Analysis of Gender Diversity Initiatives to Empower Women in the Australian Construction Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

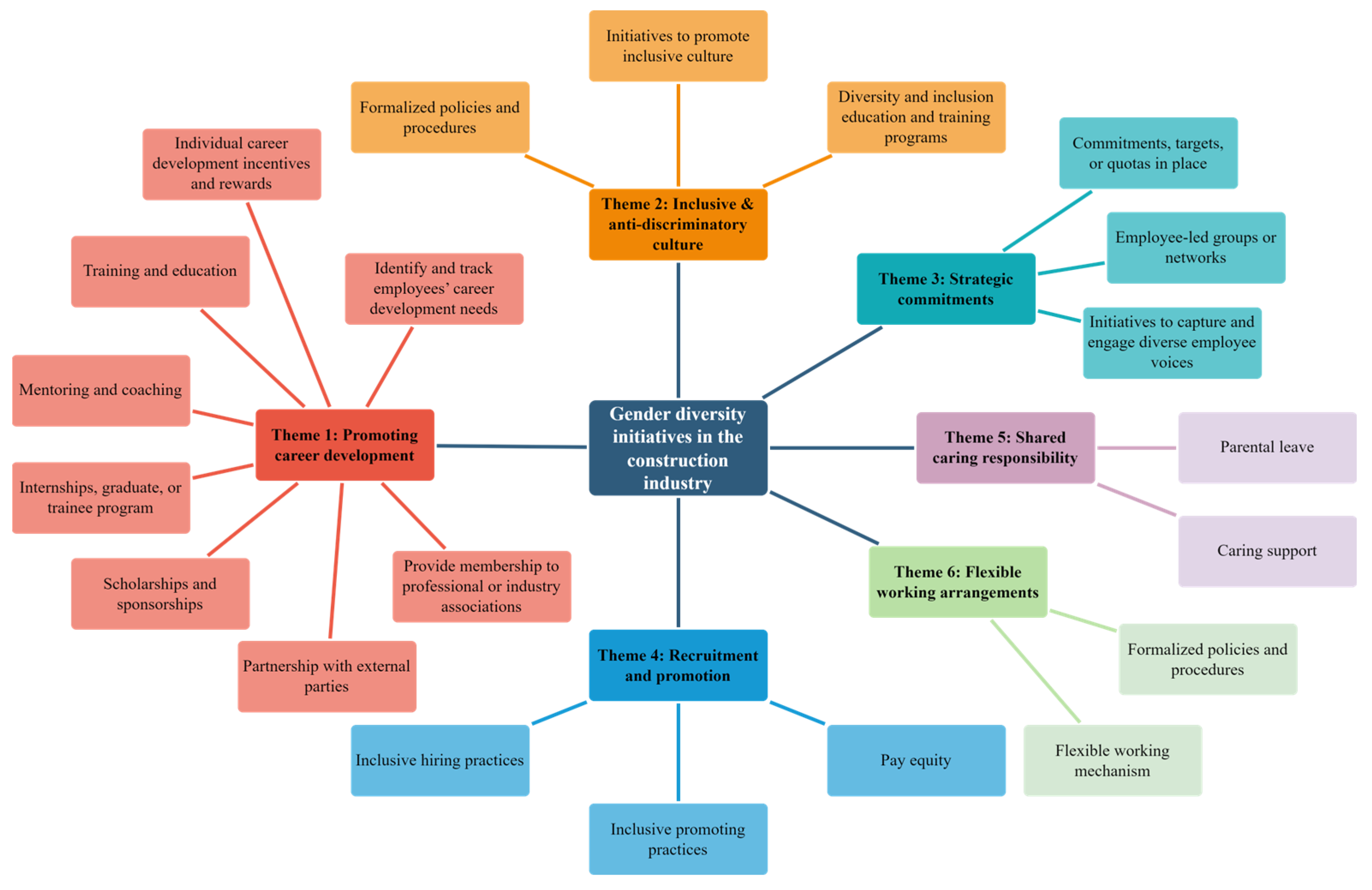

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Promoting Career Development

3.1.1. Identify and Track Employees’ Career Development Needs

3.1.2. Individual Career Development Incentives and Rewards

3.1.3. Training and Education

3.1.4. Mentoring and Coaching

3.1.5. Internships, Graduate, or Trainee Program

3.1.6. Scholarships and Sponsorships

3.1.7. Partnership with External Parties

3.1.8. Providing Membership to Professional or Industry Associations

3.2. Theme 2: Inclusive and Anti-Discriminatory Culture

3.2.1. Formalize Policies and Procedures

3.2.2. Initiatives to Promote Inclusive Culture

3.2.3. Diversity and Inclusion Education and Training Programs

3.3. Theme 3: Strategic Commitments

3.3.1. Commitments, Targets or Quotas in Place to Increase or Maintain Gender Diversity

3.3.2. Employee-Led Groups or Networks

3.3.3. Initiatives to Capture and Engage Diverse Employee Voices

3.4. Theme 4: Recruitment and Promotion

3.4.1. Inclusive Hiring Practices

3.4.2. Inclusive Promoting Practices

3.4.3. Pay Equity

3.5. Theme 5: Shared Caring Responsibility

3.5.1. Parental Leave

3.5.2. Caring Support

3.6. Theme 6: Flexible Working Arrangements

3.6.1. Formalize Policies and Procedures

3.6.2. Flexible Working Mechanism

4. Discussion and Recommendations

4.1. Theme 1: Promoting Career Development

4.2. Theme 2: Inclusive and Anti-Discriminatory Culture

4.3. Theme 3: Strategic Commitments

4.4. Theme 4: Recruitment and Promotion

4.5. Theme 5: Shared Caring Responsibility

4.6. Theme 6: Flexible Working Arrangements

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ABS. Table 04—Employed Persons by Industry Division of Main Job (ANZSIC)—Trend, Seasonally Adjusted, and Original. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia-detailed/latest-release#industry-occupation-and-sector (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- ABS. Sex by Industry. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/characteristics-spotlight-2022#sex-by-industry (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Jobs and Skills Australia. Overview—Snapshot. Available online: https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/industries/industry-details?industryCode=E#1 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- WGEA. Australia’s Gender Equality Scorecard 2022-23; Workplace Gender Equality Agency: Sydney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Almost Half a Million Job Vacancies in May. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/almost-half-million-job-vacancies-may (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- NAWIC. About Us. Available online: https://www.nawic.com.au/NAWIC/NAWIC/About/About_Us.aspx?hkey=85211aaf-f4fc-447a-9c30-2ec16a5cc3ff (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- WGEA. What We Do. Available online: https://www.wgea.gov.au/what-we-do (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- UNSW Sydney. Funding to Help Empower Women Working in Construction. Available online: https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/general/funding-help-empower-women-working-construction (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Englewood Cliffs Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, V.P.; Shaffer, M.A. Career success: The effects of personality. Career Dev. Int. 1999, 4, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment theory. In Handbook of Community Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Holzner, B.; Neuhold, B.; Weiss-Ganger, A. Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women: Policy Document; Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, M. Power and the Powerless; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gilat, A. “The Courage to Express Myself”: Muslim women’s narrative of self-empowerment and personal development through university studies. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 45, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Mussi, E.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Analysing gender issues in the Australian construction industry through the lens of empowerment. Buildings 2021, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, J. Empowerment examined. Dev. Pract. 1995, 5, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Kelleher, D. Institutions, organisations and gender equality in an era of globalisation. Gend. Dev. 2003, 11, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardini, S.; Bowman, K.; Garwood, R. A’How To’Guide to Measuring Women’s Empowerment: Sharing experience from Oxfam’s Impact Evaluations; Oxfam GB: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.; Kelleher, D. Leadership for social transformation: Some ideas and questions on institutions and feminist leadership. Gend. Dev. 2000, 8, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manesh, S.N.; Choi, J.O.; Shrestha, B.K.; Lim, J.; Shrestha, P.P. Spatial analysis of the gender wage gap in architecture, civil engineering, and construction occupations in the United States. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.O.; Akinbo, F.T.; Akinola, A. Improving career development through a Women mentoring program in the construction industry. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1378, 042031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, E.O.; Yu, J.; Hale, S.; Booth, N. The Impact of External and Internal Sources of Motivation on Young Women’s Interest in Construction-Related Careers: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2022, 18, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbaripour, A.N.; Tumpa, R.J.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Zhang, W.; Yousefian, P.; Camozzi, R.N.; Hon, C.; Talebian, N.; Liu, T.; Hemmati, M. Retention over Attraction: A Review of Women’s Experiences in the Australian Construction Industry; Challenges and Solutions. Buildings 2023, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Zhang, R.P.; Holdsworth, S.; Andamon, M.M. Taking a broader approach to women’s retention in construction: Incorporating the university domain. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual ARCOM Conference (ARCOM 2021), Leeds, UK, 6–7 September 2021; pp. 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ayarkwa, J.; Agyekum, K.; Acheampong, A. Ghanaian construction professionals’ perception on challenges to female retention in the construction industry. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 2012, 2, 360–376. [Google Scholar]

- ACA. Members. Available online: https://www.constructors.com.au/members/ (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Allsop, D.B.; Chelladurai, J.M.; Kimball, E.R.; Marks, L.D.; Hendricks, J.J. Qualitative methods with Nvivo software: A practical guide for analyzing qualitative data. Psych 2022, 4, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.W.; Li, H. Job performance evaluation for construction companies: An analytic network process approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2006, 132, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A.; Williams, N. Second-generation gender bias: An exploratory study of the women’s leadership gap in a UK construction organisation. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2019, 35, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, M.; Male, S.; Lord, L. Women engineers’ advancement to management and leadership roles—Enabling resources and implications for higher education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021; pp. 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, V. What influences professional women’s career advancement in construction? Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.L.; Sexton, M. Career journeys and turning points of senior female managers in small construction firms. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, K.; Amos-Abanyie, S.; Kumah, V.M.A.; Kukah, A.S.K.; Salgin, B. Obstacles to the career progression of professional female project managers (PFPMs) in the Ghanaian construction industry. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2022, 31, 200–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, R.; Webster, M.; Campbell, K.M. An evaluation of partnership development in the construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Bridgeman, J. Corporate volunteering in the construction industry: Motivations, costs and benefits. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.E.; Hon, C.K.; Xia, B.; Lamari, F. Challenges, success factors and strategies for women’s career development in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Econ. Build. 2017, 17, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, N.G.; Amaratunga, D.; Haigh, R. The career advancement of the professional women in the UK construction industry: The career success factors. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2014, 12, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Astor, E.; Román-Onsalo, M.; Infante-Perea, M. Women’s career development in the construction industry across 15 years: Main barriers. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, T.; Far, H.; Gardner, A. Barriers to career advancement for female engineers in Australia’s civil construction industry and recommended solutions. Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye-Nimo, E.; Wood, H.; Collison, J. Complexity of women’s modern-day challenges in construction. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2019, 26, 2550–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.; Dominguez, A. Women in Construction Engineering: Improving the Students’ Experience throughout their Careers. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Virtual, 26–29 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, M.M.; Arfken, D.E.; Bellar, S. The importance of mentoring and sponsorship in women’s career development. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2016, 81, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sinyard, R.D.; Veeramani, A.; Rouanet, E.; Anteby, R.; Petrusa, E.; Phitayakorn, R.; Gee, D.; Terhune, K. Gaps in Practice Management Skills After Training: A Qualitative Needs Assessment of Early Career Surgeons. J. Surg. Educ. 2022, 79, e151–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeldt, A.R. Perceived importance of leadership in their future careers relative to other foundational, technical and professional skills among senior civil engineering students. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 24–27 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.P.; Holdsworth, S.; Turner, M.; Andamon, M.M. Does gender really matter? A closer look at early career women in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantidis, A.D.; Chatzoglou, P.D. Employee post-training behaviour and performance: Evaluating the results of the training process. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 18, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehale, K.D.; Govender, C.M.; Mabaso, C.M. Maximising training evaluation for employee performance improvement. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrenoud, A.J.; Bigelow, B.F.; Perkins, E.M. Advancing Women in Construction: Gender Differences in Attraction and Retention Factors with Managers in the Electrical Construction Industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekchiri, S.; Kamm, J.D. Navigating barriers faced by women in leadership positions in the US construction industry: A retrospective on women’s continued struggle in a male-dominated industry. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Powell, A.; Loosemore, M.; Chappell, L. Designing robust and revisable policies for gender equality: Lessons from the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackrill, R.; Caven, V.; Alaktif, J. ‘Black Boxes’ and ‘fracture points’: The regulation of gender equality in the UK and French construction industries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 3027–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, B.C. Organization culture as driver of competitive advantage. J. Acad. Bus. Ethics 2012, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Blaique, L.; Pinnington, A.H. Occupational commitment of women working in SET: The impact of coping self-efficacy and mentoring. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2022, 32, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.A. Conclusion: Progress and policies towards a gender-even playing field. In Gender and Diplomacy; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Occupational Challenges of Women in Construction Industry: Development of Overcoming Strategies Using Delphi Technique. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2023, 15, 04522028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, P.J.; Erfani, A.; Cui, Q. Use of LinkedIn Data and Machine Learning to Analyze Gender Differences in Construction Career Paths. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Wang, C.C.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Framework for Promoting Women’s Career Development across Career Stages in the Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes/Initiatives | Number of Files | Number of References |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Promoting career development | 25 | 133 |

| (1) Identify and track employees’ career development needs | 7 | 9 |

| (2) Individual career development incentives and rewards | 7 | 18 |

| (3) Training and education | 21 | 45 |

| (4) Mentoring and coaching | 8 | 15 |

| (5) Internships, graduate, or trainee program | 7 | 14 |

| (6) Scholarships and sponsorships | 10 | 13 |

| (7) Partnership with external parties | 8 | 13 |

| (8) Providing membership to professional or industry associations | 6 | 6 |

| Theme 2: Inclusive and anti-discriminatory culture | 23 | 82 |

| (1) Formalized policies and procedures | 15 | 35 |

| (2) Initiatives to promote inclusive culture | 18 | 31 |

| (3) Diversity and inclusion education and training programs | 14 | 16 |

| Theme 3: Strategic commitments | 25 | 54 |

| (1) Commitments, targets, or quotas in place | 17 | 27 |

| (2) Employee-led groups or networks | 10 | 11 |

| (3) Initiatives to capture and engage diverse employee voices | 14 | 16 |

| Theme 4: Recruitment and promotion | 19 | 45 |

| (1) Inclusive hiring practices | 16 | 19 |

| (2) Inclusive promoting practices | 10 | 12 |

| (3) Pay equity | 11 | 14 |

| Theme 5: Shared caring responsibility | 12 | 29 |

| (1) Parental leave | 12 | 16 |

| (2) Caring support | 8 | 13 |

| Theme 6: Flexible working arrangements | 15 | 22 |

| (1) Formalized policies and procedures | 7 | 7 |

| (2) Flexible working mechanism | 14 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, D.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.C. Analysis of Gender Diversity Initiatives to Empower Women in the Australian Construction Industry. Buildings 2024, 14, 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061707

Yan D, Sunindijo RY, Wang CC. Analysis of Gender Diversity Initiatives to Empower Women in the Australian Construction Industry. Buildings. 2024; 14(6):1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061707

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Diya, Riza Yosia Sunindijo, and Cynthia Changxin Wang. 2024. "Analysis of Gender Diversity Initiatives to Empower Women in the Australian Construction Industry" Buildings 14, no. 6: 1707. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061707