Combined Vital Tooth Whitening: Effect of Number of In-Office Sessions on the Duration of Home Whitening. A Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

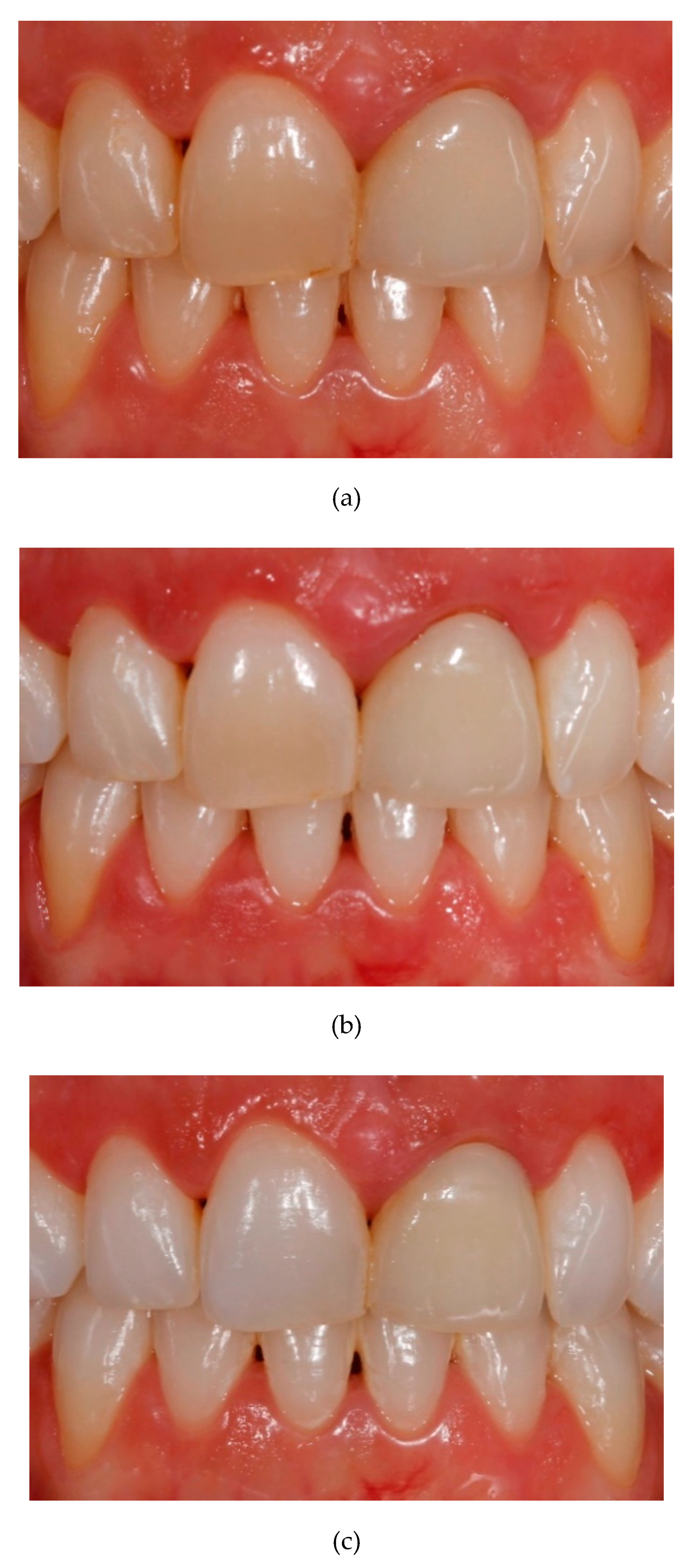

:Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Patient Selection

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kugel, G.; Perry, R.D.; Hoang, E.; Scherer, W. Effective tooth bleaching in 5 days: Using a combined in-office and at-home bleaching system. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 1997, 18, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barghi, N. Making a clinical decision for vital tooth bleaching: At home or in-office? Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 1998, 19, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.R.; Ko, S.H.; Greenwall, L. Home Whitening: Tooth Whiteningin Esthetic Dentistry; Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.: Singapore, 2009; pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, J.E.; Pallesen, U. Tooth bleaching-a critical review of the biological aspects. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 2003, 14, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, A.F.M.; Maran, B.; Araújo, L.C.R.; de Siquiera, F.S.F.; Wambier, L.M.; Gonzaga, C.C.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A. Are combined bleaching techniques better than their sole application? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2019, 23, 3673–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aren, G. In vitro effects of bleaching agents on FM3A cell line. Quintessence. Int. 2003, 34, 361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kihn, P.W. Vital Tooth Whitening. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 51, 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Deliperi, S.; Bardwell, D.N.; Papathanasiou, A. Clinical evaluation of a combined in-office and take-home bleaching system. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 35, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matis, B.A.; Cochran, M.A.; Wang, G.; Eckert, G.J. A clinical evaluation of two in-office bleaching regimens with and without tray bleaching. Oper. Dent. 2009, 34, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, J.L.; Rocha, P.S.; Pardim, S.; Machado, A.C.V.; Faria-e-Silva, A.L.; Seraidarian, P.I. Association Between In-Office and At-Home Tooth Bleaching: A Single Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Braz. Dent. J. 2018, 29, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radz, G.M. Effectiveness of a combined in-office and take-home whitening system for teeth shades A3. 5 to A4. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2014, 35, 696–700. [Google Scholar]

- Dourado Pinto, A.V.; Carlos, N.R.; Amaral, F.L.B.D.; França, F.M.G.; Turssi, C.P.; Basting, R.T. At-home, in-office and combined dental bleaching techniques using hydrogen peroxide: Randomized clinical trial evaluation of effectiveness, clinical parameters and enamel mineral content. Am. J. Dent. 2019, 32, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marson, F.C.; Sensi, L.G.; Vieira, L.C.C.; Araújo, E. Clinical Evaluation of In-office Dental Bleaching Treatments with and Without the Use of Light-activation Sources. Oper. Dent. 2008, 33, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Faus-Matoses, V.; Palau-Martínez, I.; Amengual-Lorenzo, J.; Faus-Matoses, I.; Faus-Llácer, V.J. Bleaching in vital teeth: Combined treatment vs. in-office treatment. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekonis, R.; Matis, B.A.; Cochran, M.A.; Al Shetri, S.E.; Eckert, G.J.; Carlson, T.J. Clinical evaluation of in-office and at-home bleaching treatments. Oper. Dent. 2003, 28, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Kakehashi, Y.; Matsumura, H.; Tanoue, N. In vivo quantitative evaluation of tooth color with hand-held colorimeter and custom template. J. prosthet. Dent. 2004, 91, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, A.R.; Lozano, R.D.; Alman, D.H.; Orchard, S.E.; Keitch, J.A.; Connely, R.; Graham, L.A.; Acree, W.L.; John, R.S.; Hoban, R.F.; et al. CIE Recommendations on uniform color-spaces, color difference equations, and metric color terms. Color Res. Appl. 1977, 2, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S.M.; Bottone, P.W. Tray-forming technique for dentist-supervised home bleaching. Quintessence Int. 1995, 26, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Román-Rodríguez, J.L.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Roig-Vanaclocha, A.; Amengual, J.A. Tooth whitening and chemical abrasive protocol for the treatment of developmental enamel defects. J. prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Filho, L.C.; da Costa, C.C.; Soria, M.L.; Taga, R. Effect of home bleaching and smoking on marginal gingival epithelium proliferation: A histologic study in women. J. Oral. pathol. Med. 2002, 31, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskersoy, C.; Tetik, A.; Ozturk, V.O.; Gokay, N. Spectrophotometric and computerized evaluation of tooth bleaching employing 10 different home-bleaching procedures: In-vitro study. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.M.; Hintz, J. Case report: In-office tooth whitening procedure with 35% carbamide peroxide evaluated by the Minolta CR-321 Chroma Meter. J. Esthet. Dent. 1998, 10, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Handling, Care and Maintenance Instructions for Home Dental Whitening Splints |

|---|

| 1. Before putting on the trays, brush your teeth properly and use dental floss to clean the spaces between the teeth before each application of your bleaching splint. |

| 2. Clean the trays with your toothbrush and cold water before putting them in your mouth. |

| 3. Dry the trays with a towel or tissue. |

| 4. Distribute a small amount of gel in each of the holes in the tray corresponding to the teeth to be bleached. |

| 5. Distribute the gel with the brush that has been delivered to all the holes. |

| 6. Insert the whitening trays into the mouth until they seat properly. |

| 7. Clean the excess gel that comes out of the trays and the gel that is in contact with the gums. |

| 8. Wear trays for 90 minutes each day |

| 9. At the end of the application time of the whitening gel, remove the trays and remove the rest of the product from your teeth by brushing. |

| 10. Rinse the trays with cold water and clean them with a toothbrush. |

| 11. Dry the trays and store them in their box. |

| Group | ΔE after In-Office Whitening | ΔE after Home Whitening | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Media 95% CI | Phase Media 95% CI | ||

| 1S (one-session) | 3.84 | 14.1 | Wilcoxon test p < 0.001 * |

| N = 57 teeth | 3.20–4.73 | 12.9–15.3 | |

| 2S (two-session) | 3.79 | 12.8 | Wilcoxon test p < 0.001 * |

| N = 58 teeth | 3.24–4.34 | 11.7–14.0 | |

| Mann–Whitney U test | Mann–Whitney U test | ||

| p = 0.827 | p = 0.120 | ||

| Color Parameter | Group | Initial | After In-Office Whitening | After Home Whitening | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 95% CI | Mean 95% CI | Mean 95% CI | ||||

| L* | 1S | 80.5 | 82.1 | W test | 86.4 | W test |

| 78.9–82.0 | 80.6–83.6 | p = 0.002 * | 85.2–87.5 | p < 0.001 * | ||

| 2S | 79.9 | 81.9 | W test | 85.1 | W test | |

| 78.7–81.1 | 80.6–83.2 | p < 0.001 * | 83.8–86.3 | p < 0.001 * | ||

| U test | U test | U test | ||||

| p = 0.317 | p = 0.589 | p = 0.154 | ||||

| a* | 1S | −0.43 | −0.49 | W test | −2.20 | W test |

| −0.76–−0.09 | −0.80–−0.18 | p = 0.471 | −2.35–−2.05 | p < 0.001 * | ||

| 2S | −0.12 | −0.50 | W test | −1.89 | W test | |

| −0.45–−0.20 | −0.80–−0.20 | p = 0.001 * | −2.03–−1.62 | p < 0.001 * | ||

| U test | U test | U test | ||||

| p = 0.165 | p = 0.935 | p = 0.033 * | ||||

| b* | 1S | 21.2 | 20.1 | W test | 9.72 | W test |

| 19.5–22.9 | 18.6–21.5 | p < 0.001 * | 8.82–10.6 | p < 0.001 * | ||

| 2S | 22.8 | 20.9 | W test | 11.5 | W test | |

| 21.2–24.5 | 19.4–22.2 | p < 0.0001 * | 10.4–12.7 | p < 0.001 * | ||

| U test | U test | U test | ||||

| p = 0.176 | p = 0.548 | p = 0.008 * |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amengual-Lorenzo, J.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Labaig-Rueda, C.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Solá-Ruíz, M.F.; Peydro-Herrero, M. Combined Vital Tooth Whitening: Effect of Number of In-Office Sessions on the Duration of Home Whitening. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134476

Amengual-Lorenzo J, Montiel-Company JM, Labaig-Rueda C, Agustín-Panadero R, Solá-Ruíz MF, Peydro-Herrero M. Combined Vital Tooth Whitening: Effect of Number of In-Office Sessions on the Duration of Home Whitening. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(13):4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134476

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmengual-Lorenzo, José, José María Montiel-Company, Carlos Labaig-Rueda, Rubén Agustín-Panadero, María Fernanda Solá-Ruíz, and Marta Peydro-Herrero. 2020. "Combined Vital Tooth Whitening: Effect of Number of In-Office Sessions on the Duration of Home Whitening. A Randomized Clinical Trial" Applied Sciences 10, no. 13: 4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134476

APA StyleAmengual-Lorenzo, J., Montiel-Company, J. M., Labaig-Rueda, C., Agustín-Panadero, R., Solá-Ruíz, M. F., & Peydro-Herrero, M. (2020). Combined Vital Tooth Whitening: Effect of Number of In-Office Sessions on the Duration of Home Whitening. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Applied Sciences, 10(13), 4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10134476