The Frequency of Risk Factors for Cleft Lip and Palate in Mexico: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

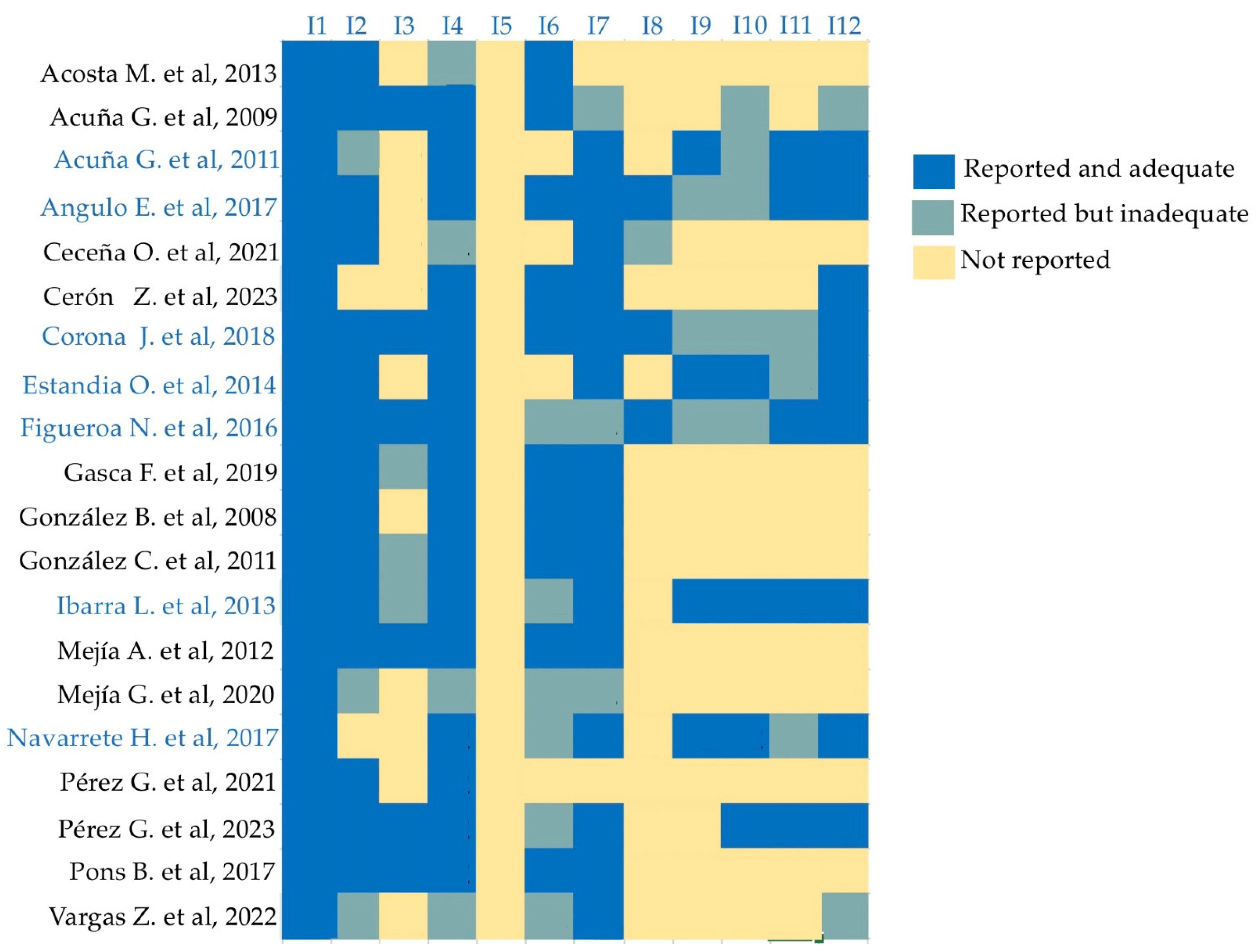

2.4. Data Extraction and Evaluation

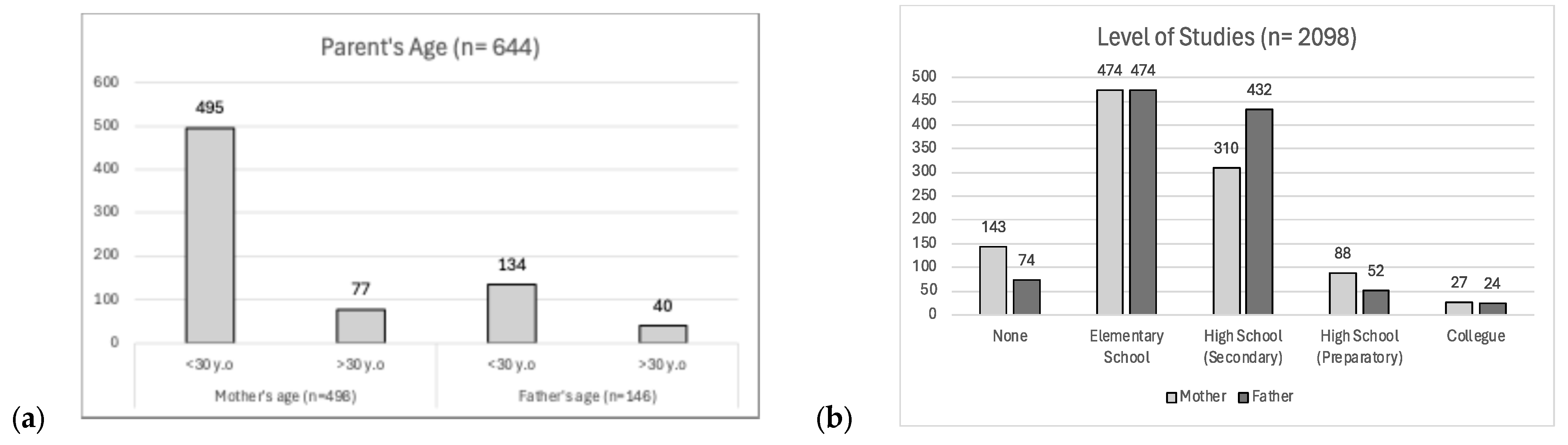

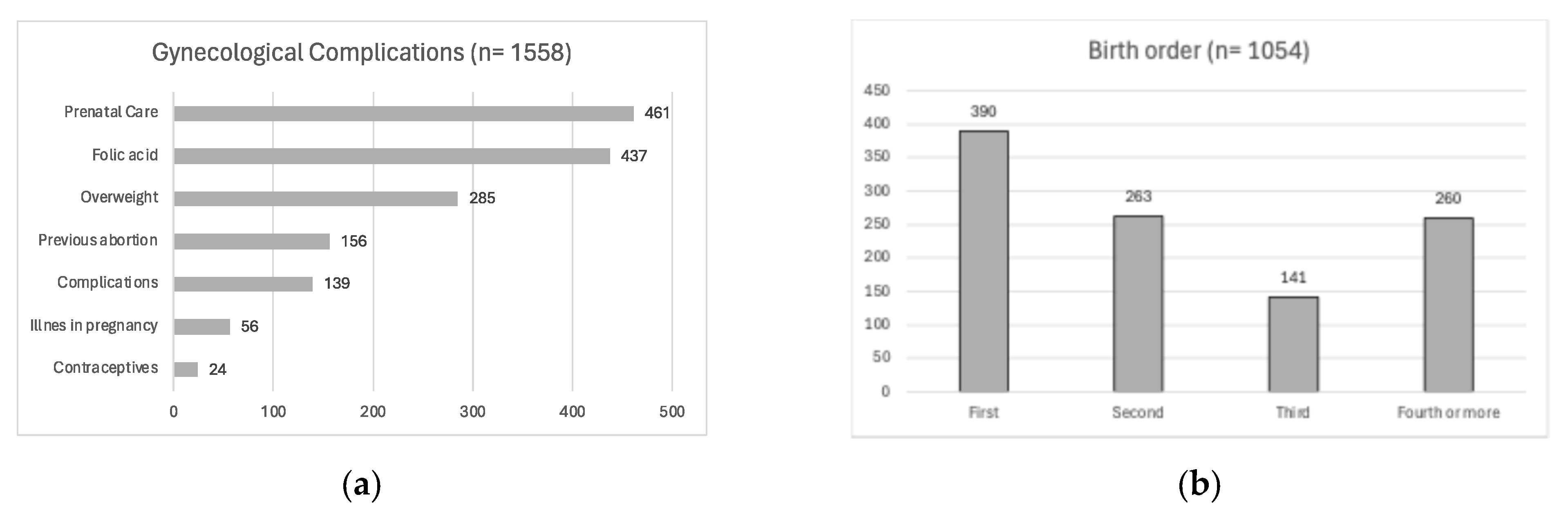

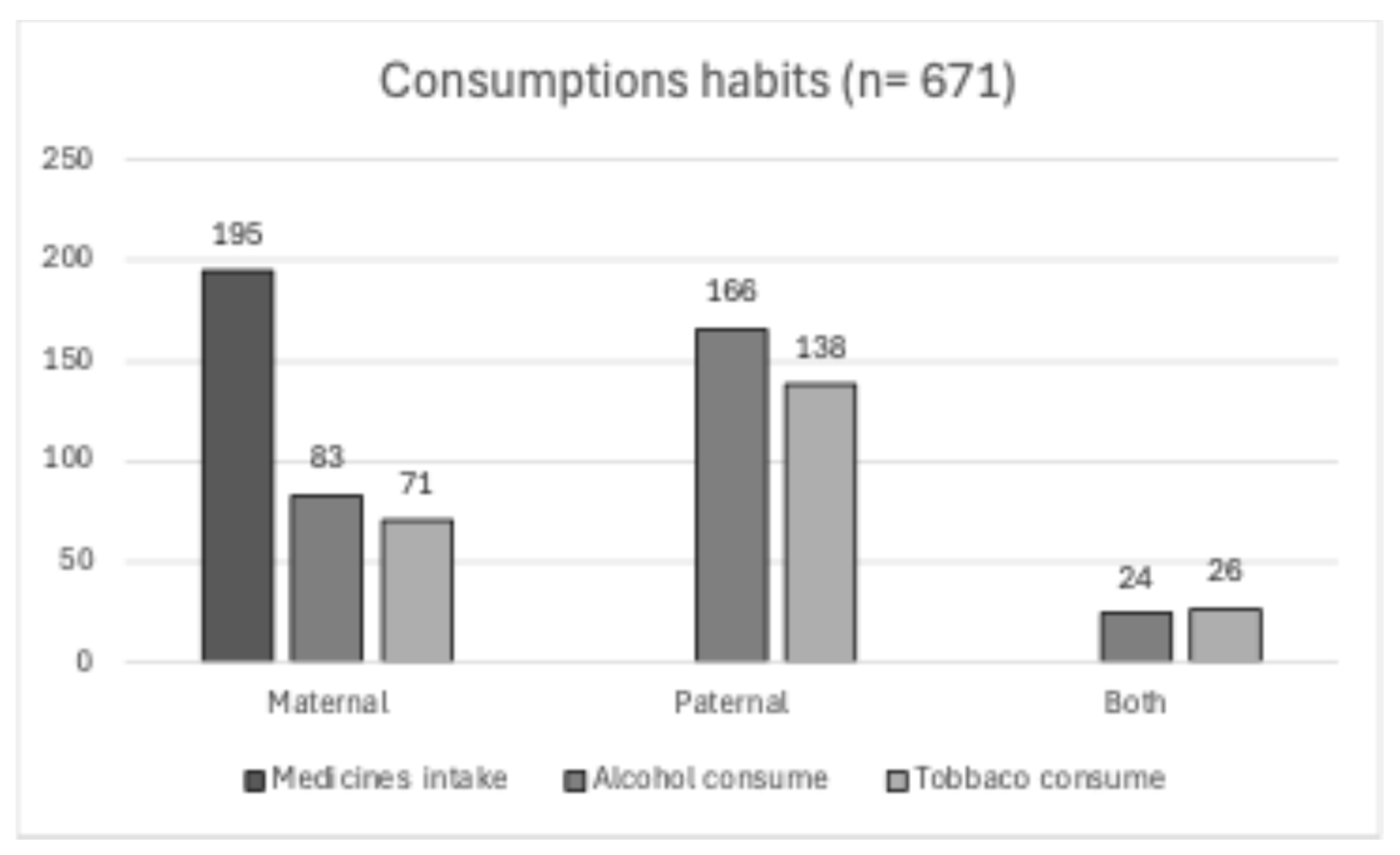

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suazo, J. Environmental factors in non-syndromic orofacial clefts: A review based on meta-analyses results. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Tian, S.; Jiao, X.; Mi, N.; Zhang, B.; Song, T.; An, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhuang, D. Association of Parental Environmental Exposures and Supplementation Intake with Risk of Nonsyndromic Orofacial Clefts: A Case-Control Study in Heilongjiang Province, China. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7172–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH. El Labio Leporino y el Paladar Hendido. Instituto Nacional de Investigación Dental y Craneofacial [Citado Enero 2021]. Available online: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/espanol/temas-de-salud/labio-leporino-paladar-hendido (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Han, J.; Shimizu, T.; Shimizu, K.; Maeda, T. Detection of informative markers for searching a causative gene(s) of cleft lip with palate in a/wysn mice. Pediatr. Dent. J. 2005, 15, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babai, A.; Irving, M. Orofacial Clefts: Genetics of Cleft Lip and Palate. Genes 2023, 9, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.; Bustos, I.; Quintero, C.; Giraldo, A. Factores de riesgo para algunas anomalías congénitas en población colombiana. Rev. Salud Pública 2001, 3, 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, B.O. Treatment of Cleft Lip and Palate during The Revolutionary War: Bicentennial Reflections (An Invited Article). Cleft Palate J. 1976, 13, 371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Mossey, P.A.; Little, J.; Munger, R.G.; Dixon, M.J.; Shaw, W.C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 2009, 374, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-González, G.; Escoffie-Ramírez, M.; Medina-Solis, C.E.; Casanova-Rosado, J.F.; Pontigo-Loyola, A.P.; Villalobos-Rodelo, J.J.; de Márquez-Corona, M.L.; Granillo, H.I. Caracterización epidemiológica del labio y/o paladar hendido no sindrómico Estudio en niños de 0–12 años de edad en Campeche e Hidalgo. Rev. ADM 2009, 66, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Altoé, S.R.; Borges, A.H.; Campos Neves, A.T.S.; Fábio Aranha, A.M.; Meireles Borba, A.; Martinez Espinosa, M.; Ricci Volpato, L.E. Influence of Parental Exposure to Risk Factors in the Occurrence of Oral Clefts. J. Dent. 2020, 21, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Palmieri, A.; Carinci, F.; Scapoli, L. Non-syndromic Cleft Palate: An Overview on Human Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM. 034-SSA2-2013. 2013. Available online: http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/034ssa202.html (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Navarrete-Hernández, E.; Canún-Serrano, S.; Valdés-Hernández, J.; Reyes-Pablo, A.E. Prevalencia de labio hendido con o sin paladar hendido en recién nacidos vivos. México, 2008–2014. Rev. Mex. Ped. 2017, 84, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatwoski, F.; Panisi, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new imstrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, N.P.F.; Acosta, H.F.M.; Espinoza, M.E.N.; Higuera, N.A.S.; Partida, E.A.B.; Espinoza, M.A.I. Evaluación de factores de riesgo maternos y ambientales asociados a labio y paladar hendidos durante el primer trimestre de embarazo. Rev. Mex. Cir. Bucal Maxilofac. 2016, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Angulo-Castro, E.; Acosta-Alfaro, L.F.; Guadron-Llanos, A.M.; Canizalez-Román, A.; Gonzalez-Ibarra, F.; Osuna-Ramírez, I.; Murillo-Llanes, J. Maternal Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate in Mexico: A Case-Control Study. Iran. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 29, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasca-Sanchez, F.M.; Santos-Guzman, J.; Elizondo-Dueñaz, R.; Mejia-Velazquez, G.M.; Ruiz-Pacheco, C.; Reyes-Rodriguez, D.; Vazquez-Camacho, E.; Hernandez-Hernandez, J.A.; Lopez-Sanchez, R.d.C.; Ortiz-Lopez, R.; et al. Spatial Clusters of Children with Cleft Lip and Palate and Their Association with Polluted Zones in the Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 12, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Rivera, J.R.; Bobadilla-Morales, L.; Corona-Rivera, A.; Peña-Padilla, C.; Olvera-Molina, S.; Orozco-Martín, M.A.; García-Cruz, D.; Ríos-Flores, I.M.; Gómez-Rodríguez, B.G.; Rivas-Soto, G.; et al. Prevalence of orofacial clefts and risks for non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in newborns at a university hospital from West Mexico. Congenit. Anom. 2018, 58, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceceña-Mateos, O.A.; Robles-Cervantes, J.A.; Ledezma-Rodríguez, J.C.; González-Gutiérrez, H.O.; Gómez-Díaz, A.E.; Ledezma-Gómez, V. Relación de variables demográficas y presencia de labio y paladar hendido en pacientes atendidos en el Instituto Jalisciense de Cirugía Reconstructiva Dr. José Guerrero Santos. Cir. Plástica 2021, 31, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Bonals, A.; Pons-Bonals, L.; Hidalgo-Martínez, S.M.; Sosa-Ferreyra, C.F. Estudio clínico-epidemiológico en niños con labio paladar hendido en un hospital de segundo nivel. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 2017, 74, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra-Lopez, J.J.; Duarte, P.; Antonio-Vejar, V.; Calderon-Aranda, E.S.; Huerta-Beristain, G.; Flores-Alfaro, E.; Moreno-Godinez, M.E. Maternal C677T MTHFR polymorphism and environmental factors are associated with cleft lip and palate in a Mexican population. J. Investig. Med. 2013, 61, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-González, G.; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Maupomé, G.; Escoffie-Ramírez, M.; Hernández-Romano, J.; Márquez-Corona Mde, L.; Islas-Márquez, A.J.; Villalobos-Rodelo, J.J. Family history and socioeconomic risk factors for non-syndromic cleft lip and palate: A matched case-control study in a less developed country. Biomedica 2011, 31, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Zacatenco, G.; Hernández-Trejo, N.G.; Cabrera-Serrano, M.S.; Gutierrez-Brito, M. Prevalencia de factores de riesgo asociados a la presencia de fisuras labiales y palatinas en pacientes que acudieron al Hospital para el Niño Poblano, en el periodo de enero de 2018 a diciembre de 2019. Oral 2022, 23, 2050–2056. [Google Scholar]

- González, B.S.; López, M.L.; Rico, M.A.; Garduño, F. Oral clefts: A retrospective study of prevalence and predisposal factors in the State of Mexico. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 50, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía, A.C.; Suárez, D.E. Factores de riesgo materno predominantes asociados con labio leporino y paladar hendido en los recién nacidos. Arch. Investig. Matern. Infant. 2012, 4, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, G.G.; Hidalgo, H.O.M.; Arizmendi, L.J.D.; Cruz, E.C. Estudio epidemiológico de pacientes con labio y paladar fisurado en dos centros especializados. Rev. Odont. Mex. 2020, 24, 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, M.R.; Montes, D.P.; Flores Mesa, B.; Mónica, D.; Rangel, A. Frecuencia y factores de riesgo en labio y paladar hendidos del Centro Médico Nacional «La Raza». Rev. Mex. Cir. Bucal Maxilofac. 2013, 9, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Estandia-Ortega, B.; Velázquez-Aragón, J.A.; Alcántara-Ortigoza, M.A.; Reyna-Fabian, M.E.; Villagómez-Martínez, S.; González-del Angel, A. 5,10Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase single nucleotide polymorphisms and gene-environment interaction analysis in non-syndromic cleft lip/palate. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2014, 122, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-González, A.; Lavielle-Sotomayor, P.; Clark, P.; Tusie-Luna, M.T.; Palafox, D. Factores de riesgo en pacientes con fisura de labio y paladar en México. Estudio en 209 pacientes. Cir. Plást. Iberolatinoam. 2021, 47, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, A.; Lavielle-Sotomayor, P.; López-Rodríguez, L.; Pérez-Días, M.E.; Vega-Hernández, D.; Domínguez, J.N.; Clark, P. Characterization of 554 Mexican Patients With Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip and Palate: Descriptive Study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2023, 34, 1776–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Osorio, C.A.; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Pontigo-Loyola, A.P.; Casanova-Rosado, J.F.; Escoffié-Ramírez, M.; Corona-Tabares, M.G.; Maupomé, G. Estudio ecológico en México (2003–2009) sobre labio y/o paladar hendido y factores sociodemográficos, socioeconómicos y de contaminación asociados. An. Pediatría 2011, 74, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Zamora, E.; Scougall-Vichis, R.J.; Contreras-Bulnes, R.; González-López, B.S.; Vera-Hernández, M.A.; Lucas-Rincón, S.E.; Escoffié-Ramírez, M.; Medina-Solis, C. Trends in cleft lip and/or palate prevalence at birth in Mexico. A national (ecological) study between 2003 and 2019. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2023, 60, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkin, I.; Barrès, R. Sperm epigenetics and influence of environmental factors. Mol. Metab. 2018, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, R.H.; Wilcox, A.J.; Moen, B.E.; McConnaughey, D.R.; Lie, R.T. Parent.s occupation and isolated orofacial clefts in Norway: A population-based case-control study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007, 17, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bille, C.; Skytthe, A.; Vach, W.; Knudsen, L.B.; Andersen, A.M.N.; Murray, J.C.; Christensen, K. Parent’s age and the risk of oral clefts. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, O.; Erinoso, O.A.; Ogunlewe, A.O.; Adeyemo, W.L.; Ladeinde, A.L.; Ogunlewe, M.O. Parental Age and the Risk of Cleft Lip and Palate in a Nigerian Population—A Case-Control Study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 10, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jugessur, A.; Wilcox, A.J.; Lie, R.T.; Murray, J.C.; Taylor, J.A.; Ulvik, A.; Drevon, C.A.; Vindenes, H.A.; Abyholm, F.E. Exploring the effects of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene variants C677T and A1298C on the risk of orofacial clefts in 261 Norwegian case-parent triads. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrier, C.; Perret, C.; Bahuau, M.; Zhu, H.; Nelva, A.; Herman, C.; Francannet, C.; Robert-Gnansia, E.; Finnell, R.H.; Cordier, S. Fetal and maternal MTHFR C677T genotype, maternal folate intake and the risk of nonsyndromic oral clefts. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2007, 143A, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, M.A.; Reynolds, K.; Zhou, C.J. Environmental mechanisms of orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Res. 2020, 112, 1660–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Verdín, S.; Solorzano-López, J.A.; Bologna-Molina, R.; Molina-Frechero, N.; Tremillo-Maldonado, O.; Toral-Rizo, V.H.; González-González, R. The Frequency of Risk Factors for Cleft Lip and Palate in Mexico: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14161753

López-Verdín S, Solorzano-López JA, Bologna-Molina R, Molina-Frechero N, Tremillo-Maldonado O, Toral-Rizo VH, González-González R. The Frequency of Risk Factors for Cleft Lip and Palate in Mexico: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(16):1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14161753

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Verdín, Sandra, Judith A. Solorzano-López, Ronell Bologna-Molina, Nelly Molina-Frechero, Omar Tremillo-Maldonado, Victor H. Toral-Rizo, and Rogelio González-González. 2024. "The Frequency of Risk Factors for Cleft Lip and Palate in Mexico: A Systematic Review" Diagnostics 14, no. 16: 1753. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14161753