The Importance of Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Maternal Nutrition Knowledge and Undernutrition Among Children Under Five

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

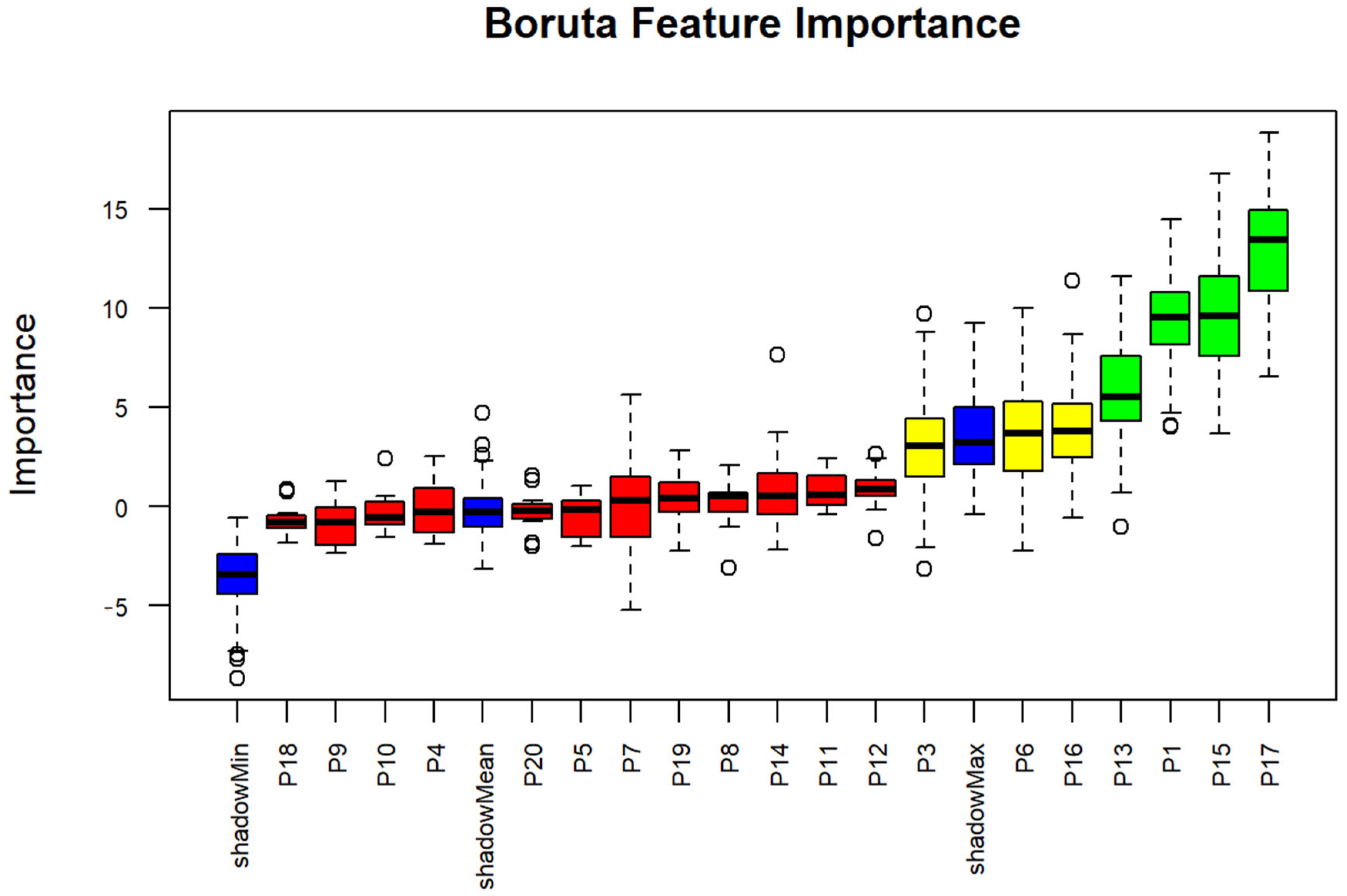

3.2. The Important Factors for MNK

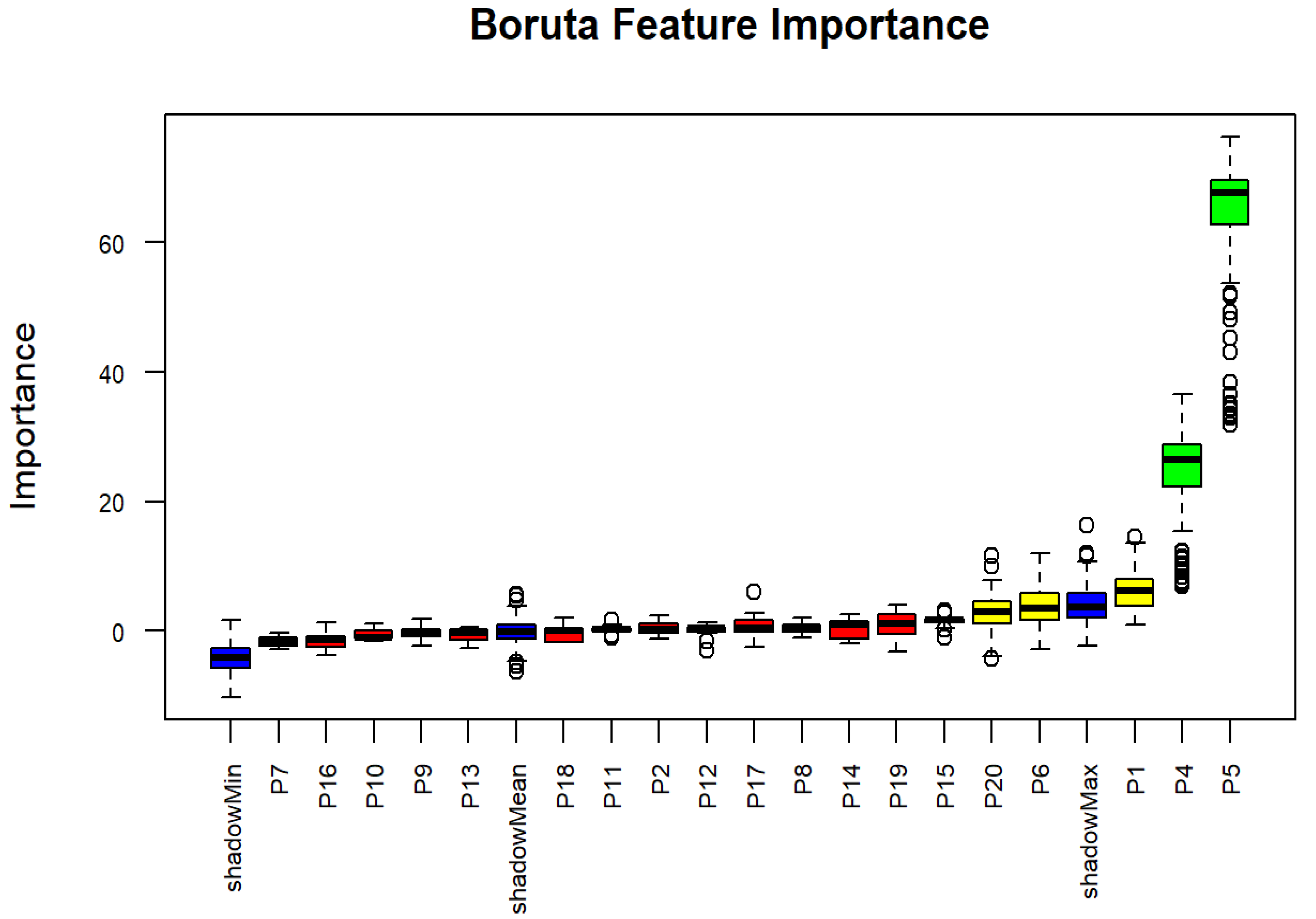

3.3. The Importance Factors for Stunting

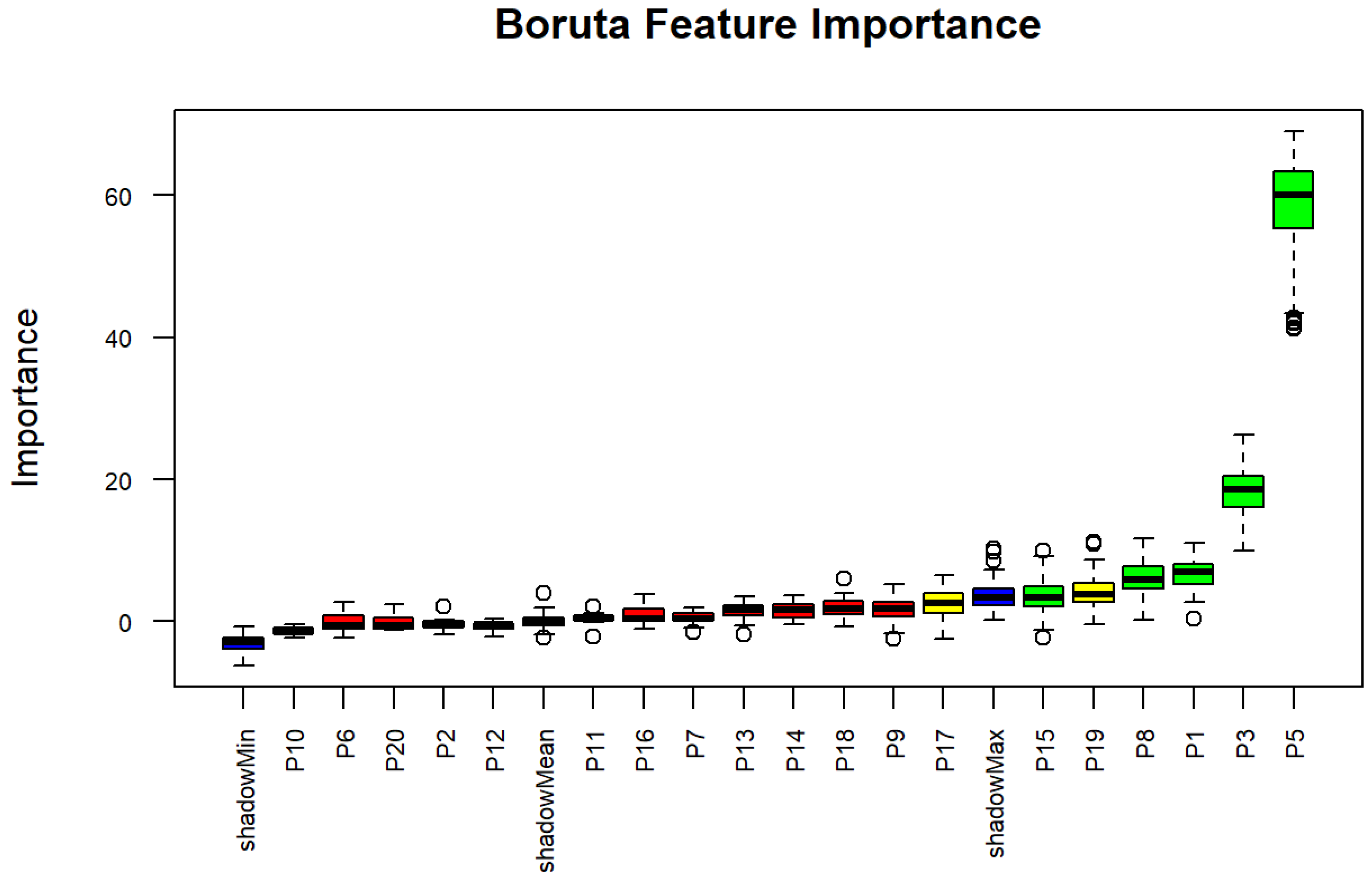

3.4. The Importance Factors for Wasting

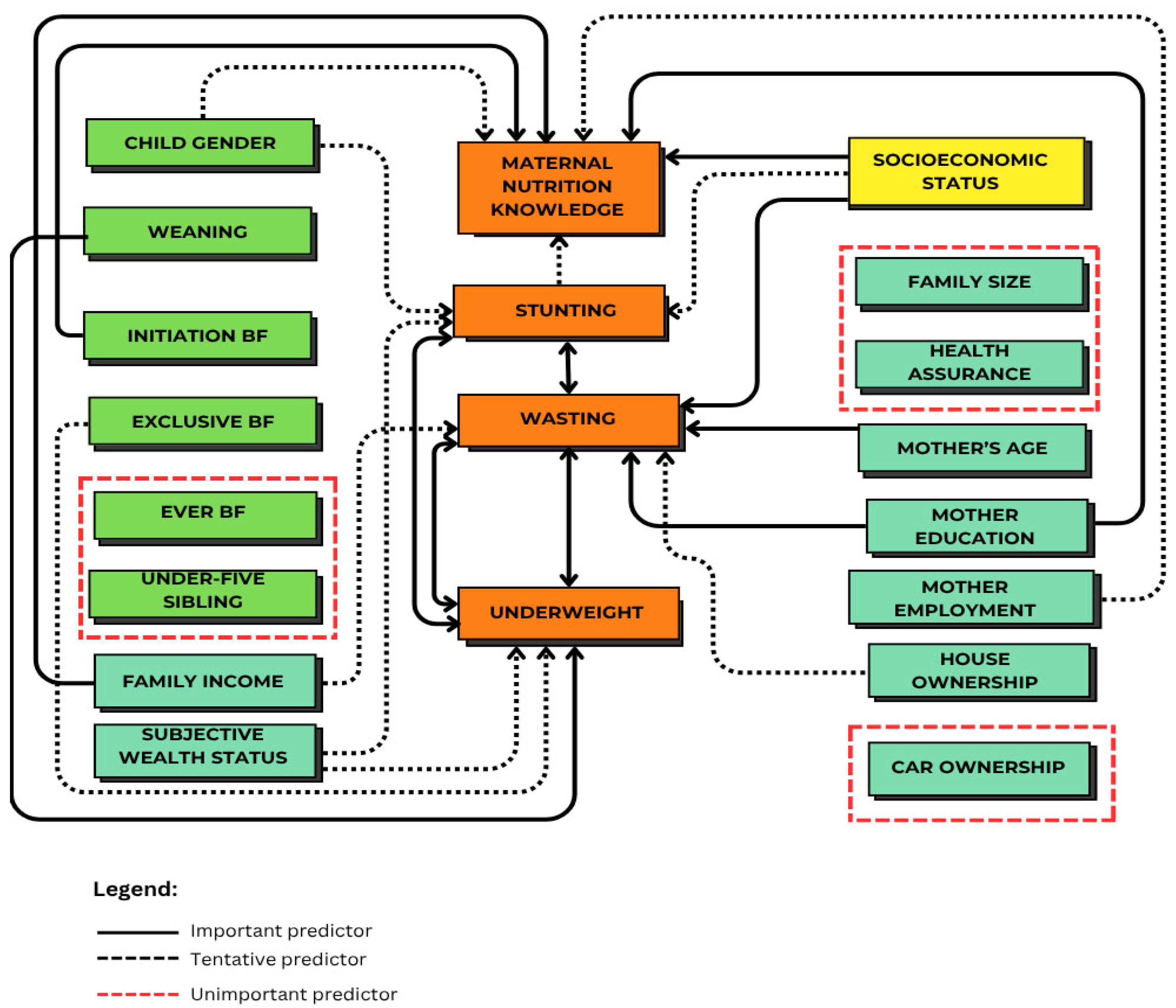

3.5. The Importance Factors for Underweight

4. Discussion

4.1. SES and MNK

4.2. SES and Child Undernutrition

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MNK | Maternal nutrition knowledge |

| CSDH | Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Factors of Health |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| WebApps | Web applications |

| APK | Android Package Kit |

| BF | Breastfeeding |

| WHZ | Weight-for-height Z score |

| HAZ | Height-for-age Z score |

| WAZ | Weight-for-age Z score |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| IYCF | Infant and young child feeding |

| GNKQ-R | General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire—Revised |

References

- UNICEF; WHO; World Bank. Level and Trend in Child Malnutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 4. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073791 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Rahut, D.B.; Mishra, R.; Bera, S. Geospatial and environmental determinants of stunting, wasting, and underweight: Empirical evidence from rural South and Southeast Asia. Nutrition 2024, 120, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf-Manasseh, Z.; Oot, L.; Sethuraman, K. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project Giving Children the Best Start in Life: Integrating Nutrition and Early Childhood Development Programming Within the First 1000 Days. 2016. Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Nutrition-Early-Childhood-Development-Technical-Brief-Jan2016.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- WHO; UNICEF. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. 2009. p. 11. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44129/1/9789241598163_eng.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Briend, A.; Khara, T.; Dolan, C. Wasting and stunting—Similarities and differences: Policy and programmatic implications. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36 (Suppl. S1), S15–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underweight Among Children Under 5 Years of Age (Number in Thousands) (Model-Based Estimates). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/gho-jme-underweight-numbers-(in-millions) (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 525026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, T.R.P. Stunting in Indonesia: Understanding the Roots of the Problem and Solutions. July 2023. Available online: https://berkas.dpr.go.id/pusaka/files/info_singkat/Info%20Singkat-XV-14-II-P3DI-Juli-2023-196-EN.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Patel, A.B.; Kuhite, P.N.; Alam, A.; Pusdekar, Y.; Puranik, A.; Khan, S.S.; Kelly, P.; Muthayya, S.; Laba, T.; Almeida, M.D.; et al. M-SAKHI—Mobile health solutions to help community providers promote maternal and infant nutrition and health using a community-based cluster randomized controlled trial in rural India: A study protocol. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, S.K.; Hossain, B.; Arora, A. Maternal nutrition counselling is associated with reduced stunting prevalence and improved feeding practices in early childhood: A post-program comparison study. Nutr. J. 2019, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, A.; Shagti, I.; Boro, R.A.M.; Adi, A.M.; Saleh, A.; Sanjiwany, P.A. The Effect of Family-Based Nutrition Education on the Intention of Changes in Knowledge, Attitude, Behavior of Pregnant Women and Mothers with Toddlers in Preventing Stunting in Puskesmas Batakte, Kupang Regency, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia Working Area. People 2020, 14, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Black, M.M.; Delichatsios, H.K.; Story, M.T. (Eds.) Nutrition Education: Strategies for Improving Nutrition and Healthy Eating in Individuals and Communities; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.B.; Permatasari, P.; Susanti, H.D. The effect of mothers’ nutritional education and knowledge on children’s nutritional status: A systematic review. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2023, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demilew, Y.M.; Alene, G.D.; Belachew, T. Effect of guided counseling on nutritional status of pregnant women in West Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyurin, I.S.; Aqmarina, A.N.; Rahmah, H.A.; Hasanah, A.U.; Silaen, C.N.B. Effect of stunting education using brainstorming and audiovisual methods towards knowledge of mothers with stunted children. Ilmu Gizi Indones. 2019, 2, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryati, S.; Supriyadi, S. The Effect of booklet education about children nutrition needs toward knowledge of mother with stunting children in Pundong primary health center work area Bantul Yogyakarta. In Proceedings of the 4th International Nursing Conference, Jember, Indonesia, 7 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinengsih, S.; Hakim, N. The influence of the lecture method and the android-based application method on adolescent reproductive health knowledge. J. Kebidanan Malahayati 2020, 6, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaw, M.W.; Bitew, A.A.; Gebremariam, A.D.; Fentahun, N.; Açık, M.; Ayele, T.A. Low Economic Class Might Predispose Children under Five Years of Age to Stunting in Ethiopia: Updates of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 2169847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassanga, P.; Okello-Uma, I.; Ongeng, D. The status of nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices associated with complementary feeding in a post-conflict development phase setting: The case of Acholi sub-region of Uganda. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekawidyani, K.R.; Khomsan, A.; Dewi, M.; Thariqi, Y.A. Nutrition Knowledge, Breastfeeding and Infant Feeding Practice of Mothers in Cirebon Regency. Amerta Nutr. 2022, 6, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusoh, N.; Lee, J.L.F.; Tengah, R.Y.; Azmi, S.H.; Suherman, A. Association between nutrition knowledge and nutrition practice among Malaysian adolescent handball athletes. Malays. J. Nutr. 2021, 27, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukusuba, J.; Kikafunda, J.K.; Whitehead, R.G. Nutritional Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Women Living with HIV in Eastern Uganda. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2010, 28, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences. Frameworks for Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. October 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK395979/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Alristina, A.D.; Mahrouseh, N.; Irawan, A.S.; Laili, R.D.; Zimonyi-Bakó, A.V.; Feith, H.J. Prematurity and Low Birth Weight Among Food-Secure and Food-Insecure Households: A Comparative Study in Surabaya, Indonesia. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrie, R.A. Demographic, Genetic, and Environmental Factors That Modify Disease Course. Neurol. Clin. 2011, 29, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socioeconomic Status. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/socioeconomic-status (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- McKinsey & Company. Personalized Medicine—The Path Forward. Translational Informatics. 2013. pp. 35–60. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/mckinsey-personalized-medicine-compendium-the-path-forward (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Fiala, M.A.; Finney, J.D.; Liu, J.; Stockerl-Goldstein, K.E.; Tomasson, M.H.; Vij, R.; Wildes, T.M. Socioeconomic Status is Independently Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Multiple Myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sun, B.; Du, Z.; Lv, G. How Wealth Inequality Affects Happiness: The Perspective of Social Comparison. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 829707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Centre on Quality of Life. Available online: https://www.acqol.com.au/instruments (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Miller, B.K.; Zivnuska, S.; Kacmar, K.M. Self-perception and life satisfaction. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 139, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; UNICEF. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Definitions and Measurement Methods; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 7, pp. 1372–1380. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018389 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Kliemann, N.; Wardle, J.; Johnson, F.; Croker, H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, Y.; Narumi-Hyakutake, A. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and nutritional adequacy in Japanese university students: A cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Sci. 2025, 14, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, J.; Zakar, R.; Butt, M.S.; Aadil, R.M.; Ali, Z.; Bukhari, G.M.J.; Ishaq, M.; Fischer, F. Application of the Boruta algorithm to assess the multidimensional determinants of malnutrition among children under five years living in southern Punjab, Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursa, M.B.; Rudnicki, W.R. Feature Selection with the Boruta Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaringan Dokumentasi dan Informasi Hukum. Available online: https://dokumjdih.jatimprov.go.id/arsip/info/48965.html (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Pandey, S. Socio-economic and Demographic Determinants of Antenatal Care Services Utilization in Central Nepal. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2013, 2, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, T.E.; Linehan, L.; O’Donoghue, K.; Byrne, M.; Meaney, S. Facilitators and barriers to seeking and engaging with antenatal care in high-income countries: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, E3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Sahni, B.; Jena, P.K. Education, employment, economic status and empowerment: Implications for maternal health care services utilization in India. J. Public Aff. 2020, 21, e2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahreem, A.; Rakha, A.; Anwar, R.; Rabail, R.; Maerescu, C.M.; Socol, C.T.; Criste, F.L.; Abdi, G.; Aadil, R.M. Impact of maternal nutritional literacy and feeding practices on the growth outcomes of children (6–23 months) in Gujranwala: A cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1460200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.M.; Newell, M.-L.; Padmadas, S. Maternal socioeconomic status and infant feeding practices underlying pathways to child stunting in Cambodia: Structural path analysis using cross-sectional population data. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbratto-Dobe, S.A.; Segnon, H.B. Is mother’s education essential to improving the nutritional status of children under five in Côte d′Ivoire? SSM—Health Syst. 2025, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyo, W.Y.; Khin, O.K.; Aung, M.H. Mothers’ Nutritional Knowledge, Self-efficacy, and Practice of Meal Preparation for School-age Children in Yangon, Myanmar. Makara J. Health Res. 2021, 25, 10–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Strauss, J.; Henriques, M.-H. How Does Mother’s Education Affect Child Height? J. Hum. Resour. 1991, 26, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prickett, K.C.; Augustine, J.M. Maternal Education and Investments in Children’s Health. J. Marriage Fam. 2015, 78, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-C.; Zou, S.-M.; Ding, Z.; Fang, J.-Y. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant females in 2020 Shenzhen China: A cross-sectional study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 32, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forh, G.; Apprey, C.; Agyapong, N.A.F. Nutritional knowledge and practices of mothers/caregivers and its impact on the nutritional status of children 6–59 months in Sefwi Wiawso Municipality, Western-North Region, Ghana. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekutamba, A.F.; Ashipala, D.O. Nutritional knowledge and practices of mothers with malnourished children in a regional hospital in Northeast Namibia. J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsu, B.K.; Guure, C.; Laar, A.K. Determinants of overweight with concurrent stunting among Ghanaian children. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.R.K.; Rahman, S.; Billah, B.; Kabir, R.; Perera, N.K.P.; Kader, M. The prevalence and socio-demographic risk factors of coexistence of stunting, wasting, and underweight among children under five years in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soekatri, M.Y.E.; Sandjaja, S.; Syauqy, A. Stunting Was Associated with Reported Morbidity, Parental Education and Socioeconomic Status in 0.5–12-Year-Old Indonesian Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silas, V.D.; Pomat, W.; Jorry, R.; Emori, R.; Maraga, S.; Kue, L.; Berry, N.; Aga, T.; Luu, H.N.; Ha, T.H.; et al. Household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated socioeconomic demographic factors in Papua New Guinea: Evidence from the Comprehensive Health and Epidemiological Surveillance System. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e013308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arini, D.; Ernawati, D.; Hayudanti, D.; Alristina, A.D. Impact of socioeconomic change and hygiene sanitation during pandemic COVID-19 towards stunting. Int. J. Public Health Sci. (IJPHS) 2022, 11, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, N.B.; Mala Ali, M.; Celestin, B.L.N.; Kalombola, C.; Gérard, M.M.; Bavon, T.M.; Patient, N.B.; Crédo, K.T.; Déogratias, M.N.H.; Oscar, L.N. Complementary Feeding Practices Associated with Malnutrition in Children Aged 6–23 Months in the Tshamilemba Health Zone, Haut-Katanga, DRC, 2021. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2023, 7, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuita, F.; Mukuria, A.; Muhomah, T.; Locklear, K.; Grounds, S.; Martin, S.L. Fathers and grandmothers experiences participating in nutrition peer dialogue groups in Vihiga County, Kenya. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17 (Suppl. S1), e13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; McCann, J.K.; Gascoigne, E.; Allotey, D.; Fundira, D.; Dickin, K.L. Engaging family members in maternal, infant and young child nutrition activities in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic scoping review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17 (Suppl. S1), e13158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, N.; Acharya, K.; Upadhya, D.P.; Pathak, S.; Pokharel, S.; Pradhan, P.M.S. Infant and young child feeding practices and its associated factors among mothers of under two years children in a western hilly region of Nepal. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaiya, M.A.; Anjorin, S.; Uthman, O.A. Income and education disparities in childhood malnutrition: A multi-country decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; la Paz, S.M.-D.; Leon, M.J.; Rivero-Pino, F. Effects of Malnutrition on the Immune System and Infection and the Role of Nutritional Strategies Regarding Improvements in Children’s Health Status: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noort, M.W.J.; Renzetti, S.; Linderhof, V.; du Rand, G.E.; Marx-Pienaar, N.J.M.M.; de Kock, H.L.; Magano, N.; Taylor, J.R.N. Towards Sustainable Shifts to Healthy Diets and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa with Climate-Resilient Crops in Bread-Type Products: A Food System Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunniran, O.P.; Ayeni, K.I.; Shokunbi, O.S.; Krska, R.; Ezekiel, C.N. A 10-year (2014–2023) review of complementary food development in sub-Saharan Africa and the impact on child health. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniang’o, R.; Maingi, Z.; Jaika, S.; Konyole, S. Africa’s contribution to global sustainable and healthy diets: A scoping review. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1519248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asebe, H.A.; Asmare, Z.A.; Mare, K.U.; Kase, B.F.; Tebeje, T.M.; Asgedom, Y.S.; Shibeshi, A.H.; Lombebo, A.A.; Sabo, K.G.; Fente, B.M.; et al. The level of wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in sub-Saharan African countries: Multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1336864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.D.; Ruel, M.T. Economic shocks predict increases in child wasting prevalence. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, S.A.; Okunlola, D.A.; Adegboye, O.A.; Adedeji, I.A. Mother’s education and nutritional status as correlates of child stunting, wasting, underweight, and overweight in Nigeria: Evidence from 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. Nutr. Health 2024, 30, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okutse, A.O.; Athiany, H. Socioeconomic disparities in child malnutrition: Trends, determinants, and policy implications from the Kenya demographic and health survey (2014–2022). BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, S.; Ajmal, L.; Ajmal, M.; Nawaz, G. Association of Malnutrition with Weaning Practices Among Infants in Pakistan. Cureus 2022, 14, e31018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.A.d.M.; Freire, A.K.G.; Gonçalves, V.S.S. Exclusive breastfeeding and underweight in children under six months old monitored in primary health care in Brazil, 2017. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2020, 39, e2019293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erda, R.; Hamidi, D.; Desmawati, D.; Rasyid, R.; Sarfika, R. Evaluating socio-demographic, behavioral, and maternal factors in the dual burden of malnutrition among school-aged children in Batam, Indonesia. Narra J 2025, 5, e2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roswita, N.; Dartanto, T. Maternal Decision Making and Children’s Nutritional Status: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Èkon. Kependud. Kel. 2024, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembedza, V.P.; Mapara, J.; Chopera, P.; Macheka, L. Relationship between cultural food taboos and maternal and child nutrition: A systematic literature review. N. Afr. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2025, 9, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekey, A.; Masumo, R.M.; Jumbe, T.; Ezekiel, M.; Daudi, Z.; Mchome, N.J.; David, G.; Onesmo, W.; Leyna, G.H. Food taboos and preferences among adolescent girls, pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and children aged 6–23 months in Mainland Tanzania: A qualitative study. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayumba, R. To Explore the Perceived Food Taboos during Pregnancy and their Relation to Maternal Nutrition and Health. TEXILA Int. J. Acad. Res. 2023, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Strategy for Improved Nutrition of Children and Women in Developing Countries; (1990 session: N. York); UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/227230 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- ECDAN. Child Nutrition Report 2025. Available online: https://ecdan.org/news/child-nutrition-report-2025/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SES: | ||

| Low | 36 | 5.5 |

| Middle | 588 | 89.5 |

| High | 33 | 5.0 |

| MNK: | ||

| Low | 180 | 27.4 |

| Moderate | 473 | 72.0 |

| High | 4 | 0.6 |

| Mother’s age: | ||

| <20 years | 1 | 2.0 |

| 20 to 29 years | 100 | 15.2 |

| 30 to 39 years | 336 | 51.1 |

| ≥40 years | 220 | 33.5 |

| Family size: | ||

| ≤3 members | 114 | 17.4 |

| 4–6 members | 449 | 68.3 |

| >6 members | 94 | 14.3 |

| Under-five siblings: | ||

| ≤2 children | 621 | 94.5 |

| ≥3 children | 36 | 5.5 |

| Child gender: | ||

| Boy | 326 | 49.6 |

| Girl | 331 | 50.4 |

| Child health insurance: | ||

| Yes | 353 | 53.7 |

| No | 304 | 46.3 |

| Stunting: | ||

| Yes | 166 | 25.3 |

| No | 491 | 74.7 |

| Wasting: | ||

| Yes | 106 | 16.1 |

| No | 551 | 83.9 |

| Underweight: | ||

| Yes | 148 | 22.5 |

| No | 509 | 77.5 |

| Ever BF: | ||

| Yes | 604 | 91.9 |

| No | 53 | 8.1 |

| Exclusive BF: | ||

| Yes | 245 | 37.3 |

| No | 412 | 62.7 |

| Initiation BF: | ||

| Within 1 h | 214 | 32.6 |

| After 1 h or more | 443 | 67.4 |

| Weaning practices: | ||

| Less than 6 months | 124 | 18.9 |

| Between 6 months and 24 months | 330 | 50.2 |

| 24 months or more | 203 | 30.9 |

| Mother’s education: | ||

| No education | 4 | 0.6 |

| Primary school | 179 | 27.2 |

| High school | 376 | 57.2 |

| Higher degree and above | 98 | 14.9 |

| Mother’s employment status: | ||

| Employed | 278 | 42.3 |

| Unemployed | 379 | 57.7 |

| Family income: | ||

| ≤IDR 2,300,000 per month | 259 | 39.4 |

| IDR 2,300,001–IDR 4,500,000 per month | 291 | 44.3 |

| IDR 4,500,001–IDR 5,700,000 per month | 61 | 9.3 |

| IDR 5,700,001–IDR 7,000,000 per month | 26 | 4.0 |

| IDR 7,000,001–IDR 10,000,000 per month | 13 | 2.0 |

| >IDR 10,000,001 per month | 7 | 1.1 |

| Car ownership: | ||

| Yes | 83 | 12.6 |

| No | 574 | 87.4 |

| House ownership: | ||

| Yes | 213 | 32.4 |

| No | 444 | 67.6 |

| Subjective wealth status: | ||

| Rather better off | 202 | 30.7 |

| Average | 436 | 66.4 |

| Rather worse off | 19 | 2.9 |

| Code Variables | Mean Imp. | Median Imp. | Min. Imp. | Max. Imp. | Norm Hits | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1. SES | 9.398 | 9.543 | 4.025 | 14.438 | 0.980 | Confirmed |

| P3. Stunting | 3.003 | 3.024 | −3.153 | 9.706 | 0.374 | Tentative |

| P4. Wasting | −0.135 | −0.301 | −1.896 | 2.507 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P5. Underweight | −0.505 | −0.182 | −2.009 | 1.029 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P6. Child gender | 3.812 | 3.649 | −2.207 | 9.991 | 0.475 | Tentative |

| P7. Health insurance | 0.202 | 0.276 | −5.197 | 5.626 | 0.051 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 0.064 | 0.518 | −3.104 | 2.075 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P9. Family size | −0.901 | −0.789 | −2.344 | 1.277 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five siblings | −0.243 | −0.551 | −1.527 | 2.406 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11. Exclusive BF | 0.837 | 0.589 | −0.403 | 2.412 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P12. Ever BF | 0.887 | 0.890 | −1.600 | 2.638 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | 5.892 | 5.516 | −1.014 | 11.589 | 0.727 | Confirmed |

| P14. Weaning practices | 0.938 | 0.550 | −2.183 | 7.634 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P15. Mother education | 9.521 | 9.556 | 3.691 | 16.766 | 0.980 | Confirmed |

| P16. Mother employment | 3.806 | 3.795 | −0.569 | 11.37 | 0.556 | Tentative |

| P17. Family income | 13.013 | 13.43 | 6.525 | 18.811 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P18. Car ownership | −0.636 | −0.815 | −1.824 | 0.857 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P19. House ownership | 0.313 | 0.421 | −2.235 | 2.812 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P20. Subjective wealth status | −0.225 | −0.202 | −2.006 | 1.542 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| Code Variables | Mean Imp. | Median Imp. | Min. Imp. | Max. Imp. | Norm Hits | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1. SES | 6.075 | 6.164 | 0.851 | 14.483 | 0.657 | Tentative |

| P2. MNK | 0.301 | 0.181 | −1.263 | 2.455 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P4. Wasting | 24.503 | 26.458 | 6.830 | 36.536 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P5. Underweight | 62.803 | 67.701 | 31.805 | 76.340 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P6. Child gender | 3.912 | 3.412 | −2.931 | 12.018 | 0.465 | Tentative |

| P7. Health insurance | −1.720 | −1.764 | −2.786 | −0.243 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 0.388 | 0.618 | −1.079 | 1.977 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P9. Family size | −0.382 | −0.413 | −2.300 | 1.840 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five siblings | −0.475 | −1.004 | −1.650 | 1.117 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11. Exclusive BF | 0.198 | 0.179 | −1.073 | 1.593 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P12. Ever BF | −0.052 | 0.467 | −3.014 | 1.290 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | −0.645 | −0.272 | −2.602 | 0.507 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P14. Weaning practices | 0.387 | 0.918 | −1.929 | 2.606 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P15. Mother education | 1.549 | 1.685 | −1.023 | 3.082 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P16. Mother employment | −1.570 | −1.425 | −3.790 | 1.211 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P17. Family income | 0.708 | 0.473 | −2.582 | 6.074 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P18. Car ownership | −0.356 | −0.050 | −1.767 | 2.084 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P19. House ownership | 0.820 | 1.075 | −3.153 | 4.024 | 0.030 | Rejected |

| P20. Subjective wealth status | 2.819 | 2.993 | −4.321 | 11.632 | 0.374 | Tentative |

| Code Variables | Mean Imp. | Median Imp. | Min. Imp. | Max. Imp. | Norm Hits | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1. SES | 6.697 | 6.900 | 0.396 | 10.973 | 0.919 | Confirmed |

| P3. MNK | −0.335 | −0.504 | −1.859 | 2.062 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P3. Stunting | 18.184 | 18.585 | 9.927 | 26.268 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P5. Underweight | 57.893 | 59.973 | 41.257 | 68.979 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P6. Child gender | −0.149 | −0.605 | −2.343 | 2.689 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P7. Health insurance | 0.476 | 0.419 | −1.494 | 2.018 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 6.144 | 5.829 | 0.292 | 11.605 | 0.889 | Confirmed |

| P9. Family size | 1.704 | 1.821 | −2.435 | 5.220 | 0.131 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five siblings | −1.388 | −1.436 | −2.333 | −0.468 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11. Exclusive BF | 0.374 | 0.313 | −2.203 | 2.160 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P12. Ever BF | −0.722 | −0.460 | −2.129 | 0.352 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | 1.491 | 1.604 | −1.751 | 3.483 | 0.030 | Rejected |

| P14. Weaning practices | 1.546 | 1.626 | −0.469 | 3.599 | 0.040 | Rejected |

| P15. Mother education | 3.604 | 3.399 | −2.304 | 9.878 | 0.545 | Confirmed |

| P16. Mother employment | 0.775 | 0.370 | −1.026 | 3.781 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P17. Family income | 2.509 | 2.552 | −2.512 | 6.517 | 0.465 | Tentative |

| P18. Car ownership | 1.872 | 1.729 | −0.770 | 5.997 | 0.081 | Rejected |

| P19. House ownership | 4.088 | 3.901 | −0.468 | 11.262 | 0.566 | Tentative |

| P20. Subjective wealth status | −0.125 | −0.535 | −1.265 | 2.428 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| Code Variables | Mean Imp. | Median Imp. | Min. Imp. | Max. Imp. | Norm Hits | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1. SES | 1.184 | 1.103 | −0.395 | 3.958 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P2. MNK | 0.024 | −0.150 | −3.965 | 2.393 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P3. Stunting | 40.846 | 42.037 | 28.338 | 48.492 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P4. Wasting | 65.480 | 67.689 | 44.840 | 74.953 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P6. Child gender | 0.033 | 0.158 | −1.773 | 1.959 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P7. Health insurance | −1.061 | −0.986 | −2.302 | 0.035 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 3.003 | 3.227 | −2.405 | 9.000 | 0.444 | Tentative |

| P9. Family size | 1.713 | 1.838 | −1.642 | 5.277 | 0.131 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five siblings | −0.146 | −0.225 | −1.900 | 1.331 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11. Exclusive BF | 3.086 | 2.995 | −1.604 | 8.378 | 0.465 | Tentative |

| P12. Ever BF | −0.969 | −1.004 | −2.206 | 0.412 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | 0.165 | 0.403 | −2.381 | 2.601 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P14. Weaning practices | 7.546 | 7.621 | 0.878 | 19.141 | 0.869 | Confirmed |

| P15. Mother education | 0.785 | 0.952 | −1.683 | 2.981 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P16. Mother employment | 1.233 | 1.422 | −1.576 | 2.680 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P17. Family income | 1.032 | 1.137 | −2.124 | 3.358 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P18. Car ownership | 0.085 | 0.109 | −1.864 | 1.676 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P19. House ownership | −0.783 | −0.622 | −2.573 | 0.187 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P20. Subjective wealth status | 3.578 | 3.490 | −1.337 | 10.594 | 0.465 | Tentative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alristina, A.D.; Laili, R.D.; Nagy, É.; Feith, H.J. The Importance of Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Maternal Nutrition Knowledge and Undernutrition Among Children Under Five. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213355

Alristina AD, Laili RD, Nagy É, Feith HJ. The Importance of Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Maternal Nutrition Knowledge and Undernutrition Among Children Under Five. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213355

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlristina, Arie Dwi, Rizky Dzariyani Laili, Éva Nagy, and Helga Judit Feith. 2025. "The Importance of Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Maternal Nutrition Knowledge and Undernutrition Among Children Under Five" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213355

APA StyleAlristina, A. D., Laili, R. D., Nagy, É., & Feith, H. J. (2025). The Importance of Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Maternal Nutrition Knowledge and Undernutrition Among Children Under Five. Nutrients, 17(21), 3355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213355