Abstract

Recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement in the context of terrorist groups remain underexplored in a comprehensive, integrated manner. This systematic review is a pioneering effort to address this gap by synthesizing existing knowledge, aiming to analyze the entire trajectory of individuals within terrorist organizations—from recruitment to disengagement—thereby providing a foundation for guiding future research. Conducted through meticulous searches across three major databases—Academic Search Complete, SCOPUS, and the Web of Science Collection—our review followed a pre-registered protocol, ultimately identifying seven studies that met the inclusion criteria. These studies encompass qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research published in peer-reviewed journals, and are accessible in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Our analysis reveals the critical influence of push and pull factors across these phases, emphasizing that retention is predominantly shaped by individual roles within terrorist organizations and the impact of governmental amnesty policies. Diverging from existing segmented approaches, our findings highlight the importance of examining recruitment, retention, and disengagement as a continuous process to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of terrorist involvement. The insights derived from this study offer valuable guidance for counterterrorism strategies, suggesting interventions targeting recruitment, retention, and recidivism by addressing these crucial factors throughout the entire lifecycle of involvement in terrorist organizations.

1. Introduction

Terrorism poses a complex global challenge, impacting multiple nations and leveraging online platforms to form groups and operate remotely (Saini and Bansal 2021). The lack of consensus on definitions of terms such as “radicalism” and “extremism” underscores the difficulty in understanding and effectively addressing the root causes of these phenomena (Borum 2011).

However, the existing literature lacks investigations that address in an integrated manner the processes of the recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement of individuals within terrorist groups, despite the importance of understanding the complete cycle of terrorist involvement to formulate more effective counterterrorism strategies.

A shift towards focusing on violent radicalism has led to a deeper investigation into its origins. European Union member countries, for instance, have employed the concept of radicalization to understand why youth join terrorist groups (Breidlid 2021). This complexity in identifying the reasons behind radicalization complicates efforts to effectively counter global terrorism threats (Lia 2004; Yayla 2007). An impartial analysis of the causes of terrorism, considering all the relevant factors in an integrated manner, is essential. Understanding the processes underpinning terrorist acts is crucial for developing effective counterterrorism strategies (Sageman 2004). This understanding also aids in identifying factors that contribute to radicalization and, consequently, formulating strategies to prevent individuals from turning to terrorism (Schmid 2013).

Contrary to common assumptions, individuals who join terrorist groups come from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and literacy levels, not solely from disadvantaged backgrounds or with low education (Lia 2004). Sageman (2004) notes that the process of joining terrorist groups predominantly involves young men, although women, in smaller numbers, also participate in these organizations. Hoffman (2006) emphasizes that terrorism is not confined to rich or poor countries; it occurs in modern, industrialized contexts and less developed areas. Terrorism can emerge during periods of transition or development, in former colonies and independent states, as well as in consolidated democracies or less democratic regimes (Hoffman 2006).

Stern and Berger (2015) argue that understanding the phenomenon of terrorism requires acknowledging this diversity of contexts. The authors stress that the heterogeneity of terrorism, with its various forms and specific causes, complicates the task of generalizing terrorism. Terrorism, as a crime, possesses distinctive characteristics, setting it apart from other criminal activities. Its extreme nature is manifested through the indiscriminate use of violence against civilians. Unlike most crimes committed by individuals, terrorism is typically supported by groups and motivated by political, social, or religious reasons (Agnew 2010).

The motivation for involvement and disengagement from terrorist groups is associated with both push and pull factors (Jones 2017). Push factors are linked to political, economic, and social issues, fostering a sense of injustice and discrimination. Conversely, pull factors create a sense of identification with a cause, group, or opportunity for heroism (Jones 2017).

1.1. Recruitment and Radicalization Process

Governments and their security agencies face significant pressure to detect and disrupt terrorists in the early stages of radicalization. In response, they encourage analysts to delineate the radicalization process, identify the social, economic, and political contexts that produce violent extremists, and understand the psychological states that lead ordinary individuals to engage in terrorist activities (Hafez and Mullins 2015).

Recruitment involves persuading individuals to engage in terrorist acts, either by directly committing offenses or by joining organizations that facilitate terrorist activities (Ozeren et al. 2018). This process can occur in various forms, commonly when a recruiter identifies a suitable candidate and convinces them to join the terrorist cause (Weisburd et al. 2022).

Recruitment strategies in terrorist organizations vary based on their ideological foundations, location, and goals (Yayla 2021). Recruits often initiate contact with recruiters, either randomly or due to a targeted interest in joining. Recruitment depends on the synchronization of recruiting efforts and prospective candidates at the right time and place. Various locations, including coffee shops, parks, religious institutions, and online platforms, serve as points of contact for at-risk individuals (Weisburd et al. 2022). Terrorist groups actively seek potential recruits, focusing on individuals with vulnerabilities and grievances that make them susceptible to recruitment (Ozeren et al. 2018).

Understanding the recruitment process is crucial for disrupting the continuity of terrorist networks. Effective intervention by authorities necessitates a comprehensive understanding of recruitment mechanisms, which could significantly impact the future capabilities of terrorist organizations if successfully disrupted (Yayla 2021). Despite past efforts to identify a “terrorist personality,” current research emphasizes characterizing the radicalization process, even without a conclusive model. Grievances, networks, and ideologies constitute parts of the radicalization model puzzle, yet a comprehensive roadmap for integrating these pieces remains elusive (Hafez and Mullins 2015).

Recruitment processes aim to reach and persuade as many individuals as possible to secure the organization’s future (Yayla 2021). These processes extend across various locations where potential recruits may be found, such as cafes, religious institutions, parks, and the Internet (Weisburd et al. 2022). Al-Qaeda, for instance, has detailed manuals outlining effective recruitment strategies (Yayla 2021). Recruitment may not always seek militants; it can also aim to broaden support by providing logistics and specialized knowledge (Yayla 2021).

In contrast to recruitment, radicalization involves behavioral and ideological transformations that legitimize violence for political goals (Ashour 2009). The transition from radicalization to terrorism encompasses three stages: the search for significance, the act of violence or terrorism, and the formation of convictions justifying violence (Kruglanski et al. 2014). Terrorists initially become extremists in their beliefs and, for various reasons, choose to pursue their goals through violence. This is logical, as terrorists are no more irrational or psychotic than the general population. All forms of action, from the least to the most violent, result from rational thought processes (Neumann 2013).

Radicalization is often defined as the adoption of an extremist worldview, rejected by mainstream society, that considers violence a legitimate means to promote social or political change. The consensus view generally converges on three fundamental elements to define radicalization: it is typically a gradual process; it involves socialization into an extremist belief system; and it prepares the ground for the possibility of violence (Hafez and Mullins 2015). The radicalization process spans individual, emotional, cognitive, social, and media dimensions (Leistedt 2016). Depending on what is considered acceptable, adopting certain beliefs or behaviors may be seen as radicalization. However, the term ‘radical’ is not always linked to extremism, nor does it necessarily imply a ‘problem’ needing study and solution (Neumann 2013).

While radicalization does not necessarily lead to terrorism, it serves as a crucial step toward violence, providing fertile ground for violent extremism and terrorism (Yayla 2021). Factors such as clashes with defense forces may motivate individuals with radical ideals to join terrorist groups, often with the support of friends or family (Kruglanski et al. 2014).

1.2. Affiliation and Disengagement in Terrorism Organization

Individuals moving from radicalization to terrorist groups typically seek moral justifications, viewing terrorism as a justified response to perceived injustices (Kruglanski et al. 2014). Joining a terrorist organization involves officially affiliating with a group that carries out terrorist acts, which may include active participation, financial support, training, or actions in support of the group’s political or ideological objectives through violent or intimidating means (Crenshaw 2011).

Horgan (2008) proposes that understanding an individual’s involvement in terrorist groups can be viewed as a psychological and behavioral progression comprising three phases. The initial phase involves adopting an ideology and joining a terrorist organization, endorsing the group’s goals. The next phase, engagement in terrorism, consists of two components: ongoing involvement in the group’s activities, such as attending meetings and planning and participating in actual acts of terrorism, including logistical support, propaganda dissemination, and violent acts targeting civilians or government officials. The third phase is disengagement from terrorist activities, often driven by disillusionment with the group’s objectives, personal stress, or a shift in beliefs. Disengagement typically involves gradually distancing oneself from the group and its activities. These phases depict a complex evolution that provides insight into terrorists’ actions and mindsets.

Joining a terrorist group can result from various factors, including coercion, identity-seeking, seeking prestige, and motivations for protection. Satisfaction and push–pull factors influence individuals’ decisions to either remain with or leave the group (Lachman et al. 2013). As individuals become disillusioned, pull factors such as family or stable career opportunities become more appealing. However, the process of transitioning from initial doubts to actual departure from the group is complex and may take time to unfold (Barrelle 2015).

Disengagement refers to the process by which individuals or groups cease to engage in terrorist activities. This can occur in various ways, including physically distancing oneself from the organization, ceasing to engage in terrorist acts, or disassociating ideologically from the group’s objectives and methods. It does not necessarily signify a complete rejection of the ideology or goals of the group, but rather a cessation of active involvement in terrorist activities (Horgan 2008). Disengagement involves individual change, often prompted by dissatisfaction within the organization. Pull factors, such as aspirations related to family, act as incentives for change, pulling individuals toward more conventional social roles (Giordano et al. 2002). The decision to leave terrorism is multifaceted and highly individualized (Altier et al. 2017).

Factors influencing individuals’ decisions to disengage from terrorist groups include both push and pull factors. Push factors involve negative aspects within the group that drive individuals away, such as disagreement with the group’s strategy or actions, conflicts with leaders or members, frustrations with daily tasks, and burnout. These pressures increase the likelihood of terrorists opting to disengage (Altier et al. 2017). On the other hand, pull factors are positive incentives that attract individuals toward leaving a terrorist group, such as a desire for a stable family life, career opportunities, or a longing for a peaceful existence outside of terrorism. Some terrorists may experience a combination of push and pull factors, influencing their decisions to disengage or remain with the group (Horgan 2008).

Due to limited large-scale studies on disengagement across various terrorist groups and regions, there is no clear evidence on which push or pull factors are more likely to precipitate disengagement on average within the terrorist population (Altier et al. 2017). Therefore, it is crucial to provide safe opportunities for disengaged individuals to explore their values and find new places in society to which they may want to belong. This can be facilitated through mediators, who in this case, would be other individuals with whom the person identifies at some level (Barrelle 2015).

2. Present Study

The evolving nature of terrorism, coupled with the adaptive strategies of terrorist organizations, underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of the processes of recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement within these groups. This systematic review aims to address these critical phases as interconnected elements, focusing particularly on factors that contribute to retention. Recent literature reveals a dearth of studies that examine all three phases as a cohesive process, underscoring the need for targeted research to inform effective and differentiated counterterrorism strategies. It is essential to recognize the diverse sociopolitical, economic, and psychological contexts in which individuals engage in terrorism. An integrated perspective, which considers the broad spectrum of factors that influence terrorism, allows for a more complete approach to combating this global threat, addressing both its immediate impacts and its root causes. Therefore, with this research, we intend to fill existing research gaps, synthesizing recent studies throughout these phases, and providing information on the continuum from recruitment to separation. The limited scope of studies examining these phases simultaneously emphasizes the need for more research into the dynamics of retention, focusing specifically on what drives sustained engagement and the factors that lead to attrition. This knowledge is vital for developing comprehensive counterterrorism strategies that address both entry and exit, ultimately strengthening the foundations for effective policies and interventions.

Studies indicate that the majority of individuals involved in terrorism are men (Younas and Sandler 2017). Therefore, a focused analysis of male participants allows for a more specific exploration of the factors influencing recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement. Gender dynamics within terrorism reveal unique motives, roles, and experiences for men and women (Duriesmith and Ismail 2022). For example, in certain communities, traditional gender roles and socioeconomic disparities—particularly prevalent in African contexts—can make men disproportionately vulnerable to recruitment (Nyamnjoh 2017). By examining male-specific sociocultural roles and economic pressures, this review provides a more targeted perspective on the pathways into and out of terrorist engagement, ultimately contributing to the development of gender-informed, context-sensitive counter-terrorism policies and interventions.

3. Methodology

The present systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. 2009). Only the studies that utilized empirical methodology and complied with the PICOS strategy (Participants, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design) were included in this systematic review. Thus, the studies that directly examined the process of recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement from terrorist groups in men were included.

The inclusion criteria were studies with (i) a focus on recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement from terrorist groups in men, (ii) studies with cross-sectional or longitudinal designs, (iii) qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies published in peer-reviewed journals, and (iv) studies written in English, Spanish or Portuguese.

3.1. Search Strategies

The search in the databases began in June and continued until November 2023. The studies with cross-sectional or longitudinal designs that explore the process of recruiting, remaining in, and quitting terrorism, and experimental and quantitative studies were eligible for inclusion. This systematic review also included studies based on hand-searching strategies that are considered important for this systematic review. The review protocol was registered with OSF (osf.io/np6f9).

Initially, different keywords and their combinations were defined, creating the following search equation: ((“terrorism” OR “insurgency” OR “extremism” OR “radicalism”) AND (“Terrorist” OR “extremist” OR “radicalise” OR “offender” OR “aggressor”) AND (“recruit*” OR “enlistment” OR “conscription” OR “grooming” OR “member*” OR “join*” OR “adhe*” OR “permanence” OR “affiliation” OR “involvement” OR “alienated” OR “disengagement” OR “desistance” OR “leave” OR “deradicalization” OR “withdrawal”)). This combination of keywords was used to run the search in several electronic databases: Academic Search Complet, SCOPUS, and Web of Science Collection. We limited our search to titles and abstracts, and English, Portuguese, and Spanish manuscripts.

3.2. Data Extraction

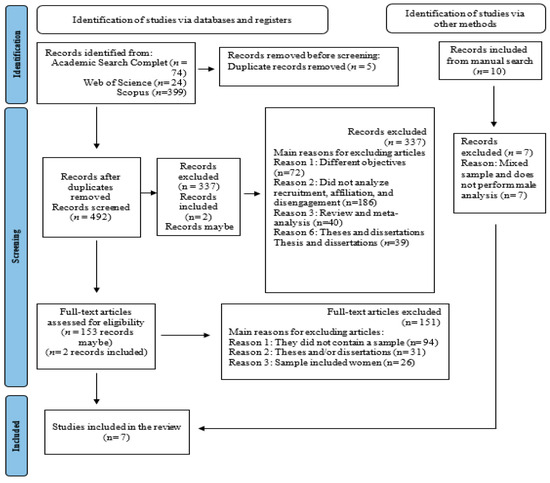

The citations extracted from the databases were imported into Rayyan, where duplicate articles were systematically removed. The titles and abstracts were carefully reviewed to assess whether the articles aligned with predetermined inclusion criteria. Those that met the criteria were read and examined in full to make a conclusive decision. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flowchart, detailing the number of studies incorporated in each stage of the selection process, along with the justification for inclusion/exclusion.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—flow diagram of the study selection process. Notes. Adapted from Moher et al. 2009.

3.3. Coding Procedures

A codebook was developed to extract data from all the included manuscripts on the following key characteristics: reference information (e.g., authors, year, country); type of study (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed); sample characteristics (e.g., size, group, ethnicity); topics under study (e.g., recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement); and main results. All the articles were coded independently by two researchers, with a third researcher to resolve possible differences between the evaluators. It should be noted that there were no conflicts in the researchers’ decisions.

3.4. Methodological Quality Analysis

In carrying out this study and to reduce threats to the validity of the included studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Horgan et al. 2017) was used to assess the methodological quality. The MMAT functions as a tool to simultaneously assess and/or articulate studies incorporated into systematic mixed studies reviews, encompassing original qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. This instrument has proven indispensable in mitigating bias in the synthesis of evidence. The MMAT started with two screening questions and then five evaluation criteria for the different types of study design. Each criterion was classified as “Yes”, “No” or “Can’t tell”, varying the quality score between 1 and 5. Two investigators independently assessed the methodological quality of the studies.

4. Results

The results are presented in two separate tables. Table 1 presents a description of the characteristics of the studies included in this review.

Table 1.

Study design and characteristics of the sample.

4.1. Included Studies

A total of 500 articles were found in the selected databases. Five articles were eliminated for being duplicates and the abstracts and titles of 492 articles were analyzed. Of these 492 articles, 337 articles were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria; for example, they (i) had different objectives (Borum 2014), (ii) did not analyze recruitment, affiliation, and dismissal (Piazza and Guler 2021), and (iii) were systematic reviews (Scarcella et al. 2016) (see Figure 1). After this procedure, 155 articles were read in full and the 151 articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion were (i) they did not present the sample under study (Papale 2021), (ii) they were systematic and literature reviews or gray literature, and (iii) they were samples of women (O’Rourke 2009).

A manual search was also carried out, yielding ten articles that explored the concepts under study; however, seven articles were excluded because they used unintentional samples and did not perform statistical analyses only for the male sample (Michelsen 2009). Thus, seven articles were included in the systematic review, of which three articles were added through manual searches and four through the PRISMA methodology protocoled for Systematic Reviews.

4.2. Quality Assessment

As shown in Table 1, four studies revealed good criteria (i.e., four of the five excellent criteria) (Altier et al. 2020; Karimi et al. 2022; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Kule and Gül 2015), one study presented three of the five criteria (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014), and two fulfilled only two of the quality criteria (Hwang 2015; Lakomy 2019).

4.3. Characteristics of Studies Included

Among the articles included (see Table 1), the following research designs were identified: qualitative studies (n = 5) (e.g., Hwang 2015; Karimi et al. 2022) and two mixed studies (qualitative and quantitative) (e.g., Altier et al. 2020; Lakomy 2019) (cf. Table 1). Most of the studies were carried out with a sample of individual terrorists (n = 6), one of which was based on content analysis (Lakomy 2019), which is a comparison between magazines serving the Islamic State.

All the other studies were conducted with male samples belonging to different radical groups: Al-Shaabab (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014), Indonesian jihadists, Jihadis dari JI and Mujahidin KOMPAK (Hwang 2015), the Salafist–Jihadist group in the Middle East (Karimi et al. 2022), Salafi–Jihadi world, al-Muhajiroun Jemaah Islamiyah Muslims (Kenney and Hwang 2020), Turkish, DHKPC, the PKK, and Hezbollah (Kule and Gül 2015), and the Islamic State (Lakomy 2019). These studies were conducted in different countries: Kenya and Somalia (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014), the USA (Altier et al. 2020), Indonesia (Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020) and Britain (Kenney and Hwang 2020), Iran (Karimi et al. 2022), Turkey (Kule and Gül 2015), and Poland (Lakomy 2019). Most of the groups included in this analysis use Jihad (Holy War against non-believers) as a central concept to legitimize their armed struggle. However, the PKK, which is also present in this sample, adopts a secular and nationalist approach, which does not fit into the jihadist paradigm.

Of the seven studies included in this systematic review, five were conducted in countries where Islam is the predominant religion (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Karimi et al. 2022; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Kule and Gül 2015), and two were carried out in countries where the predominant religion is Christianity (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014), particularly Protestantism (Horgan et al. 2017).

As illustrated in Table 2, four studies talk about the recruitment and engagement process (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Karimi et al. 2022; Kule and Gül 2015; Lakomy 2019), four studies about the permanence process (Altier et al. 2020; Hwang 2015; Karimi et al. 2022; Kenney and Hwang 2020), and three studies about disengagement (Altier et al. 2020; Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020).

Table 2.

Results for recruitment, permanence and disengagement.

The sample sizes varied, ranging from 2 participants (Lakomy 2019) to 200 participants (Kule and Gül 2015), and all the participants professed Islam.

4.4. Main Outcomes

The main results of the studies incorporated in this review are presented based on the results of recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement in a terrorist organization (see Table 2) and the main push factors and pull factors identified (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Push factors and pull factors influencing disengagement in terrorist organizations.

- Recruitment in Terrorist Organizations

Of the seven studies included in this systematic review, four address recruitment issues (see Table 2). The results show that recruitment factors influence each other in such complex ways that initial factors can change into ideological factors as recruits interact with influential members of the group (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014), with financial issues mainly responsible for explaining the appearance of supposed mercenaries or individuals who do not belong to any of the warring groups, with young people being the target audience most attracted by economic factors in the promise and expectation of financial benefits in joining terrorist groups (e.g., Al -Shabaab) (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014). Furthermore, regional factors and the desire to belong to a clan as well as the fight to protect the global Muslim community appear as factors associated with the recruitment process, with young people being easily recruited into these terrorist links, fueling the belief and conviction that they are at the mercy of a greater cause on a global scale (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014). These researchers highlight kidnapping as one of the most used strategies to recruit individuals into terrorist groups, forcing individuals to join against their will (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014).

Another form of recruitment evidenced in these studies is the publicity or propaganda carried out by these groups (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Lakomy 2019). For example, the Islamic State, in Daesh magazines, used “Hijrah” to carry out recruitment activities, representing a direct appeal to readers to go to places controlled or under the command of this terrorist group (Lakomy 2019). According to the results of this study, some of these magazines use subjective extracts from the Quran, citing purely religious narratives to justify violence against those considered infidels, inciting jihad, or leading readers to join the ranks of this terrorist organization, legitimizing an Islamic state and their violent conduct (Lakomy 2019). Thus, through information dissemination bodies they can spread a narrative around the formation of a caliphate and the call for Jihad, reaching all listeners, whether Muslim or not, as well as calling for violence against infidels and the planning of several terrorist attacks against unbelievers (Lakomy 2019). The strategy of utilizing the simplicity of Salafist discourse, which emphasizes religion and faith through the manipulation of extracts from the Al Quran, provides recruits with an apparent sense of security and firmness toward eternal happiness in paradise (Karimi et al. 2022).

However, studies have pointed to a paradigm shift in propaganda over time, inspiring “lone wolf” attacks; that is, individuals who identify with the ideology carry out their terrorist attacks in isolation and progressively respond to a call to carry out obligatory jihad wherever they are against the enemies of Allah (Lakomy 2019).

Regarding the strategies most used in the recruitment process, the results show that in a sample of 200 individuals belonging to different groups (G1: n = 60 Hezbollah, G2: n = 80 PKK; G3: n = 60 DHKP-C) who have already been involved in terrorist actions, 8.8% of the sample joined the group through family members, 9.8% through close relatives, 25.3% through other members of the organization, and the highest percentage of recruitment was carried out by partners at 46.9% (Kule and Gül 2015). According to the same authors, PKK recruits join at a lower average age than the other two organizations (Kule and Gül 2015). Although some of the recruitment strategies used are against the will of individuals, by using the recruitment strategies of the idealization, identification, and assimilation of group leadership to develop group bonds, identification is created in recruits with the figure of the leader associated with hypnotic suggestions of bravery and intelligence (Karimi et al. 2022).

- Affiliation in Terrorist Organization

Of the seven studies included in this systematic review, four pointed to some factors that influence affiliation within terrorist organizations (Altier et al. 2020; Hwang 2015; Karimi et al. 2022; Kenney and Hwang 2020) (see Table 2). Two of the studies pointed to loyalty and ideological issues as essential in the processes of staying in terrorist groups, showing that individuals remain in these organizations due to identification with the group’s ideology (Altier et al. 2020; Kenney and Hwang 2020). Thus, the process of affiliation seems to happen because these individuals have not yet felt disillusioned with the ideology, due to the scarcity of alternative social media and support networks external to these terrorist groups, given that the majority of their close family members are directly or indirectly linked to these organizations (Kenney and Hwang 2020), making the process of leaving these terrorist groups difficult.

Another factor for affiliation in this ideology of extreme violence is associated with the role that the individual plays in the group, with the results showing that individuals with positions of management and trust, leaders, or individuals in strategic positions are more likely to remain (Altier et al. 2020).

Furthermore, the results show that affiliation in these terrorist organizations is also achieved through indoctrination, leading to the gradual loss of the individual’s identity and the learning of a collective identity combined with the hypnotic suggestions of the group, literally exempting the individual from having any remorse for his terrorist actions given that it these actions are undertaken by the group with which he has strong bonds of commitment, thus promoting his permanence in the organization, and making it easy for him to get involved in violent acts against individuals outside the group (Karimi et al. 2022).

Another factor of permanence identified in these studies is associated with the migration of roles where the individual migrates from a more active role, usually combative, to a peaceful role, such as providing financial resources for the continuity of the group; in this role, the individual does not disengage and can remain indefinitely (Hwang 2015).

The results also show that the process of permanence of these roles played by individuals within the terrorist group is of much importance, making it easier for a simple combative member to leave their leader’s organization (Kenney and Hwang 2020).

- Disengagement in Terrorist Organization

Of the seven studies included in this systematic review, four pointed to some factors that influence quitting within terrorist organizations (Altier et al. 2020; Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020).

The results of the studies incorporated in this systematic review (see Table 2) show that disagreement with the actions carried out by the group, disillusionment with the tactics suggested by leadership, fundamentalist and inflexible ideology in relationships, divergences, dissatisfactions (Altier et al. 2020; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015), changing priorities, cost–benefit analyses, pressure from parents (Hwang 2015), new friendships, and relationships (Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020) are the main factors responsible for disengagement within terrorist organizations.

Furthermore, the results point to the social networks of individuals who committed terrorist acts as an essential factor in the disengagement process, providing them with opportunities and alternative lives outside of terrorist organizations (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015). The results point to government policies as attractive support for members who wish to leave and who perform violent operational roles in terrorist organizations (Altier et al. 2020).

In this disengagement process, the results point to the roles that individuals assume within terrorist organizations that are important in terms of the degree of ease or difficulty in the disengagement process (Altier et al. 2020; Hwang 2015), as well as the degree of burnout faced due to inflexible ideologies (Kenney and Hwang 2020), with some individuals leaving terrorist groups due to lack of action; that is, they become inactive, but continue to interact and have connections with the organization’s terrorists, due to the strengthening of ties and the belief in the ideology of an Islamic state (Hwang 2015). According to the results, in Somaliland, the resolution of disagreements and conflicts between clans and functional governance ensures an enlightened society free from the spread of a jihadist narrative, thus contributing to the disengagement of individuals linked in any way to Al-Shabaab (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014).

The studies included in this systematic review identify some push factors, which are cited for resistance within terrorist organizations and are seen as pull factors transversal to the different processes: disillusionment with leaders and members of the organization, disagreement about the strategies used (Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Lakomy 2019), unmet expectations (Altier et al. 2020) and disillusionment with the roles and contributions (Kenney and Hwang 2020), the loss of interest and faith in the group’s ideology (Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Lakomy 2019), a feeling that things have gone too far (Hwang 2015), the inability to deal with the physiological/psychological effects of violence (Lakomy 2019), feelings of emotional exhaustion/burnout (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Lakomy 2019; Hwang 2015), and difficulty in adapting to the clandestine lifestyle (Lakomy 2019), but also negative social sanctions from the families and the communities of the members (Hwang 2015).

As pull factors, studies highlight the possibility of positive interactions, opportunities and changing priorities (Hwang 2015), competing loyalties (Altier et al. 2020), finding a paid job and new educational opportunities, the possibility of building a family and getting married (Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Lakomy 2019), the opportunity to establish new friendships, relationships and support networks (Hwang 2015; Kenney and Hwang 2020). The changes in priorities arise from analyzing the costs and benefits of being in the organization, parental pressure (Hwang 2015), financial incentives or government amnesty initiatives (Lakomy 2019), social acceptance (Hwang 2015), and the desire for calm (Kenney and Hwang 2020), which are also considered pull factors.

Generally, both factors combined lead individuals to change their order of personal priorities, reducing their dedication to high-risk activities, but it is important to note that both push and pull factors combine in different ways for everyone (Kenney and Hwang 2020).

Some of the individuals in terrorist organizations, despite experiencing push and pull factors, remained steadfast in their ideology and activism because they do not change their priorities (Kenney and Hwang 2020). The results also show that individuals who have consumed the ideology of violent extremism are protected from possible factors, whether pull or push factors, that is, factors that could interfere to the point of changing their minds and thinking about a possible disengagement (Altier et al. 2020; Kenney and Hwang 2020).

The cost–benefit ratio in regard to disengagement is often brought to the fore by the push and pull factors within terrorist organizations, and the individuals who choose to remain, even in the face of these factors, mostly look for other grounds, such as ideological ones that counter the conflict initially established by the factors (Kenney and Hwang 2020).

5. Discussion

The main objective of this systematic review was to identify the factors associated with the recruitment, permanence and disengagement of individuals from terrorist groups, with special attention to the permanence process, as it is the process that ensures that individuals remain linked to terrorist groups. All the manuscripts included in this review followed a qualitative design, two of which used a mixed design, an essential methodology in better understanding this phenomenon given the multiple cultural and ideological aspects and discourses, and the fact that terrorism is an understudied phenomenon (Karimi et al. 2022). However, the literature has shown that studies on terrorism still lack the basis for a comprehensive primary investigation based on interviews and life stories of people involved in terrorist activities (Crenshaw 2011; Schuurman 2020), since most of the literature on terrorism was based on secondary sources and data (i.e., content analysis of newspapers or magazines) (Schuurman 2020). Although some efforts have been made to improve the methods used in this phenomenon, more recent investigations have shown that the use of a quantitative methodology remains underdeveloped (Schuurman 2020), and mixed designs can be fundamental in understanding terrorism, interconnecting trends statistics to narratives and individual experiences, which, combined, allow for a better and more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon (Tulga 2023).

Although terrorism is recognized as a global phenomenon that occurs in various contexts and regions, regardless of religious affiliation (Lutz 2019), most of the manuscripts included in this systematic review were carried out in a country where Islam is the predominant religion (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Hwang 2015; Karimi et al. 2022; Kenney and Hwang 2020; Kule and Gül 2015). This result corroborates the literature that indicates that many terrorist groups take advantage of mosques and madrassas to recruit and spread jihad (Kule and Gül 2015). However, these results may also be subject to a bias caused by the growing interest and investigation into groups related to Islam due to terrorist attacks and attacks carried out by Al-Qaeda and, more recently, by ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), attracting global attention and concern about the potential threat posed by these groups (Lutz 2019), causing an increase in research and interest in terrorism in regions where such groups have been active.

Regarding the process of recruiting individuals for these terrorist groups, the results of this systematic review suggest that young people represent the target audience most easily attracted. The results of this review present the promises of monetary benefits for adherence to terrorist ideology as a preponderant factor in the recruitment of younger individuals (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014), an indicator also supported by the literature that highlights that, given economic difficulties, limited educational and employment opportunities, and poverty, young people are more susceptible to recruitment (Brown 2020), and terrorist organizations exploit these economic challenges as recruitment tools, promising stability and financial purpose (“United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime” n.d.). This phenomenon of younger recruitment may also be associated with other multiple factors, highlighting the vulnerability of these young people, exploited by terrorist recruiters to mold them according to their ideological objectives, making them more susceptible to the influence of propaganda (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Lakomy 2019) and manipulation due to the continuous training of their own identity (Darden 2019; “United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime” n.d.). Moreover, the findings also indicate that a sense of belonging to a clan (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014) serves as a significant recruitment factor in younger individuals. This can be attributed to the appeal of group identity, perceptions of exclusion, grievances related to cultural threats, and personal connections, including family and friendship networks (Darden 2019). These aspects are leveraged by terrorist organizations that position themselves as cohesive entities.

The recruitment process for terrorist organizations often exploits the motivation to safeguard the global Muslim community, as revealed in the findings of this systematic review, by radicalizing younger individuals (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014). This motivation is commonly referred to as the defense of the Ummah, aiming to establish a so-called caliphate (al-Ahsan 1986; Mahood and Rane 2017). Young people are particularly drawn to the ideological narrative of defending the Ummah against perceived threats and injustices targeting Muslims globally, making the sense of defense a compelling motivator for young recruits (Mahood and Rane 2017). In the recruitment process, this study demonstrates that kidnapping is one of the strategies employed to recruit individuals for terrorist groups (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014). This strategy aims to instill fear and coercion, compelling individuals to join their ranks out of concern and fear (Akcinaroglu and Tokdemir 2018). It is crucial to note that while these coercive tactics are cost-effective, they necessitate close maintenance and monitoring, given that recruits do not join voluntarily; they are essentially uncommitted recruits. Therefore, a climate of fear must be sustained to prevent individuals from disengaging from the group, potentially leading to the alienation of a substantial number of people and mass defections among their primary supporters (Akcinaroglu and Tokdemir 2018). These organizations continue to be based on recruiting new elements, which is why they invest seriously in the process of recruiting new individuals (Kule and Gül 2015). According to the instructions of some studies in this systematic review, terrorist groups or organizations use propaganda or publicize their actions as one of the forms of recruitment (Amble and Meleagrou-Hitchens 2014; Lakomy 2019). This strategy has been suggested in the literature as a tool to attract individuals who identify with their causes and ideologies, building a sense of identity in potential recruits for the groups (Jenkins 2010).

The advent of online platforms and social networks has revolutionized the dissemination of propaganda. Terrorist organizations now can instantly reach a global audience. The results show that spaces serve as virtual recruitment sites where individuals, often called “lone wolves,” can be exposed to extremist ideologies and receive guidance on carrying out attacks (Lakomy 2019). These “lone wolves” are driven by ideological fundamentalism and, without showing themselves to belong to a specific group, are difficult to trace and detect due to the unpredictability of their actions (Leistedt 2016). In this propaganda and publicity strategy, as a way of recruiting new members for these terrorist organizations, the results of this study emphasized the simplicity of Salafist discourse (Karimi et al. 2022); due to the theological dimension of this movement, the direct interpretation of the verses of the Quran is carried out to the recruits, depicting a vision of the world that is apparently uncomplicated (“Salafi Interpretation of the Quran” n.d.). This speech is presented in a clear and direct way, and is easily disseminated and understood; that is, it becomes accessible to a diverse target audience (Østebø 2015).

The quantitative results obtained in this systematic review reveal that individuals are predominantly recruited by their partners (Kule and Gül 2015). Partnerships are typically built on trust and emotional connections; thus, when a partner is involved in a terrorist group and embraces radical ideology, they can easily influence or even coerce their partner through displays of dominance to join these groups (Card 2007; Horgan 2008). Additionally, studies indicate a noteworthy percentage of recruitment occurs through existing members of organizations (Kule and Gül 2015). These organizations, often operating as tightly knit networks with strong relationships, serve as recruiters and channels for new recruits (Zech and Gabbay 2016). They take advantage of shared ideologies to “convince” individuals to identify with the ideologies and discourse driven by ideological issues (Altier et al. 2020; Hwang 2015). The significance of identification with ideology emerges prominently in the findings of this systematic review as a crucial factor in the recruitment process (Karimi et al. 2022) and in the retention process within organizations (Altier et al. 2020; Kenney and Hwang 2020). These processes appear to be linked to the identification and veneration of leaders through hypnotic suggestions (Karimi et al. 2022), a central component in recruiting and retaining individuals within terrorist organizations. Aligning beliefs with the group’s ideological narrative provides a sense of purpose, belonging, and justification for actions developed within the groups (McCauley and Moskalenko 2008).

Certain extremist groups employ psychological manipulation techniques, including tactics comparable to hypnotic suggestions. This may involve the use of repetitive messages, indoctrination sessions, and methods aimed at breaking down critical thinking. In some cases, individuals may be more susceptible to suggestion due to a combination of psychological vulnerabilities and the influence of the group environment (Victoroff 2005).

In this context, the studies included in this systematic review underscore the crucial role that individuals play within a terrorist organization in the sustained affiliation to an extreme ideology of violence. Leaders or individuals occupying strategic positions demonstrate a higher likelihood of remaining committed (Altier et al. 2020; Hwang 2015). These leaders and strategically positioned individuals exert substantial influence on the dynamics of the terrorist group. Consequently, their actions, decisions, and communications can shape the direction of the organization. This influence is inevitable in reinforcing individuals’ commitment to the ideology, fostering a sense of responsibility for the group’s success (Hogg and Adelman 2013). In the process of remaining within these terrorist organizations, the results indicate a gradual loss of individual identity and the assimilation of a collective identity within the groups (Karimi et al. 2022). Identity transfer is a psychological mechanism that leads individuals to perceive their identity as deeply intertwined with the group’s identity, resulting in a blurred distinction between the “self” and the group. This phenomenon makes individuals more willing to sacrifice themselves for the collective cause (Swann et al. 2010). Additionally, we cannot disregard the indoctrination strategies employed within terrorist groups to integrate individuals into extremist ideologies. This involves a deliberate shaping of an individual’s beliefs and identity to align with the group’s ideology, constituting essential mechanisms of political radicalization (McCauley and Moskalenko 2008). It is crucial to emphasize in this discussion that disengagement pertains to a behavioral change, such as leaving a group or altering someone’s role within it. This change does not necessitate a shift in values or ideals but involves the abandonment of the objective of achieving change through violence. In contrast, deradicalization implies a cognitive change, indicating a fundamental shift in understanding (Bjorgo and Horgan 2008).

However, it appears that, up to this point, insufficient attention has been directed toward the other end of the spectrum, specifically the factors contributing to individual and collective disengagement from violence within extremist or radical groups (Bjorgo and Horgan 2008). Some of the results of this systematic review, in addition to the pull (alternative attractions) and push (dissatisfaction with group) factors, show the importance of government policies in supporting this process of disconnection from terrorist organizations (Altier et al. 2020). Individual predispositions play an important role in disengagement, but the creation and dissemination of good social integration policies at the government level about terrorist organizations can become a catalyst for this process of change (Altier et al. 2014).

This study also revealed some factors involved in the disconnection of individuals from terrorist groups, with some attraction factors that seem essential for individuals to reconsider their involvement in extremist activities and seek disconnection. Disillusionment (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015; Altier et al. 2020) proved to be a factor of push and pull in the process of leaving extremist groups, as did looking for attractive alternatives outside the group, such as returning to school, getting married or looking for a job (Barrelle 2015). Additionally, disagreement with group actions and ideology (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015; Altier et al. 2020), changing personal priorities, parental pressure (Hwang 2015), new friendships and relationships (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015), opportunities and alternative lives outside of terrorist organizations (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015), and becoming burned out (Kenney and Hwang 2020; Hwang 2015; Lakomy 2019) seem to be seeds of disappointment and disillusionment that can lead many individuals to leaving a group (Bjorgo and Horgan 2008). In this process of detachment from groups, the literature has shown the importance of parental support in the deradicalization of young extremists from the sphere of the influence of the terrorist organization with the support of programs designed by non-governmental organizations that mobilize parents (Kruglanski et al. 2014).

Pull and push factors underscore that individuals may disengage and, in their final moments, undergo deradicalization due to the less positive aspects of involvement in high-risk collective actions compared to the positive situations about alternatives (Mullins 2010). Nevertheless, the existing literature suggests that push factors have a more direct impact on decisions regarding disengagement (Bjorgo and Horgan 2008). Therefore, interventions should prioritize highlighting the negative aspects of organizational involvement before presenting appealing alternatives (Altier et al. 2020).

The disengagement process is thus a complex physical–emotional journey that varies from individual to individual, with factors interacting simultaneously in cycles of continuous reinforcement until the individual ultimately disengages (Hwang 2015). It is worth noting that push and pull factors combined can lead to disengagement, as certain factors may work for some individuals but not for others. Consequently, the issue of permanence remains an intriguing phenomenon for further study (Altier et al. 2020). While this systematic review consolidates key studies aiming to comprehend processes associated with terrorism, it reveals certain limitations (refer to Table 2). Primarily, a bias in the results is evident due to the predominant use of qualitative designs based on content analysis rather than direct discourse from individuals who experienced these processes firsthand. This may potentially constrain the depth of understanding regarding the phenomenon of terrorism.

Moreover, the studies included in this systematic review were predominantly conducted in countries where Islam is the predominant religion. This may introduce bias influenced by the heightened interest in investigations in regions associated with terrorist attacks perpetrated by groups such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS. The concentration of studies in specific regions could limit the generalizability of results to a broader global context, where terrorism manifests in diverse forms and motivations.

We recognise that the requirement to include the three phases of recruitment, affiliation and disengagement limited the sample of this study. For future reviews, we will consider relaxing the criteria to include studies centred on just one phase, which may increase methodological diversity and representativeness of the analysis. However, the limitation of the studies highlights a gap in the literature on the complete functioning of terrorist organisations. Our aim was to draw attention to this gap, emphasising the importance of the stay phase and encouraging future research into the complete cycle of recruitment, stay and disengagement.

The exclusion of studies in other languages also restricted our analysis. This methodological choice was due to limited linguistic resources, but for the sake of transparency we will discuss this restriction and recommend the inclusion of several languages in future research to enrich the analyses.

From the results of the studies reflected in this manuscript, although a multiplicity of factors related to recruitment, retention, and separation were put forward, they may not cover all the possible influences. Factors such as mental health, socioeconomic status, or political contexts could warrant further exploration.

6. Conclusions

The studies in this systematic review appear to focus on specific terrorist groups and their conclusions may not be universally applicable to all types of extremist organizations or ideologies (see Table 4). It should be noted that the fact that this research only involved men represents a limitation of the study, as we recognize the role that women play within terrorist organizations. Furthermore, the potential lack of recent and updated investigations in the literature may affect the relevance of the conclusions, given the dynamic nature of terrorism and the evolution of recruitment strategies. While this systematic review contributes to a deeper understanding of the recruitment, affiliation, and disengagement processes among men in terrorist organizations, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. Our study was confined to sources in three languages (English, Spanish, and Portuguese), a methodological choice that inevitably restricted access to valuable research published in other languages, such as German. This may have narrowed the scope of the findings. However, we believe our approach offers a clearer understanding of the transitions between these phases, which are crucial for determining whether individuals remain involved with a terrorist organization or disengage, as well as the roles they assume over time. Despite this comprehensive view, we recognize that future research could benefit from focusing on one specific phase—recruitment, affiliation, or disengagement—at a time. This could allow for greater methodological diversity and enrich the data available on these distinct but interrelated processes, ultimately relinquishing our understanding of how terrorist organizations function over time. It is essential to consider these limitations when interpreting the results of the systematic review and recognizing potential gaps in understanding the complex phenomenon of terrorism and individual involvement in extremist activities.

Table 4.

Key findings of the systematic review.

The findings of this study hold relevance for the formulation of guidelines (see Table 5) aimed at anti-terrorism interventions, subsequently reducing the risk of recruitment and recidivism within this population. A more accurate and precise understanding of the factors driving individuals to join terrorist organizations is essential to better address this issue. Only through this accurate identification can effective prevention and intervention policies be developed (Kule and Gül 2015). These policies should offer social and economic incentives, as well as provide alternative occupations, facilitating the reintegration of displaced individuals into non-militant social groups (Kruglanski et al. 2014).

Table 5.

Implications for research, practice, and policy.

Terrorism is a global challenge that transcends borders, making it imperative for the international community to collaborate in understanding and mitigating its underlying processes. By consolidating diverse studies from around the world, this systematic review seeks to offer a holistic perspective on the factors that shape the recruitment, involvement, and extinction of terrorist groups, thus contributing to a more coordinated and effective global response.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z.Z.; M.L.P. and S.C.; methodology, L.Z.Z. and M.L.P.; software, L.Z.Z. and M.L.P.; validation, R.A.G. and S.C.; formal analysis, L.Z.Z.; research, L.Z.Z.; resources, L.Z.Z.; data curation, L.Z.Z. and M.L.P.; writing—drafting the original project, L.Z.Z. and M.L.P.; writing—proofreading and editing, R.A.G. and S.C.; supervision, R.A.G. and S.C.; project administration, L.Z.Z.; acquisition of funding, R.A.G. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out at Psychology Research Center (CIPsi), Faculty of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; UID/01662/2020) through the State Budget.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data set presented in this article are not readily available because this project remains in progress, and data analysis is ongoing. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to id9674@alunos.uminho.pt.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agnew, Robert. 2010. A General Strain Theory of Terrorism. Theoretical Criminology 14: 131–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcinaroglu, Seden, and Efe Tokdemir. 2018. To Instill Fear or Love: Terrorist Groups and the Strategy of Building Reputation. Conflict Management and Peace Science 35: 355–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Ahsan, Abdullah. 1986. The Quranic Concept of Ummah. Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs. Journal 7: 606–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altier, Mary Beth, Christian N Thoroughgood, and John G Horgan. 2014. Turning Away from Terrorism: Lessons from Psychology, Sociology, and Criminology. Journal of Peace Research 51: 647–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altier, Mary Beth, Emma Leonard Boyle, Neil D. Shortland, and John G. Horgan. 2017. Why They Leave: An Analysis of Terrorist Disengagement Events from Eighty-Seven Autobiographical Accounts. Security Studies 26: 305–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altier, Mary Beth, Emma Leonard Boyle, and John G. Horgan. 2022. Terrorist Transformations: The Link between Terrorist Roles and Terrorist Disengagement. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 45: 753–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amble, John C., and Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens. 2014. Jihadist Radicalization in East Africa: Two Case Studies. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 37: 523–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, Omar. 2009. The De-Radicalization of Jihadists: Transforming Armed Islamist Movements. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrelle, Kate. 2015. Pro-Integration: Disengagement from and Life after Extremism. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 7: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorgo, Tore, and John G. Horgan, eds. 2008. Leaving Terrorism Behind: Individual and Collective Disengagement. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borum, Randy. 2011. Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories. Journal of Strategic Security 4: 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borum, Randy. 2014. Psychological Vulnerabilities and Propensities for Involvement in Violent Extremism. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 32: 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidlid, Torhild. 2021. Countering or Contributing to Radicalisation and Violent Extremism in Kenya? A Critical Case Study. Critical Studies on Terrorism 14: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Joseph M. 2020. Force of Words: The Role of Threats in Terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence 32: 1527–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, Claudia. 2007. Recognizing Terrorism. The Journal of Ethics 11: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Martha. 2011. Explaining Terrorism: Causes, Processes, and Consequences. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Darden, Jessica Trisko. 2019. Tackling Terrorists’ Exploitation of Youth. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Tackling-Terrorists%27-Exploitation-of-Youth-Darden/4be837e72a256cf9da0ce4b30f0026fbcb06360d (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Duriesmith, David, and Noor Huda Ismail. 2022. Masculinities and Disengagement from Jihadi Networks: The Case of Indonesian Militant Islamists. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 47: 1450–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, Peggy C., Stephen A. Cernkovich, and Jennifer L. Rudolph. 2002. Gender, Crime, and Desistance: Toward a Theory of Cognitive Transformation. American Journal of Sociology 107: 990–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Mohammed, and Creighton Mullins. 2015. The Radicalization Puzzle: A Theoretical Synthesis of Empirical Approaches to Homegrown Extremism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38: 958–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Bruce. 2006. Inside Terrorism. REV-Revised, 2. Columbia University Press. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/hoff12698 (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Hogg, Michael A., and Janice Adelman. 2013. Uncertainty–Identity Theory: Extreme Groups, Radical Behavior, and Authoritarian Leadership. Journal of Social Issues 69: 436–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, John. 2008. Deradicalization or Disengagement?: A Process in Need of Clarity and a Counterterrorism Initiative in Need of Evaluation. Perspectives on Terrorism 2: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, John, Mary Beth Altier, Neil Shortland, and Max Taylor. 2017. Walking Away: The Disengagement and de-Radicalization of a Violent Right-Wing Extremist. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 9: 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Julie Chernov. 2015. Why Terrorists Quit: The Disengagement of Indonesian Jihadists. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Brian Michael. 2010. Would-Be Warriors: Incidents of Jihadist Terrorist Radicalization in the United States Since 11 September 2001. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Edgar. 2017. The Reception of Broadcast Terrorism: Recruitment and Radicalisation. International Review of Psychiatry 29: 320–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Yusef, David Nussbaum, and Razgar Mohammadi. 2022. Recruitment Process in Salafi-Jihadist Groups in the Middle East (A Qualitative Study). Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP12745–NP12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, Michael, and Julie Chernov Hwang. 2020. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Understanding How British and Indonesian Extremists Disengage and Why They Don’t. Political Psychology 42: 537–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., Michele J. Gelfand, Jocelyn J. Bélanger, Anna Sheveland, Malkanthi Hetiarachchi, and Rohan Gunaratna. 2014. The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism. Political Psychology 35 Suppl. 1: 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kule, Ahmet, and Zakir Gül. 2015. How Individuals Join Terrorist Organizations in Turkey: An Empirical Study on DHKP-C, PKK and Turkish Hezbollah. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/How-Individuals-Join-Terrorist-Organizations-in-An-Kule-G%C3%BCl/9a097253fbc867617663ad5e4f892fbed83291ef (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Lachman, Pamela, Caterina G. Roman, and Meagan Cahill. 2013. Assessing Youth Motivations for Joining a Peer Group as Risk Factors for Delinquent and Gang Behavior. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 11: 212–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakomy, Miron. 2019. Recruitment and Incitement to Violence in the Islamic State’s Online Propaganda: Comparative Analysis of Dabiq and Rumiyah. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 44: 565–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistedt, Samuel J. 2016. On the Radicalization Process. Journal of Forensic Sciences 61: 1588–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lia, Brynjar. 2004. Causes of Terrorism: An Expanded and Updated Review of Literature. Kjeller: Forsvarets Forskningsinstitutt. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, Brenda. 2019. Global Terrorism, 4th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahood, Samantha, and Halim Rane. 2017. Islamist Narratives in ISIS Recruitment Propaganda. The Journal of International Communication 23: 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, Clark, and Sophia Moskalenko. 2008. Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways Toward Terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence 20: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, Nicholas. 2009. Addressing the Schizophrenia of Global Jihad. Critical Studies on Terrorism 2: 453–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, Sam. 2010. Rehabilitation of Islamist Terrorists: Lessons from Criminology. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 3: 162–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Peter R. 2013. The Trouble with Radicalization. International Affairs 89: 873–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamnjoh, Francis B. 2017. Incompleteness: Frontier Africa and the Currency of Conviviality. Journal of Asian and African Studies 52: 253–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, Lindsey A. 2009. What’s Special about Female Suicide Terrorism? Security Studies 18: 681–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østebø, Terje. 2015. African Salafism: Religious Purity and the Politicization of Purity. Islamic Africa 6: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeren, Suleyman, Hakan Hekim, M. Salih Elmas, and Halil Ibrahim Canbegi. 2018. An Analysis of ISIS Propaganda and Recruitment Activities Targeting the Turkish-Speaking Population. International Annals of Criminology 56: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papale, Simone. 2021. Framing Frictions: Frame Analysis and Al-Shabaab’s Mobilisation Strategies in Kenya. Critical Studies on Terrorism 14: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, James A., and Ahmet Guler. 2021. The Online Caliphate: Internet Usage and ISIS Support in the Arab World. Terrorism and Political Violence 33: 1256–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sageman, Marc. 2004. Understanding Terror Networks. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, Jaspal Kaur, and Divya Bansal. 2021. Detecting Online Recruitment of Terrorists: Towards Smarter Solutions to Counter Terrorism. International Journal of Information Technology 13: 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Salafi Interpretation of the Quran”. n.d. Sahih Iman. Available online: https://sahihiman.com/books/salafi-interpretation-of-quran (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Scarcella, Akimi, Ruairi Page, and Vivek Furtado. 2016. Terrorism, Radicalisation, Extremism, Authoritarianism and Fundamentalism: A Systematic Review of the Quality and Psychometric Properties of Assessments. PLoS ONE 11: e0166947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Alex. 2013. Radicalisation, De-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review. Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism Studies 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, Bart. 2020. Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship. Terrorism and Political Violence 32: 1011–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Jessica, and John Michael Berger. 2015. ISIS: The State of Terror. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, William B., Ángel Gómez, John F. Dovidio, Sonia Hart, and Jolanda Jetten. 2010. Dying and Killing for One’s Group: Identity Fusion Moderates Responses to Intergroup Versions of the Trolley Problem. Psychological Science 21: 1176–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulga, Ahmet. 2023. The Importance of Mixed Method in Terrorism Study. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 7: 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- “United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime”. n.d. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/?lf_id= (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Victoroff, Jeff. 2005. The Mind of the Terrorist: A Review and Critique of Psychological Approaches. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 49: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, David, Michael Wolfowicz, Badi Hasisi, Mario Paolucci, and Giulia Andrighetto. 2022. What is the best approach for preventing recruitment to terrorism? Findings from ABM experiments in social and situational prevention. Criminology and Public Policy 21: 461–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, Ahmet. 2007. A Case Study on the Recruitment Process of Terrorist Organizations. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 161–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yayla, Ahmet. 2021. Prevention of Recruitment to Terrorism. The Hague: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, Javed, and Todd Sandler. 2017. Gender Imbalance and Terrorism in Developing Countries. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 61: 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, Steven T., and Michael Gabbay. 2016. Social Network Analysis in the Study of Terrorism and Insurgency: From Organization to Politics. International Studies Review 18: 214–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).