Abstract

Additive Manufacturing (AM) techniques, such as Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA), are increasingly adopted in various high-demand sectors, including the aerospace, biomedical engineering, and automotive industries, due to their design flexibility and material adaptability. However, the tribological performance and surface integrity of parts manufactured by AM are the biggest functional deployment challenges, especially in wear susceptibility or load-carrying applications. The current review provides a comprehensive overview of the tribological challenges and surface engineering solutions inherent in FDM and SLA processes. The overview begins with a comparative overview of material systems, process mechanics, and failure modes, highlighting prevalent wear mechanisms, such as abrasion, adhesion, fatigue, and delamination. The effect of influential factors (layer thickness, raster direction, infill density, resin curing) on wear behavior and surface integrity is critically evaluated. Novel post-processing techniques, such as vapor smoothing, thermal annealing, laser polishing, and thin-film coating, are discussed for their potential to endow surface durability and reduce friction coefficients. Hybrid manufacturing potential, where subtractive operations (e.g., rolling, peening) are integrated with AM, is highlighted as a path to functionally graded, high-performance surfaces. Further, the review highlights the growing use of finite element modeling, digital twins, and machine learning algorithms for predictive control of tribological performance at AM parts. Through material-level innovations, process optimization, and surface treatment techniques integration, the article provides actionable guidelines for researchers and engineers aiming at performance improvement of FDM and SLA-manufactured parts. Future directions, such as smart tribological, sustainable materials, and AI-based process design, are highlighted to drive the transition of AM from prototyping to end-use applications in high-demand industries.

1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), or simply 3D-printing, is increasingly a revolutionary manufacturing process for the direct fabrication of complex geometries from digital models in a layer-by-layer deposition process. Among all the various AM technologies, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA) are the most widely used for the fabrication of polymeric and resin-based components because of their availability, material flexibility, and design freedom [1,2,3]. However, the extensive functionality of these technologies in functional industries such as aerospace, biomedical, automotive, and microfluidics has been accompanied by setbacks in some respects, particularly, surface finish and tribological performance.

Tribology, the physics of friction, wear, and lubrication, is critical to determining AM part performance under dynamic contact, motion, or load conditions. For traditionally produced parts, tribological response is deterministic and typically optimized by machining, surface treatment, or material choice. FDM and SLA parts, however, contain inherent anisotropy, stair-step surface roughness, and internal porosity that degrade wear resistance and frictional stability [4,5,6]. These issues arise from the inherent layer-by-layer manufacturing process, where interlayer discontinuities are stress raisers and sites for wear initiation. Optimizing the tribological performance of FDM and SLA parts is, therefore, critical to their migration from prototyping to end-use. FDM-printed components, which are usually printed in a thermoplastic such as PLA, ABS, or PETG, are noted for high surface roughness and anisotropy due to the layers [7,8]. The FDM process with extrusion causes rough layer lines and bad filament bonding, which are the primary reasons for high coefficients of friction (COF) and load wear [9]. In addition, process parameters such as infill density, nozzle diameter, raster orientation, and build direction also significantly contribute to tribological behavior and define the mechanical continuity and surface morphology of the component. On the other hand, SLA uses photopolymerization to print parts from liquid resins using intense light sources. SLA parts generally exhibit better surface finish (Ra ≈ 2–3 µm) and dimensional accuracy than FDM [10,11,12]. SLA parts are mechanically brittle, exhibit low impact strength, and are prone to micro-crack formation or delamination due to tribo-loading, particularly if there is poor post-curing. SLA resins are generally non-biodegradable and environmentally unsound too, a sustainability problem. Consequently, there is a significant requirement for surface engineering in AM, and specifically for FDM and SLA processes. This is a collection of mechanical, chemical, thermal, and coating-based techniques of changing or enhancing the surface characteristics of a part without altering its bulk [13,14]. In AM, some post-processing techniques, such as mechanical polishing, acetone vapor smoothing, UV/thermal curing, and thin-film coatings, have been found to work well in surface roughness reduction, tribo-improvement, and part life. For example, ABS part acetone vapor treatment has been found with up to 60% maximum surface roughness reduction, and metallic and ceramic coatings have been found to enhance hardness and wear resistance by more than 300% under certain conditions [15,16,17].

Recent publications show growing academic and industrial interest in tribology-focused research in AM, but serious gaps remain. Ng et al. [18] compared FDM head-to-head with SLA and reported that surface roughness (Ra ≈ 2 µm vs. 12–13 µm) and tensile strength (up to 70 MPa) are superior for SLA compared to FDM, but FDM outperforms SLA on cost, throughput, and sustainability, especially when using biodegradable materials like PLA. But in the present work, mostly simple metrics were evaluated and there was no test of long-term wear performance and friction processes in working conditions.

Regarding wear mechanisms, many research papers characterize abrasion, adhesion, fatigue, and delamination as being dominant in AM parts. PLA printed by FDM, for instance, exhibits wear due to plowing and micro-cutting due to the layer microstructure of the material, whereas SLA parts undergo brittle crack growth. A study by Miao et al. [4] on additive manufacturing of structural ceramics focuses on the fact that polymer-based AM parts do not have widespread applicability in high-load tribo-applications unless they are reinforced with functional fillers or surface coatings. FDM filaments reinforced with carbon fiber, graphene, and ceramic nanoparticle-based reinforcements have been explored to enhance mechanical and tribological properties. Uniform dispersion and interfacial bonding remain difficult to obtain. Post-processing techniques have been addressed by Boschetto and Bottini [19], who indicated that barrel finishing can reduce Ra in FDM parts by 40–60%, but typically at the expense of geometrical distortions. Thermal post-processing techniques, such as laser surface remelting (LSR), are being investigated more and more because they are able to selectively enhance surface microstructure without damaging the inner layers. Similarly, solvent-based methods, such as solvent vapor smoothing (e.g., ABS with acetone) and plasma etching, were also found to create sealed, hydrophobic surfaces with COF reduction of as much as 50%. These methods are material-specific and require parameter control for structural integrity. The use of surface coatings like metallic (e.g., Ni, Cr), ceramic (e.g., Al2O3, TiN), and polymeric (e.g., PTFE, Parylene) has been shown to confer substantial benefits in enhancing surface hardness, reducing friction, and extending wear life [20]. Spray-coating and dip-coating operations are widely used but suffer from limitations towards coating adhesion and thickness control. Emerging techniques such as plasma spraying and atomic layer deposition (ALD) are under investigation but are currently too costly for most AM applications. Another emerging area is hybrid manufacturing, where subtractive processes like CNC machining, grinding, or rolling are integrated with AM to produce functionally graded surfaces. For example, rolling of FDM parts post-printing has resulted in significant improvement in surface hardness and wear resistance because of the residual compressive stresses generated. Such techniques attempt to capitalize on the geometric versatility of AM and the surface quality of traditional processes. Despite these advances, few studies integrate process parameters, material selection, post-processing techniques, and tribological performance fully. Furthermore, model and simulation activities in this field are immature. Contact analysis and wear estimation finite element models (FEM) are rare, and their precision is limited by the complex anisotropic and heterogeneous nature of AM parts. Machine learning (ML) methods for the prediction of COF or wear rate from process parameters are still in the beginning stages, though initial results show promise for optimization of the process.

This review is necessitated by the growing demand for tribology-enhanced AM parts, particularly in high-value sectors such as aerospace, biomedical, and industrial tooling. The paradoxes and gaps in the current literature, especially in the fields of surface morphology-bridging, process engineering, and tribo-performance, necessitate an integrative, overarching review.

Unlike earlier reviews that often focus only on mechanical or thermal properties, this work offers a comprehensive and comparative analysis of tribological behavior in both FDM and SLA, integrating discussions on hybrid manufacturing strategies, advanced surface engineering, AI-based predictive tools, and sustainability trends. This unified perspective highlights how these approaches collectively address the unique wear challenges of polymer-based AM parts, providing actionable insights for design and manufacturing engineers. Despite these advances, current research often remains fragmented, focusing separately on materials, process parameters, post-processing, or wear mechanisms, without a fully integrated framework linking process, structure, and tribological performance. Predictive modeling using finite element methods (FEM) and emerging machine learning (ML) tools also remains limited, primarily due to the anisotropic and heterogeneous nature of AM parts and insufficient datasets for robust training and validation.

Recognizing these gaps and the rising demand for tribology-optimized AM parts in high-value sectors, this review aims to provide a comprehensive, comparative, and forward-looking synthesis of the field. Specifically, the distinctive contributions of this review are as follows:

- A comparative tribological analysis of both FDM and SLA processes within a unified discussion.

- Integration of material selection, process parameters, and surface engineering strategies to enhance wear resistance and surface durability.

- Examination of hybrid manufacturing techniques that merge additive and subtractive methods for functional surfaces.

- A critical overview of FEM and ML-based predictive frameworks for wear and friction performance in AM parts.

- Discussion of future directions, including smart tribological materials, sustainability considerations, and AI-driven process optimization.

Through this integrative approach, the present review not only highlights existing research but also critically analyzes gaps, practical trade-offs, and emerging solutions to enhance the tribological performance of FDM and SLA parts. The following sections sequentially explore the fundamentals of these technologies, comparative analysis of their tribological behavior, surface engineering strategies, predictive modeling tools, and the outlook for future industrial applications.

Literature Search Methodology

To ensure a comprehensive and balanced review, an extensive literature search was performed across major scientific databases, including Scopus and Web of Science. The search focused primarily on publications from 2016 to 2025, while also including selected foundational studies from earlier years to provide historical context.

Key search terms were combined using Boolean operators and included: “FDM tribology”, “SLA wear mechanisms”, “surface engineering in additive manufacturing”, “hybrid manufacturing for polymers”, and “additive manufacturing post-processing”.

The inclusion criteria prioritized:

- Peer-reviewed journal articles, authoritative review papers, and high-impact conference proceedings.

- Studies offering experimental or simulation-based insights into friction, wear, lubrication, and surface modification in FDM and SLA processes.

The selection process consisted of initial title and abstract screening, followed by full-text review for technical depth, novelty, and relevance. Additional references were identified through backward and forward citation tracking. This methodological approach aimed to build a rigorous and current foundation for the comparative analysis presented in this review.

2. Fundamentals of FDM and SLA Additive Manufacturing

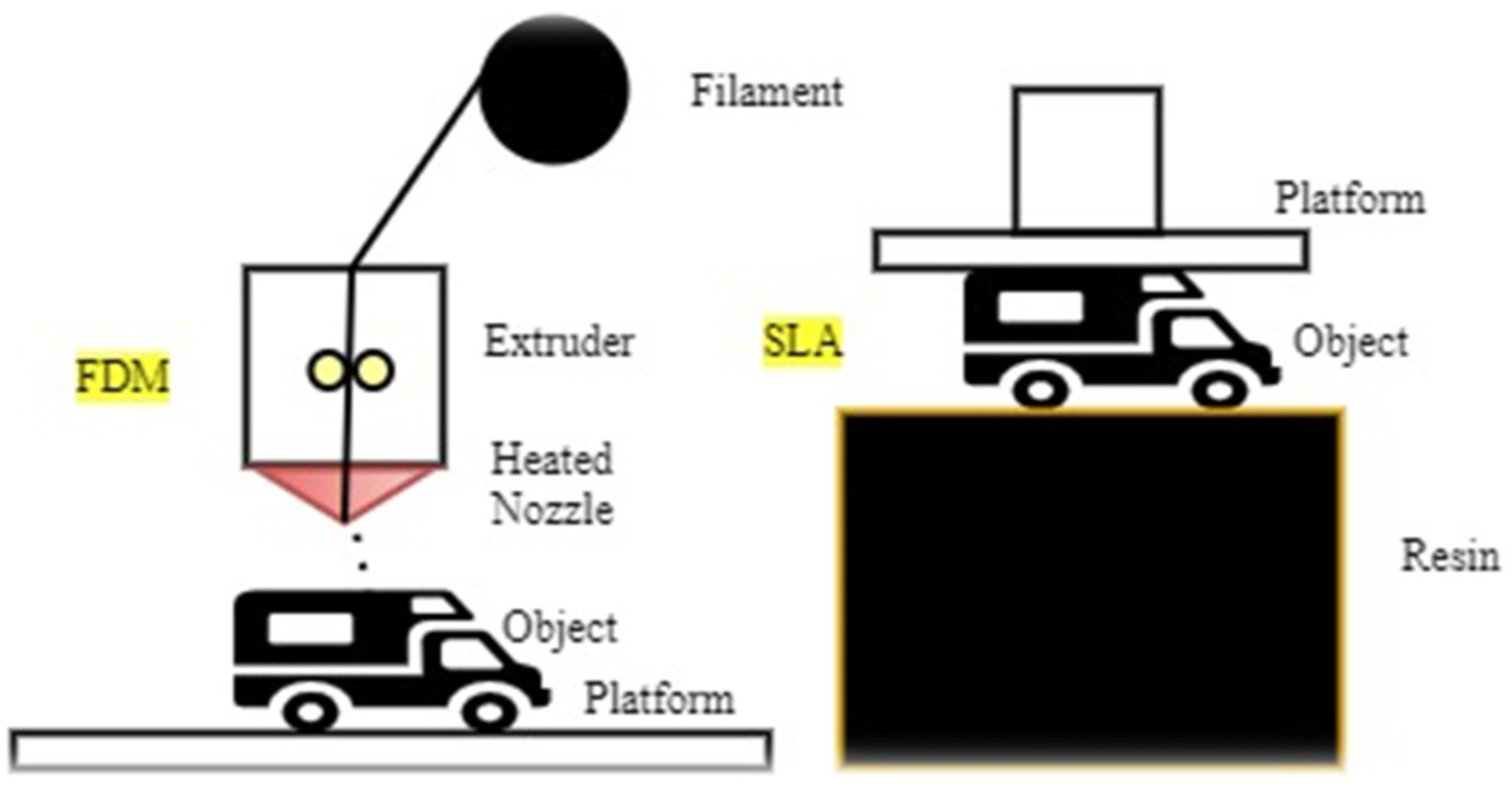

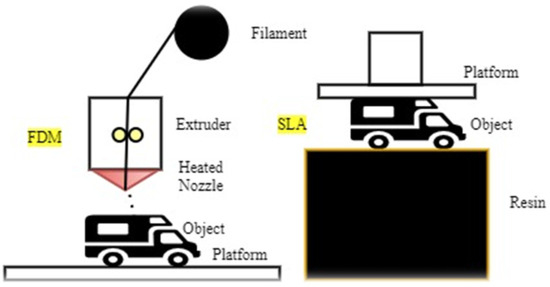

The most widely used additive manufacturing (AM) technologies for polymeric part fabrication are Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA), both having distinct mechanisms, materials, and process limitations that strongly influence surface properties and tribological performance [21,22,23]. FDM extrudes thermoplastic filaments (e.g., PLA, ABS, PETG, and their composite reinforcements) out of a heated nozzle, depositing material in layer form along a G-code-defined trajectory. The build plate descends incrementally after every layer to allow successive solidification of thermoplastic strands, which bond primarily through thermal bonding [4]. Extrusion temperature, cooling rate, raster orientation, nozzle diameter, build direction, and infill density strongly influence layer adhesion success and resulting mechanical integrity. These parameters regulate the degree of interlayer diffusion, porosity, and residual stress, influencing surface finish, dimensional accuracy, and wear resistance. SLA builds parts by photopolymerizing photosensitive resins with a laser or digital light projector. Bottom-up systems use a UV light source to cast cross-sectional patterns onto a resin bath, curing one layer at a time before a platform lift to allow new resin to flow underneath. SLA’s photopolymerization basis provides higher resolution and surface smoothness (typically Ra ~2–3 μm), but mechanical brittleness and poorer load-bearing behavior are still limiting factors due to incomplete cross-linking or oxygen inhibition during curing. Process sensitivity to light dosage, exposure time, layer thickness, and resin viscosity directly influences microstructural homogeneity and surface durability [24,25,26]. SLA materials are based on acrylate and epoxy-based resins, with increasing interest in toughened and bioresorbable formulations for biomedical use. On the other hand, FDM makes the use of recyclable thermoplastics and biodegradable filaments, such as PLA-carbon fiber or PETG-carbon fiber blends, more sustainable and structurally compatible. Most importantly, the microstructural anisotropy inherent to FDM, manifested in stair-stepped side walls and internal porosity, significantly affects the tribology of dynamic-loading surfaces, resulting in premature delamination and fatigue wear [27,28]. SLA, although less prone to delamination due to monolithic curing, suffers from brittle fracture under impact and tribo-fatigue due to low elongation at break. Process defects in both systems require post-processing corrections, but the nature and extent differ. FDM parts often undergo mechanical sanding, vapor smoothing (e.g., acetone for ABS), or laser remelting to repress roughness and seal layer gaps. SLA parts compensate more to post-cure thermally or by UV, enhancing cross-link density, followed by mild polishing to prevent loss of fine geometries. SLA materials can also be engineered with nanoparticles or elastomeric inclusions to modulate modulus and fracture toughness, whereas FDM capitalizes on composite filaments with carbon fibers, graphene, or ceramic fillers to enhance the strength-to-weight ratio and repress surface deterioration under contact wear. Advanced versions of both processes now support hybrid material systems multi-material FDM heads or SLA resin switching to print functionally graded materials with spatially variable properties [29,30,31]. These innovations overcome the monolithic print limitation by enabling optimization of tribo-surfaces within one structure. However, predictability of the processes remains an issue: FDM’s mechanical properties are highly direction-sensitive, while SLA parts can be beset by shrinkage, curling, or residual stress gradients that affect the final geometry and surface reliability. Simulation software and in situ monitoring hardware are beginning to bridge this gap, using thermal imagery, laser scanners, or machine learning algorithms to forecast surface quality outputs from live process inputs. Researchers are also looking at the incorporation of subtractive finishing tools (e.g., micro-milling or abrasive blasting) into AM processes to fabricate surfaces with complex geometry as well as engineered frictional behavior [32,33]. Materials-wise, FDM is more flexible, with thermoplastics having glass transition temperatures of 50–150 °C, while SLA is restricted to brittle thermoset resins with limited thermal stability [34,35,36]. Nonetheless, SLA is more appropriate for microfluidics and dental prosthetics, while accuracy and surface finish are more important than mechanical toughness. FDM is more appropriate, in turn, for structural components such as brackets, gears, or biomedical scaffolds, where toughness, reparability, and surface engineering via coating are feasible. Of special interest, inclusion of nanoscale additives, such as CNTs, Al2O3, or TiN, into FDM filaments or SLA resins introduces new complexity, where interfacial bonding, particle agglomeration, and variability in thermal conductivity influence surface performance under tribological loading. Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental working principles of FDM and SLA processes, highlighting the material feed mechanisms, platform orientation, and object formation strategies that govern the layer-by-layer fabrication of parts.

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison between Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA) additive manufacturing techniques. FDM operates by extruding thermoplastic filaments through a heated nozzle onto a build platform layer-by-layer, whereas SLA utilizes a light source to cure liquid resin, gradually forming the object as the platform lifts from the resin bath.

Tribo-enhancement through selection of materials is thus intrinsically connected with processability. SLA’s resin chemistry must be UV-transparent and low viscosity, while FDM filaments must maintain flowability and avoid nozzle clogging [37,38]. These constraints necessitate materials innovation in AM. Hybrid polymers, such as TPU-carbon fiber or bio-based PETG with nanoclay infusion, for example, are being engineered to bridge the gap between flexibility and wear resistance, with improved layer fusion and reduced surface degradation. Ultimately, an understanding of the interaction between process physics, material response, and surface formation mechanisms is the key to optimizing AM parts for contact-rich environments. Emerging trends include digital twin models to predict roughness and wear from input parameters, and AI-based slicers modulating layer height or extrusion speed adaptively with respect to part geometry and anticipated contact zones. In summary, the physics of FDM and SLA are different in nature—thermal extrusion of thermoplastics versus photopolymerization of resins—with corresponding differences in surface morphology challenges, tribological durability, and material compatibility. Control of their process parameters along with intelligent material selection and surface modification processes will be the hallmark of the next generation of performance-based additive manufacturing [39,40,41]. Table 1 reviews recent works on the tribological behavior of FDM and SLA 3D-printed materials with a focus on polymers as well as their composites for various engineering applications.

Table 1.

Comprehensive summary of recent studies on tribological behavior of FDM and SLA 3D-printed polymers and composites, highlighting research domains, key challenges, objectives, methodologies, major findings, and remarks for future research.

In recent years, the sustainability of additive manufacturing (AM) has become a growing concern due to rising environmental regulations and the need for resource-efficient production. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA) differ significantly in their ecological footprint. FDM typically employs thermoplastic filaments, such as PLA, ABS, PETG, or composites, many of which are recyclable or bio-based. In contrast, SLA relies on photopolymer resins, which are chemically complex and harder to recycle. Moreover, SLA post-processing involves isopropyl alcohol washing and UV curing, generating chemical waste. FDM, on the other hand, often requires only mechanical trimming and minimal thermal finishing. Energy-wise, SLA printers consume more electricity due to the high intensity of UV sources and constant resin agitation, while FDM machines are relatively energy efficient for small- to medium-scale parts. Table 2 summarizes key sustainability indicators for both processes, providing a clearer picture of their environmental trade-offs.

Table 2.

Sustainability Comparison between FDM and SLA Processes [3,4,42,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59].

In summary, FDM and SLA represent fundamentally different approaches to additive manufacturing, each with distinct advantages and limitations affecting tribological performance. FDM offers design freedom and material recyclability but suffers from anisotropic properties and rougher surfaces, whereas SLA delivers smoother finishes and higher dimensional accuracy at the expense of brittleness and sustainability challenges. Understanding these differences in process physics, material selection, and resulting surface morphology is critical for optimizing part durability and wear resistance in functional applications.

3. Comparative Tribological Performance of FDM and SLA Parts

The tribological performance of additively manufactured (AM) components produced by Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA) is dictated by a complex interplay of process parameters, material composition, reinforcement strategies, and layer-induced microstructures [60]. Despite sharing the layer-by-layer deposition principle, the two technologies exhibit fundamentally different wear behaviors, driven by their contrasting fabrication mechanisms and material chemistries. In FDM, fused thermoplastic filaments such as PLA, PETG, or ABS are extruded along predefined paths, creating layered structures characterized by surface roughness and anisotropic mechanical properties. Among observed wear mechanisms, abrasive wear dominates in these thermoplastics, where hard counterface asperities plough or micro-cut the relatively soft polymer matrix, leading to progressive material removal [60]. Adhesive wear emerges under conditions where thermal softening or molecular affinity promotes local welding and material transfer, while fatigue wear is linked to cyclic stresses concentrating at interlayer voids or weak bonding sites, initiating micro-cracks that propagate over time.

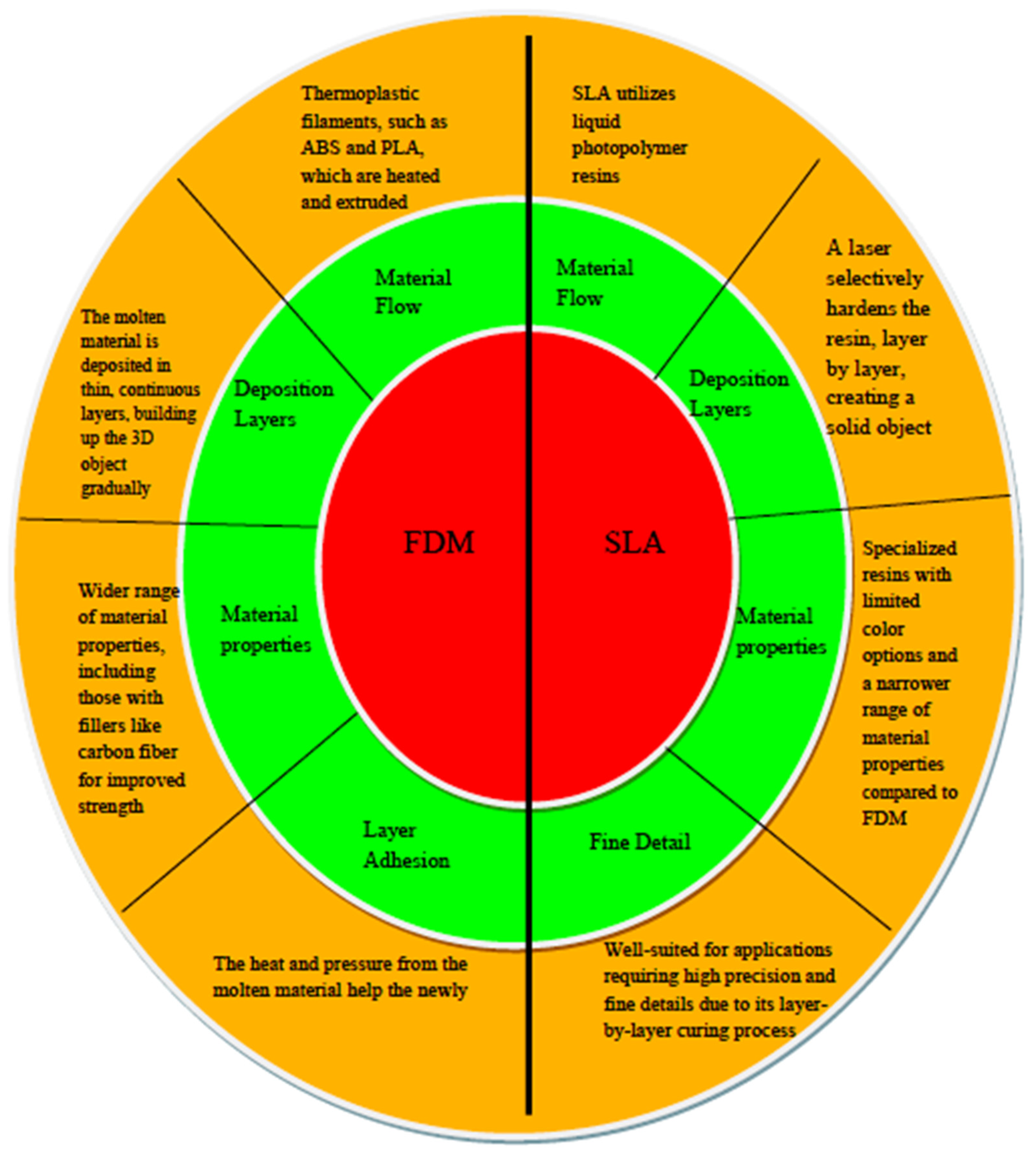

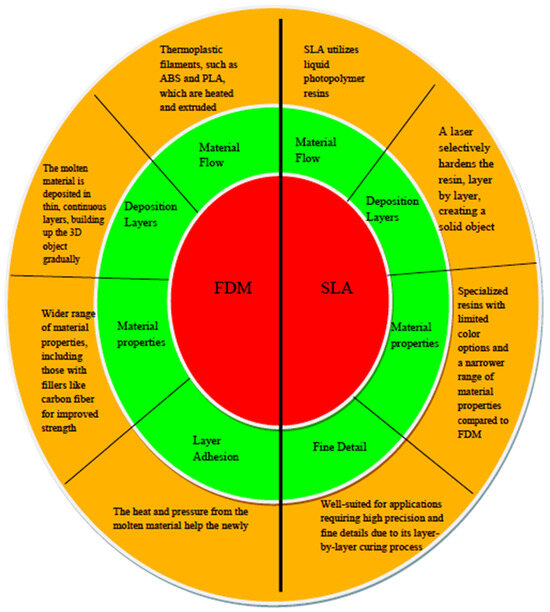

Process parameters critically affect these wear responses. High infill densities (90–100%) reduce porosity, improve load-bearing capacity, and enhance wear resistance. Raster angle and build orientation guide polymer chain alignment: printing at 0° relative to the sliding direction distributes stress uniformly, lowering wear rates, whereas ±45° or 90° orientations increase anisotropy and delamination risk. Nozzle diameter also matters: larger nozzles extrude thicker beads, reducing voids but compromising surface resolution, while smaller nozzles achieve finer detail but may introduce inter-bead gaps susceptible to cracking [61,62,63,64]. Layer thickness shows a similar trade-off; thinner layers (0.1–0.2 mm) yield smoother surfaces but can increase thermal gradients, whereas thicker layers improve bulk strength but elevate roughness. Material selection adds further complexity. PLA, while stiff and biodegradable, lacks toughness, making it prone to adhesive wear at higher contact pressures. Studies show that adding ~5 wt.% silicon fillers to PLA reduces wear rate by ~66% by promoting tribo-film formation, which smoothens surfaces and protects against abrasive action. Carbon fibers and graphene nanoparticles further decrease friction by forming lubricating transfer films and stiffening the matrix. PETG offers better impact resistance and fatigue life than PLA but remains vulnerable to ploughing unless reinforced. ABS provides superior ductility and toughness, enhancing adhesive wear resistance, but its amorphous structure can soften under heat, destabilizing transfer films [65,66]. Figure 2 contrasts the filament-based FDM deposition, with inherent interlayer defects, against SLA’s photopolymer curing process, which produces smoother and more isotropic surfaces. The use of nano-fillers like silicon, ZnO, and SAN in FDM has been shown to significantly enhance thermal stability and wear resistance [67,68,69,70]. Neat PLA, with a COF around 0.24, sees reductions to ~0.11–0.13 with these reinforcements attributed to stable tribo-films that minimize adhesive bonding and reduce abrasive groove formation, as confirmed by SEM analysis. Ceramic fillers also induce superlubricity under humid conditions by reacting with water to form protective transfer layers, further lowering adhesion and wear [71,72]. Yet, uniform filler distribution remains critical; loadings beyond ~5–7 wt.% can cause extrusion defects like necking or bulging, leading to localized wear concentration. Optimal filler content typically balances mechanical benefits and printability without degrading dimensional accuracy.

Figure 2.

Comparison of material flow and layer deposition characteristics in FDM and SLA additive manufacturing processes.

Emerging approaches, such as nano-engineered fillers like CNTs, MoS2, and Si3N4, alongside machine learning–assisted parameter tuning, have demonstrated further potential in optimizing wear performance [73,74,75,76]. Print layer thickness, raster angle, and cooling rate can all be algorithmically adjusted to minimize wear rates and COF. Table 3 in this study collates experimental evidence, highlighting these process–property relationships across various thermoplastic systems and industrial applications.

Table 3.

Overview of recent research on tribological performance in advanced additive manufacturing (AM) materials and composites, highlighting innovations in SLA, FDM, DIW, and DLP processes.

By contrast, SLA employs photopolymerization of UV-curable resins, producing parts with inherently smoother surfaces (Ra < 2 µm) and higher dimensional precision [96]. This fine finish greatly reduces initial abrasive wear under mild contact. However, SLA parts face different challenges: brittleness, curing sensitivity, and limited elongation at break. Under tribological loading, SLA resins predominantly exhibit brittle fracture mechanisms: crack nucleation, propagation, and delamination rather than plastic flow. These failures are often initiated at stress concentrators like sharp corners, support removal points, or internal voids left by incomplete curing. Post-curing through additional UV or thermal exposure is therefore essential to enhance cross-link density, increase surface hardness, and stabilize wear resistance. Experimental studies demonstrate that cracks in SLA parts may shift from tensile-dominated (mode I) to shear-dominated (mode II) propagation depending on loading orientation [97,98,99,100]. Finite element modeling corroborates this, showing peak von Mises stresses localizing near layer interfaces and crack tips, especially where slicing introduces anisotropic weak zones. Moreover, SLA’s brittle nature under dynamic loads often leads to catastrophic fracture rather than the gradual wear seen in FDM thermoplastics.

To facilitate practical decision-making, Table 4 presents a comparative evaluation of FDM and SLA strategies for tribological enhancement, including their respective advantages, limitations, cost implications, and sustainability potential. Techniques such as vapor smoothing and thin-film coatings have shown notable improvements in surface finish and wear resistance but vary significantly in cost-effectiveness and environmental footprint [19,20,71]. Meanwhile, hybrid methods like post-print rolling and emerging machine learning (ML)-driven optimization frameworks offer promising paths for performance tuning with higher sustainability and process adaptability [4,33,73]. This table serves as a design-oriented synthesis to guide researchers and engineers in selecting strategies aligned with specific performance and sustainability goals.

Table 4.

Trade-offs in FDM and SLA strategies for tribological optimization [4,19,20,33,71,73].

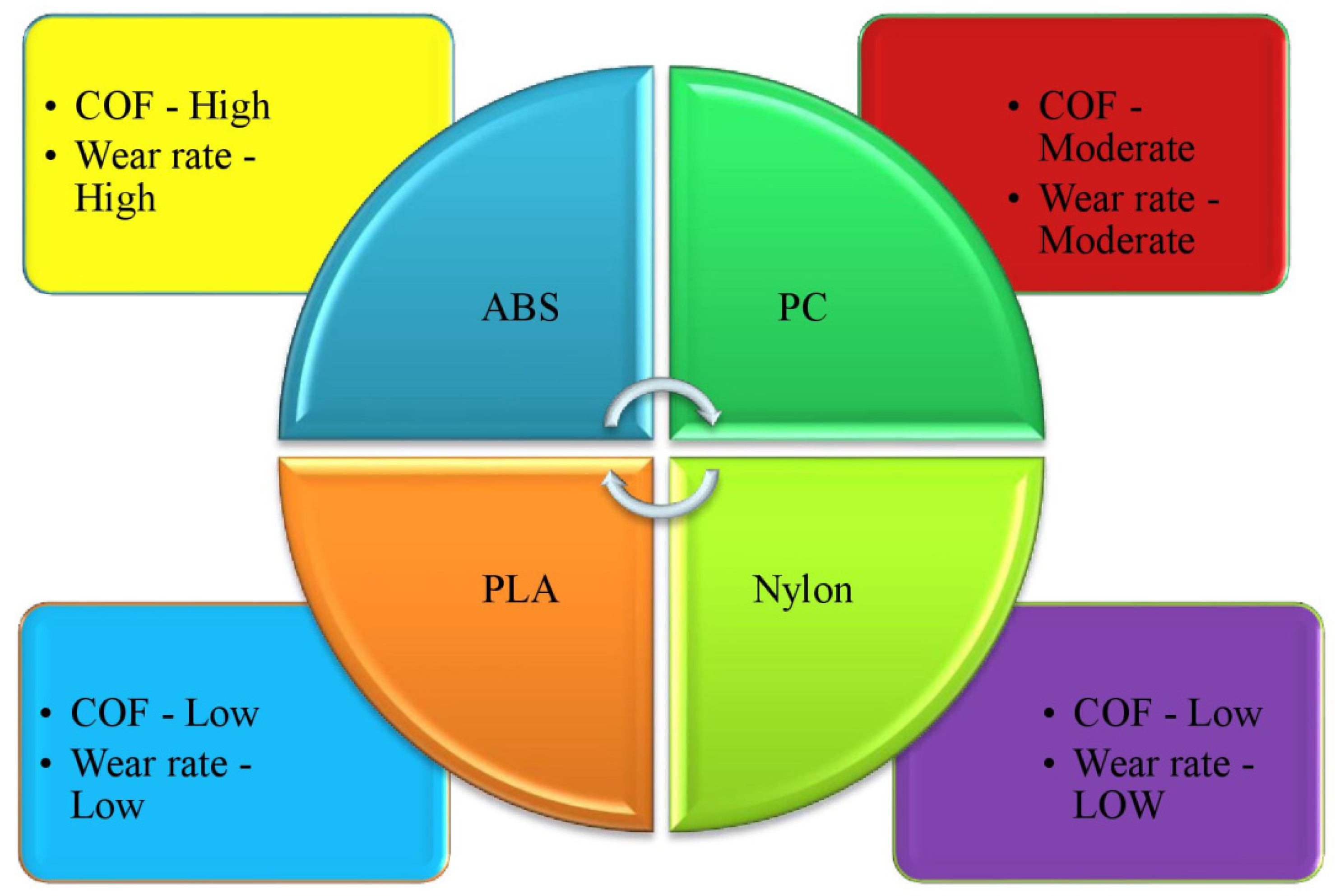

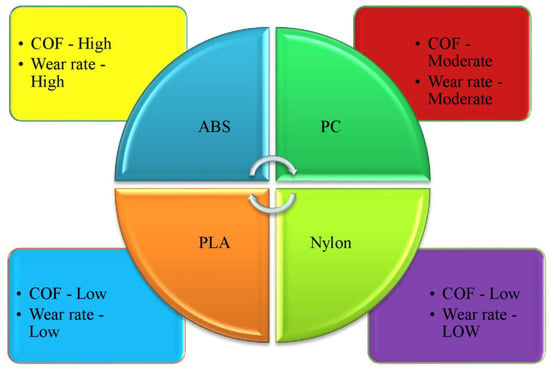

Nevertheless, SLA excels in applications prioritizing high surface accuracy and complex geometries, such as dental prosthetics, microfluidic devices, and MEMS, where tight tolerances outweigh impact strength concerns. Figure 3 illustrates comparative COF and wear rates, highlighting that while filler reinforcement is common in FDM, it remains underexplored in SLA though it offers promising pathways for enhancement. In dentistry, SLA-fabricated crowns and splints provide superior surface conformity and patient comfort but face wear limitations under mastication. Post-processing treatments such as plasma surface activation, nano-particle reinforcement with silica or alumina, and thin-film coatings like PTFE or parylene help reduce friction and block crack initiation [101,102]. SLA’s compatibility with acrylate and PEG-diacrylate resins also makes it valuable in biomedical scaffolds and surgical guides, where smooth lumens minimize tissue shear and inflammation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of coefficient of friction (COF) and wear rate for common FDM-printed polymers. Materials such as PLA, PETG, and ABS exhibit varying tribological behavior, with reinforced variants (e.g., PLA–SiC, PETG–CF) demonstrating significantly improved wear resistance and reduced COF, highlighting the impact of filler materials on performance.

Mixed-mode fracture studies suggest that, in well-cured SLA parts, resin composition and build orientation have limited impact on elastic modulus and toughness, indicating relatively isotropic bulk properties [103,104,105]. Digital image correlation (DIC) techniques have revealed strain localization before visible cracks appear, offering predictive cues for maintenance or design adjustment. Unlike thermoplastics that gradually wear via smearing, SLA parts tend to flake, exposing fresh resin surfaces that dynamically shift COF.

To mitigate brittleness, researchers are developing toughened SLA resins using urethane dimethacrylate blends or ceramic fillers, which trade minimal resolution loss for higher fracture toughness. Build orientation also influences wear: vertical prints can lower edge chipping by distributing load along layers, while horizontal prints improve layer cohesion but risk concentrated wear at base surfaces. SLA’s precise surface finish remains an advantage in static friction-critical or dimension-sensitive applications, though cyclic loading still necessitates hybrid or multi-material approaches. In biotribology, SLA enables the design of patient-specific implants with controlled surface texturing, directly influencing protein adsorption, lubrication film formation, and cellular migration—key factors for integration into biological systems. Table 5 summarizes recent innovations in material formulations, tribological performance, and engineering implications specific to SLA.

Table 5.

Comprehensive summary of multidisciplinary research across biomedical implants, surface engineering, additive manufacturing, sustainable energy, and smart materials.

In summary, while FDM offers broader material options, ductility, and reinforcement flexibility, it suffers from anisotropy and surface roughness affecting wear behavior. SLA delivers unmatched surface quality and accuracy but struggles with brittle failure modes and limited reinforcement strategies. Both processes demonstrate strong parameter sensitivity where design choices like layer thickness, infill, raster angle, and curing protocols can markedly influence COF and wear life. Emerging strategies from nano-reinforcement and machine learning-based process control in FDM to resin toughening and hybridization in SLA point toward future solutions. Together, they illustrate that achieving reliable tribological performance in AM parts requires integrating material science, process optimization, and post-processing to match specific functional demands.

4. Surface Engineering, Hybrid Strategies, and Predictive Tools

Achieving reliable tribological performance in FDM and SLA parts demands more than optimized printing parameters; it requires systematic surface engineering, hybrid manufacturing, and increasingly, predictive digital tools to address the intrinsic challenges of layer-by-layer fabrication, such as the staircase effect, interlayer voids, and anisotropic bonding [126,127,128].

4.1. Mechanical, Thermal, and Chemical Surface Treatments

Surface treatment and post-processing play pivotal roles in overcoming inherent AM deficiencies. Mechanical techniques like abrasive flow machining (AFM), vibratory finishing, shot peening, and CNC milling reduce surface roughness and improve dimensional accuracy. AFM is particularly effective for polishing complex internal geometries, achieving Ra reductions over 60% by selectively smoothing high points while preserving functional features [126,129,130]. Thermal methods, such as laser polishing and thermal annealing, locally reflow surface asperities. Laser-assisted processes—including continuous wave, pulsed, and beam wobbling techniques—can lower surface roughness from ~7.5 µm to sub-micron levels (~0.2 µm) and increase subsurface hardness through rapid thermal cycling [131]. This enhances resistance to wear initiation and fatigue cracking. Chemical treatments like acetone vapor smoothing, solvent dipping, and plasma etching mobilize surface polymer chains, welding layer interfaces and lowering roughness by up to 95%, without mechanical abrasion. These processes are especially effective for materials like ABS and PLA. For metal AM parts, electrochemical polishing selectively dissolves surface peaks, improving corrosion resistance and removing trapped powders [132,133,134].

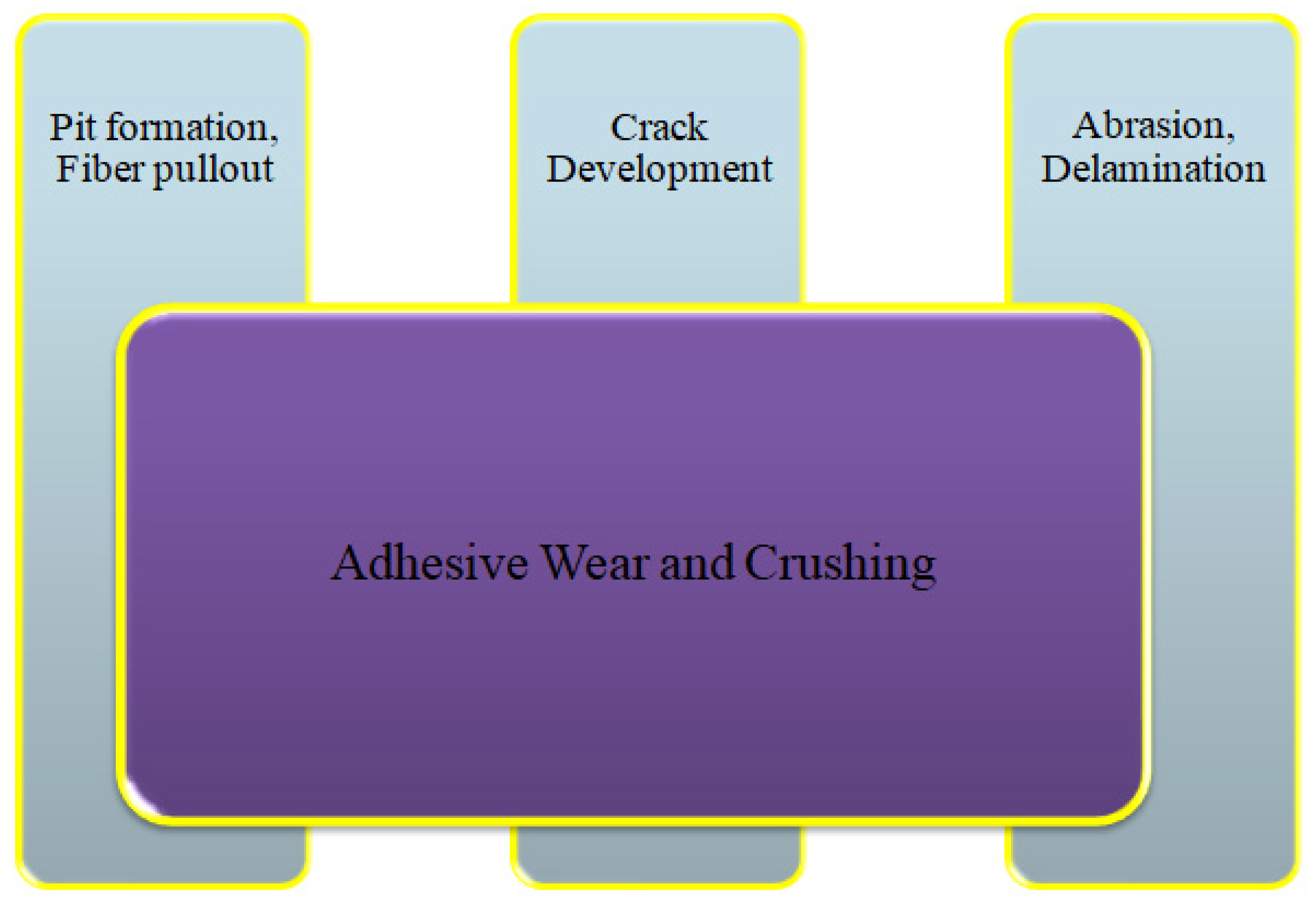

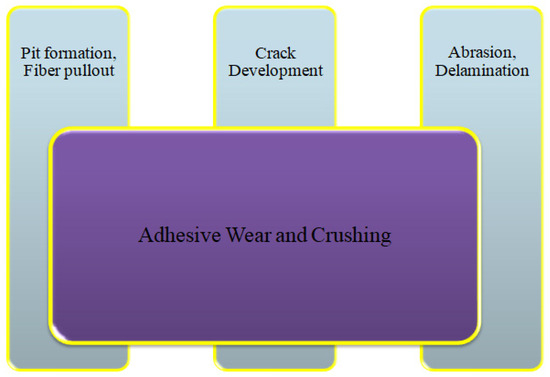

Complementing these, functional coatings tailor surface properties for specific applications. Metallic coatings (Ni, Cr, Cu) increase wear resistance and electrical conductivity, polymeric coatings (PTFE, parylene) reduce friction and add biocompatibility, and ceramic coatings (Al2O3, SiC, ZrO2) provide exceptional hardness and thermal stability [135]. Hybrid coatings, embedding particles into metallic or polymer matrices, produce multifunctional tribological surfaces. Together, these approaches can reduce Ra from ~8–15 µm to <1 µm and improve wear resistance by up to an order of magnitude [136]. Figure 4 illustrates how wear in composites evolves from mild adhesive wear to severe fiber pullout and delamination, underscoring the need for robust surface engineering.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical representation of dominant wear mechanisms observed in 3D-printed composite materials. From core to outer layers, the mechanisms include adhesive wear and crushing, crack development, pit formation with fiber pullout, and surface-level abrasion and delamination. This layered view reflects the progressive nature of tribological damage under increasing load and contact severity.

4.2. Integrated and Hybrid Post-Processing

Beyond smoothing, post-processing also improves bulk properties: acetone-smoothed ABS parts show tensile strength gains up to 20%, and laser remelting or polishing enhances flexural toughness and fatigue life by sealing micro-cracks and introducing compressive residual stresses [137,138]. Combining thermal and chemical treatments—e.g., laser smoothing followed by chemical etching—improves surface uniformity by filling voids and removing oxidation or debris. Process design must consider geometry: chemical dipping can cause dimensional distortion, particularly in thin-walled components, mitigated by oversizing CAD models or selective masking. Uniformity over complex surfaces requires advanced setups like rotary vapor chambers, multi-axis laser heads, or custom electrochemical fixtures. Emerging hybrid additive–subtractive systems integrate milling or polishing heads directly on AM platforms, enabling real-time, in situ finishing. This reduces handling errors, shortens production cycles, and maintains tight dimensional tolerances. Machine learning models predict surface outcomes based on input parameters including layer thickness, build orientation, and cooling rate, helping engineers optimize post-processing without costly trial-and-error.

These improvements extend AM’s reach: smoother surfaces enhance osseointegration in implants, lower bacterial adhesion in medical devices, and deliver the gloss and abrasion resistance needed for consumer electronics and automotive parts [139,140,141]. However, trade-offs remain: chemical treatments may raise sustainability concerns if solvents are not recycled; mechanical finishing can be labor-intensive or geometry-limited; and thermal methods risk residual stresses or microstructural changes if not carefully controlled. Table 6 summarizes key challenges, methods, and reported outcomes across sectors like aerospace, biomedical, and energy, reflecting how integrated surface engineering enhances AM part reliability.

Table 6.

Extensive compilation of multidisciplinary research focused on tribological behavior, surface engineering techniques, additive manufacturing innovations, biomedical materials, and modeling strategies.

4.3. Hybrid Manufacturing Strategies

Hybrid manufacturing combines AM with subtractive, mechanical, and surface treatments to address persistent limitations: anisotropic bonding, poor layer adhesion, and low wear resistance [162,163,164]. For example, CNC milling or micro-machining refines external surfaces while preserving complex internal features; SLA parts benefit from polishing of mating surfaces or microfluidic channels affected by resin shrinkage.

Surface mechanical treatments like Ultrasonic Surface Rolling Process (USRP), laser shock peening, and shot peening introduce beneficial residual compressive stresses, refine grain sizes, and increase hardness, reducing wear volume by over 50% in steels like H13 [165,166]. These non-thermal methods prevent distortion and improve fatigue life, critical for SLA parts prone to brittle fracture. Hybrid processes also enable functionally graded materials (FGMs): dual-nozzle FDM systems print stiff, wear-resistant shells over softer, shock-absorbing cores; SLA systems switch resins layer-by-layer to build bio-inspired laminates or hydrogels with tailored frictional and swelling properties. Laser cladding and directed energy deposition can deposit hard particles or metallic layers, improving thermal conductivity and sliding wear resistance [167,168,169]. Microstructural studies reveal how these treatments introduce ~−933 MPa compressive stresses, achieve sub-2 µm grain sizes, and raise dislocation densities (~5 × 1015 m−2), boosting frictional stability and lowering wear rates in dry or semi-lubricated contact. AI-driven adaptive control further refines additive–subtractive cycles in real time, preventing over-processing and improving precision [170,171,172,173,174]. Platforms integrating SLA with ultrasonically assisted milling or layer-by-layer peening demonstrate closed-loop, hybrid AM [175,176,177]. Hybrid strategies thus transform AM from prototyping into production, delivering robust, wear-optimized parts suitable for aerospace brackets, biomedical devices, and tribo-critical machinery.

4.4. Predictive Tools and Future Trends

Despite progress, achieving tribologically stable FDM and SLA parts remains challenging due to anisotropic bonding, layer delamination, and the brittleness of cured resins [78,178,179]. Standard slicer software focuses on geometric accuracy rather than mechanical and tribological performance, neglecting contact stresses and wear paths, limiting reliability in high-performance applications like aerospace and biomedical implants [180,181,182,183]. Hybrid manufacturing helps bridge this gap by adding subtractive finishing, peening, and coatings [184,185,186]. Multi-material designs—core–shell geometries in FDM, resin switching in SLA—create functionally graded parts balancing hardness and ductility. Coatings, like ceramics or metals, add wear resistance, lubricity, and corrosion protection [187,188,189]. On the digital front, AI and ML promise significant gains: adaptive slicing could adjust infill patterns, raster orientation, and material allocation based on simulated load paths, while in situ sensors measure thermal profiles, roughness, and strain to enable real-time corrections [190,191]. Future trends include printable high-entropy polymers, self-healing composites, and bio-inspired textures, alongside solvent-free, recyclable coatings for sustainable production.

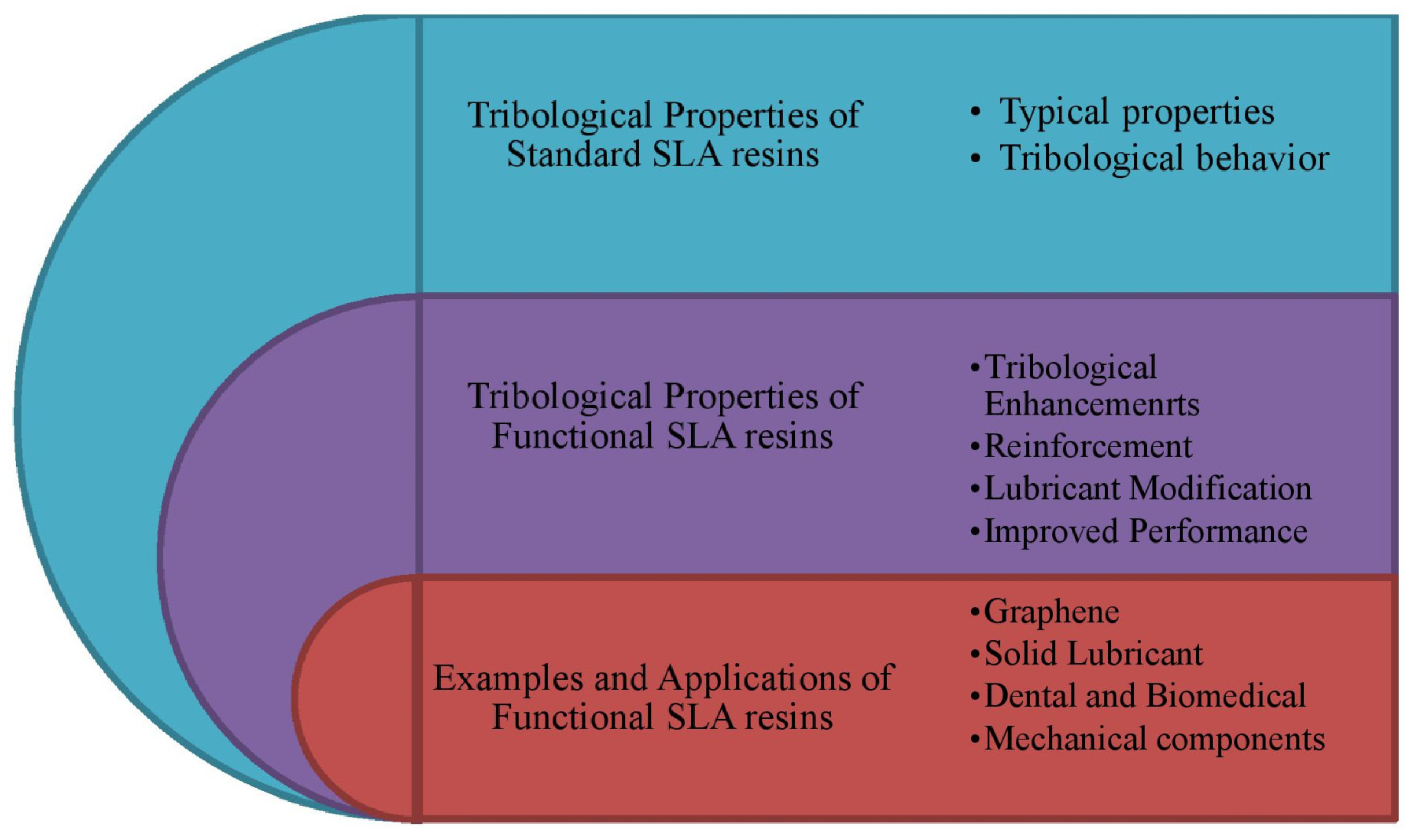

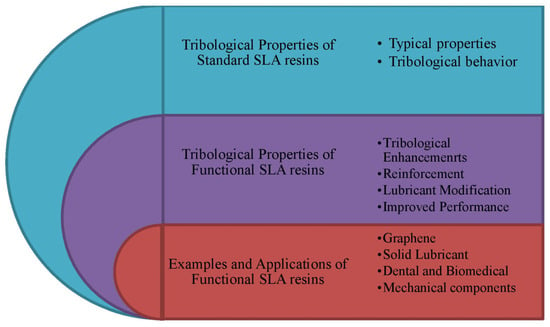

Figure 5 illustrates the hierarchical classification of tribological properties and applications of SLA (stereolithography) resins. It begins with standard SLA resins, focusing on their typical properties and tribological behavior. The next layer details functional SLA resins, which achieve enhanced tribological performance through reinforcement and lubricant modification. Finally, it presents specific examples and applications of these functional resins, such as graphene-infused materials, solid lubricants, and uses in dental, biomedical, and mechanical components.

Figure 5.

Tribological properties of standard versus functional SLA resins. The comparison highlights differences in coefficient of friction, wear rate, and surface degradation under identical test conditions. Functional resins, often engineered with fillers or surface modifiers, exhibit enhanced wear resistance and lower friction, making them suitable for precision and load-bearing applications.

Ultimately, bridging design freedom and durability requires cross-disciplinary integration of material science, process engineering, and AI, enabling AM parts to meet demanding tribological requirements in biomedical, aerospace, and energy applications. Table 7 presents a categorized summary of common surface engineering strategies applied to FDM and SLA parts with emphasis on their tribological performance enhancement. This structure allows for clearer understanding of which strategy is most suitable based on material type, desired surface effect, and processing constraints.

Table 7.

Categorization and comparison of surface engineering strategies for FDM and SLA in tribological applications [4,8,9,41,42,43,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,76,77,78,89,94,95,96,102,117,127,192,193].

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This review critically examined the tribological challenges and advancements in FDM and SLA additive manufacturing, showing how materials innovation, hybrid processes, and intelligent design are reshaping performance limits. While FDM remains constrained by anisotropic bonding and surface roughness, SLA faces brittleness and curing sensitivity that can cause crack initiation and unpredictable fatigue failures. Recent progress in nano-reinforcements and functional fillers has demonstrated significant reductions in friction and wear, complemented by mechanical, thermal, and chemical surface engineering strategies that lower roughness to sub-micron levels and improve fatigue life. Hybrid manufacturing methods combining additive deposition with peening, milling, and laser cladding emerge as a powerful route to introduce compressive stresses, refine grain structure, and produce functionally graded surfaces. Simultaneously, AI and machine learning tools enable predictive process control, mapping printing parameters to tribological performance and allowing real-time adaptive optimization. Sustainability trends, including bio-based filaments and solvent-free post-processing, align additive manufacturing with global environmental goals while retaining durability. Looking ahead, the integration of digital twin frameworks and self-healing polymers promises adaptive, self-optimizing AM parts for critical applications.

Key highlights of this review include:

- Detailed analysis of dominant wear modes linked to process parameters and anisotropy,

- Demonstration of how nano-fillers form protective tribo-films,

- Evaluation of surface treatments that reduce roughness and enhance mechanical integrity,

- Presentation of hybrid manufacturing as a route to wear-resistant, graded surfaces,

- Review of AI and ML for predictive optimization,

- Discussion of sustainable materials and greener processes, and

- Exploration of digital twins and smart polymers as emerging adaptive solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and K.V.S.; methodology, R.S.; software, M.A.R.; validation, R.S., R.N. and K.V.S.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S.; resources, M.A.R. and K.V.S.; data curation, R.R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., R.R.L. and R.N.; writing—review and editing, R.S., M.A.R. and K.V.S.; visualization, K.V.S.; supervision, R.S. and K.V.S.; project administration, R.S. and K.V.S.; funding acquisition, K.V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially funded by the Center for Advanced Multidisciplinary Research and Innovation. Chennai Institute of Technology, India, vide funding number CIT/CAMRI/2025/3DP/001.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article. Should further data or information be required, these are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maniraj, M.; Kumar, S.R. Design for Additive Manufacturing: Bridging Creativity and Precision in the 3D Printing Era. In Modeling, Analysis, and Control of 3D Printing Processes; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Martins, P. Head-to-Head Evaluation of FDM and SLA in Additive Manufacturing: Performance, Cost, and Environmental Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ravichandran, D.; Ramanathan, A.; Sobczak, M.T.; Sacco, A.F.; Patil, D.; Thummalapalli, S.V.; Pulido, T.V.; Lancaster, J.N.; et al. 3D-Printed Polymeric Biomaterials for Health Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2402571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, W.-J.; Wang, S.-Q.; Wang, Z.-H.; Wu, F.-B.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Ouyang, J.-H.; Wang, Y.-M.; Zou, Y.-C. Additive Manufacturing of Advanced Structural Ceramics for Tribological Applications: Principles, Techniques, Microstructure and Properties. Lubricants 2025, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R. Optimizing process parameters for enhanced mechanical performance in 3D printed impellers using graphene-reinforced polylactic acid (G-PLA) filament. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2025, 39, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, I.; Bajwa, D.; Raeisi, A. A review on the wear performance of additively manufactured 316L stainless steel: Process, structure, and performance. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 5686–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacșa, A.; Diniță, A.; Iacob, Ș.V. Can the Dimensional Optimisation of 3D FDM-Manufactured Parts Be a Solution for a Correct Design? Materials 2025, 18, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.N.; Sarker, O.S.; Dhar, N.R. Parametric optimization and sensitivity analysis of the integrated Taguchi-CRITIC-EDAS method to enhance the surface quality and tensile test behavior of 3D printed PLA and ABS parts. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chang, L. Development of Wear-Resistant Polymeric Materials Using Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Technologies: A Review. Lubricants 2025, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadauw, A.A.A. Neural Network Optimization of Mechanical Properties of ABS-like Photopolymer Utilizing Stereolithography (SLA) 3D Printing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.C.; Saha, R.K.; Mollah, E.; Rakib, S.; Ali, Y. Enhancing mechanical and surface properties of 3D-Printed Kevlar-reinforced ABS/PLA composites through FDM process. Hybrid Adv. 2025, 11, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, M.S.; Elsayed, A.E. Surface Roughness Quality and Dimensional Accuracy—A Comprehensive Analysis of 100% Infill Printed Parts Fabricated by a Personal/Desktop Cost-Effective FDM 3D Printer. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9, 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Chua, M.H.; Ong, P.J.; Lee, J.J.C.; Chin, K.L.O.; Wang, S.; Kai, D.; Ji, R.; Kong, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. Recent advances in nanotech-nology-based functional coatings for the built environment. Mater. Today Adv. 2022, 15, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Ripin, Z.M.; Pasang, T.; Jiang, C.-P. Surface Engineering of Metals: Techniques, Characterizations and Applications. Metals 2023, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, S. Surface Finishing Techniques for Additive Manufactured Parts. In Biomaterials and Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Demircali, A.A.; Yilmaz, D.; Yilmaz, A.; Keskin, O.; Keshavarz, M.; Uvet, H. Enhancing mechanical properties and surface quality of FDM-printed ABS: A comprehensive study on cold acetone vapor treatment. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 4027–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburrino, F.; Barone, S.; Paoli, A.; Razionale, A.V. Post-processing treatments to enhance additively manufactured polymeric parts: A review. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2021, 16, 221–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.Y.; Muhammad, N.; Noor, S.N.F.M.; Rahim, S.Z.A.; Saleh, M.S.; Muhammad, N.A.; Ahmad, A.H.; Muduli, K. Effects of fused deposition modeling (FDM) printing parameters on quality aspects of polycaprolactone (PCL) for coronary stent applications: A review. J. Biomater. Appl. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetto, A.; Bottini, L. Design for manufacturing of surfaces to improve accuracy in Fused Deposition Modeling. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2016, 37, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, K.L.; Udhayakumar, M.; Radhika, N. A Comprehensive Review on Various Ceramic Nanomaterial Coatings Over Metallic Substrates: Applications, Challenges and Future Trends. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2023, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeldinger, C.; Seynstahl, A.; Rosnitschek, T.; Tremmel, S. Surface Properties and Tribological Behavior of Additively Manufactured Components: A Systematic Review. Lubricants 2023, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Moharana, A.P.; Kumar, V.; Tyagi, R.; Dixit, A.R. Emerging Applications of 3D-Printed Parts with Enhanced Tribological Properties. In Tribological Aspects of Additive Manufacturing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 203–229. [Google Scholar]

- Farimani, F.S.; de Rooij, M.; Hekman, E.; Misra, S. Frictional characteristics of Fusion Deposition Modeling (FDM) manufactured surfaces. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepelnjak, T.; Stojšić, J.; Sevšek, L.; Movrin, D.; Milutinović, M. Influence of Process Parameters on the Characteristics of Additively Manufactured Parts Made from Advanced Biopolymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillosu, C. Additive Manufacturing of Bioactive Glass Scaffolds for Bone Repair by Stereolithography. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, T.; Ghosh, S.B.; Bandyopadhyay-Ghosh, S.; Sain, M. Is it possible to 3D bioprint load-bearing bone implants? A critical review. Biofabrication 2023, 15, 042003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemon, L. Material Quality and Process Monitoring in Metal Additive Manufacturing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.-L.; Zhao, J.-J.; Yan, H.-Y.; Lai, Q.-Y.; Huang, R.-Q.; Liu, X.-W.; Li, Y.-C. Deformation and failure of a high-steep slope induced by multi-layer coal mining. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 2942–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaros, A.; Soulis, E.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Ganetsos, T. Advanced Composite Materials Utilized in FDM/FFF 3D Printing Manufacturing Processes: The Case of Filled Filaments. Materials 2023, 16, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Dua, S.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, S.K.; Senthilkumar, T. A comprehensive review on fillers and mechanical properties of 3D printed polymer composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, R.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S.; Oladijo, O.P.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Advances in lightweight composite structures and manufacturing technologies: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, S.; Mishra, R.S. Building without melting: A short review of friction-based additive manufacturing techniques. Int. J. Addit. Subtractive Mater. Manuf. 2017, 1, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Rathee, S.; Maheshwari, S.; Siddiquee, A.N.; Kundra, T.K. A Review on Recent Progress in Solid State Friction Based Metal Additive Manufacturing: Friction Stir Additive Techniques. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2019, 44, 345–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.I.; Antunes, M. Foams: Polylactic Acid-Based System for Tissue Engineering. In Encyclopedia of Biomedical Polymers and Polymeric Biomaterials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; Volume 11, pp. 3469–3488. [Google Scholar]

- Riccio, C.; Civera, M.; Ruiz, O.G.; Pedullà, P.; Reinoso, M.R.; Tommasi, G.; Vollaro, M.; Burgio, V.; Surace, C. Effects of Curing on Photosensitive Resins in SLA Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Mech. 2021, 2, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maines, E.M.; Porwal, M.K.; Ellison, C.J.; Reineke, T.M. Sustainable advances in SLA/DLP 3D printing materials and processes. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 6863–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, S.C.; Liska, R.; Stampfl, J.; Gurr, M.; Mülhaupt, R. Polymers for 3D printing and customized additive manufacturing. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10212–10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, M.; Rivera-Armenta, J.L.; Cruz, B.A.S. Polymeric additive manufacturing: The necessity and utility of rheology. Polym. Rheol. 2018, 10, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtis, K.E.; Stewart, L.K.; Grubert, E.A.; Rios, R.T.; Lolli, F.; Kopp, T.; Tom, R.; Devon, G.; Paredes, S. Recommendations for Future Specifications to Ensure Durable Next Generation of Concrete (No. FHWA-GA-24-2019); Department of Transportation, Office of Performance-Based Management & Research: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024.

- Yadav, S.; Rab, S.; Wan, M. Metrology and sustainability in Industry 6.0: Navigating a new paradigm. In Handbook of Quality System, Accreditation and Conformity Assessment; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 855–885. [Google Scholar]

- Sonkaria, S.; Khare, V. Exploring the landscape between synthetic and biosynthetic materials discovery: Important considerations via systems connectivity, cooperation and scale-driven convergence in biomanufacturing. Biomanufacturing Rev. 2020, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzali, S.; Elwasli, F.; Mezlini, S.; Hajlaoui, K.; Ksir, H. Experimental investigation of tribological behavior of FDM-PLA surfaces. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2025, 239, 760–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesha, T.; Kumar, K.V.P.; Reddy, M.R.T.; Sankarathil, A.J.; Raju, K.; Junaidi, A.R.; Bhat, S.K.; Shashidhara, L.C.; Revanna, K.; Raghavendra, N.; et al. Investigation of Tribological Behavior of Fused Deposition Modelling Processed Parts of Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol Polymer Material. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. D 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zheng, B.; Khan, M.; He, F. Influence of sliding direction relative to layer orientation on tribological performance, noise, and stability in 3D-printed ABS components. Tribol. Int. 2025, 210, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.U.K.; Narala, S.K.R.; Verma, P.C.; Babu, P.J.; Saravanan, P. A Comprehensive Study on the Tribological Behavior of Extruded and 3D-Printed PEEK for Low-Cost Dental Implant Solutions Under Simulated Oral Conditions. Tribol. Lett. 2025, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; He, F.; Khan, M. Optimization of Printing Parameters for Self-Lubricating Polymeric Materials Fabricated via Fused Deposition Modelling. Polymers 2025, 17, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, E. Investigation of material extrusion parameters and printing material impacts on wear and friction using the Taguchi method. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2025, 31, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktaş, İ.; Akıncıoğlu, S. Investigation of tribological properties of industrial products with different patterns produced by 3D printing using polylactic acid. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2025, 31, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Guo, R.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhu, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, X. Enhanced interlayer adhesion and regulated tribological behaviors of 3D printed poly(ether ether ketone) by annealing. Tribol. Int. 2025, 202, 110362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hua, C.; Lin, L. Effect of the metallic substrates on the tribological performance of fused filament fabricated sliding layers made of PEEK-based materials. Wear 2025, 576–577, 206142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Gnanamoorthy, R. Dry sliding wear behaviour of 3D printed Polyetheretherketone with varying layer thickness. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 148, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.M.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, C.L. Influence of printing angle and surface polishing on the friction and wear behavior of DLP-printed polyurethane. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 45, 112446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, M.; Petrescu, M.G.; Ripeanu, R.G.; Laudacescu, E.; Tănase, M. Experimental Research on the Tribological Behavior of Plastic Materials with Friction Properties, with Applications to Manipulators in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Coatings 2025, 15, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, E.; Akıncıoğlu, G.; Şirin, E. A Comparative Study on Friction Performance and Mechanical Properties of Printed PETG Materials With Different Patterns. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.; Ranjan, N.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Tripathi, A.; Kumar, R. Investigation of wettability and wear properties on 3D printed Polylactic acid/Molybdenum disulfide-Silicon carbide polymeric composite for sustainable biomedical applications. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2025, 38, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, G.; Sostizzo, G.G.; Gehlen, G.D.S.; Birosz, M.T.; Andó, M.; Souza, R.H.D.S.; Neis, P.D. Exploring the Tribological Properties of 3D Printed Polymer Composites: An Experimental Study. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5216948 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Palaniyappan, S.; Sivakumar, N.K.; Annamalai, G.; Bodaghi, M.; Saravanamuthukumar, P.; Alageel, O.; Basavarajappa, S.; Hashem, M.I. Mechanical and tribological behaviour of three-dimensional printed almond shell particles reinforced polylactic acid bio-composites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2025, 239, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Gnanamoorthy, R. Friction Performance of Three-Dimension Printed PEEK for Journal Bearing Application Under Grease Lubrication. J. Tribol. 2025, 147, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, P.; Opałka, M. Enhanced Tribological Performance of 3D-Printed Polymer Composites with Graphite, Mos2, and Ptfe Lubricants Via Digital Light Processing (Dlp) Technology. Mos2, and Ptfe Lubricants Via Digital Light Processing (Dlp) Technology. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5166686 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Atlıhan, G. Investigation on Wear Behavior of PETG and PLA Parts Fabricated with Fused Deposition Modelling Under Different Wear Conditions. Polym. Korea 2023, 47, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, V.C.; Schneider, B.; Brede, M. On the fatigue behavior of notched structural adhesives with considerations of mechanical properties and stress concentration effects. Procedia Eng. 2018, 213, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancaktar, E. Fracture aspects of adhesive joints: Material, fatigue, interphase, and stress concentration considerations. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1995, 9, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, B. Adhesive wear failures. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2022, 22, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ding, H.; Lewis, R.; Lin, Q.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z. Wear and rolling contact fatigue competition mechanism of different types of rail steels under various slip ratios. Wear 2023, 522, 204721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.U.; Kesavan, D.; Ramaseshan, R.; Kamaraj, M. Fretting Wear Behavior of LPBF Ti-6Al-4V Alloy: Influence of Annealing and Anodizing. J. Tribol. 2025, 147, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.I.; Dorazio, A.; Burris, D.L. Polymers Tribology Exposed: Eliminating Transfer Film Effects to Clarify Ultralow Wear of PTFE. Tribol. Lett. 2020, 68, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zor, M.; Mengeloğlu, F.; Aydemir, D.; Şen, F.; Kocatürk, E.; Candan, Z.; Ozcelik, O. Wood plastic composites (WPCs): Applications of nanomaterials. In Emerging Nanomaterials: Opportunities and Challenges in Forestry Sectors; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 97–133. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, H.; Hoque, M.E. Polymer nanocomposites for packaging. Adv. Polym. Nanocomposites 2022, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKellop, H.; Clarke, I.; Markolf, K.; Amstutz, H. Friction and wear properties of polymer, metal, and ceramic prosthetic joint materials evaluated on a multichannel screening device. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1981, 15, 619–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Huang, H.; Han, Y.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M. Peek and Wc Synergistic Enhance the High Temperature Tribological Performance of Ptfe Matrix Composites in Air. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5034589 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Chen, Z.; He, X.; Xiao, C.; Kim, S.H. Effect of Humidity on Friction and Wear—A Critical Review. Lubricants 2018, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, J. A review of the influence of environmental humidity and water on friction, lubrication and wear. Tribol. Int. 1990, 23, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheideler, W.J.; Im, J. Recent Advances in 3D Printed Electrodes—Bridging the Nano to Mesoscale. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2411951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douba, A.E. Nano-Engineered Cement for 3D Printing Concrete; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Banerjee, M.S. Tribological aspects of polymers and their composites used in additive manufacturing-a review. In Proceedings of the BALTTRIB, Proceedings of the International Conference, Kaunas, Lithuania, 22–24 September 2022; No. 11. pp. 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.K.; Kesarwani, S.; Xu, J.; Davim, J.P. (Eds.) Polymer Nanocomposites: Fabrication to Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Swathi, M.B.; Girish, D.P.; Dinesh, M.H.; Keshavamurthy, R.; Manjunatha, K. Taguchi-Based Analysis of Wear Performance in SLA Printed Boron Nitride Composites. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2025, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, N.P.; Sharma, S.C.; Adarsha, H.; Keshavamurthy, R. Tribological Performance of PEEK/GO Nano-composites Fabricated via Stereolithography. J. Bio-Tribo-Corros. 2025, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snarski-Adamski, A.; Pieniak, D.; Krzysiak, Z.; Firlej, M.; Brumerčík, F. Evaluation of the Tribological Behavior of Materials Used for the Production of Orthodontic Devices in 3D DLP Printing Technology, Due to Oral Cavity Environmental Factors. Materials 2025, 18, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; De, S.; Khaleghian, M.; Emami, A. Comparative tribological and drainage performance of additively manufactured outsoles tread designs. Friction 2025, 13, 9441024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Xin, Z.; Jiao, Z. Three-Dimensional-Printed Biomimetic Structural Ceramics with Excellent Tribological Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Guo, J.; Fan, L.; Zhang, X.; Mo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, P.; Ma, Y.; Hao, Z. Wear behavior and biological properties of 3D-printed zirconia by stereolithography apparatus after low temperature degradation. Ceram. Int. 2025, 9, 11702–11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; De, S.; Khaleghian, M.; Emami, A. Wear Resistance of Additively Manufactured Footwear Soles. Lubricants 2025, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozior, T.; Hanon, M.M.; Zmarzły, P.; Gogolewski, D.; Rudnik, M.; Szot, W. Evaluation of the Influence of Technological Parameters of Selected 3D Printing Technologies on Tribological Properties. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 11, e1567–e1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Ranjan, N. Impact of 3D Printing Process Parameters on Tribological Behaviour of Polymers. In Tribological Aspects of Additive Manufacturing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Du, G.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Bian, D.; Zhang, X. Tribological behavior of 3D printed nanofluid reinforced photosensitive self-lubricating polymer materials. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 80, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, P.; Opałka, M. Enhanced Tribological Performance of Dlp 3D Printed Composites with Solid Lubricant Additives–Graphite, Ptfe, Mos2. Ptfe, Mos2. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4812628 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Onu, P.; Lawal, S.L. Tribological Considerations in Additive Manufacturing: 3D Printing Materials and Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Driving Sustainable Development Goals (SEB4SDG), Omu-Aran, Nigeria, 2–4 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, O.; Mbohwa, C. Sustainable Production in 3D Printing: Understanding the interplay between surface roughness and tribology in Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 5th African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Johannesburg, South Africa, 23–25 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pieniak, D.; Michalczewski, R.; Firlej, M.; Krzysiak, Z.; Przystupa, K.; Kalbarczyk, M.; Osuch-Słomka, E.; Snarski-Adamski, A.; Gil, L.; Seykorova, M. Surface Layer Performance of Low-Cost 3D-Printed Sliding Components in Metal-Polymer Friction. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2024, 30, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channi, H.K. Tribological effect of 3D printing in industrial applications. In Tribological Aspects of Additive Manufacturing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, A.M.A.-E.; Mahmoud, M.; Marzouk, W.; Nafea, M.; Elsheikh, A.; Mourad, A.-H.I.; Ibrahim, A.M.M. Tribological characteristics of porous 3D-printed PLA+ with anaerobic methacrylate self-impregnated lubricant. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liow, Y.H.; Ismail, K.I.; Yap, T.C. Tribology Behavior of In-Situ FDM 3D Printed Glass Fibre-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. J. Res. Updat. Polym. Sci. 2024, 13, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebrahim, M.; Ghazali, M.J.; Jamadon, N.H.; Otsuka, Y. Advancements in Ceramic Additive Manufacturing: A Focus on Direct Ink Writing (Diw) Method and Tribological Behaviour of 3D Printed Ceramics. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4912540 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Stravinskas, K.; Shahidi, A.; Kapustynskyi, O.; Matijošius, T.; Vishniakov, N.; Mordas, G. Characterization of SLA-printed ceramic composites for dental restorations. Lith. J. Phys. 2024, 64, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudinejad, A. Vat photopolymerization methods in additive manufacturing. In Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Pagac, M.; Hajnys, J.; Ma, Q.-P.; Jancar, L.; Jansa, J.; Stefek, P.; Mesicek, J. A Review of Vat Photopolymerization Technology: Materials, Applications, Challenges, and Future Trends of 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahati, D.; Bricha, M.; El Mabrouk, K. Vat Photopolymerization Additive Manufacturing Technology for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2200859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuhamillage, G.A.; Chartrain, N.; Meenakshisundaram, V.; Feller, K.D.; Williams, C.B.; Long, T.E. 110th Anniversary: Vat Photopolymerization-Based Additive Manufacturing: Current Trends and Future Directions in Materials Design. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 15109–15118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhamannil, R.V.; Govindan, P. Current state and future scope of additive manufacturing technologies via vat photopolymerization. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 43, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y. Recent trends in advanced photoinitiators for vat photopolymerization 3D printing. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2200202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra-Cascón, W.; Krishnamurthy, V.R.; Att, W.; Revilla-León, M. 3D printing parameters, supporting structures, slicing, and post-processing procedures of vat-polymerization additive manufacturing technologies: A narrative review. J. Dent. 2021, 109, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.K.; Leung, A.C. Dental implants in reconstructed jaws: Implant longevity and peri-implant tissue outcomes. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, D.D.S. Present status of immediate loading of oral implants. J. Oral Implantol. 2004, 30, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoca, S.; Aydin, C.; Yilmaz, H.; Bal, B.T. Survival rates and periimplant soft tissue evaluation of extraoral implants over a mean follow-up period of three years. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2008, 100, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojak, V.; Jain, J.K.; Singhal, T.S.; Saxena, K.K.; Prakash, C.; Agrawal, M.K.; Malik, V. Friction stir processing and cladding: An innovative surface engineering technique to tailor magnesium-based alloys for bio-medical implants. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2025, 32, 2340007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, K.; Kavinkumar, T.; Shafi, P.M.; Shobin, L.; Mangalaraja, R.V.; Bhaviripudi, V.R.; Abarzúa, C.V.; Thirumurugan, A. Synthesis and surface engineering of carbon-modified cobalt ferrite for advanced supercapacitor electrode materials. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 171, 113534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Tünçay, M.M. Surface engineering of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloys: A comparative study on micro/nanoscale topographies for biomedical applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Peng, J.; Song, H.; Chen, C. Surface engineering of MIL-88(Fe) toward enhanced adsorption of radioactive strontium. J. Water Process. Eng. 2025, 69, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, N.N.; Mulay, A.V. Post Processing Methods used to Improve Surface Finish of Products which are Manufactured by Additive Manufacturing Technologies: A Review. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2018, 99, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, J.S.; Singh, R. Pre and post processing techniques to improve surface characteristics of FDM parts: A state of art review and future applications. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Shao, Q.; Li, K.; Gao, Y.; Wei, B.; Cai, Z.; Zheng, K.; Feng, P.; Lv, Z.; Ling, Y. Constructing chromium-tolerance La0. 6Sr0. 4Co0. 2Fe0. 8O3-δ cathode for solid oxide fuel cells using entropy-assisted surface engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaros, A.; Ganetsos, T.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Ungureanu, L.M.; Munteanu, I.S. Post-Production Finishing Processes Utilized in 3D Printing Technologies. Processes 2024, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, P.; Song, G.; Chang, C. Reversible Surface Engineering of Cellulose Elementary Fibrils: From Ultralong Nanocelluloses to Advanced Cellulosic Materials. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2312220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xue, P.; Fang, S.; Gao, M.; Yan, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Cheng, B. Boosting the output performance of triboelectric nanogenerators via surface engineering and structure designing. Mater. Horizons 2024, 11, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, A.B.G.; Kaliyannan, G.V.; Gunasekaran, R.; Rathanasamy, R.; Palaniappan, S.K.; Alkallas, F.H.; Elsharkawy, W.; Mostafa, A.M. Surface engineering of Sio2-Zro2 films for augmenting power conversion efficiency performance of silicon solar cells. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Bai, J.; Zhang, J. 3D-Printed Liquid Metal-in-Hydrogel Solar Evaporator: Merging Spectrum-Manipulated Micro-Nano Architecture and Surface Engineering for Solar Desalination. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 5847–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chu, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, P.; Deng, Q.; Chen, C.; Huang, K.; Yang, C.; Lu, J. Mitigating Planar Gliding in Single-Crystal Nickel-Rich Cathodes through Multifunctional Composite Surface Engineering. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, V.-H.; Lee, J.-M. Surface engineering for stable electrocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2693–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Bao, Y.; Ma, T.; Tsuchikawa, S.; Inagaki, T.; Wang, H.; Jiang, H. Intelligent monitoring of post-processing characteristics in 3D-printed food products: A focus on fermentation process of starch-gluten mixture using NIR and multivariate analysis. J. Food Eng. 2025, 388, 112357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntoğlu, M.; Salur, E.; Gupta, M.K.; Waqar, S.; Szczotkarz, N.; Vashishtha, G.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Krolczyk, G.M.; Aslan, A.; Binali, R. A review on surface morphology and tribological behavior of titanium alloys via SLM processing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2025, 31, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutz, C.M.; Hrynuk, J.T. On the use of Mahalanobis distance in particle image velocimetry post-processing. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 158, 109935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, K.; Li, J.; Geng, S. A Review on Corrosion Behavior and Surface Modification Technology of Nickel Aluminum Bronze Alloys: Current Research and Prospects. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Yang, B.; Yang, B.; Yang, J.; Su, K.; Ma, P.; Deng, Y.; et al. A surface engineering strategy for the stabilization of zinc metal anodes with montmorillonite layers toward long-life rechargeable aqueous zinc ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 100, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chang, J.; Chen, L.; Weng, D.; Yu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. A laser-processed micro/nanostructures surface and its photothermal de-icing and self-cleaning performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 655, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrlybayev, D.; Seisekulova, A.; Talamona, D.; Perveen, A. The Post-Processing of Additive Manufactured Polymeric and Metallic Parts. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, Y.; Tascioglu, E. Post-processing effects on the surface characteristics of Inconel 718 alloy fabricated by selective laser melting additive manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 5, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavcar, B.; Sagbas, B. Mechanical post-processing techniques for metal additive manufacturing. In Post-Processing Techniques for Additive Manufacturing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Basha, S.; Venkaiah, N.; Srivatsan, T.; Sankar, M. Post-processing techniques for metal Additive Manufactured products: Role and contribution of abrasive media assisted finishing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2024, 39, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.W.; Mali, H.S.; Meena, A.; Ahmad, S.; Puerta, A.P.V.; Kunkel, M.E. A critical review of mechanical-based post-processing techniques for additively manufactured parts. In Post-Processing Techniques for Additive Manufacturing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Ali, P.; Matraf, M.O.A.B.; Hashmi, A.W.; Ahmad, S.; Tian, Y.; Iqbal, F. Precision finishing innovations: Recent advances in abrasive flow machining, magnetic abrasive finishing, and magnetorheological finishing. In Nanofinishing of Materials for Advanced Industrial Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Demisse, W.; Xu, J.; Rice, L.; Tyagi, P. Review of internal and external surface finishing technologies for additively manufactured metallic alloys components and new frontiers. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 1433–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]