Characterization and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Nosocomial Infections in a Saudi Tertiary Care Hospital over a Ten-Year Period (2012–2021)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Population

3.2. Resistance Patterns against Selected Antimicrobial Agents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferede, Z.T.; Tullu, K.D.; Derese, S.G.; Yeshanew, A.G. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Enterococcus species isolated from different clinical samples at Black Lion Specialized Teaching Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilema, A.; Moges, F.; Tadele, S.; Endris, M.; Kassu, A.; Abebe, W.; Ayalew, G. Isolation of enterococci, their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and associated factors among patients attending at the University of Gondar Teaching Hospital. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, C.A.; Murray, B.E. Emergence and management of drug-resistant Enterococcal infections. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2008, 6, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M Alatrouny, A.; Amin, M.A.; Shabana, H.S. Prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci among patients with nosocomial infections in intensive care unit. Al-Azhar Med. J. 2020, 49, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo Higuita, N.I.; Huycke, M.M. Enterococcal Disease, Epidemiology, and Implications for Treatment. In Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection [Internet]; Gilmore, M.S., Clewell, D.B., Ike, Y., Shankar, N., Eds.; Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Contreras, G.A.; Munita, J.M.; Arias, C.A. Novel Strategies for the Management of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2019, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, B. The impact of COVID-19 on bacterial antimicrobial resistance: Findings from a narrative review. J. Health Inform. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, U.; Al-Anazi, M.; Alanazi, Z.; Rodríguez-Baño, J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on multidrug-resistant gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens: A systematic review. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Westwood, D.; Daneman, N.; MacFadden, D.R. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: Rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbari Shiadeh, S.M.; Pormohammad, A.; Hashemi, A.; Lak, P. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in blood-isolated Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2713–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, C.; Mushtaq, S.; Allen, M.; Hope, R.; Gerver, S.; Longshaw, C.; Reynolds, R.; Woodford, N.; Livermore, D.M. Replacement of Enterococcus faecalis by Enterococcus faecium as the predominant Enterococcus in UK bacteraemias. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johargy, A.K.; Jamal, A.; Momenah, A.M.; Ashgar, S.S. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci in Saudi Arabia: Prevalence, antibiotic resistance, and susceptibility array. Pure Appl. Biol. (PAB) 2021, 5, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimen, C.; Berends, M.S.; Bathoorn, E.; Lokate, M.; Voss, A.; Friedrich, A.W.; Glasner, C.; Hamprecht, A. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in hospital settings across European borders: A scoping review comparing the epidemiology in the Netherlands and Germany. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2023, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro Marques, J.; Coelho, M.; Santana, A.R.; Pinto, D.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T. Dissemination of Enterococcal Genetic Lineages: A One Health Perspective. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa-Martínez, C.L.; Schuler, F.; Kampmeier, S. Sex differences in vancomycin-resistant enterococci bloodstream infections-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2021, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, C.; Carignan, A.; Bergevin, M.; Boulais, I.; Tremblay, V.; Robichaud, P.; Duperval, R.; Pepin, J. Secular changes in incidence and mortality associated with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in Quebec, Canada, 1991–2005. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupland, K.B.; Gregson, D.B.; Church, D.L.; Ross, T.; Pitout, J.D. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in a large Canadian region. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaillon, S.; Berthenet, K.; Garlanda, C. Sexual dimorphism in innate immunity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Martínez, E.R.; García-Gómez, E.; Camacho-Arroyo, I.; González-Pedrajo, B. Sexual dimorphism in bacterial infections. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2018, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, R.E.; Deshpande, L.; Streit, J.M.; Sader, H.S.; Castanheira, M.; Hogan, P.A.; Flamm, R.K. ZAAPS programme results for 2016: An activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using clinical isolates from medical centres in 42 countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Feßler, A.T.; Hanke, D.; Eichhorn, I.; Azcona-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Pérez-Moreno, M.O.; Seral, C.; Aspiroz, C.; Alonso, C.A.; Torres, L.; et al. Mechanisms of Linezolid Resistance Among Enterococci of Clinical Origin in Spain—Detection of optrA- and cfr(D)-Carrying E. faecalis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, B.; Wysocka, M.; Kotłowski, R.; Bronk, M.; Michalik, M.; Samet, A. Linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from one hospital in Poland -commensals or hospital-adapted pathogens? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misiakou, M.A.; Hertz, F.B.; Schønning, K.; Häussler, S.; Nielsen, K.L. Emergence of linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a tertiary hospital in Copenhagen. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, mgen001055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagetti, P.; Bonofiglio, L.; García Gabarrot, G.; Kaufman, S.; Mollerach, M.; Vigliarolo, L.; von Specht, M.; Toresani, I.; Lopardo, H.A. Resistance to β-lactams in enterococci. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschoalini, B.R.; Nuñez, K.V.M.; Maffei, J.T.; Langoni, H.; Guimarães, F.F.; Gebara, C.; Freitas, N.E.; dos Santos, M.V.; Fidelis, C.E.; Kappes, R.; et al. The Emergence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Characteristics in Enterococcus Species Isolated from Bovine Milk. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahansepas, A.; Aghazadeh, M.; Rezaee, M.A.; Hasani, A.; Sharifi, Y.; Aghazadeh, T.; Mardaneh, J. Occurrence of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium in Various Clinical Infections: Detection of Their Drug Resistance and Virulence Determinants. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, Y.; Hasani, A.; Ghotaslou, R.; Naghili, B.; Aghazadeh, M.; Milani, M.; Bazmany, A. Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterococci Isolated from Urinary Tract Infections. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 3, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Urusova, D.V.; Merriman, J.A.; Gupta, A.; Chen, L.; Mathema, B.; Caparon, M.G.; Khader, S.A. Rifampin resistance mutations in the rpoB gene of Enterococcus faecalis impact host macrophage cytokine production. Cytokine 2022, 151, 155788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Gawad, A.M.; Ashry, W.M.O.; El-Ghannam, S.; Hussein, M.; Yousef, A. Antibiotic resistance profile of common uropathogens during COVID-19 pandemic: A hospital-based epidemiologic study. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polly, M.; de Almeida, B.L.; Lennon, R.P.; Cortês, M.F.; Costa, S.F.; Guimarães, T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in an acute care hospital in Brazil. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.; Barnard, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare-acquired infections with multidrug-resistant organisms. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 653–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisini, A.; Boni, S.; Vacca, E.B.; Bobbio, N.; Del Puente, F.; Feasi, M.; Prinapori, R.; Lattuada, M.; Sartini, M.; Cristina, M.L.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Epidemiology of Antibiotic Resistance in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU): The Experience of a North-West Italian Center. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichel, V.M.; Last, K.; Brühwasser, C.; von Baum, H.; Dettenkofer, M.; Götting, T.; Grundmann, H.; Güldenhöven, H.; Liese, J.; Martin, M.; et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 141, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemapanpairoa, J.; Changpradub, D.; Thunyaharn, S.; Santimaleeworagun, W. Does Vancomycin Resistance Increase Mortality? Clinical Outcomes and Predictive Factors for Mortality in Patients with Enterococcus faecium Infections. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubler, S.; Lenz, M.; Zimmermann, S.; Richter, D.C.; Weiss, K.H.; Mehrabi, A.; Mieth, M.; Bruckner, T.; Weigand, M.A.; Brenner, T.; et al. Does vancomycin resistance increase mortality in Enterococcus faecium bacteraemia after orthotopic liver transplantation? A retrospective study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Samples | VRE | VSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic—No. (%) | n = 1034 | n = 164 (15.9) | n = 870 (84.1) | p Value |

| Sex | 0.01 b | |||

| Man | 647 (62.6) | 88 (53.7) | 559 (64.3) | |

| Woman | 387 (37.4) | 76 (46.3) | 311 (35.7) | |

| Hospitalization ward | <0.001 a | |||

| ICU | 305 (29.5) | 76 (46.4) | 229 (26.3) | |

| General ward | 729 (70.5) | 88 (53.6) | 641 (73.7) | |

| Enterococci species | <0.001 a | |||

| E. faecalis | 561 (54.3) | 15 (9.1) | 546 (62.8) | |

| E. faecium | 347 (33.6) | 143 (87.2) | 204 (23.4) | |

| Other | 126 (12.2) | 6 (3.7) | 120 (13.8) | |

| Culture source | <0.001 a | |||

| Abscess | 60 (5.8) | 8 (4.9) | 52 (6) | |

| Ascitic fluid | 21 (2) | 7 (4.3) | 14 (1.6) | |

| Blood | 203 (19.6) | 54 (32.9) | 149 (17.1) | |

| CSF | 11 (1.1) | 2 (1.2) | 9 (1) | |

| Respiratory | 49 (4.7) | 3 (1.8) | 46 (5.3) | |

| Soft tissue | 10 (1) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (1) | |

| Urine | 521 (50.4) | 69 (42.1) | 452 (52) | |

| Wound | 120 (11.6) | 17 (10.4) | 103 (11.8) | |

| Other | 39 (3.8) | 3 (1.8) | 36 (4.1) | |

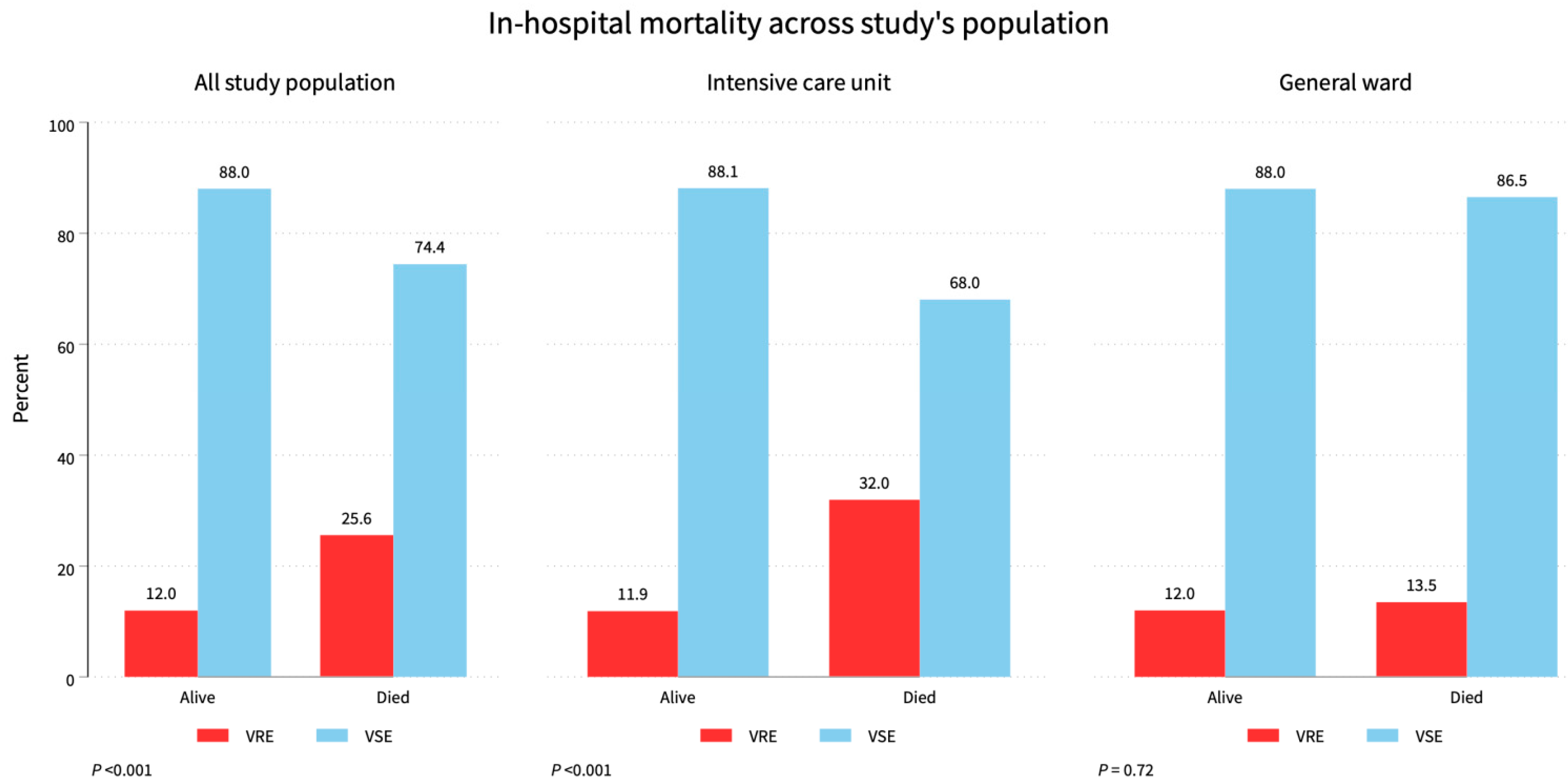

| Patient outcome c | <0.001 a | |||

| Alive | 710 (73.3) | 85 (56.3) | 625 (76.5) | |

| Died | 258 (26.7) | 66 (43.7) | 192 (23.5) | |

| Year | 0.02 b | |||

| 2012 | 48 (4.6) | 10 (6.1) | 38 (4.4) | |

| 2013 | 102 (9.9) | 12 (7.3) | 90 (10.3) | |

| 2014 | 60 (5.8) | 6 (3.7) | 54 (6.2) | |

| 2015 | 66 (6.4) | 8 (4.9) | 58 (6.7) | |

| 2016 | 89 (8.6) | 9 (5.5) | 80 (9.2) | |

| 2017 | 102 (9.9) | 13 (7.9) | 89 (10.2) | |

| 2018 | 103 (10) | 15 (9.1) | 88 (10.1) | |

| 2019 | 160 (15.5) | 28 (17.1) | 132 (15.2) | |

| 2020 | 141 (13.6) | 27 (16.5) | 114 (13.1) | |

| 2021 | 163 (15.8) | 36 (22) | 127 (14.6) |

| Total | Ampicillin | Ciprofloxacin | Daptomycin | Linezolid | Rifampin | Vancomycin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococci Species—No. (%) | n = 1034 | n = 939 | n = 625 | n = 524 | n = 913 | n = 453 | n = 1034 |

| E. avium | 1 (0.1) | S | S | S | S | NA | S |

| E. casseliflavus | 4 (0.4) | S | S | NA | S | NA | 3 (75) |

| E. durans | 1 (0.1) | S | NA | NA | S | NA | S |

| E. faecalis | 561 (54.3) | 62 (11.8) | 224 (59.7) | S | 8 (1.5) | 56 (20.1) | 15 (2.7) |

| E. faecium | 347 (33.6) | 253 (81.6) | 174 (84.1) | 1 (0.6) | 10 (3.1) | 124 (80) | 143 (41.2) |

| E. gallinarum | 6 (0.6) | 3 (50) | 3 (60) | S | S | 2 (50) | 3 (50) |

| E. hirae | 3 (0.3) | S | NA | NA | S | NA | S |

| E. raffinosus | 1 (0.1) | R | S | S | S | S | S |

| Other | 110 (10.6) | 21 (23.9) | 18 (51.4) | S | S | 3 (20) | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Bshabshe, A.; Algarni, A.; Shabi, Y.; Alwahhabi, A.; Asiri, M.; Alasmari, A.; Alshehry, A.; Mousa, W.F.; Noreldin, N. Characterization and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Nosocomial Infections in a Saudi Tertiary Care Hospital over a Ten-Year Period (2012–2021). Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111190

Al Bshabshe A, Algarni A, Shabi Y, Alwahhabi A, Asiri M, Alasmari A, Alshehry A, Mousa WF, Noreldin N. Characterization and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Nosocomial Infections in a Saudi Tertiary Care Hospital over a Ten-Year Period (2012–2021). Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111190

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Bshabshe, Ali, Abdullah Algarni, Yahya Shabi, Abdulrahman Alwahhabi, Mohammed Asiri, Ahmed Alasmari, Adil Alshehry, Wesam F. Mousa, and Nashwa Noreldin. 2024. "Characterization and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Nosocomial Infections in a Saudi Tertiary Care Hospital over a Ten-Year Period (2012–2021)" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111190

APA StyleAl Bshabshe, A., Algarni, A., Shabi, Y., Alwahhabi, A., Asiri, M., Alasmari, A., Alshehry, A., Mousa, W. F., & Noreldin, N. (2024). Characterization and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Enterococcus Species Isolated from Nosocomial Infections in a Saudi Tertiary Care Hospital over a Ten-Year Period (2012–2021). Diagnostics, 14(11), 1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111190