Abstract

This study analyzes the association and structural causality among work environment, work–family conflict, musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout in the food manufacturing industry. This study used the 6th Korean Working Environment Survey data, and 523 food production workers were selected as research subjects. Structural equation modeling showed that work environment and work–family conflict significantly affected musculoskeletal pain. In addition, work–family conflict and musculoskeletal pain affected sleep-related problems, and musculoskeletal pain and sleep-related problems impacted burnout. Furthermore, this research provides practical strategies to deal with musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related issues, and burnout. Burnout is more affected by sleep-related problems than by musculoskeletal pain. Additionally, sleep-related problems seem to be more affected by musculoskeletal pain than by work–family conflict. Meanwhile, musculoskeletal pain is influenced by the work environment rather than by work–family conflict. This result can be used to establish preventive policies for the safety and health of food manufacturing production workers.

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of Study

The food manufacturing industry is responsible for producing, processing, cooking, packaging, storing, transporting, and selling food [1]. This includes adding artificial ingredients to agricultural and marine products, as well as the transportation and sale of these products [2]. Food manufacturing is essential in public health beyond consumers [3]. Because the health of production workers in the food manufacturing industry affects productivity and product quality [4], protecting their physical and mental health is very important.

Since the food manufacturing industry involves maintaining food freshness and processing, it operates in environments with varying temperatures [5,6] and is exposed to noise and vibration [7]. In addition, it includes repetitive tasks in processing agricultural and marine products and handling heavy materials [6,8]. Poor working conditions can contribute to musculoskeletal pain among employees [6,7,8]. The food manufacturing industry is particularly known for a high prevalence of such complaints [9,10].

Korean food manufacturing workers are characterized by long working hours of more than 8 h [11,12], which can negatively impact sleep-related problems [13,14]. Additionally, working long hours can reduce the time available for spending with family, leading to work–family conflict [15,16]. In other words, the poor working environment [17] and long working hours experienced by food manufacturing workers can lead to conflicts between work and family life [18] and can also contribute to musculoskeletal pain and sleep-related problems [19,20,21]. Additionally, these factors are recognized as major contributors to burnout, which can significantly harm the health and quality of life of workers [22,23,24,25].

However, despite the association between burnout, work environment, work–family conflict, musculoskeletal pain, and sleep-related problems, there is a lack of research analyzing the causality of these relationships among food manufacturing workers. In this study, we aim to analyze the association and structural causality among work environment, work–family conflict, musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout using a structural equation model (SEM) targeting production workers in the food manufacturing industry.

1.2. Theoretical Background

1.2.1. Work Environment

The European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) and Korean Working Conditions Survey (KWCS) define the working environment as one that includes physical hazards such as vibration, noise, high and low temperatures, and biochemical hazards such as exposure to fumes and vapors. Additionally, it encompasses ergonomic hazards such as handling heavy loads and performing repetitive movements [17,26]. In the food manufacturing industry, frozen food workers are exposed to a low-temperature environment of −18 °C [5], and rice noodle manufacturing workers are exposed to a high-temperature environment of up to 36.68 °C [6]. Additionally, canning workers are exposed to noise levels of up to 100 dB [7], and meat and seafood processing workers are exposed to vibration due to vibrating equipment [7,27]. In addition, workers in poultry and seafood processing are exposed to lifting heavy objects and performing repetitive tasks [9,10].

1.2.2. Work–Family Conflict

Workers experience work–family conflict when they struggle to balance their responsibilities at work and at home [28,29]. In other words, work–family conflict means that conflict between roles occurs when the demands and expectations of work clash with the demands and expectations of family [28]. Work–family conflict appears in three forms [28]: time-based conflict, strain-based conflict, and behavior-based conflict. Working long hours at work can lead to conflicts between work and family life by reducing the time one can spend with family [15,16]. These conflicts can not only impact workplace productivity but also lead to psychological and mental health issues among workers [30].

1.2.3. Musculoskeletal Pain

Musculoskeletal disorders are conditions that result from the overuse of specific body parts due to repetitive and cumulative tasks or movements. These problems can affect nerves, muscles, ligaments, and joints and cause symptoms such as pain, abnormal sensations, and paresthesia [31,32]. The main factors contributing to musculoskeletal pain are primarily associated with ergonomic hazards in the workplace. However, exposure to physical, chemical, and biological hazards has also been found to be linked to the occurrence of pain [17,28,33]. Additionally, it is known that the level of musculoskeletal pain increases with higher levels of work–family conflict [34]. Therefore, the following hypotheses regarding musculoskeletal pain in food manufacturing workers were established.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

The work environment affects musculoskeletal pain.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Work–family conflict influences musculoskeletal pain.

1.2.4. Sleep-Related Problems

Sleep-related problems are disruptions in normal sleep patterns [35]. In general, these refer to poor sleep quality, such as difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep, waking up too early, or not recovering after sleep [36]. These sleep-related issues not only disrupt normal physical, mental, social, and emotional functioning but also impact overall health, safety, and quality of life [35]. Work environments, such as those with vibration, noise, and high and low temperatures, affect sleep-related problems [14]. Also, as work–family conflict becomes more severe, it can negatively impact sleep time and quality [37]. Additionally, with an increase in complaints of musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related issues may also increase [38,39]. Therefore, the following hypotheses were established regarding the sleep problems of food manufacturing workers.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

The work environment influences sleep-related problems.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Work–family conflict affects sleep-related problems.

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Musculoskeletal pain influences sleep-related problems.

1.2.5. Burnout

Burnout is a syndrome caused by unmanaged chronic work stress, characterized by emotional exhaustion, negative/cynical feelings toward the job, and a lack of personal achievement [40]. Emotional exhaustion refers to feeling emotionally drained by work, while cynicism refers to negative or callous reactions to individuals during work [41]. A lack of personal achievement leads to a decrease in one’s sense of competence and successful work achievement [41]. Burnout leads to a gradual decrease in a worker’s level of participation, causing a shift from enthusiasm to indifference [42]. Musculoskeletal pain, such as neck, shoulder, and ankle pain, has been shown to increase the risk of burnout [43], and the severity of sleep-related problems has been shown to increase the level of burnout [44]. Therefore, the following hypotheses were established regarding the burnout of food manufacturing workers.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Musculoskeletal pain affects burnout.

Hypothesis 7 (H7):

Sleep-related problems affect burnout.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Subjects

This study used the 6th Korean Working Environment Survey (KWCS) data [26]. Out of the data on a total of 50,538 workers surveyed in the 6th KWCS, data corresponding to the food manufacturing industry in the Korean Standard Industrial Classification [45] were extracted using a filter. In addition, according to the Korean Standard Classification of Occupations [46], production workers include technicians and related craft workers, equipment/machine operation and assembly workers, and simple labor workers.

A total of 523 food production workers were selected as research subjects, excluding the data of respondents with missing values. In terms of gender distribution, the respondents consisted of 214 men (40.9%) and 309 women (59.1%). The age distribution was as follows: 170 workers (32.5%) in their 40s or younger, 172 workers (32.9%) in their 50s, and 181 workers (34.6%) in their 60s or older.

2.2. Research Variables

Research variables for this study included the work environment, work–family conflict, musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout. The survey on the work environment assessed the question [17,26], ‘How many of your working hours do you spend in the following environments?’ Each item used a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7 points [17,26]. The work environment questions covered physical hazards (vibration, noise, high temperature, low temperature), biochemical hazards (exposure to fumes, vapors, chemicals, tobacco smoke, infectious materials), and ergonomic hazards (awkward posture, handling heavy loads, sitting posture, standing posture, and repetitive movements). Items measured on a 7-point scale were assessed using Kim et al.’s method to estimate exposure time to hazards [20]. The exposure level for each hazardous factor was categorized as less than 2 h, 2–4 h, and more than 4 h [47,48].

Work–family conflict was assessed using five measurement items (worry, fatigue, family issues, difficulty concentrating, and feeling overwhelmed with responsibilities) in response to the question [23,24], ‘How often have you experienced the following things in the past year?’ Each item was rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. A high score indicated severe work–family conflict.

Musculoskeletal pain was assessed by answering the question [17,26], ‘During the past year, have you had any health problems such as upper limb pain, lower limb pain, or back pain?’ with 1 being ‘yes’ and 2 being ‘no’.

The sleep-related problems were assessed using three measurement items: difficulty falling asleep, waking up repeatedly, and experiencing exhaustion/fatigue. Participants were asked to indicate how often they experienced these problems over the past year using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 [17,26]. A high score on the scale indicated more severe sleep-related problems.

The concept of burnout was assessed using two items (exhaustion and feeling drained) in response to the question [17,26], ‘How often do you feel the following emotions while working?’ Each item utilized a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. A higher score indicated a greater likelihood of experiencing burnout.

2.3. Reliability Analysis and Model Fit Test

Reliability analysis was performed using Cronbach’s alpha value to assess the internal consistency of the variables for work environment, work–family conflict, musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout in the KWCS raw data. The SEM was validated through model fit and convergent validity analysis.

Model fit was measured by the χ2, p-value, goodness-of-fit-index (GFI), root mean square residual (RMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), normed fit index (NFI), relative fit index (RFI), incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). The RMR [49,50,51] and RMSEA [51] were evaluated as good if less than 0.05 and acceptable if less than 0.08. The GFI [52], NFI [52,53], RFI [54], IFI [55], CFI [50,52,56], and TLI [52] were evaluated as highly suitable when above 0.9 and acceptable up to 0.85 [57].

The reliability of the SEM was analyzed using average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and correlation coefficients between variables. AVE was evaluated as appropriate when it was greater than 0.5 and CR was greater than 0.7 [58]. The statistical packages used for statistical analysis were SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 22.0.

2.4. Results of Reliability and Exploratory Factor Analysis

Table 1 shows the final results of the reliability analysis of subjective survey variables. After conducting a reliability analysis of work environment-related questions, 10 out of 15 questions were eliminated. The final selection consisted of 5 questions addressing vibration, noise, high temperature, low temperature, and handling of heavy objects. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.738.

Table 1.

Final reliability analysis results using Cronbach’s alpha.

For work–family conflict, the ‘worry’ item was excluded, and the Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.847. In musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout, there were no excluded items, and the Cronbach’s alpha values were above 0.7.

The final results of the reliability and factor analyses of the subjective survey questions are presented in Table 2. According to factor analysis using Varimax rotation, the subjective questionnaire items were grouped into five factors: (1) work–family conflict, (2) work environment, (3) sleep-related problems, (4) musculoskeletal pain, and (5) burnout. Bartlett’s test was statistically significant (p < 0.001), and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test also yielded a significant result (0.765 > criteria = 0.60).

Table 2.

Final results of reliability and factor analysis.

2.5. Structural Equation Model

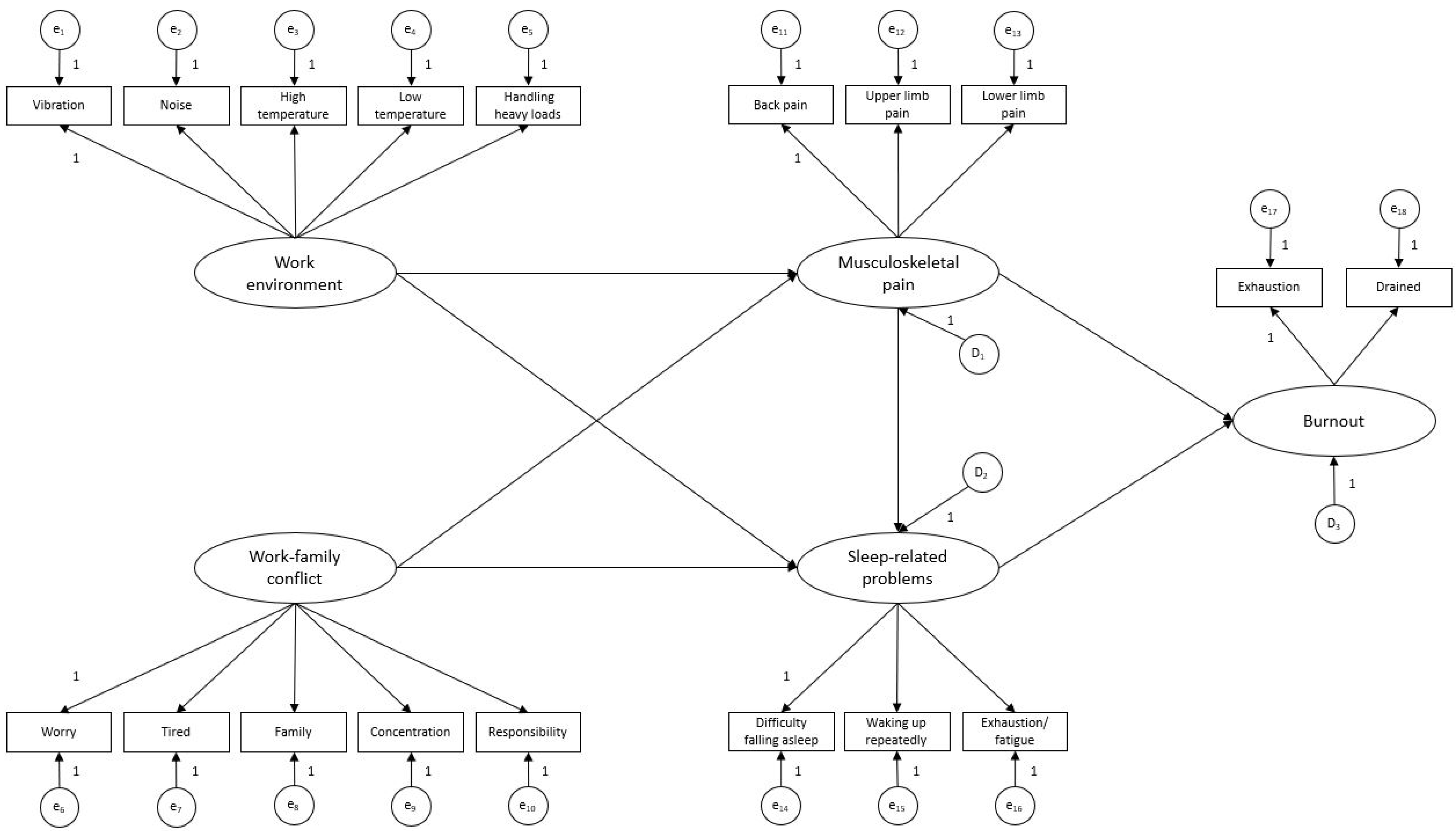

Figure 1 illustrates the research model based on the established hypotheses. This study uses an SEM to analyze the causal relationships between work environment, work–family conflict, musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout among food manufacturing production workers. That is, this study explores the effects of the work environment (H1) and work–family conflict (H2) on musculoskeletal pain in food manufacturing production workers. Furthermore, it investigates the influence of work environment (H3), work–family conflict (H4), and musculoskeletal pain (H5) on sleep-related problems. Lastly, the study aims to determine the relationship between musculoskeletal pain (H6) and sleep-related problems (H7) and their impact on burnout.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structural equation model of this study. Rectangle, measurement variable; ellipse, latent variable; Di, disturbance or residual; ei, measurement error.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Model Fit Test and Validity Analysis

The model fit test results showed that χ2 = 342.516, p < 0.001, RMR = 0.063, RMSEA = 0.061, GFI = 0.929, NFI = 0.914, RFI = 0.895, IFI = 0.940, CFI = 0.926, and TLI = 0.940. These values indicate that the model fit was adequate.

Table 3 presents the results of the validity analysis and the correlations between latent variables. The validity was confirmed by testing for both convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was confirmed by using AVE and CR values. In Table 4, the AVE value exceeds 0.5, and the CR value surpasses 0.7, demonstrating proven convergent validity. The discriminant validity was confirmed by assessing the relationship between the AVE values and the correlation coefficients. The AVE values exceeded the square value of the correlation coefficients, and the conditions for discrimination using the correlation coefficient and sampling error were also met.

Table 3.

Results of validity analysis and correlations with variables.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis testing of proposed relationships.

3.2. Results of Hypothesis Testing

Table 4 shows the results of the testing for the study’s hypotheses. Table 4 indicates that the work environment impacts musculoskeletal pain (p = 0.002) but does not significantly affect sleep-related problems (p = 0.061). Work–family conflict was found to impact musculoskeletal pain (p = 0.011) and sleep-related problems (p < 0.001). Additionally, musculoskeletal pain has a significant effect on sleep-related problems (p < 0.001) and burnout (p = 0.006). Furthermore, sleep-related problems have a significant impact on burnout (p < 0.001).

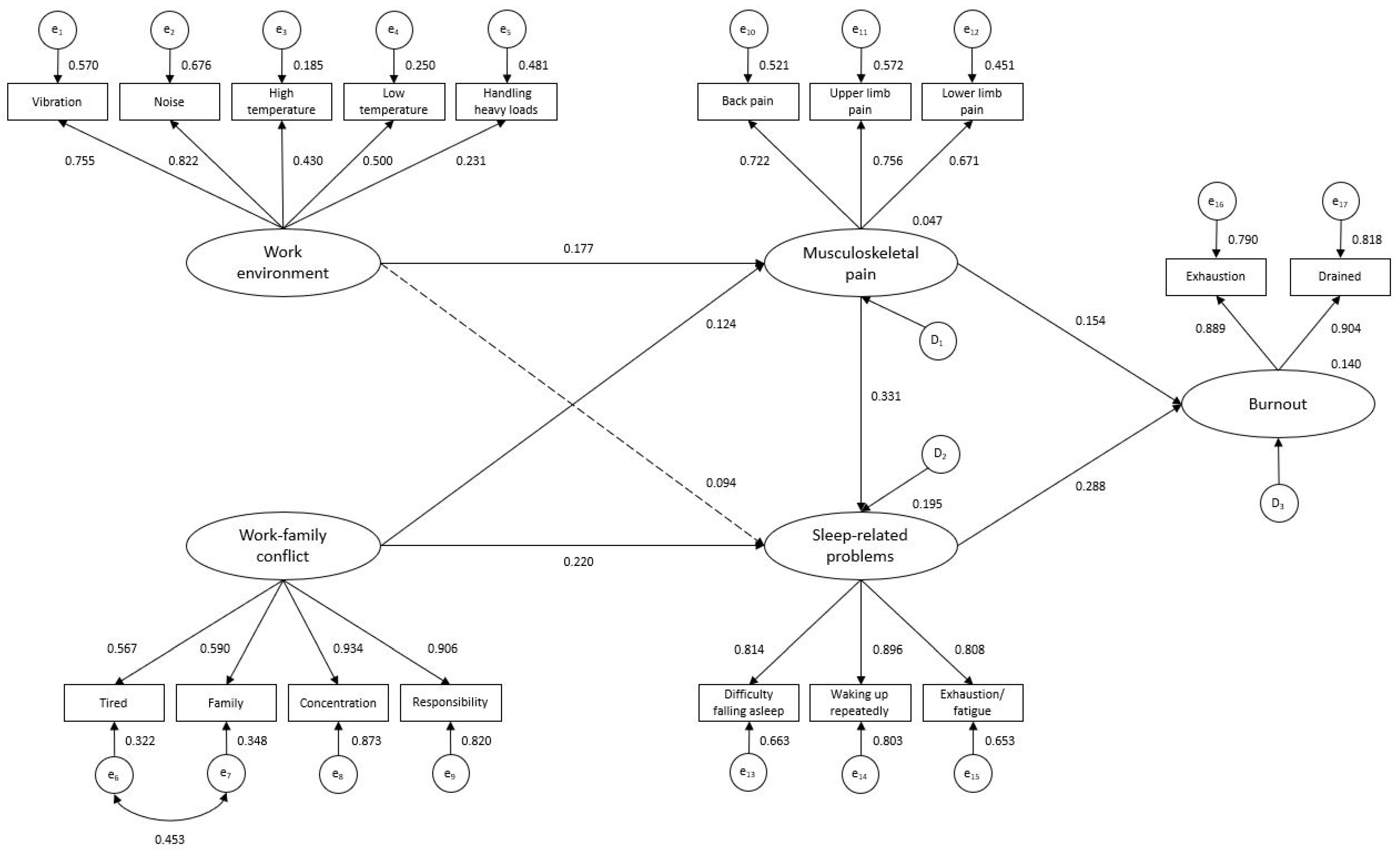

3.3. Final SEM

Figure 2 depicts the finalized model based on the results of the hypothesis test. Work environment has been shown to have an effect on musculoskeletal pain (standardized path coefficient (β) = 0.177). This means that the worse the work environment, the more it affects musculoskeletal pain. Work–family conflict has a β of 0.124, indicating that increased work–family conflict is associated with higher levels of musculoskeletal pain. Meanwhile, musculoskeletal pain is more influenced by the work environment than by work–family conflict.

Figure 2.

Final structural equation model of this study. Rectangle represents measurement variable, and ellipse represents latent variable. Di: disturbance or residual; ei: measurement error.

Work–family conflict affects sleep-related problems (β = 0.220). It can be inferred that as work–family conflict becomes more serious, sleep-related problems also become more severe. Musculoskeletal pain also appeared to have an impact on sleep-related problems (β = 0.331). As musculoskeletal pain worsens, sleep-related problems also become more severe. Also, sleep-related problems appeared to be more affected by musculoskeletal pain than by work–family conflict. On the other hand, the work environment did not appear to have an effect on sleep-related problems.

Musculoskeletal pain affects burnout (β = 0.154). Thus, as musculoskeletal pain becomes more severe, it affects burnout. Sleep-related issues have a significant impact on burnout, with a β of 0.288. This indicates that as sleep-related problems worsen, their effect on burnout intensifies. In particular, burnout appeared to be more impacted by sleep-related problems than by musculoskeletal pain.

As for work environment variables, ‘noise’ (0.822) and ‘vibration’ (0.755) were found to have a significant influence, and work–family conflict was found to have a substantial impact on ‘concentration’ (0.934) and ‘responsibility’ (0.906). Musculoskeletal pain showed a close relationship with ‘upper limb pain’ (0.756) and ‘back pain’ (0.722), and sleep-related problems were highly influential with ‘waking up constantly’ (0.896) and ‘difficulty falling asleep’ (0.814). Lastly, the burnout variables ‘drained‘ (0.904)’ (0.904) and ‘exhaustion’ (0.889) were found to have a significant influence.

Work environment variables were found to be closely related to ‘noise’ (0.822) and ‘vibration’ (0.755), and work–family conflict was found to be closely related to ‘concentration’ (0.934) and ‘responsibility’. (0.906). Musculoskeletal pain showed a close relationship with ‘upper limb pain’ (0.756) and ‘back pain’ (0.722), and sleep-related problems were closely related to ‘waking up repeatedly’ (0.896) and ‘difficulty falling asleep’ (0.814). Lastly, the burnout variable was found to be closely related to ‘drained’ (0.904) and ‘exhaustion’ (0.889).

4. Discussion

In this study, the working conditions in the food manufacturing industry were found to have an impact on musculoskeletal pain. This was consistent with the results that automobile manufacturing, construction, and nursing workers have also complained of musculoskeletal pain due to work environments with conditions such as noise, vibration, and low temperature [20,21,34]. The impact of the work environment is not specific to the food manufacturing industry but rather a common characteristic across all industries. This indicates that improvements to the work environment are necessary to prevent workers from experiencing musculoskeletal pain. The study also revealed that work–family conflict affects musculoskeletal pain. This finding aligns with the fact that work–family conflict significantly contributes to lower back and neck pain [36]. In addition, the results were consistent with the finding that work–family conflict is a risk factor for neck and back pain in workers of the service and production sectors and nurses [35,59]. Therefore, it is essential to prevent work–family conflict in order to reduce musculoskeletal pain among food manufacturing workers.

Sleep-related problems among food manufacturing workers were influenced by work–family conflict and musculoskeletal pain but not by the work environment. This was in line with the finding that nurses’ sleep quality worsened as work–family conflict increased [60] and that sleep-related problems in construction industry workers and IT workers were also affected by work–family conflict [61,62]. In addition, several previous studies have shown that higher levels of work–family conflict are associated with an increased risk of sleep-related problems such as waking up multiple times at night, difficulty falling asleep again, and waking up tired [63,64,65]. Chronic back pain can cause sleep-related issues, such as decreased sleep quality and a longer time to fall asleep [66]. Additionally, more severe neck and shoulder pain leads to worse sleep quality [67].

Musculoskeletal pain and sleep-related problems were found to affect food manufacturing workers’ burnout. This finding aligns with a study indicating that the intensity of neck, shoulder, and wrist pain is associated with an increased likelihood of burnout among doctors and nurses [68], as well as with another study suggesting a connection between neck and shoulder pain and burnout in healthcare workers [69]. Moreover, findings indicated that sleep quality plays a crucial role in burnout [70]. According to research, doctors were four times more likely to experience burnout if they reported sleep-related issues [71], and nurses were similarly affected by burnout when they reported sleep-related problems [72]. This study is significant, as it revealed that musculoskeletal pain and sleep problems impact burnout among food manufacturing workers, similar to medical workers. Efforts are necessary to address musculoskeletal pain and sleep-related issues among food manufacturing production workers to prevent burnout since occupational burnout has a negative impact on workers’ well-being and physical and mental health [73].

This study offers practical strategies for food manufacturing employees to address musculoskeletal pain, sleep-related problems, and burnout. First, workers in food manufacturing production are experiencing burnout influenced by sleep-related problems and musculoskeletal pain. Of the two factors, sleep-related problems were found to have a more significant impact. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the management of workers who are dealing with sleep-related problems. In particular, it suggests that management is required to address the issues of ‘frequent waking up’ and ‘difficulty falling asleep’ among production workers in the food manufacturing industry.

Second, sleep-related problems in food manufacturing production workers are affected by musculoskeletal pain and work–family conflict. Among these factors, musculoskeletal pain seems to have a greater impact. Thus, this suggests that managing workers who complain of musculoskeletal pain is paramount. In particular, it suggests that the management of food manufacturing production workers’ ‘upper limb pain’ and ‘back pain’ is necessary.

Third, the presence of musculoskeletal pain was influenced by the work environment, and work–family conflict and was found to be more influenced by the work environment between the two factors. Therefore, this suggests that managing the work environment is of the utmost importance. In particular, in the case of food manufacturing, it suggests that management is necessary in the following order: ‘noise’, ‘vibration’, ‘low temperature’, ‘high temperature’, and ‘handling heavy loads’.

This study has some limitations, so further research is necessary. First, this study is limited by using variables such as sleep-related problems, musculoskeletal pain, and burnout, which were taken from the publicly available KWCS survey. For instance, burnout was limited to only two survey items. Therefore, future research using objective and quantitative scales related to these factors could improve measurement accuracy. Second, this study did not consider factors such as job satisfaction, social support at work, and coping strategies, which can significantly impact workers’ mental health concerning burnout. Future research requires an integrated model that includes these factors. Furthermore, while the results of this study indicate that musculoskeletal pain could contribute to burnout, another study has suggested that burnout might be a significant factor in musculoskeletal pain [74]. Therefore, caution is required in identifying the correlation between musculoskeletal pain and burnout, as interpretations may differ depending on the researcher. Third, this study targets production workers in the Korean food manufacturing industry and requires caution when generalizing because the occupation has long working hours, diverse working conditions, and a high proportion of workers in their 50s or older. In addition, this study is a cross-sectional study targeting production workers in the food manufacturing industry, and future research is required on how longitudinal research on cases where characteristics such as occupation, age, and working time distribution change will affect the research results. Fourth, different research models that take into account research limitations may produce varying results about the causal relationships between different structures. These results are used to suggest customized measures to improve social and psychological factors within specific professions and groups. This approach can also have a more significant impact on the well-being of workers in labor-intensive settings.

5. Conclusions

This study found that sleep-related problems among food manufacturing production workers are closely related to burnout and musculoskeletal pain and that musculoskeletal pain is related to the work environment and work–family conflict. In addition, the study is significant because it establishes a causal relationship between these factors and recommends their integrated management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.K. and B.Y.J.; methodology, J.W.K. and B.Y.J.; data collection and analysis, J.W.K.; resources, J.W.K. and B.Y.J.; data curation, J.W.K. and B.Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.K. and B.Y.J.; writing—review and editing, J.W.K. and B.Y.J.; supervision, B.Y.J.; funding acquisition, B.Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Hansung University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://www.kosha.or.kr/eoshri/resources/KWCSDownload.do (accessed on 21 August 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (OSHRI) and the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA) for providing the raw data from the KWCS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Framework Act on Agriculture Rural Community and Food Industry. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=food+indust&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor4 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Enforcement Ordinance of the Framework Act on Agricultural Rural Community and Food Industry. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?menuId=1&subMenuId=15&query=%EB%86%8D%EC%97%85%C2%B7%EB%86%8D%EC%B4%8C%20%EB%B0%8F%20%EC%8B%9D%ED%92%88%EC%82%B0%EC%97%85%20%EA%B8%B0%EB%B3%B8%EB%B2%95&dt=20201211#undefined (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Yach, D.; Khan, M.; Bradley, D.; Hargrove, R.; Kehoe, S.; Mensah, G. The role and challenges of the food industry in addressing chronic disease. Glob. Health 2010, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuro, P.; Gadzirayi, C.T.; Taruwona, M.; Mupararano, S. Impact of occupational health and safety on worker productivity: A case of Zimbabwe food industry. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2644–2651. [Google Scholar]

- Thetkathuek, A.; Yingratanasuk, T.; Jaidee, W.; Ekburanawat, W. Cold exposure and health effects among frozen food processing workers in eastern Thailand. Saf. Health Work 2015, 6, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, M.; Ye, M.; Choy, K.; Ho, S.F. Heat stress in rice vermicelli manufacturing factories. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2018, 24, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: Food Industry. Available online: https://www.iloencyclopaedia.org/part-x-96841/food-industry (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Musolin, K.; Ramsey, J.G.; Wassell, J.T.; Hard, D.L. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome among employees at a poultry processing plant. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Jeong, B.Y.; Park, J.Y. A Study on the Risk Factors of Infection and Musculoskeletal Disorders in Food Manufacturing Workers: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2023, 42, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyanto, J. Control of the risk of musculoskeletal disorders in the food industry: Systematic review. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 4254–4261. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Labor Standards Act. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=Labor+Standards+Act&x=24&y=28#liBgcolor2 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. Report on the Survey of Work Status by Employment Type in 2022. Available online: http://laborstat.moel.go.kr/lsm/bbs/selectBbsList.do?bbsYn=Y?answerSn=0&bbsId=LSS108&bbsSn=0&leftMenuId=0010001100116&menuId=0010001100116115&pageIndex=1&searchCtgryCode=004&subCtgryCode=004 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Mokarami, H.; Gharibi, V.; Kalteh, H.O.; Kujerdi, M.F.; Kazemi, R. Multiple environmental and psychosocial work risk factors and sleep disturbances. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.S.; Kang, M.Y. Association between Occupational Exposure to Chemical or Physical Factors and Sleep Disturbance: An Analysis of the Fifth Korean Working Conditions Survey. Sleep Health 2022, 8, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, C.L.; Premeaux, S.F. Spending time: The impact of hours worked on work—Family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiRenzo, M.S.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Weer, C.H. Job level, demands, and resources as antecedents of work—Family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 78, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey—Overview Report. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2016/sixth-european-working-conditions-survey-overview-report (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Kang, D. Relationship between of working hours, weekend work, and shift work and work-family conflicts among Korean manufacturers. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 34, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.R.; Lowden, A.; Vasconcelos, S.; Marqueze, E.C. Musculoskeletal pain and insomnia among workers with different occupations and working hours. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Jeong, B.Y.; Park, M.H. A study on the factors influencing overall fatigue and musculoskeletal pains in automobile manufacturing production workers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Jeong, B.Y.; Park, M.H. Exposure to Occupational Hazards and Musculoskeletal Pains in the Construction Workers. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2023, 42, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, G.J.; Nashed, A.; Manzini, C.; Carra, M.C. Does sleep differ among patients with common musculoskeletal pain disorders? Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2011, 13, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, A.S.; Abd El-Maksoud, M.M. Relationship between musculoskeletal disorders, job demands, and burnout among emergency nurses. Adv. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2012, 34, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, M.; Jeding, K.; Ekstedt, M.; Perski, A.; Åkerstedt, T. Insufficient sleep predicts clinical burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranđelović, M.; Ilić, I.; Jović, S. Burnout and the quality of life of workers in food industry: A pilot study in Serbia. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2010, 67, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute. Korean Working Conditions Survey. Available online: https://www.kosha.or.kr/eoshri/resources/KWCSDownload.do (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Syron, L.N.; Lucas, D.L.; Bovbjerg, V.E.; Case, S.; Kincl, L. Occupational traumatic injuries among offshore seafood processors in Alaska, 2010–2015. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 66, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoek, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 470. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E.L.; Moen, P.; Tranby, E. Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.M.; Cho, S.I. Work—Life imbalance and musculoskeletal disorders among South Korean workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runge, N.; Ahmed, I.; Saueressig, T.; Perea, J.; Labie, C.; Mairesse, O.; Nijs, J.; Malfliet, A.; Verschueren, S.; Van Assche, D.; et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep problems and chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain 2022, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, B.Y. Ergonomics’ role for preventing musculoskeletal disorders. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2010, 29, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.J.; Jeong, B.Y. Exposure Time to Work-Related Hazards and Factors Affecting Musculoskeletal Pain in Nurses. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weale, V.; Oakman, J.; Clays, E. Does work—Family conflict play a role in the relationship between work-related hazards and musculoskeletal pain? Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. Sleep Disorder. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560720/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Thorpy, M.J. Classification of sleep disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Liu, S.Y.; Hammer, L.; Moen, P.; Klein, L.C.; Kelly, E.; Fay, M.; Davis, K.; Durham, M.; Karuntzos, G.; et al. Work—Family conflict, cardiometabolic risk, and sleep duration in nursing employees. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinstrup, J.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Calatayud, J.; Jay, K.; Andersen, L.L. Association of stress and musculoskeletal pain with poor sleep: Cross-sectional study among 3600 hospital workers. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 419504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, S.; Mienna, C.S.; Wahlström, J.; Englund, E.; Wiesinger, B. Work ability and productivity among dentists: Associations with musculoskeletal pain, stress, and sleep. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Marín, J. El síndrome de burnout y sus diferentes manifestaciones clínicas: Una propuesta para la intervención. Anest. Analg. Reanim. 2016, 29, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H.; Lin, J.J.; Yang, C.W.; Tang, H.M.; Jong, G.P.; Yang, T.Y. The effect of commuting time on burnout: The mediation effect of musculoskeletal pain. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trockel, M.T.; Menon, N.K.; Rowe, S.G.; Stewart, M.T.; Smith, R.; Lu, M.; Kim, P.K.; Quinn, M.A.; Lawrence, E.; Marchalik, D.; et al. Assessment of physician sleep and wellness, burnout, and clinically significant medical errors. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2028111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Korea. Korean Standard Industrial Classification. Available online: https://kssc.kostat.go.kr:8443/ksscNew_web/ekssc/main/main.do (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Statistics Korea. Korean Standard Classification of Occupations. Available online: https://kssc.kostat.go.kr:8443/ksscNew_web/ekssc/main/main.do# (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hazard Zone Checklist. 2021. Available online: https://lni.wa.gov/safety-health/_docs/HazardZoneChecklist.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Caution Zone Checklist. 2021. Available online: https://lni.wa.gov/safety-health/_docs/CautionZoneJobsChecklist.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS, 1st ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1998; p. 432. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 454. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Sample size and Bentler and Bonett’s nonnormed fit index. Psychometrika 1986, 51, 375–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.S.; Jeong, B.Y. Relationship between negative work situation, work-family conflict, sleep-related problems, and job dissatisfaction in the truck drivers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, H.; Grebner, S.; Blasimann, A.; Hirschmüller, A.; Kubosch, E.J.; Elfering, A. Work—Family conflict and neck and back pain in surgical nurses. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2018, 24, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, B.E.S.; Ghaith, R.F.A.H.; Ahmed, H.A.A. Relationship between work—Family conflict, sleep quality, and depressive symptoms among mental health nurses. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Govender, R.; Edwards, P.; Cattell, K. Work-related contact, work—Family conflict, psychological distress and sleep problems experienced by construction professionals: An integrated explanatory model. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 36, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, O.M.; Lee, S.; Beverly, C.; Berkman, L.F.; Moen, P.; Kelly, E.L.; Hammer, L.B.; Almeida, D.M. Work-family conflict and employee sleep: Evidence from IT workers in the Work, Family and Health Study. Sleep 2016, 39, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazami, S.; Mozafari, M.; Shamsuddin, K.; Akmal, S. Work-family conflict and sleep disturbance: The Malaysian working women study. Ind. Health 2016, 54, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallukka, T.; Rahkonen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Arber, S. Sleep complaints in middle-aged women and men: The contribution of working conditions and work—Family conflicts. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 19, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshak, E.S. Work-to-family conflict rather than family-to-work conflict is more strongly associated with sleep disorders in Upper Egypt. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.A.; Blake, C.; Power, C.K.; O’keeffe, D.; Fullen, B.M. The association between chronic low back pain and sleep: A systematic review. Clin. J. Pain 2011, 27, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Oh, J. The relationship between sleep quality, neck pain, shoulder pain and disability, physical activity, and health perception among middle-aged women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valim, M.D.; de Sousa, R.M.; da Silva Santos, B.; Alvim, A.L.S.; da Costa Carbogim, F.; de Paula, V.A.A.; Pimenta, F.G.; dos Santos, A.G., Jr.; Batista, O.M.A.; de Oliveira, L.B.; et al. Occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders, burnout, and psychological suffering in Brazilian nursing workers: A cross-sectional study. Belitung Nurs. J. 2024, 10, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Yeh, C.J.; Lee, C.M.; Jong, G.P. Mediation Effect of Musculoskeletal Pain on Burnout: Sex-Related Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothe, N.; Schulze, J.; Kirschbaum, C.; Buske-Kirschbaum, A.; Penz, M.; Wekenborg, M.K.; Walther, A. Sleep disturbances in major depressive and burnout syndrome: A longitudinal analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 286, 112868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, M.D.; Robbins, R.; Quan, S.F.; O’Brien, C.S.; Viyaran, N.C.; Czeisler, C.A.; Barger, L.K. Association of sleep disorders with physician burnout. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2023256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młynarska, A.; Bronder, M.; Kolarczyk, E.; Manulik, S.; Młynarski, R. Determinants of sleep disorders and occupational burnout among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; Andrade, S.M.D. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armon, G.; Melamed, S.; Shirom, A.; Shapira, I. Elevated burnout predicts the onset of musculoskeletal pain among apparently healthy employees. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).