Abstract

With the acceleration of urbanization and profound socioeconomic changes, the influx of people from various social strata into cities has led to the phenomenon of residential segregation. Currently, the international community has accumulated profound theoretical foundations and rich practical experiences in the study of residential segregation. This research, primarily based on the WOS literature database, sorts and summarizes relevant studies on residential segregation in recent years (focusing on publications from 2020 to 2024), emphasizing the following four key aspects: (1) tracing the evolution of the theory of residential segregation and analytical methods; (2) analyzing the main characteristics of urban residential segregation; (3) exploring the driving mechanisms and effects of urban residential segregation; and (4) summarizing research trends and providing future perspectives. This study aids urban planners in more accurately identifying areas and characteristics of residential segregation, optimizing urban layouts, and providing richer and more in-depth theoretical support and practical guidance for the field of urban planning science.

1. Introduction

Residential segregation is an important topic of multidisciplinary concern in urban geography, urban economics, and urban sociology. Additionally, it is a key entry point for studying and judging the structure of urban residential space and socio-spatial segregation. In urban space, owing to differences in race, class, income, education level, occupation, and other socio-economic factors, different groups of people show unevenness in geographic distribution, constituting residential segregation. Typically, residential segregation is a collective result of residential choice behavior, but it can also be due to history, policy, discrimination, or other macro-structural factors. Residential segregation involves the most diverse influencing factors. Owing to the complexity of its mechanisms and the limitations of data acquisition, academics have yet to draw uniform and convincing conclusions, making residential segregation a cutting-edge issue that continues to be explored by academics. The research on residential segregation not only profoundly reveals its extensive and profound impact on social structure, urban planning, community development, and public health, but it also further enhances our profound understanding of social stratification. It provides a valuable foundation for exploring and seeking effective strategies to address residential segregation issues, effectively promoting the urban society towards a harmonious and stable future.

The research on this topic involves multiple disciplines, such as urban geography, urban economics, urban sociology, urban management, psychology, institutional economics, and public economics. Scholars have conducted a substantial amount of theoretical and empirical research on this topic since the 1920s. Generally, it can be divided into two stages: the theoretical innovation research from the 1920s to the 1980s, and the theoretical refinement and perspective supplementation research from the 1990s to the present. Both phases are accompanied by the emergence of several empirical research results. During the stage of theoretical innovation research, this field employed various theoretical perspectives, such as ecological theory, consumer behavior theory, family life cycle theory, political economy and public economics theory, neoclassical economics theory, environmental perception theory, the “utility space” perspective, psychological theory, Marxist theory, and urban management theory, to conduct new theoretical research. The following are examples of the models that have been established in the process of theoretical exploration: the “invasion-succession” model, housing filtering theory, life course theory, the “voting with feet” theory (including the Tiebout model), exchange theory, residential utility value theory, housing career theory, and the “migration + search” relocation decision model [1], residential discrete choice modeling, socio-spatial unity theory, and others. Schools such as the human ecology school, the behavioral school, the neoclassical economic school, the neo-Marxist school, the structural school, the urban management school, and so on, have been formed. Subsequent empirical research focuses on the above theoretical perspectives and disciplinary lineage.

Residential segregation leads to the differentiation of different social groups in terms of living space and geographic location. This spatial differentiation is not only reflected in housing types, architectural styles, and facility allocations, but also involves aspects such as residents’ lifestyle [2], socioeconomic status [3], and cultural background [4]. Meanwhile, in terms of spatial characteristics, urban residential segregation mainly manifests as a spatial distribution pattern of homogeneous clustering and heterogeneous segregation. The factors and mechanisms of intra-urban residential segregation are shown to be diversified and complex, involving not only the influence of external environmental characteristics such as location, traffic, landscape, built environment, public services, neighborhood characteristics, safety, social space, policies and regulations, and market system [5,6,7,8] but also the influence of residents’ characteristics (households or individuals) such as the age of residents, gender, occupation, income, education, employment, family composition, lifestyle preferences, family life cycle, psychological factors, and other characteristics of the households (families or individuals) themselves [9,10,11,12]. In addition, institutional [13,14] and market factors [15] in the city generally have a non-negligible moderating effect on residential segregation, jointly constituting its complex driving mechanism. The existence of urban residential segregation leads to issues such as inequality in housing wealth, resource scarcity, and the solidification of class identity [16], further exacerbating social inequality. These issues are also interconnected, forming a complex social phenomenon. However, existing research lacks a systematic analysis of the manifestations of residential segregation in multiple dimensions.

Scholars have conducted in-depth discussions on residential segregation from multiple dimensions. They not only carefully analyzed the differentiation trends in population types and spatial characteristics of residential segregation within cities, but also revealed its complex context and multi-perspective features in the study of its formation mechanism. Given this, a systematic review of theoretical and empirical research on residential segregation in different countries is particularly important, and will help us to summarize research trends and provide inspiration for future research. This research not only has reference value for deepening the academic discussion on the formation mechanism of residential segregation within cities but also provides an important basis for the precise supply of urban space housing and the effective formulation of housing policies. Therefore, the core focuses of this study include: (1) tracing the historical evolution of the theory of residential segregation to understand the evolution and development of its theoretical foundation, providing solid theoretical support for current research; (2) analyzing, in depth, the main characteristics of urban residential segregation, especially the significant differences in population types and spatial distribution, laying the foundation for subsequent mechanism exploration and effect analysis; (3) exploring, in depth, the driving mechanisms and effects of urban residential segregation, revealing the multiple factors and complex relationships behind it; and (4) summarizing research trends and discussing future research directions prospectively, providing directional guidance and inspiration for future research.

The structure of this study is as follows. First, it systematically sorts out the development context of early theories on residential segregation. Second, it summarizes the main characteristics of urban residential segregation, which are mainly reflected in the differentiation of social groups and the uneven spatial distribution. Furthermore, it explores the main driving mechanisms of residential segregation from the dual perspectives of structural and individual factors. Finally, we summarize and conduct in-depth discussions on future research directions and possible limitations. This research aims to provide useful references and insights for academic research and policy formulation on residential segregation within cities.

2. Early Theoretical Developments and Analytical Methods

2.1. Theoretical Development of Residential Segregation

The phenomenon of residential segregation was revealed as early as 1872 in Engels’ “The Housing Question”. In the 1920s, members of the Human Ecology School of Urban Location Research paid attention to the issue of residential segregation. Among them, Burgess (1924) constructed the “invasion-succession” model from the perspective of ecological theory to explain and describe the segregation of different groups and classes in cities [17]. Hoyt (1939) developed the housing filtering theory, which argues that the migration of high-social-status households and the resulting vacant housing is a prerequisite for the choice of housing location and a driving force for residential migration among lower-status classes, emphasizing the dynamics of the housing market, differences in residents’ economic capabilities, and the role of government policies in the formation of residential segregation [18]. However, all their studies remained at the stage of macro-level description and lacked a detailed analysis of the decision-making process at the individual level. In the 1950s–1960s, the public economics/political economy school, the neoclassical economics school, and the behavioral school explained the mechanism of urban residential segregation from different theoretical perspectives. Shevky and Bell (1955) summarized, through the study of the social districts, that economic status, family type, and ethnic background are the three main characteristic elements that influence the residential segregation of urban residents [19]. Rossi’s (1955) study of individual housing choices, based on the perspective of consumer behavior, initiated the behavioral school’s research paradigm of micro-housing segregation. More importantly, he considered the influence of the “family life cycle” in his study and proposed a life course perspective of analysis [20]. Tiebout (1956) put forward the theory of “voting with feet” from the perspectives of political economy and public economics and argued that differences in the level of supply of “local public goods” and the tax systems of different regions determine residential segregation due to differences in the ability to pay and preferences for local public goods, and the classic Tiebout model was constructed [21]. Based on the market equilibrium theory of neoclassical economics, Herbert and Stevens (1960) analyzed residents’ choice of residential location from the perspective of macroeconomic equilibrium under the assumption of “maximization of rental balance” and believed that residents with the highest ability to pay for rent would be given the optimal residential location, which led to the optimal layout of residential space for residents with different abilities to pay [22]. The study primarily explored the probability of residents’ overall housing choice/relocation behavior and its correlation with housing characteristics, demographic characteristics, and socioeconomic factors. Wolpert (1965) argued that location choice originates from environmental perception and proposed the basic concepts and research perspectives of “behavior space” and “place utility”. He introduced environmental perception into the analytical framework of location decision-making, suggesting that residential segregation can be viewed as the outcome of location choices made by different individuals or groups based on their diverse perceptions of the environment and assessments of place utility [23]. The American scholar Kain (1968) proposed the spatial mismatch hypothesis, which focuses on the geospatial separation between employment opportunities for low-income groups in cities, especially minority residents, and their place of residence [24]. Based on the bid–rent theory proposed by Alonso (1964) [25], another representative of the neoclassical economics school, Muth (1969), put forward the “exchange theory” of housing location choice by studying the relationship between urban housing rents and transportation costs. He believed that minimizing the sum of rent and transportation costs can maximize household utility while minimizing costs, which represents the “optimal location” for residential choice. The location choice mechanism, based on the cost–utility tradeoff, has led to the uneven distribution of different income groups in urban space, thus forming the phenomenon of residential segregation [26]. Based on a filter theory perspective, Lansing et al. (1969) analyzed the differential impacts of urban macro-level market environments on the housing choice process of different income classes, where differences in choices based on affordability led to the spatial separation of residents of different socio-economic statuses in terms of living space [27].

In the 1970s–1980s, the Marxist, structural, and Weberian schools explained urban residential segregation at the level of social systems and institutions. Brown and Moore (1970) drew on psychological concepts to study the behavior of housing location choice; based on the perspective of “utility space”, they proposed a two-stage model of “migration + search” for relocation decisions. This selection process, based on individual utility maximization, often leads residents of different socioeconomic statuses to choose different residential areas, thus creating residential segregation [1]. Pahl (1970), of the urban management school, put forward the doctrine of “city managers”, arguing that the pattern of residential segregation in a city is determined by “city managers” who control important social and market resources, including land market managers, construction market managers, capital market managers, transaction market managers, local government agency managers, and so on [28]. Schelling’s segregation model, proposed by the American economist Schelling (1971) to explain and model the process of formation of residential segregation (or residential differentiation) between different groups in a city, highlights the fact that the formation of residential segregation may not require extreme preferences or discrimination, but can be explained by simple individual behavior and decision-making processes [29]; McFadden (1973) incorporated the theory of the random utility model into the discrete choice problem of consumers and applied it to the study of the residential location choice problem, forming the classic discrete choice model methodology in the field of residential choice, which argues that the housing location choice behavior of households can be abstracted as the set of choices with different characteristics faced by consumers, and that differences in choices based on household preferences and needs make the families of different socio-economic status spatially segregated [30]. Harvey (1973), an iconic Marxist scholar, argued that the housing market is a site of social class conflict, which in turn leads to the segregation of living spaces for different classes of people [31]. Starting from the utility function and the degree of hedonic enjoyment derived from housing, Rosen (1974) proposed a theory of residential utility value based on the perspective of the characteristics of housing supply, arguing that this combined utility value determines the housing choices of the population, and then constructed the hedonic pricing model (also known as the hedonic model) [32]. Gray (1975), of the structural school, argued that the social structural system is the root cause of the individual’s residential location choice behavior and a reflection of the contradictions of capitalist society on the spatial system [33]. From a behavioral environment perspective, Färe and Lovell (1978) argued that in the housing choice process, apart from the consumer’s household characteristics, subjective factors, such as his or her previous home-buying experience, culture and values, emotions, and preference profiles, influence his or her residential choice behavior [34]. Since the 1980s, globalization, labor market restructuring, and economic liberalization have led to the polarization of residents’ incomes, increased residential segregation [35], and more complex residential segregation structures. Based on studies such as life course and residential trajectory, Kendig (1984) proposed the theory of housing career by integrating the theories of filter theory, residential mobility, and housing hierarchy, reflecting the stage characteristics of people’s residential choices. The theory suggests that housing choices are not only related to the characteristics of the housing itself but are also influenced by factors such as career changes, major events, life status brought about by the family life cycle, and residential concepts. Housing choices based on the needs and preferences of different life stages lead to the spatial separation of different social groups, and the formation of residential segregation is the result of different choices and decisions made by individuals during their housing careers [36]. Cassel and Mendelsohn (1985), who typified socio-spatial unity theory, argued that residential location choices and socio-spatial segregation have an interactive relationship; for example, the values and behavioral characteristics of a group of people living in the same community are easily influenced by other neighbors in that community; in the process, the characteristics of the community are, in turn, created and influenced by those groups [37]. Based on the correlation between socio-economic status and living space, Massey, a famous demographer in the United States, put forward the spatial assimilation theory (1985), which focuses on the integration of different ethnic groups in the social, economic, cultural and other aspects, and the resulting adjustment of living space, and argues that people use their social and economic achievements in exchange for living in a better neighborhood [38]; Aitken (1987) emphasized the influence of social background and social differences on housing search behavior [39].

Since the 1990s, with the acceleration of globalization and the deepening of urbanization, the phenomenon of residential segregation has become more com-plex and varied, prompting academics to study and expand the theory of residential segregation in greater depth. Louviere and Timmermans (1990), who disaggregated their study according to differences in residential preferences, are more representative in their line of segmentation research [40]. European geographers Klassen and Paelinck, based on the law of population mobility in the development and evolution of urbanization, divided the whole process of urbanization into three periods and four phases, putting forward the theory of urban development phases of metropolitan areas from growth to decline. Population migration is the most direct impetus for the formation of residential segregation, so it is feasible to study residential segregation based on the theory of stages of urban development. In 1996, based on the housing filters theory, O’Flaherty developed a model of housing filters, focusing on the cost of housing [41].

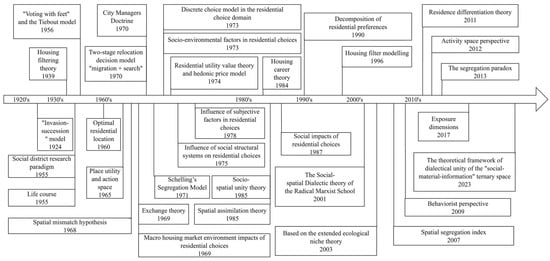

Since the 2000s, the classical theories, doctrines or models on residential differentiation have been continuously improved and developed. Wu (2001) proposed that the social–spatial dialectic theory of the radical Marxist school is the basis for the study of residential spatial differentiation in Chinese cities, arguing that “there exists a dialectical and unified interaction and interdependence between the social and the spatial [42]. Li and Zhu (2003) proposed a study of residential differentiation based on the extended ecological niche theory, which not only can better depict the connection between residential factors and the objective environment of residence, but also has more comprehensive results than the previous residential evaluation results, which only utilized the index system [43]; Feitosa (2007) and others argue that the urban segregation index is an important tool for analyzing the spatial distribution of populations and the patterns and trends of changes in urban segregation [44]. Clark (2009) combined a behaviorist perspective that focuses on the residential decisions of individual residents or families, based on family preferences, considering the role of factors such as the family life cycle, family member attributes, and housing characteristics, and focusing on the process of residential space formation [45]; the theory of residential segregation focuses more on the macro level, viewing residential segregation as a process related to racial consciousness, and argues that residential patterns do not merely reflect socio-economic achievements, but are more the result of a racialized residential market [46]. A study by Wang et al. (2012) is based on an activity space perspective, from the perspective of people’s daily activities and behavioral patterns, to a more dynamic perspective on the urban socio-spatial differentiation problem [47]. Marcinczak et al. (2013) suggested that the degree of differentiation between whole cities or different social groups is manifested in the traditional segregation index as no increase or even a decrease in the degree of segregation, the so-called segregation paradox [48]; Hennerdal et al. developed a k-nearest-neighbor-based method to measure exposure dimensions for different racial groups [49]. Huang et al. (2023) proposed a theoretical framework of dialectical unity of the “social-material-information” ternary space, arguing that urban residential space is a specific embodiment of the ternary composite space of society, material, and information at the level of the community residence. Residential differentiation under different geographical spatial scales may present varying degrees and patterns, and artificial division of continuous geographical space will have a significant impact on the analysis results [50] (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

A classical theoretical study of urban residential segregation.

Figure 1.

The early theoretical thread of residential segregation.

These early housing theories have been further expanded and improved in subsequent studies. For example, after the 1990s, housing filtering theory has been widely applied to urban planning and housing policymaking, and policymakers have begun to pay attention to methods of reducing residential segregation and improving the fairness and inclusiveness of urban living through rational residential planning and housing policies. The theory of spatial assimilation has been widely discussed in other countries and regions and has played an important role in promoting migration research and policymaking in various countries [51]. As a result of Schelling’s model, researchers have begun to focus on more types of residential preferences and influencing factors, such as income level, type of occupation, and cultural background, which can affect residents’ residential choices and the formation of residential segregation. The spatial mismatch hypothesis is another important framework for studying the phenomenon of residential segregation in recent years. The theory emphasizes the influence of factors, such as commuting time, income, and employment on residential segregation, and tries to explain why different social groups are spatially separated in terms of residential space. Some studies have found that spatial mismatch not only leads to residential segregation but also further exacerbates social inequality and stratification.

2.2. A Review of Analytical Methods for Residential Segregation

In the research methodologies of residential segregation, scholars tend to delve into the complexities and diversities of the phenomenon by examining various dimensions. Specifically, they investigate residential segregation based on factors such as immigrant background [52], income [53], gender [54], education [55], and policy [56]. On a more comprehensive level, the patterns of housing segregation are often characterized by three dimensions: intensity, segregation, and scale [57]. Gastón-Guiu et al. analyzed the residential segregation of African immigrants in Spain from the triple perspectives of age, period, and cohort [58]. Consolazio et al. explored dimensions, such as homogeneity, exposure, concentration, centralization, and clustering, using theories and methods from the residential segregation literature [59]; Buck et al. evaluated the relationship between the three dimensions of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social) and widespread residential segregation in urban areas of the United States [60].

To quantify and analyze the spatial distribution and social impacts of residential segregation, scholars have employed various index methods. These methods not only aid in understanding the complexity of residential segregation but also provide significant foundations for optimizing residential environments. Among them, segregation indices and disparity indices are widely used in residential segregation research [52,61]. For instance, Marcinczak et al. revealed the level of residential segregation within Polish cities by measuring disparity indices related to social and occupational status [62]. Boterman et al. calculated segregation indices using a multinomial logistic regression model, thereby exploring the economic and cultural dimensions of residential segregation in the Amsterdam metropolitan area [63]. Lee et al. systematically assessed the spatial segregation of the following four social groups: foreigners, low-income groups, young single-person households, and elderly single-person households, between 2010 and 2019, using disparity indices and segregation indices [64]. However, traditional segregation indices often rely on areal units in their calculations, which may lead to measurement and interpretation errors. To address this issue, Fineman introduced the shortest path isolation (SPI) index, a new individual-level segregation measurement method that accurately reflects the extent of racial isolation individuals experience in terms of distance and interpersonal contact [65]. Additionally, Katumba et al. combined spatial information theory indices with spatial exposure/isolation indices to measure racial residential segregation faced by residents in Gauteng Province, South Africa, across multiple spatial scales [66]. Furthermore, as traditional segregation indices primarily focus on two groups (Blacks and Whites) [67,68], they are increasingly insufficient in describing the complex spatial segregation and integration patterns in a diversified society. In response, multi-group segregation indices have emerged, such as the one pioneered by Song et al., who analyzed the differences in the degree and evolution of residential differentiation under different city, scale, and segregation indices. They applied a segregation decomposition method to calculate the contributions of spatial structure components and cluster attribute components to the differences in residential segregation between Nanjing and Hangzhou [69]. Additionally, scholars have also used other indices, such as similarity indices and delta indices, to measure the degree of residential segregation [70].

By utilizing index methods combined with various analytical approaches, scholars have gained a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of residential segregation phenomena. Martori innovatively applied multi-level analysis of disparity indices to Spanish cities, providing a new perspective for understanding residential segregation within cities [71]. Carvalho utilized Spearman’s rank correlation test and a combination of socio-urban infrastructure variables, along with hierarchical cluster analysis and ‘spatial ellipse’ analysis, to assess the segregation levels of cities and slums. He also compared the residential segregation levels of cities and slums nationwide using Moran’s I index [72]. Additionally, Lu et al. employed a generalized propensity score matching method to quantify the actual impact of residential segregation on the provision of public services in both the public and private sectors, providing a scientific basis for policy-making [14]. Regarding the study of residential differentiation among migrant populations, Sun et al. took Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen as research objects and combined global spatial autocorrelation, location entropy, factor analysis, multiple linear regression, geographically weighted regression, and geographical detectors to deeply explore the influencing mechanisms of migrant populations’ residential differentiation [73]. In the study of residential segregation, qualitative analysis methods also play an important role. Dove-Medows explored issues of racial segregation and community racial distribution among pregnant Black women through qualitative interviews [74]. Asibey et al. comprehensively investigated the residential segregation of ethnic minorities by combining household surveys, focus group discussions, secondary data, and institutional interviews [75].

In the study of residential segregation, the theoretical model proposed by Schelling has become a classic paradigm in the field of social sciences and is widely used to reveal the formation mechanism of residential spatial segregation [29]. With its excellent explanatory power, the Schelling model enjoys a high citation rate in the urban research literature and is one of the most influential models in this field. However, despite its widespread applicability, the Schelling model is also considered oversimplified and unable to fully simulate the mixed, coexisting patterns of segregation and integration that exist in cities [76,77]. Kusumah expanded the agent-based Schelling model by combining random discrete utility choice methods to simulate residents’ relocation decisions and study relocation phenomena in residential segregation [78]. Furthermore, the SimSeg model developed by Fossett et al. is an extension of the Schelling model that uses agent-based methods to explore the potential of theories of residential segregation in urban areas [79]. Li et al. proposed an agent-based sorting and repeated game model to quantify segregation patterns [53]. Song et al. established a multi-scalar segregation profile and comparison model based on different geographic scales and residential types to further investigate the phenomenon of residential segregation [69]. Harting et al. constructed a modeling framework that includes population, rental markets, and household utility to explore the economic and diversity-related factors of residential segregation [80].

Traditionally, the data relied on in residential segregation studies mainly comes from various census data [4,55,81], official records, and geocoded data [63,82]. However, with the rise of multi-source data, the application of multi-source data in residential segregation research has become increasingly widespread. Cao et al. combined multiple data sources, such as housing price data, planning permit data, and points of interest (POIs), and employed stepwise regression models and t-tests to explore the impact of urban renewal on local and regional residential segregation in Shenzhen [83] As technology continues to advance, new trends are emerging in data selection and application. Using public transportation smart card data, researchers can measure social segregation based on activities among different groups, providing a new perspective on the degree of urban segregation [84]. The progress of geographic data, such as mobile signaling data (MSD), has provided valuable opportunities to gain insights into residential segregation from a spatiotemporal context at the level of transportation analysis zones (TAZ) [85]. In addition, Hedman et al. used mobile phone data to track daily travel patterns related to residential segregation [86], enabling researchers to observe the specific impact of residential segregation on residents’ daily lives in a more intuitive manner.

3. Main Characteristics of Urban Residential Segregation

To delve into the main characteristics of urban residential segregation, this study adopted the Web of Science (WOS) Core Collection database as the source of information, particularly focusing on relevant studies published after January 2020. In the screening process, we precisely used the keyword “residential segregation (and its synonyms)” as the primary keyword and combined it with “characteristics” as the secondary keyword to ensure the pertinence and accuracy of the search. Through systematic retrieval, we comprehensively collected the kinds of studies related to the characteristics of urban residential segregation, covering two dimensions: population types and spatial characteristics. Then, we conducted a detailed analysis and screening of this literature, aiming to select high-quality ones that can directly reflect the main characteristics of urban residential segregation. In the screening process, we classified the search results according to the research objectives and strictly excluded articles that did not meet the established standards to ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of the final analysis. Finally, we successfully selected high-quality studies, which provided a solid foundation for us to clearly describe the main characteristics of urban residential segregation.

3.1. Dimensions of Population Type in Residential Segregation

In terms of the population type division dimension of residential segregation, the current research has been conducted in terms of racial status, immigrant background, socioeconomic conditions, and age status. Racial residential segregation between Whites and Blacks is a persistent feature of residential segregation in U.S. cities [67,87,88]. Additionally, the segregation of the Black community is more pronounced than in the UK [89]. Caste segregation is the most typical feature of residential segregation in India [90]. In the context of globalization, residential segregation between immigrants and native residents has become a current research hotspot and frontier. For example, the phenomenon of immigrant residential segregation in British cities is particularly significant [91]. African immigrants have increased the spatial segregation of settlements in six major Spanish cities [58]. Dutch cities, for their part, have experienced diverse residential segregation due to the diversity of immigrants [57]. In addition, foreign immigrants have shaped a unique pattern of residential segregation in the urban periphery of the Italian city of Milan [59]. Transnational migrants (especially professionals from multinational corporations) have triggered diverse spatial patterns of living in Tokyo [92]. In Seoul, South Korea, immigrants from different income levels shape the city’s pattern of residential segregation [12]. Immigration status plays a role in determining residential segregation even beyond the occupational factor [93]. However, in most cases, migrants with higher levels of education have access to better housing and living conditions [94].

Differences in socioeconomic status (including income, property, education occupation, etc.) are one of the major causes of residential segregation. When significant differences exist in the socioeconomic status between different social groups, they tend to be spatially segregated [95]. The visible spatial segregation of the high-income population (living in city centers) from the low-income population is increasing in the current global cities (New York, London, Tokyo) [96]. Notably, the phenomenon also occurs in some European cities [97]. For example, graduates of the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands are more likely to be segregated than high-income people [63]. Residential segregation based on educational and occupational groups has generally increased in Australia’s core cities [4]. Age differences are driving socio-spatial polarization, especially in aging societies [11]. As more and more communities become extremely polarized by age and generational differences, age differences in the UK lead to unequal housing affordability, which in turn exacerbates residential polarization [10]. Residential segregation between the young and older adults continues to rise in the United States [98]. Age segregation in Hong Kong is expected to intensify as the population ages and as young people move to the suburbs [99]. Migrant and rural populations experience higher levels of residential segregation than urban residents [100,101,102]. In Longgang City, China, although both the working and residential populations exhibit high levels of segregation, the working population is relatively less segregated [103], suggesting that additional housing options and better living conditions should be provided for the mobile and rural populations.

3.2. Spatial Characteristics of Residential Segregation

Residential segregation is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon with different contexts and intrinsic mechanisms of residential segregation exhibiting their own unique characteristics [104]. A general trend toward residential segregation emerges in cities worldwide, characterized by a gradual shift in high-income populations toward city centers or attractive waterfront areas, whereas low-income populations are moving to the urban fringe (e.g., London) [105]. This pattern of migration has led to a marked spatial segregation of settlements between urban centers and peripheral areas, with high-income populations clustered in city centers and low-income populations mostly located on the urban fringes. In addition, in some low-income countries, high-income populations not only choose to live in the city center but may also tend to construct their own living space in enclaves or gated communities outside the city center, which often contrasts with low-income neighborhoods, creating a kind of privatized living space that is segregated from low-income residents [96]. For example, in Lima, Peru, a 10 km long wall in the eastern region separates wealthy neighborhoods (e.g., La Molina and Santiago de Surco) from poorer neighborhoods (e.g., San Juan de Miraflores and Villa María del Triunfo) [106]; it is a clear sign of economic and social segregation, highlighting extreme forms of residential differentiation and directly reflecting the socio-economic state in the spatial layout of the city.

People with different incomes and occupations show significant differentiations in their choice of living space; in Hangzhou, for example, the city’s elite still tend to live in the central city surrounding the CBD [107]. In Nanjing, on the other hand, residents with higher education and occupational statuses are predominantly clustered in the city center [108], and this difference in residential choices further exacerbates the spatial segregation of residences within the city. In terms of the degree of residential segregation within the city, peri-urban (low-density) areas tend to be the most obviously segregated areas in terms of residential space [109]; this phenomenon has occurred with the expansion of the city scale and out-migration of the population; peri-urban areas have gradually become the main gathering places of low-income groups, forming a very different residential space characteristic from the city center. Especially in large cities, the phenomenon of residential segregation is more prominent due to the complexity of the economic structure and the diversity of social classes. Several case studies (e.g., the Netherlands, Poland, etc.) have shown a highly positive correlation between city size and the degree of residential segregation [57,62]; this suggests that living space segregation is generally higher in large cities than in small- and medium-sized cities [110]. Immigration is one of the key topics in the field of residential segregation research. At the international level, foreign migrants in specific areas of the city (peripheral zones) have shaped the pattern of residential segregation in the city of Milan; to illustrate, the Chinese are clustered in several peripheral zones to the north of the historic center, and Egyptians are dispersed all over the city [59]. Similarly, immigrants from low- and lower-middle-income and lower-income economies are more likely to reside in the rural and industrial zones outside of the Seoul metropolitan area [12]. In some of China’s megacities, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, immigrants are disproportionately located in the suburbs, mainly because of the large number of manufacturing firms and employment opportunities in the suburbs, which have attracted a large concentration of new immigrants [15,111,112]. In Shanghai, the most severe segregation occurs in the suburbs [113], where rural migrants tend to congregate spatially in peri-urban areas far away from the local population, while the migrant population prefers to live in the peripheral areas of the central city [114]. However, unlike Shanghai, Guangzhou’s migrants are gradually moving to the suburbs due to the substantial increase in housing prices in the city center [15]. Overall, China’s migrant population usually lives in the peripheral areas of cities [8]. However, migrants are less likely to live on the fringes of the city than in the center of Shijiazhuang [93]. In Hong Kong, migrants from South or Southeast Asia are mainly concentrated in densely populated areas in the northern part of the New Territories and Kowloon, while migrants from developed countries tend to live on Hong Kong Island and certain parts of Lantau Island [115]. Age structure is an important factor in shaping the spatial characteristics of urban residential segregation, with the residential needs and lifestyles of older persons changing as they age, often causing them to prefer to live in familiar neighborhoods or urban residential areas. By contrast, younger people are in search of new lifestyles and living environments, choosing to migrate to the outskirts of the city or to new public and private housing units. Changes in age structure may affect the character of neighborhoods and urban residential patterns. While older persons in Hong Kong are concentrated in urban residential areas, younger persons will move into new public and private housing units in sprawling urban or suburban areas and become increasingly segregated from older persons [99]. By contrast, Berlin has a concentration of older people in peripheral areas, spatially surrounding other groups in the city [116]. The household registration system has had a profound impact on the spatial characteristics of residential segregation in China. Owing to the restrictions of the household registration system, migrants often have difficulty accessing low-cost public housing services and other social benefits in cities [117]. In addition, most rural-urban migrants congregate in urban villages or poor urban neighborhoods [111] with institutional segregation exacerbating socio-economic inequalities and spatial segregation of residence within cities. In many countries, especially in multiracial societies, race is often an important factor influencing the spatial characteristics of residential segregation, such as in Atlanta, USA, and the majority of Blacks living in the suburbs [118]. Minority populations in U.S. cities live in highly walkable neighborhoods more often than non-minority populations [119]. Apart from horizontal segregation, vertical segregation at the micro scale also exists in cities. studies in cities such as Athens and Budapest have also found that higher-status groups tend to occupy the upper spaces of apartments, whereas people from lower classes are more concentrated in the lower spaces; this segregation continues to exacerbate the sense of social inequality and divisions within neighborhoods [120] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spatial characteristics of urban residential segregation.

4. Key Driving Mechanisms of Urban Residential Segregation

Relying on the Web of Science (WOS) Core Collection database, this study conducted a thorough investigation into the core driving mechanisms of urban residential segregation, particularly focusing on the latest research findings published after January 2020. During the literature search phase, we carefully selected “residential segregation (and related terms)” as the primary keyword and combined it with “driving mechanisms” as the secondary keyword to ensure the precision and relevance of the search results. Through systematic literature retrieval and screening, we successfully collected a large number of research papers closely related to the driving mechanisms of urban residential segregation.

Subsequently, we conducted an in-depth analysis and scrutiny of this literature, aiming to identify the core elements and dynamics that influence urban residential segregation. To ensure the rigor and validity of the study, we finely categorized the selected kinds of literature based on the research objectives and strictly excluded articles that did not meet the established criteria.

Finally, we carefully selected several high-quality and highly relevant studies in the literature as the basic data for this study. These studies not only provide us with a comprehensive description of the driving mechanisms of urban residential segregation but also offer rich data support for us to deeply understand the complex mechanisms behind it. Based on the in-depth analysis of this literature, we hope to provide valuable references and insights for addressing the issue of urban residential segregation.

4.1. Structural Factor Perspectives

From the perspective of structural factors, the main driving mechanisms of current urban residential segregation are multidimensional and complex. In specific cities, such as Toronto, Canada, discrimination in the labor market and the resulting disparities in economic income opportunities have been a major driver of residential segregation for colored people [121], which is not only reflected in employment opportunities but also leaves a deep imprint on residential choices. In addition, the process of gentrification, the upscale nature of housing development, and exclusionary housing markets are important reasons for the persistence or exacerbation of residential segregation in some cities in the United States of America [122,123,124]. Green gentrification exacerbates residential segregation and social polarization and hinders community integration [125]. The predominance of low-density residential neighborhoods and the implementation of their zoning regulations have exacerbated the housing affordability divide and reinforced the degree of residential segregation [126], a phenomenon that is prevalent globally and has been validated in specific cities, such as Nanjing, where house prices have become a key factor in shaping the pattern of residential segregation [69]. In London, due to high housing prices, low-income groups have been pushed into less accessible areas of the outer city, which intensifies the residential segregation between urban centers and peripheral areas [105]. Racial consciousness is a dominant determinant of residential segregation [53]. Differences in access to homeownership among different racial groups in different regions contribute to residential segregation at the city level [127]. Moreover, narrowing the ethnic income gap may instead exacerbate residential segregation, as such processes may be accompanied by more pronounced solidification of social class [80]. Policy orientation and management systems have a far-reaching impact on residential segregation. For example, neoliberal policies have increased residential segregation (especially ethnic segregation) in Chile’s major cities [128]. Although urbanization in developing countries may be driven by different social and political processes from those in Western countries, it is accompanied by residential segregation that is equally as serious. [129]. The combination of China’s school district system and housing marketization not only aggravates urban residential segregation and inequality but also deepens social isolation within the unit [130]. The impact of housing policy on residential segregation is particularly significant. The Liberal housing policy is one of the main drivers of residential segregation in the Marseille metropolitan area of France [131]. Hong Kong’s housing policies and aging-in-place have led to the spatial segregation of older and younger people [99]. More public housing construction has led to more pronounced residential segregation in Poland [66] and France [132]. Furthermore, large-scale land zoning and public housing policies for immigrants in the Pearl River Delta region can lead to severe residential segregation [9]. As a unique population management system in China, the household registration system strictly limits people’s freedom of migration and intensifies the social spatial segregation within cities [133]. Policy decisions and urban planning have a profound impact on settlement patterns and community structure, such as the strategy of building highways in the United States, which exacerbates the fragmentation and isolation of communities by cutting through low-income and minority neighborhoods [134]. State–market participation and socialist identity-driven urban planning are key reasons for extreme residential segregation in six key development zones in the Pearl River Delta [13].

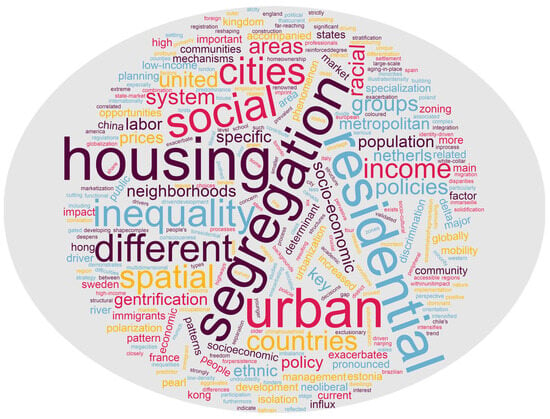

The trend toward labor specialization in globally renowned megacities has led to the polarization of occupational structures and socioeconomic inequalities, which has in turn led to increased spatial segregation of dwellings [96]. Socio-economic inequality is a pervasive factor in urban residential segregation, which is not only a predictor of racial residential segregation in Munich [52] but is also closely related to the residential segregation patterns of different minorities in Hong Kong [115]. A survey of 40 Brazilian metropolitan areas demonstrates a positive correlation between residential segregation and socio-economic status [68]. Income inequality within counties of metropolitan areas in the United States exacerbates racial residential segregation [135]. This inequality exists not only within countries but also internationally; residential segregation is strongly correlated with income inequality in countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Estonia; to illustrate, the intensity of residential segregation and separation of all cities in the Netherlands is related to income inequality and the share of interest groups in the urban population [57]. High-income inequality and segregation also lead to difficulties in social spatial mobility in four European countries, including Sweden, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (England and Wales), and Estonia, with different socioeconomic groups settling in different types of neighborhoods [136]. Residential mobility is a crucial determinant in reshaping urban social space and promoting spatial differentiation and segregation within cities [108]. Research has shown that residential segregation is associated with a smaller immigrant population and poor socio-economic conditions in 16 functional urban areas in Italy and Spain [137]. In the context of globalization, the influx of immigrants (especially from different socio-cultural and ethnic backgrounds) is undoubtedly an important driver of current academic concern [12,71,75,138]. The influx of foreign white-collar professionals in Bahrain has driven the development of gated communities, exacerbating residential segregation [125,139]. Meanwhile, suburbanization, as a specific stage or phenomenon in the process of urbanization, has intensified social stratification and spatial imbalance in China [140]. These studies indicate that the current mechanisms of residential segregation primarily stem from labor market specialization and its discrimination, high housing prices and housing shortage, neoliberal policies, economic restructuring, gentrification, and so on, which interact to shape the complex pattern of urban residential segregation. We drew a keyword map (Figure 2) and organized it into a table (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Keyword map of structural factors of residential segregation.

Table 3.

Driving mechanism of residential segregation—from structural factor perspectives.

4.2. Individual Selection Factors Perspectives

Individual choice is one of the key driving mechanisms shaping urban residential segregation. Based on a complex interplay of factors such as personal preferences, social networks, cultural affinity, or a sense of belonging to a specific community, people tend to choose to live in communities with similar backgrounds (e.g., ethnicity, culture, or economic status) when selecting a residence. Homogeneity is an important consideration for both local and non-Western immigrant families in their housing choices [141]. The lack of integration among different ethnic groups at the household level further exacerbates the trend of residential segregation [142]. Age, as a key factor in residence choice, is not only closely related to housing affordability but also exerts differentiated impacts on residential segregation through its cyclical social effects. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the strong correlation between age and housing affordability is particularly prominent in affluent areas, highlighting the complex interplay between socioeconomic status and age structure [10]. Age differences have significant impacts on the level of segregation experienced by African immigrants in Spain, and the trend of segregation becomes pronounced as age increases [58]. In the United States, the age differentiation characteristic of urban spaces, especially in affluent areas, where high housing prices and clear socioeconomic and age boundaries coexist, jointly exacerbates the spatial polarization at the intersection of wealth and age [10]. Educational level also plays a crucial role in residential choice [63]. Education composition is the main driving factor of income inequality before tax on residential segregation [143]. Those with high educational levels tend to choose sites freely in various areas of the city, promoting the gentrification of the originally homogeneous low-class areas [144]. By contrast, the poorly educated face more residential segregation due to economic constraints, accepting poorer housing conditions, or migrating to affordable areas, further exacerbating the suburbanization of poverty [145]. The inequality in school choice further reinforces income-based residential segregation in cities such as those in Germany [146]. Additionally, school catchment areas have a significant impact on high-income Finnish-dominated families [147]. Convenience facilities, as another consideration in residential choice, are closely related to residential mobility [6]. Studies have found that groups with higher socio-economic status tend to prefer neighborhoods with well-developed infrastructures [5]. The pursuit of environmental quality also affects immigrants’ decisions to choose ethnic Chinese neighborhoods [6]. Research in Hangzhou has found that employment, schooling, and neighborhood accessibility have significant effects on residential differentiation [107]. Ethnicity and nationality play an important role in partner choice and residence decisions, which exacerbate the segregation and division among communities, leading to a more entrenched urban social structure. In Sweden, the tendency to partner with single people who live nearby and have the same race and birthplace has aggravated segregation [148]. Cultural characteristics (e.g., language and religion) are probably the core elements in the choice of group identification and residence [149]. To integrate into the mainstream, minorities may choose to live in a neighborhood with fewer speakers of their language [150]. However, research in Sydney reveals significant segregation among different linguistic groups within communities [149]. The impact of economic status on residential segregation is particularly significant. In Shanghai, high-income groups have local household registrations, where income levels and family size enhance their tendency to avoid living next to neighbors with different economic or household registration backgrounds [151]. Relatively high-income earners are more inclined to relocate when individuals perceive a mismatch between their household income and their neighborhood. This tendency also exists among groups with a higher socio-economic status, whereas those with a lower socio-economic status are less likely to consider relocating even if they feel their status is lower [152]. Furthermore, the individuals’ life course, family cycle, and ownership type are closely linked to housing choices. Particularly in urban centers, the proportion of residential choices is closely related to urban population dynamics, changes in family structure, population density, specialization in tourism activities, and social inequality [9]. In summary, understanding the multidimensional aspects of individual choice is critical to revealing and responding to the phenomenon of urban residential segregation. We drew a keyword map (Figure 3) and organized it into a table (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Keyword map of individual selection factors of residential segregation.

Table 4.

Driving mechanism of residential segregation—From individual selection factors perspective.

5. Effects or Consequences of Urban Residential Segregation

This study, based on the Web of Science (WOS) Core Collection database, conducted an in-depth exploration of the latest research findings published after January 2020, focusing primarily on the effects or consequences of urban residential segregation. During the literature search process, we precisely selected “residential segregation (and related terms)” as the primary keyword and combined it with keywords such as “effects” and “consequences” as secondary screening criteria to ensure the precision and relevance of the search results.

After systematic literature retrieval and rigorous screening, we successfully collected a large number of research papers closely related to the effects or consequences of urban residential segregation covering two significant dimensions: resource inequality and social impact. Subsequently, we conducted an in-depth and careful analysis of these papers, aiming to uncover the core elements and driving forces that influence urban residential segregation.

To ensure the rigor and validity of the study, we refined the selected literature based on the research objectives and strictly excluded articles that did not meet the established criteria. Ultimately, we carefully curated many high-quality, highly relevant documents as the solid foundation data for this research. These documents will provide strong support for us to gain a deeper understanding of the effects or consequences of urban residential segregation.

5.1. Residential Segregation and Resource Inequality

Residential segregation within cities reflects not only the differences in settlement patterns but also the deeper imbalances in social equity, economic development, and community well-being; additionally, residential segregation has important implications for inequality [153]. Research on the effects of segregation of urban living spaces is predominantly negative. Research has shown that severe residential segregation within cities can lead to inequalities between advantaged and disadvantaged groups in terms of educational resources [154], public resources [69], employment opportunities [54], environmental quality [155], health levels [156,157], access to healthy food options [158], availability of infrastructure [72], social security [7], social status and living conditions [159], and other inequalities. This situation further leads to a spatial mismatch of resources [69], exacerbating social differentiation and thus affecting the spatial equity and sustainable development of cities.

Residential segregation leads to the unequal distribution of educational resources. Typically, schools located in higher-income neighborhoods tend to have access to richer educational resources, whereas schools in peripheral areas are relatively poorly resourced, an uneven distribution of resources that leads directly to inequities in education. Residential segregation not only determines where students live but also has a profound impact on their access to education and employment opportunities [160]. Studies have shown the significant geographical imbalances in the population with tertiary education, particularly in peri-urban and other marginalized areas [113]. In regions with a high level of urbanization, families often face a wider range of choices when selecting schools; however, such choices are often constrained by the socio-economic context of their place of residence [161]. Neighborhood segregation and poverty lead directly to ethnic isolation and the concentration of poverty in schools, resulting in significant inequalities in access to education [162]. In geographically segregated communities, non-Hispanic Black groups face dual inequalities in educational and economic opportunities due to physical segregation [163]. The impact of segregation on education is particularly significant for students with immigrant backgrounds. In Sweden, pupils from immigrant backgrounds are often associated with the so-called “segregated neighborhoods” and underperforming suburban schools. Despite the possible formal value they receive and inclusion, they are often subtly excluded socially by their peers; the latter results in lower chances of integration [164]. Such exclusion not only affects their academic performance but can also have long-term consequences for their mental health and social adjustment. They often have difficulty accessing high-quality educational resources, which not only limits their personal development but also exacerbates social inequalities. In China, the uneven distribution of quality education resources has become a prominent issue, which has not only led to the capitalization of school district housing premiums but also exacerbated inner-city residential segregation, making housing a visible symbol of class differentiation [130]. Advantageous families in cities contribute to the reproduction of class differentiation by owning housing near quality educational resources, allowing inequalities in resources and development opportunities to be transmitted between generations [16].

Differences in living space can also lead to problems such as public resource deprivation and class identity solidification [16]. The context of China’s property market somewhat enables residential segregation to reflect socio-economic characteristics by influencing house prices [165]. Middle- and high-income families can reside in prime residential areas with convenient transportation and complete facilities, whereas low-income families are often marginalized in communities with low accessibility and scarce resources [166]. In areas with high levels of racial or ethnic segregation, communities in these areas often lack affordable and safe access to recreation, work, education, and healthcare for sporting activities due to widespread transport vulnerability [167]. Communities with high levels of segregation often do not enjoy a better quality of life and have limited access to basic services such as schools, hospitals, or transportation.

While evidence proves that in some cases, segregation can benefit migrants by encouraging social networks that provide employment opportunities [4], several potential disadvantages exist. Segregation has adverse spatial mismatch effects on labor market participation rates [54]. Regardless of the floating population or the registered population, people living in isolated areas often have poor job opportunities [114], and residential segregation has a significant negative impact on employment stability [168]. Apartheid areas tend to be more disadvantaged in terms of a range of neighborhood-level situational attributes, including higher unemployment rates [169]. The rural migrant workers, living in the suburbs, face a high risk of segregation from the local population, both in the neighborhood and workplace; in particular, migrant workers working in the manufacturing sector in the suburbs are more likely to be in a closed working environment, where coming into contact with and getting to know other social groups are difficult for them, thus exacerbating their social segregation [170].

In terms of the environment, residential segregation has a significant impact on the health status of residents in low-income residential neighborhoods. Studies have found that these neighborhoods have significantly lower green space accessibility [171], meaning that residents lack sufficient green spaces for recreation and exercise, which may negatively impact their physical and mental health. Socioeconomically disadvantaged residents tend to live in neighborhoods with poorer environmental quality, and these areas typically have higher PM2.5 concentrations and poorly built environments [172]. This environmental exposure directly increases their health risks for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, further exacerbating health inequalities. Residential segregation also affects the availability of healthy food options to residents. In more segregated neighborhoods, relatively fewer healthy food outlets exist, and residents travel longer distances to these outlets [173]; have a poorer perception of the food environment (low food environment perception); and consume fewer fruits, vegetables, fish, and so on [174]. The unequal distribution of healthcare resources is also influenced by residential segregation. In areas with high levels of residential income segregation, hospitals often lack specific diagnostic or therapeutic technologies [175], which renders access to high-quality healthcare difficult for locals when facing serious illnesses. In China, owing to the uneven distribution of public hospitals and other healthcare resources, communities on the outskirts of cities with abundant healthcare resources are at a relatively lower risk of having residents with health conditions than other communities [172].

5.2. Residential Segregation and Social Impact

Residential segregation is associated with health inequalities, with higher levels of racial residential segregation being associated with poorer health [176]. It exacerbates cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality [177], and the prevalence of hypertension [170], and the negative impact of residential segregation on virological suppression is greater in counties with lower levels of community health resources [178]. As a result of persistent residential segregation in society, Black citizens are often forced to live in areas adjacent to major roads or motorways and are also disproportionately exposed to carbon monoxide emissions from car exhausts [179]. Residential racial segregation is negatively correlated with the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among urban Blacks, suggesting that racial segregation plays a role in contributing to health inequalities in Black communities [180]. Long-term residence in segregated communities may exacerbate the degree of brain aging [181], indirectly contributing to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD) [182]. Older people living in segregated neighborhoods are vulnerable to loneliness and health threats at both the physical and psychological levels in poor housing conditions [183]. The scarcity of entertainment venues in highly segregated areas increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases [167] and obesity among the youth [184]. Residential segregation leads to inequalities in anxiety related to neighborhood violence and obstacles, and policies that reinforce segregation may impact neighborhood mechanisms (unequal socioeconomic status, overall discrimination, and low social cohesion) [185].

Residential segregation significantly increases the risk of theft and violence [7]. Low-income neighborhoods are excluded from the urban system and are located in areas with low land values and are far from the core, leading to social problems such as crime and drug abuse [186]. Research has shown that in racially segregated residential areas, the risk of gun-related deaths is 1.3 times higher than in areas with lower levels of segregation [187]. This phenomenon is particularly evident in Brazilian cities, where a clear positive correlation exists between racial segregation and homicide rates. The spatial degradation and lack of physical, economic, and social infrastructure resulting from residential segregation further exacerbate the risks of discrimination and interpersonal violence faced by residents in poverty-stricken areas [188]. In the United States, Black males are likely to be victims of violence and exclusion due to residential segregation; even within the same county, Black and White residents may face different policing support, security infrastructure, and unequal distribution of public and private investment in their communities [189].

Residential segregation has a profound impact on social inequality, which is reflected in three ways. First, residential segregation exacerbates gender inequality in less-educated households, exposing females in these households to additional barriers to education and career development. Second, as women with higher educational attainment increasingly participate in the labor market, residential segregation further amplifies the socioeconomic inequality between low-income and affluent families. Finally, residential segregation deepens the geographic separation between marginalized and non-marginalized households, leading to increased difficulties in accessing resources and services for these households [54]. For example, segregation can prevent migrants from integrating into the city and limit opportunities for social mobility [190]. In cities such as Shanghai, individuals have become increasingly socio-economically differentiated as upmarket neighborhoods and migrant communities have formed [94]. This differentiation not only exacerbates social inequality but also makes it difficult for migrants to cross social classes and achieve upward mobility. Residential segregation not only exacerbates material inequalities between populations but can also undermine the foundations of trust needed to build and maintain the public good, thus weakening the ability to overcome collective action problems [160]. In Korea, poor residents in permanent rental flats have weakened social networks due to residential segregation, external stigmatization, and the existence of slums, further exacerbating their social isolation [191].

Residential segregation is a multidimensional social problem that not only reduces the quality of life of residents but also exacerbates social inequalities. In a social environment where segregation is prevalent in communities, schools, and workplaces, the likelihood of people establishing deep personal friendships with those from different backgrounds will significantly decrease [132]. Social integration has the following three dimensions: willingness to settle permanently, cultural integration, and psychological integration [192]. Notably, it can encourage migrants living in formal communities to work hard, have a strong willingness to settle, and actively integrate into mainstream society by building localized social capital [193], which is essential to alleviate the negative impacts of residential segregation. Joint efforts from the government, social organizations, and residents are necessary for taking effective measures to reduce residential segregation, optimize resource allocation, and enhance community well-being to promote social equity and sustainable development.

6. Research Trends and Prospects

In terms of research trends, the study of residential segregation in cities worldwide has been receiving increasing attention owing to the acceleration of the urbanization process. In addition, the increase in population migration has prominently increased the problem of the differentiation and segregation of urban residential space. By reviewing the above research progress, the following shifts have occurred in residential segregation research. First, the focus has shifted from the physical environment to the social environment. Second, residential segregation research is likely to pay extra attention to the impacts of ethnicity, income, and socio-economic status and to explore how to promote racial and economic integration through policy interventions. Third, it pays extra attention to the impacts of macro-contextual factors such as the system and the market. Fourth, it pays extra attention to the targeting of specific populations in segmented studies. In addition, based on China’s unique household registration system, the issue of spatial segregation of migrant and rural populations has received increasing attention. “Social environment”, “soft factors”, “system”, “population segmentation research”, and so on are hot keywords in the current research on housing location choice. Certainly, it is also manifested in the following shortcomings. First, the coverage in population segmentation remains incomplete. Second, although the influence of the social environment has begun to receive extra attention from researchers, the study of the driving mechanism of social space on urban residential segregation persistently needs further supplementation and improvement. Drawing on the research trend of intra-city housing location choice, future research can be further developed from social factors represented by social space, time process factors represented by housing career, and lifestyle factors represented by life tendency and psychological characteristics, paying extra attention to the research perspectives of society, time, and lifestyle to further enrich the research outcomes in this field.

The study of urban residential segregation is moving toward a new stage of diversification and depth, and the global study of urban residential segregation will continue to develop in depth. Future research urgently needs to delve deeper into the core roles and underlying mechanisms of different population types in residential segregation without overlooking the intricate interplay and influence of various factors to propose comprehensive and effective solutions. In addition, vertical spatial segregation, which reflects socio-economic differences and unequal distribution of resources, will be one of the foci of future research as another important dimension of residential segregation. With the rapid development of digital technology, researchers can increasingly utilize big data, GIS, and other technological means to study residential segregation. These technologies not only provide more comprehensive and accurate data support but also reveal the dynamic changes of residential segregation in terms of space and time. To promote social equity and sustainable development, the government, social organizations, and residents must work hand in hand to take practical and effective measures to reduce residential segregation, which includes optimizing the allocation of resources to ensure that all residents have equal access to quality public services, such as education, healthcare, and employment. A need also arises to strengthen community building, enhance community well-being, and create a more inclusive and harmonious social environment.

7. Conclusions

After extensive research and analysis of urban residential segregation, we developed the following main conclusions, which are intended to provide us with new perspectives and strategies for understanding and responding to the urban residential phenomenon in depth.

First, in terms of the evolution of the theoretical lineage, the study of urban residential segregation has undergone a development process from simple to complex and from single to multiple since it was first revealed in 1872. The trajectory of this theoretical development not only reflects the deepening and expansion of academic research but also the complexity and multidimensionality of the urban residential segregation phenomenon itself. With the increase in disciplinary crossover and in-depth research, future research on residential segregation will be more comprehensive, systematic, and innovative, providing us with more comprehensive and accurate theoretical support.

Second, from a methodological perspective, the study of residential segregation has achieved a leap from socioeconomic factors to spatial distribution, transitioning from a single viewpoint to a comprehensive and all-round consideration. Quantitative tools such as segregation indices and disparity indices provide robust support for in-depth research into the phenomenon of residential segregation. In terms of analyzing these indices, methods like regression analysis and dynamic cluster analysis not only enable the identification of key factors influencing residential segregation and their mechanisms but also help to reveal the spatial distribution and dynamic changes. The establishment of research models such as the Schelling model and its extensions contributes to understanding the dynamic mechanisms and trends of residential segregation. Meanwhile, qualitative research methods, including interviews and observations, delve deeply into the social and cultural factors behind residential segregation. With the advancement of data technology, big data and real-time data provide a new perspective for the study of residential segregation. These methods collectively constitute a solid foundation for research on residential segregation.