Accessibility of Entrepreneurship Training Programs for Individuals with Disabilities: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

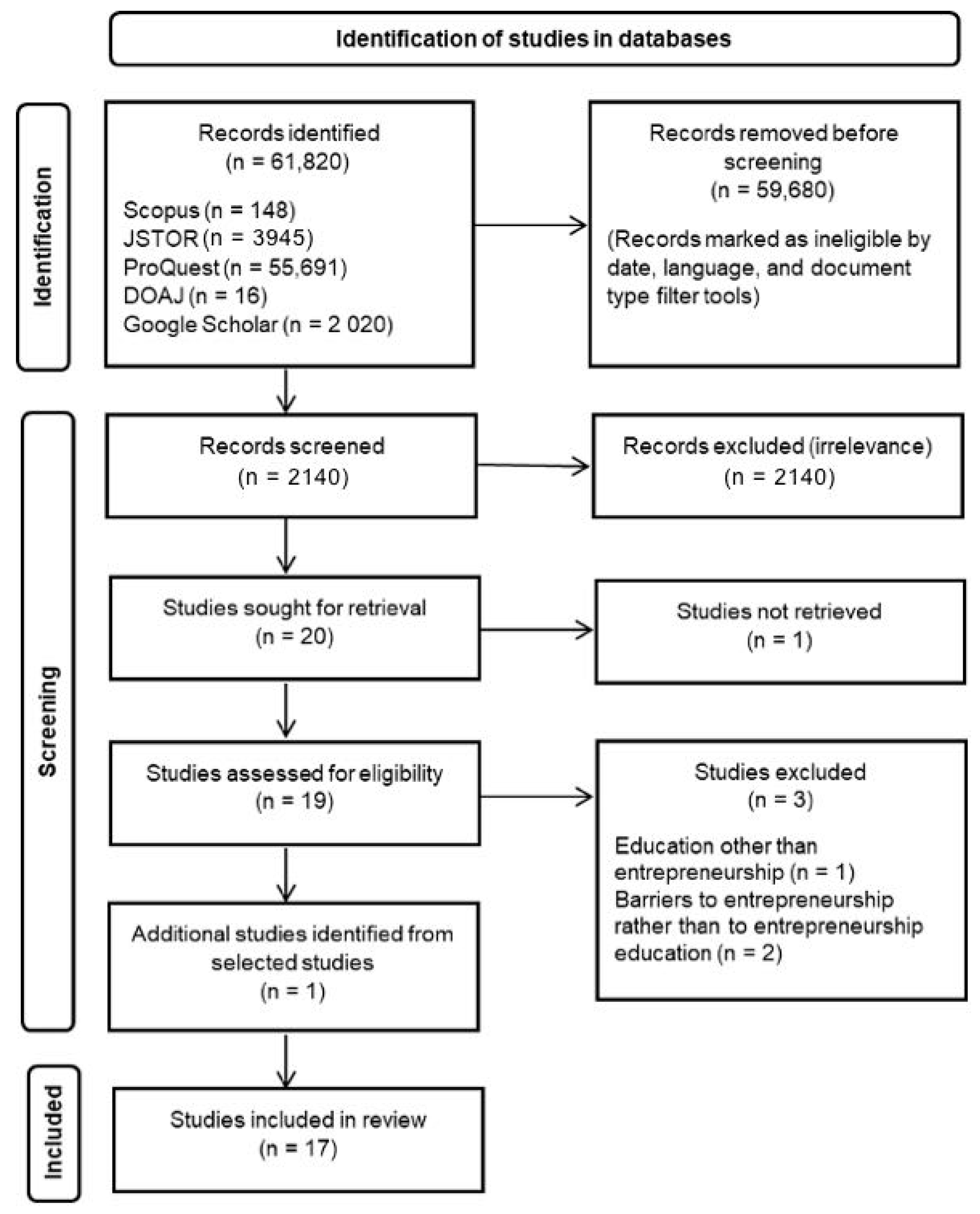

2. Methodology

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process and Quality Assessment

2.4. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Limited Access to Quality Education

3.2. Challenges in Tailoring Entrepreneurship Education

3.3. Strategy to Overcome Barriers and Application to Entrepreneurship Training Programs

- Equitable use: Educational services must be tailored to learners’ needs and capabilities, ensuring utility and accessibility for all. This principle necessitates consideration of both pedagogical methods and the physical or virtual learning environments.

- Flexibility in use: Including all learners in the educational process is crucial, as it promotes their full participation and self-determination. This is achieved through the stages of co-creation and co-production, where learners are actively involved in shaping their educational experiences.

- Simple and intuitive design: Learning materials and teaching methods must be simplified to ensure comprehensibility and ease of use, accommodating diverse learner experiences and competencies.

- Perceptible information: Educational content must be accessible to all learners, regardless of sensory abilities, which may involve adapting content delivery methods.

- Tolerance for error: It is necessary to accommodate different learning abilities and speeds, aiming to minimize frustration and maximize learning outcomes through adaptable teaching strategies.

- Low physical effort: Digital tools, such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), can reduce physical barriers to education, making learning more accessible to those with physical disabilities or those facing geographical constraints.

- Size and space for approach and use: Physical and virtual learning spaces must be designed considering all learners’ access and usability requirements, ensuring that no one is excluded from the educational process due to physical limitations.

3.4. Tailored Education

3.5. The Shift toward Active, Learner-Centred Methodologies

3.6. Use of Information Technology

3.7. Supportive Communities

4. Limitations of This Study

5. Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author (Year) | Title | Methodology | Location | Pertinent Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aeknarajindawat et al. (2019) | Role of essence, objectives, and content of entrepreneurship education programs on their performance: Moderating role of learner disability in Thailand | Quantitative | Thailand | The study explores how entrepreneurship education programs’ core objectives and content impact their performance, particularly when considering the moderating role of learners’ disability. It emphasizes the importance of tailoring educational content to meet the unique needs of learners with disabilities. |

| Dakung et al. (2022) | Entrepreneurship education and the moderating role of inclusion in the entrepreneurial action of disabled students | Quantitative | North-Central Nigeria | The study investigated the influence of inclusive entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial actions of disabled students. It found a positive correlation between inclusive educational practices and entrepreneurial initiatives among students with disabilities. |

| Dakung et al. (2023) | Passion and intention among aspiring entrepreneurs with disabilities: The role of entrepreneurial support programs | Quantitative | Nigeria | The study highlights the critical role of support programs in boosting the passion and intentions of aspiring entrepreneurs with disabilities, emphasizing the need for tailored support that addresses the unique challenges faced by this group. |

| Dakung et al. (2016b) | Robustness of personal initiative in moderating entrepreneurial intentions and actions of disabled students | Quantitative | Plateau State and Abuja, Nigeria | The study suggests that learner-centred pedagogical approaches positively impact entrepreneurial actions, and personal initiative traits such as proactiveness, resilience, and innovation play a crucial role in strengthening the link between the entrepreneurial intentions and actions of disabled students. |

| Dakung et al. (2017) | Self-employability initiative: Developing a practical model of disabled students’ self-employment careers | Quantitative | North-Central Nigeria | The study proposes a practical model for enhancing the self-employability of students with disabilities, focusing on developing entrepreneurial skills and attitudes that support self-employment careers. |

| Dakung et al. (2019) | Developing disabled entrepreneurial graduates: A mission for the Nigerian universities? | Quantitative | North-Central Nigeria | The study underscores universities’ pivotal role in enhancing disabled students’ entrepreneurial intentions through dedicated entrepreneurship education, infrastructure, and role models. It suggests that engaging teaching methods and inspiring role models effectively prepare students for entrepreneurial careers post-graduation. |

| Dakung et al. (2016a) | Disabled students’ entrepreneurial action: The role of religious beliefs | Quantitative | Plateau State and Abuja, Nigeria | The study’s findings indicate that vocational training, social services, and social networks, bolstered by religious group support, positively influence the entrepreneurial actions of disabled students. |

| Fernandez Casado and Minarro Casau (2019) | Physical accessibility, key factor for entrepreneurship in people with disabilities | Qualitative | Not specified | The study stresses the importance of physical accessibility in entrepreneurship education and workspaces for people with disabilities, identifying it as a key factor for their successful participation in entrepreneurial activities. |

| Hamburg and Bucksch (2017) | Inclusive education and digital social innovation | Conceptual | Not specified | The study discusses the potential of digital social innovation to promote inclusive education, including entrepreneurship education for people with disabilities, by leveraging technology to break down barriers. |

| Krüger and David (2020) | Entrepreneurial education for persons with disabilities—A social innovation approach for inclusive ecosystems | Conceptual | Not specified | The study advocates for a social innovation approach to develop inclusive entrepreneurial education ecosystems, emphasizing the importance of universal design principles and the integration of digital technologies. |

| Maulida and Nurbaity (2020) | Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention among disability students in higher education | Qualitative | Jakarta State University, Indonesia | The study examines the impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intentions of higher-education students with disabilities, highlighting the importance of family and peers. |

| Mota et al. (2020) | Handicaps and new opportunity businesses: What do we (not) know about disabled entrepreneurs? | Literature review | General | The study highlights physical accessibility as a key obstacle in entrepreneurship education for disabled individuals, emphasizing the importance of education and training in overcoming these barriers and fostering entrepreneurial attitudes among them. |

| Muñoz et al. (2020) | Sustainability, entrepreneurship, and disability: A new challenge for universities | Quantitative | The University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain | The study emphasizes the role of universities in promoting sustainability entrepreneurship among students with disabilities, calling for the integration of sustainability principles into entrepreneurship education. |

| Muñoz et al. (2019) | Entrepreneurship education and disability: An experience at a Spanish university | Quantitative | The University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain | The study examined the impact of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes, revealing that education level, business experience, and study field significantly influence these attitudes, with no significant differences between disabled and non-disabled students. |

| Prakoso et al. (2019) | Entrepreneurship teaching method for special needs students in BINUS University: A qualitative research approach | Qualitative | BINUS University, Indonesia | The study reveals that BINUS University’s entrepreneurship educators initially lacked awareness of students with special needs, complicating tailored educational planning. It emphasizes the need for lecturer training to accommodate these students better, noting differing engagement levels and learning outcomes between deaf students and those with other disorders, especially in group activities and assessments. |

| Shrivastava and Acharya (2020) | Entrepreneurship education intention and entrepreneurial intention amongst disadvantaged students: an empirical study | Quantitative | Central and Western India | The study finds that socioeconomic disadvantages, including disabilities, negatively impact students’ intentions to pursue entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial activities, underscoring the need for inclusive and supportive educational practices. |

| Zutiasari et al. (2021) | Barriers to entrepreneurship education for disabilities in Indonesia | Literature review | Indonesia | The study identifies specific barriers faced by students with disabilities in Indonesia to access entrepreneurship education, including societal attitudes and lack of resources, and calls for targeted interventions to overcome these barriers. |

References

- Aeknarajindawat, Natnaporn, Preecha Karuhawanit, and Sumneung Maneechay. 2019. Role of Essence, Objectives, and Content of Entrepreneurship Education Programs on Their Performance: Moderating Role of Learner Disability in Thailand. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience 16: 4606–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Disability and Health Overview. Disability and Health Promotion. May 2. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Dakung, Reuel Johnmark, John C. Munene, and Waswa Balunywa. 2016b. Robustness of personal initiative in moderating entrepreneurial intentions and actions of disabled students. Cogent Business and Management 3: 1169575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakung, Reuel Johnmark, John C. Munene, Waswa Balunywa, Laura Orobia, and Mohammed Ngoma. 2017. Self-employability initiative: Developing a practical model of disabled students’ self-employment careers. Africa Journal of Management 3: 280–309. [Google Scholar]

- Dakung, Reuel Johnmark, John Munene, Waswa Balunywa, Joseph Ntayi, and Mohammed Ngoma. 2019. Developing disabled entrepreneurial graduates: A mission for the Nigerian universities? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching and Learning 12: 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakung, Reuel Johnmark, Robin Bell, Laura A. Orobia, and Lemun Yatu. 2022. Entrepreneurship education and the moderating role of inclusion in the entrepreneurial action of disabled students. The International Journal of Management Education 20: 100715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakung, Reuel Johnmark, Robin Bell, Laura Aseru Orobia, Kasmwakat Reuel Dakung, and Lemun Nuhu Yatu. 2023. Passion and intention among aspiring entrepreneurs with disabilities: The role of entrepreneurial support programs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 30: 1241–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakung, Reuel Johnmark, Tsenba Wummen Soemunti, Orobia Laura, John C. Munene, and Waswa Balunywa. 2016a. Disabled students’ entrepreneurial action: The role of religious beliefs. Cogent Business & Management 3: 1252549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Casado, Ana Belen, and Piedad Minarro Casau. 2019. Physical accessibility, key factor for entrepreneurship in people with disabilities. Suma de Negocios 10: 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gusenbauer, Michael, and Neal R. Haddaway. 2020. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Research Synthesis Methods 11: 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamburg, Ileana, and Sascha Bucksch. 2017. Inclusive Education and Digital Social innovation. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 4: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, Daniel, and Alexandra David. 2020. Entrepreneurial Education for Persons With Disabilities—A Social Innovation Approach for Inclusive Ecosystems. Frontiers in Education 5: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulida, Ernita, and Esty Nurbaity. 2020. Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intention among Disability Students in Higher Education. KnE Social Sciences 4: 281–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, Irisalva, Carla Marques, and Octávio Sacramento. 2020. Handicaps and new opportunity businesses: What do we (not) know about disabled entrepreneurs? Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 14: 321–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Rosa Maria, Yolanda Salinero, Isidro Peña, and Jesus David Sanchez de Pablo. 2019. Entrepreneurship Education and Disability: An Experience at a Spanish University. Administrative Sciences 9: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Rosa M., Yolanda Salinero, and M. Valle Fernández. 2020. Sustainability, Entrepreneurship, and Disability: A New Challenge for Universities. Sustainability 12: 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2010. Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers: A Synthesis of Findings across OECD Countries. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/sickness-disability-and-work-breaking-the-barriers_9789264088856-en (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- OECD. 2023. OECD Economic Surveys: European Union and Euro Area 2023. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-surveys-european-union-and-euro-area-2023_7ebe8cc3-en (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Page, Matthew J., David Moher, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakoso, Gatot Hendra, Indriana Indriana, Indira Tyas Widyastuti, and Ira Setyawati. 2019. Entrepreneurship Teaching Method for Special Needs Students in Binus University: A Qualitative Research Approach. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education 22: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, Umesh, and Satya Ranjan Acharya. 2020. Entrepreneurship education intention and entrepreneurial intention amongst disadvantaged students: An empirical study. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 15: 313–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office at Geneva. 2021. DISABILITY-INCLUSIVE LANGUAGE GUIDELINES [Report]. Available online: https://www.ungeneva.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/Disability-Inclusive-Language-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42407/9241545429.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. 2023. Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- World Health Organization, and The World Bank. 2011. World Report on Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Zutiasari, Ika, Wening Patmi Rahayu, Jefry Aulia Martha, and Siti Zumroh. 2021. Barriers to Entrepreneurship Education for Disabilities in Indonesia. Paper presented at the BISTIC Business Innovation Sustainability and Technology International Conference (BISTIC 2021), Online, July 27–28; pp. 150–159. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Search Terms | Records Identified | Filters Applied | Records Screened |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | “entrepreneur” OR “entrepreneurship” OR “entrepreneurial” AND “education” OR “training” AND “disabled” OR “disability” OR “disabilities” | 148 | Year: 2014–2024 Language: English | 137 |

| JSTOR | “entrepreneurship” AND “education” AND “disabled” OR “disability” AND “barrier” | 3945 | Year: 2014–2024 Language: English Academic content: Journals | 162 |

| ProQuest | “entrepreneurship” AND “education” AND “disabled” OR “disability” AND “barrier” OR “barriers” | 55,691 | Date: 1–31 January 2024 Language: English Limit to: Full text and Peer reviewed Source type: Scholarly Journals Document type: Article Subject: Education | 315 |

| DOAJ | “entrepreneurship” “education” “disabled” | 16 | Year: 2014–2024 | 16 |

| Google Scholar | “entrepreneurship education” “disabled” “barriers” | 2020 | Year: 2014–2024 Include: Citations | 1510 |

| 61,820 | 2140 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tiasakul, S.; Abdulzaher, R.; Bazan, C. Accessibility of Entrepreneurship Training Programs for Individuals with Disabilities: A Literature Review. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080187

Tiasakul S, Abdulzaher R, Bazan C. Accessibility of Entrepreneurship Training Programs for Individuals with Disabilities: A Literature Review. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(8):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080187

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiasakul, Somrudee, Ramy Abdulzaher, and Carlos Bazan. 2024. "Accessibility of Entrepreneurship Training Programs for Individuals with Disabilities: A Literature Review" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 8: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080187

APA StyleTiasakul, S., Abdulzaher, R., & Bazan, C. (2024). Accessibility of Entrepreneurship Training Programs for Individuals with Disabilities: A Literature Review. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14080187