Trifid Mandibular Condyle: Case Report and Current Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- To report a new case of a 26-year-old female patient with a left TMC.

- (2)

- To review the existing literature on TMC, the relevant cases, etiology, symptoms and proposed treatments.

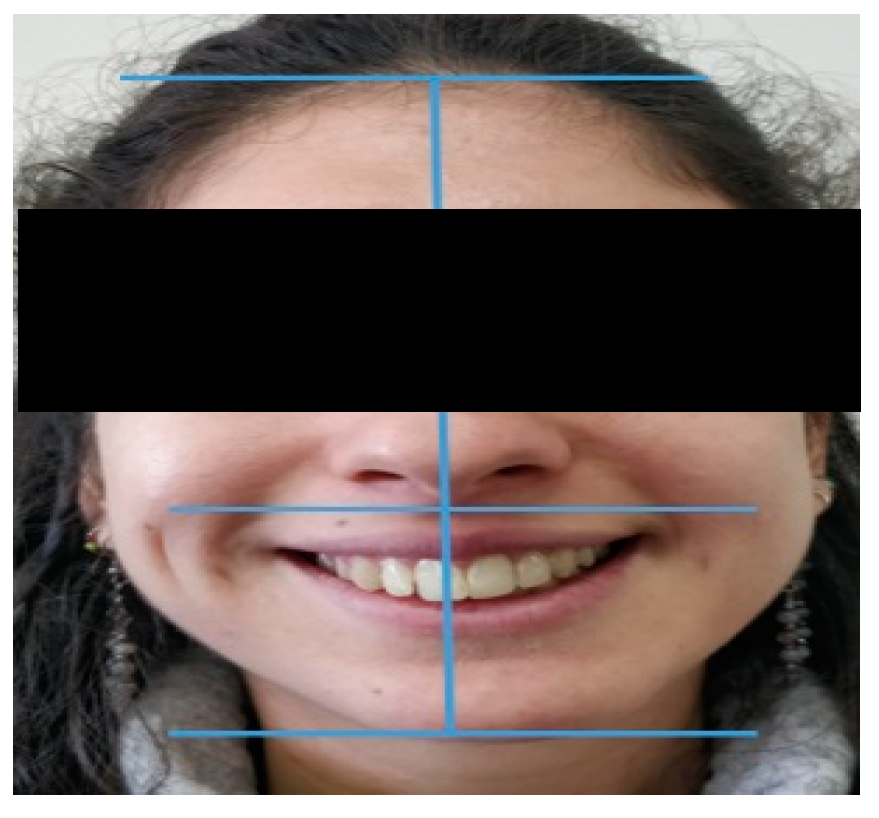

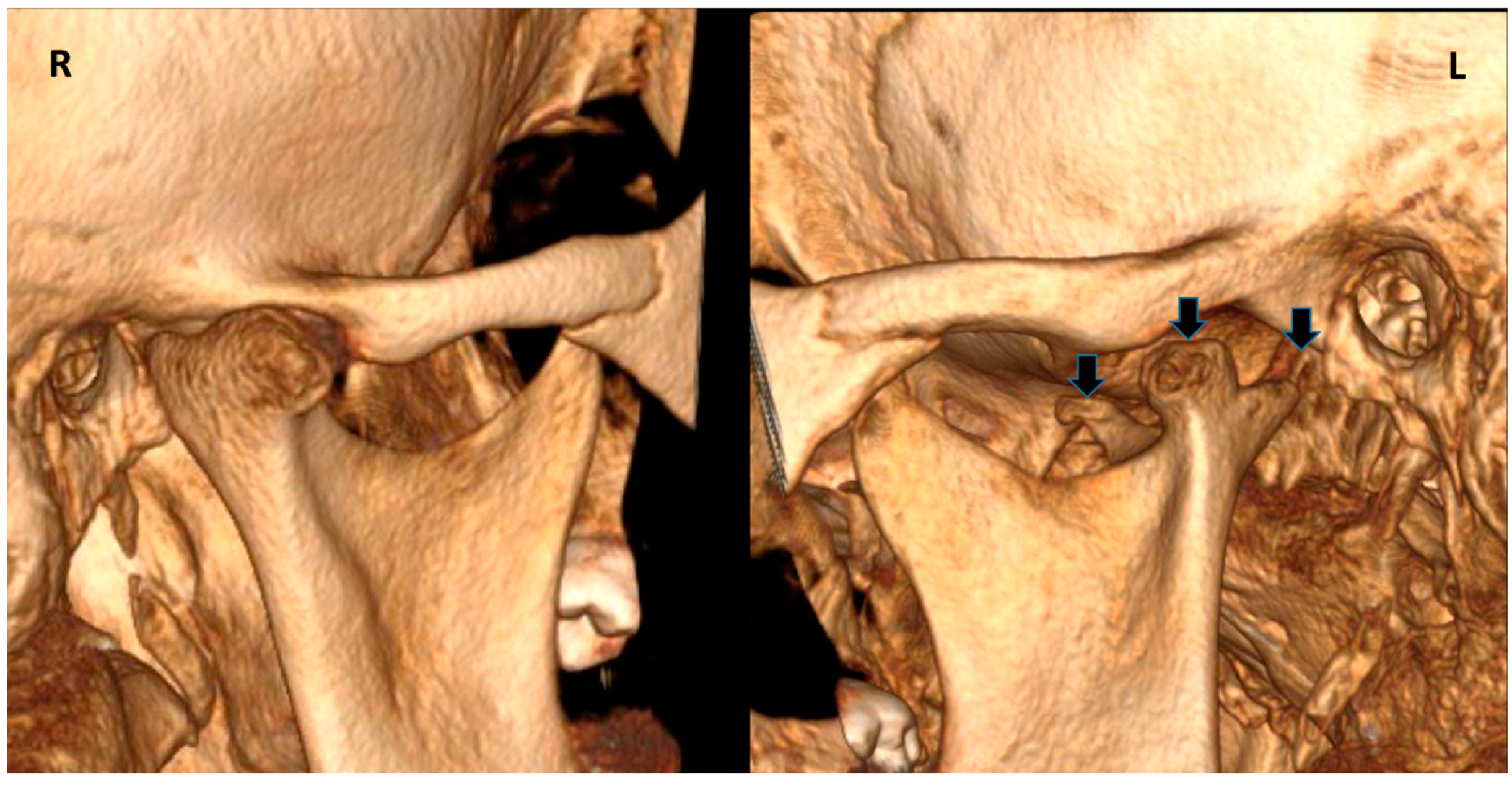

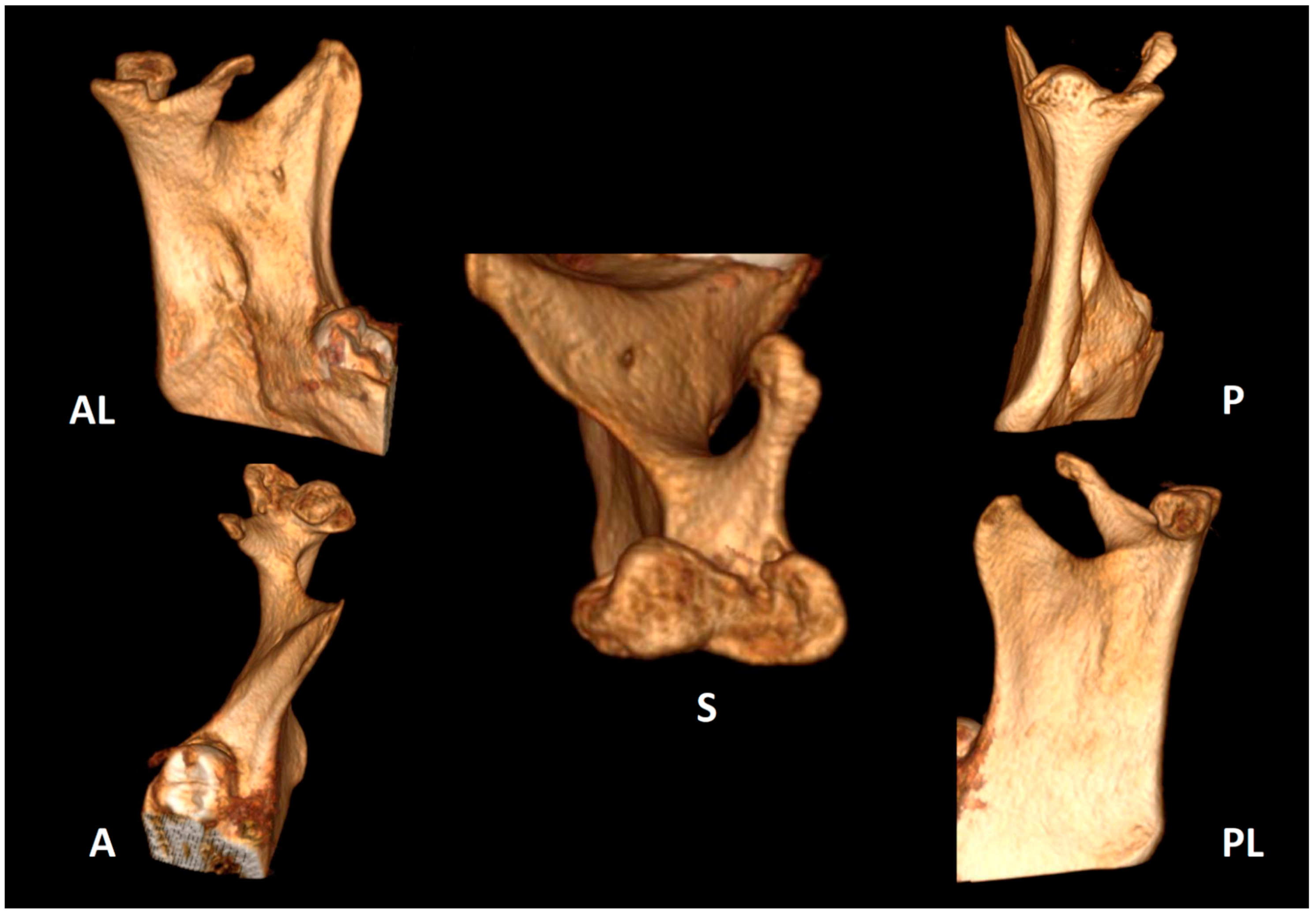

2. Case Report

3. Material and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prasanna, T.R.; Setty, S.; Udupa, V.V.; Sahana, D.S. Bilateral condylar anomaly: A case report and review. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2015, 19, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güven, O. A study on etiopathogenesis and clinical features of multi-headed (bifid and trifid) mandibular condyles and review of the literature. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, O.S.; Kayipmaz, S. Trifid mandibular condyle. Oral. Radiol. 2009, 25, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhekar, A.M.; Wanjari, P.V.; Phulambrikar, T. Unilateral trifid mandibular condyle: A case report. Cranio 2011, 29, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayat, A.; Boudaoud, Z.; Djafer, L. Trifid mandibular condyle: A case report and literature review. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 120, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo Millas, M.; Jorge, C.M.; Causa, M.E.U.; Melo, G.I.; Casals, R.M.; Brunetto, S.L.; Moncada, O.G. Bifid and trifydal condils in dysfunction of the tempo-mandibular joint: Report of clinical cases. Chil. J. Radiol. 2010, 16, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, A.; Khalid, M.; Sahoo, B. Posttraumatic bifid and trifid mandibular condyle with bilateral temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013, 24, e166–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Andara, A.; Ortega-Pertuz, A.I.; Guercio, E.; De Stefano, A. CT Findings of Trifid Mandibular Condyle in a 12 Year-Old Patient: A Case Report and Review. Int. J. Odontostomatol. 2017, 11, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gundlach, K.K.; Fuhrmann, A.; Beckmann-Van derVen, G. The double headed mandibular condyle. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. 1987, 64, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahman, H.; Etöz, O.A.; Sekerci, A.E.; Etöz, M.; Sisman, Y. Tetrafid mandibular condyle: A unique case report and review of the literature. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2011, 40, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menezes, A.V.; de Moraes Ramos, F.M.; de Vasconcelos-Filho, J.O.; Kurita, L.M.; de Almeida, S.M.; Haiter-Neto, F. The prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle detected in a Brazilian population. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2008, 37, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miloglu, O.; Yalcin, E.; Buyukkurt, M.; Yilmaz, A.; Harorli, A. The frequency of bifid mandibular condyle in a Turkish patient population. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2010, 39, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahman, H.; Sisman, Y.; Sekerci, A.E.; Tarim-Ertas, E.; Tokmak, T.; Tuna, I.S. Detection of bifid mandibular condyle using computed tomography. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2012, 1, e930–e934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrdlicka, A. Lower jaw: Double condyles. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1941, 28, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrás-Ferreres, J.; Sánchez-Torres, A.; Gay-Escoda, C. Bifid mandibular condyles: A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral. Y Cirugía Bucal 2018, 23, e672–e680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artvinli, L.B.; Kansu, O. Trifid mandibular condyle: A case report. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2003, 95, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagirankaya, L.B.; Hatipoglu, M.G. Trifid mandibular condyle: A case report. Cranio 2005, 23, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersek, N.; Ozbek, M.; Tasar, F.; Akpinar, E.; First, M. Bifid mandibular condyle: A case report. Dent. Traumatol. 2004, 20, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Garrido, L.; Gómez-González, S.; Gonzalo-Orden, J.M.; Wasterlain, S.N. Multi-headed (bifid and trifid) mandibular condyles in archaeological contexts: Two posttraumatic cases. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2022, 134, 105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniades, K.; Hadjipetrou, L.; Antoniades, V.; Paraskevopoulos, K. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2004, 97, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta-Junior, J.; Aita, T.G.; Pereira-Stabile, C.L.; Stabile, G.A. Congenital Frey’s syndrome associated with nontraumatic bilateral trifid mandibular condyle. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 42, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. 2014. Available online: https://ubwp.buffalo.edu/rdc-tmdinternational/tmd-assessmentdiagnosis/dc-tmd/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Shriki, J.; Lev, R.; Wong, B.F.; Sundine, M.J.; Hasso, A.N. Bifid mandibular condyle: CT and MR imaging appearance in two patients: Case report and review of the literature. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005, 26, 1865–1868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Femenia, M.; Sartorres-Nieto, M.; Berini-Aytés, L.; Gay-Escoda, C. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review. Cranio 2006, 24, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.H.; Yoon, K.H.; Park, K.S.; Park, J.A. Post-traumatic bifid mandibular condyle: A case report and literature review. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2016, 46, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haghnegahdar, A.A.; Bronoosh, P.; Khojastepour, L.; Tahmassebi, P. Prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle in a selected population in South of iran. J. Dent. 2014, 15, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Djae, K.A.; Li, Z.B. Post-traumatic bifid condyle: The pathogenesis analysis. Dent. Traumatol. 2011, 27, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahm, G.; Witt, E. Long-term results after childhood condylar fractures. A computer-tomographic study. Eur. J. Orthod. 1989, 11, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, J.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Salas, E.J.; Roselló-Llabrés, X. Bifid condyle: Review of the literature of the last 10 years and report of two cases. Cranio 2010, 28, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, F.C.; Yeo, J.F. Bifid mandibular condyle. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. 1990, 69, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.H.; Jung, Y.H. Nontraumatic bifid mandibular condyles in asymptomatic and symptomatic temporomandibular joint subjects. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2013, 43, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isık, D.; Sunay, M.; Bekerecioglu, M. A case with bifid mandibular condyle causing mandibular dislocation. East. J. Med. 2011, 16, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Balciunas, B.A. Bifid mandibular condyle. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 1986, 44, 324–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Ali, I.; Pal, U.S.; Bannerjee, K. Bifid mandibular condyle: Report of two cases of varied etiology. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 1, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Katti, G.; Najmuddin, M.; Fatima, S.; Unnithan, J. Bifid mandibular condyle. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, 69, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajashri, R.; Periasamy, S.; Kumar, S.P. Bifid Mandibular Condyle as the Hidden Cause for Temporomandibular Joint Disorder. Cureus 2021, 13, e17609. [Google Scholar]

- Stadnicki, G. Congenital double condyle of the mandible causing temporomandibular ankylosis: Report of a case. J. Oral. Surg. 1971, 29, 208–211. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Gender, Age | Signs & Symptoms | Etiology | Treatment | Follow Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artvinli and Kansu 2003 [16] | F, 25 | Anterior open bite Slight deviation of the mandible to the left Minor weakness after chewing | Trauma | FU | - |

| Antoniades K. et al., 2004 [20] | M, 15 | Mandibular hypoplasia, restricted mouth opening Snoring during sleep | Trauma | Muscle relaxants, occlusal splint, and wooden tongue spatulas | - |

| Çagirankaya & Hatipoglu 2005 [17] | F, 52 | Mandible deviated to the right | - | None | No alteration in TMJ functions one year after prosthetic rehabilitation |

| Sezgin & Katipman 2009 [3] | M, 31 | Mandible deviated to the right | Trauma | FU | - |

| Rodrigo Millas M. et al., 2010 [6] | F, 27 | Noise, click and unilateral TMJ pain Progressive joint hypomobility | - | - | - |

| Motta-Junior J. et al., 2012 [21] | M, 17 | Frey’s syndrome | - | Subcutaneous injection of botulinum toxin A (BTA) | 2 years with no complains |

| Jha A. et al., 2013 [7] | M, 6 | Severe restriction of movements of TMJ | Trauma | Physiotherapy & NSAIDs | - |

| Warhekar A. et al., 2014 [4] | F, 37 | Bilaterally asymmetrical face Diffuse painless swelling over the right masseteric region | Trauma | None | - |

| Prasanna T. et al., 2015 [1] | F, 26 | Mild facial asymmetry, micrognathia & deviation of the mandible to left | - | None | - |

| Hernández-Andara A. et al., 2017 [8] | M, 12 | Facial asymmetry & a clicking noise in the left TMJ | Trauma | FU | - |

| Ayat A. et al., 2018 [5] | F, 40 | Chin deviation to the right Pain in the right mandibular molar area | Trauma | None | - |

| Orhan Güven 2018 [2] | M, 19 | Chin deviation | Trauma | None | - |

| González-Garrido L. et al., 2022 [19] | M, +40 (skeletal individual) | - | Trauma | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zoabi, N.; Kats, L.; Ram, A.; Emodi-Perlman, A. Trifid Mandibular Condyle: Case Report and Current Review of the Literature. Life 2022, 12, 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12070976

Zoabi N, Kats L, Ram A, Emodi-Perlman A. Trifid Mandibular Condyle: Case Report and Current Review of the Literature. Life. 2022; 12(7):976. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12070976

Chicago/Turabian StyleZoabi, Nour, Lazar Kats, Alon Ram, and Alona Emodi-Perlman. 2022. "Trifid Mandibular Condyle: Case Report and Current Review of the Literature" Life 12, no. 7: 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12070976