Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of a New Type of Prefabricated Steel–Concrete-Composite Energy-Dissipation Shear-Wall System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Plan Design

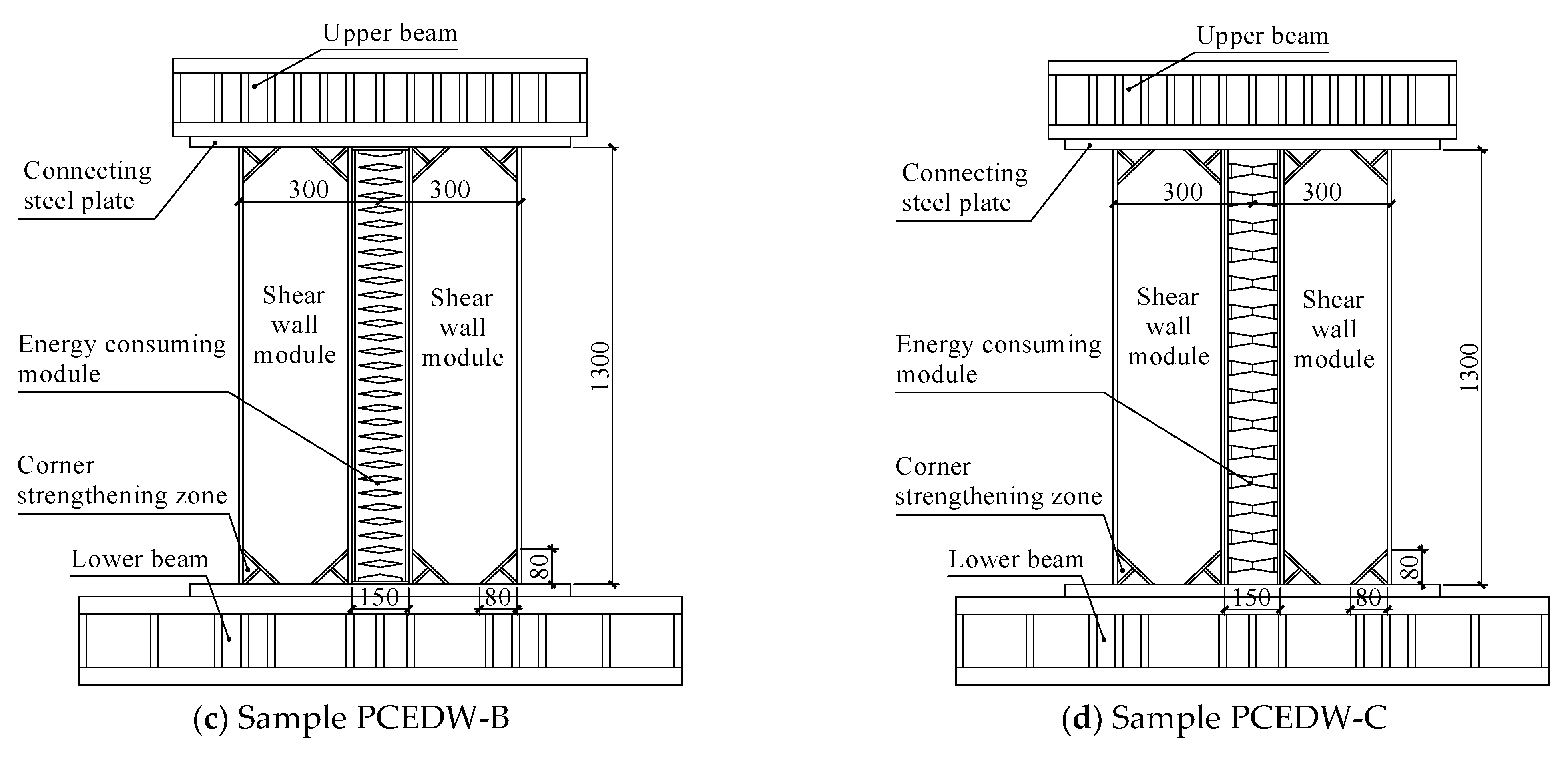

2.1. Sample Design

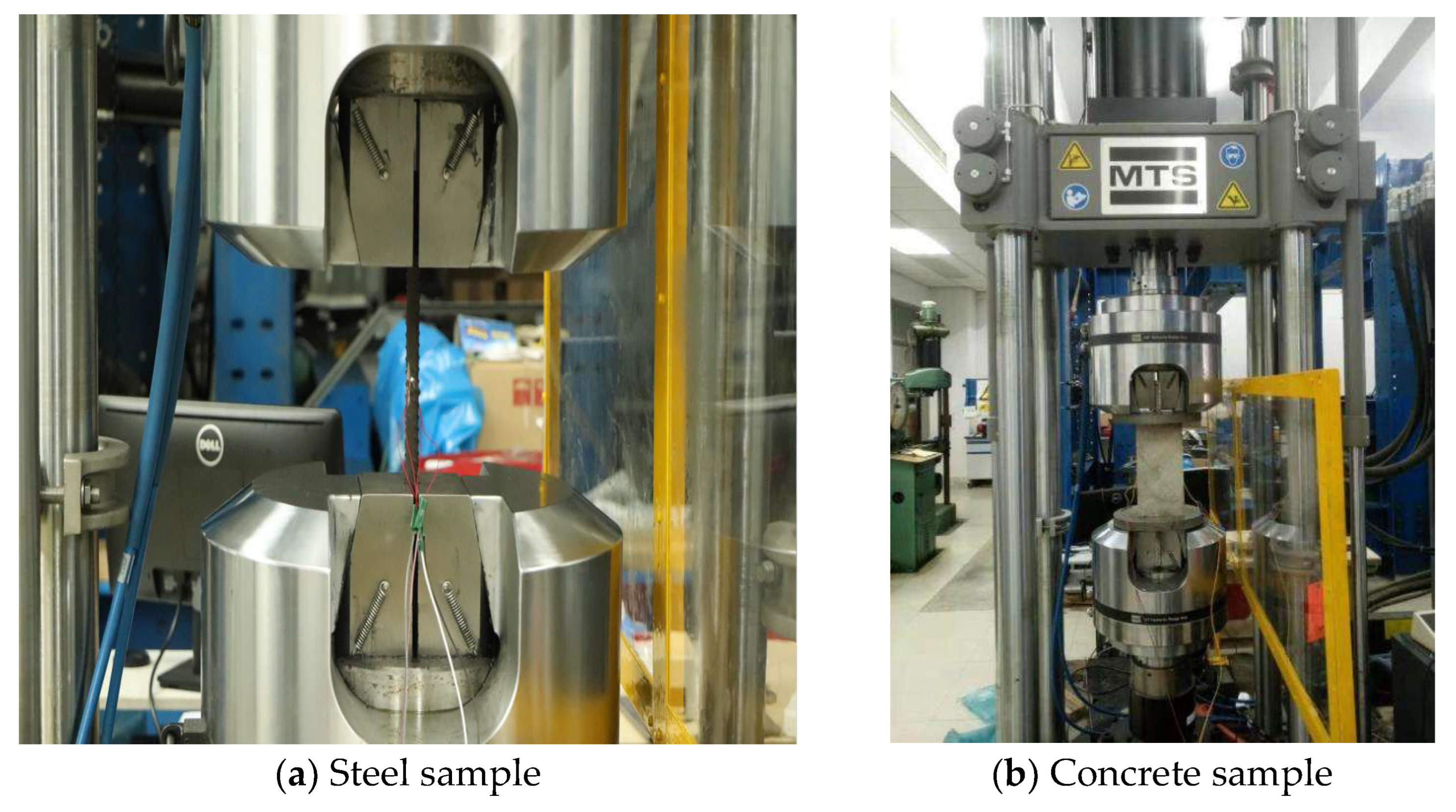

2.2. Material Performance Testing

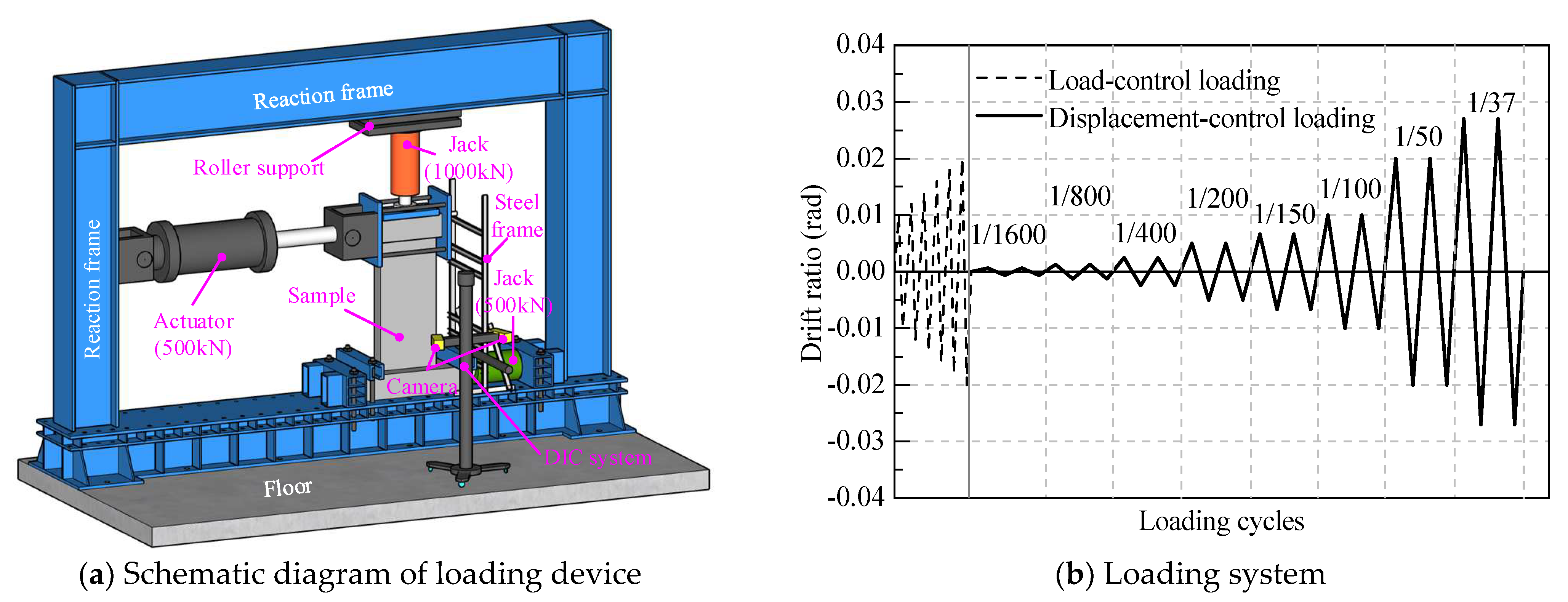

2.3. Loading Design

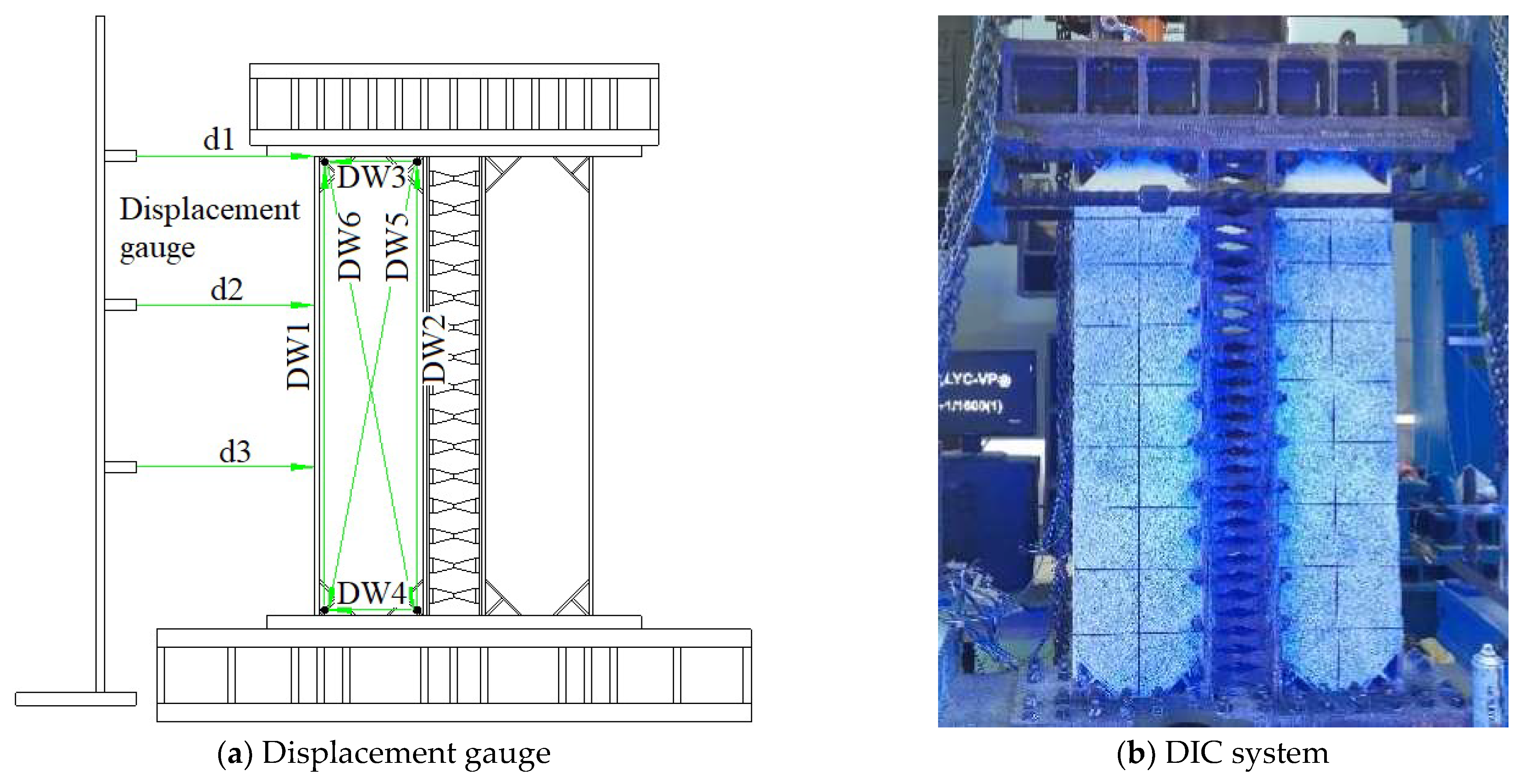

2.4. Data Collection

3. Analysis of Testing Results

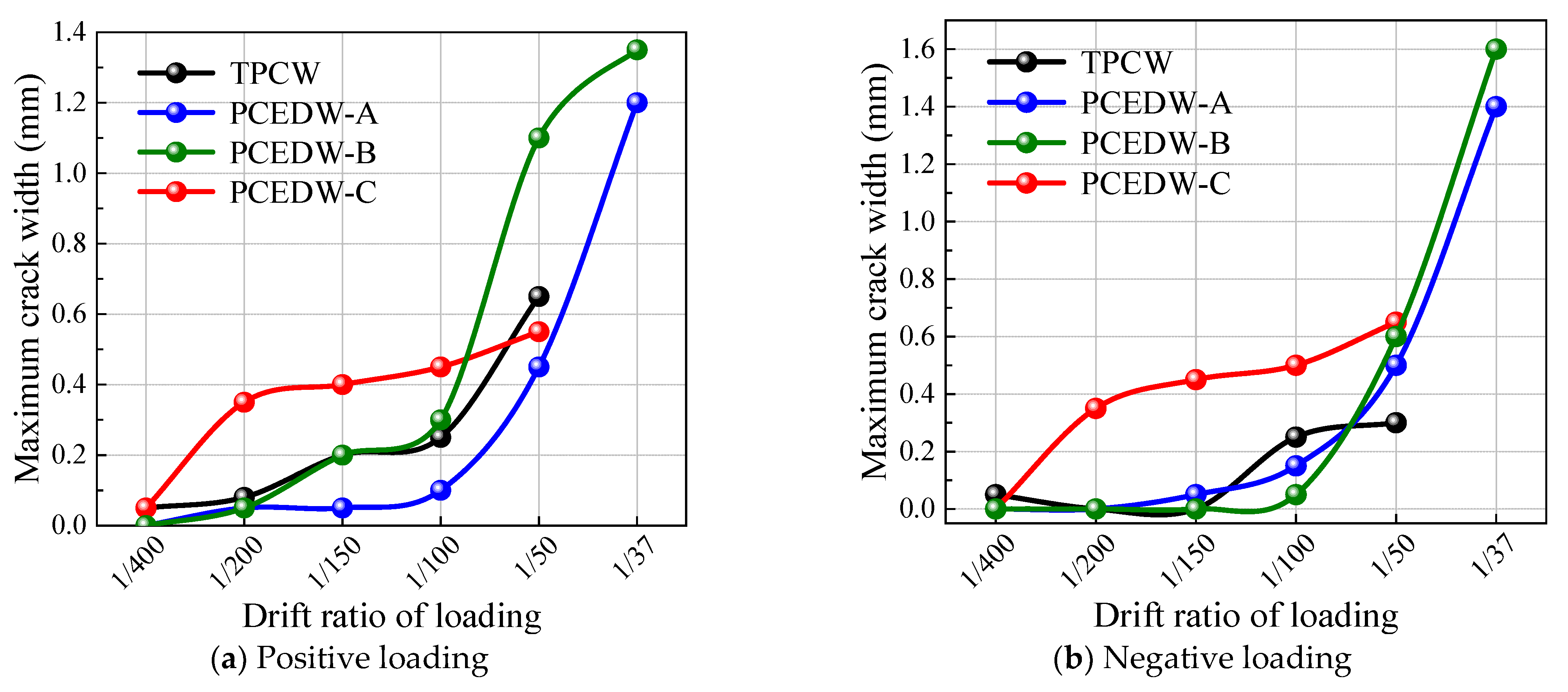

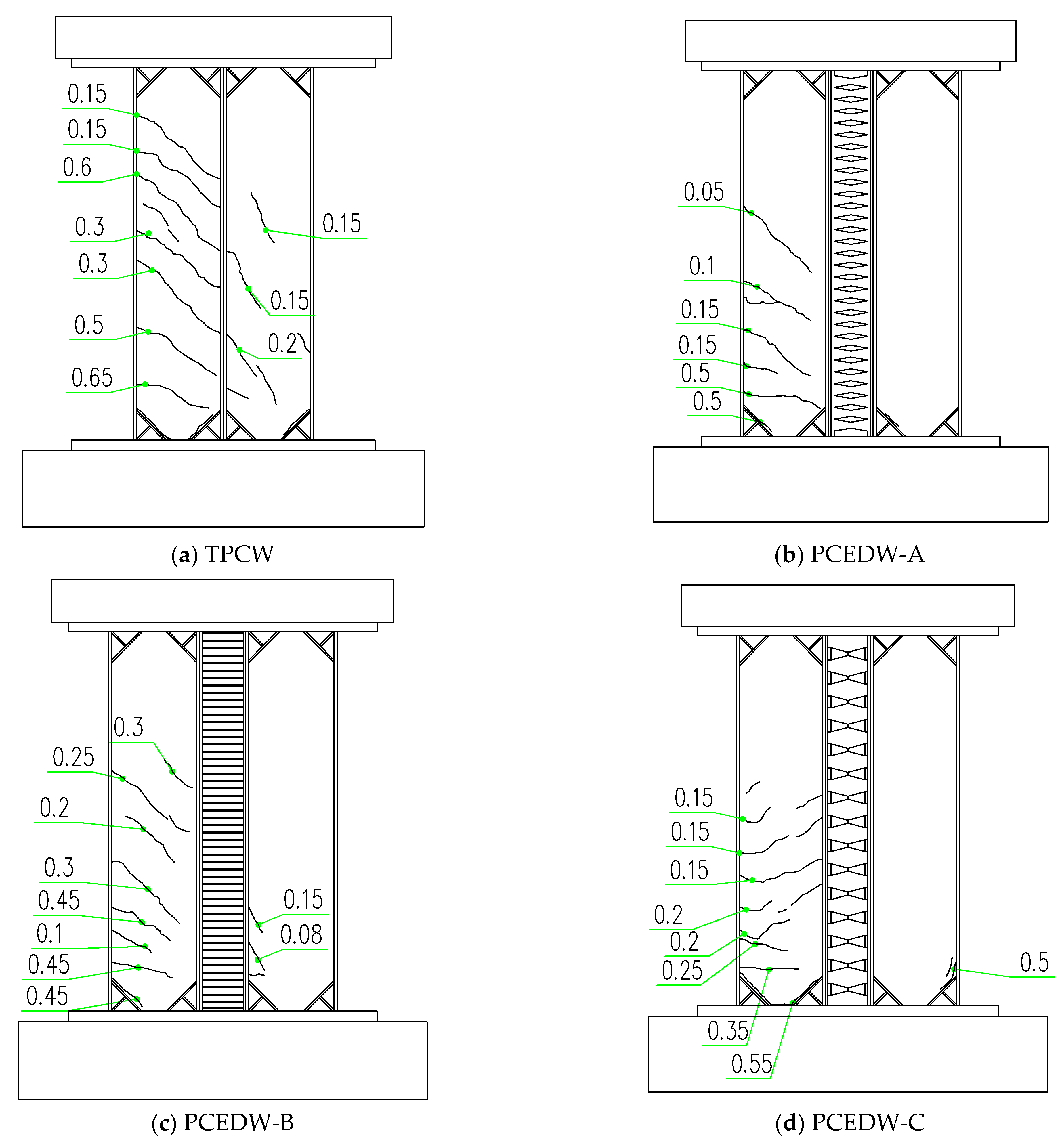

3.1. Development of Structural Damage

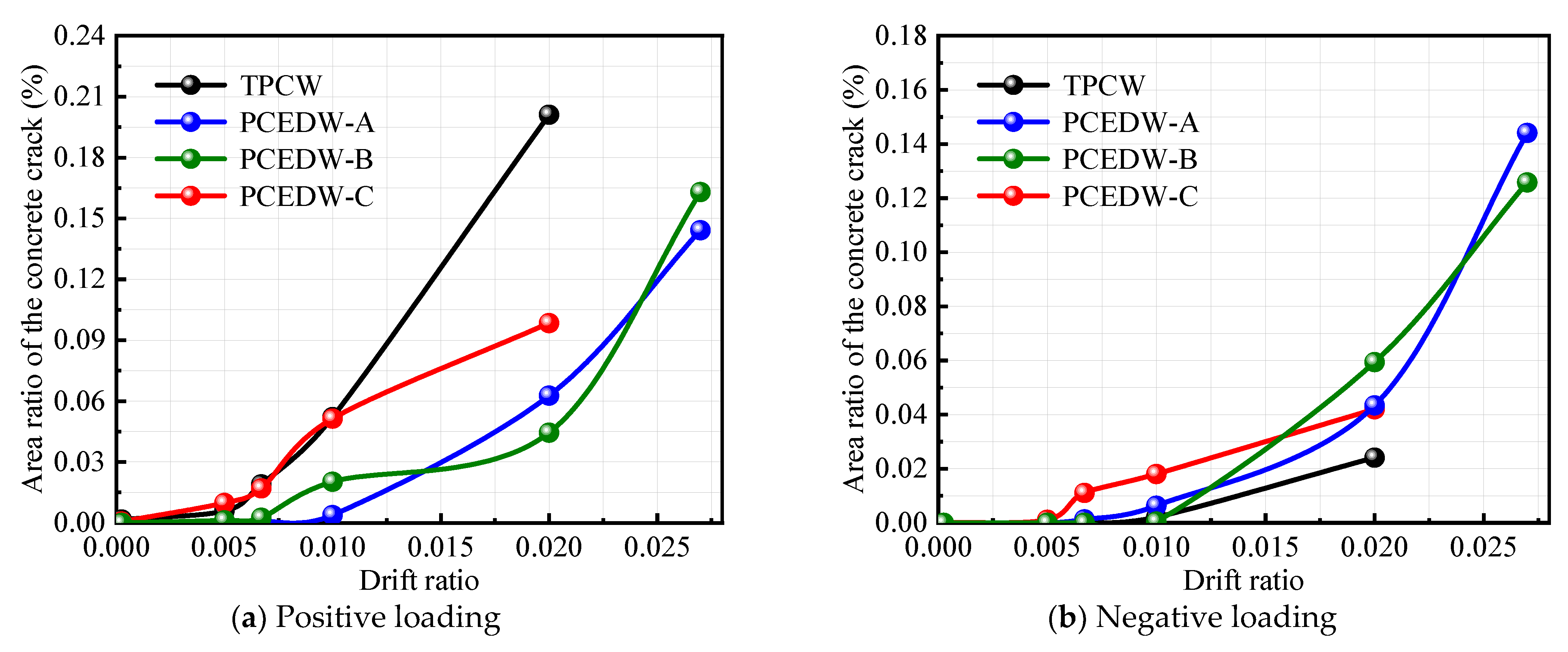

3.2. Area Ratio of the Concrete Crack

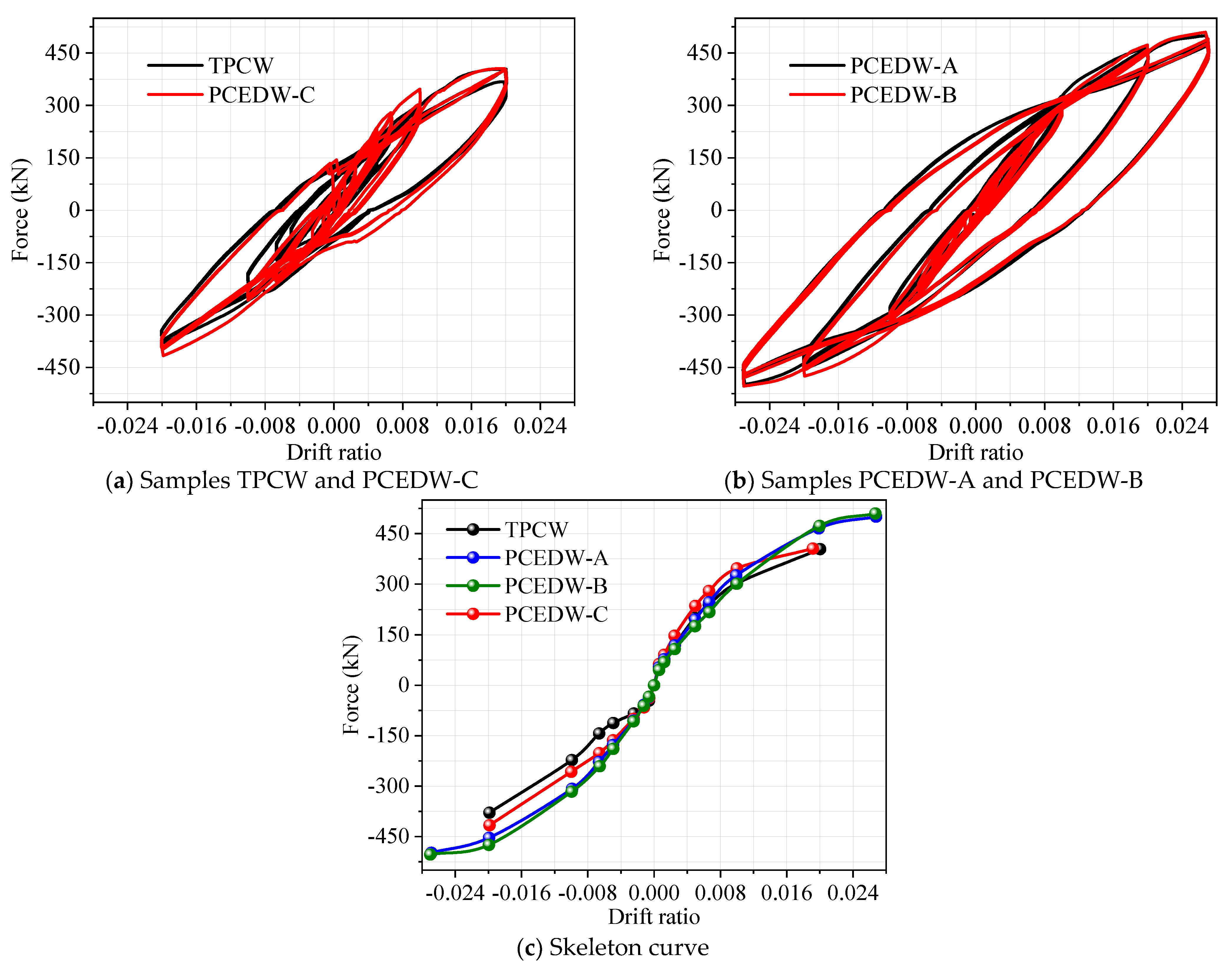

3.3. Load–Displacement Relationship

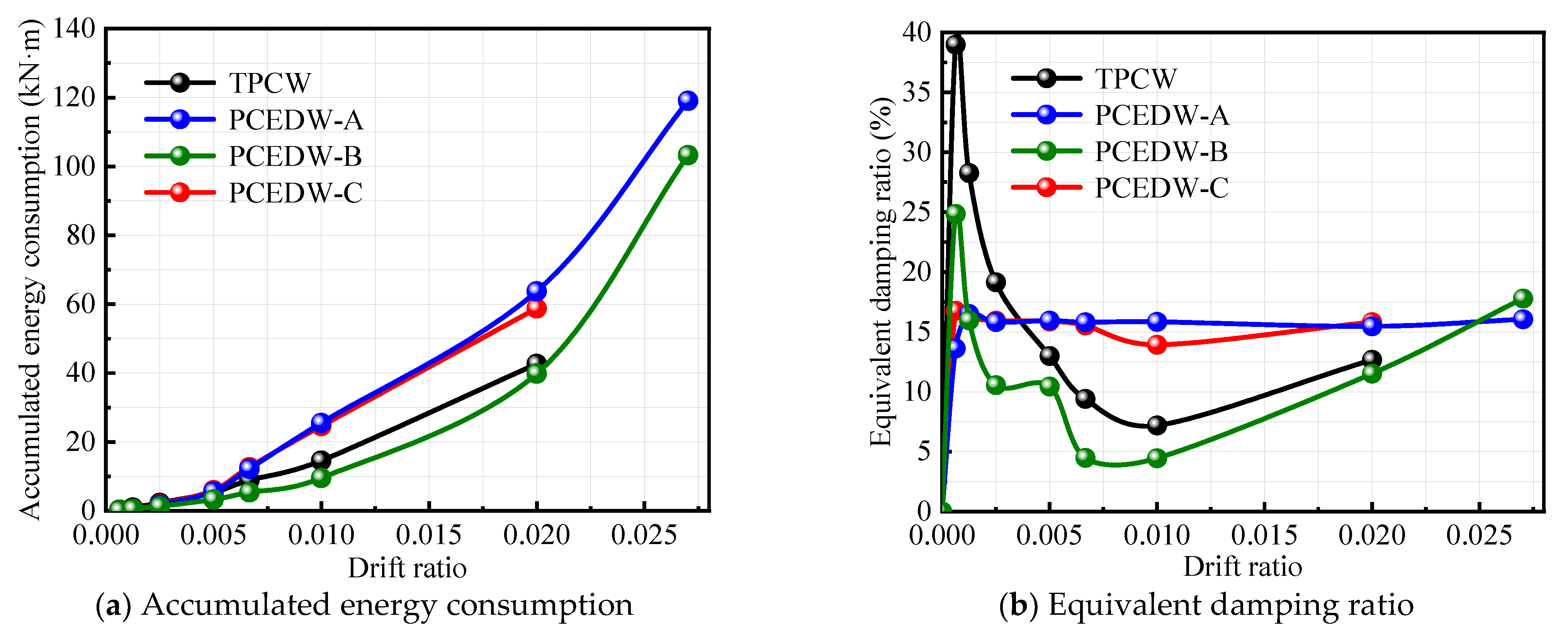

3.4. Energy-Dissipation Characteristic

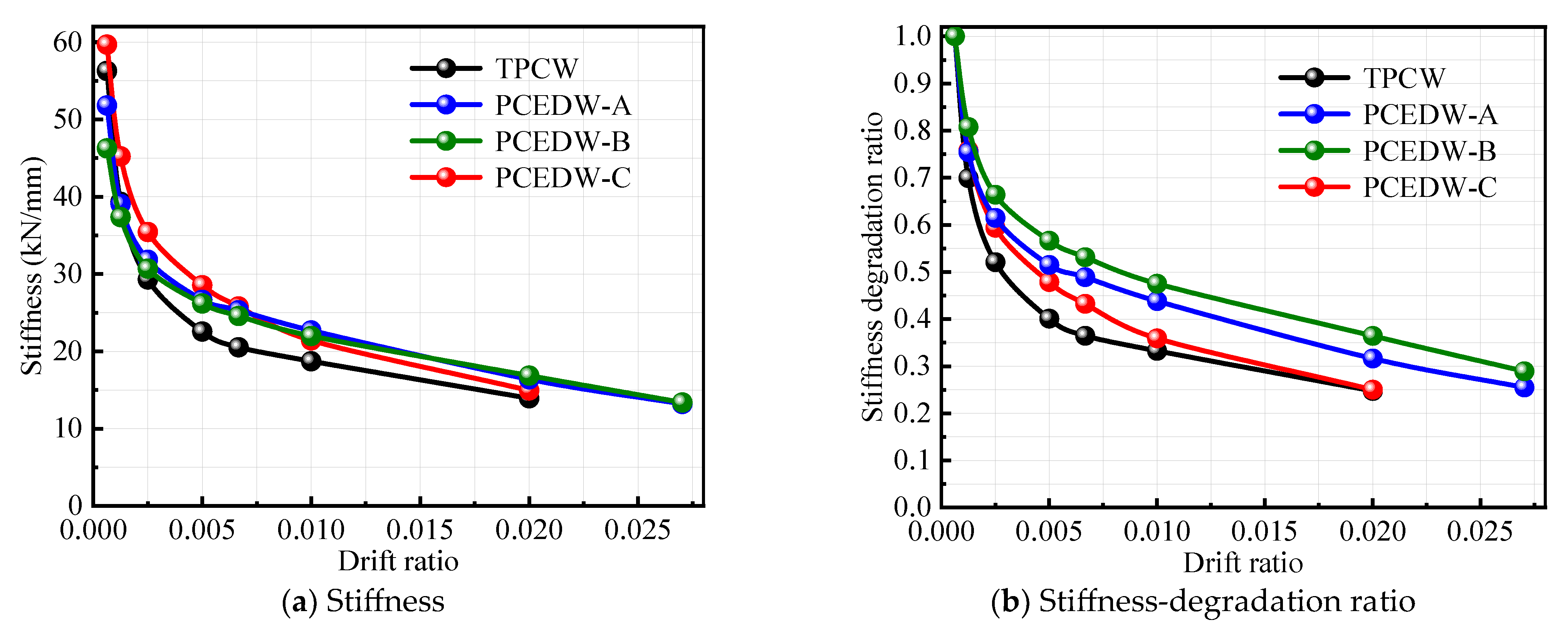

3.5. Stiffness Degradation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, D.; Han, Q.; Xu, S.; Zheng, Z.; Luo, Q.; Mao, J. Damage and deformation of a new precast concrete shear wall with plastic damage relocation. Steel Compos. Struct. Int. J. 2023, 48, 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.; Zhang, N.; Gu, Q. A review on mechanical and structural performances of precast concrete buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Yasir, N. Accurate equivalent analysis models and performance evaluation of precast concrete shear walls. Structures 2024, 70, 107696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Ye, M.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Cao, W. Seismic performance evaluation of prefabricated concrete shear walls with anchorage defects. Eng. Struct. 2024, 314, 118392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, Z.; Dong, W.; Zhao, S. Study on seismic performance of the prefabricated shear wall with different reinforcement methods based on recycled bead steel wire. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Z. Experimental seismic behavior of innovative composite shear walls. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 116, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hong, Q.; Zhou, M. Tests and analysis on hysteretic behavior of buckling-restrained steel plate shear wall. J. Build. Struct. 2009, 30, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.; Deng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Y. Experimental analysis on energy dissipation mechanism and seismic performance of steel truss coupling beam-coupled shear wall structure. J. Civ. Archit. Environ. Eng. 2014, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Richard Liew, J.Y.; Xiong, M.; Fu, X. Hysteresismodel of a novel partially connected buckling-restrained steel plate shear wall. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 125, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Richard Liew, J.Y.; Fu, X. Panel action of novel partially connected buckling-restrained steel plate shear walls. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 128, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Ou, J.; Richard Liew, J.Y. Stability of buckling-restrained steel plate shear walls with inclined-slots: Theoretical analysis and design recommendations. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 117, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xue, Z.; Xiao, S. Seismic behavior of Self-Buckling-Restrained Steel Plate ShearWall made by two incline-slotted infill plates. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 133, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Jiang, F.; Cao, W.; Wu, H.; Liu, H. Study on seismic behavior of composite shear wall with paralleled CFST columns and steel plate energy-consuming connectors. J. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2012, 32, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Dai, C.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, K. Seismic behavior of shear dominant bolted endplate steel coupling beam of composite coupled shear wall. J. Build. Struct. 2014, 35, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J. Seismic Performance of Shear Wall Structure with Novel SMA Dampers in Coupling Beams. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y. Loadding on energy dissipating low-rise concrete shear wall with mezzanine rubber cushion. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2003, 23, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xu, Q.; Wu, B. Energy dissipated low-rise concrete shear wall with tube filled with concrete. J. Harbin Univ. C. E. Archit. 2000, 33, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Xu, M.; Ren, Z. Study on prefabricated composite shear wall cladding anti-shedding connection structure. Structures 2024, 66, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.-D.; Cui, Y.; Pan, P.; Ren, J.-Y. Development of prefabricated composite energy-dissipating slotted shear wall. Eng. Struct. 2019, 199, 109577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Cyclic performance of prefabricated buckling-restrained steel plate shear wall with two-side connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 227, 109293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Wang, P. Experimental study on seismic behaviour of precast composite shear wall with ceramsite foam concrete interlayer. Structures 2025, 74, 108512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Zhou, Y.; Gan, L.; Wu, J.; Guo, H. Bearing capacity of horizontal joints of UHPC prefabricated shear walls with vertical bars splicing by cold-extrusion sleeves. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wu, C.; Xu, Y. Parameter Optimal Investigation of Modular Prefabricated Two-side Connected Buckling-Restrained Steel Plate Shear Wall. Structures 2021, 29, 2028–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, T.; Sun, H.; Ruan, S.; Qiu, H. Parametric study on lateral behavior of totally precast RC shear wall with horizontal bolted connection. Structures 2023, 57, 105100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Yao, Z.; Qin, Y.; Kali, A.; Chen, Q.; Niyazi, H. Seismic performance of precast concrete shear walls based on grouted corrugated metallic duct hybrid connection. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemab, F.; Schmidt, M.; Baktheer, A.; Classen, M.; Chudoba, R. Automated detection of propagating cracks in RC beams without shear reinforcement based on DIC-controlled modeling of damage localization. Eng. Struct. 2023, 286, 116118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Study on Improvement of Seismic Structure of New Type Modular Composite Shear Wall. Master’s Thesis, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Y. Design and FE analysis for an assembled biconical energy dissipator(BED). J. Vib. Shock 2012, 31, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Guo, L. Cyclic behavior of low shear-span ratio dovetailed profiled steel–concrete composite shear walls. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 59, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Size | Sample | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Ratio of Intensity and Yield Strength | Elastic Modulus (×105 MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner steel plate | 3 mm | a/b/c | 415/389/406 | 510/494/503 | 1.23/1.27/1.24 | 1.94/1.96/1.97 |

| Average | 403 | 502 | 1.25 | 1.96 | ||

| Steel plate of metal damper | 2 mm | a/b/c | 420/410/401 | 500/510/512 | 1.19/1.24/1.28 | 1.95/1.95/1.92 |

| Average | 410 | 507 | 1.24 | 1.94 | ||

| Connecting steel plate | 10 mm | a/b/c | 337/322/314 | 461/451/458 | 1.37/1.40/1.46 | 2.06/2.12/2.00 |

| Average | 324 | 457 | 1.41 | 2.06 | ||

| Steel bar | 8 mm | a/b/c | 307/302/314 | 447/440/441 | 1.47/1.47/1.42 | 2.09/2.12/2.06 |

| Average | 308 | 443 | 1.45 | 2.09 |

| Sample | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Convert Axial Compressive Strength (MPa) | Convert Axial Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a/b/c | 31.52/30.30/31.97 | 21.09/20.31/21.42 | 2.44/2.33/2.44 | 32,439/31,979/32,601 |

| Average | 31.27 | 20.94 | 2.41 | 32,339 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of a New Type of Prefabricated Steel–Concrete-Composite Energy-Dissipation Shear-Wall System. Buildings 2025, 15, 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060941

Wang L, Wu X, Feng J, Wang Y, Wang D. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of a New Type of Prefabricated Steel–Concrete-Composite Energy-Dissipation Shear-Wall System. Buildings. 2025; 15(6):941. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060941

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Liuhuo, Xiaohui Wu, Jie Feng, Yanfeng Wang, and Dayang Wang. 2025. "Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of a New Type of Prefabricated Steel–Concrete-Composite Energy-Dissipation Shear-Wall System" Buildings 15, no. 6: 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060941

APA StyleWang, L., Wu, X., Feng, J., Wang, Y., & Wang, D. (2025). Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of a New Type of Prefabricated Steel–Concrete-Composite Energy-Dissipation Shear-Wall System. Buildings, 15(6), 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15060941