of research trends on life satisfaction in college students: Focused on domestic studies in counseling field. J. Couns. Educ. Res. 2024, 7, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Busseri, M.A. Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the associations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Diff. 2018, 122, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.J.; Lee, S.B. The effect of positive affect on work volition, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction: Focused on food-service industry employees. Int. J. Tour Hosp. Res. 32 2018, 32, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QiYuan, S.; Rui, Z.; Chengcheng, S. A study on the effect of Chinese office worker learners’ positive emotion, passion, and job crafting on job satisfaction: Focusing on the mediating effect of organizing learning activities of office workers. J. China Stud. 2023, 26, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Tan, S.; Tan, X.; Fan, J. Positive well-being, work-related rumination and work engagement among Chinese university logistics staff. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.W.; Jang, J.Y. The structural relationship among work overload, psychological detachment, work-family conflict and life satisfaction on married workers. Korean J. Couns. 2016, 17, 419–440. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Li, X. Resilience, leadership and work engagement: The mediating role of positive affect. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabati, S.; Ensari, N.; Fiorentino, D. Job satisfaction, rumination, and subjective well-being: A moderated mediational model. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.; Afshari, L. CSR and employee well-being in hospitality industry: A mediation model of job satisfaction and affective commitment. J. Hospit Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, S. The relationship between job satisfaction and depressive symptoms among Chinese adults aged 35–60 years: The mediating role of subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Lee, Y.N.; Sin, W.J. The effect of social workers’ compensation system on life satisfaction: Parallel multiple mediating effects of work-life balance and family support. Korean J. Care Manag. 2024, 50, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Shin, K.L. The effect of self-image congruence of leisure sports participants on positive emotions, meaning of life, and happiness. Cult. Exch. Multicult. Educ. 2024, 13, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.D.; Silva, A.N. da The mental health impacts of a pandemic: A multiaxial conceptual model for COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A.W.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.; Glaeser, E.L.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17656–17666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Nam, J.H.; Kim, S.B. The work and lives of dependent self-employed workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: Focusing on the differences in employment type. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2023, 43, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, W.; Haque, A.; Anis, Z.; Ulfy, M.A. The movement control order (Mco) for COVID-19 crisis and its impact on tourism and hospitality sector in Malaysia. Int. Tour. Hospit J. 2020, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Martos Martínez, Á.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Threat of COVID-19 and emotional state during quarantine: Positive and negative affect as mediators in a cross-sectional study of the Spanish population. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Park, Y.J. A qualitative study on the stress of undergraduate due to COVID-19. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Jung, D.S. A 4 month short-term longitudinal study on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on negative affect, depression, PTSD Symptoms, and suicide ideation. Korean J. Couns. 2022, 23, 105–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J. The dual mediating effect of self-awareness and flourish in the relationship between COVID-19 stress and emotional and behavioral problems of adolescents. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 14, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kamerāde, D.; Bessa, I.; Burchell, B.; Gifford, J.; Green, M.; Rubery, J. The impact of reduced working hours and furlough policies on workers’ mental health at the onset of COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. J. Soc. Policy 2024, 53, 702–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, Y.M.; Alomari, A.; Al-Hamad, A.; Kehyayan, V. The impact of Covid-19 on nurses’ job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health 2024, 11, 1285101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, X.; Pan, J. How nursing students’ risk perception affected their professional commitment during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating effects of negative emotions and moderating effects of psychological capital. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.N.; Oh, S.I. Analysis of job satisfaction among young adult graduates with arts majors. J. Korea Cult. Ind. 2023, 23, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Chung, D.H. The effect of job value and job-major match on job satisfaction of sports studies undergraduates. J. Korean Soc. Wellness 2021, 16, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.S. An analysis on the effect on the happiness of college graduate worker: Focusing on occupational values and job satisfaction. J. Learn. Cent. Curric. Instr. 2020, 20, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H. Relationships among high school teachers’ positive emotions, negative emotions, grit, stress, and life satisfaction. Korean J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 34, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).