Abstract

In the scenario of fighting bacterial resistance to antibiotics, natural products have been extensively investigated for their potential antibacterial activities. Among these, cannabinoids—bioactive compounds derived from cannabis—have garnered attention for their diverse biological activities, including anxiolytic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties. Emerging evidence suggests that cannabinoids may also possess significant antimicrobial properties, with potential applications in enhancing the efficacy of conventional antimicrobial agents. Therefore, this review examines evidence from the past five years on the antimicrobial properties of cannabinoids, focusing on underlying mechanisms such as microbial membrane disruption, immune response modulation, and interference with microbial virulence factors. In addition, their synergistic potential, when used alongside standard therapies, underscores their promise as a novel strategy to address drug resistance, although further research and clinical trials are needed to validate their therapeutic use. Overall, cannabinoids offer a promising avenue for the development of innovative treatments to combat drug-resistant infections and reduce the reliance on traditional antimicrobial agents.

1. Introduction

Antibiotics have long been the treatment strategy for microbial infections. However, the uncontrolled and excessive use of these compounds has led to the development of microorganisms that are resistant to the action of antimicrobial agents, and this has become a problem and a worrying challenge on a global scale. Therefore, one of the priorities of the scientific community has been the search for innovative treatments with novel agents and the exploration of alternative strategies capable of controlling and eradicating these microorganisms and preventing disease, thus promoting global health [1].

These new strategies include the investigation of new drug delivery systems and alternative biomolecules with potential antimicrobial activity.

Regarding new drug delivery systems, several studies have reported the use of a variety of nanomaterials, such as copper, silver, gold, titanium, zinc, and others, in the management of infections. Metallic nanostructures, particularly gold and silver nanoparticles, are widely used in the design of targeted drug delivery systems due to their unique properties, such as stability against corrosion and oxidation, sizes ranging from 1 to 100 nm, good biocompatibility, versatility in surface functionalization, the ability to conjugate drugs through ionic, covalent or physical interactions, and shape-controlled synthesis [2]. These systems enhance the stability, absorption, and circulation of phytocompounds, protecting them from early metabolism and adverse effects. Modified nanocarriers improve the solubility, permeability, and sustained delivery of compounds to targeted diseased sites, thereby improving bioavailability [3]. The work of Alhadrami et al. [4] tested flavonoid-coated gold nanoparticles against Gram-negative bacteria. Also promising are silver nanoparticles, which have shown great potential as nano-fungicides [5], nano-viricides [6], and nano-bactericides [7]. Greatti et al. [8] were successful in using poly-ε-caprolactone nanoparticles with 4-nerolidylcatechol to control the growth of Microsporum canis. Preethi and Bellare [9] used another bioflavonoid (quercetin) complexed in magnesium-doped calcium silicates to control Gram-negative bacterial bone infections. These researchers observed a marked reduction in bacterial adhesion and proliferation. Another new vehicle for conventional antibiotic delivery was presented by Lin et al. [10]. In this work, aerosolized hypertonic saline was used to enhance the antibiotic susceptibility of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

In addition to the search and development of new drug delivery systems, the scientific community has also focused on the study of new biomolecules for the treatment of infections and the development of eco-friendly approaches, such as the use of biological extracts and biomolecules to produce antimicrobial agents. These strategies focus on targeting pathogens while reducing the impact on non-target organisms [11]. For example, Han et al. [12] demonstrated the efficacy of grapefruit seed extracts as an antibacterial agent.

Several studies have also highlighted the importance of sustainable strategies in the synthesis of nanoparticles. As an example, Lakkim et al. [13] developed a new green method for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles and observed an improvement in the performance against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. These new approaches have been combined with the use of Cannabis sativa [14]. Singh et al. [15] reported the use of Cannabis sativa for the green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles and demonstrated their activity in biofilm inhibition, while Chouhan & Guleria [16] characterized the antibacterial and anti-yeast activities of silver nanoparticles prepared with Cannabis sativa leaf extracts.

Another recent approach is the use of molecules targeting DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV to control microbial infections. This was the case of Saleh et al. [17], who tested the efficacy of DNA gyrase inhibitors, diphenylphosphonates, against fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens. Moreover, monoclonal antibody-based treatments are being investigated for cases of severe sepsis. The advantage of this approach is the specificity of the method since these antibodies target the microorganism or its components and can directly suppress the synthesis of inflammatory agents [18,19,20].

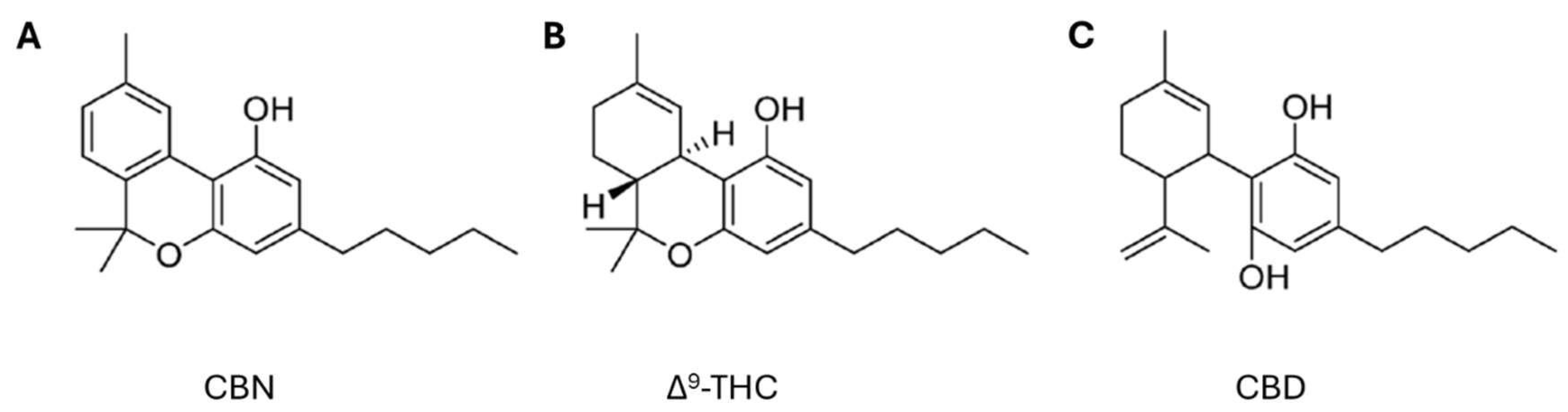

Among these novel strategies, Cannabis sp. has received significant attention from the scientific community for its potential applications across diverse therapeutic areas, including the treatment of inflammation, pain management, cancer therapy, neuroprotection, and others [21,22,23]. Cannabis is a herbaceous plant belonging to the Cannabinaceae family that has been used for centuries for textile, food, medicinal, and recreational purposes [24]. This plant contains several chemically active compounds, such as cannabinoids, terpenes, alkaloids, and flavonoids. Cannabinoids can be classified into three types: endogenous, known as endocannabinoids, which occur naturally in mammals, the best known being anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG); phytocannabinoids (Figure 1), which are naturally found in the cannabis plant, including cannabidiol (CBD), delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and cannabichromene (CBC); and synthetic cannabinoids, produced in the laboratory. All these cannabinoids can bind to cannabinoid receptors type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2), which are located in the plasma membranes of nerve cells and the immune system, respectively [25].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of phytocannabinoids (A) cannabinol (CBN), (B) delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), and (C) cannabidiol (CBD) (adapted from Bow and Rimoldi [26]).

Over time, phytocannabinoids have proven their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity and have potential use in these new therapies [27]. In some cases, researchers have also evaluated the synergistic effect that might exist between cannabinoids and conventional antibiotics, with the aim of antagonizing bacterial resistance mechanisms [24].

This scoping review aims to provide a concise overview of the evidence from the last 5 years (2020–2024) on the therapeutic potential of cannabinoids against different classes of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi), which may pave the way for the development of novel therapies.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28]. The literature search was conducted on 13 November 2024, using PubMed, Scopus, and ScienceDirect databases, and supplemented by manually searching the reference lists of included studies. The search included all original research papers published from 1 January 2020, to 31 October 2024. PubMed was searched using the following search strategy: (“cannab*” AND (“antimicrobial*” OR “antibacterial*” OR “antiviral*” OR “antifungal*” OR “Antibiofilm”)) NOT “review” [Publication Type]) in the title or abstract. This strategy was then adapted to the syntax and subject headings of the other databases. The detailed search strategy for each database, designed to maximize the retrieval of relevant articles, is presented in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material section.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included according to the following criteria: (1) studies written in English; (2) studies evaluating the antimicrobial activities of cannabinoid compounds; (3) studies performed in vitro and/or in vivo.

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria: (1) review articles or conference abstracts; (2) studies not relevant to the review topic; (3) studies evaluating the antimicrobial effects of cannabis extracts, oils, flowers, or pollen; (4) studies not related to human infections; and (5) studies using models other than in vivo and in vitro models.

2.3. Overview of Included Studies

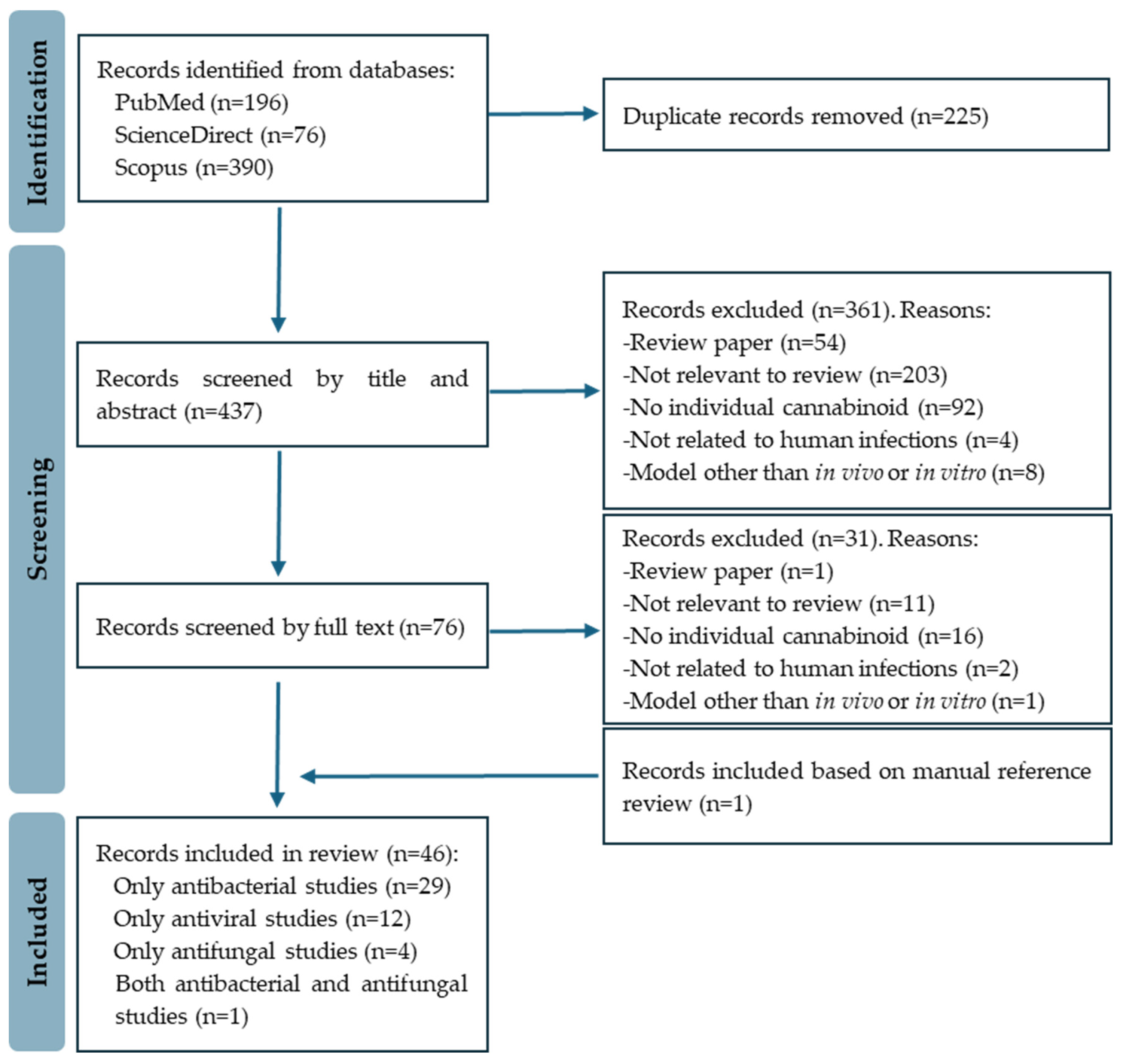

The initial search yielded a substantial pool of 662 records. The EndNote 20 software was employed to eliminate duplicates, resulting in a refined set of 437 research articles for further review. An initial meticulous screening based on titles and abstracts resulted in the exclusion of 361 records. The full text of the remaining 76 papers was then reviewed, with 46 studies ultimately meeting the eligibility criteria considered for this review. The included studies covered antibacterial (30 papers), antiviral (12 papers), and antifungal (5 papers) activities. Figure 2 depicts the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

2.4. Data Extraction

The following information was extracted from the selected articles: publication details (first author’s last name and publication year), study type, objectives, and key findings. The information is summarized in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3.

A scoping review provides an overview of the existing evidence, regardless of its quality. Therefore, critical appraisal, also referred to as the assessment of risk of bias or methodological quality assessment, was not conducted for the studies included in this review [29].

3. Results

3.1. Antibacterial Activity of Cannabinoids

The search strategy of this scoping review led to the selection of 30 publications that studied the antibacterial activity of cannabinoids. Moreover, some studies also discussed the possible mechanisms involved in this activity against bacteria. Table 1 shows the list of the selected papers together with the classification of the type of study, main goals, and results.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies and the main results of the antibacterial activity of cannabinoids. (Abbreviations: CBD: cannabidiol, CBC: cannabichromene, CBG: cannabigerol, CBN: cannabinol, CBCA: cannabichromenic acid, CBDA: cannabidiolic acid, CBDV: cannabidivarin, CBGA: cannabigerolic acid, EPS: extracellular polysaccharide, H2CBD: dihydrocannabidiol, LPS: lipopolysaccharide, MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration, THCBD: tetrahydrocannabidiol, VRE: vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MSSA: methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, VISA: vancomycin-intermediate resistant S. aureus).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies and the main results of the antibacterial activity of cannabinoids. (Abbreviations: CBD: cannabidiol, CBC: cannabichromene, CBG: cannabigerol, CBN: cannabinol, CBCA: cannabichromenic acid, CBDA: cannabidiolic acid, CBDV: cannabidivarin, CBGA: cannabigerolic acid, EPS: extracellular polysaccharide, H2CBD: dihydrocannabidiol, LPS: lipopolysaccharide, MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration, THCBD: tetrahydrocannabidiol, VRE: vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MSSA: methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, VISA: vancomycin-intermediate resistant S. aureus).

| Author (Year) | Type of Study | Aims | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abichabki et al. [30] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antibacterial activity of CBD against a wide diversity of bacteria and of the combination CBD + polymyxin B (PB) against Gram-negative bacteria, including PB-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. |

|

| Aqawi et al. [31] | In vitro study | To evaluate the anti-quorum sensing (anti-QS) and anti-biofilm formation potential of CBG on Gram-negative Vibrio harveyi. |

|

| Aqawi et al. [32] | In vitro study | To study the antibacterial activity of CBG against Streptococcus mutans. |

|

| Aqawi et al. [33] | In vitro study | To evaluate the potential use of CBG against S. mutans biofilms as a means to combat dental plaque. |

|

| Avraham et al. [34] | In vitro study | To study the anti-biofilm activity of CBD combined with triclosan against Streptococcus mutans. |

|

| Barak et al. [35] | In vitro study | To study the antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of CBD against Streptococcus mutans. |

|

| Blaskovich et al. [36] | In vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo studies | To evaluate the antibacterial activity of CBD against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. |

|

| Cham et al. [37] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antibacterial potential of a semisynthetic phytocannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabidiol (THCBD, 4) against sensitive and resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. |

|

| Cohen et al. [38] | In vitro, ex vivo, and clinical studies | To evaluate the efficacy of a newly developed natural topical formulation based on CBD for the treatment of acne. |

|

| Farha et al. [39] | In vitro and in vivo studies | To study the antibacterial activity of cannabinoids against MRSA. |

|

| Galletta et al. [40] | In vitro study | To study the ability of the phytocannabinoid CBCA and its related synthetic analogs to successfully inhibit the growth of MRSA and other clinically relevant pathogenic bacteria. |

|

| Garzón et al. [41] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties and the immune modulatory activities of CBD and CBG on oral bacteria and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. |

|

| Gildea et al. [42] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antibacterial potential of CBD against Salmonella newington and Salmonella typhimurium. |

|

| Gildea et al. [43] | In vitro study | To evaluate the potential synergy between CBD and three broad-spectrum antibiotics (ampicillin, kanamycin, and polymyxin B) for potential CBD-antibiotic co-therapy. |

|

| Hongsing et al. [44] | In vitro and in vivo studies | To evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of CBD against clinical isolates of multi-drug resistant Enterococcus faecalis bacterial infections in vitro and in vivo. |

|

| Hussein et al. [45] | In vitro study | To study the mechanisms of the antibacterial killing synergy of the combination of polymyxin B with CBD against A. baumannii ATCC 19606. The antibacterial synergy of the combination against a panel of Gram-negative pathogens (Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) was also explored using checkerboard and static time–kill assays. |

|

| Jackson et al. [46] | In vitro study | To test the antibiotic potential of CBD, CBC, CBG, and their acidic counterparts (CBDA, CBGA, and CBCA) against Gram-positive bacteria and explore the additive or synergistic effects with silver nitrate or silver nanoparticles. |

|

| Kesavan Pillai et al. [47] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antimicrobial activity of solubilized CBD against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial strains. |

|

| Luz-Veiga et al. [48] | In vitro study | To study CBD and CBG interaction and their potential antimicrobial activity against selected microorganisms (human-skin-specific microorganisms commonly associated with inflammatory skin conditions). |

|

| Martinena et al. [49] | In vitro study | To investigate the antimicrobial effect of CBD on Mycobacterium tuberculosis intracellular infection. |

|

| Martinenghi et al. [50] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antimicrobial effect of CBDA and CBD. |

|

| Poulsen et al. [51] | In vitro study | To investigate the antibacterial activities of CBD, CBN, and THC against MRSA strains. |

|

| Russo et al. [52] | In vitro study | To compare the antibacterial activities of CBD and CBDV against E. coli and S. aureus. |

|

| Shi et al. [53] | In vitro study | To determine the anti-inflammatory activity of dihydrocannabidiol, (H2CBD) and its antibacterial properties against E. faecalis and B. cereus. |

|

| Stahl & Vasudevan [54] | In vitro study | To compare the efficacy of oral care products and cannabinoids (CBD, CBC, CBN, CBG, and CBGA) in reducing the bacterial content of dental plaques. |

|

| Valh et al. [55] | In vitro study | To determine the antioxidant and antibacterial activities of microencapsulated CBD against E. coli and S. aureus. |

|

| Vasudevan & Stahl [56] | In vitro study | To evaluate CBD and CBG-infused mouthwash products against aerobic bacterial content from dental plaque samples. |

|

| Wassmann et al. [57] | In vitro study | To characterize CBD as a helper compound against resistant bacteria. |

|

| Wu et al. [58] | In vitro study | To determine the antibacterial, bactericidal, and antioxidant activities of 8,9-dihydrocannabidiol against S. aureus and E. coli. |

|

| Zhang et al. [59] | In vitro study | To study the antibacterial activities of a series of novel CBD derivatives against MRSA. |

|

3.2. Antiviral Activity of Cannabinoids

The search strategy of this scoping review led to the selection of 12 publications that investigated the antiviral activity of cannabinoids. In addition, some studies also discussed the possible mechanisms involved in this activity against viruses. Table 2 shows the list of the selected papers together with the classification of the type of study, main goals, and results.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies and the main results of the antiviral activity of cannabinoids. (Abbreviations: CBG: cannabigerol, CBL: cannabicyclol, CBN: cannabinol, CBD: cannabidiol, CBDA: cannabidiolic acid, CBGA: cannabigerolic acid, NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, THC: tetrahydrocannabinol).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies and the main results of the antiviral activity of cannabinoids. (Abbreviations: CBG: cannabigerol, CBL: cannabicyclol, CBN: cannabinol, CBD: cannabidiol, CBDA: cannabidiolic acid, CBGA: cannabigerolic acid, NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, THC: tetrahydrocannabinol).

| Author (Year) | Type of Study | Aims | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classen et al. [60] | In vitro study | To test synthetic CBG and CBL for potential antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

| Marques et al. [61] | In vitro study | To evaluate the effect of three derivatives and an analog of CBD on non-infected VERO cell viability and antiviral activities against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

| Marquez et al. [62] | In vitro study | To explore the in vitro antiviral activity of CBD against ZIKV, as well as expanding to other dissimilar viruses. |

|

| Nguyen et al. [63] | In vitro study | To determine CBD’s potential to inhibit infection of cells by SARS-CoV-2 |

|

| Pawełczyk et al. [64] | In vitro study | To explore the potential of the molecular consortia of CBD and NSAIDs (ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and naproxen) as novel antiviral dual-target agents against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

| Pitakbut et al. [65] | In vitro study | To determine the mechanism of action of THC, CBD, and CBN against SARS-CoV2 infection. |

|

| Polat et al. [66] | In vivo study | To determine the antiviral activity of CBD against SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18-hACE2 transgenic mice. |

|

| Raj et al. [67] | In vitro study | To estimate the antiviral activity of cannabinoids (CBD, CBN, CBDA, Δ9-THC, Δ9-THCA) against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

| Santos et al. [68] | In vitro study | To evaluate the combination of CBD and terpenes in reducing SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. |

|

| Tamburello et al. [69] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antiviral activity of CBDA against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

| Van Breemen et al. [70] | In vitro study | To determine the antibacterial activities of cannabinoid acids against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

| Zargari et al. [71] | In vitro study | To test the antiviral activity of 7α-acetoxyroyleanone, curzerene, incensole, harmaline, and CBD against SARS-CoV-2. |

|

3.3. Antifungal Activity of Cannabinoids

The search strategy of this scoping review led to the selection of 5 publications that evaluated the antifungal activity of cannabinoids. Moreover, some studies also discussed the possible mechanisms involved in this activity against fungi. Table 3 shows the list of the selected papers together with the classification of the type of study, the main objectives, and the results.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies and the main results of the antifungal activity of cannabinoids. (Abbreviations: ADH5: alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (class III), CBD: cannabidiol, EPS: extracellular polysaccharide, DPP3: dipeptidyl peptidase 3, ROS: reactive oxygen species, SOD: superoxide dismutase).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies and the main results of the antifungal activity of cannabinoids. (Abbreviations: ADH5: alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (class III), CBD: cannabidiol, EPS: extracellular polysaccharide, DPP3: dipeptidyl peptidase 3, ROS: reactive oxygen species, SOD: superoxide dismutase).

| Author (Year) | Type of Study | Aims | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahraminia et al. [72] | In vitro study | To determine the antifungal activity of CBD against Candida albicans. |

|

| Feldman et al. [73] | In vitro study | To determine the potential anti-biofilm activity of CBD and to investigate its mode of action against C. albicans. |

|

| Feldman et al. [74] | Ex vivo and in vivo studies | To investigate the possibility of incorporating CBD, triclosan, and CBD/triclosan into a sustained-release varnish SRV (SRV-CBD, SRV-triclosan) to increase the pharmaceutical potential against C. albicans biofilm. |

|

| Kesavan Pillai et al. [47] | In vitro study | To evaluate the antimicrobial activity of solubilized CBD against fungal strains (C. albicans, M. furfur). |

|

| Ofori et al. [75] | In vitro study | To assess the anti-Candida properties of newly synthesized abnormal CBD derivatives (AbnCBD) |

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Antibacterial Activity of Cannabinoids—Recent Findings and Interpretation

The growing resistance of bacteria to antibiotics is one of the greatest challenges facing global public health, making the discovery of new therapies an urgent priority. This need is even more pressing and challenging in the case of Gram-negative bacteria, whose cell wall creates a more efficient permeability barrier to external agents. Antimicrobial resistance is also on the rise among Gram-positive bacteria. Among these, Staphylococcus aureus and its most resistant form, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), stand out as the cause of hospital- and community-associated infections worldwide and are also an important factor in morbidity and mortality [76]. In this context, the antibacterial properties of cannabinoids have attracted considerable attention.

Several studies have demonstrated the significant antibacterial activity of cannabinoids (Δ9-THC, CBD, CBC, and CBG, and their acid forms CBDA, CBCA, and CBGA), especially against Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus [52,55,58,59], vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE), MRSA, and vancomycin-intermediate resistant (VISA) S. aureus [30,36,39,40,46,50,51], as well as the oral cariogenic Streptococcus mutans [32,35,41]. CBD and CBG showed a range of MIC values between 2 and 5 µg/mL against several Gram-positive bacteria [30,35,36,37,39,44,50], and neither of them demonstrated resistance after repeated exposure [36,39]. Against S. mutans, CBG demonstrated a bacteriostatic effect at 2.5 µg/mL, which was influenced by the initial bacterial cell density, and a bactericidal effect at higher concentrations of 5–10 µg/mL [32]. Concentrations of 5 and 10 μg/mL of CBD reduced the growth of Cutibacterium acnes [38]. Galletta et al. [40] reported that CBCA was especially potent against MRSA, exhibiting faster and more effective bactericidal activity compared to vancomycin, particularly against exponential- and stationary-phase bacteria. The authors also demonstrated that this cannabinoid induced rapid Bacillus subtilis cell lysis, allowing for a shorter treatment duration, which helps to minimize the risk of antimicrobial resistance developing against this compound [40].

Although cannabinoids have been shown to inhibit the growth of a variety of Gram-positive bacteria, their antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative bacteria is limited, possibly due to the presence of the outer membrane, lipopolysaccharides, and porins, which are critical factors in bacterial resistance to external agents. These bacteria are thus impermeable to macromolecules and allow only limited diffusion of hydrophobic molecules [27,30,47,50].

Nevertheless, Gildea et al. [42] observed that CBD exhibited an antibacterial effect against two strains of Gram-negative bacteria, Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella Newington, through the disruption of cell membrane integrity. In addition, CBD was found to have antibacterial activity similar to that of ampicillin, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) approximately one-fifth that of ampicillin. However, the two strains also developed resistance to CBD after 48 hours, suggesting that the mechanism of resistance of the strains to CBD may be different from the mechanism of resistance to antibiotics. Finally, the authors found that CBD, in combination with ampicillin, was effective against biofilms of S. typhimurium [42].

Additionally, other studies have demonstrated the antibacterial efficacy of CBD against Gram-negative bacteria, including E. coli ATCC-25922 (with a MIC of 4 μg/mL [37]), Neisseria gonorrhoeae [36], E. coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [48].

Studies by Martinena et al. [49] concluded that CBD has a moderate but selective effect on inhibiting the growth of Mycobacterium smegmatis (MIC = 100 μM) and Mycobacterium. tuberculosis H37Rv (MIC = 25 μM) [49].

Antimicrobial resistance is a major concern in infectious diseases and is closely related to the formation of bacterial biofilms. A biofilm is a structured community of microorganisms embedded in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) attached to a surface. The biofilm formation process is complex and involves the clustering of microbial cells within an EPS matrix composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which together create a three-dimensional structure. Biofilms contain multiple microbial species that work synergistically within this matrix, protecting microorganisms from antimicrobial agents and the immune system. Biofilms also harbor antibiotic-resistant and persister cells that can survive and regrow after antibiotic treatment [77]. As these biofilm communities contribute to the virulence of infections and play a key role in bacterial relapses and chronic infections, it is essential to evaluate the ability of cannabinoids to eliminate them.

In the study of Fahra et al. [39], CBG, CBD, CBN, CBCA, and Δ9-THC demonstrated an ability to inhibit biofilm formation by MRSA, with CBG being the most potent. In the same study, CBG eliminated preformed MRSA biofilms at 4 μg/mL and was effective against stationary-phase cells that were resistant to conventional antibiotics such as gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin [39]. Aqawi et al. [31] reported the anti-biofilm potential of CBG against Vibrio harveyi that exhibited strong anti-quorum sensing activity by disrupting the transmission of autoinducer signals, thereby interfering with bacterial communication without affecting the bacteria’s growth. CBG also reduced bacterial motility (a key factor in biofilm formation), disrupted biofilm structure at sub-MIC concentrations, and reduced the expression of biofilm-regulating genes [31,32]. In recent studies, CBD reduced the viability of S. mutans biofilms at 7.5 μg/mL and decreased the metabolic activity of multispecies biofilms [35,41]. It also influenced mature biofilms and was effective against Salmonella typhimurium biofilms at 0.125 μg/mL and Enterococcus faecalis biofilms at low concentrations (2 μg/mL), with its activity sometimes surpassing those of conventional antibiotics (vancomycin, levofloxacin, and daptomycin) [42,44]. Biofilms exhibit increased resistance to antibacterial treatments due to their structural complexity, which impedes drug penetration, and the low metabolic activity of the sessile bacteria within them. Consequently, eradicating bacteria in biofilms poses a greater challenge compared to targeting planktonic bacteria. Despite these challenges, Barak et al. [35] demonstrated that CBD effectively inhibited both planktonic growth and biofilm formation of S. mutans, with the MIC and minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration both being 5 µg/mL. In another study, Aqawi et al. [33] showed that CBG also exhibits this dual antibacterial/ antibiofilm activity against S. mutans at concentrations as low as 2.5 µg/mL. CBG, similar to CBD, disrupts biofilm formation both indirectly through its antibacterial properties and directly by targeting metabolic pathways essential for biofilm regulation. Specifically, CBG reduces the expression of key biofilm-regulating genes, inhibits EPS production, disrupts quorum sensing, increases ROS production, and suppresses bacterial metabolic activity [33].

Although the mechanism of antimicrobial action of cannabinoids is not yet fully understood, Wassman et al. [57] suggested that this mechanism involves damage to the bacterial cell membrane. Blaskovich et al. [36] also showed that bactericidal concentrations of CBD against S. aureus inhibit the synthesis of proteins, DNA, RNA, and peptidoglycan.

CBD and CBG appear to disrupt the plasma membrane of Gram-positive bacteria by distinct mechanisms, as reported in several studies [36,39,43]. These compounds exhibit a bacteriostatic effect by inducing membrane hyperpolarization and disrupting ion channel function, which leads to the intracellular accumulation of mesosome-like structures [32,34]. Additionally, they can prevent bacteria-mediated pH reduction [32,35] and suppress the production of EPS. This suppression enhances the penetration of antibiotics, thereby improving the effectiveness of other antibacterial agents [33,35].

Galletta et al. [40] showed that the bactericidal effect of CBCA resulted from damage to the bacterial lipid membrane while maintaining the integrity of the peptidoglycan wall. This suggests an alternative mechanism of action that reduces the likelihood of existing or cross-antimicrobial resistance [40].

Cham et al. [37] demonstrated that THCBD had strong effectiveness against efflux pump-overexpressing strains. Efflux pumps play a key role in antibiotic resistance by expelling various antibiotics, either individually or cooperatively. Additionally, efflux pumps contribute to bacterial infection spread through biofilm formation by influencing physical–chemical interactions, mobility, gene regulation, and quorum sensing. They also release EPSs and harmful metabolites [78].

As research into the antibacterial properties of cannabinoids advances, exploring their potential synergy with other therapeutic agents becomes increasingly important. Co-therapy has long been a strategy for treating resistant bacterial infections, highlighting the need to investigate interactions between cannabinoids, particularly CBD, and broad-spectrum antibiotics in such treatments.

Polymyxin B is an antibiotic used in clinical settings to treat severe healthcare-associated infections caused by multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, especially those caused by P. aeruginosa, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae [79]. Polymyxin B exerts antibacterial activity through electrostatic interaction between its positive charge and the negative phosphate groups on lipid A in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. This destabilizes lipopolysaccharides or lipooligosaccharides, disrupting the bacterial cell envelope. However, resistance to polymyxin, both chromosomal and plasmid-mediated, is increasing and has been detected in various Gram-negative bacteria [79]. Several authors have studied the combination between polymyxin B and cannabinoids.

In the study by Abichabki et al. [30], CBD showed antibacterial activity against several Gram-negative bacteria, including multidrug-resistant strains (e.g., K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and A. baumannii), with concentrations below 4 μg/mL being effective when combined with polymyxin B [28]. In another study, Gildea et al. [42] showed that the growth of S. typhimurium was inhibited at very low doses of CBD–antibiotic co-therapy, specifically with 0.5 μg/mL ampicillin + 1 μg/mL CBD and 0.5 μg/mL polymyxin B + 1 μg/mL CBD. This synergistic antibacterial activity between polymyxin B and CBD was also shown by Hussein et al. [45]. Farha et al. [39] demonstrated that CBG, which was inactive against E. coli (with a concentration >128 μg/mL), exhibited significant potentiation when combined with a sublethal concentration of polymyxin B (1 μg/mL in the presence of 0.062 μg/mL polymyxin B). These studies suggest that the permeabilization of the outer membrane caused by polymyxin B is sufficient to allow the entry and antibacterial activity of cannabinoids (CBD and CBG).

Regarding the outcomes of co-therapy, Cham et al. [37] demonstrated additive effects of a semisynthetic phytocannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabidiol (THCBD, 4) with tetracycline, mupirocin, and penicillin G in S. aureus. Dihydrocannabidiol, (H2CBD) demonstrated synergistic or additive effects against E. faecalis and Bacillus cereus when combined with several antibiotics (tetracycline, gentamicin, ofloxacin, and chloramphenicol) [53]. In the work by Wassman et al. [57], CBD potentiated the effect of bacitracin against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus species, Listeria monocytogenes, and E. faecalis) but appeared ineffective against Gram-negative bacteria.

As cannabinoids are receiving significant research attention for their potential benefits in various applications, recent studies have observed their antimicrobial properties against the bacteria found in dental plaque. CBG showed antibacterial effects against Streptococcus mutans, the main aetiological agent of dental caries, inducing membrane hyperpolarization and preventing reduction in pH, which is normally caused by this microorganism and allows demineralization of enamel during the process of caries development [33]. Avraham et al. [34] concluded that the combination of triclosan and CBD demonstrated stronger antibacterial and anti-biofilm effects compared to each compound alone. Both compounds induced membrane hyperpolarization, reducing bacterial viability and adhesion. This combined treatment may be useful for preventing dental caries and oral inflammation [34]. Cannabinoid (CBD or CBG)-infused mouthwashes demonstrated similar bactericidal efficacy to chlorhexidine 0.2% [56].

4.2. Antiviral Activity of Cannabinoids—Recent Findings and Interpretation

Viruses are infectious agents that have the ability to invade the human body through a variety of routes, including respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and skin routes. Once inside the body, these agents use the host’s cells to replicate their genetic material, i.e., DNA or RNA, depending on the type of virus. Although the immune system is usually effective in fighting off most viral infections, in some cases, the virus is so aggressive that another method must be used because the immune system cannot eradicate the infection on its own [80].

Just as there is currently a shortage of antibiotics to fight bacteria, there is also a severe shortage of antivirals. In the last four years, the world has been forced to face an emerging infectious disease, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, due to the lack of therapies capable of fighting this infection and the mortality observed, associated with the excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins, interferons, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [81]. Studies have therefore been carried out on the activation of the endocannabinoid system as a possible treatment for this infection since the effects of cannabinoids on the immune system have the potential to limit the abnormal functioning of this system when the body is infected, thus reducing the mortality caused by this virus [80].

Regarding the antiviral effect of CDB, most in vitro studies within this scoping review are related to its potential antiviral effect against SARS-CoV-2. In accordance with several studies, CBD exhibited the highest antiviral activity against a panel of SARS-CoV-2 variants by reducing viral entry by affecting virus spike protein-mediated membrane fusion [55,56,58,64]. Van Breemen et al. [70] also reported that cannabinoid acids were found to be allosteric as well as orthosteric ligands with micromolar affinity for the spike protein.

The CB1 receptor, which is extensively distributed throughout the central nervous system, plays a key role in influencing viral infections in neural, lung, and liver tissues when activated by cannabinoid agonists. [82]. In certain viral infections, the activation of CB1 receptors can trigger signaling pathways that lower cellular calcium ion levels, leading to a disruption in the release of calcium-dependent enzymes, nitric oxide production, nitric oxide synthase activity, and pro-inflammatory mediators. These compounds contribute negatively by enhancing the host’s response to the viral infection and facilitating viral replication. The activation of CB2 receptors on immune cells modifies the immune response and impacts viral infections. CB2 receptors’ immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects can reduce immune activity, suppress inflammation, regulate cytokine production, and influence the migration of immune cells [81,83]. Δ9-THC is known to be a partial agonist for both endocannabinoid receptors, inducing psychotomimetic effects by activating the CB1 receptor while also influencing the immune system through its binding to CB2 receptors. In contrast, CBD plays a role in regulating immune responses, has minimal or no psychotomimetic effects, and functions as a CB1 receptor antagonist and a CB2 receptor agonist [84].

The anti-inflammatory effects of cannabinoids are mediated through various pathways, including the regulation of immune cell production, migration, and function (such as macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, dendritic cells, NK cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells). They also reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, IL-18, IFN-γ, TNF-α, MCP-1/CCL5, GM-CSF) and promote the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-11, TGF-β) [80].

Mahmud et al. [81] reviewed the pharmacological potential of cannabinoids on the SARS-CoV-2 virus and concluded that intranasal administration of CBD led to a decrease in the pro-inflammatory secretion of the cytokine IL-6, resulting in an improvement in symptoms associated with COVID-19. The authors also concluded that, in humans, oral administration of Δ9-THC and CBD significantly reduced TNF-α levels, with CBD identified as a PPARγ agonist. This action may contribute to its antiviral effects and help suppress the onset of the cytokine storm in COVID-19 infections. Additionally, CBD regulates fibroblast/myofibroblast activation and inhibits the development of pulmonary fibrosis, leading to improved lung function in patients recovering from the disease.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has evolved new strategies to manipulate host signaling pathways, such as the interferon pathway, to enhance its replication. While this provides an advantage to the virus, it poses a significant disadvantage to the population [85]. Nguyen et al. [63] found that CBD can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication by inducing host endoplasmic reticulum stress, increasing reactive oxygen species accumulation, and stimulating antiviral interferon production. It also enhances interferon-stimulated gene expression, suggesting the involvement of the interferon pathway in its antiviral effects. In later stages of infection, CBD and Δ9-THC reduce virus-induced cytokine release and immune cell recruitment, helping to prevent a cytokine storm. CBD, as a CB2 agonist, inhibits the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways, which are key drivers of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Thus, CBD shows potential as an antiviral agent that can both prevent viral replication in the early stages and suppress the immune response in later stages. Additionally, the cannabinoids CBGA and CBDA have been found to bind strongly to the spike protein, blocking viral infection [63,84].

Regarding other viruses, Marquez et al. [62] found that CBD affects cellular membranes, inhibiting the replication of Zika virus (ZIKV) and other viruses. ZIKV, primarily transmitted by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, causes neurological diseases like microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome. Despite recent outbreaks, there are no vaccines or specific treatments for ZIKV. The study demonstrated that CBD inhibits a range of structurally diverse viruses, suggesting it has broad-spectrum antiviral properties, making it a potential alternative in emergency situations during viral outbreaks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.3. Antifungal Activity of Cannabinoids–Recent Findings and Interpretation

Fungal infections, both superficial and systemic, have increased due to the emergence of various immunological disorders. Resistance to antifungal drugs has become a growing concern, highlighting the urgency of finding new therapeutic alternatives. Candida albicans is a pathogenic dimorphic fungus that opportunistically causes various types of infections in humans. Although only a few studies on the antifungal effect of CBD are available, there is agreement between authors concerning CBD antifungal activity against Candida sp, especially C. albicans. CBD inhibits the growth and formation of C. albicans biofilm and induces disorganization of mature biofilm [47,72,73,74,75]. The causes are still unclear, but there appears to be an inhibitory effect on the development of hyphae, which is recognized as a key pathogenic mechanism of C. albicans. Studies by Feldman et al. [73] reported that CBD repressed the expression of C. albicans virulence-associated genes (lipases, phospholipases, and cell wall proteins); enhanced the production of ROS, reducing the antioxidant defense genes SOD and causing mitochondrial dysfunction; and reduced intracellular ATP levels and subsequent apoptosis of C. albicans cells. CBD inhibited C. albicans biofilm formation by upregulating the DPP3 gene (associated with the biosynthesis of farnesol that inhibits biofilm formation) and downregulating ergosterol biosynthesis-associated genes (ERG11 and ERG20) [73]. Bahraminia et al. [74] reported that the inhibition of C. albicans by CBD was achieved through a combination of apoptosis and necrosis pathways. Additionally, this study demonstrated a synergistic effect of CBD combined with amphotericin B, enhancing its ability to inhibit the growth of C. albicans [67]. However, further studies are needed to reach clearer conclusions that could allow the use of C. sativa in fungal infections, mainly for external use.

5. Conclusions and Future Opportunities

The unique chemical properties of cannabinoids, combined with their interactions with existing therapies, contribute to their antimicrobial effects against a wide range of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

The data collected support the conclusion that cannabinoids exert their effects through multiple pathways, including the disruption of microbial membranes, modulation of immune responses, and interference with microbial virulence factors. The use of cannabinoids as alternative therapeutic options has demonstrated their potential to overcome the limitations of conventional antibiotics, offering a potential new approach to combating drug-resistant microorganisms, potentially reducing dependence on traditional antimicrobial agents that have become less effective. It also appears that the use of combinations of cannabinoids with other conventional drugs can potentially lead to a synergistic effect with improved therapeutic capabilities.

The scientific evaluation of the medical benefits of Cannabis sp. and its derivatives is hindered by several factors, including societal stigma, misinformation propagated by proponents of alternative medicine, legal restrictions, and health risks associated with Δ9-THC, particularly in children and adolescents. Nevertheless, the findings presented here underscore the importance of further investigating cannabinoid-based therapies, including their potential synergistic effects with existing antimicrobial agents. Equally important is the potential of combining cannabis-derived compounds with nanomedicine. This cutting-edge approach holds significant promise for addressing bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. By integrating the unique properties of cannabinoids and nanomaterials, this interdisciplinary strategy provides a novel pathway to enhance therapeutic outcomes against antimicrobial resistance and treatment-resistant pathogens. Further investigation of this promising avenue is warranted in the future.

Also, regarding the antibiofilm activity of CBD, more studies should focus on whether the antibiofilm effect is effective and assess its toxicity using in vivo models.

The pharmacological profiles of individual cannabis components and their mixtures with antibiotics, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, mode of action, elimination, and toxicity, need to be clearly defined. Further in vivo studies and preclinical trials with large participant groups are necessary. However, cannabis-based antimicrobial agents must meet strict regulatory requirements regarding quality, safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness, in line with good laboratory, manufacturing, and clinical/application practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms13020325/s1, Table S1. Search strategies used in the scoping review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.C. and C.P.; methodology, M.J.C., M.D.A., M.C., and M.C.M.; validation, M.J.C., M.C., I.L.C., and C.P.; formal analysis, M.D.A.; investigation, M.D.A.; resources, M.J.C. and C.P.; data curation, M.J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.C. and M.D.A.; writing—review and editing, M.J.C., M.D.A., M.C., I.L.C., M.C.M., and C.P.; visualization, M.C., I.L.C., and M.C.M.; supervision, M.J.C. and C.P.; project administration, M.J.C. and C.P.; funding acquisition, M.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

M. Carvalho acknowledges support from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) under the scope of the project UIDP/50006/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, D.-Y.; Patel, S.K.S.; Rasool, K.; Lone, N.; Bhatia, S.K.; Seth, C.S.; Ghodake, G.S. Bioinspired silver nanoparticle-based nanocomposites for effective control of plant pathogens: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.K.; Arfin, S.; Jha, S.K.; Kar, R.; Dey, A.; Gundamaraju, R.; Ashraf, G.M.; Gupta, P.K.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Abomughaid, M.M.; et al. Re-establishing the comprehension of phytomedicine and nanomedicine in inflammation mediated cancer signaling. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 1086–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhadrami, H.A.; Orfali, R.; Hamed, A.A.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Hassan, H.M.; Hassane, A.S.I.; Rateb, M.E.; Sayed, A.M.; Gamaleldin, N.M. Flavonoid-coated gold nanoparticles as efficient antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria—Evidence from in silico-supported in vitro studies. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutawa, A.B.; Ahmad, K.; Ali, A.; Hussein, M.Z.; Abdul Wahab, M.A.; Adamu, A.; Ismaila, A.A.; Gunasena, M.T.; Rahman, M.Z.; Hossain, M.I. Trends in nanotechnology and its potentialities to control plant pathogenic fungi: A review. Biology 2021, 10, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, T.; Adeel, M.; He, Z.; Umar, M.; Shakoor, N.; da Silva, W.; Elmer, W.; White, J.C.; Rui, Y. Nanotechnology and plant viruses: An emerging disease management approach for resistant pathogens. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6030–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocsoy, I.; Paret, M.I.; Ocsoy, M.A.; Kunwar, S.; Chen, T.; You, M.; Tan, W. Nanotechnology in plant disease management: DNA-directed silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide as an antibacterial against Xanthomonas perforans. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 8972–8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greatti, V.R.; Oda, F.; Sorrechia, R.; Kapp, B.R.; Seraphim, C.M.; Weckwerth, A.C.V.B.; Chorilli, M.; Silva, P.B.D.; Eloy, J.O.; Kogan, M.J.; et al. Poly-ε-caprolactone nanoparticles loaded with 4-Nerolidylcatechol (4-NC) for growth inhibition of Microsporum canis. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preethi, A.M.; Bellare, J.R. Concomitant effect of quercetin- and magnesium-doped calcium silicate on the osteogenic and antibacterial activity of scaffolds for bone regeneration. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-L.; Chiang, C.-E.; Lin, M.-C.; Kau, M.-L.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-S. Aerosolized hypertonic saline hinders biofilm formation to enhance antibiotic susceptibility of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaraj, C.; Vimal, S.; Ragavendran, C.; Priyadharsan, A.; Marimuthu, K.; Malafaia, G. Traditionally used medicinal plants mediate the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles: Methodological, larvicidal, and ecotoxicological approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-W.; Kwak, J.-H.; Jang, T.-S.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H.-W.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Grapefruit seed extract as a natural derived antibacterial substance against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkim, V.; Reddy, M.C.; Pallavali, R.R.; Reddy, K.R.; Reddy, C.V.; Inamuddin; Bilgrami, A.L.; Lomada, D. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and evaluation of their antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria and wound healing efficacy using a murine model. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Lackner, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Cannabis sativa: Properties, synthesis, mechanistic aspects, and applications. Chem. Eng. 2024, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Pandit, S.; Garnaes, J.; Tunjic, S.; Mokkapati, V.R.S.S.; Sultan, A.; Thygesen, A.; Mackevica, A.; Mateiu, R.V.; Daugaard, A.E.; et al. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles from Cannabis sativa (industrial hemp) and their capacity for biofilm inhibition. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 3571–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Guleria, S. Green synthesis of AgNPs using Cannabis sativa leaf extract: Characterization, antibacterial, anti-yeast and α-amylase inhibitory activity. Mat. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 3, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, N.M.; Moemen, Y.S.; Mohamed, S.H.; Fathy, G.; Ahmed, A.A.S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Ullah, S.; El Sayed, I.E.-T. Experimental and molecular docking studies of cyclic diphenyl phosphonates as DNA gyrase inhibitors for fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtary, P.; Pourhashem, Z.; Mehrizi, A.A.; Sala, C. Recent progress in the discovery and development of monoclonal antibodies against viral infections. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurawski, D.V.; McLendon, M.K. Monoclonal antibodies as an antibacterial approach against bacterial pathogens. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharga, K.; Kumar, L.; Patel, S.K.S. Recent advances in monoclonal antibody-based approaches in the management of bacterial sepsis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śledziński, P.; Zeyland, J.; Słomski, R.; Nowak, A. The current state and future perspectives of cannabinoids in cancer biology. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukowska, B. Current and Potential Use of Biologically Active Compounds Derived from Cannabis sativa L. in the Treatment of Selected Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Rhyu, H.; Yoon, K.; Lee, C.-D.; Lee, S. Beneficial effects of cannabidiol from Cannabis. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofs, L.; Sparo, M.D.; Sanchez Bruni, S.F. The antimicrobial effect behind Cannabis sativa. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas, J.A.; Wong, L.J.M.; Paulin, O.K.A.; Mazeh, A.C.; Hussein, M.H.; Li, J.; Velkov, T. The antimicrobial activity of cannabinoids. Antibiotics. 2020, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bow, E.W.; Rimoldi, J.M. The Structure-function relationships of classical cannabinoids: CB1/CB2 modulation. Perspect Med. Chem. 2016, 8, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Neira Agonh, D.; Lehmann, C. Antibacterial effects of Phytocannabinoids. Life 2022, 12, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISMA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Website. 2024. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abichabki, N.; Zacharias, L.V.; Moreira, N.C.; Bellissimo-Rodrigues, F.; Moreira, F.L.; Benzi, J.R.L.; Ogasawara, T.M.C.; Ferreira, J.C.; Ribeiro, C.M.; Pavan, F.R.; et al. Potential cannabidiol (CBD) repurposing as antibacterial and promising therapy of CBD plus polymyxin B (PB) against PB-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqawi, M.; Gallily, R.; Sionov, R.V.; Zaks, B.; Friedman, M.; Steinberg, D. Cannabigerol prevents quorum sensing and biofilm formation of Vibrio harveyi. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqawi, M.; Sionov, R.V.; Gallily, R.; Friedman, M.; Steinberg, D. Anti-bacterial properties of Cannabigerol toward Streptococcus mutans. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqawi, M.; Sionov, R.V.; Gallily, R.; Friedman, M.; Steinberg, D. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Cannabigerol against Streptococcus mutans. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, M.; Steinberg, D.; Barak, T.; Shalish, M.; Feldman, M.; Sionov, R.V. Improved anti-biofilm effect against the oral cariogenic Streptococcus mutans by combined triclosan/CBD treatment. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, T.; Sharon, E.; Steinberg, D.; Feldman, M.; Sionov, R.V.; Shalish, M. Anti-bacterial effect of cannabidiol against the cariogenic Streptococcus mutans bacterium: An in vitro study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Elliott, A.G.; Zhang, B.; Ramu, S.; Amado, M.; Lowe, G.J.; Hinton, A.O.; Pham, D.M.T.; Zuegg, J.; et al. The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Commun. Biol. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, P.S.; Deepika; Bhat, R.; Raina, D.; Manhas, D.; Kotwal, P.; Mindala, D.P.; Pandey, N.; Ghosh, A.; Saran, S.; et al. Exploring the antibacterial potential of semisynthetic phytocannabinoid: Tetrahydrocannabidiol (THCBD) as a potential antibacterial agent against sensitive and resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, G.; Jakus, J.; Baroud, S.; Gvirtz, R.; Rozenblat, S. Development of an effective acne treatment based on CBD and herbal extracts: Preliminary in vitro, ex vivo, and clinical evaluation. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 4474255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, M.A.; El-Halfawy, O.M.; Gale, R.T.; MacNair, C.R.; Carfrae, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Jentsch, N.G.; Magolan, J.; Brown, E.D. Uncovering the hidden antibiotic potential of Cannabis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletta, M.; Reekie, T.A.; Nagalingam, G.; Bottomley, A.L.; Harry, E.J.; Kassiou, M.; Triccas, J.A. Rapid antibacterial activity of cannabichromenic acid against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, H.S.; Loaiza-Oliva, M.; Martínez-Pabón, M.C.; Puerta-Suárez, J.; Téllez Corral, M.A.; Bueno-Silva, B.; Suárez, D.R.; Díaz-Báez, D.; Suárez, L.J. Antibiofilm and immune-modulatory activity of cannabidiol and cannabigerol in oral environments—In vitro study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gildea, L.; Ayariga, J.A.; Ajayi, O.S.; Xu, J.; Villafane, R.; Samuel-Foo, M. Cannabis sativa CBD extract shows promising antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhimurium and S. newington. Molecules 2022, 27, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gildea, L.; Ayariga, J.A.; Xu, J.; Villafane, R.; Robertson, B.K.; Samuel-Foo, M.; Ajayi, O.S. Cannabis sativa CBD extract exhibits synergy with broad-spectrum antibiotics against Salmonella enterica subsp. Enterica serovar typhimurium. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongsing, P.; Ngamwongsatit, N.; Kongart, C.; Nuiden, N.; Phairoh, K.; Wannigama, D.L. Cannabidiol demonstrates remarkable efficacy in treating multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis infections in vitro and in vivo. Trends Sci. 2024, 21, 8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Allobawi, R.; Levou, I.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Rao, G.G.; Li, J.; Velkov, T. Mechanisms underlying synergistic killing of polymyxin B in combination with cannabidiol against Acinetobacter baumannii: A metabolomic study. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.; Shademani, A.; Dosanjh, M.; Dietrich, C.; Pryjma, M.; Lambert, D.M.; Thompson, C.J. Combinations of Cannabinoids with silver salts or silver nanoparticles for synergistic antibiotic effects against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan Pillai, S.; Hassan Kera, N.; Kleyi, P.; de Beer, M.; Magwaza, M.; Ray, S.S. Stability, biofunctional, and antimicrobial characteristics of cannabidiol isolate for the design of topical formulations. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 2348–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz-Veiga, M.; Amorim, M.; Pinto-Ribeiro, I.; Oliveira, A.L.S.; Silva, S.; Pimentel, L.L.; Rodríguez-Alcalá, L.M.; Madureira, R.; Pintado, M.; Azevedo-Silva, J.; et al. Cannabidiol and cannabigerol exert antimicrobial activity without compromising skin microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinena, C.B.; Corleto, M.; Martínez, M.M.B.; Amiano, N.O.; García, V.E.; Maffia, P.C.; Tateosian, N.L. Antimicrobial effect of cannabidiol on intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 9, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinenghi, L.D.; Jonsson, R.; Lund, T.; Jenssen, H. Isolation, purification, and antimicrobial characterization of cannabidiolic acid and cannabidiol from Cannabis sativa L. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen, J.S.; Nielsen, C.K.; Pedersen, N.A.; Wimmer, R.; Sondergaard, T.E.; de Jonge, N.; Nielsen, J.L. Proteomic changes in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus exposed to cannabinoids. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1690–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Lavorgna, M.; Nugnes, R.; Orlo, E.; Isidori, M. Comparative assessment of antimicrobial, antiradical and cytotoxic activities of cannabidiol and its propyl analogue cannabidivarin. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, S.; Guo, M.; Xia, Y. Cannabidiol finds dihydrocannabidiol as its twin in anti-inflammatory activities and the mechanism. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 337 Pt 2, 118911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, V.; Vasudevan, K. Comparison of efficacy of Cannabinoids versus commercial oral care products in reducing bacterial content from dental plaque: A preliminary observation. Cureus 2020, 12, e6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valh, J.V.; Peršin, Z.; Vončina, B.; Vrezner, K.; Tušek, L.; Zemljič, L.F. Microencapsulation of cannabidiol in liposomes as coating for cellulose for potential advanced sanitary material. Coatings 2021, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, K.; Stahl, V. Cannabinoids infused mouthwash products are as effective as chlorhexidine on inhibition of total-culturable bacterial content in dental plaque samples. J. Cannabis Res. 2020, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassmann, C.S.; Højrup, P.; Klitgaard, J.K. Cannabidiol is an effective helper compound in combination with bacitracin to kill Gram-positive bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Guo, M.; Zou, L.; Wang, Q.; Xia, Y. 8,9-Dihydrocannabidiol, an alternative of cannabidiol, its preparation, antibacterial and antioxidant ability. Molecules 2023, 28, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, Z.; Sun, Y.; Deng, D.; Su, K.; Li, J.; Yan, Z.; Wang, X.; Cao, J.; Zheng, W.; et al. Discovery of novel cannabidiol derivatives with augmented antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 141, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, N.; Pitakbut, T.; Schöfbänker, M.; Kühn, J.; Hrincius, E.R.; Ludwig, S.; Hensel, A.; Kayser, O. Cannabigerol and cannabicyclol block SARS-CoV-2 cell fusion. Planta Med. 2024, 90, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.V.L.; Marques, D.P.A.; Clarindo, F.A.; Avendaño-Villarreal, J.A.; Guerra, F.S.; Fernandes, P.D.; dos Santos, E.N.; Gusevskaya, E.V.; Kohlhoff, M.; Moreira, F.A.; et al. Synthesis of cannabidiol-based compounds as ACE2 inhibitors with potential application in the treatment of COVID-Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 260, 115760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, A.B.; Vicente, J.; Castro, E.; Vota, D.; Rodríguez-Varela, M.S.; Lanza Castronuovo, P.A.; Fuentes, G.M.; Parise, A.R.; Romorini, L.; Alvarez, D.E.; et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral effect of cannabidiol against enveloped and nonenveloped viruses. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 9, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.C.; Yang, D.; Nicolaescu, V.; Best, T.J.; Gula, H.; Saxena, D.; Gabbard, J.D.; Chen, S.-N.; Ohtsuki, T.; Friesen, J.B.; et al. Cannabidiol inhibits SARSCoV-2 replication through induction of the host ER stress and innate immune responses. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabi6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawełczyk, A.; Nowak, R.; Gazecka, M.; Jelińska, A.; Zaprutko, L.; Zmora, P. Novel molecular consortia of cannabidiol with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit emerging Coronaviruses’ entry. Pathogens 2023, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitakbut, T.; Nguyen, G.N.; Kayser, O. Activity of THC, CBD, and CBN on human ACE2 and SARS-CoV1/2 main protease to understand antiviral defense mechanism. Planta Med. 2022, 88, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H.U.; Yalcin, H.A.; Köm, D.; Aksoy, Ö.; Abaci, I.; Ekiz, A.T.; Serhatli, M.; Onarici, S. Antiviral effect of cannabidiol on K18-hACE2 transgenic mice infected with SARS-CoV-J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.; Park, J.G.; Cho, K.H.; Choi, P.; Kim, T.; Ham, J.; Lee, J. Assessment of antiviral potencies of cannabinoids against SARS-CoV-2 using computational and in vitro approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 168, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, S.; Barata, P.; Charmier, A.; Lehmann, I.; Rodrigues, S.; Melosini, M.M.; Pais, P.J.; Sousa, A.P.; Teixeira, C.; Santos, I.; et al. Cannabidiol and terpene formulation reducing SARS-CoV-2 infectivity tackling a therapeutic strategy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 841459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburello, M.; Salamone, S.; Anceschi, L.; Governa, P.; Brighenti, V.; Morellini, A.; Rossini, G.; Manetti, F.; Gallinella, G.; Pollastro, F.; et al. Antiviral activity of cannabidiolic acid and its methyl ester against SARS-CoV-2. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breemen, R.B.; Muchiri, R.N.; Bates, T.A.; Weinstein, J.B.; Leier, H.C.; Farley, S.; Tafesse, F.G. Cannabinoids block Cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 and the emerging variants. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargari, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Nowroozi, A.; Morowvat, M.H.; Nakhaei, E.; Rezagholi, F. The inhibitory effects of the herbals secondary metabolites (7α-acetoxyroyleanone, curzerene, incensole, harmaline, and cannabidiol) on COVID-19: A molecular docking study. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2024, 18, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahraminia, M.; Cui, S.; Zhang, Z.; Semlali, A.; Le Roux, É.; Giroux, K.A.; Lajoie, C.; Béland, F.; Rouabhia, M. Effect of cannabidiol (CBD), a cannabis plant derivative, against Candida albicans growth and biofilm formation. Can. J. Microbiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Sionov, R.V.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Anti-biofilm activity of cannabidiol against Candida albicans. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, M.; Gati, I.; Sionov, R.V.; Sahar-Helft, S.; Friedman, M.; Steinberg, D. Potential combinatory effect of cannabidiol and triclosan incorporated into sustained release delivery system against oral candidiasis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, P.; Zemliana, N.; Zaffran, I.; Etzion, T.; Sionov, R.V.; Steinberg, D.; Mechoulam, R.; Kogan, N.M.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Antifungal properties of abnormal cannabinoid derivatives: Disruption of biofilm formation and gene expression in Candida species. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 209, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, J. Biofilms: The microbial “Protective Clothing” in extreme environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiagha, M.N.; Kafil, H.S. Efflux pumps and microbial biofilm formation. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2023, 112, 105459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatri, G.; Tadi, P. Polymyxin; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lucaciu, O.; Aghiorghiesei, O.; Petrescu, N.B.; Mirica, I.C.; Benea, H.R.C.; Apostu, D. In quest of a new therapeutic approach in COVID-19: The endocannabinoid system. Drug Metab. Rev. 2021, 53, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.; Hossain, M.S.; Faiz Ahmed, A.T.M.; Islam, Z.; Sarker, E.; Islam, R. Antimicrobial and antiviral (SARS-CoV-2) potential of cannabinoids and Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2022, 26, 7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Poorten, D.; Shahidi, M.; Tay, E.; Sesha, J.; Tran, K.; McLeod, D.; Milliken, J.S.; Ho, V.; Hebbard, L.W.; Douglas, M.W.; et al. Hepatitis C virus induces the cannabinoid receptor 1. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.M.; Kaplan, B.L. Immune responses regulated by cannabidiol. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020, 5, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sea, Y.L.; Gee, Y.J.; Lal, S.K.; Choo, W.S. Cannabis as antivirals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxac036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znaidia, M.; Demeret, C.; van der Werf, S.; Komarova, A.V. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 evasion: Interferon pathway and therapeutic options. Viruses 2022, 14, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).