Abstract

The current need for territories and societies to grow is based on the Sustainable Development Models as well as the United Nations (UN) Agenda for 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In that case, such new forms of tourism development imply creating and upgrading critical infrastructures, facilities, equipment, or differentiated activities to bring clients who align with the desired Sustainable Development Models and SDGs. In this regard, the thematic literature provides evidence that some tourism typologies (nature-based, rural, culturally-based creative tourism) play a critical role in attaining sustainable regional development. Therefore, this paper aims to unfold what can be learned from the pilot projects implemented in the Azores region aimed toward the so-desired regional sustainability. Contextually, the obtained results ask for the regional leaders to consider encouraging entrepreneurship associated with small and medium-sized firms; fostering the diversity of touristic offerings; designing guidelines that follow sustainable development models and the SDGs; or creating meaningful investments in the conservation and protection of cultural heritage, as well as the Azorean endogenous resources.

1. Introduction

Tourists no longer desire a destination with a unique tourist experience offer and increasingly look to cultural and creative tourism (especially heritage, in many cases) as a deciding element when selecting a vacation location. In fact, tourist destinations only occur in places with culture and creative tourism which is associated with an offering [,,,,].

In this regard, several pieces of research show us that different tourism typologies (namely: rural tourism, cultural tourism, nature-based slow tourism, or creative tourism) have a dominant role in achieving regional sustainable development in ultra-peripheral island territories (see: [,,,,,,,,,,]).

Therefore, tourism is usually expected to align with different business models that cooperate to ensure a tourist magnet to a distinct region—the so-called tourist destination [,,,,,,,].

Suppose we consider the current need for territories and societies to grow based on the Sustainable Development Models and the United Nations (UN) Agenda for 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In that case, such new forms of tourism development imply creating and upgrading critical infrastructures, facilities, equipment, or differentiated activities to bring clients who align with the desired Sustainable Development Models and SDGs.

Based on the abovementioned, we do believe creative tourism could add to the regional sustainable development of remote insular regions in areas: it boosts the local economy, i.e., by attracting tourists to participate in creative experiences, the local economy can benefit through increased spending on local goods and services; it preserves local culture, i.e., creative tourism projects can help preserve and promote the cultural heritage and traditions of the island, making it a unique destination for visitors; it diversifies the tourism offer, i.e., by offering unique and creative experiences, islands can diversify their tourism offerings and stand out from more conventional tourist destinations; it creates employment opportunities, i.e., the development of creative tourism projects can generate new job opportunities, particularly in the arts and cultural sectors; and it fosters community development, i.e., by involving local communities in the planning and implementing creative tourism projects, they can foster a sense of ownership and pride, leading to improved community development.

Contextually, the research team has developed the following research question: “What Can We Learn From the Pilot Projects Implemented in the Azores Region Towards so-desired Regional Sustainability?”.

The paper starts with the current introduction framework, followed by a succinct state of the art regarding cultural and creative tourism in ultra-peripheral island regions. After that, a section is presented regarding the methods used, followed by the acquired results and subsequent discussion. The article ends with the conclusions.

2. Cultural and Creative Tourism in Island Regions

The small island developing states (usually known by the acronym SIDS) are a distinct group of 38 UN member states and 20 UN associate members in the regions commissions’ or non-UN members that meet particular social and economic as well as ecological vulnerabilities and have specific attributes [,,]. Furthermore, such destinations encounter considerable barriers and obstacles, i.e., small scale, remote geographic location, challenging accessibility constraints, limited vital resources, or even the menace of meeting global environmental problems and social and economic fragilities [,,].

Based on the abovementioned, it becomes crucial to look at previous research. As an example of the relevance of such tourism typologies for fragile and peripheral territories, it was already demonstrated by Williams’ [] studies that tourism generates work for regional, local, and even national economies. Correspondingly, the empirical proof indicates that tourist spending creates more employment and benefits than any other economic sector and contributes to regional economic development and strength [,,,].

In ultra-peripheral island regions, the available literature reveals that economic growth catalyzes sustainable regional development [,,,]. Hence, the possibility of designing and promoting other kinds of tourism, i.e., rural tourism, cultural tourism, nature-based slow tourism, or creative tourism, is related to entrepreneurship and new company and business models (mainly in the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)) [,]. Here, it becomes essential to highlight the new tourism paradigm that emerged during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: slow and rural tourism. This tourist trend seems more pertinent in ultra-peripheral island territories [,,,,].

UNWTO [] classifies rural tourism as the “(…) type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s experience is connected to an extensive content of products generally linked to nature-based activities, agriculture, rural lifestyle/culture, angling, and sightseeing”.

Rural tourism can be typed within the so-called “alternative tourism” or “new tourism products” and it is a form of tourism influenced by environmental factors []. It is a type of tourism with great potential to stimulate the growth of the local economy [].

Regarding cultural and creative tourism, it is understood that it encourages regional sustainable development by esteeming endogenous natural assets and resources, fostering a creative economy, and not diminishing culture through consuming products [,,,,,,]. Such implications produce room for liberation, independence, and new adventures, instigate contact with traditions and rituals, and induce gain through different tourist itineraries. However, Pimenta et al. [] tell us that “(…) one could be left to wonder about the kind of development concept addressed in the reviewed literature and its correlation with creative tourism”.

The same literature review paper from Pimenta et al. [] argues that it is feasible to detect the powerful connection between creative tourism and regional sustainable development. In fact, the research team says creative tourism works “(…) through some type of reality transformation process and demonstrates direct correlations with cultural, material and immaterial factors, by committing and involving local development agents–public and private–in the elaboration and implementation of cultural policies that attract creative tourists”.

In the Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines that are known for their ecotourism, beach tourism, cultural tourism, creative tourism, and nature-based tourism, among several others typologies of tourism, there is still a need to provide a dynamic, up-to-date, and detailed analysis of the progress towards sustainable tourism. Therefore, it is easy to understand that this is a global trend.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies pointing towards nature-based tourism and rural tourism becoming a tendency are easy to find. Research in African territories tells us that there is a growing number of nature-based tourism operators, mainly those committed to normative ecotourism and operating in regions where people gain their livelihood through multiple occupations. In fact, those mentioned above are not a new finding and according to previous authors, they seek to engage local people in their activities and to assure socioeconomic benefits to the local community. Besides their expected commitment to fundamental ecotourism principles, such nature-based tourism operators tend to act this way because their success will largely depend on community support. Although there is a general awareness that ecotourism is not the ultimate solution, commercially viable nature-based tourism ventures can be an essential tool for generating employment and economic benefits. A central goal of Namibe province’s tourism master plan (NTMP), in which ecotourism is considered an anchor product, is increasing the living standards of impoverished rural communities while observing ecological principles and promoting economically viable tourism ventures. Using the Sustained Development Model proposed by the Word Commission on Environment and Development as a reference, tourism ventures operating according to NTMP should seek a balance amongst the three pillars of sustainability.

Moreover, several other similar pieces of research provide evidence that there is a need to operate on growth and development models, concepts, and structures that contain regional social, ecological, and economic topics, which are the bases of the Sustainable Development Model. Regardless, different methods are viable concerning cultural and creative tourism. In this regard, Richards [] points us to the recent case of cultural and creative tourism and its various underlying backgrounds known worldwide.

It is conceivable to demonstrate that the nexus between cultural and creative tourism and various development techniques and procedures could drive additional developments which rely on the territory’s social and cultural characteristics and heritage and natural assets [,,,,,,].

3. Methodological Framework

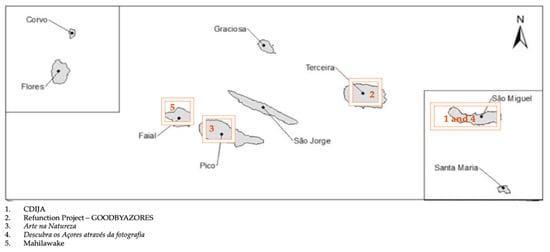

Considering this paper’s scope, we have applied analytical descriptive and inductive deductive methods. In fact, we applied to give coherence to these ideas that were essentially based on observation, our professional experience, site analysis of the pilot projects of creative tourism, and above all, on personal contact with the actors of the previous projects in the Azores territory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the Azorean creative pilot projects.

The actual theoretical-conceptual content aims to justify the interdependence between rural, nature-based, and creative tourism and regional sustainable development based on community testimony and its local sustainability. This article is part of the ongoing research that we are following at the University of Azores in partnership with the Tourism Observatory of the Azores (OTA) since we intend to argue later the relevance of fostering such tourism typologies for the Azores regional development as well as for the legitimate social interests of sustainable cultural management.

3.1. The Azorean Creative Pilot Projects

The analysis includes five pilot projects of cultural and creative tourism working in the Portuguese insular regions of the Azores. The assessed projects were: (i) CDIJA (CDIJA means Azores Child and Youth Development Center; in Portuguese: Centro de Desenvolvimento Infanto-Juvenil dos Açores); (ii) Refunction Project–GOODBYAZORES; (iii) Art in Nature (Arte na Natureza); (iv) Discover the Azores through Photography (Descubra os Açores através da fotografia); and (v) Mahilawake. Regarding their location, the case studies are located on four of the nine Azorean islands. Two are located on S. Miguel Island—namely CDIJA and Art in Nature projects; one on Terceira Island (Refunction Project–GOODBYAZORES); and, one on Faial Island (Mahilawake) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outline of the item selection queries about the business plan models of the pilot projects.

Surveys and Interviews

The surveys were divided into sections: (a) a brief description of the projects; (b) business models; and (c) creativity, culture, and social impact. Therefore, the entire interview included around fifty questions. Throughout the interview questions, the researchers have open-ended and item selection questions, as well as agreement-level affirmations (using a Likert scale).

Furthermore, the data for the study were collected through the existing assessment of the existing literature (indirect methods) combined with a case study research method (direct method). In fact, through talks and informal interviews with technicians, experts, and leaders in the fields of regional development, territorial policy as well as tourism entrepreneurs, we have been able to determine the focus of this research as well as the most relevant issues that should be answered throughout the present paper. Therefore, connecting with phase one, the developed literature review intended to cover a wide range of issues, such as the state of the art regarding rural tourism, creative tourism, regional development, and the main considerations for sustainable development strategies designed through tourism. In addition, it should be added that more than 50 interviews and surveys were conducted with the pilot projects leaders, the consultants, and the customers.

3.2. Tourism Situation in the Azores—In Brief

The tourism industry is vital for the Azorean economy. Therefore, to summarize, we have: (i) growing popularity—the Azores have seen an increase in popularity as a tourist destination in the last few years, attracting visitors with its stunning natural scenery, unique cultural heritage, and outdoor recreational opportunities; (ii) sustainable tourism focus—the Azores have adopted a sustainable tourism approach, promoting responsible and ecofriendly tourism practices to preserve the natural environment and local communities; (iii) increased air connectivity—the Azores have seen an increase in air connectivity with mainland Portugal and other destinations, making it easier for tourists to reach the islands; (iv) diversified offerings—the Azores offer a range of tourist experiences, including outdoor recreation, cultural heritage, and food and wine tourism, providing a diverse and appealing destination for visitors; and (v) challenges—despite its growing popularity, the tourism industry in the Azores faces challenges such as seasonality, limited infrastructure, and limited capacity for large scale events.

In general, the tourism industry in the Azores has been growing and diversifying, focusing on sustainable tourism practices. However, some challenges must be addressed to fully realize its potential as a tourist destination.

Azorean Landscapes Richness—In a Nutshell

The Autonomous Region of the Azores, a total of nine volcanic islands in the Atlantic Ocean, are renowned for their breathtaking landscapes and unique biodiversity. The islands are characterized by rolling green hills, towering cliffs, pristine beaches, and pristine lakes surrounded by lush vegetation. The Azores also have several protected areas and nature reserves that are home to a wide variety of endemic flora and fauna, as well as several rare species of birds and marine life. The landscapes of the Azores, combined with the islands’ warm, temperate climate, make it a popular destination for tourists looking to experience the beauty of nature.

Furthermore, the Azores are home to a diverse range of endemic flora, including many species of plants and trees found nowhere else in the world. Some of the most notable endemic flora species in the Azores include: (i) Azores laurel forest—this unique forest type is found only in the Azores and the Madeira Islands and is characterized by its lush vegetation and diverse array of endemic plant species, such as the Azorean Holly and the Madeiran Laurel; (ii) Azorean heather—a type of low-growing shrub that is commonly found in the high-altitude areas of the Azores and is known for its delicate purple flowers and green leaves; (iii) Azorean juniper—native to the Azores, and is found growing in the volcanic soils and rocky outcroppings of the islands; and (iv) Azorean hydrangea—a type of hydrangea that is endemic to the Azores and is known for its beautiful clusters of pink and blue flowers.

In fact, these are just a few examples of the unique and diverse endemic flora that can be found in the Azores, making the islands a botanist’s paradise and a must-visit destination for nature lovers.

4. Outcomes

Considering the large number of results obtained through the surveys, this section was separated into subsections to create a more effortless reading and analysis of the outcomes.

4.1. Overall Statistics

In Table 2, it is possible to find a summary of the collected data regarding the total number of firms operating in the Azores Autonomous Region (the pilot projects study area) as well as the values of their capital and labor force. Furthermore, we can observe if those firms are domestic or foreign.

Table 2.

Summary statistics.

Total Factor Productivity

Total factor productivity (TFP) is a measure of economic growth that takes into account both the inputs used (labor, capital) and the output produced (goods, services). It is calculated as the ratio of output to inputs and represents the efficiency with which inputs are used to produce output. TFP can increase through technological advancements, better use of resources, and increased efficiency, leading to higher economic growth.

TFP is considered a vital indicator of an economy’s competitiveness and potential for long-term growth, as it captures both supply-side and demand-side factors that impact productivity. TFP can also compare the productivity of different industries, regions, or countries. Nevertheless, TFP can be challenging to measure accurately as it can be influenced by factors such as changes in quality, unmeasured inputs, and data measurement errors.

More than five hundred firms are operating in the region. Only 7% of the total firms have a foreign share. When comparing the means of the domestic and foreign firms, we have evidence that the highest TFP numbers are related to foreign firms. Regarding the values related to capital and labor, the highest values could be found in domestic firms.

4.2. The Azorean Creative Tourism Pilot Projects by Field

Through the performed analysis, the five Azorean creative tourism pilot projects were divided by thematic fields (Table 3). In addition, from now on, for a more straightforward interpretation in the tables, the Azorean Creative Tourism pilot projects will be identified by number:

Table 3.

Azorean creative pilot projects by fields.

- CDIJA

- Refunction Project–GOODBYAZORES

- Art in Nature

- Discover the Azores through Photography

- Mahilawake

Throughout Table 3, it is feasible to understand the applicability and importance of the Azorean creative tourism pilot project in the various fields. Furthermore, we can comprehend the pertinence of the projects for the development of regional human resources.

4.3. The Azorean Creative Pilot Projects Business Model Pattern

Based on Table 1, most of the CDIJA project’s customers are international. About the audience, the project plans to deliver an offer to protect families with minors with autism. Through the training of human resources for this specific public, it is expected to spread the response to a broad audience in the field of inclusive and health tourism. Thereby, with this initiative, it is considered vital for their customers to take part in such activities, admitting that the “ready for autism” seal is a qualified, distinguished, and sharp response to the issues of these families with minors with autism.

The project has yet to meet customers’ expectations for the high season. The project leaders are exploring their client’s profile and triggers through the International Certification as a Tourism Agent for Autism by IBCCES. Moreover, based on a Likert scale, it is considered that the size of the market for their thematic tourism offer between the winter and the spring months (of 2022) relays on level three of five in a Likert scale. Currently, the project has collaborations with tourism businesses, i.e., the Azorean Travel Agency DMC, as well as a partnership with national and international bulletins to promote and advertise the initiative. They do not have any public partnerships already. If we consider human resources (HR), they are travel agencies and technicians specializing in Autism. The primary resources came from CDIJA-Children and Youth Development Center of the Azores. The PO2020 program funding mostly sustains economic-financial resources. The HR lay on synergies with a UAc (University of the Azores) research team financed by the project. Project leaders believe that the gains from the visionary offer are satisfactory to shield the costs of the initiatives’ investments. In addition, the central costs of the projects are variable. Therefore, to ensure the success of this initiative, more investment is needed. The components of the project with the most significant cost burden are the physical resources. Currently, no returns are being generated.

In the “REFUNCTION PROJECT–GOODBYE AZORES”, most clients are international. This initiative targets different tourism demand public segments. Based on the client’s feedback, the primary motivations for participation in this project’s initiatives are contact with new creative realities. Now, this project does not have any paying clients yet. The activities are integrated into other cultural initiatives. They have nine clients confirmed in June 2022. They would like to reach 100 clients by the end of the high season. Project leaders have assessed the profile and motivations of their customers through interaction. On a five-point Likert scale, they consider that the degree of demand for their creative tourism offer between the winter and spring months (of 2022) is on level two of the scale. The initiative has not yet partnered with tourism companies and national and international magazines to develop marketing and advertisement around their project. However, the project had partnerships with public organizations. The HR engaged in this project are qualified; they consider that the revenues obtained from their creative offer are not sufficient to cover the costs; until now, the investments in the project have been low; the main costs of the projects are variable costs changing with the activities being offered and the seasons of the year; in order to guarantee the success of the project, it is necessary to invest more. Human resources are the elements of the project with the highest costs. This project does not generate any profits, and this needs to be tackled to guarantee survival in the long run.

In the case of the “ART IN NATURE” project, the clients have been all Portuguese since the pandemic started in 2019. Before the pandemic, most of them were foreigners. Their potential clients’ profile shows that they are interested in artistic culture. This project targets different age-break market segments. Based on customers’ feedback, the client’s motivations to participate in this project are “looking for something different” related to culture. In 2021, they had 58 clients since June. In 2022, they had 32 clients since January. Currently, they have no confirmed clients, as this project only receives bookings a few days before the events. The leaders analyze the profile and motivations of their customers only through interaction with the clients during their experiences on the premises. According to a five-point Likert scale, the project entrepreneurs consider that they had a level of demand for their creative tourism offer rated five between January and April 2022. This project has partnerships with tourism companies. Moreover, it does not have national and international magazines to publicize and promote its project’s activities. They have qualified human resources as well as financial and human resources. They consider that, so far, the revenues generated by their creative offer have not been sufficient to cover costs; the project’s investments to date have been low; the main costs of the projects are variable; for the initial success, it is necessary to invert. Promotion costs are the most significant cost burden. The initiative does not raise any profits.

In the “Discover the Azores through Photography” project, the clients are local people, Portuguese coming from Portugal’s mainland and Madeira islands, and a few foreigners. Their potential customers and their target audience are people who like photography. The taste for photography is the primary motivation for clients to participate in this project, according to their feedback. From January 2022 until the end of the high season, this creative tourism project has had forty-one clients. This project has yet to have any bookings currently, but we are now in the low season until March 2023. The project leaders analyzed the profile and motivations of their customers through interactions during the experiences offered. On a five-point Likert scale, they consider that the level of demand for their creative tourism offer between January and April 2022 is level three. This project has partnerships with tourism companies (hotels) but not with city councils or parish councils, national and international magazines to publicize and promote their project, and not with raw material suppliers.

In addition, the existing resources in the project (human, physical, financial) need more information available. They consider that the revenues from their creative offer are sufficient to cover the supply costs; the investment in the project to date has been low. This project exhibits positive profits and they are satisfied with its profit.

Most clients of the Mahilawake initiative are national. According to the project leader, the likely consumers are mainly women. The initiative focuses on individuals interested in adventure, travel, and personal growth. Considering the clients’ feedback, their motivations for participating in the project’s activities depend on the fact that it is a different product in the region and is associated with health and personal wellbeing. From the project’s start until the last summer months, the project leaders affirm to have twelve customers. In addition, in the 2022 high season, they have four clients. In the same line, four customers were confirmed for high-season activities and around 18 to 20 were booked. They analyze the profile and motivations of their customers through interactions during experiences. Considering the Likert scale results, the demand for their creative tourism actions is mostly on level three. The initiative has associations with tourism firms but not with public organizations; national and international bulletins to advertise and develop marketing around their project are also in perspective. However, there are no collaborations with raw material suppliers.

Furthermore, the projects’ leaders assume the incomes from the initiative are enough to shield the costs. Currently, the investments in the project have been low. The project’s primary expenses are variable costs. In order to guarantee the initiative’s success, more investment is required. The details of the project with the most significant cost burden are physical resources. The initiative has a profit. Nevertheless, the project leaders must still be comfortable with the project’s returns situation.

5. Discussion

Let us focus on an individual manner, on the business model patterns of the analyzed project. In that case, we reach two main models: (x) targeting foreign tourists (an international model), and (y) targeting Portuguese (a national model). However, a typical tourist profile pattern emerges in the x and y models: “a tourist that pursues a cultural, rural, and nature-based tourism”. Corroborating previous studies (see: [,]), such outcomes are in sequence with the fact that they occurred in many of the low-density, ultra-peripheral, and insular regions during the COVID-19 outbreak, where the customer (tourist) pursues these kinds of tourism modalities [,,,,,,,].

The ultra-peripheral island territories and the low-density region are seen as the most attractive destinations to satisfy the tourist´s expectations in the COVID-19 pandemic momentum as well as in the post-pandemic paradigm of tourism [,,,,]. Along the same line, UNWTO sustains that other tourism typologies (mostly rural or nature-based) are becoming more engaging to tourists because tourists seek non-massive tourist destinations with open-air environments. Furthermore, after the coronavirus 2020 outbreak, the European authorities have launched several special efforts and techniques for tourism sustainability, i.e., the European Parliament report of 25 March 2021.

Consequently, these territories have several barriers related to economic decay, high unemployment, population exodus, adverse consequences resulting from the transformation of agricultural land, and a loss of a sense of belonging or cultural identity []. Accordingly, tourism and the actions inherent to tourism can and should add extensively to the growth and development of rural areas and low-density or remote regions.

Moreover, in remote territories and low-density regions (usually less competitive), agriculture plays a primary function [,,], which is even more pertinent in the regions of Southern Europe. Contextually, the ultra-peripheral regions of these territories are no exception—the Madeira, Canary Islands, and Azores archipelagos are just some examples; actually, this problem becomes more significant in these overseas regions [,].

Furthermore, the conservation of the endemic flora and fauna of the Azores is a high priority, and several techniques and strategies are used to protect and preserve this unique and valuable biodiversity. Some of these techniques include: (a) Protected areas—the Azores has several protected areas, including nature reserves and national parks, that are designated to protect the unique and fragile ecosystems of the islands. These areas are carefully managed to minimize the impact of human activities and preserve the native flora and fauna. (b) Species management, i.e., for species at risk of extinction, specific management plans are developed and implemented to protect and conserve them. These plans may involve the introduction of conservation measures, such as habitat restoration, the removal of invasive species, and the monitoring of populations. (c) Sustainable tourism—the Azores are a popular tourist destination, and the local government is working to promote sustainable tourism practices that minimize the impact of visitors on the island’s ecosystems. This may include promoting responsible hiking and wildlife viewing and working with local businesses to reduce their environmental impact. (d) Education and outreach-providing education and outreach programs to local communities, tourists, and other stakeholders is an essential aspect of conservation efforts in the Azores. These programs raise awareness of the unique and valuable biodiversity of the islands and encourage people to take an active role in their protection.

The case studies briefly assessed the cultural and creative tourism projects in the Azores archipelago that exactly fit that purpose. Contextually, it is suggested that the regional administration, autonomous leaders, and other suitable main actors and players in the Azores territory design and implement plans to boost such cultural and creative tourism initiatives. In fact, they show that it not only adds to sustainable regional growth but also is a potential alternative to the non-sustainable mass tourism model unsuitable for promoting the Azores’ brand. In addition, the studied projects permit regional financial regeneration through collaborations with different tourism firms, cultural institutions, and public organizations, mainly on the islands where the projects are placed.

By combining these and other techniques, the conservation of the Azores’ endemic flora and fauna can be sustained and protected for future generations to enjoy.

In this case, the results could be considered similar to several other outcomes encountered in remote insular territories; nevertheless, the Azores has a unique potential for the development of nature-based tourism and slow tourism. The Azores, a Portuguese autonomous region in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, has the potential to benefit greatly from creative tourism as part of its regional development strategy. Here are some ways creative tourism can contribute to the development of the Azores: (a) preserve cultural heritage—the creative tourism projects can help to preserve the unique cultural heritage of the Azores, such as traditional crafts, music, and food, making it a distinct tourist destination; (b) diversify the tourism offer—the Azores can diversify its tourism offerings by offering creative experiences, such as workshops on traditional crafts, music, and cuisine, which can attract a different type of tourist; (c) boost local economy—the creative tourism can generate additional revenue for local communities through increased spending by visitors on local goods and services; (d) create employment opportunities—the development of creative tourism projects can create new job opportunities, particularly in the arts and cultural sectors; and (e) foster community development—by involving local communities in the planning and implementation of creative tourism projects, the Azores can foster a sense of ownership and pride, leading to improved community development.

Overall, creative tourism can help to enhance the cultural identity and economy of the Azores, making it a unique and attractive tourist destination. In fact, this goes in line with the authors’ beliefs expressed in the introductory section of this paper.

6. Conclusions

Consequently, in an attempt to answer this paper’s research question, we consider the following approaches and principles should be considered in the search for and grant of long-term regional sustainability related to sustainable growth, creative and cultural management in the Azores Autonomous Region:

- (i)

- encourage entrepreneurship, associated with small and medium-sized firms, promoting the diversity of its touristic offering;

- (ii)

- design guidelines that follow sustainable development models and the SDGs;

- (iii)

- create meaningful investments in the conservation and protection of cultural heritage as well as the Azorean endogenous resources;

- (iv)

- promote the relations between societies and the regional assets and innovative businesses;

- (v)

- prioritize rural tourism over mass tourism;

- (vi)

- facilitate collaboration among the public sector, the private sector, and society in general, and foster their active participation.

To conclude, this work is the first to extract guidelines for the regional development and growth of ultra-peripheral island territories through cultural and creative tourism in the Macaronesia region in a post-COVID-19 scenario.

7. Research Limitations and Prospective Studies

Regarding the limitations of this study, it was attainable to emphasize the implementation of the testing tools during the COVID-19 pandemic moment. For example, conducting the study during this period, we felt some limitations, not only for the research team’s ability to travel and develop the interviews on the scheduled dates but also in the responses given by the participants, as it was a period of apprehension within the tourism sector.

Furthermore, if a more comprehensive and diverse sample were used—i.e., including the population in general as well as the tourists, entrepreneurs from different projects, and many other relevant players—it would strengthen our ability to handle this problem from different viewpoints. In addition, comparing this study methodology with others, such as inquiries, interviews with locals, or other variables, (perhaps) could enrich this research.

In this sense, there is also the opportunity, in future studies, to use secondary data to describe the tourism situation in the research area (infrastructures, employment, tourism traffic, among several others). Furthermore, specific comparison studies with other insular territories (Madeira, Canary Islands, New Zealand, and Hawaii are just a few examples) could promote the debate on this topic and acquire advances in the thematic literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization R.A.C.; methodology, C.S.; software, G.C.; validation, G.C. and C.S.; formal analysis, R.A.C.; investigation, G.C.; resources, C.S.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.C.; writing—review and editing, R.A.C.; visualization, G.C. and C.S.; supervision, R.A.C.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is financed by Portuguese national funds through FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., project number UIDB/00685/2020, and UIDB/04470/2020, and also by the project CREATOUR Azores—Turning the Azores into a Creative Tourism Destination (ACORES-01-0145-FEDER-000127). CREATOUR Azores is coordinated by the Azores Sustainable Tourism Observatory and developed in partnership with the University of the Azores/Gaspar Frutuoso Foundation, being financed by the FEDER, through the Azores Operational Program 2020 and by regional funds, through the Regional Directorate for Science. and Technology. Also, by the project UID/SOC/04647/2013, with the financial support of FCT/MEC through national funds and, when applicable, co-financed by FEDER under the PT2020 Partnership.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available. In addition, it is possible to contact one of the study authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koçak, E.; Ulucak, R.; Ulucak, Z.Ş. The impact of tourism developments on CO2 emissions: An advanced panel data estimation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Couto, G.; de Albergaria, I.S.; da Silva, L.S.; Medeiros, P.D.; Simas, R.M.N.; Castanho, R.A. Analyzing Pilot Projects of Creative Tourism in an Ultra-Peripheral Region: Which Guidelines Can Be Extracted for Sustainable Regional Development? Sustainability 2022, 14, 12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baixinho, A.; Santos, C.; Couto, G.; da Albergaria, I.S.; da Silva, L.S.; Medeiros, P.D.; Simas, R.M.N. Creative Tourism on Islands: A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, J.; Jordá, M. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: The Spanish case. Appl. Econ. 2010, 34, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Oliveira, A.; Ponte Crispim, J.; Santos, C.; Estimaand, D.; Castanho, R.A. SmartDest: Converting the Azores Into a Smart Tourist Destination. Chapter #25 in the IGI GLOBAL Handbook of Research. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Development Goals, Climate Change, and Digitalization; IGIGLOBAL: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 409–432. ISBN 13: 9781799884828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Aliseda, J.; Garrido Velarde, J.; Bedón Garzó, R. Indicators for Sustainable Management in the Yasuni National Park; Wseas Transactions on Business and Economics: Athens, Greece, 2017; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R. O Regresso dos Emigrantes Portugueses e o Desenvolvimento do Turismo em Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Santos, C. Tourism Promoting Sustainable Regional Development: Focusing on Rural and Creative Tourism in Low-Density and Remote Regions. Rev. De Estud. Andal. 2023, 45, 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Schyff, T. The Development and Testing of a Measurement Instrument for Regional Tourism Competitiveness Facilitating Economic Development. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University (NWU), Brisbane, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Croes, R.; Rivera, M. Tourism’s potential to benefit the poor: A social accounting matrix model applied to Ecuador. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Velarde, J.; Montero-Parejo, M.J.; Hernández-Blanco, J.; García-Moruno, L. Visual Analysis of the Height Ratio between Building and Background Vegetation. Two Rural Cases of Study: Spain and Sweden. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, W. Regional Integration and Sustainable Development in the Yangtze River Delta, China: Towards a Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. Land 2023, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, C.A.M.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Remoaldo, P. Regional Development and Creative Tourism: A Bibliometric Survey of the Literature Available in Two Scientific Literature Databases. Rev. Bras. De Gest. E Desenvolv. Reg. 2021, 17, 290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, F.; Silva, Y. ‘Project Querença’ and creative tourism: Visibility and local development of a village in the rural Algarve. E-Rev. Tour. Res. (eRTR) 2017, 14, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, H. Remote Island Tourism: A Case Study in Fiji. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 248, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Santos, R. Introductory Chapter: Rural Tourism as a Catalyst for Sustainable Regional Development of Peripheral Territories. In Peripheral Territories, Tourism, and Regional Development; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargues, P.; Loures, L. Using Geographic Information Systems in Visual and Aesthetic Analysis: The case study of a golf course in Algarve. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2008, 4, 774–783. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, H.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Amin, Q. Estimating Total Contribution of Tourism to Malaysia Economy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2009, 2, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Behradfar, A.; Castanho, R.; Couto, G.; Sousa, A.; Pimentel, P. Analyzing COVID-19 Post-Pandemic Recovery Process in Azores Archipelago. Konuralp Med. J. 2022, 14, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourtellot, J. Destinations rated: 111 islands. Natl. Geogr. Travel. 2007, 24, 108–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, G.; Jiménez, J.M.; Secondi, L. Tourists’ Expenditure in Tuscany and its impact on the regional economic system. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Behradfar, A.; Vulević, A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M. Analyzing Transportation Sustainability in the Canary Islands Archipelago. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Vulevic, A.; Behradfar, A.; Couto, G. Assessing Transportation Patterns in the Azores Archipelago. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. The impact of distance on tourism: A tourism geography law. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascariu, G.; Ibanescu, B. Determinants and implications of the tourism multiplier EECT in EU economies. Towards a core-periphery pattern? Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 982–997. [Google Scholar]

- Tiago, F.; Oliveira, C.; Brochado, A.; Moro, S. Mapping Island Tourism Research. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCastanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á.; Garrido Velarde, J. Assessing the Impacts of Public Policies Over Tourism in Azores Islands. A Research Based on Tourists and Residents Perceptions. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2020, 16, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Introduction. In Southern Europe Transformed-Political and Economic Change in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain; Williams, A., Ed.; Harper & Row: London, UK, 1984; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavdar, U.; Belgibayav, A.; Mersakylova, G. The role of developing direction of international tourism in Kazakhstan. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Repub. Kazakhstan 2016, 2, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Meller, P.; Marfán, M. Small Large Industry: Employment generation, linkages, and key sectors. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1981, 29, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- King, R. Return Migration and Regional Economic Development. In Return Migration and Regional Economic Problems; Croom Helm: Sydney, Australia, 1986; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gürdallı, H.; Bulanık, S. Socio-Cultural Recovery of the Border in Nicosia: Buffer Fringe Festival over Its Boundaries. Land 2023, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitoun, R.; Sander, S.; Masque, P.; Pijuan, S.P.; Swarzenski, P. Review of the Scientific and Institutional Capacity of Small Island Developing States in Support of a Bottom-up Approach to Achieve Sustainable Development Goal 14 Targets. Oceans 2020, 1, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.; Lee, T.; Li, X. Sustainable development for small island tourism: Developing slow tourism in the Caribbean. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Lousada, S.; Garrido Velarde, J.; Castanho, R.A.; Loures, L. Land-Use Changes in the Canary Archipelago Using the CORINE Data: A Retrospective Analysis. Land 2020, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Small Islands Tourism: A Review. Acta Turistica 2020, 32, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M.; Dodds, R.; Butler, R. Island Tourism Sustainability and Resiliency; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.M.; Sousa, C.; Albuquerque, H. Analytical Model for the Development Strategy of a Low-Density Territory: The Montesinho Natural Park. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mediano-Serrano, L. La Gestión de Marketing en el Turismo Rural; Pearson Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OMT. Concepto de Turismo Rural. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/turismo-rural (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.B.; Sousa, Á. The Potential of Adventure Tourism in the Azores: Focusing on the Regional Strategic Planning. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems, ICOTTS 2020. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Abreu, A., Liberato, D., González, E.A., Garcia Ojeda, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 209, pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.; Castanho, R.; Pinto-Gomes, C.; Santos, P. Merging Traditional Livelihood Activities with New Employment Opportunities Brought by Ecotourism to Iona National Park, Angola: Rethinking Social Sustainability. In Planeamiento Sectorial: Recursos Hídricos, Espacio Rural y Fronteras; Aranzadi, T.R., Ed.; Thomson Reuters: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 293–303. ISBN 978-84-1309-065-8. [Google Scholar]

- Solima, L.; Minguzzi, A. Territorial development through cultural tourism and creative activities. Mondes Du Tour. 2014, 10, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Panorama of Creative Tourism around the World. In Seminário Internacional de Turismo Criativo; Cais do Sertão: Recife, PE, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mahony, K.; Zyl, J. The Impacts of Tourism Investment on Rural Communities: Three Case Studies in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2002, 19, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SoSousa, À.; Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P. Post-Covid tourism planning: Based on the Azores residents’ perceptions about the development of regional tourism. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzic, P.; Demonja, D. Transformations in business & economics. Econ. Impacts Rural Tour. Rural Areas Istria 2017, 16, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, C.; Moreira, M. Creative Tourism and Urban Sustainability: The Cases of Lisbon and Oporto. Rev. Port. De Estud. Reg. 2019, 51, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Labrianidis, L.; Ferrão, J.; Hertzina, K.; Kalantaridis, C.; Piasecki, B.; Sma-llbone, D. The Future of Europe’s rural periphery. Final Report. In 5th Framework Programme of the European Community; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H. Tourism, Local Economic Development, and poverty reduction. Appl. Res. Econ. Dev. 2008, 5, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.B.; Sousa, Á.; Graça Batista, M.; Lousada, S. The Opinions of Decision-Makers Regarding the Rural Tourism Development Potential in the Azores Region. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems; Castanho, R.A., Couto, G., Pimentel, P., Carvalho, C., Sousa, Á., da Graça Batista, M., Lousada, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 293, Chapter 41; ISBN 978-981-19-1039-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberger, A.Y.; Shoval, N.; McKercher, B. Typologies of tourists’ time–space consumption: A new approach using GPS data and GIS tools. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, A.; Felsenstein, D. Support for Rural Tourism—Does it Make a Difference? Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulevic, A.; Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Garrido Velarde, J.; Martín Gallardo, J.; Lousada, S.; Loures, L. Common Regional Development Strategies on Iberian Territories. a Framework for Comprehensive Border Corridors Governance: Establishing Integrated Territorial Development [Online First]; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jeri, A. El Comportamiento del Consumidor Convencional de Alimentos Durante el COVID-19, en el Perú. Spec. Issue: Reflex. Sobre Coronavirus Impactos Rev. Científica Monfragüe Resiliente—Sci. J. 2020; 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A. A pandemic crisis shocking us all: The COVID-19. Spec. Issue Reflex. Sobre Coronavirus Impactos Rev. Científica Monfragüe Resiliente—Sci. J. 2020; 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Agius, K. Doorway to Europe: Migration and its impact on island tourism. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2021, 10, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.P.; Guedes, A.; Bento, R. Rural tourism recovery between two COVID-19 waves: The case of Portugal. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokou, D.; Darra, A.; Kavouras, M. Are New Cartographies Strengthening a Sustainable and Responsible Island Tourism? In Smart Cities, Citizen Welfare, and the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals; IGIGLOBAL: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytkönen, P.; Tunón, H. Summer Farmers, Diversification and Rural Tourism—Challenges and Opportunities in the Wake of the Entrepreneurial Turn in Swedish Policies (1991–2019). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Lopes, T. Application of smart tourism to nature-based destinations. In Strategic Business Models to Support Demand, Supply, and Destination Management in the Tourism and Hospitality; Carvalho, L., Calisto, L., Gustavo, N., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rebola, F.; Loures, L.; Ferreira, P.; Loures, A. Inland or Coastal: That’s the Question! Different Impacts of COVID-19 on the Tourism Sector in Portugal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Barreto Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á. How SARS-CoV-2 crisis could influence the tourism intentions of Azores Archipelago residents A study based on the assessment of the public perceptions. World Rev. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 19, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waniek, M.; Castanho, R.A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Croatia’s tourism sector. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Regional Science: Challenges, Policies and Governance of the Territories in the Post-Covid Era, Granada, Spain, 22 October 2022; pp. 109–112, ISBN 978-84-09-44259-1. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A. Social and Economic Impacts. In Cultural Sustainable Tourism Strategic Planning for a Sustainable Development; Series: Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Mandić, A., Stankov, U., Castanho, R.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-3-031-10800-6. [Google Scholar]

- Abellera, K.; Castanho, R.A. Analysis of the Sustainable Tourism Development in Indonesia. In Nuevas Estrategias para un Turismo Sostenible; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Madrid, Spain; Athens, Greece, 2022; pp. 371–380. ISBN 978-84-1124-804-4. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, M.D.G.; Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Sousa, Á.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C. The Rural and Nature Tourism Development Potential in Islands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J.; Bollman, R. Rural Employment in industrialized countries. Agric. Econ. 2000, 22, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G. Understanding Creative Tourism as a Potential Catalyst for Regional Economic Development in Ultra-Peripheral Territories: Highlighting Pilot-Projects in the Azores Islands. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2022, 20, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Vass, A. Tourism, farming and diversification: An attitudinal study. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Laws, E. Stimulants and inhibitors in the development of niche markets-The whale’ stale. In Proceedings of the CAUTHE 2004, Brisbane, Australia, 9–12 February 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cannonier, C.; Burke, M.G. The economic growth impact of tourism in Small Island Developing States—Evidence from the Caribbean. Tour. Econ. 2018, 25, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).