Abstract

Monumental rock-cut tombs decorated with wall paintings or reliefs were rare in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. Exceptions include the 18th Dynasty tombs of Djehutyhotep (Debeira) and Hekanefer (Miam), and the 20th Dynasty tomb of Pennut (Aniba). The three tombs present typical Egyptian artistic representations and inscriptions, which include tomb owners and their families, but also those living under their direct control. This paper compares the artistic and architectural features of these decorated, monumental rock-cut tombs in light of the archaeological record of the regions in which they were located in order to contextualize art within its social setting in colonized Nubia. More than expressing cultural and religious affiliations in the colony, art seems to have been essentially used as a tool to enforce hierarchization and power, and to define the borders of the uppermost elite social spaces in New Kingdom colonial Nubia.

1. Introduction

Decorated rock-cut tombs represent a major aspect of elite mortuary landscapes in the New Kingdom, with sites in the Memphite and Theban regions usually representing the elite ideal during this period (Kampp 1996; Staring 2023). It is common to accept that during the New Kingdom colonization of Nubia, Egyptian ideals travelled alongside colonizers and, once they reached Nubia, substituted local ideals regarding death and dying (Trigger 1976, p. 115; Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, pp. 7–8; Morkot 2013). However, by looking at mortuary contexts throughout Nubia, it is possible to recognize a significant degree of variation within and across several sites (Lemos 2020; cf. Thill). Diversity in Nubia has been recognized mostly on the grounds of cultural entanglements, which opened up space for acknowledging Nubian and Egyptian mixtures in contexts of cultural interactions, resulting in innovation stemming out of various choices available to individuals and communities living in the colony (Smith and Buzon 2017; Smith 2021; cf. van Pelt 2013). These choices, however, were limited to elites who had access, through consumption, to various object types that were used to establish and communicate cultural affiliations and social distinction (Lemos 2020). For the vast majority of the working population in New Kingdom Nubia, cultural choices through material culture were hardly available, which is made apparent by the high levels of scarcity experienced by non-elites buried in vast pit grave cemeteries (Lemos 2021).

Contextualizing Egyptian funerary art in New Kingdom colonial Nubia further reveals the social context in which cultural interactions took place (Lemos forthcoming). Egyptian funerary art, here mostly understood as parietal art (paintings and reliefs) inside tombs, seems to have played a major role in establishing social differentiation in the colony. Funerary art helped shape the boundaries of elite social spaces, understood as being formed of “principles of differentiation or distribution constituted by the set of properties active within the social universe in question” (Bourdieu 1985, p. 196). Elite social spaces shaped by restricted funerary art remained largely impenetrable to those who did not have access to tomb wall decoration in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. In a similar way to Egypt, non-elite populations in Nubia had no access to artistic representations in their burials. However, decorated rock-cut tombs were also out of the reach of higher-ranking officials in the Nubian colony, which is a major difference compared to Egyptian mortuary landscapes of the same period. Colonial elites would have access to restricted material items, both imported and locally produced, but almost never to wall paintings. This could be potentially explained by a lack of access to skilled artists such as the ones living in Egypt at sites such as Deir el-Medina (Laboury 2012).

In New Kingdom colonial Nubia, Egyptian-style wall paintings and reliefs were generally restricted to a handful of monumental rock-cut tombs with decorated chapels, in a context where the majority of rock-cut tombs remained undecorated. Rock-cut tomb chapels themselves were rare in the Nubian funerary landscape, with the most prevalent type of elite tombs comprising underground tombs with shafts leading to various collectively used chambers (Schiff Giorgini 1971; Minault-Gout and Thill 2012; Spence 2019, p. 549; Budka et al. 2021). Funerary art seems to have been used by a few individuals to establish and communicate power in the colonial social landscape. The majority of these individuals were Nubians working for the Egyptian colonial administration, which reveals interesting dynamics in the colonial society in which Egyptian settlers were likely also among those who did not have access to such features considered key in Egyptian elite cemeteries (Lemos 2021).

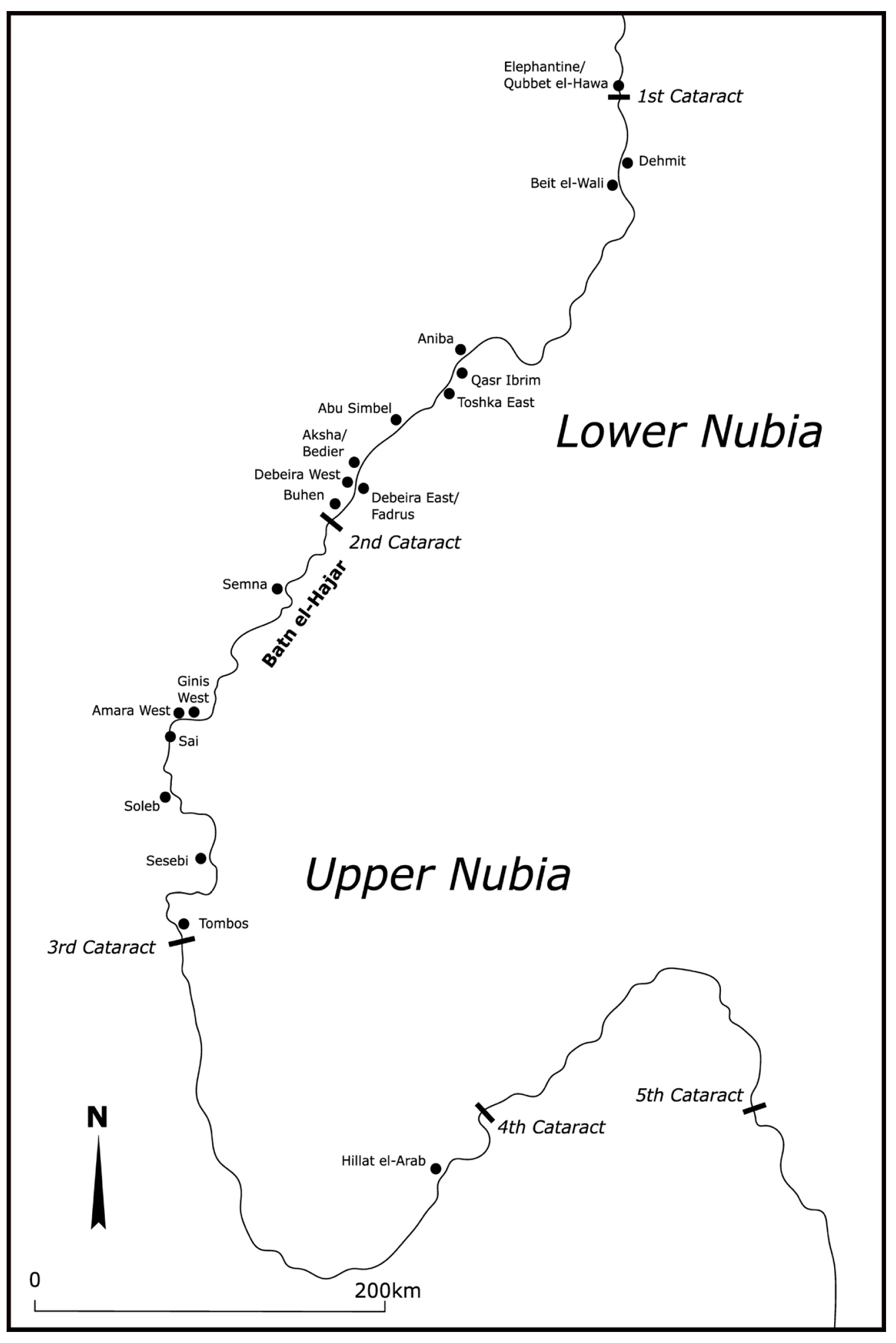

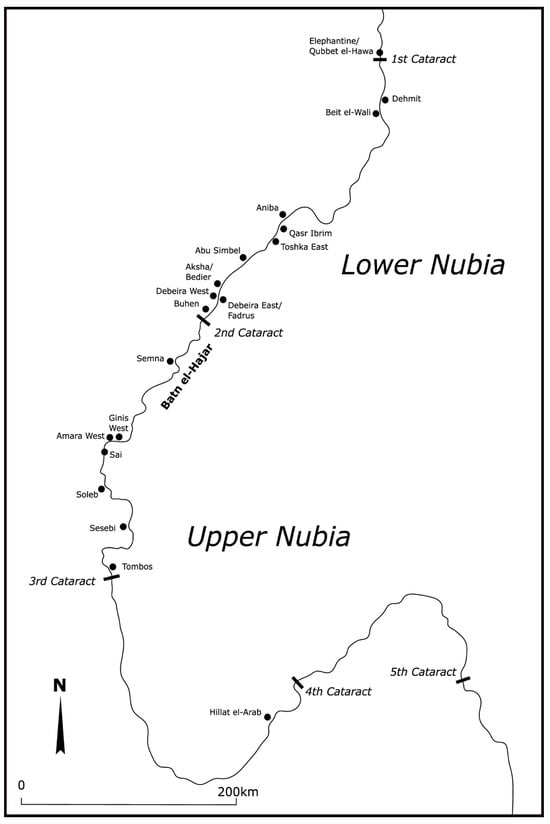

This paper examines the social context of three decorated, monumental rock-cut tombs in the New Kingdom Nubian colony: the tomb of Djehutyhotep, also known as Paitsy, at Debeira; the tomb of Hekanefer at Toshka; and the tomb of Pennut at Aniba (Figure 1). The three tombs were exceptional in Nubian mortuary landscapes of the New Kingdom colonial period, which might suggest the existence of major wealth disparities between Lower and Upper Nubia. By looking at these tombs comparatively, we learn that funerary art was used as a key feature for establishing and communicating power in the colony, where elites also struggled to have access to restricted features such as art or material culture, regardless of their ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Map of Nubia showing the sites mentioned in the text. Drawing by R. Lemos.

2. Colonial Mortuary Landscapes in New Kingdom Nubia

The vast majority of tombs in New Kingdom colonial Nubia were the pit graves of workers, the majority of which were likely farmers, as suggested by a comparison of burial assemblages from various cemeteries (Lemos 2020). This is mostly represented by the largest non-elite cemetery ever excavated in Sudanese Nubia—Fadrus—but also small-scale cemeteries in peripheral areas such as the Batn el-Hajar or simpler graves of laborers at major sites such as Tombos (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991; Edwards 2020; Smith and Buzon 2014, p. 203; Lemos and Budka 2021).

The cemetery of Fadrus dates from the early 18th Dynasty to the reign of Amenhotep III or Akhenaten. With more than 900 burials, the cemetery houses the simple graves of the working communities of ancient Tehkhet, a region ruled by an indigenous family with close ties to Egyptian colonizers (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991). Most of the graves were shallow pit burials, usually housing the skeletal remains of a single body deposited in an extended position with no associated finds. These simple, unprovided graves comprise c. 70% of the burials at Fadrus (Spence 2019, p. 557). When material culture is found in association with these non-elite burials, it is not unusual to find undisturbed pits containing one or two beads in the neck area of the body (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, pp. 256–57). Among those who were able to achieve being buried with something, a handful of Egyptian-style pots or a single scarab could also be found, but those graves represent only a small fraction of this group of burials (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, pp. 224–25).

At Fadrus, a small group of individuals were buried in more elaborate graves (Spence 2019, p. 547). These were side- or end-niche tombs, or even pits accessible through small ramps. An even smaller group of burials comprise more elaborate tombs with complex mud-brick structures. In these tombs, much larger quantities of objects were excavated, including significant Egyptian-style pottery assemblages, jewelry, etc. The largest of those, tomb 511, comprised two chambers in which several individuals were deposited alongside a larger than usual number of grave goods (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, pp. 281–82; Lemos forthcoming). Tomb 511 yielded the only heart scarab excavated at Fadrus. Heart scarabs were the most restricted items in the Nubian mortuary landscape during the New Kingdom colonial period. The highly unusual presence of this object in a non-elite cemetery and the concentrations of material culture in more elaborate graves can be explained through the lens of collective or communal engagement (DeMarrais and Earle 2017). In a context of extreme scarcity, non-elite individuals gathered together to ensure the possession of desired objects in death, including highly restricted ones, which would have contested Egyptian elite ideals of dying centered on concepts of individuality (Lemos 2021).

A similar context can be detected in the geographical peripheries of the New Kingdom Nubian colony. Larger tombs in areas such as Ginis West and the Batn el-Hajar, which housed the burials of several individuals, concentrated high numbers of funerary objects in contexts of major scarcity (Lemos 2021; Lemos and Budka 2021; Vila 1977; Nordström 2014). This can also be explained through the lens of collective or communal engagement. In these areas, small clusters of tombs have also been excavated. These are usually individual pit graves, rarely accompanied by burial goods, similar to the social context of the non-elite cemetery of Fadrus (Edwards 2020). Pit burials of the vast majority of the working population have also been excavated at elite sites such as Tombos. The placement of less privileged burials in a cemetery serving the elite of Tombos, a major colonial settlement, provides insights into the social composition of Egyptian temple-towns (Smith and Buzon 2014, p. 203). It is possible that those burials belonged to urban workers closer to colonial elites than to non-elite farming communities, such as the one buried at Fadrus (Spencer et al. 2014).

Large elite cemeteries developed in association with settlements founded by ancient Egyptian colonizers in the course of the New Kingdom. In these cemeteries, the most significant of which being Aniba, Sai, Soleb, Sesebi, Amara West and Tombos, most tombs comprise a vertical shaft leading to various underground chambers where various individuals were deposited (Steindorff 1937; Minault-Gout and Thill 2012; Schiff Giorgini 1971; Spence 2019, p. 549; Binder 2014; Smith 2003). These tombs were largely used over a long period of time (Schiff Giorgini 1971, pp. 311–12). Material assemblages from these tombs comprise restricted items such as shabtis and heart scarabs, but also an abundance of other more widespread items such as jewelry (Lemos 2020). Superstructures include pyramids and vaulted chapels. Inscribed/carved architectural features were associated with the superstructures of elite tombs in the wealthiest cemeteries, especially at Aniba (Steindorff 1937, plate 25). Despite the overall wealth of tombs, wall decoration was largely absent in elite cemeteries associated with colonial settlements, although this could be related to issues of preservation of mud-brick superstructures.

At places such as Debeira East, undecorated rock-cut tombs must have housed the burials of higher local elites (Sherif 1960). Nevertheless, wall paintings or reliefs were only part of the most exceptional burial contexts in New Kingdom Nubia, which belonged to the highest elites. Even the tomb of the chief of Tehkhet, Amenemhat, Djehutyhotep’s brother, did not include wall paintings like his brother’s tomb, despite Amenemhat’s exquisite stela (Spence 2019: 556). The tomb of Amenemhat, located across the river from his brother’s tomb, at Debeira West, was partly cut into a sandstone prominence (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, plates 46 and 54). The tomb’s ancestors’ shrine was cut into the rock. Above the shrine, there was a large mud-brick pyramid superstructure. This would place the tomb somewhere in between proper monumental rock-cut tombs, such as the tombs of Djehutyhotep, Hekanefer and Pennut, and the most common type of elite tombs in major cemeteries like Aniba, Sai or Soleb.

3. The Decorated Rock-Cut Tombs of Djehutyhotep, Hekanefer and Pennut

3.1. Djehutyhotep

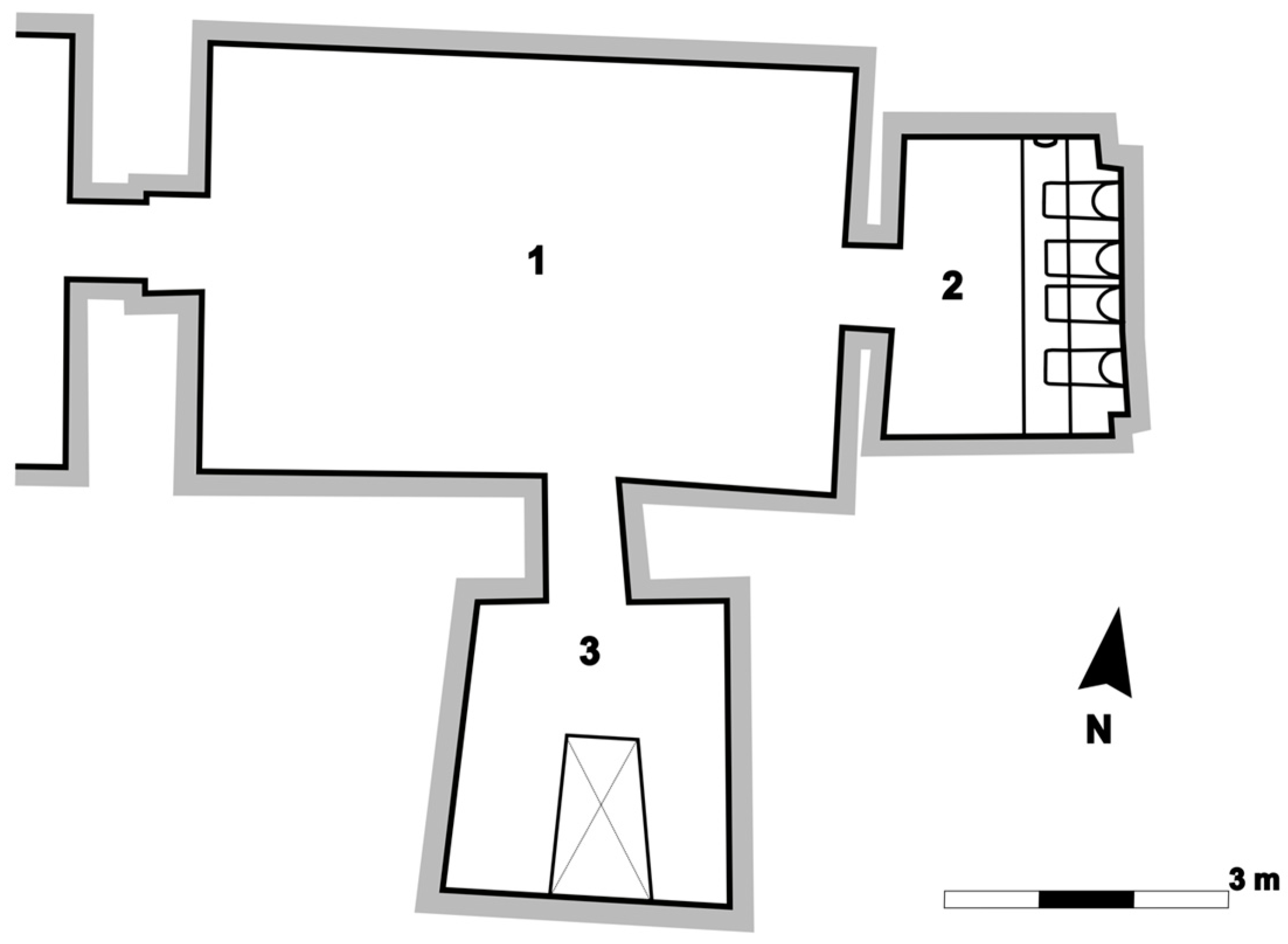

Originally located at Debeira East, the tomb of Djehutyhotep was cut into the rock in a sandstone cliff not far from the riverbank (Thabit 1957). The tomb was accessible through a ramp leading to the entrance, which was decorated with an inscribed lintel and jambs (Säve-Söderbergh 1960). The entrance, which was located to the west of the tomb, led to a large rectangular chamber through which an ancestors’ shrine could be reached to the east. On the south wall of the large chamber, a smaller side chamber housed a deep shaft leading to various underground funerary chambers (Figure 2).

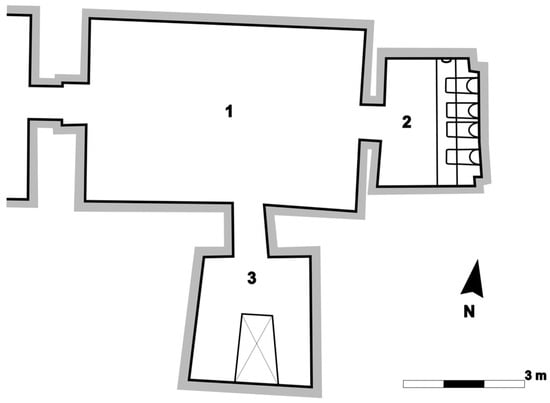

Figure 2.

Plan of the upper rock-cut chambers of the monumental tomb of Djehutyhotep. Different parts of the tomb are numbered: (1) main chamber or tomb chapel; (2) ancestral shrine; and (3) side chamber containing a vertical shaft leading to various burial chambers. Drawing by R. Lemos after Thabit (1957, p. 82). The statues in (2) were reconstructed based on archival images in the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia and the Hinkel archives.

In 1963, during the UNESCO Nubian campaign, the tomb of Djehutyhotep was the first of the monuments of Sudanese Nubia to be dismantled for relocation to Khartoum, where it was reassembled, in 1970, in the courtyard of the Sudan National Museum (Hinkel 1978).

Historical knowledge of Djehutyhotep and his family comes from inscriptions in various places (Arkell 1950; Moss 1950). Texts from Qubbet el-Hawa, Elephantine, Qasr Ibrim, Buhen, Serra and Debeira allow us to establish the history of an indigenous elite family who served the Egyptian colonial administration of Nubia during the New Kingdom (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, pp. 190–204). Djehutyhotep’s main title was “great (=chief) of Tehkhet”. He was active during the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BCE) (Säve-Söderbergh 1991). Djehutyhotep’s grandfather, a man known as Teti or Djawia, his Nubian name, was also a chief of Tehkhet. Ruiu, Djehutyhotep’s father, and Amenemhat, his brother and successor, possessed the same title. The two brothers, Djehutyhotep and Amenemhat, were also “scribes”, the former being directly associated with the colonial exploitation of gold, as attested by rock inscriptions found deep in the Nubian desert (Davies 2020, p. 188). Later chiefs of Tehkhet, known by fragmentary evidence, were probably members of the same family. For instance, the chief of Tehkhet Ipi was granted land by Heqanakht, the Viceroy of Kush during the reign of Ramses II (c. 1276–1259 BCE) (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, p. 204; Török 2009, p. 174). Another Ramesside chief of Tehkhet is mentioned on a fragmentary 19th Dynasty shabti found in one of the undecorated rock-cut tombs at Debeira East (Figure 3). Despite the restricted material culture retrieved in such undecorated rock-cut tombs, wall paintings continued to be highly inaccessible to the elites buried in such tombs throughout the Nubian colony.

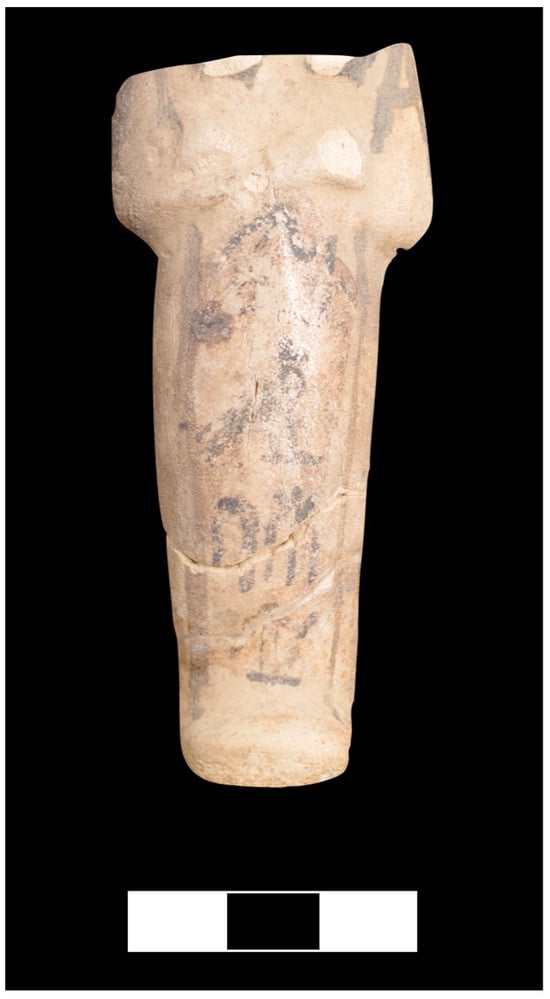

Figure 3.

A 19th Dynasty faience shabti of chief Hormose, from one of the undecorated rock-cut tombs at Debeira East. Leclant (1962) briefly mentioned the existence of this shabti, which has so far been overlooked. Photo by R. Lemos. Courtesy of the Sudan National Museum.

The fact that Djehutyhotep ended up owning a monumental rock-cut tomb decorated with wall paintings and architectural features carved with inscriptions directly results from his family’s long-lasting history of collaboration with the Egyptian colonization of Nubia. This generated material benefits for the family, especially Djehutyhotep and Amenemhat, whose tombs were clear outliers in the Debeira funerary landscape, which is mostly characterized by the scarcity experienced by the majority of its local population (Lemos forthcoming).

The main chamber in the tomb of Djehutyhotep was decorated with wall paintings that resemble the decoration of Theban tombs. The Djehutyhotep scenes include typical Egyptian elite motifs, such as a banquet scene with musicians, two scenes depicting the inspection of workers, and one of the earliest chariot scenes in a private tomb in the Nile valley (Säve-Söderbergh 1960). Despite significant similarities with Theban tombs, the scenes in the tomb of Djehutyhotep are also evidence of the specificities of their local Nubian context. For instance, it has been argued that the musicians represented in the tomb performed a Nubian-style song/dance accompanied by drums (Wild 1959). A different approach to body proportion in one of the inspection of workers scenes might also denote a local approach to Egyptian art, which, nonetheless, was used to reinforce the powerful position of those individuals who had access to (Egyptian?) painters to decorate and inscribe their tombs.

It is difficult to assign thematic order to the scenes displayed on the walls of the main chamber in Djehutyhotep’s tomb, as is the case with many Theban tomb chapels (Pereyra and Bonanno 2024). However, all the scenes in the tomb of Djehutyhotep share a common feature: the representation of social hierarchy, which brings to the symbolic realm of the tomb the same divisions between social spaces extant in the Nubian colonial society during the New Kingdom. This was likely connected to the fact that Djehutyhotep’s tomb chapel, like the later tomb chapels of Hekanefer and Pennut, worked as spaces of dissemination of extant hierarchies in New Kingdom Nubia. In fact, graffiti and material culture from the tomb demonstrate the presence of later visitors and occupants who would have been exposed to the social hierarchies displayed on the tomb chapel’s walls.

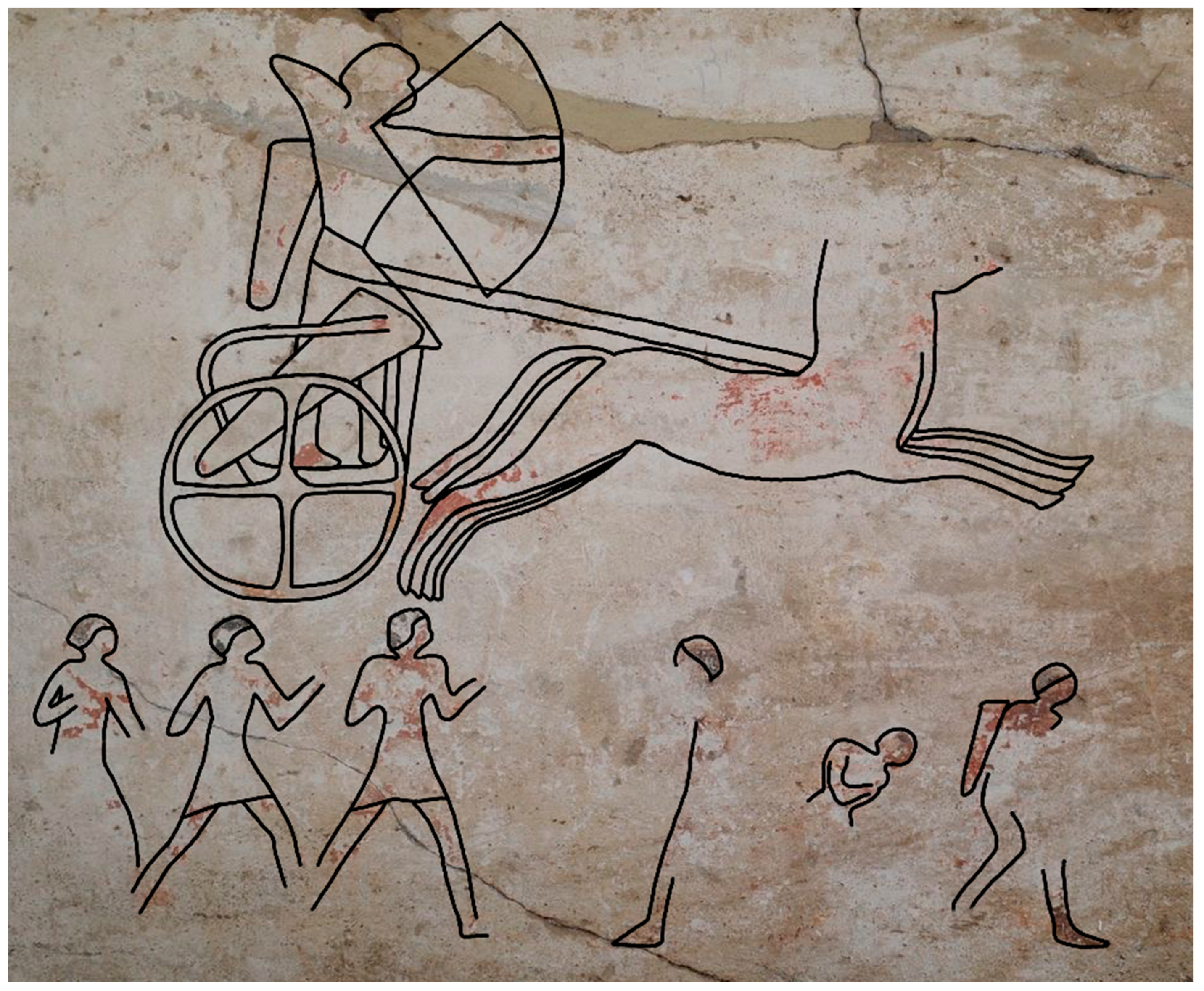

On the southwest wall of the main chamber, Djehutyhotep was depicted riding a chariot. The scene has been found badly preserved, although an earlier drawing and comparisons with a complete parallel scene from the tomb of Userhat (Theban Tomb 56) allow us to reconstruct most of the Djehutyhotep scene (Beinlich-Seeber and Shedid 1987, plate 12) (Figure 4). Similar representations, such as the one in the tomb of Amenedjeh (Theban Tomb 84) also help us reconstruct the Djehutyhotep scene (Wegner 1933, plate IXa). Säve-Söderbergh interpreted the Djehutyhotep depiction as a hunting scene (Säve-Söderbergh 1960, pp. 31–32), while Thabit interpreted the scene as a war depiction (Thabit 1957, p. 85). Djehutyhotep’s chariot was represented above six men of different skin colors, running. The first man seems to be carrying a quiver of arrows on his back. Despite the similarities between the abovementioned chariot register and the hunting scene in the tomb of Userhat, the overall context of the tomb of Djehutyhotep might point to another interpretation of this scene. The position of the men below the chariot, who seem to be running, following the movement of the chariot itself, suggests that this could be the representation of a patrol led by Djehutyhotep. The policemen in the Amarna tomb of Mahu, the chief policeman of Akhenaten, were depicted in the same running position (Davies 1906, plate XXVI). In the same tomb, the occurrence of running policemen in charge of patrolling the royal city and chariots used in these activities demonstrate the association between chariots and those in charge of imposing control and order (Stevens 2017, p. 104). As chief of Tehkhet, Djehutyhotep was directly in charge of the administration of various aspects of the Egyptian enterprise in the Debeira area, including the extraction of gold from the desert and the control of those under his jurisdiction, from the supervision of workmen to punishing those who did not follow the rules. The text of the stela of Amenemhat, Djehutyhotep’s successor, enumerates fighting crime as one of the duties of the chief of Tehkhet (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991, p. 203). Based on various similarities with Theban tombs (Sabbahy 2018, pp. 129–30), it is possible that the fragmentary chariot depiction in the tomb of Djehutyhotep represents a hunting scene. However, a more practical meaning (i.e., imposing control) cannot be ruled out.

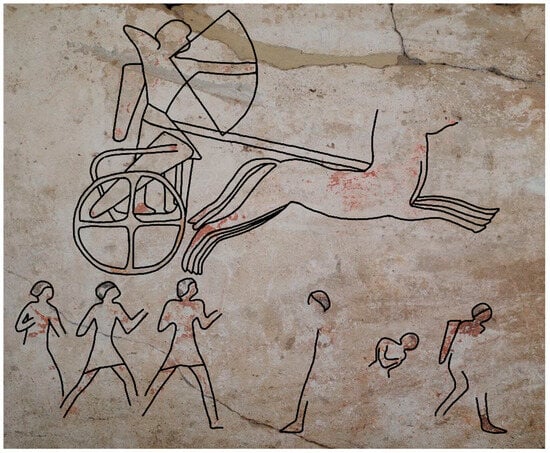

Figure 4.

Interpretation of the Djehutyhotep chariot depiction imposed onto the original scene on the southwest wall. Drawing by B. de Almeida Newton. Photo by R. Lemos. Courtesy of the Sudan National Museum.

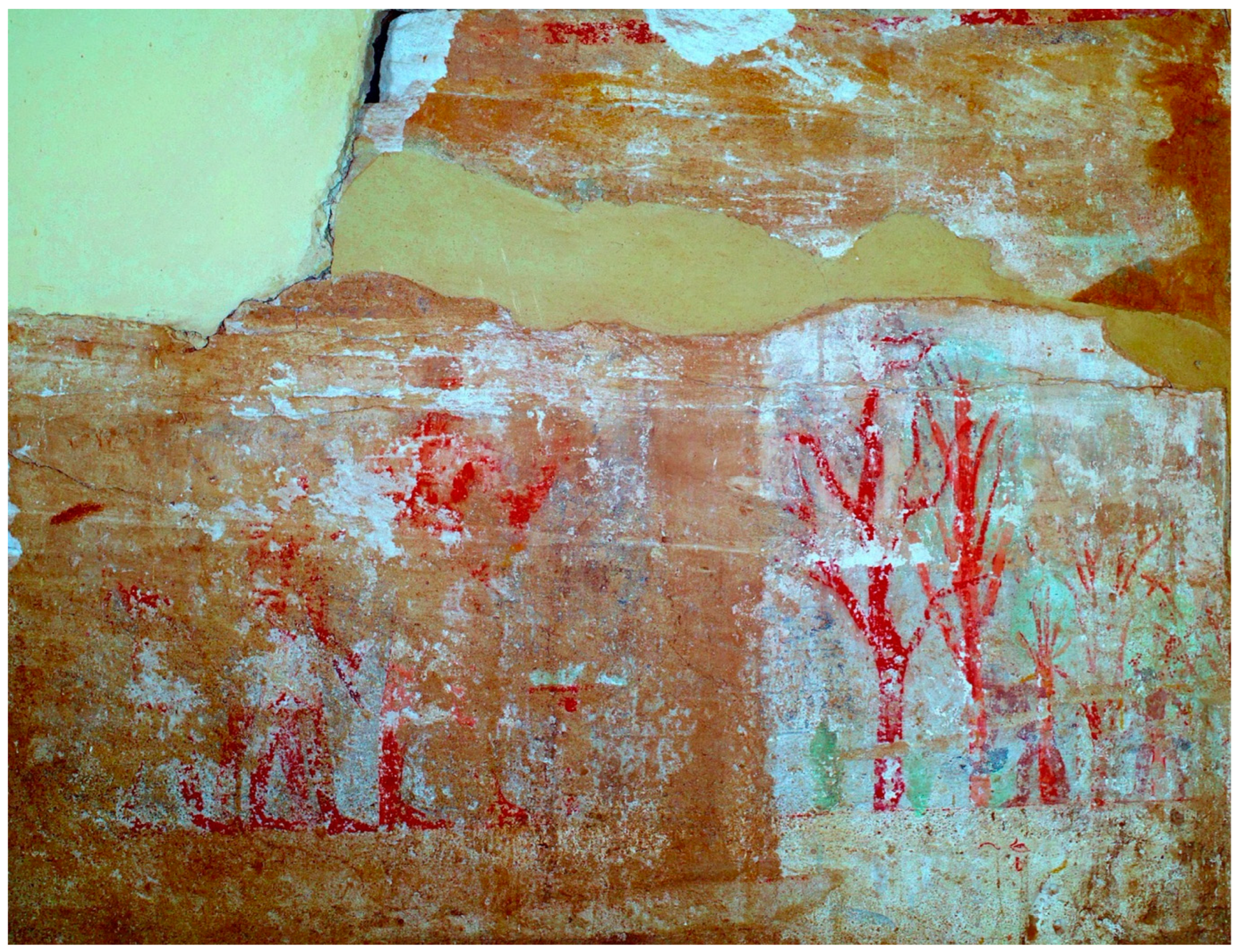

On the northwest wall, Djehutyhotep was represented supervising workmen (Figure 5). Djehutyhotep stands with his two arms prostrated in front of him, taller than his two followers. He is likely carrying a scribe’s palette to document what his workers are doing. In fact, a scribe’s palette inscribed for Paitsy, Djehutihotep’s Nubian name, was found in the tomb of his brother, Amenemhat, who seems to have recycled several objects that originally belonged to Djehutyhotep (Lemos et al. 2023). The presence of a scribe’s palette is suggested by Djehutyhotep’s position. Scribes are shown in the same position while recording tasks and produce in the tomb of Menna (Theban Tomb 69) (Wilkinson 1979, p. 43). Djehutyhotep is shown wearing an Egyptian-style broad collar, which, in Nubia, only appears in the uppermost elite contexts. One of his followers carries a stick, while the other seems to be carrying an arrow quiver (?) on his back, similar to one of the men in the hunting/patrol scene. This would be consistent with inspection of workers scenes in Egypt, such as the already mentioned representations in the tomb of Menna, where scribes record the activities performed by farmers, while other workers are shown beating with a stick those fellow laborers who did not follow the strict rules imposed by the bureaucratic state. In the same scene in the tomb of Djehutyhotep, two workers are shown watering trees. These workers are probably among those buried in non-elite pit graves in Fadrus. An inscription in the middle of the scene divides Djehutyhotep and his followers from the workers performing their duties. The fragmentary text says: “open (for me)… for the ka of the great of Teh[khet]… Ruiu…” (Säve-Söderbergh 1960, p. 42).

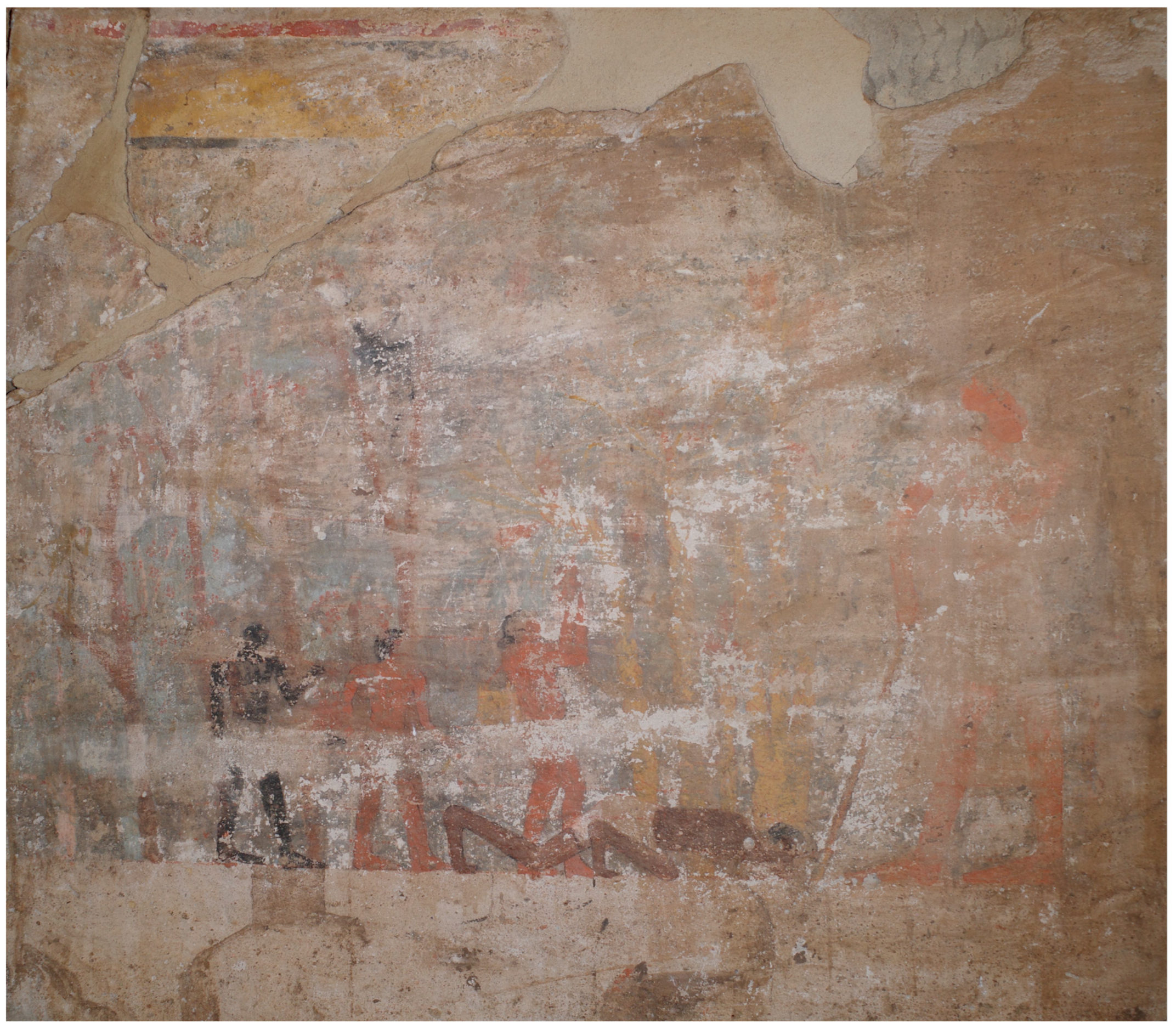

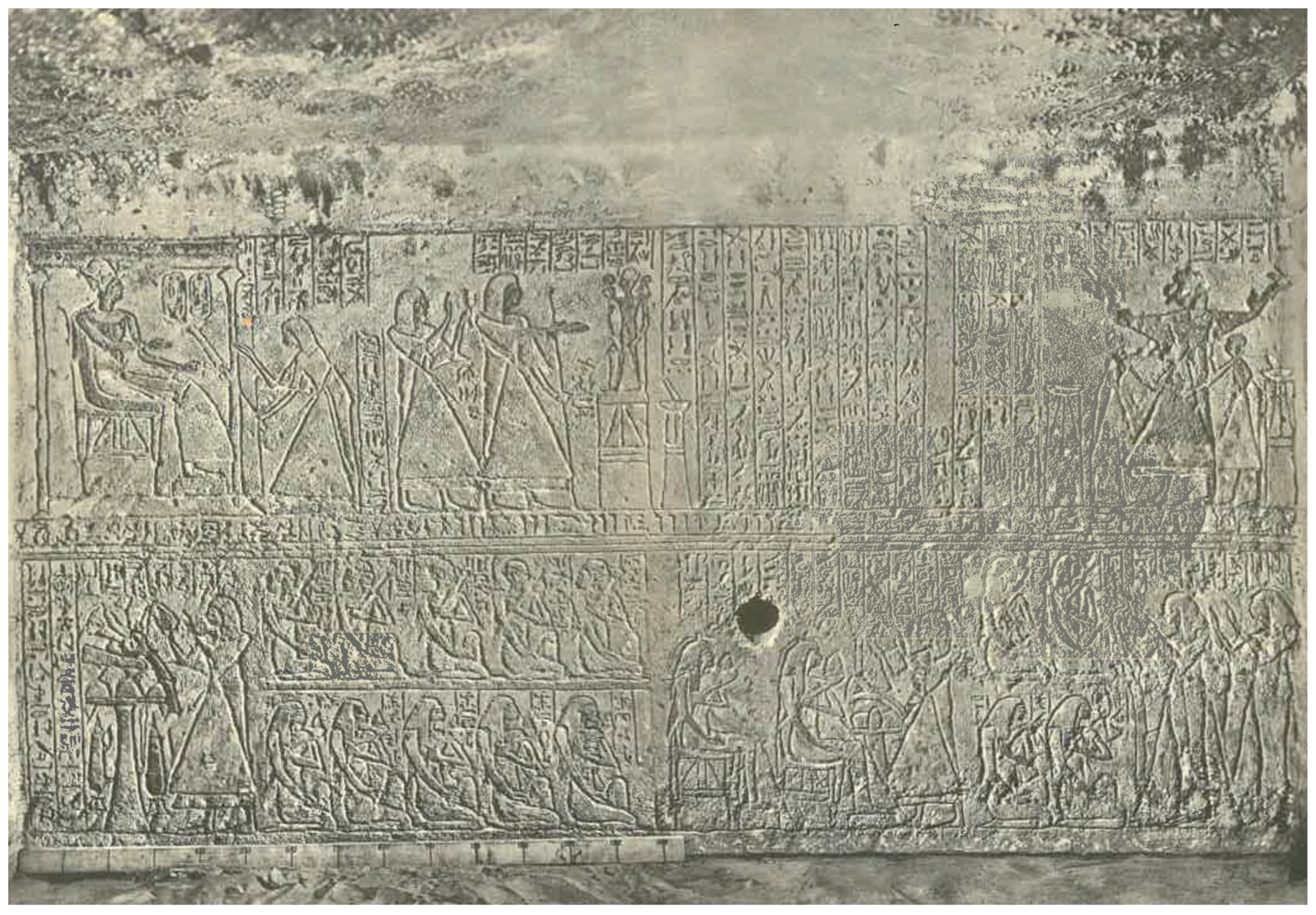

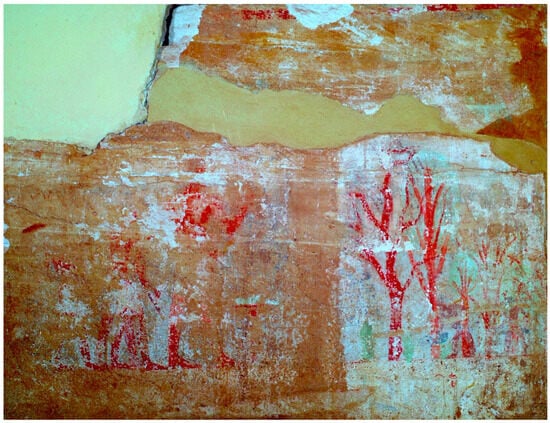

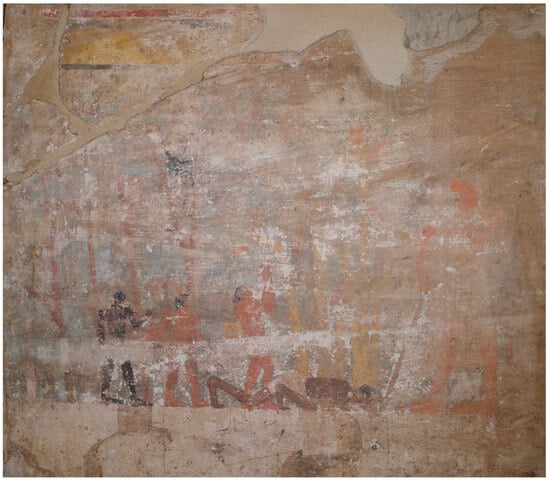

Figure 5.

An inspection of workers scene on the northwest wall of the tomb of Djehutyhotep, enhanced with DStretch. Djehutyhotep, who is followed by two lower officials, is shown recording the activities performed by the workers, who are shown watering trees. Photo by R. Lemos. Courtesy of the Sudan National Museum.

On the west side of the north wall, the inspection of workers motif continues (Figure 6). Djehutyhotep is once again depicted standing much taller than his workers. He is shown holding a staff, which was a usual symbol of authority and power in Theban tombs. In Theban Tomb 69, a standing Menna is also shown inspecting workers while holding his staff (Wilkinson 1979, p. 43). Four workers are depicted carrying out their duties. One is shown climbing a date palm tree to collect fruit. The one standing closer to Djehutyhotep carries a basket while collecting fruit from a short tree. He is followed by two standing men, one holding a bird while the other is possibly carrying two baskets supported by a stick on his back. One man, potentially a worker, is prostrated kissing the ground in front of Djehutyhotep. All the men wear Egyptian-style kilts but differences in skin color have been previously interpreted in racial terms (Säve-Söderbergh 1960; Wild 1959). The man paying homage to Djehutyhotep is black and is depicted on a much larger scale than the workers carrying out duties. This might indicate local interpretations of the usual parameters of Egyptian art or suggest that the man prostrated on the ground was someone more important than the rest of the depicted workers, potentially an individual buried in one of the Debeira undecorated rock-cut tombs.

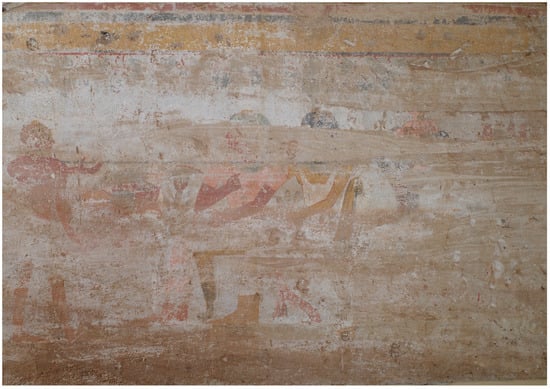

Figure 6.

An inspection of workers scene on the north wall of the tomb of Djehutyhotep. The tomb owner stands while holding a staff. A worker (?) pays respects to this master. Four workmen perform their daily farming duties. Photo by R. Lemos. Courtesy of the Sudan National Museum.

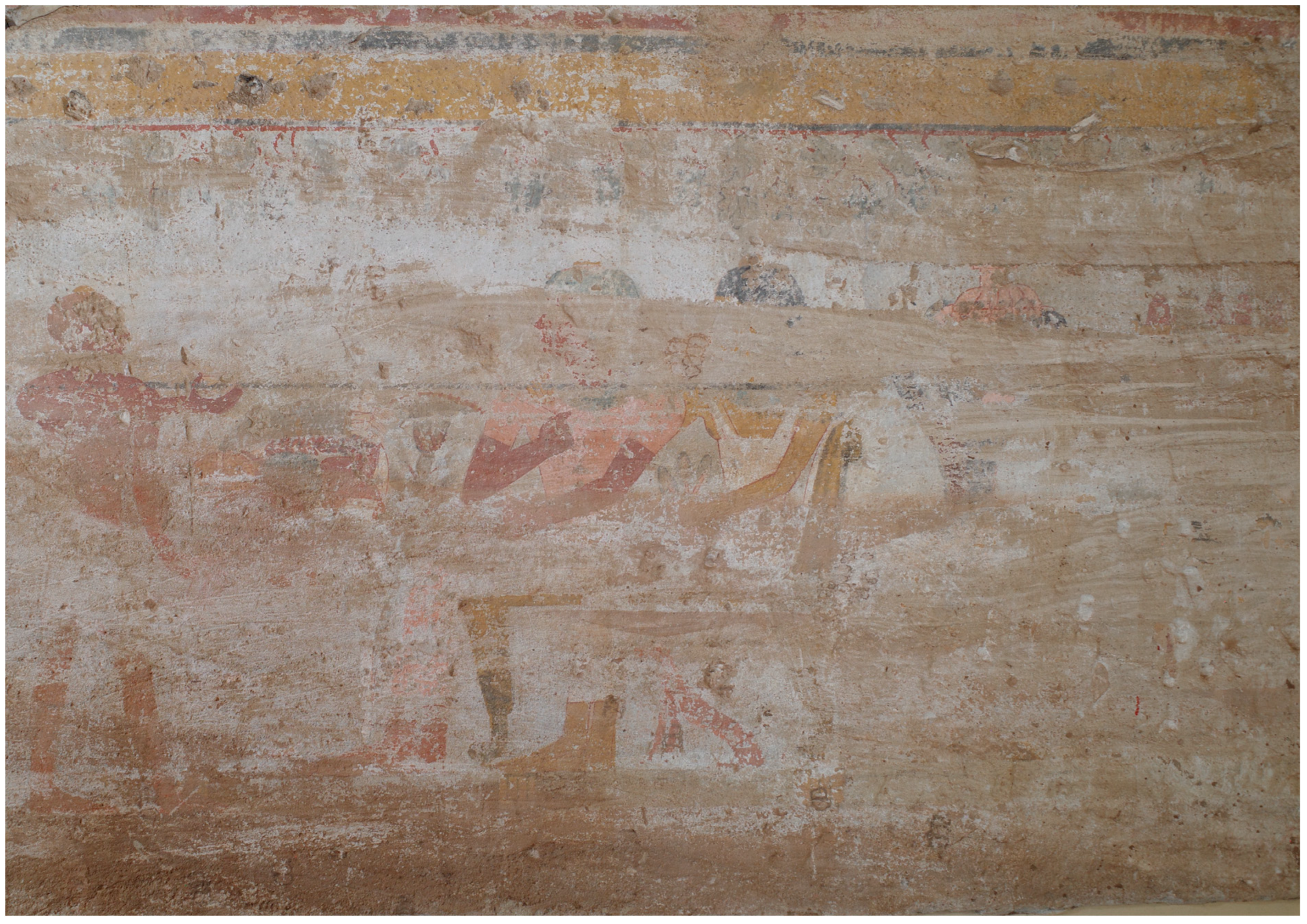

A banquet scene was painted on the east half of the north wall. In the easternmost half of the scene, Djehutyhotep and his wife, Tenetnebu, are seated in chairs in front of a full offering table (Figure 7). A dog sits below Tenetnebu’s chair. The couple is offered a drink by a servant and, behind them, another servant carries, upon his shoulders, what seems to be a Mycenean jar, similar to ceramics found throughout New Kingdom colonial Nubia (Schiller 2018). The scene continues westwards and includes musicians playing drums, the flute and clapping hands (Figure 8). As previously mentioned, they likely performed local music, which would reveal the local character behind Nubian uses of Egyptian art in the New Kingdom colony. Another servant offers a drink to a seated male guest. Two other seated guests were depicted behind him. These could be members of Djehutyhotep’s family, one of which perhaps his brother, Amenemhat, who was buried across the river.

Figure 7.

The eastern half of the banquet scene on the north wall of the tomb of Djehutyhotep. The tomb owner and his wife are shown sitting down while being attended by a servant. Photo by R. Lemos. Courtesy of the Sudan National Museum.

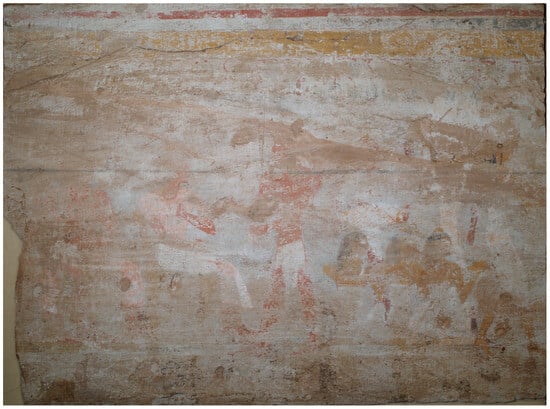

Figure 8.

The western half of the banquet scene on the north wall of the tomb of Djehutyhotep. Musicians are shown playing the flute, drums and clapping hands, while seated guests are attended to by a servant. Photo by R. Lemos. Courtesy of the Sudan National Museum.

3.2. Hekanefer

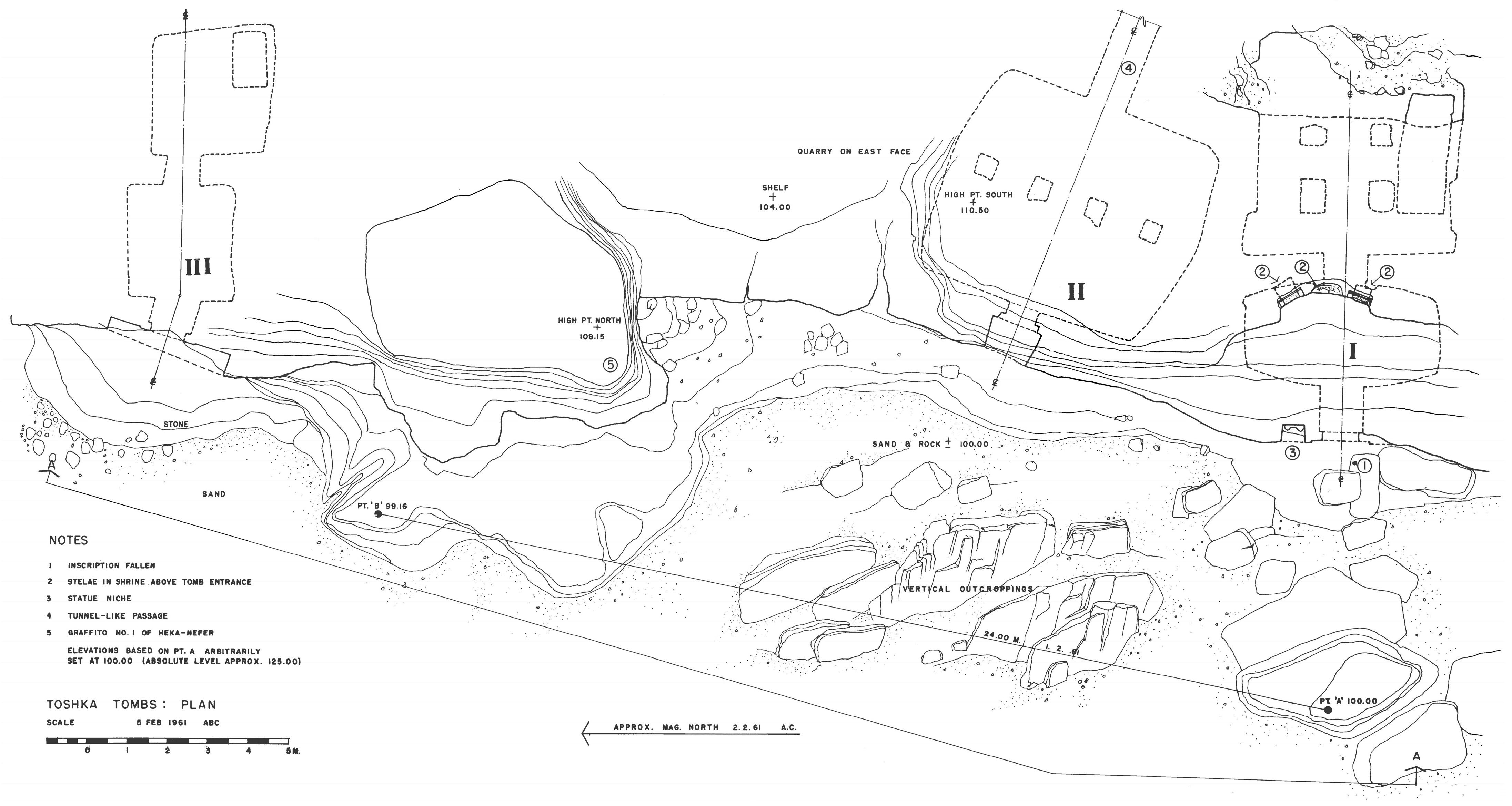

Hekanefer was “great (=chief) of Miam” during the reign of Tutankhamun (c. 1336–1327 BCE). His tomb was cut into a sandstone outcrop at Toshka West, south of Aniba (Simpson 1963). The tomb was the most significant of a group of three rock-cut tombs (Figure 9). This is because it bears a close resemblance with late 18th Dynasty Theban tombs, especially the tomb of Huy (Theban Tomb 40). In Theban Tomb 40, Hekanefer is depicted leading the Nubian tribute procession in the antechamber. Fully dressed as a Nubian, he and other two other Nubian chiefs kneel in front of the Viceroy of Kush (Davies and Gardiner 1926, plate XXVII). However, on the inscribed outer doorway of his tomb at Toshka, Hekanefer was represented as an Egyptian, similar to Djehutyhotep at Debeira (Smith 2015).

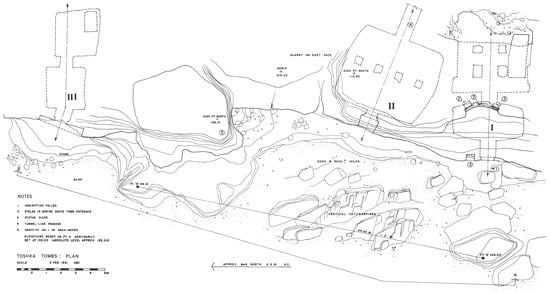

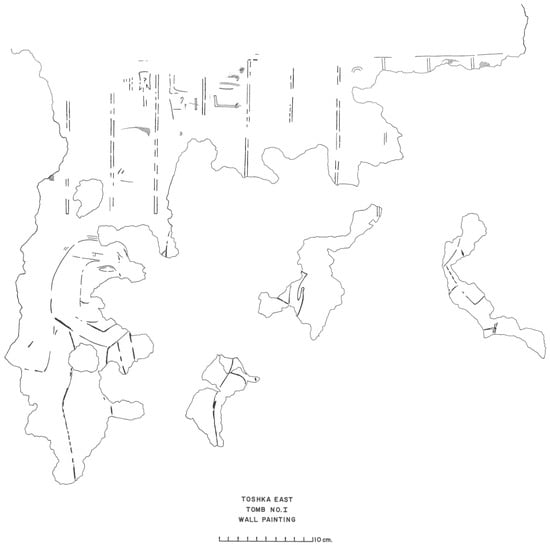

Figure 9.

Plan of the three rock-cut tombs of Toshka West. Tomb I belonged to Hekanefer; the owners of tombs II and III are not identified. After Simpson (1963, p. 4). Courtesy of the Peabody Museum, Yale.

The architecture of Hekanefer’s tomb at Toshka consists of an antechamber leading to a squared pillared hall or chapel, where four columns were located. In the pillared hall, a shaft gives access to two underground chambers. The architect seems to have used Theban Tomb 40 as a model since the plans of both tombs are extremely similar. The Theban tomb of Huy also includes a decorated antechamber, where the Nubian tribute scene was painted on its northwest wall. The squared pillared hall or chapel also included four columns. At the end of this chamber, a shrine was carved into the rock.

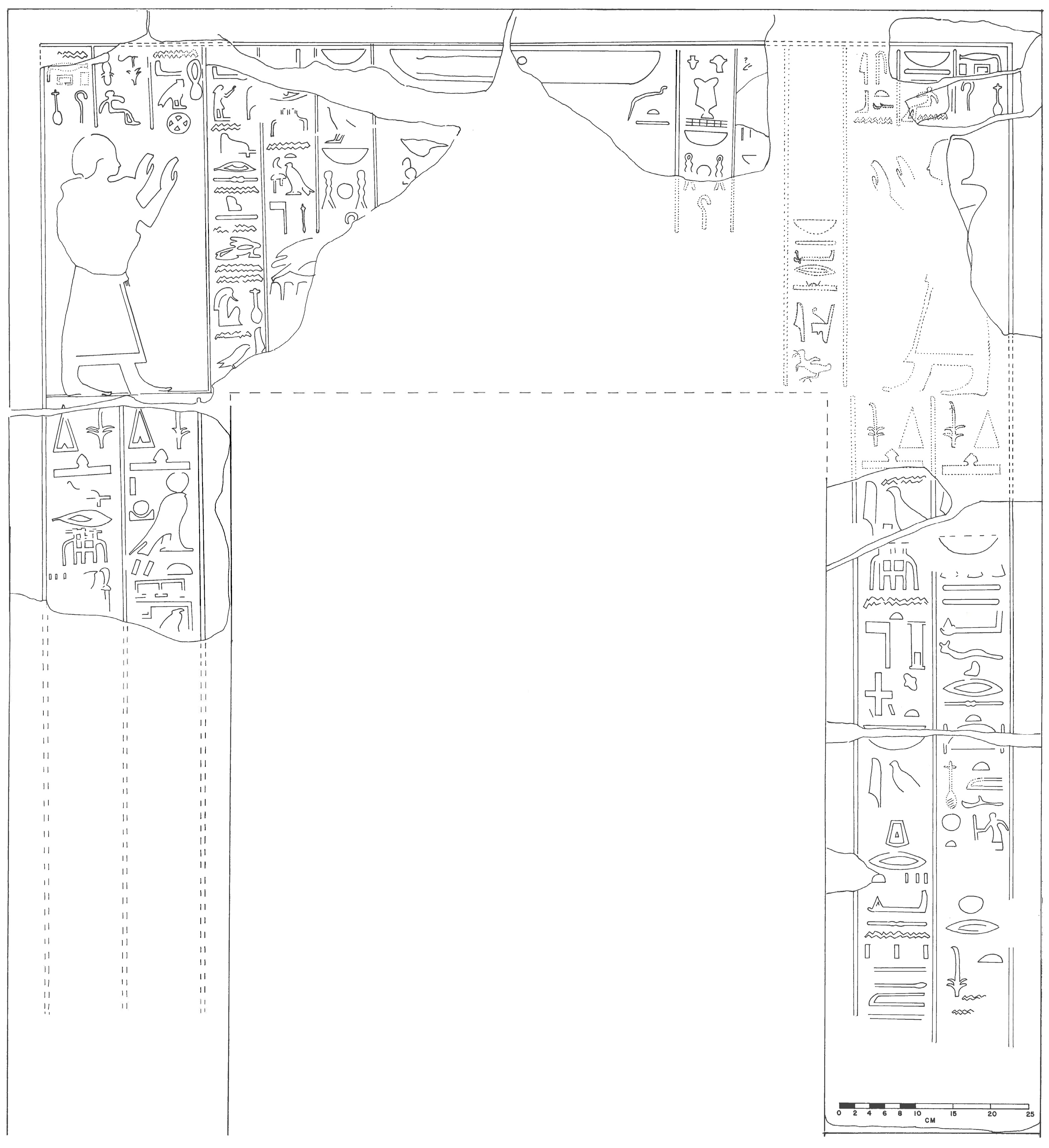

The outer doorway of the tomb of Hekanefer was decorated with carved religious texts in adoration to Osiris, Ra-Harakhty and Anubis (Figure 10). Embedded in the inscriptions, on each upper edge of the portico, there were two symmetrical figures of Hekanefer represented as an Egyptian. In the middle, remains of an offering scene, likely to the gods mentioned in the text, have been recorded. In a similar way to Theban Tomb 40, the chapel of the tomb of Hekanefer remained largely undecorated, with the antechamber remaining the focal point for decoration. The irregular sandstone walls of the antechamber were smoothed away with mud and plaster prior to receiving painted decoration, which was, at a later date, damaged and covered with another layer of mud. Therefore, the state of the wall paintings in the antechamber was highly fragmentary, although elements of the original decoration remained.

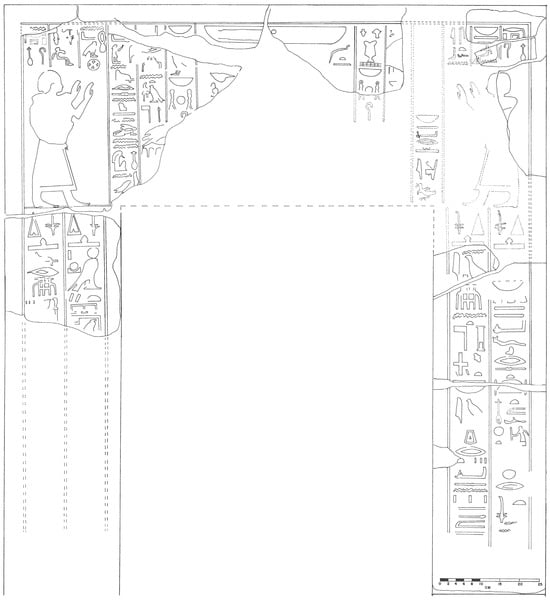

Figure 10.

The outer inscribed doorway of the tomb of Hekanefer, where he is shown as an Egyptian official. After Simpson (1963, p. 9). Courtesy of the Peabody Museum, Yale.

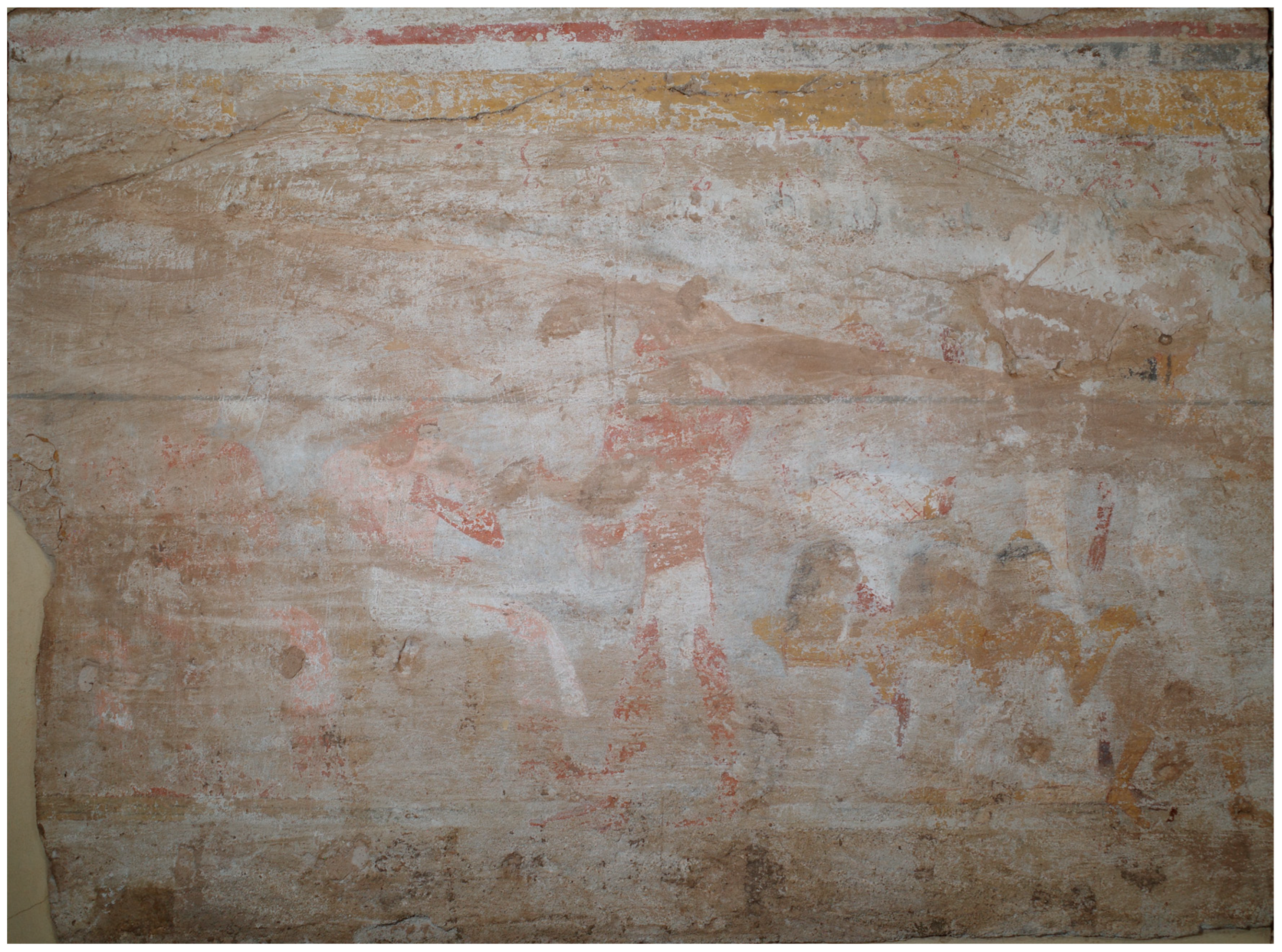

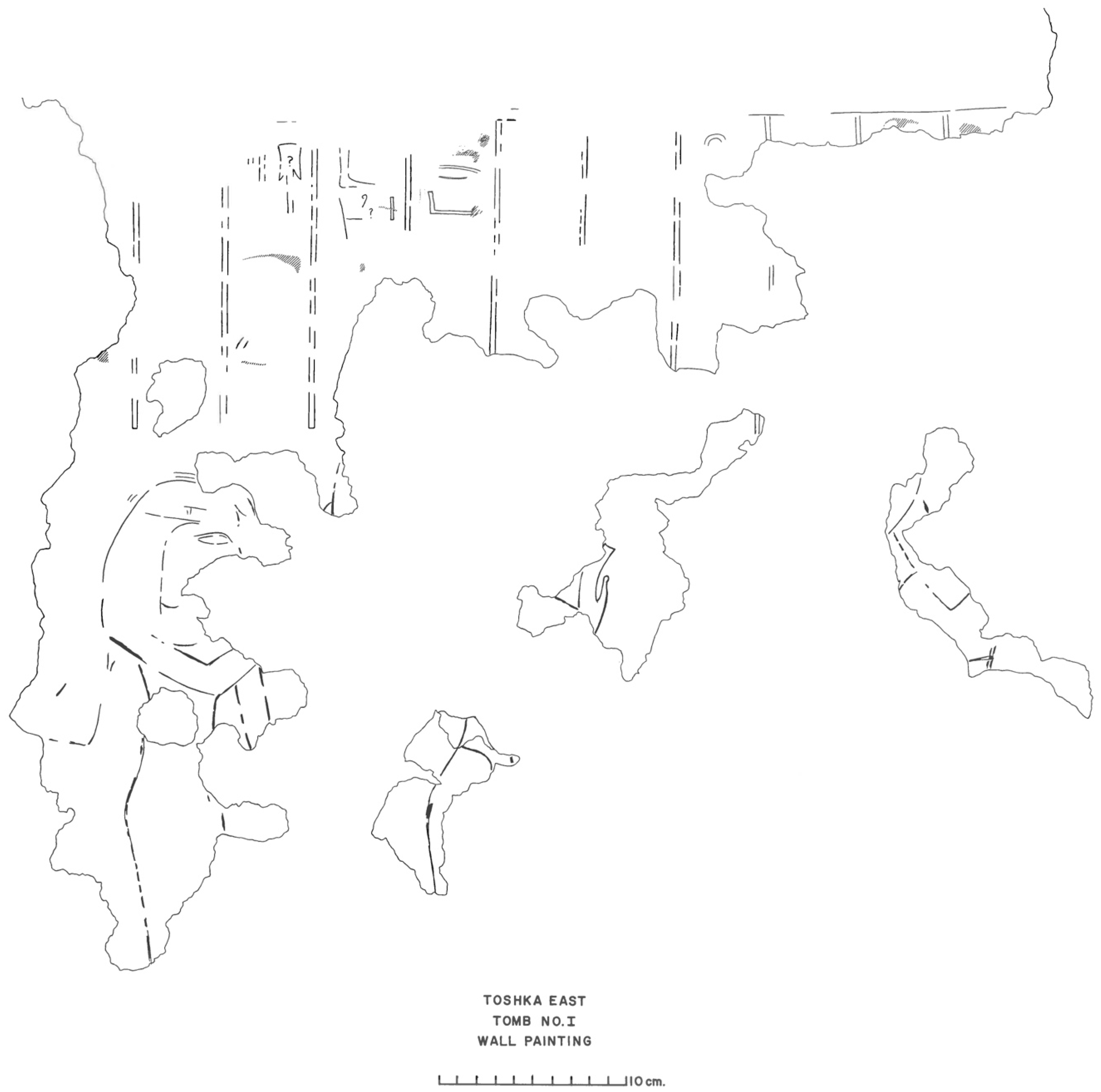

On the northern portion of the east wall, to the left of the entrance, three individuals seem to be worshiping a deity (?) (Figure 11). A woman wearing a long wig with a headband and a lotus stem on the head can be more easily recognized. She wears a long garment and broad collar, which was a symbol of status in the Nubian colony given its highly restricted character. Behind her, an individual’s elbow can be potentially recognized. In front of her and in the same position, another individual is shown standing with their arms raised in front of them in adoration. It is unclear who these three individuals worship. All represented figures are topped by vertical columns of hieroglyphs, although only a few of signs can be recognized.

Figure 11.

The preserved remains of wall paintings in the antechamber of the tomb of Hekanefer. Traces of three individuals worshiping can be recognized. After Simpson (1963, p. 12). Courtesy of the Peabody Museum, Yale.

This highly fragmentary scene alone attests to the highly skilled artisans who were employed to decorate the antechamber of the tomb of Hekanefer at Toshka. These artisans have been instinctively recognized as Theban, based on the striking similarities between New Kingdom painted tombs in Nubia and Thebes (Simpson 1963; cf. Säve-Söderbergh 1960).

The other two rock-cut tombs at Toshka West might also have featured wall paintings. Tomb III featured a geometrical ceiling which included a band of unrecognizable text. The ceiling’s pattern has been compared to Ramesside Theban tombs (Simpson 1963, p. 22), but it also bears a close resemblance to ceiling patterns from the 18th Dynasty, e.g., the tomb of Sennefer (Theban Tomb 96) (Desroches-Noblecourt et al. 1986). These tombs might have belonged to Rahotep, also chief of Miam, and Hatiuwy, likely Rahotep’s father (Simpson 1963, p. 25). An additional chief of Miam has been identified more recently in the Nubian desert (Davies 2020, p. 205). If these are the owners of the rock tombs of Toshka, it nonetheless remains difficult to establish a chronological succession for these tombs. However, the architecture of the tombs might offer clues regarding their chronology. Tomb III is architecturally closer to the mid-18th Dynasty tomb of Djehutyhotep at Debeira; Hekanefer’s tomb certainly belongs to the late 18th Dynasty; and tomb II could be later, with its architecture bearing close resemblance to the rock-cut tomb of Pennut at Aniba.

Architectural features such as doorways bearing inscriptions and representations were not widespread in Nubia. As mentioned, they appear in wealthy colonial cemeteries associated with temple-towns, especially at Aniba (Steindorff 1937, plate 25). However, the combination of these decorated features and wall paintings, sets Djehutyhotep, Hekanefer and the owners of the other two Toshka tombs apart from colonial elites generally, since wall decoration was among the rarest of tomb features in the Nubian funerary landscape of the New Kingdom.

3.3. Pennut

The Aniba landscape was not especially rugged, with its main cemetery occupying a relatively flat area (Steindorff 1937, plate 19). Cemetery S/SA was the wealthiest colonial cemetery of New Kingdom Nubia (Thill 1996; Lemos 2020). Earlier tombs comprised a mud-brick rectangular/vaulted chapel, while later chapels were built in the shape of a pyramid, in the late 18th Dynasty and Ramesside Period. Most superstructures, however, seem to have been simple rectangular demarcations of the shaft leading to various underground chambers, which were used by multiple generations as burial ground (Näser 2017).

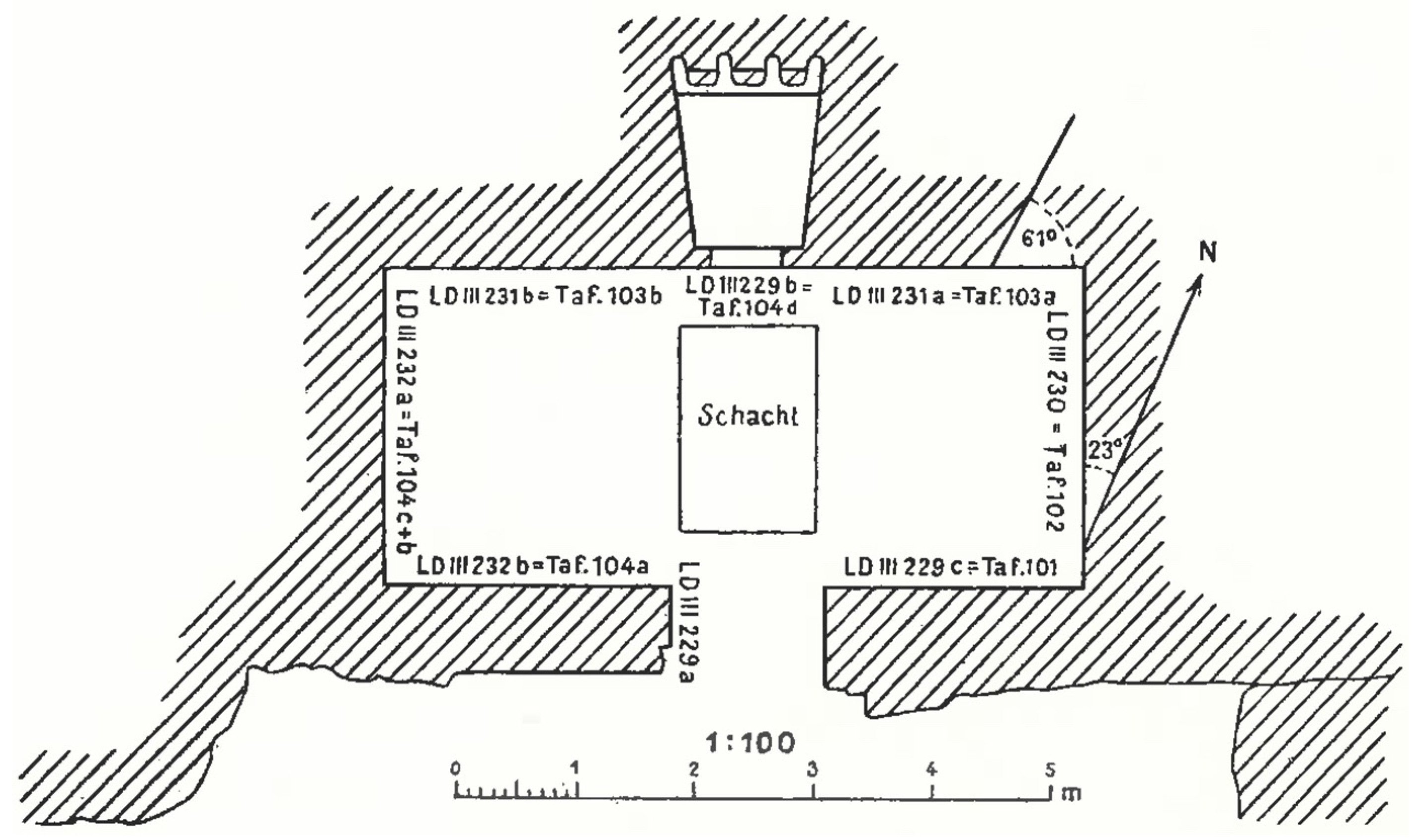

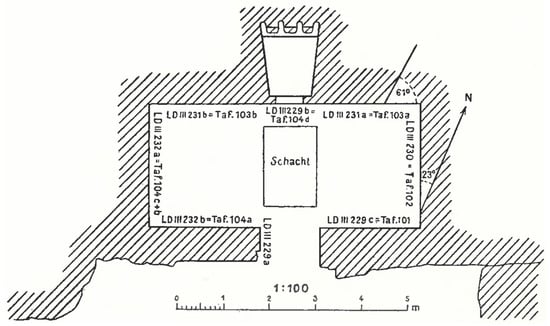

The tomb of Pennut was an exception in the Aniba funerary landscape. It was cut into a sandstone outcrop north of cemetery S/SA. An ascending ramp led to the tomb’s entrance. No outer decoration was preserved, as in the cases of Djehutyhotep and Hekanefer. In a similar way to tomb II at Toshka, the tomb of Pennut comprised an entrance leading to a large rectangular chamber from which a niche opened (Figure 12). However, instead of statues of the deceased’s family, divine statues were carved out of the rock. Despite having been left unfinished, one of the statues had its head carved in the shape of a cow’s head, which would suggest Hathor (Steindorff 1937, p. 243). The presence of three-dimensional depictions of deities is generally unusual for New Kingdom private tombs and, in the case of Pennut, would resemble temples like Abu Simbel.

Figure 12.

Plan of the tomb of Pennut, with references to Lepsius and Steindorff plates. After Steindorff (1937, p. 242).

Pennut was the Deputy of Wawat (Lower Nubia) and High Priest of the temple of Horus of Miam, the broader region where Aniba was located, during the reign of Ramses VI (c. 1143–1136 BCE). Pennut was also responsible for work at the local sandstone quarries. His entire family was connected to the temple, specifically, and the Egyptian colonial administration of Nubia, more generally (Müller 2013). His father was a priest, while his wife was a temple singer. Two of his sons were scribes, one of whom was a “scribe of the treasury of the Viceroy”, and a third son was a priest. These people and various ancestors are depicted on the walls of his tomb.

The parietal decoration of the tomb of Pennut distinguishes itself from the already restricted set of decorated rock-cut tombs in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. Instead of wall paintings, the tomb chapel is decorated with low-reliefs. Differently from the tomb of Djehutyhotep, the decorative scheme of the tomb of Pennut seems to have been carefully conceived as a narrative, with the low-relief scenes being disposed in a coherent way. The eastern (right) half of the tomb was decorated with scenes and inscriptions related to Pennut’s office and family connections, while the western (left) side of the tomb and the inner doorways to the statues’ niche contained religious scenes taken from the Book of the Dead (Steindorff 1937; Fitzenreiter 2001).

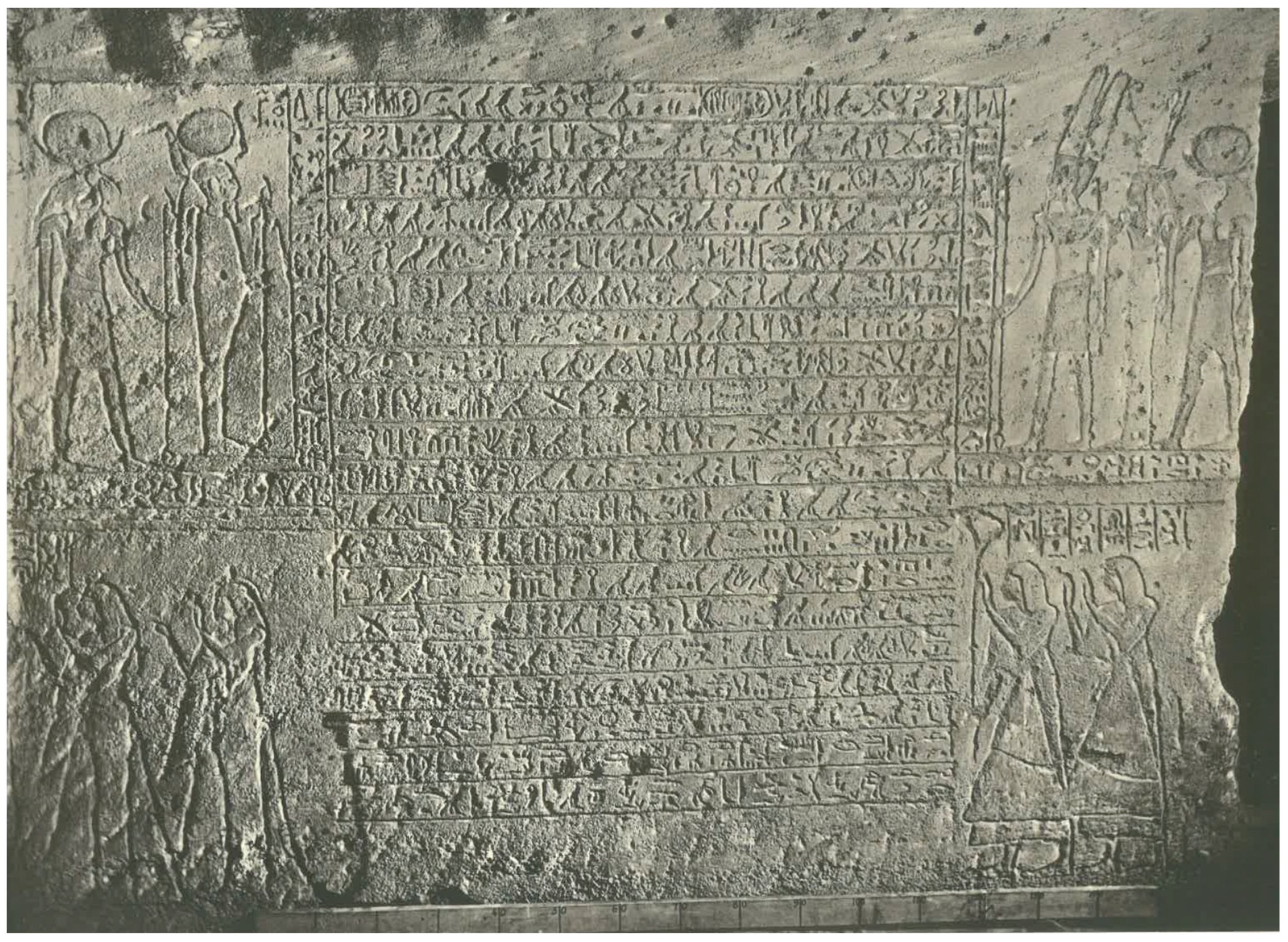

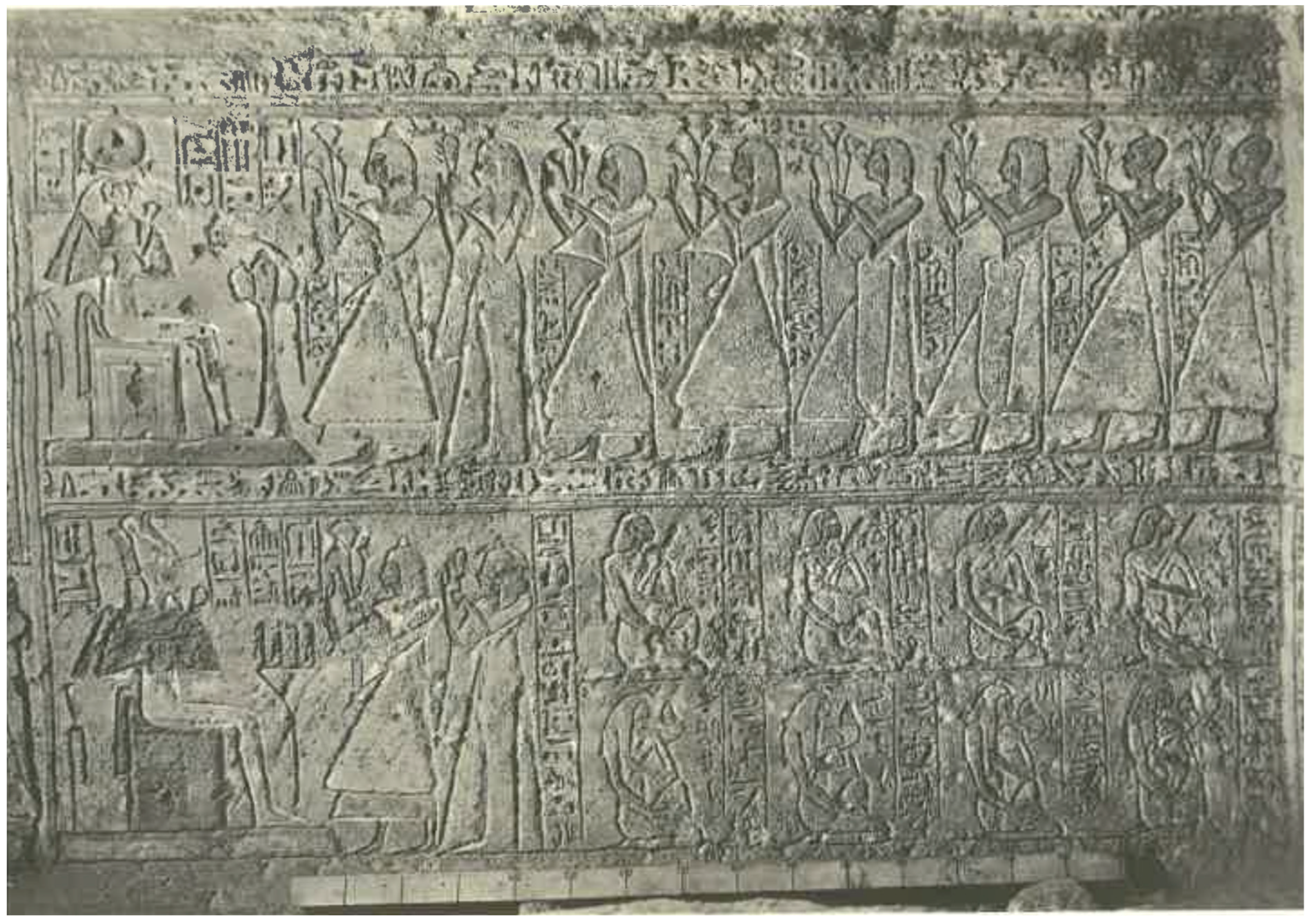

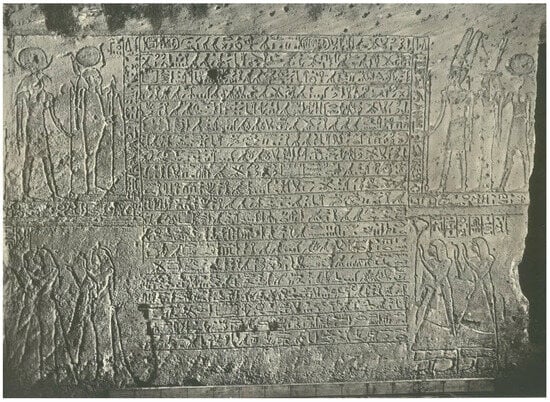

Entering the tomb, to the right, a major inscription decorates the southeast wall (Figure 13). The text mentions the erection of a statue of Ramses VI, by Pennut, at the temple of Horus, for which the tomb owner was rewarded. The king sent two silver vessels to Nubia, which were delivered to Pennut by the Viceroy of Kush. The inscription dominates most of the wall and is surrounded by Amun, Mut and Khonsu on one side, and Ptah and Thoth on the other side. Below the Theban triad, Pennut and an official called Penre, “head of the granary”, are depicted. Below Ptah and Horus, two women part of the scene on the south wall can be seen.

Figure 13.

The southeast wall of the tomb of Pennut. After Steindorff (1937, plate 101).

The reliefs on the east wall further develop the theme of the major inscription on the southeast wall (Figure 14). The Viceroy of Kush is depicted in front of the king, who orders Pennut’s reward to be delivered. Together with a state manager named Mery, the viceroy is shown revering the king’s statue. Pennut is then shown receiving the king’s reward of two silver vessels. Pennut’s position with raised arms is the same as the members of the elite receiving the “gold of honor” directly from the hands of the king, as shown in Theban and Amarna tombs (Binder 2008). It is worth noting that members of the elite in Egypt, from the late 18th Dynasty, received various gold objects directly from the king, while Pennut received silver vessels through the intermediation of the Viceroy of Kush. This could suggest that Pennut was Nubian, which would be consistently comparable with the cases of Djehutyhotep and Hekanefer. Another Ramesside reward scene from Nubia, in the temple of Beit el-Wali, shows the Viceroy of Kush, Amenemope, receiving the gold of honor in the presence of the king (Ricke et al. 1967, plate 9). The fact that officials could also be represented receiving the gold of honor directly from the king in Nubia further suggests Pennut’s lower status in comparison with Egyptian officials. The latter would receive the ‘gold of honor’ (Binder 2008), while Pennut only received silver objects as reward. The lower register of the same scene shows Pennut’s various ancestors, which is also consistent with an ancestral emphasis found in other decorated rock-cut tombs in New Kingdom Nubia.

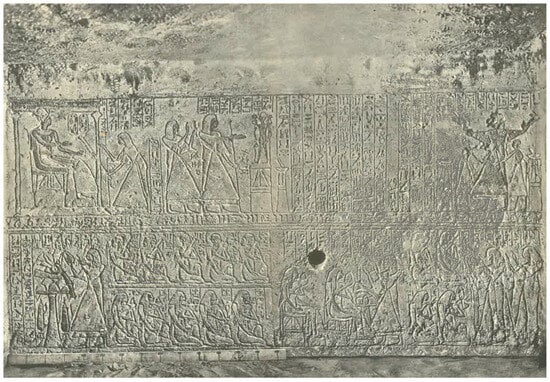

Figure 14.

The eastern wall of the tomb of Pennut. After Steindorff (1937, plate 102).

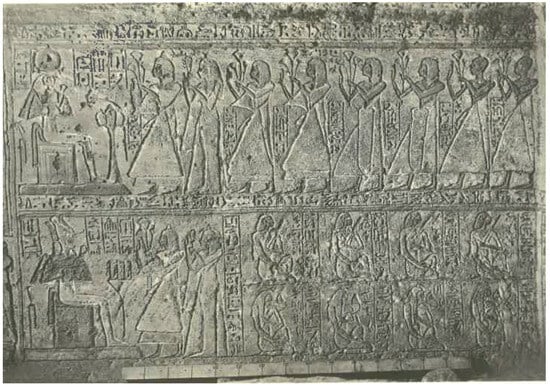

On the northeast wall, Pennut, his wife and sons were represented worshipping Ra-Harakhty and Osiris (Figure 15). The scene also includes part of the ancestors connected with the reliefs on the east wall. Like in the cases of Djehutyhotep and Hekanefer, who were part of families with long-lasting connections with the Egyptian colonial administration of Nubia, Pennut’s familial lineage was an important feature of his tomb’s decoration, which was likely key to establishing his power and position in colonial society. Despite not including an ancestral shrine with rock-carved statues of family members, the prominent role Pennut’s ancestors play in his tomb’s decoration substituted the more usual presence of ancestral statues.

Figure 15.

The northeast wall of the tomb of Pennut. After Steindorff (1937, plate 103).

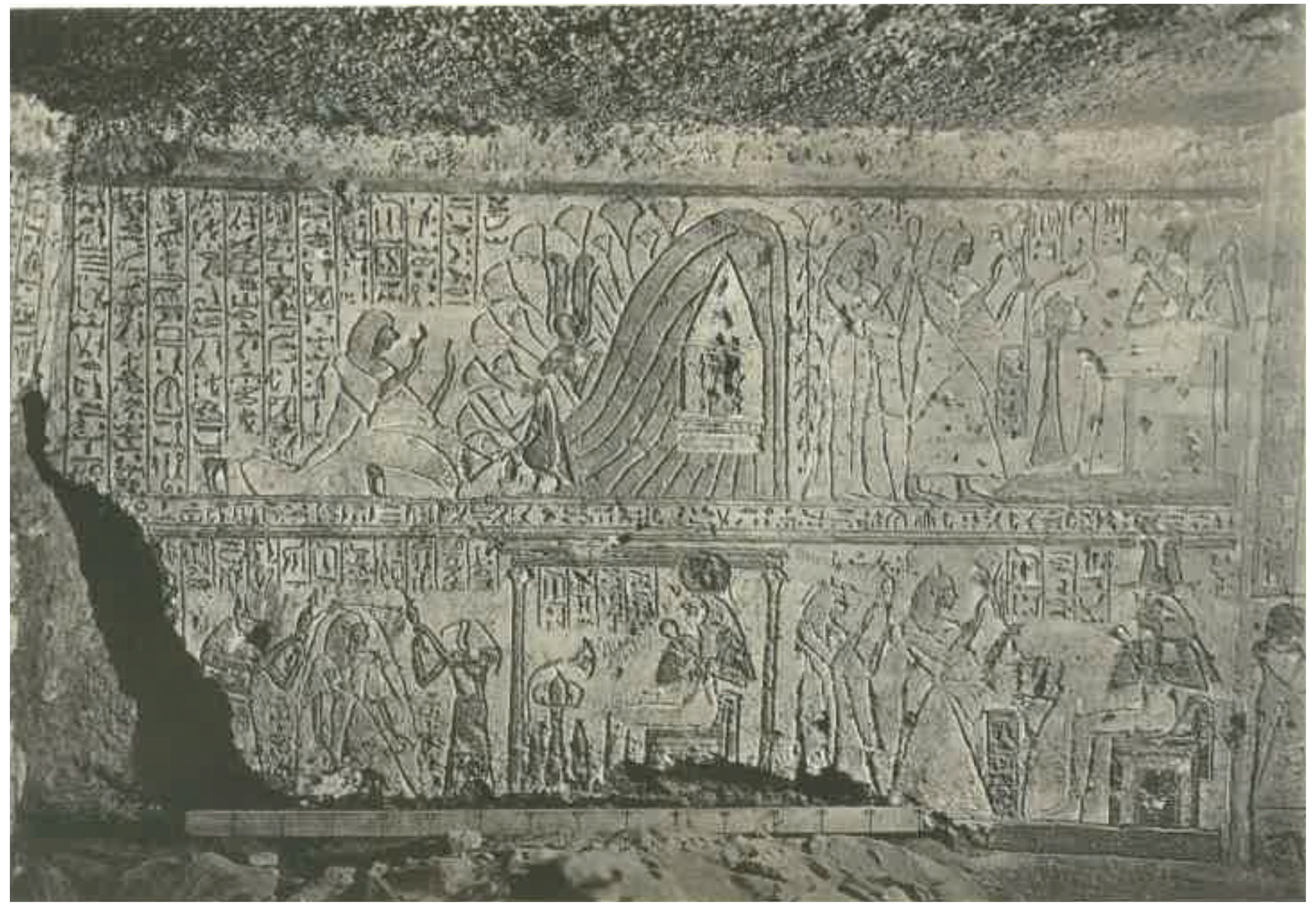

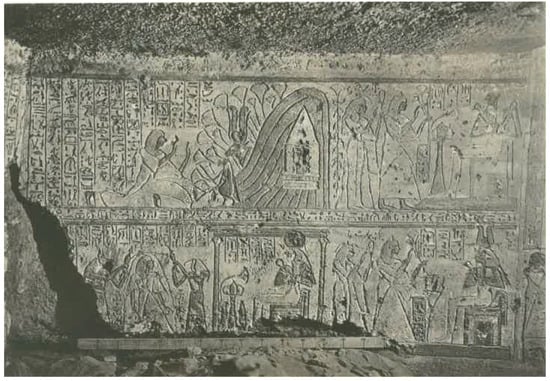

The western half of the tomb included scenes connected with various chapters of the Book of the Dead. Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, the weighting of the heart, is depicted on the southwest wall. Chapters 110—the “Field of Reeds”—and 146, which is related to the deities the deceased would meet on the way there, can be found on the west wall. Chapter 17 also appears in the inner doorway leading to the statues’ niche. These are the usual chapters of the Book of the Dead encountered in private tombs of the Ramesside Period, which demonstrates a strong connection between the tomb of Pennut and elite funerary ideals in Egypt in the same period (Einaudi 2023). On the northwest wall, Pennut is shown worshiping Hathor coming out of the (Theban) mountain, which is related to Chapter 186 of the Book of the Dead (Figure 16) (Semat 2022). The goddess Taweret appears in front of the mountain from which Hathor emerges, which is comparable to the Book of the Dead of the Theban scribe Ani (Quirke 1993, number 24). This scene demonstrates the transposition of the Theban funerary landscape to Aniba, which also contributes to communicating Pennut’s power and restricted social space in the Nubian colony.

Figure 16.

The northwest wall of the tomb of Pennut. After Steindorff (1937, plate 3).

The decorated rock-cut tomb of Nakhtmin at Dehmit could also be discussed in comparison with the tombs of Djehutyhotep, Hekanefer and Pennut. The tomb dates from the Ramesside Period and consisted of three axially organized main chambers and a small, shallow funerary chamber accessible through a slope. Two side chambers opened from the second main chamber (Fakhry 1935, p. 53; Hermann 1936, p. 5). The tomb is mostly undecorated, but remains of wall-painted decoration were recorded in the first and third main chambers (Fakhry 1935). The content of preserved scenes and texts match the usual Ramesside Book of the Dead contents found inside rock-cut tombs (Einaudi 2023).

Nakhtmin was “chief steward of the queen’s house” (Porter and Moss 1975, p. 38). In the Ramesside Period, it became more common for officials serving in close proximity to the palace to be buried in their places of origin (Grajetzki 2021, p. 24). A major scene in this tomb represents an embellished boat carrying a sarcophagus pulled by two smaller boats, one in each of two represented branches of the river (Hermann 1936, p. 7). This might suggest the transportation of the burial from the north through the Elephantine region.

The tomb of Nakhtmin has not been included in the comparison due to the owner’s close connections to the court and the Memphite area, especially in light of a votive statue mentioning him and his mother found at Heliopolis (Raue 1999, p. 223; Vandier 1958, plate CXLII1). The social space in which Nakhtmin circulated was certainly not the same as the one shaped by the experiences of Djehutyhotep, Hekanefer and Pennut. For instance, despite Pennut’s associations with the court, he only received his silver reward, a level below the “gold of honor”, through the intermediation of the Viceroy of Kush (cf. Binder 2008, p. 18).

Other rock-cut tombs dating from the New Kingdom are known in Nubia. Examples are a substantial tomb at Armina, south of the rock tombs of Miam discussed above, and the rock tomb of Bedier, near Aksha. Both were undecorated, similar to other rock tombs at Debeira East, where restricted items were excavated, despite the lack of wall paintings (Sherif 1960). For example, an imported 18th Dynasty stone shabti, inscribed for someone called Ta-Ibeshek, was found in the Bedier tomb (Vercoutter 1957, p. 111). The name Ibeshek could be connected with the ancient name of Faras (Leclant 1962, p. 122). Other examples would be the decorated rock-cut tombs at Hillat el-Arab. However, those likely date from the Pre-Napatan Period, which is reflected in their unique decorative style (Vincentelli 2006).

4. Discussion: Art, Hierarchy and Power in New Kingdom Colonial Nubia

In light of the funerary archaeological record of New Kingdom colonial Nubia, the inherent connection between art and power becomes apparent in the absolutely exceptional character of rock-cut tombs bearing wall decoration. In the 18th Dynasty, the tomb of Djehutyhotep—the earliest decorated rock-cut tomb in Sudanese Nubia—remained unique in the Debeira landscape, which included undecorated rock-cut tombs, larger tombs with mud-brick superstructures and a majority of modest burials. Not even the tomb of Amenemhat, who had the same title as Djehutyhotep, included wall paintings, despite also being partly cut into the rock and yielding exquisite inscribed material. Later in the 18th Dynasty, the three rock-cut tombs of Toshka stood out in the same way, although only the tomb of Hekanefer included preserved ritual scenes painted on the walls. Signs of a painted ceiling pattern in tomb III suggest that ritual scenes could also have been originally painted on the tomb’s walls.

One mud-brick pyramid chapel at Aniba dating from the Ramesside Period (Porter and Moss 1975, p. 78), also included smaller-scale wall paintings (Figure 17). The internal mud-brick walls of the pyramid were smoothed away with plaster before the paintings could be added onto them (Woolley 1910, p. 42). It is possible that other mud-brick tomb chapels also included wall paintings among the 157 tombs at cemetery S/SA, e.g., traces of plaster could be seen in the Ramesside pyramid chapel of tomb SA34 (Steindorff 1937, plate 29) and an “unknown tomb” bearing wall paintings has also been reported (Porter and Moss 1975, p. 80). However, these would have still been exceptional within the context of the cemetery, where only one-third of the tombs were associated with preserved superstructures that could be visited over generations (Näser 2017, p. 558).

Figure 17.

Paintings on the inner walls of the Ramesside mud-brick pyramid chapel of tomb SA7. After Steindorff (1937, plate 27). The mud-brick walls were likely smoothed away with plaster and/or mud prior to receiving painted decoration. The painted scenes convey the typical Ramesside Book of the Dead-inspired content (Einaudi 2023): the judgment of the deceased before Osiris and the goddess Hathor emerging from the (Theban) mountain (Porter and Moss 1975, pp. 78–79).

The relatively higher occurrence of wall decoration in the funerary landscape of Aniba can be explained by the wealth of the community buried at the site, especially in comparison with other elite cemeteries in New Kingdom colonial Nubia (Lemos 2020). This would explain why Pennut had to decorate the walls of his tomb with low reliefs instead of paintings, as the latter would not have been sufficiently effective to establish the boundaries of the uppermost social space to which he belonged at Aniba. The situation at Aniba would further suggest that the meaning of art in New Kingdom colonial Nubia cannot be dissociated from power, since tomb wall decoration seems to have been only available to the highest social strata.

In Egypt, a wider range of elite communities would have had access to parietal decoration as a feature of their tombs, which is reflected in the varying quality and extent of wall decoration among New Kingdom Theban tombs (Kampp 1996). For instance, tombs sharing the same courtyard could manifest striking differences in terms of tomb decoration (e.g., Davies 1933). Such variation, within the elite, was not a reality in New Kingdom colonial Nubia, which reveals another aspect of major social hierarchization and struggle imposed by colonialism (Frizzo 2020). This made even the elites face difficulties accessing desired objects (Lemos 2021; Lemos and Budka 2021; Lemos forthcoming). In Nubia, overall material difficulties would have also included access to specialized artists, some of whom are known to have traveled long distances from Egypt to Nubia (Rondot 2013; Laboury and Devillers 2022).

5. Conclusions

Funerary art, here mostly understood as parietal tomb decoration, was a rare phenomenon in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. Based on a comparison of the 18th Dynasty tombs of Djehutyhotep and Hekanefer, and the 20th Dynasty tomb of Pennut, this paper aimed to demonstrate that the rarity of wall paintings and reliefs in New Kingdom Nubia was connected to the essential role played by art in the colony, namely the establishment of hierarchization, which worked as a basis for power relations to emerge in a context of major structural limitations that affected both elites and non-elites.

The exceptionality of Djehutyhotep’s tomb in the Debeira landscape matched the unique character of the three Toshka rock-cut tombs and the tomb of Pennut in the Miam and Aniba landscapes. In light of the archaeological record of each of these regions, funerary art becomes a major element of distinction that clearly defined the borders of social spaces and established essentially hierarchical relationships between different groups bearing distinctive cultural affinities in the Nubian colony of the New Kingdom.

Funding

This research was funded by the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research and the Thomas Mulvey Fund, University of Cambridge.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Kara Cooney and Alisée Devillers for inviting me to contribute to this special issue. I am also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their comments, which greatly helped improve the initial text.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Arkell, A. J. 1950. Varia Sudanica. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 36: 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinlich-Seeber, Christine, and Abdel Ghaffar Shedid. 1987. Das Grab des Userhat (TT 56). Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, Michaela. 2014. Health and Diet in Upper Nubia through Climate and Political Change—A Bioarchaeological Investigation of Health and Living Conditions at Ancient Amara West between 1300 and 800 BC. Ph.D. thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, Susanne. 2008. The Gold of Honour in New Kingdom Egypt. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1985. The social space and the genesis of groups. Theory and Society 14: 723–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budka, Julia, Johannes Auenmüller, Cajetan Geiger, Rennan Lemos, Andrea Stadlmayr, and Marlies Wohlschlage. 2021. Tomb 26 on Sai Island: A New Kingdom Elite Tomb and Its Relevance for Sai and Beyond. Leiden: Sidestone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina de, and Alan Henderson Gardiner. 1926. The Tomb of Huy: Viceroy of Nubia in the Reign of Tut’Ankhamūn (No. 40). London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de G. 1906. The Rock Tombs of El-Amarna, Part IV: Tombs of Penthu, Mahu, and Others. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de G. 1933. The Tomb of Nefer-Hotep at Thebes. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, W. Vivian. 2020. Securing the gold of Wawat: Pharaonic inscriptions in the Sudanese-Nubian Eastern Desert. In Travelling the Korosko Road: Archaeological Exploration in Sudan’s Eastern Desert. Edited by W. Vivian Davies and Derek A. Welsby. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 185–220. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarrais, Elizabeth, and Timothy Earle. 2017. Collective Action Theory and the dynamics of complex societies. Annual Review of Anthropology 46: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane, Michel Duc, Eva Eggebrecht, Fathy Hassanein, Marcel Kurz, and Monique Nelson. 1986. Sen-nefer: Die Grabkammer des Burgermeisters von Theben. Mainz am Rhein: Philip von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, David, ed. 2020. The Archaeological Survey of Sudanese Nubia, 1963–69. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Einaudi, Silvia. 2023. The Book of the Dead in tombs. In The Oxford Handbook of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Edited by Rita Lucarelli and Martin Andreas Stadler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 231–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhry, Ahmed. 1935. The tomb of Nakht-min at Dehmît. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 35: 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzenreiter, Martin. 2001. Innere Bezüge und äußere Funktion eines ramessidischen Felsgrabes in Nubien—Notizen zum Grab des Pennut (Teil I). In Begegnungen: Antike Kulturen im Niltal. Festgabe für Erika Endesfelder, Karl-Heinz Priese, Walter Friedrich Reinecke, and Steffen Wenig. Edited by Caris-Beatrice Arnst, Ingelore Hafemann and Angelika Lohwasser. Leipzig: Wodtke und Stegbauer, pp. 131–59. [Google Scholar]

- Frizzo, Fábio. 2020. Imperialismo, Estado e hierarquização social na Baixa Núbia durante o Reino Novo Egípcio (1550-1070 a. C.). Revista de História 179: a01619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajetzki, Wolfram. 2021. The Archaeology of Egyptian Non-Royal Burial Customs in New Kingdom Egypt and Its Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, Alfred. 1936. Das Grab eines Nakhtmin in Unternubien. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo 6: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkel, Friedrich W. 1978. Exodus from Nubia. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kampp, Friederike. 1996. Die Thebanische Nekropole. Zum Wandel des Grabgedankens von der XVIII. Bis zur XX. Dynastie. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2012. Tracking ancient Egyptian artists, a problem of methodology. The case of the painters of private tombs in the Theban necropolis during the Eighteenth Dynasty. In Art and Society: Ancient and Modern Contexts of Egyptian Art. Paper presented at International Conference Held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary, 13–15 May 2010. Edited by Katalin Anna Kóthay. Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri, and Alisée Devillers. 2022. The ancient Egyptian artist: A non-existing category? In Ancient Egyptian Society: Challenging Assumptions, Exploring Approaches. Edited by Danielle Candelora, Nadia Ben-Marzouk and Kathlyn M. Cooney. London: Routledge, pp. 163–81. [Google Scholar]

- Leclant, Jean. 1962. Fouilles et travaux au Soudan, 1955–1960. Orientalia 31: 120–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, Rennan. 2020. Material culture and colonization in ancient Nubia: Evidence from the New Kingdom cemeteries. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Edited by Claire Smith. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, Rennan. 2021. Heart scarabs and other heart-related objects in New Kingdom Nubia. Sudan & Nubia 25: 252–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, Rennan. forthcoming. Beyond cultural entanglements: Experiencing the New Kingdom colonization of Nubia ‘from below’. In New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia. Edited by Solange Ashby and Aaron J. Brody. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, pp. 53–94.

- Lemos, Rennan, and Julia Budka. 2021. Alternatives to colonization and marginal identities in New Kingdom colonial Nubia (1550–1070 BCE). World Archaeology 53: 401–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, Rennan, Kate Fulcher, Ikhlas Abdllatief, Ludmila Werkström, and Emma Hocker. 2023. Reshaping Egyptian funerary ritual in colonized Nubia? Organic characterization of unguents from mortuary contexts of the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 15: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minault-Gout, Anne, and Florence Thill. 2012. Saï II: Le Cimetière des Tombes Hypogées du Nouvel Empire SAC5. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Morkot, Robert. 2013. From conquered to conqueror: The organization of Nubia in the New Kingdom and the Kushite administration of Egypt. In Ancient Egyptian Administration. Edited by Juan Carlos Moreno García. Leiden: Brill, pp. 911–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, Rosalind. 1950. The ancient name of Serra (Sudan). Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 36: 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Ingeborg. 2013. Die Verwaltung Nubiens im Neuen Reich. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Näser, Claudia. 2017. Structures and realities of the Egyptian presence in Lower Nubia from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom: The Egyptian cemetery S/SA at Aniba. In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions. Edited by Neal Spencer, Anna Stevens and Michaela Binder. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 557–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nordström, Hans-Åke. 2014. The West Bank Survey from Faras to Gemai. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Pereyra, María Violeta, and Mariano Bonanno. 2024. Network of symbolisms in a private tomb in ancient Thebes. In Archaeology of Symbols. ICAS I: ICAS I: Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Archaeology of Symbols. Edited by Guido Guarducci, Nicola Laneri and Stefano Valentini. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 263–74. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind Louisa Beaufort Moss. 1975. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings. VII. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Oxford: Griffith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, Stephen. 1993. Owners of Funerary Papyri in the British Museum. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raue, Dietrich. 1999. Heliopolis und das Haus des Re: Eine Prosopographie und ein Toponymim Neuen Reich. Berlin: Achet Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ricke, Herbert, George R. Hughes, and Edward F. Wente. 1967. The Beit El-Wali Temple of Ramesses II. Chicago: Oriental Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Rondot, Vicent. 2013. Le long voyage du dessinateur Neb depuis Elkab jusqu’à Sabo en Nubie soudanaise. In L’art du Contour. Le Dessin dans l’Égypte Ancienne. Edited by Guillemette Andreu-Lanoë. Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, pp. 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbahy, Lisa. 2018. Moving pictures: Context of use and iconography of chariots in the New Kingdom. In Chariots in Ancient Egypt: The Tano Chariot, a Case Study. Edited by André J. Veldmeijer and Salima Ikram. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 120–49. [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny. 1960. The paintings from the tomb of Djehuty-hetep at Debeira. Kush VIII: 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny. 1991. Teh-khet: The cultural and sociopolitical structure of a Nubian princedom in Tuthmoside Times. In Egypt and Africa: Nubia from Prehistory to Islam. Edited by W. Vivian Davies. London: British Museum Press, pp. 186–94. [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny, and Lana Troy. 1991. New Kingdom Pharaonic Sites: The Finds and the Sites. Partille: Paul Åström. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff Giorgini, Michela. 1971. Soleb II: Les Nécropoles. Florence: Sansone. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, Birgit. 2018. Aegean pottery in Nubia: Imports and imitations. Cahiers de la Céramique Égyptienne 11: 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Semat, Aude. 2022. Depicting the mountain and the tomb at Thebes. Ancient images of the Theban necropolis. In Deir El-Medina through the Kaleidoscope. Proceedings of the International Workshop, Turin 8th-10th October 2018. Edited by Susanne Töpfer, Paolo Del Vesco and Federico Poole. Turin: Franco Cosimo Panini, pp. 701–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, Nigm ed Din Mohamed. 1960. Clearance of two tombs at Debeira East. Kush VIII: 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, William Kelly. 1963. Heka-Nefer and the Dynastic Material from Toshka and Armina. New Haven: Peboady Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Stuart Tyson. 2003. Wretched Kush: Ethnic Identities and Boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Stuart Tyson. 2015. Hekanefer and the Lower Nubian princes: Entanglement, double identity or topos and mimesis? In Fuzzy Boundaries: Festschrift für Antonio Loprieno II. Edited by Hans Amstutz, Andreas Dorn, Matthias Müller, Miriam Ronsdorf and Sami Uljas. Hamburg: Widmaier Verlag, pp. 767–79. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Stuart Tyson. 2021. The Nubian experience of Egyptian domination during the New Kingdom. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Edited by Geoff Emberling and Bruce Williams. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 369–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Stuart Tyson, and Michele R. Buzon. 2014. Identity, commemoration, and remembrance in colonial encounters: Burials at Tombos during the Egyptian New Kingdom Nubian empire and its aftermath. In Remembering the Dead in the Ancient Near East: Recent Contributions from Bioarchaeology and Mortuary Archaeology. Edited by Benjamin W. Porter and Alexis T. Boutin. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, pp. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Stuart Tyson, and Michele R. Buzon. 2017. Colonial encounters at New Kingdom Tombos: Cultural entanglements and hybrid identity. In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions. Edited by Neal Spencer, Anna Stevens and Michaela Binder. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 615–30. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Kate. 2019. New Kingdom Tombs in Lower and Upper Nubia. In Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Edited by Dietrich Raue. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 541–66. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Neal, Anna Stevens, and Michaela Binder. 2014. Amara West: Living in Egyptian Nubia. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Staring, Nico. 2023. The Saqqara Necropolis through the New Kingdom: Biography of an Ancient Egyptian Cultural Landscape. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steindorff, Georg. 1937. Aniba II. Glückstadt: J. J. Augustin. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Anna. 2017. Death and the city: The cemeteries of Amarna in their urban context. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 28: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, Thabit Hassan. 1957. The tomb of Djehuty-hetep (Tehuti Hetep), prince of Serra. Kush V: 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Thill, Fl. 1996. Coutumes funeráires égyptiennes en Nubie au Nouvel Empire. Revue d’Égyptologie 47: 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, László. 2009. Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region between Ancient Nubia and Egypt 3700 BC–500 AD. Brill: Leiden. [Google Scholar]

- Trigger, Bruce G. 1976. Nubia under the Pharaohs. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- van Pelt, W. Paul. 2013. Revising Egypto-Nubian relations in New Kingdom Lower Nubia: From Egyptianization to cultural entanglement. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 23: 523–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandier, Jacques. 1958. Manuel D’archéologie Égyptienne III. Paris: Éditions A. et J. Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Vercoutter, Jean. 1957. Archaeological survey in the Sudan, 1955–1957. Sudan Notes and Records 38: 111–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, André. 1977. La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Sudanaise) 5. Paris: CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Vincentelli, Irene. 2006. Hillat el-Arab. The Joint Sudanese-Italian Expedition in the Napatan Region, Sudan. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, Max. 1933. Stilentwickelung der thebanischen Beamtengräber. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Instituts für Ägyptische Altertumskunde in Kairo 4: 38–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, Henri. 1959. Une danse nubienne d’époque pharaonique. Kush VII: 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Charles K. 1979. Egyptian wall paintings: The Metropolitan Museum’s collection of facsimiles. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 36: 2–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, Charles Leonard. 1910. The Eckley B. Coxe Expedition: Egyptian section. The Museum Journal 1: 42–48. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).