Abstract

This study examines the design and utilization of shared streets in the Jiefangbei Business District of Chongqing through the lens of geographical semiotics. Employing photo content analysis, video observation, and questionnaire surveys, this research delves into visual semiotics, place semiotics, and users’ interaction order, including social interactions and traffic experiences within these shared spaces. The findings reveal that two distinct systems guide pedestrians and vehicles on Jiefangbei’s shared streets, ensuring safety and cultural expression. Paving is identified as the most important method for realizing the sharing of space between people and vehicles. Street furniture emphasizes multifunctional composite use and reflects Jiefangbei’s eclectic style since its era as a financial center of the Republic of China, responding to cultural resources and functional positioning. The study also indicates that social functions and public space attributes need enhancement, recommending more greenery and leisure facilities. Interaction order analysis shows that participants’ perception of street sharing does not affect their sense of safety and effectiveness. Thus, future practice should base decisions on specific traffic conditions and urban functions. A limitation of this study is the inability to accurately sample the population structure of the Jiefangbei commercial district, preventing more adaptable conclusions. The authors suggest viewing shared space as an evolving process and recommend future research on long-term effects and cross-cultural comparative studies to provide valuable insights into global shared-street design.

1. Introduction

Since the 1960s, shared streets have been employed globally as a design approach to balance traffic functions while fostering a pleasant atmosphere in residential and commercial areas [1,2,3]. In China, this method has significant potential for transforming various commercial and residential spaces. For example, in the renovation of old city commercial blocks, pedestrian rights are often emphasized by either converting the area into a pedestrian street or restricting motor vehicle access. This emphasis is due to the typical characteristics of these commercial spaces: a dense road network, small block scale, pedestrian-friendly environment, and rich cultural resources. Shared streets are implemented in commercial blocks to meet logistical and transportation needs while prioritizing the pedestrian experience. Notable examples include the renovation of Anshan Road in Heping District, Tianjin [4]; Shaocheng District in Chengdu [5]; and Dafu Road in Fuyang District, Hangzhou [6].

Despite the numerous post-design analyses of shared streets in China, most focus on traffic safety and pedestrian design strategies, often neglecting the socio-spatial perceptions of users on shared streets. This study focuses on the shared spaces in the commercial district of Jiefangbei in Chongqing. This area is located in the commercial and historical center of Chongqing, a major city in western China, with abundant cultural resources and a high proportion of shared streets. One of the reasons for choosing the Jiefangbei case is that urban decision-makers did not prioritize concepts such as “shared streets” or “shared spaces” during the actual construction and update of its shared streets. This allows us to understand the genuine attitudes and perceptions of street users towards such urban “heterogeneous” spaces. The research problem of this study centers on how designers and users perceive and understand the cultural, social, and transportation functions of shared streets. The study aims to provide a comprehensive response to this problem through geographic semiotic analysis. This paper also advocates for a more thorough examination of how urban planners and decision-makers integrate shared-street concepts and design methods into local commercial environments. It aims to understand pedestrians’ perceptions and the impact of shared-street design on various activities and provide recommendations for future projects.

2. Literature Review

“Shared street” refers to a street design where pedestrians, motor vehicles, bicycles, and other users share the same road surface. The concept originated in the Netherlands in the 1960s, when the Woonerf was developed. In practice, street markings, curbs, and barricades are often removed to integrate traffic and residential activities and promote walking. Since the 1970s, similar practices have been implemented in Western countries to improve pedestrian safety and experience in residential areas, such as Rest and Play Areas in Germany, Encounter Zones in Switzerland, and Home Zones in the United Kingdom. In the early 21st century, design concepts like complete streets have aimed to provide safe mobility and accessibility for all users, particularly pedestrians and cyclists [2]. In China, shared-street practices have gradually emerged with a shift away from car-centric design, as seen in projects like the revitalization planning of Zhongshan Avenue in Wuhan’s Jianghan District and the street design of Shanghai’s Lujiazui Central Business District [7]. There have also been efforts to transform traffic spaces in densely populated old communities [8].

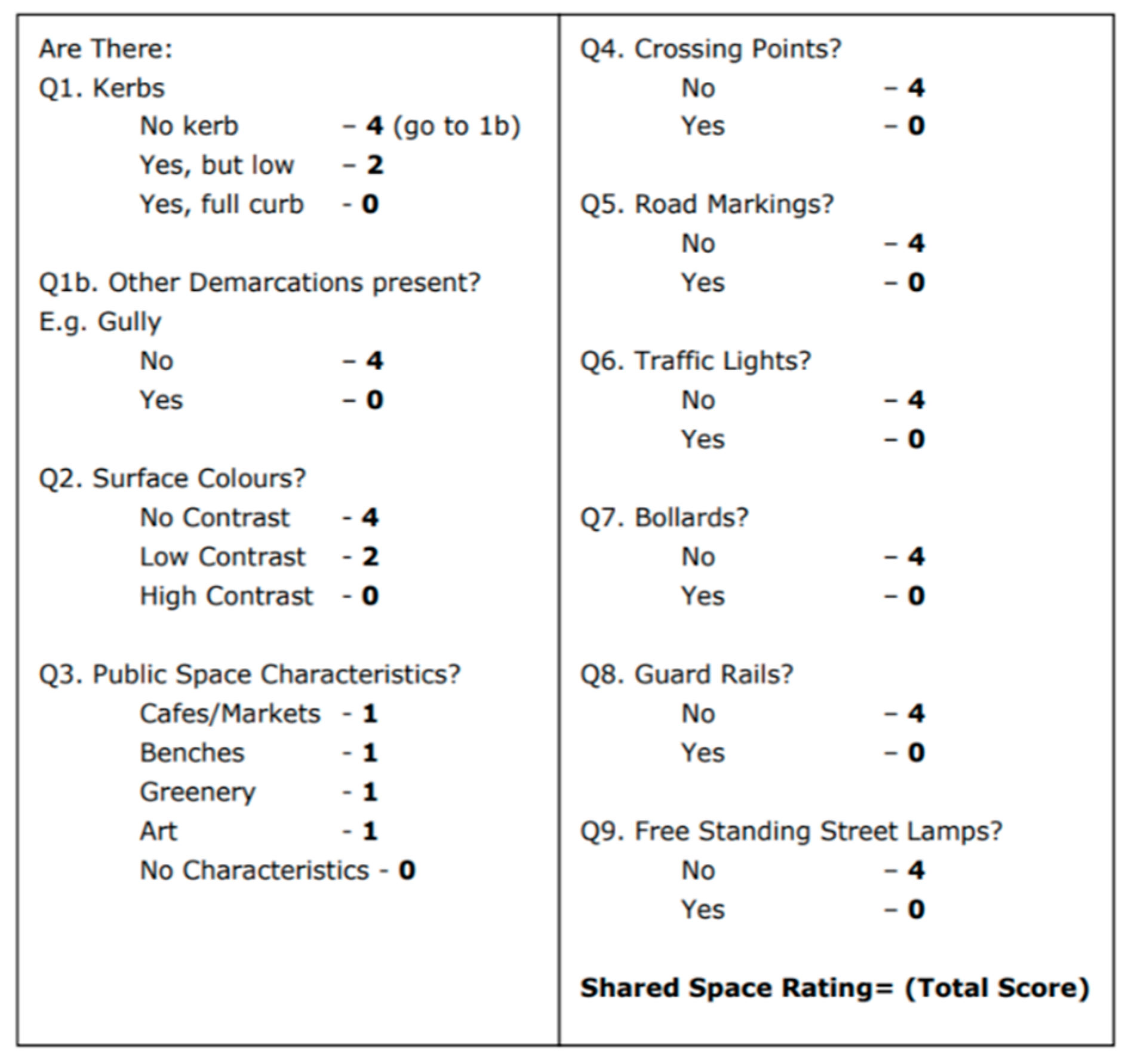

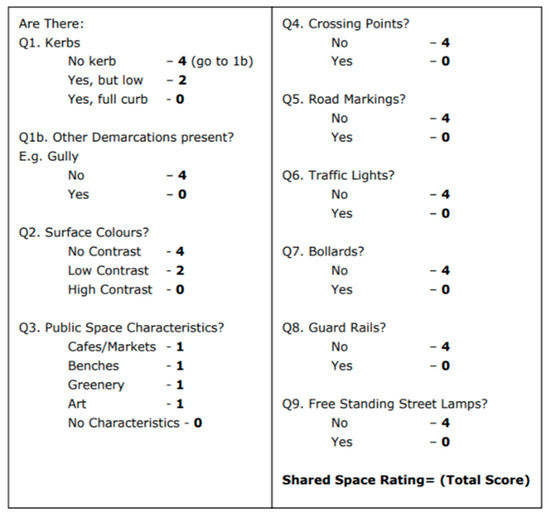

The design of shared streets centers on the removal of traffic signs and roadside barriers, allowing pedestrians and vehicles to use the road surface at the same level. The UK Department for Transport’s shared-space evaluation coefficient, established in 2010, assesses the extent of sharing from a physical perspective [9]. Criteria include the presence and height of barriers along the road, color contrast of the road surface, attributes of public spaces, crosswalks, road markings, traffic lights, guardrails, and standalone streetlights. More traffic signs indicate a greater separation between people and vehicles, resulting in a lower sharing coefficient and vice versa (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Shared-Space Rating Criteria. Source: UK Department for Transport (2010) [9].

According to Karndacharuk, Wilson et al. [2], the design principles of shared streets can be categorized into two groups: one focuses on traffic calming and prioritizing pedestrians through physical measures, while the other, known as shared-space design, prioritizes pedestrians at a psychological level. These approaches are often combined to emphasize the functional features and environmental ambiance of the specific location.

The concept of shared streets has its roots in urban design, but most existing research on the topic comes from the field of transportation. This research has largely focused on technical and safety performance [10,11]. Post-design evaluations have been included for vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and the visually impaired [2,12,13,14]. Additionally, some studies have delved into the social behavior of shared streets. For example, Batista and Friedrich (2022) studied the impact of farmers’ market activities on shared streets [15], and Peters (2017) examined users’ cognition and feelings in shared spaces from the perspective of geo-semiotics [16]. Overall, international studies have primarily concentrated on traffic performance, with some also exploring the social function and behavior of shared streets. However, since the emergence of the concept, socializing effects have been widely addressed [3,17,18], and there have been much fewer studies regarding them.

Research on shared streets in China has focused on the practical application of the concept in various scenarios. This includes the central business district of the city [19], the business office district of the new district [20], and the renewal of old neighborhoods [6,8]. These studies mainly summarize and apply design strategies. Chen (2016) used the example of the Longxing Headquarters Base in Chongqing to introduce a strategy for sharing the streets of commercial streets in a business district that emphasizes the priority of pedestrians [20]. Wang et al. [5] studied the shared space of Anshan New Village in Shanghai and proposed renovation strategies for old residential areas. Wu’s review (2021) on shared streets in China showed that “sharing” encompasses not only the sharing of pedestrians and vehicles on the road but also the sharing of resources, social interaction, and social equity [5]. However, the focus of these studies remains on the development of design strategies. Zhang and Yao (2022) studied the shared street in Chongqing’s commercial center and evaluated its traffic function from the perspective of safety and road priority [19]. In summary, research on shared streets in China has been centered around the induction and application of design strategies, while post-design research has focused on the evaluation of traffic functions. A comprehensive research framework on the socio-spatial perceptions of users on shared streets in China is still lacking.

Researchers are increasingly focusing on shared urban spaces, giving more attention to technical aspects and safety. However, the aspect of social spatiality and placemaking in public urban spaces in China is still lacking [21,22]. Shared areas, where pedestrians and vehicles interact without clear separation, require clearly perceived priorities to ensure safety. Clearly perceived right of way for road users can help avoid conflicts and maintain orderly and safe traffic. Design strategies for shared spaces often involve shared-level pavements, wider sidewalks, improved landscaping, and additional public spaces to enhance the walking experience, promote social interaction, and reduce the environmental impact of motor vehicles. Therefore, road users’ perception of the right of way and their alignment with design strategies are critical for assessing the success of shared-street design from a traffic and public space experience perspective. A comprehensive research framework is necessary to examine road users’ perceptions of the spatial properties, transportation, and social functions of shared streets.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Background

This paper employs geo-semiotics theory as the research framework. Semiotics, rooted in linguistics, studies how humans attach meaning to symbols [23]. At the end of the 19th century, Charles Sanders Peirce expanded the use of semiotics to include the social sciences and built environment sciences. By the end of the 20th century, linguistic landscape emerged as a branch of semiotics. Landry and Bourhis (1997) defined it as “the language on public street signs, billboards, street names, place names, shop signs and public signs of government buildings together constitute the linguistic landscape of a certain territory, region or city group” [24]. Geo-semiotics, on the other hand, combines semiotics and geography, emphasizing the influence of geographical background when analyzing symbols and regarding human actions as a crucial factor linking the two [23]. Geo-semiotics encompasses a wide range of concerns and allows for a variety of analysis methods and objects. In the existing studies [16,23,25,26], environmental elements like urban furniture, plants, and spatial arrangements are considered semiotics. Any placement and organization of elements in a geographical environment is seen as a symbol with a specific meaning. Peters (2017) used geo-semiotics to examine how users interpreted the shared street of St. Olavs Plass in Oslo, Norway [16]. The study focused on the landscape elements as geo-semiotic symbols and observed how users interpreted these symbols. Overall, geo-semiotics covers both concrete and abstract symbols as well as people’s interpretations and perceptions of these symbols, making the scope of research broad and varied [16].

Geo-semiotics study requires a comprehensive analysis of language, space, and human behavior, revealing the coordination and contradiction between various elements. It is often used to analyze “heterogeneous spaces” in cities, such as traditional farmers’ markets in Hong Kong [27], Chinatown in the United States [28], and German Wind Street in Qingdao [29]. Currently, semiotics in China mainly concern the relationship between text and image symbols and their geographical background and spatial environment, similar to linguistic landscape. International studies on geographical semiotics often include the interaction between people, symbols, and the background environment. For example, in the study of Hong Kong farmers’ markets, the author conducted a detailed analysis of the interaction between discourse users and texts [27].

The theoretical framework of geographical semiotics offers a comprehensive understanding of how designers and users perceive shared spaces by integrating “sign”, “environment”, and “behavior”. As shared spaces are often “heterogeneous spaces” not publicly explained or promoted, it is crucial to understand public perceptions through the symbols in use. Examining these spaces from the perspective of geographical semiotics helps us understand how symbols and design elements influence spatial cognition and behavior patterns, thus optimizing design. Importantly, the concepts of “sign”, “environment”, and “behavior” encompass the critical elements involved in the shared-space design, allowing for a thorough examination of their harmonious relationship. This type of comprehensive examination is rarely seen in previous studies on shared spaces, which have primarily focused on traffic function and walking comfort, neglecting cultural expression and social space. By emphasizing cultural symbols and interaction orders, geographical semiotics provides a fuller understanding of shared spaces. Therefore, this study adopts geographical semiotics as its research method to explore the cultural and social dimensions of shared streets, aiming to fill gaps left by previous studies and offer a more holistic view of shared-space design.

3.2. Framework of the Study

This study adopts the geo-semiotics framework used by Peters (2017), dividing the symbolic elements involved in shared streets into visual semiotics, interaction order, and place semiotics [16]. It emphasizes the overall role of these three elements in understanding the geographical characteristics of places. According to Scollon and Scollon (2003), “visual semiotics” are presented by “pictures (signs, images, graphics, texts, photographs, paintings, and all other combinations of these and others) produced as meaningful wholes for visual interpretation” [23], p. 8. In the urban environment, this typically manifests as traffic signs, street signs, advertising, street names, etc. “Interactive order” [30] emphasizes the observation of interactions between people and symbols and the environment, focusing on people’s bodies, material extensions (such as clothes and vehicles), and activities, reflecting their perception and understanding of space. Place semiotics are “huge aggregations of semiotic systems which are not located in the persons of social actors or in the framed artifacts of visual semiotics” [23], p. 8. In the urban environment, this includes all elements of the spatial environment perceived and interpreted by the user, such as buildings, forms, architectural materials, colors, patterns, vegetation, and furniture.

The framework of semiotics helps us observe and understand how users perceive places and symbols within them, often used in post-use analysis and interpretation of place meanings in space design. In China, geographical semiotics has not been widely applied, with existing research primarily focusing on urban linguistic landscapes and paying less attention to human behavior elements. Shared streets are suitable for the study of geographical semiotics because they encompass three interacting factors: symbol and sign, environment, and people. Thus, studying shared streets from the perspective of geographical semiotics can enrich the research experience of Chinese geo-semiotics studies. Furthermore, there is a lack of comprehensive research on the socio-spatial perceptions of users on shared streets, and the geo-semiotics perspective can address this gap. This study aims to comprehensively understand the intentions of urban designers and the perceptions and understandings of space users in Asia regarding “heterogeneous” places, supplementing the application of geo-semiotics theory represented by Scollon and Scollon (2003). Specifically, this paper explores visual semiotics and place semiotics to understand how designers and managers incorporate shared-street design into historic commercial places. Through observation and investigation of “interaction order”, we can understand users’ perceptions of these places even if they are not necessarily aware of the design concept of shared space.

4. Methodology

4.1. Case Study

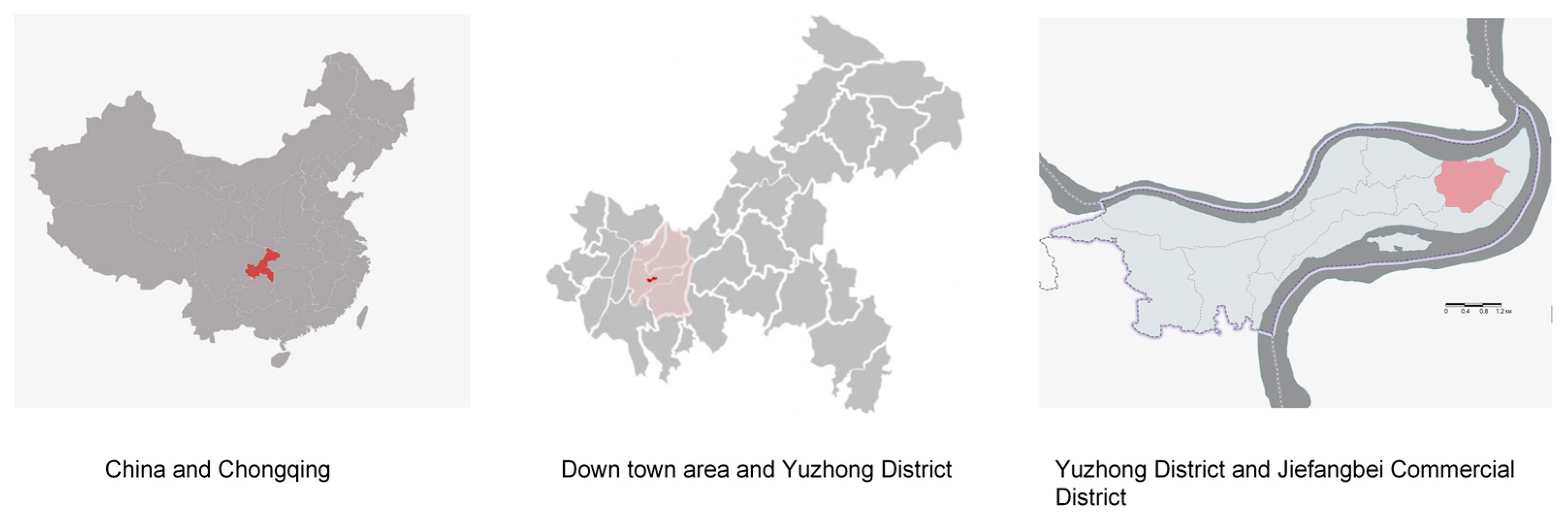

Jiefangbei Business District is located in the historical city center of Chongqing. Figure 2, “Jiefangbei” translates to “the People’s Liberation Monument” in Chinese and represents the oldest high-density commercial core area in Chongqing. A century ago, the Jiefangbei area was known as “Dashizi”, a traditional street lined with Bayu folk houses. Over nearly a hundred years of development, the Jiefangbei area has witnessed significant historical milestones, including the opening of the ports of Chongqing in the late Qing dynasty, modernization during the early Republic of China, the War of Resistance against Japanese aggression, the War of Liberation, the founding of New China, the reform and opening-up period, and the establishment of Chongqing as a directly administered municipality. These stages have left a rich historical and cultural heritage [31].

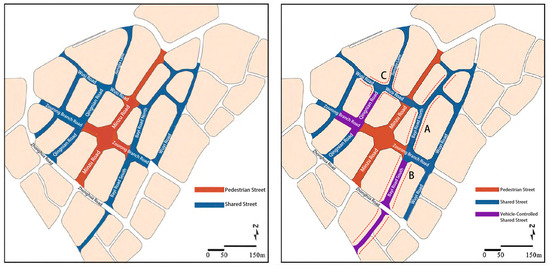

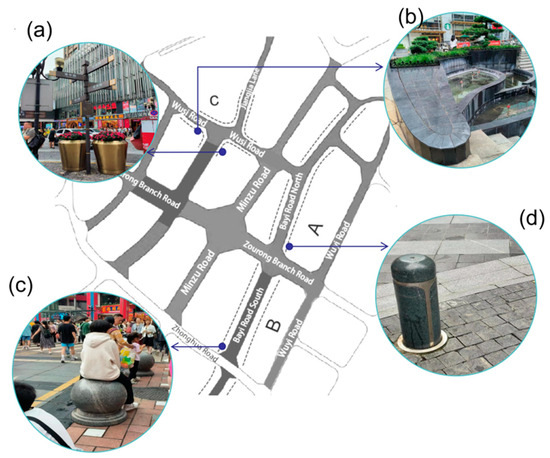

Figure 2.

Location of selected sites. Source: Authors.

In 1997, the local government invested CNY 30 million to transform the 22,400-square-meter Grand Cross area of Jiefangbei into a pedestrian commercial street, resulting in the Jiefangbei Central Shopping Plaza centered around a monument [32]. Located in the city’s core, Jiefangbei intersects three rail lines and connects north and south via four cross-river bridges, with a regional network density exceeding 9 km/km2 [33]. The historical road network, combined with the rapid construction of modern high-rise office and commercial buildings, has resulted in a skyline dominated by skyscrapers. The area has a high population and building density, with frequent commercial activities leading to mixed-use spaces for pedestrians and vehicles. In 2018, Jiefangbei Pedestrian Street was selected as one of the first 11 national pilot projects for pedestrian street transformation and upgrading by the Ministry of Commerce. This project aimed to revitalize the area’s business forms, traffic, and environment. As part of the upgrades, many narrow traditional streets were transformed into shared streets.

Although the concept of “shared streets” is not explicitly proposed in the updates, the existing streets in Jiefangbei clearly integrate road surfaces for both pedestrians and vehicles, with varying degrees of motor vehicle restrictions, exhibiting clear characteristics of shared streets. Compared to other large business districts in China, Jiefangbei has a higher proportion of shared streets, providing an extensive and systematic example of shared streets in a commercial business district within an urban historical context. Despite the large proportion and scale of shared spaces, the concept of “shared space” is not publicly disclosed, which is a key reason for choosing this case study. The city’s decision-makers did not mention “shared space” during the renovation of the Jiefangbei Business District, rendering these areas “heterogeneous” for users. The geographical semiotics method is well suited to exploring whether various symbols in the shared space achieve their design goals. Additionally, as a modern business district emerging in a historic center, integrating cultural resources into street design is a significant research focus of geographical semiotics.

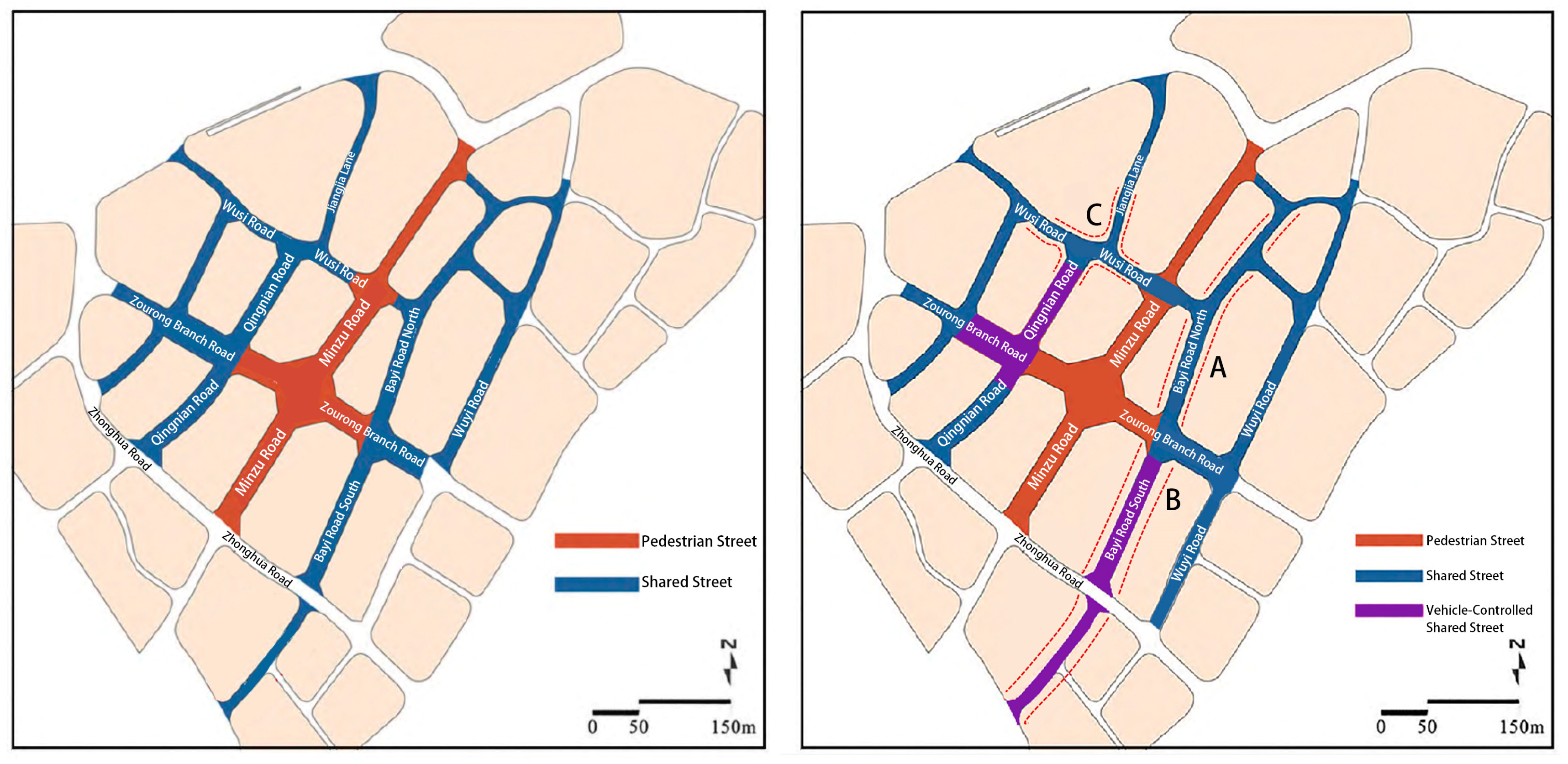

Due to logistical needs, motor vehicle demand, and traffic evacuation functions, Jiefangbei Business District has not been fully pedestrianized. The district now includes both pedestrian-only areas and some streets that allow vehicle access (see Figure 3). By comparing a previous study [19], we can observe the evolution of shared-street management. With the increase of tourists, there are shared streets that restrict the access of some vehicles (Figure 3). Different spatial forms, commercial forms, and traffic flows result in varied design methods for each street.

Figure 3.

Shared street in Jiefangbei Business Street: Before 2022 (Left) and present (Right); A: Northern Section of Bayi Road; B: Southern Section of Bayi Road; C: the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjiaxiang. Source: Authors adapted from Zhang and Yao (2022) [19].

In this study, we selected three cases: the northern section (A) and southern section (B) of Bayi Road and the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjiaxiang (C). The southern section of Bayi Road is a popular food and beverage retail street, the northern section concentrates on commercial office buildings and large shopping malls, and the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjiaxiang hosts retail businesses, hotels, and cultural buildings. These three cases cover almost all major types of shared spaces in the Jiefangbei Business District. The southern section of Bayi Road distinguishes the space for people and vehicles using different pavement colors, while the vehicle and pedestrian space of the northern section of Bayi Road and the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjiaxiang are divided by pavement materials and drainage ditch design. Because the southern section of Bayi Road has more retail and commercial formats, enhancing public space attributes and lacking partition facilities such as bollards and guardrails, the latter two (A and C) have a lower degree of sharing, according to the UK Department for Transport (2010) [9]. The intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjiaxiang, located in the core area of the Jiefangbei Business Circle, represents the intersection design of the business circle, allowing better observation of people’s reactions to shared-street design. The traffic conditions and design methods of the selected cases are analyzed in detail in the survey results.

4.2. Methods and Data

To fully understand the semiotic system of the shared street in the Jiefangbei Business District, this study referenced Peters’ (2017) research method on the shared street of St. Olavs Plass in Oslo [16], Norway and employed three data collection methods: photography, video observation, and questionnaire surveys (See Appendix A and Appendix B). Photos recorded the visual and place semiotics of the street and helped elucidate the designer’s cognition and understanding of shared streets through image and text analysis. Video observation and questionnaire surveys explored the interactive order of street users. These three approaches complemented each other to provide a comprehensive perspective.

The photo shoot included all elements of visual semiotics and place semiotics. According to the two concepts mentioned in the “theoretical framework”, the “visual semiotics” of Jiefangbei’s shared street cover various traffic signs, street sign characters, and their colors, materials, and patterns on the street. “Place semiotics” include the physical elements of the street environment, such as paving, furniture, and vegetation. Photos were taken on a sunny day in June 2023 to cover non-repetitive visual and place elements. Image and text analysis focused on understanding the intentions of urban decision-makers and designers.

The layout of the streets is mainly characterized by stone blocks, lamps, and flowerpots, so there is not much in the way of street furniture, and there is less interaction between users and navigation signs. Consequently, video observations were conducted to better understand how pedestrians, vehicles, and street space interact on a shared street. For the three street cases, we chose street intersections for video shooting to maximize understanding of human–vehicle interaction. To ensure comprehensive and representative research results [34], 10-min videos were recorded in the early morning when pedestrian numbers were low and in the evening when pedestrian numbers were high in order to analyze general rules and special circumstances without disturbing the observers [35].

The questionnaire, designed without mentioning the concept of “shared street”, aimed to understand respondents’ perceptions of social interaction and traffic functions, supplementing the information on interactive order. It includes structured single- and multiple-answer questions, evaluation-scale questions, and two non-mandatory open-ended questions. On-site observation provides more intuitive answers than questionnaires, so to enhance the efficiency of questionnaires and respondent participation, the design focuses on social activities and traffic cognition issues that cannot be understood through observation alone.

Due to the inability to accurately determine the population proportion using the Jiefangbei Business District as a whole, a random sampling method was applied for data collection. While this method may introduce minor errors, it still can primarily provide a reflection of the user population proportion. Questionnaire data were collected at specific times: During the morning peak, data are collected mainly from surrounding staff; at noon, from all people; in the afternoon, from tourists and retired residents; and in the evening, from tourists and white-collar workers after work. To avoid data bias, only one family member was allowed to participate in the survey. Respondents must be above 18 years old. Additionally, due to the high-density environment and the mountainous landscape of Chongqing [36], there are rarely any bicycles, and the primary users of motorcycles are couriers, who are mostly rural migrants and busy with work [37,38]. Hence, all interviewees are pedestrians. From June to December 2023, questionnaires were randomly distributed to pedestrians or collected from nearby workers during morning, noon, afternoon, and evening rush hours. The collected interview data were transcribed and analyzed and are visually represented throughout the article. Pseudonyms were utilized to safeguard the privacy and anonymity of individuals providing information.

5. Results

5.1. Visual Semiotic

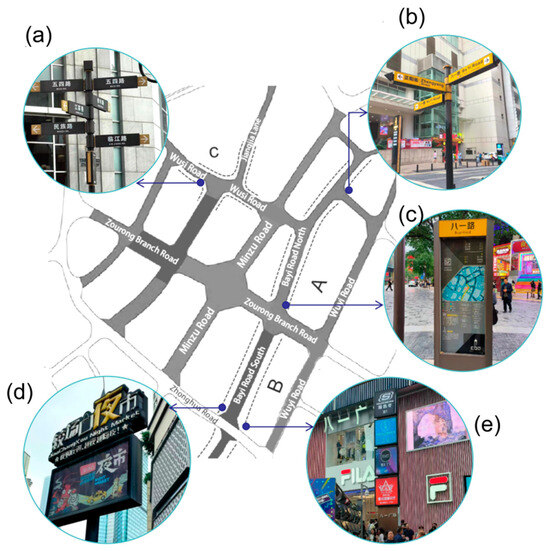

A total of 49 photos featuring text and special symbols were taken for content analysis. These included 22 motor vehicle traffic signs and 27 pedestrian signs. Unlike the common international practice of removing traffic signs, the shared streets of Jiefangbei Business District retain many motor traffic signs. As a tourist destination in Chongqing, Jiefangbei Business District has established road signs with maps to guide pedestrians as part of its pedestrian guidance system.

Vehicle signs fully comply with the provisions of the National Road Traffic Signs and Markings, including red and white no-go signs, no left and right turn signs, white road signs on a blue background, and no parking signs. These traffic signs emphasize that traffic management is independent of other urban design and management, primarily focusing on traffic functions without place significance and social functions.

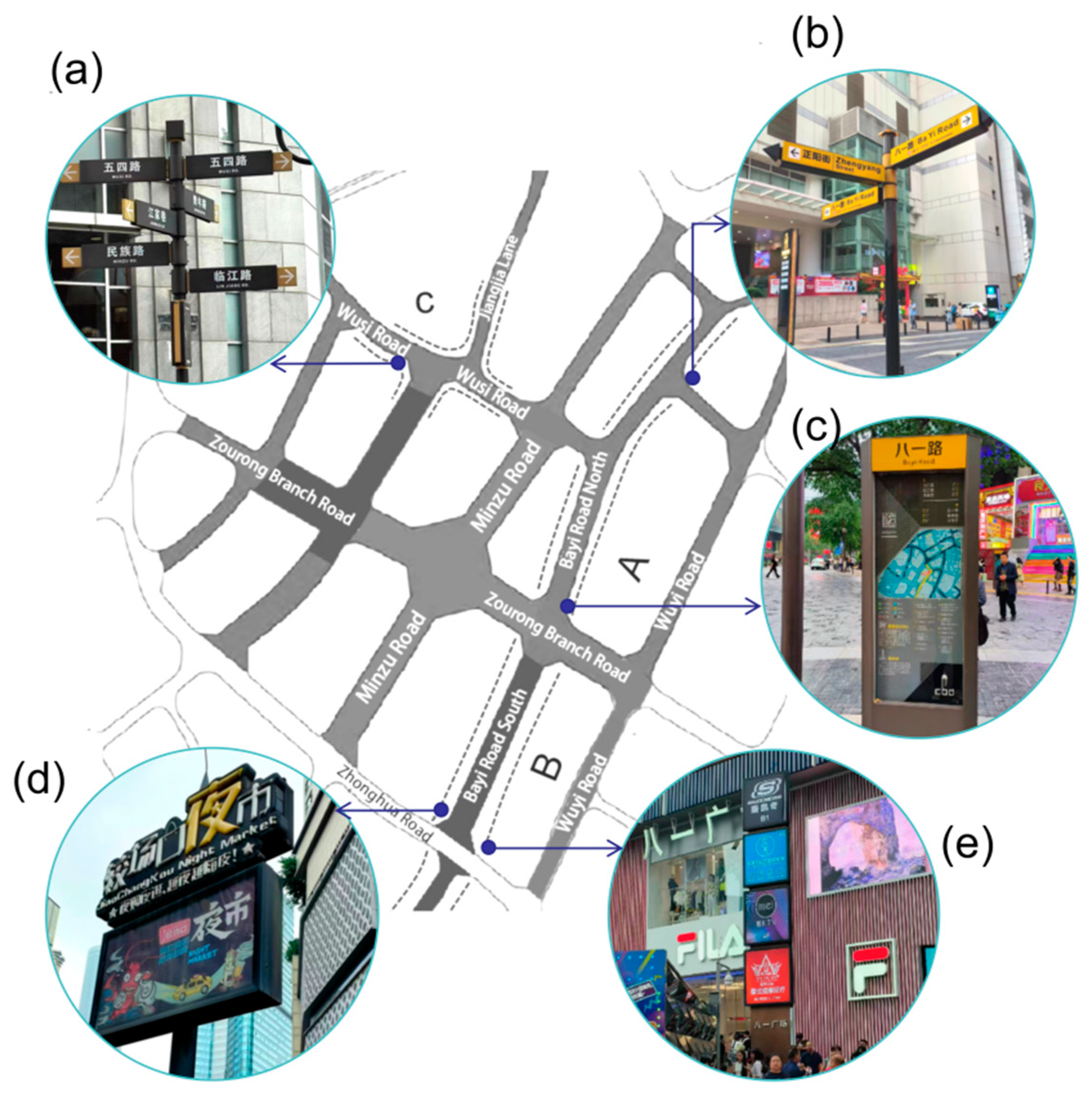

The pedestrian guidance system is more flexible, reflecting color, fonts, text, and image content in its design. The directional signs use large areas of black and yellow, with white characters on a black background with a yellow background sign or black characters on a yellow background, as shown in Figure 4a,b. The font is concise and clear. Informational signs with black, yellow, grey, and blue provide maps, simple drawings of important public buildings, as well as detailed information in white letters on a blue background, as illustrated in Figure 4c. Additionally, there are temporary and non-temporary pedestrian indication systems, such as the cartoon night-market signs and the vertical advertising signs at the entrance of Bayi Road South, illustrated in Figure 4d,e. These guidance systems not only help pedestrians understand important site information but also harmonize with the context and overall atmosphere of the site.

Figure 4.

Different Signs in Shared Streets of Jiefangbei District: (a) a type of directional sign; (b) another type of directional sign; (c) a typical informational sign; (d) specially designed night-market signs; (e) vertical advertising sign. Source: Figure was made, and photographs were taken by the authors.

5.2. Place Semiotic

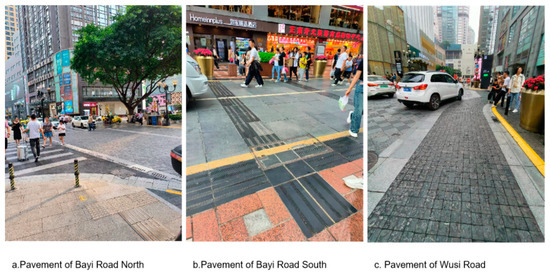

Urban street space is delimited by architectural and landscape design and furniture arrangement on both sides of the street. Jiefangbei Business District is full of high-rise buildings, and due to sunshine, spacing, and fire evacuation needs, the street width of this area is more than 15 m. The three sections of the street have clear functional positioning: the northern section of Bayi Road (A) is for business offices, the southern section of Bayi Road (B) is for snack retail, and the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjia Lane (C) is for large shopping malls, hotels, and cultural facilities. Therefore, this study focuses mainly on paving, lighting, greening, and blocking stones, with less emphasis on building facades.

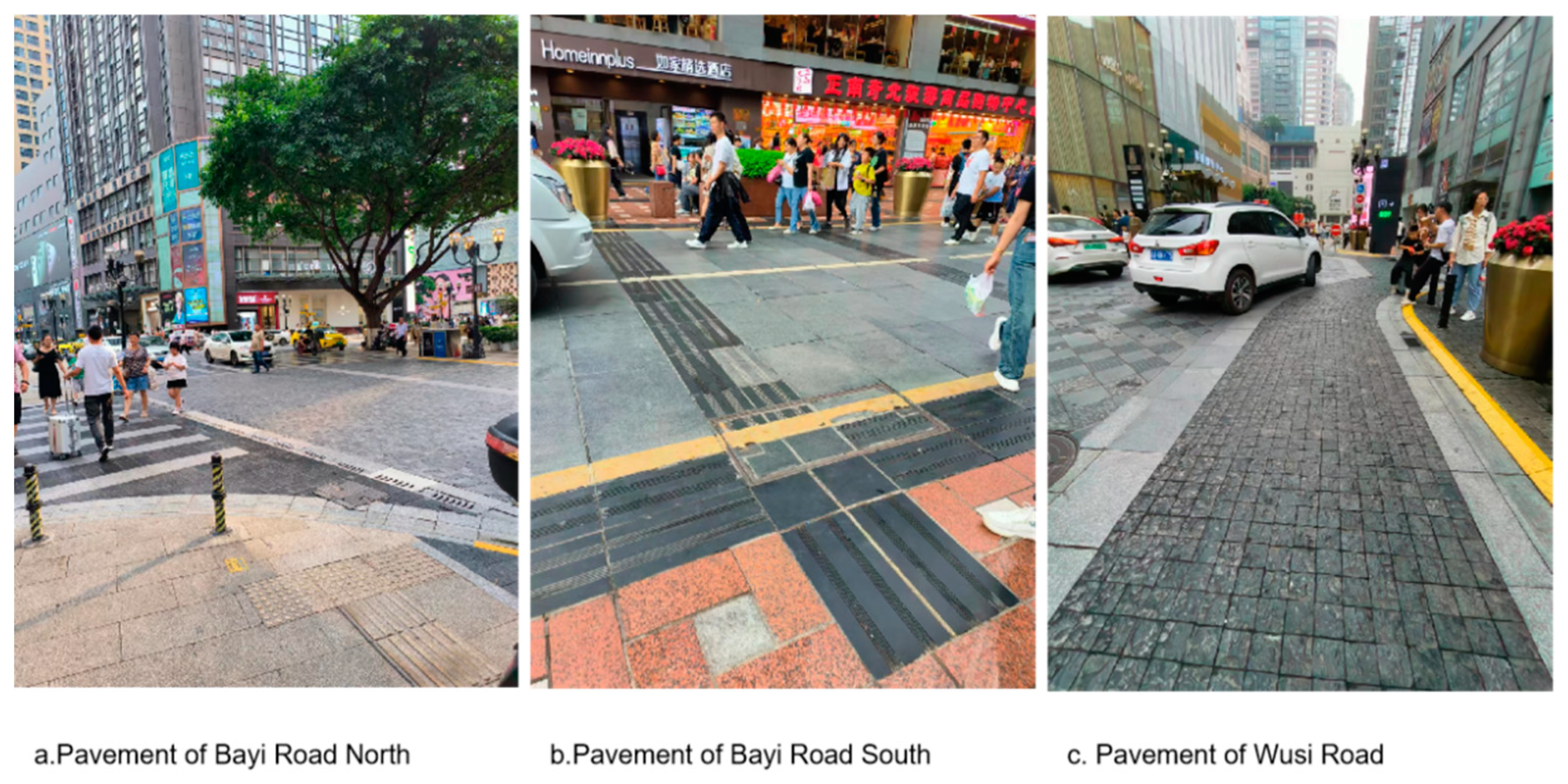

In terms of place symbols, a total of 23 photos were collected. After processing 10 photos with repeated content or overlapping elements of concern, 13 photos were retained. These included one photo of a lamp, six photos of pavement, three photos of vehicle-blocking devices, and three photos of flower beds and pots. The following conclusions can be drawn from the analysis: In pavement design, the north section of Bayi Road, Wusi Road, and Jiangjia Lane divide the space for people and vehicles through differences in material, color, and texture of the ground pavement, or by utilizing median strips and gutters, as shown in Figure 5a,c. The southern section of Bayi Road is divided by strong color contrast and yellow lines, as illustrated in Figure 5b. According to the evaluation criteria of the UK Department for Transport (2010) [9], the southern section of Bayi Road has a high degree of sharing, but to ensure pedestrian safety, the entry of motor vehicles is restricted.

Figure 5.

Pavements of Selected Shared-Street Cases. Source: Photographs taken by the authors.

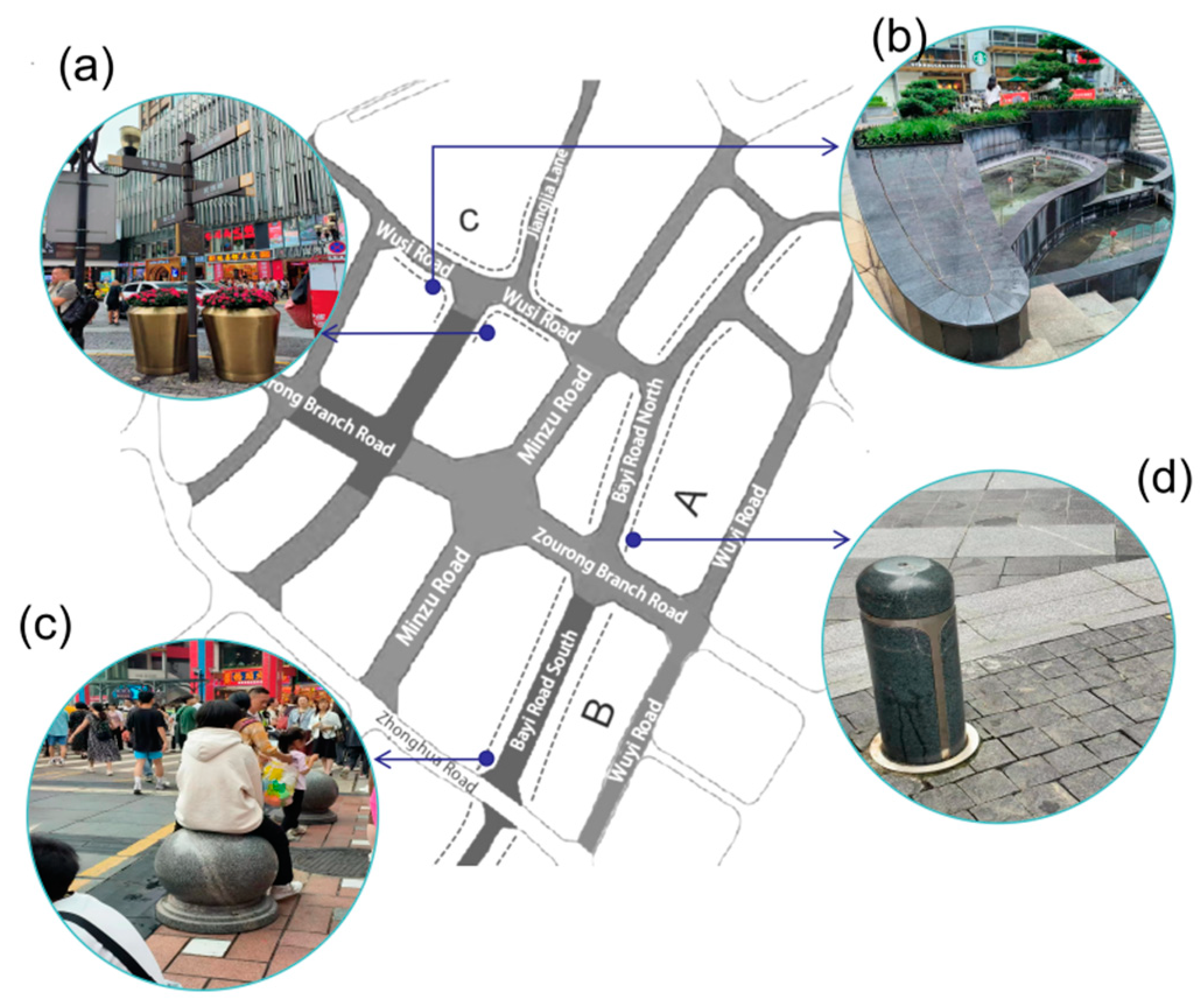

Blocking stones and columns are common elements in the Jiefangbei Business District. Although they reduce the sharing score, they play a decorative role, enhancing the business atmosphere and serving both traffic and social functions. Large flower bowls and various types of lamps also serve a similar role. Metal flower bowls complement the business style of the business circle, while simple street lights combine modern and eclectic styles from the capital period of Chongqing and play a role in blocking vehicles, as shown in Figure 6a. In a high-density urban environment, fixed flower beds and seats combine to achieve complex functions such as space limitation, beautification, and leisure (Figure 6b). The blocking stones of Figure 6c,d in the north and south sections of Bayi Road are mainly placed in areas where vehicles need to be prevented from parking randomly. Due to the lack of necessary recreational facilities, the circular barrier stone also serves as seating. Overall, furniture design and layout in a high-density commercial environment strive to achieve functional composite, space division, place atmosphere, and social activities function.

Figure 6.

Street Furniture of Selected Shared Street Case: (a) a metal flower bowl and a typical street light beside it; (b) fixed flower beds with complex functions; (c) blocking stones were used as seats; (d) blocking columns. Source: Figure was made, and photographs were taken by the authors.

5.3. Interaction Order

The relationship between street users, visual semiotics, and the background environment was collected through observation and questionnaires to understand their perception and understanding of shared space. Video observation at the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjiaxiang Road showed that pedestrians crossing the street are less cautious than on ordinary streets, regardless of whether it is early morning with fewer people or evening peak hours with more people. Most pedestrians cross the street calmly, with some even stopping to check road information or use their mobile phones. During a ten-minute period, only a few people observed the street before crossing, with most choosing to cross directly at slower vehicle-turning points. It is worth noting that the one-way street of Jiangjia Lane and the traffic light control ahead keep vehicle speeds low in this area.

The northern and southern sections of Bayi Road use different shared-street design methods. The southern section (Zorong Road to Ciqi Road) divides space by color and uses traffic signs to restrict vehicle access, prioritizing pedestrian use. The video shows minimal interaction between pedestrians and vehicles, with only two vehicles passing in 10 min. In the northern section (Zorong Road to Wusi Road), the video at the intersection of Bayi Road and Zhengyang Street captures faster vehicle speeds, causing most pedestrians to cross at crosswalks with minimal random crossing or parallel walking. At the intersection, the landscaped and raised pavement leads many pedestrians to cross diagonally rather than using the crosswalks.

5.4. Social Interaction

A total of 200 questionnaires were issued, with 191 valid responses analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Of these, 61 responses were collected from the northern section of Bayi Road (case A), 65 from the southern section of Bayi Road (case B), and 65 from the intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjia Lane (case C). The male-to-female ratio of respondents was 0.89:1. The age distribution was as follows: 50.8% aged 18–29, 27.2% aged 30–45, 14.1% aged 46–59, and 7.9% over 60. Non-local tourists accounted for 46.1%, nearby residents 8.4%, local tourists 25.1%, and nearby staff 20.4%. The high proportion of tourists, especially young ones, is notable. This is consistent with Chongqing being named one of the top ten tourist destinations in China for summer 2023 [39]. In 2023, Chongqing attracted a total of 103 million tourists [40], with Jiefangbei being a top tourist destination. During the summer survey period, the abundance of tourists, particularly university students, was evident. Our observations confirmed the high proportion of non-local tourists in Jiefangbei, who were often heard speaking Mandarin or distinct regional dialects.

The average scores of the social willingness scale for the three groups were 2.20, 2.46, and 2.66 (variances were 0.91, 0.95, and 0.83, respectively). Although overall social willingness was low (between 2.0, less willing, and 3.0, neutral), it varied due to differences in street scale. The northern section of Bayi Road (A) had the lowest social willingness due to the low sharing rate, narrow pedestrian space, lack of leisure facilities, and its surroundings of less-accessible office buildings and large shopping malls with low-permeability facade design. The intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjia Lane (C) had the highest social willingness, with wide space, seating, and open dining. Three respondents mentioned that seating, weather, shade from trees, and photo-worthy locations influence their social willingness (Table 1).

Table 1.

Responses regarding the factors influencing users’ social willingness. Source: Collected by authors.

Through the SPSS Explore analysis, the study further examined the relationship between respondents’ age and identity and their communication intentions (Table 2). The average social willingness scores for different age groups in the northern section of Bayi Road (case A) were 2.16 (18–29), 1.91 (30–45), 2.11 (46–59), and 3.8 (60+). In the southern section of Bayi Road (case B), the scores were 2.32 (18–29), 2.57 (30–45), 2.6 (46–59), and 3.0 (60+). At the intersection of Jiangjia Lane and Wusi Road (case C), the scores were 2.57 (18–29), 2.67 (30–45), 2.88 (46–59), and 2.83 (60+). These data indicate that age impacts social willingness, especially in the northern section. This may be due to younger people’s tendency to follow habitual travel patterns, resulting in lower social willingness. Since the sample had fewer respondents aged 60+ and more aged 18–45, the overall social willingness values may be skewed lower. The analysis also compared social willingness among users with different identity types but found no significant differences.

Table 2.

Cross-study the perceived safety level of the age groups and identity types in three cases. Source: authors.

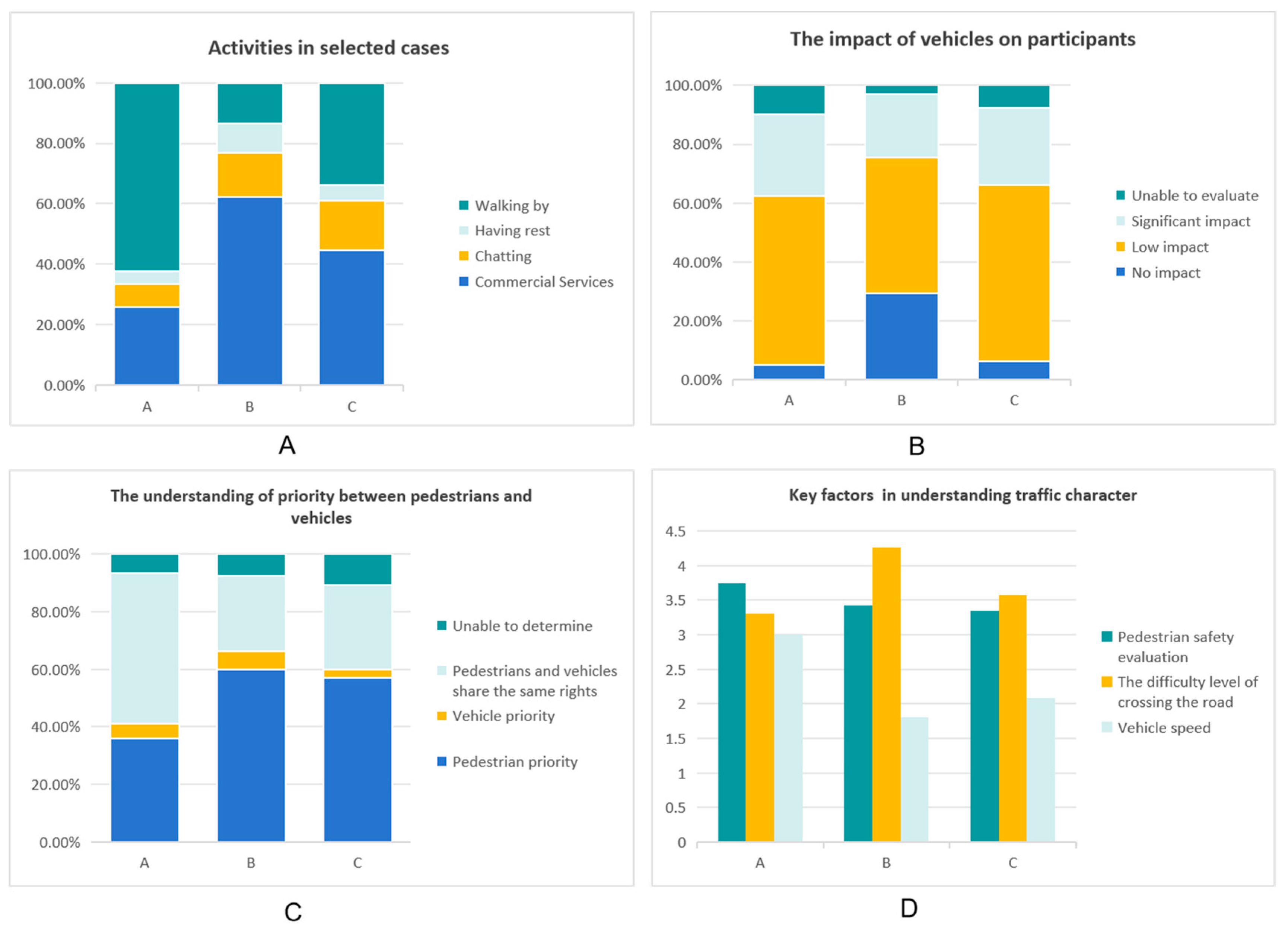

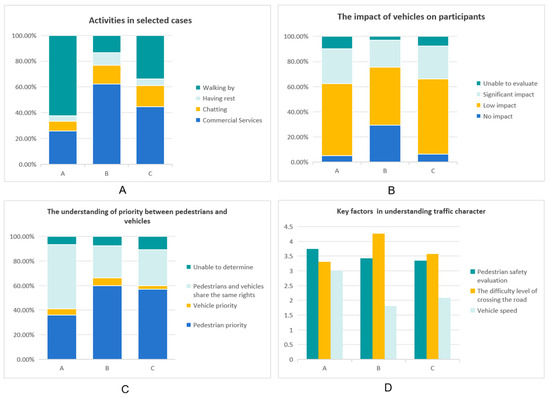

Activity types and proportions are shown in Figure 7a. The stacking map indicates less social chatting and resting in all three cases. In the northern section of Bayi Road (A), 62.4% of respondents were just passing through, while in the southern section (B), a leisure-catering tourist destination, 62.2% engaged in commercial service activities. At the intersection of Jiangjia Lane and Wusi Road (C), 33.7% were just passing through, and 44.6% engaged in commercial service activities. This could be biased by the timing of the questionnaire collection, which was when many participants had just come out of a nearby drink shop.

Figure 7.

Social-function and Traffic-function Analysis for Selected Cases: (A) the percentage of activities; (B) the impact of vehicles on participants; (C) street users’ understanding of priority; (D) key factors in understanding traffic character. Source: Authors.

Overall, all three cases correspond to low social willingness, with basic activities primarily involving walking through and purchasing commercial services. The low levels of spontaneous activities suggest that the current shared streets still have significant potential for improvement in urban design, particularly in terms of adding leisure facilities and greening.

5.5. Traffic Experiences

Regarding the impact of vehicles on walking activity, 29.2% of people on the southern section of Bayi Road (B) believed it had “no impact”, which is higher than the other two sections due to vehicle traffic control. More than or close to 50% of respondents in all three sections believed vehicles had a low impact on people (Figure 7B). Regarding “priority for people and vehicles”, more than 52.5% of people in the northern section of Bayi Road (A) chose “equality for people and vehicles” compared to 36.1% choosing “priority for pedestrians”. More than half of the southern section of Bayi Road (B) and the Wusi Road-Jiangjia Lane intersection (C) believed in “pedestrian priority” Figure 7C). The Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant correlation between the data of the three groups and the way of arrival (p-values were 0.539, 0.139, and 0.477, respectively).

Respondents rated the shared street as “somewhat safe” in the three sections, with safety evaluations of 3.72, 3.42, and 3.34, respectively. The southern section of the road (B) scored 4.26 in the difficulty level of crossing the road, which is higher than the other two sections (3.31 and 3.37), generally considered “not too strenuous” to “not strenuous at all”. In terms of vehicle speed perceived by pedestrians, the average speed for the northern section of Bayi Road (A) was 3 (neutral), while the speeds for case B and case C were considered “somewhat slower” (1.8, hot, and 2.08, just through), consistent with previous video observations.

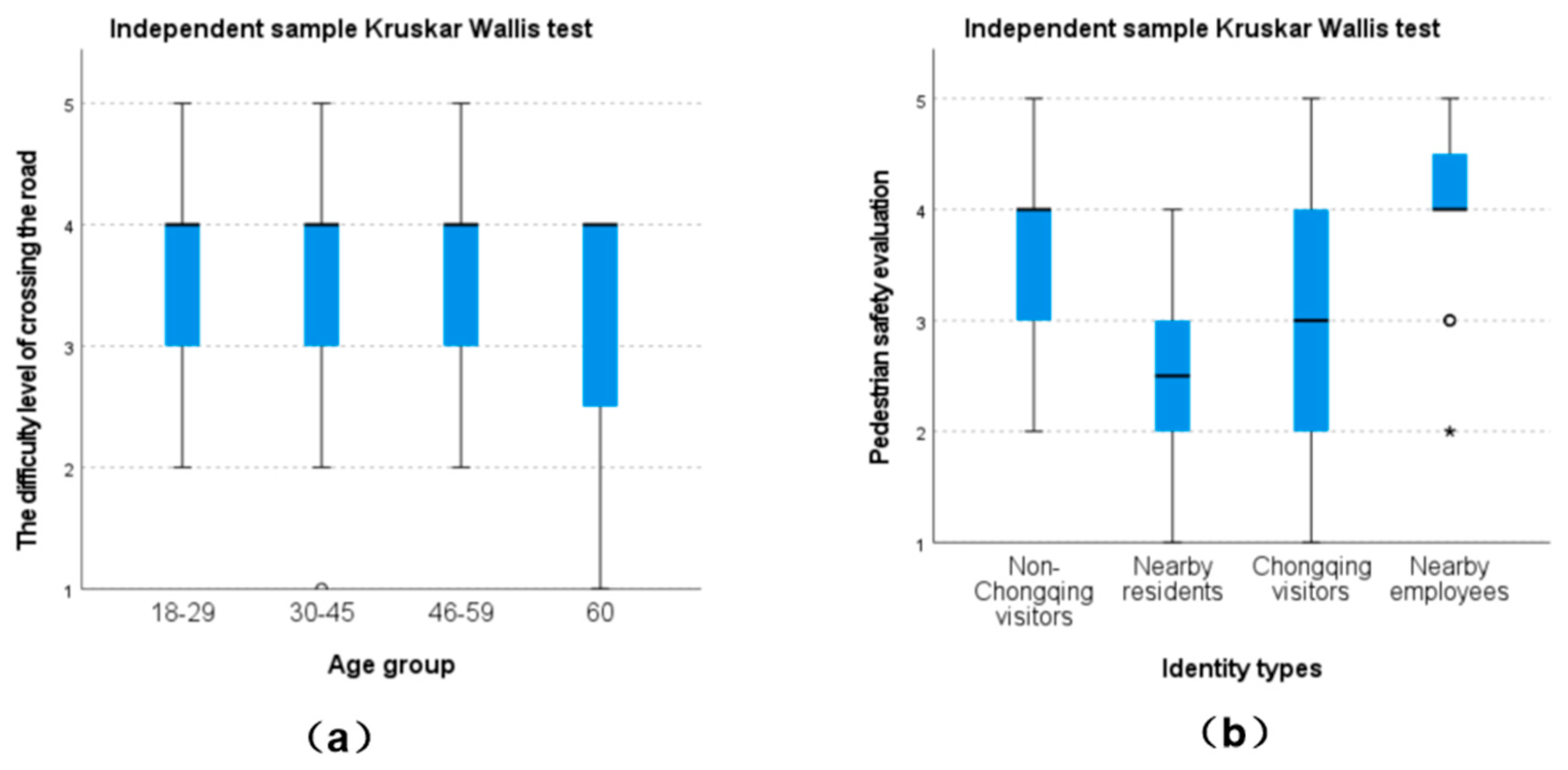

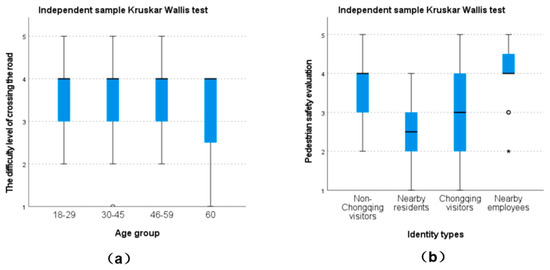

To explore the performance of streets with different levels of sharing in terms of safety and effectiveness, this study examined the relationship between pedestrians’ perception of the right of way and the safety and effectiveness of shared streets. The Kruskal–Wallis test found no significant correlation between the perceived right of way and respondents’ perceived safety and road crossing difficulty (p-values were all greater than 0.05). This indicates that in the Jiefangbei Business District, pedestrians’ perception of their priority right of way does not determine psychological safety and has no direct relationship with the difficulty of crossing the road. Further analysis showed that the psychological safety of pedestrians was correlated with age (p = 0.037), particularly between ages 60+ and 18–29 (p = 0.009) and between ages 60+ and 30–45 (p = 0.011). Therefore, since a large proportion of the interview sample includes young people, the overall psychological security score of respondents may be higher due to the unbalanced age distribution of the sample. However, age had no significant effect on the ease of crossing the road (p = 0.074) (Figure 8a), as the low speed of vehicles in cases B and C and zebra crossing in case A minimized differences. The identity of participants was significantly correlated with the sense of security (p < 0.001), with nearby workers feeling the safest, followed by non-local tourists, local tourists, and nearby residents (Figure 8b). However, this difference was mainly caused by age, as 89.8% of non-local tourists were 18–45 years old, 70.8% of local tourists and 77.0% of nearby employees were 18–45 years old, and only 37.5% of nearby residents were 18–45 years old.

Figure 8.

Relationships between people’s age, identity types, and their perceptions of traffic-related questions: (a) how different age groups perceived the difficulty level of crossing the road; (b) how people with different identity types perceived pedestrian safety. Source: Authors.

The relationship between perceived vehicle speed and the ease of crossing the road and pedestrians’ perceived walking safety was also investigated. Spearman’s test showed a correlation only in the northern section of Bayi Road (p = 0.001 and 0.002, respectively). This is because the actual and perceived speed of the other two cases is already very low; safety and ease of crossing the road are more affected by individual differences such as age than by vehicle speed; and the northern section of Bayi Road (A), with the lowest sharing degree, clearest right-of-way separation, and faster speed, shows a significant correlation. In the non-compulsory open-ended question “Why?” following “Who do you think should have priority on the road, people or cars?”, three respondents who selected “people” explained that their preference came from slower speed of vehicles, while two suggested pavement integration, stating “because cars drive on pavements similar to sidewalks” (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reasons that users think the cases are pedestrian-oriented. Source: Authors.

From the analysis of traffic experience, it is evident that with reasonable planning, both low-speed, high-sharing street spaces and higher-speed, lower-sharing streets with clearer right-of-way management can achieve relatively high safety and effectiveness scores. User age has a more significant impact on the perception of street safety compared to user identity, which implies familiarity with the street. To improve pedestrian priority, effective place symbols include integrated pavement design and maintaining obvious low vehicle speeds.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Shared streets represent a spatial design paradigm that has gained popularity since the 1960s, emphasizing the combination of urban design and traffic engineering to enhance pedestrians’ rights to use the road. Through urban design techniques, more “shared” streets tend to reduce motor vehicle speed and increase pedestrians’ psychological sense of entitlement to the right of way [2]. This design is widely used in commercial blocks and residential renewal projects worldwide despite questions about its safety and walking comfort. From a geographical semiotics perspective, this study comprehensively investigated the “visual semiotics”, “place semiotics”, and “interaction order” of users in the shared streets of Chongqing’s Jiefangbei Business District to fully understand the design intentions and user perceptions. The research methods included photo content analysis, video observation, and questionnaire surveys, presenting the actual use of shared streets from multiple perspectives. The main conclusions of this paper are as follows:

- From the perspective of visual semiotics, the shared street design at Jiefangbei is a collaborative effort between traffic engineering and urban design. Traffic signs ensure basic safety, while the pedestrian guidance system enhances the city’s image. Managing vehicles by retaining and strengthening traffic signs indicates that, in China’s high-density urban environments, designers still view traffic signs as crucial for ensuring the safety of shared spaces. The southern section of Bayi Road, which features casual dining and snack vendors, restricts vehicle access through traffic signs to ensure pedestrian convenience and safety. This demonstrates that shared space is not only a design tool but also a management tool that is adjusted according to actual needs;

- From the perspective of place semiotics, the design strategies of shared streets in the Jiefangbei Business District incorporate common shared-space design techniques, emphasizing the consistency and strong correlation of pavement in both pedestrian and vehicle spaces. This has proven to be one of the most effective means of making people perceive the priority of pedestrians. Additionally, landscape furniture is designed as functional composites with styles that reflect the business atmosphere and historical context. This dual approach achieves both traffic management and placemaking purposes simultaneously;

- From the perspective of interaction order, the performance of Jiefangbei’s shared street as a public space in stimulating spontaneous activities is insufficient. In high-density urban environments, shared streets require more greenery and recreational facilities to fulfill their social functions. In terms of traffic interaction, the level of sharing does not determine the perceived safety and effectiveness of the street. However, pedestrians’ perceived sense of security is influenced by individual differences such as age. In areas with higher street-sharing design attributes, like the southern section of Bayi Road, most vehicles are restricted from entering. Conversely, in areas with weaker sharing, like the northern section of Bayi Road, a well-established traffic sign system ensures pedestrian crossings, making people feel relatively safe regardless of their priority level.

The significance and importance of this study lie in comprehensively understanding urban designers’ intentions and space users’ perceptions and understandings of “heterogeneous” places in Asia from the perspective of geographical semiotics, supplementing the application of Scollon and Scollon’s (2003) theory [23]. The study expands on the linguistic landscape of Asian studies, which have focused on culturally “heterogeneous” regions or tourist spaces [27,41,42] and linguistic symbol systems in media and digital spaces [43,44]. By incorporating human “interaction order” as a key research element and understanding “place” as semiotics, this study addresses deficiencies in Asian and Chinese geographical semiotics. Observing and analyzing people’s behavior patterns in shared spaces reveals their actual feelings and reactions in these “heterogeneous spaces”, providing a new perspective for applying geographical semiotics theory. Additionally, this study improves the overall evaluation of the social and transportation functions of shared spaces, filling a research gap in China where most existing studies focus on traffic safety and walking comfort. Exploring shared space’s comprehensive functions from a broader perspective provides a more holistic evaluation method. The results of this study have important implications for urban planning and street design. By analyzing the shared street in the Jiefangbei Business District, the research provides an empirical basis for shared-street design in high-density urban environments. These conclusions can be applied not only to street renovation in Chongqing but also as a reference for shared space design in other major Chinese cities.

Based on the study results, we recommend that future strategies for shared-street design consider traffic management, spatial planning, and social functions to improve street-use efficiency and safety through reasonable design and management measures. Designers should not aim to maximize the street “sharing” level as the ultimate goal of regeneration. Instead, they should base decisions upon comprehensive functional needs, such as whether to remove all traffic signs or completely eliminate the spatial division between pedestrians and vehicles. In designing street furniture, especially in high-density urban centers, it is crucial to consider the multifunctional use of items such as seats and lamps, ensuring they meet spatial and functional requirements. The readability of the visual identification system should be combined with the shaping of the environmental atmosphere and cultural themes. Emphasizing the needs of pedestrians in street design, particularly by adding greenery and leisure facilities, can enhance the overall social function. This approach can transform shared spaces into areas primarily serving pedestrians rather than negative spaces where people and vehicles are forced to mix. These suggestions require designers to integrate “visual semiotics” and “place semiotics” to control the degree of sharing and enhance the spontaneous and necessary activity experiences of pedestrians.

This research has limitations, particularly concerning the interaction between people and the environment. It also includes the high proportion of tourists in the sample, especially young tourists, who may have influenced the evaluation of social willingness and psychological safety. However, this sample proportion, to some degree, reflects the real use of shared space in the Jiefangbei Business District and provides useful suggestions for transforming shared streets in historic central business districts with developed tourism industries.

Future studies should consider research methods based on population proportion to enhance the universality of conclusions. This study highlights shared streets as a “process” that needs to adapt to different times and environmental conditions. Future research could examine the adaptive design of shared spaces over a longer time span and explore more diverse scenarios, such as commercial blocks, residential areas, and tourist attractions of various sizes, to verify and extend this study’s conclusions. Comparative studies of shared streets in different countries and regions can also reveal similarities and differences in shared-space design across cultural backgrounds, providing valuable insights into global shared-street design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.; methodology, J.C. and W.H.; software, J.C. validation, J.C.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, J.C.; resources, J.C.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and W.H.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, W.H.; project administration, J.C. and W.H.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Bureau of Guangzhou Municipality, grant number [2023A04J1639], And The APC was funded by Junli Chen.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the privacy of the respondent’s identities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Dear Sir/Madam,

To provide relevant data for the improvement and renovation of future urban streets, we kindly invite you to participate in the following survey. Thank you for taking the time to complete it amidst your busy schedule.

Best regards,

Section One: Basic Information

(1) Gender: ☐Male ☐Female

(2) Age: ☐18–29 ☐30–45 ☐46–59 ☐60+

(3) Your mode of transportation to this location:

☐Walking ☐Subway ☐Bus ☐Taxi/ride-sharing service ☐Driving

(4) You are

☐Non-local tourist ☐ Nearby resident ☐Local tourist ☐Nearby staff

Section Two: Street Social Interaction

(1) Activities on the street (select all that apply)

☐Commercial services (eating and drinking, etc.) ☐Socializing

☐Resting ☐Just passing through

(2) Are you willing to engage in social activities on the street?**

☐1 Unwilling ☐2 Somewhat unwilling ☐3 Neutral ☐4 Somewhat willing ☐5 Willing

(3) The reason for your answer to the previous question (optional):

Section Three: Pedestrian and Vehicle Interaction

(1) Compared to purely pedestrian areas, how do vehicles affect you?

☐No effect ☐Minor effect ☐Significant effect ☐Unable to evaluate

(2) In terms of walking experience, how would you rate the safety of the street?**

☐1 Unsafe ☐2 Somewhat unsafe ☐3 Neutral ☐4 Somewhat safe ☐5 Safe

(3) Do you find it difficult to cross the street?

☐1 Very difficult ☐2 Somewhat difficult ☐3 Neutral ☐4 Not very difficult

☐5 No difficulty, similar to a pedestrian street

(4) Vehicle speed

☐1 Slow ☐2 Somewhat slow ☐3 Neutral ☐4 Fast ☐5 Very fast

(5) Who do you think has the priority of the right of way on the street?

☐Pedestrians priority ☐Vehicles priority ☐Equal right of way ☐Unable to determine

(6) The reason for your answer to the previous question (optional):

Thank you for your participation!

Appendix B. Questionnaire Results:

Table A1.

Characteristics of participants.

Table A1.

Characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics of Participants | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 90 | 47.1 |

| Female | 101 | 52.9 | |

| Age Group | 18–29 | 97 | 50.8 |

| 30–45 | 52 | 27.2 | |

| 46–59 | 27 | 14.1 | |

| 60+ | 15 | 7.9 | |

| Data Collection Location | Bayi Road North | 61 | 31.9 |

| Bayi Road South | 65 | 34 | |

| Intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjia Lane | 65 | 34 | |

| Identities of Participants | Non-local tourist | 88 | 46.1 |

| Nearby resident | 16 | 8.4 | |

| Local tourist | 48 | 25.1 | |

| Nearby staff | 39 | 20.4 | |

| Mode of transportation to this location | Walking | 50 | 26.2 |

| Subway | 87 | 45.5 | |

| Bus | 14 | 7.3 | |

| Taxi/ride-sharing service | 33 | 17.3 | |

| Driving | 7 | 3.7 |

Table A2.

Social Interaction.

Table A2.

Social Interaction.

| Data Collection Location | Social Willingness | Activity Types | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Variance | Commercial Services | Socializing and Chatting | Taking Rest | Just Walking Pass | |||||

| Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | Number | Proportion | |||

| Bayi Road North | 2.20 | 0.91 | 24 | 25.80% | 7 | 7.50% | 4 | 4.30% | 58 | 62.40% |

| Bayi Road South | 2.46 | 0.95 | 51 | 62.20% | 12 | 14.60% | 8 | 9.80% | 11 | 13.40% |

| Intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjia Lane | 2.66 | 0.83 | 41 | 44.60% | 15 | 16.30% | 5 | 5.40% | 31 | 33.70% |

Table A3.

Traffic experience of pedestrians.

Table A3.

Traffic experience of pedestrians.

| Bayi Road North (A) | Bayi Road South (B) | Intersection of Wusi Road and Jiangjia Lane (C) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||||

| Impact from vehicles on shared street | No impact | 3 | 4.9 | 19 | 29.2 | 4 | 6.2 | ||

| Minor impact | 35 | 57.4 | 30 | 46.2 | 39 | 60 | |||

| Significant impact | 17 | 27.9 | 14 | 21.5 | 17 | 26.2 | |||

| Unable to evaluate | 6 | 9.8 | 2 | 3.1 | 5 | 7.7 | |||

| Total | 61 | 100 | 65 | 100 | 65 | 100 | |||

| Priority of the right of way | Pedestrian priority | 22 | 36.1 | 39 | 60 | 37 | 56.9 | ||

| Vehicle priority | 3 | 4.9 | 4 | 6.2 | 2 | 3.1 | |||

| Equal right of way | 32 | 52.5 | 17 | 26.2 | 19 | 29.2 | |||

| Unable to determine | 4 | 6.6 | 5 | 7.7 | 7 | 10.8 | |||

| Total | 61 | 100 | 65 | 100 | 65 | 100 | |||

| Descriptive statistics | N | Mean | Variance | N | Mean | Variance | N | Mean | Variance |

| Pedestrian safety assessment | 61 | 3.74 | 0.874 | 65 | 3.42 | 1.13 | 65 | 3.34 | 1.122 |

| Perceived crossing difficulty | 61 | 3.31 | 0.867 | 65 | 4.26 | 0.713 | 65 | 3.57 | 0.77 |

| Perceived speed of vehicle | 61 | 3 | 0.856 | 65 | 1.8 | 0.814 | 65 | 2.08 | 0.777 |

References

- Hamilton-Baillie, B. Towards shared space. Urban Des. Int. 2008, 13, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karndacharuk, A.; Wilson, D.J.; Dunn, R. A review of the evolution of shared (street) space concepts in urban environments. Transp. Rev. 2014, 34, 190–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-Baillie, B. Shared space: Reconciling people, places and traffic. Built Environ. 2008, 34, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.G.; Shen, S.F. Research on the spatial transformation of shared streets in old neighborhoods from the perspective of urban renewal: A case study of Anshan Road, Heping District, Tianjin. Art Des. 2022, 2, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.Y. Research on the spatial environment indicator system and design guidelines for shared streets. In Proceedings of the 2020 China Urban Planning Annual Conference, Chengdu, China, 25–27 September 2021; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.F.; Pan, L.F.; Shen, L.Z. Research and practice on the spatial transformation of old city streets based on the sharing concept: A case study of the renovation of Dafu Road, Fuyang District, Hangzhou. Chin. Overseas Archit. 2019, 3, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.Y.; Jiang, L.H.; Zeng, R.L.; Lin, R. Street design for shared use by pedestrians and vehicles: Notes from the Lujiazui Central Business District street design workshop. Planners 2015, 31, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.C.; Wang, S.S.; Liu, J.R. A preliminary exploration of the adaptability of shared (street) space theory in the renewal of old residential areas: A case study of the renewal of Anshan New Village, Shanghai. Hous. Sci. 2022, 42, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- UK Department for Transport. Designing the Future. Shared Space: Operational Assessment; Department for Transport: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, S.; Melia, S. Shared space: Research, policy, and problems. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Transp. 2014, 167, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R.; Kumar, M. The impact of shared spaces on the mobility of disabled people. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 573–594. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Apilánez, B.; Karimi, K.; García-Camacha, I. Shared space streets: Design, user perception and performance. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2017, 143, 05017004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkekas, F.; Bigazzi, A.; Gill, G.S. Perceived safety and experienced incidents between pedestrians and cyclists in a high-volume non-motorized shared space. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 4, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, H.; Wallén, A.; Andersson, J.; Patten, C. Shared space: Different age groups’ perspectives. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 90, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.; Friedrich, B. Investigating spatial behaviour in different types of shared space. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S. Sharing space or meaning? A geosemiotic perspective on shared space design. Appl. Mobilities 2019, 4, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwicht, D. Mental Speed Bumps: The Smarter Way to Tame Traffic; Envirobook: Sussex Inlet, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, E.; Monderman, H.; Hamilton-Baillie, B. Shared space: The alternative approach to calming traffic. Traffic Eng. Control. 2006, 47, 290–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Yao, D. Research on the application of shared (street) space in the renewal of old city commercial streets: An empirical investigation based on Bayi Road in Chongqing. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2022, 2, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Research on Pedestrian-Priority Commercial Street Landscape Design Strategies: A Case Study of the Longxing Headquarters Base Commercial Street Landscape Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Huang, Y. Does public rental housing foster social ties? A study of the everyday social lives of rural migrants in Chongqing, China. Urban Geogr. 2024, 1–24, online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ye, N. The emerging peri-urban landscape of modern public rental housing towers in China: A case of Chongqing. City 2024, 1–14, online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollon, R.; Scollon, S.W. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, R.; Bourhis, R.Y. Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 16, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, A.; Thurlow, C. (Eds.) Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space; Continuum: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M.; Lawrence-Zúñiga, D. (Eds.) The Anthropology of Space and Place: Locating Culture; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, J.J. Spaces of consumption and senses of place: A geosemiotic analysis of three markets in Hong Kong. Soc. Semiot. 2017, 27, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.J. Revitalizing Chinatown into a heterotopia: A geosemiotic analysis of shop signs in Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown. Space Cult. 2007, 10, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. Research on the linguistic landscape from the perspective of semiotics. Cult. Ind. 2022, 21, 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Pelican Books: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Study on the protection and inheritance of historical culture in the renovation of Jiefangbei Pedestrian Street in Chongqing. Zhejiang Archit. 2023, 40, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chongqing Business Daily. Jiefangbei CBD: The “Heart” of Chongqing’s Economy. Sina. Available online: https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2006-06-17/05159224592s.shtml (accessed on 17 June 2006).

- Liu, L. Exploration and practice of planning in the renovation of Jiefangbei Pedestrian Street in Chongqing. Urban J. 2024, 45, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Selltiz, C.; Wrightsman, L.S.; Cook, S.W. Research Methods in Social Relations, 3rd ed.; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, W. Satisfaction Evaluation and Renewal Strategies for Urban Parks Based on the Importance–Performance Analysis: A Case of Shaping Park in Chongqing, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. Motivations and barriers in becoming urban residents: Evidence from rural migrants living in public rental housing in Chongqing, China. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 45, 1804–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. Housing and occupational experiences of rural migrants living in public rental housing in Chongqing, China: Job choice, housing location and mobility. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2023, 45, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Z. 2023 Summer Travel Report Released: Chongqing’s Popularity Ranks in the Top Ten Nationwide. Baidu. 2023. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1775246037936941686&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Chongqing Municipal Development Committee of Culture and Tourism. 2023 Chongqing Tourism Industry Statistical Bulletin. Technology and Big Data, Division. 2024. Available online: https://whlyw.cq.gov.cn/wlzx_221/sjfb/202404/t20240425_13156888_wap.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Tan, P.K.W. Language in Singapore: From multilingualism to English. Asian Englishes 2014, 16, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huebner, T. Bangkok’s linguistic landscapes: Environmental print codemixing language change. In Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism; Gorter, D., Ed.; Multilingual Matters: Clevendon, UK, 2006; pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.Y. Critical discourse of K-pop within globalization. In New Korean Wave: Transnational Cultural Power in the Age of Social Media; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016; pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J. China’s Weibo: Is faster different? New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).