Factors Impacting Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Electric Vehicles in China: Based on the Integration of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Compared with previous studies from the rational perspective and individual cost-benefit assessment, the uniqueness of this research is that it views consumers’ intention to purchase EVs as a result of the combined effect of individual altruistic and self-interested psychological factors. In other words, the paper attempts to construct a research model to predict Chinese consumers’ intention to purchase EVs by integrating TPB and NAM, which not only compromises the rational and altruistic perspectives but also provides a more comprehensive interpretation of Chinese consumers’ intention to purchase EVs.

- Compared with the existing studies integrating TPB and NAM, this paper further discusses the possible correlation between the two theoretical variables, i.e., it analyses the relationship between awareness of consequences and attitudes, subjective norms and personal norms. Therefore, we can provide ideas for subsequent studies in other areas analysing the adoption of EVs and the field of low-carbon consumption.

- Currently, the Chinese government mainly adopts financial incentives to promote the promotion of EVs, and policies mainly focus on individual self-interested factors. However, with the development of EVs industry, it is worth exploring whether there is a need to formulate policies related to altruistic factors. Thus, in our study, the role of self-interested and altruistic factors on individuals’ intention to purchase EVs is considered, and the conclusions can be used as a reference for policymakers.

2. Literature Review

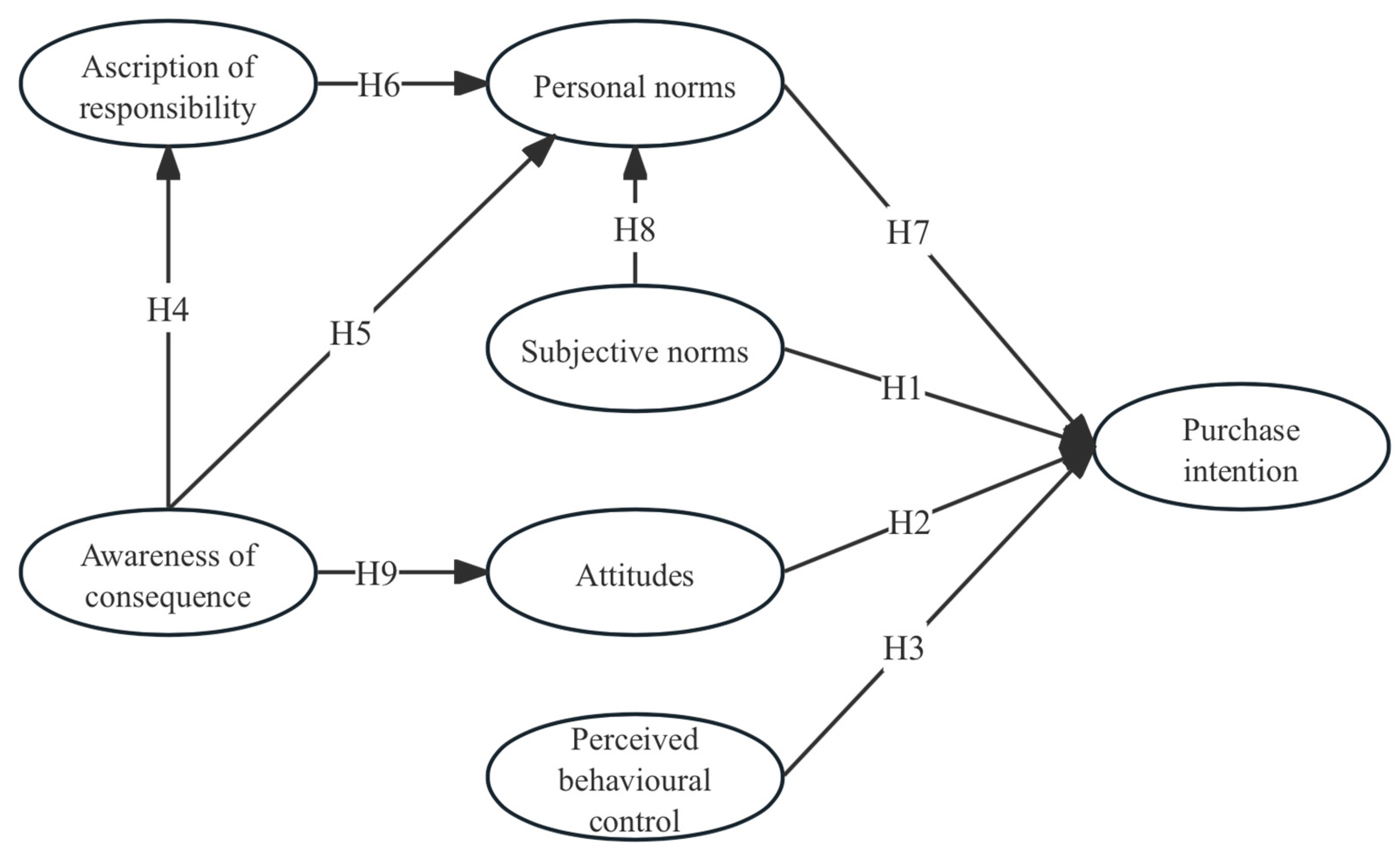

3. Research Hypothesis Development

3.1. TPB and the Relationship Among Its Variables

3.2. NAM and the Relationship Among Its Variables

3.3. The Relationship between TPB and the NAM

4. Research Methods

4.1. Measurement Development

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.3.1. Common Method Bias

4.3.2. Reliability and Validity

5. Results

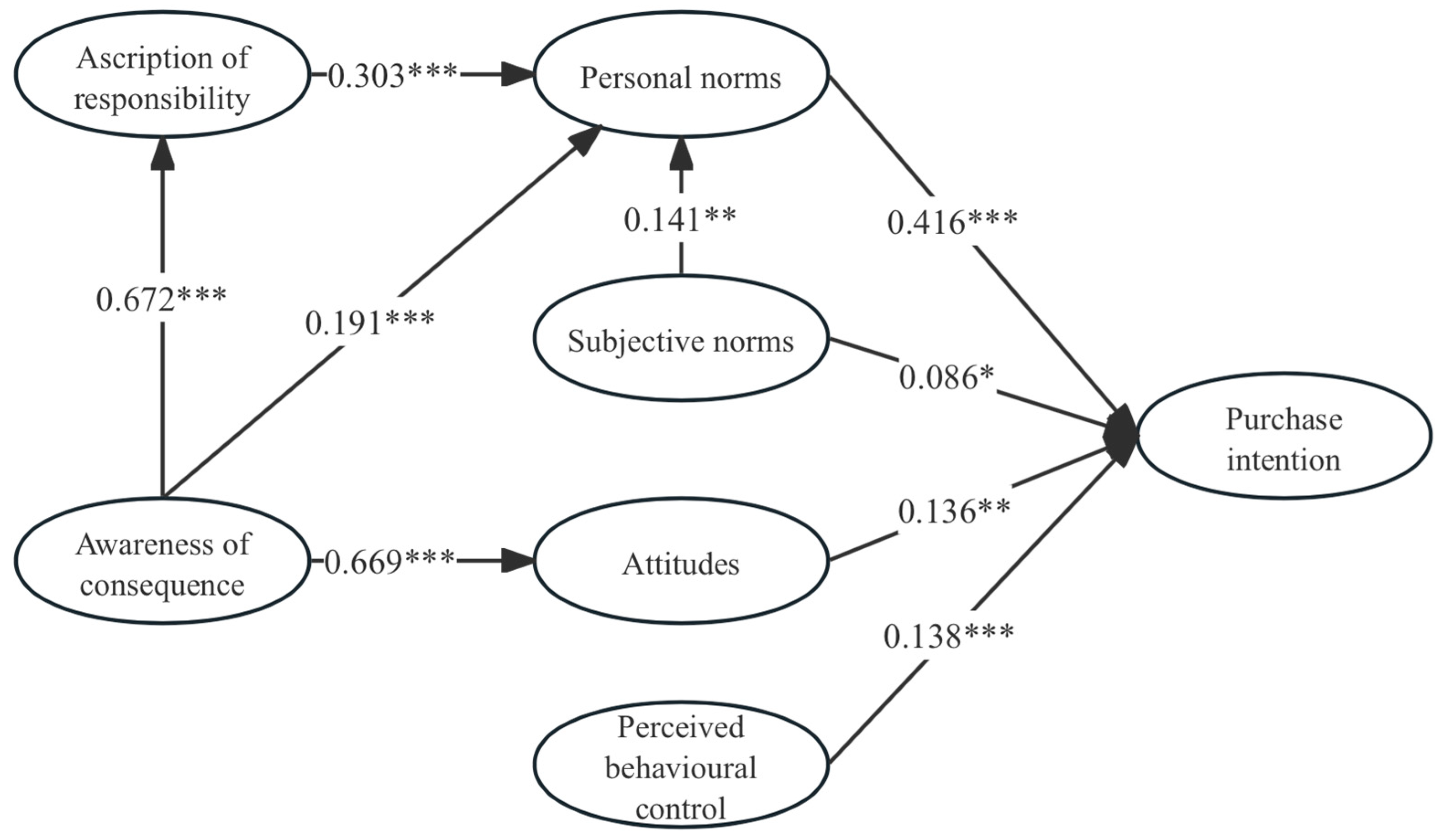

5.1. Hypotheses Testing Results

5.2. Results of the Mediation Effects Test

6. Discussion

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

- Personal norms, perceived behavioural control, attitudes and subjective norms had a significant positive effect on consumers’ EVs purchase intention, with personal norms playing the largest role. It indicates that altruistic factors played a crucial role in motivating consumers’ EV purchase intention. Meanwhile, awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility and subjective norms were positive predictors of persona norms.

- Awareness of consequence, ascription of responsibility and subjective norms had indirect effects on EVs purchase intention, where the indirect effect of awareness of consequence was realised through the mediating paths of ascription of responsibility, personal norms and attitudes; both ascription of responsibility and subjective norms had an indirect effect on EV purchase intention through personal norms.

- Between TPB and the NAM, subjective norms could stimulate consumers’ personal norms, and awareness of consequence could significantly increase Chinese consumers’ positive attitudes towards EVs.

- The results of this study confirmed that subjective norms could stimulate Chinese consumers’ intention to purchase EVs, clarifying the relationship between subjective norms and purchase intention. The reason for the discrepancy between this finding and existing studies may be that cultural background affects the formation of individual subjective norms. Therefore, subsequent research on EVs adoption should consider the cultural background of consumers.

7.2. Practical Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors (Years) | Study Focus | Theory | Sample and Areas | Methods | Major Findings | |

| Factors with sig. Direct and Indirect Effect | Factors with No sig. Effect | |||||

| Shanmugavel and Balakrishnan (2023) [23] | The study examined the influence of pro-environmental behaviour towards behavioural intention of EVs. | TPB | - 400 - India | SEM | - Environmental responsibility, environmental knowledge, environmental concern → Behavioural intention - Personal norm → Environmental responsibility → Behavioural intention - Personal norm, subjective norm → Environmental concern → Behavioural intention - Personal norm, subjective norm, descriptive norm → Environmental knowledge → Behavioural intention | - Descriptive norm, subjective norm → Behavioural intention |

| Upadhyay and Kamble (2023) [29] | The study was based on the perspective of the stimulus–organism–response to research Indian consumers’ pro-environment purchase intention of EVs. | SOR | - 1143 - India | PLS-SEM | - Pro-environment attitude → Pro-environment purchase intention - Pro-environment responsibility → Pro-environment attitude, pro-environment value - Pro-environment value → Pro-environment attitude, pro-environment purchase intention - Pro-environment value → Pro-environment attitude → Pro-environment purchase intention | |

| Sun, Sylvia and He (2022) [16] | The paper examined people’s EV purchase intention in Hong Kong, an Asian compact city, and how the influential factors are different from Denmark. | TPB | - 982 - Hongkong | - SEM - Multi-group analysis | - Attitude, subjective norms, perceived difficulties, personal norms, perceived certainty, environmental concern → EV buying intention - Subjective norms → personal norms → EV buying intention - Environmental concern → personal norms → EV buying intention | |

| Vafaei-Zadeh, Wong and Hanifah (2022) [24] | The study used the combined TPB and TAM with additional variables to examine EV purchase intention among Generation Y consumers in Malaysia. | - TAM - TPB | - 213 - Malaysia | SEM | - Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use → Attitude - Subjective norms, attitude, perceived behavioural control, price value, perceived risk, environmental self-image → Purchase intention | - Perceived usefulness→ Purchase Intention - Price value → Attitude - Infrastructure barrier→ Purchase intention |

| Ackaah, Kanton and Osei (2022) [25] | The paper explored the factors that influence consumers’ purchase intention of EVs in Ghana, applying the extended TPB. | TPB | - 404 - Ghana | SEM | - Consumer knowledge, environmental concern → Attitudes - Government Policy → Perceived Behavioural Control - Attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control → Purchase intentions | - Government policy, environmental concern, consumer knowledge, personal moral norm → Purchase intentions |

| Asadi et al. (2021) [1] | Based on the perspective of pro-environmental behaviour, the study used TPB and NAM to build a research model to analyse the influence factors of consumers’ purchase intention on EV. | - TPB - NAM | - 177 - Malaysia | PLS-SEM | - Personal norms, perceived consumer effectiveness, perceived value, attitude, subjective norm → Intentions - Awareness of consequences, Ascription of responsibility, Perceived consumer effectiveness→ Personal norms - Awareness of consequences → Ascription of responsibility - Perceived value → Attitude | - Perceived behavioural control → Intentions - Financial incentive policies → Intentions |

| Jaiswal, Kaushal and Kant (2021) [22] | The study aimed to test the extended TAM with perceived risk and financial incentives policy to understand and predict consumers’ intention to adopt EVs in India. | TAM | - 418 - Indian | SEM | - Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use → Attitude - Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived risk, attitude → Intention - Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived risk → Attitude → Intention | - Perceived risk → Attitude |

| Liu et al. (2021) [30] | The paper explored the impact of status symbol, environmentalism symbol and innovation symbol on consumer intention to adopt BEV. | Self-consistency theory | - 347 - China | SEM | - Status symbol, environmentalism symbol, innovation symbol → Adoption intention - Environmentalism symbol → Adoption intention with the moderation of environmentalist self-identity - Innovation symbol → Adoption intention with the moderation of innovator self-identity - Innovation symbol → Adoption intention with the moderation of face consciousness | Face consciousness did not moderate the relationship between status (environmentalism) symbol and adoption intention of EVs. |

| Zhang, Bai and Shang (2018) [26] | The study analysed consumers’ perceptions and motivation towards EVs purchase intention using TPB. | TPB | - 264 - China | SEM | - Perceive economic benefits, perceive environmental benefits, perceive risks → Attitudes - Attitudes → Subjective norm - Attitudes, subjective norm, perceived purchase behavioural control → Purchase intention | |

| He and Zhan (2018) [28] | Based on the perspective of pro-environmental behaviour, the paper proposed an extended norm activation model to investigate the influence of consumers’ altruism on the adoption of EVs. | NAM | - 396 - China | SEM | - Awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, perceived consumer effectiveness → Personal norms - Awareness of consequences → Ascription of responsibility - Perceived consumer effectiveness → Intention - Personal norms → Intention with moderation of external costs | |

References

- Asadi, S.; Nilashi, M.; Samad, S.; Abdullah, R.; Mahmoud, M.; Alkinani, M.H.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Factors impacting consumers’ intention toward adoption of electric vehicles in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124474. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, J.; Nie, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Exploring pathway to achieving carbon neutrality in China under uncertainty. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 185, 109689. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, C.; Nie, H. An Overview of China’s energy labeling policy portfolio: China’s contribution to addressing the global goal of sustainable development. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). CO2 Emissions in 2022; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, R.; Li, B.H.; Li, M.; Mo, R.Q.; Fang, S.Y. Heterogeneous Impact of Public Charging Infrastructure on Electric Vehicle Purchases. J. Technol. Econ. 2023, 42, 143–154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Cheng, P. Predicting consumers’ adoption of electric vehicles during the city smog crisis: An application of the protective action decision model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yao, J.; Bai, B.; Ma, X. Exploring consumer preferences for electric vehicles based on the random coefficient logit mode. Energy 2023, 263, 125504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, S. Understanding the impact of reoccurring and non-financial incentives on plug-in electric vehicle adoption—A review. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 119, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.R.; Jiang, H.Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S. Regional disparities and influencing factors of average CO2 emissions from transportation industry in Yangtze River Economic Belt. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 57, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Kuai, L.Y. Driving factors and peaking path of CO2 emissions for China’s transportation sector. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Notice from the General Office of the State Council Regarding the Issuance of the Development Plan for the New Energy Automobile Industry (2021–2035). 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-11/02/content_5556716.htm (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Chen, K.; Gu, R.; Hu, J. Research on Consumer Purchase Intention of New Energy Vehiclesunder the Benefit-risk Asesment Framework. J. Nanjing Technol. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 18, 61–70, 112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.D.; Luo, R.Q.; Gu, Y.F. Government’s Promotion Policies and the Demand of New-Energy Vehicles: Evidence from Shanghai. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 04, 42–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xu, J.; Fan, Y. Willingness to pay and preferences for alternative incentives to EV purchase subsidies: An empirical study in China. Energy Econ. 2019, 81, 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- She, Z.Y.; Qing, S.; Ma, J.J.; Xie, B.C. What are the barriers to widespread adoption of battery electric vehicles? A survey of public perception in Tianjin, China. Transp. Policy 2017, 56, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.K.; Sylvia, Y.; He, J.T. The purchase intention of electric vehicles in Hong Kong, a high-density Asian context, and main differences from a Nordic context. Transp. Policy 2022, 128, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Zhang, X.J. Factors affecting urban residents’ participation in environmental governance: An empirical analysis based on TPB and NAM. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2017, 18, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, H. Guests’ pro-environmental decision-making process: Broadening the norm activation framework in a lodging context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 47, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liao, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, T. The role of environmental concern in the public acceptance of autonomous electric vehicles: A survey from China. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kaushal, V.; Kant, R.; Singh, P.K. Consumer adoption intention for electric vehicles: Insights and evidence from Indian sustainable transportation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, N.; Balakrishnan, J. Influence of pro-environmental behaviour towards behavioural intention of electric vehicles. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 187, 122206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Wong, T.K.; Hanifah, H.; Teoh, A.P.; Nawaser, K. Modelling electric vehicle purchase intention among generation Y consumers in Malaysia. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackaah, W.; Kanton, A.T.; Osei, K.K. Factors influencing consumers’ intentions to purchase electric vehicles in Ghana. Transp. Lett. 2022, 14, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Shang, J. Is subsidized electric vehicles adoption sustainable: Consumers’ perceptions and motivation toward incentive policies, environmental benefits, and risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N.; Kamble, A. Examining Indian consumer pro-environment purchase intention of electric vehicles: Perspective of stimulus-organism-response. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 189, 122344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, D.; Mou, Y.; Liu, M. The relationship between symbolic meanings and adoption intention of electric vehicles in China: The moderating effects of consumer self-identity and face consciousness. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.A.; De Groot, J.I.M.; Molin, E.J.E.; Wee, B. Intention to act towards a local hydrogen refueling facility: Moral considerations versus self-interest. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 48, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.F.; Musa, G. An examination of recreational divers’ underwater behaviour by attitude- behaviour theories. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Geng, G.; Ping, S. Determinants and implications of citizens’ environmental complaint in China: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Qu, M.; Zhang, D.H.; Zhang, Y.X. Research on the farmers’ behavior of domestic waste source sorting—Based on TPB and NAM integration framework. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 75–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding consumer recycling behavior: Combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D. Predicting household PM2. 5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: An integrative model of Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.H.; Nguyen, P.M. Integrating the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model to investigate organic food purchase intention: Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yao, J. Drivers of residents’ water saving behavior: An expanded TPB-NAM based integration framework analysi. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 32–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, H.; Mundorf, N.; Redding, C.; Ye, Y. Integrating Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Sustainable Transport Behavior: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K. Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: Using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Gong, S.; Xie, F. Theoretical Basis and Empirical Test of the Formation of Chinese Consumers’ Green Purchasing Intention. Jilin Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 59, 140–151, 222. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, N. The influences of incentive policy perceptions and consumer social attributes on battery electric vehicle purchase intentions. Energy Policy 2021, 151, 112163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shao, J. Research on Influencing Factors of Consumers’ Environmentally Friendly Clothing Purchase Behavior. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C. Research on the Impact of Haze Pollution on the Purchase Intention and Behavior of Urban Residents’ Energy-Saving Appliances. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou City, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biel, A.; Thøgersen, J. Activation of social norms in social dilemmas: A review of the evidence and reflections on the implications for environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2007, 28, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Du, Y.W.; Wan, X.L. On the pro-environment willingness of marine fishery enterprises based on TPB-NAM integration. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 75–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.S.; Lu, H.N.; Hong, S. Research on affecting factors of energy saving behavior based on norm activation model. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2016, 30, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Tanwir, N.S. Do pro-environmental factors lead to purchase intention of hybrid vehicles? The moderating effects of environmental knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniederjans, D.G.; Starkey, C.M. Intention and willingness to pay for green freight transportation: An empirical examination. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 31, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, J. Electric vehicle development in Beijing: An analysis of consumer purchase intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Bi, W.W. Impact of Waste Separation and Recycling Efforts on Green Purchase Intentions. Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 49–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.G.; Duan, S.L. Impact of Environmental Responsibility on Consumers’ Green Purchasing Behavior: On Chained Multiple Mediating Effect of Green Self-efficacy and Green Perceived Value. J. Nanjing Technol. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 21, 48–60, 115–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Year 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2022/indexch.htm (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Teisl, M.F.; Noblet, C.L.; Rubin, J. The psychology of eco-consumption. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2009, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.B.; Li, D.J.; Wu, B.; Li, Y.N. The Relationship between Atmospheric Cues and Perceived Interactivity on the Online Shopping Websites. Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Choy-Har, W.; Tan, G.W.; Teck-Soon, H.; Keng-Boon, O. Can mobile TV be a new revolution in the television industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 764–776. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, M.S.; MacKinnon, D.P. Required Sample Size to Detect the Mediated Effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Green, R.T. Cross-cultural examination of the Fishbein behavioral intentions model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1991, 22, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Vasseur, V.; Fan, Y.; Xu, J. Exploring reasons behind careful-use, energy-saving behaviours in residential sector based on the theory of planned behaviour: Evidence from Changchun, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancha, R.M.; Yoder, C.Y. Cultural antecedents of green behavioral intent: An environmental theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.H.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.H.; Long, R.Y.; Xu, Z.N.; Cao, Q.R. Factors affecting low-carbon consumption behavior of urban residents: A comprehensive review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- López-Mosquera, N.; García, T.; Barrena, R. An extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior to predict willingness to pay for the conservation of an urban park. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Code | Items |

|---|---|---|

| SN | SN1 | News media publicity can influence my decision to purchase EVs. |

| SN2 | Encouragement from friends around me will increase my intention to purchase EVs. | |

| SN3 | The outcry will make me consider buying EVs to reduce environmental pollution. | |

| ATT | ATT1 | I think buying EVs will be better for the environment. |

| ATT2 | I support more state policies to encourage individuals to purchase EVs. | |

| PBC | PBC1 | If I wanted to buy an EV, I could afford its current price. |

| PBC2 | When I decide to use EVs, I can afford to do so, even if the maintenance costs may be slightly higher. | |

| PBC3 | I have the time and access to information about EVs. | |

| AC | AC1 | I think buying fuel vehicles accelerates global warming. |

| AC2 | I think buying fuel vehicles accelerates the shortage of resources. | |

| AC3 | I think buying fuel vehicles pollutes the environment. | |

| AR | AR1 | We are responsible for the adverse health effects of fuelled vehicles’ exhaust. |

| AR2 | We are responsible for the environmental degradation caused by the use of fuel vehicles. | |

| AR3 | We are responsible for the GHG produced by the use of fuel vehicles. | |

| PN | PN1 | It is my responsibility to do my part to protect the environment and conserve resources. |

| PN2 | I will take the initiative to learn about environmental protection. | |

| PN3 | Although my own influence is small, I want to contribute to environmental protection. | |

| PN4 | We should all realise the need to protect the environment; otherwise, our future generations will suffer the consequences. | |

| PI | PI1 | When I need to purchase vehicles, I prefer EVs. |

| PI2 | When I need to replace my vehicle, I prefer to buy an EV. | |

| PI3 | EVs are my first choice for future vehicle purchases. |

| Variables | Code | Loading 1 | Loading 2 | Loading 3 | Loading 4 | Loading 5 | Loading 6 | Loading 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.766 | ||||||

| ATT2 | 0.766 | |||||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.653 | ||||||

| SN2 | 0.773 | |||||||

| SN3 | 0.764 | |||||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.734 | ||||||

| PBC2 | 0.774 | |||||||

| PBC3 | 0.617 | |||||||

| AC | AC1 | 0.649 | ||||||

| AC2 | 0.694 | |||||||

| AC3 | 0.791 | |||||||

| AR | AR1 | 0.679 | ||||||

| AR2 | 0.797 | |||||||

| AR3 | 0.756 | |||||||

| PN | PN1 | 0.708 | ||||||

| PN2 | 0.824 | |||||||

| PN3 | 0.832 | |||||||

| PN4 | 0.707 | |||||||

| PI | PI1 | 0.796 | ||||||

| PI2 | 0.765 | |||||||

| PI3 | 0.776 |

| Demographic Variable | Items | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 445 | 51.33% |

| Female | 422 | 48.67% | |

| Age | 18–20 | 33 | 3.81% |

| 21–35 | 409 | 47.17% | |

| 36–50 | 310 | 35.76% | |

| 51–65 | 110 | 12.69% | |

| >65 | 5 | 0.57% | |

| Education Level | High school or below | 84 | 9.69% |

| Associate degree | 68 | 7.84% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 268 | 30.91% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 447 | 51.56% | |

| Total household income for the previous year (RMB) | ≤30,000 | 54 | 6.23% |

| 30,000–100,000 | 256 | 29.53% | |

| 100,000–250,000 | 331 | 38.18% | |

| 250,000–500,000 | 160 | 18.45% | |

| >500,000 | 66 | 7.61% |

| Latent Variables | Items | Loading | Cronbach’ s α | CR | KMO | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.830 | 0.810 | 0.811 | 0.500 | 0.682 |

| ATT2 | 0.822 | |||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.775 | 0.739 | 0.750 | 0.650 | 0.507 |

| PBC2 | 0.794 | |||||

| PBC3 | 0.537 | |||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.790 | 0.844 | 0.844 | 0.729 | 0.644 |

| SN2 | 0.799 | |||||

| SN3 | 0.818 | |||||

| AC | AC1 | 0.874 | 0.927 | 0.928 | 0.758 | 0.811 |

| AC2 | 0.894 | |||||

| AC3 | 0.933 | |||||

| AR | AR1 | 0.670 | 0.835 | 0.845 | 0.675 | 0.647 |

| AR2 | 0.879 | |||||

| AR3 | 0.849 | |||||

| PN | PN1 | 0.716 | 0.883 | 0.888 | 0.796 | 0.668 |

| PN2 | 0.891 | |||||

| PN3 | 0.914 | |||||

| PN4 | 0.729 | |||||

| PI | PI1 | 0.857 | 0.912 | 0.887 | 0.759 | 0.724 |

| PI2 | 0.849 | |||||

| PI3 | 0.847 |

| Mean | ATT | PBC | SN | AC | AR | PN | PI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 3.893 | 0.826 | ||||||

| PBC | 3.421 | 0.395 *** | 0.712 | |||||

| SN | 4.399 | 0.484 *** | 0.308 *** | 0.802 | ||||

| AC | 4.011 | 0.637 *** | 0.295 *** | 0.687 *** | 0.901 | |||

| AR | 4.012 | 0.748 *** | 0.379 *** | 0.553 *** | 0.645 *** | 0.805 | ||

| PN | 3.234 | 0.627 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.431 *** | 0.468 *** | 0.513 *** | 0.817 | |

| PI | 3.019 | 0.476 *** | 0.361 *** | 0.373 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.347 *** | 0.565 *** | 0.851 |

| Fit Index | Goodness-of-Fit Index | Evaluation Criteria | Values | Evaluation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit index | χ2/df | <3, good fit; <5, reasonable fit | 2.951 | good fit |

| GFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.945 | good fit | |

| RMSEA | <0.05, good fit; <0.08, reasonable fit | 0.047 | good fit | |

| Relative fit index | NFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.958 | good fit |

| TLI | >0.9, good fit | 0.965 | good fit | |

| CFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.972 | good fit | |

| IFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.972 | good fit |

| Fit Index | Goodness-of-Fit Index | Evaluation Criteria | Values | Evaluation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit index | χ2/df | <3, good fit; <5, reasonable fit | 4.734 | reasonable fit |

| GFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.913 | good fit | |

| RMSEA | <0.05, good fit; <0.08, reasonable fit | 0.066 | reasonable fit | |

| Relative fit index | NFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.930 | good fit |

| TLI | >0.9, good fit | 0.933 | good fit | |

| CFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.943 | good fit | |

| IFI | >0.9, good fit | 0.944 | good fit |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SN | → | PI | 0.086 | 0.057 | 2.08 | * | Supported |

| H2 | ATT | → | PI | 0.136 | 0.045 | 2.997 | ** | Supported |

| H3 | PBC | → | PI | 0.138 | 0.04 | 3.533 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | AC | → | AR | 0.672 | 0.04 | 18.707 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | AC | → | PN | 0.191 | 0.066 | 3.298 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | AR | → | PN | 0.303 | 0.05 | 6.311 | *** | Supported |

| H7 | PN | → | PI | 0.416 | 0.039 | 9.93 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | SN | → | PN | 0.141 | 0.076 | 2.745 | ** | Supported |

| H9 | AC | → | ATT | 0.669 | 0.04 | 17.822 | *** | Supported |

| Path | Point Estimates | SE | Bias-Corrected 95%CI | Percentile 95%CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p | Lower | Upper | p | |||

| AC → AR → PN | 0.203 *** | 0.044 | 0.123 | 0.292 | 0 | 0.122 | 0.291 | 0 |

| AC → PN → PI | 0.080 * | 0.032 | 0.019 | 0.144 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.142 | 0.017 |

| AC → AR → PN → PI | 0.085 *** | 0.021 | 0.05 | 0.132 | 0 | 0.048 | 0.13 | 0 |

| AC → ATT → PI | 0.091 * | 0.035 | 0.024 | 0.162 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.159 | 0.015 |

| SN → PN → PI | 0.059 ** | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.113 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.109 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, Z.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, J. Factors Impacting Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Electric Vehicles in China: Based on the Integration of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209092

Ji Z, Jiang H, Zhu J. Factors Impacting Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Electric Vehicles in China: Based on the Integration of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):9092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209092

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Zhongyang, Hao Jiang, and Jingyi Zhu. 2024. "Factors Impacting Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Electric Vehicles in China: Based on the Integration of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 9092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209092

APA StyleJi, Z., Jiang, H., & Zhu, J. (2024). Factors Impacting Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Electric Vehicles in China: Based on the Integration of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model. Sustainability, 16(20), 9092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209092