Simple Summary

Veterinary nurses and technicians experience burnout, which affects their mental and physical health, the likelihood of leaving their job, and their quality of work. Burnout is caused by workplace issues, and existing research has identified specific causes in veterinary nurses and technicians. But little is known about how to address these issues within veterinary clinics in ways that are both effective and feasible. To address this gap, we consulted a panel of 40 veterinary nurse and technician leadership or wellbeing experts to seek their opinions on the challenges to addressing burnout and recommended management approaches. Responses were collected via two anonymous surveys between October 2024 and January 2025. The lack of, or unclear, regulation, poor leadership knowledge, poor team culture, an unwillingness to change, and existing burnout were found to make burnout management more difficult. Thirty-nine possible solutions, with recommended actions, were developed. These focused on improving communication, progression pathways, delegation, and leadership. Panel experts rated the proposed solutions as being highly, or very highly effective. When making changes in the workplace, current workplace problems, such as poor team culture and poor leadership, need to be considered first, as these will reduce the likelihood of success.

Abstract

Veterinary nurses and technicians are at risk of burnout, which negatively impacts mental and physical health, turnover, and patient care. Workplace contributors to burnout have been identified in this population, but little is known about best practice management strategies. This study used the Delphi method to explore barriers to addressing burnout and develop expert recommendations for workplace management strategies. Forty participants with a minimum of 5 years’ industry experience in leadership, or wellbeing, were recruited via purposive sampling from the USA, UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Participants completed two anonymous, online, mixed-methods surveys between October 2024 and January 2025. Qualitative survey data were analysed using content analysis to identify codes and categorise solutions. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Barriers to addressing burnout included industry-wide barriers, such as lack of, or unclear, regulation and lack of leadership knowledge, and clinic-specific barriers, such as poor team culture, unwillingness for change, and existing burnout. Thirty-nine solutions were developed and rated as being highly, or very highly effective. These focused on themes such as improving communication, developing progression pathways, and providing leadership training and support. Existing workplace barriers must be evaluated prior to selecting strategies, to maximise effectiveness in specific contexts.

1. Introduction

Veterinary team members are prone to burnout, with veterinary nurses and technicians (VN/Ts) at particular risk []. The existing body of evidence on burnout in veterinarians and the unique contributors to burnout in their role is growing [,], however, research specific to burnout in VN/Ts is lacking []. A recent study found that VN/Ts were twice as likely to experience high/very high levels of burnout compared to the general population, with exhaustion being a key contributor []. The same study identified that having a good work-life balance was the biggest predictor of low burnout levels []. Burnout has well documented negative physical and mental health consequences for the individual, with potential welfare implications for veterinary patients under their care. Burnout is also a known contributor to intentions to leave, thus leading to increased staff turnover and increased economic costs for veterinary practice owners [,,]. Effective prevention and management of burnout within VN/Ts is, therefore, critical to ensuring team wellbeing, business sustainability, and patient outcomes.

Burnout is defined as a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress which has not been adequately managed [] and is, therefore, considered an occupational health issue. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), a United Nations agency that sets international labour guidelines for its 187 member states, a safe and healthy work environment is a fundamental right for employees []. Furthermore, the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines on mental health at work, written in consultation with the ILO, state that employers have a responsibility to ensure that psychosocial risks, which can contribute to burnout, are managed within the workplace to protect employee’s mental health []. Psychosocial risks are defined as “anything in the design or management of work that increases the risk of work-related stress” [] (psychosocial risks section). This may include a lack of work variety, lack of job control or inflexible hours, poor communication, lack of support, and poor work-life balance []. A shared responsibility exists between the workplace and the employee to manage and protect the mental health and wellbeing of individuals through preventing burnout.

Burnout contributors can be divided into risk and protective factors, with protective factors describing aspects of the workplace that can help to reduce an individual’s risk of experiencing burnout. Protective factors in VN/Ts have been found to include manageable workloads, teamwork and support, clear and respectful communication, appropriate staffing levels, recognition of work, and knowledge of making a difference to clients and patients []. Risk factors describe aspects of the workplace that increase an individual’s risk of experiencing burnout. These factors may be experienced across a range of industries, for example, co-worker incivility [], or may be unique to individuals working in animal care roles, for example, exposure to animal abuse and euthanasia []. In VN/Ts, risk factors have been found to include high workloads, lack of skill utilisation, negative team culture, unclear communication, poor management or leadership, lack of schedule control, poor remuneration, lack of progression opportunities, negative client interactions, and lack of appreciation [,]. Some of these contributors, including high job demands, low job control, lack of support, and team conflict in VN/Ts, were identified in studies published over 10 years ago and, therefore, awareness of these problems is not new [,]. Despite this, recent research suggests that they are still being inadequately managed [,]. In addition to understanding the contributors to burnout it is, therefore, necessary to identify any barriers and enablers that may prevent, or support, organisations in addressing these contributors, so as to maximise the chances of success.

Barriers are factors that impede the ability of people leaders to address burnout risk factors. These are multifactorial and may be internal to the workplace. This includes barriers related to the interventions themselves, for example, technology that is not suited for the intended use; barriers related to the process of implementation, for example a lack of planning; or barriers related to the characteristics of the team or workplace, for example opposing values within the team. Barriers may also be external to the workplace, related to industry or legislative limitations, for example a lack of standardised educational competencies for professional licensing requirements []. Enablers are factors that facilitate people leaders to manage burnout. These may also arise from internal workplace sources, for example clear goals that have been collaboratively developed; or external sources, for example existing research to help understand the impact of changes [].

Burnout prevention strategies can be classified as primary and secondary interventions, which may be organisational or individual focused, and tertiary interventions, which are generally individual focused []. Primary interventions are aimed at addressing the antecedents of burnout and preventing the onset of signs. Secondary interventions focus on identifying signs of burnout in the early stages and preventing the development of longer-term impacts. Tertiary interventions are aimed at addressing existing burnout and minimising the long-term effects through healing and rehabilitation []. Implementation of primary and secondary interventions by the organisation requires an understanding of the unique contributors to burnout in VN/Ts.

Existing research exploring burnout in VN/Ts includes recommendations on strategies that can be implemented within the workplace to better support individuals. These include providing opportunities for professional development, greater control over shift pattern and length, and management training on development of positive interpersonal relationships [,,]. No studies to date, however, have explored barriers to implementation. Furthermore, existing studies typically include researcher recommendations to address burnout [,,,]. While these recommendations are informed by research findings derived from VN/Ts, they have not been evaluated for their perceived effectiveness or feasibility. Gaining this information, particularly from experienced wellbeing and leadership experts in the veterinary industry, is critical to ensure best practice recommendations target the known risk and protective factors and are also evaluated as effective and feasible.

Delphi studies are a research method commonly used in the development of human healthcare recommendations, allowing researchers to gain consensus through expert opinion []. The Delphi technique has been used in studies to develop workplace guidelines for the prevention of mental health problems [], as well as to rate the importance of factors in the occurrence of burnout in nurses [], and is therefore well-suited to research in the area of VN/T burnout. The Delphi method is used to collect objective opinions from participants in geographically diverse locations, across successive iterative rounds, to develop recommendations based on collective expert views. Delphi studies are particularly useful in areas where limited research exists and consensus is absent, and the technique transforms expert opinions into group consensus to elevate the quality of research evidence []. The lack of existing research on barriers, enablers, and feasibility of management strategies to address burnout in VN/Ts makes this an ideal framework for developing recommendations in this area.

The aim of this study was to employ a Delphi method to develop effective and feasible organisational management strategies to address known contributors to burnout in VN/Ts. This addressed the existing literature gap by producing recommendations based on expert consensus. This was achieved by, first, identifying perceived barriers and enablers to addressing the contributors, then, second, by exploring perceived ease of implementation and effectiveness of proposed strategies in addressing burnout in the workplace.

2. Materials and Methods

The Delphi method [] was used to conduct the study, and it is reported following the Delphi studies in social and health sciences—recommendations for an interdisciplinary standardized reporting (DELPHISTAR) guideline [].

2.1. Research Design

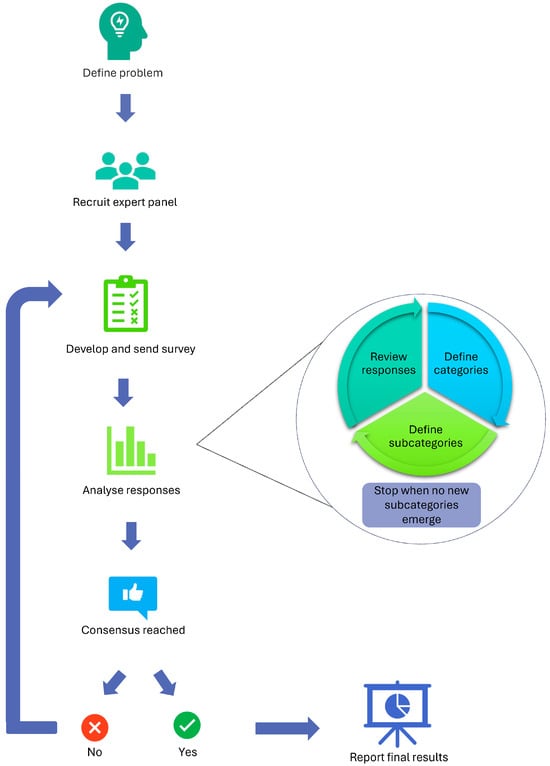

The Delphi method is a structured consultation process whereby a panel of experts contribute their views on an issue via an anonymous survey. Surveys incorporate both quantitative and qualitative questions to allow experts to rate items and provide feedback on their reasoning []. Panel members then revise their views through multiple survey rounds based on summarised feedback and responses from other participants, until consensus is reached. Anonymity is maintained throughout the process to minimise risk of bias resulting from perceptions of dominance and group conformity []. The current study comprised two rounds of data collection, with additional planned rounds being cancelled due to consensus being reached. In this study, consensus was defined as at least 75% endorsement by the panel across two consecutive ratings, following guidelines from similar research [,]. This process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Delphi technique flow chart.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

Purposive sampling was utilised to identify experts with a minimum of five years’ experience in VN/T leadership, leadership consulting, or wellbeing, as utilised in similar studies [,]. Potential participants were identified through their involvement in, or contributions to, VN/T wellness publications, conference presentations, veterinary industry wellbeing initiatives and awards, VN/T wellbeing podcasts, LinkedIn profiles, and existing professional networks of the researchers. Potential participants were contacted via email or LinkedIn and invited to contribute to the study. The panel size in Delphi studies is recommended to be greater than 20, after taking into account attrition across survey rounds []. Out of 84 experts invited, 40 consented to participate in the initial round. Participant recruitment was not directed toward specific countries, however, all recruited participants belonged to nations considered as the global West and English speaking. Participants who completed each round were invited to participate in subsequent rounds.

2.3. Measures

The aim of Round 1 was to explore barriers, enablers, and proposed strategies to address risk and protective factors for burnout in VN/Ts. The survey comprised a mixture of four questions which were developed by the authors. Participants were asked to respond to the same four questions for each of 10 risk and three protective factors derived from the findings of Chapman et al. [,]. For the 10 risk factors, Question 1 asked participants to rate how easy, or difficult, they believe it is to address the issue. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘very difficult’ to ‘very easy’. Three open-ended questions then asked participants to identify (1) what, if any, barriers they are aware of that increase the difficulty for managers or leaders to address the issue, (2) what, if any, enablers they are aware of that support managers or leaders to address the issue, and (3) what solutions or strategies they are aware of that effectively address the issue. For the three protective factors, the same questions were asked but rephrased to reflect the protective aspect. For example, the words “to address this issue” were replaced with “to promote this factor”. The final open-ended question in the protective factors section removed the word “solutions” and sought strategies to promote the protective factor only, as solutions for protective factors are not required (Supplementary Materials S1). Responses to the questions in Round 1 were analysed and informed the development of solutions to the 10 risk factors, and promotions strategies for the three protective factors, which were then reviewed in the second round of data collection.

The aim of Round 2 was to rate the ease with which each solution or promotion strategy, developed in Round 1, could be implemented, as well as to rate the perceived effectiveness of the solutions in addressing the 10 risk factors. The survey comprised a mixture of three questions developed by the authors. Participants were asked to respond to the same three questions for each of the 10 risk factors, and two of those three questions for the three protective factors. Rating questions asked participants to rate how easy, or difficult, they believed it would be to implement each solution, for the risk factors, and each strategy, for the protective factors, as well as how effective, or ineffective, they believed the solutions for each risk factor would be. Items were measured on 5-point Likert scales ranging from ‘very difficult’ to ‘very easy’ for ease of implementation, and from ‘very ineffective’ to ’very effective’ for effectiveness of solutions. Open-ended questions asked participants to provide feedback on proposed improvements to both solutions and strategies (Supplementary Materials S2).

2.4. Procedure

The study was conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, and ethical approval was obtained from the Human Ethics Low Risk Committee at La Trobe University, Australia (approval number HEC24265). Data for Rounds 1 and 2 were collected between 7 October 2024 and 13 January 2025.

A link to each Round of the survey was emailed to participants and responses were collected using QuestionPro version 2 (Austin, TX, USA) []. Prior to receiving the first survey link, participants were required to sign a participation consent form which included advice to contact their local healthcare provider if they experienced any lasting negative emotions after taking part in the study. Links to international helplines were also provided. Each survey was initially open for two weeks, with a short time for data analysis scheduled between rounds to maintain participant engagement and reduce attrition. Closure of both survey rounds was extended by 10 days (Round 1) and one month (Round 2) in order to allow for increased participation, and account for the busy December holiday period (Round 2). Email reminders were sent to participants that had not yet completed the survey two days before the initial survey closure date, and then again after the initial closure date to inform remaining participants of the extended deadline.

A summary of responses was circulated to participants following data analysis of each round to allow participants to compare their responses with those of the collective panel. The Round 1 summary document outlined the key barriers and enablers that had been identified from participant responses, as well as the mean ease-of-management rating for each risk and protective factor. After Round 2, the summary document provided an overview of the ease and effectiveness ratings for solutions proposed in Round 1, as well as highlighting notable findings from the data.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data from open ended questions in Round 1 were analysed using NVivo version 15 (Denver, CO, USA) [] and coded using conventional content analysis [] to identify and describe the emerging categories. This approach is recommended when existing research on the area is limited, as it identifies patterns and recurrent viewpoints among participant responses to open-ended questions, without exposing participants to preconceived theories or ideas []. An iterative approach was taken where one author (AC) read the responses in full and then reviewed them multiple times to identify and refine categories and sub-categories until no novel phenomena emerged. In contrast to thematic analysis which relies on interpretive analytical approach by the researcher to contextualise the data, content analysis takes a descriptive analytical approach, coding and categorising data to identify trends and patterns of words []. Risk of bias resulting from the epistemological perspectives of the researcher is, therefore, much lower. Debriefs were conducted between the primary author and the last author (VR) to ensure that context and clarity of the data were accurately represented in the coding, and to further reduce the risk of bias.

Data from open ended questions in Round 2 were analysed using directed content analysis [] to validate and extend the existing findings from Round 1. Directed content analysis utilises existing themes, which were developed in Round 1, to provide a framework with which to design and analyse questions based on the existing categories []. The same iterative process was followed to categorise data into the existing codes developed in Round 1, with debriefs to increase validity of the process [].

Quantitative data from Rounds 1 and 2 were analysed using descriptive statistics, with means and standard deviations reported for each item. Missing data were managed by calculating the central tendency based on the number of participant responses to each item and excluding missing responses. Percentages and frequency counts for each Likert scale rating were also calculated and used to determine whether consensus had been reached.

3. Results

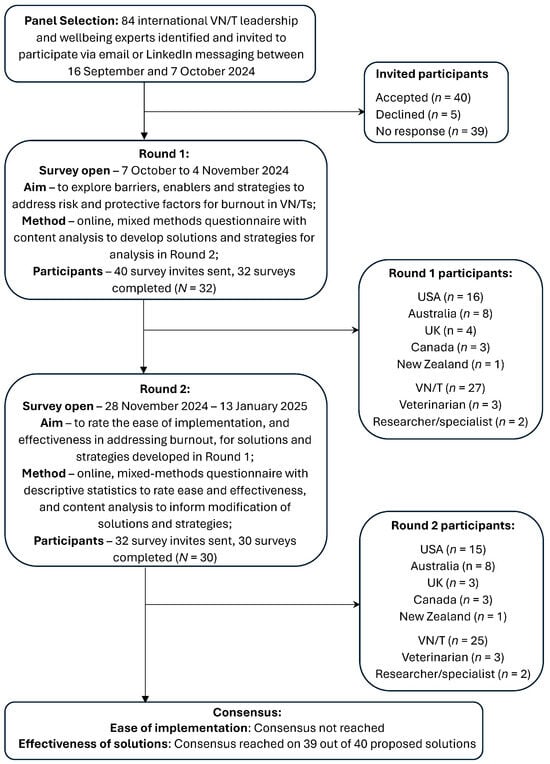

3.1. Participants

Forty experts were recruited from the United States of America (USA) (n = 18), Australia (n = 9), United Kingdom (UK) (n = 7), Canada (n = 4), and New Zealand (n = 2). The majority of participants were VN/Ts (n = 33), with the remainder either veterinarians (n = 3), or veterinary wellbeing experts without a veterinary clinical qualification (n = 3). A total of 32 and 30 participants completed the survey in Rounds 1 and 2 respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of Delphi study process and participants including country of residence and professional background.

3.2. Round 1

Round 1 explored barriers, enablers, and strategies to address risk and protective factors for burnout in VN/Ts. Results for Round 1, summarising the themes identified among barriers and enablers to address risk and protective factors, as well as the mean rating for how easy or difficult participants thought that the risk or protective factor is to manage, can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Barriers and enablers to addressing risk and protective factors associated with burnout in VN/Ts derived from Round 1.

Perceived ease of management ratings for all risk and protective factors ranged from 2.38 (±1.01) to 3.74 (±1.03) on a scale of 1 (very difficult) to 5 (very easy). Consensus around ease of management was achieved in only three out of 13 items, with scores for the remaining items spread across at least four out of five ratings. The factor that was rated the most difficult to address in Round 1 was Problem 5 ‘Poor management and leadership of the team’. One participant suggested that “It is very difficult to address poor management or leadership because that would involve leadership admitting that those things are a problem”. In contrast, Protective factor 2 ‘Knowledge of having a positive impact on a patient or client’ was rated the easiest protective factor to leverage, with numerous client and feedback systems being proposed that one participant described as “Pretty easy and low cost!”.

Analysis of the qualitative data exploring barriers and enablers identified two key overarching themes. First, there is a lack of training and support for leaders as well as few positive role models in this area. One participant noted that this is an ongoing cycle, where “Leaders in the vet profession don’t routinely get exposed to good leadership so learn poor behaviours, then are promoted into the role with no support”. In addition, there is a lack of, or variability in, VN/T regulation across all countries represented in the study, which may impact the capacity to effect positive change in several risk areas. One participant highlighted the extent of the impact, noting that “Out of date/touch regulations and rules with regard to VN/T capabilities that would value add to the business, animal welfare, workload for vets, and job satisfaction for VN/Ts”. Other frequently cited barriers included workforce shortages, existing levels of burnout in the team or management, hierarchical organisational structures and a lack of workplace resources such as time or money. Enablers included access to technology to support efficiency, professional networks, open and transparent communication, and breadth of skills within the team.

Consistent themes were also identified across the proposed solutions. These focused primarily on addressing leadership issues by improving recruitment procedures for leadership roles, providing ongoing leadership training and support, and utilising management consultants where necessary to address gaps in business expertise. In addition, a number of strategies were proposed to support suggested solutions but were beyond the scope of individual clinics to implement. These included public education campaigns to increase awareness of industry challenges such as workload; the promotion of better understanding and acknowledgment of VN/Ts in professional liability insurance policies; and advocacy initiatives to lobby government and industry bodies for better pay standards, mandatory registration, and title protection.

Specific solutions and strategies to address each risk and protective factor were developed based on common themes that emerged from participant responses. A range of broad solutions were identified for each risk factor, with more specific actions proposed to help achieve this solution. For example, to increase opportunities for skills and knowledge utilisation, one proposed solution was ‘Implement systems to support delegation’. Suggested actions included: implementing VN/T-to-patient and veterinarian ratios, developing mentoring programs, developing clear standard operating procedures (SOPs) for performing clinical tasks, employing support staff to complete non-clinical tasks, and implementing team rounds to support collaboration. Common themes found across all solutions included improving communication, training and support, and workflow systems.

3.3. Round 2

Round 2 asked participants to rate the solutions and strategies, developed in Round 1, for ease of implementation (solutions and strategies) and effectiveness in addressing burnout (solutions). Results for Round 2, summarising the proposed solutions developed from the Round 1 responses, as well as the mean and consensus ratings for how easy each solution and strategy would be to implement, and how effective each solution would be in addressing burnout, can be seen in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Mean perceived ease of implementation ratings and participant consensus ratings for solutions and strategies to workplace burnout risk and protective factors derived from Round 2.

Table 3.

Mean perceived effectiveness ratings and participant consensus ratings for solutions to workplace burnout risk factors derived from Round 2.

A broad lack of consensus was found regarding the perceived ease of implementation with scores for 50 out of 51 (98%) of the proposed solutions and strategies spread across at least four different ratings on a Likert scale of one (very easy) to five (very difficult). This lack of consensus could be explained by general qualitative data across all risk and protective factors, which suggested that ease of implementation was expected to vary depending on a range of contextual factors in the affected clinic. Existing workplace climate, including team culture, leadership quality, staff willingness for change, attitudes and behaviours of existing staff, and the ability to effectively design and implement change processes, were identified by participants as aspects that impact the complexity of effecting workplace change. Based on these findings, achieving consensus on ease of implementation was determined to be unlikely due to there being too many variables to determine one, or any, best practice recommendations. Advancement of these questions to further rounds was discontinued.

In contrast to ease of implementation, consensus around effectiveness was reached in 39 out of 40 (97.5%) proposed solutions. The majority of solutions (87.5%) were rated as effective/very effective, with three (7.5%) rated as effective/neutral, one (2.5%) rated as ineffective/neutral, and one (2.5%) where consensus was not reached. Qualitative data highlighted three key challenges and considerations that applied broadly across the risk factors and proposed solutions. First, implementation time and strategy must be considered when initiating any change process to set realistic expectations. Solutions that rely on culture change, for example, require long term commitment, with one participant estimating that “It takes time to engage the team and shift the culture (1–2 years)”, and another noting that change management processes must be carefully considered “It needs to be done with the people not to the people and it needs to be authentic not just words”. In addition, historical cultural attitudes embedded in the industry also need to shift in order to reduce barriers to change as illustrated by the following response: “The most difficult part […] is getting past the ‘but I have always done it this way’ mentality”. One participant suggested that embedding leadership skills in professional training programs could be of benefit “The changing of workplace wellbeing, culture and leadership could be quite easy if these issues were addressed within [Doctor of Veterinary Medicine] DVM school trainings as well as technician and assistant schools”. Finally, in some geographical regions, progress on issues including utilisation, progression opportunities, and remuneration, was reported as being hindered by lack of regulation or title protection, with one participant suggesting that “Registration and accreditation of [VN/Ts] with delineation of duties based on experience and education will assist professional growth and recognition […] and be covered under registration/insurance just as vets are”. Another participant noted that the lack of, or unclear, regulation impedes veterinarian’s willingness to delegate tasks that VN/Ts are trained to perform “[Vets] prefer to do things themselves because they know where accountability will land”.

Out of all risk factors analysed, high workload had the most effective solution: ‘Improving staff retention’, which was rated as considerably more effective than: ‘Hiring more staff’. One participant noted that “Hiring more staff will always be a problem: 1. As we have a decline in the numbers of both DVMs and VN/Ts interested in serving this field, 2. Until we positively impact culture (which drives retention) and workload management systems”. Another stated that “Hiring more staff is most likely not cost effective for many clinics, improving workflow and retention of staff is better”. High workload also had the least effective solution: ‘Preventative healthcare focus to reduce the number of cases seen’. Participants suggested that this was beyond the capacity of an individual clinic to manage, with one noting that “The public health promotion to clients and consumers would require a HUGE effort from all sectors of the profession and would be extremely challenging for a clinic to do on their own to change client and consumer behaviours”.

The most highly rated effective solutions overall addressed poor management and leadership of the team, which had been rated the hardest risk factor to address in Round 2. Participants noted that leaders in the veterinary industry are often not selected for leadership qualities, therefore, early support is needed “In the veterinary industry (VN/T and vet) the leaders are often those that own the practice or ‘fall into’ the position with length of service or when staff leave. Better or greater focus on leadership and management skills in undergraduate programs would help”, as well as ongoing peer support “Leadership peer groups that provide coaching are a much-needed solution”.

Dealing with clients showing rude and abusive behaviours had the only solution where consensus was not reached: ‘Communicate clear behavioural expectations to clients’. Conflicting opinions around this focused on how the solution is implemented, with support for providing clear expectations for both clients and veterinary staff. One participant noted that “Expectations from clients alone without what they receive in return may be damaging on first impressions”, and another confirming “You can post signs for clients about poor behaviour—what do they care? They can just go someplace else”. A third participant suggested that “When a client begins at a practice, [they] should be signing some sort of agreement of what the practice will provide for them and the required client behaviours”.

Analysis of data from open-ended questions in Round 2 was used to revise the proposed solutions and suggested actions derived from Round 1. This included changes to language to promote inclusive practice. For example, for Problem 3, exploring solutions to a negative team culture, the proposed action: ‘support calling out unacceptable behaviour’ was changed to ‘support calling in of unacceptable behaviour’. It also included changes to promote a growth mindset, acknowledging that individuals have the capacity to change. For example, in Problem 9, exploring solutions to client incivility, ‘Having to deal with rude or abusive clients’ was changed to ‘Dealing with clients expressing rude or abusive behaviours’. In addition, a solution rated as ineffective/neutral was removed, and proposed timelines to guide implementation of solutions were added based on feedback around setting realistic expectations for implementation. The final recommendations can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proposed solutions and associated actions to address ten workplace burnout risk factors in VN/Ts, ranked in order of effectiveness as rated by Delphi panel members.

Proposed strategies and suggested actions to leverage burnout protective factors were also updated based on analysis of Round 2 data and can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

Proposed strategies and associated actions to promote three burnout protective factors in VN/Ts.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop effective and feasible organisational management strategies to address burnout in VN/Ts. This was achieved by utilising the Delphi method to first identify the barriers and enablers to effecting change and then explore the perceived ease and effectiveness of proposed strategies, to develop recommendations.

4.1. Industry-Wide Barriers

The findings revealed that the same barriers exist across all countries involved in this study. Some barriers, such as inadequate regulation and lack of leadership education in veterinary and VN/T training programs, are beyond the capacity of individual clinics to effect change and require industry-wide or government interventions. The lack of, or uncertainty around, regulation of VN/Ts was a key barrier to addressing multiple burnout risk factors. Whilst current regulatory requirements vary between, and within, countries, participants from all represented countries (USA, UK, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) reported the impact of inadequate regulation on VN/T utilisation. Local associations not permitting VN/Ts to perform skills they are trained and qualified in, as well as poor veterinarian education on VN/T regulations, have been found to contribute to poor utilisation [,]. Guidelines for optimal utilisation of VN/Ts, published by the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) [], outline the positive impact on the whole veterinary team, including improved patient care, staff retention, and financial sustainability of the business, and provide multiple resources to support improved utilisation. Further research, however, is required to measure the impact of these guidelines in the future.

Inadequate support for leaders was also found to be a barrier to addressing numerous burnout risk factors. Previous studies have highlighted the important role that leadership plays in managing veterinary team burnout through actions such as support, advocacy, recognition, and empowerment of staff [,]. These findings were replicated in the current study, but it was also revealed that many veterinary team leaders lack the necessary training or time to succeed in the role. Promotion of individuals to leadership roles based on clinical expertise, or length of service, was reported as an embedded cultural problem within the industry, resulting in a lack of positive role models or mentors to drive change. Provision of training or support to leaders was proposed as a solution strategy for over half of the risk factors that were reviewed, which illustrates the extent of the issue. Improved recruitment processes for leadership positions, as well as better support and training for those interested in taking on a leadership role, are vital to reducing burnout in VN/Ts as well as VN/T leaders. Furthermore, non-leadership career progression pathways, other than leaving the industry, must be offered to increase options for advanced VN/Ts in order to prevent people advancing to management roles as the only career progression option.

4.2. Clinic Specific Barriers

Unique barriers within individual clinics focused on the existing workplace climate and therefore, will vary between clinics. Quality of leadership, existing team culture, staff willingness for change, existing level of staff burnout, financial health of the clinic, and the ability to effectively design and implement change processes, are all issues that must be objectively evaluated before determining suitable strategies for implementation.

Addressing poor leadership (Risk factor 5) was found to be a particular challenge as it requires leaders to accept that they are part of the problem. Whilst this poses a critical barrier to effecting positive change for VN/T teams, qualitative data from this study also acknowledged the risk of burnout in leaders. Research suggests that negative leader well-being is associated with negative employee well-being []. However much of the literature focuses on the effects of leadership on employee burnout, with limited research exploring burnout in leaders, despite reports of high levels of stress and demands in their role [,]. In addition to providing support to improve leadership skills, it is essential that well-being support is also provided to leaders in order to enable them to perform to the best of their ability. Similarly, implementing significant organisational change has been found to contribute to burnout in teams []. Whilst pre-existing burnout in the team does not prevent the introduction of new systems, required levels of support, such as time and resources, should be re-evaluated in order to maximise adaptive reserve and resilience within the team and avoid increased burnout and turnover [].

Reluctance of staff to engage in a change process due to attitudes such as “we’ve always done it this way”, was identified as a barrier in the current study and has also been reported elsewhere [,]. Resistance to organisational change has been reported as one of the key reasons why change initiatives fail []. Reasons for resistance include perceived loss of control and lack of fairness [,], which comprise two of the six key Areas of Worklife found to contribute to burnout []. When encountering resistance to change, it is, therefore, essential to understand the underlying reasons for resistance, in order to address these directly [].

Clinic-specific barriers that are within the capability of individual leaders to address will vary widely between clinics. Consideration must, therefore, be given to the existing workplace climate before selecting which strategies to implement, and indeed, how to implement them, in order to maximise chances of success.

4.3. Solutions

4.3.1. Risk Factors

Common themes among the proposed solutions included improving communication, developing a culture of psychological safety, developing progression pathways for VN/Ts with embedded training and support, developing clear policies in collaboration with the team, and reviewing workplace systems to enhance efficiency. Many of the solutions, such as improving workplace culture, will be a long process requiring time, commitment, and resources to ensure that changes are successful and become embedded in the ongoing normality of the clinic []. Kotter’s [] change management process suggests that short term wins can help to build morale and momentum to help sustain motivation within larger change efforts. It may be possible, and even beneficial, therefore, to implement a combination of short- and long-term strategies simultaneously to help generate positive change in the short term.

Of the ten workplace risk factors evaluated in the study, high workload and lack of support have been found to be significant contributors to burnout in VN/Ts []. In the current study, improving staff retention was considered a more effective strategy for reducing workload (Risk factor 1) than hiring more staff. Reasons for VN/T turnover have been found to include poor financial outlook, lack of career progression opportunities, lack of utilisation, poor workplace culture, and lack of employer support [,], all of which have also been found to be risk factors for burnout in VN/Ts []. Factors predicting retention in veterinary nurses have been described as multi-factorial and individual []. The introduction of ‘stay interviews’ was one of the proposed actions to achieve this solution in the current study. These short, proactive discussions between leader and individual team member are conducted at regular intervals and establish what works well in their current role and what can be improved and have been shown to have positive results in human nursing teams [,].

Improving workplace culture (Risk factor 3) was identified as particularly challenging to address due to the time it takes to establish culture change within an organisation. Research suggests that culture impacts employee engagement, morale, and cooperation, all of which play a key role in the implementation of successful change initiatives []. Proposed solutions focused on breaking down barriers within the team through actions such as developing team vision and values collaboratively, establishing support from the leadership team, and promoting regular and transparent communication. Establishing a need for change and developing a shared vision are proposed to be two key stages of successful change management []. Research suggests that acknowledging current problems within the team, developing a clear vision, and combined leadership and employee support are all required for culture change to be successful []. Whilst these have all been identified as separate actions within the recommendations, it is, therefore, important to ensure that they are implemented collectively in order to maximise the change of success.

4.3.2. Protective Factors

Factors that protect against burnout in VN/Ts include having control over one’s work, knowledge of having a positive impact, and being included in patient care decision making []. As with risk factors, the ability to leverage each of these will vary between clinics, therefore strategies should be carefully considered before implementation. The perceived effectiveness of these strategies was not measured, as protective factors are aimed at preventing the onset of burnout, rather than reducing existing burnout []. However, a notable overlap of themes can be seen between proposed primary prevention strategies (protective factor strategies) and secondary prevention strategies (solutions to risk factors). Teamwork, collaboration, improved communication, support, and development opportunities, can be seen across recommendations for both primary and secondary burnout prevention. As such, it may be beneficial for clinic leaders to consider all recommendations—regardless of which burnout risk factors have been identified in their clinic—in order to take a proactive approach to burnout management within their teams.

4.4. Implementation of Solutions

Change management is challenging, and organisational change initiatives have been reported to fail in 70% of cases, and in up to 90% of cases addressing culture change []. Change is, however, essential for improvement and ultimately, the survival of any organisation []. The findings from this study showed that a positive and psychologically safe workplace culture is fundamental to the success of a large number of the proposed solutions. Previous research shows that a solid understanding of the operational process of change, as well as establishing upper management support and awareness of the existing issues, are critical to driving successful change []. Instruments to measure organisational culture and health may be of use in conducting impartial evaluations and have been designed for use in human healthcare [,]. These surveys conduct a full 360-degree evaluation of areas such as leadership and management effectiveness, staff wellbeing, and patient safety, and provide a valuable reference for developing veterinary focused assessment tools. Use of evaluation tools such as these can help to increase leadership awareness of areas where their perceptions of the organisational climate do not align with those of their teams. This understanding will support leaders to select targeted strategies which are more likely to be successful in addressing existing workplace issues.

In addition to assessing workplace climate, the time and effort involved with strategy implementation must be considered and clearly communicated to the team in order to set realistic expectations for both staff and leaders. Employee attitudes towards change have been found to be a key determinant of its long-term success, therefore any change process—regardless of the intended benefits for staff—must be carefully managed []. One of the key barriers to addressing burnout in this study was found to be the lack of leadership or management expertise within the industry. In veterinary clinics where knowledge of workplace program design and implementation is lacking, external support such as the use of business management consultants with an in-depth understanding of the veterinary industry should, therefore, be considered to increase the chances of success.

The dissemination of these and future findings is critical to effecting change. Whilst it is beyond the scope of this study, which focused on implementation of change within the workplace, industry wide change is essential to achieving meaningful progress. Including leadership education in veterinary and VN/T training, improving VN/T regulation, and increasing awareness of burnout reduction strategies across the industry can all make a significant contribution to reducing burnout. In addition, tackling misinformation around topics such as VN/T utilisation, and individuals’ weaknesses leading to burnout, is imperative and may benefit from platforms such as social media to discredit broad misconceptions [].

Finally, it should be noted that whilst burnout is the result of workplace stressors and, thus, the workplace has a responsibility to address them where possible, not all burnout contributors can be completely controlled or eliminated []. There is, therefore, a shared responsibility for VN/Ts to implement individual coping strategies to strengthen the effects of workplace efforts. Whilst these may be implemented by the individual, however, many, for example work-life balance, counselling, and education, may also require, or benefit from, workplace support [].

4.5. Limitations and Further Research

This study had some limitations worth noting. First, a high level of consensus around effectiveness of solutions was achieved in Round 2 with only minor proposed modifications which did not justify additional rounds. As a consequence, there was no opportunity to measure stability of the results over successive rounds. There is significant variance among the accepted closing criteria for Delphi studies. Some authors argue that stability must be measured in conjunction with consensus in order to confirm the validity of results []. Others argue that either consensus alone, or a pre-determined number of rounds, is a more commonly used criterion for terminating a Delphi study []. As such, additional rounds would have enabled the measurement of stability in addition to consensus, but at the risk of extending the study and further imposing on the goodwill of participants. Further Delphi studies would be beneficial to confirm the reliability and proposed effectiveness of these recommendations. Second, whilst all efforts were made to recruit panel members from a range of representative countries, almost 50% of the panel comprised members from one country (USA), whilst the other 50% represented members from the remaining four countries (UK, Australia, Canada, New Zealand). It is, therefore, possible that some proposed solutions may be more applicable to the culture and legislative climate of the USA. In addition, all panel members were recruited from developed countries and therefore data from developing countries was not captured. The findings, therefore, may not translate to the different challenges that may be experienced by VN/T leaders in developing countries and further research would be beneficial to explore the generalisability of these recommendations. Finally, gaining expert opinion fills a gap in existing knowledge on effective organisational strategies to address burnout in VN/Ts. However, further research is required to evaluate and measure the effectiveness of proposed interventions in order to know if the recommendations are actually effective in preventing burnout.

5. Conclusions

Burnout in VN/Ts has negative impacts on the individual, patient, and business, but existing research lacks clear recommendations on workplace strategies to support better management of burnout at the source. This study developed 39 expert-led workplace burnout reduction strategies and recommended actions to guide VN/T managers worldwide in addressing 10 known risk factors for burnout in VN/Ts. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first research to explore expert recommendations to address burnout in veterinary or animal care professionals. Whilst some of the recommendations are uniquely relevant to VN/Ts, many apply across broader animal care professional roles and may therefore help to guide leaders in addressing burnout more widely.

Proposed strategies to address burnout, and associated recommended actions, are specific to each risk factor, but many had similar overarching themes. These included providing support and education to leaders, improving communication, fostering a culture of psychological safety, developing clear guidelines and protocols in collaboration with the team, providing clear progression pathways, and supporting delegation of tasks to VN/Ts, as well as redistributing tasks for which they are overqualified. Successful implementation of strategies relies on first, identifying the presence of workplace risk factors through assessment of burnout among staff, and then, evaluating the existing organisational climate, in order to select the most appropriate strategies. A good understanding of change processes will also help to maximise success. In addition, the study identified the need for broader change initiatives, including development of clearer regulation of VN/Ts, and inclusion of leadership education within veterinary and VN/T training programs, to better support veterinary clinics in achieving positive change within the industry. These findings provide practical guidelines to help veterinary clinics reduce the risk of burnout in VN/Ts, as well as insights for consideration by the broader veterinary industry to support professional growth and a more sustainable future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15091257/s1, Supplementary Materials S1: Delphi study Survey—Round 1; Supplementary Materials S2: Delphi study Survey—Round 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.C., V.I.R. and P.C.B.; methodology, A.J.C., V.I.R. and P.C.B.; formal analysis, A.J.C.; investigation, A.J.C.; data curation, A.J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.C.; writing—review and editing, A.J.C., V.I.R. and P.C.B.; supervision, V.I.R. and P.C.B.; project administration, A.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research and approved by the Human Ethics Low Risk Committee of La Trobe University (approval number HEC24265; approved 10 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable to share due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all of the study participants for their support of this research and contribution of their expert knowledge. Study participants who gave consent for formal acknowledgement are listed below: Amber Foote, CertAVN (Teaching, Coaching and Mentoring) BSc (Hons) RVN C-SQP; Amy Newfield, MS, CVT, VTS (ECC); Erica Honey MBA/MHRM MEmergMgt GradCertPDev BSc (Hons) RVN; Francesca Brown MProfPrac BVSc BSc GradDip Sustainable Practice; Heather Prendergast, RVT, CVPM, SPHR; Jane Bindloss RVN (UK), DipMgt; Kathleen Dunbar, MSW, RSW, RVT, VTS (Clinical Practice-Canine/Feline); Lis Conarton, LMSW, LVT, VTS (Physical Rehabilitation); Liz Hughston, MEd., RVT, CVT, LVT, VTS (SAIM) Lifetime (ECC) Emeritus; Makenzie Peterson, DSW, MSc; Robyn Sutton, RVT, VTS(ECC); Shannon Molloy RVN.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAHA | American Animal Hospital Association |

| DVM | Doctor of Veterinary Medicine |

| ILO | International Labour Organisation |

| OHS | Occupational Health and Safety |

| SOPs | Standard Operating Procedures |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| VN/T | Veterinary nurse and technician |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Moore, I.C.; Coe, J.B.; Adams, C.L.; Conlon, P.D.; Sargeant, J.M. The role of veterinary team effectiveness in job satisfaction and burnout in companion animal veterinary clinics. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brscic, M.; Contiero, B.; Schianchi, A.; Marogna, C. Challenging suicide, burnout, and depression among veterinary practitioners and students: Text mining and topics modelling analysis of the scientific literature. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffey, M.A.; Griffon, D.J.; Risselada, M.; Scharf, V.F.; Buote, N.J.; Zamprogno, H.; Winter, A.L. Veterinarian burnout demographics and organizational impacts: A narrative review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1184526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.J.; Rohlf, V.I.; Moser, A.Y.; Bennett, P.C. Organizational Factors Affecting Burnout in Veterinary Nurses: A Systematic Review. Anthrozoös 2024, 37, 651–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Hahn, J.; Andrews, J.; Probyn-Smith, K.; Jones, R. Merck Animal Health Veterinary Team study reveals factors associated with well-being, burnout, and mental health among nonveterinarian practice team members. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Hall, L.H.; Berzins, K.; Baker, J.; Melling, K.; Thompson, C. Mental healthcare staff well-being and burnout: A narrative review of trends, causes, implications, and recommendations for future interventions. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.A.; Gee, P.M.; Butler, R.J. Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nurs. Outlook 2021, 69, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; Andrade, S.M.d. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. International Classification of Diseases; 11th Revision; ICD-11; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Mental Health at Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/topics/safety-and-health-work/mental-health-work (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Mental Health at Work; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-005305-2. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Psychosocial Risks and Stress at Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/psychosocial-risks-and-stress-work (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Chapman, A.J.; Rohlf, V.I.; Moser, A.Y.; Bennett, P.C. Understanding Veterinary Technician and Nurse Burnout. Part 2: Addressing Veterinary Technician Burnout Requires Tailored Organizational Wellbeing Initiatives. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, A.F. Workplace incivility: A literature review. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.; Polly, Y.; Louise, C.B.; O’Donoghue, K. Reducing the “cost of caring” in animal-care professionals: Social work contribution in a pilot education program to address burnout and compassion fatigue. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2021, 31, 828–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.J.; Rohlf, V.I.; Bennett, P.C. Understanding Veterinary Technician and Nurse Burnout. Part 1: Burnout Profiles Reveal High Workload and Lack of Support are Among Major Workplace Contributors to Burnout. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Black, A.F.; Winefield, H.R.; Chur-Hansen, A. Occupational stress in veterinary nurses: Roles of the work environment and own companion animal. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.M.; Maples, E.H. Occupational stress in veterinary support staff. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2014, 41, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Kontak, J.; Jeffers, E.; Lawson, B.; MacKenzie, A.; Burge, F.; Boulos, L.; Lackie, K.; Marshall, E.G.; Mireault, A.; et al. Barriers and enablers to implementing interprofessional primary care teams: A narrative review of the literature using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, C.; Hansez, I. Temporal Stages of Burnout: How to Design Prevention? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2024, 21, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, G.M.; LaLonde-Paul, D.F.; Perret, J.L.; Steele, A.; McConkey, M.; Lane, W.G.; Kopp, R.J.; Stone, H.K.; Miller, M.; Jones-Bitton, A. Investigation of burnout syndrome and job-related risk factors in veterinary technicians in specialty teaching hospitals: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2020, 30, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, L.R.; Wallace, J.E.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R.; Hellyer, P.W.; Richards, M. Veterinary technicians and occupational burnout. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holowaychuk, M.K.; Lamb, K.E. Burnout symptoms and workplace satisfaction among veterinary emergency care providers. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2023, 33, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.; Correia, I. Empathy and Burnout in Veterinarians and Veterinary Nurses: Identifying Burnout Protectors. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, S.; Reese, C.; Wendler, M.C. Methodology Update: Delphi Studies. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reavley, N.J.; Ross, A.; Martin, A.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Jorm, A.F. Development of guidelines for workplace prevention of mental health problems: A Delphi consensus study with Australian professionals and employees. Ment. Health Prev. 2014, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-García, G.; Ayala, J.C. Insufficiently studied factors related to burnout in nursing: Results from an e-Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederberger, M.; Schifano, J.; Deckert, S.; Hirt, J.; Homberg, A.; Köberich, S.; Kuhn, R.; Rommel, A.; Sonnberger, M.; DEWISS Network. Delphi studies in social and health sciences—Recommendations for an interdisciplinary standardized reporting (DELPHISTAR). Results of a Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.H.; Pilkington, P.D.; Ryan, S.M.; Kelly, C.M.; Jorm, A.F. Parenting strategies for reducing the risk of adolescent depression and anxiety disorders: A Delphi consensus study. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QuestionPro. QuestionPro API V2; QuestionPro: Austin, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. NVivo (Version 14); Lumivero: Denver, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F. Opportunities for New Zealand veterinary practice in the utilisation of allied veterinary professional and paraprofessional staff. Scope Health Wellbeing 2022, 7, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, A.R.; Celt, V.P.; Pilewki, L.E.; Hendricks, M.K. The newly credentialed veterinary technician: Perceptions, realities, and career challenges. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1437525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendergast, H.; Mages, A.; Rauscher, J.; Roth, C.; Thompson, M.; Thompson, S.T.; Yagi, K. 2023 AAHA Technician Utilization Guidelines; AAHA: Lakewood, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Skakon, J.; Karina, N.; Vilhelm, B.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work. Stress. 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, S.; Colbert, A.; Choi, D. Fired Up or Burned Out? How Developmental Challenge Differentially Impacts Leader Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Crown, S.N.; Ivany, M. Organisational change and employee burnout: The moderating effects of support and job control. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L.; Crabtree, B.F.; Nutting, P.A.; Stange, K.C.; Jaén, C.R. Primary Care Practice Development: A Relationship-Centered Approach. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010, 8, S68–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moore, I.C.; Coe, J.B.; Adams, C.L.; Conlon, P.D.; Sargeant, J.M. Exploring the Impact of Toxic Attitudes and a Toxic Environment on the Veterinary Healthcare Team. Front. Vet. Sci. 2015, 2, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Ansarian, M. Why do organisational change programmes fail? Int. J. Strateg. Change Manag. 2014, 5, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgalis, J.; Samaratunge, R.; Kimberley, N.; Lu, Y. Change process characteristics and resistance to organisational change: The role of employee perceptions of justice. Aust. J. Manag. 2015, 40, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Six areas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout. J. Health Hum. Serv. Adm. 1999, 21, 472–489. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.; Nguyen, H.; Groth, M.; Wang, K.; Ng, J.L. Time to change: A review of organisational culture change in health care organisations. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2016, 3, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Generating Short Term Wins. In Leading Change; Harvard Business Review Press: La Vergne, TN, USA, 2012; pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fults, M.K.; Yagi, K.; Kramer, J.; Maras, M. Development of Advanced Veterinary Nursing Degrees: Rising Interest Levels for Careers as Advanced Practice Registered Veterinary Nurses. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2021, 48, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, A.; Taylor, E. Veterinary nursing in the United Kingdom: Identifying the factors that influence retention within the profession. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 927499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, M.; Cannedy, S.; Oishi, K.; Canelo, I.; Hamilton, A.B.; Olmos-Ochoa, T.T. Using Stay Interviews as a Quality Improvement Tool for Healthcare Workforce Retention. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.; Whiteman, K.; DiCuccio, M.; Swanson-Biearman, B.; Stephens, K. Why They Stay and Why They Leave: Stay Interviews with Registered Nurses to Hear What Matters the Most. J. Nurs. Adm. 2023, 53, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Successful Change and the Force That Drives it. In Leading Change; Harvard Business Review Press: La Vergne, TN, USA, 2012; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, B. Introduction: Why Does Change Fail, and What Can We Do About It? J. Change Manag. 2011, 11, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idogawa, J.; Bizarrias, F.S.; Câmara, R. Critical success factors for change management in business process management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 2009–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, C.R.; Williams, S.P.; Brkic, M.; Purkayastha, S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Phillips, N.; Darzi, A. Measuring the organisational health of acute sector healthcare organisations: Development and validation of the Healthcare-OH survey. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Hamilton, S.; McSherry, R.; McIntosh, R. Measuring and Assessing Healthcare Organisational Culture in the England’s National Health Service: A Snapshot of Current Tools and Tool Use. Healthcare 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Mahmood, A.; Ibtasam, M.; Murtaza, S.A.; Iqbal, N.; Molnár, E. The Psychology of Resistance to Change: The Antidotal Effect of Organizational Justice, Support and Leader-Member Exchange. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 678952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.E.; Knesl, O. How can the veterinary profession tackle social media misinformation? J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holey, E.A.; Feeley, J.L.; Dixon, J.; Whittaker, V.J. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasa, P.; Jain, R.; Juneja, D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J. Methodol. 2021, 11, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).