Evaluating Pipeline Inspection Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Detection in Mining Water Transport Systems

Abstract

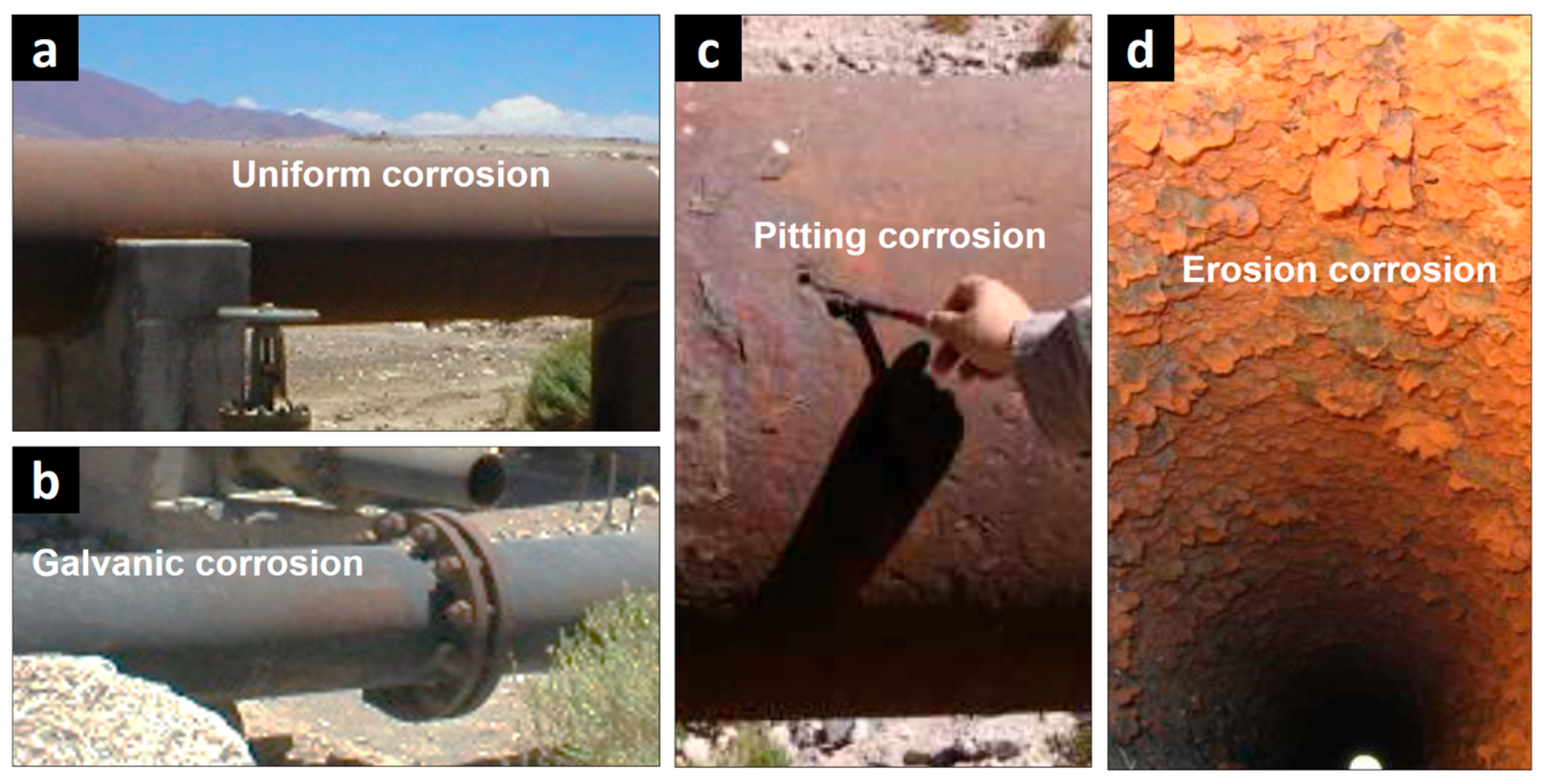

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Integrated Methodology for Pipeline Inspection Technology Selection and Evaluation

2.2. Operational Parameters for Each Inspection Technology

3. Water Transport Systems of Mining Industry: Evaluating Advanced Inspection Technologies

3.1. Characterizing Water Transport Systems

- Colaniqui Aqueduct: Transports 50 L/s over 104 km with an elevation drop of 1350 m from the high Andes to mining site. This system has been operational since 1978 with an initial diameter of 16 inches, reducing to 12.7 inches toward the final section. Thickness ranges from 6.35 mm to 4.78 mm.

- Inacatac Aqueduct: Primarily supplies drinking water to the mining plant, carrying 155 L/s over 114 km from an elevation of 4041 m. Operational since 1956, the pipeline begins with a 20-inch diameter, reducing to 12 inches with thicknesses ranging from 7.92 mm to 6.35 mm.

- Salamari Aqueduct: This 73 km long system transports 470 L/s to mining facilities and features reinforced sections. Pipeline diameters vary between 22.0 and 35.8 inches, with thicknesses between 6.35 and 7.94 mm, indicative of the high-pressure requirements along its route.

- Santaruna Aqueduct: With the largest flow rate, the Santaruna aqueduct carries 950 L/s over 64 km. It has diameters ranging from 30.0 to 50.8 inches and thicknesses between 8.89 and 11.11 mm, meeting the heavy-duty needs of mining operations.

- Tocontai Aqueduct: The oldest, operating since 1919, this aqueduct spans 91 km, transporting 50 L/s with diameters ranging from 10.0 to 14.0 inches and thicknesses between 4.78 and 6.35 mm.

3.2. Preliminary Selection of Potential Pipeline Inspection Technologies

3.3. Qualitative Evaluation of Inspection Techniques

4. Limitations and Recommendations

5. Concluding Remarks and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2024. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2024/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Neo, G.H.; Jha, S.K.; Acquah, N.K. Why Water Security is Our Most Urgent Challenge Today. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/10/why-water-security-is-our-most-urgent-challenge-today/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Ali, S.; Hawwa, M.A.; Baroudi, U. Effect of Leak Geometry on Water Characteristics Inside Pipes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Y.; Afrin, T.; Huang, Y.; Yodo, N. Sustainable Development for Oil and Gas Infrastructure from Risk, Reliability, and Resilience Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, L.N.; Huang, Y.; Yodo, N.; Liao, H. A Quantitative Approach of Measuring Sustainability Risk in Pipeline Infrastructure Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Jiang, B.; Ludwig, S.; Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Yan, F. Optimization for Pipeline Corrosion Sensor Placement in Oil-Water Two-Phase Flow Using CFD Simulations and Genetic Algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.; Mortula, M.M.; Yehia, S.; Ali, T.; Kaur, M. Evaluation of the Factors Impacting the Water Pipe Leak Detection Ability of GPR, Infrared Cameras, and Spectrometers under Controlled Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Tian, Z. A review on pipeline integrity management utilizing in-line inspection data. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 92, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishawy, H.A.; Gabbar, H.A. Review of pipeline integrity management practices. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2010, 87, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piratla, K.R.; Momeni, A. A Novel Water Pipeline Asset Management Scheme Using Hydraulic Monitoring Data. In Pipelines 2019; Proceedings, Nashville, TN, USA, 21–24 July 2019; Heidrick, J.W., Mihm, M.S., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, N.S.; Balmer, D. Risk Based Pipeline Integrity Management System—A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–10 November 2016; p. D031S081R004. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, R. From Water Management to Water Stewardship—A Policy Maker’s Opinion on the Progress of the Mining Sector. Water 2019, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A.J.; Bury, J.T. Institutional challenges for mining and sustainability in Peru. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17296–17301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Minero. La Industria Minera en 2022. Available online: https://consejominero.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Cifras-Actualizadas-de-la-Mineria-2023-Octubre.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Central Bank of Chile. The Chilean Economy at a Glance. Available online: https://www.bcentral.cl/documents/33528/42286/fundamentals_ing_mar_23.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Consejo Minero. Cifras Actualizadas de la Minería. Available online: https://consejominero.cl/mineria-en-chile/cifras-actualizadas-de-la-mineria/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Zhang, X.; Gao, L.; Barrett, D.; Chen, Y. Evaluating Water Management Practice for Sustainable Mining. Water 2014, 6, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, D.P.; Kirpalani, D.M. Process effluents and mine tailings: Sources, effects and management and role of nanotechnology. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, M. Recognition of Corrosion State of Water Pipe Inner Wall Based on SMA-SVM under RF Feature Selection. Coatings 2022, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Z.; Alam, M.K.; Nayan, N.A. Recent Advances in Nondestructive Method and Assessment of Corrosion Undercoating in Carbon–Steel Pipelines. Sensors 2022, 22, 6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, F.; Zhou, X.; Ding, Z.; Qiao, X.; Song, D. Application Research of Ultrasonic-Guided Wave Technology in Pipeline Corrosion Defect Detection: A Review. Coatings 2024, 14, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.; Tan, M.Y.; Forsyth, M. An overview of major methods for inspecting and monitoring external corrosion of on-shore transportation pipelines. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Cong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, F.; Gao, Y.; An, W.; Noureldin, A. A Comprehensive Review of Micro-Inertial Measurement Unit Based Intelligent PIG Multi-Sensor Fusion Technologies for Small-Diameter Pipeline Surveying. Micromachines 2020, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, Z. Deep Learning Empowered Structural Health Monitoring and Damage Diagnostics for Structures with Weldment via Decoding Ultrasonic Guided Wave. Sensors 2022, 22, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišutis, R.; Tumšys, O.; Žukauskas, E.; Samaitis, V.; Draudvilienė, L.; Jankauskas, A. An Inspection Technique for Steel Pipes Wall Condition Using Ultrasonic Guided Helical Waves and a Limited Number of Transducers. Materials 2023, 16, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, E.H.; Abdul Rahim, R.H. A review on ultrasonic guided wave technology. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 18, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavamian, A.; Mustapha, F.; Baharudin, B.T.H.T.; Yidris, N. Detection, localisation and assessment of defects in pipes using guided wave techniques: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Fu, M.; Hu, S.; Gu, Y.; Lou, H. A Review of the Metal Magnetic Memory Technique. In Volume 4: Materials Technology. Proceedings of the ASME 2016 35th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Busan, Republic of Korea, 19–24 June 2016; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morken Group. Inspección Remota MMM/LSM en un Oleoducto de 90 Kilómetros de Extensión. Available online: https://www.morkengroup.com/case_study/inspeccion-remota-mmm-lsm-en-un-oleoducto-de-90-kilometros-de-extension/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Shi, M.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhou, Z. Pipeline Damage Detection Based on Metal Magnetic Memory. IEEE Magn. Soc. 2021, 57, 6200615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaei, H.R.; Eslami, A.; Egbewande, A. A review on pipeline corrosion, in-line inspection (ILI), and corrosion growth rate models. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2017, 149, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascencio, F.; Velilla, L.M.; de Souza, R.D.; Silva, R.; Bernabé, T.; Assante, R.; Pacheco, J.M.; Cardacce, M.; Heredia, L.; Hurtado, J.F.; et al. Guía ARPEL de Gestión Del Proceso ILI en Ductos. Asociación De Empresas De Petróleo, Gas Y Energía Renovable De América Latina Y El Caribe. 2019. Available online: https://www.arpel.org/publicaciones/guia-de-gestion-del-proceso-ili-en-ductos (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Arboleda Henao, J.S. Inspección en Línea–ILI-en Ductos Desafiantes o no Marraneables. Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. Trabajo de título de especialista en gestión de la integridad y corrosión. Available online: https://repositorio.uptc.edu.co/items/b9852cc8-cce6-46df-8ac5-f6f2f04f6c15 (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Falque, R.; Vidal-Calleja, T.; Miro, J. Defect Detection and Segmentation Framework for Remote Field Eddy Current Sensor Data. Sensors 2017, 17, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Choi, D.; Yoo, D.G.; Kim, K.P. Development of the Methodology for Pipe Burst Detection in Multi-Regional Water Supply Networks Using Sensor Network Maps and Deep Neural Networks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusop, M.H.; Ghazali, M.F.; Yusof, M.F.M.; Remli, M.A.P. Pipeline condition assessment by instantaneous frequency response over hydroinformatics based technique—An experimental and field analysis. Fluids 2021, 6, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Fan, Z.; Hao, X.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J. Prediction Model of Corrosion Rate for Oil and Gas Pipelines Based on Knowledge Graph and Neural Network. Processes 2024, 12, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Azmi, P.A.; Yusoff, M.; Mohd Sallehud-din, M.T. A Review of Predictive Analytics Models in the Oil and Gas Industries. Sensors 2024, 24, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoody, J. Pipeline Issues Series: ILI Smart Pigs. Available online: https://liquidenergypipelines.org/page/resources (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Zhang, X.; Xie, X. Model for the Failure Prediction Mechanism of In-Service Pipelines Based on IoT Technology. Processes 2024, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonis, M. Corrosion Management of a Worldwide Existing Pipeline Network. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 1–4 November 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essang, N.P. Simulation and Modelling of Pipeline Corrosion and Integrity Management in Oil and Gas Industry. Rekha Patel 2019, 3, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukhin, V.; Andrianov, A.; Makisha, N. Pitting Corrosion of Steel Pipes in Water Supply Systems: An Influence of Shell-like Layer. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Deng, K. Effect of Chloride and Iodide on the Corrosion Behavior of 13Cr Stainless Steel. Metals 2022, 12, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesús Villegas-Saucillo, J.; Díaz-Carmona, J.J.; Cerón-álvarez, C.A.; Juárez-Aguirre, R.; Domínguez-Nicolás, S.M.; López-Huerta, F.; Herrera-May, A.L. Measurement system of metal magnetic memory method signals around rectangular defects of a ferromagnetic pipe. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, S.; Dackermann, U. A Systematic Review of Advanced Sensor Technologies for Non-Destructive Testing and Structural Health Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, M. Condition Assessment Technologies for Water Transmission and Distribution Systems; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dexon Technologies UT-CS Dexon Hawk In-line Inspection System for Crack Detection, Sizing and Metal Loss. Available online: https://www.dexon-technology.com/pipeline-services/intelligent-pigging/ultrasonic-crack-detection-and-sizing-inline-inspection-tool (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Williamson, T.D. In-Line Inspection. Available online: https://www.tdwilliamson.com/solutions/pipeline-integrity/in-line-inspection (accessed on 17 November 2024).

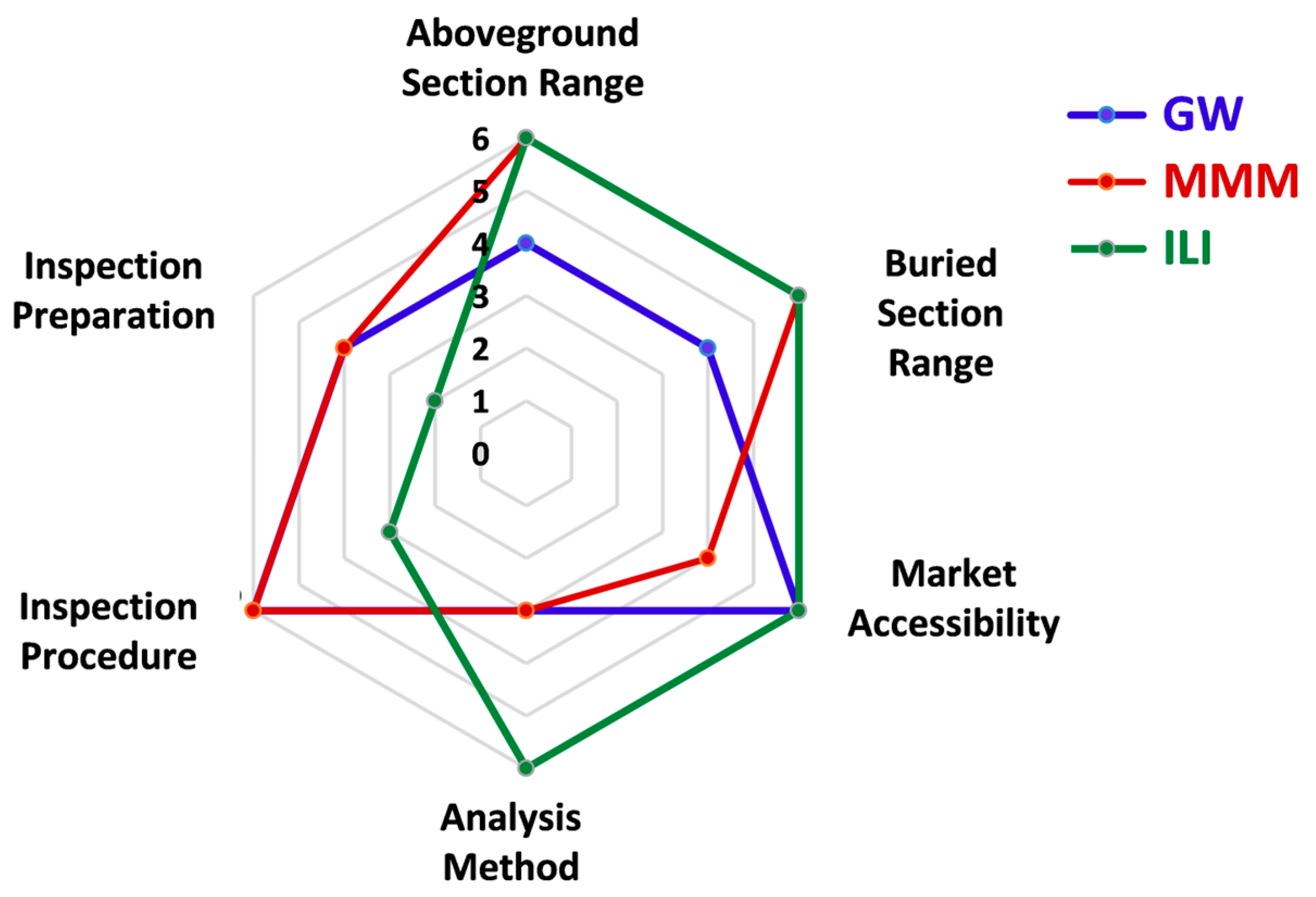

| Criterion | Level | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aboveground Section Range | Low | 2 | Covers small areas or discrete sections (<10 m). |

| Medium | 4 | Covers sections between 10 m and 1000 m. | |

| High | 6 | Covers extensive sections (>1000 m). | |

| Buried Section Range | Low | 2 | Covers small or discrete buried sections (<10 m). |

| Medium | 4 | Covers buried sections between 10 m and 1000 m. | |

| High | 6 | Covers buried sections extensively (>1000 m). | |

| Market Accessibility | Low | 2 | Very limited availability, with minimal global presence. |

| Medium | 4 | Moderately available, with limited competition. | |

| High | 6 | Widely available globally, with strong service support. | |

| Analysis Method | Qualitative | 3 | Provides location data but lacks precision in damage severity quantification. |

| Quantitative | 6 | Offers precise data, including severity assessment for informed decision-making. | |

| Inspection Procedure | Disruptive | 3 | Requires operational interruption or physical access adjustments. |

| Non-disruptive | 6 | Can be performed without disrupting pipeline operations. | |

| Inspection Preparation | Minimal | 2 | Basic preparation such as calibration, with no additional steps. |

| Moderate | 4 | Includes preparatory activities like cleaning or partial site modification. | |

| Extensive | 6 | Requires significant preparatory actions, including infrastructure adjustments or site changes. |

| Aspect | GWUT | MMM | ILI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aboveground Section Range | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Buried Section Range | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Market Accessibility | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Analysis Method | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Inspection Procedure | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| Inspection Preparation | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Total Score | 27 | 29 | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tuninetti, V.; Huentemilla, M.; Gómez, Á.; Oñate, A.; Menacer, B.; Narayan, S.; Montalba, C. Evaluating Pipeline Inspection Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Detection in Mining Water Transport Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031316

Tuninetti V, Huentemilla M, Gómez Á, Oñate A, Menacer B, Narayan S, Montalba C. Evaluating Pipeline Inspection Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Detection in Mining Water Transport Systems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(3):1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031316

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuninetti, Víctor, Matías Huentemilla, Álvaro Gómez, Angelo Oñate, Brahim Menacer, Sunny Narayan, and Cristóbal Montalba. 2025. "Evaluating Pipeline Inspection Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Detection in Mining Water Transport Systems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 3: 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031316

APA StyleTuninetti, V., Huentemilla, M., Gómez, Á., Oñate, A., Menacer, B., Narayan, S., & Montalba, C. (2025). Evaluating Pipeline Inspection Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Detection in Mining Water Transport Systems. Applied Sciences, 15(3), 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031316