Numerical Simulation Study of Rotating Structure for Large Tonnage Asymmetric T-Shaped Rigid Swiveling Bridge

Abstract

:1. Introduction

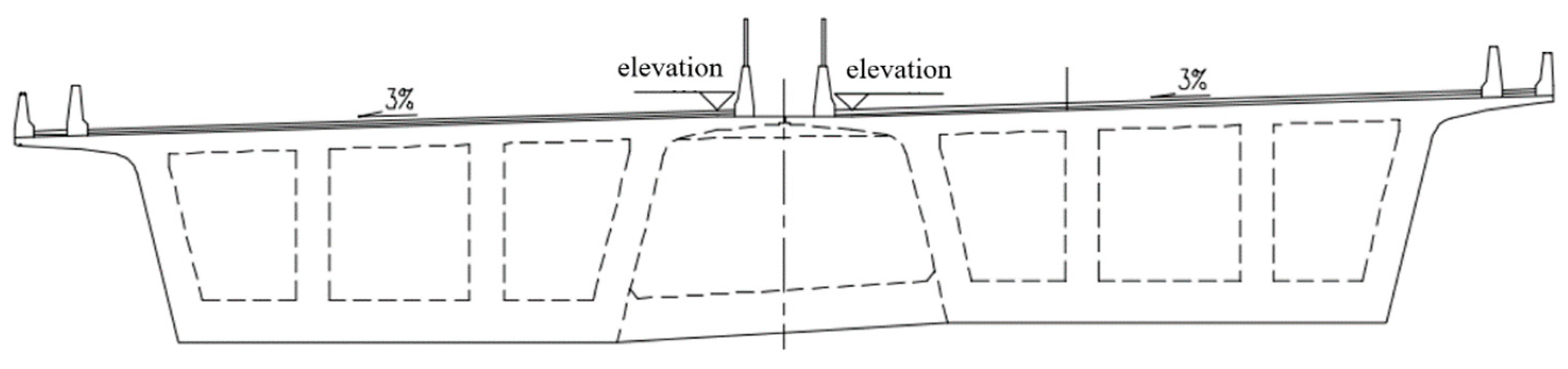

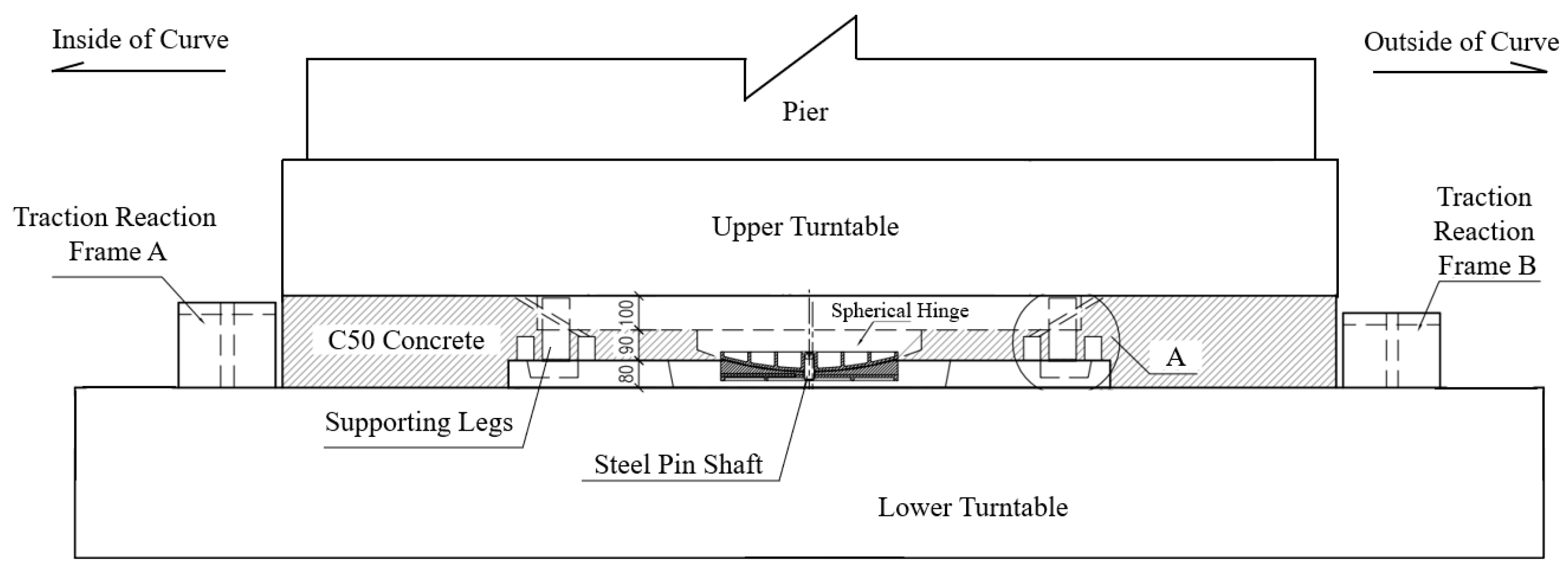

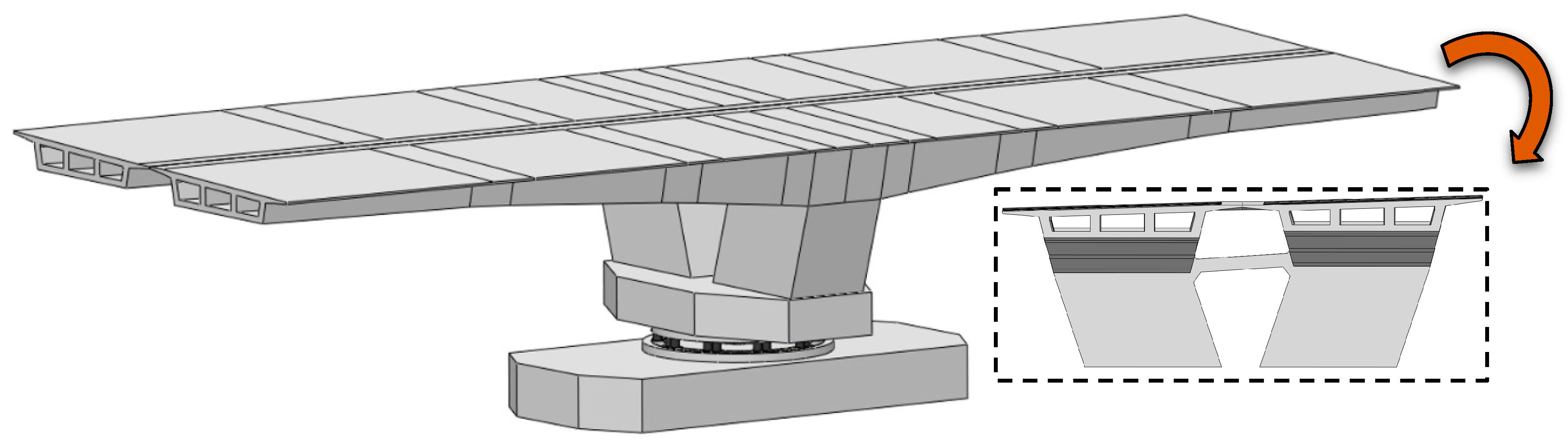

2. Finite Element Numerical Simulation

2.1. Model Building

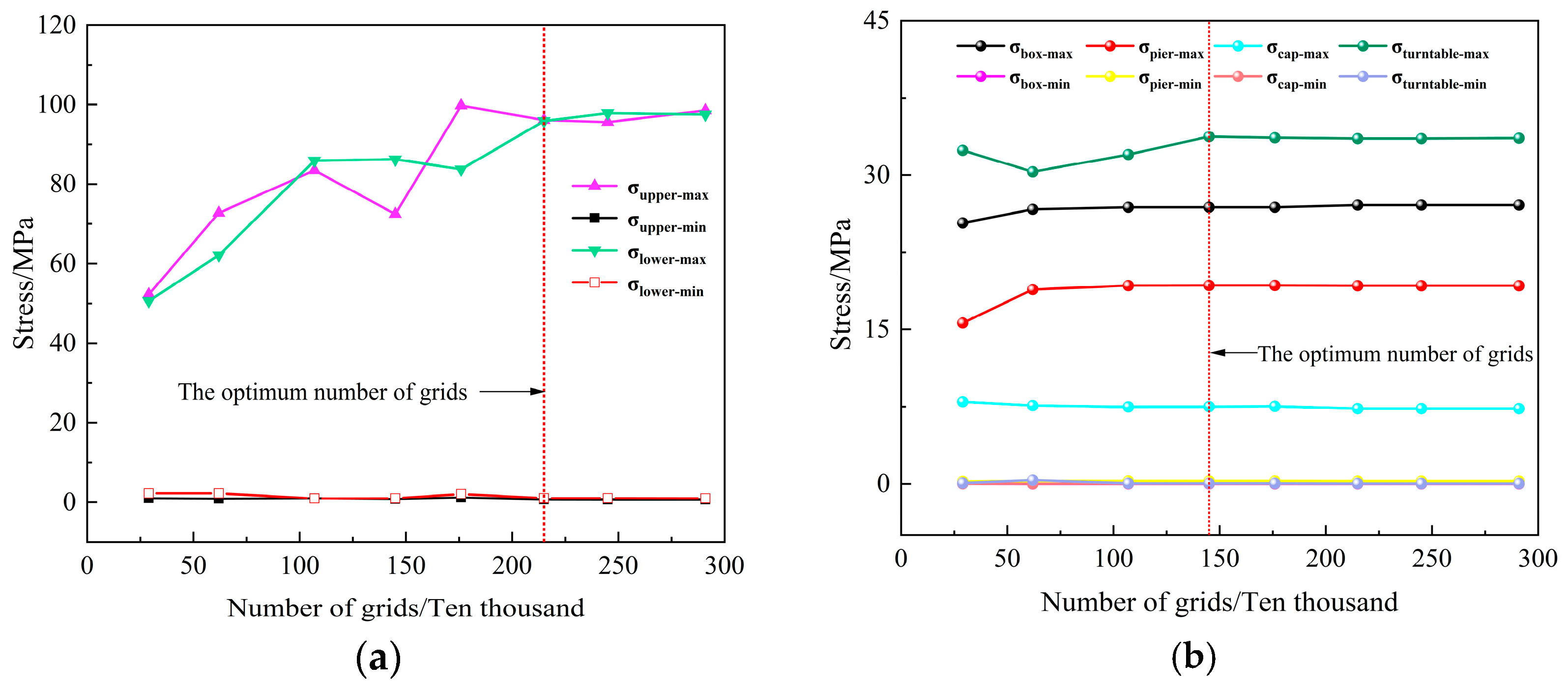

2.2. Material Properties and Grid Delineation

2.3. Analysis of Calculation Results

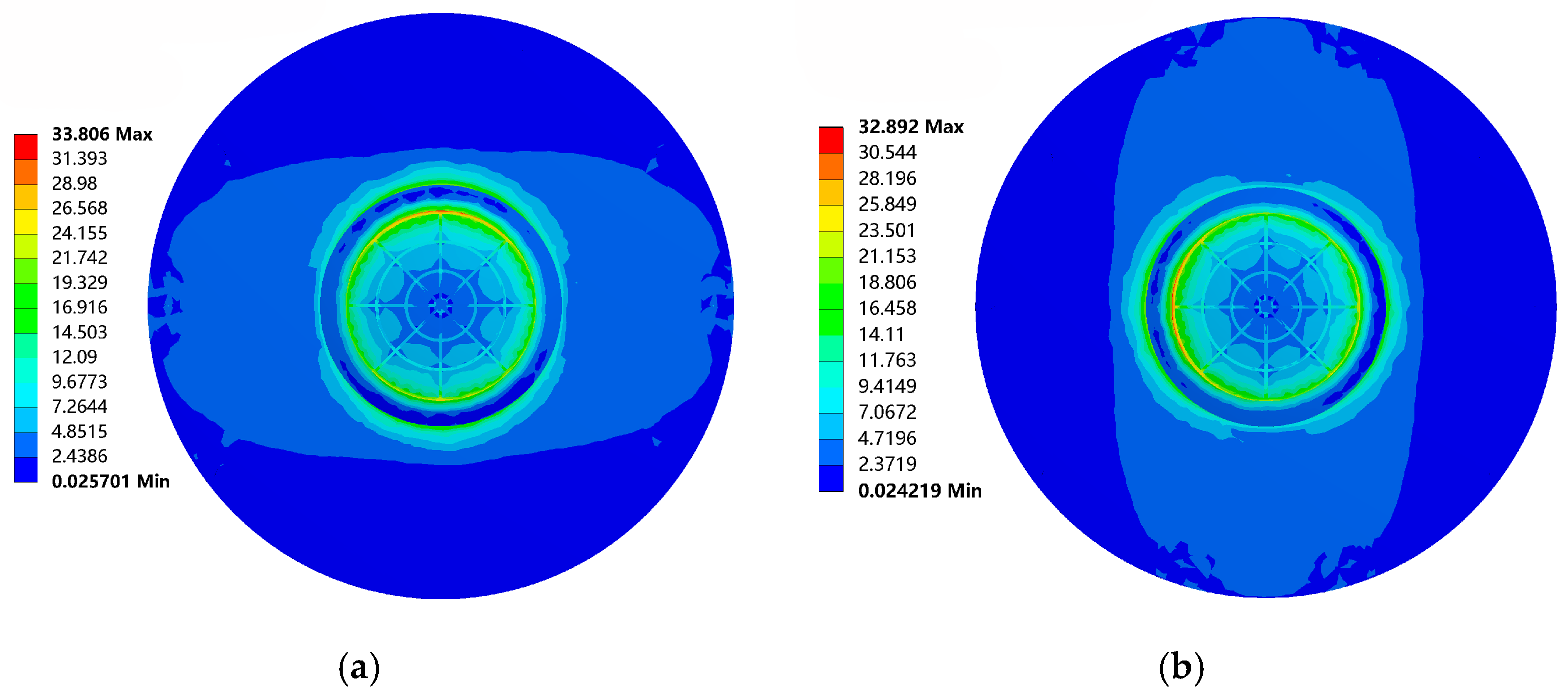

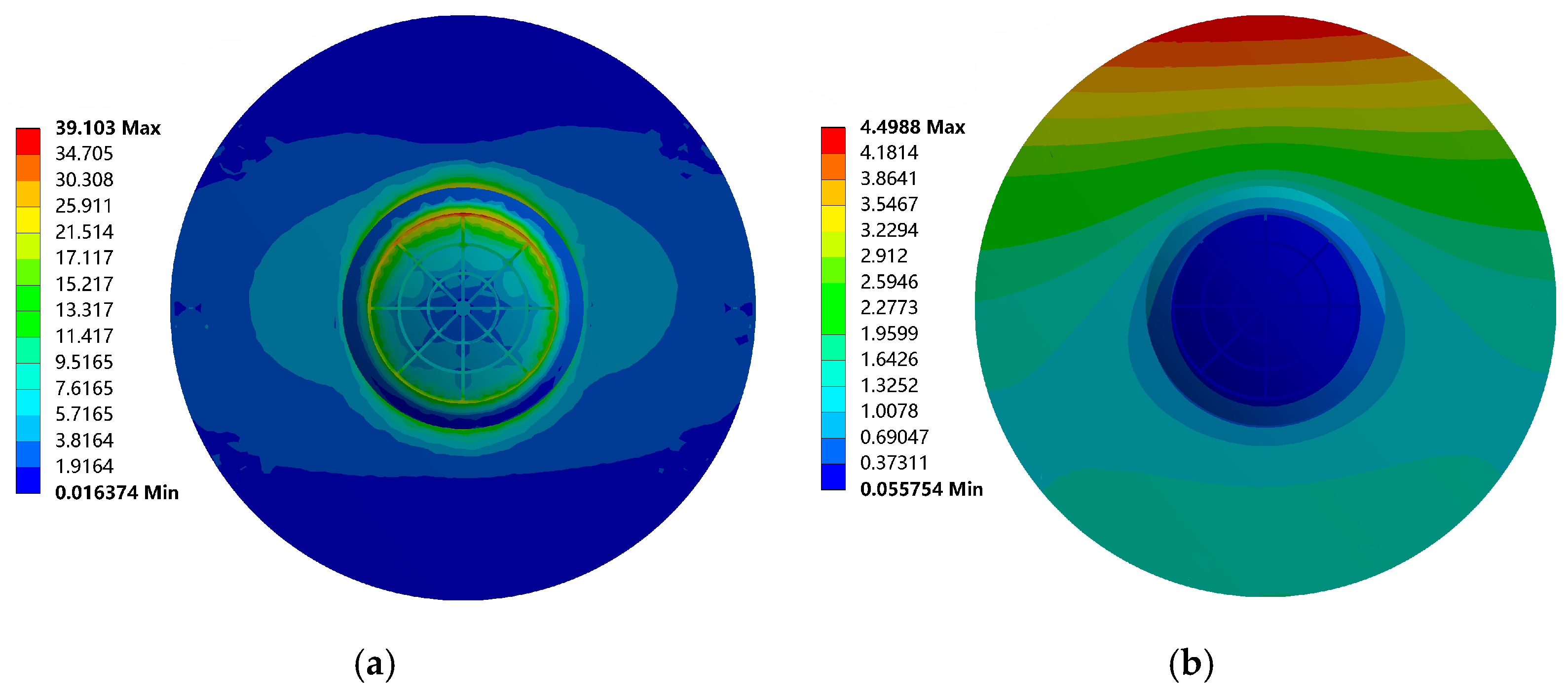

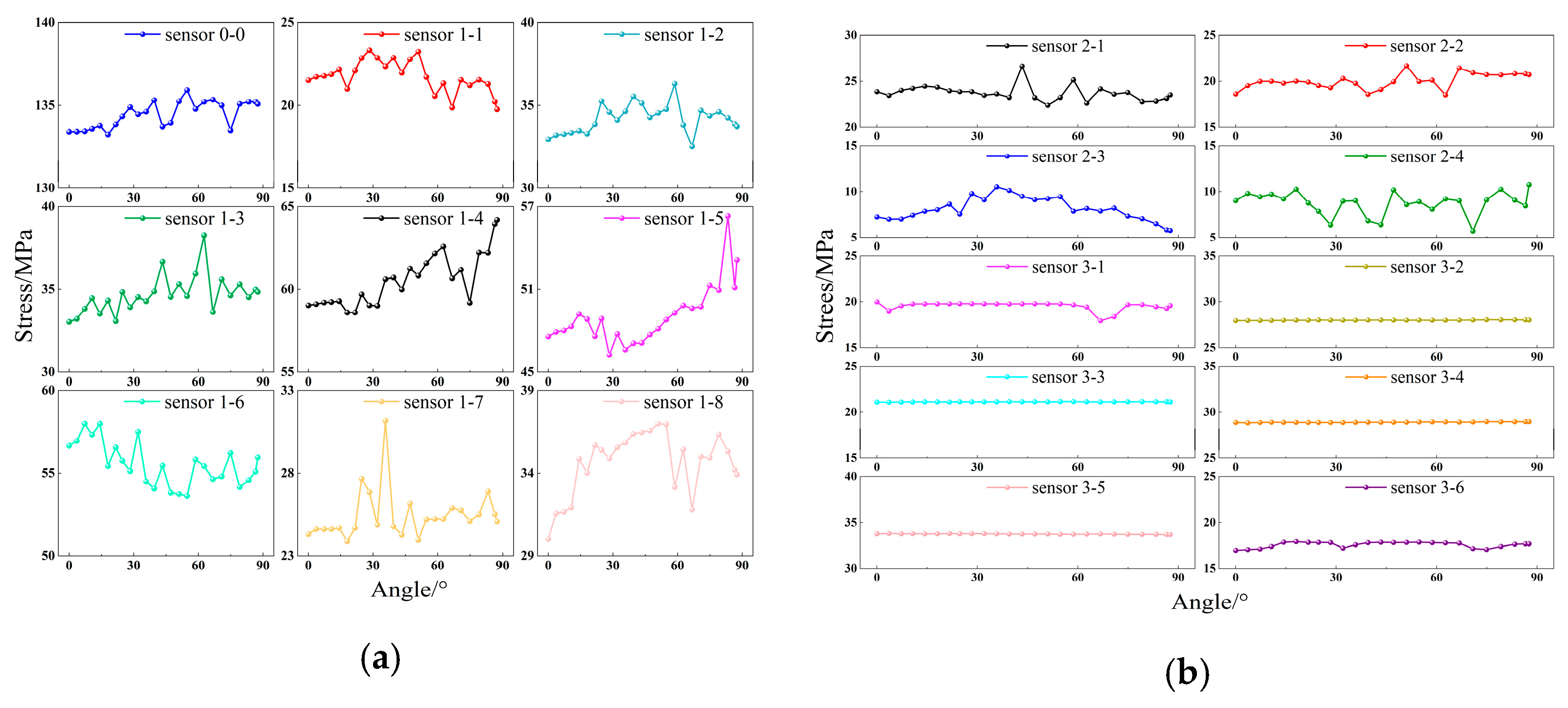

2.3.1. Different Rotation Angles

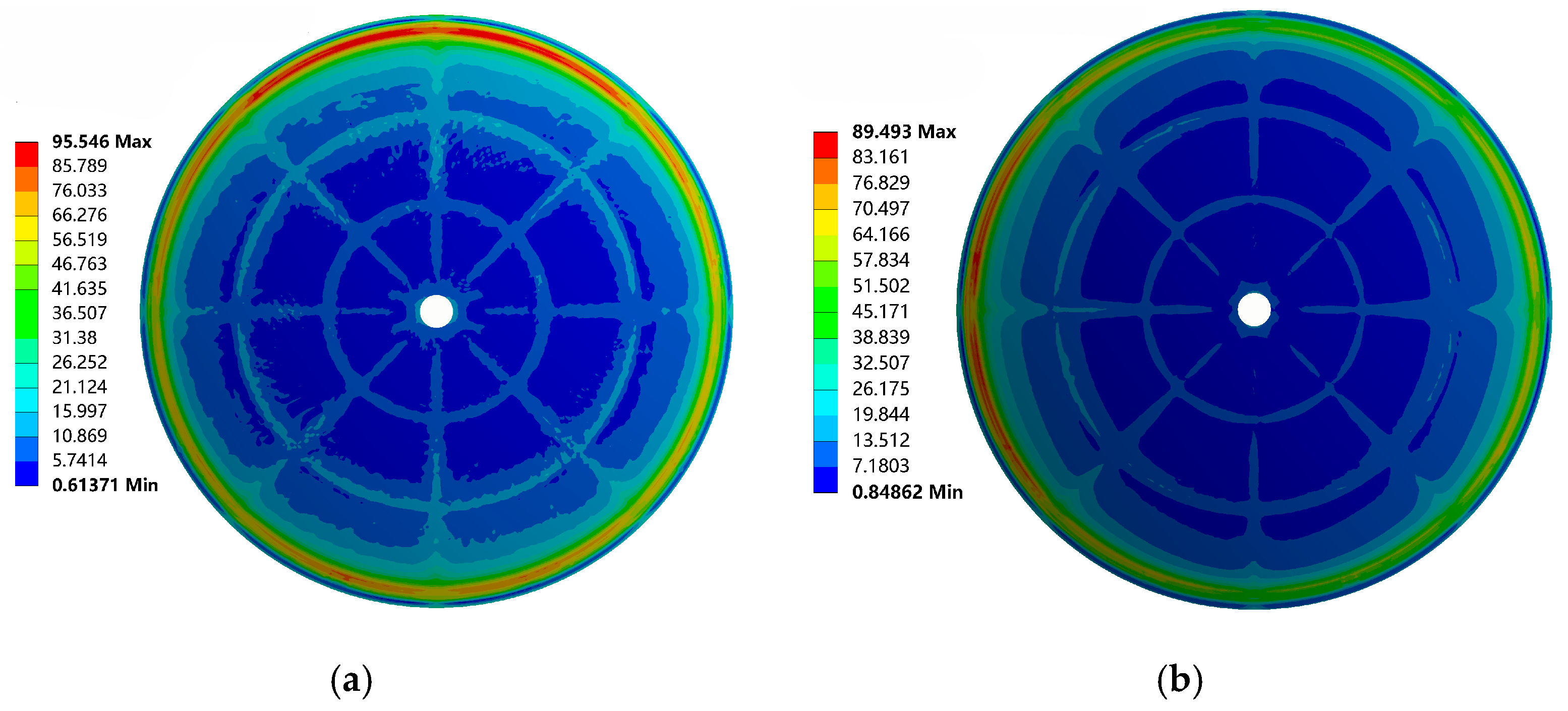

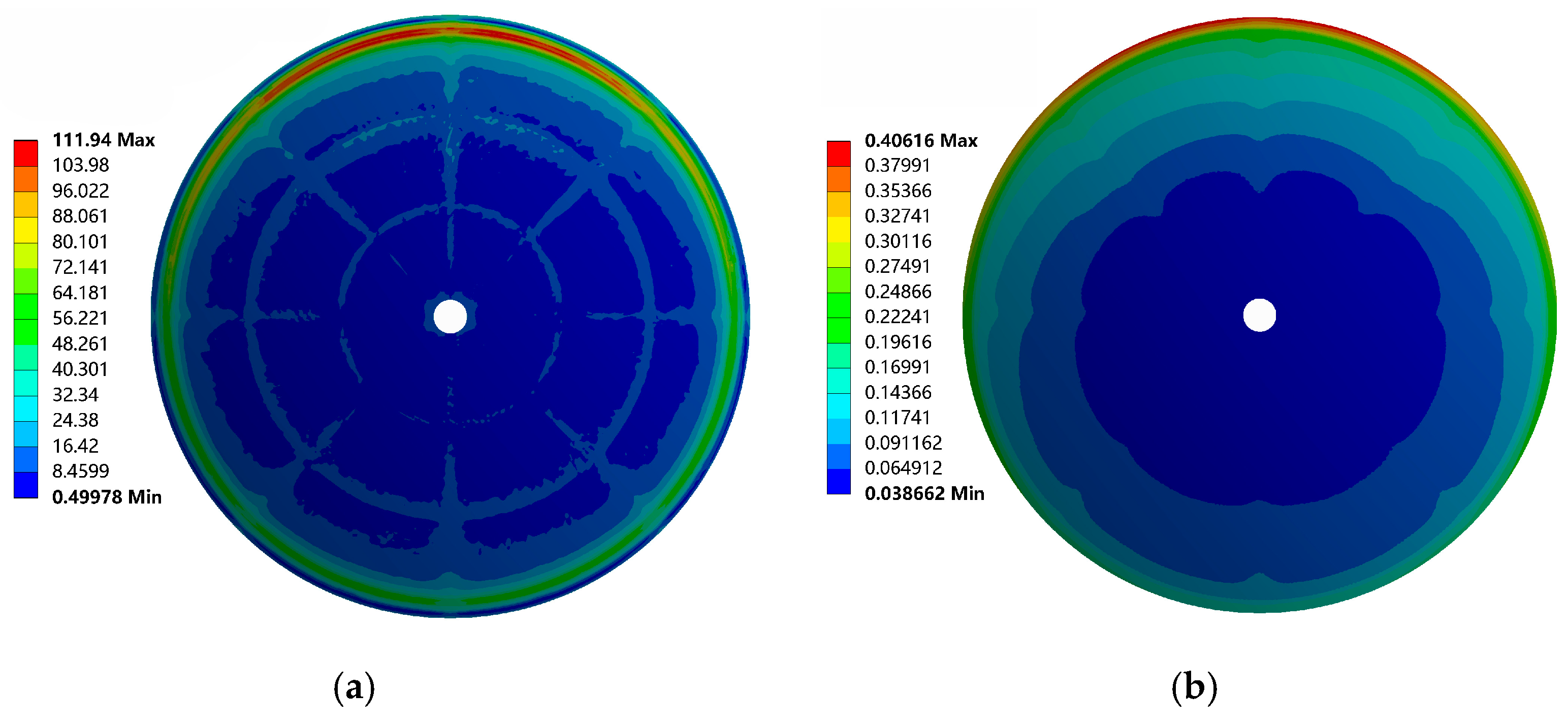

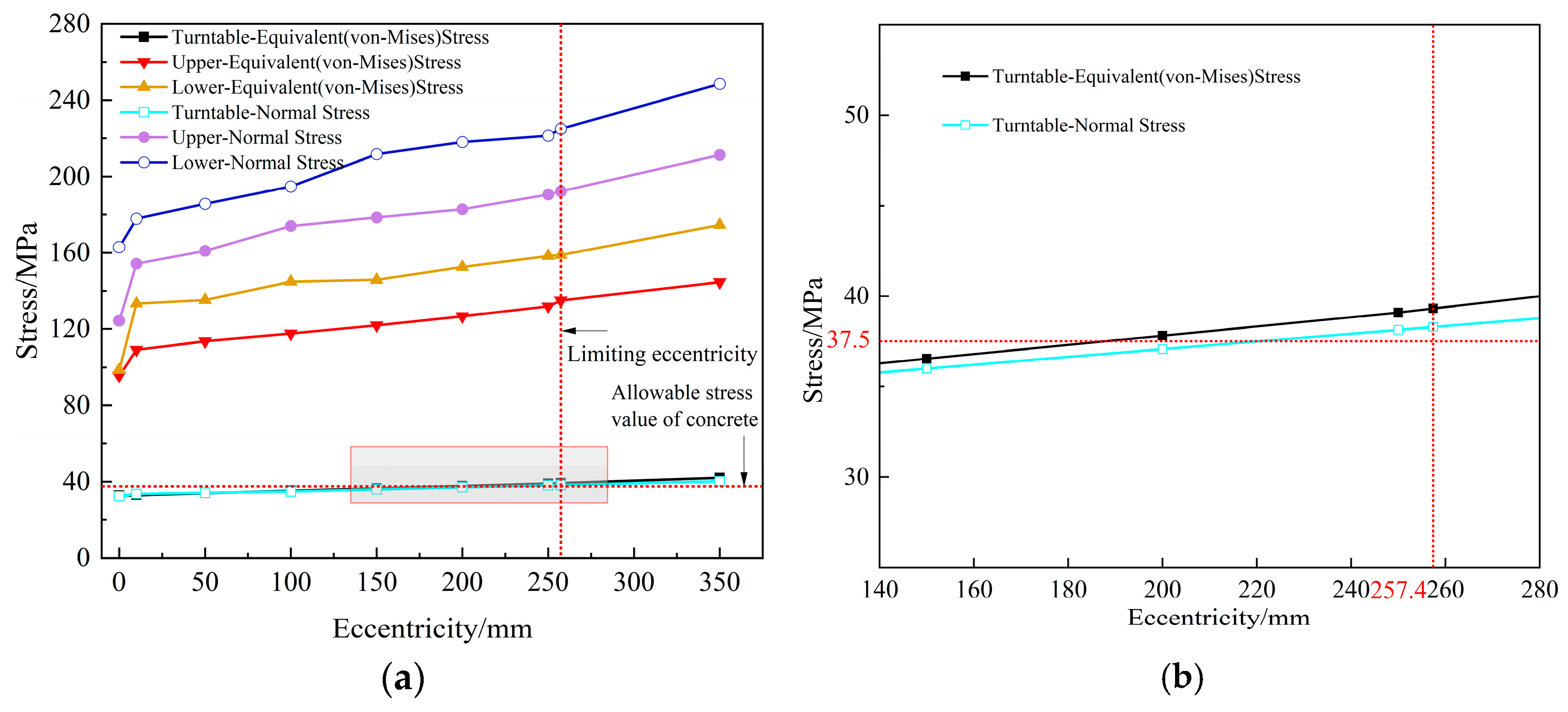

2.3.2. Transverse Axial Bias Loads

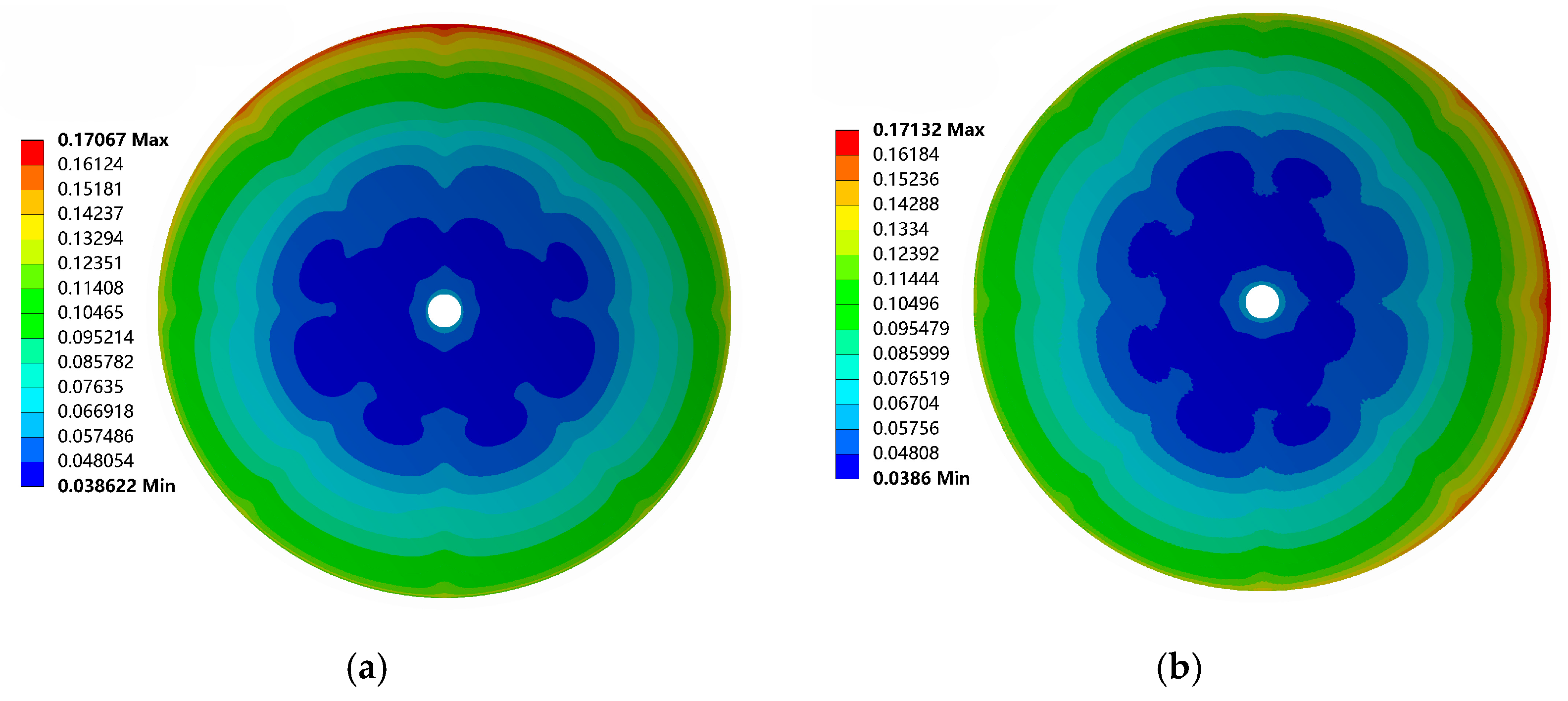

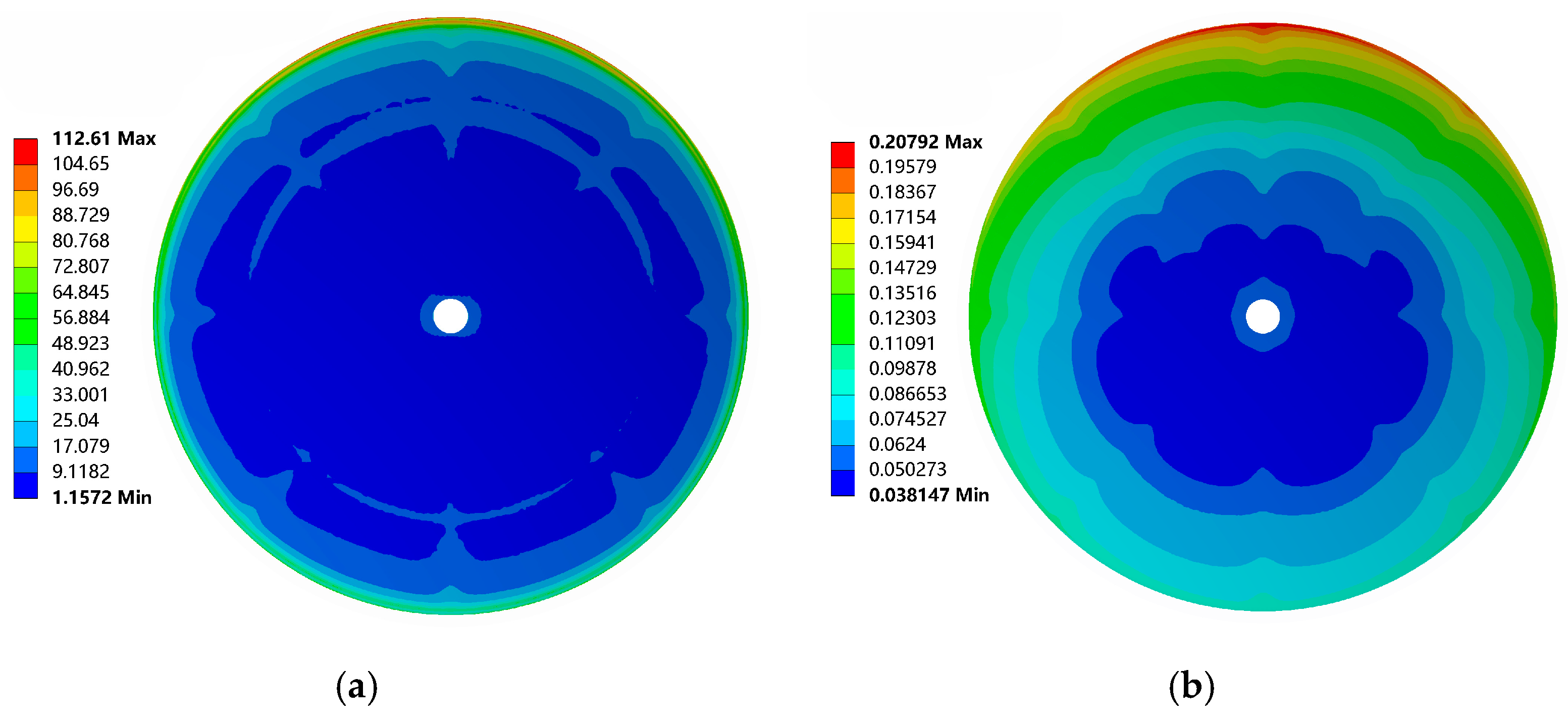

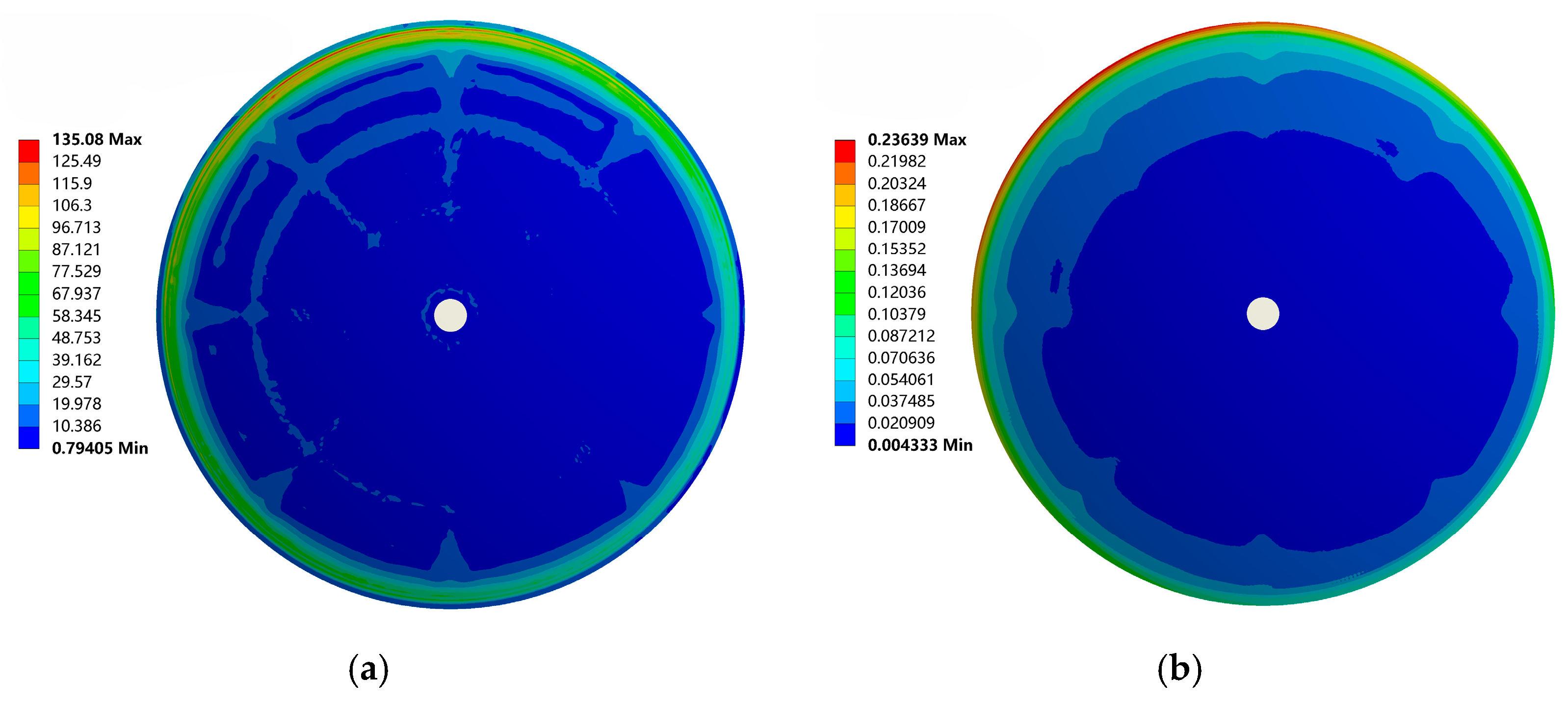

2.3.3. Longitudinal Axial Bias Loads

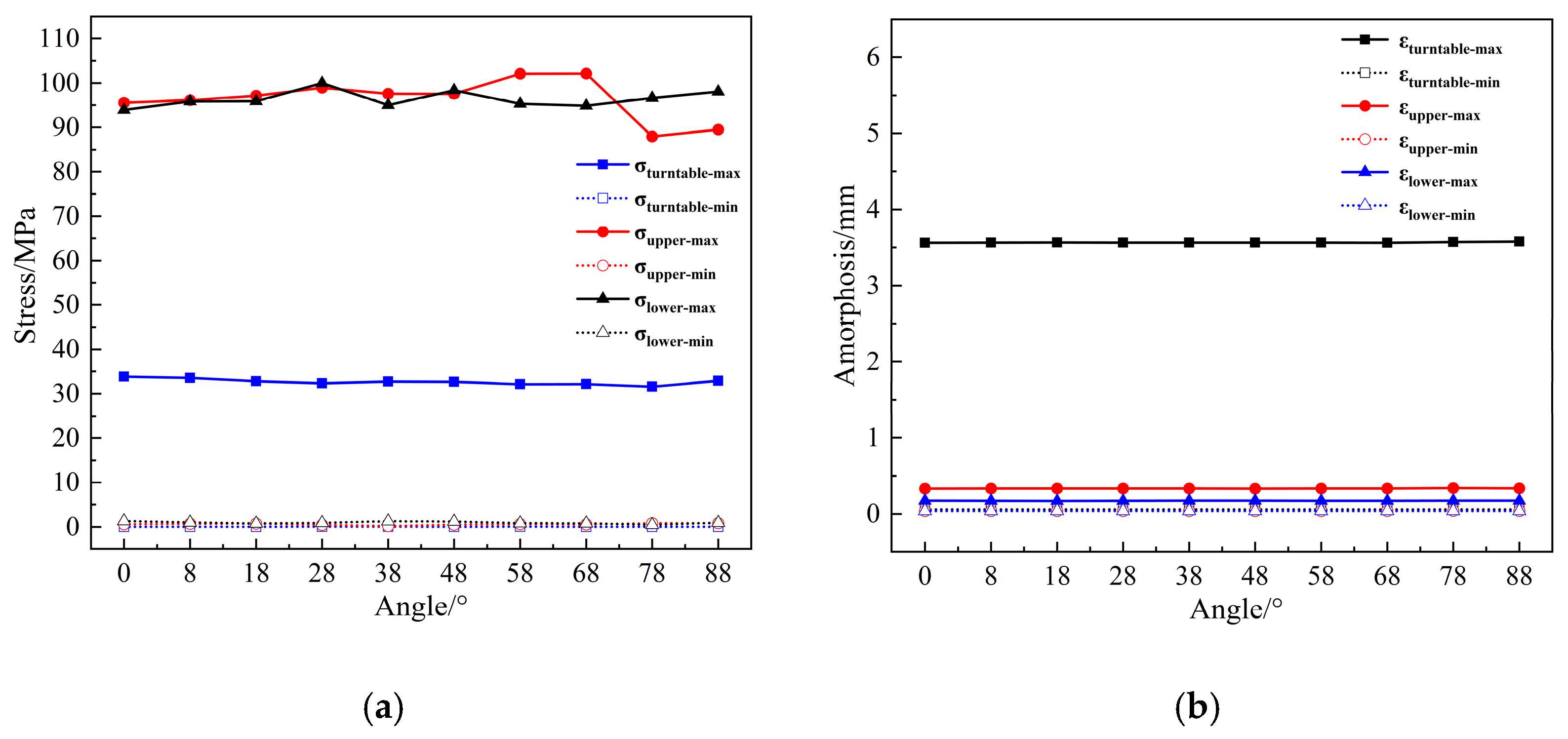

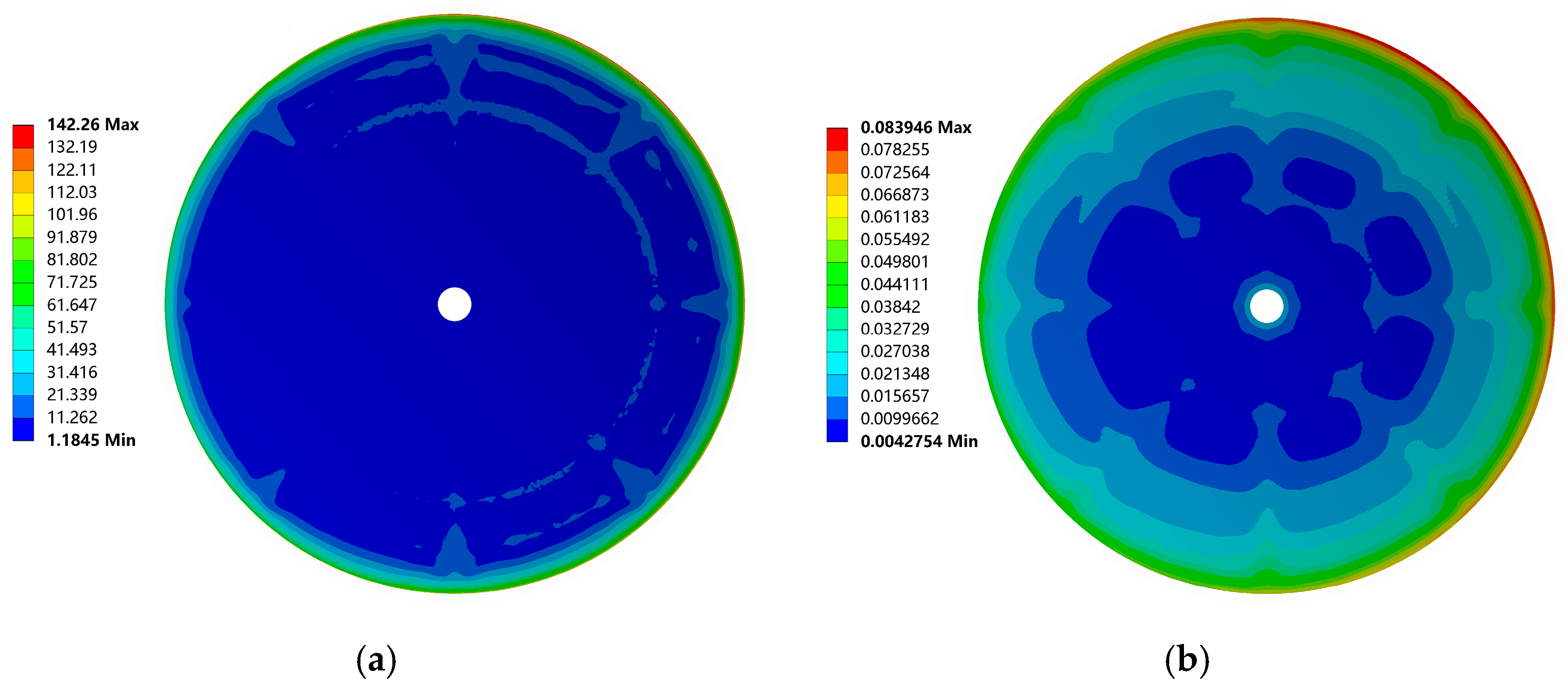

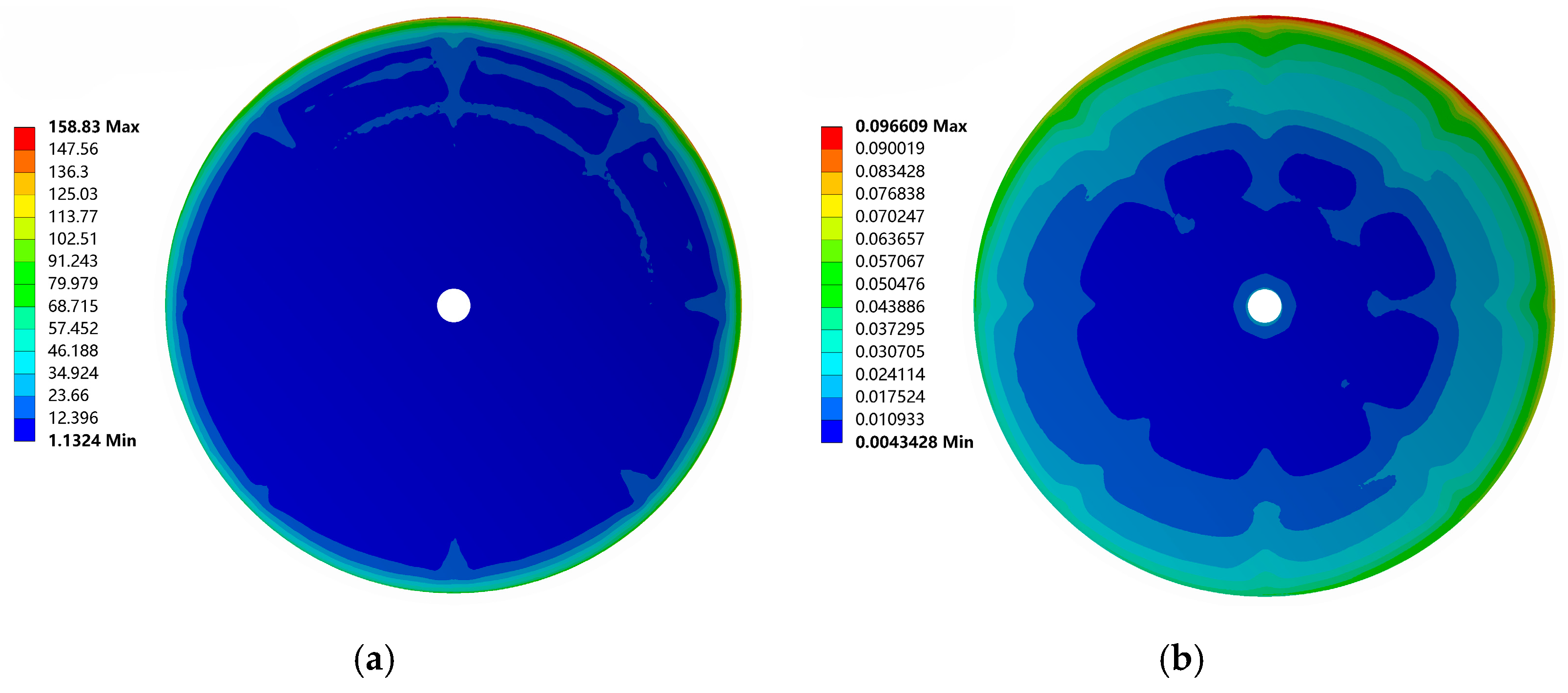

2.3.4. Longitudinal and Transverse Axial Bias Loads

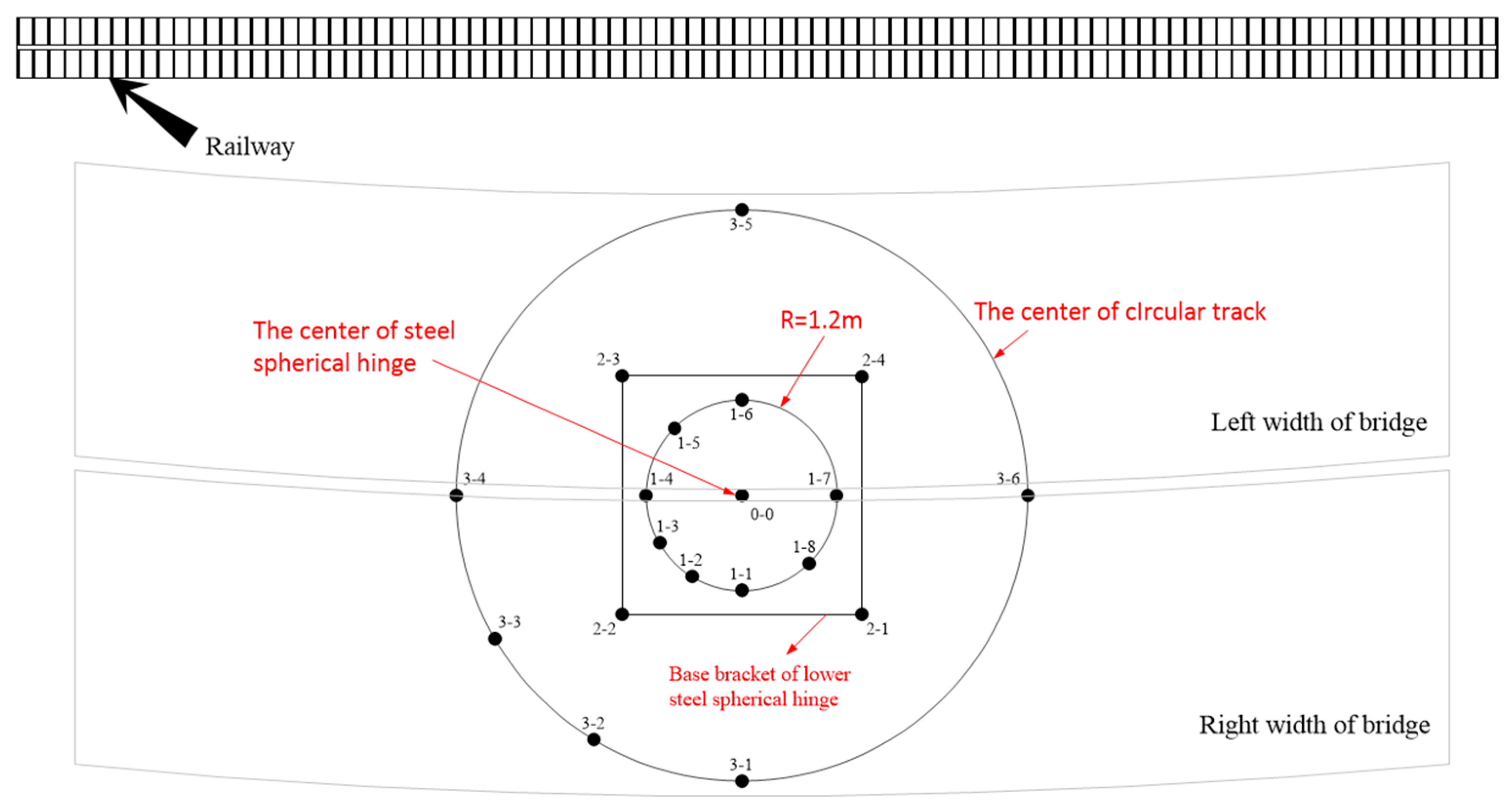

3. Monitoring Program and Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, X. Thoughts on the Development of Bridge Technology in China. Engineering 2019, 5, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Wang, J.; Peng, H. State-of-the-art review of the development and application of bridge rotation construction methods in China. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 64, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; He, Q.; Meng, X. Bridge monitoring using multi-GNSS observations with high cutoff elevations: A case study. Measurement 2021, 168, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Hardie, M. A critical analysis of safety performance indicators in construction. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2020, 39, 547–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.; Fukada, S. Nondestructive damage detection in deteriorated girders using changes in nodal displacement. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2017, 7, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorruso, C.; Quaglini, V. Conceptual Design of Seismic Retrofit of Existing Bridges by Deck Isolation: Assessment of Effectiveness. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Q. Parameter sensitivity analysis of stability of T-shaped rigid frame bridge by adopting swivel construction method. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 2020, 16, 1203–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, R.; Ha, T.; Fukada, S. Analytical study on damage detection method using displacement influence lines of road bridge slab. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2019, 9, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Siyuan, R.; Ming, L. Design and development of a two degree-of-freedom rotational flexure mechanism for precise unbalance measurements. J. Mech. Robot. 2017, 9, 041013. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Duan, M.; Yang, W. Research on the critical technique of synchronous rotation construction with large angle for T-shape curve rigid frame bridge. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Zuo, J.; Liu, D. Tribological Properties and Seasonal Freezing Damage Evolution of Rotating Spherical Hinge Self-Lubricating Coating. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. Accurate calculation method of vertical friction moment of spherical hinge in bridge rotation construction. Railw. Eng. 2020, 60, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vilventhan, A.; Rajadurai, R. 4D Bridge Information Modelling for management of bridge projects: A case study from India. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 10, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni-Anibire, M.; Mohamad, Z.; Olatunji, S.O. Causes of delay in the global construction industry: A meta analytical review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 22, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z. Investigation on Moisture Damage Prevention of a Spherical Hinge Structure of a Swivel Bridge. Coatings 2020, 10, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, D.; Behnam, B.; Sebt, M. BIM-Based Safety Leading Indicators Measurement Tool for Construction Sites. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 21, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciegaj, A. A Diagnostic Method Based on Deflection Analysis for Monitoring Post-elastic Response of Beams. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 21, 839–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidou, S.; Paraskevopoulos, E. Seismic fragility analysis of railway reinforced concrete bridges considering real-time vehicle-bridge interaction with the aid of co-simulation techniques. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 51, 2137–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhang, X. Overturning resistance of large tonnage T-shaped rigid frame bridge during turning process. China J. High. Transp. 2014, 27, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Yang, C. Refined finite element modeling of a damaged bridge with virtual distortion method coupling solid super element. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 93, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parson, S. Investigation on determining thermal stress in massive concrete structures. ACI 1996, 93, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Lee, H. Analysis of target configurations under dead loads for cable- supported bridges. Comput. Struct. 2001, 79, 2681–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhou, Q.; Guan, L. Research on optimization of radial stress calculation method for large tonnage ball hinge of rotary bridge. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (TSE) 2014, 38, 356–358. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Research on Ball Hinge Analysis and Control of Bridge Construction by Flat Rotating Method. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Railway Sciences, Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Stress analysis and optimization method of contact surface of bridge rotating body construction. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2020, 41, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Yu, Q.; Fan, J. Concrete spherical joint contact stress distribution and overturning moment of swing bridge. Structures 2020, 28, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Research on Key Technology of Super-Large Tonnage T Rotations. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, R.; Hallowell, M. Predictive validity of safety leading indicators: Empirical assessment in the oil and gas sector. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y. Optimization of Swivel Spherical Hinge Structure Design Based on the Response Surface Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z. Bridge safety monitoring and evaluation based on hesitant fuzzy set. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 1183–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Joo, H.; Choi, S. Experimental Study on Shear Capacity of Reinforced Concrete Beams with Corroded Longitudinal Reinforcement. Materials 2019, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Experimental research on compressive strength of UHPC spherical hinge. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2019, 11, 354–378. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, P.; Carvalho, H.; Ribeiro, D. Assessment of train running safety on bridges: A literature review. Eng. Struct. 2021, 241, 112425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Materials | Poisson’s Ratio | Young’s Modulus/MPa | Friction Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper steel spherical hinge | Q235 | 0.3 | 2.10 × 105 | 0.06 |

| Lower steel spherical hinge | Q235 | 0.3 | 2.10 × 105 | 0.06 |

| Supporting legs | Q355B | 0.3 | 2.06 × 105 | 0.06 |

| Pier | C40 | 0.2 | 3.25 × 104 | - |

| Upper turntable | C50 | 0.2 | 3.45 × 104 | - |

| Lower turntable | C50 | 0.2 | 3.45 × 104 | - |

| Roof cap | C50 | 0.2 | 3.45 × 104 | - |

| Bridge | C55 | 0.2 | 3.55 × 104 | - |

| Lower cap | C55 | 0.2 | 3.55 × 104 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, E.; Wu, Y.; Guo, S.; Li, P.; Li, H. Numerical Simulation Study of Rotating Structure for Large Tonnage Asymmetric T-Shaped Rigid Swiveling Bridge. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11799. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142411799

Zhang E, Wu Y, Guo S, Li P, Li H. Numerical Simulation Study of Rotating Structure for Large Tonnage Asymmetric T-Shaped Rigid Swiveling Bridge. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(24):11799. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142411799

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Enhui, Yuchen Wu, Sai Guo, Peng Li, and Hong Li. 2024. "Numerical Simulation Study of Rotating Structure for Large Tonnage Asymmetric T-Shaped Rigid Swiveling Bridge" Applied Sciences 14, no. 24: 11799. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142411799

APA StyleZhang, E., Wu, Y., Guo, S., Li, P., & Li, H. (2024). Numerical Simulation Study of Rotating Structure for Large Tonnage Asymmetric T-Shaped Rigid Swiveling Bridge. Applied Sciences, 14(24), 11799. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142411799