Filtered Saliva for Rapid and Accurate Analyte Detection for POC Diagnostics

Abstract

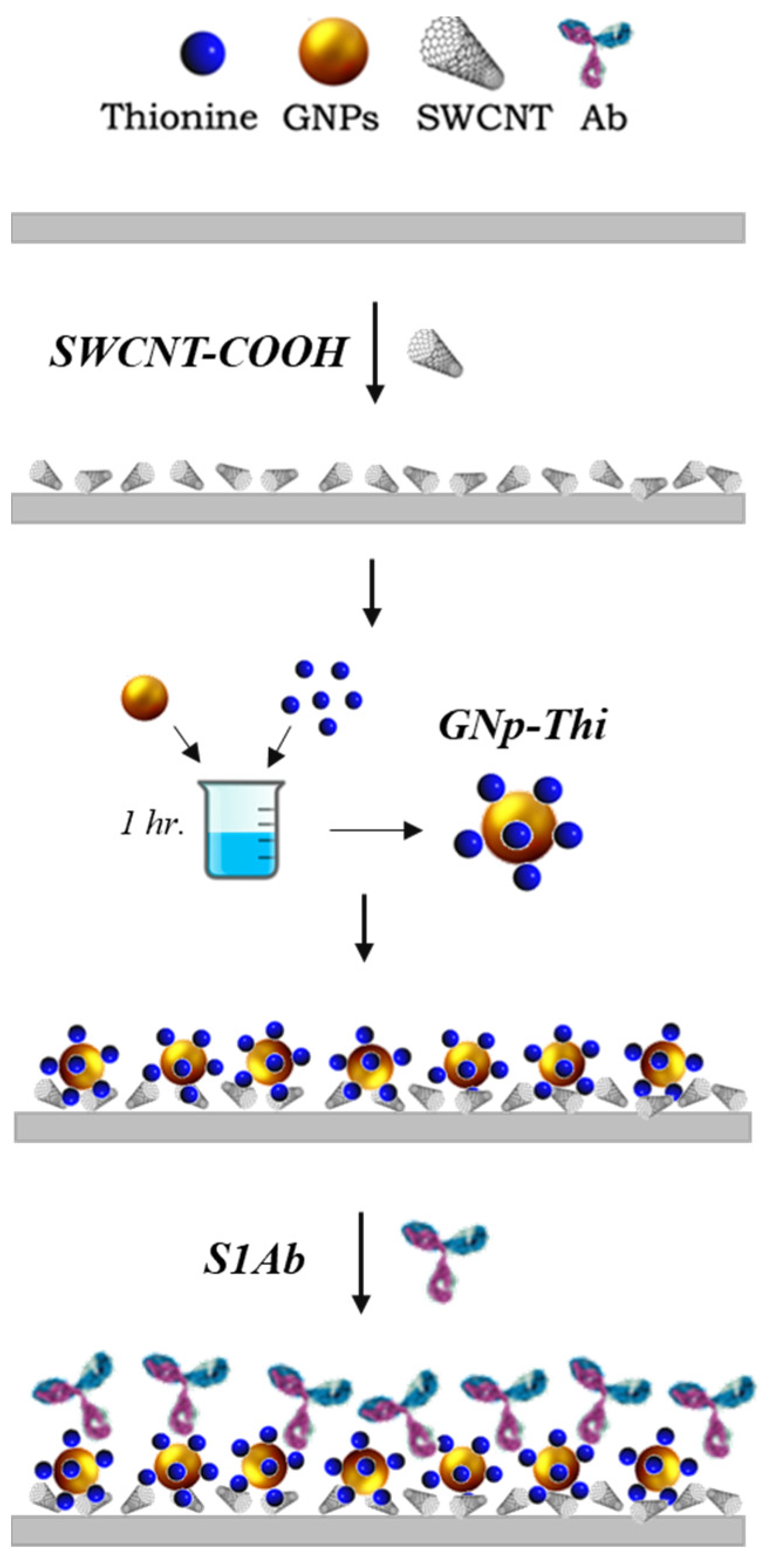

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Material and Method

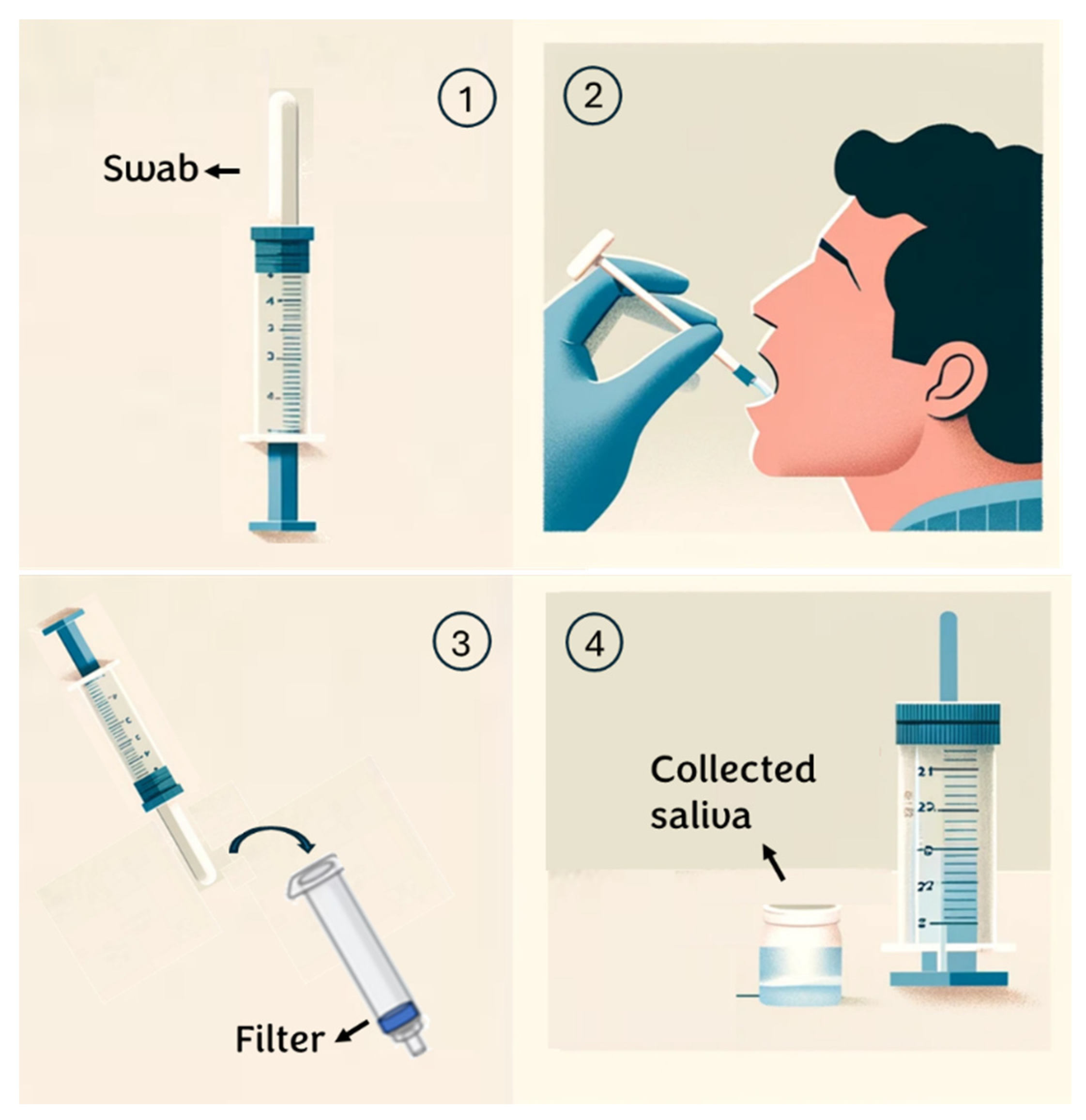

2.2. Saliva Sample Collection Protocols

- Individuals are instructed to rinse their mouths with water 15 min before saliva collection;

- An absorbent pad is positioned inside the mouth and participants are instructed to chew on it until it is saturated with saliva (typically taking 30 to 60 s);

- Subsequently, the saliva collector is inserted into a syringe containing a specific membrane/depth filter and the plunger is squeezed to extract the saliva from the absorbent pad;

- The sample is transferred into a sterile tube for subsequent analysis. (see Appendix A)

2.3. Viscosity and BCA Measurement

2.4. Biosensor Fabrication Procedure

2.4.1. SARS-CoV-2 Biosensor

2.4.2. Glucose Biosensor

2.5. Electrochemical Testing Procedure and Techniques

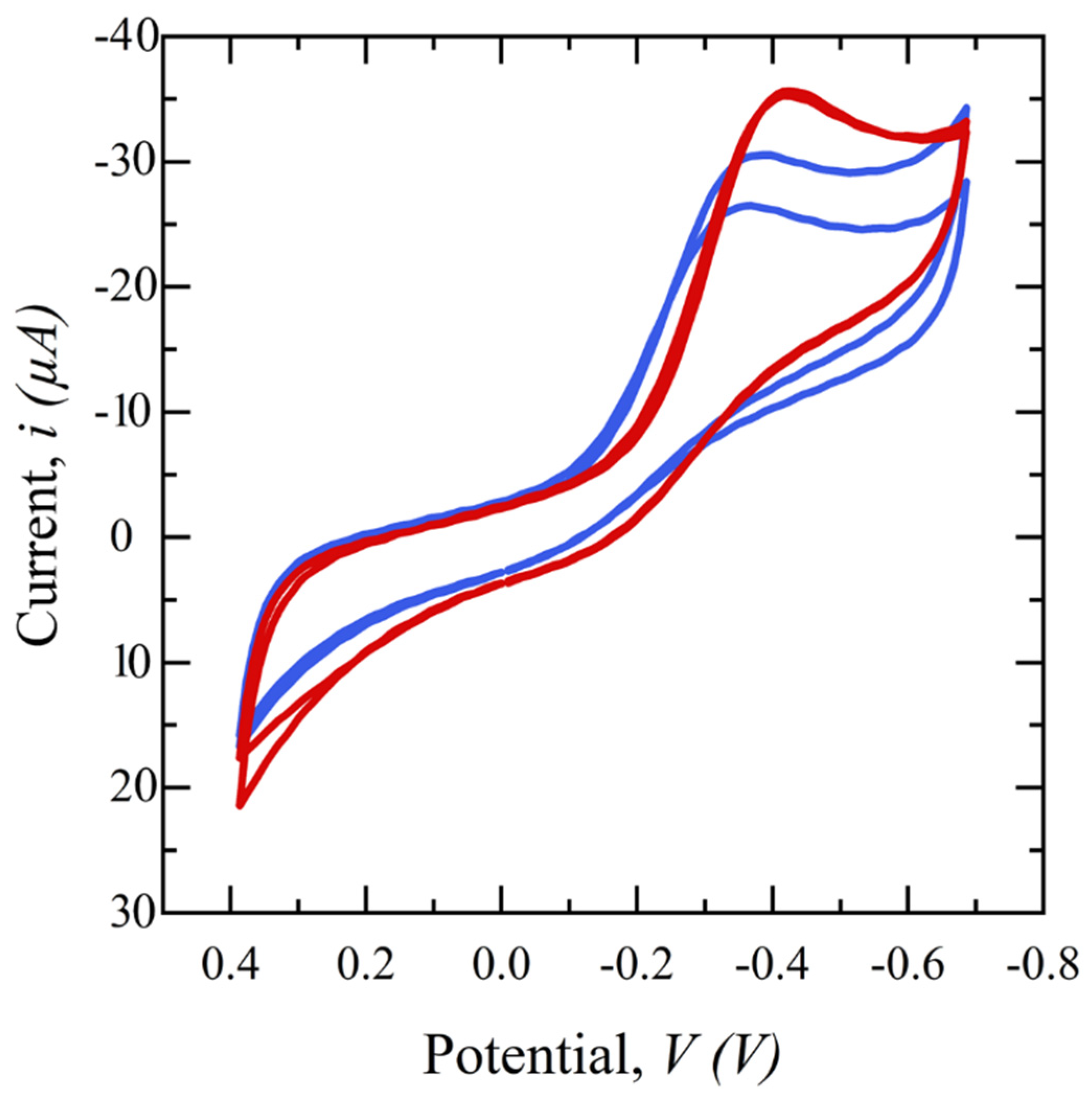

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Filter Assessment and Selection

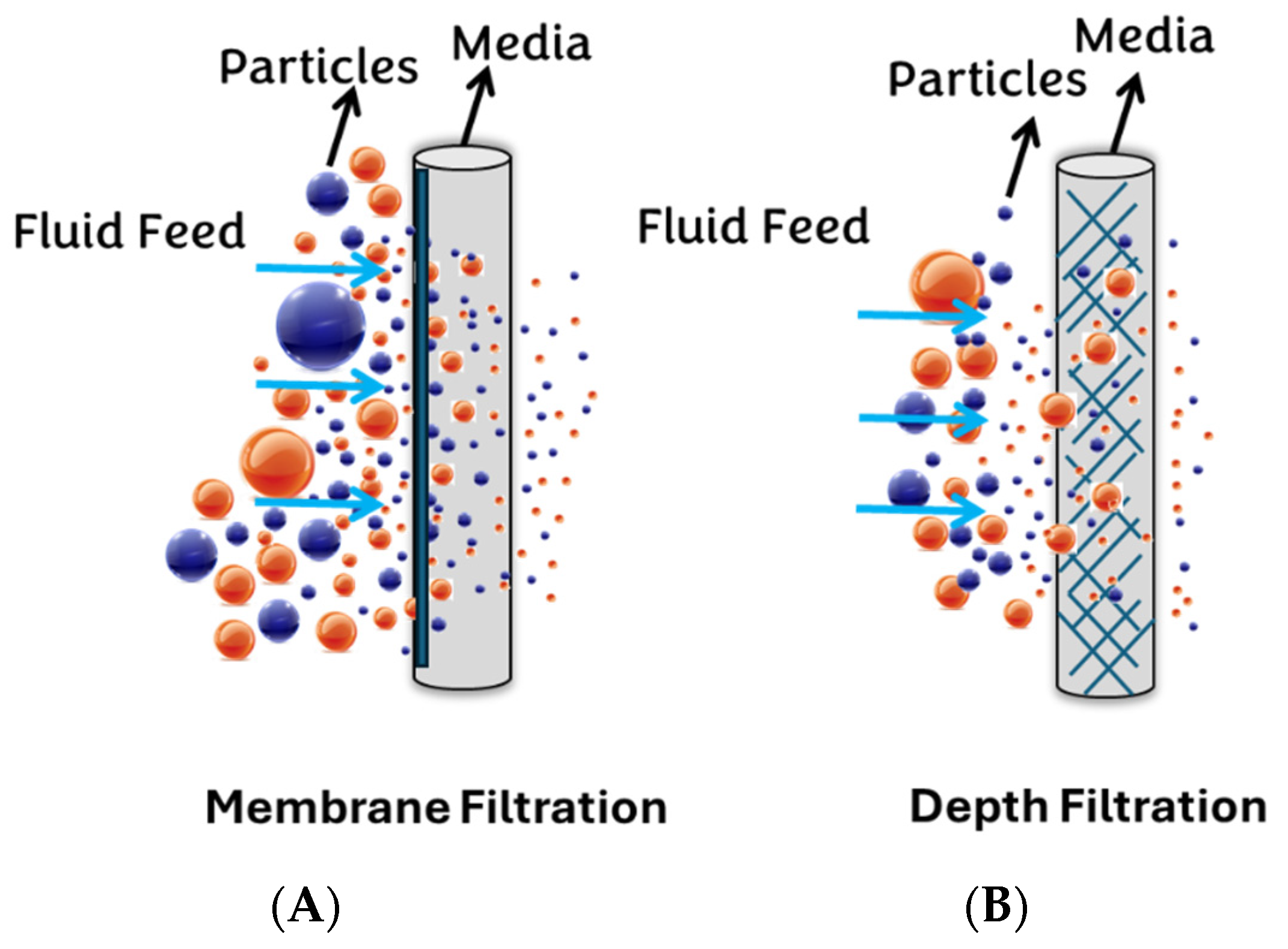

3.1.1. Syringe Membrane Filters

3.1.2. Depth Filters

3.1.3. Water Breakthrough Pressure

3.2. Filter Sensitivity Assessment

3.2.1. Salivary Glucose Measurement

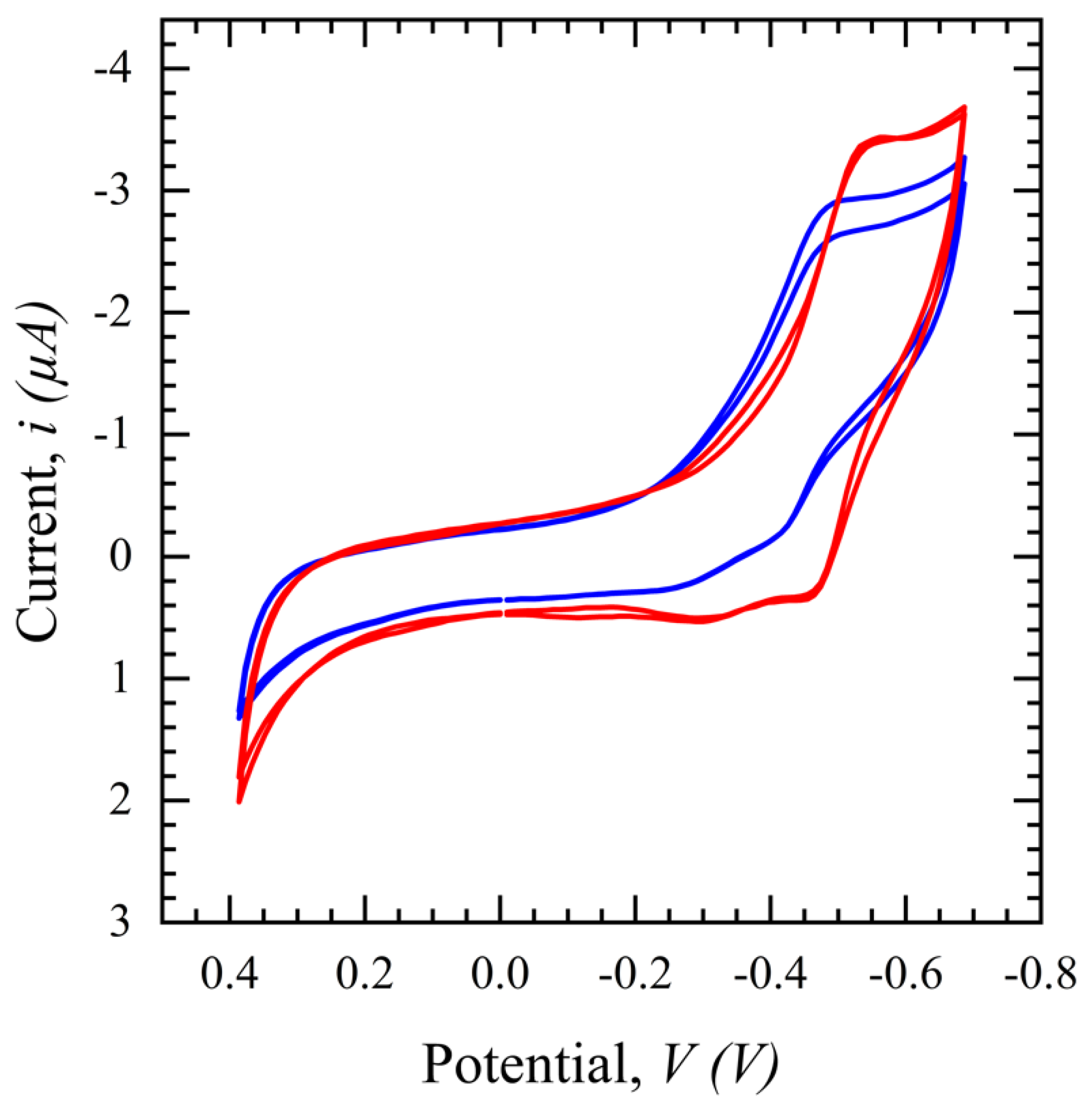

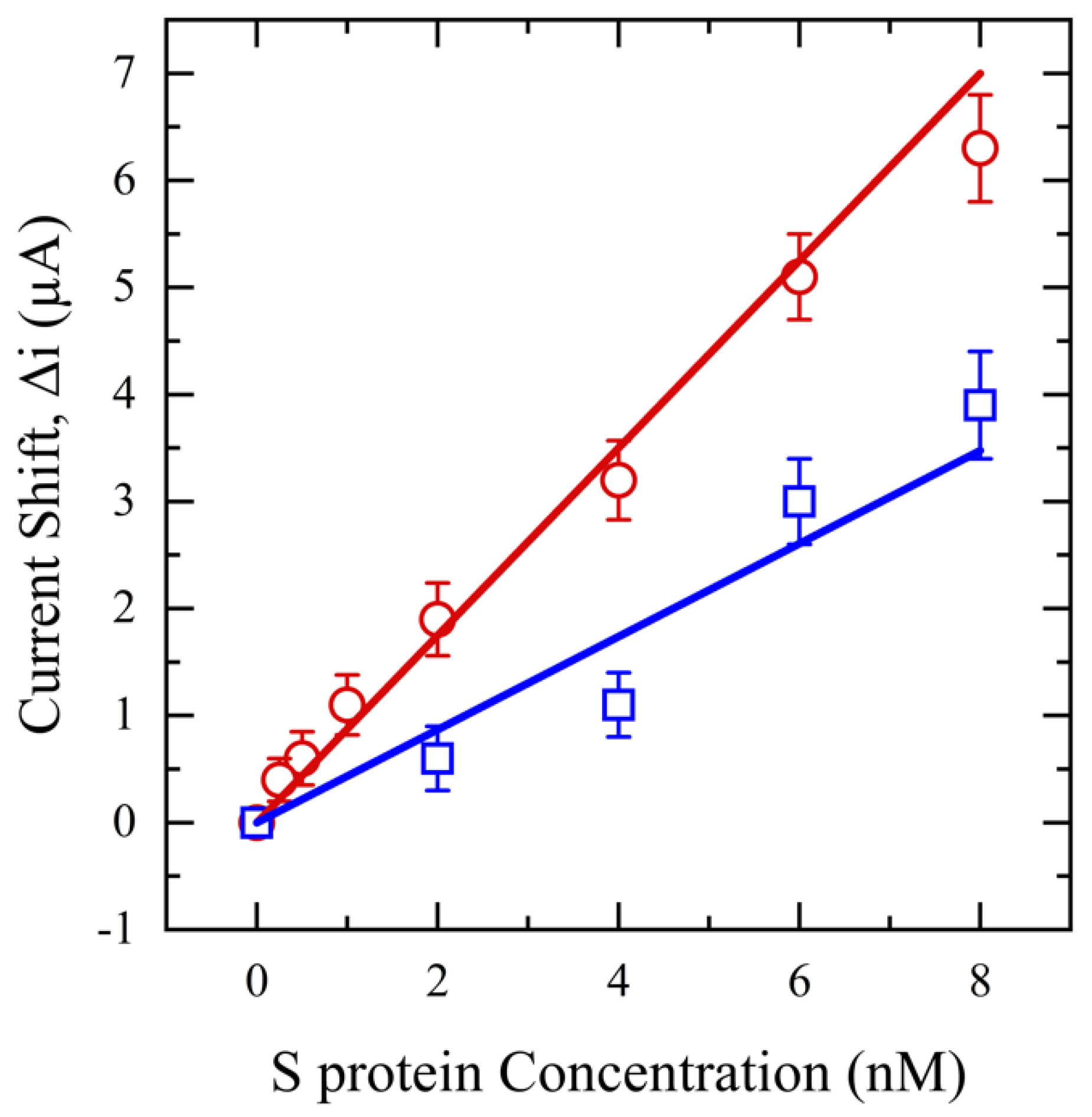

3.2.2. Salivary SASR-CoV-2 S Measurement

4. Conclusions

5. Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Florkowski, C.; Don-Wauchope, A.; Gimenez, N.; Rodriguez-Capote, K.; Wils, J.; Zemlin, A. Point-of-care testing (POCT) and evidence-based laboratory medicine (EBLM)—Does it leverage any advantage in clinical decision making? Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2017, 54, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfahani, I.C.; Sun, H. A droplet-based micropillar-enhanced acoustic wave (μPAW) device for viscosity measurement. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 350, 114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.T.S.G.; Souto, D.E.P.; Barragan, J.T.C.; Giarola, J.d.F.; de Moraes, A.C.M.; Kubota, L.T. Electrochemical biosensors in point-of-care devices: Recent advances and future trends. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 778–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liu, G.; Fan, C. Development of electrochemical immunosensors towards point of care diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. Electrochemical biosensors: Towards point-of-care cancer diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 21, 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsaei Vahid, N.; Marvi, M.R.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Naghib, S.M.; Ghaffarinejad, A. Effect of surfactant type on buckypaper electrochemical performance. Micro Nano Lett. 2018, 13, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, T.W.; Decsi, D.B.; Punyadeera, C.; Henry, C.S. Saliva-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Beduk, T.; Khushaim, W.; Ceylan, A.E.; Timur, S.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Salama, K.N. Electrochemical sensors targeting salivary biomarkers: A comprehensive review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 135, 116164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, D.; Dehghan Banadaki, M.; Bazargan, V.; Schaap, A. Numerical investigation of moving gel wall formation in a Y-shaped microchannel. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavani, S.A.; Jueckstock, J.; Su, J.; Kapravelos, A.; Kirda, E.; Lu, L. Browserprint: An Analysis of the Impact of Browser Features on Fingerprintability and Web Privacy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lamkin, M.S.; Oppenheim, F.G. Structural features of salivary function. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1993, 4, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.P.; Williamson, R.T. A review of saliva: Normal composition, flow, and function. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2001, 85, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, P.D.V.; Gregio, A.M.; Machado, M.A.; De Lima, A.A.; Azevedo, L.R. Saliva composition and functions: A comprehensive review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2008, 9, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wotman, S.; Mandel, I.D.; Thompson, R.H., Jr.; Laragh, J.H. Salivary electrolytes, urea nitrogen, uric acid and salt taste thresholds in hypertension. J. Oral Ther. Pharmacol. 1967, 3, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chauncey, H.H.; Lionetti, F.; Winer, R.A.; Lisanti, V.F. Enzymes of human saliva: I. The determination, distribution, and origin of whole saliva enzymes. J. Dent. Res. 1954, 33, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, P.P.; Parry, J.V. Detection of antibody to HIV in saliva: A brief review. Clin. Diagn. Virol. 1994, 2, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oba, I.T.; Spina, A.M.M.; Saraceni, C.P.; Lemos, M.F.; Senhoras, R.d.C.F.A.; Moreira, R.C.; Granato, C.F.H. Detection of hepatitis A antibodies by ELISA using saliva as clinical samples. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2000, 42, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, G.; Sheikh, S.; Pallagatti, S.; Singh, B.; Singh, V.A.; Singh, R. Saliva as a tool in the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen in patients. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2012, 33, 174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- González, V.; Martró, E.; Folch, C.; Esteve, A.; Matas, L.; Montoliu, A.; Grífols, J.R.; Bolao, F.; Tural, C.; Muga, R. Detection of hepatitis C virus antibodies in oral fluid specimens for prevalence studies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 27, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.; Khan, E.; Mali, M.; Latif, M. Human saliva can be a diagnostic tool for Zika virus detection. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfahani, I.C.; Ji, S.; Sun, H. A Drop-on-Micropillars (DOM) based Acoustic Wave Viscometer for High Viscosity Liquid Measurement. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 24224–24230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-K.; Chen, S.-Y.; Liu, I.J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-L.; Yang, C.-F.; Chen, P.-J.; Yeh, S.-H.; Kao, C.-L.; Huang, L.-M. Detection of SARS-associated coronavirus in throat wash and saliva in early diagnosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-I.; Kim, S.-G.; Kim, S.-M.; Kim, E.-H.; Park, S.-J.; Yu, K.-M.; Chang, J.-H.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, S.; Casel, M.A.B. Infection and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 704–709.e702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, S.; Farsaeivahid, N.; Grenier, C.; Yunqing, D.U.; Wang, M.L. Rapid Electrochemical Point-of-Care COVID-19 Detection in Human Saliva. Google Patents 17/351,211, 23 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jasim, H.; Carlsson, A.; Hedenberg-Magnusson, B.; Ghafouri, B.; Ernberg, M. Saliva as a medium to detect and measure biomarkers related to pain. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streckfus, C.F.; Bigler, L.R.; Zwick, M. The use of surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry to detect putative breast cancer markers in saliva: A feasibility study. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2006, 35, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, Y.; Itoi, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Sofuni, A.; Tsuchiya, T.; Tanaka, R.; Tonozuka, R.; Honjo, M.; Mukai, S.; Fujita, M. Elevated polyamines in saliva of pancreatic cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Wang, Y.; Hua, L.; Chen, A.; Zhang, Y. New method of lung cancer detection by saliva test using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Thorac. Cancer 2018, 9, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Zinger, T.; Inglima, K.; Woo, K.-M.; Atie, O.; Yurasits, L.; See, B.; Aguero-Rosenfeld, M.E. Performance of Abbott ID Now COVID-19 rapid nucleic acid amplification test using nasopharyngeal swabs transported in viral transport media and dry nasal swabs in a New York City academic institution. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurysta, C.; Bulur, N.; Oguzhan, B.; Satman, I.; Yilmaz, T.M.; Malaisse, W.J.; Sener, A. Salivary glucose concentration and excretion in normal and diabetic subjects. BioMed Res. Int. 2009, 2009, 430426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahid, N.F.; Marvi, M.R.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Naghib, S.M.; Ghaffarinejad, A. X-Fe2O4-buckypaper-chitosan nanocomposites for nonenzymatic electrochemical glucose biosensing. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 2019, 11, 930–942. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, S.; Munro, C.; Pickler, R.; Grap, M.J.; Elswick, R.K. Comparison of biomarkers in blood and saliva in healthy adults. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 246178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, L.F. Human saliva as a diagnostic specimen. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1621S–1625S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojnowska, S.; Baran, T.; Wilińska, I.; Sienicka, P.; Cabaj-Wiater, I.; Knaś, M. Human saliva as a diagnostic material. Adv. Med. Sci. 2018, 63, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizawa, J.M.; Schafer, C.A.; Schafer, J.J.; Farrell, J.J.; Paster, B.J.; Wong, D.T.W. Salivary biomarkers: Toward future clinical and diagnostic utilities. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirtcliff, E.A.; Granger, D.A.; Schwartz, E.; Curran, M.J. Use of salivary biomarkers in biobehavioral research: Cotton-based sample collection methods can interfere with salivary immunoassay results. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001, 26, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamchuea, K.; Chaisiwamongkhol, K.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Compton, R.G. Chemical analysis in saliva and the search for salivary biomarkers—A tutorial review. Analyst 2018, 143, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.H. The secretion, components, and properties of saliva. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 4, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquier, A.B.; Pita, A.K.D.C.; Busch, L.; Sánchez, G.A. Comparison of salivary levels of mucin and amylase and their relation with clinical parameters obtained from patients with aggressive and chronic periodontal disease. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfahani, I.C.; Ji, S.; Alamgir Tehrani, N.; Sun, H. An ultrasensitive micropillar-enabled acoustic wave (μPAW) microdevice for real-time viscosity measurement. Microsyst. Technol. 2023, 29, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsaeivahid, N.; Grenier, C.; Nazarian, S.; Wang, M.L. A rapid label-free disposable electrochemical salivary point-of-care sensor for SARS-CoV-2 detection and quantification. Sensors 2022, 23, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.L. Sensing of salivary glucose using nano-structured biosensors. Biosensors 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Hydrophobicity | Average Viscosity (mPa·s) | ΔM (%) | Protein Concentration (µg/mL) | Total Protein Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer | 1.04 | ||||

| Unfiltered saliva | 1.19 | 3001.21 | |||

| PVDF filtered saliva | Hydrophilic | 1.05 | 93 | 1500.60 | 50 |

| Anotop filtered saliva | Hydrophilic | 1.1 | 60 | 1680.67 | 44 |

| NY filtered saliva | Hydrophilic | 1.08 | 73 | 1710.68 | 43 |

| MCE filtered saliva | Hydrophilic | 1.06 | 86 | 1470.59 | 51 |

| Filter | Weight (mg) | ΔM (%) | Total Protein Reduction (%) | Change in Glucose Content (%) | Change in S protein Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW | 20 | 83.2 | 6 | 10 | 3 |

| NW | 30 | 85 | 10.7 | 17.3 | 14.3 |

| NW | 40 | 88.6 | 16.1 | 13.5 | 17.4 |

| GW | 20 | 75 | 14.4 | 0 | 13.1 |

| GW | 30 | 88.8 | 15.6 | 7.1 | 17.4 |

| GW | 40 | 87 | 21 | 9.4 | 24.5 |

| CW | 20 | 92 | 47.7 | 4.2 | 40 |

| CW | 30 | 96 | 58.7 | 2.3 | 50.2 |

| CW | 40 | 90 | 40.8 | 11.8 | 46 |

| Sample | Filter | Pressure (×100 kPa) | Force (N) (≈0.22481 lbs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | PVDF | 1 | 13.3 |

| Water | CW | 0.4 | 5.32 |

| Water | NW | 0.3 | 3.99 |

| Saliva | PVDF | 1.1 | 14.63 |

| Saliva | CW | 0.4 | 5.32 |

| Saliva | NW | 0.6 | 7.98 |

| Biomarker | SARS-CoV-2 S | Glucose |

|---|---|---|

| Filter | NW | CW |

| Weight (mg) | 20 | 30 |

| Hydrophobicity | Hydrophilic | Hydrophilic |

| (%) | 88.7 | 90 |

| Protein Reduction (%) | 6 | 60.7 |

| Change in S Protein Content (%) | 3 | 50.2 |

| Change in Glucose content (%) | 10 | 2.3 |

| Force (N) | 7.98 | 5.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farsaeivahid, N.; Grenier, C.; L. Wang, M. Filtered Saliva for Rapid and Accurate Analyte Detection for POC Diagnostics. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111088

Farsaeivahid N, Grenier C, L. Wang M. Filtered Saliva for Rapid and Accurate Analyte Detection for POC Diagnostics. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111088

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarsaeivahid, Nadia, Christian Grenier, and Ming L. Wang. 2024. "Filtered Saliva for Rapid and Accurate Analyte Detection for POC Diagnostics" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111088