Abstract

The Gubbio Revisited project, initiated to reinterpret the archaeological evidence collected during the 1980s Gubbio Project, primarily by a conversion from a paper to a digital record, has revealed significant insights into the evolving settlement patterns and religious expression in the Gubbio valley in Central Italy. This reanalysis of the survey evidence underscores the rhythms of settlement and ritual practice from the Neolithic through the Bronze and Iron Ages, into Roman times. Key excavations in the 1980s at Monte Ingino, Monte Ansciano, San Marco Romano, and San Marco Neolitico added details not only of settlement activity but also of embedded ritual, evidenced by material culture including pottery, faunal remains, and votive offerings. The foundation myth of indigenous religious practices, even amidst Roman influence, is documented through the Iguvine Tables alongside the introduction of new cults, showcasing a blend of local and imperial religiosity, a common feature in the Roman world. This research enriches the understanding of Gubbio’s historical and cultural landscape, emphasizing the demographic rhythms of the valley alongside the integral role of ritual in its societal evolution.

1. The Prehistory of the Valley

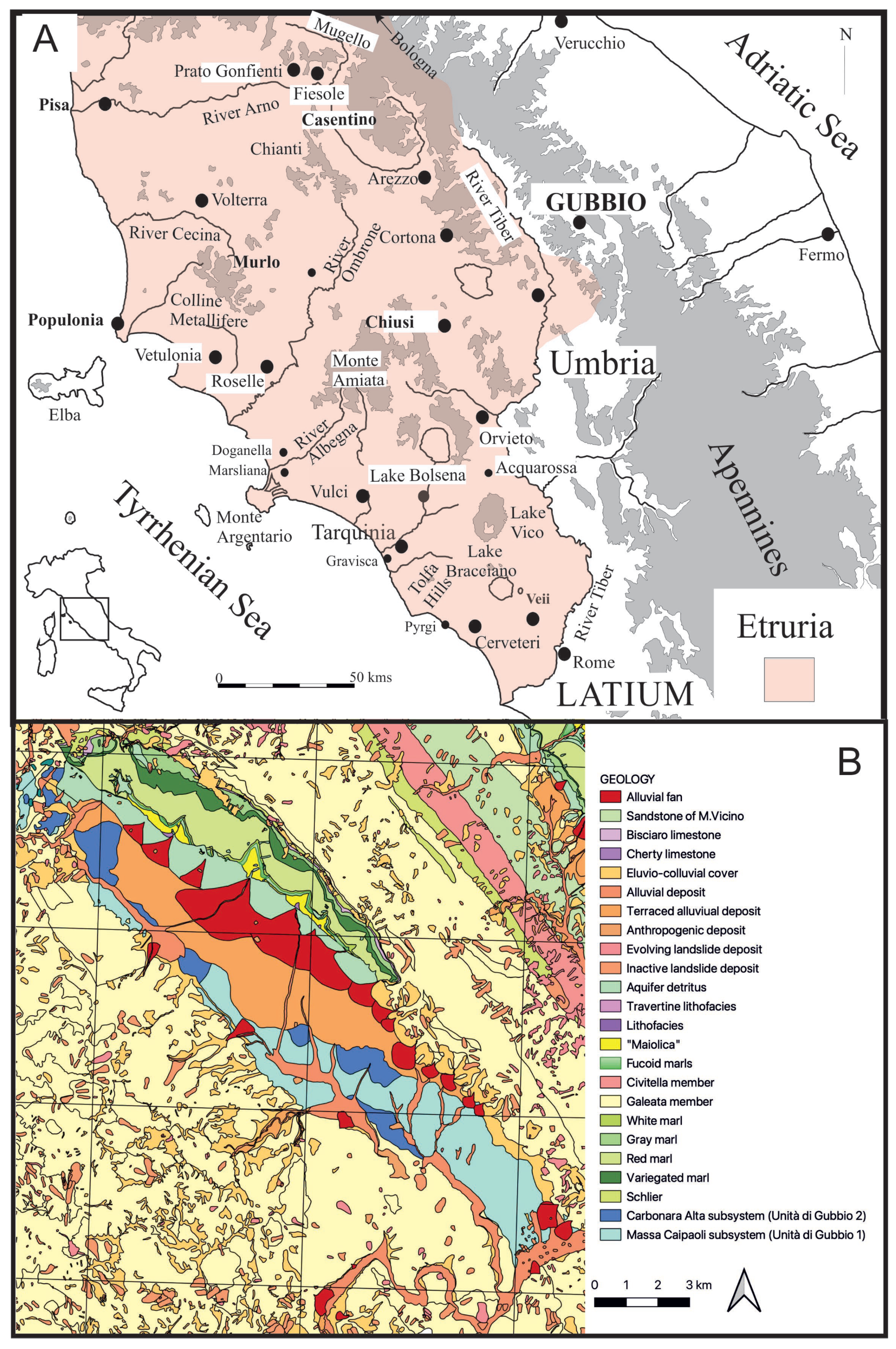

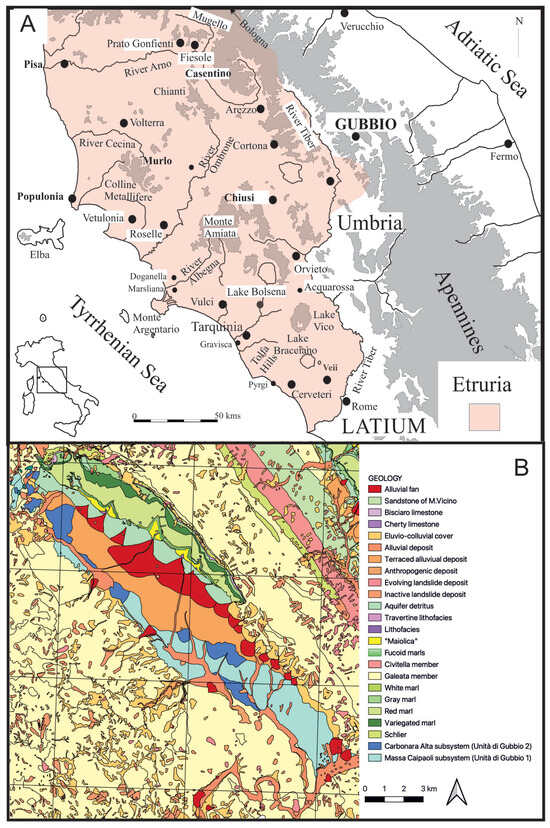

The valley of Gubbio is located (Figure 1) in the northeast part of the modern region of Umbria (Central Italy), bridging the Marche to the East and Tuscany to the West. The region is thus a zone of transition, nestling in an upland valley, created out of the intermontane tectonic orogeny of the Apennine foothills. Its geographical location has led to a sharing of political and cultural influence with both these flanking regions. In some ways, the cultural links are mapped onto the geography since the northeastern watershed of the valley drains both into the Adriatic and the Tyrrhenian seas. The intermontane valley itself runs from the northwest to the southeast, linking the uppermost reaches of the Tiber Valley to the Chiascio catchment which itself runs into the Tiber to the west and, the approximately north–south valley later occupied by the Via Flaminia to the east. The valley is occupied by extensive alluvial fans, running off the limestone escarpment to the northeast, and the higher central ground thus created has led to the curious drainage of the valley in two directions, both northwest and southeast, even if both flow ultimately into the Tyrrhenian sea. The southwestern flank of the valley is occupied by ancient relict terraces, and the lower more incised valleys, most marked to the southeast, are occupied by more recent Holocene deposits.

Figure 1.

(A) The location of Gubbio in the wider region of Central Italy; (B) The essential geology of the Gubbio basin.

Gubbio Revisited is a project, centered around the doctoral dissertation of Marianna Negro, which has the goal of reanalyzing and reinterpreting the archaeological evidence collected during the Gubbio Project, led by Simon Stoddart and Caroline Malone with the University of Cambridge in the 1980s and published in 1994 in Territory, Time and State. This publication focused primarily on the excavations of the upper slopes of Monte Ingino and Monte Ansciano, as well as the Roman farmhouse of San Marco Romano and the Neolithic site of San Marco Neolitico, located close to one another on the valley floor. The project also included an intensive survey of the valley whose results were broadly presented in 1994 but are now about to be published in greater detail. Reanalyzing the archaeological remains has both verified the long-term settlement trends and shed new light on the role and importance of the sacred in the Gubbio valley, beyond the pre-Roman sanctuaries of Monte Ingino and Monte Ansciano.

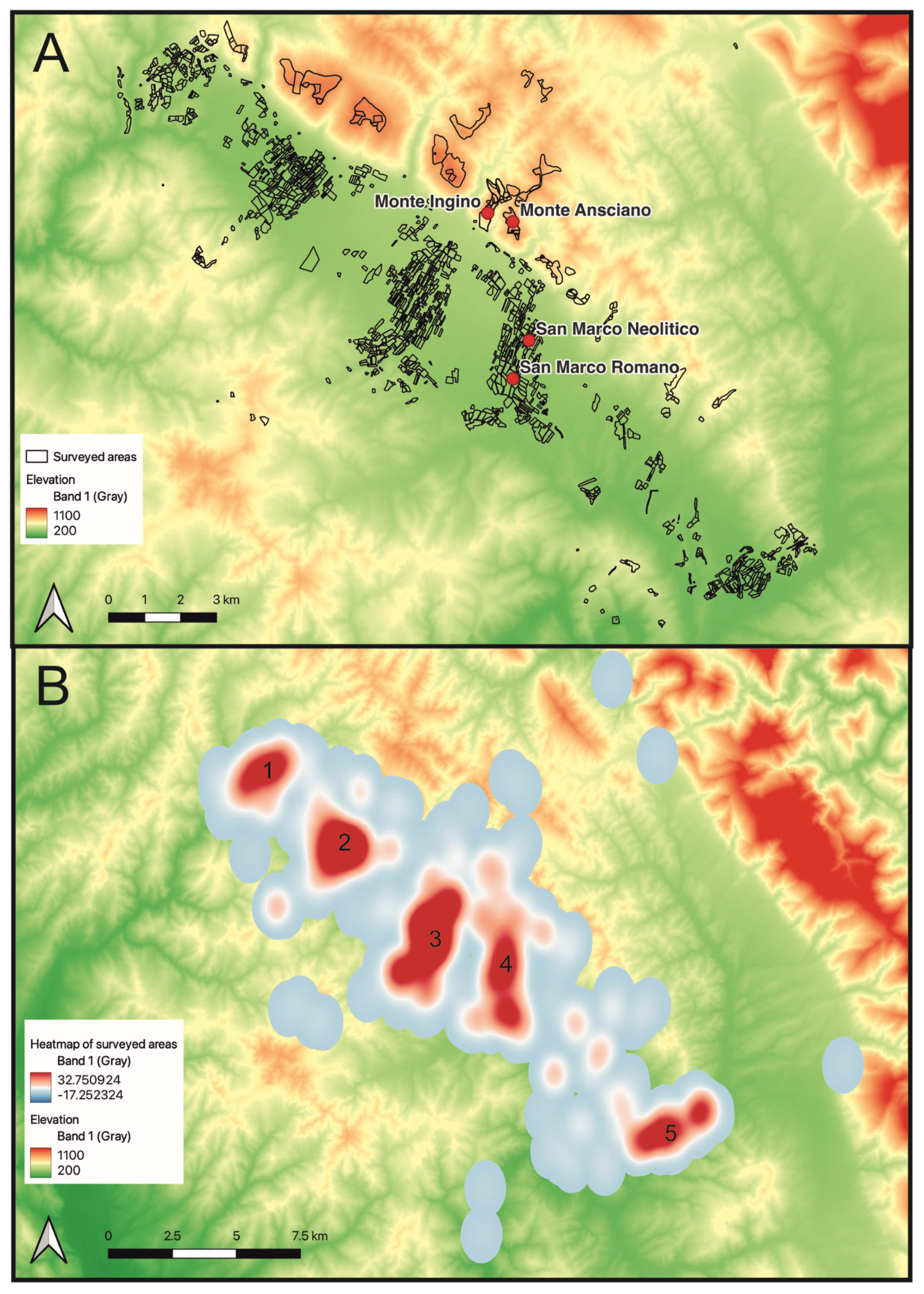

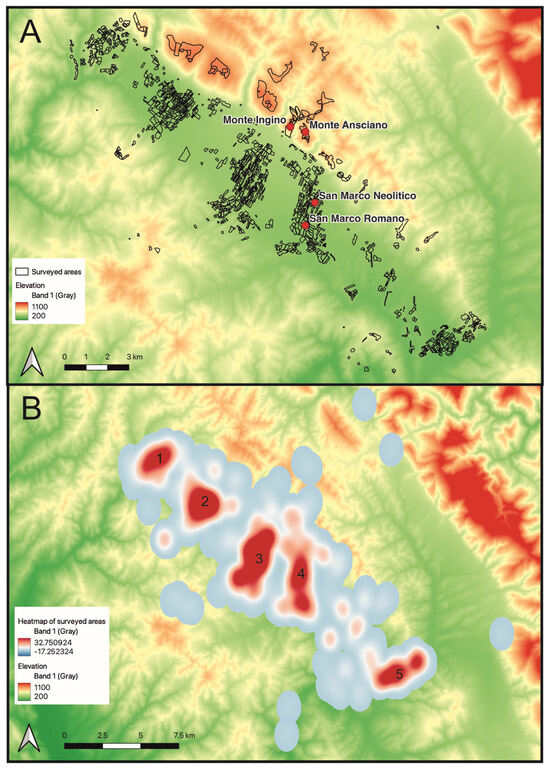

Any presentation of survey evidence needs to examine the underlying assumptions in the survival and collection of data. The original survey in the 1980s took the natural confines of the well-defined Gubbio valley as the region under study. The evidence from Figure 1B demonstrates that not all the valley was equally accessible from a geomorphological perspective, given the processes of erosion and alluviation over time, a fact that was much more severe for the Palaeolithic distributions compared with the Roman. The evidence from Figure 2 adds the fact that not all parts of the valley have been surveyed, most usually in response to difficult land use and limited human resources. Furthermore, fields were generally only surveyed once, and it is well known that conditions can change rapidly between seasons. A further matter to be considered is that a generous interpretation has been applied to the chronology of this surface material, a generosity that we think appropriate given the broad trends we are seeking to establish. Primacy has been given to the survey records made in the field, even though more accurate designations were made of individual artifacts in the 1994 publication. There is a considerable literature on issues related to surface survey recovery and interpretation (e.g., [1,2,3]) and since a broad-brush approach has been developed in this article, these complexities need to be considered when interpreting the overall trends presented. The term ”site” has been employed generically, and simply indicates the location where artifacts were discovered.

Figure 2.

The areas surveyed in the valley of Gubbio. (A) The fields surveyed; (B) A heat map representation of the fields surveyed to permit a better comparison with the density plots that follow. Essentially five transects (1–5) were placed across the valley.

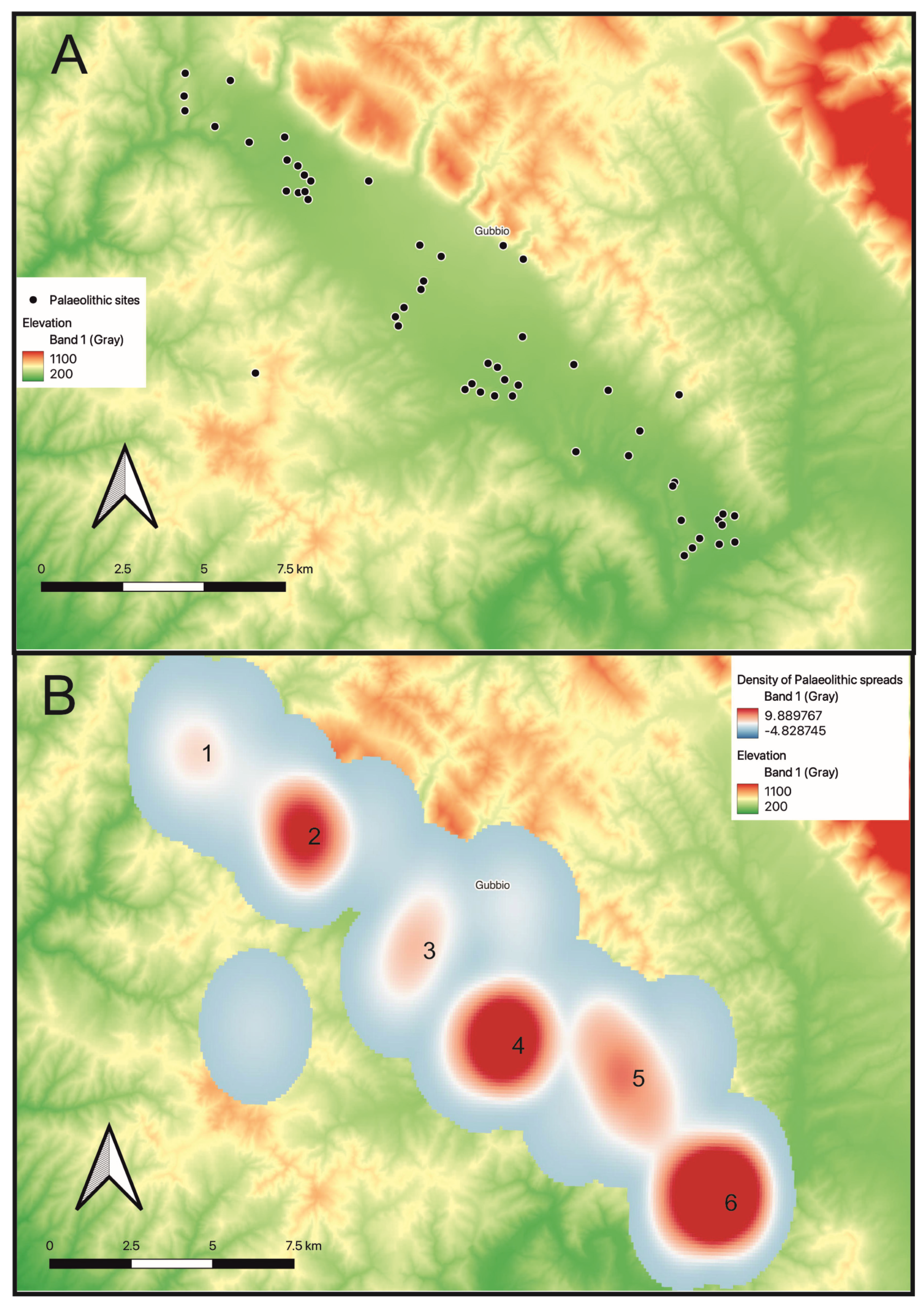

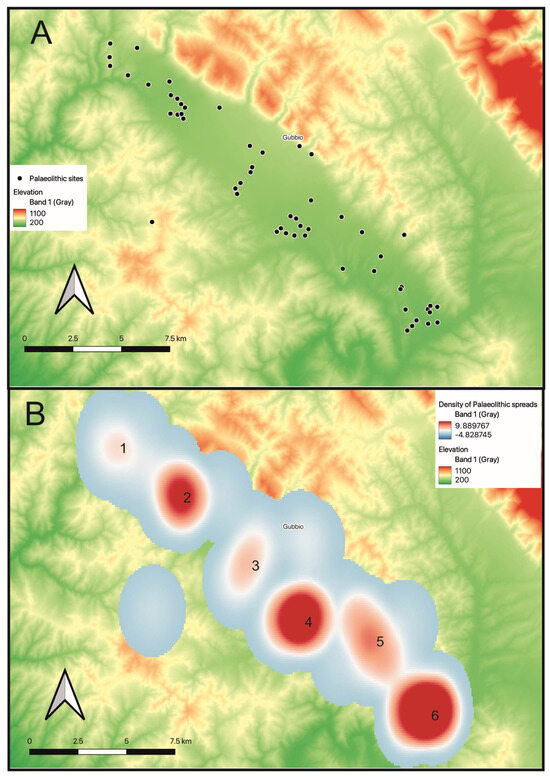

1.1. Middle Palaeolithic

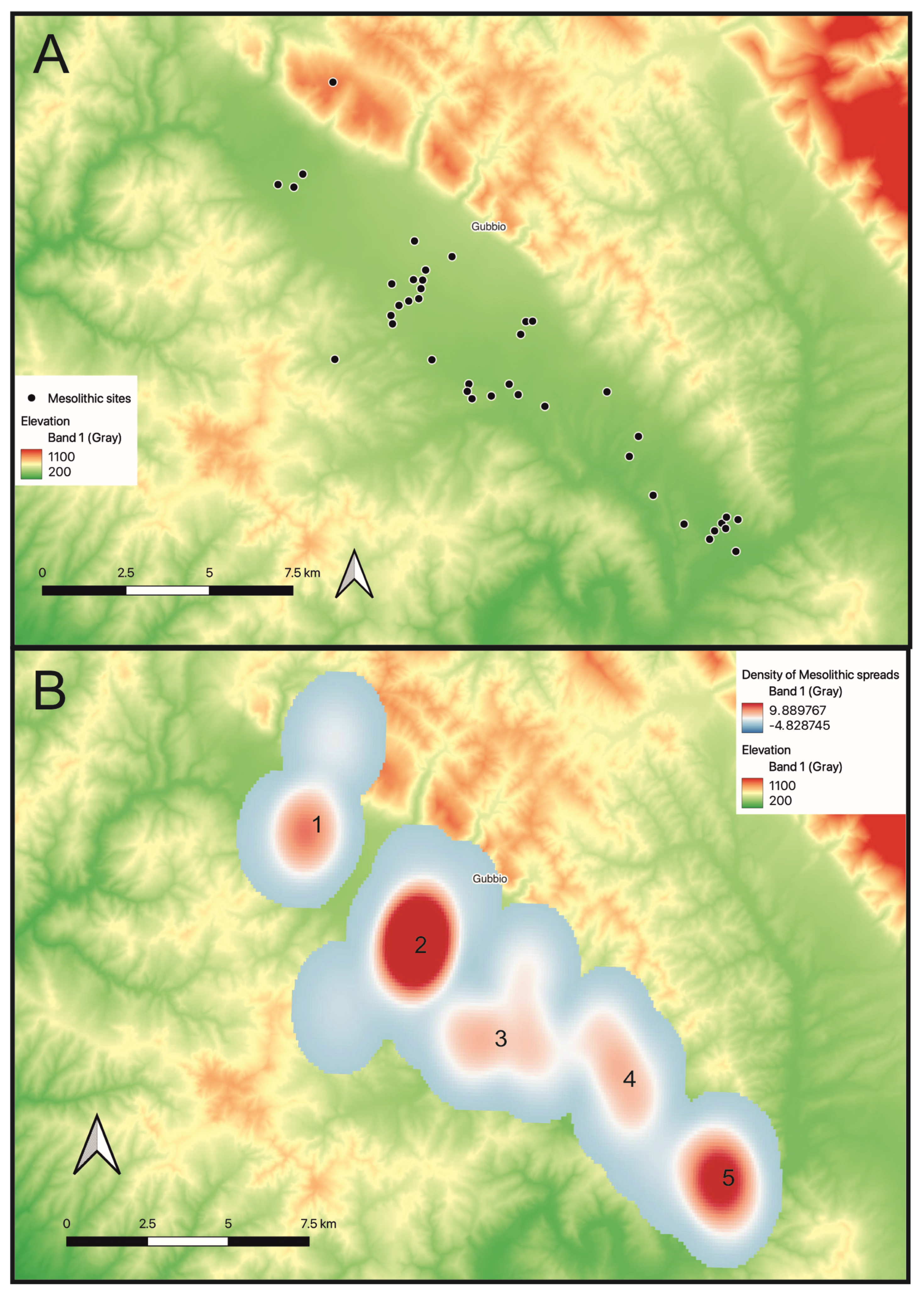

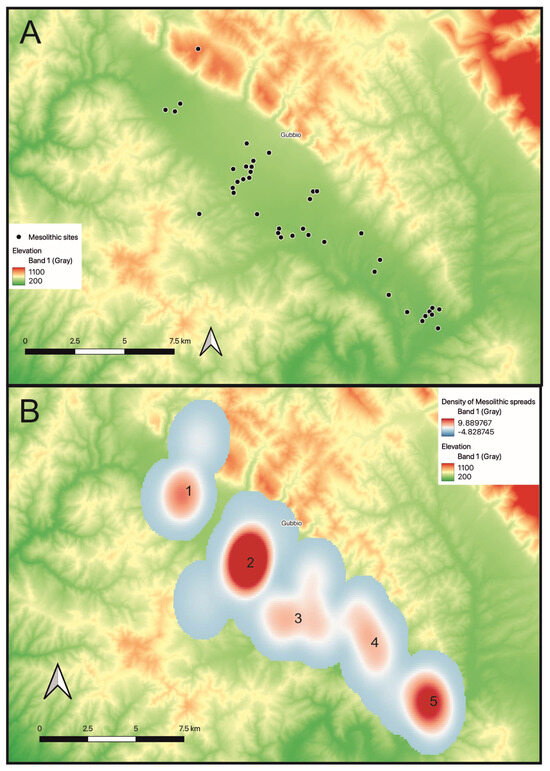

The first human exploitation of the valley can be dated back to the Middle Palaeolithic (210,000–35,000 years ago) although it is difficult to judge the intensity of occupation given the long timescale involved. Furthermore, the preservation of Middle Palaeolithic deposits was substantially determined by geological action, or more precisely the preservation of the previously mentioned, distinctively red, relict terraces located above Ponte d’Assi directly south across the valley from the modern city (Figure 1B). The pattern of Palaeolithic material in the Gubbio valley is very similar to the discoveries made in the upper Tiber valley [4], the only other area of Umbria where there has been systematic recovery of material over many years, in this case largely by the local archaeological group on the border between Umbria and Tuscany near Anghiari. In so far as it is possible to distinguish surface material, concentrations 4 and 6 in Figure 3 were largely Middle Palaeolithic in date, located on the terraces of similar geological date or earlier, whereas concentrations 1, 2 and 3 in Figure 3 were generally from the Upper Palaeolithic (35,000–10,000 years ago) period placed on an alluvial fan of a later geological date. At the end of the Palaeolithic (10,000–6000 years ago) (Figure 4), the distribution shows less evidence of geomorphological impact, with a wider distribution of more diffuse activity across the valley, even if with a strong element of continuity from the previous period in concentration 2 and to a lesser extent in concentration 5.

Figure 3.

(A) Distribution of Palaeolithic sites in the valley; (B) Heatmap of Palaeolithic activity based on the spreads of lithic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation, with the same range as Figure 4. Numbers 1–6 refer to clusters of sites cited in the text.

Figure 4.

(A) Distribution of Mesolithic (Epi-palaeolithic) sites in the valley; (B) Heatmap of Mesolithic (Epi-palaeolithic) activity based on the spreads of lithic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation with the same range as Figure 3. Numbers 1–5 refer to clusters of sites cited in the text.

1.2. Neolithic (and Chalcolithic)

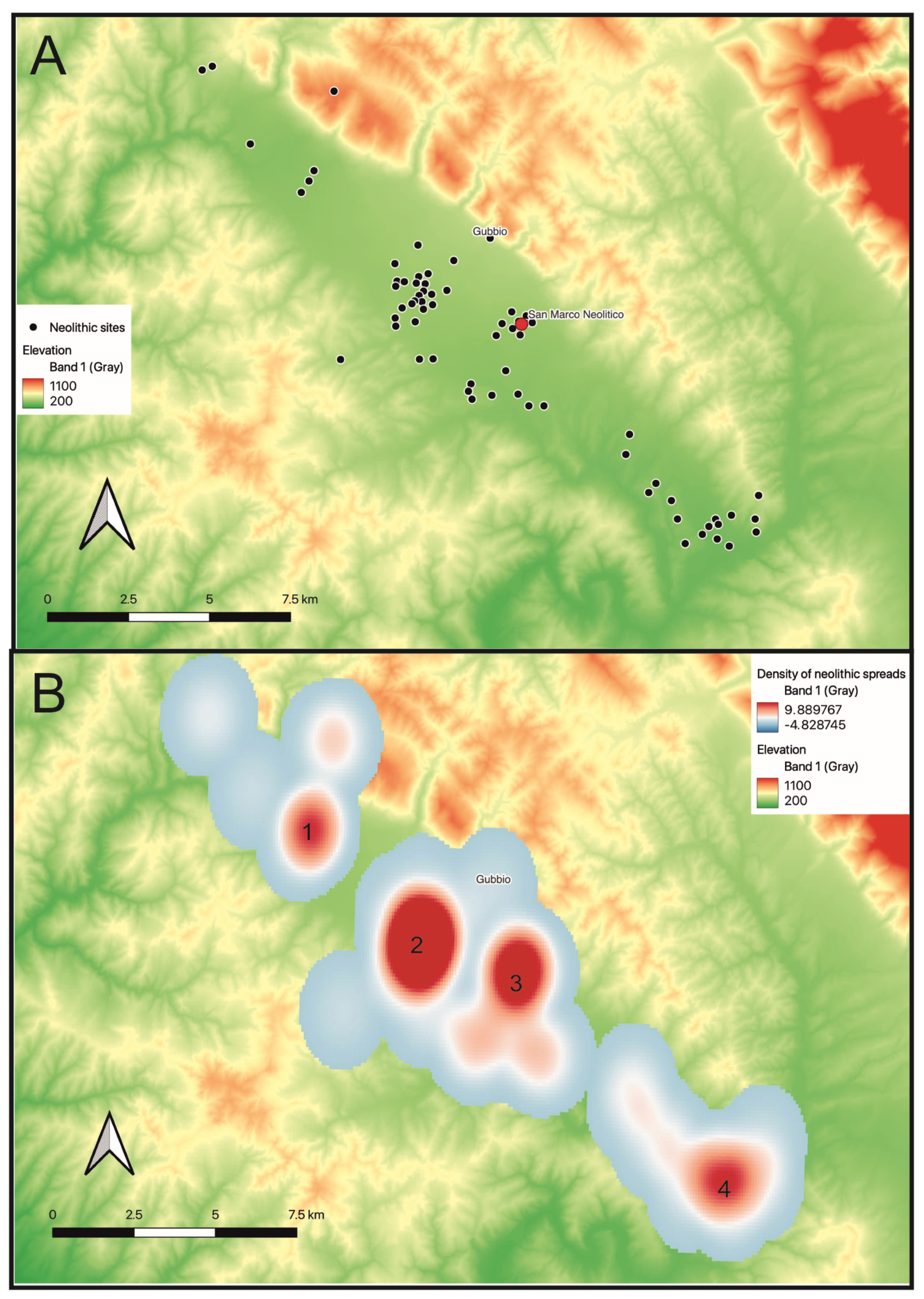

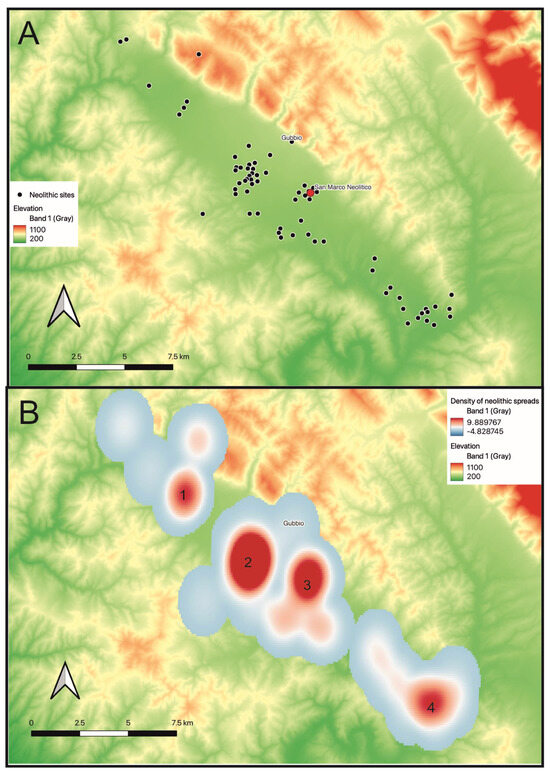

It is only with the Neolithic (6000–3000 BC) (Figure 5) that evidence for more substantial, less mobile settlement emerged, with a major focus on the mid contour of the alluvial fans in the center of the valley. This focus may be partly an ecological position in the landscape [5], suited to the collection of mixed resources, but may also be partly a geomorphological artifact, at a crucial change in slope of the alluvial fan where the balance of deposition and erosion led to a maximum revelation of the archaeological layers beneath. Taken at face value, there is concentrated evidence for Neolithic settlement to the west of Gubbio, under the slopes of Monte Semonte (concentration 1), on an alluvial fan descending down to Ponte d’Assi (concentration 2) and finally at San Marco to the East (concentration 3), where the site was excavated. San Marco Neolitico is a fundamental site for understanding the Gubbio, and indeed Umbrian, Neolithic, especially through the analysis of the faunal and floral remains, which permit the reconstruction of resource exploitation at the site, and its environmental context [5,6]. The excavated material also illustrates the character of lithic production and the use of pottery [6,7]. In particular, the lithic production is especially characterized by collections of specialized bladelet cores of local chert [6]. As far as the pottery is concerned there can be found affinities in style and decoration in the Italian regions of both Marche and Lazio, underlining the role of Neolithic Gubbio “a bridge between two worlds” [7]. The use of pottery is one of the most interesting points, since almost intact vessels, now displayed in the National Archaeological Museum of Perugia, were found in the ditch which formed a major feature of the site, suggesting a deliberate act of deposition. If this deliberate agency is correct, then this can be considered ritual action embedded within social practice, a phenomenon that is common in many prehistoric societies, seeking, in this case, to mark with culture a part of the landscape both by deposition and by construction (of a earth cut feature in this case) [8].

Figure 5.

(A) Distribution of Neolithic sites in the valley; (B) Heatmap of Neolithic activity based on the spreads of lithic and ceramic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation. A. Red dot is San Marco. ‘Numbers 1–4 in B refer to clusters of sites cited in the text.

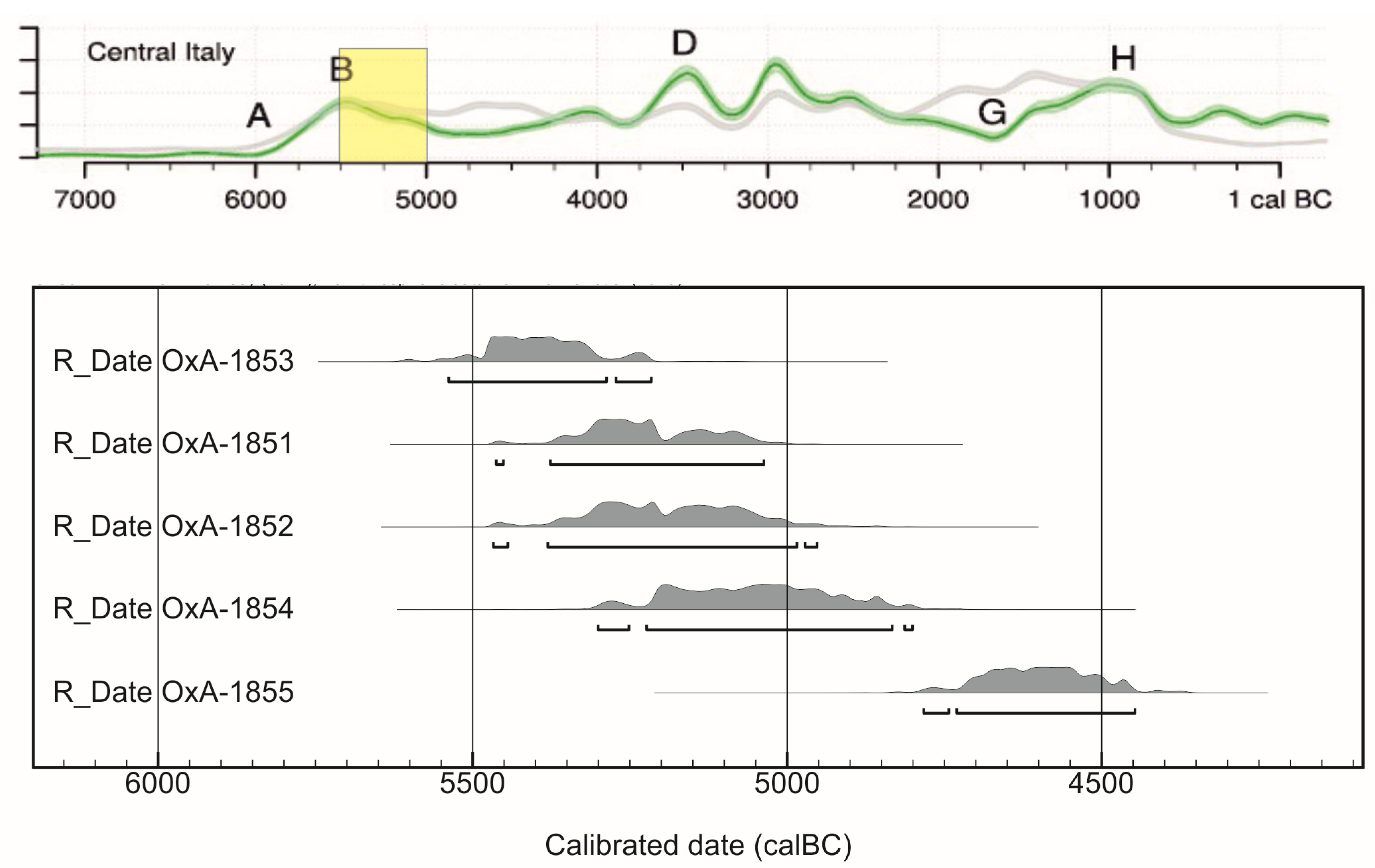

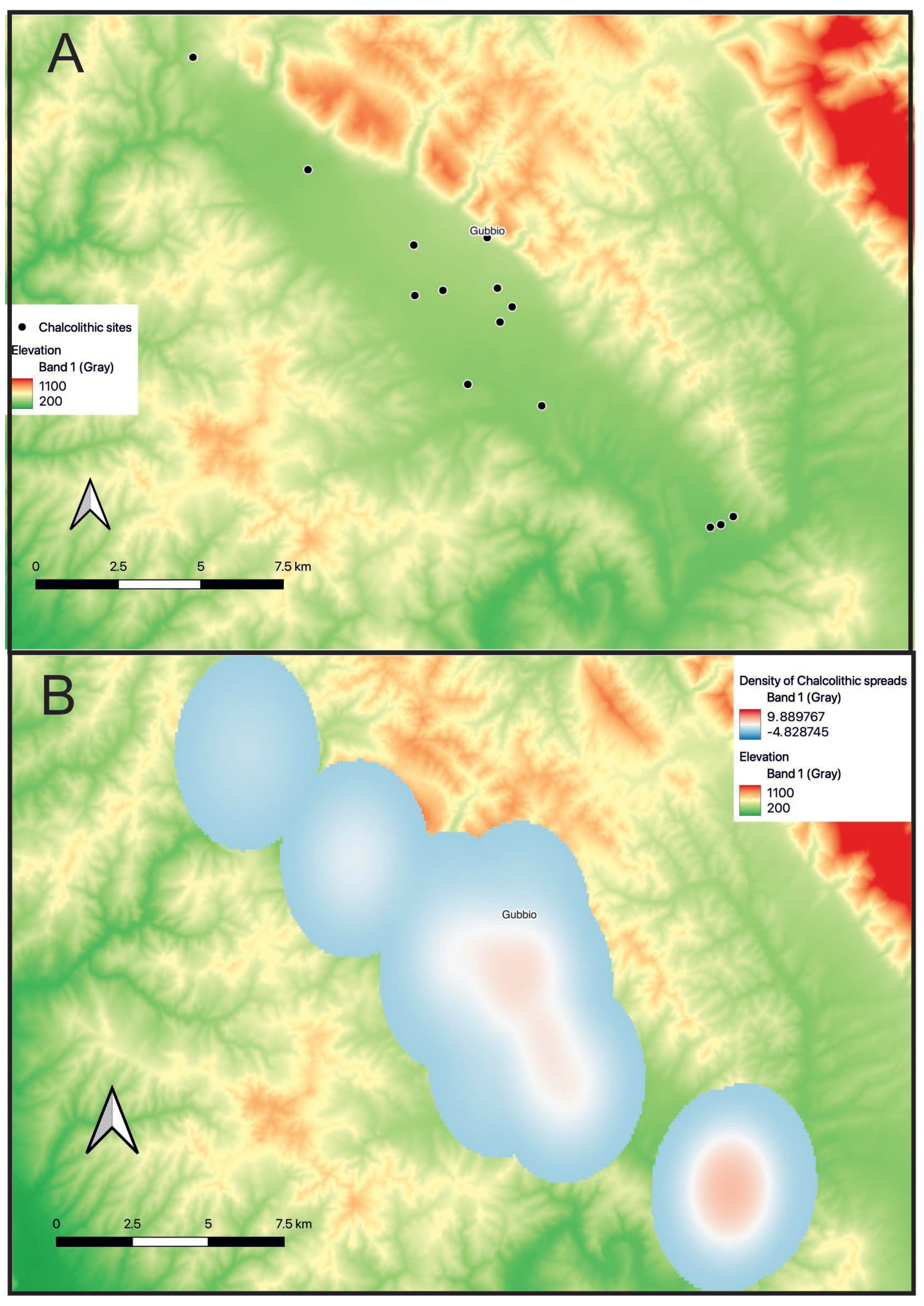

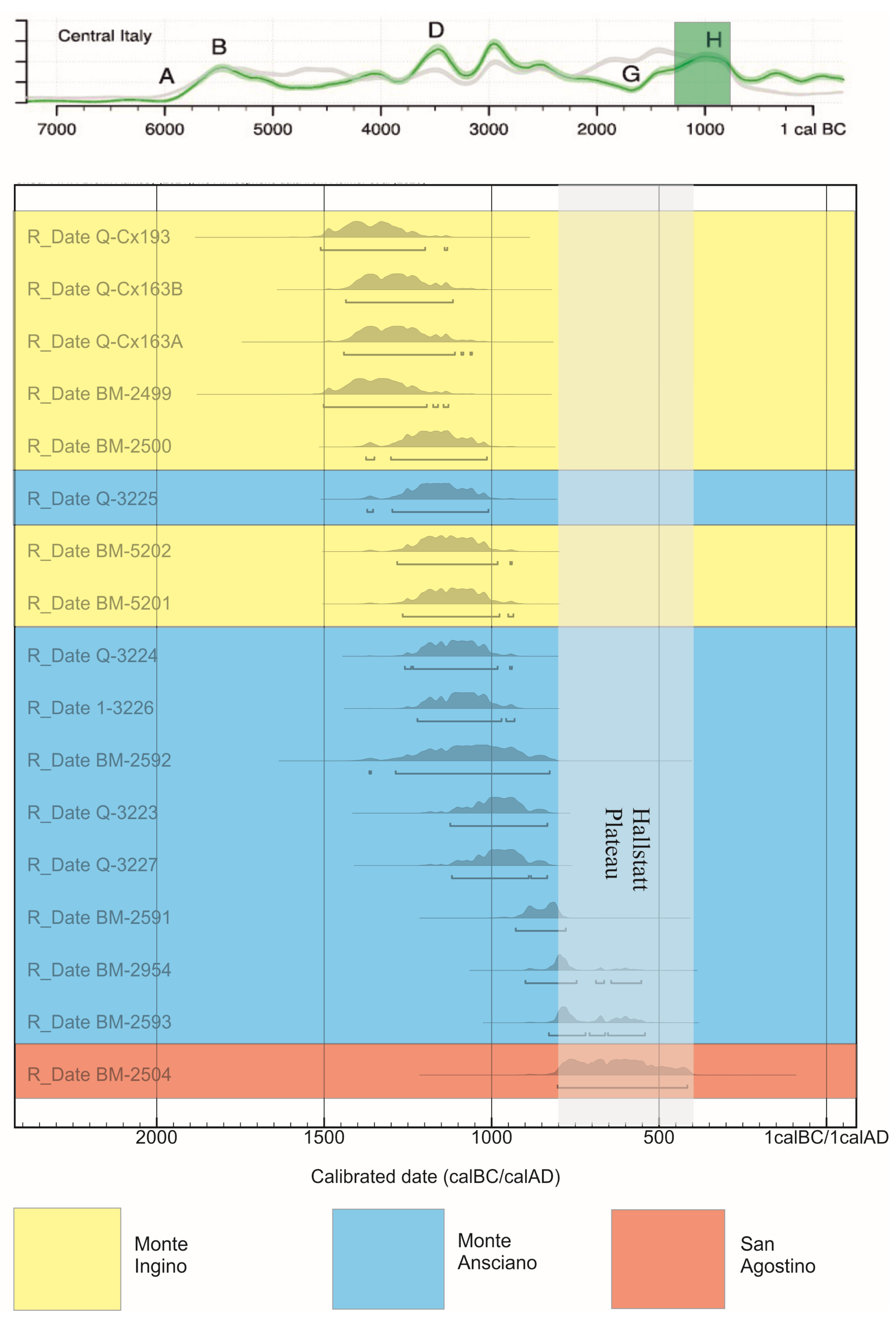

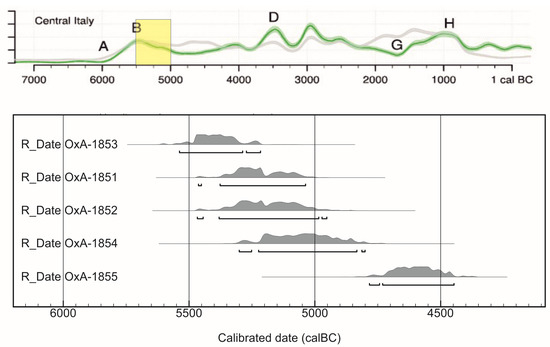

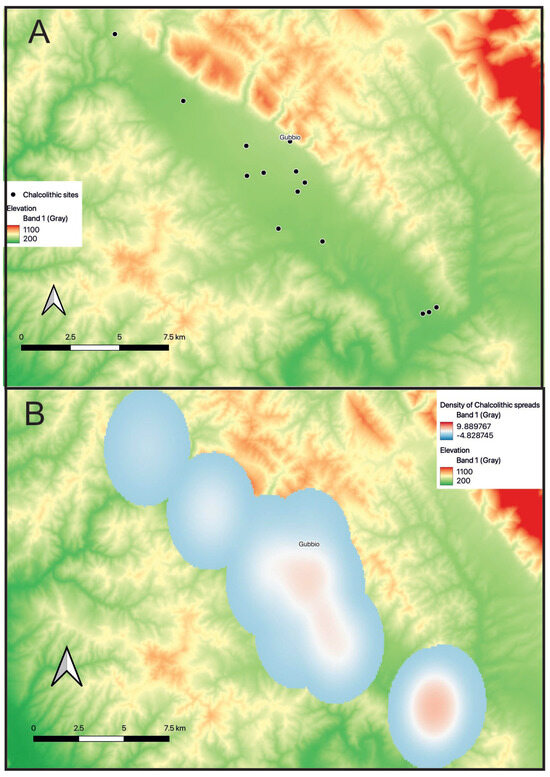

The analysis of the distribution of radiocarbon dates (Figure 6) shows that the Neolithic of the Gubbio valley coincided with the latter part of the peak of Neolithic activity in Central Italy. This is a pattern that makes considerable sense for the arrival of the Neolithic in this inland and relatively upland part of the region. Relatively little evidence has, however, been uncovered for the Chalcolithic (3500–2300 BC) (Figure 7), a pattern that also seems to be true of the other neighboring valleys, whereas it is a period that is much better represented in Tuscany and the Tyrrhenian coastal areas of Central Italy. Since the valley was systematically surveyed, this appears to be a radically different trajectory for the valley compared with regions further west.

Figure 6.

Distribution of San Marco Neolithic dates relative to the regional picture presented here [9] Calibration data based on [10,11]. A–H refer to significant changes in the “demographic” curve.

Figure 7.

(A) Distribution of Chalcolithic sites in the valley; (B) Heatmap of Chalcolithic activity based on the spreads of lithic and ceramic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation.

1.3. Bronze Age

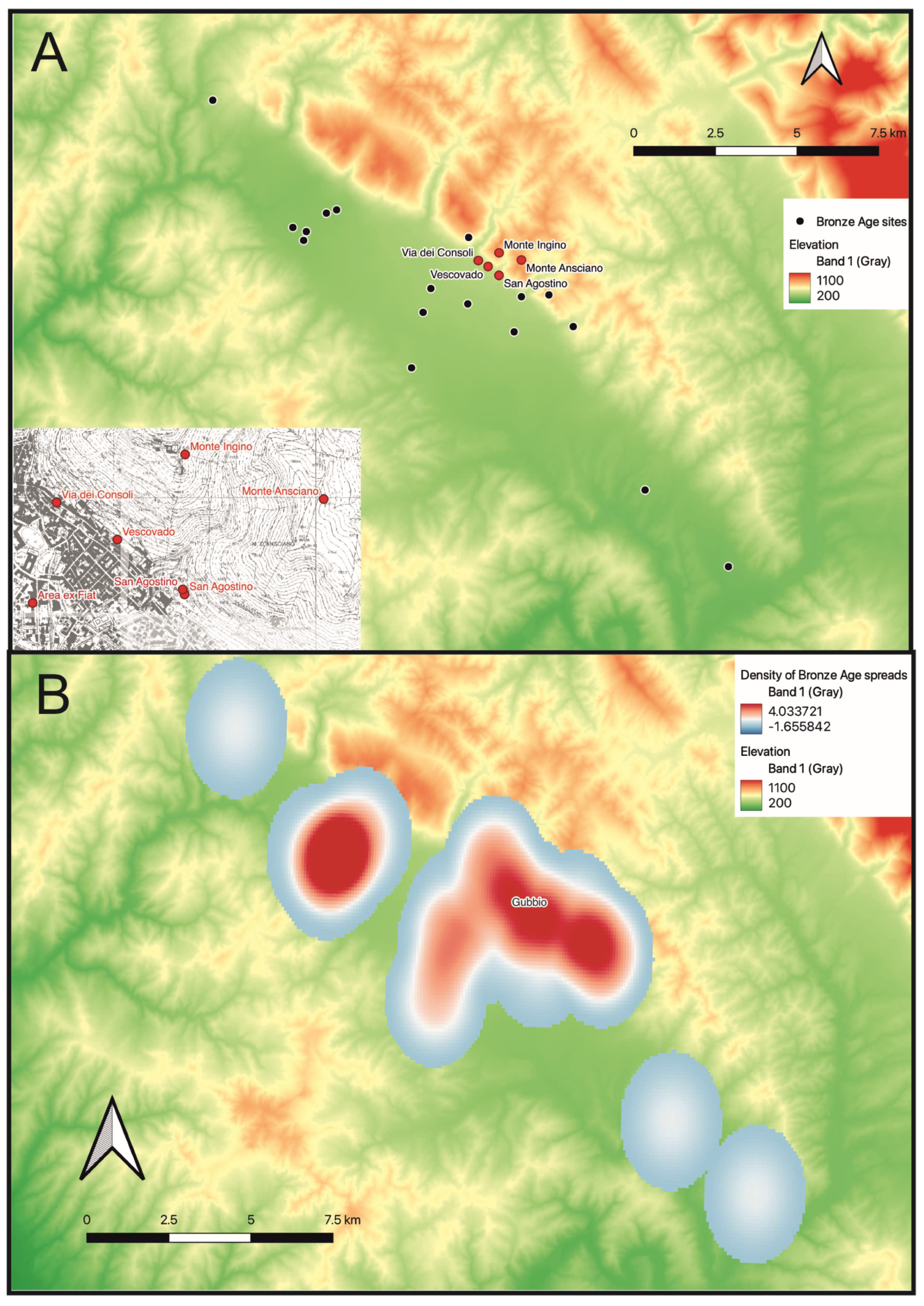

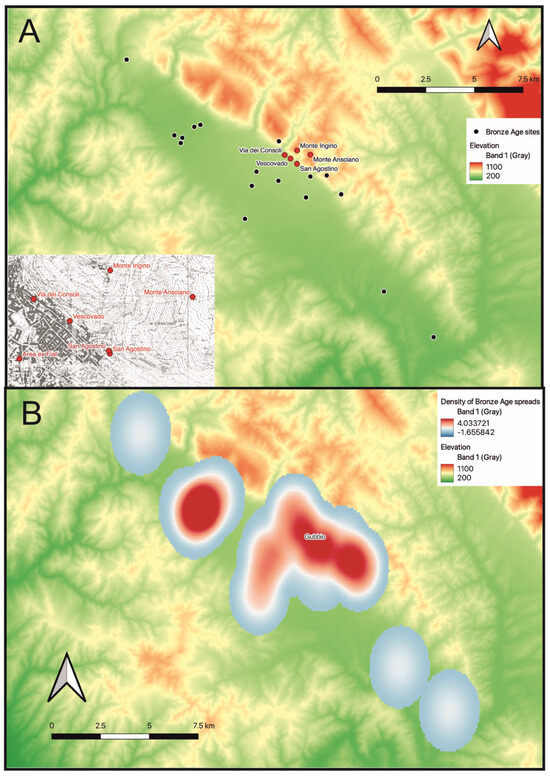

In the Middle to Final Bronze Age (1400–1200 BC) (Figure 8), the valley was once more integrated within the patterns of Central Italy, reflecting the inferred demographic increase throughout the region as interpreted from radiocarbon frequencies (Figure 9). The character of the distribution of settlement shares much with Monte Cetona to the west, where there was clear evidence of clustering of settlement. At Gubbio, the most important site of reference was Monte Ingino, or more specifically the Rocca Posteriore on the peak looking back towards the Marche in the direction of the Sentino valley. This site bridged the Middle, Recent and Final Bronze Age (Figure 9), and provided a focal, elevated point of reference for the community. We plan to submit further radiocarbon samples to establish a tighter chronology of this transition than those measured in the 1980s. Finds excavated from this prolific site included around 30,000 pottery sherds, small metalwork fragments (e.g., over thirty dress pins), very few lithics and 3000 carbonized seeds [12]. In addition, more than 25,000 fragments of animal bone were recovered (principally sheep, cow and pig), representing an estimated 75% of all the published animal bone of this period so far recovered from Central Italy. If we can interpret wealth as vested in flocks of animals conspicuously consumed in a prominent position intervisible with other contemporary sites, this would have been a substantial, communal, display: a prominent example of ritual embedded within social practice. These flocks may have been drawn from a wide territorial area, perhaps coincident with what is visible from the summit. This idea is being explored scientifically through isotopic and genetic studies of the animals to examine the range over which they were pastured, with results currently pending. Within the deposits, we can identify signs not only of consumption and burning of meat and grain, but also micro-rituals of deliberate fragmentation and bending of metal items. The structured deposition also included decorated, drinking and storage, ceramics as well as a smaller number of rarer artifacts including a decorated bone comb, an amber bead, animal figurines and glass beads. These last artifacts were seemingly distinct from the communal rituals, belonging much more to the personal sphere. This combination of finds once again underlines the embedded nature of rituals within social life during this period of the Bronze Age.

Figure 8.

(A) Distribution of Bronze Age sites in the valley and (inset) excavated sites around Gubbio; (B) Heatmap of Bronze Age activity based on the spreads of ceramic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation.

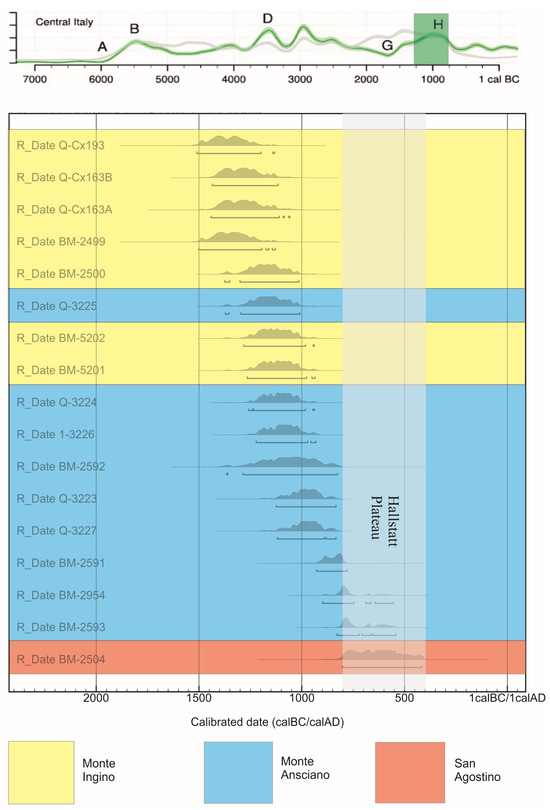

Figure 9.

The Bronze and Early Iron Age radiocarbon dates of Gubbio in the regional context of Central Italy presented here [9], showing the clear transition between the sites of Monte Ingino, Monte Ansciano and San Agostino, allowing for the complexities of the Hallstatt plateau in the calibration curve. Calibration data based on [10,11]. A–H refer to significant changes in the “demographic” curve.

These finds of the Middle, Recent and Final Bronze Age (1400–1200 BC) from Monte Ingino combine with other sites to form the impression of an important, expanding Bronze Age polyfocal settlement in the central part of the valley. In 2007, the rescue excavations in Via dei Consoli [13] brought to light evidence for another Middle Bronze Age settlement on the mid-slopes of Monte Ingino that continued into the Recent Bronze Age. During the Final Bronze Age, settlement, broadly in the same area, was accompanied by a cremation cemetery of at least 40 individuals. The settlement continued at Via Dei Consoli 103 and extended to Via Dei Consoli 105 and towards the southeast, where related material has been recovered in the excavation of the Vescovado. Final Bronze Age material has also been uncovered further down on the alluvial fan below Monte Ingino at the ex-Fiat site [14]. The mountain summit continued to present signs of embedded ritual activity during the early phases of the Final Bronze Age, but it is likely that the necropolis was built next to the principal settlement in a more sheltered location. This evidence on the summit and on the slope indicates an integrated complementary system of occupation of the mountain. The exposed location and harsh climate at 900 m, makes it plausible to suggest that the mountain top was used for rituals embedded in seasonal occupation of the upper reaches of the landscape. This seasonality of occupation is supported by the available evidence from the faunal remains of sheep and pigs mentioned above which on the basis of teeth wear [12] suggest a spring occupation.

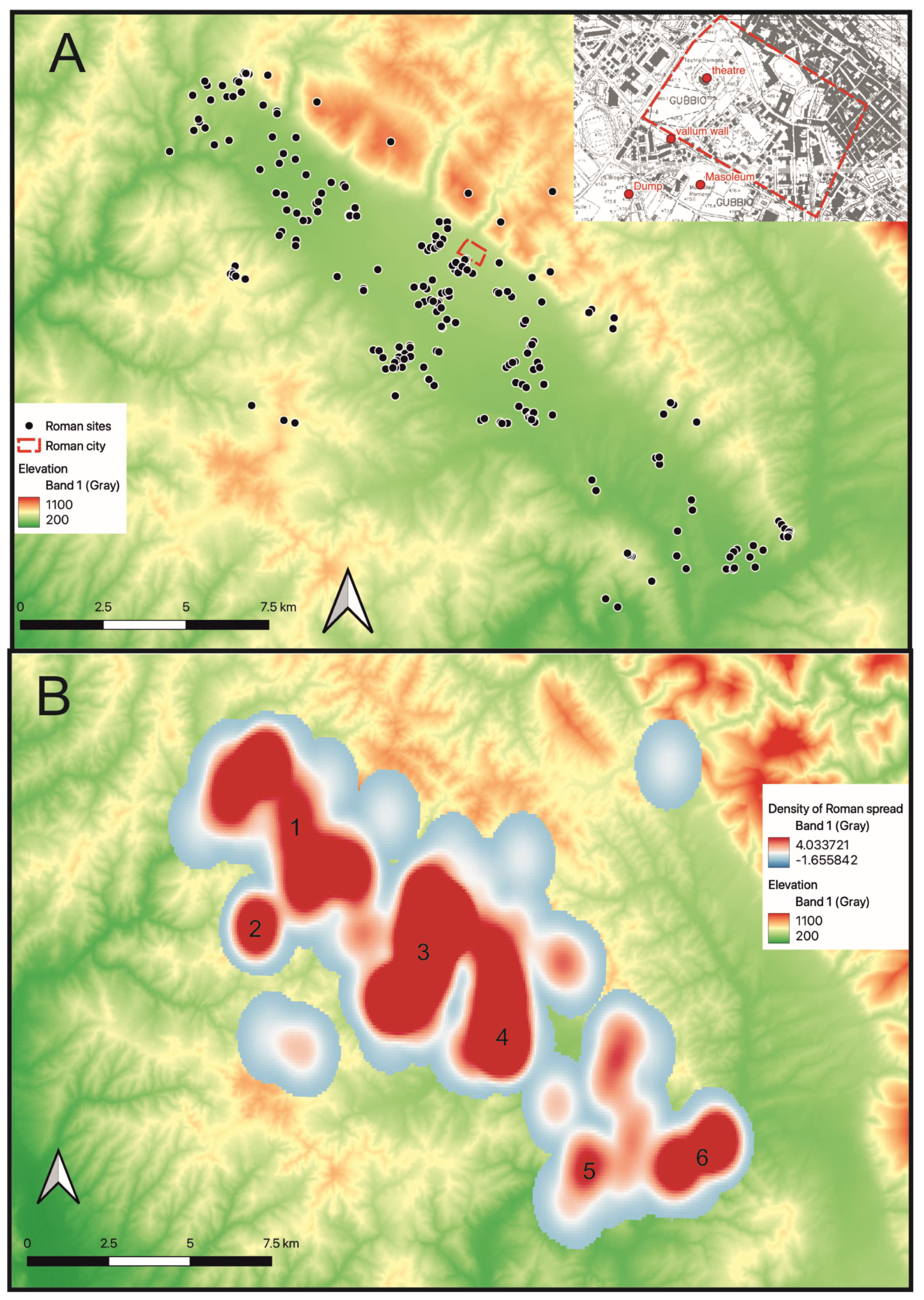

1.4. Iron Age

With the Final Bronze Age and beginning of the Iron Age (1200–1000 BC), it is also important to consider Monte Ansciano, also overlooking Gubbio to the East of Monte Ingino, on the summit of which a second site was excavated during the Gubbio Project. This excavation also recovered many faunal remains (c. 12,000 fragments) from the late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, including sheep, cow and pig, repeating the pattern of ritual consumption embedded in social life, although, based on the finds alone, without the same level of personal items. The only exception was the deliberate placement of an elaborate transitional Bronze Age/Early Iron Age fibula as one of the final acts of structured deposition above the midden deposit. The area in this period had a more developed built environment including an enclosure wall and an oval hut located in the saddle of the hill just below the summit.

The most distinctive feature of Monte Ansciano was the presence of structures and finds associated with its later use as a sanctuary in the Archaic period. These included a drystone platform placed above the Bronze Age enclosure, 65 schematic bronze figurines, of typically Umbrian style and datable to the 5th to 3rd Centuries BC, and an aes rude probably of the 3rd century BC. A representative sample of all these objects is now displayed in the Comune Museum of the Palazzo dei Consoli in Gubbio. The drystone platform separates the ritual embedded in social practice of the later Bronze Age and Early Iron Age from the more formalized collective rituals of the Archaic period practiced some vertical distance from the enlarged settlement which was by this stage located solely on the mid and lower slopes of the limestone escarpment of Monte Ansciano (including San Agostino) and at the ex-Fiat property [14] on the lower part of the alluvial fan.

The ritual characterization of the tops of the mountains is also emphasized by the fact that these peaks and others used in Umbria for deposition and other rituals, were all intervisible between each other [15]. For example, looking from Monte Tezio, to the north of Perugia, towards the northeast it is possible to see both Monte Ingino and Monte Ansciano as well as Monte Foce to the West of Monte Ingino. This visual interlinking may indicate an enduring territorial strategy of communities between the late second millennium BC and the early first millennium AD (the period hanging between prehistory and history which will be discussed below) actively displaying their presence to other groups, through the use of fire and feasting which result in the deposits on the peaks. This indicates that even though the rituals were transformed from those embedded in social practice of the late second millennium to more formalized rituals by the 5th century BC, clearly distinct from their settlement areas, marked by standardized figurines and more elaborate structures, they shared a sense of a regional community through shared ritual practices and intervisible ritual locations. Once again, the examination of the isotopic signatures (initially C/N and subsequently Sr) on the animal bones may give a sense of the breadth of the territory where the animals grazed, providing an indication of the territory managed by the human community.

After Roman integration, more intriguing material of a probably ritual nature was recovered from Monte Ansciano in the form of fragments of imperial period Roman lamps and simple drinking cups. Despite an apparent hiatus of 300+ years, these are of great interest, presenting the possibility of continuity of ritual focus without the construction of any additional associated structure. Thus, while the deposited lamps were Roman, their deposition in that location drew on Umbrian and Iguvine ritual practice, which was transferred down the centuries embedded in the collective ritual memory of the people and their relationship with the landscape and especially the mountain tops, which dominated the settlement.

2. The Distribution of Settlements between Protohistory and History

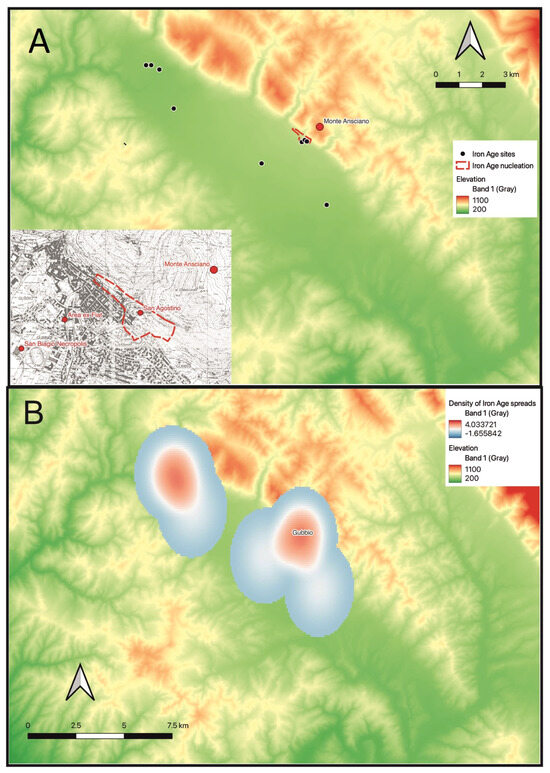

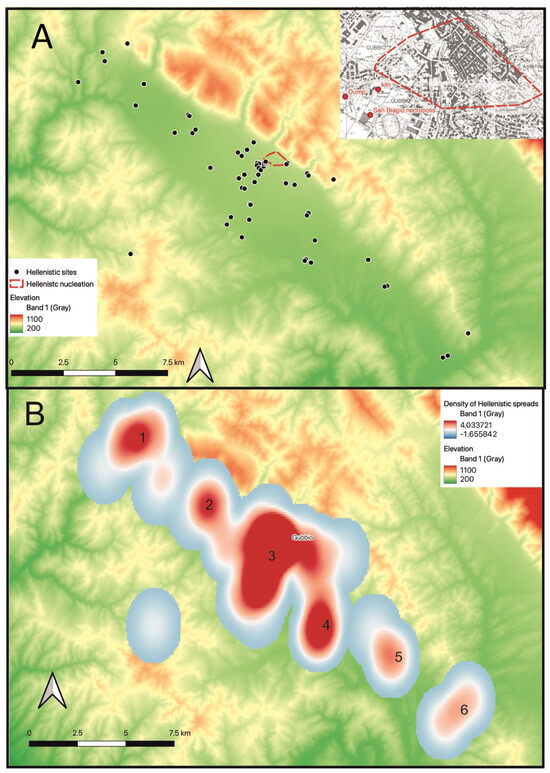

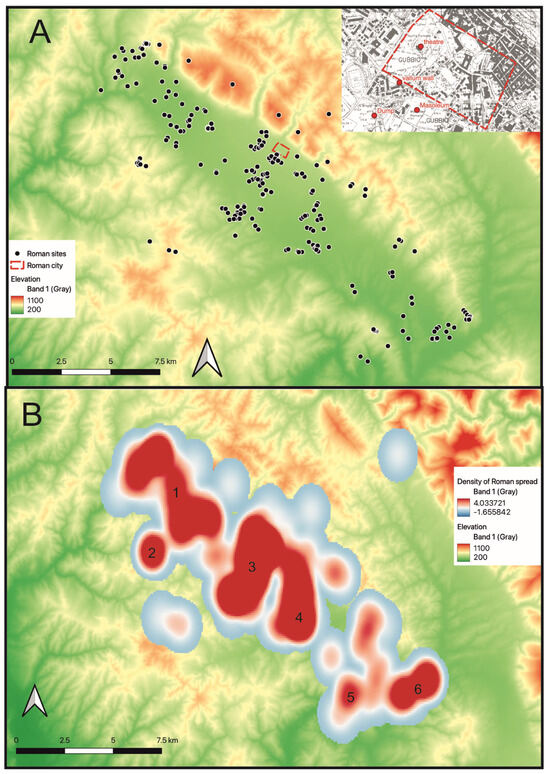

The entire Gubbio Survey data have been digitized and the later pottery has been restudied to enhance the analysis and interpretation of data in the valley from pre-Roman (Umbrian) to Roman times. To understand the phasing and distribution of the sites, a system of six phases was created (Table 1). A phase was defined according to the material culture, and in particular the fineware, present. For example, “imitation bucchero” and “late bucchero” were defined as Hellenistic and therefore mainly characterize Umbrian sites of Phase 2. In the interests of the longue duree focus of this article, these phases have been simplified into three density distributions to illustrate the broad trends within the valley. Employing this system and the quality and quantity of pottery recovered in each field, maps of the principal Iron Age, Umbrian and Roman sites in the valley can be created (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). This is where advances have been made in comparison with the 1994 publication which concentrated on the details of the prehistoric period. Further differentiation will be made in future publications, but here it is the longue duree at a scale comparable to the prehistoric period that has been favoured, without relating the details of new ceramic chronologies.

Table 1.

Phasing of pottery and correspondence to density maps in the later periods.

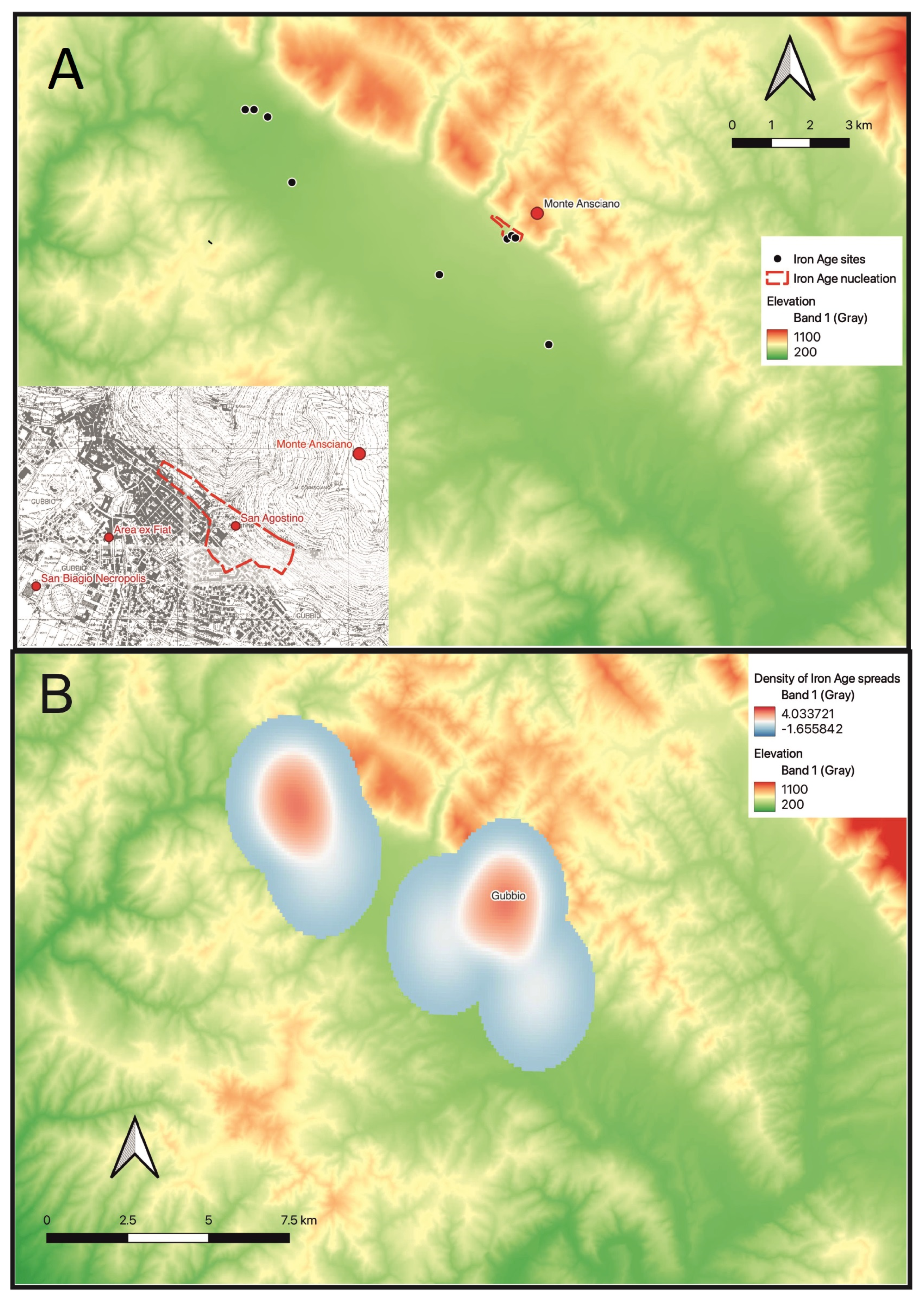

Figure 11.

(A) Distribution of Hellenistic sites in the valley with inset showing the Gubbio area; (B) Heatmap of Hellenistic activity based on the distribution of ceramic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation. The same scale of density of pottery is employed for Figure 10 and Figure 12. Numbers 1–6 refer to clusters of sites cited in the text.

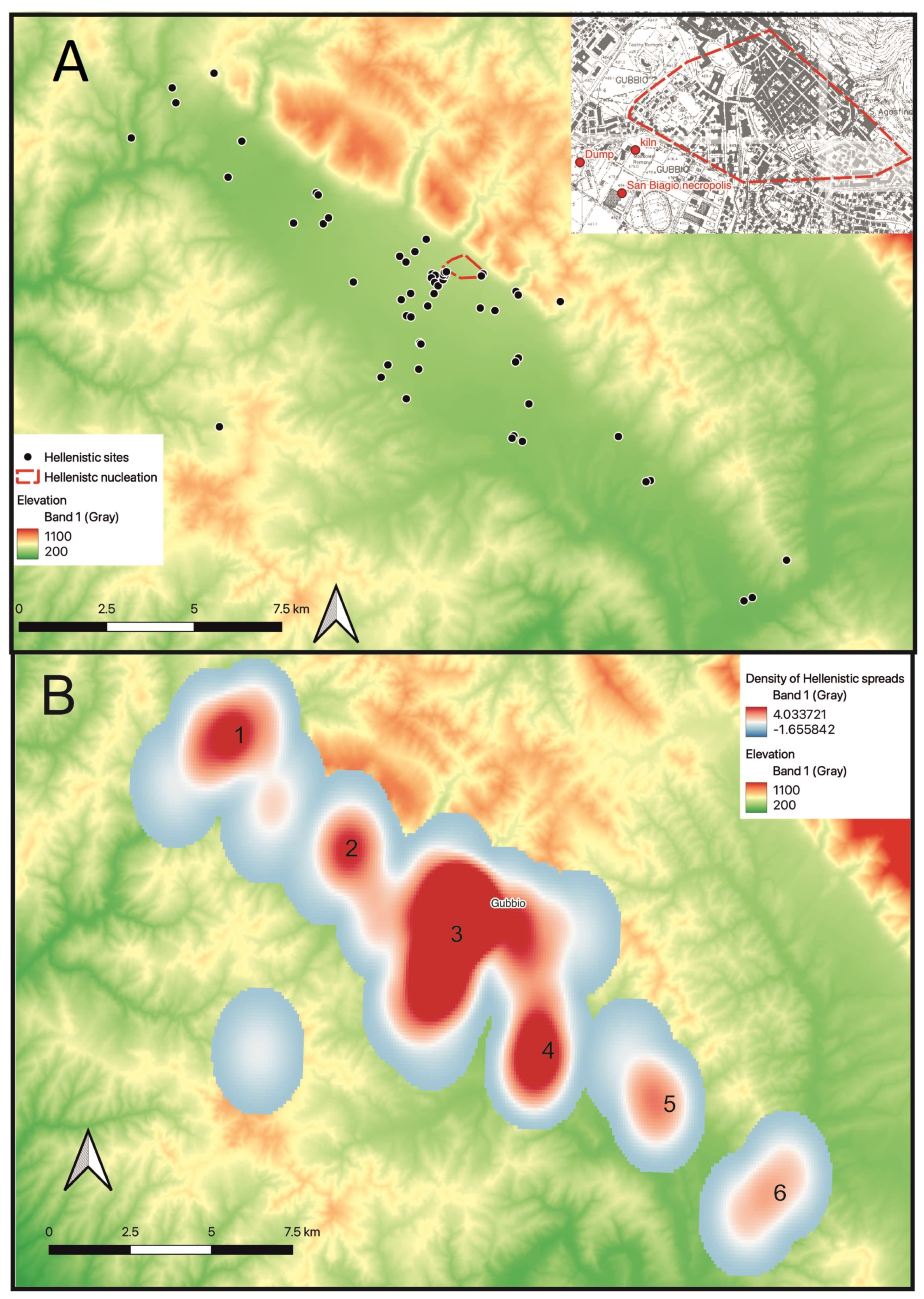

Figure 12.

(A) Distribution of Roman sites in the valley (with inset showing sites in the Gubbio area); (B) Heatmap of Roman activity based on the spreads of ceramic material recorded during the Gubbio Survey, using kernel densities estimation. The same scale of density of pottery is employed for Figure 10 and Figure 11. Numbers 1–6 refer to clusters of sites cited in the text.

Pottery density maps of the valley have thus been created for the three merged ceramic phases. These three maps (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12) are collectively useful in understanding the distribution of sites and density of activity in the valley and show an appreciable increase in rural activity from the Iron Age to the Hellenistic, reaching an almost complete saturation in the northern part of the valley during the full Roman period, although more detailed analysis, not represented here, shows a decline in evidence for the later Roman phases. Nevertheless, it is clear that, whereas the whole valley, including the most rural areas, was exploited, the density in some areas was much greater, such as around Mocaiana (Figure 11 and Figure 12, concentration 1), which corresponds to the fields in the northernmost part of the valley and Raggio just below. Interestingly the southeast of the valley, Branca (Figure 11 and Figure 12, concentration 6), although closer to the important communication route of the Via Flaminia seems to have had a lower density of pottery, plausibly in response to the much heavier Plio-Pleistocene clays of the area.

As would be expected, the densest material concentrations are around the town of Gubbio and likely represent several discrete areas of activity. The Gubbio Survey data suggest a high concentration of Umbrian activity around the urban area of Gubbio and the suburban area of San Biagio, where there was a vernice nera kiln datable between the end of the third century and the beginning of the second century BC, and a dump, which produced a meaningful number of many local vases [16]. The quantity of material in this area suggests the existence of a settlement, coinciding with Manconi’s identification of the location of Umbrian Gubbio in this area [17]. The material of Hellenistic date recovered on the surface appears to be too significant simply to result from the presence of the dump. According to Manconi, the dump was directly connected with the existence of the kiln, since the great majority of the material can in fact be identified as locally produced [18], although Sisani disagrees, considering the dump to be a consequence of urbanization during Roman times [18]. Despite the debate about the origin of the dump, the presence of the kiln and abundant ceramic material is evidence of the importance of the area before the Roman conquest.

The main Umbrian rural sites, based on the pottery that was recovered during the survey, are at Mocaiana and Casa Regni (Figure 11, concentration 1). The proximity of these two sites, indicates that rural settlement was well distributed and definitely developed in the territorium before the arrival of the Romans. The distribution of sites could, moreover, be an indication of a landscape pattern that is defined as typically Umbrian, drawn from analysis of the Iguvine tables by philologists Alex Mullen and James Clackson [19]. This proposes that there was more focus on the community and less on boundaries, where according to the Iguvine tables the only relevant boundary was the upper sky limits of the sanctuaries on the upper reaches of the landscape. From the data presented in this research, and especially the occupation of the rural areas, it is clear that the use of the landscape was not so tightly restricted to the main community of Gubbio itself, but extended into other smaller nucleations in the wider landscape.

Mocaiana in the north provides an interesting case study, because there are many Roman sites, but also one main Umbrian site. The Umbrian sites show continuity of occupation into the Roman period and must have had an influence on the wider Roman period settlement of the area. Also, since Mocaiana is at the foot of Monte Loreto, another Iron Age hilltop sanctuary, memory may have had a role in shaping the landscape. In addition to Mocaiana under Monte Loreto, there were other sites in the Gubbio area, which appear to be close to or associated with ritual spaces, in particular San Agostino under Monte Ansciano and San Biagio, close to a series of necropoleis.

On this basis, we can also briefly set the valley of Gubbio within the regional context of Central Italy. The new information presented here modestly revises our previous view of the Umbrian pre-Roman countryside [20,21,22], that there was relatively little pre-Roman rural settlement in the Gubbio valley. However, it remains true that the concentration of fully archaic and preceding orientalizing material was progressively greater in the direction of the territories of Perugia, Chiusi and, even more emphatically, the great cities of the Tyrrhenian coast [23,24]. Even in the Roman period, when the rural occupation of the Gubbio valley reached a substantially new level of density, it was not as great as that reported in the more central provinces of Central Italy [25].

3. Roman? Religious Landscape

The Iguvine tables were discovered in 1444 and, although complex and difficult to interpret, are fundamental to understanding the particular embedded religiosity and complex rituals of the valley. The seven tables are written partly in the Umbrian and partly in the Latin alphabets, probably reflecting the date of transcription onto bronze and underlining how the rituals described are pre-Roman, deriving from a religion which is intrinsic to Gubbio and Umbria and that was modified with the arrival of the Roman culture. During the Roman period in Gubbio, religion can be understood on three levels; there is the official political level, the local social and more Umbrian level, and finally the personal and private level. This makes an interesting parallel with the different scales (personal, social and inter-regional) already identified for earlier periods.

The first official level is the easiest to consider because its symbols and meanings were spread in the same way across Italy and the provinces. We know of typical Roman temples and sanctuaries in Gubbio through archaeological remains and inscriptions. For example, the foundations of the Temple of the Guastaglia, in a Roman quarter of Gubbio, have been excavated and an artistic reconstruction made showing a traditional Roman temple form [26]. An inscription in the Palazzo dei Consoli names the quattuovir Gnaeus Satrius Rufus as the person who paid for the restoration of the Temple of Diana in the 1st century AD (CIL XI 5820) [27] (p. 98). The donation of Gnaeus Satrius Rufus is firmly part of the official level of religion having as much a political as a religious purpose; the inscription, which had been installed as a pair on the theatre complex and was, therefore, highly visible also records his restoration of the theatre and his other generous donations. This is a typical example of the process of romanization which involved mostly elites and politicians who, through visible local patronage could enter the Roman political class.

Another apparently similar inscription records that Iavolenus Apulus paid for the restoration of the Temple of Mars Cyprius, a rural temple, and also dedicated a statue of Mars, currently in Florence with a copy displayed in the Palazzo dei Consoli. Here the position seems very different, however, as it does not appear to have been highly visible or politically motivated. The inscription, in a rural temple on a statue base would have been rarely seen, but it has a religious element. The text, includes the formula votum solvit, indicating a direct relationship with the deity and, despite still being part of the level of official of religion, there is also a personal element on display. It is also interesting that the deity, Marte Cyprio combines Roman Mars and probably Cupra, a local/picene deity.

In two other fascinating inscriptions, Vittorius Rufus is named in a funerary inscription as avispex extispicus sacerdos publicus et privatus (CIL XI 5824) [27] (p. 97), with Sestus Vetiarius Surus possessing a similar title. That we have a record of two people in Gubbio who interpret the flight of birds and entrails and manage public and private rituals appears significant. While not an especially common profession in the Roman world, it was important in the Umbrian/Etruscan environment and played a very important role in the Iguvine tables. These individuals appear, therefore to provide a direct connection to an Umbrian past with its landscape, birds and celestial boundaries.

The Iguvines, taking advantage of their position in the Roman Empire, imported some cults from Egypt, in particular the cult of Isis and her son Harpocrates, of whom a statuette is now displayed in Palazzo dei Consoli. Moreover, in the Roman cemetery of the Vittorina, where 237 tombs were excavated by the Soprintendenza, there are images of Harpocrates in two tombs, 80 and 232, the latter a child’s tomb in which was an apotropaic pendant of the God. In the same cemetery, tomb 117, a supine inhumation, is that of the ‘priestess of Isis’, who was found holding a sistrum, typical of the cult, in her left hand and with an incense burner in each of the four corners of the tomb, now displayed in the Antiquarium of Gubbio next to the Roman theatre. These incense burners take the shape of a stemmed carinated kylix with finger impressed decoration on the rim and were a common find during the Gubbio Survey, in the excavation of San Marco Romano and in other tombs of the Vittorina. While present in other areas of Italy, they are a much more common find in the Gubbio valley and may be seen as a marker for some rural Iguvine ritual practice. Similarly, 14 small fragments of terracotta figurines were found in the rural areas of the valley during the survey. While 14 is not a large number in absolute terms, because of their size and characteristics, the probability of finding them during survey was very low and therefore the original number in the landscape must have been correspondingly very high. We are not aware of similar figurines being found on survey elsewhere in Italy, indicating a specific local, rural ritual practice. These figurines are likely, therefore to represent a much larger number that was once deposited in the rural landscape of Gubbio and were probably markers for a personal level of ritual or religious festival.

4. Discussion

The Gubbio Revisited project is significantly enhancing our understanding of the Gubbio valley’s historical and cultural landscape. We have presented here the broad trends of occupation of the Gubbio valley, showing not only a general trend of increasing intensity culminating in the Roman period, but also phases of relative inactivity. We have also given a general sense of comparison with the wider trends of development in the broader region of Central Italy, showing where the valley is in and out of alignment, drawing on comparisons of settlement and radiocarbon density. At the same time, through a reanalysis of the archaeological evidence collected during the original Gubbio Project, and through other textual, epigraphic and archaeological evidence, this research demonstrates the levels of continuity and evolution of ritual practices from the Neolithic to the Roman periods. In the earlier stages, there was a pattern of ritual practice embedded in social life. In the later stages, the ritual practice embedded in social life was complemented by more formal rituals within the urban form. In this later period, the persistence and development of indigenous religious practices, in parallel to growing Roman influence, presents a unique blend of local and imperial religiosity. The full re-examination not only sheds light on the sacral significance of the Gubbio valley, but also emphasizes the integral role of ritual in its societal evolution, offering a richer, more nuanced perspective on the valley’s past.

The extensive data, particularly regarding ceramic evidence from later periods, provides a solid basis for understanding density patterns. However, since these data rely on lithic and ceramic distributions documented in paper records from the 1980s, it cannot be entirely accurate. Data from earlier periods are less precise because of the absence of re-analysis of pottery, which would have provided a more detailed understanding of site dating. Methodologically, the reanalysis has leveraged modern techniques such as advanced radiocarbon dating and GIS mapping, offering a more precise understanding of settlement patterns and chronological frameworks. These methodologies have addressed some limitations of the original data, though inherent potential inaccuracies in the earlier records remain a challenge. Consequently, the Gubbio Revisited Project generalizes earlier periods more than later ones. Nonetheless, survey data from earlier periods are complemented by systematic excavations, particularly for the Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age, which provide detailed insights into settlement patterns and both domestic and ritual activities.

Ritual activity is a fundamental feature of the valley, intrinsic to and embedded in the landscape, influencing settlement patterns. The valley’s particular geography, delimited by its upper reaches, means that principal settlements, including Gubbio itself, were founded on the slopes of these sacral places. Rural sites were distributed throughout the valley across all periods, although with varying densities and phases of inactivity, highlighting a specific pattern that persists through different ages in the valley. The importance of sacrality in the valley also suggests that religious and social activities were deeply intertwined, influencing not only daily life, but also the broader societal structures. This blend of local and Roman religious practices likely played a crucial role in the community’s adaptation to changing political and cultural landscapes. In conclusion, the Gubbio Revisited project provides a detailed and nuanced understanding of the valley’s past, emphasizing the integral role of ritual in societal evolution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N., N.W. and S.S.; methodology, M.N., N.W., S.S. and C.M.; software, M.N.; validation, S.S. and N.W.; formal analysis, M.N.; investigation, N.W., C.M. and S.S.; resources, S.S.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.; writing—review and editing, N.W. and S.S.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the British Academy, grant number SRG22\220926 and The APC was funded by the University of Cambridge, marginally discounted by a review undertaken by SS. Further funding was provided by Magdalene College and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research of the University of Cambridge. The town council of Gubbio welcomed the project with outreach opportunities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The Gubbio Revisited project would like to thank the British Academy, the McDonald Institute and Magdalene College, Cambridge for recent financial support. The project is centered around Marianna Negro’s PhD project, supported by Letizia Ceccarelli and Nicholas Whitehead for the identification of material culture and Simon Stoddart and Caroline Malone for background information. Caroline Malone, Nicholas Whitehead and Simon Stoddart all participated in the original 1980s project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bintliff, J.L.; Snodgrass, A.M. Off-site pottery distributions: A regional and inter-regional perspective. Curr. Anthropol. 1988, 29, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddart, S.; Whitehead, N. Cleaning the Iguvine stables: Site and off-site analysis from a Central Mediterranean perspective. In Interpreting Artefact Scatters: Contributions to Ploughzone Archaeology; Schofield, A.J., Ed.; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Terrenato, N. Visibility and Site Recovery in the Cecina Valley Survey, Italy. J. Field Archaeol. 1996, 23, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, A.; Abati, F.; Baldanza, A.; Coltorti, M.; De Angelis, M.C.; Mancini, S.; Moroni, B.; Pieruccini, P. L’ alto e Medio Bacino del Tevere durante il Paleolitico Medio. Ipotesi sul Popolamento e la Mobilità dei Gruppi di Cacciatori—Raccoglitori Neanderthaliani. In Bollettino di Archeologia on Line. Direzione Generale per le Antichità 2 (2011/2-3); 2011; pp. 171–201, Figure 17; Available online: https://bollettinodiarcheologiaonline.beniculturali.it/numero-2-3-2011-anno-ii/ (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Hunt, C.; Malone, C.; Sevink, J.; Stoddart, S. Environment, soils and early agriculture in Apennine central Italy. World Archaeol. 1990, 22, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, C.; Stoddart, S.; Barker, G.; Coltorti, M.; Costantini, L.; Giorgi, J.; Clark, G.; Harding, J.; Hunt, C.; Reynolds, T.; et al. The Neolithic site of San Marco, Gubbio (Perugia), Umbria: Survey and excavation, 1985–1987. Pap. Br. Sch. Rome 1992, 60, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, I.; Spagnolo, V.; Moroni, A.; Stoddart, S.; Malone, C. The Neolithic Settlement of San Marco di Gubbio (Perugia). A Reassessment in the Light of Recent research. In Atti dell’IIPP, Perugia, Gubbio; Studi Etruschi: Florence, Italy, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, R. An Archaeology of Natural Places; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, E.W.; McLaughlin, T.R.; Esposito, C.; Stoddart, S.; Malone, C. Radiocarbon Dated Trends and Central Mediterranean Prehistory. J. World Prehistory 2021, 34, 317–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk Ramsey, C. OxCal 4.4. 2021. Available online: http://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/oxcal (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Malone, C.; Stoddart, S. Territory, Time and State. In The Archaeological Development of the Gubbio Basin; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cenciaioli, L.; Germini, F. Gubbio. Il sepolcreto di via dei Consoli. In Gli Umbri in età Preromana. Atti del XXVII Convegno di Studi Etruschi e Italici; Bettini, M.C., Ed.; Istituto di Studi Etruschi ed Italici: Firenze, Italy, 2013; pp. 485–520. [Google Scholar]

- Germini, F. L’area ex-Fiat a Gubbio. In Bollettino di Archeologia on Line. Direzione Generale per le Antichità 2 (2011/2-3); Gangemi: Roma, Italy, 2011; pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, S.; Redhouse, D. The Umbrians: An archaeological perspective. In Entre Archéologie et Histoire: Dialogues sur Divers Peuples de L’italie Préromaine; Aberson, M., Biella, M.C., Wullschleger, M., Di Fazio, M., Eds.; Université de Genève-Faculté des Lettres-Département des Sciences de l’Antiquité: Genève, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, F. Gli scavi di via Bruno Buozzi. In Gubbio. Scavi e Nuove Ricerche. Vol. 1:Gli Ultimi Rivenimenti; Manconi, D., Ed.; Edimond: Città di Castello, Italy, 2008; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Manconi, D. Gli ultimi rinvenimenti. In Gubbio. Scavi e Nuove Ricerche. Vol. 1: Gli Ultimi Rivenimenti; Manconi, D., Ed.; Edimond: Città di Castello, Italy, 2008; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sisani, S. Tuta Ikuvina. Sviluppo e Ideologia Della Forma Urbana di Gubbio; Edizioni Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, S.; Baroni, M.; Ceccarelli, L.; Cifani, G.; Clackson, J.; Ferrara, F.; della Giovampaola, I.; Fulminante, F.; Licence, T.; Malone, C.; et al. Opening the Frontier: The Gubbio—Perugia frontier in the course of history. Pap. Br. Sch. Rome 2012, 80, 257–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddart, S. Changing views of the Gubbio landscape. In L’Étrurie et l’Ombrie avant Rome. Cité et Territoire. Actes du colloque International Louvain-la-Neuve Halles Universitaires, Sénat Académique 13–14 février 2004; Fontaine, P., Ed.; Belgisch Historisch Instituut te Rome: Rome, Italy, 2010; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, S. Between text, body and context: Expressing ‘Umbrian’ identity in the landscape. In Landscape, Ethnicity and Identity in the Archaic Mediterranean Area; Cifani, G., Stoddart, S., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Cifani, G. Approaching ethnicity and landscapes in pre-Roman Italy: The middle Tiber Valley. In Landscape, Ethnicity and Identity in the Archaic Mediterranean Area; Cifani, G., Stoddart, S., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 144–162. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, S. Power and Place in Etruria: The Spatial Dynamics of a Mediterranean Civilization: 1200–500 B.C.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zeviani, C. Invisible Etruscans. A study on Rural Landscape and Settlement Organisation during the Urbanisation of Etruria (7th–5th Centuries BC). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Launaro, A. Peasants and Slaves: The Rural Population of Roman Italy (200 BC to AD 100); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grassigli, G.L.; Cecconi, N.; Nati, D. Gubbio Guastuglia; Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Matteini Chiari, M. Museo Comunale di Gubbio: Materiali Archeologici; Electa Editori Umbri Associati: Perugia, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).