Immersive Virtual Reality High-Intensity Aerobic Training to Slow Parkinson’s Disease: The ReViPark Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

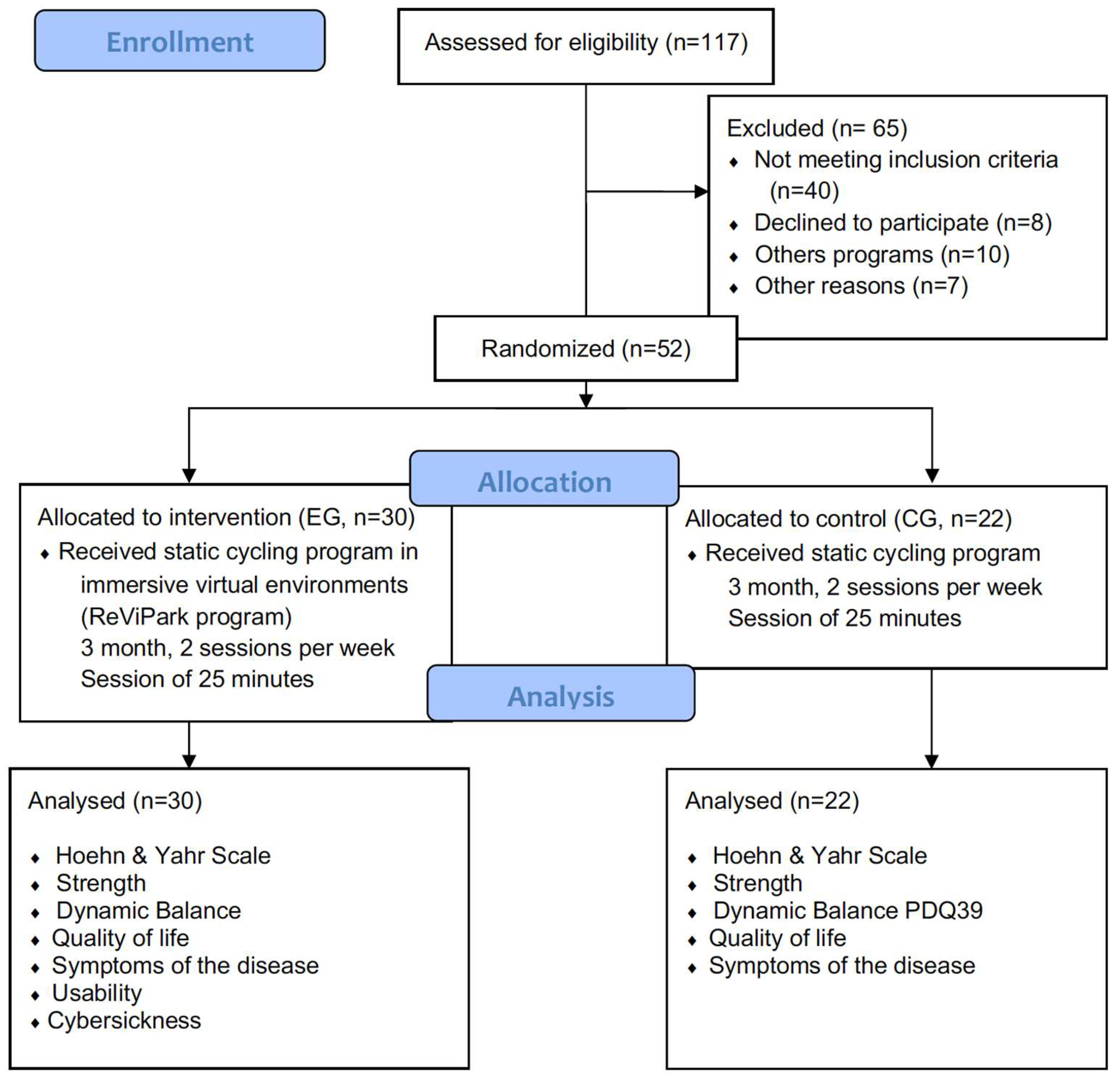

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Evaluation Tools

2.3.1. Pre- and Post-Intervention Assessment

- For the sociodemographic and pharmacological characteristics of the sample, an ad hoc questionnaire was conducted where the following variables were collected: age, sex, years since Parkinson’s diagnosis, first symptom of the disease, as well as any antiparkinsonian pharmacological treatment being received.

- Regarding functional aspects, the following variables were analyzed:

- For dynamic balance, we used the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test [34]. This test evaluates basic functional mobility of the subject, in addition to dynamic and static balance and the risk of falling [35]. As well as the basic version of the test, it was also performed with the addition of a simultaneous double task. (The participants performed mathematical operations.)

- For quality of life, the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) [40,41] was used to assess this aspect. The PDQ-39 scale assesses 8 different domains: mobility (10 items), activities of daily living (6 items), emotional well-being (6 items), stigma (4 items), social support (3 items), cognitive status (4 items), communication (3 items), and bodily discomfort (3 items).

- With regard to symptomatology and follow-ups, the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) [42] was used for this purpose. It is made up of four parts: Part I (non-motor experiences of daily living), Part II (motor experiences of daily living), Part III (motor exploration), and Part IV (motor complications).

2.3.2. Specific Evaluation of the EG

- Personal impressions were evaluated with the post-game module of the Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ-post game) [48]. The GEQ-post game questionnaire assesses four components: positive experiences, negative experiences, fatigue, and return to reality. In the absence of a validated version of the questionnaire in Spanish, and for ease of understanding, the questionnaire was translated by the authors and has been used in previous research [49,50].

2.4. Intervention Program

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.Y.; Ahmed, M.B.; Aichour, A.N.; Aichour, I.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 877–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.P.B.; Lobato, D.F.M.; Smaili, A.M.; Carvalho, C.; Borges, J.B.C. Effect of aerobic exercise on functional capacity and quality of life in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 95, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politis, M.; Wu, K.; Molloy, S.; Bain, P.G.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Piccini, P. Parkinson’s disease symptoms: The patient’s perspective: PD Symptoms: The Patient’s Perspective. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlskog, J.E. Aerobic Exercise: Evidence for a Direct Brain Effect to Slow Parkinson Disease Progression. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo Prieto, P.; Santos García, D.; Cancela Carral, J.M.; Rodríguez Fuentes, G. Estado actual de la realidad virtual inmersiva como herramienta de rehabilitación física y funcional en pacientes con enfermedad de Parkinson: Revisión sistemática. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 73, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Cancela-Carral, J.M. Can Immersive Virtual Reality Videogames Help Parkinson’s Disease Patients? A Case Study. Sensors 2021, 21, 4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.Y.; Cho, K.H.; Jin, C.; Lee, J.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, W.S.; Moon, S.K.; Ko, C.N.; Cho, S.Y.; Jeon, C.Y.; et al. Exercise Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise, K.e.; Bucks, R.S.; Loftus, A.M.; Newton, R.U.; Pegoraro, R.; Thomas, M.G. Exercise and Parkinson’s: Benefits for cognition and quality of life: Exercise and Parkinson’s: Cognition, mood and QoL. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2011, 123, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keus, S.H.J.; Bloem, B.R.; Hendriks, E.J.M.; Bredero-Cohen, A.B.; Munneke, M.; on behalf of the Practice Recommendations Development Group. Evidence-based analysis of physical therapy in Parkinson’s disease with recommendations for practice and research. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.K.; Wong-Yu, I.S.; Shen, X.; Chung, C.L. Long-term effects of exercise and physical therapy in people with Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, D.G.; Aron, A.; DiSalvo, E. Therapeutic effects of forced exercise cycling in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 410, 116677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.-Y.; Yang, Y.-R.; Chen, L.-M.; Wu, Y.-R.; Cheng, S.-J.; Wang, R.-Y. Positive Effects of Specific Exercise and Novel Turning-based Treadmill Training on Turning Performance in Individuals with Parkinson’s disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, J.L.; Phillips, M.; Lowe, M.J.; Frankemolle, A.; Thota, A.; Beall, E.B.; Feldman, M.; Ahmed, A.; Ridgel, A.L. Cortical and motor responses to acute forced exercise in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.E.; Li, Q.; Nacca, A.; Salem, G.J.; Song, J.; Yip, J.; Hui, J.S.; Jakowec, M.W.; Petzinger, G.M. Treadmill exercise elevates striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport 2013, 24, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludyga, S.; Gronwald, T.; Hottenrott, K. Effects of high vs. low cadence training on cyclists’ brain cortical activity during exercise. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2016, 9, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.; Teixeira, D.; Monteiro, D.; Imperatori, C.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; da Silva Rocha, F.P.; Yamamoto, T.; Amatriain-Fernández, S.; Budde, H.; Carta, M.G.; et al. Clinical applications of exercise in Parkinson’s disease: What we need to know? Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2022, 22, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzinger, G.M.; Fisher, B.E.; McEwen, S.; Beeler, J.A.; Walsh, J.P.; Jakowec, M.W. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgel, A.L.; Vitek, J.L.; Alberts, J.L. Forced, Not Voluntary, Exercise Improves Motor Function in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009, 23, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Laat, B.; Hoye, J.; Stanley, G.; Hespeler, M.; Ligi, J.; Mohan, V.; Wooten, D.W.; Zhang, X.; Nguyen, T.D.; Key, J.; et al. Intense exercise increases dopamine transporter and neuromelanin concentrations in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2024, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, E.B.; Lowe, M.J.; Alberts, J.L.; Frankemolle, A.M.; Thota, A.K.; Shah, C.; Phillips, M.D. The Effect of Forced-Exercise Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease on Motor Cortex Functional Connectivity. Brain Connect. 2013, 3, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, D.B.; Peer, K.S.; Ridgel, A.L. Biomechanical muscle stimulation and active-assisted cycling improves active range of motion in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2013, 33, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupheimer, M.; Härtel, S.; Schmidt, S.; Bös, K. Forced Exercise—Effects of MOTOmed® exercise on typical motor dysfunction in Parkinson s disease. Neurol. Rehabil. 2011, 17, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgel, A.L.; Phillips, R.S.; Walter, B.L.; Discenzo, F.M.; Loparo, K.A. Dynamic High-Cadence Cycling Improves Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 162442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgel, A.L.; Ault, D.L. High-Cadence Cycling Promotes Sustained Improvement in Bradykinesia, Rigidity, and Mobility in Individuals with Mild-Moderate Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2019, 2019, 4076862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuckenschneider, T.; Helmich, I.; Raabe-Oetker, A.; Froböse, I.; Feodoroff, B. Active assistive forced exercise provides long-term improvement to gait velocity and stride length in patients bilaterally affected by Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 2015, 42, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlskog, J.E. Does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson disease? Neurology 2011, 77, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgel, A.L.; Peacock, C.A.; Fickes, E.J.; Kim, C.-H. Active-Assisted Cycling Improves Tremor and Bradykinesia in Parkinson’s Disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 2049–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, C.A.; Sanders, G.J.; Wilson, K.A.; Fickes-Ryan, E.J.; Corbett, D.B.; von Carlowitz, K.P.A.; Ridgel, A.L. Introducing a multifaceted exercise intervention particular to older adults diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease: A preliminary study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2014, 26, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller Koop, M.; Rosenfeldt, A.B.; Alberts, J.L. Mobility improves after high intensity aerobic exercise in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 399, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Immersive virtual reality as physical therapy in older adults: Present or future (systematic review). Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Sathyaprabha, T.N.; Gupta, A.; Pal, P.K. Effect of Partial Weight–Supported Treadmill Gait Training on Balance in Patients With Parkinson Disease. PM&R 2014, 6, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Buchner, A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1996, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Dunn, L. The Declaration of Helsinki on Medical Research involving Human Subjects: A Review of Seventh Revision. J. Nepal. Health Res. Counc. 2020, 17, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocera, J.R.; Stegemöller, E.L.; Malaty, I.A.; Okun, M.S.; Marsiske, M.; Hass, C.J. Using the Timed Up & Go Test in a Clinical Setting to Predict Falling in Parkinson’s Disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, R.P.; Leddy, A.L.; Earhart, G.M. Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test Performance in Parkinson’s Disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1431–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, A.; Chavis, M.; Watkins, J.; Wilson, T. The five-times-sit-to-stand test: Validity, reliability and detectable change in older females. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kegelmeyer, D.A.; Kloos, A.D.; Thomas, K.M.; Kostyk, S.K. Reliability and Validity of the Tinetti Mobility Test for Individuals With Parkinson Disease. Phys. Ther. 2007, 87, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Franklin Williams, T.; Mayewski, R. Fall risk index for elderly patients based on number of chronic disabilities. Am. J. Med. 1986, 80, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Peto, V.; Greenhall, R.; Hyman, N. The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): Development and validation of a Parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martín, P.; Payo, B.F.; The Grupo Centro for Study of Movement Disorders. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: Validation study of the PDQ-39 Spanish version. J. Neurol. 1998, 245, S34–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Cancela Carral, J.M. Traducción y adaptación transcultural al español del Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (Translation and cross-cultural adaptation to Spanish of the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire). Retos 2021, 43, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Lane, N.E.; Berbaum, K.S.; Lilienthal, M.G. Simulator Sickness Questionnaire: An Enhanced Method for Quantifying Simulator Sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 1993, 3, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Drexler, J.; Kennedy, R.C. Research in visually induced motion sickness. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlefs Aguilar, M.I.; Garza Villegas, A.A. Análisis comparativo de la Escala de Usabilidad del Sistema (EUS) en dos versiones. RECI 2016, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsselsteijn, W.A.; de Kort, Y.A.W. The Game Experience Questionnaire; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Cancela-Carral, J.M. Immersive Virtual Reality Exergame Promotes the Practice of Physical Activity in Older People: An Opportunity during COVID-19. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Feasibility and Effects of an Immersive Virtual Reality Exergame Program on Physical Functions in Institutionalized Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Sensors 2022, 22, 6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Wearable Immersive Virtual Reality Device for Promoting Physical Activity in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Sensors 2022, 22, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, J.L.; Linder, S.M.; Penko, A.L.; Lowe, M.J.; Phillips, M. It Is Not About the Bike, It Is About the Pedaling: Forced Exercise and Parkinson’s Disease. Exerc. Sport. Sci. Rev. 2011, 39, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollinedo Cardalda, I.; Pereira Pedro, K.-P.; López Rodríguez, A.; Cancela Carral, J.M. Aplicación de un programa de ejercicio físico coordinativo a través del sistema MOTOmed® en personas mayores diagnosticadas de Enfermedad de Parkinson moderado-severo. Estudio de casos. Retos 2021, 39, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carels, R.A.; Berger, B.; Darby, L. The Association between Mood States and Physical Activity in Postmenopausal, Obese, Sedentary Women. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2006, 14, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.M.; Dunsiger, S.; Ciccolo, J.T.; Lewis, B.A.; Albrecht, A.E.; Marcus, B.H. Acute affective response to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2008, 9, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, F.D.; Joly, P.M.; Bertucci, W.M.; Soudain-Pineau, M.A.; Marcel, J. Interactive-Virtual Reality (IVR) Exercise: An Examination of In-Task and Pre-to-Post Exercise Affective Changes. J. Appl. Sport. Psychol. 2011, 23, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, A.J.; Drury, D.G.; Danoff, J.V.; Miller, T.A. Comparison of Acute Exercise Responses Between Conventional Video Gaming and Isometric Resistance Exergaming. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 1799–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, S.; Pinsker, R.; Naik, R.; Noah, J.A. Physiological and psychophysiological responses to an exer-game training protocol. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2016, 19, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, C.; Schofield, D. Running virtual: The effect of virtual reality on exercise. J. Human. Sport. Exerc. 2019, 15, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Browne, J.D.; Arnold, M.T.; Robinson, A.; Heacock, M.F.; Ku, R.; Mologne, M.; Baum, G.R.; Ikemiya, K.A.; Neufeld, E.V.; et al. Physiological and Metabolic Requirements, and User-Perceived Exertion of Immersive Virtual Reality Exergaming Incorporating an Adaptive Cable Resistance System: An Exploratory Study. Games Health J. 2021, 10, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.; Browne, J.D.; Almalouhi, A.; Abundex, M.; Hu, J.; Nason, S.; Kull, N.; Mills, C.; Harris, Q.; Ku, R.; et al. Muscle Activity During Immersive Virtual Reality Exergaming Incorporating an Adaptive Cable Resistance System. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 15, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mologne, M.S.; Hu, J.; Carrillo, E.; Gomez, D.; Yamamoto, T.; Lu, S.; Browne, J.D.; Dolezal, B.A. The Efficacy of an Immersive Virtual Reality Exergame Incorporating an Adaptive Cable Resistance System on Fitness and Cardiometabolic Measures: A 12-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeldt, A.B.; Koop, M.M.; Fernandez, H.H.; Alberts, J.L. High intensity aerobic exercise improves information processing and motor performance in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2021, 239, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, K.; Zhang, S.; Tao, X.; Li, G.; Lv, Y.; Yu, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis on effects of aerobic exercise in people with Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runswick, O.R.; Siegel, L.; Rafferty, G.F.; Knudsen, H.S.; Sefton, L.; Taylor, S.; Reilly, C.C.; Finnegan, S.; Sargeant, M.; Pattinson, K.; et al. The Effects of Congruent and Incongruent Immersive Virtual Reality Modulated Exercise Environments in Healthy Individuals: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T.H.; Villaneuva, K.; Hahn, A.; Ortiz-Delatorre, J.; Wolf, C.; Nguyen, R.; Bolter, N.D.; Kern, M.; Bagley, J.R. Actual vs. perceived exertion during active virtual reality game exercise. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 887740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.-L.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Wu, R.-M.; Tai, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Lu, W.S. Minimal Detectable Change of the Timed “Up & Go” Test and the Dynamic Gait Index in People With Parkinson Disease. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, L.M.; Gruber-Baldini, A.L.; Anderson, K.E.; Fishman, P.S.; Reich, S.G.; Weiner, W.J. The Clinically Important Difference on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, K.; Aschermann, Z.; Ács, P.; Deli, G.; Janszky, J.; Komoly, S.; Balázs, É.; Takács, K.; Karádi, K.; Kovács, N. Minimal clinically important difference on the Motor Examination part of MDS-UPDRS. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Bang, M.; Krivonos, D.; Schimek, H.; Naval, A. An Immersive Virtual Reality Exergame for People with Parkinson’s Disease. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Miesenberger, K., Manduchi, R., Covarrubias Rodriguez, M., Peňáz, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.; Darakjian, N.; Finley, J.M. Walking in fully immersive virtual environments: An evaluation of potential adverse effects in older adults and individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. NeuroEngineering Rehabil. 2017, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | All (n = 52) | EG (MOTOmed® + IVR) (n = 30) | CG (MOTOmed®) (n = 22) | Student’s t and Chi-Squared Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.79 ± 6.59 | 70.87 ± 6.67 | 70.59 ± 6.67 | t = 0.127; p = 0.899 |

| Sex (% of women) | 42.31 | 36.67 | 50 | |

| Time diagnosed (years) | 6.40 ± 4.77 | 5.60 ± 4.06 | 8.23 ± 5.88 | t = 1.470; p = 0.080 |

| Hoehn and Yahr scale | 1.82 ± 0.87 | 1.71 ± 0.90 | 2.08 ± 0.76 | t = −1.287; p = 0.103 |

| Stage 1 (%) | 37.30 | 51.60 | 23.10 | Chi = 5.613; p = 0.132 |

| Stage 2 (%) | 39.23 | 32.30 | 46.15 | |

| Stage 3 (%) | 23.47 | 16.20 | 30.75 | |

| First symptom | ||||

| Tremors (%) | 40.80 | 38.70 | 42.90 | Chi = 4.729; p = 0.193 |

| Rigidity (%) | 20.75 | 12.90 | 28.60 | |

| Bradikinesia (%) | 17.15 | 12.90 | 21.40 | |

| Other (%) | 21.30 | 35.50 | 7.10 | |

| Pharmacology | ||||

| Equivalent dose of levodopa LEDD (mg) | 532.33 ± 229.75 | 538.94 ± 161.92 | 526.33 ± 297.53 | t = 1.001; p = 0.129 |

| EG (MOTOmed® + IVR) (n = 30) | CG (MOTOmed®) (n = 22) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Average ± SD | Average ± SD | Student’s t Test Results | |

| Pre-intervention | Strength of lower train | |||

| Five sit to stand (s) | 14.30 ± 5.42 | 13.08 ± 3.00 | t = 0.901; p = 0.186 | |

| Dynamic balance | ||||

| Time up and go (s) | 14.08 ± 18.28 | 12.46 ± 9.19 | t = 0.359; p = 0.361 | |

| Time up and go + cognitive task (s) | 17.64 ± 26.02 | 14.51 ± 11.95 | t = 0.495; p = 0.312 | |

| Tinetti scale | ||||

| Balance (pts) | 12.89 ± 3.54 | 14.80 ± 1.77 | t = −2.143; p = 0.019 | |

| Gait (pts) | 9.47 ± 1.87 | 10.20 ± 2.55 | t = −1.011; p = 0.159 | |

| Total (pts) | 22.37 ± 4.88 | 25.00 ± 3.87 | t = −1.872; p = 0.035 | |

| Post-intervention | Strength of lower train | |||

| Five sit to stand (s) | 13.81 ± 6.68 | 13.18 ± 4.54 | t = 0.336; p = 0.369 | |

| Dynamic balance | ||||

| Time up and go (s) | 10.16 ± 6.42 | 13.70 ± 4.51 | t = −1.589; p = 0.040 | |

| Time up and go + cognitive task (s) | 11.59 ± 9.27 | 14.57 ± 12.52 | t = −1.828; p = 0.206 | |

| Tinetti scale | ||||

| Balance (pts) | 15.00 ± 2.53 | 15.33 ± 1.59 | t = −0.465; p = 0.322 | |

| Gait (pts) | 11.37 ± 1.40 | 9.75 ± 2.93 | t = 2.540; p = 0.007 | |

| Total (pts) | 26.37 ± 3.54 | 25.53 ± 3.64 | t = 0.736; p = 0.233 |

| EG (MOTOmed® + IVR) (n = 30) | CG (MOTOmed®) (n = 22) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Average ± SD | Average ± SD | Student’s t Test Results | |

| Pre-intervention | PDQ-39 | |||

| Mobility | 19.19 ± 23.02 | 29.25 ± 28.78 | t = −1.380; p = 0.087 | |

| Activities of daily living | 16.67 ± 19.75 | 22.92 ± 21.48 | t = −1.066; p = 0.146 | |

| Emotional well-being | 20.16 ± 15.92 | 32.24 ± 24.80 | t = −2.101; p = 0.020 | |

| Stigma | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | t = −1.001; p = 0.161 | |

| Social support | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | t = −1.603; p = 0.058 | |

| Cognition | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | t = −2.804; p = 0.004 | |

| Communication | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | t = −0.949; p = 0.174 | |

| Physical discomfort | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | t = −1.887; p = 0.033 | |

| Total score | 7.01 ± 5.55 | 10.79 ± 7.53 | t = −2.037; p = 0.024 | |

| MDS_UPDRS | ||||

| Part IA: Non-motor experiences of daily living | 10.42 ± 12.70 | 22.50 ± 19.75 | t = −2.691; p = 0.005 | |

| Part IB: Non-motor experiences of daily living | 15.92 ± 12.41 | 25.47 ± 17.12 | t = −2.329; p = 0.012 | |

| Part II: Motor experiences of daily living | 15.81 ± 16.51 | 19.90 ± 14.61 | t = −0.909; p = 0.184 | |

| Part III: Motor evaluation | 11.79 ± 12.72 | 20.19 ± 16.91 | t = −2.039; p = 0.023 | |

| Part IV: Motor complications | 2.99 ± 8.99 | 23.12 ± 31.83 | t = −3.385; p = 0.001 | |

| Total score | 21.86 ± 18.82 | 42.70 ± 31.33 | t = −3.003; p = 0.002 | |

| Post-intervention | PDQ-39 | |||

| Mobility | 14.08 ± 19.61 | 24.53 ± 22.46 | t = −1.636; p = 0.054 | |

| Activities of daily living | 14.78 ± 19.92 | 22.14 ± 19.53 | t = −1.207; p = 0.117 | |

| Emotional well-being | 22.58 ± 17.24 | 30.47 ± 26.95 | t = −1.221; p = 0.114 | |

| Stigma | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | t = −3.548; p = 0.001 | |

| Social support | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | t = −0.188; p = 0.426 | |

| Cognition | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | t = −3.699; p = 0.001 | |

| Communication | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | t = 0.776; p = 0.221 | |

| Physical discomfort | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | t = −2.379; p = 0.011 | |

| Total score | 6.41 ± 4.90 | 9.70 ± 6.46 | t = −1.858; p = 0.035 | |

| MDS_UPDRS | ||||

| Part IA: Non-motor experiences of daily living | 9.44 ± 10.94 | 22.66 ± 20.97 | t = −2.822; p = 0.004 | |

| Part IB: Non-motor experiences of daily living | 12.19 ± 7.63 | 25.20 ± 17.58 | t = −3.505; p = 0.001 | |

| Part II: Motor experiences of daily living | 10.64 ± 10.32 | 18.51 ± 16.06 | t = −2.021; p = 0.025 | |

| Part III: Motor evaluation | 5.40 ± 6.69 | 18.47 ± 15.81 | t = −3.939 p = 0.001 | |

| Part IV: Motor complications | 1.67 ± 4.46 | 5.73 ± 12.06 | t = −1.657; p = 0.052 | |

| Total score | 15.11 ± 9.80 | 34.77 ± 23.36 | t = −4.023; p = 0.001 |

| Difference between Final and Initial | 95% Confidence Interval (Lower; Upper) | ANOVA 2 × 2 Time (Pre and Post) × Group (EG and CG) (F, p, η2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strength of lower train | ||||

| Five sit to stand (s) | GE | 0.488 | −2.847; −3.824 | F1.91 = 0.066; p = 0.798; η2 = 0.01 |

| GC | −0.103 | −2.665; −2.45 | ||

| Dynamic balance | ||||

| Time up and go (s) | GE | 3.919 | −3.262; 11.100 | F1.91 = 1.302; p = 0.028; η2 = 0.12 |

| GC | −2.116 | −9.803; 5.570 | ||

| Time up and go + cognitive task (s) | GE | 6.048 | −4.295; 16.291 | F1.91 = 2.577; p = 0.015; η2 = 0.16 |

| GC | 0.813 | −5.181; 6.808 | ||

| Tinetti scale | ||||

| Balance (pts) | GE | −2.105 | −3.851; −0.359 | F1.91 = 1.927; p = 0.016; η2 = 0.18 |

| GC | −0.533 | −1.693; 0.626 | ||

| Gait (pts) | GE | −1.892 | −2.834; −0.951 | F1.91 = 6.024; p = 0.016; η2 = 0.07 |

| GC | 0.450 | −1.445; 2.345 | ||

| Total (pts) | GE | −3.998 | −6.421: −1.574 | F1.91 = 3.753; p = 0.046; η2 = 0.05 |

| GC | −0.533 | −0.3137; 2.071 | ||

| PDQ-39 | ||||

| Mobility | GE | 5.110 | −5.862; 16.082 G | F1.96 = 0.002; p = 0.968; η2 = 0.001 |

| GC | 4.718 | −13.126; 22.075 | ||

| Activities of daily living | GE | 1.881 | −8.195; 11.959 | F1.96 = 0.017; p = 0.897; η2 = 0.001 |

| GC | 0.7812 | −13.288; 14.851 | ||

| Emotional well-being | GE | −2.419 | −10.851; 6.013 G | F1.96 = 0.236; p = 0.628; η2 = 0.003 |

| GC | 1.768 | −16.041; 19.577 | ||

| Stigma | GE | 0.003 | −0.002; 0.008 G | F1.96 = 3.929; p = 0.049; η2 = 0.04 |

| GC | −0.010 | −0.025; 0.005 | ||

| Social support | GE | −0.004 | −0.155; 0.006 | F1.96 = 0.418; p = 0.519; η2 = 0.004 |

| GC | 0.001 | −0.012; 0.015 | ||

| Cognition | GE | 0.002 | −0.008; 0.013 | F1.95 = 1.496; p = 0.224; η2 = 0.016 |

| GC | −0.118 | −0.334; 0.102 | ||

| Commuication | GE | 0.001 | −0.013; 0.014 | F1.96 = 1.467; p = 0.229; η2 = 0.016 |

| GC | 0.155 | −0.006; 0.037 | ||

| Physical discomfort | GE | 0.006 | 0.007; −0.008 G | F1.97 = 0.044; p = 0.835; η2 = 0.001 |

| GC | 0.004 | −0.021; 0.029 | ||

| Score total | GE | 1.384 | −2.170; 3.378 G | F1.96 = 0.035; p = 0.852; η2 = 0.001 |

| GC | 1.091 | −3.889; 6.072 | ||

| MDS_UPDRS | ||||

| Part IA: Non-motor experiences of daily living | GE | 0.972 | −5.067; 7.012 G | F1.96 = 0.030; p = 0.863; η2 = 0.001 |

| GC | −0.156 | −13.990; 13.678 | ||

| Part IB: Non-motor experiences of daily living | GE | 3.730 | −1.543; 9.004 G | F1.96 = 0.381; p = 0.539; η2 = 0.004 |

| GC | 0.273 | −11.603; 12.085 | ||

| Part II: Motor experiences of daily living | GE | 5.164 | −1.886; 12.214 | F1.96 = 0.388; p = 0.035; η2 = 0.004 |

| GC | 1.394 | −9.010;11.799 | ||

| Part III: Motor evaluation | GE | 6.385 | 1.171; 11.600 G | F1.96 = 0.745; p = 0.390; η2 = 0.008 |

| GC | 1.723 | −9.478; 12.924 | ||

| Part IV: Motor complications | GE | 1.328 | 2.267; 4.923 | F1.96 = 5.589; p = 0.020; η2 = 0.06 |

| GC | 17.395 | 1.487; 33.304 | ||

| Total score | GE | 6.751 | −0.948; 14.450 M | F1.96 = 0.018; p = 0.894; η2 = 0.001 |

| GC | 7.922 | −11.227; 26.460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M. Immersive Virtual Reality High-Intensity Aerobic Training to Slow Parkinson’s Disease: The ReViPark Program. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114708

Rodríguez-Fuentes G, Campo-Prieto P, Cancela-Carral JM. Immersive Virtual Reality High-Intensity Aerobic Training to Slow Parkinson’s Disease: The ReViPark Program. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(11):4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114708

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Fuentes, Gustavo, Pablo Campo-Prieto, and José Ma Cancela-Carral. 2024. "Immersive Virtual Reality High-Intensity Aerobic Training to Slow Parkinson’s Disease: The ReViPark Program" Applied Sciences 14, no. 11: 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114708

APA StyleRodríguez-Fuentes, G., Campo-Prieto, P., & Cancela-Carral, J. M. (2024). Immersive Virtual Reality High-Intensity Aerobic Training to Slow Parkinson’s Disease: The ReViPark Program. Applied Sciences, 14(11), 4708. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114708