Simple Summary

The treatment of cancer has progressed greatly with the advent of immunotherapy and gene therapy, including the use of nonreplicating adenoviral vectors to deliver genes with antitumor activity for cancer gene therapy. Even so, the successful application of these vectors may benefit from modifications in their design, including their molecular structure, so that specificity for the target cell is increased and off-target effects are minimized. With such improvements, we may find new opportunities for systemic administration of adenoviral vectors as well as the delivery of strategic antigen targets of an antitumor immune response. We propose that the improvement of nonreplicating adenoviral vectors will allow them to continue to hold a key position in cancer gene therapy and immunotherapy.

Abstract

Recent preclinical and clinical studies have used viral vectors in gene therapy research, especially nonreplicating adenovirus encoding strategic therapeutic genes for cancer treatment. Adenoviruses were the first DNA viruses to go into therapeutic development, mainly due to well-known biological features: stability in vivo, ease of manufacture, and efficient gene delivery to dividing and nondividing cells. However, there are some limitations for gene therapy using adenoviral vectors, such as nonspecific transduction of normal cells and liver sequestration and neutralization by antibodies, especially when administered systemically. On the other hand, adenoviral vectors are amenable to strategies for the modification of their biological structures, including genetic manipulation of viral proteins, pseudotyping, and conjugation with polymers or biological membranes. Such modifications provide greater specificity to the target cell and better safety in systemic administration; thus, a reduction of antiviral host responses would favor the use of adenoviral vectors in cancer immunotherapy. In this review, we describe the structural and molecular features of nonreplicating adenoviral vectors, the current limitations to their use, and strategies to modify adenoviral tropism, highlighting the approaches that may allow for the systemic administration of gene therapy.

4. Strategies to Modify Adenovirus Tropism

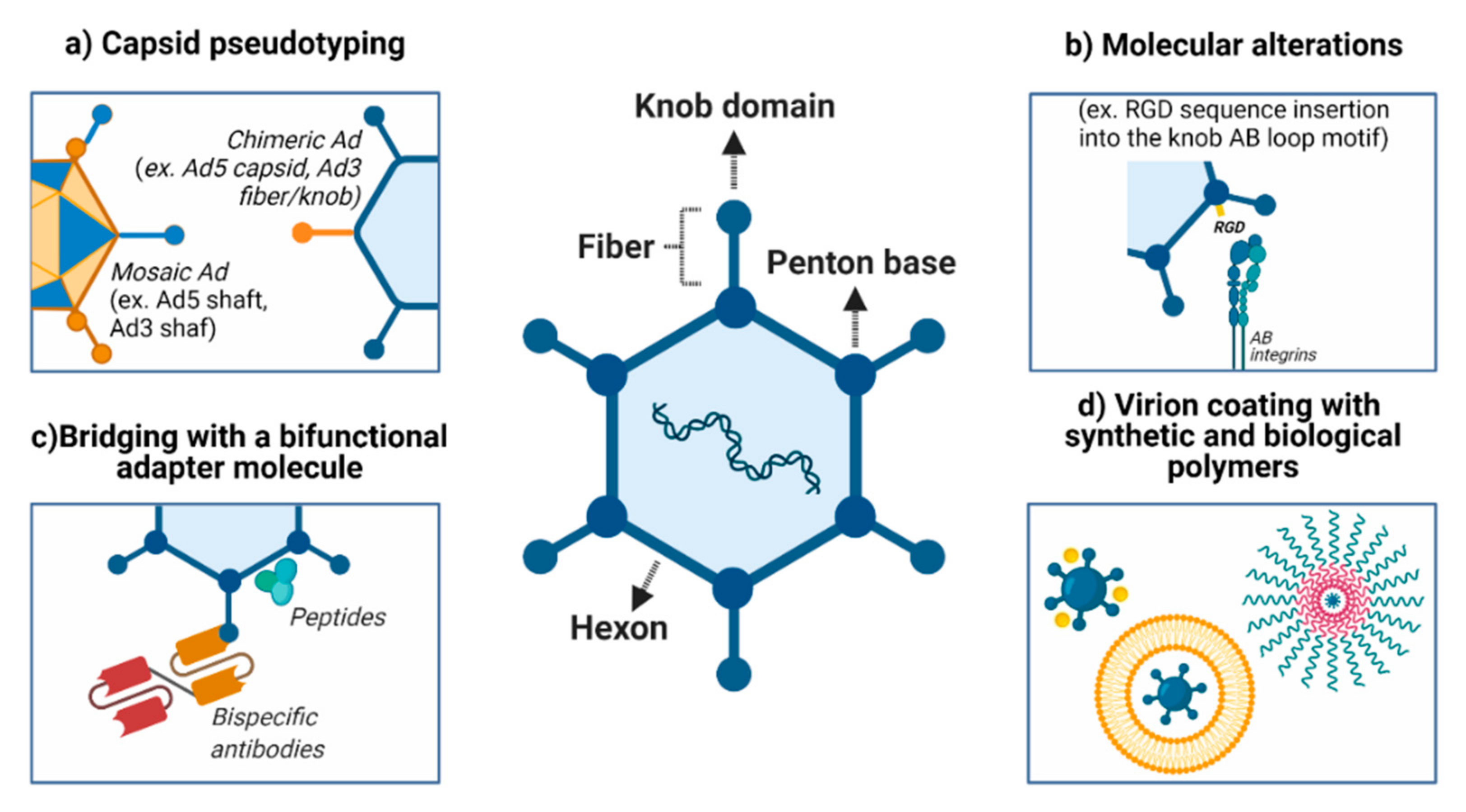

Although Ads infect many different types of cells, low (or no) expression of CAR, especially in tumor cells, confounds the attachment step and represents one of the hurdles to gene therapy using adenoviral vectors. Several strategies have been employed to overcome this barrier and redirect the Ads to the intended recipient and, consequently, decrease off-target effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Improvements in vector delivery to and targeting of cancer cells. (a) Several approaches can be used to modify viral attachment and entry, such as inhibiting the binding to natural receptors (detargeting) and creating tropism for neoplasms and their metastatic foci (retargeting). (b) An alternative to CAR-mediated viral attachment is modifying the fiber (for example, incorporation of the RGD sequence into the knob AB-loop motif). (c) Ad structure permits retargeting through the incorporation of synthetic molecules and antibody fragments within the virus capsid. (d) Both biological (e.g., cell membrane, liposome) and chemical (e.g., gold, silver, PEG) approaches may be used to coat the virus and improved delivery, especially for the systemic route. PEG: polyethylene glycol. Created with BioRender.com.

4.1. Modifications in Viral Entry: Attachment Receptors and Virus Internalization

To explore the targeting of adenovirus particles to tumor cells, initial events related to infection/transduction must be modulated: (i) viral attachment and (ii) viral entry. This strategy can target tissues by inhibiting binding to natural receptors (detargeting) in normal liver cells, for example, and, simultaneously, creating tropism for neoplasms and their metastatic foci (retargeting) [137]. Another strategy is pseudotyping, the creation of variants by recombining their capsid proteins. Here, we detail works that have used a variety of strategies to modify tropism.

The tropism of HAd5 is predominantly mediated by the interaction of fiber/knob with CAR. As an alternative to CAR-mediated viral attachment, one of the classical fiber modifications is the incorporation of the RGD sequence into the knob AB-loop motif, which greatly expands the spectrum of cell types that may be transduced [138]. Even so, the genetic incorporation of an RGD-4C peptide into the HI loop or the C-terminal end of the HAd5 fiber knob modifies the Ad knob domain without ablating native CAR-binding [139]. Another possibility is the insertion of positively charged polylysine motifs [140]. This modification permits the virus to target the tumor cell’s heparan sulfate proteoglycans, common constituents of the cell surface, and the extracellular matrix, overexpressed in several different cancer types, including cervical cancer [141].

On the other hand, directing transduction and expression of the transgenes to occur only in tumor cells (but not in normal cells) should minimize the adverse effects of the therapy. Wickham and coworkers [142] successfully used bispecific antibodies to promote the targeting of an adenoviral vector to endothelial and smooth muscle cells. However, the attempt to noncovalently associate antibodies or molecules with the surface of the viral particle may be hampered by the instability of this binding, especially if used in vivo. For this reason, the adenovirus fiber gene sequence can be edited and, thus, the peptide ligands can be incorporated directly into the protein sequence [137,143,144,145].

Taking cues from the phage display technique, adenovirus libraries can be generated with random peptide combinations and screened for their ability to transduce a particular cell type, thus refining specificity to tumor populations in a strict manner [146,147,148]. Joung et al. [148] devised a technique for producing adenovirus with modified fibers that involved cotransfecting a packaging cell with a plasmid encoding a genetically fiber-less adenovirus with a plasmid containing the open reading frames (ORFs) of the fiber of interest. Moreover, Yoshida et al. [144] developed a Cre-lox-mediated recombination system using a plasmid library encoding modified fiber and the adenoviral genome. Using this approach, these authors inserted unique peptides, each with seven random amino acids, into the AB-loop of the fiber, and, after screening, they were successful in targeting these viral vectors to glioma cells [143,149]. Although the idea seems highly promising, there are technical complications that hinder this approach. The compaction and self-assembly of the protein monomers to form the adenovirus particle is a very delicate process. The insertion of random peptides can compromise the final structure of the viral particle as well as virus production [150].

Even though two receptors are required for the adenovirus particle to penetrate the target cells, each interaction is a distinct step. While attachment receptors apparently only recognize the target cell, the HAd5 penton base–αv integrin interaction activates signaling pathways such as p38MAPK [151,152] and Rho GTPases [153], which then trigger changes in the cell cytoskeleton for endocytosis mediated by clathrin [153,154]. Interestingly, mutation of the penton base RGD sequence slows but does not impair virus internalization and infection, nor does it prevent liver tropism [86].

4.2. Pseudotyping the Capsid Using Components from Different Adenoviruses

Chimeric adenoviruses are usually based on HAd5 with the fiber or its knob domain replaced by that of another serotype [155]. This creates perspectives for the recombination of these subtypes and, thus, the modulation of targeting: a concept known as pseudotyping. However, the resulting range of tropisms will be restricted to the respective serotypes used in the construction and may not necessarily contemplate the range of existing receptors found in neoplasms. Table 3 summarizes important findings in studies that have employed adenovirus pseudotyping strategies.

Table 3.

Different studies using adenovirus pseudotyping strategies.

4.3. Encapsulation of Adenovirus Using Synthetic Polymers

Shielding the virus with nanoparticles allows the Ad to escape immune recognition and avoid the undesirable accumulation of the vector in the liver upon systemic delivery. Furthermore, this approach can enhance the specific targeting of tumor cells. Several studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of encapsulation of negatively charged Ads with cationic liposomes or particles that aim to prevent virus clearance from circulation [162].

Some Ad features, such as regular geometries, well-characterized surface properties, and nanoscale dimensions, make it a biocompatible scaffold for a wide variety of inorganic and biological structures. The Ad capsid has free lysines, the majority of them located on hexon, penton, and fiber proteins, which can be covalently linked to other molecules such as polymers, sugars, biotin, and fluorophores [163]. Polymers offer a wide range of conjugation and encapsulation that make them a safe option for immunotherapy. The main biopolymers studied are polyethylene glycol (PEG) and hydroxylpropyl methacrylamide (pHPMA), the latter being covalently bound to capsid proteins; thus, it can efficiently transduce solid tumors after intravenous injection into mice [164]. The first study using this polymer demonstrated passive tumor targeting of polymer-coated adenoviruses administered by intravenous injection; the authors observed that the coated virus accumulated inside solid subcutaneous AB22 mesothelioma tumors 40 times more than the unmodified virus [164].

As mentioned, Ad structure permits retargeting through the incorporation of synthetic molecules and antibody fragments within the virus capsid. For instance, PEG is an uncharged, hydrophilic, nonimmunogenic, synthetic linear polymer (CH2CH2O repetitions) [165] that is frequently utilized in the biopharmaceutical industry and can be useful to protect therapeutic molecules from proteolysis as well as humoral and cellular immune responses [166]. According to Fisher et al. [164], one advantage of vector PEGylation is the retention of viability after storage at various temperatures compared to conventional Ads. Covalent attachment of PEG to the adenovirus capsid may be achieved by using PEG activation mechanisms. PEG presents hydroxyl groups (OH) that make PEG-protein bonds impossible; thus, it is necessary to use chemical activation before protein attachment. In the specific case of adenoviruses, activation can be achieved through the use of tresyl-monomethoxypolyethylene glycol (TMPEG), succinimidyl succinate-monomethoxypolyethylene glycol (SSPEG), or cyanuric chloride-monomethoxypolyethylene glycol (CCPEG), which react preferentially with lysine residues in the capsid, thus supporting the formation of covalent bonds with PEG [167].

In addition to the PEGylation of the virus particle, ligands can also bind to the opposite extremity of PEG, thus providing a specific ligand to retarget the virus to the corresponding cellular receptor.

Such approaches also aid the vector in reaching distant tumor sites, as found by Eto et al. [167]. They used a cationic liposome that was composed of (1, 2-dioleoyloxypropyl)-N, N, N-trimethy-lammonium chloride:cholesterol to encapsulate the Ad vectors carrying the antiangiogenic gene (pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF)). The results showed that systemic administration of Ad-PEDF/liposome was well tolerated and caused the suppression of tumor growth. The coated Ad-PEDF increased apoptosis compared to uncoated Ad in the B16-F10 melanoma cell line and inhibited murine pulmonary metastasis in vivo. Moreover, Ad-luciferase encapsulated with liposome exhibited decreased liver tropism and increased transduction in the lung. Additionally, the anti-Ad IgG level after administration of the Ad-PEDF/liposome was significantly lower compared to Ad-PEDF alone. Eto et al. [167] showed that positively charged 14-nm gold nanoparticles increased the efficiency of Ad infection in mesenchymal stem cells, usually refractory to Ad transduction, mainly because CAR expression is absent or downregulated. The strategies described here support future exploration of additional formulations for liposome-encapsulated adenoviruses and their ability to target cancer cells.

4.4. Cancer Cell Membrane-Coated Adenoviral Vectors

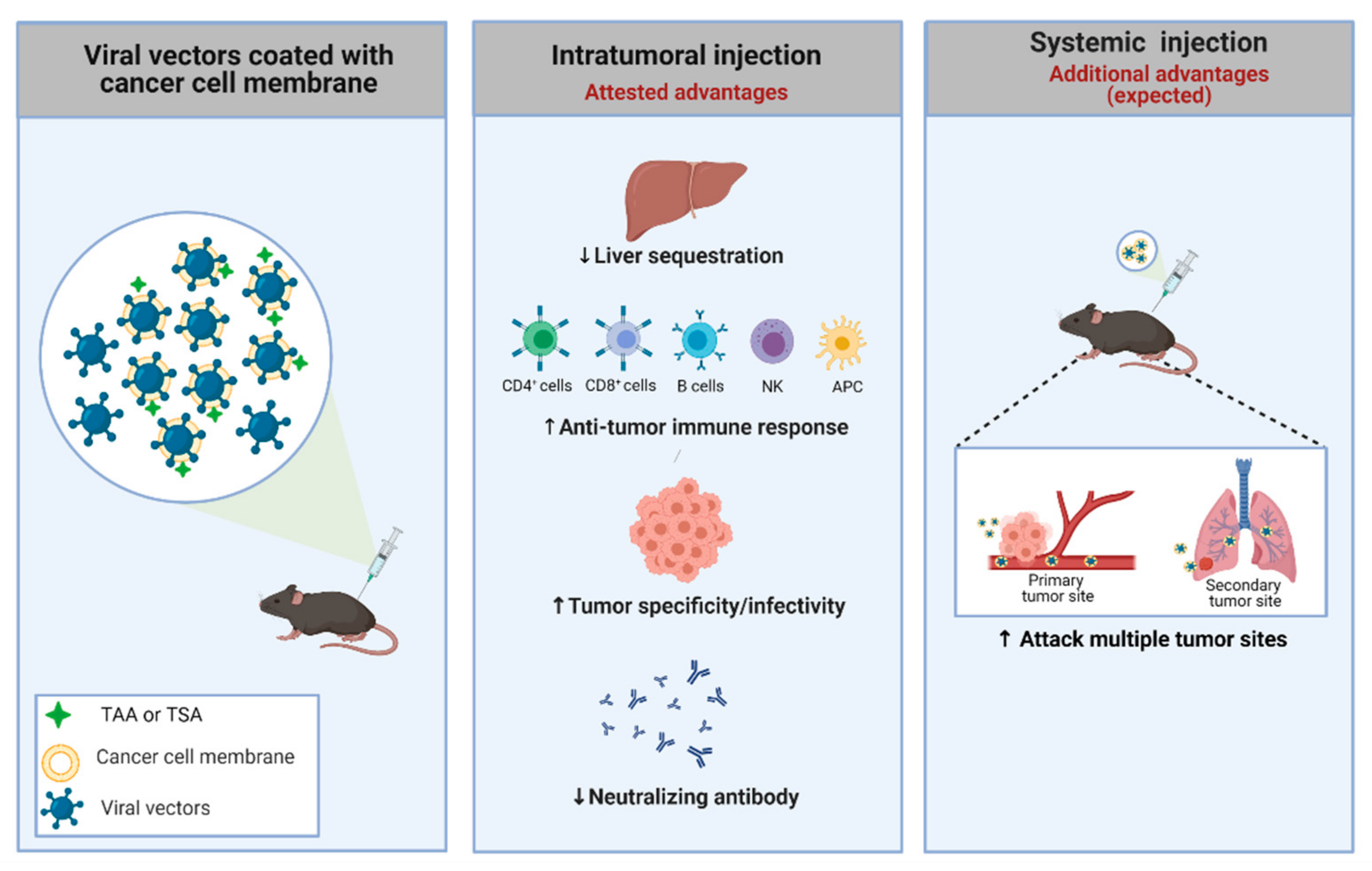

Nanoparticle-based delivery systems have been extensively explored for improving cancer treatment. Cell membranes, which can be obtained from a variety of source cells, including leukocytes, platelets, red blood cells, and cancer cells, are being employed to encapsulate particles such as liposomes, polymers, silica, and Ad vectors in order to improve tumor-targeted drug delivery in addition to prolonged circulation time, reduced interaction with macrophages, and decreased nanoparticle uptake in the liver [168]. The membrane-based functions of cancer-related cells include extravasation, chemotaxis, and cancer cell adhesion [169]. As a source of cell membranes, cancer cells offer certain advantages. They can be obtained from cell lines or patient samples and possess a wide range of membrane surface proteins, such as MHC, TAAs, and neoantigens, that can program the immune system to attack local and distant tumor sites [170], as represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Strategy used to improve the specificity of adenoviral vectors. An adenovirus coated with a cancer cell membrane has some advantages, such as the presence of TSA and TAA, which aids the anti-tumor immune response. Additionally, the membrane can be engineered to present specific molecules/receptors, improving the power of interaction with the tumor. Moreover, the viral coating can offer several benefits, including suppression of liver toxicity, increase of specific infectivity to cancer cells, preferential antitumor (not antiviral) immune response, and escape from pre-existing neutralizing antibodies in both routes of delivery (intratumoral and systemic). Systemic administration using virus coated with membranes could offer a highly desirable outcome: targeting metastatic foci. TAA: tumor-associated antigens; TSA: tumor-specific antigens. Created with BioRender.com.

Tumors frequently develop a variety of mechanisms to subvert immune attack, resulting in an immune-suppressive TME. Although tumor cells can stimulate a variety of cell types, including fibroblasts, immune-inflammatory cells, and endothelial cells, through the production and secretion of stimulatory growth factors and cytokines [171], the TME can be modulated by the tumor cells themselves and tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (including regulatory T-cells (Tregs)), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and alternatively activated (type 2) macrophages (M2), cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), expression of inhibitory receptors (such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)) or impediment of T-cell function, resulting in the reduced effectiveness of immunotherapy [172]. Although many TAAs have been identified, their immunogenicity is generally insufficient to elicit potent antitumor responses. Typically, when the tumor reaches the malignant stage, the most immunogenic tumor-specific antigens have been eliminated via negative selection. Frequently, the nanoparticles are associated with adjuvants, secretory cytokines, antibodies, and/or viral vectors to improve the immune response [173].

Coating polymeric nanoparticles with cancer cell membranes can be used for different types of cancer therapy. For anticancer drug delivery, Zhuang et al. [173] showed that polymeric nanoparticle cores made of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), a polymer coated in an MDA-MB-435 membrane, significantly increased cellular adhesion to the source cells compared to naked nanoparticles due to a homotypic binding mechanism. For cancer immunotherapy, the authors demonstrated that a polymer coated with a B16−F10 membrane, which creates a stabilized particle, facilitated the uptake of membrane-bound tumor antigens and, consequently, the presentation and maturation of DCs. Another approach using a biohybrid (tumor-membrane-coated) nanoparticle was also able to elicit an antitumor immune response in melanoma models, changing the microenvironment profile. The administration of the vaccine enhanced the activation of APCs and increased the priming of CD8+ T-cells. When combining the nanovaccine with a checkpoint inhibitor, 87.5% of the animals responded, including two complete remissions, when compared to the immune checkpoint inhibitor alone. These results point to opportunities for the association of nanoparticles and immunomodulators to enhance T-cell responses [174].

The effects from the association of polymers, cancer cell membranes, and adjuvants were also observed by Fontana et al. [175]. PLGA nanoparticles were loaded with the TLR7 agonist and then coated with membranes from B16-OVA cancer cells since the presentation of foreign peptide OVA permits the tracking of responses. The nanovaccine was able to enhance uptake by antigen-presenting cells and showed efficacy in delaying tumor growth as a preventative vaccine besides displaying activity against established tumors when coadministered with the anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody.

In another study, CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG) was used as an immunological adjuvant and encapsulated into PLGA nanoparticle cores coated with membranes derived from B16–F10 mouse melanoma cells. The effect of nanoformulation on DC maturation was observed by the upregulated expression of costimulatory markers CD40, CD80, CD86, and MHC-II. Both prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines presented positive results. In the prophylactic study using the poorly immunogenic wild-type B16–F10 model, tumor occurrence was prevented in 86% of mice 150 days after challenge with tumor cells. Interestingly, mice vaccinated with the CpG-nanoformulation alone had tumor growth comparable to the control group and a median survival of 22 days. This reinforces the role of the cancer cell membrane in targeting the elimination of malignant cells by the immune system. In the therapeutic model, mice challenged with B16–F10 cells and subsequently treated with the nanoformulation presented a modest ability to control tumor growth. However, the combination of nanoformulation and a checkpoint blockade cocktail (anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD1) significantly enhanced tumor growth control. As such, the results encourage further research into nanoparticle vaccine formulation and possible associations with other immunotherapies that modulate different aspects of immunity [176].

In a different strategy, Fusciello et al. [177] combined an oncolytic virus (due to its natural adjuvant properties) and cancer cell membranes carrying tumor antigens. They found that viral transduction was significantly increased with the coated virus, implying an uptake mechanism different than that utilized by the naked virus, which requires CAR, representing a significant advantage for transducing CAR-negative cell lines. Additionally, the coated virus was better able to control tumor growth compared to other treatments. The vaccination using coated viruses created a highly specific anticancer immune response, redirecting the immune response against the tumor [177]. Thus, personalized cancer vaccines can represent an alternative approach to target cancer even without determining specific antigens for each patient. We hypothesize that this approach will also be applicable to nonreplicating adenoviral vectors, though this has not yet been shown.

4.5. Association of Antibodies and Viral Structures

The incorporation of antibodies into the viral structure is another interesting option for creating specificity. Despite the obstacles to the use of conventional antibodies (human, murine, and goat), smaller molecules from other species, such as alpacas, can be added to the structure of the Ad capsid without disturbing its synthesis and assembly. For example, van Erp et al. [178] generated a single domain camelid antibody against the human carcinoembryonic antigen present in human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. They incorporated this molecule into the adenovirus capsid, achieving a more specific tropism for tumor cells and reducing off-target toxicity. Although the strategy was developed to retarget oncolytic viruses, it can also be used to improve nonreplicative adenoviral vectors.

Despite the cited possibilities, the need to re-engineer vectors de novo for each novel target may be an unnecessary and costly effort. Since it is possible to combat different kinds of cancers through similar molecular mechanisms, such as the induction of immunogenic cell death, the development of adaptable platforms may allow the establishment of virus-based therapies in a more scalable and affordable way. Such approaches may, in the future, permit low-effort adaptation of pre-existing therapies to target different cellular markers and treat other tumors.

A viable alternative may be the use of adapter molecules. Bhatia et al. [179] developed an anti-CXCR4 bispecific adapter (sCAR-CXCL12). Chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) is known to be overexpressed in a wide variety of cancers, such as melanoma [180] and breast cancer [181], and it is associated with metastasis and poor overall survival. Bhatia et al. [179] designed a recombinant adapter molecule composed of an ectodomain portion of the human CAR, followed by a 5-peptide linker (GGPGS) and a 6-His tag sequence, fused to the mature human chemokine CXCL12/SDF-1a sequence (CXCR4 ligand). According to the researchers, this bispecific adapter attenuated liver infection in vivo and a promoted a considerable increase in cancer cell infection, as observed in xenograft tumors in mice.

In another interesting work, Schmid et al. [182] achieved, simultaneously, the retargeting of type 5 adenovirus tropism to a specific cancer marker and the reduction of its liver sequestration. Unlike other adapter strategies, they utilized designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins). Similar to antibodies, these proteins can bind to a target with rather good specificity. Moreover, these molecules can be engineered to target different antigens on the cell surface [183]. Schmid et al. [182] designed an adenovirus-antigen adapter composed of three monomers. Each monomer was made of a retargeting DARPin, a flexible linker, a knob-binding DARPin, and a trimerization motif [182,184]. The last component is responsible for the stability of the complex, allowing the coating of the adenovirus fiber knob and, consequently, impeding virus natural tropism. In addition, according to the researchers and some early works, the removal of CAR and integrin interactions may reduce liver tropism [185,186], an effect also observed when those capsid sites are blocked by DARPin adapters. Furthermore, this protein was able to hide the region responsible for adenovirus–liver interaction without disturbing the adenovirus–integrin interaction. Nonetheless, the researchers developed an adenovirus-binding molecule, named “shield”, derived from humanized antihexon scFv, which was designed to bind to hexon proteins, effectively protecting them from neutralizing antibodies [182].

4.6. Genetic and Chemical Capsid Modifications and Association with Polymers

Other strategies have emerged that support the retargeting and detargeting of ade-noviral vectors. For example, the CGKRK peptide mediates the targeting of tumor cells and tumor neovasculature and has been tested for its ability to retarget PEGylated adenoviral vectors: PEG molecules are conjugated to the surface of the viral vector; then, the peptide is attached via a chemical reaction, resulting in its conjugation to the functional group of PEG [187]. Moreover, Bonsted and colleagues demonstrated that a linker between the poly(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) (pDMAEMA) and the epidermal growth factor (EGF), commonly overexpressed in tumors, efficiently transduced CAR-deficient cells [188,189]. Additionally, an EGF mimetic peptide linked to the cationic PAMAM (polyamidoamine) dendrimer polymer through a PEG linker has been used to retarget dendrimer-coated Ad vectors; it has been shown to increase transgene expression in target cells compared with the untargeted vector [190].

Kreppel et al. [191] introduced a genetic–chemical concept for vector re- and detargeting. For that, the authors genetically modified the virus in order to present cysteine residues in the capsid, including the fiber HI-loop [191], protein IX [192], and hexon [193]. The cysteine residues were then covalently modified with thiol-reactive coupling moieties, including ligands, shielding polymers, carbohydrates, small molecules, and fluorescent dyes [194]. Kreppel et al. demonstrated that amine-based PEGylation and thiol-based coupling of transferrin to the fiber knob HI-loop successfully retargeted the modified Ad vectors to CAR-deficient cells [191].

These studies highlight the possibility of creating adenoviral vector platforms that need no further genetic modification; thus, a wide variety of target tissues may be explored with the aim of improving specificity and decreasing the neutralizing effects of preexisting antibodies.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Many features make Ads interesting vehicles for the delivery of foreign antigenic proteins or gene therapy: large cloning capacity, genetic stability, and high in vivo transduction capacity in both dividing and nondividing cells. The natural antiviral immune response can be useful to reprogram the tumor microenvironment from “cold” to “hot” by inducing T-cell-specific immune responses and proinflammatory cytokine expression [195]. The success of therapy depends on several other factors, such as the quality, intensity, specificity, and half-life of immune responses against the tumor. In this scenario, neoantigens have emerged as an attractive target for cancer therapy. Major advances in using the non-self-peptides are the absence of pre-existing central tolerance, potential strong immunogenicity, and lower risk of autoimmunity diseases [196]. We expect that continued refinement of Ad vector design and a deeper understanding of neoantigens will converge to provide an exceptional platform for cancer immunotherapy.

Even so, we point out some limitations for the use of neoantigens in personalized medicine: (1) neoantigens are limited by the diversity of somatic mutations in different tumor types and their individual specificity; (2) the probability that the neoantigens are shared between patients is very low; (3) identification and verification of neoantigens is still time-consuming and expensive [197]. In addition, the construction of adenoviral vectors encoding each neoantigen would be costly and time-consuming; thus, approaches that do not require vector construction may be preferable, including the use of peptides and membrane coatings.

Otherwise, the effectiveness in the use of neoantigens has already been observed in preclinical [198,199] and clinical data [200,201,202]. In addition, patients with high mutation burden tumors, like melanoma [203,204], non small-cell lung cancer [205], and bladder cancer [206], have had more clinical benefit from checkpoint-blockade therapy than those with lower mutation loads [196]. Moreover, the prediction of peptides binding to MHC molecules and, consequently, the identification of neoepitopes able to stimulate the immune response are emerging as novel approaches that could be associated with adenoviral vectors, reversing part of the tumor-induced immunosuppression.

Recently, D’Alise and collaborators [207] demonstrated the satisfactory benefits of genetic vaccines based on Ads derived from nonhuman great apes (GAd) encoding multiple neoantigens applied in the CT26 murine colon carcinoma model. Both prophylactic and early therapeutic vaccinations elicited strong and effective T-cell responses and controlled tumor growth in mice. The tumor-infiltrating T-cells were diversified in animals treated with GAd and anti-PD1 compared to anti-PD1 alone [207]. The big challenge of neoantigens is the complexity in identifying immunogenic antigens unique to each patient. However, more optimized sequencing platforms and bioinformatics tools are helping to make personalized therapy truly viable. All in all, the data presented here highlight new perspectives of cancer vaccines and gene therapy using modified nonreplicating adenoviruses and different strategies to turn the immune response against the tumor more specific and robust, contributing to local and distant control of tumor progression.

Although viral delivery systems are quite promising strategies in gene therapy, there are some limitations to their clinical application. The major barriers are host immune responses that result in the clearance of vectors, interaction with plasma proteins, liver sequestration, Ad CAR-dependence, and off-target effects [208]. Regarding these issues, a number of genetic manipulations have been exploited to redirect adenovirus binding to different cell surface receptors and, consequently, increase affinity for the target, with lower adverse effects [50].

In this scenario, different strategies using coated viruses have emerged in recent years, and both biological and chemical approaches can be used to coat the virus and improve delivery, especially for the systemic route. Since these strategies involve using cancer cell membranes that can be obtained directly from tumor cell lines, they provide greater biocompatibility with the tumor site and, consequently, specifically target these cells [209]. A growing body of evidence suggests that cancer cell membrane-coated viruses can be delivered by the systemic route, improving the targeting of metastases, with higher retention time, lower immune recognition, and decreased liver sequestration, toxicity, and accumulation in healthy tissues. The induction of immunogenic cell death by nonreplicating Ad vectors is associated with innate immune responses, antigen processing and presentation, and, finally, the activation of the cellular immune response. While few examples currently exist of using membrane-coated adenoviral vectors, we hypothesize that this approach will continue to be studied, including in nonreplicating vectors.

In summary, improvements in vector delivery and targeting will provide an even greater potential for the use of nonreplicating adenoviral vectors in cancer immunotherapy. In particular, we envision vectors adapted to support systemic delivery, achieve tumor specificity, induce tumor cell death and supply specific antigens to guide antitumor immune responses.

Author Contributions

N.G.T. conceived the review topic, wrote and edited the text, and prepared the figures; A.C.M.D. wrote and edited the text and prepared the figures, F.A., J.C.d.S.d.L., O.A.R., and O.L.D.C. wrote and edited the text; B.E.S. edited the text and provided funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; grant 15/26580-9 (B.E.S.) and fellowships 17/25290-2 (N.G.T.), 18/25555-9 (A.C.M.D.), 17/25284-2 (O.A.R.), and 17/23068-0 (O.L.D.C.)). Funding was also provided by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; fellowships 134305/2018-3 (J.C.d.S.d.L.) and 302888/2017/9 (B.E.S.)).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ginn, S.L.; Amaya, A.K.; Alexander, I.E.; Edelstein, M.; Abedi, M.R. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2017: An update. J. Gene Med. 2018, 20, e3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-W.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.J.; Chandler, L.A.; Lin, H.; et al. The First Approved Gene Therapy Product for Cancer Ad- P53 (Gendicine): 12 Years in the Clinic. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. A Phase II Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Recombinant Vaccine for COVID-19 (Adenovirus Vector). 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04341389 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Library of Medicine. ChiCTR2000030906. A Phase I Clinical Trial for Recombinant Novel Coronavirus (2019-COV) Vaccine (Adenoviral Vector). 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04313127 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR). ChiCTR2000031781. A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Phase II Clinical Trial for Recombinant Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCOV) Vaccine (Adenovirus Vector). 2020. Available online: http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=52006 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Library of Medicine. Phase I Clinical Trial of a COVID-19 Vaccine in 18–60 Healthy Adults. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04313127 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Library of Medicine. Phase I/II Clinical Trial of Recombinant Novel Coronavirus Vaccine (Adenovirus Type 5 Vector) in Canada. 2020. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04398147 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Library of Medicine. COVID-19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1 NCoV-19) Trial in South African Adults with and without HIV-Infection. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04444674 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Library of Medicine. A Study of a Candidate COVID-19 Vaccine (COV001). 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04324606 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Library of Medicine. An Open Study of the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of “Gam-COVID-Vac Lyo” Vaccine Against COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04437875 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology. An Open Study of the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of the Drug “Gam-COVID-Vac” Vaccine against COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.smartpatients.com/trials/NCT04437875 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Coughlan, L. Factors Which Contribute to the Immunogenicity of Non-Replicating Adenoviral Vectored Vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumon, H.; Ariyoshi, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Sadahira, T.; Araki, M.; Ebara, S.; Yanai, H.; Watanabe, M.; Nasu, Y. Adenovirus Vector Carrying REIC/DKK-3 Gene: Neoadjuvant Intraprostatic Injection for High-Risk Localized Prostate Cancer Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016, 23, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, Y.; Ohe, Y.; Kuribayashi, K.; Nakano, T.; Okada, M.; Toyooka, S.; Kumon, H.; Nakanishi, Y. P2.06-11 A Phase I/II Study of Intrapleural Ad-SGE-REIC Administration in Patients with Refractory Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, S746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, P.R.; Orringer, D.A.; Sagher, O.; Heth, J.; Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Mammoser, A.G.; Junck, L.; Leung, D.; Umemura, Y.; Lawrence, T.S.; et al. First-in-Human Phase I Trial of the Combination of Two Adenoviral Vectors Expressing HSV1-TK and FLT3L for the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Resectable Malignant Glioma: Initial Results from the Therapeutic Reprogramming of the Brain Immune System. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Weng, D.; Lu, S.; Lin, D.; Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Lv, J.; Li, H.; Lv, F.; Xi, L.; et al. Double-Dose Adenovirus-Mediated Adjuvant Gene Therapy Improves Liver Transplantation Outcomes in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieran, M.W.; Goumnerova, L.; Manley, P.; Chi, S.N.; Marcus, K.J.; Manzanera, A.G.; Polanco, M.L.S.; Guzik, B.W.; Aguilar-Cordova, E.; Diaz-Montero, C.M.; et al. Phase I Study of Gene-Mediated Cytotoxic Immunotherapy with AdV-Tk as Adjuvant to Surgery and Radiation for Pediatric Malignant Glioma and Recurrent Ependymoma. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, T.E.; Rosenthal, E.L.; Parker, W.B.; Sorscher, E.J. Intratumoral Generation of 2-fluoroadenine to Treat Solid Malignancies of the Head and Neck. Head Neck 2019, 41, 1979–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, N.D.; Boorjian, S.A.; Canter, D.J.; Ogan, K.; Karsh, L.I.; Downs, T.M.; Gomella, L.G.; Kamat, A.M.; Lotan, Y.; Svatek, R.S.; et al. Intravesical RAd–IFNα/Syn3 for Patients with High-Grade, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin–Refractory or Relapsed Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Phase II Randomized Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3410–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, D.H.; Recio, A.; Haas, A.R.; Vachani, A.; Katz, S.I.; Gillespie, C.T.; Cheng, G.; Sun, J.; Moon, E.; Pereira, L.; et al. A Phase I Trial of Repeated Intrapleural Adenoviral-Mediated Interferon-β Gene Transfer for Mesothelioma and Metastatic Pleural Effusions. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocca, E.A.; Yu, J.S.; Lukas, R.V.; Solomon, I.H.; Ligon, K.L.; Nakashima, H.; Triggs, D.A.; Reardon, D.A.; Wen, P.; Stopa, B.M.; et al. Regulatable Interleukin-12 Gene Therapy in Patients with Recurrent High-Grade Glioma: Results of a Phase 1 Trial. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, R.E.; Runnebaum, I.B.; Karlan, B.Y.; Horowitz, J.A.; Shahin, M.; Buekers, T.; Petrauskas, S.; Kreienberg, R.; Slamon, D.; Pegram, M. A Phase I/II Trial of RAd/P53 (SCH 58500) Gene Replacement in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002, 9, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, G.H.; Moon, J.; LeBlanc, M.; Lonardo, F.; Urba, S.; Kim, H.; Hanna, E.; Tsue, T.; Valentino, J.; Ensley, J.; et al. A Phase 2 Trial of Surgery with Perioperative INGN 201 (Ad5CMV-P53) Gene Therapy Followed by Chemoradiotherapy for Advanced, Resectable Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity, Oropharynx, Hypopharynx, and Larynx: Report of the Southwest Oncology Group. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2009, 135, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.M.; Singh, G.; Lee, J.Y.; Dehghan, S.; Rajaiya, J.; Liu, E.B.; Yousuf, M.A.; Betensky, R.A.; Jones, M.S.; Dyer, D.W.; et al. Molecular Evolution of Human Adenoviruses. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAdV Working Group. Available online: http://hadvwg.gmu.edu. (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- San Martín, C. Latest Insights on Adenovirus Structure and Assembly. Viruses 2012, 4, 847–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.C. Adenoviruses: Update on Structure and Function. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.T.; Greenshields-Watson, A.; Coughlan, L.; Davies, J.A.; Uusi-Kerttula, H.; Cole, D.K.; Rizkallah, P.J.; Parker, A.L. Diversity within the Adenovirus Fiber Knob Hypervariable Loops Influences Primary Receptor Interactions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loustalot, F.; Kremer, E.J.; Salinas, S. The Intracellular Domain of the Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor Differentially Influences Adenovirus Entry. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 9417–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, S.; Sakurai, F.; Kawabata, K.; Okada, N.; Fujita, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Hayakawa, T.; Mizuguchi, H. Interaction of Penton Base Arg-Gly-Asp Motifs with Integrins Is Crucial for Adenovirus Serotype 35 Vector Transduction in Human Hematopoietic Cells. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunze, S.; Engelke, M.F.; Wang, I.-H.; Puntener, D.; Boucke, K.; Schleich, S.; Way, M.; Schoenenberger, P.; Burckhardt, C.J.; Greber, U.F. Kinesin-1-Mediated Capsid Disassembly and Disruption of the Nuclear Pore Complex Promote Virus Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricobaraza, A.; Gonzalez-Aparicio, M.; Mora-Jimenez, L.; Lumbreras, S.; Hernandez-Alcoceba, R. High-Capacity Adenoviral Vectors: Expanding the Scope of Gene Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Ghimire, P.; Dhamoon, A. The Repertoire of Adenovirus in Human Disease: The Innocuous to the Deadly. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Bishop, E.S.; Zhang, R.; Yu, X.; Farina, E.M.; Yan, S.; Zhao, C.; Zeng, Z.; Shu, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Delivery: Potential Applications for Gene and Cell-Based Therapies in the New Era of Personalized Medicine. Genes Dis. 2017, 4, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, R.G. Adenovirus: The First Effective In Vivo Gene Delivery Vector. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Mese, K.; Bunz, O.; Ehrhardt, A. State-of-the-art Human Adenovirus Vectorology for Therapeutic Approaches. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 3609–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrory, W.J.; Bautista, D.S.; Graham, F.L. A Simple Technique for the Rescue of Early Region I Mutations into Infectious Human Adenovirus Type 5. Virology 1988, 163, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, A.J.; Haddara, W.; Prevec, L.; Graham, F.L. An Efficient and Flexible System for Construction of Adenovirus Vectors with Insertions or Deletions in Early Regions 1 and 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8802–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovesdi, I.; Hedley, S.J. Adenoviral Producer Cells. Viruses 2010, 2, 1681–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.L.; Smiley, J.; Russell, W.C.; Nairn, R. Characteristics of a Human Cell Line Transformed by DNA from Human Adenovirus Type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 1977, 36, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusky, M.; Christ, M.; Rittner, K.; Dieterle, A.; Dreyer, D.; Mourot, B.; Schultz, H.; Stoeckel, F.; Pavirani, A.; Mehtali, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Biology of Recombinant Adenovirus Vectors with E1, E1/E2A, or E1/E4 Deleted. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, P. Vector-Mediated Cancer Gene Therapy: An Overview. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005, 4, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Paolo, N.C.; Miao, E.A.; Iwakura, Y.; Murali-Krishna, K.; Aderem, A.; Flavell, R.A.; Papayannopoulou, T.; Shayakhmetov, D.M. Virus Binding to a Plasma Membrane Receptor Triggers Interleukin-1α-Mediated Proinflammatory Macrophage Response In Vivo. Immunity 2009, 31, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y. Innate Immune Response to Adenoviral Vectors Is Mediated by Both Toll-Like Receptor-Dependent and -Independent Pathways. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3170–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaoka, A.; Wang, Z.; Choi, M.K.; Yanai, H.; Negishi, H.; Ban, T.; Lu, Y.; Miyagishi, M.; Kodama, T.; Honda, K.; et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) Is a Cytosolic DNA Sensor and an Activator of Innate Immune Response. Nature 2007, 448, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruve, D.A.; Pétrilli, V.; Zaiss, A.K.; White, L.R.; Clark, S.A.; Ross, P.J.; Parks, R.J.; Tschopp, J. The Inflammasome Recognizes Cytosolic Microbial and Host DNA and Triggers an Innate Immune Response. Nature 2008, 452, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, L.; Warner, N.; Viani, K.; Nuñez, G. Function of Nod-like Receptors in Microbial Recognition and Host Defense. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the Tumor Immune Microenvironment (TIME) for Effective Therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.R.; Suzuki, M. Immunology of Adenoviral Vectors in Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 15, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wold, W.S.M.; Toth, K. Adenovirus Vectors for Gene Therapy, Vaccination and Cancer Gene Therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2013, 13, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsis, N.; Ertl, H.C.J. Adenoviruses as Vaccine Vectors. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Guroff, M. Replicating and Non-Replicating Viral Vectors for Vaccine Development. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osada, T.; Yang, X.Y.; Hartman, Z.C.; Glass, O.; Hodges, B.L.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Morse, M.A.; Lyerly, H.K.; Amalfitano, A.; Clay, T.M. Optimization of Vaccine Responses with an E1, E2b and E3-Deleted Ad5 Vector Circumvents Pre-Existing Anti-Vector Immunity. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccini, F.; Stribbling, S.; Pollock, E.; Hill, A.V.S.; Redchenko, I. Immunogenicity and Efficacy of the Novel Cancer Vaccine Based on Simian Adenovirus and MVA Vectors Alone and in Combination with PD-1 MAb in a Mouse Model of Prostate Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajgelman, M.C.; Strauss, B.E. Development of an Adenoviral Vector with Robust Expression Driven by P53. Virology 2008, 371, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, A.; Medrano, R.F.; Zanatta, D.B.; Del Valle, P.R.; Merkel, C.A.; de Almeida Salles, T.; Ferrari, D.G.; Furuya, T.K.; Bustos, S.O.; de Freitas Saito, R.; et al. Reestablishment of P53/Arf and Interferon-β Pathways Mediated by a Novel Adenoviral Vector Potentiates Antiviral Response and Immunogenic Cell Death. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, C.A.; da Silva Soares, R.B.; de Carvalho, A.C.V.; Zanatta, D.B.; Bajgelman, M.C.; Fratini, P.; Costanzi-Strauss, E.; Strauss, B.E. Activation of Endogenous P53 by Combined P19Arf Gene Transfer and Nutlin-3 Drug Treatment Modalities in the Murine Cell Lines B16 and C6. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, R.F.V.; Catani, J.P.P.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Tomaz, S.L.; Merkel, C.A.; Costanzi-Strauss, E.; Strauss, B.E. Vaccination Using Melanoma Cells Treated with P19arf and Interferon Beta Gene Transfer in a Mouse Model: A Novel Combination for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catani, J.P.P.; Medrano, R.F.V.; Hunger, A.; Del Valle, P.; Adjemian, S.; Zanatta, D.B.; Kroemer, G.; Costanzi-Strauss, E.; Strauss, B.E. Intratumoral Immunization by P19Arf and Interferon-β Gene Transfer in a Heterotopic Mouse Model of Lung Carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 9, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, A.; Medrano, R.F.; Strauss, B.E. Harnessing Combined P19Arf and Interferon-Beta Gene Transfer as an Inducer of Immunogenic Cell Death and Mediator of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, R.F.V.; Hunger, A.; Catani, J.P.P.; Strauss, B.E. Uncovering the Immunotherapeutic Cycle Initiated by P19Arf and Interferon-β Gene Transfer to Cancer Cells: An Inducer of Immunogenic Cell Death. OncoImmunology 2017, e1329072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.-Q.; Beckham, C.; Brown, J.L.; Lukashev, M.; Barsoum, J. Human and Mouse IFN-β Gene Therapy Exhibits Different Anti-Tumor Mechanisms in Mouse Models. Mol. Ther. 2001, 4, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, O.L.D.; Clavijo-Salomon, M.A.; Cardoso, E.C.; Citrangulo Tortelli Junior, T.; Mendonça, S.A.; Barbuto, J.A.M.; Strauss, B.E. Combined P14ARF and Interferon-β Gene Transfer to the Human Melanoma Cell Line SK-MEL-147 Promotes Oncolysis and Immune Activation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 576658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, L.K.; Shirley, L.A.; Chung, V.M.; Marsh, C.L.; Walker, J.; Coyle, W.; Marx, H.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Lesinski, G.B.; Swanson, B.; et al. Gene-Mediated Cytotoxic Immunotherapy as Adjuvant to Surgery or Chemoradiation for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2015, 64, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.R.; Adler, H.L.; Aguilar-Cordova, E.; Rojas-Martinez, A.; Woo, S.; Timme, T.L.; Wheeler, T.M.; Thompson, T.C.; Scardino, P.T. In Situ Gene Therapy for Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate: A Phase I Clinical Trial. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maatta, A.-M.; Samaranayake, H.; Pikkarainen, J.; Wirth, T.; Yla-Herttuala, S. Adenovirus Mediated Herpes Simplex Virus-Thymidine Kinase/Ganciclovir Gene Therapy for Resectable Malignant Glioma. Curr. Gene Ther. 2009, 9, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chévez-Barrios, P.; Chintagumpala, M.; Mieler, W.; Paysse, E.; Boniuk, M.; Kozinetz, C.; Hurwitz, M.Y.; Hurwitz, R.L. Response of Retinoblastoma with Vitreous Tumor Seeding to Adenovirus-Mediated Delivery of Thymidine Kinase Followed by Ganciclovir. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7927–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterman, D.H.; Recio, A.; Vachani, A.; Sun, J.; Cheung, L.; DeLong, P.; Amin, K.M.; Litzky, L.A.; Wilson, J.M.; Kaiser, L.R.; et al. Long-Term Follow-up of Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Receiving High-Dose Adenovirus Herpes Simplex Thymidine Kinase/Ganciclovir Suicide Gene Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 7444–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Siddiqui, M.R.; Grant, C.; Sanford, T.; Agarwal, P.K. Current Clinical Trials in Non–Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2017, 35, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorjian, S.A.; Alemozaffar, M.; Konety, B.R.; Shore, N.D.; Gomella, L.G.; Kamat, A.M.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Montgomery, J.S.; Lerner, S.P.; Busby, J.E.; et al. Intravesical Nadofaragene Firadenovec Gene Therapy for BCG-Unresponsive Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Single-Arm, Open-Label, Repeat-Dose Clinical Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemunaitis, J. Vaccines in Cancer: GVAX®, a GM-CSF Gene Vaccine. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2005, 4, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhoff, D.; Sluijter, B.J.R.; Hangalapura, B.N.; de Gruijl, T.D. The Dermis as a Portal for Dendritic Cell-Targeted Immunotherapy of Cutaneous Melanoma. In Intradermal Immunization; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Teunissen, M.B.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 351, pp. 181–220. ISBN 978-3-642-23689-1. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, L.H.; Comin-Anduix, B.; Vujanovic, L.; Lee, Y.; Dissette, V.B.; Yang, J.-Q.; Vu, H.T.; Seja, E.; Oseguera, D.K.; Potter, D.M.; et al. Adenovirus MART-1–Engineered Autologous Dendritic Cell Vaccine for Metastatic Melanoma: J. Immunother. 2008, 31, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Lee, M.-H.; Garon, E.; Goldman, J.W.; Salehi-Rad, R.; Baratelli, F.E.; Schaue, D.; Wang, G.; Rosen, F.; Yanagawa, J.; et al. Phase I Trial of Intratumoral Injection of CCL21 Gene–Modified Dendritic Cells in Lung Cancer Elicits Tumor-Specific Immune Responses and CD8 + T-Cell Infiltration. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4556–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappori, A.A.; Soliman, H.; Janssen, W.E.; Antonia, S.J.; Gabrilovich, D.I. INGN-225: A Dendritic Cell-Based P53 Vaccine (Ad.P53-DC) in Small Cell Lung Cancer: Observed Association between Immune Response and Enhanced Chemotherapy Effect. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Huang, X.F.; Hong, B.; Song, X.-T.; Hu, L.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, B.; Ning, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; et al. Efficacy of Intracellular Immune Checkpoint-Silenced DC Vaccine. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-C.; Robbins, P.F. Cancer Immunotherapy Targeting Neoantigens. Semin. Immunol. 2016, 28, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubin, M.M.; Artyomov, M.N.; Mardis, E.R.; Schreiber, R.D. Tumor Neoantigens: Building a Framework for Personalized Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3413–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.K.; Kiertscher, S.M.; Harui, A.; Roth, M.D. Modifying Adenoviral Vectors for Use as Gene-Based Cancer Vaccines. Viral Immunol. 2004, 17, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyvaerts, C.; Breckpot, K. The Journey of in Vivo Virus Engineered Dendritic Cells from Bench to Bedside: A Bumpy Road. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, B. Adenoviral Vector-Based Vaccines and Gene Therapies: Current Status and Future Prospects. In Adenoviruses; Desheva, Y., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78984-990-5. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J.J.; Vasu, C.; Holterman, M.J.; Curiel, D.T.; Pereboev, A. Members of Adenovirus Species B Utilize CD80 and CD86 as Cellular Attachment Receptors. Virus Res. 2006, 122, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggar, A.; Shayakhmetov, D.M.; Lieber, A. CD46 Is a Cellular Receptor for Group B Adenoviruses. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1408–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyle, C.; McCormick, F. Integrin Avβ5 Is a Primary Receptor for Adenovirus in CAR-Negative Cells. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemerow, G.; Flint, J. Lessons Learned from Adenovirus (1970–2019). FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 3395–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bergelson, J.M. Adenovirus Receptors. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 12125–12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, W.; Ehrhardt, A. Expanding the Spectrum of Adenoviral Vectors for Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.L.; Wiethoff, C.M.; Maier, O.; Smith, J.G.; Nemerow, G.R. Functional Genetic and Biophysical Analyses of Membrane Disruption by Human Adenovirus. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2631–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, A.C.; Stehle, T. Human Adenovirus Binding to Host Cell Receptors: A Structural View. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 209, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, O.; Greber, U.F. Adenovirus Endocytosis. J. Gene Med. 2004, 6, S152–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergelson, J.M. Isolation of a Common Receptor for Coxsackie B Viruses and Adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 1997, 275, 1320–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.E.; Edwards, P.; Wickham, T.J.; Castro, M.G.; Lowenstein, P.R. Adenovirus Binding to the Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor or Integrins Is Not Required to Elicit Brain Inflammation but Is Necessary to Transduce Specific Neural Cell Types. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3452–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.-H.; Peng, R.-Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, X.-S. Rejection of Adenovirus Infection Is Independent of Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor Expression in Cisplatin-Resistant Human Lung Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Persson, B.D.; Lenman, A.; Frängsmyr, L.; Schmid, M.; Ahlm, C.; Plückthun, A.; Jenssen, H.; Arnberg, N. Lactoferrin-Hexon Interactions Mediate CAR-Independent Adenovirus Infection of Human Respiratory Cells. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00542-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bots, S.T.F.; Hoeben, R.C. Non-Human Primate-Derived Adenoviruses for Future Use as Oncolytic Agents? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennechet, F.J.D.; Paris, O.; Ouoba, A.R.; Salazar Arenas, S.; Sirima, S.B.; Takoudjou Dzomo, G.R.; Diarra, A.; Traore, I.T.; Kania, D.; Eichholz, K.; et al. A Review of 65 Years of Human Adenovirus Seroprevalence. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-L.; Ke, G.-M.; Chiang, C.-J.; Hwang, K.-P.; Chu, P.-Y.; Lin, J.-H.; Liu, D.-P.; Chen, H.-Y. A Two Decade Survey of Respiratory Adenovirus in Taiwan: The Reemergence of Adenovirus Types 7 and 4. J. Med. Virol. 2004, 73, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumida, S.M.; Truitt, D.M.; Lemckert, A.A.C.; Vogels, R.; Custers, J.H.H.V.; Addo, M.M.; Lockman, S.; Peter, T.; Peyerl, F.W.; Kishko, M.G.; et al. Neutralizing Antibodies to Adenovirus Serotype 5 Vaccine Vectors Are Directed Primarily against the Adenovirus Hexon Protein. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 7179–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiver, J.W.; Emini, E.A. Recent Advances in the Development of HIV-1 Vaccines Using Replication-Incompetent Adenovirus Vectors. Annu. Rev. Med. 2004, 55, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbink, P.; Lemckert, A.A.C.; Ewald, B.A.; Lynch, D.M.; Denholtz, M.; Smits, S.; Holterman, L.; Damen, I.; Vogels, R.; Thorner, A.R.; et al. Comparative Seroprevalence and Immunogenicity of Six Rare Serotype Recombinant Adenovirus Vaccine Vectors from Subgroups B and D. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4654–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.Z.; Lombos, E.; Duvvuri, V.R.; Olsha, R.; Higgins, R.R.; Gubbay, J.B. Temporal Changes in Respiratory Adenovirus Serotypes Circulating in the Greater Toronto Area, Ontario, during December 2008 to April 2010. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, A.; Ebnet, C.; Harste, G.; Pring-Åkerblom, P. Rapid and Quantitative Detection of Human Adenovirus DNA by Real-Time PCR. J. Med. Virol. 2003, 70, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-J.; Jung, H.-D.; Cheong, H.-M.; Kim, K. Molecular Epidemiology of a Post-Influenza Pandemic Outbreak of Acute Respiratory Infections in Korea Caused by Human Adenovirus Type 3: Post-Influenza Pandemic Outbreak of Human Adenovirus Type 3. J. Med. Virol. 2015, 87, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.K.; Chommanard, C.; Lu, X.; Appelgate, D.; Grenz, L.; Schneider, E.; Gerber, S.I.; Erdman, D.D.; Thomas, A. Human Adenovirus Associated with Severe Respiratory Infection, Oregon, USA, 2013–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.; Burman, R.; Crosdale, E.; Cropper, L.; Longson, D.; Enoch, B.E.; Dodd, C.L. A Large Outbreak of Keratoconjunctivitis Due to Adenovirus Type 8. J. Hyg. 1984, 93, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka-Yokogui, K.; Itoh, N.; Usui, N.; Takeuchi, S.; Uchio, E.; Aoki, K.; Usui, M.; Ohno, S. New Genome Type of Adenovirus Serotype 19 Causing Nosocomial Infections of Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis in Japan. J. Med. Virol. 2001, 65, 530–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jernigan, J.A.; Lowry, B.S.; Hayden, F.G.; Kyger, S.A.; Conway, B.P.; Groschel, D.H.M.; Farr, B.M. Adenovirus Type 8 Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis in an Eye Clinic: Risk Factors and Control. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 167, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, B.; Aronson, S.; Sobel, G.; Walker, D. Pharyngoconjunctival Fever; Report of an Epidemic Outbreak. AMA J. Dis. Child. 1956, 92, 596–612. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, D.; Harrower, B.; Lyon, M.; Dick, A. A Primary School Outbreak of Pharyngoconjunctival Fever Caused by Adenovirus Type 3. Commun. Dis. Intell. 2001, 25, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qiu, F.; Shen, X.; Li, G.; Zhao, L.; Chen, C.; Duan, S.; Guo, J.; Zhao, M.; Yan, T.; Qi, J.-J.; et al. Adenovirus Associated with Acute Diarrhea: A Case-Control Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhnoo, I.; Wadell, G.; Svensson, L.; Johansson, M.E. Importance of Enteric Adenoviruses 40 and 41 in Acute Gastroenteritis in Infants and Young Children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 20, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.K.; Clarke, K. Viral Obesity: Fact or Fiction? Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Wei, L.; Lavebratt, C.; Zhang, F.; Gu, H. Serological Data Analyses Show That Adenovirus 36 Infection Is Associated with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis Involving 5739 Subjects: Ad36 Associated with Obesity by Meta-Analysis. Obesity 2014, 22, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, K.L.; Richardson, S.E.; MacGregor, D.; Mahant, S.; Raghuram, K.; Bitnun, A. Adenovirus-Associated Central Nervous System Disease in Children. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, N.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Q.; Xie, Z.; Gao, H.; Duan, Z.; Zhong, L. Epidemiology of Human Adenovirus Infection in Children Hospitalized with Lower Respiratory Tract Infections in Hunan, China: XIE ET AL. J. Med. Virol. 2019, 91, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-Y.; Lee, C.-J.; Lu, C.-Y.; Lee, P.-I.; Shao, P.-L.; Wu, E.-T.; Wang, C.-C.; Tan, B.-F.; Chang, H.-Y.; Hsia, S.-H.; et al. Adenovirus Serotype 3 and 7 Infection with Acute Respiratory Failure in Children in Taiwan, 2010–2011. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, A.M.; Biggs, H.M.; Haynes, A.K.; Chommanard, C.; Lu, X.; Erdman, D.D.; Watson, J.T.; Gerber, S.I. Human Adenovirus Surveillance—United States, 2003–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Hernández, A.M.; Duquesroix, B.; Benítez-del-Castillo, J.M. ADenoVirus Initiative Study in Epidemiology (ADVISE): Resultados de un estudio epidemiológico multicéntrico en España. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2018, 93, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayindou, G.; Ngokana, B.; Sidibé, A.; Moundélé, V.; Koukouikila-Koussounda, F.; Christevy Vouvoungui, J.; Kwedi Nolna, S.; Velavan, T.P.; Ntoumi, F. Molecular Epidemiology and Surveillance of Circulating Rotavirus and Adenovirus in Congolese Children with Gastroenteritis: Rotavirus and Adenovirus in Congolese Children. J. Med. Virol. 2016, 88, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, A.; Joh, J.H.; Hackett, N.R.; Roelvink, P.W.; Bruder, J.T.; Wickham, T.J.; Kovesdi, I.; Crystal, R.G.; Worgall, S. Epitopes Expressed in Different Adenovirus Capsid Proteins Induce Different Levels of Epitope-Specific Immunity. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5523–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.R.; Maxfield, L.F.; Lynch, D.M.; Iampietro, M.J.; Borducchi, E.N.; Barouch, D.H. Adenovirus Serotype 5-Specific Neutralizing Antibodies Target Multiple Hexon Hypervariable Regions. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.G.; Cassany, A.; Gerace, L.; Ralston, R.; Nemerow, G.R. Neutralizing Antibody Blocks Adenovirus Infection by Arresting Microtubule-Dependent Cytoplasmic Transport. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 6492–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.R.; Doszpoly, A.; Turner, G.; Nicklin, S.A.; Baker, A.H. The Relevance of Coagulation Factor X Protection of Adenoviruses in Human Sera. Gene Ther. 2016, 23, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Tian, J.; Smith, J.S.; Conenello, G.M.; Morita, T.; Byrnes, A.P. Coagulation Factor X Shields Adenovirus Type 5 from Attack by Natural Antibodies and Complement. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Sakurai, F.; Iizuka, S.; Hemmi, M.; Wakabayashi, K.; Machitani, M.; Tachibana, M.; Katayama, K.; Kamada, H.; Mizuguchi, H. Antibodies against Adenovirus Fiber and Penton Base Proteins Inhibit Adenovirus Vector-Mediated Transduction in the Liver Following Systemic Administration. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Dong, J.; Wang, C.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Kong, W.; Yu, X. Characteristics of Neutralizing Antibodies to Adenovirus Capsid Proteins in Human and Animal Sera. Virology 2013, 437, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C.; Dayball, K.; Wan, Y.H.; Bramson, J. Detailed Analysis of the CD8+ T-Cell Response Following Adenovirus Vaccination. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 13407–13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olive, M.; Eisenlohr, L.; Flomenberg, N.; Hsu, S.; Flomenberg, P. The Adenovirus Capsid Protein Hexon Contains a Highly Conserved Human CD4 + T-Cell Epitope. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002, 13, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.D.; Yamashina, S.; Froh, M.; Rusyn, I.; Thurman, R.G. Adenoviral Gene Delivery Can Inactivate Kupffer Cells: Role of Oxidants in NF-κB Activation and Cytokine Production. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 69, 622–630. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, R.; Chen, Y.C.; Weaver, A.E.; Barry, A.M. Advances and Future Challenges in Adenoviral Vector Pharmacology and Targeting. Curr. Gene Ther. 2011, 11, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.K.; Herbert, C.W.; Hale, S.J.; Hale, A.B.; Mautner, V.; Harkins, R.; Hermiston, T.; Ulbrich, K.; Fisher, K.D.; Seymour, L.W. Extended Plasma Circulation Time and Decreased Toxicity of Polymer-Coated Adenovirus. Gene Ther. 2004, 11, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D.; Tubb, J.; Ferguson, D.; Scaria, A.; Lieber, A.; Wilson, C.; Perkins, J.; Kay, M.A. Strain Related Variations in Adenovirally Mediated Transgene Expression from Mouse Hepatocytes in Vivo: Comparisons between Immunocompetent and Immunodeficient Inbred Strains. Gene Ther. 1995, 2, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Jooss, K.U.; Su, Q.; Ertl, H.C.; Wilson, J.M. Immune Responses to Viral Antigens versus Transgene Product in the Elimination of Recombinant Adenovirus-Infected Hepatocytes in Vivo. Gene Ther. 1996, 3, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Kovesdi, I.; Bruder, J.T. Effective Repeat Administration with Adenovirus Vectors to the Muscle. Gene Ther. 2000, 7, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, P.J.; Ørskov, C.; Thomsen, A.R.; Christensen, J.P. Quality of the Transgene-Specific CD8 + T Cell Response Induced by Adenoviral Vector Immunization Is Critically Influenced by Virus Dose and Route of Vaccination. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 4431–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Ochoa, L.; Madrid-Marina, V.; Gutiérrez-López, A. Evaluation of Adverse Events in Dogs with Adenoviral Therapy by Intralymphonodal Administration in Canine Spontaneous Multicentric Lymphosarcoma. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Nagasato, M.; Yoshida, T.; Aoki, K. Recent Advances in Genetic Modification of Adenovirus Vectors for Cancer Treatment. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, M.S.; Curiel, D.T. Adenovirus Strategies for Tissue-Specific Targeting. In Advances in Cancer Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 115, pp. 39–67. ISBN 978-0-12-398342-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev, I.; Krasnykh, V.; Miller, C.R.; Wang, M.; Kashentseva, E.; Mikheeva, G.; Belousova, N.; Curiel, D.T. An Adenovirus Vector with Genetically Modified Fibers Demonstrates Expanded Tropism via Utilization of a Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor-Independent Cell Entry Mechanism. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 9706–9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, T.J.; Roelvink, P.W.; Brough, D.E.; Kovesdi, I. Adenovirus Targeted to Heparan-Containing Receptors Increases Its Gene Delivery Efficiency to Multiple Cell Types. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 1570–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackhall, F.H.; Merry, C.L.R.; Davies, E.J.; Jayson, G.C. Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans and Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, T.J.; Segal, D.M.; Roelvink, P.W.; Carrion, M.E.; Lizonova, A.; Lee, G.M.; Kovesdi, I. Targeted Adenovirus Gene Transfer to Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells by Using Bispecific Antibodies. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 6831–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Nishimoto, T.; Hatanaka, K.; Ohnami, S.; Asaka, M.; Douglas, J.T.; Curiel, D.T.; Yoshida, T.; Aoki, K. Direct Selection of Targeted Adenovirus Vectors by Random Peptide Display on the Fiber Knob. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Sadata, A.; Zhang, W.; Saito, K.; Shinoura, N.; Hamada, H. Generation of Fiber-Mutant Recombinant Adenoviruses for Gene Therapy of Malignant Glioma. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998, 9, 2503–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnykh, V.; Dmitriev, I.; Mikheeva, G.; Miller, C.R.; Belousova, N.; Curiel, D.T. Characterization of an Adenovirus Vector Containing a Heterologous Peptide Epitope in the HI Loop of the Fiber Knob. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklin, S.A.; Von Seggern, D.J.; Work, L.M.; Pek, D.C.K.; Dominiczak, A.F.; Nemerow, G.R.; Baker, A.H. Ablating Adenovirus Type 5 Fiber–CAR Binding and HI Loop Insertion of the SIGYPLP Peptide Generate an Endothelial Cell-Selective Adenovirus. Mol. Ther. 2001, 4, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklin, S.A.; White, S.J.; Nicol, C.G.; Von Seggern, D.J.; Baker, A.H. In Vitro Andin Vivo Characterisation of Endothelial Cell Selective Adenoviral Vectors. J. Gene Med. 2004, 6, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joung, I.; Harber, G.; Gerecke, K.M.; Carroll, S.L.; Collawn, J.F.; Engler, J.A. Improved Gene Delivery into Neuroglial Cells Using a Fiber-Modified Adenovirus Vector. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 328, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, Y.; Yamasaki, S.; Davydova, J.; Brown, E.; Aoki, K.; Vickers, S.; Yamamoto, M. Infectivity-Selective Oncolytic Adenovirus Developed by High-Throughput Screening of Adenovirus-Formatted Library. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, O.J.; Kaul, F.; Weitzman, M.D.; Pasqualini, R.; Arap, W.; Kleinschmidt, J.A.; Trepel, M. Random Peptide Libraries Displayed on Adeno-Associated Virus to Select for Targeted Gene Therapy Vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, N.R.; Fan, F. Adenovirus Infection Induces Microglial Activation: Involvement of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways. Brain Res. 2002, 948, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbles, L.A.; Spurrell, J.C.L.; Bowen, G.P.; Liu, Q.; Lam, M.; Zaiss, A.K.; Robbins, S.M.; Hollenberg, M.D.; Wickham, T.J.; Muruve, D.A. Activation of P38 and ERK Signaling during Adenovirus Vector Cell Entry Lead to Expression of the C-X-C Chemokine IP-10. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Stupack, D.; Bokoch, G.M.; Nemerow, G.R. Adenovirus Endocytosis Requires Actin Cytoskeleton Reorganization Mediated by Rho Family GTPases. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8806–8812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, T.J.; Mathias, P.; Cheresh, D.A.; Nemerow, G.R. Integrins Avβ3 and Avβ5 Promote Adenovirus Internalization but Not Virus Attachment. Cell 1993, 73, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranki, T.; Hemminki, A. Serotype Chimeric Human Adenoviruses for Cancer GeneTherapy. Viruses 2010, 2, 2196–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, E.; Havenga, M.J.; Ophorst, O.; de Leeuw, B.; Gijsbers, L.; Gillissen, G.; Hoeben, R.C.; ter Horst, M.; Nanda, D.; Dirven, C.; et al. Human Adenovirus Type 35 Vector for Gene Therapy of Brain Cancer: Improved Transduction and Bypass of Pre-Existing Anti-Vector Immunity in Cancer Patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, A.; Mikheeva, G.V.; Krasnykh, V.; Coolidge, C.J.; Lam, J.T.; Mahasreshti, P.J.; Shannon, D.B.; Barker, S.D. Targeting Adenovirus to the Serotype 3 Receptor Increases Gene Transfer Efficiency to Ovarian Cancer Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkioja, M.; Kanerva, A.; Salo, J.; Kangasniemi, L.; Eriksson, M.; Raki, M.; Ranki, T.; Hakkarainen, T.; Hemminki, A. Noninvasive Imaging for Evaluation of the Systemic Delivery of Capsid-Modified Adenoviruses in an Orthotopic Model of Advanced Lung Cancer. Cancer 2006, 107, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, I.; Denby, L.; Pesonen, S.; Cerullo, V.; Bauerschmitz, G.J.; Guse, K.; Rajecki, M.; Dias, J.D.; Taari, K.; Kanerva, A.; et al. Serotype Chimeric and Fiber-Mutated Adenovirus Ad5/19p-HIT for Targeting Renal Cancer and Untargeting the Liver. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009, 20, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.T.; Davies, J.A.; Bates, E.A.; Moses, E.; Mundy, R.M.; Marlow, G.; Cole, D.K.; Bliss, C.M.; Rizkallah, P.J.; Parker, A.L. The Fiber Knob Protein of Human Adenovirus Type 49 Mediates Highly Efficient and Promiscuous Infection of Cancer Cell Lines Using a Novel Cell Entry Mechanism. J. Virol. 2020, 95, e01849-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Jin, C.; Ramachandran, M.; Xu, J.; Nilsson, B.; Korsgren, O.; Le Blanc, K.; Uhrbom, L.; Forsberg-Nilsson, K.; Westermark, B.; et al. Adenovirus Serotype 5 Vectors with Tat-PTD Modified Hexon and Serotype 35 Fiber Show Greatly Enhanced Transduction Capacity of Primary Cell Cultures. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, T.; Harashima, H.; Kiwada, H. Liposome Clearance. Biosci. Rep. 2002, 22, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kostarelos, K. Designer Adenoviruses for Nanomedicine and Nanodiagnostics. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.D.; Green, N.K.; Hale, A.; Subr, V.; Ulbrich, K.; Seymour, L.W. Passive Tumour Targeting of Polymer-Coated Adenovirus for Cancer Gene Therapy. J. Drug Target. 2007, 15, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreppel, F.; Kochanek, S. Modification of Adenovirus Gene Transfer Vectors With Synthetic Polymers: A Scientific Review and Technical Guide. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.M.; Chess, R.B. Effect of Pegylation on Pharmaceuticals. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eto, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Mukai, Y.; Okada, N.; Nakagawa, S. Development of PEGylated Adenovirus Vector with Targeting Ligand. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 354, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, F.; Shahbazi, M.-A.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Mäkilä, E.; Salonen, J.; Hirvonen, J.T.; Santos, H.A. Multistaged Nanovaccines Based on Porous Silicon@Acetalated Dextran@Cancer Cell Membrane for Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qin, J.; Wang, J. Cell Membrane-Based Nanoparticles: A New Biomimetic Platform for Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Shi, K.; Jia, Y.; Hao, Y.; Peng, J.; Qian, Z. Advanced Biomaterials for Cancer Immunotherapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkar, S.P.; Restifo, N.P. Cellular Constituents of Immune Escape within the Tumor Microenvironment: Figure 1. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3125–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaud, C.; John, L.B.; Westwood, J.A.; Darcy, P.K.; Kershaw, M.H. Immune Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment for Enhancing Cancer Immunotherapy. OncoImmunology 2013, 2, e25961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Holay, M.; Park, J.H.; Fang, R.H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Nanoparticle Delivery of Immunostimulatory Agents for Cancer Immunotherapy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 7826–7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.H.; Hu, C.-M.J.; Luk, B.T.; Gao, W.; Copp, J.A.; Tai, Y.; O’Connor, D.E.; Zhang, L. Cancer Cell Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles for Anticancer Vaccination and Drug Delivery. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 2181–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, F.; Fusciello, M.; Groeneveldt, C.; Capasso, C.; Chiaro, J.; Feola, S.; Liu, Z.; Mäkilä, E.M.; Salonen, J.J.; Hirvonen, J.T.; et al. Biohybrid Vaccines for Improved Treatment of Aggressive Melanoma with Checkpoint Inhibitor. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6477–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, A.V.; Fang, R.H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wei, X.; Yu, C.L.; Gao, J.; Luk, B.T.; Dehaini, D.; Gao, W.; et al. Nanoparticulate Delivery of Cancer Cell Membrane Elicits Multiantigenic Antitumor Immunity. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusciello, M.; Fontana, F.; Tähtinen, S.; Capasso, C.; Feola, S.; Martins, B.; Chiaro, J.; Peltonen, K.; Ylösmäki, L.; Ylösmäki, E.; et al. Artificially Cloaked Viral Nanovaccine for Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Erp, E.A.; Kaliberova, L.N.; Kaliberov, S.A.; Curiel, D.T. Retargeted Oncolytic Adenovirus Displaying a Single Variable Domain of Camelid Heavy-Chain-Only Antibody in a Fiber Protein. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2015, 2, 15001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; O’Bryan, S.M.; Rivera, A.A.; Curiel, D.T.; Mathis, J.M. CXCL12 Retargeting of an Adenovirus Vector to Cancer Cells Using a Bispecific Adapter. Oncolytic Virother. 2016, 5, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, B.; Mahalingam, M. The CXCR4/CXCL12 Axis in Cutaneous Malignancies with an Emphasis on Melanoma. Histol. Histopathol. 2014, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ni, C.; Chen, W.; Wu, P.; Wang, Z.; Yin, J.; Huang, J.; Qiu, F. Expression of CXCR4 and Breast Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Ernst, P.; Honegger, A.; Suomalainen, M.; Zimmermann, M.; Braun, L.; Stauffer, S.; Thom, C.; Dreier, B.; Eibauer, M.; et al. Adenoviral Vector with Shield and Adapter Increases Tumor Specificity and Escapes Liver and Immune Control. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpp, M.T.; Binz, H.K.; Amstutz, P. DARPins: A New Generation of Protein Therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreier, B.; Honegger, A.; Hess, C.; Nagy-Davidescu, G.; Mittl, P.R.E.; Grutter, M.G.; Belousova, N.; Mikheeva, G.; Krasnykh, V.; Pluckthun, A. Development of a Generic Adenovirus Delivery System Based on Structure-Guided Design of Bispecific Trimeric DARPin Adapters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E869–E877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einfeld, D.A.; Schroeder, R.; Roelvink, P.W.; Lizonova, A.; King, C.R.; Kovesdi, I.; Wickham, T.J. Reducing the Native Tropism of Adenovirus Vectors Requires Removal of Both CAR and Integrin Interactions. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 11284–11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, N.; Mizuguchi, H.; Sakurai, F.; Yamaguchi, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Hayakawa, T. Reduction of Natural Adenovirus Tropism to Mouse Liverby Fiber-Shaft Exchange in Combination with Both CAR- Andαv Integrin-BindingAblation. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 13062–13072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.-L.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ruan, G.-X.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Mizuguchi, H.; Mukai, Y.; Okada, N.; Gao, J.-Q.; Nakagawa, S. Optimization and Internalization Mechanisms of PEGylated Adenovirus Vector with Targeting Peptide for Cancer Gene Therapy. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2402–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]