Simple Summary

This scoping review provides an overview of the few observational studies that have investigated potential risk factors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in infants. It summarises some well-established associations in the literature, such as maternal exposure to pesticides and high birth weight, and outlines suggestive associations, such as heavy parental smoking, parental use of multiple medications, and maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy, that merit further research. The results of this review highlight the lack of research on infant acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, which contrasts with the large number of epidemiological studies investigating risk factors in childhood.

Abstract

Objective: Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most frequent childhood cancer. Infant ALL (<1 year) is rare, but it captures a lot of interest due to its poor prognosis, especially in patients harbouring KMT2A rearrangements, which have been demonstrated to arise prenatally. However, epidemiological studies aimed at identifying specific risk factors in such cases are scarce, mainly due to sample-size limitations. We conducted a scoping review to elucidate the prenatal or perinatal factors associated with infant ALL. Methods: Original articles, letters, or conference abstracts published up to June 2022 were identified using the PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases, and 33 observational studies were selected. Results: The study reveals several well-established associations across the literature, such as maternal exposure to pesticides and high birth weight, and outlines suggestive associations, such as parental heavy smoking, parental use of several medications (e.g., dipyrone), and maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy. Conclusions: This scoping review summarizes the few observational studies that have analysed the prenatal and perinatal risk factors for ALL in infants diagnosed before the age of 1 year. The results of this review highlight the lack of research into this specific age group, which merits further research.

1. Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer [1]. There are different subtypes of ALL, based on the specific differentiation stage where B or T-cell precursors are stalled, and on the cytogenetic/molecular diagnosis. Overall, lymphoblastic leukaemia accounts for 72% of all leukaemias, with an incidence rate of 31.1 per million person-years (34.5 in boys and 27.6 in girls), and with the highest incidence in the age group 1–4 years (64.7) [2].

Cases in infants aged <1 year are rare, with an incidence of 18.8 per million person years [2], but capture a lot of interest due to the different clinical and biological features in comparison with children aged from 1 to 14 years [3]. First, over 90% of cases are B-ALL, harbouring translocations of the histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A) gene formerly known as mixed lineage leukaemia gene (MLL) rearrangements [4]. Second, while childhood ALL shows a 5-year overall survival rate excessing 90%, infant cases associated with KMT2A rearrangements (KMT2Ar) have a very poor prognosis, with 5-year survival <30% [5]. In addition, it is hypothesized that most childhood leukaemias are caused first by an in utero genetic alteration, which is followed by further postnatal alterations [6]. However, studies in monozygotic twins and archived blood spots, together with the short latency between birth and diagnosis, indicate that a single prenatal hit may be sufficient to cause infant ALL [7]. Finally, while immune-related factors have been linked to childhood leukaemia [7,8], very little is known about the etiological drivers in infant ALL. Altogether, these observations suggest that infant ALL may represent a distinct entity with specific etiological factors.

A wide range of epidemiological studies have explored environmental exposures associated with the subsequent risk of ALL in childhood. To date, the most well-stablished risk factors include low doses of ionizing radiation in early childhood and maternal exposures to general pesticide, as recently pointed out in an umbrella review [9]. However, most of the studies have presented results according to the type and window of exposure (prenatal, perinatal, or during childhood), but few have thoroughly assessed the etiologic heterogeneity of childhood ALL by specific subtypes [10]. Particularly in infant ALL, studies aimed at identifying unique risk factor profiles are scarce, largely due to the sample size limitations. Herein, we conducted a scoping review to elucidate the association between prenatal or perinatal factors and infant ALL.

2. Methods

Original articles, letters, or conference abstracts published up to June 2022 were identified using the PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases. The search strategy is detailed in the Supplementary Materials, Table S1. In addition to the database searches, we manually reviewed the references of selected articles to identify relevant studies that might have been missed.

After duplicate removal, all retrieved articles underwent an initial level of title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening of eligible abstracts. Only articles written in English or Spanish were considered, and authors were not contacted for additional information. The inclusion criteria were: (i) cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies; (ii) studies that reported the associations between prenatal exposures/perinatal features and subsequent risk of infant ALL (<1 year); and (iii) studies reporting relative risk estimation [e.g., hazard ratio (HR), risk ratio (RR), or odds ratio (OR)] with the corresponding measure of variability [95% confidence intervals (CI) or p value]. The following data were extracted from the selected studies: name of the first author, year of publication, country, study name and design, sample size, exposure assessment, main study findings, and covariates for adjustment.

This review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [11] The protocol has not been registered.

3. Results

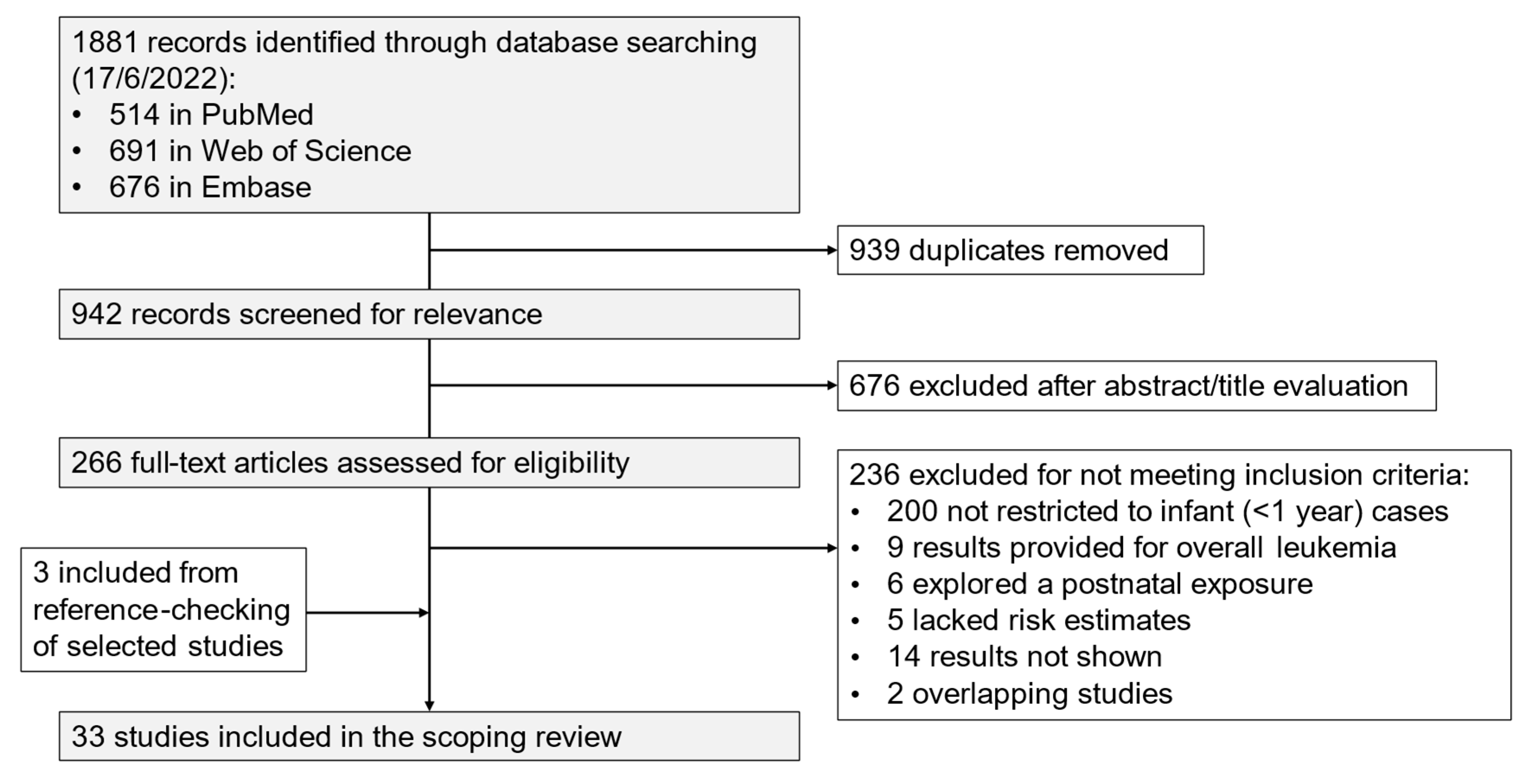

The initial number of identified studies was 1881; finally, 33 observational studies (32 case-control studies and 1 cohort study) were selected, after duplicates had been removed and publications excluded that did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). In addition, among the studies that did not present specific results for infant ALL cases (<1 year), four analysed infant cases with less restrictive definitions (up to 24, 21, or 18 months), and 17 provided stratified results for cases diagnosed <24 or <18 months (Supplementary Material, List S1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

The main characteristics and findings of these studies are shown in Table 1. Studies from the Childhood Oncology Group (COG) [12], (n = 11), from the Childhood Leukaemia International Consortium (CLIC) [13], (n = 7), and from a multi-institutional study of infant leukaemia in Brazil [14], (n = 4), accounted for more than 60% of the studies. The former, the National Cancer Institute supported clinical trials group, is the largest organization worldwide devoted to childhood cancer research, and has conducted numerous studies, including treating ALL cases in its institutions throughout the USA and Canada. In turn, CLIC is a multinational collaboration that pools data from case-control studies on childhood leukaemia from across Europe, North America, and Australia. The latter is a collaborative study on acute infant leukaemia, supported by a network of medical centres located in 10 different Brazilian states. The rest of the studies included in this scoping review were mostly conducted in the USA or the Nordic countries.

Table 1.

Summary of selected studies on infants diagnosed with ALL prior to 1 year of age.

Most of the studies did not specify the cell lineage of ALL (n = 24). However, eight studies presented specific results according to the B-cell or T-cell lineage. In addition, 12 studies presented data on KMT2Ar.

On the other hand, the class of examined exposures were very heterogeneous, mostly focused on maternal exposures during pregnancy but also including parental or birth characteristics. The following sections summarize the study findings according to the type of exposure.

3.1. Dietary Factors

In 1994, researchers from the COG hypothesized that exposure to DNA topoisomerase-II (DNAt2) inhibitors might be associated with de novo leukaemia among infants, based on the increased risk of secondary leukaemia in cancer patients with KMT2Ar treated with such inhibitors [48]. The most abundant environmental source of such compounds is diet; Ross et al. [15] preliminarily assessed such association within the COG study and the results, based on few cases/controls (n = 54/84), revealed no associations between a higher index of combined exposure to dietary DNAt2 inhibitors and infant ALL, but pointed out an inverse association with fish consumption and milk. Likewise, and using a larger subset of the COG, Spector et al. [16] reported, ten years later, that there was no association between a more complete index and infant ALL, regardless of KMT2A status. Surprisingly, the authors found an inverse association with the Vegetable and Fruit Index (VF+) (more like the index used in the previous study and characterized by high consumption of fruit and vegetables). More recently, a CLIC pooled analyses of eight case-control studies that explored the potential role of maternal coffee and tea consumption [17]. Despite the plausibility of an adverse effect from caffeine (i.e., it is an inhibitor of DNAt2 and of some tumour suppressor genes, such as ATM and TP53), no clear association with infant ALL was reported.

3.2. Pesticides and Other Toxic Chemicals

The reports concluding that pesticides could be risk factors for childhood leukaemia first appeared more than 25 years ago [49]. Since then, different studies have explored such associations, yielding inconsistent results mainly due to heterogeneous exposure assessment and multiple statistical testing, as recently pointed out in a systematic review and meta-analysis [50]. Based on 55 studies from over 30 countries, assessing >200 different exposures to pesticides, the authors concluded that pesticide exposure mainly during pregnancy increases the risk of ALL, particularly among infants. Mechanistic studies further support this association in infants, suggesting that transplacental exposure to mosquitocidals may cause KMT2A gene fusions [51].

In this review, four studies examining prenatal pesticide exposure and development of infant ALL were identified. Results from a Brazilian hospital-based case-control study revealed that children whose mothers were exposed to pesticides 3 months before conception were at least twice as likely to be diagnosed with ALL in the first year of life compared to those whose mothers were not exposed (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.1; 3.9) [19]. Results by specific component yielded statistically significant associations for Permethrin, Imiprothrin, Esbiothrin, and solvents. Bailey et al. [20,21] explored data from the CLIC study regarding maternal home exposures or parental occupational exposures. In the former, the authors pooled individual-level data from 12 case-control studies and found a strong association between maternal home pesticide exposure before conception (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.05; 1.97) or during pregnancy (OR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.5; 2.3) and infant ALL. In the latter, pooled results from 13 case-control studies revealed an association between paternal exposure around conception and overall childhood ALL, yet this association did not remain in the subgroup of cases aged <1 year. Within the COG study, Slater et al. [18] investigated the potential role of several pesticides (i.e., insecticides, moth control, rodenticides, flea or tick control, herbicides, insect repellents, and professional pest exterminations), also yielding null results. It is worth mentioning a case report describing a single case of congenital leukaemia with KMT2Ar from a mother who heavily abused aerosolised Permethrin [52].

Other potential disrupting chemicals, such as from occupational paint exposure or household exposure to paint/stains/lacquers and petroleum products, have been explored [18,22]. Bailey et al. [22] found that home paint exposure shortly before conception, during pregnancy, and/or after birth appeared to increase the risk of childhood ALL, yet no consistent associations were reported for infant cases. In the study of Slater et al. [18], an association between gestational exposure to petroleum products (e.g., gasoline, kerosene, lubricating oils, and spot removers) was found for infant ALL without KMT2Ar (OR: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.0; 4.7), but not for cases of infant ALL with KMT2Ar.

3.3. Outdoor Air Pollution

In 2016, the International Agency of Research on Cancer monograph on air pollution classified its associations with childhood leukaemia as suggestive but inconsistent [53]. Since then, cumulative evidence has further explored such associations, which have been recently synthesized in a dose–response meta-analysis, revealing a potential association between outdoor air pollution and childhood ALL [54]. Studies providing specific results for infant cases, however, are very scarce, with only two USA population-based case-control studies identified in this scoping review. In 2013, Heck et al. [23] reported an almost statistically significant association between average exposure to carbon monoxide during pregnancy (based on the residence of the child at birth) with ALL diagnosed during the first year of life (OR per 1-IQR increase in carbon monoxide: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.99; 1.31). By contrast, Peckham-Gregory et al. [24] did not find an association between maternal residential proximity to major roadways, as a proxy for measuring exposure to traffic-related pollution, and infant ALL.

3.4. Smoking, Alcohol, and Other Drugs

Parental smoking has been suggested as a possible risk factor for childhood cancer, as chemicals in tobacco smoke are carcinogenic and can trigger DNA damage and cross the placenta. Interestingly, De la Chica et al. [55] reported that smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day (cpd) for at least 10 years and during pregnancy was associated with increased chromosome instability in amniocytes, highlighting the particular sensitivity of the 11q23 band containing the KMT2A gene. Many studies have explored such exposures and the subsequent risk of childhood ALL, showing inconsistent results for maternal smoking and positive associations with paternal smoking at multiple time windows [56]. In cases aged <1 year, different studies show evidence that only heavy smoking (maternal and/or paternal) may be associated with ALL [25,26,27,28,33]. In fact, the amount of daily smoked cigarettes shows a statistically significant association with ALL in two studies with the following results: (i) paternal smoking during conception time (2 years before birth) ≥15 cpd was associated with a risk of infant ALL (OR: 5.7, 95% CI: 1.5; 22.1) and this association was not observed in other age groups [28], and (ii) maternal daily consumption of 20 or more cpd during pregnancy (second and third trimester and breastfeeding) showed a statistically significant fivefold higher association (analysis available in infants <2 years) [28], though no association was observed when the cut-off was established at ≥10 cpd [25]. Evidence on alcohol consumption is much scarcer; to date, only two studies have evaluated the association between maternal alcohol consumption and infant ALL, reporting null results [26,29]. One of these also explored illicit drug use (i.e., marijuana, cocaine, and heroine), although no associations were observed [26].

3.5. Medication Use

Parental medication use, in association with the risk of cancer developing in offspring, has been widely studied [8]. However, only two studies have analysed the association between parental medication use during preconception and pregnancy and infant ALL. Within the COG study, Wen et al. [30] evaluated an extensive list of medications and, while not reporting statistically significant associations for cases aged <1 year, the results suggest noteworthy associations with parental use of mind-altering drugs or maternal use of antihistamines or allergy remedies. Couto et al. [31], in particular, assessed maternal use of analgesics during pregnancy in Brazil, and showed a positive association between the use of dipyrone during preconception, the first trimester of pregnancy and breastfeeding, and infant ALL, with the association being stronger in cases with KMT2Ar; the association between maternal use of dipyrone and KMT2Ar leukaemia cases was observed in all time windows [31]. Otherwise, inverse associations were reported between maternal use of acetaminophen, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy, and overall infant ALL.

3.6. Infections

There are currently two key hypotheses, first formulated in 1988, regarding infections and the development of childhood ALL: the ‘population mixing hypothesis’ of Kinlen [8], and the ‘delayed infection’ of Greaves [57]. Although the mechanisms differ, both authors suggest that ALL may be an abnormal response to one or more common infections acquired through personal contact. Since then, a large body of evidence has examined the association between infections and childhood ALL, reporting inconclusive findings for childhood infections [58], and positive associations with maternal infections [59,60]. However, this scoping review only identified one study providing results for infant cases [32]. Specifically, the study shows no statistically significant relationship between maternal Epstein–Barr virus and the risk of ALL in offspring, using two specific antigens (early antigen IgG and ZEBRA IgG).

3.7. Parental Characteristics and Reproductive History

Five studies have explored the association between parental or maternal age and infant ALL, yielding mostly null results [33,37,38,43,44]. Only in the study of Marcotte et al. [43] was an association found between paternal age <20 years and an increased risk of infant ALL (OR: 3.7, 95% CI: 1.6; 8.4). Four studies examined the potential role of parity features (e.g., history of foetal loss, etc.) or infertility (e.g., time to index pregnancy, latent class infertility, use of infertility-related drugs, etc.), reporting null associations with infant ALL [33,34,37,38]. Likewise, two studies have explored the role of maternal diseases during pregnancy and the subsequent risk of infant ALL, yielding null results for anaemia [36] and other comorbidities such as endocrine disease or diabetes, among others [33].

3.8. Birth Weight, Foetal Growth, and Other Perinatal Characteristics

High birth weight is among the most well-established risk factor for childhood ALL [61]. The biological mechanism behind this association remains unclear, although some authors suggest that insulin-like growth factors are involved [62]. Within this scoping review, we identified six case-control studies assessing such associations in infant cases. Except for two studies yielding null results [35,37], the remaining consistently reported strong associations between the largest categories of birth weight (i.e., >4000–4500 g [33,34,40] or 90th percentile [41]) and infant ALL. In addition, the study of Roman et al. [41], including 2090 infant ALL cases from three pooled case-control studies, also reported a dose–response relationship (OR per 1 kg increase = 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1; 1.3)). In contrast, foetal growth remains understudied in infant ALL cases, with only one study presenting data by age at diagnosis [42]; specifically, pooled data from 12 case-controls studies reveal that accelerated foetal growth is strongly associated with a risk of childhood ALL. Indeed, this association was observed in children whose birth weight was less than 4000 g, suggesting that accelerated foetal growth is associated with an increased risk of ALL in the absence of a high birth weight. However, no statistically significant associations were reported when restricting analyses to infant cases.

Among other birth features, congenital abnormalities were explored in a COG study including 443 infant ALL cases (excluding Down’s syndrome cases) [39]. Overall, the authors did not find any associations between eight features (cleft lip or palate, spina bifida or another spinal defect, large or multiple birthmarks, and other chromosomal abnormalities such as an unusually small head or microcephaly, rib abnormalities, urogenital abnormalities, or any other birth defect) and infant ALL. Two other studies from the COG assessed birth order, yielding different observations; one reported null findings [34], while the other found an inverse association with ALL, particularly in KMT2Ar cases [37]. Finally, in the study of Cnattingius et al. [33], a range of neonatal features and procedures were assessed, including physiologic jaundice, phototherapy, intrauterine or postpartum asphyxia, and supplementary oxygen, and results report mostly null associations for cases aged <1 year.

3.9. Caesarean Section

Increasing evidence suggests that birth by caesarean delivery affects both short-term and long-term outcomes for the neonate, including immune system development and differential microbiota colonization. Particularly in overall childhood leukaemia, current evidence points to an association between caesarean delivery and a risk of ALL [63]. However, the three studies assessing these associations in infant cases show inconsistent results. Two of these studies confirmed the association in other age groups [45,46]; however, only one of them concludes that there is an increased risk of ALL in children aged <1 year, without being able to conclude definitively whether this risk is due to prelabour or emergency caesarean delivery [47]. It should be noted that this study, unlike the others, clearly specifies which indications were considered when classifying the type of caesarean delivery, suggesting that the reason for caesarean delivery could be the key to this possible association.

4. Discussion

This scoping review provides an overview of the few observational studies examining potential risk factors for infant ALL. It summarizes a few well-established associations from across the literature, such as maternal exposure to pesticides and high birth weight, and outlines suggestive associations, such as parental heavy smoking, parental use of several medications (e.g., dipyrone), and maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy, all of which merit further research.

This study highlights the lack of research into infant ALL, which contrasts with the large number of epidemiological studies exploring the risk factors for childhood ALL. The main reasons for such scarcity are related to sample size constrains in almost all studies. While ALL is the most frequent cancer in children, cases diagnosed prior to 1 year of age are rare, with an estimated incidence of nearly 20 cases per million person-years in Europe [64] Therefore, obtaining a substantial subset of cases that allows stratified analyses by age group is difficult in case-control studies and almost unfeasible in cohort studies. Indeed, most of the included publications in this scoping review arose from the efforts of three projects (i.e., the COG, the CLIC, and the Brazilian multi-institutional study), which gathered data from multiple institutions to overcome such limitations.

During the literature search, we identified several studies with less restrictive definitions of infant cases (i.e., cases diagnosed within 18, 21, or 24 months) (Supplementary Material, List S1). The reason for widening this time window, in some Brazilian studies, was to cope with the frequent delay in the identification of ALL in some areas of Brazil [14]. However, within this scoping review, we decided to keep the strict definition as cases diagnosed during the first year of life, given the distinct biological and clinical behaviour [65]. Indeed, in more than 80% of cases, infant ALL is cytogenetically characterized by balanced chromosomal translocations involving the KMT2A gene at chromosome 11q23; in contrast, those rearrangements occur in ∼5% of overall childhood ALL. Multiple lines of evidence have shown that KMT2A rearrangements are acquired in pre-VDJ hematopoietic precursors in utero and, compared to other oncogenic fusions, initiate a strikingly rapid progression to leukaemia [66]. Given that this type of rearrangement also occurs in therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemias occurring as a complication after cytotoxic and/or radiation for a primary malignancy or autoimmune disease, such as exposure to DNAt2 inhibitors, most of the etiological hypotheses related to infant ALL occurrence are based on maternal exposure to these inhibitors. KMT2Ar has been described as the only genetic insult sufficient for leukemogenesis in infant ALL, in contrast to most childhood leukaemias, which are caused first by an in utero genetic alteration (‘first hit’), followed by further postnatal alterations [67,68,69,70]. Germline genetic susceptibility may also play a role, with several single-nucleotide polymorphisms correlated with ALL being identified in candidate gene or genome-wide association studies [71,72,73,74]. Overall, mechanistic studies exploring the unique molecular–genetic signature of the disease onset at the genome, epigenome, and transcriptome will help to clarify it and drive future epidemiological studies exploring environmental exposures.

Several limitations of the studies included in this scoping review must be considered. First, almost all studies are case-control studies with self-reported information on exposure. The inherent recall bias of this study design, especially regarding exposures that may be perceived harmful, should be kept in mind when interpreting their results. In addition, in most studies, collected data were not sufficiently detailed for assessing differential susceptibilities by time window, length, or magnitude of exposure, which may partly explain inconsistent findings. Moreover, exposures such as drugs, alcohol, or tobacco consumption tend to be frequently underreported, particularly during pregnancy [75]. Regarding pooled case-control studies, combining data from disparate populations may be challenging, particularly when different measurement instruments for exposure or cultural differences and variations in the prevalence of the exposures under study are involved. Therefore, despite efforts to harmonize data, misclassification issues are also expected. In addition, some studies used contextual-level data as a proxy for measuring exposure to air pollution, which unavoidably leads to some measurement error and exposure misclassification. Second, the case-control design may also introduce selection bias, given that the probability of participation in or selection for the study may be different depending on case-control status and the underlying exposures of interest. Third, ALL cytogenetic data (e.g., KMT2Ar status) were missing in the majority of the studies, which may be relevant when assessing etiological hypothesis. Fourth, some studies, particularly those limited to data available in existing medical records, could not adjust for important confounders, and sample size was limited, thus resulting in imprecise estimates of association.

Finally, there are some limitations related to this scoping review. Despite efforts to find all published studies and to search for conference works, findings may be affected by publication bias. In fact, published studies are limited to a few countries, and areas such as non-African or Asian countries are not represented. In addition, heterogeneity in the exposures assessed and the few studies included in each category precluded a deep qualitative summary for each exposure. Nonetheless, this study constitutes the first comprehensive overview of epidemiological studies examining aetiological risk factors for infant ALL. It has allowed us to determine the coverage of the body of literature on this topic and to identify research gaps and future research opportunities, as well as to outline areas where there is room for improvement.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this scoping review reveals an important research gap in the study of potential environmental risk factors involved in the aetiology of infant ALL. Maternal exposure to pesticides and high birth weight are among the most well-established conditions, while the suggestive roles of parental heavy smoking, parental use of several medications (e.g., dipyrone), and maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy merit further research. Given that prenatal or perinatal exposure comprises a small time window, the pivotal factors responsible may be easier to identify than for cancers with a longer latency period. New epidemiological studies should ideally gather information on cytogenetic status, as well as the time window, magnitude, and length of exposure, to counter the inconsistencies which arose in previous studies. Given the low incidence of infant ALL, this seems mostly feasible in collaborative international or pooling projects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers17030370/s1. Supplementary Table S1. Search strategy in (A) PubMed and (B) Web of Science and EMBASE. Supplementary List S1. List of studies that stratify results for <24 or <18 months or that include only infant cases but with less restrictive definitions (up to 24 months, up to 21 months, or up to 18 months).

Author Contributions

A.S.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, and writing-original draft preparation. C.B.: writing—review and editing. O.C.: writing—review and editing. F.S.: supervision and writing—review and editing. R.M.-G.: supervision. M.S.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, ERDF, a way to build Europe [PI 20/00531, PI20/00822, PLE2021-007518]; Asociación Española Contra el Cancer (AECC) [PRYGN211192BUEN]; TRANSCAN AECC and ISCIII [AC 18/000002]; Generalitat de Catalunya with economical support from the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya [2017 SGR288 (GRC), 2021 CSGR 00560 (GRC)]; Fundació Internacional Josep Carreras; Fundación UnoEntreCienmil.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paula Ruiz for their support in the literature-screening process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhakta, N.; Force, L.M.; Allemani, C.; Atun, R.; Bray, F.; Coleman, M.P.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Frazier, A.L.; Robison, L.L.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; et al. Childhood Cancer Burden: A Review of Global Estimates. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e42–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos-Gragera, R.; Galceran, J.; Martos, C.; de Munain, A.L.; Vicente-Raneda, M.; Navarro, C.; Quirós-Garcia, J.R.; Sánchez, M.J.; Ardanaz, E.; Ramos, M.; et al. Incidence and Survival Time Trends for Spanish Children and Adolescents with Leukaemia from 1983 to 2007. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 19, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuan-Pla, A.; Bueno, C.; Prieto, C.; Acha, P.; Stam, R.W.; Marschalek, R.; Menéndez, P. Revisiting the Biology of Infant t(4;11)/MLL-AF4+ B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood 2015, 126, 2676–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.F.; Wiemels, J. Origins of Chromosome Translocations in Childhood Leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Mullighan, C.G. Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2524–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Wilson, C.S.; Harvey, R.C.; Chen, I.M.; Murphy, M.H.; Atlas, S.R.; Bedrick, E.J.; Devidas, M.; Carroll, A.J.; Robinson, B.W.; et al. Gene Expression Profiles Predictive of Outcome and Age in Infant Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2012, 119, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, M. Infection, Immune Responses and the Aetiology of Childhood Leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinlen, L. Evidence for an Infective Cause of Childhood Leukaemia: Comparison of a Scottish New Town with Nuclear Reprocessing Sites in Britain. Lancet 1988, 2, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyije, F.M.; Olsson, A.; Baaken, D.; Erdmann, F.; Stanulla, M.; Wollschläger, D.; Schüz, J. Environmental Risk Factors for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: An Umbrella Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.A.; Yang, J.J.; Hirsch, B.A.; Marcotte, E.L.; Spector, L.G. Is There Etiologic Heterogeneity between Subtypes of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia? A Review of Variation in Risk by Subtype. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.; Krailo, M.; Anderson, J.R.; Reaman, G.H. Progress in Childhood Cancer: 50 Years of Research Collaboration, a Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Semin. Oncol. 2008, 35, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metayer, C.; Milne, E.; Clavel, J.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Petridou, E.; Taylor, M.; Schüz, J.; Spector, L.G.; Dockerty, J.D.; Magnani, C.; et al. The Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013, 37, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo-De-Oliveira, M.S.; Koifman, S.; Araújo, P.I.C.; Alencar, D.M.; Brandalise, S.R.; Guimarães Carvalho, E.; Coser, V.M.; Costa, I.; Córdoba, J.C.; Emerenciano, M.; et al. Infant Acute Leukemia and Maternal Exposures during Pregnancy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 2336–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Potter, J.D.; Reaman, G.H.; Pendergrass, T.W.; Robison, L.L. Maternal Exposure to Potential Inhibitors of DNA Topoisomerase II and Infant Leukemia (United States): A Report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Cancer Causes Control 1996, 7, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, L.G.; Xie, Y.; Robison, L.L.; Heerema, N.A.; Hilden, J.M.; Lange, B.; Felix, C.A.; Davies, S.M.; Slavin, J.; Potter, J.D.; et al. Maternal Diet and Infant Leukemia: The DNA Topoisomerase II Inhibitor Hypothesis: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, E.; Greenop, K.R.; Petridou, E.; Bailey, H.D.; Orsi, L.; Kang, A.Y.; Baka, M.; Bonaventure, A.; Kourti, M.; Metayer, C.; et al. Maternal Consumption of Coffee and Tea during Pregnancy and Risk of Childhood ALL: A Pooled Analysis from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, M.E.; Linabery, A.M.; Spector, L.G.; Johnson, K.J.; Hilden, J.M.; Heerema, N.A.; Robison, L.L.; Ross, J.A. Maternal Exposure to Household Chemicals and Risk of Infant Leukemia: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Causes Control 2011, 22, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ferreira, J.D.; Couto, A.C.; Pombo-de-Oliveira, M.S.; Koifman, S. In Utero Pesticide Exposure and Leukemia in Brazilian Children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bailey, H.D.; Fritschi, L.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Glass, D.C.; Miligi, L.; Dockerty, J.D.; Lightfoot, T.; Clavel, J.; Roman, E.; Spector, L.G.; et al. Parental Occupational Pesticide Exposure and the Risk of Childhood Leukemia in the Offspring: Findings from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 2157–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, H.D.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Metayer, C.; Clavel, J.; Lightfoot, T.; Kaatsch, P.; Roman, E.; Magnani, C.; Spector, L.G.; Th Petridou, E.; et al. Home Pesticide Exposures and Risk of Childhood Leukemia: Findings from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 2644–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, H.D.; Metayer, C.; Milne, E.; Petridou, E.T.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Spector, L.G.; Clavel, J.; Dockerty, J.D.; Zhang, L.; Armstrong, B.K.; et al. Home Paint Exposures and Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Findings from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Cancer Causes Control 2015, 26, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, J.E.; Wu, J.; Lombardi, C.; Qiu, J.; Meyers, T.J.; Wilhelm, M.; Cockburn, M.; Ritz, B. Childhood Cancer and Traffic-Related Air Pollution Exposure in Pregnancy and Early Life. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham-Gregory, E.C.; Ton, M.; Rabin, K.R.; Danysh, H.E.; Scheurer, M.E.; Lupo, P.J. Maternal Residential Proximity to Major Roadways and the Risk of Childhood Acute Leukemia: A Population-Based Case-Control Study in Texas, 1995–2011. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucci, L.; Granath, F.; Cnattingius, S. Maternal Smoking and Childhood Leukemia and Lymphoma Risk among 1,440,542 Swedish Children. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.E.; Linabery, A.M.; Blair, C.K.; Spector, L.G.; Heerema, N.A.; Robison, L.L.; Ross, J.A. Maternal Prenatal Cigarette, Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use and Risk of Infant Leukaemia: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2011, 25, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ferreira, J.; Couto, A.; Pombo-de-Oliveira, M.; Koifman, S. Pregnancy, Maternal Tobacco Smoking, and Early Age Leukemia in Brazil. Front. Oncol. 2012, 2, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, E.; Greenop, K.R.; Scott, R.J.; Bailey, H.D.; Attia, J.; Dalla-Pozza, L.; De Klerk, N.H.; Armstrong, B.K. Parental Prenatal Smoking and Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.D.; Couto, A.C.; Emerenciano, M.; Pombo-De-Oliveira, M.S.; Koifman, S. Maternal Alcohol Consumption during Pregnancy and Early Age Leukemia Risk in Brazil. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 732495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Shu, X.O.; Potter, J.D.; Severson, R.K.; Buckley, J.D.; Reaman, G.H.; Robison, L.L. Parental Medication Use and Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer 2002, 95, 1786–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, A.C.; Ferreira, J.D.; Pombo-De-Oliveira, M.S.; Koifman, S. Pregnancy, Maternal Exposure to Analgesic Medicines, and Leukemia in Brazilian Children below 2 Years of Age. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 24, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.; Bloigu, A.; Ögmundsdottir, H.M.; Marus, A.; Dillner, J.; DePaoli, P.; Gudnadottir, M.; Koskela, P.; Pukkala, E.; Lehtinen, T.; et al. Activation of Maternal Epstein-Barr Virus Infection and Risk of Acute Leukemia in the Offspring. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnattingius, S.; Zack, M.M.; Ekbom, A.; Gunnarskog, J.; Kreuger, A.; Linet, M.; Adami, H.O. Prenatal and Neonatal Risk Factors for Childhood Lymphatic Leukemia. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995, 87, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Potter, J.D.; Shu, X.O.; Reaman, G.H.; Lampkin, B.; Robison, L.L. Evaluating the Relationships among Maternal Reproductive History, Birth Characteristics, and Infant Leukemia: A Report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Ann. Epidemiol. 1997, 7, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalgrim, L.L.; Rostgaard, K.; Hjalgrim, H.; Westergaard, T.; Thomassen, H.; Forestier, E.; Gustafsson, G.; Kristinsson, J.; Melbye, M.; Schmiegelow, K. Birth Weight and Risk for Childhood Leukemia in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.M.; Blair, C.K.; Verneris, M.R.; Neglia, J.P.; Robison, L.L.; Spector, L.G.; Reaman, G.H.; Felix, C.A.; Ross, J.A. Maternal Hemoglobin Concentration during Pregnancy and Risk of Infant Leukaemia: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 1274–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, L.G.; Davies, S.M.; Robison, L.L.; Hilden, J.M.; Roesler, M.; Ross, J.A. Birth Characteristics, Maternal Reproductive History, and the Risk of Infant Leukemia: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puumala, S.E.; Spector, L.G.; Wall, M.M.; Robison, L.L.; Heerema, N.A.; Roesler, M.A.; Ross, J.A. Infant Leukemia and Parental Infertility or Its Treatment: A Children’s Oncology Group report. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnson, K.J.; Roesler, M.A.; Linabery, A.M.; Hilden, J.M.; Davies, S.M.; Ross, J.A. Infant Leukemia and Congenital Abnormalities: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørge, T.; Sørensen, H.T.; Grotmol, T.; Engeland, A.; Stephansson, O.; Gissler, M.; Tretli, S.; Troisi, R. Fetal Growth and Childhood Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Pediatrics 2013, 132, e1265–e1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, E.; Lightfoot, T.; Smith, A.G.; Forman, M.R.; Linet, M.S.; Robison, L.; Simpson, J.; Kaatsch, P.; Grell, K.; Frederiksen, K.; et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia and Birthweight: Insights from a Pooled Analysis of Case-Control Data from Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, E.; Greenop, K.R.; Metayer, C.; Schüz, J.; Petridou, E.; Pombo-De-Oliveira, M.S.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Roman, E.; Dockerty, J.D.; Spector, L.G.; et al. Fetal Growth and Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Findings from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 2968–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, E.L.; Druley, T.E.; Johnson, K.J.; Richardson, M.; von Behren, J.; Mueller, B.A.; Carozza, S.; McLaughlin, C.; Chow, E.J.; Reynolds, P.; et al. Parental Age and Risk of Infant Leukaemia: A Pooled Analysis. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2017, 31, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridou, E.T.; Georgakis, M.K.; Erdmann, F.; Ma, X.; Heck, J.E.; Auvinen, A.; Mueller, B.A.; Spector, L.G.; Roman, E.; Metayer, C.; et al. Advanced Parental Age as Risk Factor for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Results from Studies of the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, E.L.; Thomopoulos, T.P.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Clavel, J.; Petridou, E.T.; Schüz, J.; Ezzat, S.; Dockerty, J.D.; Metayer, C.; Magnani, C.; et al. Caesarean Delivery and Risk of Childhood Leukaemia: A Pooled Analysis from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium (CLIC). Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e176–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wiemels, J.L.; Metayer, C.; Morimoto, L.; Francis, S.S.; Kadan-Lottick, N.; Dewan, A.T.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Cesarean Section and Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in a Population-Based, Record-Linkage Study in California. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, E.L.; Richardson, M.R.; Roesler, M.A.; Spector, L.G. Cesarean Delivery and Risk of Infant Leukemia: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Potter, J.D.; Robison, L.L. Infant Leukemia, Topoisomerase II Inhibitors, and the MLL Gene. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994, 86, 1678–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahm, S.H.; Ward, M.H. Pesticides and Childhood Cancer. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106 (Suppl. 3), 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karalexi, M.A.; Tagkas, C.F.; Markozannes, G.; Tseretopoulou, X.; Hernández, A.F.; Schüz, J.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Petridou, E.T.; Tzoulaki, I.; et al. Exposure to Pesticides and Childhood Leukemia Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 285, 113376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, F.E.; Patheal, S.L.; Biondi, A.; Brandalise, S.; Cabrera, M.E.; Chan, L.C.; Chen, Z.; Cimino, G.; Cordoba, J.C.; Gu, L.J.; et al. Transplacental Chemical Exposure and Risk of Infant Leukemia with MLL Gene Fusion. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2542–2546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borkhardt, A.; Wilda, M.; Fuchs, U.; Gortner, L.; Reiss, I. Congenital Leukaemia after Heavy Abuse of Permethrin during Pregnancy. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003, 88, F436–F437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research and Cancer. Outdoor Air Pollution; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 109. [Google Scholar]

- Filippini, T.; Hatch, E.E.; Rothman, K.J.; Heck, J.E.; Park, A.S.; Crippa, A.; Orsini, N.; Vinceti, M. Association between Outdoor Air Pollution and Childhood Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 46002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Chica, R.A.; Ribas, I.; Giraldo, J.; Egozcue, J.; Fuster, C. Chromosomal Instability in Amniocytes from Fetuses of Mothers Who Smoke. JAMA 2005, 293, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, L.; Gutti, R.K. Tobacco Smoke Exposure and the Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e16454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.F. Speculations on the Cause of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leukemia 1988, 2, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwee, J.; Tait, C.; Sung, L.; Kwong, J.C.; Sutradhar, R.; Pole, J.D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Childhood Infections and the Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.R.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Hirst, J.E.; Bonaventure, A.; Francis, S.S.; Paltiel, O.; Håberg, S.E.; Lemeshow, S.; Olsen, S.; Tikellis, G.; et al. Maternal Infection in Pregnancy and Childhood Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2020, 217, 98–109.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.R.; Yu, Y.; Fang, F.; Gissler, M.; Magnus, P.; László, K.D.; Ward, M.H.; Paltiel, O.; Tikellis, G.; Maule, M.M.; et al. Evaluation of Maternal Infection During Pregnancy and Childhood Leukemia Among Offspring in Denmark. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughey, R.W.; Michels, K.B. Birth Weight and Childhood Leukemia: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Current Evidence. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 2658–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalkidou, A.; Petridou, E.; Papathoma, E.; Salvanos, H.; Chrousos, G.; Trichopoulos, D. Birth Size and Neonatal Levels of Major Components of the IGF System: Implications for Later Risk of Cancer. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 15, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.L.; Gao, Y.Y.; He, W.B.; Gan, T.; Shan, H.Q.; Han, X.M. Cesarean Section and Risk of Childhood Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Colombet, M.; Ries, L.A.G.; Moreno, F.; Dolya, A.; Bray, F.; Hesseling, P.; Shin, H.Y.; Stiller, C.A.; Bouzbid, S.; et al. International Incidence of Childhood Cancer, 2001–2010: A Population-Based Registry Study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, C.; Larghero, P.; Almeida Lopes, B.; Burmeister, T.; Gröger, D.; Sutton, R.; Venn, N.C.; Cazzaniga, G.; Corral Abascal, L.; Tsaur, G.; et al. The KMT2A Recombinome of Acute Leukemias in 2023. Leukemia 2023, 37, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.; Pieters, R.; Biondi, A. How I Treat Infant Leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Luo, R.T.; Ptasinska, A.; Kerry, J.; Assi, S.A.; Wunderlich, M.; Imamura, T.; Kaberlein, J.J.; Rayes, A.; Althoff, M.J.; et al. Instructive Role of MLL-Fusion Proteins Revealed by a Model of t(4;11) Pro-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doblas, A.A.; Bueno, C.; Rogers, R.B.; Roy, A.; Schneider, P.; Bardini, M.; Ballerini, P.; Cazzaniga, G.; Moreno, T.; Revilla, C.; et al. Unraveling the Cellular Origin and Clinical Prognostic Markers of Infant B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Using Genome-Wide Analysis. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1176–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S.; Jackson, T.; Crump, N.T.; Fordham, N.; Elliott, N.; O’Byrne, S.; Fanego, M.D.M.L.; Addy, D.; Crabb, T.; Dryden, C.; et al. A Human Fetal Liver-Derived Infant MLL-AF4 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Model Reveals a Distinct Fetal Gene Expression Program. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, A.K.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Gedman, A.L.; Dang, J.; Nakitandwe, J.; Holmfeldt, L.; Parker, M.; Easton, J.; et al. The Landscape of Somatic Mutations in Infant MLL-Rearranged Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemias. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemels, J.L.; Smith, R.N.; Taylor, G.M.; Eden, O.B.; Alexander, F.E.; Greaves, M.F. Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR) Polymorphisms and Risk of Molecularly Defined Subtypes of Childhood Acute Leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4004–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.T.; Wang, Y.; Skibola, C.F.; Slater, D.J.; Lo Nigro, L.; Nowell, P.C.; Lange, B.J.; Felix, C.A. Low NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase Activity Is Associated with Increased Risk of Leukemia with MLL Translocations in Infants and Children. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2002, 100, 4590–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, M.C.; Linabery, A.M.; Chasnoff, S.; Hughes, A.E.O.; Mallaney, C.; Sanchez, N.; Giacalone, J.; Heerema, N.A.; Hilden, J.M.; Spector, L.G.; et al. Excess Congenital Non-Synonymous Variation in Leukemia-Associated Genes in MLL-Infant Leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group Report. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Linabery, A.M.; Blommer, C.N.; Langer, E.K.; Spector, L.G.; Hilden, J.M.; Heerema, N.A.; Radloff, G.A.; Tower, R.L.; Davies, S.M. Genetic Variants Modify Susceptibility to Leukemia in Infants: A Children’s Oncology Group Report. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Shield, K.; Koren, G.; Rehm, J.; Popova, S. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Obtained via Maternal Self-Reports versus Meconium Testing: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).