Simple Summary

The Güiña (Leopardus guigna), the smallest Neotropical feline, is found in central and southern Chile and western Argentina. This communication documents the first known instance of a güiña swimming in a marine environment. The observation, made in the remote Refugio Channel in Northern Patagonia, Chile, suggests that this elusive species may utilize marine environments during their search for food, particularly during winter when terrestrial prey is scarce.

Abstract

The Güiña (Leopardus guigna), the smallest Neotropical feline, inhabits central and southern Chile and western Argentina. This communication reports the first documented instance of a güiña swimming in a marine environment, observed in the Refugio Channel, which separates Refugio Island from the mainland in Northern Patagonia, Chile. In April 2023, a local resident recorded video footage of a güiña swimming near the eastern shore of the channel, emerging from the water, shaking off, and climbing a tree to groom itself. This observation suggests that the güiña might use the seacoast when searching for food, particularly during periods of low terrestrial prey availability during the winter. The ability of the güiña to adapt to such environments underscores the species’ ecological flexibility, previously undocumented in this context, and highlights the need for integrating marine resources into the species’ conservation strategies. The video’s quality is limited due to the simplicity of the recording device, but it provides crucial visual evidence of this behavior.

1. Introduction

The güiña (Leopardus guigna), also known as the kodkod, is the smallest member of the genus Leopardus, a group of small and medium-sized Neotropical felines within the “ocelot lineage” [1]. This species is distributed primarily across central and southern Chile from Los Vilos in the Coquimbo region to Laguna San Rafael in the Aysén region and extends to the westernmost areas of Argentina [2,3,4,5]. The güiña is known for its elusive nature and cryptic behavior, making it one of the least studied felines in the region. Morphologically, the güiña exhibits two main phenotypes: a common spotted form with yellowish fur and dark circular spots, and a rarer melanistic form characterized by entirely black fur [6,7,8].

Güiñas are typically associated with dense forest habitats, exhibiting nocturnal and crepuscular activity patterns [9,10]. Rivers and lakes often act as natural barriers influencing the movement of the species, gene flow, and hunting strategies [11]. Despite the species’ adaptability, knowledge about the güiña’s swimming capabilities, particularly in marine environments, is extremely limited. While there are documented cases of other felids, such as Leopardus geoffroyi and Leopardus pardalis, using freshwater habitats [12,13,14,15], güiñas had not previously been observed swimming in marine environments. This communication documents the first known instance of a güiña swimming in the Refugio Channel in Northern Patagonia, Chile, providing new insights into the species’ ecological plasticity and its potential to utilize marine resources.

The flexibility in habitat uses and ecological adaptation observed in Leopardus guigna is reminiscent of the adaptations seen in other elusive felid species, such as Leopardus geoffroyi and the snow leopard (Panthera uncia). Comprehensive works on the biology, behavior, and conservation status of the snow leopard have highlighted the species’ ability to survive in harsh and isolated environments, aided by breakthroughs in non-invasive genetics, camera traps, and GPS-satellite collaring [15,16,17]. In field studies of recent decades, camera traps have acquired particular significance for predators, including felines.

Like the snow leopard and Leopardus geoffroyi, the güiña’s ability to adapt to a variety of environments, including potentially utilizing marine resources, underscores the importance of advanced monitoring techniques and conservation strategies tailored to the species’ unique ecological requirements [9,16].

2. Materials and Methods

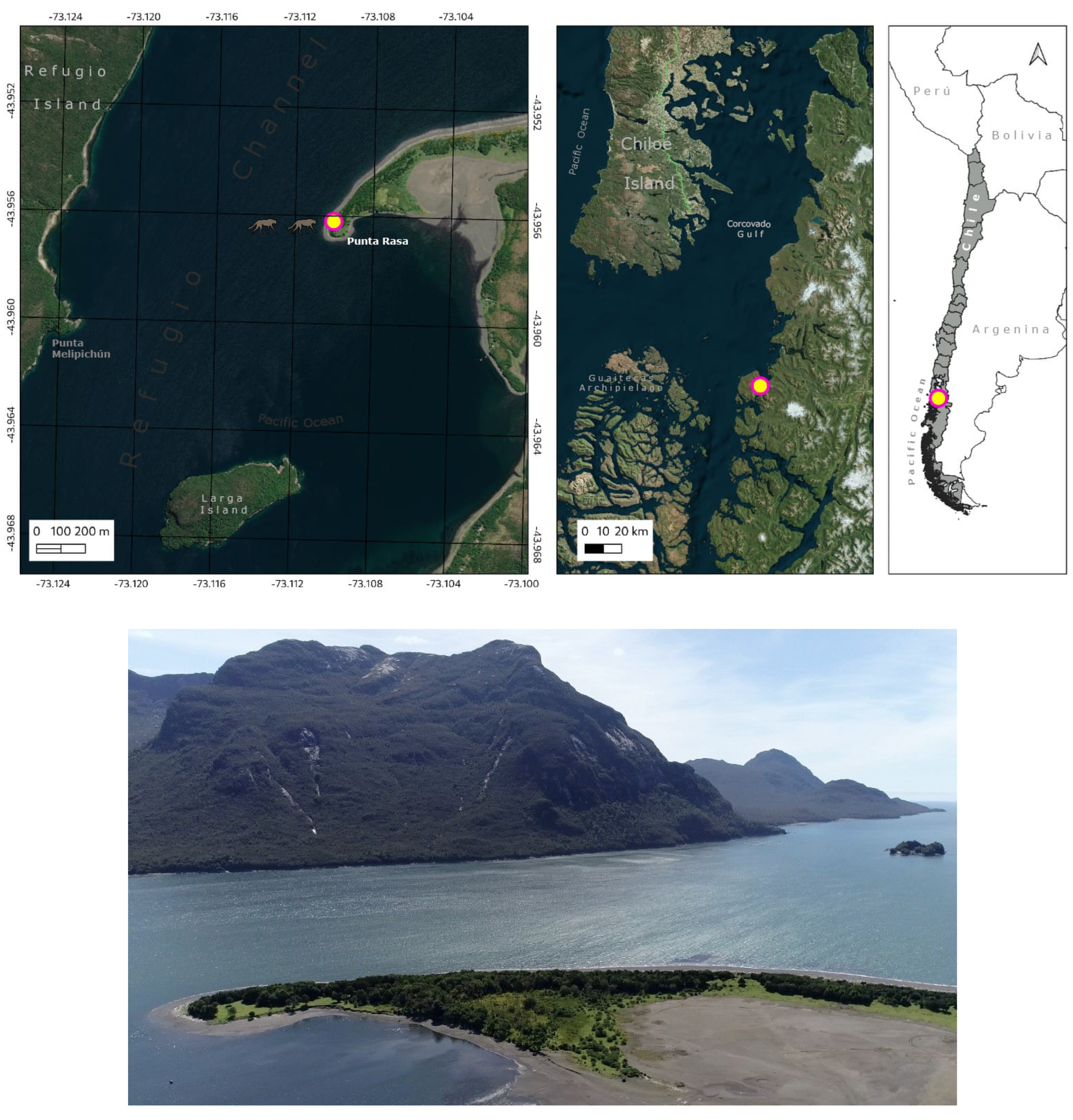

This observation was part of a broader study in the area surrounding the Refugio Channel (Punta Rasa: 43°57′22.3″ S–73°06′37.2″ W) located just north of Puerto Santo Domingo, in the Aysén Region of southern Chile, within boundaries of the Multiple Use Marine Protected Area known as (AMCP-MU Pitipalena—Añihue).

The rare sighting of the güiña swimming in the channel occurred on 7 April 2023, when a local resident, responsible for regularly checking the camera traps, was conducting one of his routine inspections. During this visit, he unexpectedly encountered the kodkod in the water and recorded the event using a basic mobile phone. Although the video footage is of limited quality due to the simplicity of the device (Video S1), it provides crucial visual evidence of this previously undocumented behavior. Future monitoring efforts will focus on improving the quality and coverage of the camera traps to better document such rare behaviors.

3. Results

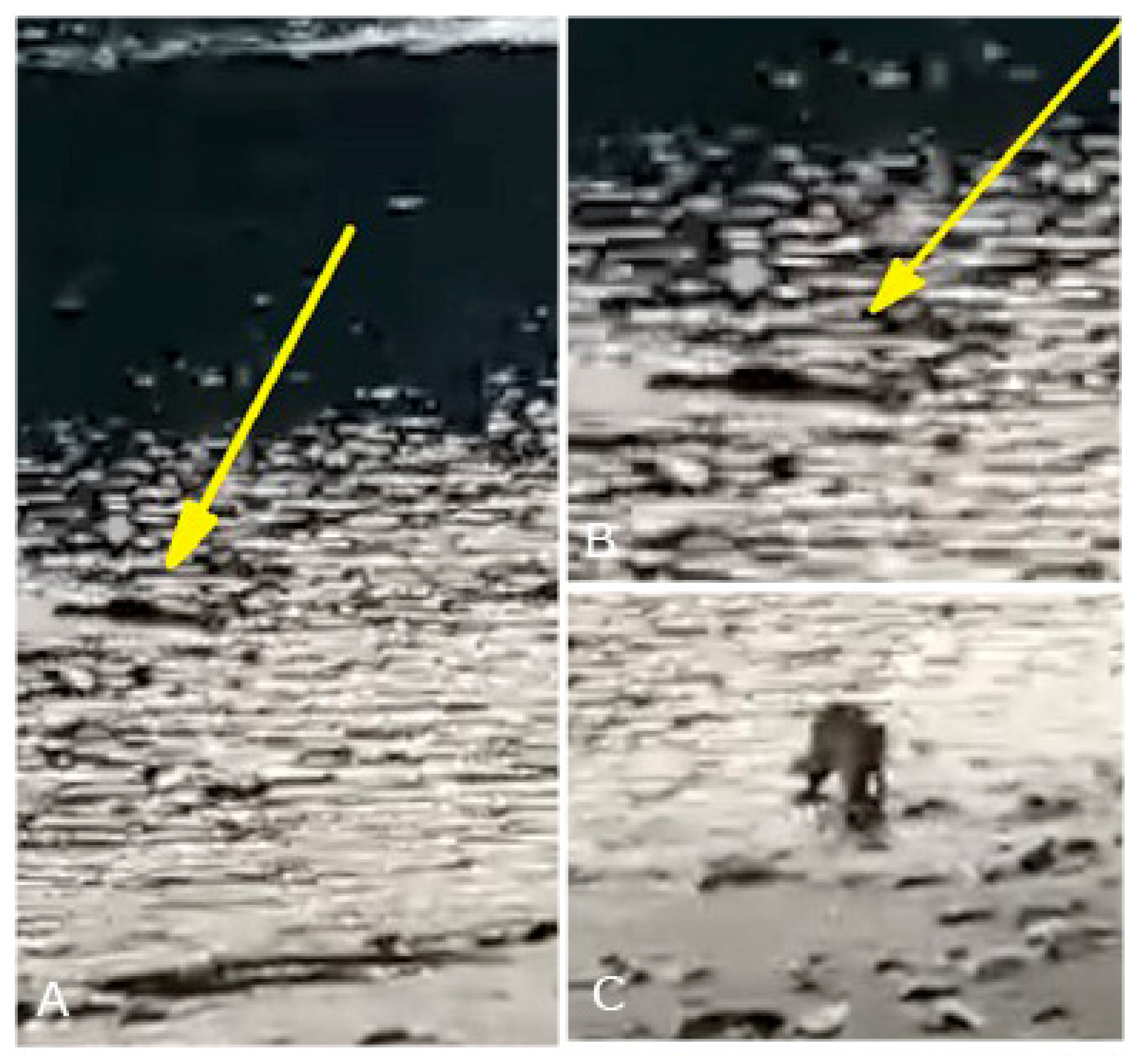

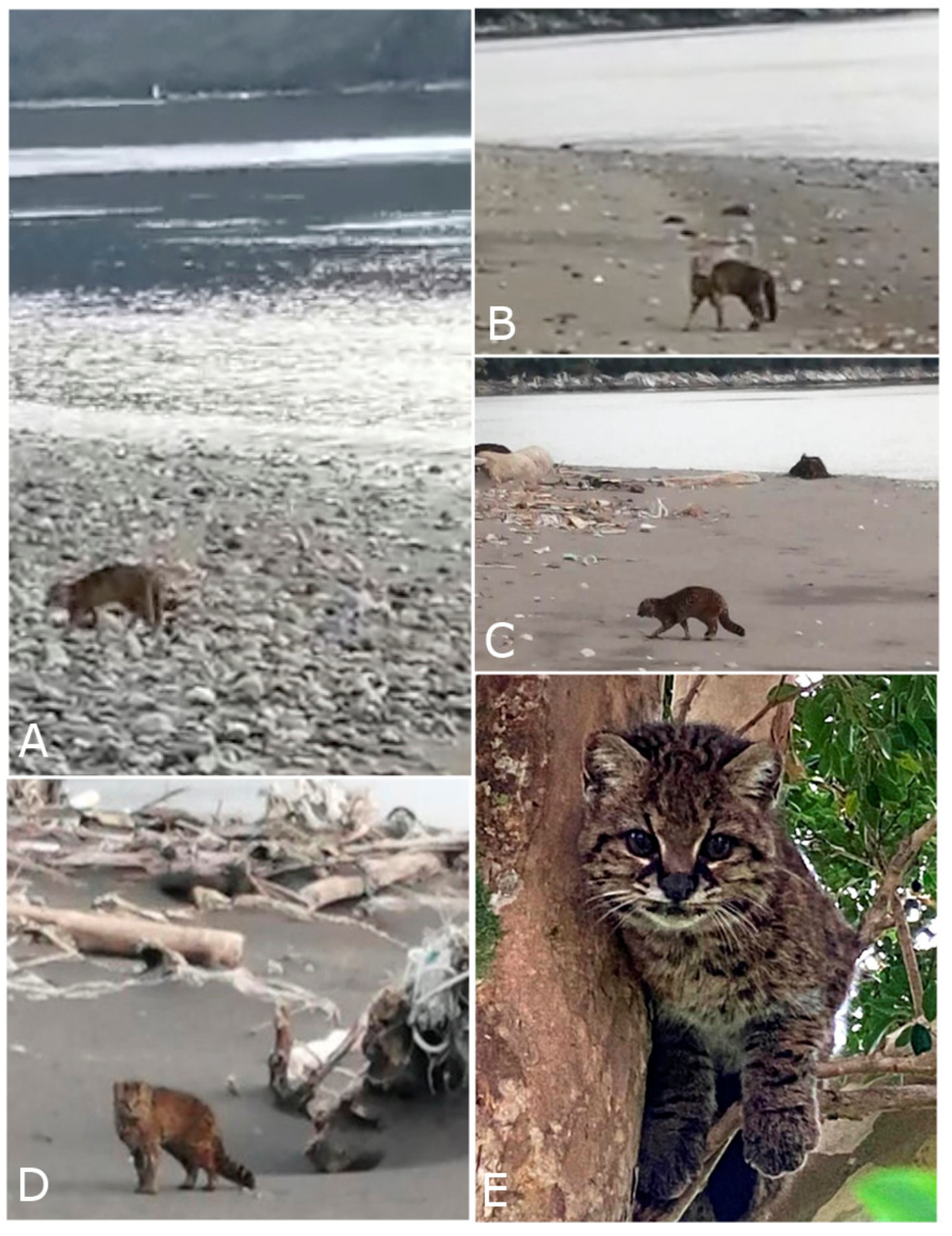

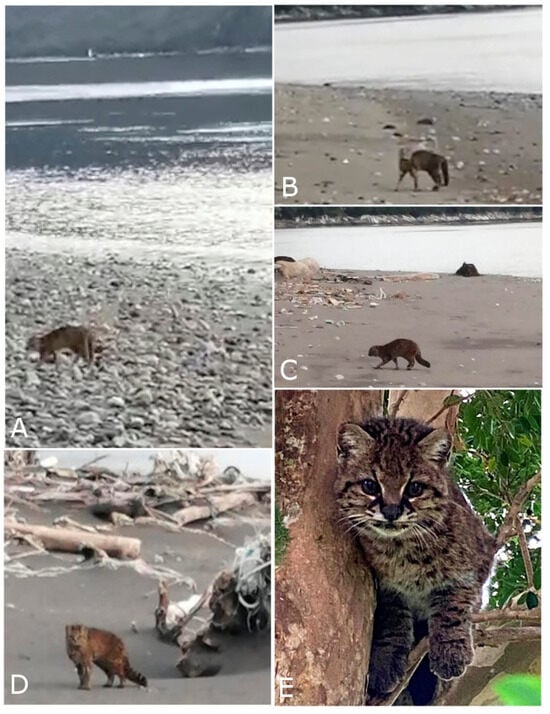

This is the first documented case of a güiña in a marine environment. The observed güiña exhibited a mottled phenotype and appeared to be in good health, although its sex and age remain undetermined. The individual was observed swimming in the Refugio Channel (Figure 1) and then emerging on the eastern coast (Figure 2). This happened in the middle of the day from 2.00 pm to 3:00 pm during a casual and unscheduled observation. After exiting the water, the güiña shook itself, crossed a strip of beach of about 35 m from the tide line to the coastal forest (Figure 3A–D), and climbed a tree where it groomed itself (Figure 3E). The possibility of having accidentally fallen into the water was rejected given the gently sloping conditions in a large sector of the coastline surrounding the observation.

Figure 1.

Upper: location of the study area and observation site in the Aysén Region, southern Chile. Yellow-pink dots mark the exact location of the record; the cat figure (brown) represents the güiña and its swimming direction. Lower: aerial view of the study area.

Figure 2.

Sequence of still frames (screenshots from the video) showing the güiña swimming and emerging from the water. (A). Güiña swimming; (B). a close-up of photo A; (C). güiña emerging from the water. The video is available in the Supplementary Material (Video S1).

Figure 3.

The güiña on the beach and later in a tree in the area. (A). In the first screenshot, the güiña is seen with Refugio Island in the background; (B–D). the güiña walking after emerging from the water; (E). the güiña in the tree. Screenshots taken from the video (Video S1).

4. Discussion

This sighting marks the first known documentation of Leopardus guigna swimming in a marine environment, significantly broadening our understanding of the species’ ecological adaptability. The observation was made in an extremely remote and sparsely populated region of Patagonia, far from any urban centers (Figure 1). Given the species’ cryptic nature and the remoteness of the observation site, documenting such an unusual behavior is extraordinarily unlikely, which underscores the scientific importance of this finding.

Traditionally, the güiña has been associated with dense forest habitats, where its nocturnal and crepuscular behavior has made it particularly challenging to study [18,19,20,21]. However, this individual’s ability to swim in a marine environment suggests a possible adaptation to the unique conditions of the Northern Patagonian archipelago. Existing information about the güiña’s swimming behavior is limited, and previously documented observations have only referred to freshwater environments on the continent [12]. While the exact reasons for the güiña’s entry into the sea remain speculative, eventual swimming from the mainland and Refuge Island via the narrowest part of the channel (approximately 800 m, as shown in Figure 1) may be a possibility. This raises the question of its presence on other islands in the Northern Patagonian archipelago, particularly the Guaitecas Islands (44° S–74° W) [18,22]. Preliminary findings, including camera trap recordings from the surrounding continental region, indicate that the species regularly inhabits this area (Guzmán and Sielfeld in preparation).

The Refugio Channel (Figure 1), where this sighting occurred, hosts a rich diversity of marine life, including Imperial Cormorants (Leucocarbo atriceps) and Dominican Gulls (Larus dominicanus), which in the region’s feed on species associated to the kelp forests (Macrocystis pyrifera) [23]. It is possible that the güiña could prey at least occasionally on these and other littoral birds, particularly during winter when terrestrial prey may be less accessible due to snow cover. This behavior is consistent with the dietary flexibility observed in other terrestrial carnivores of Southern Patagonia, such as the Culpeo (Lycalopex culpaeus) and Chilla (Lycalopex griseus), which have been documented incorporating marine prey into their diets during periods of scarcity [12,24,25,26]. Although little is known about the predatory behavior of the güiña, this species, despite its small size, is considered a top predator, preying on small mammals, birds, and reptiles, which are all species significantly smaller than the cat itself [8,16,27,28,29,30,31]. Additionally, recent photographic evidence shows the species preying upon Pudu puda in southern Chile [32]. Thus, these new data not only expand our understanding of the güiña’s habitats but also its trophic niche.

Moreover, the ability of the güiña to swim aligns with behaviors observed in other felids in different contexts. For example, Leopardus geoffroyi and Leopardus pardalis have been observed swimming in rivers and lakes, using these environments as movement corridors or hunting grounds. Similarly, the Puma (Puma concolor) has been documented crossing rivers and lakes within its range, demonstrating significant swimming capabilities [10,11,12,15]. These parallels suggest that the güiña’s behavior may not be as anomalous as it first appears, indicating a broader pattern of aquatic adaptability among small felids.

While the video quality is limited due to the use of a basic mobile phone, the significance of this record lies in the rarity of the event and the direct evidence of previously undocumented behavior. Future research could benefit from more advanced recording equipment or enhanced camera traps to capture higher-quality footage, allowing for more detailed analysis of such behaviors. Continued monitoring of the region, especially using camera traps and other non-invasive methods, would be essential to gather more comprehensive data on the güiña’s behavior in marine environments and its potential use of biological corridors.

The potential crossing of the Refugio Channel by a güiña also raises intriguing questions about the species’ distribution and gene flow in the region. The possibility that güiñas might inhabit nearby islands, such as Refuge Island, has not been previously considered in phylogenetic studies [33]. If future studies confirm the presence of güiñas on these islands, it could indicate a previously unrecognized pattern of island colonization, suggesting that the species is more widely distributed in the Northern Patagonian archipelago than previously thought. This would also imply a higher degree of genetic flow between populations than currently assumed.

5. Conclusions

This communication provides the first evidence of a güiña in a marine environment. The eventual güiña’s ability to utilize marine resources, particularly during periods of low terrestrial prey availability, suggests a greater degree of ecological adaptability than previously recognized. Further research is needed to explore the extent of this behavior and its implications for the conservation of Leopardus guigna, particularly in the context of the Northern Patagonian archipelago.

This finding underscores the importance of including marine littoral environments in the conservation strategies for the güiña [20,21,34,35,36]. Given that the species is classified as “Near Threatened” by the Chilean Ministry of the Environment [37] and “Vulnerable” by the IUCN [19], it is crucial that conservation efforts consider not only fragmented or degraded terrestrial habitats but also the marine resources and corridors that could be vital for the species’ survival. The güiña’s adaptability to these environments suggests that its ecology is more complex and varied than previously understood, reinforcing the need for continued research and comprehensive conservation strategies that incorporate both terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani14192879/s1: Video S1: Güiña_Video.

Author Contributions

J.C.C. recorded the video of the güiña. W.S. and J.A.G. reviewed the footage, drafted the manuscript, and edited the images. A.C. provided literature and a final review of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The video evidence of the kodkod swimming in the Refugio Channel is available as Supplementary Materials upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Multiple Use Marine Protected Area “AMCP-MU Pitipalena—Añihue” for their assistance during the fieldwork. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of the local communities in Puerto Santo Domingo. Finally, we extend our gratitude to the Vice-Rectorate of Research and Development of the University of Concepción through Project VRID Nº220.412.052-INI. Likewise, I would like to express my gratitude to the Los Angeles campus for their support in the creation of this manuscript, for the facilities provided to write it, and for the support during the fieldwork, making its publication possible (Direccion General, Dpto. De Ciencias Básicas and Escuela de Educación).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nascimento, F.G.; Jilong, C.; Feijó, A. Taxonomic revision of the pampas cat Leopardus colocola complex (Carnivora: Felidae): An integrative approach. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 191, 575–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunquist, M.E.; Sunquist, F. Wild Cats of the World; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Redford, K.; Eisenberg, J. Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 2. The Southern Cone: Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; 430p.

- Dunstone, N.; Freer, R.; Acosta-Jamett, G.; Durbin, L.; Wyllie, I.; Mazzolli, M.; Scott, D. Uso del hábitat, actividad y dieta de la guiña (Oncifelis guigna) en el Parque Nacional Laguna San Rafael, XI Región, Chile. Boletín Del Mus. Nac. De Hist. Nat. 2002, 51, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, C.; Larraguibel-González, C.; Cepeda-Mercado, A.A.; Vial, P.; Sanderson, J. New records of Leopardus guigna in its northern-most distribution in Chile: Implications for conservation. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2020, 93, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, W.H. The Mammals of Chile; Field Museum of Natural History: Chicago, IL, USA, 1943; Volume 30, p. l–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cuyckens, G.A.E.; Morales, M.M.; Tognelli, M.F. Assessing the distribution of a Vulnerable felid species: Threats from human land use and climate change to the kodkod Leopardus guigna. Oryx 2014, 49, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstone, N.; Durbin, L.; Wyllie, T.I.; Freer, R.; Acosta, G.; Mazzolli, M.; Rose, S. Spatial organization, ranging behaviour, and habitat use of the kodkod (Oncifelis guigna) in southern Chile. J. Zool. 2002, 257, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, J.; Sunquist, M.E.; Iriarte, A. Natural history and landscape-use of guignas (Oncifelis guigna) on Isla Grande de Chiloé, Chile. J. Mammal. 2002, 83, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibes-Mateos, M.; Díaz-Ruiz, F.; Caro, J.; Ferreras, P. Activity patterns of the vulnerable guiña (Leopardus guigna) and its main prey in the Valdivian rainforest of southern Chile. Mamm. Biol. 2014, 79, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Muñoz, P.A.; Guzmán, B.C. Overcoming barriers: Novel records of swimming behavior in Leopardus guigna. Gayana 2022, 86, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.E.; Franklin, W.L. Feeding and Spatial Ecology of Felis geoffroyi in Southern Patagonia. J. Mammal. 1991, 72, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, T.A.; Hernández, F.; de la Maza, M.; Bonacic, C. Güiña (Leopardus guigna) preys on cavity-nesting nestlings. Rev. Chil. De Hist. Nat. 2013, 86, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, P.G. Comparative Ecology of Ocelot (Felis pardalis) and Jaguar (Panthera onca) in a Protected Subtropical Forest in Brazil and Argentina. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Elbroch, L.M.; Quigley, H.B. Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Freer, R.A. The Spatial Ecology of the Güiña (Oncifelis guigna) in Southern Chile. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Durham, Durham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam, A.J.; Jenks, K.E.; Tantipisanuh, N.; Chutipong, W.; Ngoprasert, D.; Gale, G.A.; Steinmetz, R.; Sukmasuang, R.; Bhumpakphan, N.; Grassman, L.I., Jr.; et al. Terrestrial activity patterns of wild cats from camera-trapping. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2013, 61, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsohn, J.A.; Porter, C.E. Catálogo metódico de los mamíferos chilenos existentes en el Museo de Valparaíso en Diciembre de 1905. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1908, 12, 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group: Gland, Switzerland, 1996; 383p. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, B.C.; González, M.J.; Palma, N.; Guerrero, J.; Muñoz, P. New records of Leopardus guigna tigrillo and Lycalopex culpaeus in Placilla de Peñuelas, Chile, and threats to their conservation. Therya Notes 2022, 3, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, N.; Hernández, F.; Laker, J.; Gilabert, H.; Petitpas, R.; Bonacic, C.; Gimona, A.; Hester, A.; MacDonald, D.W. Forest cover outside protected areas plays an important role in the conservation of the Vulnerable guiña Leopardus guigna. Oryx 2013, 47, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housse, R. Animales Salvajes de Chile en su Clasificación Moderna; Ediciones de la Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1953; 189p. [Google Scholar]

- Tobar, C.N.; Carmona, D.; Rau, J.R.; Cursach, J.A.; Vilugron, J. Winter diet of the imperial cormorant (Phalacrocorax atricepcs) (Aves: Suliriformes) in Caullín Bay, Chiloé, southern Chile. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2019, 54, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel, R.; Jaksic, F. Ecología de los cánidos sudamericanos: Una revisión. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1988, 61, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Novaro, J.A. Pseudalopex culpaeus. Mamm. Species 1997, 558, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.J.; Gozzi, A.C.; Macdonald, D.W.; Gallo, E.; Centrón, D.; Cassini, M.H. Interactions of exotic and native carnivores in an ecotone: The coast of the Beagle Channel, Argentina. Polar Biol. 2010, 33, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, P.; Roa, A. Relaciones tróficas entre Oncifelis guigna, Lycalopex culpaeus, Lycalopex griseus, y Tyto alba en un ambiente fragmentado de la zona central de Chile. Mastozool. Neotrop. 2005, 12, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira-Arce, D.; Vergara, P.M.; Boutin, S.; Simonetti, J.A.; Briceño, C.; Acosta-Jamett, G. Native Forest replacement by exotic plantations triggers changes in prey selection of mesocarnivores. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 192, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, R.A.; Corrales, S.E.; Rau, J.R. Prey of the güiña (Leopardus guigna) in an Andean mixed southern beech forest, southern Chile. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 2018, 53, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, A.; Quintana, V.; Fierro, A. Trophic relations among predators in a fragmented environment in southern Chile. Gest. Ambient. 2005, 11, 31–42. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281497731_Trophic_relations_among_predators_in_a_fragmented_environment_in_southern_Chile (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Galuppo, S.E. Diet and Activity Patterns of Leopardus guigna in Relation to Prey Availability in Forest Fragments of the Chilean Temperate Rainforest. Master Thesis, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, Falcon Heights, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, M.; Guzmán, B.C. An unusually big challenge: First record of Leopardus guigna preying upon Pudu puda. Mammalia 2022, 86, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, C.; Sanderson, J.; Bennett, M.; Johnson, W.E.; Hoelzel, R.; Dunstone, N.; Freer, R.; Ritland, K.; Poulin, E. Phylogeography and population history of Leopardus guigna, the smallest American felid. Conserv. Genet. 2014, 15, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetti, M.; Dirzo, R. Ecological and evolutionary consequences of living in a defaunated world. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 163, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.; Gálvez, N.; Gimona, A.; Laker; Bonacic, C. Activity patterns by two colour morphs of the vulnerable guiña Leopardus guigna (Molina 1782) in temperate forests of southern Chile. Gayana 2015, 79, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.W.; Loveridge, A.J.; Nowell, K. Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (MMA). Decreto Supremo 42. Séptimo Proceso Clasificación de Especies Según su Estado de Conservación; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente: Santiago, Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).